1. Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a globally prevalent virus that remains latent after primary infection, which can be reactivated when immunocompromised, leading to end-organ disease. Despite prophylactic and preemptive therapy, CMV reactivation remains one of the most common and fatal complications of transplantation. Ganciclovir, valganciclovir, and foscarnet are used to treat CMV infection, but their side effects, such as myelosuppression, pose challenges in the context of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) [

1,

2]. Currently, prophylaxis is an important strategy for preventing CMV infection in transplant recipients [

3]. Letermovir, a recently introduced antiviral agent that targets the CMV terminase complex, is reportedly effective in preventing CMV reactivation in seropositive allogeneic HCT (allo-HCT) recipients [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of letermovir prophylaxis in preventing CMV reactivation in allo-HCT recipients. Vyas et al. reported a systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world studies of letermovir [

8], however great part of those studies were conducted in US or Europe, data from the Asia-Pacific region were scarce. The majority of the East-Asian population is infected with CMV at a young age; 94% of Korean adults are reportedly CMV seropositive, which contrasts with the results of the clinical trial conducted by Marty et al., where 60.8% of hematopoietic stem cell donors of the study population were CMV seropositive [

7,

9,

10]. Differences in CMV risk factors, such as type of transplantation, conditioning intensity, CMV serostatus, might cause differences in efficacy of letermovir prophylaxis. Additionally, follow-up observation until 1-year after transplantation showed novel facet of CMV reactivation, such as breakthrough CMV reactivation during letermovir prophylaxis, CMV blips in the post-engraftment period, and late reactivation after discontinuation of letermovir which remain unexplored in real clinical field [

11,

12,

13].

The aim of this study was to analyze real-world data for incidence and characteristics of CMV infections until 1 year after allo-HCT under 100-day letermovir prophylaxis. We evaluated the proportion of patients with clinically significant CMV infection (CS-CMVi) and mortality at 14 weeks, 24 weeks, and 1 year after transplantation. We also analyzed risk factors for CS-CMVi along with examining letermovir breakthrough CMV DNAemia, and occurrence of CMV blips and refractory or resistance CMV infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and study design

This retrospective single-institution cohort study was conducted at Catholic Hematology Hospital, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital. We reviewed the electronic medical records of patients over 18 years of age who underwent allo-HCT between November 1, 2020 and October 31, 2021. According to the approved indication, patients received letermovir prophylaxis if they were CMV seropositive and had undetectable plasma levels of CMV DNA within 5 days before letermovir initiation. Patients on dialysis with creatinine clearance < 10 mL/min and liver impairment equivalent to Child-Pugh class C were excluded from letermovir prophylaxis. Patients using rifampicin, rifabutin, nafcillin, and anticonvulsants, and patients prescribed statins and cyclosporine simultaneously were excluded because of risk of drug interactions with letermovir, according to data from previous clinical trials [

4,

7].

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (No. KC20MODP0823). Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective design of our study.

2.2. Institutional protocol

Letermovir prophylaxis was initiated between day 0 and 28 after allo-HCT. Blood CMV DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed biweekly during hospitalization and at every visit after discharge. Letermovir prophylaxis was continued until day 100 after allo-HCT unless the patient showed CS-CMVi, such as CMV DNAemia requiring preemptive therapy or CMV end-organ disease. Letermovir prophylaxis was discontinued if underlying hematological disease relapsed. We categorized the patients according to their risk of CMV reactivation. The high-risk group included patients with related donors with at least one mismatch at one of the three HLA gene loci (HLA-A, B, or HLA-DR); those with unrelated donors with at least one mismatch at one of the four HLA loci (HLA-A, B, C, or DRB1); patients with haploidentical transplants; cord blood transplants; and presence of clinically significant graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) over grade 2 that led to the use of steroids with a dose equivalent to at least 20 mg of prednisolone per day for more than 2 weeks at the time of letermovir initiation. Patients who did not meet the above criteria were classified as low-risk. Patients received 480 mg of letermovir daily, but those prescribed cyclosporine received 240 mg of concomitant letermovir owing to drug interactions. 7 CS-CMVi was defined as serum CMV DNA level > 500 IU/mL in high-risk patients and > 1000 IU/mL in low-risk patients until day 100 after transplantation. In these cases, letermovir prophylaxis was stopped and preemptive therapy started. After day 100, preemptive treatment was initiated if the serum CMV DNA level was > 1000 IU/mL, regardless of the risk group.

2.3. Definitions

CMV viral load was measured by real-time quantitative PCR test using artus CMV QS-RGQ MDx Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and Rotor-Gene Q (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The lower limit of quantification of the assay was 69.7 IU/mL. PCR results were classified into three categories: ‘Not detected,’ when no plasma CMV DNA was detected; ‘result under 69.7 IU/mL’, when the level of CMV DNA was lower than the limit of quantification; and CMV DNA titer reported as the measured value in IU/mL, when it was quantifiable. In the present study, the quantifiable value of CMV DNA was defined as the level of CMV reactivation. The definition of CMV end-organ disease was adopted from a previous description of Ljungman et al. [

14]. An increasing or persistent CMV load after at least 2 weeks of appropriate treatment was defined as refractory or probable refractory CMV infection, respectively [

15]. CMV blip was interpreted as the presence of CMV DNAemia at any level in a single plasma specimen preceded and succeeded by an undetectable PCR specimen drawn 7 days apart [

11,

12].

2.4. Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics software, version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, and a Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables. The time to CS-CMVi between the groups was compared using the Kaplan-Meier curve and Log-rank test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was also performed. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study population and baseline characteristics

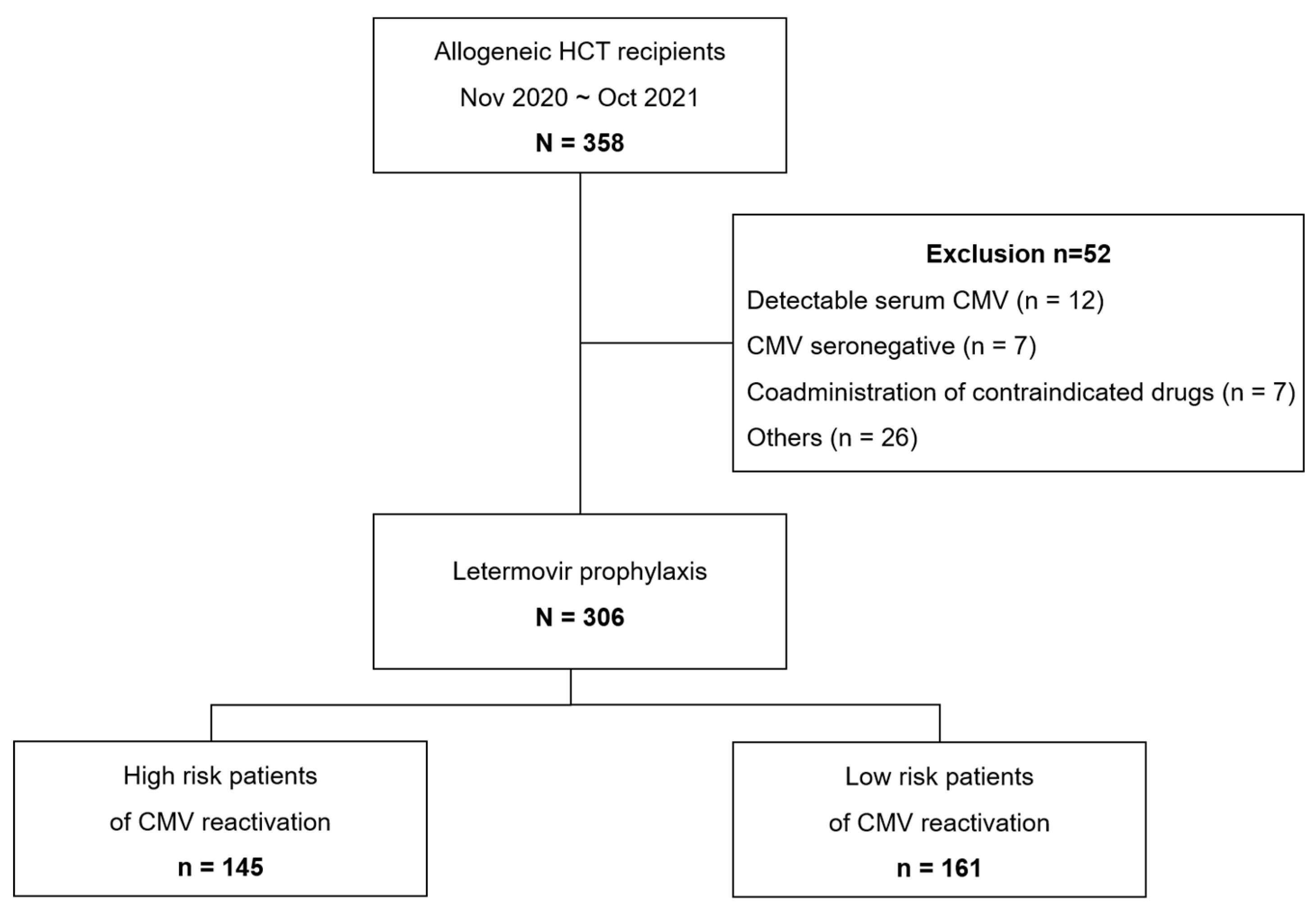

During the study period, 358 patients underwent allo-HCT, 306 of whom received letermovir prophylaxis (

Figure 1). Fifty-two patients were excluded from analysis, mainly due to the detection of serum CMV DNA (n = 12), CMV seronegativity (n = 7), use of contraindicated drugs (n = 7), and other situations where letermovir was not prescribed to the patients (i.e., physician preference, n = 26). Less than 2% of allo-HCT recipients (n = 7) were CMV seronegative at the time of transplantation. Two patients underwent transplantation twice during this period, and were counted for each episode. Of the 306 patients who received letermovir prophylaxis, 47.4% were defined as high risk, while 52.6% were at low risk for CMV reactivation (

Figure 1).

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of patients. The median age of the patients was 50 years (range, 18–73), and 51.0% were men. Acute myeloid leukemia was the most common underlying disease, followed by acute lymphocytic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative neoplasms, and multiple myeloma. Other diseases included lymphoma (n = 8), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (n = 4), and mixed phenotype acute leukemia (n = 2). A total of 165 patients underwent myeloablative conditioning. Patients with matched sibling donors and matched unrelated donors accounted for 27.5% and 38.2%, respectively. Family mismatched transplantation was performed in 26.1%, while double cord transplantation was performed in 8.2% of patients. The majority of the donors were CMV seropositive (79.1%) (

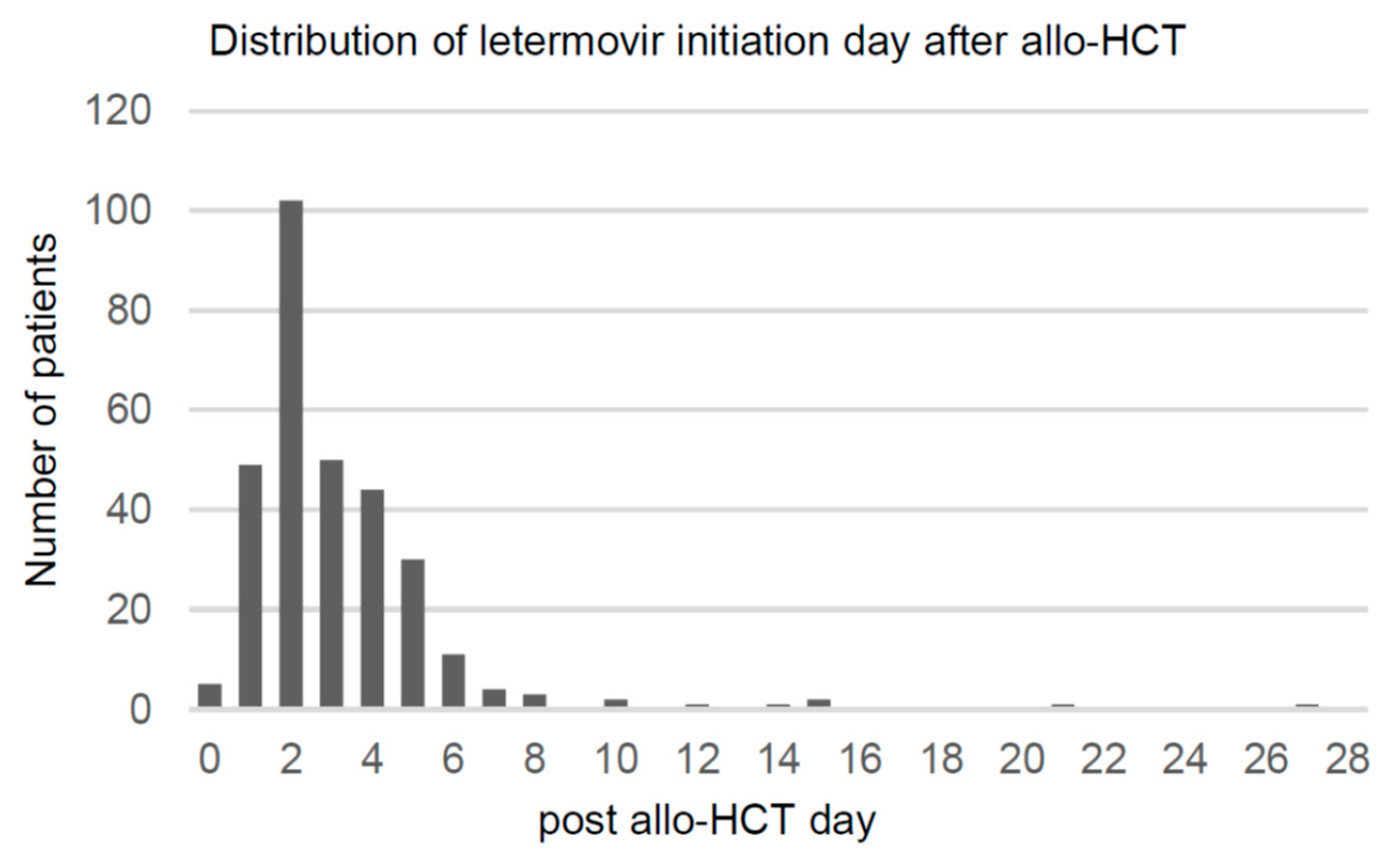

Table 1). Distribution of the day of letermovir initiation after transplantation is shown in

Figure 2. Patients began letermovir prophylaxis at a median of day 2 (range, day 0–27) after transplantation.

3.2. Discontinuation of letermovir

Seventy-four patients (24.2%) discontinued letermovir before day 100 after transplantation, mainly because of early CMV reactivation (n = 35, 11.4%), relapse of underlying hematologic disease (n = 19, 6.2%), death (n = 9, 2.9%), loss to follow up (n = 3, 1.0%), initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy (n = 1, 0.3%), adverse effects of letermovir, such as nausea vomiting (n = 1, 0.3%), and poor physical condition that is incapable of oral intake (n = 6, 2.0%). Intravenous letermovir has been administered since March 2021, allowing a larger number of patients to continue prophylaxis during the study period.

3.3. CMV reactivation and mortality

Clinically significant CMV infection was observed in 11.4% (n = 35) at 14 weeks, 31.7% (n = 97) at 24 weeks, and 36.9% (n = 113) of patients at 1 year after allo-HCT. Any level of CMV reactivation, which included both CS-CMVi and CMV DNAemia not requiring preemptive therapy, occurred in 26.5% (n = 81), 64.1% (n = 196), and 73.9% (n = 226) of patients at 14 weeks, 24 weeks, and 1 year after transplantation, respectively. All-cause mortality was 7.2% (n = 22), 10.5% (n = 35), and 21.6% (n = 66) at 14 weeks, 24 weeks, and 1 year, respectively (

Table 2).

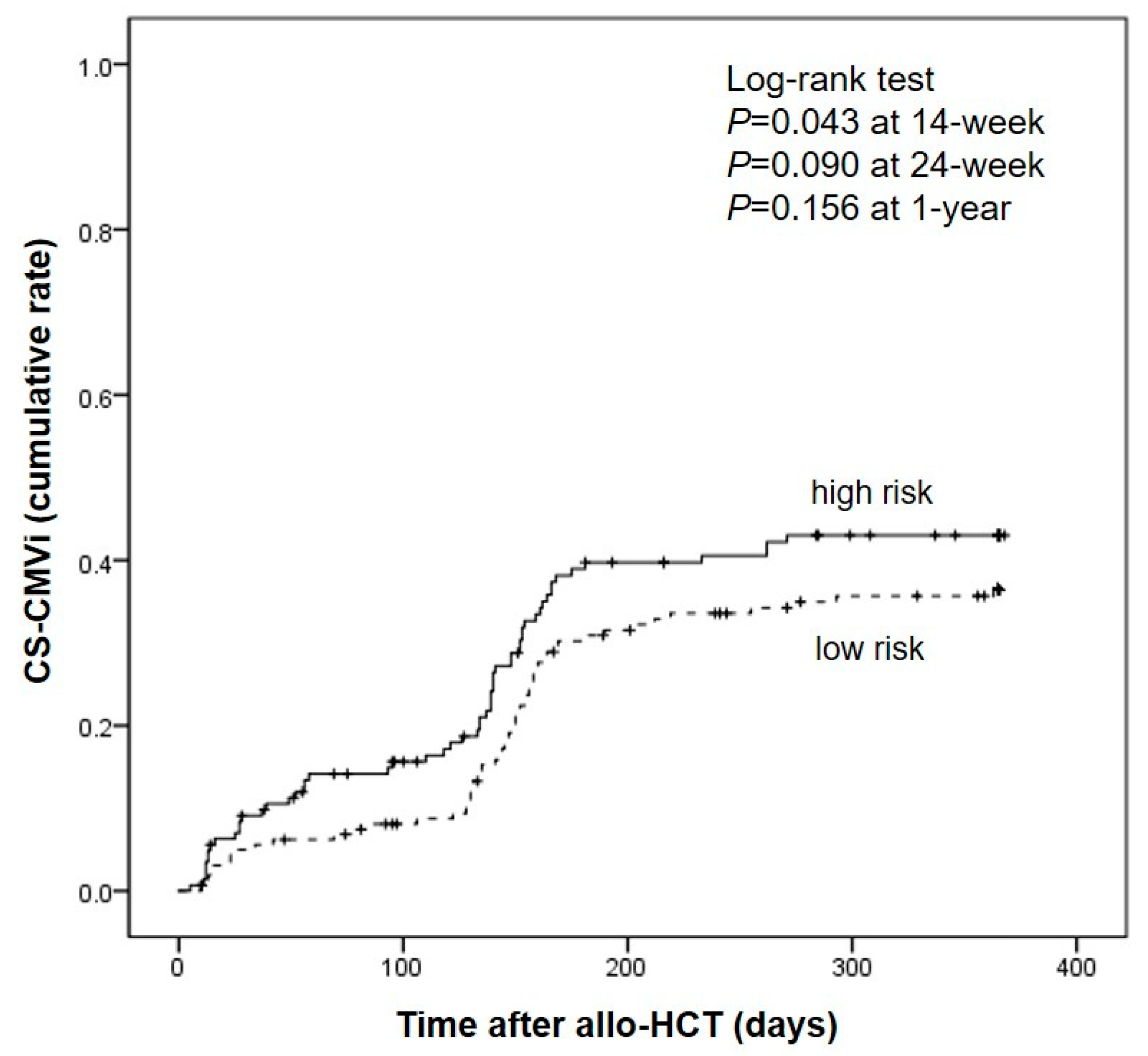

We compared incidence of CS-CMVi in high- and low-risk groups one year post-transplantation. CS-CMVi occurred 15.2% (n = 22/145) and 8.1% (n = 13/161) at 14-week, 35.2% (n = 51/145) and 28.6% (n = 46/161) at 24-week, 39.3% (n = 57/145) and 34.9% (n = 56/161) at 1-year after transplantation in high- and low-risk group respectively. The cumulative incidence of CS-CMVi was significantly higher in the high-risk group than that in low-risk group at 14 weeks (P = 0.043). Compared to low-risk group, high-risk group showed a consistently higher incidence of CS-CMVi at 24 weeks and 1 year after transplantation; however, the cumulative incidence rate was not statistically significant (P = 0.090 at 24 weeks, P = 0.156) at 1 year. Notably, a sharp increase in CS-CMVi was observed from day 130 to 180 after transplantation (

Figure 3).

We investigated the incidence of CS-CMVi according to the time of initiation of letermovir prophylaxis. The early initiation group included patients who began letermovir on day 0–2 after allo-HCT (n = 156), whereas the late initiation group included patients who began letermovir on day 3–28 after transplantation (n = 150). The cumulative incidence of CS-CMVi between the early and late letermovir initiation groups was not significantly different through 1 year after transplantation (P = 0.746 at 14 weeks, P = 0.641 at 24 weeks, P = 0.925 at 1 year after transplantation).

3.4. Risk factors for clinically significant CMV infection

We analyzed factors affecting CMV reactivation, such as the type of conditioning, underlying malignancies, type of transplantation, CMV serostatus of the donor, and presence of GVHD before CS-CMVi. On multivariate analysis, only GVHD ≥ grade 2 was a significant risk factor of CMV reactivation at 1 year after transplantation (adjusted OR 3.64, 95% CI [2.036–6.510]; P < 0.001). Myeloablative conditioning; lymphoid lineage malignancies such as acute lymphocytic leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma; matched sibling donor transplantation; and CMV seronegative donors did not significantly influence the risk of CMV reactivation (

Table 3).

3.5. Letermovir breakthrough CMV reactivation

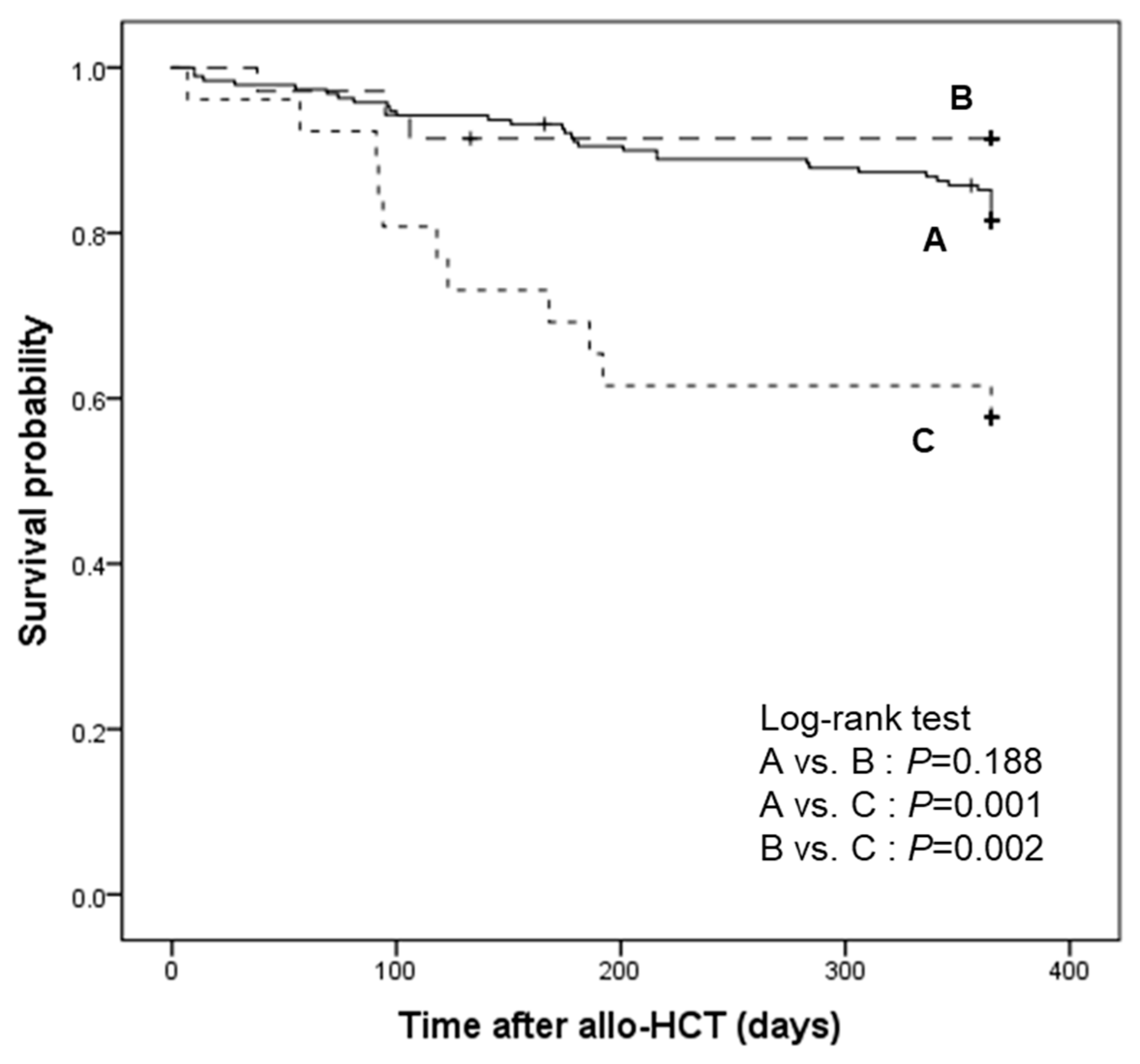

We compared the 1-year relapse-free survival of patients based on their CMV reactivation status at 14 weeks after transplantation (

Figure 4). After excluding 55 relapsed patients, 190 patients did not show any level of CMV reactivation (group A) but letermovir breakthrough CMV reactivation occurred in 61 patients. Among them, 35 patients had CMV DNAemia not requiring preemptive therapy and completed letermovir prophylaxis (group B), whereas 26 patients had CS-CMVi and stopped letermovir for the initiation of preemptive therapy (group C). The 1-year relapse-free survival was significantly higher in groups A and B, which continued letermovir, than in group C, which discontinued letermovir for preemptive therapy (group A vs. C,

P = 0.001; group B vs. C,

P = 0.002) (

Figure 4).

3.6. Refractory/probable refractory CMV infection

Among patients who developed CS-CMVi, we identified 15.9% (n = 18) of refractory/probable refractory CMV infections. Among them, 7 cases occurred during letermovir prophylaxis, at a median of day 16 post-HCT. We performed DNA sequencing of 14 patients with refractory/probable refractory CMV infection, and seven patients appeared to have mutations in UL54 and UL97. Among these seven patients with mutations, five had variants of unknown significance, one had a known drug resistance mutation of UL97, and the last one had a deletion of the UL97 gene. All these refractory/probable refractory cases experienced significant GVHD that happened at median of day 29 post-HCT, GVHD occurred before CMV infection in 13 cases, whereas it happened after CMV infection in 5 cases.

4. Discussion

In this study, we observed that letermovir prophylaxis was effective in reducing CS-CMVi until day 100, but incidence of CS-CMVi sharply increased from day 130 to 180 after transplantation. Moreover, mortality was significantly higher in case of CS-CMVi, unlike subclinical CMV reactivation. Cumulative incidence of CS-CMVi was 11.4%, 31.7%, and 36.9% at 14 weeks, 24 weeks, and 1 year after transplantation, respectively. Incidence of CMV reactivation and CMV diseases declined compared to previous studies conducted at our institution. For instance, before introduction of letermovir, 56.1% of allo-HCT patient developed any level of CMV reactivation between engraftment and day 100 after transplantation, compared to 26.5% with letermovir prophylaxis [

16,

17]. Our incidence of CS-CMVi is higher than the results of Marty et al., who reported CS-CMVi incidence rates of 7.7% and 17.5% at 14 weeks and 24 weeks after transplantation, respectively. This difference could be explained by higher proportion of CMV seropositive donor (79.1% vs. 61.7%), use of antithymocyte globulin (79.4% vs. 37.5%), and high risk patients (47.4% vs. 32.4%) in our institution [

7].

There is no controversy regarding the effectiveness of letermovir prophylaxis until day 100 after allo-HCT; however, it has been observed to increase in the incidence of CS-CMVi especially between 4-6 months after transplantation. In our study, we examined whether traditional risk factors for CMV have been changed under letermovir prophylaxis [

18]. In contrast to other risk factors that did not demonstrate statistical significance, GVHD emerged as the sole risk factor increasing the risk of CS-CMVi by 3.6-fold. In such cases, prolonged letermovir prophylaxis may help in delaying CMV reactivation until the restoration of cellular immunity. Studies on extended letermovir prophylaxis are in progress, and its effect on the prevention of CMV infections in specific risk group needs further investigation [

19].

Data on CMV resistance is important but still lacking. Our institution performs resistance test targeting

UL54 and

UL97 genes [

20,

21]. Cases of refractory/probable refractory CMV infection were 15.9% in this study, and 1.8% (n = 2) had known CMV resistance mutations. Variants of unknown significance in

UL54 or

UL97 mutation were 4.4% (n = 5). Although we did not perform sequencing for the

UL51,

UL56, or

UL89 genes as a routine process during the study period, which are associated with letermovir drug resistance [

22,

23], sequencing of these genes are also needed to identify CMV drug resistance in this letermovir prophylaxis era.

A previous study reported a significant difference in CMV DNAemia between the early (day 0–1) and late (day 2–27) prophylactic groups [

24]. Compared to other studies, letermovir prophylaxis was started relatively earlier in our institution, with a positively-skewed distribution with a median of day 2 (interquartile range: day 2–4) over a period of 28 days [

8]. The cumulative incidence of CS-CMVi between the early and late letermovir initiation groups of our institution was not significantly different through 1 year after transplantation. A possible explanation may be the tendency for early commencement of prophylaxis. Whether the early initiation of letermovir prophylaxis influences the incidence of CS-CMVi should be checked using data with an even distribution of initiation days.

We closely examined the first 14 weeks after transplantation, which was the period of letermovir prophylaxis. Mortality was significantly higher in patients with letermovir breakthrough CS-CMVi. This result could be explained by the severity of those patients. Among the 26 patients with letermovir breakthrough CS-CMVi, 10 died in the first year after transplantation due to septic shock, fungal infection, GVHD, and engraftment failure. Moreover, seven patients were identified as having refractory/probable refractory CS-CMVi. However, not all cases of letermovir breakthrough CMV reactivation had a poor prognosis. In subjects with letermovir breakthrough CMV reactivation not requiring preemptive therapy, relapse-free survival 1 year after transplantation was not different from patients with no CMV reactivation. In this patient group, we observed persistent but self-recovering low-titer CMV reactivation, or a single episode of CMV reactivation disappeared at the next examination without any intervention. This low-titer CMV reactivation was under the defined cut off value for preemptive therapy, that is 500 or 1000 IU/mL for high and low risk group respectively. Regardless of the interval between specimens or the peak viral load under the cut off value, single episodes of CMV reactivation were frequently observed and did not appear to be related to the non-relapse mortality. Such episodes of CMV reactivation can also be explained by the mechanism of action of letermovir. Letermovir inhibits the CMV DNA terminase complex, which cuts viral DNA into viral genomes for packaging into mature viral particles [

5,

6]. Cassaniti et al. detected the accumulation of non-replicative CMV DNA called ‘abortive CMV DNA’, which may mimic CMV reactivation [

24]. Laboratory techniques could help to distinguish between real CMV reactivation leading to CS-CMVi and abortive subclinical CMV DNA particles; however, it is difficult to differentiate in real-world clinical practice. We used a cut-off value of serum CMV titer for CS-CMVi and started preemptive therapy; adjustment of this cut-off value to reduce the detection of subclinical CMV infection and select CS-CMVi requires further research.

The strength of our study is that we provided real-world data of letermovir prophylaxis in population with high CMV seroprevalence. We categorized letermovir breakthrough CMV reactivation and compared mortality. We noted not all CMV reactivation had poor prognosis, and some reactivation could be observed without stopping letermovir.

In summary, letermovir prophylaxis led to a lower incidence of CS-CMVi than that reported previously. However, we found CS-CMVi increased in patients with GVHD and during the period between 4–6 months after transplantation. During letermovir prophylaxis, not all patients with letermovir breakthrough CMV reactivation had a poor prognosis. Further study is needed to find more effective management strategies in preventing CMV infection, such as prophylaxis in especially high risk patients.

Author Contributions

DN and SYC analyzed data and drafted the paper. SYC and DGL designed the study and interpreted data. RL revised the manuscript. SP, SEL, BSC, YJK, SL and HJK contributed to data interpretation and manuscript revision. EJK participated in data collection and study logistics. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) and funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (no. HI21C0595).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (No. KC20MODP0823). Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective design of our study.

Data Availability Statement

Original data are available upon requests to the corresponding author via email.

Conflicts of Interest

SYC has served as a consultant for Takeda; and has received research support and payment for lectures from MSD and Pfizer. DGL has served as a consultant for MSD and Pfizer, he has also served as a board member for MSD, Pfizer, and Yuhan, and has received research support, and payment for lectures including service on speaker’s bureaus from MSD, Pfizer, Yuhan, and Eubiologics.

References

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, D.G.; Kim, H.J. Cytomegalovirus Infections after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Current Status and Future Immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanan, P.; Razonable, R.R. Cytomegalovirus Infections in Solid Organ Transplantation: A Review. Infect Chemother 2013, 45, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungman, P.; de la Camara, R.; Robin, C.; Crocchiolo, R.; Einsele, H.; Hill, J.A.; Hubacek, P.; Navarro, D.; Cordonnier, C.; Ward, K.N. Guidelines for the management of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with haematological malignancies and after stem cell transplantation from the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect Dis 2019, 19, e260–e272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemaly, R.F.; Ullmann, A.J.; Stoelben, S.; Richard, M.P.; Bornhauser, M.; Groth, C.; Einsele, H.; Silverman, M.; Mullane, K.M.; Brown, J.; Nowak, H.; Kolling, K.; Stobernack, H.P.; Lischka, P.; Zimmermann, H.; Rubsamen-Schaeff, H.; Champlin, R.E.; Ehninger, G.; Team, A.I.C.S. Letermovir for cytomegalovirus prophylaxis in hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldner, T.; Hewlett, G.; Ettischer, N.; Ruebsamen-Schaeff, H.; Zimmermann, H.; Lischka, P. The novel anticytomegalovirus compound AIC246 (Letermovir) inhibits human cytomegalovirus replication through a specific antiviral mechanism that involves the viral terminase. J Virol 2011, 85, 10884–10893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lischka, P.; Hewlett, G.; Wunberg, T.; Baumeister, J.; Paulsen, D.; Goldner, T.; Ruebsamen-Schaeff, H.; Zimmermann, H. In vitro and in vivo activities of the novel anticytomegalovirus compound AIC246. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, F.M.; Ljungman, P.; Chemaly, R.F.; Maertens, J.; Dadwal, S.S.; Duarte, R.F.; Haider, S.; Ullmann, A.J.; Katayama, Y.; Brown, J.; Mullane, K.M.; Boeckh, M.; Blumberg, E.A.; Einsele, H.; Snydman, D.R.; Kanda, Y.; DiNubile, M.J.; Teal, V.L.; Wan, H.; Murata, Y.; Kartsonis, N.A.; Leavitt, R.Y.; Badshah, C. Letermovir Prophylaxis for Cytomegalovirus in Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, A.; Raval, A.D.; Kamat, S.; LaPlante, K.; Tang, Y.; Chemaly, R.F. Real-World Outcomes Associated With Letermovir Use for Cytomegalovirus Primary Prophylaxis in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10, ofac687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.R.; Kim, K.R.; Kim, D.S.; Kang, J.M.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, J.M.; Oh, S.Y.; Kang, C.I.; Chung, D.R.; Peck, K.R.; et al. Changes in Cytomegalovirus Seroprevalence in Korea for 21 Years: A Single Center Study. Pediatric Infection & Vaccine 2018, 25, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zuhair, M.; Smit, G.S.A.; Wallis, G.; Jabbar, F.; Smith, C.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Griffiths, P. Estimation of the worldwide seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol 2019, 29, e2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, D.; Talaya, A.; Giménez, E.; Martínez, A.; Hernández-Boluda, J.C.; Hernani, R.; Torres, I.; Alberola, J.; Albert, E.; Piñana, J.L.; Solano, C.; Navarro, D. Features of Cytomegalovirus DNAemia Blips in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: Implications for Optimization of Preemptive Antiviral Therapy Strategies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020, 26, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodding, I.P.; Mocroft, A.; da Cunha Bang, C.; Gustafsson, F.; Iversen, M.; Kirkby, N.; Perch, M.; Rasmussen, A.; Sengeløv, H.; Sørensen, S.S.; Lundgren, J.D. Impact of CMV PCR Blips in Recipients of Solid Organ and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transplant Direct 2018, 4, e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royston, L.; Royston, E.; Masouridi-Levrat, S.; Chalandon, Y.; Van Delden, C.; Neofytos, D. Predictors of breakthrough clinically significant cytomegalovirus infection during letermovir prophylaxis in high-risk hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Immun Inflamm Dis 2021, 9, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungman, P.; Boeckh, M.; Hirsch, H.H.; Josephson, F.; Lundgren, J.; Nichols, G.; Pikis, A.; Razonable, R.R.; Miller, V.; Griffiths, P.D. Definitions of Cytomegalovirus Infection and Disease in Transplant Patients for Use in Clinical Trials. Clin Infect Dis 2017, 64, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chemaly, R.F.; Chou, S.; Einsele, H.; Griffiths, P.; Avery, R.; Razonable, R.R.; Mullane, K.M.; Kotton, C.; Lundgren, J.; Komatsu, T.E.; Lischka, P.; Josephson, F.; Douglas, C.M.; Umeh, O.; Miller, V.; Ljungman, P.; Resistant Definitions Working Group of the Cytomegalovirus Drug Development, F. Definitions of Resistant and Refractory Cytomegalovirus Infection and Disease in Transplant Recipients for Use in Clinical Trials. Clin Infect Dis 2019, 68, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-M.; Lee, D.-G.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Min, C.-K.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, S.; Choi, J.-H.; Yoo, J.-H.; Kim, D.-W.; Lee, J.-W.; Min, W.-S.; Shin, W.-S.; Kim, C.-C. Characteristics of Cytomegalovirus Diseases among Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients : A 10-year Experience at an University Hospital in Korea. Infect Chemother 2009, 41, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kee, S.Y.; Lee, D.G.; Choi, S.M.; Park, S.H.; Kwon, J.C.; Eom, K.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.; Min, C.K.; Kim, D.W.; Choi, J.H.; Yoo, J.H.; Lee, J.W.; Min, W.S. Infectious complications following allogeneic stem cell transplantation: Reduced-intensity vs. myeloablative conditioning regimens. Transpl Infect Dis 2013, 15, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.K.; Cho, S.Y.; Yoon, S.S.; Moon, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Cheong, J.W.; Jang, J.H.; Seo, B.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, D.G. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Invasive Fungal Diseases among Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients in Korea: Results of "RISK" Study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017, 23, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extension of Letermovir (LET) From Day 100 to Day 200 Post-transplant for the Prevention of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT) Participants (MK-8228-040). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03930615.

- Allice, T.; Busca, A.; Locatelli, F.; Falda, M.; Pittaluga, F.; Ghisetti, V. Valganciclovir as pre-emptive therapy for cytomegalovirus infection post-allogenic stem cell transplantation: Implications for the emergence of drug-resistant cytomegalovirus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009, 63, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurain, N.S.; Chou, S. Antiviral drug resistance of human cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010, 23, 689–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, E.M.; Kleine-Albers, J.; Gabaev, I.; Babic, M.; Wagner, K.; Binz, A.; Degenhardt, I.; Kalesse, M.; Jonjic, S.; Bauerfeind, R.; Messerle, M. The human cytomegalovirus UL51 protein is essential for viral genome cleavage-packaging and interacts with the terminase subunits pUL56 and pUL89. J Virol 2013, 87, 1720–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, C.; Tilloy, V.; Frobert, E.; Feghoul, L.; Garrigue, I.; Lepiller, Q.; Mirand, A.; Sidorov, E.; Hantz, S.; Alain, S. First clinical description of letermovir resistance mutation in cytomegalovirus UL51 gene and potential impact on the terminase complex structure. Antiviral Res 2022, 204, 105361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassaniti, I.; Colombo, A.A.; Bernasconi, P.; Malagola, M.; Russo, D.; Iori, A.P.; Girmenia, C.; Greco, R.; Peccatori, J.; Ciceri, F.; Bonifazi, F.; Percivalle, E.; Campanini, G.; Piccirilli, G.; Lazzarotto, T.; Baldanti, F. Positive HCMV DNAemia in stem cell recipients undergoing letermovir prophylaxis is expression of abortive infection. Am J Transplant 2021, 21, 1622–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).