Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

15 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Program

2.2. Materials

- Reducing slag: This was produced in a local electric arc furnace steelmaking plant, and its appearance is shown in Figure 1. Among them, the reducing slag coarse aggregate had a water absorption rate of 10.7%, a specific gravity of 2.70, and the fineness modulus was 5.87. The reducing slag fine-grain material had a water absorption rate of 5.29%, a specific gravity of 2.44, and a fineness modulus of 2.97;

- Bacterial solution: This contained Bacillus pasteurii, and its optical density (OD600) value was 1.0, as shown in Figure 2 (provided by Moji Technology Co., Ltd.);

- Cement: This was a locally produced Type I Portland cement, with a specific gravity of 3.15;

- Superplasticizer: A R-550 produced by Taiwan Sika Company was used.

2.3. Mix Proportions of the Concrete and Casting of Specimens

2.4. Test Methods

3. Results and Discussion

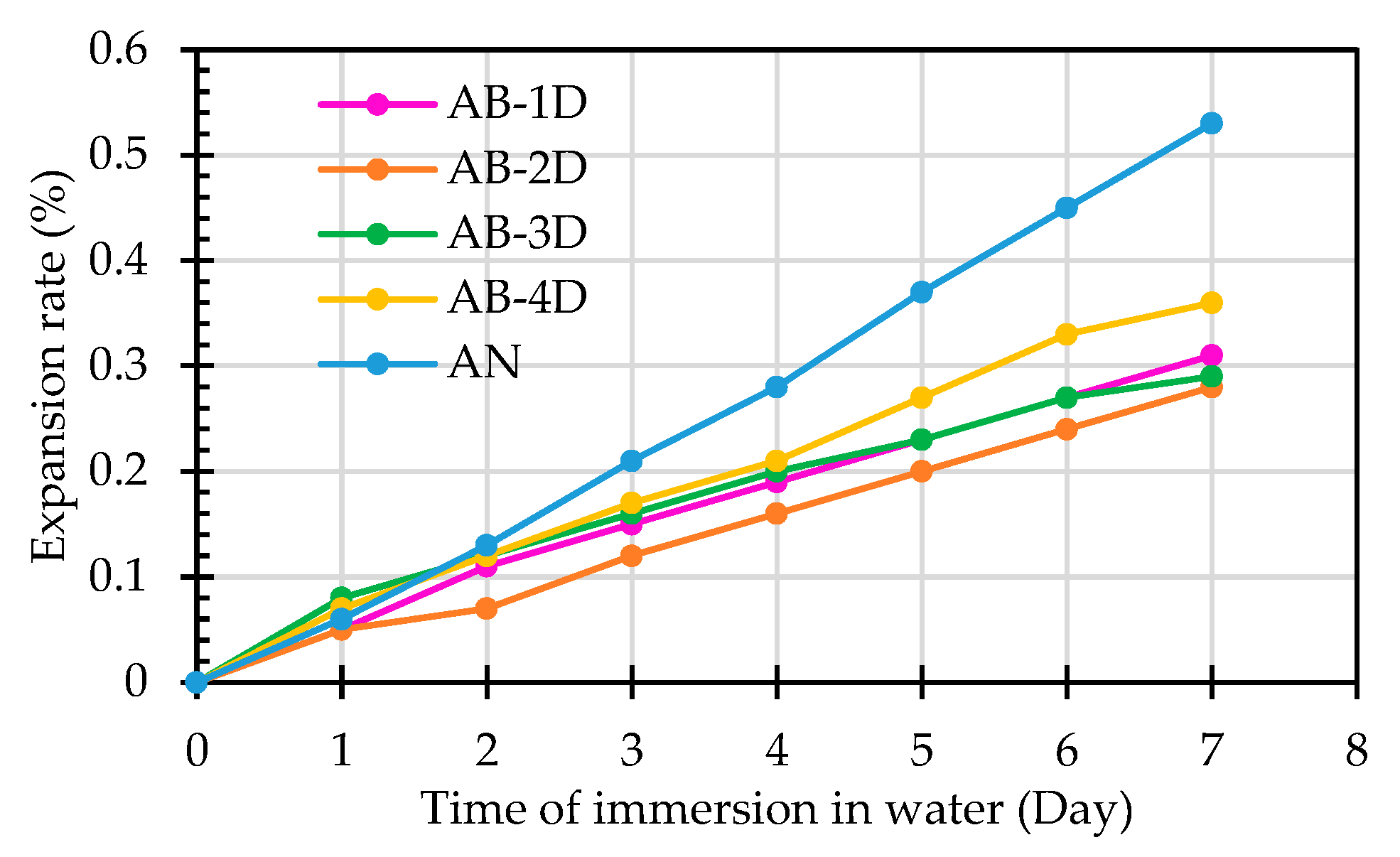

3.1. Results of the Potential Expansion Test of ERSAs from Hydration Reactions

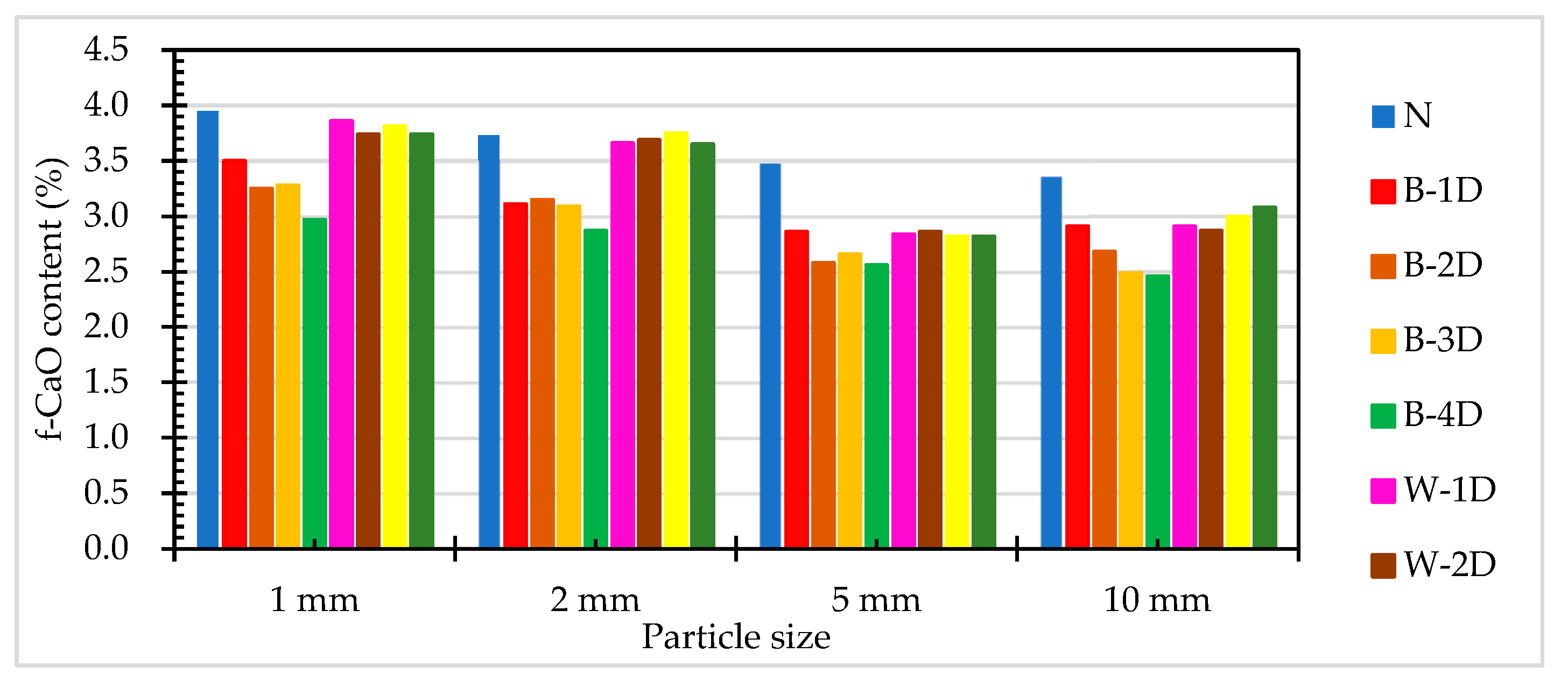

3.2. Results of the Free Calcium Oxide Titration Test of ERSAs

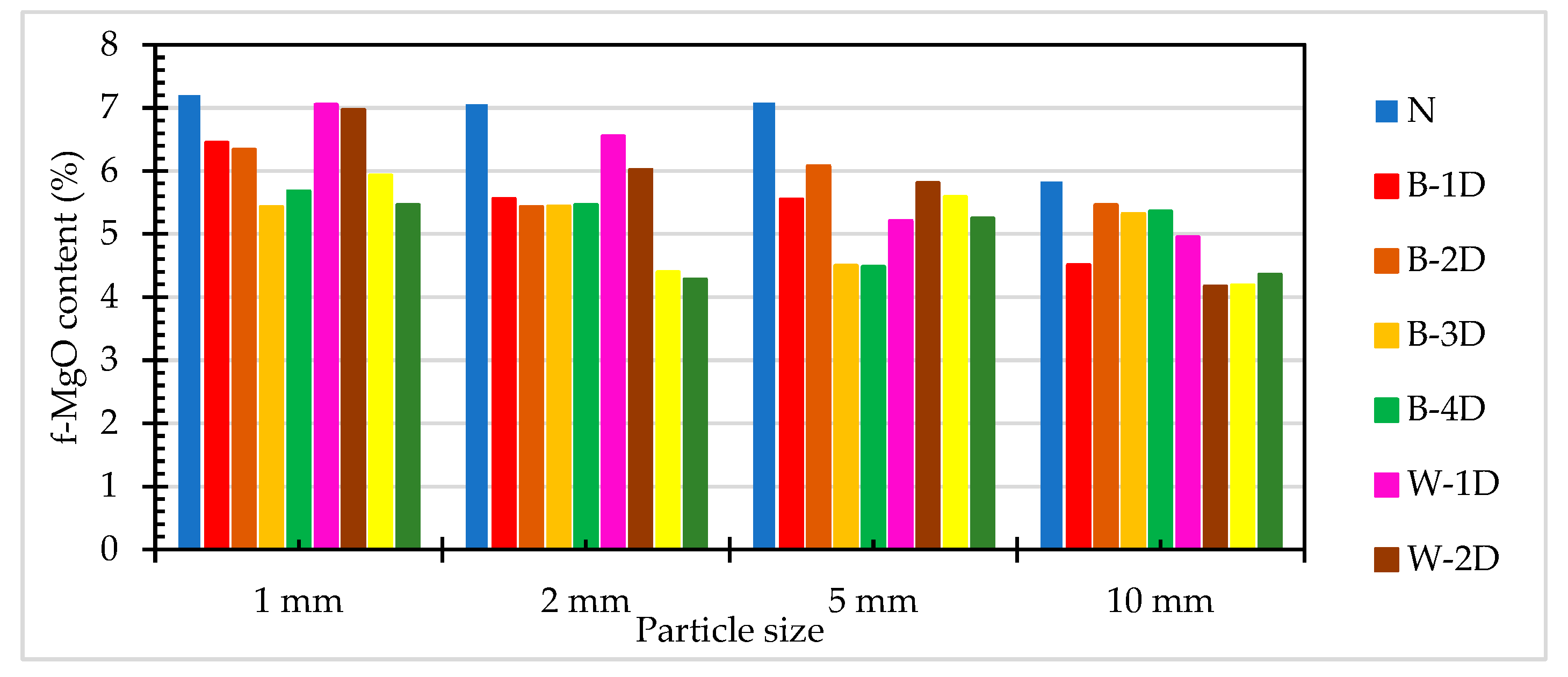

3.3. Results of the Free Magnesium Oxide Titration Test of ERSAs

3.4. Results of the pH Value Test of ERSAs

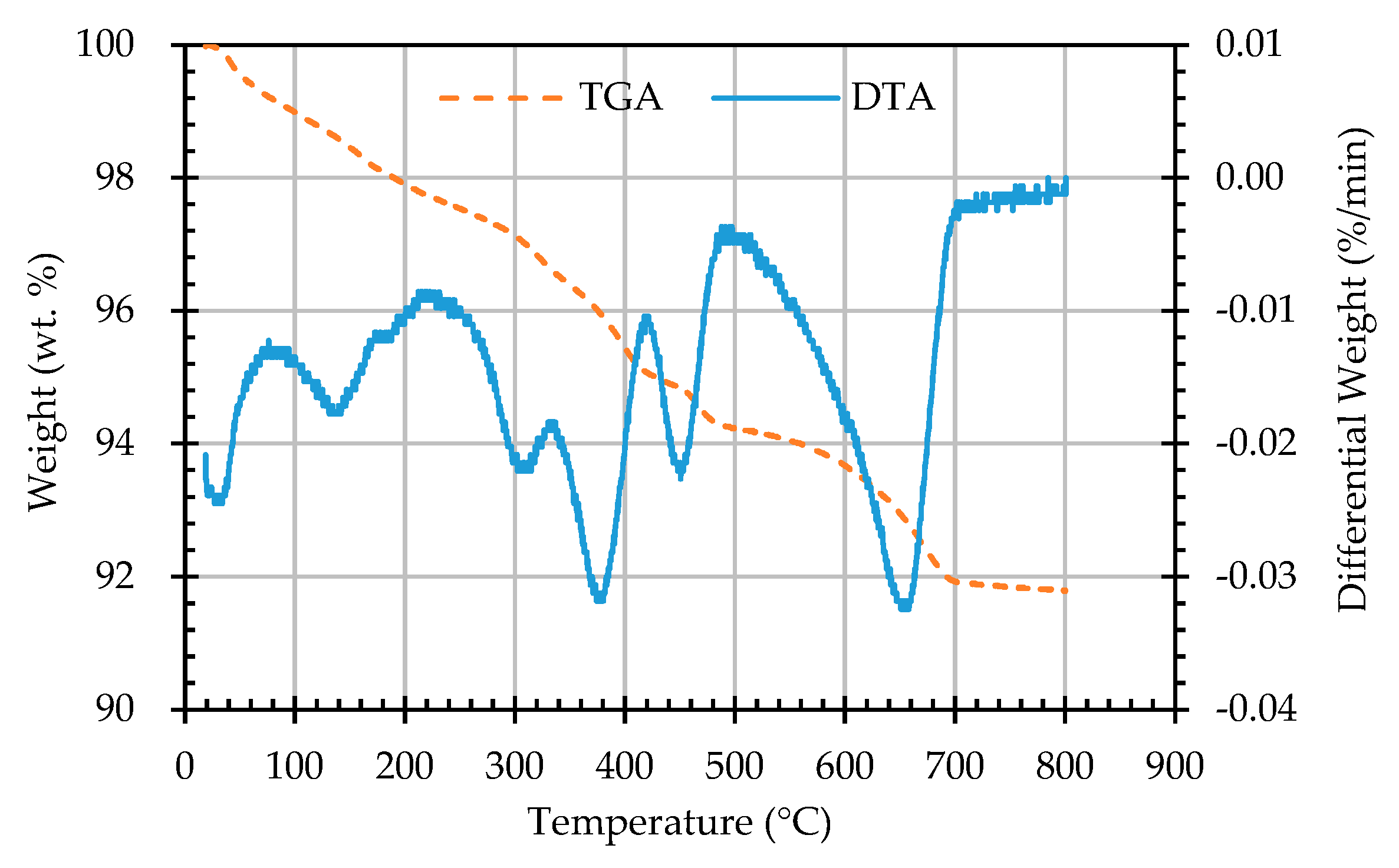

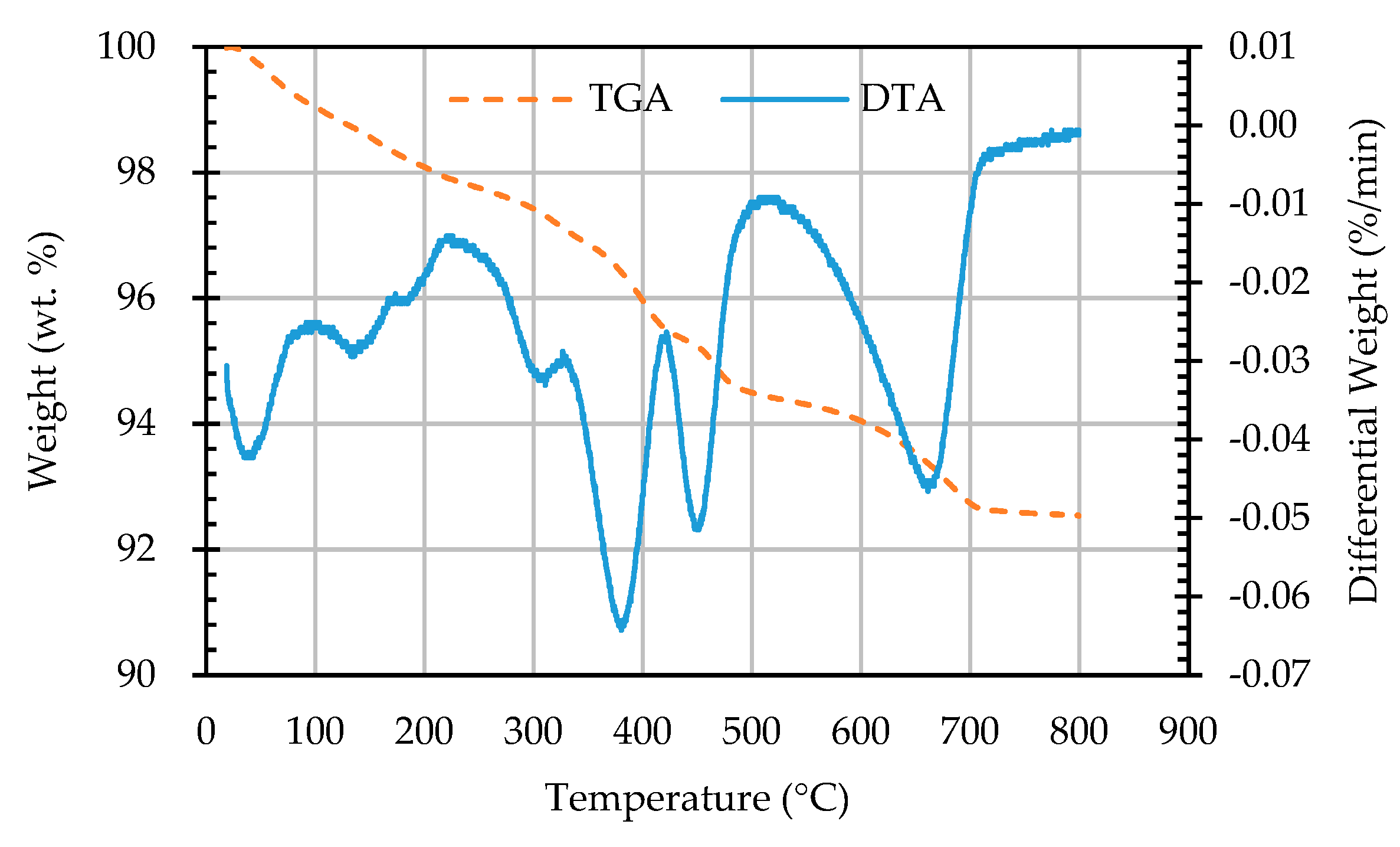

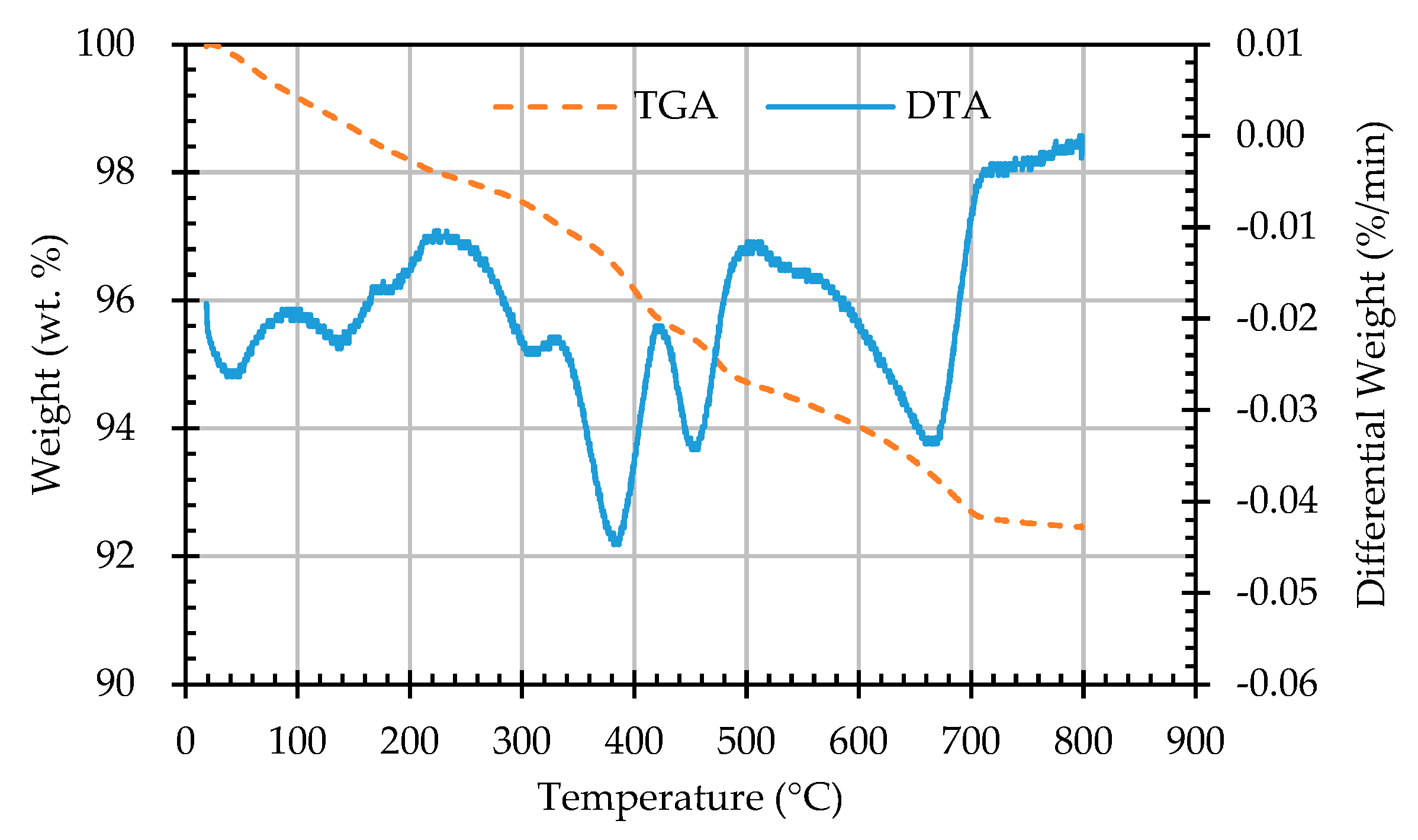

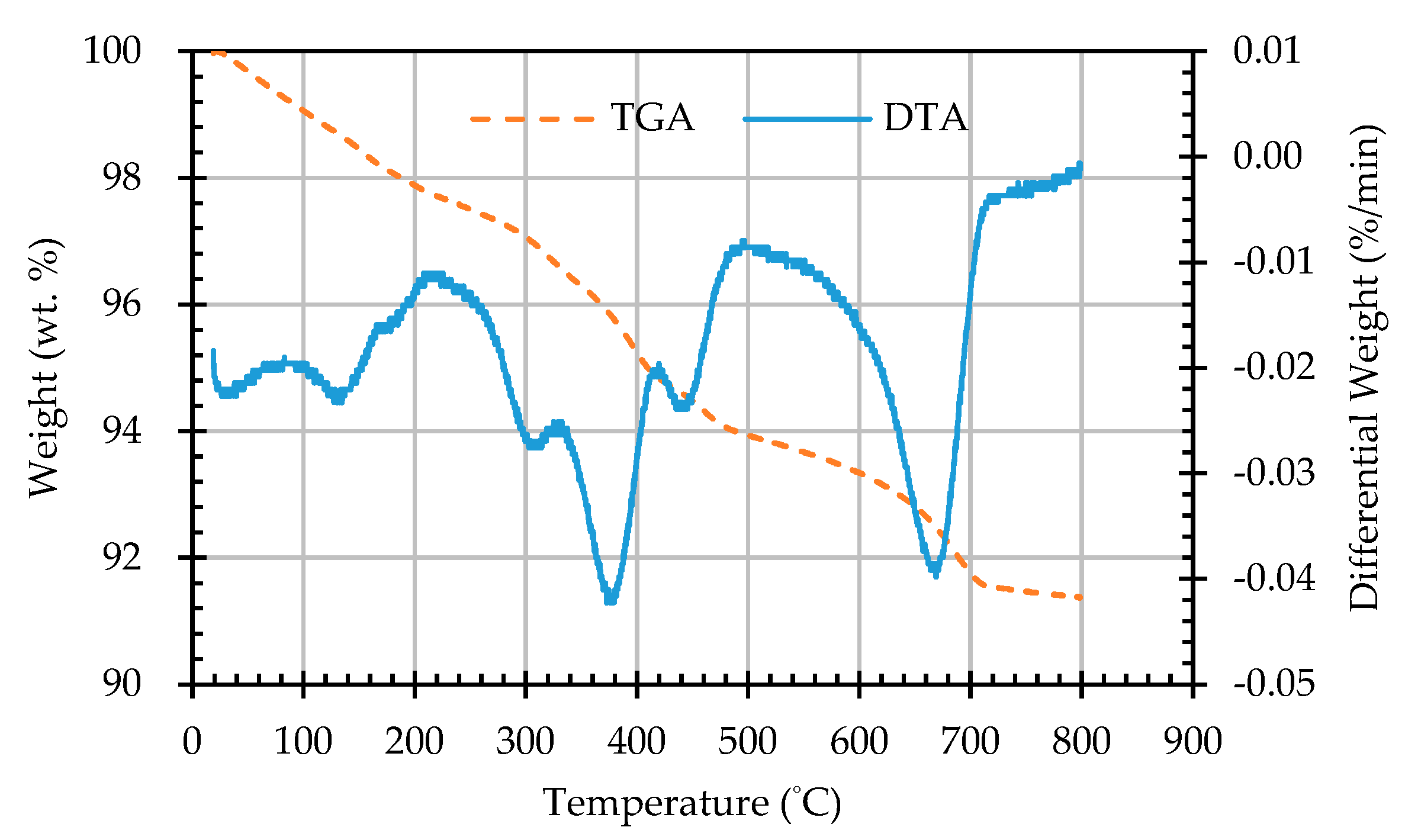

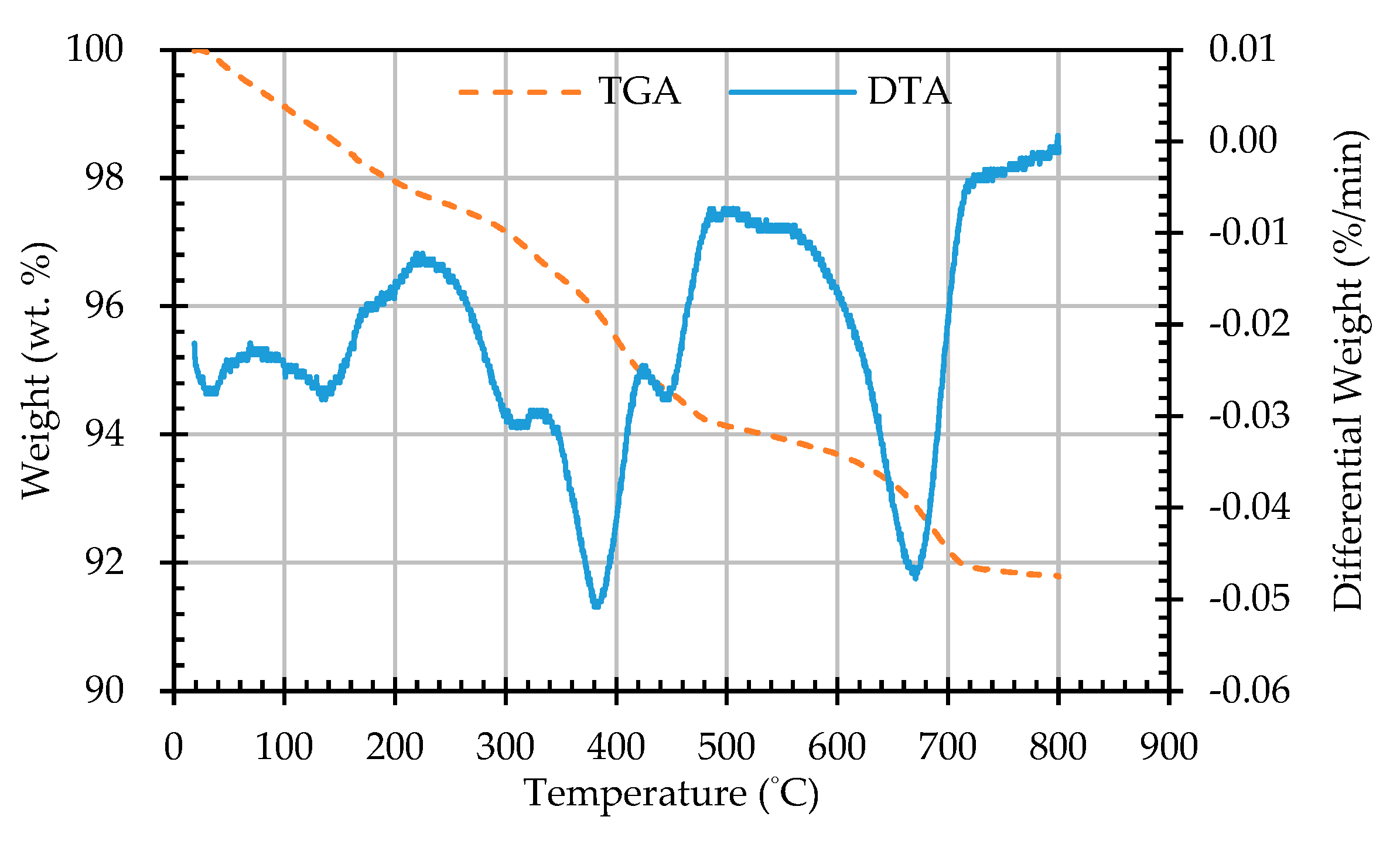

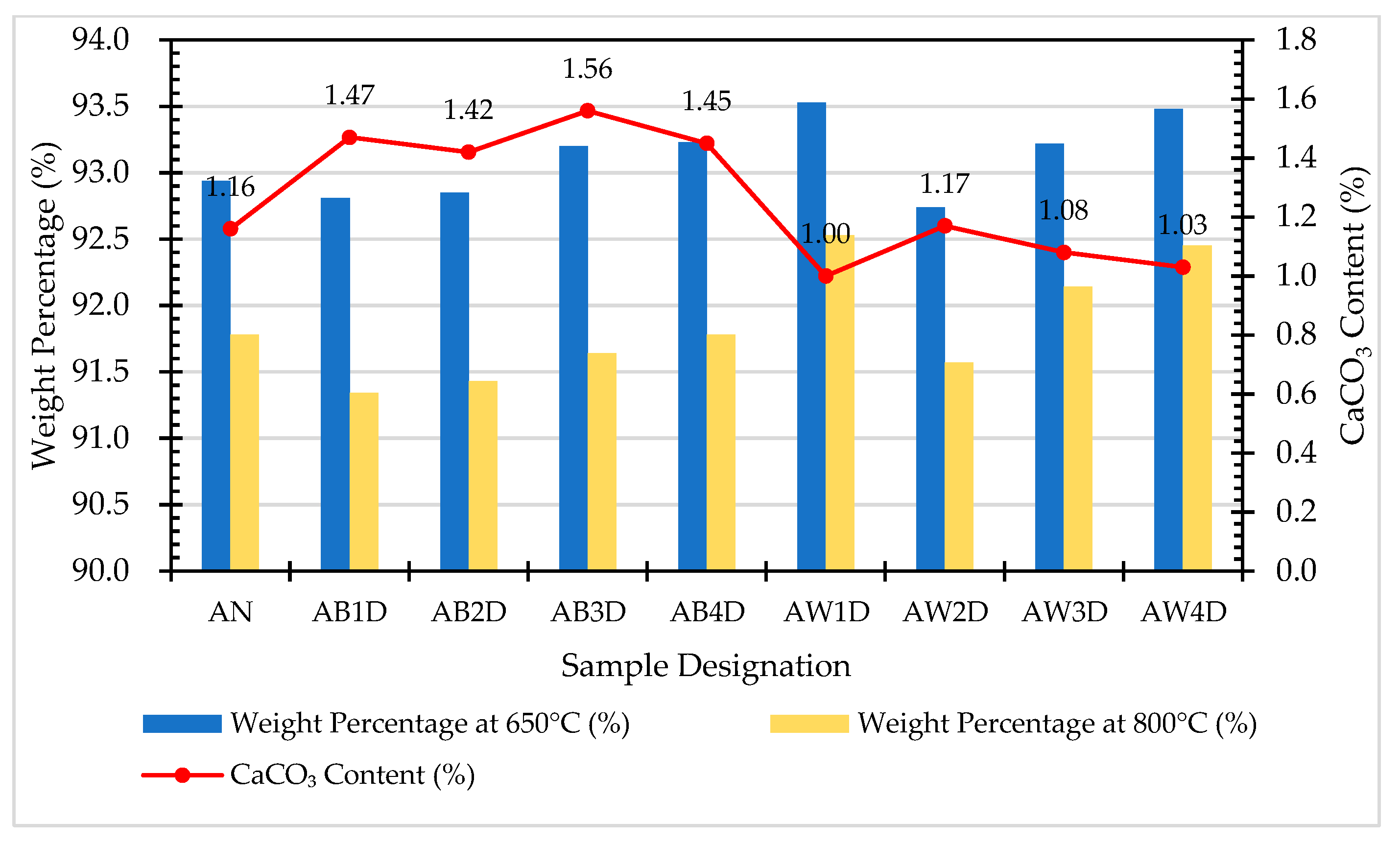

3.5. Results of Thermogravimetric Analysis of ERSAs

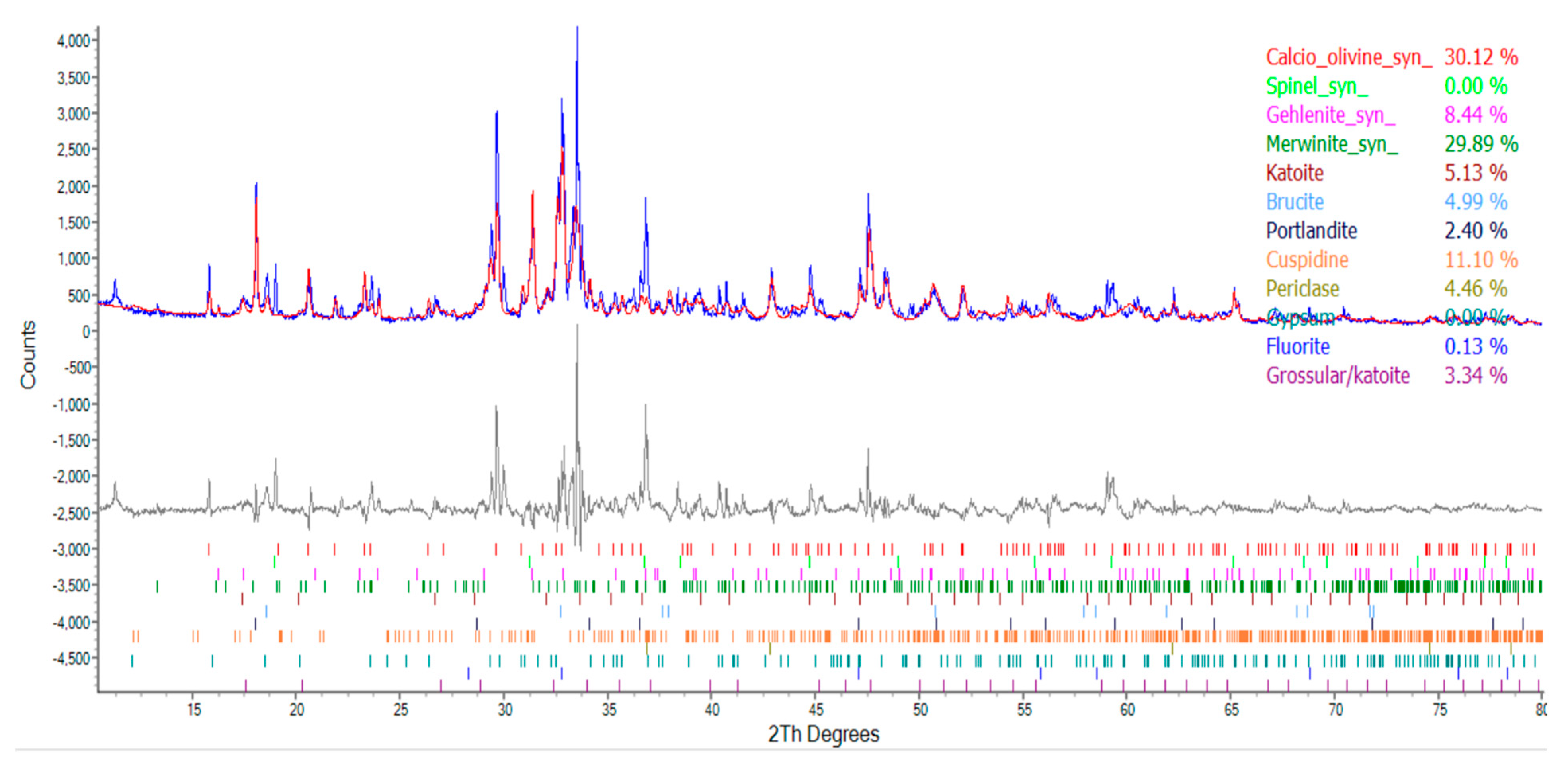

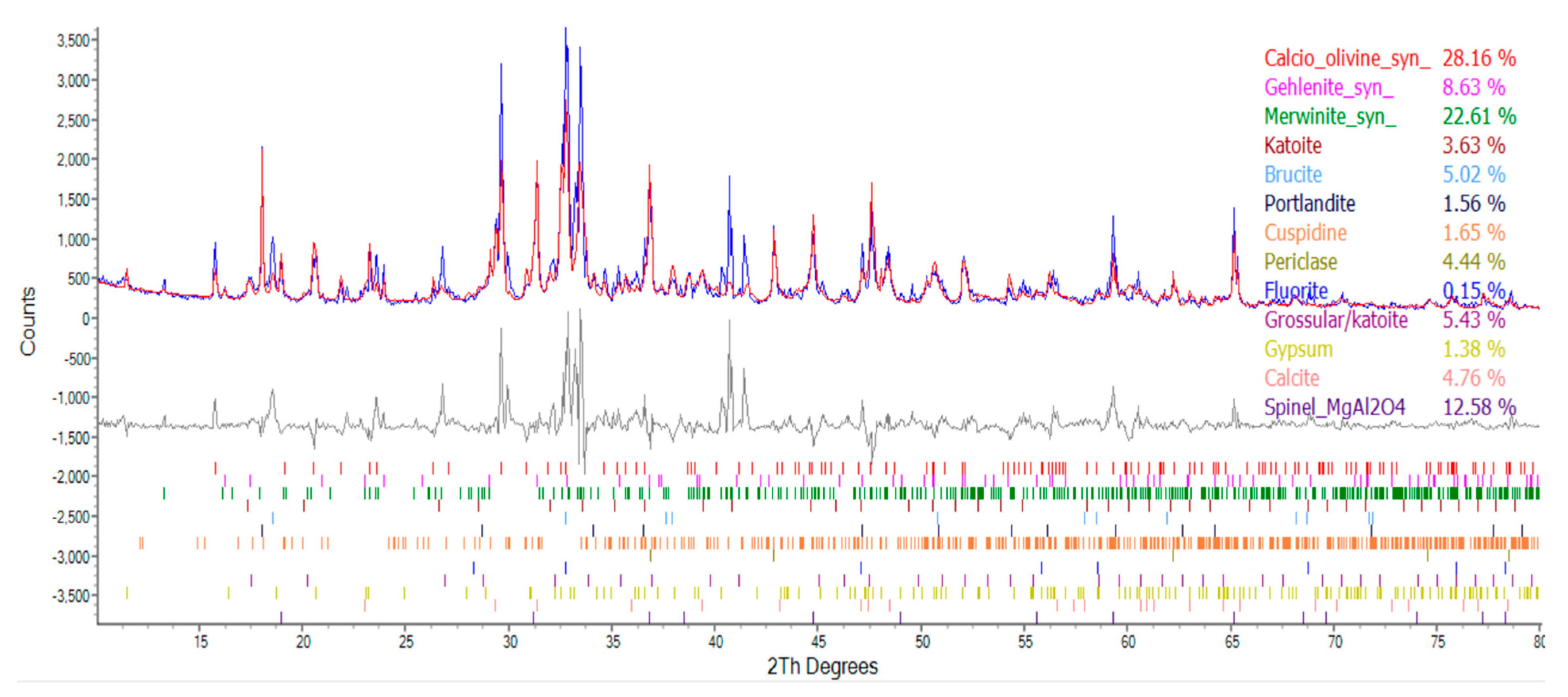

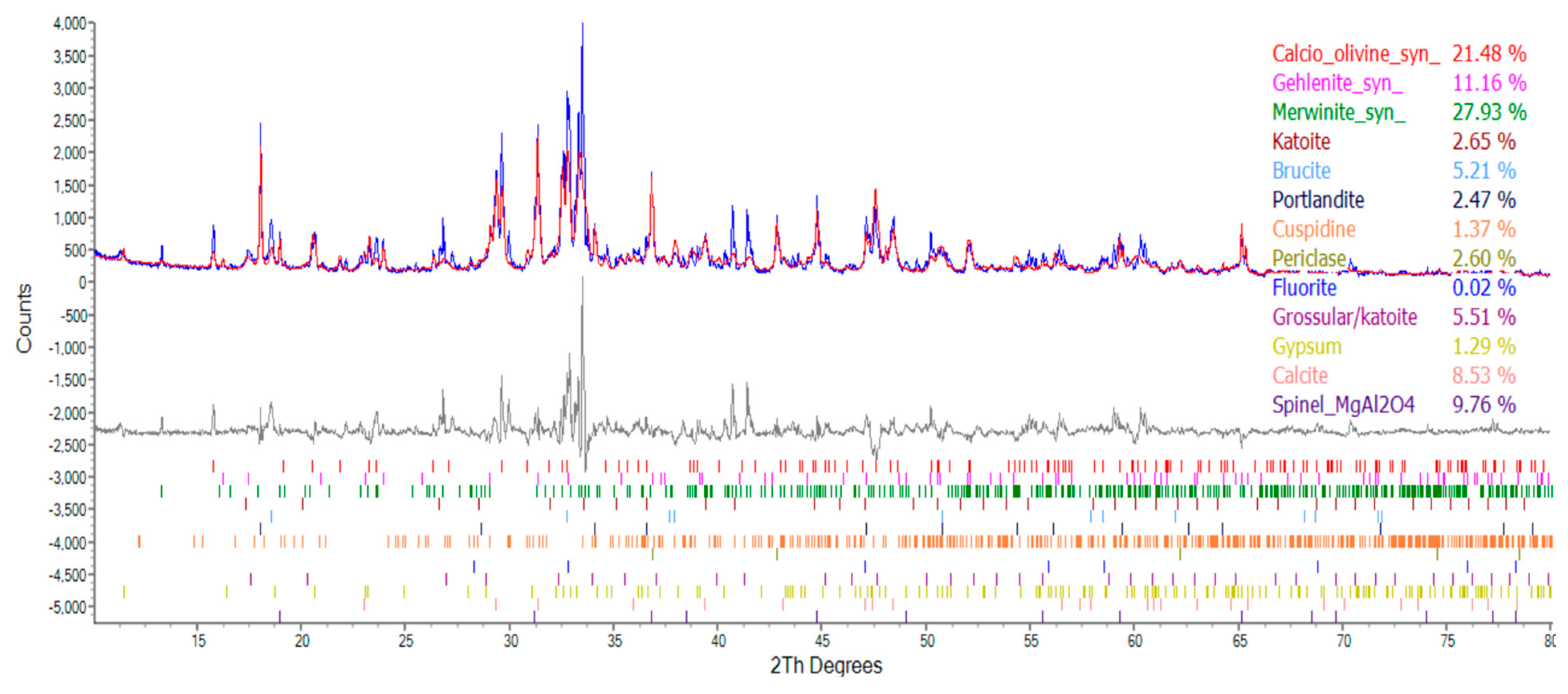

3.6. Results of XRD analysis of ERSAs

3.7. Properties of Concrete Produced with ERSAs

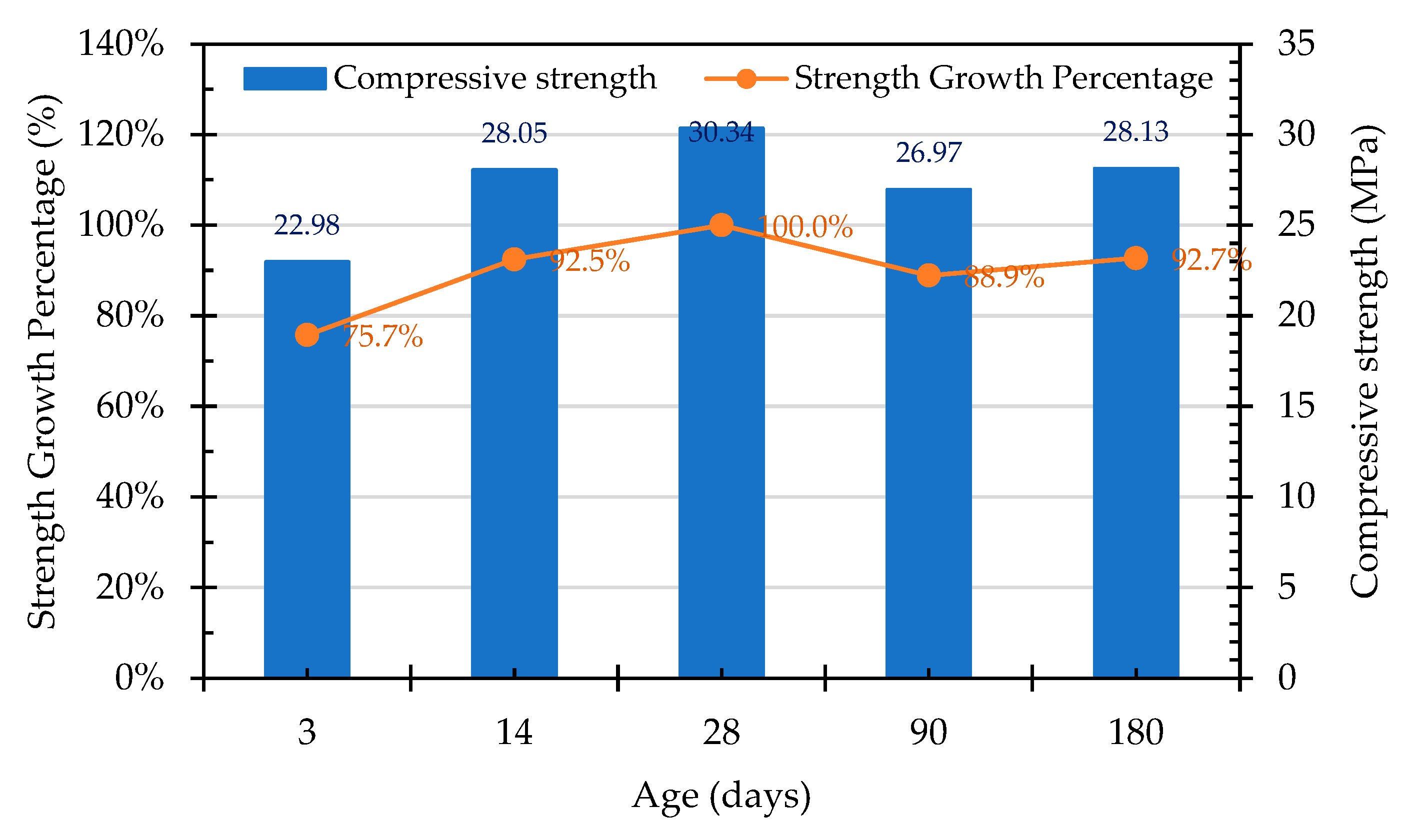

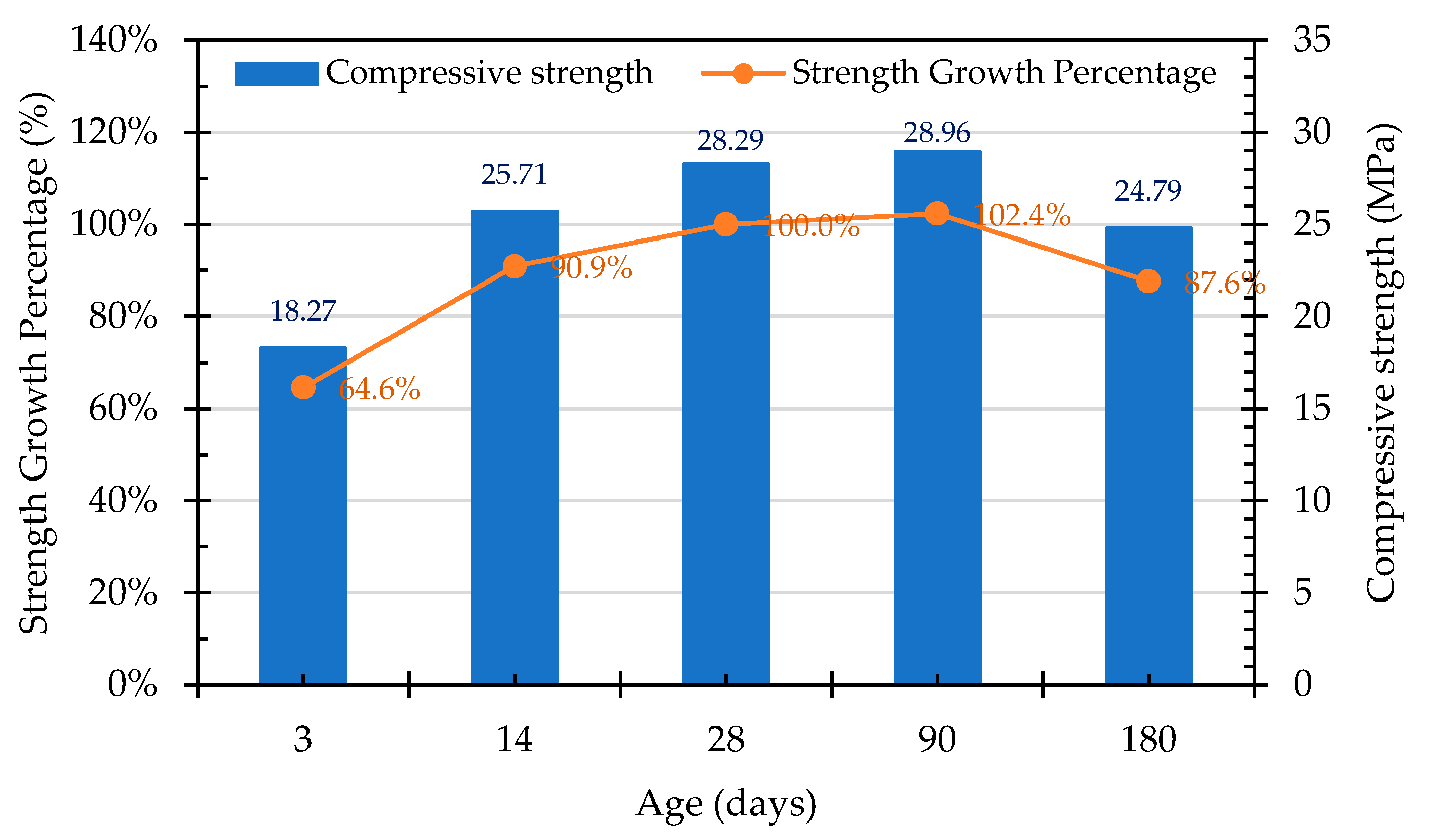

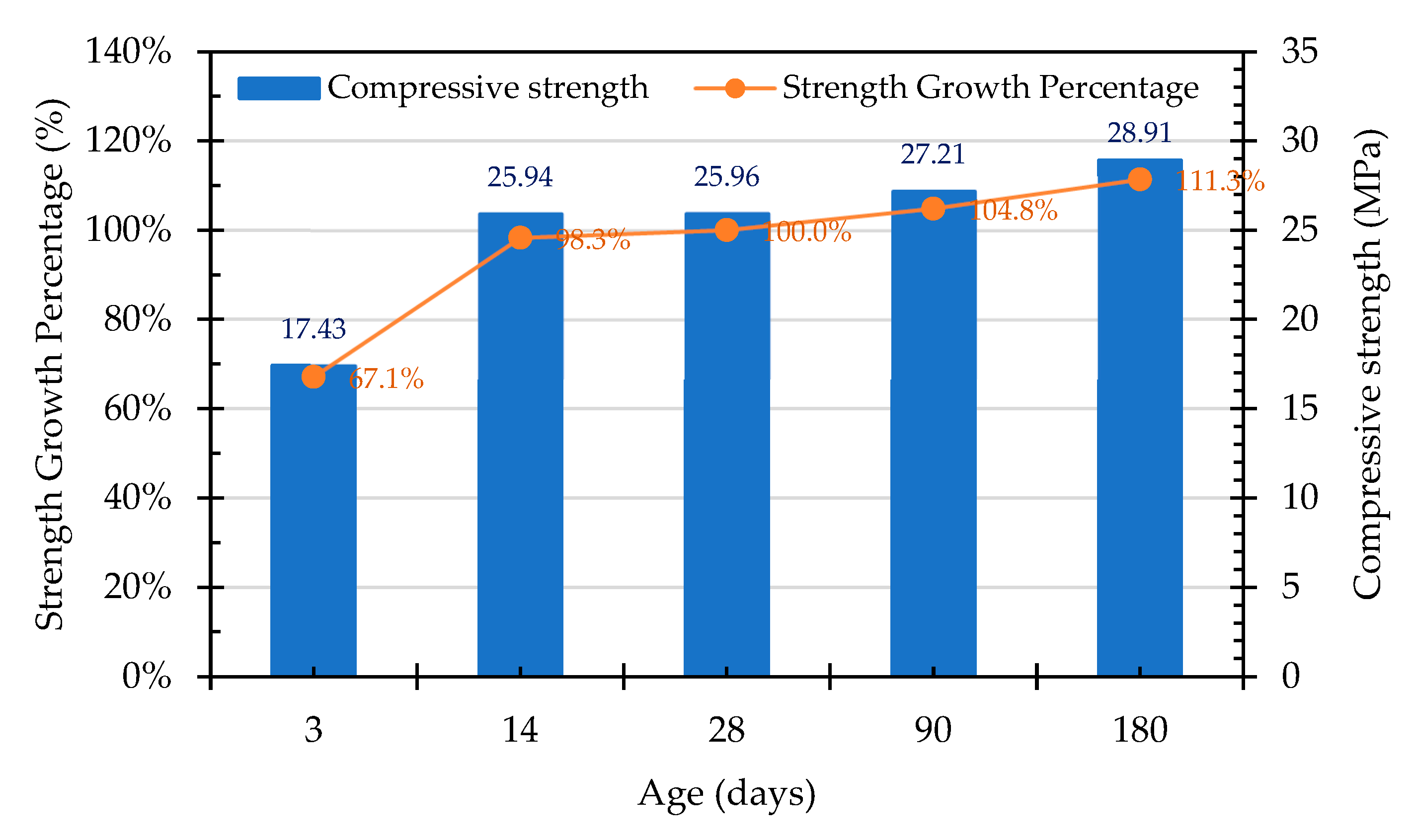

3.7.1. Compressive Strength of the Concrete Cylindrical Specimens

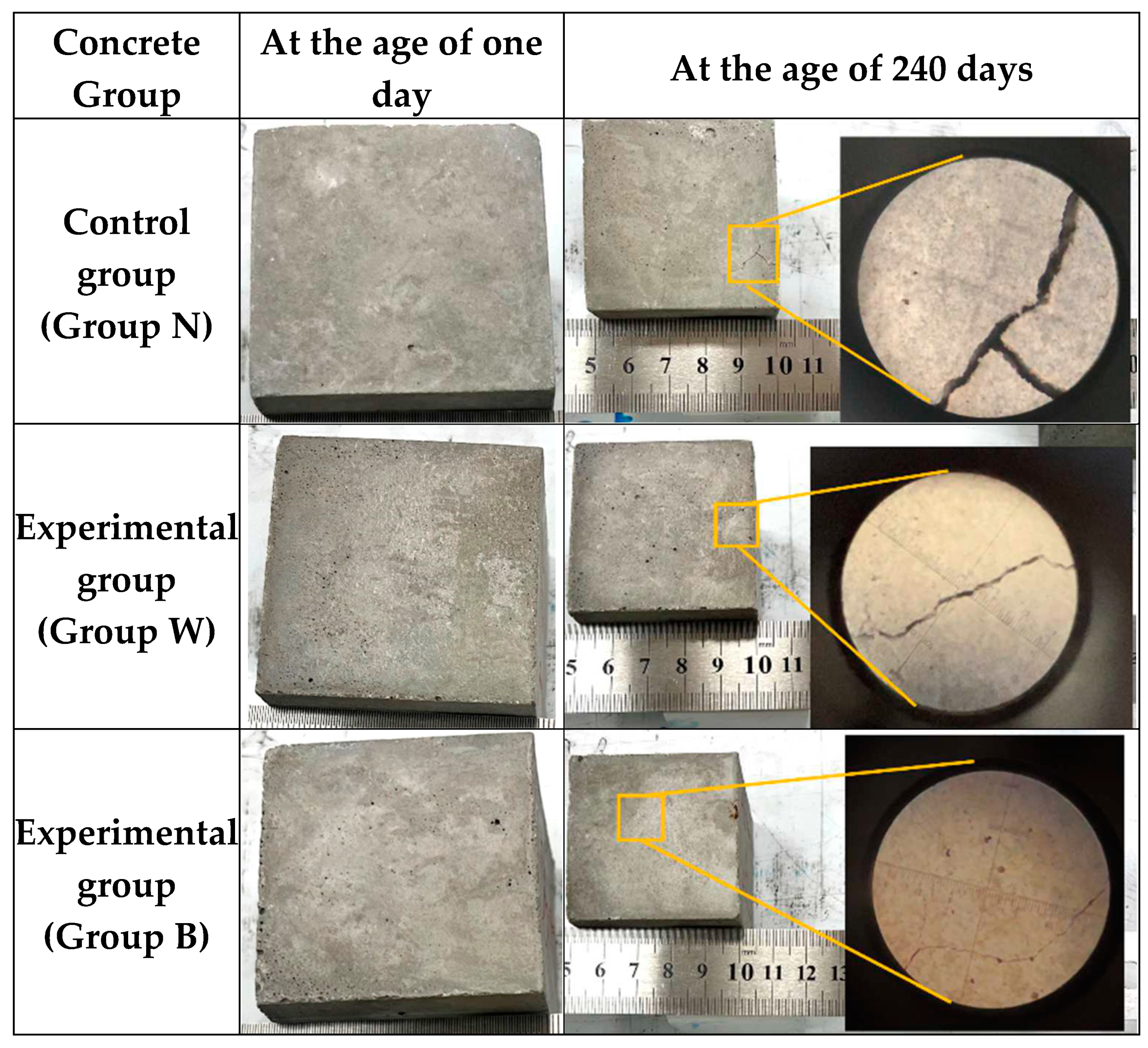

3.7.2. Long-Term Surface Observation of Concrete Cube Specimen

4. Conclusions

- The ERSAs stabilized by immersion in the bacterial solution had a potential expansion rate of approximately 0.28% to 0.36% after being hydrated for seven days, which is in line with Taiwan's waste recycling management regulations. Compared with the raw ERSAs, the reduction in expansion rate ranged from 32.1% to 47.2%.

- The f-CaO content of the ERSAs in the control group, experimental Group B, and experimental Group W ranged from 3.36% to 3.95%, 2.46% to 3.50%, and 2.82% to 3.86%, respectively. The results show that immersion in both a bacterial solution and water will reduce the f-CaO content of ERSAs and will achieve a stabilization effect. This is especially the case when considering the aggregates under the same particle size, e.g., the f-CaO content of experimental Group B was lower than that of experimental Group W.

- The pH value of the ERSAs in the control group was as high as 12.47. The pH value of the ERSAs of the experimental Group W, which was immersed in water, was similar to that of the control group, ranging from 11.615 to 12.28. In contrast, the pH value of the ERSAs of the experimental Group B, which was treated by immersion in a bacterial solution, was much lower, ranging from around 10.65 to 12.19. These results also proved that biomineralization technology can be used as a stabilizing treatment for ERSAs.

- The results of the TGA/DTA showed that the aggregates of the control group and the experimental group might contain CaCO3 compounds. The XRD results showed that the CaCO3 content in experimental Group B was 8.53%, while the CaCO3 content in experimental Group W was 4.76%. This result also showed that biomineralization can convert f-CaO into CaCO3 to achieve stabilization.

- The compressive strength of the concrete in the control group began to decrease after 28 days, which was evidently affected by the expansion of the raw reducing slag. The growth percentage of the Group W concrete was 102.4% at 90 days, but this decreased to 87.6% at 180 days. In contrast, the compressive strength of the Group B concrete continued to increase with its increase in age, the growth percentage of which was 104.8% at the age of 90 days and 111.3% at the age of 180 days. This result shows that ERSAs that are treated with MICP have a good stabilization effect, so the phenomenon of concrete volume expansion did not occur.

- The long-term surface observation results of the concrete specimens showed that the surface of the control group concrete had cracks or blast holes that could be clearly seen by the naked eye, and the specimens of the Group W concrete also had micro-cracks. In contrast, the cracks in concrete Group B were the subtlest, and the integrity of the surface could still be maintained until the age of 240 days; moreover, no expansion cracks or blast holes occurred.

- Biomineralization technology can effectively inhibit the expansion of reducing slag, and treated reducing slag can be used as a recycled aggregate in a general concrete mixture.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sukmak, P.; Sukmak, G.; De Silva, P.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Kassawat, S.; Suddeepong, A. The potential of industrial waste: Electric arc furnace slag (EAF) as recycled road construction materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 130393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Wang, S.; Lu, C.; Jiang, N.; Long, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, R. Environmental impact evaluation of an iron and steel plant in China: normalized data and direct/indirect contribution. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, I.; Santamaría, A.; Ruiz, E.; Ortega-López, V.; Manso, J.M. Electric arc furnace slag and its use in hydraulic concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 90, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasrawi, H. The use of steel slag aggregate to enhance the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete and retain the environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 54, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Eishah, S.I.; El-Dieb, A.S.; Bedir, M.S. Performance of concrete mixtures made with electric arc furnace (EAF) steel slag aggregate produced in the Arabian Gulf region. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 34, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Types of Steel slag, Taiwan Steel & Iron Industries Association, 2018 (http://steelslag.tsiia.org.tw).

- Jiang, Y.; Ling, T.C.; Shi, C.; Pan, S.Y. Characteristics of steel slags and their use in cement and concrete—a review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, J.; Komijani, S.; Shekarchi, M.; Ghazban, F. Durability of concrete mixtures containing Iranian electric arc furnace slag (EAFS) aggregates and lightweight expanded clay aggregates (LECA). Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, I.; Thomas, C.; Polanco, J.A.; Seti´en, J.; Sainz-Aja, J.A.; Tamayo, P. Durability of high-performance self-compacted concrete using electric arc furnace slag aggregate and cupola slag powder. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 127, 104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monosi, S.; Ruello, M.L.; Sani, D. Electric arc furnace slag as natural aggregate replacement in concrete production. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 66, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondi, L.; Bregoli, G.; Sorlini, S.; Cominoli, L.; Collivignarelli, C.; Plizzari, G. Concrete with EAF steel slag as aggregate: a comprehensive technical and environmental characterization. Compos. B Eng. 2016, 90, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, J.M.; Polanco, J.A.; Losanez, M.; Gonzalez, J.J. Durability of concrete made with EAF slag as aggregate. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2006, 28, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biskri, Y.; Achoura, D.; Chelghoum, N.; Mouret, M. Mechanical and durability characteristics of High Performance Concrete containing steel slag and crystalized slag as aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 150, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghool, F.; Arulrajah, A.; Du, Y.-J.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Chinkulkijniwat, A. Environmental impacts of utilizing waste steel slag aggregates as recycled road construction materials. Clean Techn. Environ. Policy 2017, 19, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K.; Randhawa, N.S.; Kumar, S. A review on characteristics of silico-manganese slag and its utilization into construction materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 176, 105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Mao, Y.J. Using autoclave pulverization technology to evaluate the expansion potentiality of electric arc furnace oxidizing slag. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhuang, S. The soundness of steel slag with different free CaO and MgO contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.H.; Sheen, Y.N.; Bui, Q.B. An assessment on volume stabilization of mortar with stainless steel slag sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 155, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, P.T.; Zakaria, S.K.; Salleh, S.Z.; Taib, M.A.A.; Mohd Sharif, N.; Abu Seman, A.; Mohamed, J.J.; Yusoff, M.; Yusoff, A.H.; Mohamad, M. Masri, M.N.; Mamat S. Assessment of Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) Steel Slag Waste’s Recycling Options into Value Added Green Products: A Review. Metals 2020, 10, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, A.; Palaniswamy, M.; Balaraju, S. A study on suitability of EAF oxidizing slag in concrete: an eco-friendly and sustainable replacement for natural coarse aggregate. Sci. World J. 2015, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Sha, A.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Hu, L.; Li, X. Utilization of steel slags to produce thermal conductive asphalt concretes for snow melting pavements. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 121197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasetto, M.; Baldo, N. Experimental evaluation of high performance base course and road base asphalt concrete with electric arc furnace steel slags. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 181, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Utilization of electric arc furnace oxidizing slag as concrete aggregates. Department of Civil Engineering, National Central University, Dissertation, 2003.

- Thomas, G.H.; Stephenson, I.M. The beta gamma dicalcium silicate phase transformation and its significance on air cooled stability. Silic. Ind. 1978, 9, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, C.P. Implementation of carbonation process for carbon dioxide capture and steelmaking slag utilization. National Taiwan University, 2014.

- Piemonti, A.; Conforti, A.; Cominoli, L.; Sorlini, S.; Luciano, A.; Plizzari, G. Use of Iron and Steel Slags in Concrete: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheanyichukwu, C.G.; Umar, S.A.; Ekwueme, P.C. A Review on Self-Healing Concrete Using Bacteria. Sustain. Struct. Mater. Int. J. 2018, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Seifan, M.; Berenjian, A. Microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation: a widespread phenomenon in the biological world. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 4693–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; McKittrick, J.; Meyers, M.A. Biological materials: Functional adaptations and bioinspired designs. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2012, 57, 1492–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, R.B.; Bazylinski, D.A. Biologically induced mineralization by bacteria. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003, 54, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Ghosh, A. Biomineralization, bacterial selection and properties of microbial concrete: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.; Dove, P. An overview of biomineralization processes and the problem of the vital effect. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003, 54, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Alonso, M.J.; Montañez-Hernandez, L.E.; Sanchez-Muñoz, M.A.; Franco, M.R.M.; Narayanasamy, R.; Balagurusamy, N. Microbially Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation (MICP) and Its Potential in Bioconcrete: Microbiological and Molecular Concepts. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, C.; Reid, R.P.; Braissant, O.; Decho, A.W.; Norman, R.S.; Visscher, P.T. Processes of carbonate precipitation in modern microbial mats. Earth Sci. Rev. 2009, 96, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krampitz, G.; Graser, G. Molecular mechanism of biomineralization in the formation of calcified shells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1988, 27, 145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Ju, T.; Meng, Y.; Han, S.; Lin, L.; Jiang, J. A review on the applications of microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation in solid waste treatment and soil remediation. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venuleo, S.; Laloui, L.; Terzis, D.; Hueckel, T.; Hassan, M. Microbially induced calcite precipitation effect on soil thermal conductivity. Géotechnique Letters 2016, 6, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achal, V.; Pan, X.L.; Zhang, D.Y. Remediation of copper-contaminated soil by Kocuria flava CR1, based on microbially induced calcite precipitation. Ecological Engineering 2011, 37, 1601–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Goyal, S.; Reddy, M.S. Influence of biogenic treatment in improving the durability properties of waste amended concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jroundi, F.; Schiro, M.; Ruiz-Agudo, E. Protection and consolidation of stone heritage by self-inoculation with indigenous carbonatogenic bacterial communities. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jin, P.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, W. Surface modification of recycled coarse aggregate based on Microbial Induced Carbonate Precipitation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Chen, M.-C.; Tang, C.-W. Research on Improving Concrete Durability by Biomineralization Technology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Chang, H.-L.; Tang, C.-W.; Yang, T.-Y. Application of Biomineralization Technology to Self-Healing of Fiber-Reinforced Lightweight Concrete after Exposure to High Temperatures. Materials 2022, 15, 7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xu, J. Application of microbial precipitation in self-healing concrete: A review on the protection strategies for bacteria. Construct. Build. Mater. 2021, 306, 124950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Jia, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Optimization of Sporulation and Germination Conditions of Functional Bacteria for Concrete Crack-Healing and Evaluation of their Repair Capacity. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 10938–10948. [Google Scholar]

- Kadapure, S.A.; Kulkarni, G.S.; Prakash, K.B. A laboratory investigation on the production of sustainable bacteria-blended fly ash concrete. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 42, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achal, V.; Pan, X.; Özyurt, N. Improved strength and durability of fly ash-amended concrete by microbial calcite precipitation. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, J.; Rodríguez-Robles, D.; Wang, J.; De Belie, N.; Del Pozo, J.M.M.; Guerra-Romero, M.I.; Juan-Valdés, A. Quality improvement of mixed and ceramic recycled aggregates by biodeposition of calcium carbonate. Construct. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, A.; Dri, M.; Hall, M.R.; Maroto-Valer, M. Waste materials for carbon capture and storage by mineralisation (CCSM)- A UK perspective. Applied Energy 2012, 99, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y.; Adhikari, R.; Chen, Y.-H.; Li, P.; Chiang, P.-C. Integrated and innovative steel slag utilization for iron reclamation, green material production and CO2 fixation via accelerated carbonation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y.; Chiang, P.-C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Tan, C.-S. Ex situ CO2 capture by carbonation of steelmaking slag coupled with metalworking wastewater in a rotating packed bed. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 3308–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, D.; Hu, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Ni, W. Coupling Mineralization and Product Characteristics of Steel Slag and Carbon Dioxide. Minerals 2023, 13, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Ren, L.; Xue, B.; Cao, T. Bio-mineralization on cement-based materials consuming CO2 from atmosphere. Construct. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese National Standards (CNS) 15311. Method of test for potential expansion of aggregates from hydration reactions. Bureau of Standards, Metrology and Inspection, Ministry of Economic Affairs, Taiwan.

- Long, Y.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Han, Z.; Shi, X. Determination of free calcium oxide in steel slag by EDTA complexometric titration. Metallurgical Analysis 2010, 30, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- CN101865856A. Method for analyzing and testing content of free magnesium oxide in steel slag. State Intellectual Property Office of the P.R.C, 2010.

- Motz, H.; Geiseler, J. Products of steel slags an opportunity to save natural resources. Waste Manage 2001, 21, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohmer, S.; Gertaud, M.; Neubauer, C.; Peltoniemi, M.; Schachermayer, E.; Tesar, M.; et al. (2008, March). Aggregates Case Study. Retrieved October 26, 2010, from Umweltbundesamt: http://susproc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/activities/waste/documents/Aggregates_Case_Stud y_Final_Report_UBA_080331.pdf.

- Zhang, Y.; Chang, J.; He, P. Carbonation reaction of free CaO and MgO in steel slag. Journal of Dalian University of Technology 2018, 58, 634–640. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Bouquet, E.; Leyssens, G.; Schönnenbeck, C.; Gilot, P. The decrease of carbonation efficiency of CaO along calcination–carbonation cycles: Experiments and modelling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 2136–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Heng, M.; Mo, L.; Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, D. Research Progress of Building Materials Prepared from the Carbonized Curing Steel Slag. Mater. Rep. 2019, 33, 2939–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, D.; Hu, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Ni, W. Coupling Mineralization and Product Characteristics of Steel Slag and Carbon Dioxide. Minerals 2023, 13, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test Variable | Variable Range and Sample Designation | |||||||||

| Particle size | 1-10 mm | 1 mm | 2 mm | 5 mm | 10 mm | |||||

| A | 1 | 2 | 5 | 10 | ||||||

| Stabilization method | Exposed to the air | Immersed in water | Immersed in a B. Pasteurii bacteria solution | |||||||

| N | W | B | ||||||||

| Immersion age | 1 day | 2 days | 3 days | 4 days | ||||||

| 1D | 2D | 3D | 4D | |||||||

| Mix Designation | Cement (kg/m3) |

Water (kg/m3) |

Coarse Aggregate (kg/m3) | Fine Aggregate (kg/m3) | Superplasticizer (kg/m3) | Note |

| MN | 508 | 197 | 865 | 721 | 10 | Untreated raw ERSA |

| MB | 508 | 197 | 865 | 721 | 10 | ERSA treated by immersion in a solution of B. pasteurii bacteria |

| MW | 508 | 197 | 865 | 721 | 10 | ERSA treated by immersion in a water tank |

| Sample Designation | Expansion Rate in the First 7 Days after Immersion in Water (%) | Specification Value (< 0.5%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-day | 1-day | 2-day | 3-day | 4-day | 5-day | 6-day | 7-day | ||

| AB-1D | 0 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.31 | < 0.5 |

| AB-2D | 0 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.28 | < 0.5 |

| AB-3D | 0 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.29 | < 0.5 |

| AB-4D | 0 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.36 | < 0.5 |

| AN | 0 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.53 | > 0.5 |

| Sample Designation | f-CaO Content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mm | 2 mm | 5 mm | 10 mm | |

| N | 3.95 | 3.73 | 3.48 | 3.36 |

| B-1D | 3.50 | 3.11 | 2.86 | 2.91 |

| B-2D | 3.25 | 3.15 | 2.58 | 2.68 |

| B-3D | 3.28 | 3.09 | 2.66 | 2.49 |

| B-4D | 2.97 | 2.87 | 2.56 | 2.46 |

| W-1D | 3.86 | 3.66 | 2.84 | 2.91 |

| W-2D | 3.74 | 3.69 | 2.86 | 2.87 |

| W-3D | 3.81 | 3.75 | 2.82 | 3.00 |

| W-4D | 3.74 | 3.65 | 2.82 | 3.08 |

| Sample Designation | f-MgO Content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mm | 2 mm | 5 mm | 10 mm | |

| N | 7.20 | 7.06 | 7.08 | 5.83 |

| B-1D | 6.45 | 5.56 | 5.55 | 4.51 |

| B-2D | 6.34 | 5.43 | 6.08 | 5.46 |

| B-3D | 5.43 | 5.44 | 4.50 | 5.32 |

| B-4D | 5.68 | 5.46 | 4.48 | 5.36 |

| W-1D | 7.05 | 6.55 | 5.21 | 4.95 |

| W-2D | 6.97 | 6.02 | 5.81 | 4.17 |

| W-3D | 5.93 | 4.39 | 5.59 | 4.19 |

| W-4D | 5.46 | 4.28 | 5.25 | 4.36 |

| Sample Designation | pH Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mm | 2 mm | 5 mm | 10 mm | |

| N | 12.47 | 12.47 | 12.47 | 12.47 |

| B-1D | 12.19 | 11.85 | 11.34 | 10.97 |

| B-2D | 11.97 | 11.13 | 11.18 | 11.17 |

| B-3D | 11.43 | 11.20 | 11.28 | 11.19 |

| B-4D | 11.32 | 10.68 | 10.65 | 11.47 |

| W-1D | 12.17 | 12.28 | 11.95 | 11.92 |

| W-2D | 11.85 | 11.89 | 11.65 | 11.80 |

| W-3D | 11.86 | 11.68 | 11.62 | 11.90 |

| W-4D | 11.94 | 11.62 | 11.61 | 11.81 |

| Sample Designation | Weight Percentage (%) | CaCO3 Content (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 650 °C | 800 °C | ||

| AN | 92.94 | 91.78 | 1.16 |

| AB1D | 92.81 | 91.34 | 1.47 |

| AB2D | 92.85 | 91.43 | 1.42 |

| AB3D | 93.2 | 91.64 | 1.56 |

| AB4D | 93.23 | 91.78 | 1.45 |

| AW1D | 93.53 | 92.53 | 1.00 |

| AW2D | 92.74 | 91.57 | 1.17 |

| AW3D | 93.22 | 92.14 | 1.08 |

| AW4D | 93.48 | 92.45 | 1.03 |

| Compound | Molecular Formula | Percentage of Ingredients (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group N | Group W | Group B | ||

| Calcio olivine | CaSiO4 | 30.12 | 28.16 | 21.48 |

| Spinel | MgAl2O | 0 | 12.58 | 9.76 |

| Gehlenite | Ca2Al[AlSi2O7] | 8.44 | 8.63 | 11.16 |

| Merwinite | Ca3Mg(SiO4)2 | 29.89 | 22.61 | 27.93 |

| Katoite | Ca3Al2(SiO4)3-X(OH)4X | 5.13 | 3.63 | 2.65 |

| Brucite | Mg(OH)2 | 4.99 | 5.02 | 5.21 |

| Portlandite | Ca(OH)2 | 2.40 | 1.56 | 2.47 |

| Cuspidine | Ca4(Si2O7)(OH)2 | 11.10 | 1.65 | 1.37 |

| Periclase | MgO | 4.46 | 4.44 | 2.60 |

| Gypsum | CaSO4‧2H2O | 0 | 1.38 | 1.29 |

| Fluorite | CaF2 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| Grossular | Ca3Al2(SiO4)0.69(OH)9.24 | 3.34 | 5.43 | 5.51 |

| Quartz | SiO2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Calcite | CaCO3 | 0 | 4.76 | 8.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).