Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

14 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Composition of Commercially Used Materials

3.2. Modifications in Composition

3.3. Indications for Use

3.4. Microleakage and Adhesion

4. Discussion

Funding

Acknowledgements

Declaration of Interests

References

- World Health Organization Sugars and Dental Caries. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sugars-and-dental-caries.

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Bernabé, E.; Dahiya, M.; Bhandari, B.; Murray, C.J.L.; Marcenes, W. Global Burden of Untreated Caries: A Systematic Review and Metaregression. J Dent Res 2015, 94, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, O.Y.; Lam, W.Y.H.; Wong, A.W.Y.; Duangthip, D.; Chu, C.H. Nonrestorative Management of Dental Caries. Dent J (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaman, R.; El-Housseiny, A.A.; Alamoudi, N. The Use of Pit and Fissure Sealants-a Literature Review. Dent J (Basel) 2017, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rošin-Grget, K.; Peroš, K.; Sutej, I.; Bašić, K. The Cariostatic Mechanisms of Fluoride. Acta Med Acad 2013, 42, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahovuo-Saloranta, A.; Forss, H.; Walsh, T.; Nordblad, A.; Mäkelä, M.; Worthington, H. V. Pit and Fissure Sealants for Preventing Dental Decay in Permanent Teeth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.T.; Crall, J.J.; Fontana, M.; Gillette, E.J.; Nový, B.B.; Dhar, V.; Donly, K.; Hewlett, E.R.; Quinonez, R.B.; Chaffin, J.; et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for the Use of Pit-and-Fissure Sealants: A Report of the American Dental Association and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Journal of the American Dental Association 2016, 147, 672–682.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, P. Comparative Evaluation of the Effect of Variation in Light-Curing Cycle with a Time Gap and Its Effect on Polymerization Shrinkage and Microhardness of Conventional Hydrophobic Sealants and Moisture-Tolerant Resin-Based Sealants: An in Vitro Study. Indian Journal of Multidisciplinary Dentistry 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaji, P.; Vaid, S.; Deep, S.; Mishra, S.; Srivastava, M.; Manjooran, T. In Vitro Evaluation of Shear Bond Strength and Microleakage of Different Pit and Fissure Sealants. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2016, 6, S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulpdent Corporation Embrace WetBond Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.pulpdent.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GHS-SDS-EMS.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Panigrahi, A. Microtensile Bond Strength of Embrace Wetbond Hydrophilic Sealant in Different Moisture Contamination: An In-Vitro Study. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH 2015, 9, ZC23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukyilmaz, E.; Savas, S. Evaluation of Shear Bond Strength, Penetration Ability, Microleakage and Remineralisation Capacity of Glass Ionomer-Based Fissure Sealants. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2016, 17, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arslanoğlu, Z.; Altan, H.; Kale, E.; Bılgıç, F.; Şahin, O. Nanomechanical Behaviour and Surface Roughness of New Generation Dental Fissure Sealants. Acta Phys Pol A 2016, 130, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muwaffaq Attash, Z.; Sami Gasgoos, Z. Shear Bond Strength of Four Types of Pit and Fissure Sealants (In Vitro Study). Int J Enhanc Res Sci Technol Eng 2018, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kucukyilmaz, E.; Savas, S.; Sener, Y.; Tosun, G.; Botsali, M. Polymerization Shrinkage of Six Different Fissure Sealants. Journal of Restorative Dentistry 2014, 2, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalizniak, I.; Palamara, J.E.A.; Wong, R.H.K.; Cochrane, N.J.; Burrow, M.F.; Reynolds, E.C. Ion Release and Physical Properties of CPP–ACP Modified GIC in Acid Solutions. J Dent 2013, 41, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkwatehy, W.M.A.; Bukhari, O.M. The Efficacy of Different Sealant Modalities for Prevention of Pits and Fissures Caries: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2019, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavic, L.; Gorseta, K.; Borzabadi-Farahani, A.; Tadin, A.; Glavina, D.; van Duinen, R.; Lynch, E. Influence of Thermo-Light Curing with Dental Light-Curing Units on the Microhardness of Glass-Ionomer Cements. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2016, 36, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.S.; Murthy, G.S. Comparative Evaluation of Shear Bond Strength of Three Commercially Available Glass Ionomer Cements in Primary Teeth. J Int Oral Health 2015, 7, 103. [Google Scholar]

- VOCO Ionofil Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.voco.dental/en/portaldata/1/resources/products/safety-data-sheets/gb/voco-ionofil-molar-ac_sds_gb.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Shebl, E.A.; Etman, W.M.; Genaid, Th.M.; Shalaby, M.E. Durability of Bond Strength of Glass-Ionomers to Enamel. Tanta Dental Journal 2015, 12, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultradent Ultraseal XT Brochure. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/wfptrcrbtkd0/6CDOVq0rW3Ia1bBseRnDYG/5de0b1fac706906d9c3577d36589e1ad/UltraSeal-XT-Sealant-Family-Sales-Sheet-1007280AR03.pdf.

- Ultradent UltraSeal XT plus Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://optident.co.uk/app/uploads/2018/03/UltraSeal-XT%C2%AE-plus-SDS-English.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Hannig, C.; Duong, S.; Becker, K.; Brunner, E.; Kahler, E.; Attin, T. Effect of Bleaching on Subsurface Micro-Hardness of Composite and a Polyacid Modified Composite. Dental Materials 2007, 23, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivoclar Vivadent Tetric EvoFlow Satety Data Sheet. Available online: https://us.vwr.com/assetsvc/asset/en_US/id/16490607/contents.

- Oglakci, B.; Arhun, N. The Shear Bond Strength of Repaired High-Viscosity Bulk-Fill Resin Composites with Different Adhesive Systems and Resin Composite Types. 2019, 33, 1584–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, H.; Hefnawy, S.; Nagi, S. Degree of Conversion and Polymerization Shrinkage of Low Shrinkage Bulk-Fill Resin Composites. Contemp Clin Dent 2019, 10, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi -Abrandabadi, A.; Najafi -Abrandabadi, S.; Ghasemi, A.; Kotick, P.G. Microshear Bond Strength of Composite Resins to Enamel and Porcelain Substrates Utilizing Unfilled versus Filled Resins. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2014, 11, 636. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, S.; Di Silvio, L.; MacKler, H.E.; Millar, B.J. Pre-Warming of Dental Composites. Dental Materials 2011, 27, e51–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.C.B.; Correr, G.M.; Borges, A.F.S.; Kantovitz, K.R.; Rontani, R.M.P. Minimally Invasive Dentistry: Bond Strength of Different Sealant and Filling Materials to Enamel. Oral Health Prev Dent 2005, 3, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kuşgöz, A.; Tüzüner, T.; Ülker, M.; Kemer, B.; Saray, O. Conversion Degree, Microhardness, Microleakage and Fluoride Release of Different Fissure Sealants. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2010, 3, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simsek Derelioglu, S.; Yilmaz, Y.; Celik, P.; Carikcioglu, B.; Keles, S. Bond Strength and Microleakage of Self-Adhesive and Conventional Fissure Sealants. Dent Mater J 2014, 33, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VOCO Grandio Seal Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.voco.dental/us/portaldata/1/resources/products/safety-data-sheets/us/grandio-seal_sds_us.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Bayrak, G.D.; Gurdogan-Guler, E.B.; Yildirim, Y.; Ozturk, D.; Selvi-Kuvvetli, S. Assessment of Shear Bond Strength and Microleakage of Fissure Sealant Following Enamel Deproteinization: An in Vitro Study. J Clin Exp Dent 2020, 12, e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOCO Fissurit FX Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.voco.dental/au/portaldata/1/resources/products/safety-data-sheets/au/fissurit-fx_sds_au.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Güngör, özge E.; Erdogan, Y.; Yalçin-Güngör, A.; Alkiş, H. Comparative Evaluation of Shear Bond Strength of Three Flowable Compomers on Enamel of Primary Teeth: An in-Vitro Study. J Clin Exp Dent 2016, 8, e322. [CrossRef]

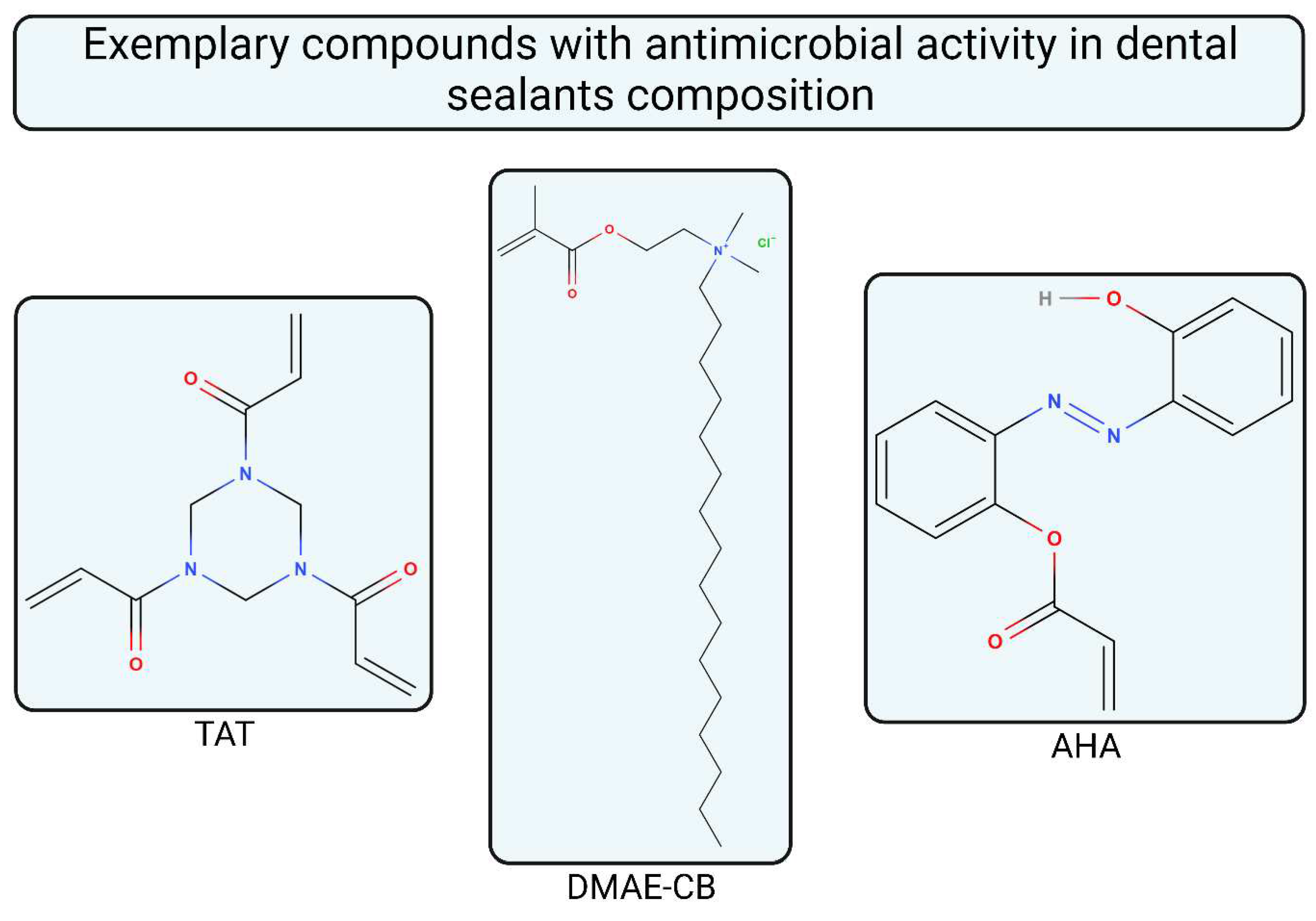

- Garcia, I.M.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Rücker, V.B.; Nunes, J.; Visioli, F.; Collares, F.M. Physicochemical and Biological Evaluation of a Triazine-Methacrylate Monomer into a Dental Resin. J Dent 2021, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, F.; Wu, D.; Ma, S.; Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, J. The Effect of an Antibacterial Monomer on the Antibacterial Activity and Mechanical Properties of a Pit-and-Fissure Sealant. Journal of the American Dental Association 2011, 142, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, D.I.; Powell, A.; Kehe, G.M.; Schurr, M.J.; Nair, D.P.; Puranik, C.P. Acrylated Hydroxyazobenzene Copolymers in Composite-Resin Matrix Inhibits Streptococcus Mutans Biofilms In Vitro. Pediatr Dent 2021, 43, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mori, D.I.; Schurr, M.J.; Nair, D.P. Selective Inhibition of Streptococci Biofilm Growth via a Hydroxylated Azobenzene Coating. Adv Mater Interfaces 2020, 7, 1902149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantovitz, K.R.; Pascon, F.M.; Nociti, F.H.; Tabchoury, C.P.M.H.; Puppin-Rontani, R.M. Inhibition of Enamel Mineral Loss by Fissure Sealant: An in Situ Study. J Dent 2013, 41, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejàre, I. Indications for Fissure Sealants and Their Role in Children and Adolescents. Dent Update 2011, Dec, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi-Pégurier, L.; Bertrand, M.F.; Genovese, O.; Rocca, J.P.; Muller-Bolla, M. Microleakage of Resin-Based Sealants after Er:YAG Laser Conditioning. Lasers Med Sci 2007, 22, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summitt, J.B.; Robbins, J.W.; Hilton, T.J.; Schwartz, R.S. Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry A Contemporary Approach; 2006; Vol. 5; ISBN 9781119130536.

- Cardoso, M. V.; De Almeida Neves, A.; Mine, A.; Coutinho, E.; Van Landuyt, K.; De Munck, J.; Van Meerbeek, B. Current Aspects on Bonding Effectiveness and Stability in Adhesive Dentistry. Aust Dent J 2011, 56, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkona Arkona Fissure Sealant Brochure. Available online: https://arkonadent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/arkonadent-lak-szczelinowy-kompendium-wiedzy.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Ivoclar Vivadent Helioseal F Instruction of Use. Available online: https://www.dentaltix.com/en/sites/default/files/helioseal_1.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- SDI Conseal F Brochure. Available online: https://www.sdi.com.au/pdfs/brochures/au/conseal%20f_sdi_brochures_au.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Unal, M.; Hubbezoglu, I.; Zan, R.; Kapdan, A.; Hurmuzlu, F. Effect of Acid Etching and Different Er:YAG Laser Procedures on Microleakage of Three Different Fissure Sealants in Primary Teeth after Aging. Dent Mater J 2013, 32, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlü, Z.A.; Dönmez, N.; Tüzüner, T.; Odabaş, M.E.; Hurt, A.P.; Coleman, N.J. The Impact of Er:YAG Laser Enamel Conditioning on the Microleakage of a New Hydrophilic Sealant—UltraSeal XT® HydroTM. Lasers Med Sci 2016, 31, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, E.; Yazici, A.R.; Baseren, M.; Gorucu, J. Comparison of Acid versus Laser Etching on the Clinical Performance of a Fissure Sealant: 24-Month Results. Oper Dent 2013, 38, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlü, Z.A.; Hurt, A.P.; Dönmez, N.; Coleman, N.J. Effect of Er:YAG Laser Enamel Conditioning and Moisture on the Microleakage of a Hydrophilic Sealant. Odontology 2018, 106, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzano, G.F.; Ingenito, A.; Alcidi, B.; Sangianantoni, G.; Schiavone, M.G.; Cantile, T. In Vitro Performance of Ultrasound Enamel Preparation Compared with Classical Bur Preparation on Pit and Fissure Sealing. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2017, 18, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memarpour, M.; Shafiei, F. The Effect of Antibacterial Agents on Fissure Sealant Microleakage: A 6-Month in Vitro Study. Oral Health Prev Dent 2014, 12, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mézquita-Rodrigo, I.; Scougall-Vilchis, R.J.; Moyaho-Bernal, M.A.; Rodríguez-Vilchis, L.E.; Rubio-Rosas, E.; Contreras-Bulnes, R. Using Self-Etch Adhesive Agents with Pit and Fissure Sealants. In Vitro Analysis of Shear Bond Strength, Adhesive Remnant Index and Enamel Etching Patterns. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry 2022, 23, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotta M, Bresciani P, Moura SK, Grande RH, Hilgert LA, Baratieri LN, Loguercio AD, R.A. Effects of Phosphoric Acid Pretreatment and Substitution of Bonding Resin on Bonding Effectiveness of Self-Etching Systems to Enamel. J Adhes Dent. 2007, 9, 537–545. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, A.; Barkmeier, W.; Takamizawa, T.; Latta, M.; Miyazaki, M. The Effect of Phosphoric Acid Pre-Etching Times on Bonding Performance and Surface Free Energy with Single-Step Self-Etch Adhesives. Oper Dent 2016, 41, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltoukhy, R.I.; Elkaffas, A.A.; Ali, A.I.; Mahmoud, S.H. Indirect Resin Composite Inlays Cemented with a Self-Adhesive, Self-Etch or a Conventional Resin Cement Luting Agent: A 5 Years Prospective Clinical Evaluation. J Dent 2021, 112, 103740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, X.; Li, W.; Ling, C.; Fok, A. Effect of Artificial Aging on the Bond Durability of Fissure Sealants. J Adhes Dent 2013, 15, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M. V.; De Almeida Neves, A.; Mine, A.; Coutinho, E.; Van Landuyt, K.; De Munck, J.; Van Meerbeek, B. Current Aspects on Bonding Effectiveness and Stability in Adhesive Dentistry. Aust Dent J 2011, 56, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, J.; O’Connell, A.C. A Randomised Clinical Trial on the Use of Intermediate Bonding on the Retention of Fissure Sealants in Children. Int J Paediatr Dent 2016, 26, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.; Paglia, L. Dental Sealants Part 1: Prevention First. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2018, 19, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olczak-Kowalczyk, D.; Szczepańska, J.; Kaczmarek, U. Współczesna Stomatologia Wieku Rozwojowego, 1st ed.; Med Tour Press: Otwock, 2017; ISBN 978-83-87717-26-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lubojanski, A.; Piesiak-Panczyszyn, D.; Zakrzewski, W.; Dobrzynski, W.; Szymonowicz, M.; Rybak, Z.; Mielan, B.; Wiglusz, R.J.; Watras, A.; Dobrzynski, M. The Safety of Fluoride Compounds and Their Effect on the Human Body—A Narrative Review. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.T.; Tampi, M.P.; Graham, L.; Estrich, C.; Crall, J.J.; Fontana, M.; Gillette, E.J.; Nový, B.B.; Dhar, V.; Donly, K.; et al. Sealants for Preventing and Arresting Pit-and-Fissure Occlusal Caries in Primary and Permanent Molars: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials - A Report of the American Dental Association and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatr Dent 2016, 38, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Barrera, M.Á.; De Jesús Saucedo-Molina, T.; Scougall-Vilchis, R.J.; De Lourdes Márquez-Corona, M.; Medina-Solís, C.E.; Maupomé, G. Comparison of Two Types of Pit and Fissure Sealants in Reducing the Incidence of Dental Caries Using a Split-Mouth Design. Acta Stomatol Croat 2021, 55, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosior, P.; Dobrzyński, M.; Korczyński, M.; Herman, K.; Czajczyńska-Waszkiewicz, A.; Kowalczyk-Zając, M.; Piesiak-Pańczyszyn, D.; Fita, K.; Janeczek, M. Long-Term Release of Fluoride from Fissure Sealants—In Vitro Study. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 2017, 41, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horst, J.A.; Tanzer, J.M.; Milgrom, P.M. Fluorides and Other Preventive Strategies for Tooth Decay. Dent Clin North Am 2018, 62, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Product Name | Abbreviation | Manufacturer | Composition | Fluoride Presence | Shear bond Strength [MPa] | Hardness [HK] or [HV] |

Shrinkage [%] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helioseal F | HF | Ivoclar Vivadent, Lichtenstein | Bis-GMA, dimetacrylates fluorosilicate glass, silica, titanium dioxide, initiators and stabilizers | Yes | 13.7 ± 7.0 | 19.3 HV | 3.98 | [8,9] |

| Embrace Wetbond | EW | Pulpdent, United States | Uncured acrylate ester monomers 55-60%, amorphous silica 5 %, sodium fluoride <2% | Yes | 21.7 ± 2.0 | 23.9 HV | 3.45 | [8,10,11] |

| Fuji Triage | FT | GC Cooperation, Japan | Glass-ionomer, aluminofluorosilicate glass, polyacrylic acid, distilled water, polybase carboxylic acid | Yes | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 52.0 ± 1.0 HV* | - | [12,13] |

| Smart Seal loc F | SSLF | Detax, Germany | bis(methacryloxyethyl) hydrogen phosphate,2-propenoic acid, 2-methyl-2-hydroxyethyl ester, phosphate,2-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate | Yes | 9.5 ± 1.4 | - | 5.06 ± 1.20 | [14,15] |

| Fuji VII EP | F7E | GC Cooperation, Japan | Fluoroaluminosilicate glass, CPP-ACP, pigment, distilled water, polyacrylic acid, polybase carboxylic acid | Yes | 5.0 ± 1.7 | 47.1 ± 6.0 HV | - | [12,16] |

| GCP Glass Seal | GCP | GCP Dental, Netherlands | Nanoparticles glass ionomer-based material | Yes | - | 50.0 ± 1.5 HV | - | [13,17] |

| Ketac Molar | KM | 3M ESPE, Germany | Al-Ca-La fluorosilicate glass, 5% copolimeracid (acrylic and maleic), polyacril enoic acid, tartaric acid, water | Yes | 4.8 ± 1.0 | 89.9 ± 4.2 HV | - | [18,19] |

| Voco Ionofil Molar AC Quick | IMAC | Voco, Germany | Water, pure polyacrid acid, (+)-tartaric acid, aluminofluorosilicate glass and pigments | Yes | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 79.9 ± 2.1 HV | - | [18,20,21] |

| Equia Fil | EQF | GC Cooperation, Japan | Polyacrylic acid, aluminosilicate glass, distilled water | No | - | 99.3 ± 4.5 HV | - | [18] |

| UltraSeal XT plus | USXT | Ultradent, USA | Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate 10-25%, diurethane dimethacrylate 2.5-10%, aluminium oxide 2.5-10%, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate < 2.5%, amine methacrylate < 2.5%, organophosphine oxide < 2.5%, sodium monofluorophosphate < 0.1% | Yes | 42.7 | 27.6 HK | 5.98 | [22,23] |

| Conseal F | CF | SDI, Australia | Urethane dimethacrylate base 7% filled with a submicron filler size of 0.04 µm | No | 14.0 ± 0.9 | - | - | [14] |

| Tetric Flow | TF | Vivadent | Bis-GMA (10-25%), urethane dimethacrylate (10-25%), ytterbium trifluoride, 1,10-decandiol dimethacrylate (2.5-10%), diphenyl(2,4,6- trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide (0.1-2.5%), 2-(2-Hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)-benzotriazol; 2-(2H-Benzotriazol-2-yl)-p-kresol (0.1-1.0%) | Yes | 16.8 ± 2.7 | 34.0 HV** | - | [9,24,25] |

| Tetric Evo Ceram | TEC | Vivadent | Dimethacrylate co-monomers (17-18 wt.%), barium glass, ytterbium trifluorid, mixed oxides and prepolymers (82-83 wt.%) | Yes | 20.7 ± 7.2 | 51.0 HV** | 1.95 ± 0.03 | [24,26,27] |

| Wave | WV | SDI, Australia | UDMA, strontium glass | No | 24.6 ± 1.5 | - | 5.00 | [28,29] |

| Clinpro Sealant | CS | 3M ESPE, Germany | TEGDMA, bisphenol A digilycidyl ether dimethacrylate, tetrabuttylammonium tetrafluoroborat, silane-treated silica |

Yes | 12.8 ± 8.3 | 21.5 ± 0.2 HV | 6.60 ± 1.54 | [15,30,31] |

| Grandio Seal | GS | Voco, Germany | Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (10-25%), fumed silica (5-10%), Bis-GMA (2.5-5%) | No | 42.6 ± 3.2 | 75.1 ± 2.0 HV | - | [31,32,33] |

| Fissurit FX | FFX | Voco, Germany | Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (15–25%), Bis-GMA (5–10%), sodium fluoride (≤2.5%) | Yes | 6.2 ± 0.7 | - | 4.30 ± 1.15 | [15,34,35] |

| Dyract Seal | DS | Dentsply, Germany | Aminopenta, strontium-aluminium, macromonomer, fl uorosilicate glass, DGDMA, aerosil, initiators, inhibitor | Yes | 8.3 ± 0.3 | - | 5.38 ± 1.30 | [15,36] |

| Teethmate F-1 | TF1 | Kuraray, Japan | 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, TEGDMA, 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate, methacryloylfluoride-methyl methacrylate copolymer, hydrophobic aromatic dimethacrylate, dl-camphorquinone, initiators, accelerators, dyes |

Yes | - | 26.7 ± 1.3 HV* | 7.40 ± 1.17 | [13,15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).