Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

14 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast strains and media

2.2. Screening of mutants

2.3. Preparation of genomic DNA, genome sequencing, and determination of mutations

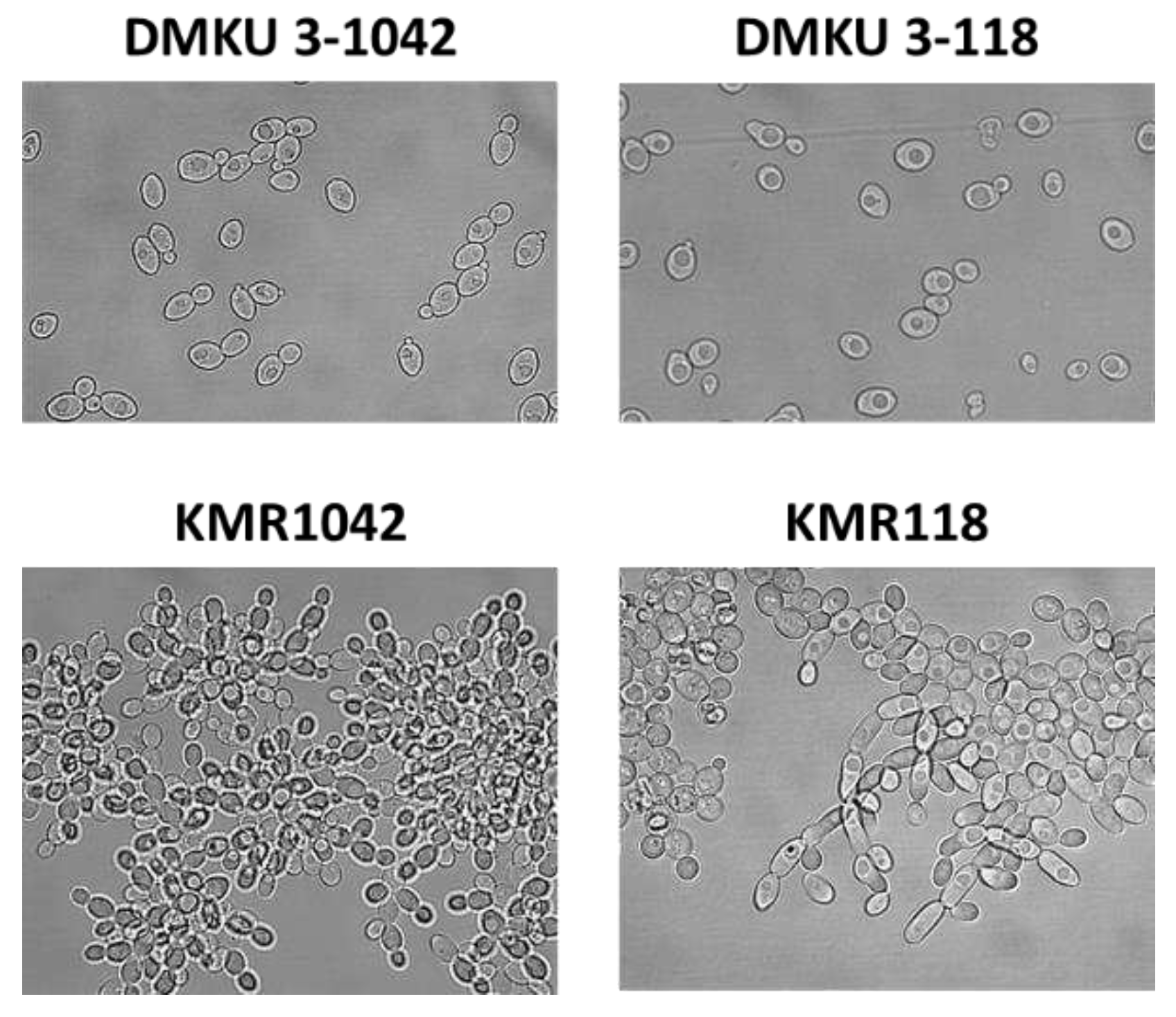

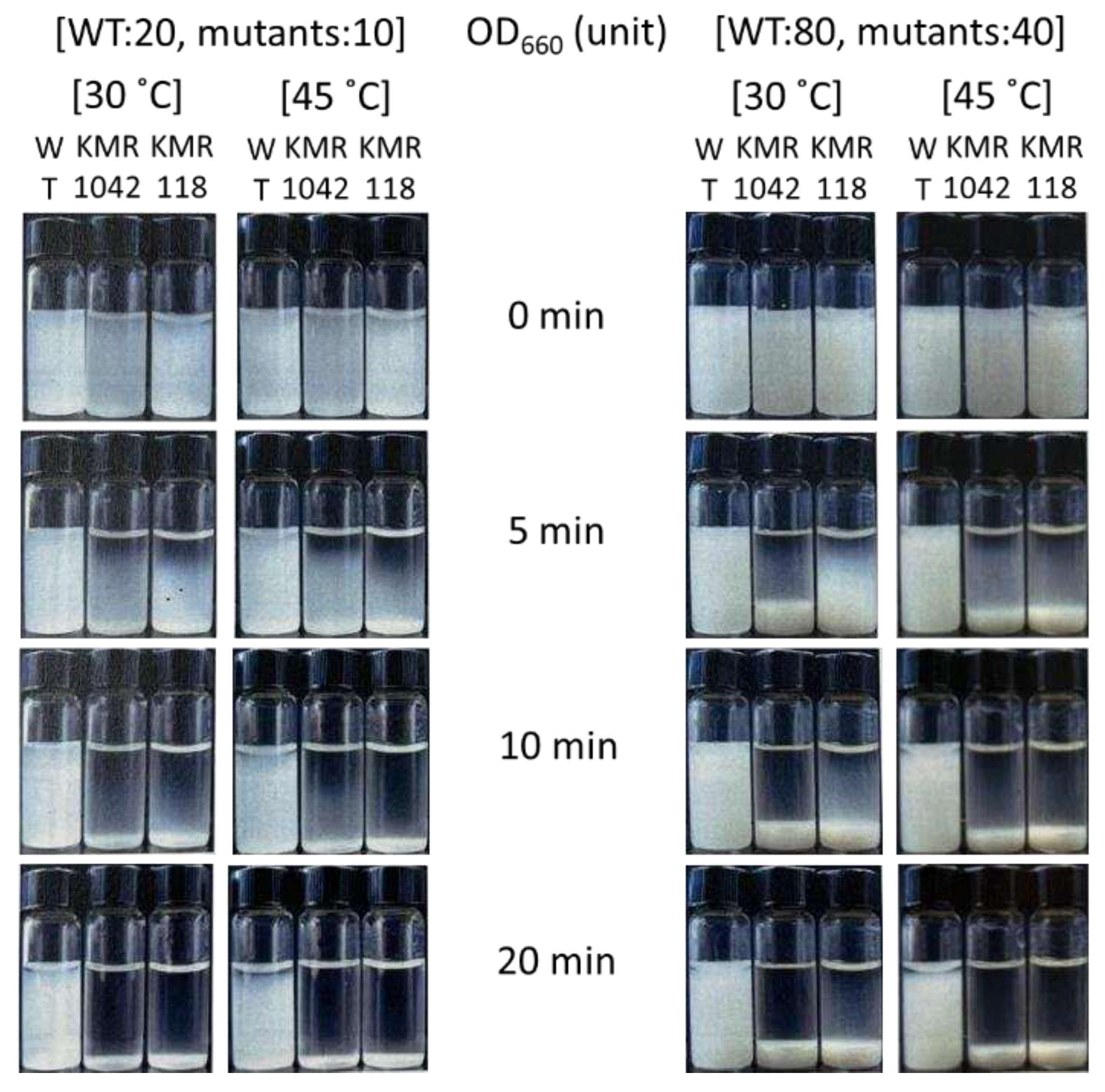

2.4. Cell morphology and sedimenting ability

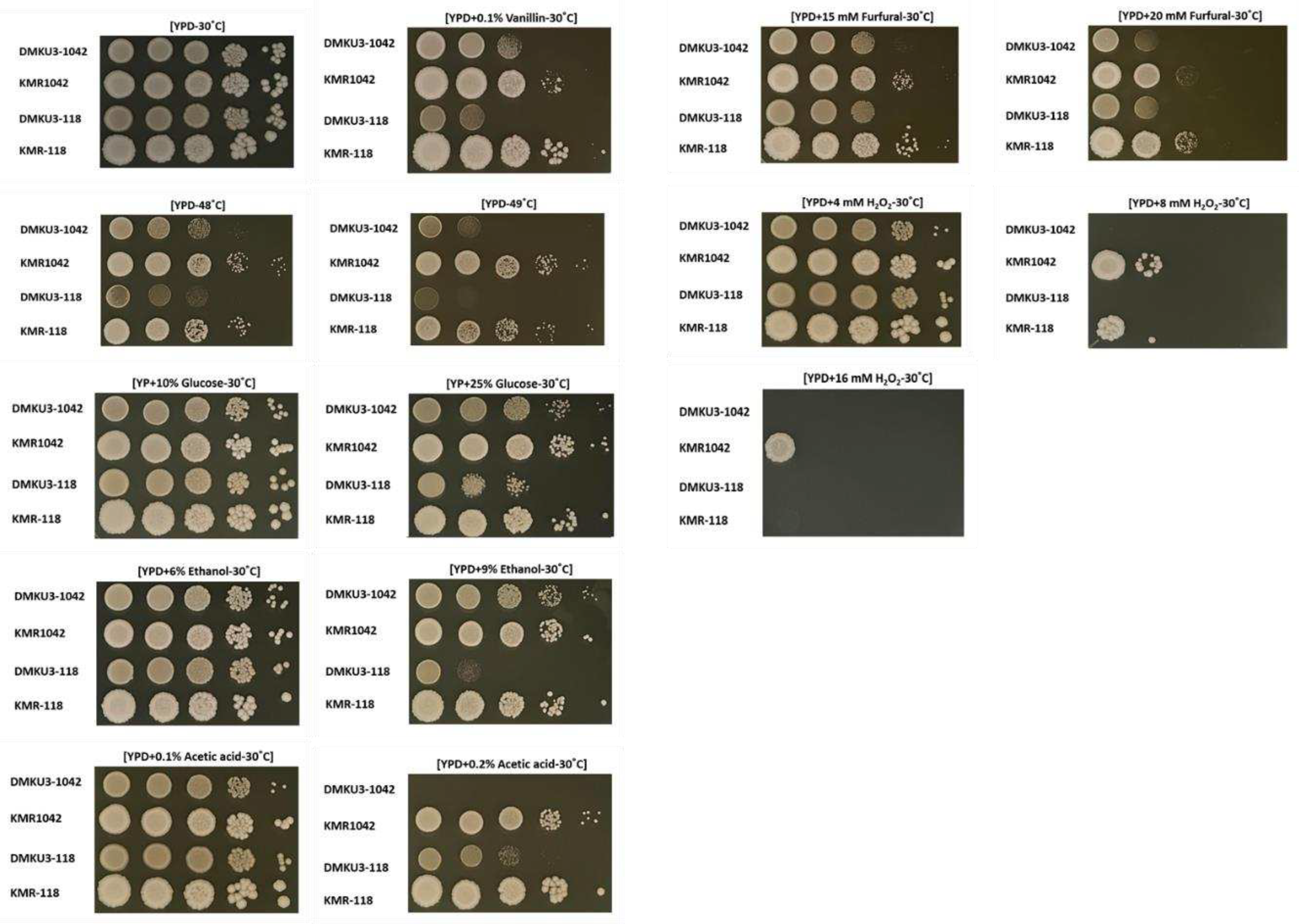

2.5. Analysis of stress tolerance

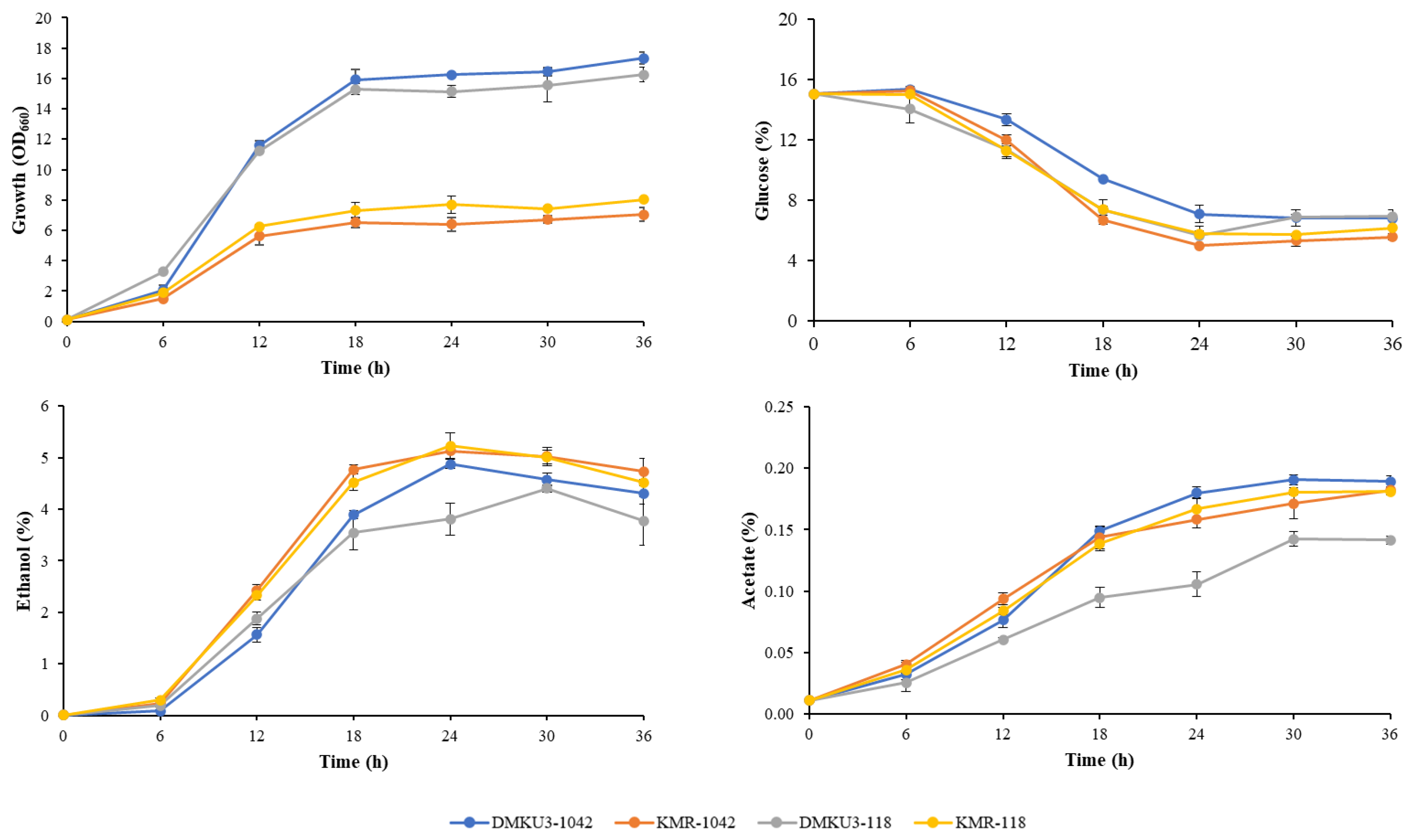

2.6. Analysis of ethanol fermentation ability

2.7. Sequence data deposition

3. Results

3.1. Stress-resistant mutants from K. marxianus strains DMKU 3-1042 and DMKU 3-118

3.2. Sedimenting ability of KMR1042 and KMR118

3.3. Stress tolerance of KMR1042 and KMR118

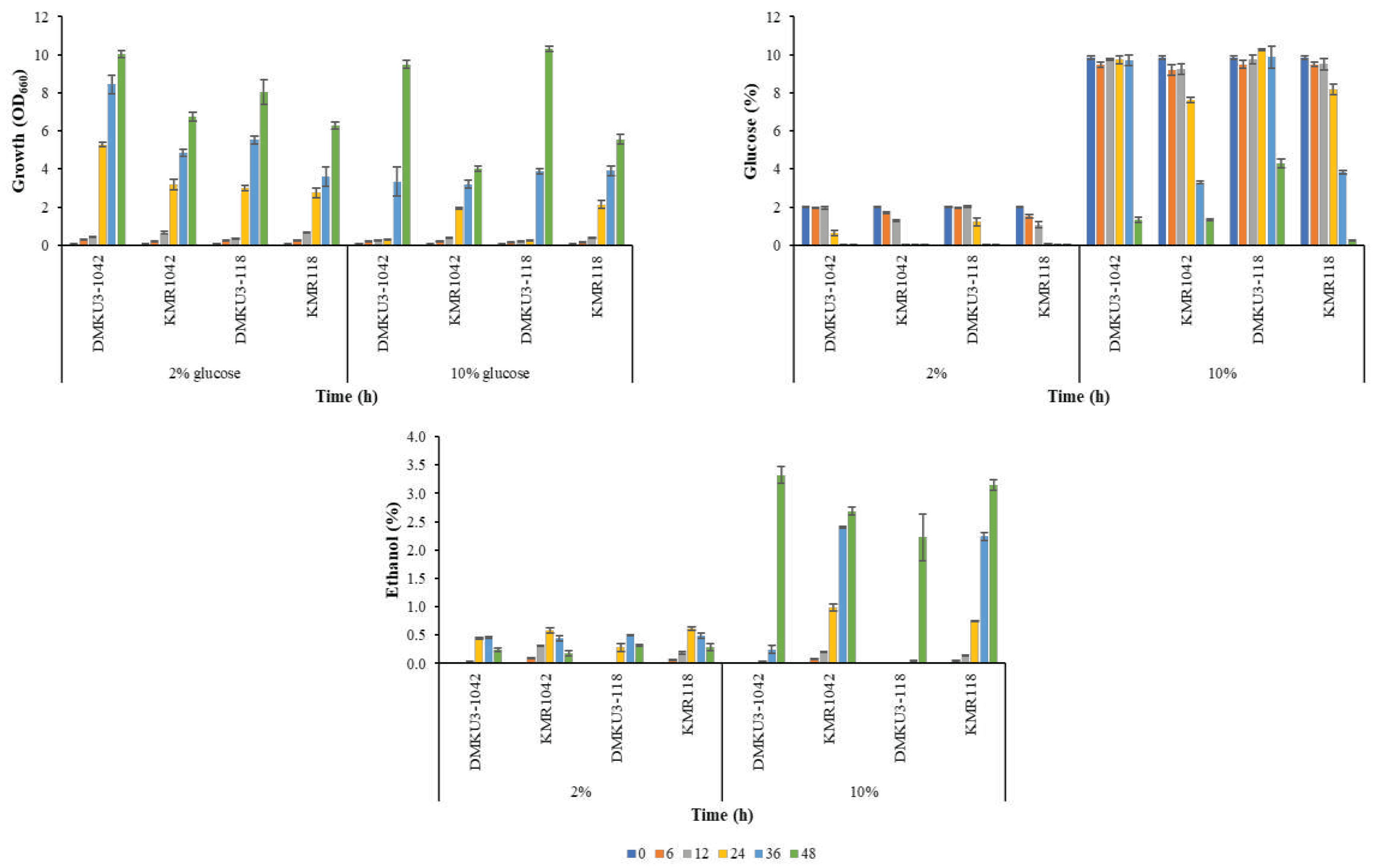

3.4. Ethanol fermentation abilities of KMR1042 and KMR118 under stress conditions

3.5. Analysis of mutation points of KMR1042 and KMR118

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, F.W.; Anderson, W.A.; Moo-Young, M. Ethanol fermentation technologies from sugar and starch feedstocks. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 26, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lertwattanasakul, N.; Rodrussamee, N.; Kumakiri, I.; Pattanakittivorakul, S.; Yamada, M. (2023). Potential of thermo-tolerant microorganisms for production of cellulosic bioethanol. In the Handbook of Biorefinery Research and Technology, Eds.; Bisaria, V.; Springer Dordrecht, 2023; pp. 1–30.

- Limtong, S.; Sringiew, C.; Yongmanitchai, W. Production of fuel ethanol at high temperature from sugar cane juice by a newly isolated Kluyveromyces marxianus. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 3367–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goshima, T.; Tsuji, M.; Inoue, H.; Yano, S.; Hoshino, T.; Matsushika, A. Bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass by a novel Kluyveromyces marxianus strain. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitiyon, S.; Keo-Oudone, C.; Murata, M.; Lertwattanasakul, N.; Limtong, S.; Kosaka, T.; Yamada, M. Efficient conversion of xylose to ethanol by stress-tolerant Kluyveromyces marxianus BUNL-21. Springerplus 2016, 27, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, P.; Beniwal, A.; Kokkiligadda, A.; Vij, S. Evolutionary adaptation of Kluyveromyces marxianus strain for efficient conversion of whey lactose to bioethanol. Process. Biochem. 2017, 62, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, T.; Nakajima, Y.; Ishii, A.; Yamashita, M.; Yoshida, S.; Murata, M.; Kato, K.; Shiromaru, Y.; Kato, S.; Kanasaki, Y.; Yoshikawa, H.; Matsutani, M.; Thanonkeo, P.; Yamada, M. Capacity for survival in global warming: adaptation of mesophiles to the temperature upper limit. PloS ONE 2019, 14, e0215614. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrussamee, N.; Lertwattanasakul, N.; Hirata, K.; Suprayogi; Limtong, S. ; Kosaka, T.; Yamada, M. Growth and ethanol fermentation ability on hexose and pentose sugars and glucose effect under various conditions in thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertwattanasakul, N.; Rodrussamee, N.; Suprayogi; Limtong, S. ; Thanonkeo, P.; Kosaka, T.; Yamada, M. Utilization capability of sucrose, raffinose and inulin and its less-sensitiveness to glucose repression in thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus DMKU 3-1042. AMB Expr. 2011, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertwattanasakul, N.; Suprayogi; Murata, M. ; Rodrussamee, N.; Limtong, S.; Kosaka, T.; Yamada, M. Essentiality of respiratory activity for pentose utilization in thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus DMKU 3-1042. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 103, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurcholis, M.; Murata, M.; Limtong, S.; Kosaka, T.; Yamada, M. MIG1 as a positive regulator for the histidine biosynthesis pathway and as a global regulator in thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.; Bru, S.; Ribeiro, M.PC.; Clotet, J. Live fast, die soon: cell cycle progression and lifespan in yeast cells. Microb. Cell 2015, 2, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarrío, N.; García-Leiro, A.; Cerdán, M.E.; González-Siso, M.I. The role of glutathione reductase in the interplay between oxidative stress response and turnover of cytosolic NADPH in Kluyveromyces lactis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auesukaree, C. Molecular mechanisms of the yeast adaptive response and tolerance to stresses encountered during ethanol fermentation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2017, 124, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jönsson, L.J. ; Alriksson, B.; Nilvebrant, N-O. Bioconversion of lignocellulose: inhibitors and detoxification. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Akuzawa, S.; Nagaoka, J.; Kanekatsu, M.; Kanesaki, Y.; Suzuki, T. Draft genome sequence of Oceanobacillus picturae Heshi-B3, isolated from fermented rice bran in a traditional Japanese seafood dish. Genome Announc. 2016, 4, e01621–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePristo, M.A.; Banks, E.; Poplin, R.; Garimella, K.V.; Maguire, J.R.; Hartl, C.; Philippakis, A.A. , del Angel, G.; Rivas, M.A.; Hanna, M.; McKenna, A.; Fennell, T.J.; Kernytsky, A.M.; Sivachenko, A.Y.; Cibulskis, K.; Gabriel, S.B.; Altshuler, D.; Daly, M.J. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011, 43, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsutani, M.; Matsumoto, N.; Hirakawa, H.; Shiwa, Y.; Yoshikawa, H.; Okamoto-Kainuma, A.; Ishikawa, M.; Kataoka, N.; Yakushi, T.; Matsushita, K. Comparative genomic analysis of closely related Acetobacter pasteurianus strains provides evidence of horizontal gene transfer and reveals factors necessary for thermotolerance. J Bacteriol. 2020, 202, e00553–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, B.R.; Lawrence, S.J.; Leclaire, J.P.; Powell, C.D.; Smart, K.A. Yeast responses to stresses associated with industrial brewery handling. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 31, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puligundla, P.; Smogrovicova, D.; Obulam, V.S.R. , Ko, S. Very high gravity (VHG) ethanolic brewing and fermentation: a research update. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, J.; Jiang, L. Modulation of mitochondrial membrane integrity and ROS formation by high temperature in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 18, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Roberto, I.C. Alternatives for detoxification of diluted-acid lignocellulosic hydrolyzates for use in fermentative processes: a review. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 93, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, S.; Arora, R.; Nandhagopal, N.; Kumar, S. Importance of chemical pretreatment for bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 36, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanakittivorakul, S.; Tsuzuno, T.; Kosaka, T.; Murata, M.; Kanesaki, Y.; Yoshikawa, H.; Limtong, S.; Yamada, M. Evolutionary adaptation by repetitive long-term cultivation with gradual increase in temperature for acquiring multi-stress tolerance and high ethanol productivity in Kluyveromyces marxianus DMKU 3-1042. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisselink, H.W.; Toirkens, M.J.; Wu, Q.; Pronk, J.T.; van Maris, A.J.A. Novel evolutionary engineering approach for accelerated utilization of glucose, xylose, and arabinose mixtures by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyper, M.; Toirkens, M.J.; Diderich, J.A.; Winkler, A.A.; van Dijken, J.P.; Pronk, J.T. Evolutionary engineering of mixed-sugar utilization by a xylose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005, 5, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe-Medina, V.; Almering, M.J.H.; van Maris, A.J.A.; Pronk, J.T. Elimination of glycerol production in anaerobic cultures of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain engineered to use acetic acid as an electron acceptor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppram, R.; Albers, E.; Olsson, L. Evolutionary engineering strategies to enhance tolerance of xylose utilizing recombinant yeast to inhibitors derived from spruce biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2012, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelle, R.M.; Harrison, J.C.; Pronk, J.T.; van Maris, A.J.A. Anaplerotic role for cytosolic malic enzyme in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kok, S.; Nijkamp, J.F.; Oud, B.; Roque, F.C. , de Ridder, D.; Daran J-M., Pronk, J.T.; van Maris, A.J.A. Laboratory evolution of new lactate transporter genes in a jen1 delta mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their identification as ADY2 alleles by whole-genome resequencing and transcriptome analysis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012, 12, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adamo, G.M.; Brocca, S.; Passolunghi, S.; Salvato, B.; Lotti, M. Laboratory evolution of copper tolerant yeast strains. Microb. Cell. Fact. 2012, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doolin, M.T.; Johnson, A.L.; Johnston, L.H.; Butler, G. Overlapping and distinct roles of the duplicated transcription factors Ace2p and Swi5p. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 40, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, I.; Barnett, J.; Hannett, N.; Harbison, C.T.; Rinaldi, N.J.; Volkert, T.L.; Wyrick, J.J.; Zeitlinger, J.; Gifford, D.K.; Jaakkola, T.S.; Young, R.A. Serial regulation of transcriptional regulators in the yeast cell cycle. Cell. 2001, 106, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colman-Lerner, A.; Chin, T.E.; Brent, R. Yeast Cbk1 and Mob2 activate daughter-specific genetic programs to induce asymmetric cell fates. Cell. 2001, 107, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, E.L.; Kurischko, C.; Zhang, C.; Shokat, K.; Drubin, D.G.; Luca, F.C. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mob2p-Cbk1p kinase complex promotes polarized growth and acts with the mitotic exit network to facilitate daughter cell-specific localization of Ace2p transcription factor. J. Cell. Biol. 2002, 158, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.; Butler, G. Ace2p, a regulator of Cts1 (chitinase) expression, affects pseudohyphal production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 1998, 34, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Conallain, C.; Doolin, M.T.; Taggart, C.; Thornton, F.; Butler, G. Regulated nuclear localization of the yeast transcription factor Ace2p controls expression of chitinase (CTS1) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1999, 262, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrmann, P.R.; Butler, G.; Tamai, K.; Dorland, S.; Greene, J.R.; Thiele, D.J.; Stillman, D.J. Parallel pathways of gene regulation: homologous regulators SWI5 and ACE2 differentially control transcription of HO and chitinase. Genes. Dev. 1992, 6, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrmann, P.R.; Voth, W.P.; Stillman, D.J. Role of negative regulation in promoter specificity of the homologous transcriptional activators Ace2p and Swi5p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996, 16, 1746–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, H.J.; Yu, Y.; Stillman, D.J. Distinct regions of the Swi5 and Ace2 transcription factors are required for specific gene activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 21029–21036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dujon, B.; Sherman, D.; Fischer, G.; Durrens, P.; Casaregola, S.; Lafontaine, I.; De Montigny, J.; Marck, C.; Neuveglise, C.; Talla, E.; Goffard, N.; Frangeul, L.; Aigle, M.; Anthouard, V.; Babour, A.; Barbe, V.; Barnay, S.; Blanchin, S.; Beckerich, J.M.; Beyne, E.; Bleykasten, C.; Boisrame, A.; Boyer, J.; Cattolico, L.; Confanioleri, F.; De Daruvar, A.; Despons, L.; Fabre, E.; Fairhead, C.; Ferry-Dumazet, H.; Groppi, A.; Hantraye, F.; Hennequin, C.; Jauniaux, N.; Joyet, P.; Kachouri, R.; Kerrest, A.; Koszul, R.; Lemaire, M.; Lesur, I.; Ma, L. , Muller, H.; Nicaud, J.M., Nikolski, M., Oztas, S., Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, O.; Pellenz, S., Potier, S.; Richard, G.F.; Straub, M.L.; Suleau, A.; Swennen, D.; Tekaia, F.; Wesolowski-Louvel, M.; Westhof, E.; Wirth, B.; Zeniou-Meyer, M.; Zivanovic, I.; Bolotin-Fukuhara, M.; Thierry, A.; Bouchier, C.; Caudron, B.; Scarpelli, C.; Gaillardin, C.; Weissenbach, J.; Wincker, P.; Souciet, J.L. Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature 2004, 430, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.T.; MacCallum, D.M. , Clancy, S.D.; Odds, F.C.; Brown, A.J.P.; Butler, G. The Candida albicans CaACE2 gene affects morphogenesis, adherence and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 969–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamran, M.; Calcagno, A.M.; Findon, H.; Bignell, E.; Jones, M.D.; Warn, P.; Hopkins, P.; Denning, D.W.; Butler,G. ; Rogers, T.; Muhlschlegel, F.A.; Haynes, K. Inactivation of transcription factor gene ACE2 in the fungal pathogen Candida glabrata results in hypervirulence. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, D.; Findon, H.; Yin, Z.K.; Walker, J.; Selway, L.; Cash, P.; Dujon, B.A.; Hennequin, C.; Brown, A.J.P.; Haynes, K. Proteomic changes associated with inactivation of the Candida glabrata ACE2 virulence-moderating gene. Proteomics 2005, 5, 1838–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, D.M.; Findon, H.; Kenny, C.C.; Butler, G.; Haynes, K.; Odds, F.C. Different consequences of ACE2 and SWI5 gene disruptions for virulence of pathogenic and nonpathogenic yeasts. Infect Immun. 2006, 74, 5244–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussereau, F.; Casaregola, S.; Lafay, J.F.; Bolotin-Fukuhara, M. The Kluyveromyces lactis repertoire of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Yeast Research 2006, 6, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhern, S.M.; Logue, M.E.; Butler, G. Candida albicans transcription factor Ace2 regulates metabolism and Is Required for filamentation in hypoxic conditions. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 2001–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasch, A.P.; Spellman, P.T.; Kao, C.M.; Carmel-Harel, O.; Eisen, M.B.; Storz, G.; Botstein, D.; Brown, P.O. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000, 11, 4241–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Toone, W.M.; Mata, J.; Lyne, R.; Burns, G.; Kivinen, K.; Brazma, A.; Jones, N.; Bähler, J. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003, 14, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjalbert, B.; Nantel, A.; Whiteway, M. Stress-induced gene expression in Candida albicans: absence of a general stress response. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003, 14, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasch, A.P. Comparative genomics of the environmental stress response in ascomycete fungi. Yeast. 2007, 24, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eardley, J.; Timson, D.J. Yeast cellular stress: impacts on bioethanol production. Fermentation 2020, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Święciło, A. Cross-stress resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast—new insight into an old phenomenon. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2016, 21, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasch, A.P. The environmental stress response: a common yeast response to diverse environmental stresses. In Yeast Stress Responses. Eds.; Hohmann, S., Mager, W.H., Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, New York. 2003; Volume 1, pp. 11–70.

| KMR1042 | |||||||

| locus_tag | gene | product | reference genome (NCBI ref seq acc. no.) | position | REF | ALT | AA sub |

| KLMA_10406 | TVP38 | Golgi apparatus membrane protein TVP38 | AP012213.1 | 858831 | C | T | Val158Val |

| KLMA_50490 | SWI5 | metallothionein expression activator | AP012217.1 | 1055034 | TACCACCATTA | T | Asn320fs |

| KLMA_50562 | UPS2 | protein MSF1 | AP012217.1 | 1204779 | C | T | Asp37Asn |

| KLMA_80154 | - | putative zinc metalloproteinase YIL108W | AP012220.1 | 339946 | C | CG | Ala660fs |

| KMR118 | |||||||

| locus_tag | gene | product | reference genome (NCBI refseq acc. no.) | position | REF | ALT | |

| KLMA_10572 | SRV2 | adenylyl cyclase-associated protein | AP012213.1 | 1202978 | G | A | Pro65Pro |

| KLMA_10608 | - | hypothetical protein | AP012213.1 | 1272508 | G | T | Thr373Thr |

| KLMA_20191 | HPR1 | THO complex subunit HPR1 | AP012214.1 | 431928 | C | A | Ile202Ile |

| KLMA_30667 | HKR1 | herpes_gp2 | AP012215.1 | 1429635 | C | G | Pro158Ala |

| KLMA_30667 | HKR1 | herpes_gp2 | AP012215.1 | 1429636 | C | A | Pro158His |

| KLMA_30667 | HKR1 | herpes_gp2 | AP012215.1 | 1429661 | A | AC | Asp168fs |

| KLMA_50490 | SWI5 | metallothionein expression activator | AP012217.1 | 1053571 | G | T | Tyr810stop |

| KLMA_60329 | IXR1 | HMGB-UBF_HMG-box containing protein | AP012218.1 | 691365 | A | AGCTTGG | Ala173_Gln174ins |

| KLMA_70080 | - | conserved hypothetical protein | AP012219.1 | 159037 | G | A | Ala417Thr |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).