Submitted:

25 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

- Oligo design and vector construction

- Cell Culture

- Virus Production

- Determination of Infection Conditions

- Single Cell Clone Selection, Genomic DNA Preparation and Sequencing

- DNA and Protein Sequence Analysis

- Immunoblot Analysis

Transcriptome Analysis

- RNA-seq

- DEG (differentially expressed gene) Analysis

- Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA)

- Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and STRING analysis

- Statistical analysis

Results

- Design of sgRNAs Targeted to the TBCK Gene

- TBCK knockout vector construction

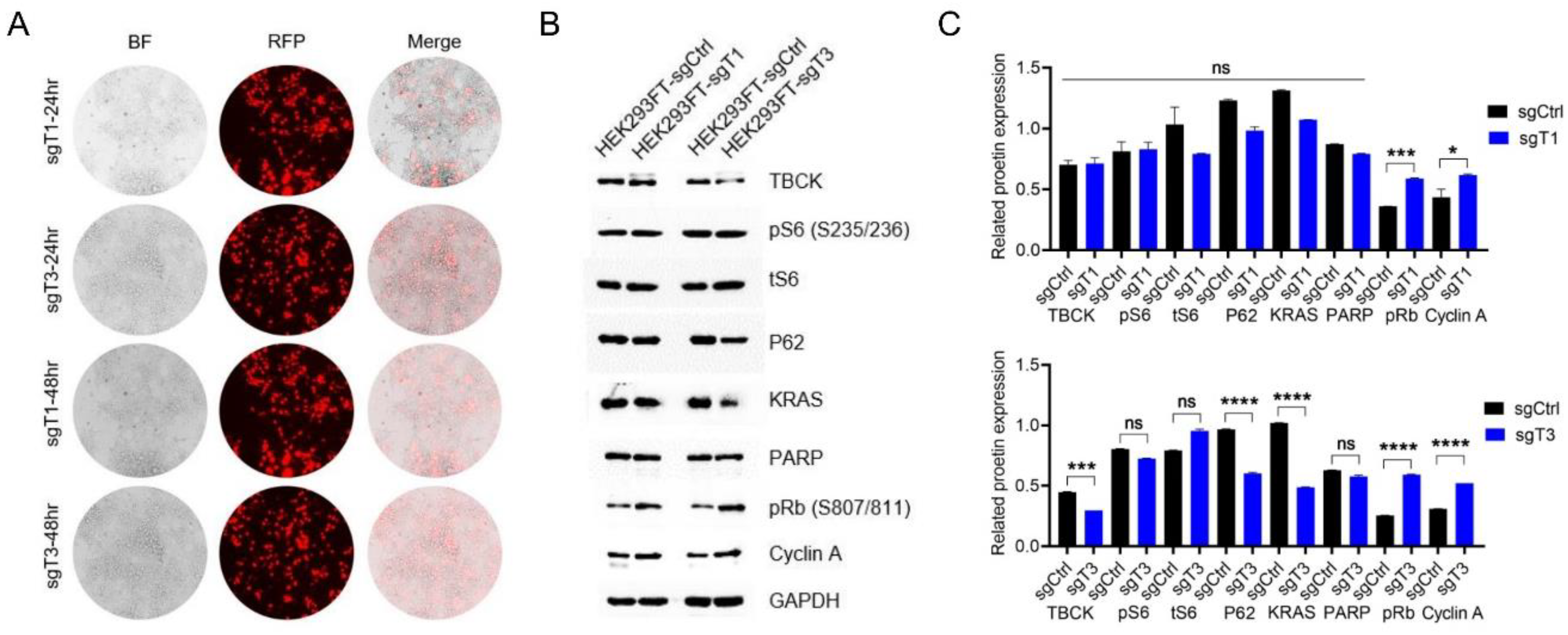

- Knockout Efficiency of TBCK in HEK293FT Cells

- Lentivirus Preparation and Target Cell Infection

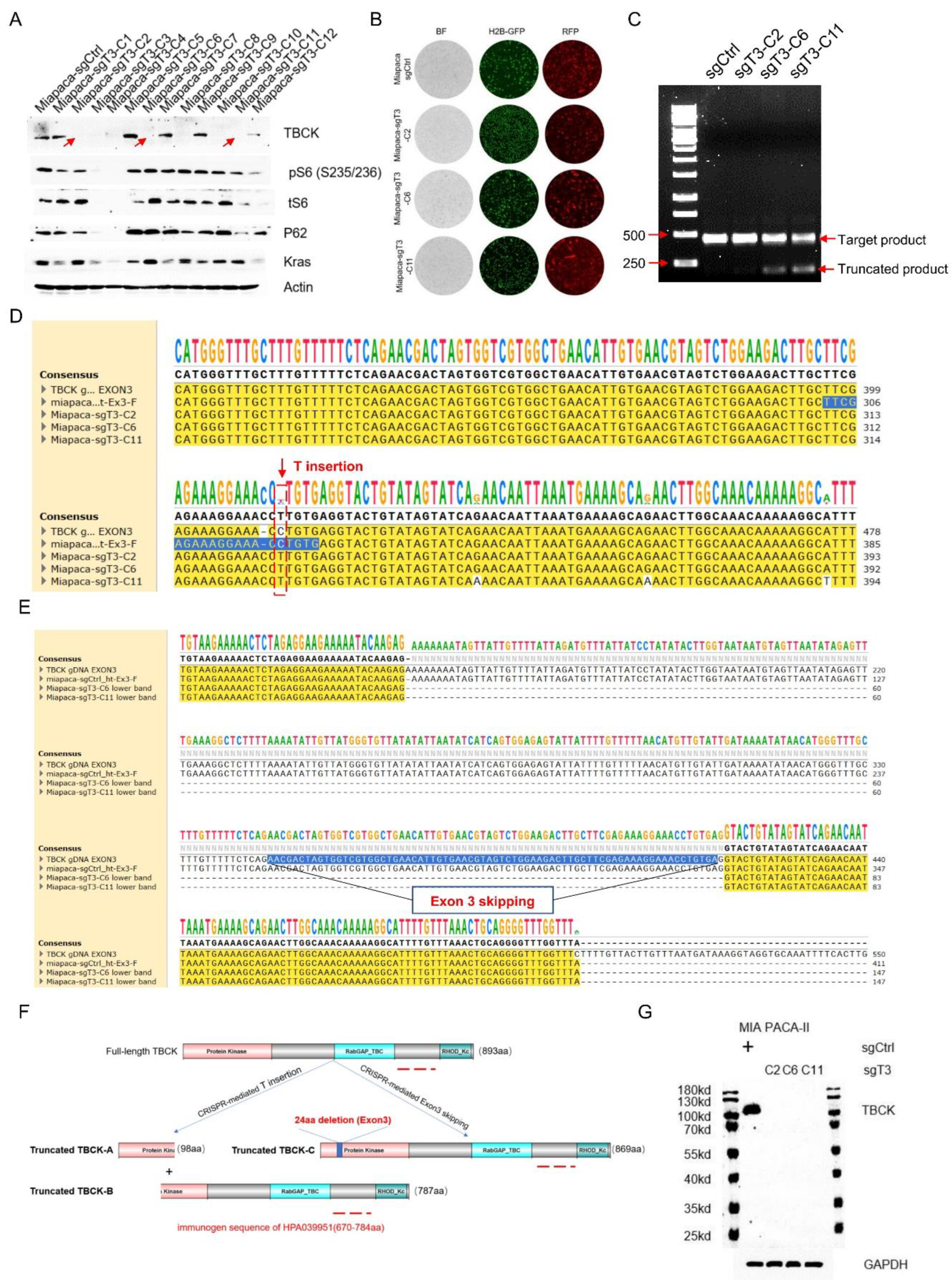

- Single Cell Clone Selection and Validation in MIA PaCa-2 Cell Model

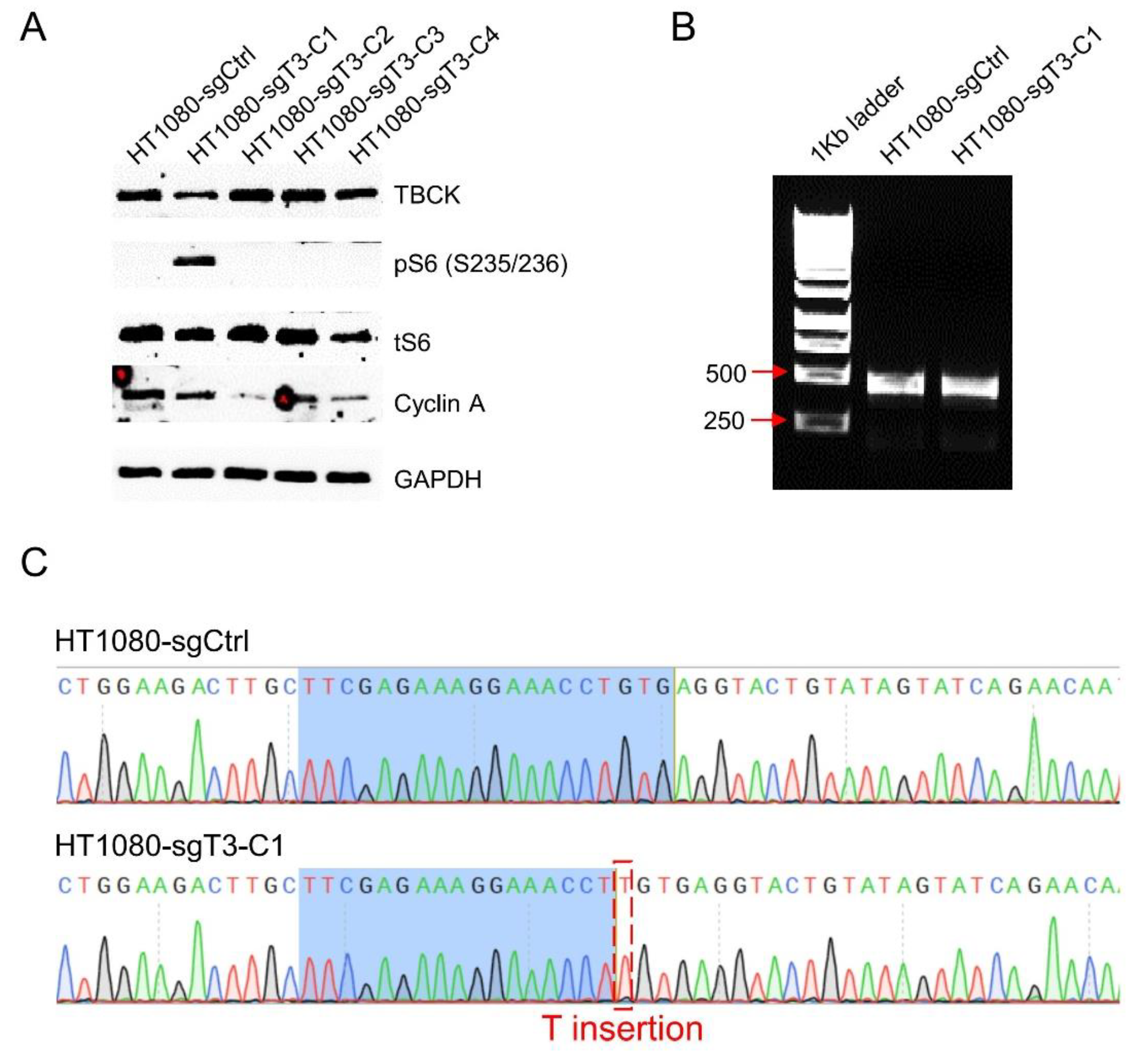

- The Knockout Vector Can be Applied in Fibrosarcoma HT1080 Cell Model

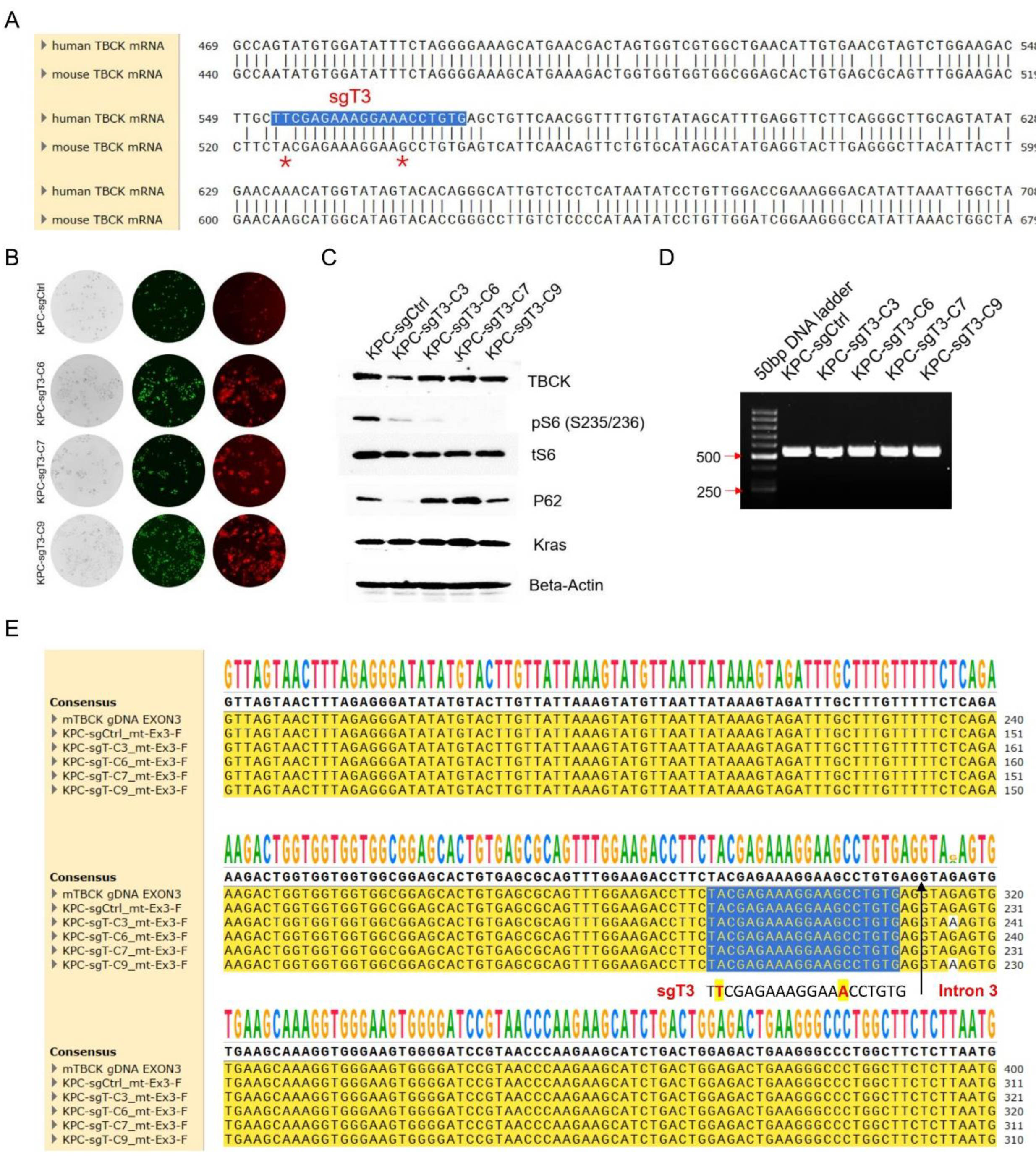

- The Human Specific sgRNA against TBCK Showed Little Effects on Mouse Cells

- RNA-Seq Application for TBCK Knockout Single Clone in PDAC Model

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Authors Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Consent for Publication

Abbreviations

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| Cas9 | CRISPR-associated 9 |

| TBCK | TBC1 domain containing kinase |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| sgRNA | Single guide RNA |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| sgCtrl | Single guide control RNA |

| sgT1 | Single guide TBCK RNA (oligo 1) |

| sgT3 | Single guide TBCK RNA (oligo 3) |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analyses |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RFP | Red Fluorescent Protein |

| GFP | Green Fluorescent Protein |

| pRB | Phosphorylated Rb1 |

| gDNA | Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid |

| KPC3 | C57/BL6 genetic background mouse cell line with Kras and TP53 mutations |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| Figure S | Supplementary Figure |

| Table S | Supplementary Table |

References

- Wu, J.; Lu, G. Multiple functions of TBCK protein in neurodevelopment disorders and tumors (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2020, 21, 12278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.X.; Caputo, V.; Phelps, I.G.; Stella, L.; Worgan, L.; Dempsey, J.C.; Nguyen, A.; Leuzzi, V.; Webster, R.; Pizzuti, A.; et al. Recessive Inactivating Mutations in TBCK, Encoding a Rab GTPase-Activating Protein, Cause Severe Infantile Syndromic Encephalopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhoj, E.J.; Li, D.; Harr, M.; Edvardson, S.; Elpeleg, O.; Chisholm, E.; Juusola, J.; Douglas, G.; Sacoto, M.J.G.; Siquier-Pernet, K.; et al. Mutations in TBCK, Encoding TBC1-Domain-Containing Kinase, Lead to a Recognizable Syndrome of Intellectual Disability and Hypotonia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-González, X.R.; Tintos-Hernández, J.A.; Keller, K.; Li, X.; Foley, A.R.; Bharucha-Goebel, D.X.; Kessler, S.K.; Yum, S.W.; Crino, P.B.; He, M.; et al. Homozygous boricua TBCK mutation causes neurodegeneration and aberrant autophagy. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 83, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Tintos-Hernández, J.; Santana, A.; Keller, K.N.; Ortiz-González, X.R. Lysosomal dysfunction impairs mitochondrial quality control and is associated with neurodegeneration in TBCK encephaloneuronopathy. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.; Diaz-Rosado, A.; Varella-Branco, E.; Ramos, I.; Black, A.; Angireddy, R.; Park, J.; Murali, S.; Yoon, A.; Ciesielski, B.; et al. Heterozygous variants in TBCK cause a mild neurologic syndrome in humans and mice. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2023, 191, 2508–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komurov, K.; Padron, D.; Cheng, T.; Roth, M.; Rosenblatt, K.P.; White, M.A. Comprehensive Mapping of the Human Kinome to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 21134–21142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhou, T. TBCK Influences Cell Proliferation, Cell Size and mTOR Signaling Pathway. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, D.; Zhu, G.; Wang, L.; He, D.; Lu, G.; Zeng, C. A Long Type of TBCK Is a Novel Cytoplasmic and Mitotic Apparatus-Associated Protein Likely Suppressing Cell Proliferation. J. Genet. Genom. 2014, 41, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, I.; Gorunova, L.; Viset, T.; Heim, S. Gene fusions AHRR-NCOA2, NCOA2-ETV4, ETV4-AHRR, P4HA2-TBCK, and TBCK-P4HA2 resulting from the translocations t(5;8;17)(p15;q13;q21) and t(4;5)(q24;q31) in a soft tissue angiofibroma. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-A.; Jang, J.-H.; Sung, E.-G.; Song, I.-H.; Kim, J.-Y.; Lee, T.-J. MiR-1208 Increases the Sensitivity to Cisplatin by Targeting TBCK in Renal Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Xi, L.; Yu, R.; Xu, H.; Wu, M.; Huang, H. Differential mutation detection capability through capture-based targeted sequencing in plasma samples in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 596789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lu, G.; Wu, J.; Yang, H.; Yu, Z.; Mu, S.; Zhang, H. Application of fusion PCR to the amplification of full-length ORF sequences of different splicing variants of from HeLa cells. Acta Biochim. et Biophys. Sin. 2017, 49, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.W.; Jorgensen, E.M. ApE, A Plasmid Editor: A Freely Available DNA Manipulation and Visualization Program. Front. Bioinform. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Wen, L.; Gao, X.; Jin, C.; Xue, Y.; Yao, X. DOG 1.0: Illustrator of protein domain structures. Cell Res. 2009, 19, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Wu, H.; Wu, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; Yu, P.; et al. Constructing a novel mitochondrial-related gene signature for evaluating the tumor immune microenvironment and predicting survival in stomach adenocarcinoma. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, W.; Chang, J.; Wu, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Ou, Z.; Tang, T.; Li, L.; Liu, M.; et al. Identification and Validation of a Mitochondria Calcium Uptake-Related Gene Signature for Predicting Prognosis in COAD. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Kou, Y.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Meirelles, G.V.; Clark, N.R.; Ma’Ayan, A. Enrichr: Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, M.V.; Jones, M.R.; Rouillard, A.D.; Fernandez, N.F.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Koplev, S.; Jenkins, S.L.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Lachmann, A.; et al. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W90–W97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Bailey, A.; Kuleshov, M.V.; Clarke, D.J.B.; Evangelista, J.E.; Jenkins, S.L.; Lachmann, A.; Wojciechowicz, M.L.; Kropiwnicki, E.; Jagodnik, K.M.; et al. Gene Set Knowledge Discovery with Enrichr. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberzon, A.; Birger, C.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Ghandi, M.; Mesirov, J.P.; Tamayo, P. The Molecular Signatures Database Hallmark Gene Set Collection. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, V.K.; Lindgren, C.M.; Eriksson, K.-F.; Subramanian, A.; Sihag, S.; Lehar, J.; Puigserver, P.; Carlsson, E.; Ridderstråle, M.; Laurila, E.; et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003, 34, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Wyder, S.; Forslund, K.; Heller, D.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Santos, A.; Tsafou, K.P.; et al. STRING v10: Protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D447–D452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, J.; Cheng, M.; Liao, X.; Peng, S. Review of CRISPR/Cas9 sgRNA Design Tools. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2018, 10, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattanayak, V.; Lin, S.; Guilinger, J.P.; Ma, E.; Doudna, J.A.; Liu, D.R. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doench, J.G.; Fusi, N.; Sullender, M.; Hegde, M.; Vaimberg, E.W.; Donovan, K.F.; Smith, I.; Tothova, Z.; Wilen, C.; Orchard, R.; et al. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doench, J.G.; Hartenian, E.; Graham, D.B.; Tothova, Z.; Hegde, M.; Smith, I.; Sullender, M.; Ebert, B.L.; Xavier, R.J.; Root, D.E. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjana, N.E.; Shalem, O.; Zhang, F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmgaard, A.; Askou, A.L.; Benckendorff, J.N.E.; Thomsen, E.A.; Cai, Y.; Bek, T.; Mikkelsen, J.G.; Corydon, T.J. In Vivo Knockout of the Vegfa Gene by Lentiviral Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 in Mouse Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cells. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2017, 9, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Boyle, B.; Shrestha, S.; Kochut, K.; Eyers, P.A.; Kannan, N. Computational tools and resources for pseudokinase research. 2022, 667, 403–426. [CrossRef]

- Metz, K.S.; Deoudes, E.M.; Berginski, M.E.; Jimenez-Ruiz, I.; Aksoy, B.A.; Hammerbacher, J.; Gomez, S.M.; Phanstiel, D.H. Coral: Clear and Customizable Visualization of Human Kinome Data. Cell Syst. 2018, 7, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrot, V.; Vazquez-Prado, J.; Gutkind, J.S. Plexin B regulates Rho through the guanine nucleotide exchange factors leukemia-associated Rho GEF (LARG) and PDZ-RhoGEF. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 43115–43120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrotto, P.; Corso, S.; Gamberini, S.; Comoglio, P.M.; Giordano, S. Interplay between scatter factor receptors and B plexins controls invasive growth. Oncogene 2004, 23, 5131–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumathipala, D.; Strømme, P.; Gilissen, C.; Corominas, J.; Frengen, E.; Misceo, D. TBCK Encephaloneuropathy With Abnormal Lysosomal Storage: Use of a Structural Variant Bioinformatics Pipeline on Whole-Genome Sequencing Data Unravels a 20-Year-Old Clinical Mystery. Pediatr. Neurol. 2019, 96, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, P.; Yang, L.; Esvelt, K.M.; Aach, J.; Guell, M.; DiCarlo, J.E.; Norville, J.E.; Church, G.M. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science 2013, 339, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; et al. Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; East, A.; Cheng, A.; Lin, S.; Ma, E.; Doudna, J. RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. eLife 2013, 2, e00471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; A Foden, J.; Khayter, C.; Maeder, M.L.; Reyon, D.; Joung, J.K.; Sander, J.D. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veres, A.; Gosis, B.S.; Ding, Q.; Collins, R.; Ragavendran, A.; Brand, H.; Erdin, S.; Cowan, C.A.; Talkowski, M.E.; Musunuru, K. Low Incidence of Off-Target Mutations in Individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN Targeted Human Stem Cell Clones Detected by Whole-Genome Sequencing. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, F.A.; Hsu, P.D.; Lin, C.-Y.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Konermann, S.; Trevino, A.E.; Scott, D.A.; Inoue, A.; Matoba, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Double Nicking by RNA-Guided CRISPR Cas9 for Enhanced Genome Editing Specificity. Cell 2013, 154, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilinger, J.P.; Thompson, D.B.; Liu, D.R. Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.D.; Scott, D.A.; Weinstein, J.A.; Ran, F.A.; Konermann, S.; Agarwala, V.; Li, Y.; Fine, E.J.; Wu, X.; Shalem, O.; et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodkin, A.L.; Matthes, D.J.; Goodman, C.S. The semaphorin genes encode a family of transmembrane and secreted growth cone guidance molecules. Cell 1993, 75, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Zhu, L. Semaphorins and their receptors: From axonal guidance to atherosclerosis. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, G.M.; Corino, A.; Berzero, G.; Kolling, S.; Filippi, A.R.; Benvenuti, S. Brain metastases from lung cancer: Is MET an actionable target? Cancers 2019, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, W.; Wang, Z.; Zöller, M. Ping-Pong—Tumor and Host in Pancreatic Cancer Progression. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. Neuropilin is a receptor for the axonal chemorepellent Semaphorin III. Cell 1997, 90, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soker, S.; Takashima, S.; Miao, H.Q.; Neufeld, G.; Klagsbrun, M. Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell 1998, 92, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.L.; Bielenberg, D.R.; Gechtman, Z.E.; Miao, H.-Q.; Takashima, S.; Soker, S.; Klagsbrun, M. Identification of a natural soluble neuropilin-1 that binds vascular endothelial growth factor: In vivo expression and antitumor activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 2573–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment | Gene | Forward primer, 5' → 3′ | Reverse primer, 5' → 3′ | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sgCtrl | Control | CACCGACGGAGGCTAAGCGTCGCAA | AAACTTGCGACGCTTAGCCTCCGTC | NA |

| sgT1 | hTBCK | CACCGCATAACGACAATGTCACAG | AAACCTGTGACATTGTCGTTATGC | NM_001163435.3 |

| sgT3 | hTBCK | CACCGTTCGAGAAAGGAAACCTGTG | AAACCACAGGTTTCCTTTCTCGAAC | NM_001163435.3 |

| RT-PCR | U6 | GAGGGCCTATTTCCCATGATT | NA | |

| hTBCK | GTGTGTCAGAAGAAGGGTGAGT | AAACCAAACCCCTGCAGTTTA | NG_034057.3 | |

| mTBCK | GGTGGATGGGGTGCTTACAT | CTCCGGGCTAGGGGAATAAG | NC_000069.7 |

| Source | gene_id | UID | seq | PAM | Exon Number | On-Target Efficacy Score | Rank for sgTBCK via online tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| human_geckov2_library_a | TBCK | HGLibA_48598 | TGAACATTGTGAACGTAGTC | TGG | 3 | 0.4328 | 182 |

| TBCK | HGLibA_48599 | CTCCCATTTCAGCGTCCTTC | GGG | 2 | 0.2272 | 258 | |

| TBCK | HGLibA_48600 | AGCCGAGGCAAAGAAGGTAA | AGG | 2 | 0.5571 | 86 | |

| human_geckov2_library_b | TBCK | HGLibB_48539 | TTCGAGAAAGGAAACCTGTG | AGG | 3 | 0.7099 | 8 |

| TBCK | HGLibB_48540 | AAGAAAATTATTTCAGAGCT | TGG | 7 | 0.3958 | 201 | |

| TBCK | HGLibB_48541 | TTGCTTCCACAAACATCATG | TGG | 2 | 0.6266 | 36 | |

| Online tool sgRNA designer | TBCK | NA | GCATAACGACAATGTCACAG | TGG | 12 | 0.7724 | 3 |

| Cell line name | Species | Tumor Type | Genetic information | TBCK expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiaPaca-2 | Homo Sapiens | PDAC | Kras (G12C); c-Myc (WT); TP53(R248W); RB1(WT) | High |

| HT1080 | Homo Sapiens | Fibrosarcoma | Kras (WT); c-Myc (WT); TP53(WT); RB1(WT) | High |

| KPC3 mouse cell line | Mus musculus | Mouse pancreatic neoplasm | Kras (G12D); c-Myc (WT); TP53(R270H); RB1(WT) | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).