Submitted:

09 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Phytocanabinoids on Inflamation in Murine Macrophages and EGC

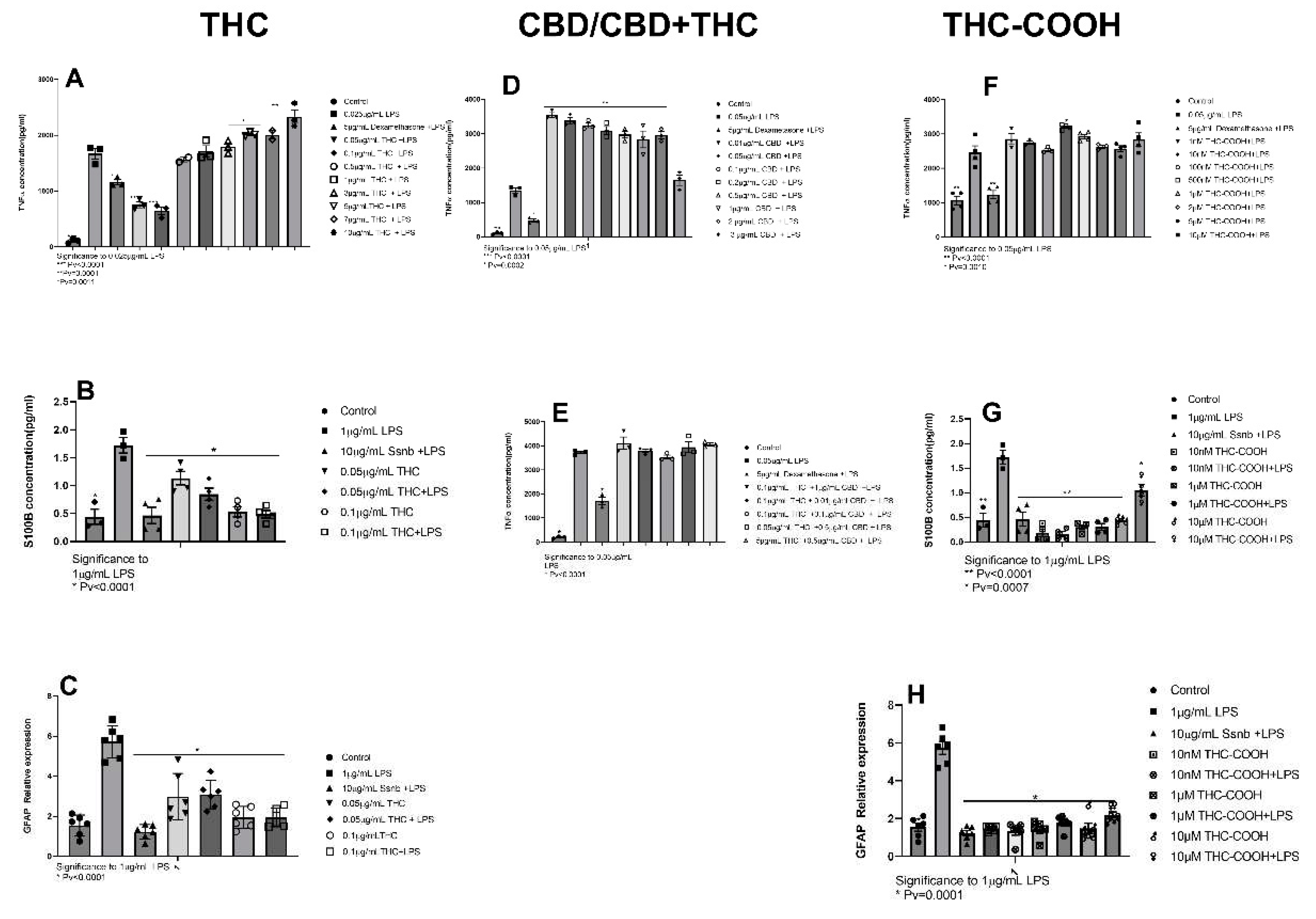

2.1.1. THC

2.1.2. CBD

2.1.3. THC-COOH

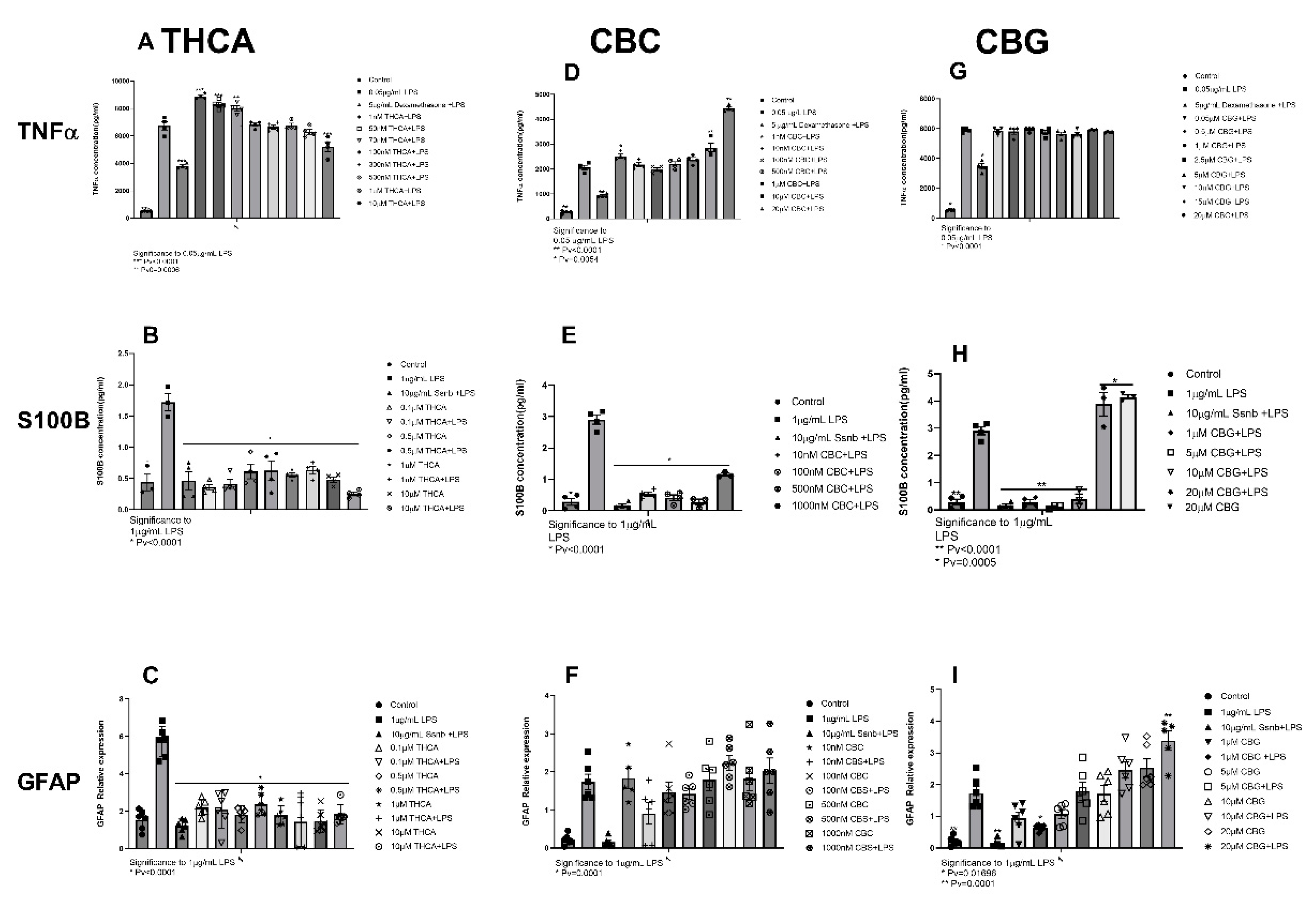

2.1.4. THCA

2.1.5. CBC and CBG

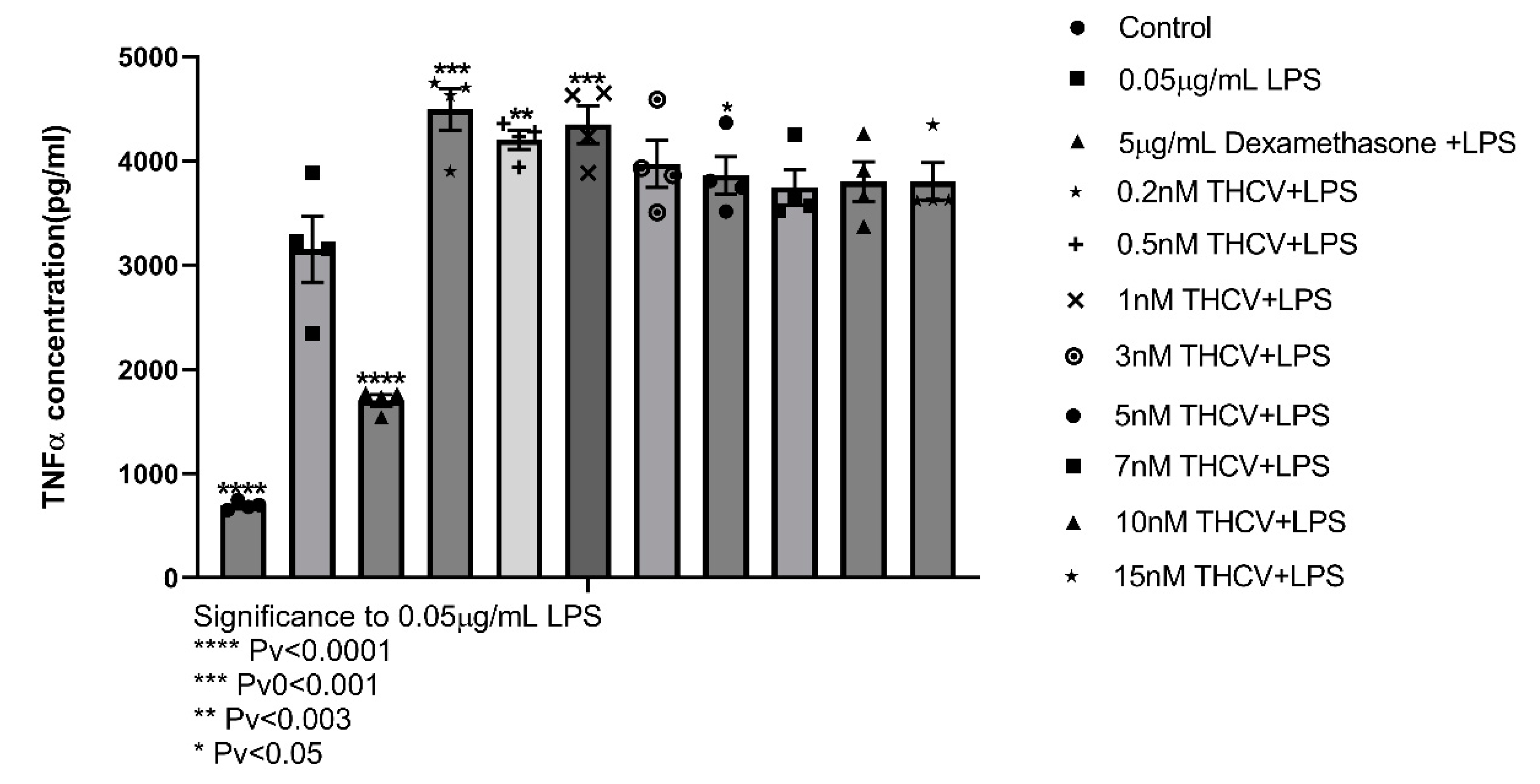

2.1.5. THCV

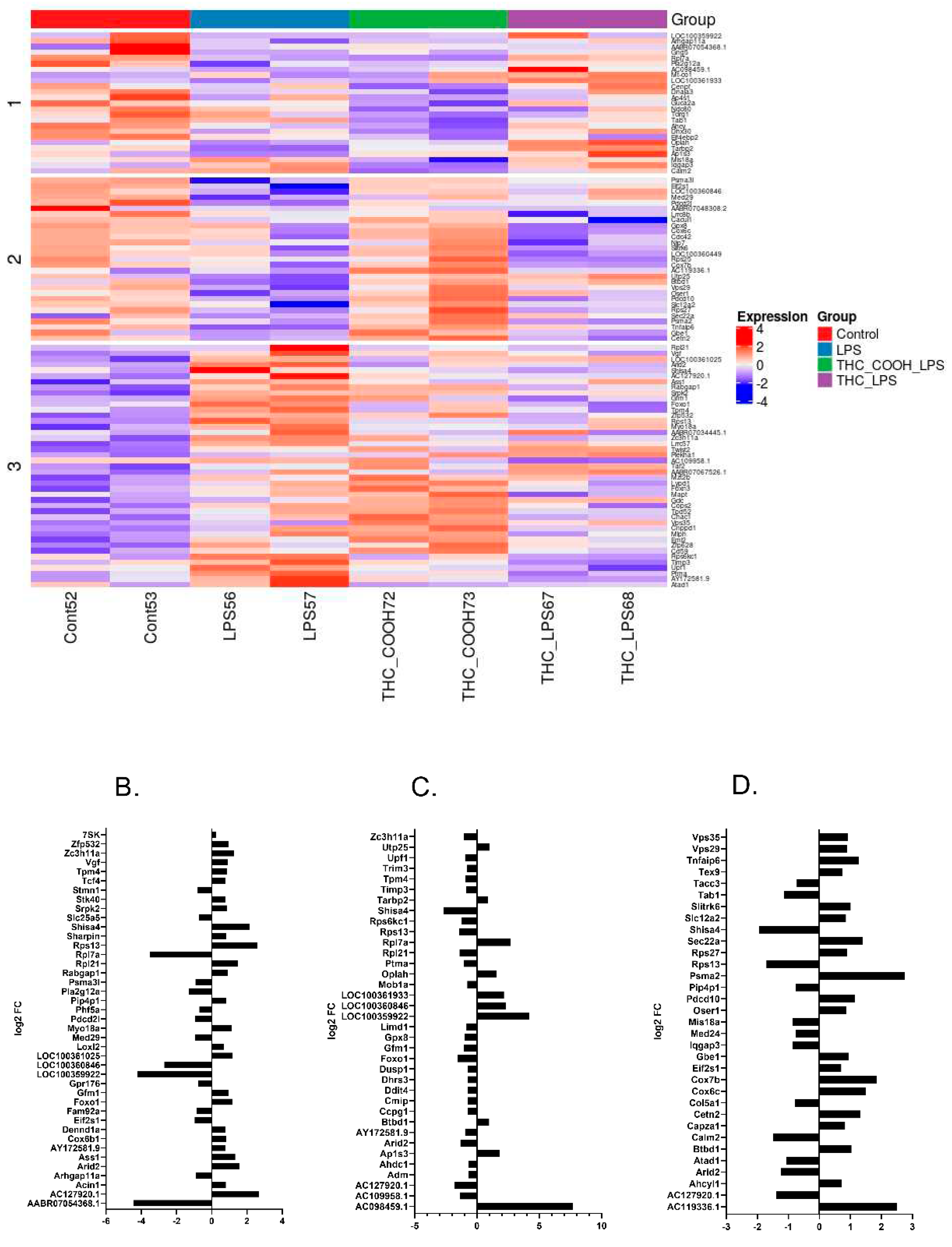

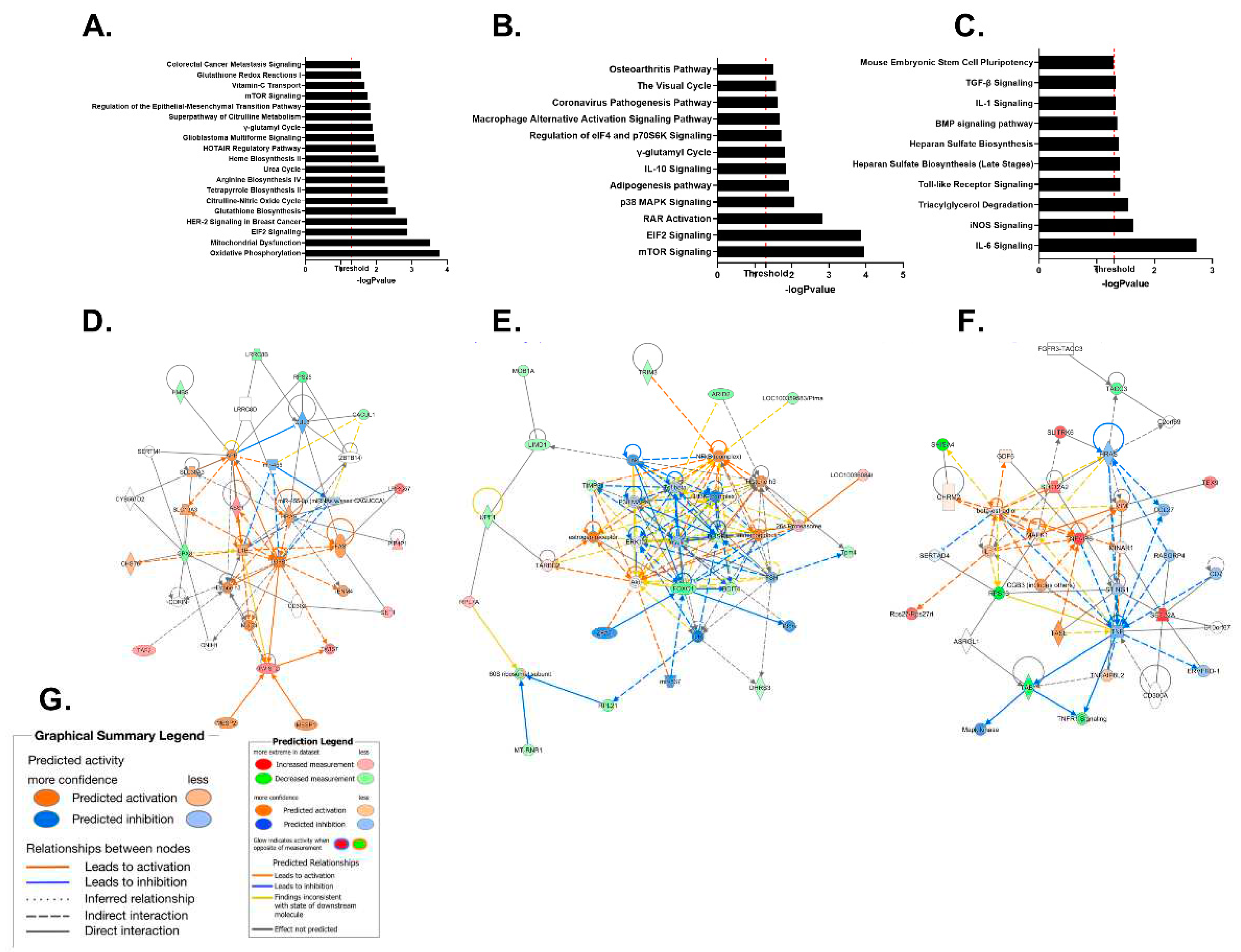

2.2. RNA Sequencing Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.1.1. J774A1 Murine Macrophages

4.1.2. Enteric Glial Cells

4.3. MTT 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

4.4. In Vitro Treatments

4.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.6. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

4.7. Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.8. RNA Sequencing Protocol and Computational Pipeline

4.9. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Uhlig, H.H. Monogenic diseases associated with intestinal inflammation: implications for the understanding of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2013, 62, 1795–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domenech, E.; Manosa, M.; Cabre, E. An overview of the natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Dis 2014, 32, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, M.F. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2014, 14, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugathasan, S.; Fiocchi, C. Progress in basic inflammatory bowel disease research. Semin Pediatr Surg 2007, 16, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guindi, M.; Riddell, R.H. Indeterminate colitis. J Clin Pathol 2004, 57, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strober, W.; Fuss, I.J.; Blumberg, R.S. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol 2002, 20, 495–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffolo, C.; Scarpa, M.; Faggian, D.; Basso, D.; D'Inca, R.; Plebani, M.; Sturniolo, G.C.; Bassi, N.; Angriman, I. Subclinical intestinal inflammation in patients with Crohn's disease following bowel resection: a smoldering fire. J Gastrointest Surg 2010, 14, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.D. The economic burden of inflammatory bowel disease: clear problem, unclear solution. Dig Dis Sci 2012, 57, 3042–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinsbroek, S.E.; Gordon, S. The role of macrophages in inflammatory bowel diseases. Expert Rev Mol Med 2009, 11, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahida, Y.R.; Patel, S.; Gionchetti, P.; Vaux, D.; Jewell, D.P. Macrophage subpopulations in lamina propria of normal and inflamed colon and terminal ileum. Gut 1989, 30, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Sica, A.; Sozzani, S.; Allavena, P.; Vecchi, A.; Locati, M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol 2004, 25, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.N.; Valentin, J.E.; Stewart-Akers, A.M.; McCabe, G.P.; Badylak, S.F. Macrophage phenotype and remodeling outcomes in response to biologic scaffolds with and without a cellular component. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 1482–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Pamer, E.G. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.; Martinez, F.O. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 2010, 32, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; Rastogi, R.; Shelke, J.; Amiji, M.M. Modulation of Macrophage Functional Polarity towards Anti-Inflammatory Phenotype with Plasmid DNA Delivery in CD44 Targeting Hyaluronic Acid Nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 16632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, K.; Le Page, L.M.; Chaumeil, M.M. Non-Invasive Differentiation of M1 and M2 Activation in Macrophages Using Hyperpolarized (13)C MRS of Pyruvate and DHA at 1.47 Tesla. Metabolites 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michetti, F.; Di Sante, G.; Clementi, M.E.; Sampaolese, B.; Casalbore, P.; Volonte, C.; Romano Spica, V.; Parnigotto, P.P.; Di Liddo, R.; Amadio, S.; et al. Growing role of S100B protein as a putative therapeutic target for neurological- and nonneurological-disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021, 127, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuss, I.J.; Neurath, M.; Boirivant, M.; Klein, J.S.; de la Motte, C.; Strong, S.A.; Fiocchi, C.; Strober, W. Disparate CD4+ lamina propria (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn's disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-gamma, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J Immunol 1996, 157, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.R.; Liu, C.Q.; Feng, B.S.; Liu, Z.J. Dysregulation of mucosal immune response in pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. World journal of gastroenterology 2014, 20, 3255–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, D.; Cheung, J.; Scheerens, H.; Poulet, F.; McClanahan, T.; McKenzie, B.; Kleinschek, M.A.; Owyang, A.; Mattson, J.; Blumenschein, W.; et al. IL-23 is essential for T cell–mediated colitis and promotes inflammation via IL-17 and IL-6. The Journal of clinical investigation 2006, 116, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, K.A.; Savidge, T.C. Reprint of: Role of enteric neurotransmission in host defense and protection of the gastrointestinal tract. Auton Neurosci 2014, 182, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquenlorge, S.; Duchalais, E.; Chevalier, J.; Cossais, F.; Rolli-Derkinderen, M.; Neunlist, M. Modulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced neuronal response by activation of the enteric nervous system. Journal of neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorak, A.M.; Onderdonk, A.B.; McLeod, R.S.; Monahan-Earley, R.A.; Cullen, J.; Antonioli, D.A.; Blair, J.E.; Morgan, E.S.; Cisneros, R.L.; Estrella, P.; et al. Axonal necrosis of enteric autonomic nerves in continent ileal pouches. Possible implications for pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. Annals of surgery 1993, 217, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geboes, K.; Collins, S. Structural abnormalities of the nervous system in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 1998, 10, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, C.; Sarnelli, G.; Esposito, G.; Grosso, M.; Petruzzelli, R.; Izzo, P.; Calì, G.; D'Armiento, F.P.; Rocco, A.; Nardone, G.; et al. Increased mucosal nitric oxide production in ulcerative colitis is mediated in part by the enteroglial-derived S100B protein. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 2009, 21, 1209–e1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, G.; Cirillo, C.; Sarnelli, G.; De Filippis, D.; D'Armiento, F.P.; Rocco, A.; Nardone, G.; Petruzzelli, R.; Grosso, M.; Izzo, P.; et al. Enteric glial-derived S100B protein stimulates nitric oxide production in celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, G.; Wang, B.; Stanghellini, V.; de Giorgio, R.; Cremon, C.; Di Nardo, G.; Trevisani, M.; Campi, B.; Geppetti, P.; Tonini, M.; et al. Mast cell-dependent excitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Horin, S.; Chowers, Y. Neuroimmunology of the gut: physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. Current opinion in pharmacology 2008, 8, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, H.; Derkinderen, P.; Gomes, P.; Chevalier, J.; Aubert, P.; Masson, D.; Galmiche, J.P.; Vanden Berghe, P.; Neunlist, M.; Lardeux, B. Enteric glial cells protect neurons from oxidative stress in part via reduced glutathione. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2010, 24, 1082–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savidge, T.C.; Newman, P.; Pothoulakis, C.; Ruhl, A.; Neunlist, M.; Bourreille, A.; Hurst, R.; Sofroniew, M.V. Enteric glia regulate intestinal barrier function and inflammation via release of S-nitrosoglutathione. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1344–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, K.R.; Mirsky, R. Astrocyte-like glia in the peripheral nervous system: an immunohistochemical study of enteric glia. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 1983, 3, 2206–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabarrocas, J.; Savidge, T.C.; Liblau, R.S. Role of enteric glial cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Glia 2003, 41, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capoccia, E.; Cirillo, C.; Gigli, S.; Pesce, M.; D'Alessandro, A.; Cuomo, R.; Sarnelli, G.; Steardo, L.; Esposito, G. Enteric glia: A new player in inflammatory bowel diseases. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology 2015, 28, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, C.; Sarnelli, G.; Esposito, G.; Turco, F.; Steardo, L.; Cuomo, R. S100B protein in the gut: the evidence for enteroglial-sustained intestinal inflammation. World journal of gastroenterology 2011, 17, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.A.; Ao, Y.; Sofroniew, M.V. Heterogeneity of reactive astrocytes. Neuroscience letters 2014, 565, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha Franceschi, R.; Nardin, P.; Machado, C.V.; Tortorelli, L.S.; Martinez-Pereira, M.A.; Zanotto, C.; Gonçalves, C.A.; Zancan, D.M. Enteric glial reactivity to systemic LPS administration: Changes in GFAP and S100B protein. Neuroscience research 2017, 119, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Boyen, G.B.; Steinkamp, M.; Geerling, I.; Reinshagen, M.; Schäfer, K.H.; Adler, G.; Kirsch, J. Proinflammatory cytokines induce neurotrophic factor expression in enteric glia: a key to the regulation of epithelial apoptosis in Crohn's disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2006, 12, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.C.; Mackie, K. Review of the Endocannabinoid System. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2021, 6, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotenhermen, F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003, 42, 327–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, P.; Hurst, D.P.; Reggio, P.H. Molecular Targets of the Phytocannabinoids: A Complex Picture. Progress in the chemistry of organic natural products 2017, 103, 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharkey, K.A.; Wiley, J.W. The Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Brain-Gut Axis. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, N.R.; Zhang, P.; Hogan, E.L. Thrombin activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in primary astrocyte cultures. J Cell Physiol 1995, 165, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouaboula, M.; Poinot-Chazel, C.; Bourrie, B.; Canat, X.; Calandra, B.; Rinaldi-Carmona, M.; Le Fur, G.; Casellas, P. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by stimulation of the central cannabinoid receptor CB1. Biochem J 1995, 312 Pt 2, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. Endocannabinoids mediate neuron-astrocyte communication. Neuron 2008, 57, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. Pharmacology of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Pharmacol Ther 1997, 74, 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPartland, J.M.; Duncan, M.; Di Marzo, V.; Pertwee, R.G. Are cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the endocannabinoid system? A systematic review. British journal of pharmacology 2015, 172, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautmann, S.M.; Sharkey, K.A. The Endocannabinoid System and Its Role in Regulating the Intrinsic Neural Circuitry of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Int Rev Neurobiol 2015, 125, 85–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.; Rooney, N.; Feeney, M.; Tate, J.; Robertson, D.; Welham, M.; Ward, S. Differential expression of cannabinoid receptors in the human colon: cannabinoids promote epithelial wound healing. Gastroenterology 2005, 129, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiegue, S.; Mary, S.; Marchand, J.; Dussossoy, D.; Carriere, D.; Carayon, P.; Bouaboula, M.; Shire, D.; Le Fur, G.; Casellas, P. Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur J Biochem 1995, 232, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, K.J.; Bi, G.H.; He, Y.; Galaj, E.; Gardner, E.L.; Xi, Z.X. Cannabinoid CB(1) and CB(2) receptor mechanisms underlie cannabis reward and aversion in rats. British journal of pharmacology 2019, 176, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouayek, M.; Muccioli, G.G. The endocannabinoid system in inflammatory bowel diseases: from pathophysiology to therapeutic opportunity. Trends in molecular medicine 2012, 18, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, A.A.; Fezza, F.; Capasso, R.; Bisogno, T.; Pinto, L.; Iuvone, T.; Esposito, G.; Mascolo, N.; Di Marzo, V.; Capasso, F. Cannabinoid CB1-receptor mediated regulation of gastrointestinal motility in mice in a model of intestinal inflammation. British journal of pharmacology 2001, 134, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.; Mouihate, A.; Mackie, K.; Keenan, C.M.; Buckley, N.E.; Davison, J.S.; Patel, K.D.; Pittman, Q.J.; Sharkey, K.A. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors in the enteric nervous system modulate gastrointestinal contractility in lipopolysaccharide-treated rats. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 2008, 295, G78–G87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.; Dong, S.; Lei, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Duan, J.; Fan, D. Protective effects of Sparstolonin B, a selective TLR2 and TLR4 antagonist, on mouse endotoxin shock. Cytokine 2015, 75, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattaroy, D.; Seth, R.K.; Das, S.; Alhasson, F.; Chandrashekaran, V.; Michelotti, G.; Fan, D.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P.; Diehl, A.M.; et al. Sparstolonin B attenuates early liver inflammation in experimental NASH by modulating TLR4 trafficking in lipid rafts via NADPH oxidase activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2016, 310, G510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornet, A.; Savidge, T.C.; Cabarrocas, J.; Deng, W.L.; Colombel, J.F.; Lassmann, H.; Desreumaux, P.; Liblau, R.S. Enterocolitis induced by autoimmune targeting of enteric glial cells: a possible mechanism in Crohn's disease? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2001, 98, 13306–13311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, C.; Sarnelli, G.; Turco, F.; Mango, A.; Grosso, M.; Aprea, G.; Masone, S.; Cuomo, R. Proinflammatory stimuli activates human-derived enteroglial cells and induces autocrine nitric oxide production. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 2011, 23, e372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.G.; Guimaraes, F.S.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Rossi, G.N.; Rocha, J.M.; Zuardi, A.W. Serious adverse effects of cannabidiol (CBD): a review of randomized controlled trials. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2020, 16, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atalay, S.; Jarocka-Karpowicz, I.; Skrzydlewska, E. Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Cannabidiol. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consroe, P.; Sandyk, R.; Snider, S.R. Open label evaluation of cannabidiol in dystonic movement disorders. Int J Neurosci 1986, 30, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.A.; Mechoulam, R.; Schlievert, C. Cannabidiol, a non-psychoactive component of cannabis and its synthetic dimethylheptyl homolog suppress nausea in an experimental model with rats. Neuroreport 2002, 13, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, T.; Iwawaki, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Yamamoto, I.; Kageyama, T.; Yoshimura, H. Metabolism of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol by cytochrome P450 isozymes purified from hepatic microsomes of monkeys. Life Sci 1995, 56, 2089–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, S.H. The cannabinoid acids: nonpsychoactive derivatives with therapeutic potential. Pharmacology & therapeutics 1999, 82, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happyana, N.; Agnolet, S.; Muntendam, R.; Van Dam, A.; Schneider, B.; Kayser, O. Analysis of cannabinoids in laser-microdissected trichomes of medicinal Cannabis sativa using LCMS and cryogenic NMR. Phytochemistry 2013, 87, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, W.L. Cannabinoid pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 1986, 38, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rameshprabu, N.; Moran, M.; Aurel, I.; Gopinath, S.; Smadar, W.; Marcelo, F.; Ahmad, N.; Oded, S.; Puja, K.; Diana, N.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Colon Models Is Derived from Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinolic Acid That Interacts with Additional Compounds in Cannabis Extracts. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 2017, 2, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargent, E.T.; Zaibi, M.S.; Silvestri, C.; Hislop, D.C.; Stocker, C.J.; Stott, C.G.; Guy, G.W.; Duncan, M.; Di Marzo, V.; Cawthorne, M.A. The cannabinoid Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) ameliorates insulin sensitivity in two mouse models of obesity. Nutr Diabetes 2013, 3, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, E.M.; Sticht, M.A.; Duncan, M.; Stott, C.; Parker, L.A. Evaluation of the potential of the phytocannabinoids, cannabidivarin (CBDV) and Delta(9) -tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), to produce CB1 receptor inverse agonism symptoms of nausea in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2013, 170, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, G.; Fadda, P.; McKillop-Smith, S.; Pertwee, R.G.; Platt, B.; Robinson, L. Synthetic and plant-derived cannabinoid receptor antagonists show hypophagic properties in fasted and non-fasted mice. British journal of pharmacology 2009, 156, 1154–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.J.; Weston, S.E.; Jones, N.A.; Smith, I.; Bevan, S.A.; Williamson, E.M.; Stephens, G.J.; Williams, C.M.; Whalley, B.J. Delta(9)-Tetrahydrocannabivarin suppresses in vitro epileptiform and in vivo seizure activity in adult rats. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolognini, D.; Costa, B.; Maione, S.; Comelli, F.; Marini, P.; Di Marzo, V.; Parolaro, D.; Ross, R.A.; Gauson, L.A.; Cascio, M.G.; et al. The plant cannabinoid Delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin can decrease signs of inflammation and inflammatory pain in mice. British journal of pharmacology 2010, 160, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.S.; Jeon, Y.; Kim, S.M.; Jang, J.Y.; Park, M.K.; Kim, I.-H.; Hwang, D.S.; Lim, D.-S.; Lee, H. Depletion of MOB1A/B causes intestinal epithelial degeneration by suppressing Wnt activity and activating BMP/TGF-β signaling. Cell Death & Disease 2018, 9, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.J.; Zheng, S.R.; Wang, D.M. Adrenomedullin: an important participant in neurological diseases. Neural Regen Res 2020, 15, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahil, S.K.; Twelves, S.; Farkas, K.; Setta-Kaffetzi, N.; Burden, A.D.; Gach, J.E.; Irvine, A.D.; Képíró, L.; Mockenhaupt, M.; Oon, H.H.; et al. AP1S3 Mutations Cause Skin Autoinflammation by Disrupting Keratinocyte Autophagy and Up-Regulating IL-36 Production. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2016, 136, 2251–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chwee, J.Y.; Khatoo, M.; Tan, N.Y.; Gasser, S. Apoptotic Cells Release IL1 Receptor Antagonist in Response to Genotoxic Stress. Cancer immunology research 2016, 4, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, G.; Hussey, S.; Walsh, P.T. The Diverse Roles of the IL-36 Family in Gastrointestinal Inflammation and Resolution. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2021, 27, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, M.-u.; Lorzadeh, S.; Gao, A.; Ghavami, S.; Coombs, K.M. PSMA2 knockdown impacts expression of proteins involved in immune and cellular stress responses in human lung cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2023, 1869, 166617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gade, A.K.; Douthit, N.T.; Townsley, E. Medical Management of Crohn's Disease. Cureus 2020, 12, e8351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.; Schwartz, M.; Holder-Murray, J.; Salgado Pogacnik, J. Change in paradigm: impact of an IBD medical home on the outpatient management of acute severe ulcerative colitis. BMJ Case Rep 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 765474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkas, G.; Thevissen, K.; De Brabanter, G.; Van Praet, L.; Czul-Gurdian, F.; Cypers, H.; De Kock, J.; Carron, P.; De Vos, M.; Hindryckx, P.; et al. An induction or flare of arthritis and/or sacroiliitis by vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease: a case series. Ann Rheum Dis 2017, 76, 878–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, K.C.; Ng, W.W.; Henderson, C.J.; Connor, S.J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis in a patient with ulcerative colitis on infliximab. J Crohns Colitis 2012, 6, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, T.; Zeng, H.; Kalambhe, D.; Wang, B.; Shen, X.; Huang, Y. Macrophage-based nanotherapeutic strategies in ulcerative colitis. J Control Release 2020, 320, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, K.A. Emerging roles for enteric glia in gastrointestinal disorders. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015, 125, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neunlist, M.; Rolli-Derkinderen, M.; Latorre, R.; Van Landeghem, L.; Coron, E.; Derkinderen, P.; De Giorgio, R. Enteric glial cells: recent developments and future directions. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, L.; Szymaszkiewicz, A.; Zielińska, M.; Abalo, R. The Enteric Glia and Its Modulation by the Endocannabinoid System, a New Target for Cannabinoid-Based Nutraceuticals? Molecules 2022, 27, 6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiazzo, G.; Giancola, F.; Stanzani, A.; Fracassi, F.; Bernardini, C.; Forni, M.; Pietra, M.; Chiocchetti, R. Localization of cannabinoid receptors CB1, CB2, GPR55, and PPARalpha in the canine gastrointestinal tract. Histochem Cell Biol 2018, 150, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P.D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the MTT Assay. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. British journal of pharmacology 2008, 153, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margulies, J.E.; Hammer, R.P. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol alters cerebral metabolism in a biphasic, dose-dependent mannier in rat brain. European journal of pharmacology 1991, 202, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarne, Y.; Toledano, R.; Rachmany, L.; Sasson, E.; Doron, R. Reversal of age-related cognitive impairments in mice by an extremely low dose of tetrahydrocannabinol. Neurobiol Aging 2018, 61, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkei-Gorzo, A.; Albayram, O.; Draffehn, A.; Michel, K.; Piyanova, A.; Oppenheimer, H.; Dvir-Ginzberg, M.; Racz, I.; Ulas, T.; Imbeault, S.; et al. A chronic low dose of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) restores cognitive function in old mice. Nat Med 2017, 23, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, S.; Fernandez-Troy, N.; Espel, E. Post-transcriptional regulation of TNF-alpha during in vitro differentiation of human monocytes/macrophages in primary culture. J Leukoc Biol 2002, 71, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, S.; Planas, J.V.; Goetz, F.W. LPS-stimulated expression of a tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA in primary trout monocytes and in vitro differentiated macrophages. Dev Comp Immunol 2003, 27, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, D.; Esposito, G.; Cirillo, C.; Cipriano, M.; De Winter, B.Y.; Scuderi, C.; Sarnelli, G.; Cuomo, R.; Steardo, L.; De Man, J.G.; et al. Cannabidiol reduces intestinal inflammation through the control of neuroimmune axis. PloS one 2011, 6, e28159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marzo, V. New approaches and challenges to targeting the endocannabinoid system. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Kaplan, B.L.; Pike, S.T.; Topper, L.A.; Lichorobiec, N.R.; Simmons, S.O.; Ramabhadran, R.; Kaminski, N.E. Magnitude of stimulation dictates the cannabinoid-mediated differential T cell response to HIVgp120. J Leukoc Biol 2012, 92, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuardi, A.W.; Shirakawa, I.; Finkelfarb, E.; Karniol, I.G. Action of cannabidiol on the anxiety and other effects produced by delta 9-THC in normal subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982, 76, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, K.; Mishima, K.; Hazekawa, M.; Sano, K.; Irie, K.; Orito, K.; Egawa, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Uchida, N.; Nishimura, R.; et al. Cannabidiol potentiates pharmacological effects of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol via CB(1) receptor-dependent mechanism. Brain Res 2008, 1188, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laprairie, R.B.; Bagher, A.M.; Kelly, M.E.; Denovan-Wright, E.M. Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Br J Pharmacol 2015, 172, 4790–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Yamaori, S.; Funahashi, T.; Kimura, T.; Yamamoto, I. Cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinols and cannabinol by human hepatic microsomes. Life Sci 2007, 80, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeckx, K.C.; Korthout, H.A.; van Meeteren-Kreikamp, A.P.; Ehlert, K.A.; Wang, M.; van der Greef, J.; Rodenburg, R.J.; Witkamp, R.F. Unheated Cannabis sativa extracts and its major compound THC-acid have potential immuno-modulating properties not mediated by CB1 and CB2 receptor coupled pathways. Int Immunopharmacol 2006, 6, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, C.; Paris, D.; Martella, A.; Melck, D.; Guadagnino, I.; Cawthorne, M.; Motta, A.; Di Marzo, V. Two non-psychoactive cannabinoids reduce intracellular lipid levels and inhibit hepatosteatosis. J Hepatol 2015, 62, 1382–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, B.; Pagano, E.; Orlando, P.; Capasso, R.; Cascio, M.G.; Pertwee, R.; Marzo, V.D.; Izzo, A.A.; Borrelli, F. Pure Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarin and a Cannabis sativa extract with high content in Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarin inhibit nitrite production in murine peritoneal macrophages. Pharmacological research 2016, 113, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortolani, D.; Di Meo, C.; Standoli, S.; Ciaramellano, F.; Kadhim, S.; Hsu, E.; Rapino, C.; Maccarrone, M. Rare Phytocannabinoids Exert Anti-Inflammatory Effects on Human Keratinocytes via the Endocannabinoid System and MAPK Signaling Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis, L.; Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Allara, M.; Bisogno, T.; Petrosino, S.; Stott, C.G.; Di Marzo, V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. British journal of pharmacology 2011, 163, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, B.; Borrelli, F.; Fasolino, I.; Capasso, R.; Piscitelli, F.; Cascio, M.; Pertwee, R.; Coppola, D.; Vassallo, L.; Orlando, P.; et al. The cannabinoid TRPA1 agonist cannabichromene inhibits nitric oxide production in macrophages and ameliorates murine colitis. British journal of pharmacology 2013, 169, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, A.A.; Capasso, R.; Aviello, G.; Borrelli, F.; Romano, B.; Piscitelli, F.; Gallo, L.; Capasso, F.; Orlando, P.; Di Marzo, V. Inhibitory effect of cannabichromene, a major non-psychotropic cannabinoid extracted from Cannabis sativa, on inflammation-induced hypermotility in mice. British journal of pharmacology 2012, 166, 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Starowicz, K.; Matias, I.; Pisanti, S.; De Petrocellis, L.; Laezza, C.; Portella, G.; Bifulco, M.; Di Marzo, V. Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2006, 318, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhaak, L.R.; Felth, J.; Karlsson, P.C.; Rafter, J.J.; Verpoorte, R.; Bohlin, L. Evaluation of the cyclooxygenase inhibiting effects of six major cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 2011, 34, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, M.H.; Meyermann, R.; Trautmann, K.; Morgalla, M.; Duffner, F.; Grote, E.H.; Wickboldt, J.; Schluesener, H.J. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 expressing macrophages/microglial cells and COX-2 expressing astrocytes accumulate during oligodendroglioma progression. Brain research 2000, 885, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrieux, P.; Chevillard, C.; Cunha-Neto, E.; Nunes, J.P.S. Mitochondria as a Cellular Hub in Infection and Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Z.; Ke, Y.; Sun, R.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhen, X.; Zheng, L.-T. Early glycolytic reprogramming controls microglial inflammatory activation. Journal of neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orihuela, R.; McPherson, C.A.; Harry, G.J. Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. British journal of pharmacology 2016, 173, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Bahnan, W.; Wiley, D.J.; Barber, G.; Fields, K.A.; Schesser, K. Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (eIF2) Signaling Regulates Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression and Bacterial Invasion*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 28738–28744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.G.; Nam, B.R.; Huh, J.-W.; Lee, D.-S. Isoliquiritigenin Reduces LPS-Induced Inflammation by Preventing Mitochondrial Fission in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Inflammation 2021, 44, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, S.; Zohles, F.; Lupp, A. Comprehensive comparison of three different animal models for systemic inflammation. J Biomed Sci 2017, 24, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zong, Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, J.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Deng, H. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Alleviates LPS-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress via Decreasing COX-2 Expression in Macrophages. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8, 702107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juknat, A.; Pietr, M.; Kozela, E.; Rimmerman, N.; Levy, R.; Gao, F.; Coppola, G.; Geschwind, D.; Vogel, Z. Microarray and Pathway Analysis Reveal Distinct Mechanisms Underlying Cannabinoid-Mediated Modulation of LPS-Induced Activation of BV-2 Microglial Cells. PloS one 2013, 8, e61462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dello Russo, C.; Lisi, L.; Feinstein, D.L.; Navarra, P. mTOR kinase, a key player in the regulation of glial functions: Relevance for the therapy of multiple sclerosis. Glia 2013, 61, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dello Russo, C.; Lisi, L.; Tringali, G.; Navarra, P. Involvement of mTOR kinase in cytokine-dependent microglial activation and cell proliferation. Biochemical pharmacology 2009, 78, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Wright-Jin, E.C.; Sengupta, R.; Anderson, J.B.; Heuckeroth, R.O. Cell-autonomous retinoic acid receptor signaling has stage-specific effects on mouse enteric nervous system. JCI Insight 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, K.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xie, J.; Wang, J.; He, X.; Lu, N.; Bai, A. All-trans retinoic acid attenuates experimental colitis through inhibition of NF-κB signaling. Immunology Letters 2014, 162, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Nicholatos, J.; Dreier, J.R.; Ricoult, S.J.; Widenmaier, S.B.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Manning, B.D. Coordinated regulation of protein synthesis and degradation by mTORC1. Nature 2014, 513, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouloulia, S.; Hallin, E.I.; Simbriger, K.; Amorim, I.S.; Lach, G.; Amvrosiadis, T.; Chalkiadaki, K.; Kampaite, A.; Truong, V.T.; Hooshmandi, M.; et al. Raptor-Mediated Proteasomal Degradation of Deamidated 4E-BP2 Regulates Postnatal Neuronal Translation and NF-kappaB Activity. Cell Rep 2019, 29, 3620–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühl, A.; Franzke, S.; Collins, S.M.; Stremmel, W. Interleukin-6 expression and regulation in rat enteric glial cells. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2001, 280, G1163–G1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ge, N.; Xie, M.; Sun, W.; Burlingame, S.; Pass, A.K.; Nuchtern, J.G.; Zhang, D.; Fu, S.; Schneider, M.D.; et al. Phosphorylation of Thr-178 and Thr-184 in the TAK1 T-loop Is Required for Interleukin (IL)-1-mediated Optimal NFκB and AP-1 Activation as Well as IL-6 Gene Expression*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 24497–24505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ji, C.; Dai, M.; Huang, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y. An update on the role of tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulating gene-6 in inflammatory diseases. Molecular Immunology 2022, 152, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Tabibian, J.; Venugopal, S.K.; Devaraj, S.; Jialal, I. Development of an in vitro screening assay to test the antiinflammatory properties of dietary supplements and pharmacologic agents. Clin Chem 2005, 51, 2252–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keren-Shaul, H.; Kenigsberg, E.; Jaitin, D.A.; David, E.; Paul, F.; Tanay, A.; Amit, I. MARS-seq2.0: an experimental and analytical pipeline for indexed sorting combined with single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature protocols 2019, 14, 1841–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaitin, D.A.; Kenigsberg, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Elefant, N.; Paul, F.; Zaretsky, I.; Mildner, A.; Cohen, N.; Jung, S.; Tanay, A.; et al. Massively parallel single-cell RNA-seq for marker-free decomposition of tissues into cell types. Science 2014, 343, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. 2011 2011, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köster, J.; Rahmann, S. Snakemake-a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio, Team. P. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio; 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).