Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study participants and data collection

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Sociodemographic profile, emotional management ability, and social support

2.2.2. ACEs

2.2.3. Depressive symptoms

2.2.4. Anxiety symptoms

2.2.5. NSSI, SI and SA

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Association of ACEs with NSSI, SI and SA

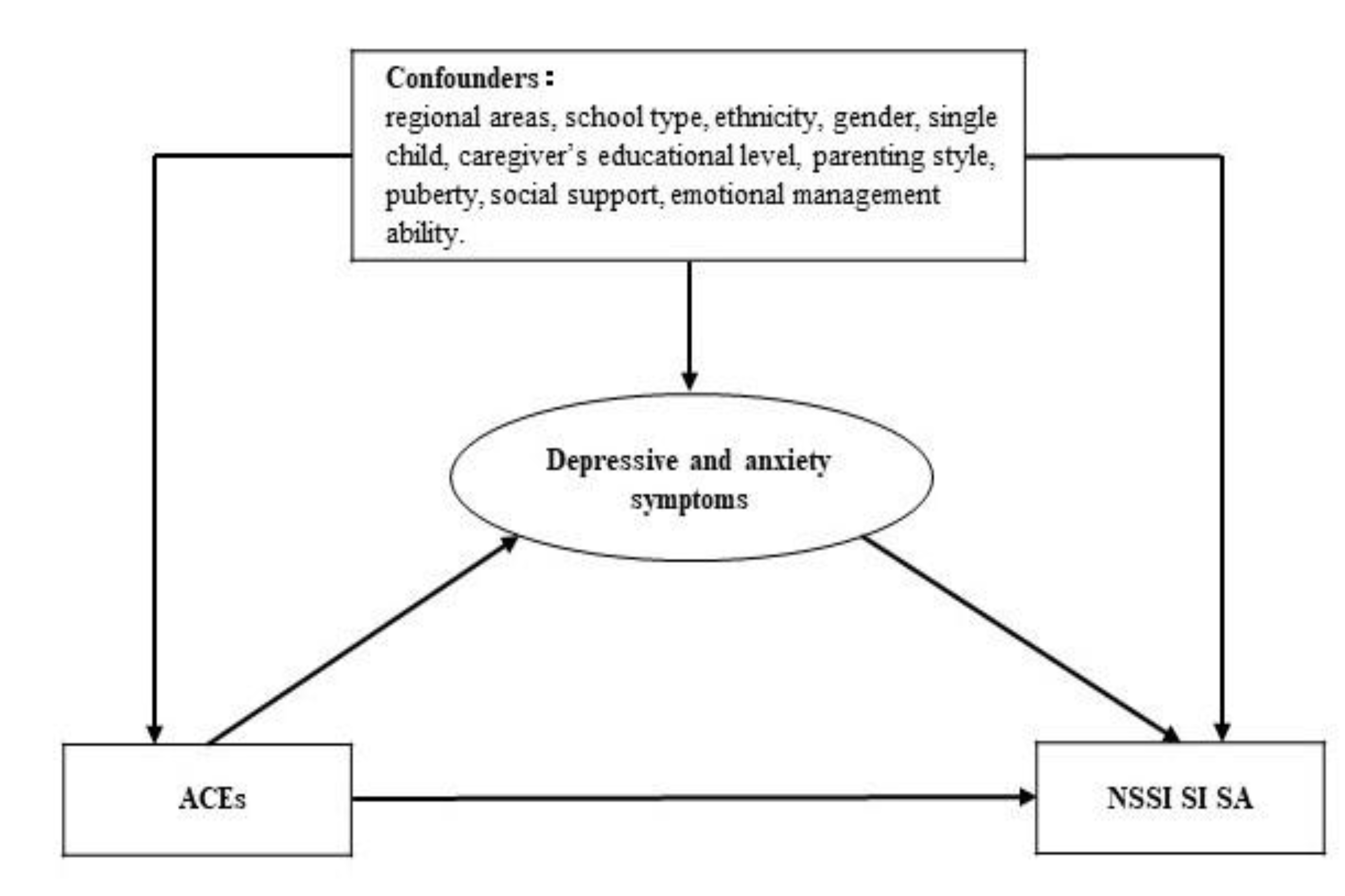

3.3. Mediation analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Associations of ACEs with NSSI, SI and SA

4.2. The mediation of depressive and anxiety symptoms on associations of ACEs with NSSI, SI and SA

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lim, K. S. , Wong, C. H., McIntyre, R. S., Wang, J., Zhang, Z., Tran, B. X., Tan, W., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. Global Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of Suicidal Behavior, Deliberate Self-Harm and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Children and Adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, G., Wu, J., Uesi, J., Jong, N., Perkes, I., Knight, K., O'Leary, F., Trudgett, C., & Bowden, M. Growth in emergency department self-harm or suicidal ideation presentations in young people: Comparing trends before and since the COVID-19 first wave in New South Wales, Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry.2022, 48674221082518. [CrossRef]

- Yard, E. , Radhakrishnan, L., Ballesteros, M. F., Sheppard, M., Gates, A., Stein, Z., Hartnett, K., Kite-Powell, A., Rodgers, L., Adjemian, J., Ehlman, D. C., Holland, K., Idaikkadar, N., Ivey-Stephenson, A., Martinez, P., Law, R., & Stone, D. M. Emergency Department Visits for Suspected Suicide Attempts Among Persons Aged 12-25 Years Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, January 2019-May 2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J. D. , Franklin, J. C., Fox, K. R., Bentley, K. H., Kleiman, E. M., Chang, B. P., & Nock, M. K. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K. , Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health, 2017; 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A. E. , Joinson, C., Roberts, E., Heron, J., Ford, T., Gunnell, D., Moran, P., Relton, C., Suderman, M., & Mars, B. Childhood adversity, pubertal timing and self-harm: a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol. Med, 2021; 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satinsky, E. N. , Kakuhikire, B., Baguma, C., Rasmussen, J. D., Ashaba, S., Cooper-Vince, C. E., Perkins, J. M., Kiconco, A., Namara, E. B., Bangsberg, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. Adverse childhood experiences, adult depression, and suicidal ideation in rural Uganda: A cross-sectional, population-based study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Nolle, K. , Lensch, T., Baxa, A., Gay, C., Larson, S., & Yang, W. Sexual Identity, Adverse Childhood Experiences, and Suicidal Behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health. 2018, 62, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y. , Chen, R., Ma, S., McFeeters, D., Sun, Y., Hao, J., & Tao, F. Associations of adverse childhood experiences and social support with self-injurious behaviour and suicidality in adolescents. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 214, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. , Wang, S., Gao, X., Jiang, Z., Xu, H., Zhang, S., Sun, Y., Tao, F., Chen, R., & Wan, Y. Patterns of adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behaviors in adolescents: A four-province study in China. J. Affect. Disord, 2021; 285, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, S. , Hall, T., Constable, L., Paton, K., Sanci, L., Goldfeld, S., & Hiscock, H. Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in Children: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2022, 149, e2021051884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C. , Wang, M., Cheng, J., Tan, Y., Huang, Y., Rong, F., Kang, C., Ding, H., Wang, Y., Yu, Y. Mediation of Internet addiction on association between childhood maltreatment and suicidal behaviours among Chinese adolescents. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2021, 30, E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrup, A. , Pedersen, C. B., Mok, P., Carr, M. J., & Webb, R. T. Self-harm risk between adolescence and midlife in people who experienced separation from one or both parents during childhood. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N. , Hou, Y., Zeng, Q., Cai, H., & You, J. Bullying Experiences and Nonsuicidal Self-injury among Chinese Adolescents: A Longitudinal Moderated Mediation Model. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iob, E. , Baldwin, J. R., Plomin, R., & Steptoe, A. Adverse childhood experiences, daytime salivary cortisol, and depressive symptoms in early adulthood: a longitudinal genetically informed twin study. Transl. Psychiatry. 2021, 11, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. M. , Nowshad, G., Dhaheri, F. A., Al-Shamsi, M. H., Al-Ketbi, A. M., Galadari, A., Joshi, P., Bendak, H., Grivna, M., & Arnone, D. Child maltreatment and neglect in the United Arab Emirates and relationship with low self-esteem and symptoms of depression. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2021, 33, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, S. M. , Varela, A., Marriott, J. P., Coleman, C. M., & Harlow, B. L. The influence of diagnosed mental health conditions and symptoms of depression and/or anxiety on suicide ideation, plan, and attempt among college students: Findings from the Healthy Minds Study, 2018-2019. J. Affect. Disord. 2022; 298, Pt A, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R. R. , Lambert, C. E., La Rochelle, M., Billet, M. I., & Fekken, G. C. Invalidating childhood environments and nonsuicidal self-injury in university students: Depression and mental pain as potential mediators. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. , Mazidi, M., Li, K., Li, Y., Chen, S., Kirwan, R., Zhou, H., Yan, N., Rahman, A., Wang, W., & Wang, Y. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F. , Mi, J. Methods for evaluating sexual development in adolescence and its relationship with metabolic syndrome. Chin. J. Evid. Based Pediatr. 2006, 1, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence. Bantam Books, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y. , Dai, X., Development of social support scale for university students. Chin. J. Clinl. Psychol. 2008, 5, 456–458. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D. P. , Ahluvalia, T., Pogge, D., & Handelsman, L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. , Guo, C., Chen, H., Wang, Y. Investigation of mental health status of pregnant women in late pregnancy and analysis of the influencing factors. Chinese Journal of Woman and Child Health Research. 2021, 32, 1162–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. , Guo, H., Guo, S., Jiao, T., Zhao, C., Ammerman, B. A., Gazimbi, M. M., Yu, Y., Chen, R., Wang, H., & Tang, J. Association of the Labor Migration of Parents With Nonsuicidal Self-injury and Suicidality Among Their Offspring in China. JAMA network open. 2021, 4, e2133596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, H. E. , von Ehrenstein, O. S., & Tomiyama, A. J. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Use of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco Products. J. Community Health. 2016, 41, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. , Xi, B., Li, Z., Wu, H., Zhao, M., Liang, Y., & Bovet, P. Prevalence and trends in tobacco use among adolescents aged 13-15 years in 143 countries, 1999-2018: findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Surveys. Lancet Child Adolsec. Health. 2021, 5, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J. , Chen, Z., Guo, F., Zhang, J., Yang, Y., Wang, Q. A short Chinese version of center for epidemiologic studies depression scale. Chin. J. Behav. Med & Brain. Sci. 2013, 22, 1133–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. , Bi, Y., Lao, L., Jiang, S., Application of GAD-7 in population screening for generalized anxiety disorder. Chin. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 17, 735–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. J. , Yu, Y., Wilcox, H. C., Kang, C., Wang, K., Wang, C., Wu, Y., & Chen, R. Global risks of suicidal behaviours and being bullied and their association in adolescents: School-based health survey in 83 countries. EClinical Medicine. 2020, 19, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buis, ML. , Direct and indirect effects in a logit model. Stata J. 2010, 10, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrick, M. T. , Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences From the 2011-2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 States. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suglia, S. F. , Koenen, K. C., Boynton-Jarrett, R., Chan, P. S., Clark, C. J., Danese, A., Faith, M. S., Goldstein, B. I., Hayman, L. L., Isasi, C. R., Pratt, C. A., Slopen, N., Sumner, J. A., Turer, A., Turer, C. B., Zachariah, J. P., & American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Childhood and Adolescent Adversity and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e15–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. T. , Scopelliti, K. M., Pittman, S. K., & Zamora, A. S. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Psychiatry 2018, 5, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. , Wang, W., Yang, J., Guo, F., & Yin, Z. The effects of alexithymia, experiential avoidance, and childhood sexual abuse on non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation among Chinese college students with a history of childhood sexual abuse. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S. A. , Clark, C., Smuk, M., Power, C., Davidson, T., & Rodgers, B. Childhood adversity and midlife suicidal ideation. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armiento, J. , Hamza, C. A., Stewart, S. L., & Leschied, A. Direct and indirect forms of childhood maltreatment and nonsuicidal self-injury among clinically-referred children and youth. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 200, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, J. M. , Carter, J. D., Luty, S. E., Mulder, R. T., Frampton, C. M., & Joyce, P. R. Childhood predictors of lifetime suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury in depressed adults. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2016, 50, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K. , Saunders, K. E., & O'Connor, R. C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012, 379, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R. , Munafò, M. R., Davey Smith, G., & Wootton, R. E. Examining the effect of smoking on suicidal ideation and attempts: triangulation of epidemiological approaches. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2020, 217, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, G., Aguglia, A., Amerio, A., Canepa, G., Adavastro, G., Conigliaro, C., Nebbia, J., Franchi, L., Flouri, E., & Amore, M. The Relationship Between Bullying Victimization and Perpetration and Non-suicidal Self-injury: A Systematic Review. Child psychiatry Hum. 2021, Dev. 10.1007/s10578-021-01231-5. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Ford, J. D. , & Gómez, J. M. The relationship of psychological trauma and dissociative and posttraumatic stress disorders to nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidality: a review. J. Trauma Dissociation, 2015; 16, 232–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S. , Duan, Z., Li, R., Wilson, A., Wang, Y., Jia, Q., Yang, Y., Xia, M., Wang, G., Jin, T., Wang, S., & Chen, R. Bullying victimization, bullying witnessing, bullying perpetration and suicide risk among adolescents: A serial mediation analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 273, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garisch, J. A. , & Wilson, M. S. Prevalence, correlates, and prospective predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among New Zealand adolescents: cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health. 2015, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K. , Melvin, G. A., Stanley, B., Oquendo, M. A., & Gould, M. Factors in the assessment of suicidality in youth. CNS Spectr. 2007, 12, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C. , Berglund, P., Borges, G., Nock, M., & Wang, P. S. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990-1992 to 2001-2003. JAMA, 2005; 293, 2487–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Sex | Total (n=1771) |

NSSI (n=303) |

SI (n=436) |

SA (n=147) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| males (n = 994) | females (n = 777) | |||||

| Regional areas (n, %)* | ||||||

| Qidong County | 293(29.5) | 161(20.7) | 454(25.6) | 95(31.4) | 131(30.0) | 49(33.3) |

| Guangming District | 132(13.3) | 111(14.3) | 243(13.7) | 60(19.8) | 74(17.0) | 36(24.5) |

| Zhongshan City | 569(57.2) | 505(65.0) | 1074(60.7) | 148(48.8) | 231(53.0) | 62(42.2) |

| School type (n, %)* | ||||||

| Public | 384(38.6) | 353(45.4) | 737(41.6) | 94(31.0) | 165(37.8) | 44(29.9) |

| Private | 610(61.4) | 424(54.6) | 1034(58.4) | 209(69.0) | 271(62.2) | 103(70.1) |

| Ethnicity (n, %)a | ||||||

| Han | 875(88.0) | 700(90.1) | 1575(88.9) | 265(87.5) | 378(86.7) | 130(88.4) |

| Other | 31(3.1) | 27(3.5) | 58(3.3) | 9(3.0) | 15(3.4) | 6(4.1) |

| Age (M, SD) | 12.95±0.63 | 12.91±0.62 | 12.93±0.62 | 12.91±0.69 | 12.95±0.68 | 12.91±0.70 |

| Single child (n, %) *, a | 194(19.5) | 107(13.8) | 301(17.0) | 44(14.5) | 59(13.5) | 19(12.9) |

| Caregiver’s educational level (n, %)a | ||||||

| Junior high school or below | 578(58.2) | 463(59.6) | 1041(58.8) | 180(59.4) | 262(60.2) | 90(61.2) |

| Senior high school or technical school | 223(22.4) | 186(23.9) | 409(23.1) | 77(25.4) | 113(25.9) | 36(24.5) |

| College or above | 167(16.8) | 117(15.1) | 284(16.0) | 41(13.5) | 56(12.8) | 19(12.9) |

| Parenting style (n, %)* | ||||||

| Strict | 367(36.9) | 211(27.0) | 578(32.7) | 85(28.1) | 117(26.8) | 33(22.4) |

| Pamper | 43(4.3) | 24(3.1) | 67(3.8) | 11(3.6) | 18(4.1) | 5(3.4) |

| Indulge/Rude/Frequently changing | 124(12.5) | 96(12.4) | 220(12.4) | 69(22.8) | 98(22.5) | 43(29.3) |

| Open-minded | 449(45.2) | 439(56.5) | 888(50.1) | 135(44.6) | 197(45.2) | 63(42.9) |

| Puberty (n, %)* | 648(65.2) | 724(93.2) | 1372(77.5) | 257(84.8) | 359(82.3) | 125(85.0) |

| ACEs (n, %) | ||||||

| Have no close friends | 35(3.6) | 31(4.1) | 66(3.8) | 25(8.6) | 27(6.4) | 14(9.9) |

| Smoking * | 26(2.6) | 6(0.8) | 32(1.8) | 12(4.0) | 18(4.1) | 11(7.5) |

| Parents divorced | 73(7.3) | 58(7.5) | 131(7.4) | 31(10.2) | 46(10.6) | 22(15.0) |

| Parent-child separation * | 464(46.7) | 316(40.7) | 780(44.0) | 174(57.4) | 234(53.7) | 85(57.8) |

| Family income <5000 RMB/month * | 344(34.6) | 321(41.3) | 665(37.5) | 115(38.0) | 167(38.3) | 57(38.8) |

| Family history of psychiatric diseases | 13(1.3) | 8(1.0) | 21(1.2) | 8(2.6) | 8(1.8) | 4(2.7) |

| Poor living environment | 323(32.5) | 273(35.1) | 596(33.7) | 136(44.9) | 181(41.5) | 74(50.3) |

| Emotional abuse | 324(32.6) | 313(40.3) | 637(36.0) | 187(61.7) | 264(60.6) | 108(73.5) |

| Physical abuse * | 227(22.8) | 109(14.0) | 336(19.0) | 103(34.0) | 137(31.4) | 52(35.4) |

| Sexual abuse * | 93(9.4) | 32(4.1) | 125(7.1) | 37(12.2) | 51(11.7) | 24(16.3) |

| Emotional neglect | 558(56.1) | 444(57.1) | 1002(56.6) | 228(75.2) | 326(74.8) | 113(76.9) |

| Physical neglect * | 503(50.6) | 332(42.7) | 835(47.1) | 179(59.1) | 247(56.7) | 95(64.6) |

| Being bullied | 254(25.6) | 219(28.2) | 473(26.7) | 149(49.2) | 208(47.7) | 82(55.8) |

| Total number of ACEs (n, %) | ||||||

| 0-2 | 391(39.3) | 325(41.8) | 716(40.4) | 50(16.5) | 92(21.1) | 22(15.0) |

| 3-4 | 354(35.6) | 253(32.6) | 607(34.3) | 112(37.0) | 143(32.8) | 38(25.9) |

| ≥5 | 249(25.1) | 199(25.6) | 448(25.3) | 141(46.5) | 201(46.1) | 87(59.2) |

| Depressive symptoms (n, %)* | 164(16.5) | 193(24.8) | 357(20.2) | 151(49.8) | 212(48.6) | 99(67.3) |

| Anxiety symptoms (n, %)* | 278(28.0) | 270(34.7) | 548(30.9) | 202(66.7) | 262(60.1) | 114(77.6) |

| Emotional management ability (M, SD)* | 11.76±3.16 | 10.99±3.14 | 11.42±3.18 | 9.22±3.11 | 9.25±2.95 | 8.50±2.99 |

| Social support (M, SD) * | 67.93±15.74 | 66.27±16.03 | 67.20±15.88 | 57.84±18.35 | 57.73±17.50 | 53.68±18.15 |

| ACEs | NSSI (n, %) | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | ||||

| Have no close friend | No(n=1657) | 265(16.0) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=66) | 25(37.9) | 3.20(1.92-5.36) | <0.001 | 1.65(0.86-3.15) | 0.131 | ||

| Smoking | No(n=1739) | 291(16.7) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=32) | 12(37.5) | 2.99(1.44-6.18) | 0.002 | 2.41(1.01-5.75) | 0.048 | ||

| Parents divorced | No(n=1640) | 272(16.6) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=131) | 31(23.7) | 1.56(1.02-2.38) | 0.038 | 1.04(0.62-1.74) | 0.898 | ||

| Parent-child separation | No(n=991) | 129(13.0) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=780) | 174(22.3) | 1.92(1.49-2.46) | <0.001 | 1.80(1.28-2.54) | 0.001 | ||

| Family income <5000 RMB/month | No(n=1106) | 188(17.0) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=665) | 115(17.3) | 1.02(0.49-1.32) | 0.873 | 1.07(0.77-1.50) | 0.684 | ||

| Family history of psychiatric diseases | No(n=1750) | 295(16.9) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=21) | 8(38.1) | 3.04(1.25-7.39) | 0.010 | 2.39(0.82-6.99) | 0.111 | ||

| Poor living environment | No(n=1175) | 167(14.2) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=596) | 136(22.8) | 1.79(1.39-2.30) | <0.001 | 1.28(0.90-1.82) | 0.174 | ||

| Emotional abuse | No(n=1134) | 116(10.2) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=637) | 187(29.4) | 3.65(2.82-4.72) | <0.001 | 1.69(1.21-2.37) | 0.002 | ||

| Physical abuse | No(n=1435) | 200(13.9) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=336) | 103(30.7) | 2.73(2.07-3.60) | <0.001 | 2.08(1.44-3.01) | <0.001 | ||

| Sexual abuse | No(n=1646) | 266(16.2) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=125) | 37(29.6) | 2.18(1.45-3.27) | 0.003 | 1.38(0.81-2.36) | 0.244 | ||

| Emotional neglect | No(n=769) | 75(9.8) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=1002) | 228(22.8) | 2.76(2.06-3.61) | <0.001 | 1.32(0.93-1.86) | 0.121 | ||

| Physical neglect | No(n=936) | 124(13.2) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=835) | 179(21.4) | 1.79(1.39-2.30) | <0.001 | 1.42(0.98-2.07) | 0.066 | ||

| Being bullied | No(n=1298) | 154(11.9) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=473) | 149(31.5) | 3.42(2.64-4.42) | <0.001 | 1.87(1.35-2.59) | <0.001 | ||

| Total number of ACEs | 0-2(n=716) | 50(7.0) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| 3-4(n=607) | 112(18.5) | 3.01(2.12-4.29) | <0.001 | 2.04(1.39-2.99) | <0.001 | ||

| ≥5(n=448) | 141(31.5) | 6.12(4.31-8.68) | <0.001 | 2.62(1.72-3.98) | <0.001 | ||

| ACEs | SI (n, %) | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | ||||

| Have no close friend | No(n=1657) | 393(23.7) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=66) | 27(40.9) | 2.23(1.35-3.68) | 0.001 | 0.88(0.45-1.74) | 0.719 | ||

| Smoking | No(n=1739) | 418(24.0) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=32) | 18(56.3) | 4.06(2.00-8.24) | <0.001 | 4.03(1.66-9.81) | 0.002 | ||

| Parents divorced | No(n=1640) | 390(23.8) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=131) | 46(35.1) | 1.74(1.19-2.53) | 0.004 | 1.13(0.69-1.85) | 0.626 | ||

| Parent-child separation | No(n=991) | 202(20.4) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=780) | 234(30.0) | 1.67(1.35-2.08) | <0.001 | 1.42(1.07-1.90) | 0.016 | ||

| Family income <5000 RMB/month | No(n=1106) | 269(24.3) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=665) | 167(25.1) | 1.04(0.84-1.30) | 0.708 | 1.04(0.81-1.21) | 0.535 | ||

| Family history of psychiatric diseases | No(n=1750) | 428(24.5) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=21) | 8(38.1) | 1.90(0.78-4.62) | 0.149 | 1.47(0.48-4.51) | 0.502 | ||

| Poor living environment | No(n=1175) | 255(21.7) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=596) | 181(30.4) | 1.57(1.26-1.97) | <0.001 | 0.94(0.67-1.31) | 0.716 | ||

| Emotional abuse | No(n=1134) | 172(15.2) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=637) | 264(41.4) | 3.96(3.16-4.96) | <0.001 | 1.91(1.41-2.59) | <0.001 | ||

| Physical abuse | No(n=1435) | 299(20.8) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=336) | 137(40.8) | 2.62(2.03-3.37) | <0.001 | 1.80(1.27-2.57) | 0.001 | ||

| Sexual abuse | No(n=1646) | 385(23.4) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=125) | 51(40.8) | 2.26(1.55-3.28) | <0.001 | 1.35(0.81-2.23) | 0.249 | ||

| Emotional neglect | No(n=769) | 110(14.3) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=1002) | 326(32.5) | 2.89(2.27-3.68) | <0.001 | 1.78(1.28-2.49) | 0.001 | ||

| Physical neglect | No(n=936) | 189(20.2) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=835) | 247(29.6) | 1.66(1.34-2.07) | <0.001 | 1.09(0.78-1.52) | 0.622 | ||

| Being bullied | No(n=1298) | 228(17.6) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=473) | 208(44.0) | 3.68(2.92-4.64) | <0.001 | 2.08(1.54-2.81) | <0.001 | ||

| Total number of ACEs | 0-2(n=716) | 92(12.8) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| 3-4(n=607) | 143(23.6) | 2.09(1.57-2.79) | <0.001 | 1.32(0.95-1.83) | 0.093 | ||

| ≥5(n=448) | 201(44.9) | 5.52(4.14-7.36) | <0.001 | 2.13(1.48-3.07) | <0.001 | ||

| ACEs | SA (n, %) | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | ||||

| Have no close friend | No(n=1657) | 128(7.7) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=66) | 14(21.2) | 3.22(1.74-5.96) | <0.001 | 1.15(0.52-2.51) | 0.732 | ||

| Smoking | No(n=1739) | 136(7.8) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=32) | 11(34.4) | 6.17(2.92-13.07) | <0.001 | 4.21(1.62-10.98) | 0.003 | ||

| Parents divorced | No(n=1640) | 125(7.6) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=131) | 22(16.8) | 2.45(1.49-4.01) | <0.001 | 1.56(0.88-2.77) | 0.126 | ||

| Parent-child separation | No(n=991) | 62(6.3) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=780) | 85(10.9) | 1.83(1.30-2.58) | <0.001 | 1.19(0.77-1.85) | 0.520 | ||

| Family income <5000 RMB/month | No(n=1106) | 90(8.1) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=665) | 57(8.6) | 1.06(0.75-1.50) | 0.749 | 0.98(0.63-1.54) | 0.929 | ||

| Family history of psychiatric diseases | No(n=1750) | 143(8.2) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=21) | 4(19.0) | 2.64(0.88-7.96) | 0.073 | 1.74(0.49-6.17) | 0.394 | ||

| Poor living environment | No(n=1175) | 73(6.2) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=596) | 74(12.4) | 2.14(1.52-3.01) | <0.001 | 1.20(0.76-1.89) | 0.437 | ||

| Emotional abuse | No(n=1134) | 39(3.4) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=637) | 108(17.0) | 5.73(3.92-8.39) | <0.001 | 2.39(1.56-3.67) | <0.001 | ||

| Physical abuse | No(n=1435) | 95(6.6) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=336) | 52(15.5) | 2.58(1.80-3.71) | <0.001 | 1.25(0.76-2.08) | 0.998 | ||

| Sexual abuse | No(n=1646) | 123(7.5) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=125) | 24(19.2) | 2.94(1.82-4.76) | 0.002 | 1.44(0.78-2.65) | 0.244 | ||

| Emotional neglect | No(n=769) | 34(4.4) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=1002) | 113(11.3) | 2.75(1.85-4.08) | <0.001 | 1.16(0.67-1.99) | 0.594 | ||

| Physical neglect | No(n=936) | 52(5.6) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=835) | 95(11.4) | 2.18(1.54-3.10) | <0.001 | 1.10(0.71-1.69) | 0.730 | ||

| Being bullied | No(n=1298) | 65(5.0) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Yes(n=473) | 82(17.3) | 3.98(2.82-5.62) | <0.001 | 1.73(1.16-2.57) | 0.007 | ||

| Total number of ACEs | 0-2(n=716) | 22(3.1) | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |||

| 3-4(n=607) | 38(6.3) | 2.11(1.23-3.60) | 0.007 | 1.17(0.66-2.08) | 0.599 | ||

| ≥5(n=448) | 87(19.4) | 7.60(4.68-12.34) | <0.001 | 2.45(1.38-4.36) | 0.002 | ||

| OR (95%CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect, Combined |

Indirect effect, through | ||

| Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | ||||

| NSSIa | |||||

| Smoking | 2.32(1.01-5.26) | 1.49(0.66-3.35) | 1.55(1.25-1.93) | 1.21(1.03-1.42) | 1.45(1.21-1.75) |

| Parent-child separation | 1.77(1.28-2.41) | 1.54(1.13-2.10) | 1.15(1.06-1.23) | 1.07(1.03-1.13) | 1.11(1.04-1.17) |

| Emotional abuse | 2.08(1.48-2.89) | 1.27(0.89-1.84) | 1.62(1.38-1.92) | 1.27(1.12-1.46) | 1.43(1.26-1.65) |

| Physical abuse | 2.25(1.57-3.25) | 1.57(1.14-2.18) | 1.43(1.27-1.62) | 1.20(1.09-1.31) | 1.31(1.16-1.46) |

| Being bullied | 2.34(1.79-3.06) | 1.52(1.19-1.95) | 1.54(1.30-1.82) | 1.23(1.12-1.35) | 1.39(1.23-1.57) |

| SIa | |||||

| Smoking | 3.82(1.40-10.38) | 2.69(1.04-6.96) | 1.42(1.16-1.75) | 1.26(1.01-1.57) | 1.27(1.11-1.46) |

| Parent-child separation | 1.54(1.17-2.01) | 1.38(1.05-1.19) | 1.12(1.05-1.19) | 1.08(1.02-1.15) | 1.06(1.02-2.46) |

| Emotional abuse | 1.99(1.54-2.61) | 1.35(1.01-1.82) | 1.48(1.28-1.72) | 1.32(1.20-1.46) | 1.25(1.12-1.38) |

| Physical abuse | 1.95(1.46-2.61) | 1.46(1.11-1.92) | 1.34(1.20-1.49) | 1.23(1.09-1.38) | 1.17(1.08-1.27) |

| Emotional neglect | 1.79(1.30-2.44) | 1.35(1.01-1.82) | 1.31(1.16-1.48) | 1.23(1.13-1.35) | 1.13(1.06-1.20) |

| Being bullied | 2.32(1.84-2.92) | 1.63(1.30-2.08) | 1.42(1.22-1.63) | 1.27(1.17-1.38) | 1.22(1.11-2.23) |

| SAa | |||||

| Smoking | 6.05(2.32-15.96) | 3.46(1.35-8.94) | 1.75(1.34-2.29) | 1.40(1.07-1.86) | 1.52(1.22-1.90) |

| Emotional abuse | 3.63(2.36-5.64) | 1.84(1.22-2.80) | 1.97(1.58-2.46) | 1.57(1.31-1.88) | 1.52(1.27-1.80) |

| Being bullied | 2.59(1.63-3.97) | 1.43(0.98-2.12) | 1.80(1.49-2.16) | 1.46(1.26-1.70) | 1.46(1.27-1.67) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).