1. Introduction

Child abuse remains a pervasive global concern, defined by the physical maltreatment of children by parents or adult household members through acts such as hitting, pushing, choking, shaking, throwing, biting, and burning. These harmful behaviors can lead to bruises or more severe physical injuries. The World Health Organization [

1] reports that approximately one-quarter of all adults worldwide have experienced abuse during childhood. In the United States, the Department of Health and Human Services estimated that annually between 700,000 and 1.25 million children are subjected to abuse or neglect [

2]. Similarly, Taiwan's Ministry of Health and Welfare reported that from 2004 to 2018, between 4,000 and 19,000 children were abused or neglected each year [

3].

Preventing youth suicide is an urgent public health imperative. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among individuals aged 15 to 24, with reported cases of suicidal thoughts and behaviors increasing over the past decade [

4,

5]. Evidence from self-reported data and clinical assessments indicates that maltreated youth are significantly more likely to contemplate and attempt suicide [

6,

7]. A recent meta-analysis revealed that young people who have experienced any form of child abuse or neglect are 2.91 times more likely to attempt suicide and 2.36 times more likely to experience suicidal ideation compared to their non-maltreated peers [

6]. The high prevalence of child maltreatment in the United States amplifies concerns about its impact on youth suicide rates. In 2019, over 3.4 million children were involved in child maltreatment investigations in the U.S. [

8]. Furthermore, estimates suggest that 37.4% of U.S. youth will be involved in such investigations by the age of 18 [

9]. Globally, the World Health Organization (2020) [

10] estimates that approximately one billion children aged 2 to 17 experience violence, including child maltreatment, each year. These alarming statistics underscore the critical need for effective suicide prevention strategies targeting maltreated youth worldwide.

However, the relationship between adolescent abuse and suicide risk has not been thoroughly investigated. We hypothesized that adolescents who have experienced abuse are at a higher risk of future suicide. Therefore, we conducted a nationwide, population-based study to explore the association between adolescent abuse and subsequent suicide in Taiwan.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

In this study, we used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to investigate the association between adolescents abuse and the incidence of suicide over a 15-year period. Data regarding adolescents abuse events were extracted from the outpatient and hospitalization records in the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database for the study period (2000–2015).The advantage, limitation, and details of the NHIRD have been documented elsewhere [

11].

In Taiwan, the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) was established in 1995. By June 2009, it had agreements with 97% of the country's medical service providers, encompassing approximately 23 million beneficiaries—over 99% of Taiwan's population [

12]. The NHIRD records diagnoses using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes [

13].

According to Taiwan's Protection of Children and Youths Welfare and Rights Act (2003) [

14], clinicians who detect signs or symptoms of child and adolescents abuse are mandated to report their findings to authorized municipal or county agencies within 24 hours. Clinicians must exercise meticulous care when diagnosing adolescents abuse with the corresponding ICD-9-CM codes to avoid legal repercussions [

15].

Furthermore, licensed medical record technicians review and verify diagnostic codes before hospital reimbursement claims are approved [

14]. The NHIP administration also performs random audits of outpatient records and periodic reviews of inpatient claims to ensure diagnostic accuracy [

16]. Consequently, data from the NHIRD are considered reliable. For this reason, we utilized NHIRD data to investigate the association between adolescents abuse and the incidence of suicide.

2.2. Study Design and Sample

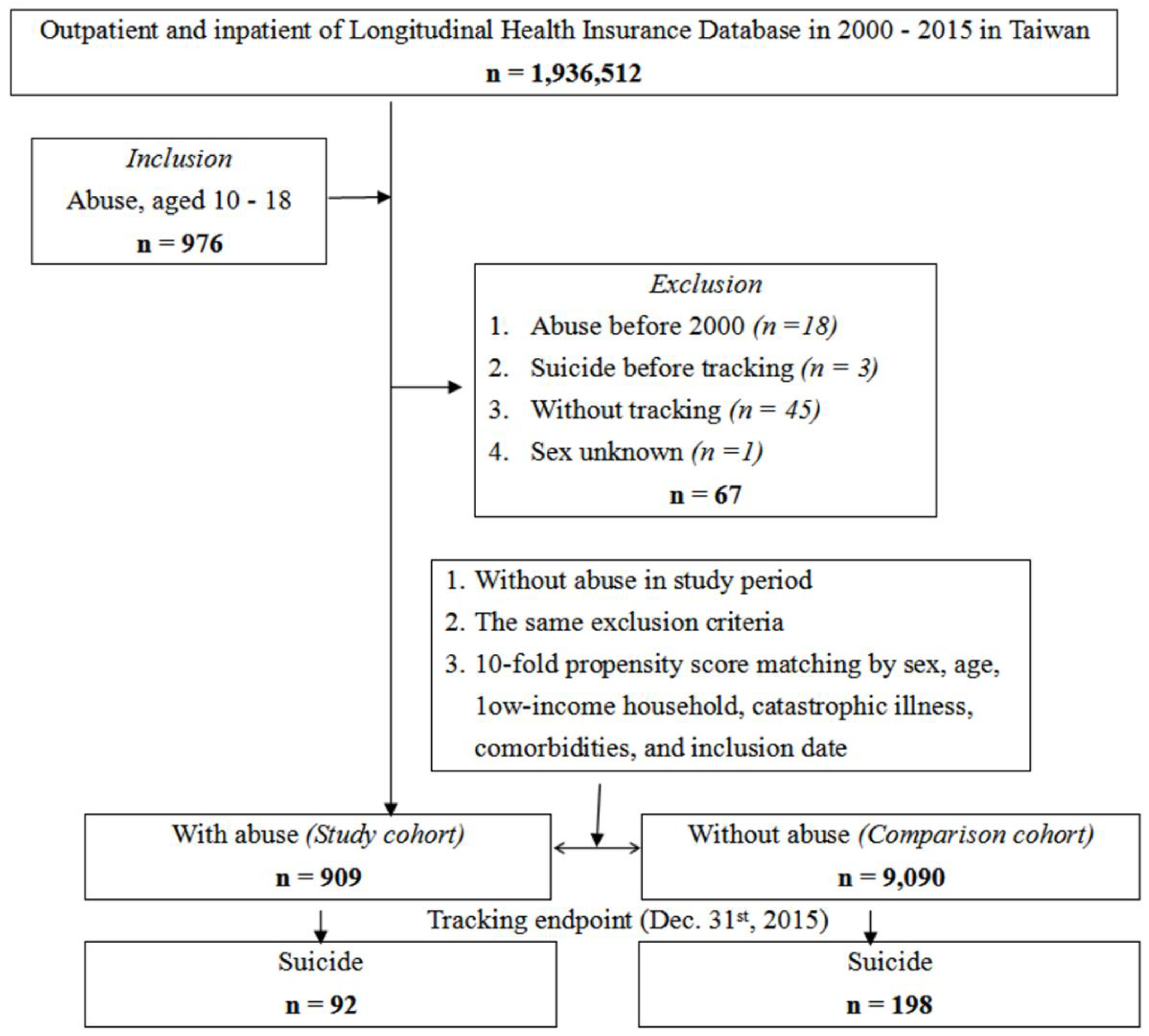

This study employed a retrospective matched-cohort design. Adolescents with a diagnosis of abuse, issued between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2015, were enrolled as the adolescent abuse cohort (n = 976). Additionally, 29,511 controls with no history of adolescent abuse throughout the study period were age-, sex-, and index year-matched (1:10) to the adolescent abuse cohort. Individuals aged over 18 or under 10 years, and those with a history of adolescent abuse or suicide prior to the index date, were excluded (

Figure 1).

Covariates incorporated into the statistical analyses encompassed a comprehensive range of demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors. Demographic variables included sex and age, while geographic variables covered the region of residence—classified as northern, central, southern, or eastern Taiwan—and the urbanization level of the residential area, stratified into four tiers based on population density and development indicators. The type of healthcare facility accessed by participants was considered, categorized as medical centers, regional hospitals, or local hospitals. Socioeconomic status was evaluated by determining whether participants belonged to low-income households. clinical covariates included the presence of catastrophic illnesses and mental disorders, identified through relevant diagnostic codes. Additionally, the season during which data were collected—spring, summer, autumn, or winter—was included to control for potential seasonal variations affecting health outcomes. The urbanization level was defined according to population size and various indicators of development. Urbanization level 1 was defined as areas with a population of over 1,250,000 inhabitants and a specific designation of political, economic, cultural, and metropolitan development. Urbanization level 2 was defined as areas with a population between 500,000 and 1,249,999 inhabitants, playing an important role in the political system, economy, and culture. Urbanization levels 3 and 4 were defined as areas with populations of 149,999–499,999 and less than 149,999 inhabitants, respectively [

17].Comorbidities included mental disorders. The Charlson comorbidity index(CCI) score was calculated based on the presence of relevant comorbidities (according to the ICD-9-CM codes) [

18], with a score of zero indicating the absence of comorbidities and higher scores indicating a higher comorbidity burden [

19].

All participants were followed from the index date until the occurrence of suicide, withdrawal from the NHIP, or the end of 2015. Suicide methods included ingestion of solids or liquids, exposure to gases used in domestic settings, other gases and vapors, hanging, drowning, firearms, cutting and piercing, jumping, and others. The ICD-9-CM codes used to classify adolescent abuse, comorbidities, and mental disorders are listed in

Supplemental Table S1.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS software version 29(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-squared (χ²) and t-tests were used to evaluate the distributions of categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The Fisher exact test was employed to examine differences between the two cohorts in terms of categorical variables. Fine-Gray survival analysis was utilized to determine the risk of suicide, with results presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The difference in suicide risk between adolescents who experienced violence and the control cohort was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. Bonferroni-correction for multiple comparisons was applied. A two-tailed Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.001 was considered statistically significant.

2.4. Ethics Approvals

This study was conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). The Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital approved this study (IRB No. 2-107-05-026).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

We identified 909 adolescents with a documented history of abuse and selected 9,090 matched controls without such a history. The demographic and clinical characteristics of both groups are summarized in

Table 1. The mean age of adolescents in the abuse cohort was 14.18 ± 4.72 years, with a higher proportion of females than males. Notably, significant differences between the abuse and control cohorts were observed in terms of geographical location and urbanization levels.

3.2. Characteristics of the Study Population at Endpoint

By the end of the study period, 92 out of 909 adolescents who had experienced abuse (10.12%) died by suicide, compared to 198 out of 9,090 individuals in the control group (2.18%), demonstrating a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001;

Table 2). Significant disparities were observed between the abuse-exposed and control groups concerning geographical location and urbanization level. In contrast, there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding sex, age, low-income household status, presence of catastrophic illnesses, mental disorders, CCI scores, season, or level of care. Comprehensive data are presented in

Table 2.

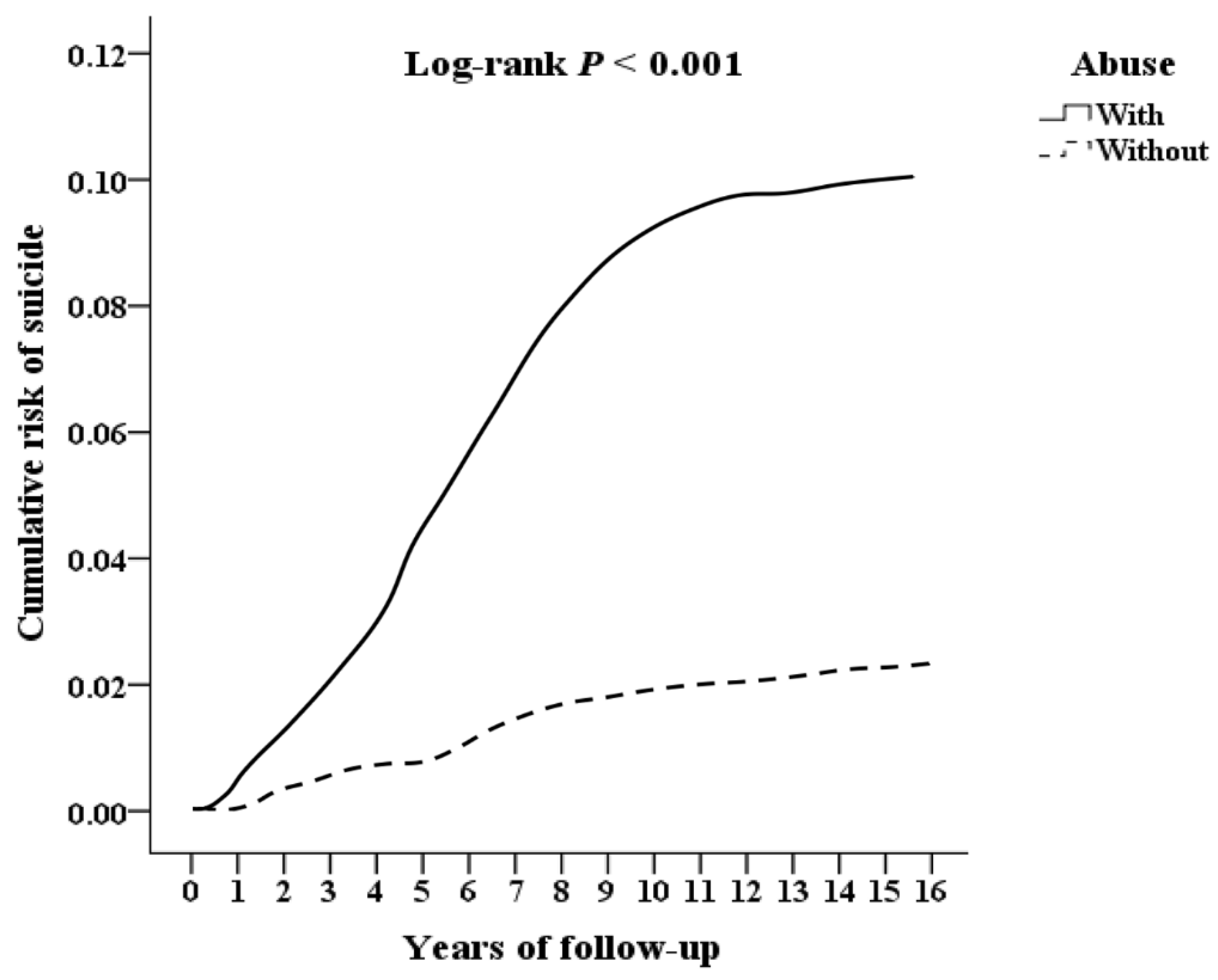

3.3. Risk of Suicide According to Adolescent Abuse Exposure

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that the adolescent abuse cohort exhibited a significantly higher cumulative incidence of suicide over the 15-year follow-up period compared to the matched control group (log-rank test, P < 0.001;

Figure 2).

3.4. Factors of Suicide by Using Cox Regression

Table 3 presents the results of the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis examining factors associated with suicide risk among adolescents who experienced abuse. The unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for suicide in the abuse cohort was 1.787 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.246–2.033; p < 0.001), indicating a significantly elevated risk compared to the control group. After adjusting for multiple covariates—including sex, age group, low-income household status, presence of catastrophic illness, mental disorders, CCI score, season, geographic location, urbanization level, and level of care—the association remained significant. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) was 1.592 (95% CI: 1.137–1.993; p < 0.001), suggesting that adolescent abuse is independently associated with an increased risk of suicide. Several covariates were also significantly correlated with suicide risk. Notably, females exhibited a higher risk compared to males (aHR: 1.523; 95% CI: 1.072–1.831; p = 0.012). Additionally, the presence of mental disorders and higher levels of care were associated with an increased incidence of suicide (p < 0.05).

3.5. Factors of Suicide Stratified by Variables Listed in the Table by Using Cox Regression and Bonferroni Correction for Multiple Comparisons

The patients were stratified by the variables presented in

Table 3, and adjusted hazard ratios of different subgroups were calculated (

Table 4). Over the course of the study, adolescents who had experienced abuse exhibited 92 suicide events over 7,074.36 person-years (PY) of observation, resulting in an incidence rate of 1,300.47 per 100,000 PYs. In contrast, the control group encountered 198 suicide events over 69,894.12 PYs, corresponding to an incidence rate of 283.29 per 100,000 PYs. After applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, the risk of suicide was significantly higher among adolescents with a history of abuse compared to those without such a history. The aHR was1.592 (95% CI: 1.137–1.993; p < 0.001), indicating that abused adolescents had nearly a 1.5 fold increased risk of suicide. Notably, the presence of mental disorders and higher levels of care were significantly associated with an increased incidence of suicide, the aHR was2.369 (95% CI: 2.369 –2.972; p < 0.001).

3.6. Factors of Suicide Subgroups by Using Cox Regression and Bonferroni Correction for Multiple Comparisons

Abused adolescents exhibited a significantly elevated risk of suicide across various methods. Specifically, the adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) for different suicide methods were as follows: ingestion of solids or liquids (AHR = 1.607), exposure to other gases and vapors (AHR = 1.714), hanging (AHR = 2.058), cutting and piercing (AHR = 1.656), and jumping (AHR = 1.523)(

Table 5).

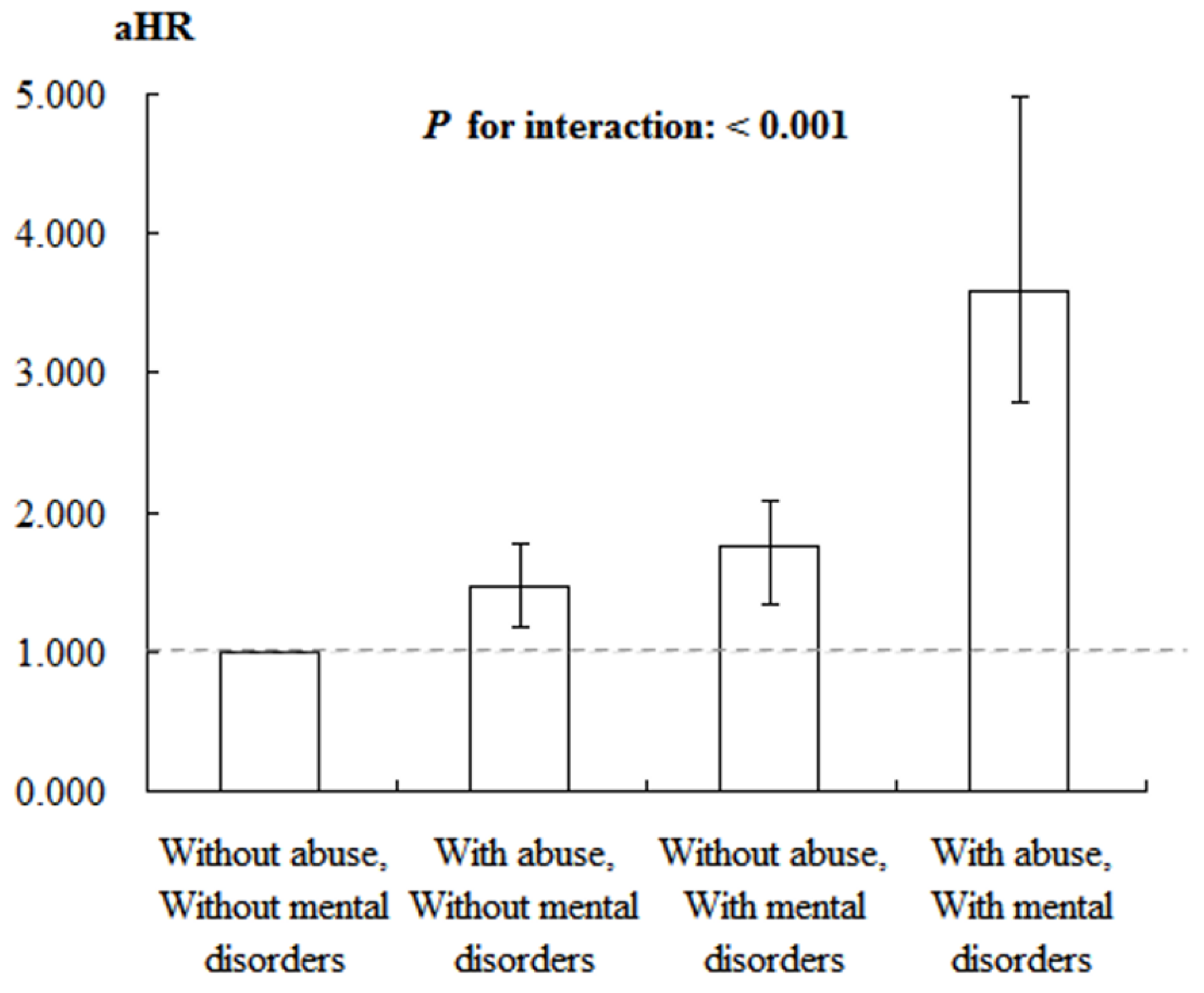

3.7. Factors of Suicide Stratified by Abuse and Mental Disorders by Using Cox Regression

The analysis of suicide risk factors using the Cox regression model indicates a significant impact of both abuse and mental disorders on suicide risk. In the reference group, which included individuals without a history of abuse or mental disorders, the aHR was set at 1.000. In comparison, individuals without abuse history but with mental disorders exhibited a significantly elevated risk of suicide, with an aHR of 1.465 (95% CI: 1.172-1.779, P < 0.001). Among those who experienced abuse but did not have mental disorders, the suicide risk increased further, with an aHR of 1.756 (95% CI: 1.340-2.075, P < 0.001). Furthermore, individuals who experienced both abuse and had mental disorders showed the highest risk of suicide, with an aHR of 3.586 (95% CI: 2.781-4.986, P < 0.001). Additionally, the interaction between abuse and mental disorders was significant, as indicated by the P for interaction value (P < 0.001), highlighting a notable synergistic effect that further elevated the risk of suicide (

Table 6、

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

This study examined the relationship between adolescent abuse and suicidal behaviors, assessing whether all forms of adolescent abuse were associated with an increased risk of suicidality in both univariate logistic regression models and multivariable logistic regression models that controlled for covariates. In our study, we found that the suicide rate of adolescents who have experienced violence was significantly higher than that of the control group (10.12 % vs. 2.18 % ; P<0.001) with aHR 1.592 after 15 years of observation. The result is consistent with Zygo, et al. [

20], which demonstrated that psychological, physical violence, and family violence were all the risk factor for not only suicide ideation but also suicide attempt and even suicide death. The findings of this study align with those of numerous other investigations [

21,

22,

23]. However, an alternative study suggests that emotional abuse is the most significant predictor of suicide attempts, with physical abuse following closely behind [

24]. Several theories may account for the relationship between childhood abuse and suicidality. The Schematic Appraisals Model for Suicide posits that negative childhood experiences can foster a growing sense of self-defeat, ultimately leading individuals to perceive suicidality as an escape mechanism [

25,

26]. From a biological standpoint, prior research has shown that individuals who experienced childhood abuse tend to have a reduced prefrontal cortex volume [

27], which is associated with cognitive functions [

28], and cognitive deficits, in turn, are linked to increased suicidality [

29].

We observed that adolescent abuse victims committed suicide when they were 14 years old. In a study from America [

20], the peak of suicide in rural or urban area was 16 to 18 years old, which was consistent to our research. Both the studies reminded us of closely monitoring and observing the mental and psychologic status for the youth in this period. Thus, concerns and caution should rise keenly for the adolescents in some situation, such as unusual wounds or bruises, rapid mood change, weird behavior, abnormal vaginal bleeding, and relationship with schoolmates. Besides, with the development of technology, electronic bully is worth being noticed. According to the study [

30] with data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in America, not only physical bullying but electronic bullying increased the risk for suicide ideation and attempt, pointing out the importance of education of internet politeness and online social contact for youth.The risk factors for suicide of adolescence and youth included history of violence, female, young age (10 to 24 years old), psychological disorders, depression, substance use in Taiwan, which was similar to the results in other regions around the world [

20,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], indicating somewhat resemble biophysical mechanism crossing ethnics. However, in a study in America [

30], Asian adolescents are more prone to have suicide ideation and attempt than other ethnics, making it important for Asian educators and family members to pay more attention for their adolescents, including Taiwan.

The methods and tools for adolescent suicide may be different in distinct countries or cultures. In our study, the most common methods were consumption of liquid or solid components in both the group with/without being the victims of violence, while in a review article in Iraq [

33], the method of suicide is self-hanging, followed by firearms, self-burning, and self-poisoning. Thus, it is important for different countries to formulate policies exclusively, such as gun control, chemicals restriction for less accessibility, or prohibition for entrance to top floor in tall buildings.

Abuse is caused by the presence of multiple risk factors and a combination of very few protective factors. Abuse can be prevented by reducing risk factors and strengthening protective factors. Doing this requires comprehensive policies that form part of a so-called “integrated approach” to abuse prevention—in other words, an overall strategy that depends on the cooperation of many different sectors. Violence prevention, therefore, requires interventions at all levels of the ecological model and every stage of the abuse life cycle [

36,

37].

This study has several limitations. First, the potential for selection bias cannot be excluded. Additionally, the detection rate of child abuse is likely underestimated for younger children, who typically visit the hospital with a parent or caregiver. If the abuser is the parent or caregiver, the likelihood of bringing the child in for medical evaluation diminishes, meaning such incidents may not be recorded in the NHIRD. Consequently, the actual risk warrants further in-depth investigation. Second, other potential confounding factors, such as social support systems and family dynamics, should be considered in future studies. Third, the coding practices of clinicians could influence the study's outcomes, and it is possible that the results presented herein are an underestimation. Finally, in accordance with regulations set by the Health and Welfare Data Center (HWDC) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) of Taiwan, obtaining new analysis results in the short term is not feasible. Even if new data becomes available, it is unlikely to alter the direction of our findings. The primary aim of this study is to observe the trends in suicide of adolescents abuse victims in Taiwan over time. Notably, the dataset utilized represents a sample of 2 million individuals, a subset of Taiwan's 23 million population, which is sufficiently large to provide a robust reflection of the broader societal trends.

5. Conclusions

In this study, adolescents who experienced violence had a significantly higher risk of future suicide compared to the control group, with the suicide rate increasing by up to 1.592 times. Notably, among those with comorbid mental disorders, the suicide risk rose to 2.369 times that of the control group. Exposure to youth violence may lead to emotional disorders, including depression and social isolation, which subsequently elevate the risk of suicide. To reduce the occurrence of suicide, it is crucial not only to provide psychological support and pay closer attention to the mental state of youth violence victims but also for the government to implement more practical measures. These should include policy formulation, education on abuse prevention, and campus initiatives aimed at eradicating abuse.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CS, LYF, WCC; methodology, CAS, CHT, FHL; software, CHC, THW; validation, CHC, DYN, FHL; formal analysis, THW; data curation, CAS, CHT; writing original draft preparation, CS, DYN; writing review and editing, CS, LYF, WCC; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Tri-service General Hospital, grant number TSGH-B-113025 special plan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGHIRB No.:E202416033).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study uses third party data. Taiwan launched a single-payer National Health Insurance program on March 1, 1995. The database of this program contains registration files and original claim data for reimbursement. Large computerized databases derived from this system by the National Health Insurance Administration. Investigators interested may submit a formal proposal to NHIRD(

https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/cp-5119-59201-113.html) The authors confirm they did not have any special access privileges..

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude and appreciation to the HWDC, MOHW, Taiwan, for providing access to the NHIRD.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Abbreviation, ICD-9-CM, and definition.

Table A1.

Abbreviation, ICD-9-CM, and definition.

| |

Abbreviation |

ICD-9-CM / Definition |

|

Stduy population: Abuse |

|

955.5, E967 |

|

Events: Suicide |

|

E950 - E958 |

| Solid or liquid |

|

E950 |

| Gases in domestic use |

|

E951 |

| Other gases and vapors |

|

E952 |

| Hanging |

|

E953 |

| Drowning |

|

E954 |

| Firearms |

|

E955 |

| Cutting and piercing |

|

E956 |

| Jumping |

|

E957 |

| Others |

|

E958 |

| Comorbidities: |

|

|

| Mental disorders |

|

290 - 319 |

| Charlson comorbidity index |

CCI |

|

Table A2.

Years of follow-up.

Table A2.

Years of follow-up.

| Abuse |

Min |

Median |

Max |

Mean ± SD |

P |

| With |

0.02 |

7.34 |

15.72 |

7.78 ± 6.52 |

|

| Without |

0.02 |

7.30 |

15.70 |

7.69 ± 6.68 |

|

| Total |

0.02 |

7.32 |

15.72 |

7.70 ± 6.67 |

0.698 |

Table A3.

Years to suicide.

Table A3.

Years to suicide.

| Abuse |

Min |

Median |

Max |

Mean ± SD |

P |

| With |

0.02 |

5.02 |

15.68 |

6.01 ± 6.38 |

|

| Without |

0.03 |

5.29 |

15.69 |

6.48 ± 6.72 |

|

| Total |

0.02 |

5.15 |

15.69 |

6.44 ± 6.69 |

0.044 |

References

- World Health Organization. Child maltreatment. (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. In National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2019 (NSDUH–2019). Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Taiwan Data from Ministry of health and welfare. Health Statistics. Available online: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/np-126-2.html (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Curtin, S.C.; Heron, M. Death Rates Due to Suicide and Homicide Among Persons Aged 10-24: United States, 2000-2017. NCHS Data Brief 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kann, L.; McManus, T.; Harris, W.A.; Shanklin, S.L.; Flint, K.H.; Queen, B.; Lowry, R.; Chyen, D.; Whittle, L.; Thornton, J.; et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018, 67, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelakis, I.; Austin, J.L.; Gooding, P. Association of Childhood Maltreatment With Suicide Behaviors Among Young People: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e2012563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, R.E.; Byambaa, M.; De, R.; Butchart, A.; Scott, J.; Vos, T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012, 9, e1001349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Administration for Children and Families; Administration on Children, Y.a.F., & Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment 2019.

- Kim, H.; Wildeman, C.; Jonson-Reid, M.; Drake, B. Lifetime Prevalence of Investigating Child Maltreatment Among US Children. Am J Public Health 2017, 107, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on preventing violence against children 2020. 2020.

- Hsieh, C.Y.; Su, C.C.; Shao, S.C.; Sung, S.F.; Lin, S.J.; Kao Yang, Y.H.; Lai, E.C. Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database: past and future. Clin Epidemiol 2019, 11, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho Chan, W.S. Taiwan’s healthcare report 2010. EPMA Journal 2010, 1, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, C.H. ICD-9-CM english-Chinese dictionary. 2000.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Protection of Children and Youths Welfare and Rights Act.

- Taiwan Data from Ministry of health and welfare. In Taiwan Data from Ministry of health and welfare; 2019. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/lp-2985-113.html (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Ministry of Justice. National Health Insurance Reimbursement Regulations. (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Chang, C.-Y.; Chen, W.-L.; Liou, Y.-F.; Ke, C.-C.; Lee, H.-C.; Huang, H.-L.; Ciou, L.-P.; Chou, C.-C.; Yang, M.-C.; Ho, S.-Y. Increased risk of major depression in the three years following a femoral neck fracture–a national population-based follow-up study. PLoS One 2014, 9, e89867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrogan, A.; Madle, G.C.; Seaman, H.E.; De Vries, C.S. The epidemiology of Guillain-Barré syndrome worldwide: a systematic literature review. Neuroepidemiology 2009, 32, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, D.M.; Scales, D.C.; Laupacis, A.; Pronovost, P.J. A systematic review of the Charlson comorbidity index using Canadian administrative databases: a perspective on risk adjustment in critical care research. Journal of critical care 2005, 20, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zygo, M.; Pawłowska, B.; Potembska, E.; Dreher, P.; Kapka-Skrzypczak, L. Prevalence and selected risk factors of suicidal ideation, suicidal tendencies and suicide attempts in young people aged 13–19 years. Annals of agricultural and environmental medicine 2019, 26, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.B.; Esposito-Smythers, C.; Weismoore, J.T.; Renshaw, K.D. The relation between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior: a systematic review and critical examination of the literature. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2013, 16, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anteghini, M.; Fonseca, H.; Ireland, M.; Blum, R.W. Health risk behaviors and associated risk and protective factors among Brazilian adolescents in Santos, Brazil. J Adolesc Health 2001, 28, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, I.; Gillespie, E.L.; Panagioti, M. Childhood maltreatment and adult suicidality: a comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2019, 49, 1057–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Gong, J.; Cui, X.; Meng, T.; Xiao, B.; He, Y.; Shen, Y.; Luo, X. Associations between suicidal behavior and childhood abuse and neglect: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017, 220, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Gooding, P.; Tarrier, N. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: explanatory models and clinical implications, The Schematic Appraisal Model of Suicide (SAMS). Psychol Psychother 2008, 81, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Barnhofer, T.; Crane, C.; Beck, A.T. Problem solving deteriorates following mood challenge in formerly depressed patients with a history of suicidal ideation. J Abnorm Psychol 2005, 114, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoda, A.; Suzuki, H.; Rabi, K.; Sheu, Y.S.; Polcari, A.; Teicher, M.H. Reduced prefrontal cortical gray matter volume in young adults exposed to harsh corporal punishment. Neuroimage 2009, 47 Suppl 2, T66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.K.; Cohen, J.D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci 2001, 24, 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Wiktorsson, S.; Sacuiu, S.; Marlow, T.; Östling, S.; Fässberg, M.M.; Skoog, I.; Waern, M. Cognitive Function in Older Suicide Attempters and a Population-Based Comparison Group. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2016, 29, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labuhn, M.; LaBore, K.; Ahmed, T.; Ahmed, R. Trends and instigators among young adolescent suicide in the United States. Public Health 2021, 199, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda-Mendizabal, A.; Castellví, P.; Parés-Badell, O.; Alayo, I.; Almenara, J.; Alonso, I.; Blasco, M.J.; Cebrià, A.; Gabilondo, A.; Gili, M.; et al. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health 2019, 64, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero-Domínguez, C.C.; Campo-Arias, A. Prevalence and Factors Associated With Suicide Ideation in Colombian Caribbean Adolescent Students. Omega (Westport) 2022, 85, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, M.S.; Lafta, R.K. Suicide and suicidality in Iraq: a systematic review. Med Confl Surviv 2023, 39, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, L.; Yun, K.; Pocock, N.; Zimmerman, C. Exploitation, Violence, and Suicide Risk Among Child and Adolescent Survivors of Human Trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion. JAMA Pediatr 2015, 169, e152278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIsaac, M.B.; Bugeja, L.; Weiland, T.; Dwyer, J.; Selvakumar, K.; Jelinek, G.A. Prevalence and Characteristics of Interpersonal Violence in People Dying From Suicide in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pac J Public Health 2018, 30, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-H.; Wei, A.-M. Research on Crime Prevention Systems and Strategies; Central Police University: Taoyuan City, Taiwan, 2005; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office Police Service Violent Crime. Home Office Police Service Global Information Network.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).