1. Introduction

In contrast to deaths from influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) autopsy specimens demonstrated pulmonary artery (PA) wall thickening and vascular smooth muscle enlargement [

1]. Pulmonary hypertension was prevalent in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients [

2], found by echocardiography in 39% of COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) patients and associated with mortality [

3]. COVID-19 survivors experiencing fatigue and exercise limitations after hospital discharge were found to have pulmonary hypertension by right heart catheterization [

4]. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S1 subunit spike protein alone is sufficient to elicit cell signaling in human PA cells, raising the possibility that full-length spike protein from mRNA vaccines could also cause vascular remodeling and clinically significant pulmonary hypertension [

5].

2. Case Description

We report here two cases of pulmonary hypertension after the second dose of the Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2).

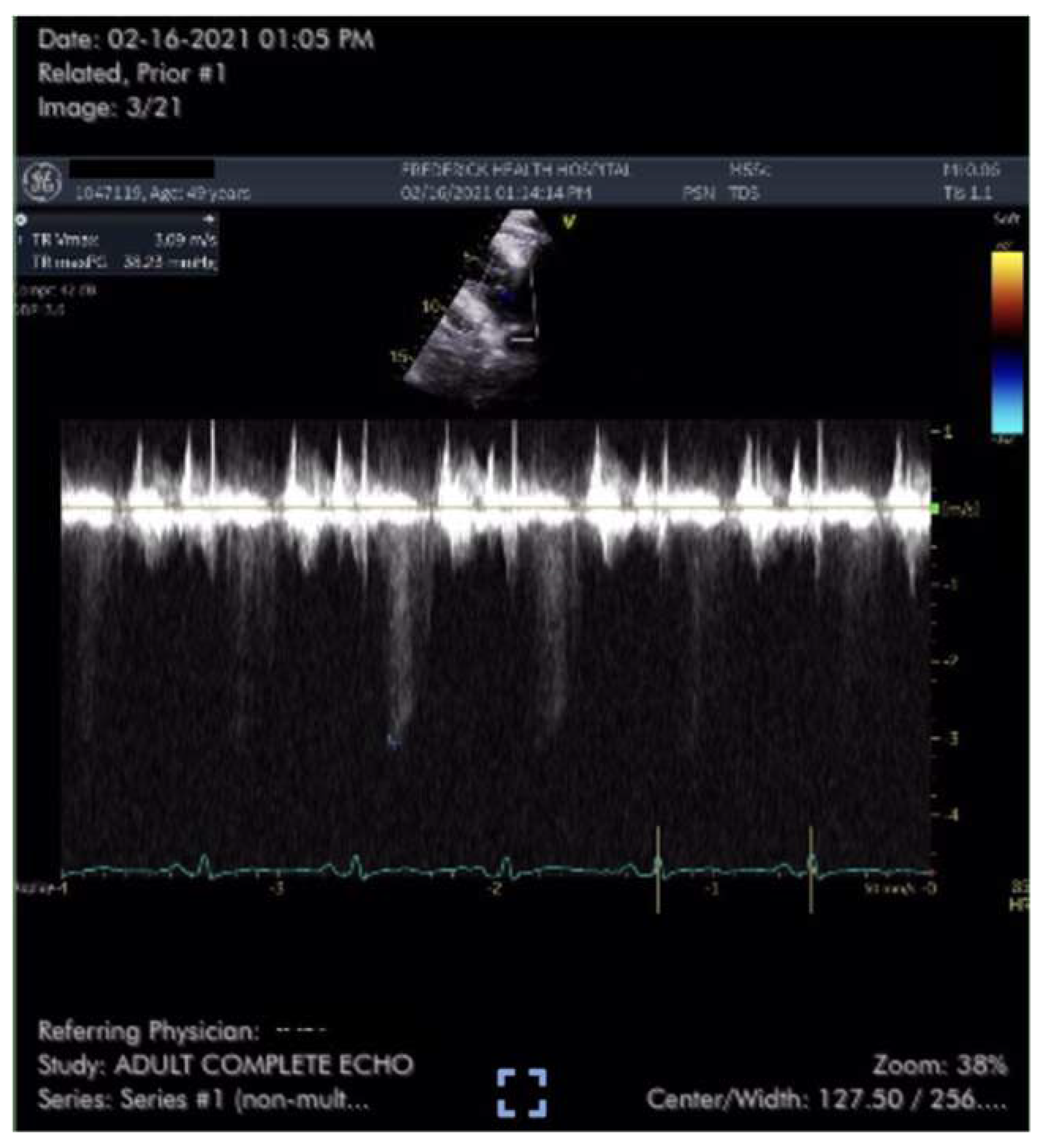

Case #1 is a previously healthy 49-year-old male physician athlete, body mass index (BMI) 23, non-smoker with a history of mild exercise-induced asthma treated with albuterol. Patient completed the primary series of Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) in January 2021. Approximately three weeks after the second dose patient suddenly developed severe fatigue, flu-like symptoms, tachycardia, palpitations, orthostasis, right-sided chest pressure and dyspnea on exertion. COVID PCR testing was negative. Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed normal left ventricular function with an ejection fraction (EF) of 65%, normal right ventricular size and function and a tricuspid regurgitation (TR) jet of 3.09 m/s (

Figure 1). Estimated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) of 42 mmHg was interpreted as mild/moderate pulmonary hypertension (

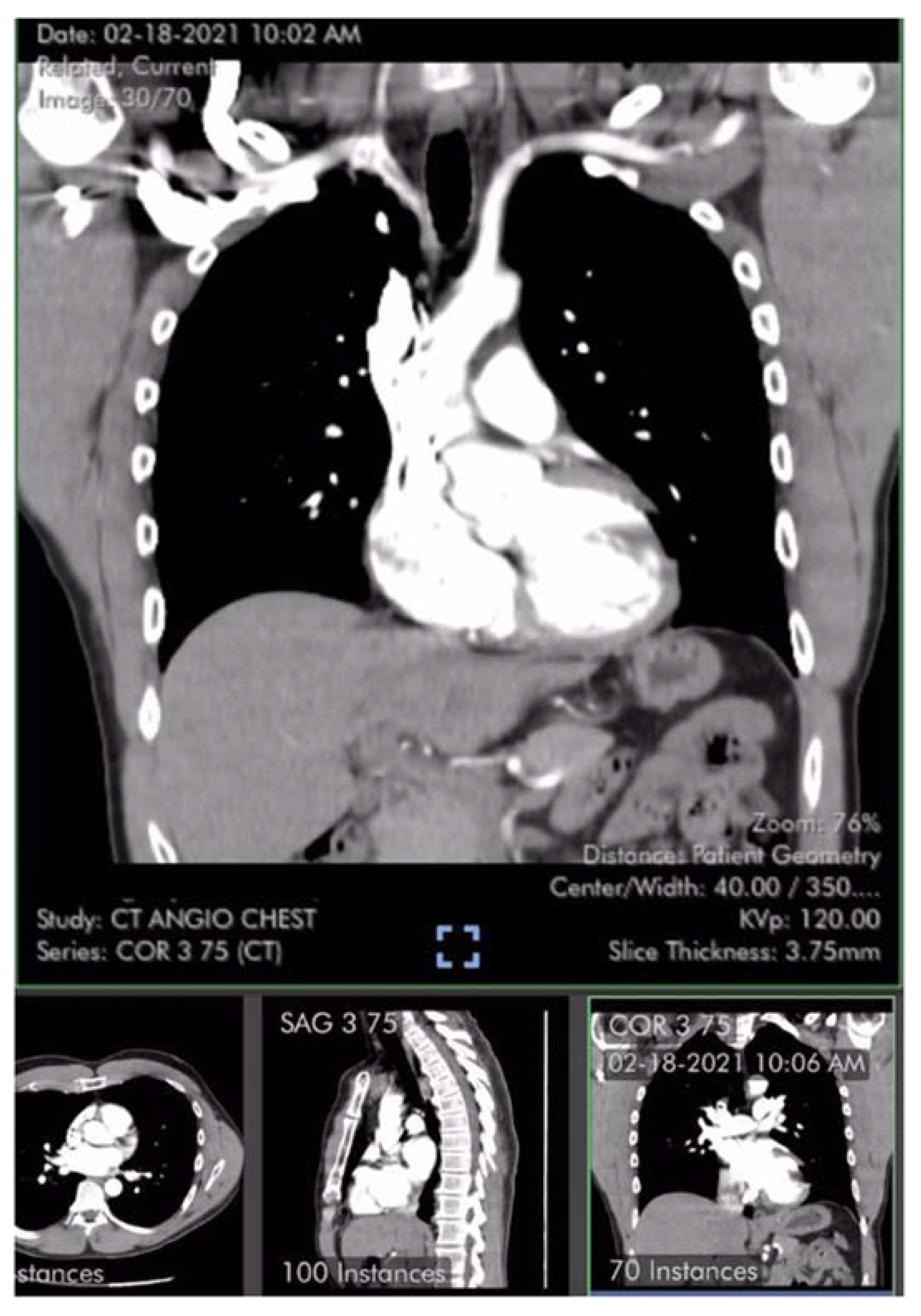

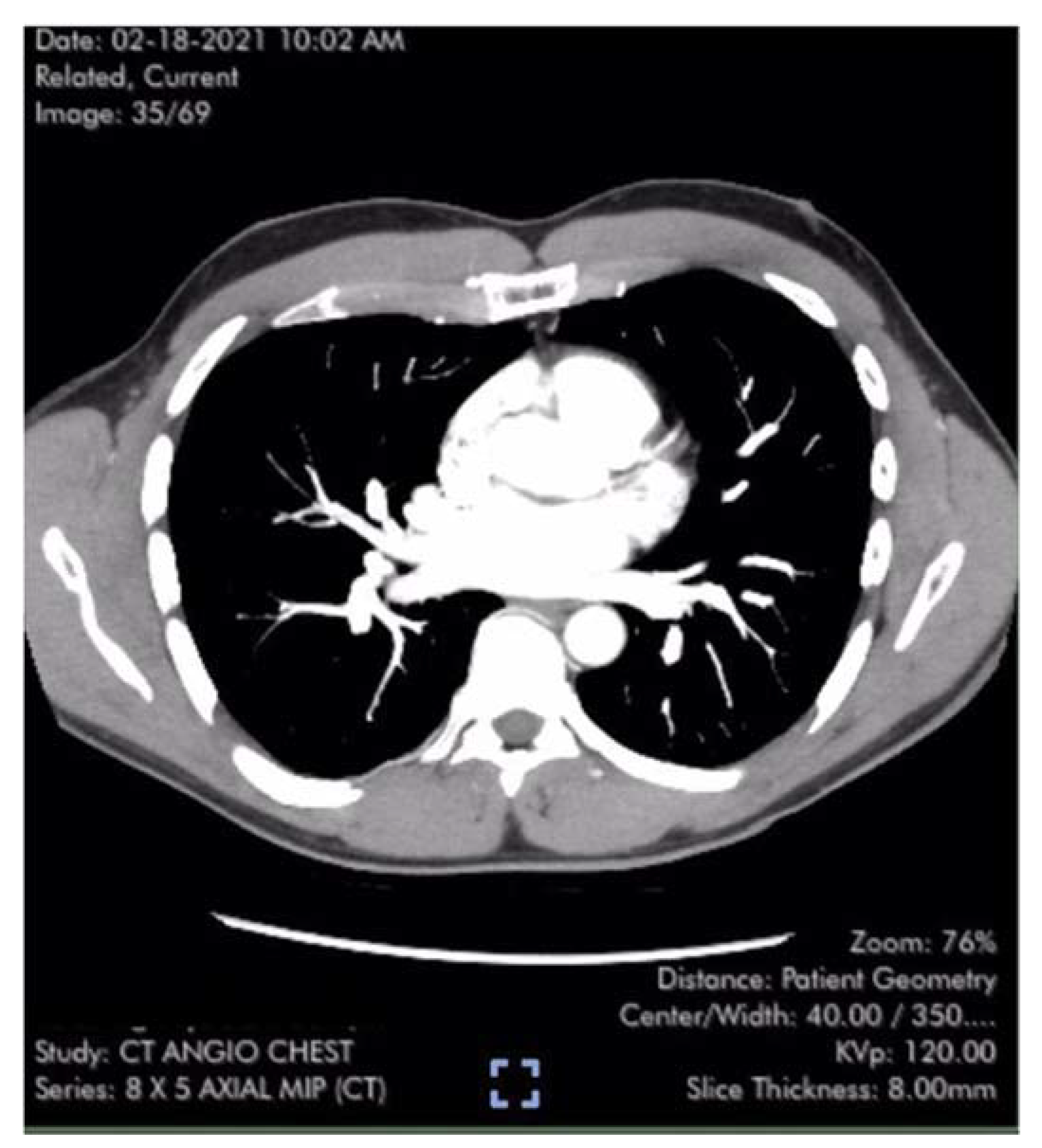

Table 1). Laboratory studies including brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) 22 pg/ml (reference range <900 pg/ml) were unremarkable except for elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and hematocrit of 50%. Pulmonary computer tomography (CT) angiogram with 3D reconstruction of the PA tree was normal without evidence of pulmonary clots (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Patient subsequently developed 15 lbs of fluid gain and generalized swelling, neck pressure, headaches and a feeling of “being hung upside down” consistent with jugular vein distention (JVD) and cerebral venous congestion. The resting oxygen saturation (SpO

2) was 92% and there was new onset systolic and diastolic arterial hypertension. Symptoms and chest pressure occurred at rest and were exacerbated by exertion. Exercise and functional limitations were consistent with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class 3-4. Serial echocardiograms showed no worsening of RVSP and continued normal RV function (

Table 1). Symptoms and exercise tolerance improved to NYHA class 1-2 over one year. Fluid weight gain, swelling, tachycardia and arterial hypertension resolved and the resting SpO2 increased to 98-100%. Flu-like symptoms and fatigue diminished but did not disappear. RVSP remained elevated and essentially unchanged by follow up echocardiography (

Table 1).

Case #2 is a previously healthy and active 56-year-old male, BMI 25, non-smoker, with a history of spontaneous deep venous thrombosis (DVT) on two occasions resolved with courses of anticoagulation without symptoms of pulmonary emboli. Hematologic investigation identified no clotting abnormalities. In 2005, an incidental isolated left superior vena cava was suspected by an otherwise normal transthoracic echocardiogram and confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patient completed the primary series of Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) in April 2021. Twelve days after the second dose, patient experienced sudden onset fatigue, flu-like symptoms and dyspnea on exertion. COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was negative. Exercise tolerance was consistent with NYHA Class 2. Patient sought medical attention two weeks later, but a stress echocardiogram and CT pulmonary angiography were not performed until almost 4 months after vaccination. The stress echocardiogram revealed normal left ventricular function, ejection fraction (EF) 60%, ventricular ectopy and mild right-sided chamber enlargement. No right-sided pressures were measured. Pulmonary CT angiogram with 3D reconstruction revealed mosaic attenuation of lung parenchyma with relative pruning of distal pulmonary vessels and mild enlargement of the PA without evidence of pulmonary emboli [

8]. A Ventilation Perfusion (V/Q) scan was interpreted as near normal and very low probability for pulmonary emboli. Despite the negative studies, anti-coagulation with rivaroxaban was started out of an abundance of caution due to patient’s distant history of DVT. A complete echocardiogram performed 5 months after vaccination measured a 2.82 m/s TR jet and calculated RVSP of 40 mm Hg, suggesting a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. Follow up echocardiography three months later measured a maximal TR velocity (TRV

max) of 3.22 m/s and estimated RVSP of 46 mmHg. Subsequent right heart catheterization confirmed the diagnosis with directly measured systolic and diastolic PA pressures (PAP) of 44/18 mm Hg (mean 28 mm Hg) and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) calculated at 3.6 Woods units. An endothelin receptor antagonist was prescribed and then a phosphodiesterase inhibitor. Fifteen months after vaccination, patient’s exercise tolerance remained unchanged and consistent with NYHA Class 2 and RVSP remained elevated at 49 mm Hg estimated by a TRV

max of 3.22 m/s. Patient’s course was complicated by transient episodes of new onset atrial fibrillation. BNP remained in normal range at 99 pg/ml. Subsequent Cardiac MRI revealed a mildly enlarged right ventricle with normal systolic function and normal main PA. A pulmonary hypertension screening panel by Invitae Genomics was negative for twelve genetic predisposition markers.

3. Discussion

We believe these are the first reported cases of sudden onset pulmonary hypertension in the absence of pulmonary emboli and representing a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine as a possible primary cause of pulmonary hypertension. The timing 2-3 weeks after the second dose and flu-like symptoms suggests an immune-mediated mechanism.

While the definition of pulmonary hypertension is precise, the gravity of the diagnosis is difficult to convey. Even “mild” pulmonary hypertension is considered incurable. It is usually progressive and, for many, a terminal diagnosis. Pulmonary hypertension is best understood as a restriction in blood flow through the lung from the right heart to left. Delivery of blood and oxygen is decreased to all organs, including the heart itself. This is especially so with exertion, as the right heart strains while the left ventricle remains underfilled and cannot increase cardiac output to meet metabolic demand. This is why pulmonary hypertension usually presents clinically and is experienced by the patient as shortness of breath with exertion and often right parasternal chest pressure. PAP is the product of cardiac output multiplied by PVR. With damage to and loss of functional pulmonary vasculature, PAP rises along with PVR for any given cardiac output. The right ventricle is very sensitive to the increasing PAP (afterload) with diminished stroke volume and cardiac output, increased energy consumption, and compromised blood flow to the right ventricle [

9,

10].

The time course of the onset of pulmonary hypertension is of critical importance. In almost all etiologies, the onset of pulmonary hypertension is gradual, with an insidious onset of fatigue and dyspnea on exertion as cardiac output falls. The right ventricle has time to hypertrophy and adapt, thus minimizing symptoms for the degree of pulmonary hypertension. As the symptoms are at first subtle, the diagnosis is often delayed. How much abrupt increase in PA pressure the right ventricle can tolerate is not precisely defined, though it may be inferred from two clinical scenarios in which this occurs: loss of pulmonary vasculature with surgical lung resection and occlusion of vasculature with pulmonary emboli. The pulmonary vasculature exists in such abundance that even removal of an entire lung with an immediate increase in PAP is highly survivable. This represents a loss of 45% of the vasculature for removal of the smaller left lung and 55% for the larger right. Peak systolic pulmonary pressure increased on average to 36 mmHg by echocardiography after a left pneumonectomy and 48 mmHg after a right. Thus, an entire lung can be removed and the diagnostic threshold for pulmonary hypertension may not be reached, or minimally so [

11]. It stands to reason that perhaps 50% or more of the pulmonary vasculature was acutely compromised in the cases we present. This approximates the diagnostic threshold for mild pulmonary hypertension by echocardiography and yet represents profound organ damage.

Pulmonary hypertension is not symptomatically mild when it occurs abruptly with massive pulmonary emboli. The right ventricle has no time to adapt. It poorly tolerates the increased afterload of a sudden increase in pulmonary pressure with precipitous drops in stroke volume and cardiac output [

12]. Patients describe chest pressure, feelings of “impending doom” and frequently die. In the setting of acute pulmonary emboli, PA pressures only begin to rise when 1⁄3 of the pulmonary is vasculature is compromised. PA pressures (and mortality) increase with occlusion of up to about 2⁄3 of PA, as measured by angiography. A mean PAP of 40 mmHg and systolic of 60 mmHg is probably the very upper limit a previously normal right ventricle can pump, and then only for a short time [

13]. Compromise of more than 2⁄3 of the pulmonary vasculature is likely fatal.

Traditionally, direct measurement of PAP by right heart catheterization is required for formal diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. The first patient did not confirm the diagnosis by right heart catheterization, but a false positive result is unlikely. Echocardiography provides an estimate of peak and mean PA pressures derived from the calculated RVSP with reasonable correlation to direct invasive measurement by right heart catheterization. While false positives and negatives are possible both with overestimation and underestimation of pressures, the positive predictive value for pulmonary hypertension with a TRV

max of > 3.0 m/s is 90% [

14,

15,

16].

The clinical improvement in the case without resolution of pulmonary hypertension likely represents right ventricular adaptation. The patient’s exercise capacity returned to above 10 METs, with a 6 min walk test >500m, a low BNP and counterintuitively a high LDL cholesterol, which are predictors of increased survival with pulmonary hypertension [

17,

18,

19,

20].

4. Conclusions

We reported two cases of acute pulmonary hypertension after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. There may be many other cases of significant pulmonary vasculature damage after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination, in which echocardiography still would be normal or sub-diagnostic and thus elude diagnosis. Further investigations of the relationships between the spike protein and pulmonary hypertension are warranted [

21].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and Y.S.; methodology, R.S.; software, R.S.; validation, R.S., N.S. and Y.S.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, R.S., N.S. and Y.S.; resources, R.S. and Y.S.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.; writing—review and editing, R.S., N.S. and Y.S.; visualization, R.S., N.S. and Y.S.; supervision, R.S. and Y.S.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers R21AG073919 (to Y.J.S.) and R03AG071596 (to Y.J.S.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written consent has been obtained from both patients for the use of data presented in this case report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Suzuki, Y.J.; Nikolaienko, S.I.; Dibrova, V.A.; Dibrova, Y.V.; Vasylyk, V.M.; Novikov, M.Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-mediated cell signaling in lung vascular cells. Vascul Pharmacol. 2021, 137, 106823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktaviono, Y.H.; Mulia, E.P.B.; Luke, K.; Nugraha, D.; Maghfirah, I.; Subagjo, A. Right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension in COVID-19: a meta-analysis of prevalence and its association with clinical outcome. Arch Med Sci. 2022, 18, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norderfeldt, J.; Liliequist, A.; Frostell, C.; Adding, C.; Agvald, P.; Eriksson, M.; et al. Acute pulmonary hypertension and short-term outcomes in severe Covid-19 patients needing intensive care. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021, 65, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, R.; Coppi, F.; Monopoli, D.E.; Sgura, F.A.; Arrotti, S.; Boriani, G. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and right ventricular systolic dysfunction in COVID-19 survivors. Cardiol J. 2022, 29, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.J.; Suzuki, Y.J. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and lung vascular cells. J Respir. 2021, 1, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.J.E.; Wachsmann, J.; Chamarthy, M.R.; Panjikaran, L.; Tanabe, Y.; Rajiah, P. Imaging of acute pulmonary embolism: an update. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2018, 8, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, R.S.; Schwartz, L.M.; Woloshin, S. When a test is too good: how CT pulmonary angiograms find pulmonary emboli that do not need to be found. BMJ 2013, 347, f3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synn, A.J.; Li, W.; Estépar, R.S.J.; Washko, G.R.; O’Connor, G.T.; Tsao, C.W.; et al. Pulmonary vascular pruning on computed tomography and risk of death in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021, 203, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahuja, M.; Burkhoff, D. Right ventricular afterload sensitivity has been on my mind. Circ Heart Fail. 2019, 12, e006345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, Y.C.; Perez-Johnston, R.; Bryce, E.B.; Homayoon, B.; Santos-Martin, E.G. Pathophysiology of right ventricular failure in acute pulmonary embolism and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a pictorial essay for the interventional radiologist. Insights Imaging. 2019, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroulis, C.N.; Kotoulas, C.S.; Kakouros, S.; Evangelatos, G.; Chassapis, C.; Konstantinou, M.; et al. Study on the late effect of pneumonectomy on right heart pressures using Doppler echocardiography. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004, 26, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayer, G.; Semigran, M.J. Acute and chronic right ventricular failure. Heart Failure. 2017, 22, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, K.M.; Sasahara, A.A. The hemodynamic response to pulmonary embolism in patients without prior cardiopulmonary disease. Am J Cardiol. 1971, 28, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkateshvaran, A.; Seidova, N.; Tureli, H.O.; Kjellström, B.; Lund, L.H.; Tossavainen, E.; et al. Accuracy of echocardiographic estimates of pulmonary artery pressures in pulmonary hypertension: insights from the KARUM hemodynamic database. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021, 37, 2637–2645. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, P.J.; Seward, J.B.; Chan, K.L.; Fyfe, D.A.; Hagler, D.J.; Mair, D.D.; et al. Continuous wave Doppler determination of right ventricular pressure: a simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study in 127 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985, 6, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, S.; Walker, S.; Loudon, B.L.; Gollop, N.D.; Wilson, A.M.; Lowery, C.; et al. Assessment of pulmonary artery pressure by echocardiography - A comprehensive review. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2016, 12, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.O.S.; Ramos, R.P.; Oliveira, R.K.F.; Cepêda, A.; Vieira, E.B.; Ivanaga, I.T.; et al. Prognostic value of six-minute walk distance at a South American pulmonary hypertension referral center. Pulm Circ. 2020, 10, 2045894019888422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casserly, B.; Klinger, J.R. Brain natriuretic peptide in pulmonary arterial hypertension: biomarker and potential therapeutic agent. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2009, 3, 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Frantz, R.P.; Farber, H.W.; Badesch, D.B.; Elliott, C.G.; Frost, A.E.; McGoon, M.D.; et al. Baseline and serial brain natriuretic peptide level predicts 5-year overall survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Data from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2018, 154, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeć, G.; Waligóra, M.; Tyrka, A.; Jonas, K.; Pencina, M.J.; Zdrojewski, T.; et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 41650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.J.; Gychka, S.G. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Elicits Cell Signaling in Human Host Cells: Implications for Possible Consequences of COVID-19 Vaccines. Vaccines. 2021, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).