Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

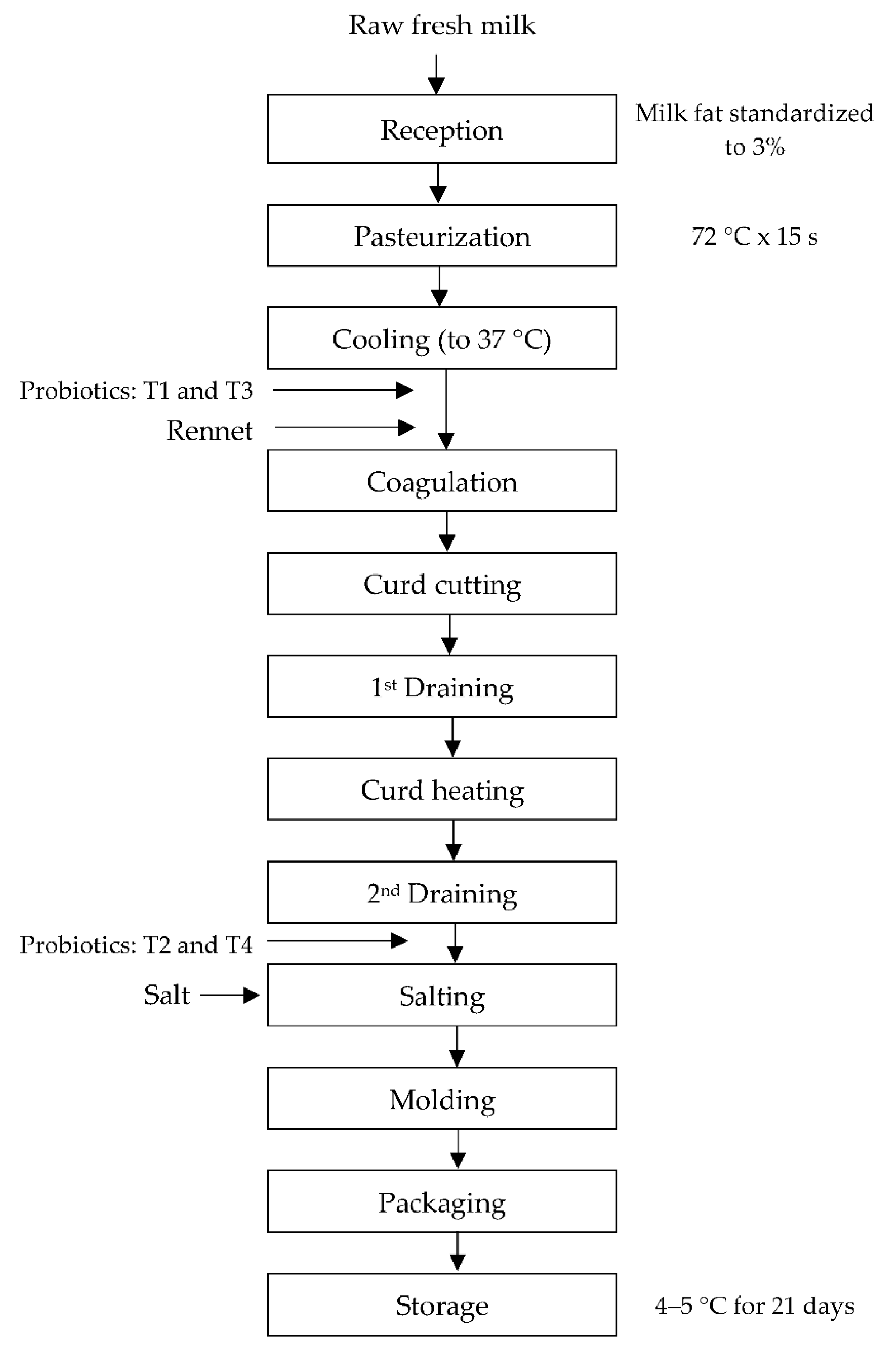

2.2. Probiotic Fresh Cheese Production

2.3. Physicochemical Analysis of Milk

2.4. Physicochemical Analysis of Cheese

2.5. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA)

2.6. Lactic Acid Bacteria Count

2.6.1. Media Preparation

2.6.2. Sample Preparation and Dilutions

2.7. Sensory Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Milk

3.2. Viability of Lactic acid Bacteria (LAB) during Storage

3.3. Acidity Evaluation

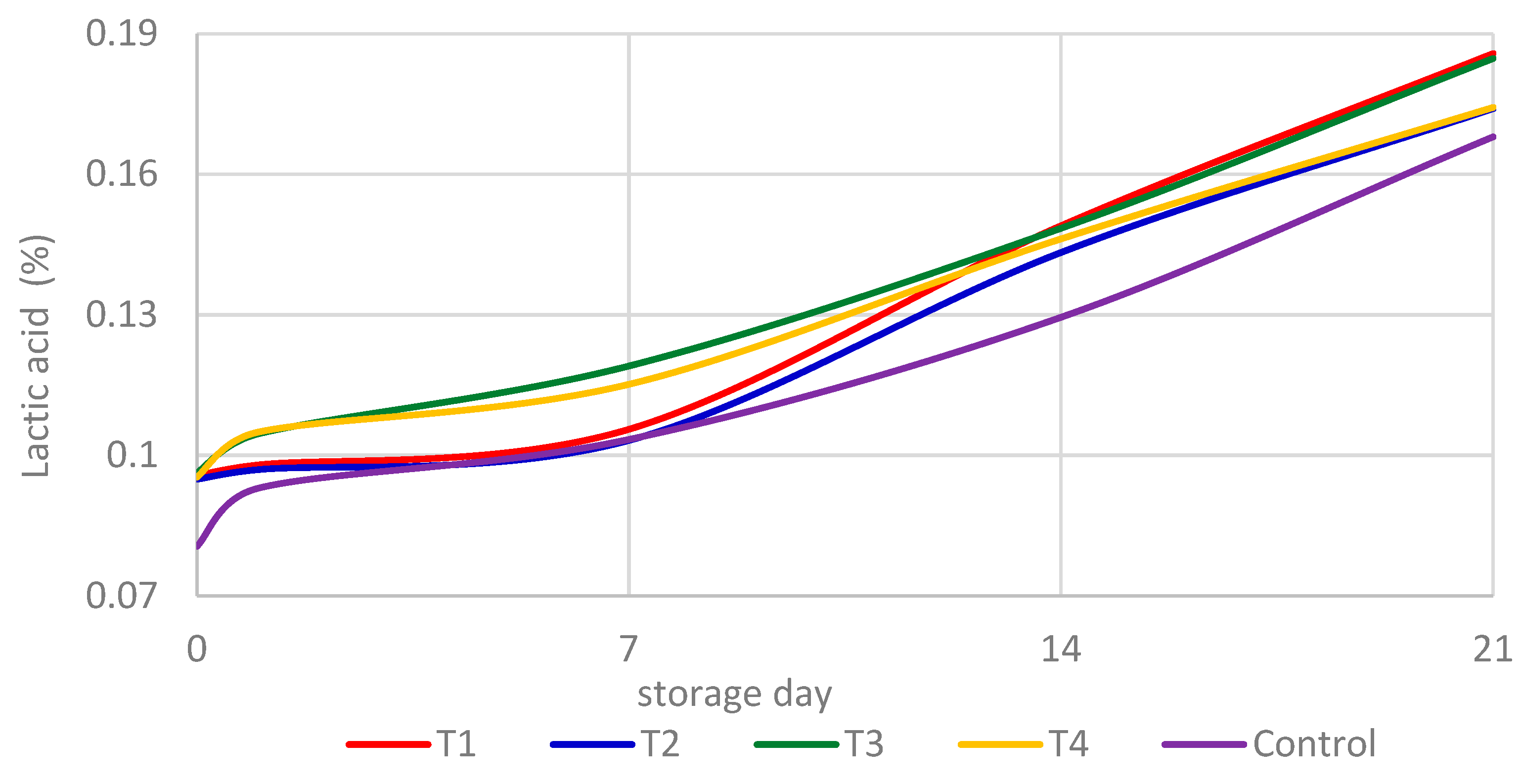

3.4. pH Evaluation

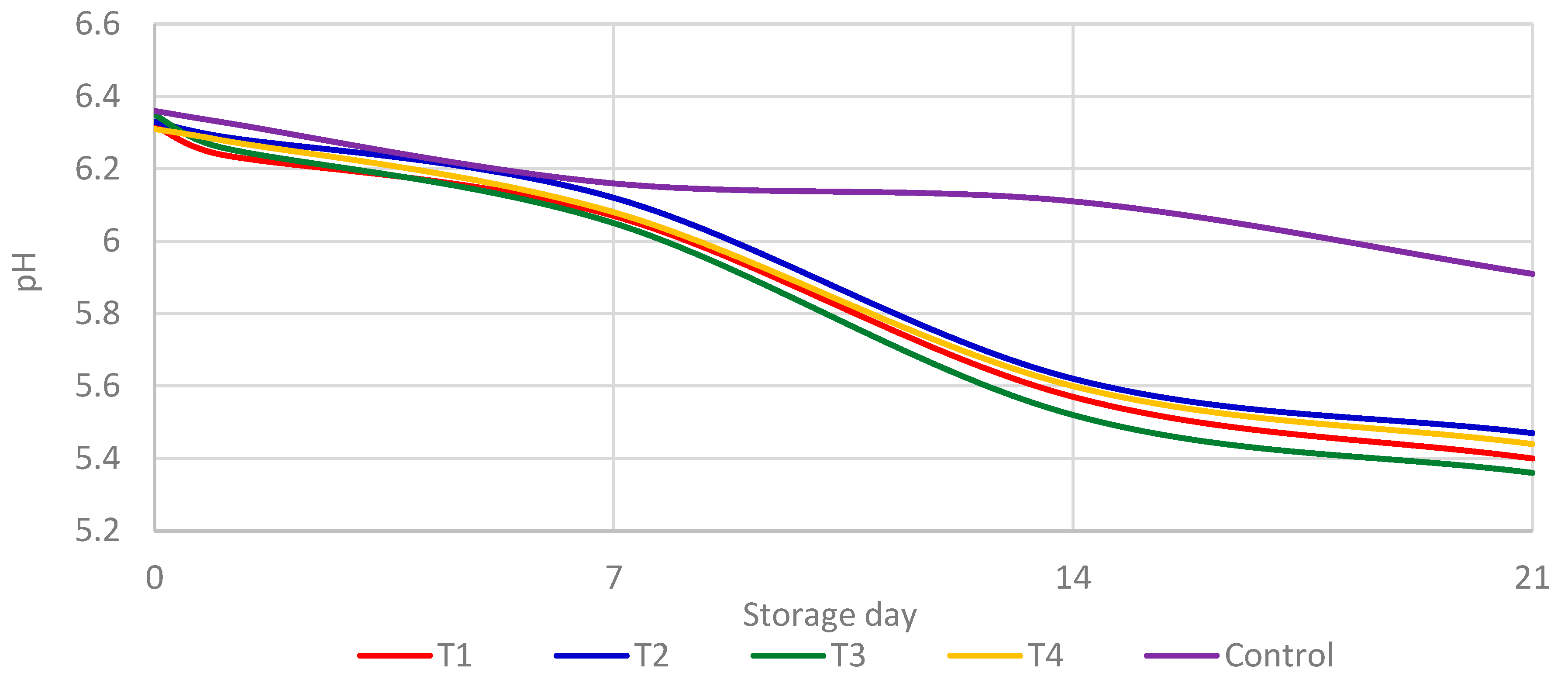

3.5. Syneresis

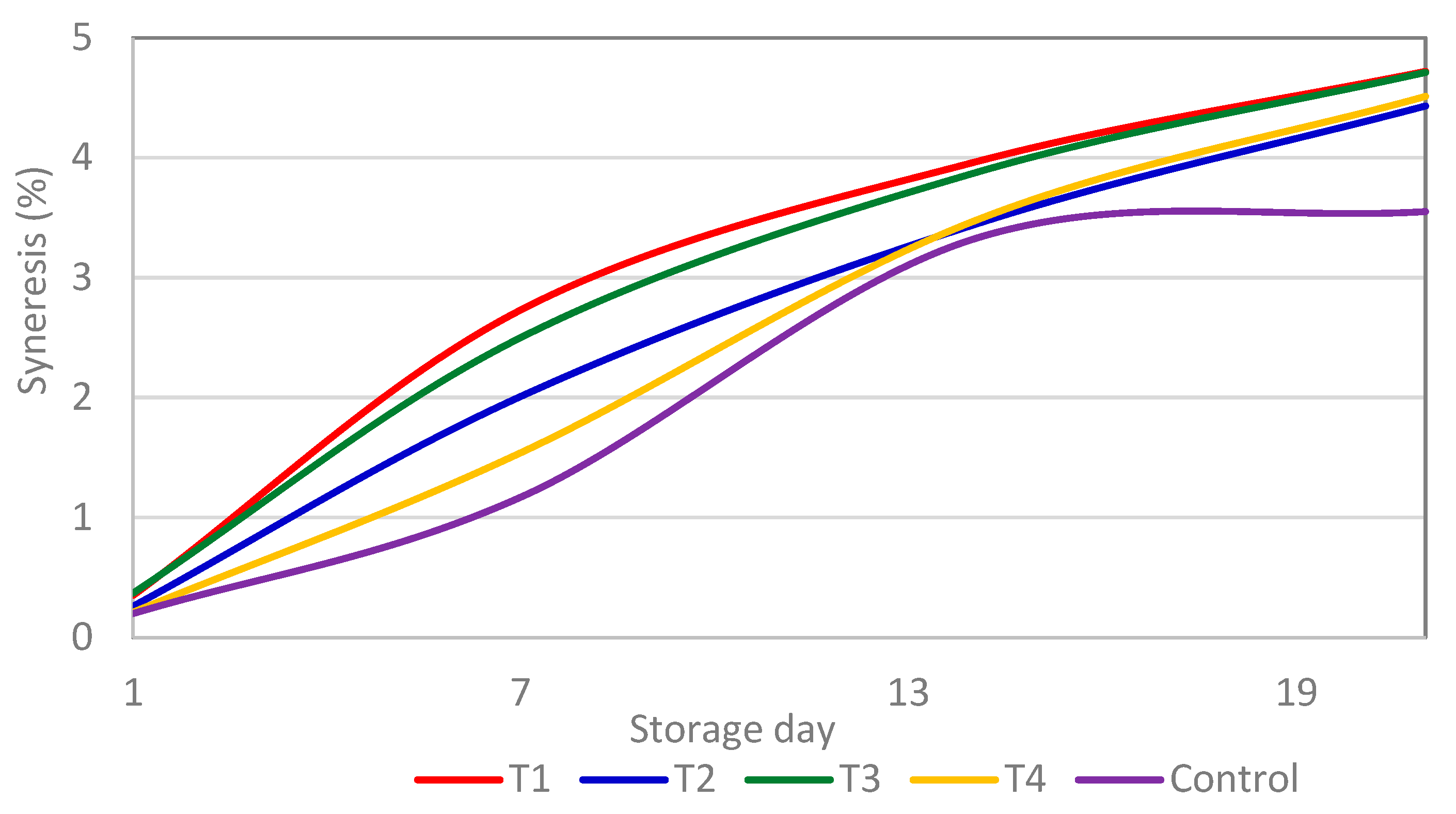

3.6. TPA

3.7. Sensory Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blaiotta, G.; Murru, N.; Di Cerbo, A.; Succi, M.; Coppola, R.; Aponte, M. Commercially standardized process for probiotic “Itálico” cheese production. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerlikaya, O.; Ozer, E. Production of probiotic fresh White cheese using co-culture with Streptococcus thermophilus. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 34, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex Alimentarius, General standard for cheese CXS 283–1978, FAO, Rome, Italy, 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B283-1978%252FCXS_283e.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- de Andrade, D.P. , Bastos, S.C., Ramos, C.L., Simões, L.A., Fernandes, N.D.A.T., Botrel, D.A., Magnani, M., Schwan, R.F. and Dias, D.R. Microencapsulation of presumptive probiotic bacteria Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CCMA 0359: Technology and potential application in cream cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2023, 143, 105669. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, R.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Da Cruz, A.G. Viability of probiotic microorganisms in cheese during production and storage: a review. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2011, 91, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.M.; Tornadijo, M.E.; Fresno, J.M.; Sandoval, H. Biocheese: a food probiotic carrier. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 723056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningtyas, D.W.; Bhandari, B.; Bansal, N.; Prakash, S. The viability of probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus (non-encapsulated and encapsulated) in functional reduced-fat cream cheese and its textural properties during storage. Food Control 2019, 100, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L. The addition of probiotic promotes the release of ACE-I peptide of Cheddar cheese: Peptide profile and molecular docking. Int. Dairy J. 2023, 137, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anihouvi, E.S.; Kesenkaş, H. Wagashi cheese: Probiotic bacteria incorporation and significance on microbiological, physicochemical, functional and sensory properties during storage. LWT 2022, 155, 112933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, I.A.; Iraporda, C.; Manrique, G.D.; Genovese, D.B. Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.) inulin as a suitable bioactive ingredient to incorporate into spreadable ricotta cheese for the delivery of probiotic. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2022, 28, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, O. The effects of probiotic cultures on the organic acid content, texture profile and sensory attributes of Tulum cheese. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2019, 72, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buriti, F.C.; Da Rocha, J.S.; Saad, S.M. Incorporation of Lactobacillus acidophilus in Minas fresh cheese and its implications for textural and sensorial properties during storage. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.L.; Richards, N.S.; Mattanna, P.; Andrade, D.F.; S Rezer, A.P.; Milani, L.I.; Cruz, A.G.; Faria, J.A. Cream cheese as a symbiotic food carrier using Bifidobacterium animalis Bb-12 and Lactobacillus acidophilus La-5 and inulin. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2013, 66, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basturk, A.; Isik, İ.; Atalay, A.; Yılmaz, A. Investigation of the efficacy of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in infants with cow’s milk protein allergy: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Z.; Zou, M.; Bei, T.; Zhang, N.; Li, D.; Wang, M.; Li, C.; Tian, H. Effect of fructooligosaccharides on the colonization of Lactobacillus rhamnosus AS 1.2466 T in the gut of mice. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.A.; Braga, S.P.; Cruz, A.G.; Cadena, R.S.; Lollo, P.C.B.; Carvalho, C.; Amaya-Farfán, J.; Faria, J.A.F.; Bolini, H.M.A. Effect of the inoculation level of Lactobacillus acidophilus in probiotic cheese on the physicochemical features and sensory performance compared with commercial cheeses. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 4777–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; AOAC Intl.: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Dairy Federation (IDF 150); International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Yogurt - determination of titratable acidity; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- International Dairy Federation (IDF 13C). Evaporated milk and sweetened condensed milk - determination of fat content - Röse Gottlieb. Reference method; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- International Dairy Federation (IDF standard 20B); International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Determination of the nitrogen (Kjeldahl method) and calculation of the crude protein content; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- International Dairy Federation (IDF 21B). Milk, cream and evaporated milk - determination of total solids content. Reference method; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pearse, M.J.; Mackinlay, A.G. Biochemical aspects of syneresis: a review. J. Dairy Sci. 1989, 72, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunick, M.H.; Van Hekken, D.L. Rheology and texture of commercial queso fresco cheeses made from raw and pasteurized milk. J. Food. Qual. 2010, 33, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association (APHA). Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods; Salfinger, Y., Tortorello, M.L., Eds.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Instituto Nacional de Calidad (INACAL); Norma Técnica Peruana (NTP 202.001). Milk and milk products - Raw milk - Requirements, INACAL: Lima, Peru, 2016.

- Brisson, G.; Singh, H. Milk Composition, Physical and Processing Characteristics. In Manufacturing Yogurt and Fermented Milks, 2nd ed.; Chandan, R.C., Kilara, A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Provencio, D.; Llopis, M.; Antolín, M.; De Torres, I.; Guarner, F.; Pérez-Martínez, G.; Monedero, V. Adhesion properties of Lactobacillus casei strains to resected intestinal fragments and components of the extracellular matrix. Arch. Microbiol. 2009, 191, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Kailasapathy, K.; Tran, L. Viability of commercial probiotic cultures (L. acidophilus, Bifidobacterium spp., L. casei, L. paracasei and L. rhamnosus) in cheddar cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 108, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, G.E.; Bouchier, P.; O’Sullivan, E.; Kelly, J.; Collins, J.K.; Fitzgerald, G.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. A spray-dried culture for probiotic Cheddar cheese manufacture. Int. Dairy J. 2002, 12, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.M.S.; Grisi, C.V.B.; de Souza Silva, G.; Neto, J.H.P.L.; de Medeiros, L.L.; dos Santos, K.M.O.; Cardarelli, H.R. Use of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CNPC 003 for the manufacture of functional skimmed fresh cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2023, 141, 105628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, A.J.; Hansen, C.L.; McMahon, D.J. Effect of pH on the chemical composition and structure-function relationships of Cheddar cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 2751–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyoti, B.D.; Suresh, A.K.; Venkatesh, K.V. Diacetyl production and growth of Lactobacillus rhamnosus on multiple substrates. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 19, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra Huertas, R.A. Review lactic acid bacteria: functional role in the foods. Rev. Bio. Agro. 2010, 8, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, M.C.; Malcata, F.X.; Silva, C.C.G. Lactic acid bacteria in raw-milk cheeses: From starter cultures to probiotic functions. Foods 2022, 11, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Density (g/mL) | 1.03 ± 0.01 |

| Acidity (% lactic acid) | 0.15 ± 0.01 |

| pH | 6.71 ± 0.08 |

| Total solids (%) | 12.06 ± 0.03 |

| Alcohol test (74% v/v) | Negative |

| Fat content (g/100g) | 3.02 ± 0.02 |

| Protein content (g/100g) | 3.54 ± 0.01 |

| Storage (d) |

L. acidophilus | L. rhamnosus | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |||

| 0 | 4.66 ± 0.09b | 4.56 ± 0.18b | 5.63 ± 0.07a | 4.48 ± 0.41b | 3.26 ± 0.17c | |

| 1 | 4.79 ± 0.01b | 4.40 ± 0.26b | 6.01 ± 0.26a | 4.41 ± 0.35b | 2.86 ± 0.13c | |

| 7 | 4.93 ± 0.05b | 4.86 ± 0.27b | 6.63 ± 0.20a | 5.08 ± 0.28b | 3.31 ± 0.51c | |

| 14 | 4.73 ± 0.12b | 4.75 ± 0.20b | 6.63 ± 0.04a | 4.78 ± 0.22b | 3.96 ± 0.88c | |

| 21 | 4.38 ± 0.04b | 4.63 ± 0.34b | 6.25 ± 0.07a | 4.50 ± 0.05b | 3.47 ± 1.09c | |

| Treatment | Hardness (N) |

Adhesiveness (N-mm) | Cohesiveness | Springiness | Gumminess (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 14.02 ± 2.06 | 56.94 ± 0.07a | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.09 | 3.31 ± 1.12 |

| T2 | 13.46 ± 1.82 | 185.32 ± 0.07e | 0.22 ± 0.12 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 4.52 ± 1.84 |

| T3 | 12.48 ± 3.19 | 69.36 ± 0.08b | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.07 | 4.26 ± 1.03 |

| T4 | 13.33 ± 1.29 | 108.48 ± 0.08d | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.10 | 4.24 ± 1.52 |

| Control | 16.62 ± 1.45 | 80.51 ± 0.05c | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 6.36 ± 0.70 |

| Treatment | Score |

|---|---|

| L. acidophilus inoculated before renneting (T1) | 171 |

| L. acidophilus inoculated before salting (T2) | 93 |

| L. rhamnosus inoculated before renneting (T3) | 199 |

| L. rhamnosus inoculated before salting (T4) | 78 |

| Control | 212 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).