Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalga Exposure

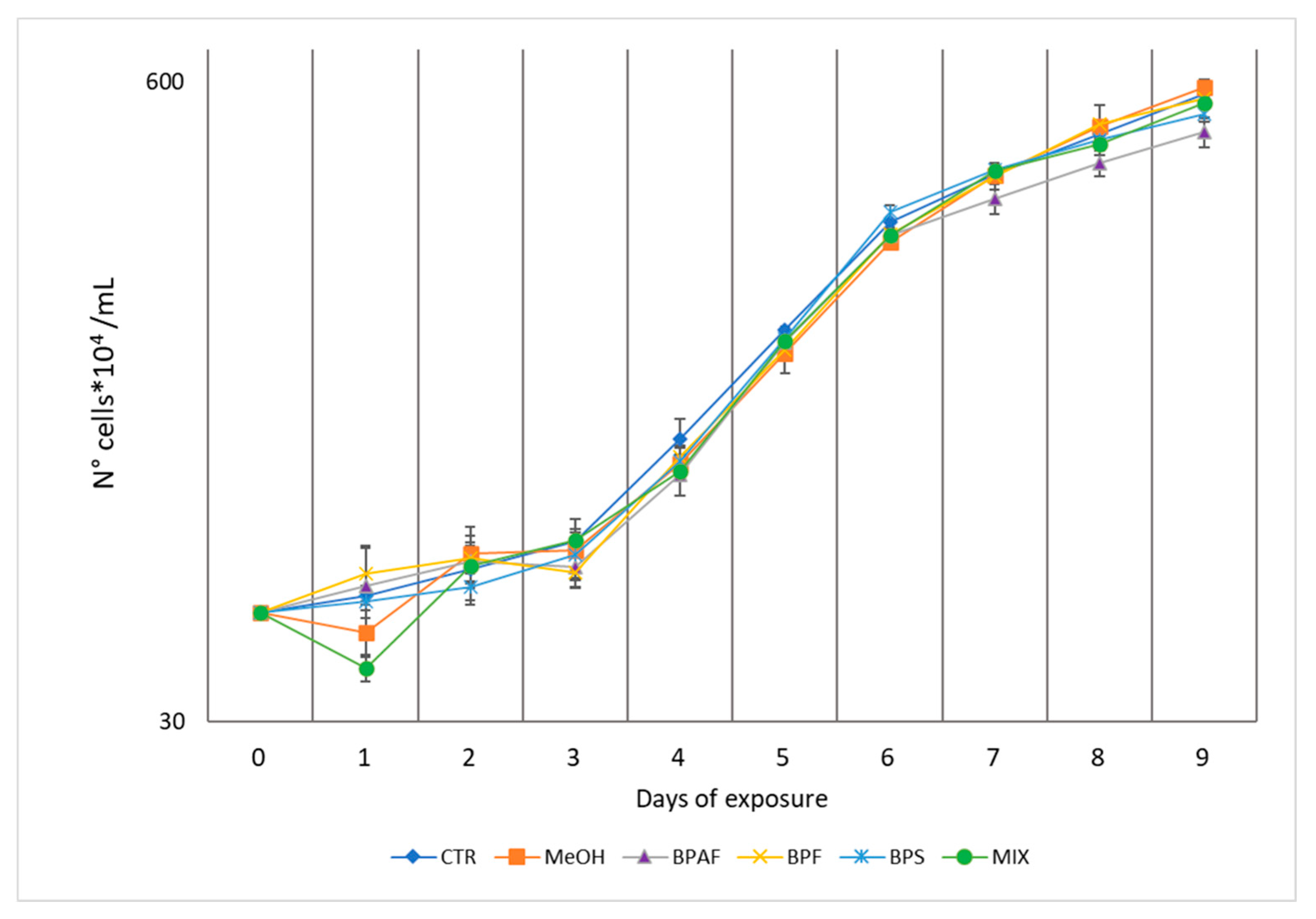

2.2. Growth Curve

2.3. Biochemical Assays

2.4. Statistical Analysis

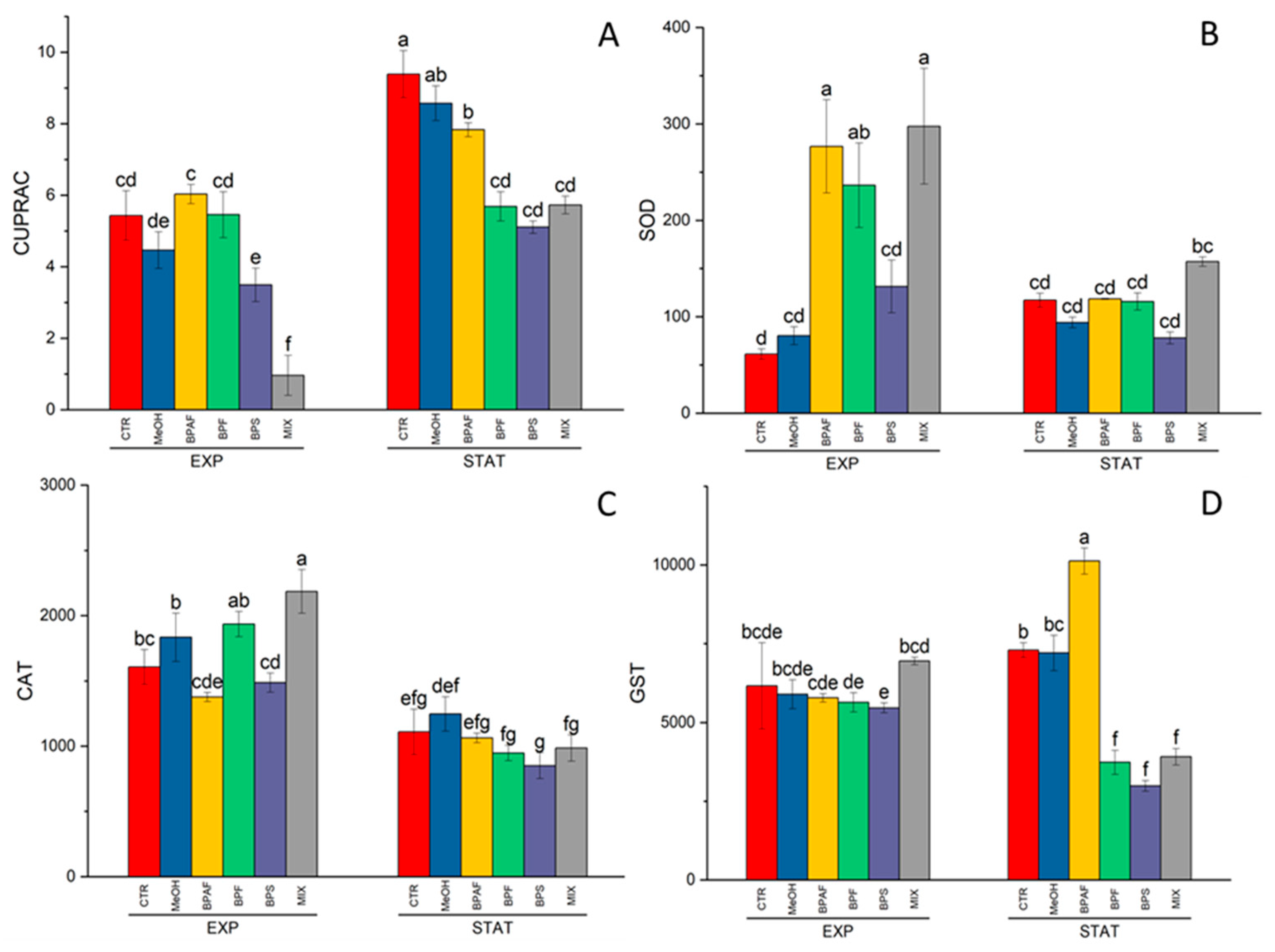

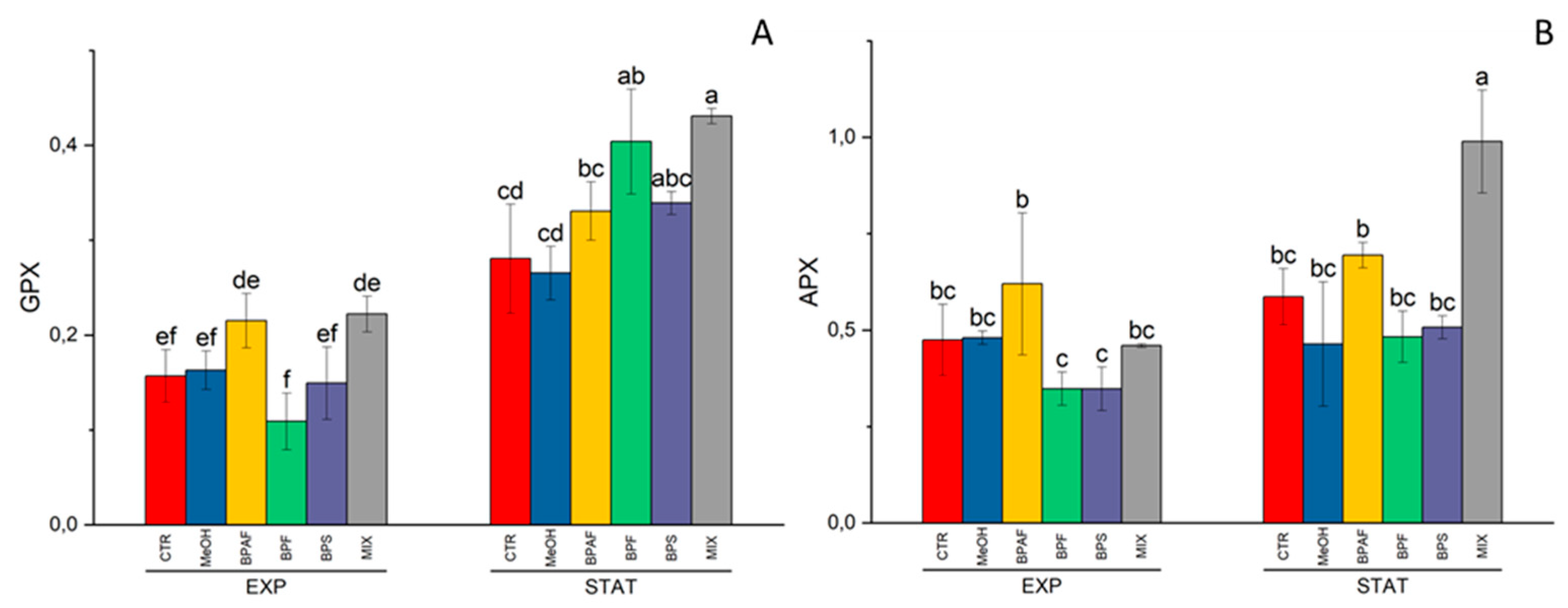

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth and Cell Size

4.2. Biomarkers Response

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Hauser, R.; Marcus, M.; Olea, N.; Welshons, W.V. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA). Reprod Toxicol. 2007, 24, 139–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Commission regulation 2016/2235 of 12 December 2016 amending annex XVII to regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European parliament and of the council concerning the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals (REACH) as regards bisphenol A. Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L337, 3–5. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kannan, K.; Tan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Y.L.; Wu, Y.; Widelka, M. Bisphenol analogues other than BPA: Environmental occurrence, human exposure, and toxicity—A review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.; Ikhlas, S.; Ahmad, M. Occurrence, toxicity and endocrine disrupting potential of Bisphenol-B and Bisphenol-F: A mini-review. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 312, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA; FitzGerald, R.; Van Loveren, H.; Civitella, C.; Castoldi, A.F.; Giovanni Bernasconi, G. Assessment of New Information on Bisphenol S (BPS) Submitted in Response to the Decision under REACH Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006; EFSA Supporting Publication; European Food Safety Authority (EFSA): Parma, Italy, 2020; p. 39.

- ECHA. Inclusion of BPA as a Substance of Very High Concern (Reason for Inclusion: Endocrine Disrupting Properties—Article 57f Environment) in the Candidate List for Eventual Inclusion in Annex XIV; Decision of the European Chemicals Agency; European Chemicals Agency: Helsinki, Finland, 2018.

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Yan, X.; Liao, C.; Jiang, G. Occurrence, fate and risk assessment of BPA and its substituents in wastewater treatment plant: A review. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECHA. Bisphenol AF, Substance Infocard. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/substance-information/-/substanceinfo/100.014.579 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Frankowski, R.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Smułek, W.; Grześkowiak, T. Removal of bisphenol A and its potential substitutes by biodegradation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 191, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission of the European Communities. Technical Guidance Document in Support of Commission Directive 93/67/EEC on Risk Assessment for New Notified Substances and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 on Risk Assessment. Office for Existing Substances. Part II; Environmental Risk Assessment. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg,1996.

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; He, Y.; Xiao, H.; Fang, D.; Chen, C. Toxic effects of bisphenol A and bisphenol S on Chlorella pyrenoidosa under single and combined action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Ahn, H.J.; Kurade, M.B.; Ahn, Y.; Park, Y.K.; Khan, M.A.; Salama, E.S.; Li, X.; Jeon, B.H. Fate of five bisphenol derivatives in Chlamydomonas mexicana: Toxicity, removal, biotransformation and microalgal metabolism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tišler, T.; Krel, A.; Gerželj, U.; Erjavec, B.; Dolenc, M.S.; Pintar, A. Hazard identification and risk characterization of bisphenols A, F and AF to aquatic organisms. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 212, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Li, W.; Yang, M.; Yang, B.; Li, J. Toxicity and biotransformation of bisphenol S in freshwater green alga Chlorella vulgaris. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 747, 141144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarny-Krzymińska, K.; Krawczyk, B.; Szczukocki, D. Toxicity of bisphenol A and its structural congeners to microalgae Chlorella vulgaris and Desmodesmus armatus. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 34, 1397–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elersek, T.; Notersberg, T.; Kovačič, A.; Heath, E.; Filipič, M. The effects of bisphenol A, F and their mixture on algal and cyanobacterial growth: from additivity to antagonism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 3445–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Yang, X.; Liu, H. Insight Into The Aquatic Toxicity And Ecological Risk of Bisphenol B, And Comparison With That of Bisphenol A. 22 November 2021, available at Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Fabrello, J.; Matozzo, V. Bisphenol analogs in aquatic environments and their effects on marine species—a review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. European Union Updated Risk Assessment Report. Environment Addendum of April 2008 (To be Read in Conjunction with Published EU RAR of BPA, 2003) 4,4′-ISOPROPYLIDENEDIPHENOL (Bisphenol-A) Part 1 Environment; European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for Health and Consumer Protection: Luxembourg, 2008.

- Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Shan, G.; Chen, P.; Cui, S.; Yi, S.; Zhu, L. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of emerging bisphenol analogues in aquatic organisms from Taihu Lake, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 598, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wu, L.H.; Liu, G.Q.; Shi, L.; Guo, Y. Occurrence and ecological risk assessment of eight endocrine-disrupting chemicals in urban river water and sediments of South China. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018, 75, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, E.; Yamashita, N.; Taniyasu, S.; Lam, J.; Lam, P.K.; Moon, H.B.; Jeong, Y.; Kannan, P.; Achyuthan, H.; Munuswamy, N.; et al. Bisphenol A and other bisphenol analogues including BPS and BPF in surface water samples from Japan, China, Korea and India. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 122, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Qiu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Xiong, J.; Gao, C.; Hu, S. Occurrence, distribution, bioaccumulation, and ecological risk of bisphenol analogues, parabens and their metabolites in the Pearl River Estuary, South China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 180, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillard, R.R. Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrates. In Culture of marine invertebrate animals: proceedings—1st conference on culture of marine invertebrate animals greenport, 1975, 29-60. Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Karademir, S.E. Novel total antioxidant capacity index for dietary polyphenols and vitamins C and E, using their cupric ion reducing capability in the presence of neocuproine: CUPRAC method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7970–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crapo, J.D.; McCord, J.M.; Fridovich, I. Preparation and assay of superioxide dismutases. Methods Enzymol. 1978, 53, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in Vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, I.K.; Vierheller, T.L.; Thorne, C.A. Assay of glutathione reductase in crude tissue homogenates using 5,5′-Dithiobis(2-Nitrobenzoic Acid). Anal. Biochem. 1988, 175, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habig, W.H.; Pabst, M.J.; Jakoby, W.B. Glutathione S Transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, R.A.; Burk, R.F. Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976, 71, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide Is Scavenged by Ascorbate-Specific Peroxidase in Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janknegt, P.J.; De Graaff, C.M.; Van de Poll, W.H.; Visser, R.J.; Rijstenbil, J.W.; Buma, A.G. Short-term antioxidative responses of 15 microalgae exposed to excessive irradiance including ultraviolet radiation. Eur. J. Phycol. 2009, 44, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecocci, P.; Fanó, G.; Fulle, S.; MacGarvey, U.; Shinobu, L.; Polidori, M.C.; Cherubini, A.; Vecchiet, J.; Senin, U.; Beal, M.F. Age-dependent increases in oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins in human skeletal muscle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buege, J.A.; Aust, S.D. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978, 52, 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- Damiens, G.; Gnassia-Barelli, M.; Loquès, F.; Roméo, M.; Salbert, V. Integrated biomarker response index as a useful tool for environmental assessment evaluated using transplanted mussels. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizullah, A.; Khan, S.; Gao, G.; Gao, K. The interplay between bisphenol A and algae–A review. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M'Rabet, C.; Pringault, O.; Zmerli-Triki, H.; Gharbia, H.B.; Couet, D.; Yahia, O. K. D. Impact of two plastic-derived chemicals, the Bisphenol A and the di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, exposure on the marine toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium pacificum. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 126, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveira, C.; Rodrigues, N.; Santos, F.S.; Santos, L.N.; Neves, R.A. Acute toxicity of Bisphenol A (BPA) to tropical marine and estuarine species from different trophic groups. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Hou, S.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Sun, Z.; Chen, D. Exposure to bisphenol analogues interrupts growth, proliferation, and fatty acid compositions of protozoa Tetrahymena thermophila. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 395, 122643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendra, M.; Moreno-Garrido, I.; Blasco, J. Single and multispecies microalgae toxicological tests assessing the impact of several BPA analogues used by industry. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 122073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Chen, Q.; Duan, S. Transcriptional analysis of Chlorella pyrenoidosa exposed to bisphenol A. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiong, B.; Sun, W.F.; An, S.; Lin, K.F.; Guo, M.J.; Cui, X.H. Acute and chronic toxic effects of bisphenol a on Chlorella pyrenoidosa and Scenedesmus obliquus. Environ. Toxicol. 2014, 29, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, G. Z.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Luan, T.G.; Shin, P.K.; Cheung, S.G.; Liu, Y. Toxicity of bisphenol A and its bioaccumulation and removal by a marine microalga Stephanodiscus hantzschii. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009, 72, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Tam, N. F.; Shin, P. K.; Cheung, S. G.; Luan, T. Physiological responses of the alga Cyclotella caspia to bisphenol A exposure. Bot. Mar. 2008, 51, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Fan, Z.; Xie, Y.; Fang, L.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Li, R. Transcriptome analysis of the effect of bisphenol A exposure on the growth, photosynthetic activity and risk of microcystin-LR release by Microcystis aeruginosa. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 397, 122746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ding, T.; Luo, X.; Li, J. Toxic effect of fluorene-9-bisphenol to green algae Chlorella vulgaris and its metabolic fate. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 216, 112158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Guan, Y.; Gao, Q.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Zhu, W. Cellular responses, biodegradation and bioaccumulation of endocrine disrupting chemicals in marine diatom Navicula incerta. Chemosphere 2010, 80, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ouada, S.; Ben Ali, R.; Leboulanger, C.; Zaghden, H.; Choura, S.; Ben Ouada, H.; Sayadi, S. Effect and removal of bisphenol A by two extremophilic microalgal strains (Chlorophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiefeng, L.; Xufa, M.; Yu, L.; Shenjuan, Z.; Boli, Z.; Jie, H. Effects of bisphenol A on growth, photosynthesis pigment and antioxidant system of Spirodela polyrrhiza. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology 2019, 6, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, R.; Shi, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, C.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z. The effect of bisphenol A on growth, morphology, lipid peroxidation, antioxidant enzyme activity, and PS II in Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii and Scenedesmus quadricauda. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018, 74, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).