Introduction

Cancer mass is bag of heterogeneous calls containing most sensitive clones to highly resistant stem cells. Over the decade’s enough effective therapies have been developed, latest being immunotherapy. However, two root causes, one “unmasking” and repopulation of resistant clones and second “rewiring” of inexhaustible web like pathways of immune escape mutations. In the process in significant number of patients, either in short term or long term, the tumor mass gets transformed to resistant clonal types in treatment failed patients.

Therefore, in the long term a strategy that can beat cancer cells in its own game is by empowering the innate immune network to “peep” inside through aberrant cell surface receptors constantly and eliminate at the first sign of repopulation. Thus, the potential way to eliminate caner as fatal disease is taking the leaf out of control of infectious disease and strategize a way to develop a therapeutic vaccination methodology. In vitro vaccination technology for cancer has come a long way, yet the cancer cells being the inner enemy evolving continuously, it is necessary to have in place in-vivo technique alone or supplementing the in-vitro technique to keep a watch on dynamic flow of developing mutation. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of in-situ vaccination procedures by intratumral administration of drugs. However, SBRT is the other method that has the ability not only to cause significant cell kill directly but also to invoke in-vivo immunity via immunological cancer cell death and release the tumor specific antigens (neoantigens) and neoepitopes. It’s precision, adoptability to changing tumor morphological and phenotypic and non-invasiveness OF SBRT makes it convenient to give it repetitively, as long as total equivalent dose is kept within the tolerance limits. Thus the second action of SBRT as a powerful immunogenic tool is yet to be used to its full potential. Following review is compilation of literature to meet that end with proposed strategies to optimize the same. The comprehensive review of the role of SBRT in inducing in-situ vaccination in general, in the landscape of anticancer therapeutic approaches with its ability to kill cancer cells that are definable in imaging and thus reduce interstitial pressure, improve lymphatic drainage for the process of presenting neoantigens, cause vascular normalization consequently improve the oxygenation, synergicity with other anticancer therapies in a shift towards immune positive tumor micro environment (TME) milieu is dealt by the present author elsewhere (1, 2, 3) and this paper deals specifically with ability of SBRT as effective, dependable in-vivo anticancer vaccination tool of choice when used intermittently/cyclically alone or other in-vitro and intra-tumoral procedures.

Cancer is a byproduct of persistent, progressive, pathological, proliferation of normal cells that have gone out of control of restraining immune mechanism of the body. Therefore, the two essential component of treatment approach should be to remove/kill the proliferating cells and restore the immune control mechanism. The first component was addressed over the decades by classical therapies of surgery, radiotherapy (RT) and chemotherapy. The immune mechanism was too complex to be addressed completely by these three methods, and although there was encouraging improvement in the cure over the time, still significant population develop recurrence and sense of cancer as fatal disease on diagnosis persists. The recent rise of immunotherapy has changed the immune-modulation strategies greatly and the process of optimizing this modality to make cancer as chronic disease is within the realm of the possibilities in the near future. The immune escape, hypoxia leading to phenotypic, metabolic and immunosuppressive TME are the fundamental pathogenic changes and importance of vascular normalization, SBRT as a immunological tool are discussed comprehensively, elsewhere and following is wide-ranging coverage of SBRT as in-situ cancer therapeutic vaccine optimizer.

- 2.

Neoantigens, neoepitopes, tumor mutational web and immune escape

Types of tumor antigens are Tumor specific antigens (TSAs), which are either onco-viral antigens or neoantigens of genomic mutations produced by cancer cells and Tumor associated antigens (TAAs) produced both by cancer cells and healthy cells. TSAs related to total number of mutations per analyzed tumor genomic region defining total mutational burden (TMB), if low is associated with weak response to immunotherapy (IMT). TSAs generate tumor response and TAAs can induce “on-target” toxicity reactions within the same structure or “off-target” in similar structure elsewhere. Majority of tumor antigens considered as self proteins by the immune system and “drown” the impact of TSAs. Antigens when presented repeatedly unleashes adaptive immune responses (4). [Alice Benoit].

In addition of neontigens, there are related immune enhancing molecules like epitopes which are involved in immune response. Radiation therapy also enhances the generation of neoepitopes and along with neoantigens produces full repertoire of CD8+ T cells along with immune check point blockade (5). [ Eric C Ko ]

Understanding the complexity of anti-tumor immune response (6) [Evangelos Koustas] is essential to design any strategy, which includes creation / extraction of neoantigen of intracellular origin by effective cancer cell kill; migration of neoantigens to lymphnodes which also depends on interstitial pressure (ISP) and opening up of collapsed of lymphatics; neoantigen incorporation to APCs; presentation of neoantigen by APCs to T lymphocytes (depends on various immune promoting cells and pathways); activation of T effector cells, thus expanding T cytotoxic cells immunosurveillance; infiltration of these activated T cytotoxic cells - tumor infiltrating cells (TILs) to TME (influenced by vascular integrity, ISP, elimination of immunosuppressive cell lineage in the TME); and interaction between T cytotoxic CD8+cells and cancer cells mediated via T-cell receptor (TCR) and major histocompatibility (MHC)-type I molecules or tumor epitopes. The deficiency in any of these steps leads to ineffective therapy and recurrence/progression of the disease. SBRT can play a role in each of these steps in combination with other local or systemic therpies, along with the immunotherapy (KS 3). The process can be furthered by increasing the harvest of tumor specific antigens by local combination therapies with SBRT in view of its ability to act synergistically, bearing in mind the possibility of overlapping short and long-term toxicities. Over and above, it can invoke self sustaining memory capable virtual cycles. The process includes enhancing more specifically Th1 and Th2 cells that activate immune stimulatory macrophages and B-cells, respectively. Negating the TME immunosuppressive cycles is essential along with stimulation of TME immunity pathways, (6) [Evangelos Koustas] which requires well designed combination strategies.

Neoantigens are the product of cancer induced mutations that ordinarily elicit immune response, but over course of time might provide “fuel to the fire” of cancer evolution en route to the immune escape. However, novel peptides neoantigens can also be presented on the cell surface recognizing the cancer cells as “non-self” leading to lysis, referred to as immune editing. This to and fro can lead to expansion or contraction of cancer cell population leading to subclones. Over time, very presence of large load of neoantigens leads to evolution and immune escape (7) [Eszter Lakatos] not recognized by the innate immunity. Subsequent to immunotherapy with high rate of cell death, net result could be high tumor mutational burden with severe neoantigen depletion making cells resistant to check point inhibitors despite initial high tumor mutational burden. The clonal escape mutations continue to be “antigen warm” (high neoantigen burden) with several subclonal neoantigens leading to immune escape. With rapid shrinkage of active clonal population, passive clones continued growing progressively pruning the neoantigens turning it into immune-cold tumor. The post immunotherapy doses, immune landscape is different from the original tumor with new clonal emergence requiring next / additional lines of therapy (7). [Eszter Lakatos]. Since total mutational burden is proportional to the neoantigen production (8) [Chrysanthi Iliadi], proliferated subclones can be expected to have reestablished modified neoantigens.

Tin an individual tumor trunk mutations and heterogeneous branch mutations are present in all regions or at least two regions of the tumor respectively, whereas private branch mutations are unique to one region (9). [Kelsey E. Wuensch] Branch and private branch mutations representing the intratumor heterogeneity of resistant subclones comprises about 40% in hepatocellular carcinoma in a study (10). [Gao Q et al.]. Radiotherapy enhances the response to IMT by especially targeting the trunk mutations (11). [H Kievit ]

Mutations outside anchor position interacts with peptide/MHC complex with TCR leading to recognition of naïve T cells while mutations in the anchor position potentially create high affinity recognition of mutated specific neoepitomes. The authors propose the bioinformatic evaluations of entire neoepitope spectra to identify targets for the tailored therapy. However, vaccination or personalized adoptive CTL transfer therapies favors evolution of escape varients by loss of global MHC expression. Systemic naturl Killer (NK) cell activators and Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T immune cells may preferentially recognize MHC negative tumor cells for elimination. The other combination option is the surgical excision or cytoreduction for the resistant residual lesion (12). [Thomas C. Wirth].

CAR-T adoptive cell therapy has surfaced as breakthrough immunotherapy in cancer especially in hematological malignancies. However in solid tumors antigen escape, toxic reactions, abnormal vascularization furthering tumor hypoxia and insufficient infiltration of CAR T cells leading to immunosuppression are the limiting fctors (13) [LIQIANG ZHONG]. These inadequacies can be obviated by proposed strategy in the present article by titrating the RT dose per fractions to toxicity over a period of time. Since the mechanism action is due INF-γ, TNF-α, perforin and granzyme induced cell kill, independent of antigen-derived peptides and class I molecules of the MHC complex interactions, acting by recognize and bind to proteins or gangliosides on cancer cell surface. Radiotherapy (RT) facilitates CAR T cells homing by pro-inflammatory actions, migration of CAR T cells along with reoxygenation by increasing integrins intercellular adhesion molecules – 1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule – 1 (VCAM-1) expressions in endothelial cells, activating complementary endogenous several antigen specific responses, converting TME immunosuppressive to immune promoting cells etc. Correspondingly, CAR-T cells sensitize and retarget the development of radioresistant cells. In vivo RT dose per of as low as two Gy per fraction has shown expansion of CAR-T cells. Yet another preclinical study in pancreatic cancer has found this schedule as insufficient. Although existing data for combined RT and IMT favours 8 Gy x 3 fractions, in a preclinical glioblastoma study 4 Gy x 1 fraction did extend the survival and certain number showed complete regression (13). [LIQIANG ZHONG]

“Cold” or even an immune “desert” can be reprogrammed to hot tumors by targeting hypoxia. Hypoxia is the foundation on which immune resistance rests due to countless alteration in the metabolites, TME progressive acidosis, over-expression of immune check points, cancer favorable TME immune depletion as well as hypoxia induced tumor promoting autophagy (4). [Alice Benoit ] resulting in plexiform of resistant pathways.

- 3.

SBRT spawned neoantigen, neoepitope generation and in situ vaccination

Two primary effects of Immunogenic cell death with inflammatory cascade and phenotypic changes give the capacity SBRT to extract needed neoantigens along with possible effect in eliminating immunosuppressive cells in the TME for in situ therapeutic vaccine effect. This neoantigens release leads to dendritic cell (DC) cell maturation, antigen cross presentation and anti-tumor T cell response diversification. Single dose fraction eventually acts as immune activator with initial lymphocyte depletion. Also, type I interferon phenotypic effects peak at 8 to 12 Gy single fraction through cGAS/STING pathway. In addition to inducing cluster of differentiation (CD8+) T cell response by radiation generated neoantigens, RT also stimulates immune response via ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis (4) [Alice Benoit].

At higher dose per fraction increases expression of three prime repair exonuclease (TREX1) exonuclease which reduces the accumulation of cytoplasmic dsDNA impacting IFN-ϒ production negatively (14) (Elizebeth Appleton).

Radiation no doubt modulate the tumor microenvironment at low doses (1–4 Gy) (15) [Justin C. Jagodinsky], yet the present author has not gone into detail in view of main focus on antigenicity and adjuvanticity of SBRT, which tends to be significant in the dose per fraction range of 6 to 10 Gy as per endothelial tolerance. A higher dose per fraction of 12 Gy or more needs relook; in view of higher antigenicity of that schedule in case of clinical applicability of improving the tolerance of endothelial cells say by dual recombination technology (16) [Moding].

Two important specific points were demonstrated by Danielle M. Lussiera et al. in their preclinical poorly antigenic, IMT not responding cell lines study. One, non-curative doses of radiation can induce MHC-I neoepitopes leading to tumor lysis populations of CD8+ T cells that in turn sensitize low mutation burden cold tumors tumors to ICT. Two, the delivery of neoantigen generation immunogenic dose of RT (4 to 9 Gy) throughout the tumor population, initially having subclonal immune response may drive spreading epitope resulting in rejection of mutationally heterogeneous tumor (17) [Danielle M. Lussiera].

Phenotypic changes: Antigen-specific CD8 T cell phenotypic analysis showed RT enhanced both antigen-experienced T cells and effector memory T cells. RT activates protein kinase C (PKC) , mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), master immune response regulator nuclear factor-KappaB which are signal transduction pathways as well as transcription factors making them susceptible for immunotherapy response via phenotypic changes. RT up-regulates MHC, as well as by increased expression of specific tumor model antigenic epitopes presentation to MHC on the cell surface resulting in enhanced memory phenotypic CD8 T cells (18). [Andrew B. Sharabi]

Radiation also has ability to immunologically facilitate T-cell mediated killing by altering the biology of surviving cells (19). [Mansoor M Ahmed] Also, it can be hypothesized that SBRT spares irradiation of draining lymph node regions where antigen presentation takes place (18). [Andrew B. Sharabi]

Along with RT, the additional strategies are interleukin-15 (IL-15) agonism (known activator of NK and CD8+ cells) augmenting the expansion antitumor memory CD8 T cells; intratumoral depletion of regulatory T (Treg) cells by targeted glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor–related (GITR) agonism; downregulation of myeloid-derived suppressor (MDSC) cells by molecular restructuring to increase antigen recognition combining with anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (PDL 1) as well as ipilimumab, leading to positive feedback with further destruction of MDSCs. Immunogenic cell death by RT increase in damge-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) made up of group box 1 protein (HMGB1) impacting toll like receptor-4 (TLR-4) (thus dendritic cells), which facilitates greater antigen presentation due to inhibition of intracellular antigen degradation and ATP stimulating aggregation of dendritic cells for antigen presentation in the tumor. NK cells capable of targeting cancer cell spontaneously are not limited by need for antigen presentation or MHC pathway ctivate adoptive cell mediated immunity, which is pronounced in conventional doses and mixed results with SBRT due to competing effects (20). [Blessie Elizabeth Nelson].

Timing with ICT: RT can Damage immune cells locally immediately. It can increase immune suppressive cells as well as signal pathways and immune suppressive factors (21) [Jiaqiang Wang]. Hence synchronizing SBRT and IMT appropriately is critical.

According to the concept of “reoxygenation utilization rate” in hypo-fractionated radiotherapy single fraction cannot utilize the phenomenon of reoxygenation depriving the applicability of one of the 5 radiobiological principles for increase in efficacy of fractionated radiation, unlike in a situation where oxygen utilization goes up to 87% with 6 to 8 fractions with ensuing enhanced response. In the hypofractionated schedule reoxygenation for that dose is likely to be complete by 48-72 hours (22). [Yuta Shibamoto] There is general understanding that SBRT after IMT is less effective and optimum time may be anywhere from 48 hours to < 7 days (23, 24) [Martinez-Zubiaurre, Breen WG]. IMT comparing administration on days 6-10 more effective after RT in a mouse model when compared to day’s 1-5 or 11-15 according to study results by Morris et al. They surmised that T cell response is a reflection of delayed response to RT (25). [Zachary S. Morris, 2016]. Considering critical aspect of reoxygenation and initial TME lymphocyte depletion recovery, least time interval after SBRT could be 48 hours.

Mitigation of “immunosuppressive recoil”: One aspect of avoiding immunoresistance is simultaneously blocking the “immunosuppressive recoil” immediately after SBRT which needs to be countered by blocking these negative pathways for optimum local and absopal effect. SBRT dose above 12 -18 Gy showed Trex 1 exonuclease induced immunosuppressive effect unlike lower doses which propogated DC maturation and immune cell priming shown by Demaria et al and others, although some studies showed better tumor control with 15 Gy single dose (14, 26) . [Demaria – add to the ref list] [Elizabeth Appleton]. Radiation induced downregulation of CD47 has DC phagocytosis suppression effect (14). [Elizabeth Appleton].

Zachary S. Morris et al in their mouse tumor model proved that contrary to their initial hypothesis, untreated second tumor induced Tregs mediate immune-suppression of indexed primary lesion treated by RT combined with intralesional agent for vaccination effect was countered by Treg-depleting anti-CTLA-4 restoring the vaccination effect. The findings are very revealing that “tumor-specific”, Treg-dependent (not ruling out Treg independent other mechanisms like MDSCs), suppressive effect is exerted by the untreated lesions, referred by the authors as “concomitant immune tolerance”. Although the feedback immunosuppressive cascade was lesser in case of small untreated lesions (25) [Zachary S. Morris], one can expect this recoil suppressive mechanism to be of systemic nature impacting even the invisible lesions. Therefore, “concomitant immune tolerance” could be one of the reasons for abscopal effect not living up to its expectation all along. Morris et al also demonstrated that immunosuppressive effects were seen both in 12x1 Gy fraction versus 8 Gy x 3 fractions, even though latter is considered more immunogenic.

One arm of bineray role of autophagy is degradation of MHC I in T cells and DCs, MHC II in MDSCs, impaired PD-L1 degradation all causing deficient neo antigen presentation and impaired T cell action (6) [Evangelos Koustas] which need be countered for positive immune-reponse.

- 4.

Expanding SBRT immunological cascade and immune adjuvants

Effectiveness of any vaccine is not only based on the antigens but also immune adjuvants. With in-situ vaccination in cancer tumor nidus itself supplies the antigen(27) [Mee Rie Sheen 1, mutation prevalent during that time, can be released by fractionated cyclical SBRT and antitumor effect can be expanded disproportionately by systemic or local immune adjuvants. This approach obviates need to identifies and harvests all neoantigens, enhances synergy of SBRT and immunotherapy when combined, minimizes immune escape and above all reduces toxicities. Immune adjuvants acts as slow release system in the nidus ensuring continuum of stimulation to the immune system (28) [Renske J. E] when homed in or tagged. One technology suggested is leading and activating of DCs combined with antigens generated from tumor ablation, which later acting as nidus for slow release sustainable immune stimulation for the drainage lymph nodes. However, there is a possibility of rebound recovery of cancer cells at the edge in sublethal temperature zone (28). [Renske J. E] Since tumor control with vascular disruption is more a short-term (16) [Moding], timed repeated noninvasive delivery of SBRT with non-vascular disruptive dose is likely to maintain long term immune-stimulation without the risk of rebound aberrant vascularization and growth at the edge of ablation that is seen in vascular disruptive methods. Additional advantage with SBRT is dynamic matching with the evolved mutations de novo. Dedritic cell growth factor, feline Mcdonough sarcoma (FMS) like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) ligand demonstrated abscopal effect (29).[Silvia C. Formenti]. Autophagy process has binary role both as immnnoprometer or suppressive depending on the TME. In immunopromotion role autophage by influencing APCs, T-cells, macrophages MHC I cross-presentation of autophagy dependent neontigens and MHC-I, MHC-II in DCs, creates T-cell memory (6). [Evangelos Koustas]. Autophagy can help in extraction of antigens when lysosomal enzymes isolated and degrade intracellular antigens under action of autophagolysosome to several peptides, which get transferred to APC cell surface to get integrated with MHC II in the presence of protein molecules such as calreticulin, ERp60, as well as tapasin etc. Induction of the mitophagy of defective mitochondria pathway in tumor cells that lack signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) leads to enhanced antigen presentation (6) [Evangelos Koustas]. Also, autophagy originated newly developed epitopes improves the antigen availability (6). [Evangelos Koustas ]

- 5.

Beyond SBRT and Immunotherapy combination - enduring immunogencity

Immunologically cold tumors had 10 fold increase in CD8+ infiltrates with combined intralesional plus RT therapy, which jumped to 18 fold when anti-CTLA-4 was added (25) [Zachary S. Morris],.

RT, chemotherapy as well as IMT, generates persistent, long-lived, self renewable memory T cells. Same thing hold good for CAR-T cell therapy (30, 31) . [HANYANG GUAN] Claire C. Baniel et al hypothesized that combination of RT, intratumoral immunocytokine and immune check point blocker as in situ vaccine primes memory B cells responsible for persistent humoral response without need for further stimulation although exact role need to be clarified. Surgery do not display immunogenic memory against the rechallange in the animal models (31) [Claire C. Baniel], indicating rethinking in future may be required about the sequencing the surgery after invoking memory cells by SBRT with or without intralesional therapy bringing in situ vaccination preceding the surgery. The greatest advantage of surgery would be elimination of final group of immune intransigent cold residue for cure or long term control. Evidence is needed whether intermittent repeated SBRT with or without intratumoral techniques can also keep in pace with the molecular mutations improving he B cell memories exponentially.

Baniel et al observed an increase in memory derived anti-tumor IgG antibodies even before engraftment on rechallange indicating antitumor activity even before macroscopic manifestation of cancer(31) [Claire C. Baniel]. Thus, to overcome Treg propagated immunosuppressive effect by the larger nonindexed lesions (25) [Zachary S. Morris] SBRT plus or minus intratumoral agents along with check point inhibitors can be invoked with non-curative dose as “vaccination generators” when clinical extent of disease (non-oligometastatic) does not permit inclusion of all lesions. The other option would be, combining systemic targeted radionuclide therapy alone (to suppress “concomitant immune tolerance”), alternating or in combination with SBRT for in situ vaccination approach (15) [Justin C. Jagodinsky].

Imt, on the average has benefit in 12% of patients indicanting significant group of primary resistance as well secondary resistance, along with burden of large proportion with toxicity risk. Resistance can be dominant at TME level even when antigen specific T cells are high in circulation. Primary problem is poor neoantigen availability with low TMB tumors leading to suboptimal immune priming of APCs. This need to be overcome by use of immune stimulatory agonists promoting stimulatory interferon gens (STING) and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling (14). [Elizabeth Appleton]

Radiotherapy causes gene up regulation, augmented protein degradation, mToR regulated translation increasing the peptide pool combined with increased MHC class I expression resulting in more antigenic peptides presentation for recognition ending in enhanced TCR reportaire. In addition to this induction of tumor antigenicity especially of immunologically cold tumors, SBRT has the ability to cause “adjuvanticity” by invoking regulated immunological cell death, triggering inflammatory signals by stressed or dying cells followed by release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) encompassing ATP, HMGB1 and calreticulin; activation of interferon genes STING triggering the transcription of Type I IFNs to recruit DCs for maturation which helps in naïve T cell cross priming after migrating into the lymph nodes. This is critical for bridging adoptive and innate cell responses (14). [Elizabeth Appleton]

The other dimension is cmbination with other immunogenic local therapies. Intratumorl saponin-Based Adjuvants; TLRS agonists – CpG, analog of synthetic dsRNA polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (Poly-IC) , FLT3L, TLR7/8 agonist Imiquimod, nano particles (28) [Renske J. E.]; Oncolytic virus, oncolytic peptides; thermal therapy; STING agonists; melphalan; rose bengal disodium (PV-10), are other potentially combinations tried with immunotherapy to improve antigenicity and adjuvanticity. However limitations of these therapies are accessibility for administration, especially repeated injections, unequal distribution within the tumor (14) [Elizabeth Appleton] and disruption of the vasculature. Some of these disadvantages can be overcome by nanomedicine technology.

All the above in the background of normalization / oxic conditions of the vasculature by a. timed antiangiogenics, b. limiting inflammation & keeping interstitial compartment supple.

- 6.

Minimizing toxicities

Since SBRT has the propensity to invoke inflammatory cascade via arm of DAMPS & pattern recognition receptors (PRR) potentially can cause serious immediate and long term side effects. With progress in immunotherapy we expect dramatic improvement in the long term survivors, giving importance to avoiding fibrosis and maintaining the extra cellular matrix (ECM) suppleness is as important as cure.

RT has a potential to cause long-term serious complications due to progressive senescence changes on endothelial stem cells and fibrosis of ECM preventing immunogenic cross-talk (32) (Zhao). RT along with IMT must be considered a “double-edged sword” that needs careful planning to avoid risk of synergistic adverse effects in view of higher risk in combination RT + IMT therapy arm. The adverse reaction can be less when interval between RT and immunotherapy is more and higher with certain types of IMTs where both tumor cells and normal tissues develop immune reactions rather than in cancer cells alone (33). [Florian Wirsdörfer]

- 7.

Theory & Perspectives

From inception, radiotherapy has been tried in various fractionated schedules but probably not like chemotherapy in cycles over a period of time. Based on the literature reviewed above, present author proposes the use of use of SBRT schedule in divided fractions, each fraction before a cycle of immunotherapy with or without other combination therapies, with minimum of 3 weeks intervals. The SBRT cycles can be continued till the disappearance of gross disease or unacceptable toxicities. In this proposal radiotherapy is suggested to be used in non- curative single dose (17) [Danielle M. Lussiera] as a prime modality for in-situ vaccine “generator” repeatedly, adapting to the evolution of subclone repopulations as priming dose before each cycle of immunotherapy with or without chemo/targeted therapies. Other local combination therapies known to induce in situ vaccination response that can widen and the intensity of the scope of antigen generation, including adopting nanomedicines, is open to further investigative trials. The total dose of number of intermittent cyclical SBRT should be within the limits of tolerance of combination therapies by “titration” approach. New criteria for time-dose-fractionation for normal tissue tolerance may be evolved following conventional knowledge and the accumulated experience.

Following are some of the points that need to be validated with this approach.

The indications for this approach would be cancers with disseminated metastatic disease, recurrent lesions, locally advanced cancers with inoperable persistent local disease after standard therapy. The SBRT schedule proposed here will be used with the intent to cause local response as well as consistent abscopal effect. Expansion of further indications depends on the preclinical and clinical trials with the proposed approach.

The theoretical model for this proposal in the context of SBRT immunological planning (3) and with the combination of immunotherapy by the present author already published (2). The model is based on the foundation of vascular normalization, immune-phenotypic changes (VIP model) along with metabolic changes (1,3) as important components for cure in advanced cancer. The present article is an extreme focus on one segment of these publications dwelling on systemizing local immunological response of SBRT as an effective

primary tool to invoke in-situ vaccination cascade in the background of normalization of the vasculature (

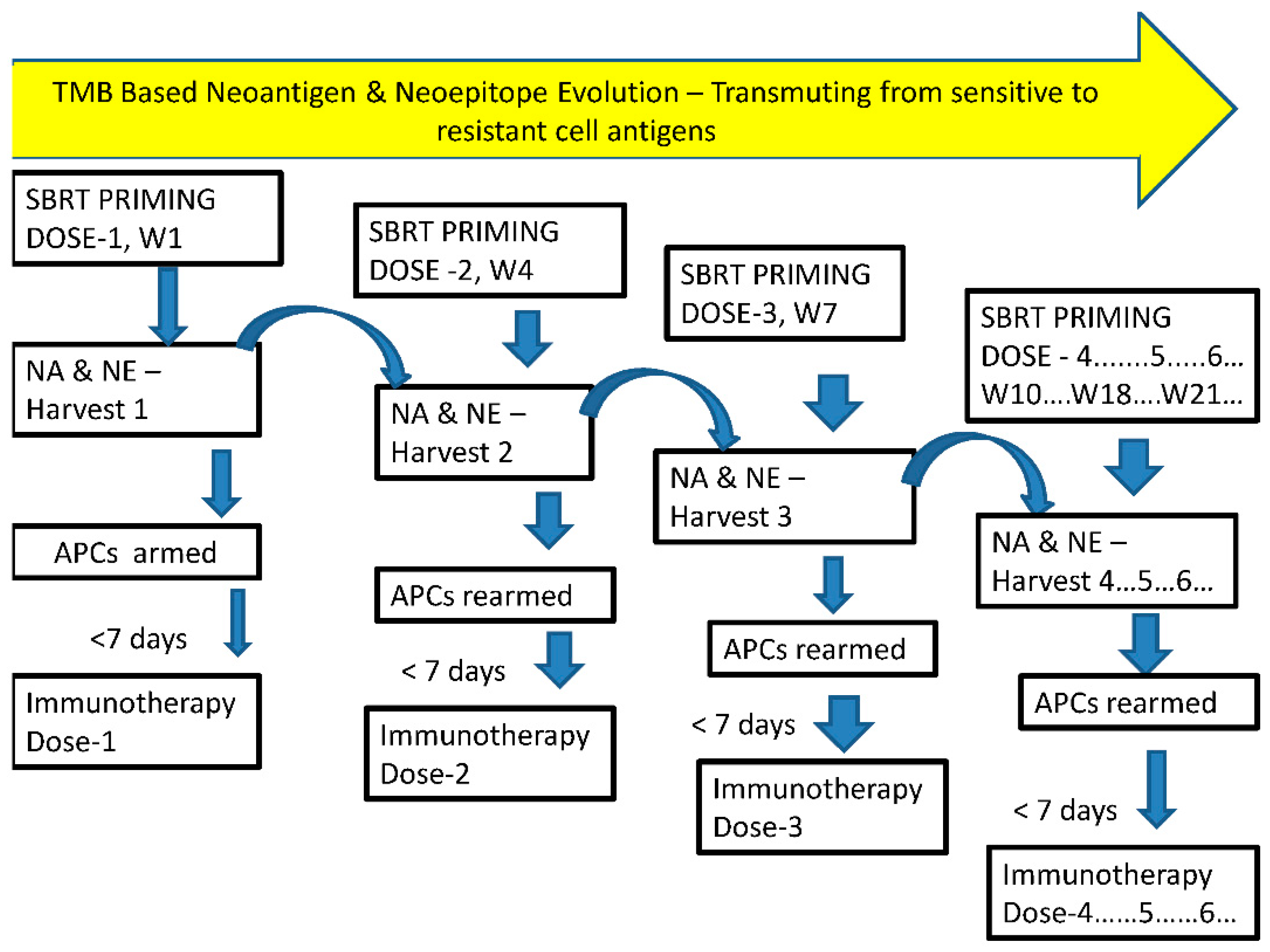

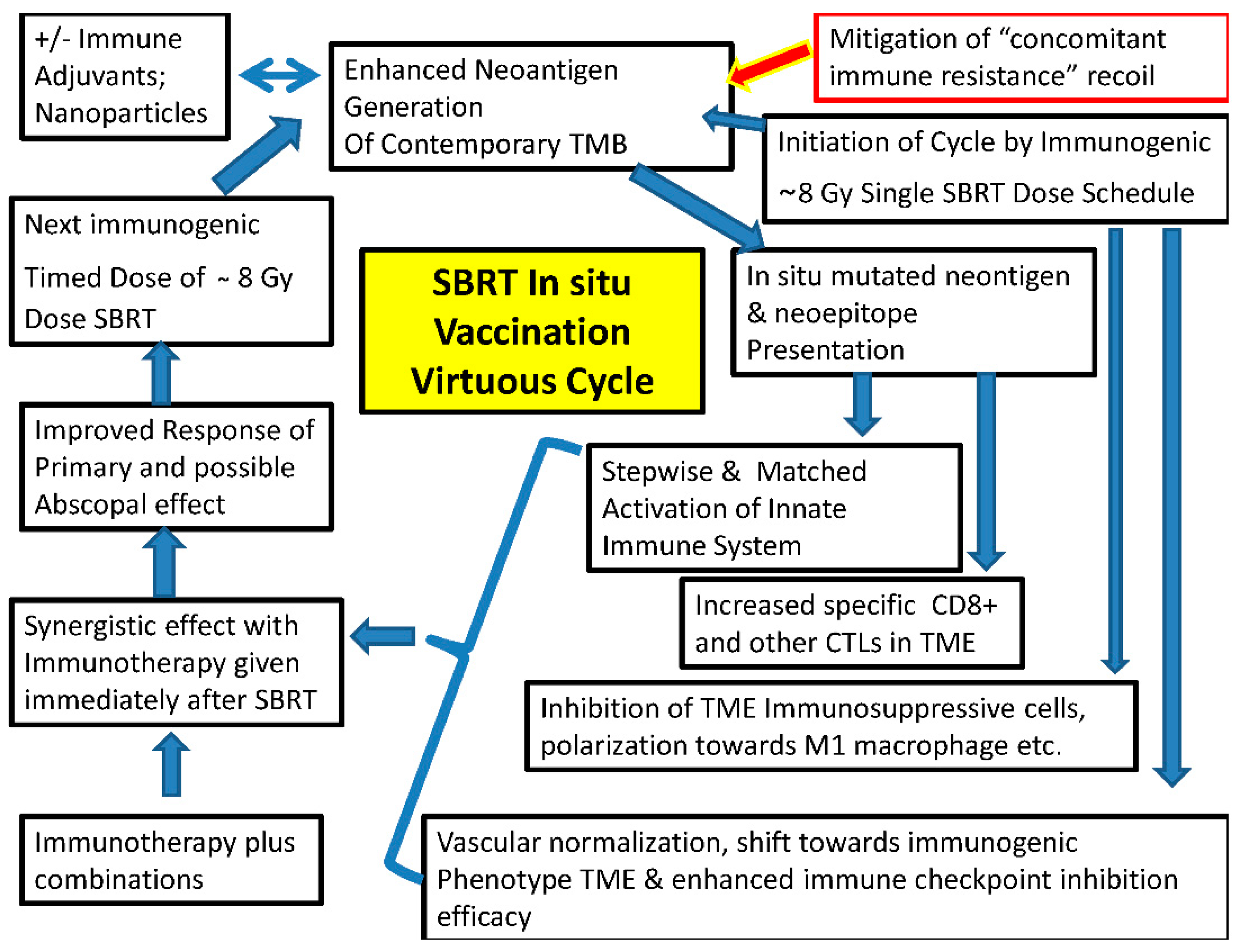

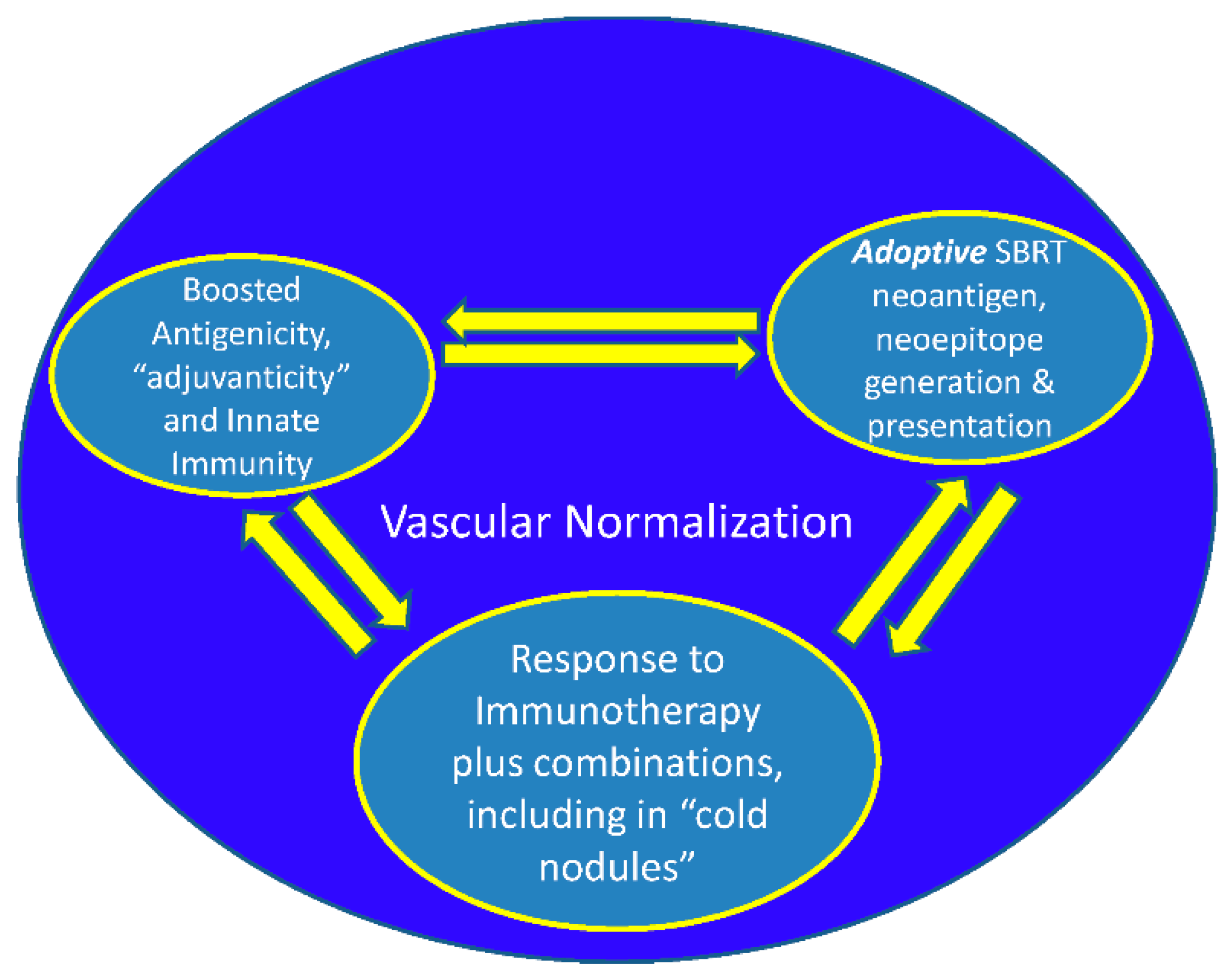

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and Figure 4).

In the present day uderstanding of radiotherapy is undergoing a sea change with irradiated tumor becoming an immunogenic hub for local response, radiotherapy an efficient in situ vaccine generator and a systemic disease modifier rejecting the metastases. Successful radiotherapy acted as vaccine providing lifetime immunological memory (cryptic vaccine), in others dormancy and immune-editing leads to immune escape (29). [Silvia C. Formenti] The pro-immunogenic effects of radiotherapy can be harnessed effectively by correcting the simultaneous immunosuppressive “recoil” by newer immunotherapy agents. In immunotherapy resistant patients radiotherapy can restore the response and are amenable for more complex immunotherapy manipulations (29)[Silvia C. Formenti].

Hypoxia has been the bugbear of radiotherapy resistance with increased mutations from the inception. Now these higher mutation rates and burden can be source of more neoantigens for immune checkpoint inhibition. Additionally, hypoxia is the fertile ground for immunosuppressive cell types such as Tregs, and MDSCs maturing to M2-polarized Tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), TH2 polarized DCs , downregulation of MHC class-I molecules plus NK cell-activating ligands and upregulation PD-L1 on tumor cells that can be countered by combinatorial immunotherapy. In normoxic tumors immunogenic cell death with upregulation of MHC class-I, release of immune stimulatory DAMPS, activation of TLRs, new TAAs, maturation of DCs along with upregulation of MHC-class II leading to T cell priming in the draining lymph node facilitate tumor lysis by cytotoxic T cells NK cells on travelling back to the tumor. From intensely immunosuppressive intrinsically radioresistant hypoxic tumors, reoxygenation with fractionated radiotherapy in combination with immunotherapy enhances local control and abscopal effects (34) [Franziska Eckert]. Added to this cell kill of susceptible cells, decreased ISP, increased immune cell infiltration, and increasing IMT penetration for subsequent doses completes the positive effects of cyclical SBRT.

Unlike in conventional RT, SBRT along with enhanced cell kill per fraction dose and neoantigen generation mainly induces immune resistance recoil by at least three major mechanisms: a. Treg cells proliferation, b. BMDCs mobilization and 3. Activation of Trexol pathway by DAMPS.

IMT can sensitize tumors for subsequent radiotherapy reducing the required radiation dose (35) [Zhiru Gao ], 2023] validating the concept of SBRT of cyclical type. Thus with the proposed schedule synchronizing the proliferating cancer cells to susceptible phases of cell cycle, RT, chemotherapy (CT) and IMT sensitize each other during the entire course of systemic therapies, with control over dose modification to limit the toxicities]

Increasing vascular normalization, professional phagocytosis, decreased ISP, increased neoantigen lymphatic drainage, mitigation of non specific antigen flood, importance of supple extracellular matrix for effective in-situ immune response is discussed elsewhere (3).

Avoiding RT dose wastage is possible by not delivering during the hypoxic phase, but to time it with each improved phases of oxygenation over time. Also, the approach can enhance innate immune mechanisms by decreasing tumor burden and increasing the lymphocytes by SBRT subsequent (vaccination) boost doses, possibly arming the memory cells against future mutations, recurrence and second malignancies.

Even though appropriate dose per fraction need to be decided for combined RT and CAR-T cell therapy, proposed principles in this article of single dose fractions delivered before each cycle of CAR-T cell therapy, over a period of time, keeping watch on the toxicities can be followed in future trials.

-

The study by Danielle M. Lussiera (17) indicates that even a single immunogenic dose of radiation may be sufficient, which needs to be validated by clinical trials. With the strategy of divided dose delivery before the immunotherapy cycle, one could titrate the fractions of SBRT, depending on immunologically hot or cold tumors, till complete response of the tumor and / or disappearance of CTCs/markers in liquid biopsy (Fig 4), thus limiting the fraction related-toxicity too in well responding population. Even non-curative dose of radiation can reduce the number proliferating cancer cells and decrease ISP, improves re-oxygenation etc. in addition to neoantigen generation.

With cyclical SBRT preceding each cycle of combination with CT/IMT with the objective of enhancing antigenicity and “adjuvanticity”, it is reasonable to expect reducing treatment volume, normal tissue recovery before each fraction, modification of schedule depending on the appearance of grade of toxicities (titration). The counter point would be repopulation of the cancer cells in between the fractions. In such a scenario this technique can be initiated in patient with disseminated systemic disease as a clinical trial with strategies to counter “concomitant immune resistance” caused by Tregs mobilization by non-indexed lesions (one of which is combining with IMT).

In patients with dissiminated metastases, since the technique is with explicit purpose of “in situ vaccine generator” one could select safer locations of metastases, away from critical areas for SBRT delivery. These in situ vaccination of SBRT effects may be diversified, intensified, amplified, sustained indefinitely (with activation of memory T cells) by cyclical SBRT keeping the total equivalent dose within acceptable toxicity levels by the adoption of titration principle.

The points to be considered to reduce the possible toxicities of combined therapy are a). Limit the dose per fraction less than 10 Gy and as low as 5 Gy per fraction to avoid the vascular endothelial disruption and senescence which causes fibrosis in the long-term. b). Titration of dose per fraction and total dose of SBRT: Reduce the subsequent dose per fraction in case of appearance of higher grade acute toxicities or skip the further fractions altogether. It can be reintroduced with later IMT cycles in case of persistence of residual lesion. c) Prevention: i). Selecting the non critical areas of metastases for antigen generation strategy when selected lesions are treated in disseminated metastases. ii). Limitation of the volume of radiation in large lesions or the one near the critical structures by adopting sub-volume treatment techniques described by Tubin et al (36) [Tubin S]. iii). Incorporate trials to maintain the suppleness of ECM by TGFβ blockers (32) [Zhao ] or simulate embryonic stem cell reversal (37) [Joyce]

Conventional dose fractionation schedule has taught us that cells become resistant if radiation overall time is too much prolonged. However, SBRT here is primarily used for its ability in terms of antigenicity and adjuvanticity facilitating immunotherapy tumor response necessitating a TDF model redesigning as such starting with animal studies.

According to the present author analyzing and forming comprehensive combinations for the constantly shifting trunk and branch mutational pattern can be obviated by SBRT delivered in divided doses targeting the prevailing trunk mutations just before each cycle of IMT/targeted therapies without excluding other potential local therapies.

Radiotherapy usually synergistic and rarely, if at all, antagonistic with other forms of therapies as long as there are no overlapping significant toxicities. Therefore, SBRT and other local therapies combinations along with immunotherapies are potentially feasible as long as vascular integrity is maintained.

Overall Dose per fraction of < = 10 Gy per fraction avoids Trex 1 exonuclease activation and consequent immune suppression in addition to maintaing the integrity of the vasculature encouraging antitumor T cell infiltration.

Surgery can be sequenced, after in situ immunization schedules (akin to total neoadjuvant protocol in carcinoma rectum).