Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

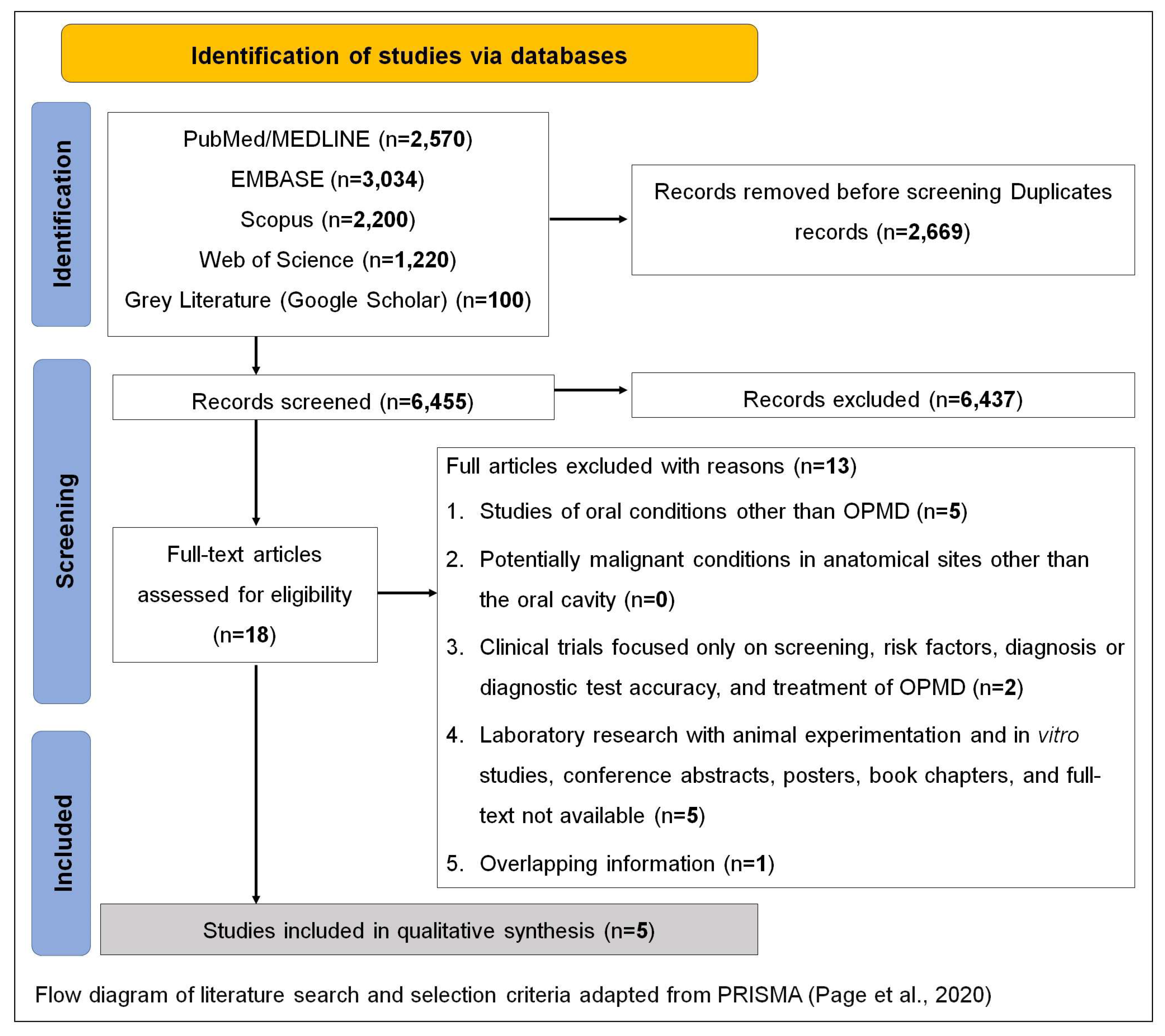

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

2.2. Information sources and search

2.3. Selection of sources of evidence

2.4. Data synthesis and descriptive analysis

3. Results

3.1. Selection and characteristics of sources of evidence

3.2. Synthesis of results

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges for professionals in delivering bad news regarding OPMDs

4.2. Communication about risk factors related to OPMDs

4.3. Communication about rates of malignant transformation

4.4. Treatment-related communication

4.5. Communicating clinical/psychosocial implications to patients

4.6. Patients' preferences on OPMD communication

4.7. General recommendations on OPMD communication

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Kujan, O.; Aguirre-Urizar, J.M.; Bagan, J.V.; González-Moles, M.; Kerr, A.R.; Lodi, G.; Mello, F.W.; Monteiro, L.; Ogden, G.R.; et al. Oral potentially malignant disorders: A consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2020, 27, 1862–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, F.W.; Miguel, A.F.P.; Dutra, K.L.; Porporatti, A.L.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Guerra, E.N.S.; Rivero, E.R.C. Prevalence of oral potentially malignant disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iocca, O.; Sollecito, T.P.; Alawi, F.; Weinstein, G.S.; Newman, J.G.; De Virgilio, A.; Di Maio, P.; Spriano, G.; López, S.P.; Shanti, R.M. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral cavity and oral dysplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of malignant transformation rate by subtype. Head Neck 2019, 42, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitakis, N.G.; Pentenero, M.; Georgaki, M.; Poh, C.F.; Peterson, D.E.; Edwards, P.; Lingen, M.; Sauk, J.J. Molecular markers associated with development and progression of potentially premalignant oral epithelial lesions: Current knowledge and future implications. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2018, 125, 650–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P. How can Doctors Improve their Communication Skills? J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, JE01–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surbone, A. Telling the truth to patients with cancer: what is the truth? Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.G.B.; Treister, N.S.; Ribeiro, A.C.P.; Brandão, T.B.; Tonaki, J.O.; Lopes, M.A.; Rivera, C.; Santos-Silva, A.R. Strategies for communicating oral and oropharyngeal cancer diagnosis: why talk about it? Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 129, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadakamadla, J.; Kumar, S.; Johnson, N.W. Quality of life in patients with oral potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 119, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadakamadla, J.; Kumar, S.; Lalloo, R.; Johnson, N.W. Qualitative analysis of the impact of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders on daily life activities. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0175531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadakamadla, J.; Kumar, S.; Lalloo, R.; Babu, D.B.G.; Johnson, N.W. Impact of oral potentially malignant disorders on quality of life. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2017, 47, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondivkar, S.M.; Gadbail, A.R.; Gondivkar, R.S.; Sarode, S.C.; Sarode, G.S.; Patil, S. Impact of oral potentially malignant disorders on quality of life: a systematic review. Futur. Oncol. 2018, 14, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondivkar, S.M.; Bhowate, R.R.; Gadbail, A.R.; Sarode, S.C.; Patil, S. Quality of life and oral potentially malignant disorders: Critical appraisal and prospects. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 9, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Khandpur, M.; Khandpur, S.; Mehrotra, D.; Tiwari, S.C.; Kumar, S. Quality of life among Oral Potentially Malignant Disorder (OPMD) patients: A prospective study. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2020, 11, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waal, I. Knowledge about oral leukoplakia for use at different levels of expertise, including patients. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waal, I. Oral Leukoplakia: Present Views on Diagnosis, Management, Communication with Patients, and Research. Curr. Oral Heal. Rep. 2019, 6, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocklehurst, P.R.; Baker, S.R.; Speight, P.M. A qualitative study examining the experience of primary care dentists in the detection and management of potentially malignant lesions. 2. Mechanics of the referral and patient communication. Br. Dent. J. 2010, 208, E4–E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Chen, S.-C.; Peng, H.-L.; Chen, M.-K. Unmet information needs and clinical characteristics in patients with precancerous oral lesions. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2015, 24, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, P. Communication, Counseling and Compassionate Care: The least explored and challenging Palliative Care approaches among Primary Care Physicians - Clinical Case series of Oral Potentially malignant disorders in Tamil Nadu. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baile, W.F.; Buckman, R.; Lenzi, R.; Glober, G.; Beale, E.A.; Kudelka, A.P. SPIKES—A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer. Oncol. 2000, 5, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozier, R.G.; Horowitz, A.M.; Podschun, G. Dentist-patient communication techniques used in the United States. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 142, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, E.; Davis, T.C.; Williams, M.V.; Ma, E.M.; Parker, R.M.; Glass, J. Health Literacy and Cancer Communication. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2002, 52, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorini, L.; Atín, C.B.; Thavaraj, S.; Müller-Richter, U.; Ferranti, M.A.; Romero, J.P.; Barba, M.S.; García-Cuenca, A.d.P.; García, I.B.; Bossi, P.; et al. Overview of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders: From Risk Factors to Specific Therapies. Cancers 2021, 13, 3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunjal, S.; Pateel, D.G.S.; Yang, Y.-H.; Doss, J.G.; Bilal, S.; Maling, T.H.; Mehrotra, R.; Cheong, S.C.; Zain, R.B.M. An Overview on Betel Quid and Areca Nut Practice and Control in Selected Asian and South East Asian Countries. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 55, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell, E.; Kujan, O.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Sloan, P. Oral epithelial dysplasia: Recognition, grading and clinical significance. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 1947–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Gellrich, N.-C.; Rana, M. Comparison of health-related quality of life of patients with different precancer and oral cancer stages. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 19, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, A.R.; Lodi, G. Management of oral potentially malignant disorders. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 2008–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingen, M.W.; Abt, E.; Agrawal, N.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Cohen, E.; D’souza, G.; Gurenlian, J.; Kalmar, J.R.; Kerr, A.R.; Lambert, P.M.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders in the oral cavity. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2017, 148, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingen, M.W.; Tampi, M.P.; Urquhart, O.; Abt, E.; Agrawal, N.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Cohen, E.; D’souza, G.; Gurenlian, J.; Kalmar, J.R.; et al. Adjuncts for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders in the oral cavity. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2017, 148, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoghier, A.; Ni Riordain, R.; Fedele, S.; Porter, S. Web-based information on oral dysplasia and precancer of the mouth – Quality and readability. Oral Oncol. 2018, 82, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panta, P.; Sarode, S.C.; Sarode, G.S.; Patil, S. Potential of web-resource on ‘oral dysplasia and precancer’! Oral Oncol. 2018, 84, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güneri, P.; Epstein, J.; Botto, R.W. Breaking bad medical news in a dental care setting. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2013, 144, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnieli-Miller, O.; Pelles, S.; Meitar, D. Position paper: Teaching breaking bad news (BBN) to undergraduate medical students. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 2899–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, S.; McConnell, M. Teaching dental students how to deliver bad news: S-P-I-K-E-S model. J Dent Educ 2012, 76, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosshard, M.; Schmitz, F.M.; Guttormsen, S.; Nater, U.M.; Gomez, P.; Berendonk, C. From threat to challenge—Improving medical students’ stress response and communication skills performance through the combination of stress arousal reappraisal and preparatory worked example-based learning when breaking bad news to simulated patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, M.G.; Lee, U.Y.A.; Luk, K.Y.C. An exploration of clinical communication needs among undergraduate dental students. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 27, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Author (Year) | Country | Study design | Population | Sample | OPMD studied | Thematic aspects on OPMD communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brocklehurst et al. (2010) [18] | The United Kingdom | Semi-structured interviews | Dental practices | 18 | OPMD | Information that is given to the patient The patient's response to being told that a potentially malignant lesion has been detected The advice given to the patient about the known risk factors of malignant disease Comments on the management of potentially malignant disorders in practice before a referral is made Practical aspects of the referral process detailing how dentists refer and who they send their referrals to |

| 2 | Raman P. (2021) [20] | India | Case report | Patients with OPMD | 13 | Oral Leukoplakia Palatal Lesions in Reverse Smokers Erythroplakia PVL OLP OLL OLE OSF |

Communication and habit counseling of patients with OPMD |

| 3 | Van der Waal I. (2018) [16] | The Netherlands | Comment | NA | NA | Leukoplakia | This study discussed how the subject of oral leukoplakia might be communicated among the various healthcare workers and among patients The article comments aspects such as definition, clinical classification, biopsy, the presence of epithelial dysplasia is an important risk marker of malignant transformation, |

| 4 | Van der Waal, I. (2019) [17] | The Netherlands | Review | NA | NA | Leukoplakia | How to inform a patient who has a leukoplakia? |

| 5 | Lin H, et al (2015) [19] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional descriptive study | Patients with OPMD | 106 | OPMD | This study investigated: anxiety, attitudes towards cancer prevention and unmet information needs; differences in anxiety and attitudes towards cancer prevention between met and unmet information needs; and the associated factors of unmet information needs for patients with precancerous oral lesions. |

| OPMD themes | Findings |

|---|---|

| Insecurity to talk about the diagnosis | • “The most common explanation given to patients, once a lesion was found, was that the dentist would like a second opinion” [18] • “There was a concern expressed by some primary care dentists about the problem of not providing the patient with enough information to prompt them to attend for their appointment with secondary care” [18] |

| Need for training on communication techniques | • “The appropriate use of language was a concern for many dentists in order to avoid patient anxiety. In fact, some would deliberately describe the lesion in different terms, avoiding any terms associated with malignancy” [18] • “The present study suggests that more can be done to train primary care dentists in health promotion and patient communication” [18] |

| Patient health literacy | • “It is a challenge to properly inform patients affected by leukoplakia. Some patients are very well educated and are looking for rather detailed information at a high, sometimes even academic level. They may want to be involved in the decisions that have to be taken, for example, in the taking of a biopsy or, even more so, in the decision to be treated or not to be treated” [16] • “The majority of patients, want to be guided in their decision-making by their doctor and will ask for clear and concise information. One should realize that most of the available information on oral leukoplakia, in writing or through the Internet, is much too complicated for lay people” [16] • “Health education and individual counselling should be provided to satisfy the information needs of this population” [19] • “Patients with unmet information needs had higher levels of anxiety than those whose information needs were met poor health literacy for patients who had betel nut use, low health literacy and insufficient skills for obtaining, reading and understanding information to make appropriate health decisions” [19] |

| Risk factors | • “While some of the dentists did provide leaflets at their practice, there were also some who did not believe in providing patients with any more information” [18] • “Many practices were proactive in talking about smoking cessation” [18] • “A common complaint among those dentists who had tried to provide smoking cessation was that they felt frustrated because it had no unit of dental activity value and they could not prescribe the nicotine replacement therapy” [18] • “Further work is required to understand why dentists do not feel comfortable talking about alcohol as a risk factor” [18] • “Patients with precancerous oral lesions who had high levels of state anxiety, long duration of time since quitting betel nut chewing and were without a history of oral cancer were more likely to have unmet information needs” [19] • “The participants in our study reported betel nut use and showed passive motivation for regular oral mucosal screening, indicating that they were at risk for developing pre-malignant oral lesions” [19] • “Enhancing provider–patient interaction and presenting essential information first can help patients follow the instructions for cancer prevention” [19] • “Unmet information needs were associated with the time since quitting betel nut chewing and a history of oral cavity cancer. Patients who had quit using a harmful substance and who also had previous illness experiences were different from those who were willing to adopt health promotion behavior such as cancer prevention. Because of their prior experience of illness and their decision to quit betel nut chewing, these patients might have a higher intention to participate in oral mucosal screening, including regular follow-up testing and future cancer prevention program” [19] |

| Malignant transformation | • Leukoplakia: “A probably frequently occurring confusion is that, in the absence of epithelial dysplasia, the pathologist may conclude his report by saying “This is not a premalignant lesion.” As mentioned before, oral leukoplakia is primarily a clinical term without specific histopathological features. At histopathological examination, one may or may not observe epithelial dysplasia” [16] • “The patient should be informed that the leukoplakia may recur within a period varying from some weeks, months, or several years. They also should know that the risk of oral cancer development may not be eliminated by the excision. Although the efficacy of follow-up visits has never been shown, it seems preferable to offer such visits, mainly for reassurance of the patient" [17] |

| Treatment approaches | • “Oral leukoplakia can be treated by a variety of modalities such as cold-knife surgery or laser surgery, CO2 evaporation, photodynamic treatment, and non-medical treatments. As has been shown in numerous studies, including a Cochrane review, not any of these treatment modalities are truly effective in preventing or decreasing the risk of malignant transformation. Therefore, the question remains whether or not to treat oral leukoplakia” [16] • “Spontaneous regression of non-dysplastic leukoplakia is in my experience extremely rare as well” [16] • “The increased morbidity in such instances should be properly weighted against the expected benefit of the treatment” [16] • “In large, diffuse or multiple oral leukoplakias, one may choose to perform an “excisional” biopsy of the clinically most suspected area only, if present, or to perform multiple biopsies (mapping). In any case, the patient should play an important role in this shared decision taking. Some will prefer not to have active treatment while others persist to be treated, even in case of extensive or multiple oral leukoplakias. A similar divergence in opinion may arise in case of recurrence. Some patients do not want to undergo treatment again, while others insist on retreatment” [17] • “The inadequate expression of emotions and lack of stress release may interfere with information-seeking and treatment decisions. Support and listening are needed to help these patients deal with the treatment-decision process” [19] |

| Follow-up approaches | • “There is no evidence that lifelong follow-up programs for treated or untreated patients with leukoplakia are effective in preventing the development of oral cancer. Most likely, follow-up programs will not result in improved survival in case of cancer development either. Nevertheless, it is common practice, i.e. For reassurance of the patient, to follow up the patients. Depending on various aspects, such as the extent of the leukoplakia and the presence and degree of epithelial dysplasia, intervals may vary from 3 to 6 months, lifelong. Changes in the clinical presentation and, particularly, symptoms are ominous signs of malignant transformation” [16] • “It is well understood that such follow-up programs may not be feasible all over the world. Besides, there is the issue of patients’ compliance. After several years of uneventful follow-up, some patients will discontinue the follow-up program” [16] |

| Clinical/psychosocial impacts | • “Patients reported their mouth condition having a debilitating effect on their psychological well-being and social interactions” [9] • “Physical impairment and functional limitations’ were the most important theme for many of the patients” [9] • “The impacts of OPMD also extended beyond physical impairment and functional limitations to aspects of daily living, notably psychological and social wellbeing” [9] • “A high level of anxiety about precancerous oral lesions was more prevalent among patients with unmet information needs than among those whose information needs were met” [19] |

| Patient preferences on OPMD communication | • “The majority of the dentists questioned suggested that patients were not overly distressed about a positive screen, they just go along with the suggestion” [18] • “Most patients will not be interested to listen to an academic lecture by their doctor on the various aspects of oral leukoplakia but, instead, they want to be informed in an understandable way particularly when it comes to the further management” [17] • “Patients reported higher information needs related to ‘To be fully informed about your test results as soon as possible.’ and ‘To be fully informed about all of the benefits and side effects of treatment or surgery before you agree to have it.” [19] |

| Recommendations | • “A primary care physician should be responsible, humble, knowledgeable, and skillful to deliver an effective holistic care by inculcating the practice of effective communication of bad news, timely habit cessation counseling and compassionate care as a part of routine dental screening” [20] • “There is a delayed presentation of oral pre cancer and oral cancer in India, as approximately 50% of patients are diagnosed at last stage since the asymptomatic pre cancer lesions are missed by oral physicians/dentists either due to lack of timely communication and habit counseling, lack of knowledge, or inappropriate attitude, putting all in a nut shell - sheer lack of empathy and commitment towards patient care and society” [20] • “The author believes that the three most important, least explored and challenging palliative care approaches namely, “Communication,” “Counseling,” and “Compassionate care,” should be effectively practiced by a primary care physician, to improve their level of commitment to society and attitude towards patient care which can help in early diagnosis of OPMD and decreased incidence of oral cancer, thus improving quality of life of patients” [20] • “Communication on this subject with patients should be in easy to understand wording, avoiding professional terminology as much as possible” [16] • “One may consider to send a brief summary of the discussion held with the patient in easy to understand language” [16] |

| OPMD themes | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Communication technique SPIKES protocol* [12,21] |

• S: Setting

• P: Perception

• I: Invitation

• K: Knowledge

• E: Empathy

• S: Summarize and strategize

|

|

Telling the truth about: Risk factors Malignant transformation, treatment approaches Follow-up approaches Clinical/psychosocial impacts |

• Know your patient's health literacy level to define the methodology and communication tools that will be used to inform the OPMD diagnosis • Have leaflets with images that help explain the diagnosis to the patient • Avoid professional terminology as much as possible • Speak proper terms of malignancy “the white or red patch can turn into cancer” • Inform about the risk factors associated with diagnosed OPMD, and explain the scientific reasons for this association • Raise awareness of the importance of avoiding life style risk factors when they are present • Inform about the potential malignancy rate of diagnosed OPMD according to the clinical, demographic and geographic characteristics of the population in which the patient is inserted • Talk about the uncertainties that exist in determining whether the diagnosed OPMD will change to oral cancer • Inform about the main clinical manifestations of diagnosed OPMD, as well as the impact that these manifestations could have on daily life • Explain the available treatment modalities and make a decision prioritizing the patients' well-being, the potential morbidities of treatment (eg. excision of large areas) as well as their values and preferences • Talk about the uncertainties that exist regarding recurrence and malignant transformation, even after treatment • Raise awareness of the need for continuous follow-up throughout life, especially with the aim of avoiding late diagnosis • Explain that the interval between follow-up appointments will depend on several factors, such as clinical characteristics, the professional's judgment and updates of scientific evidence on follow-up protocols for each OPMD • Although a patient's health literacy is relevant to understanding their condition, ask the patient repeatedly about the doubts and emphasize the most important points until he/she fully understands • Explain to observe any changes of symptoms (eg. pain) and report back even before the next review appointment |

| Recommendations for dental students | • In the academic setting, dental students must repeatedly accompany the senior professional in communicating bad news, in order to have the opportunity to learn and practice, before carrying out the communication alone. • Training in communications skills, the SPIKES protocol, possible emotional reactions from patients and caregivers, as well as having the knowledge to answer questions they might have should be included in dental school curriculum • Different teaching modalities by means of education and practice are recommended, such as worked examples and simulated patients, role-play sessions, videos on patient communications, presentation and experience sharing from tutors and senior students |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).