Submitted:

05 August 2023

Posted:

07 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Animal treatments

- Group I (GI)- Control group (normal saline).

- Group II (GII)- Alloxan (120 mg/kg/day) (Diabetic group).

- Group III (GIII)- Alloxan + DMF (20 mg/kg/day).

- Group IV (GIV)- Alloxan + DMF (40 mg/kg/day).

- Group V (GV)- Alloxan + DMF (80 mg/kg/day).

- Group VI (GVI)- Alloxan + MET (200 mg/kg/day).

- Group VII (GVII)- Only DMF (80 mg/kg/day).

2.3. Diabetes model and treatment methods

2.4. Biochemical analysis

2.5. Analysis of oxidative stress markers in kidney and liver homogenate

2.6. Histopathological examination

2.7. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

2.8. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Biochemical analysis

3.1.1. Pharmacological intervention and their effects on levels of blood glucose

3.1.2. Pharmacological intervention and their effects on levels of blood urea nitrogen

3.1.3. Pharmacological intervention and their effects on levels of blood creatinine

3.1.4. Pharmacological intervention and their effects on AST and ALT levels

3.1.5. Pharmacological intervention and their effects on levels of blood albumin

| Treatment groups | Glucose levels (mg/dL) |

BUN (mg/dL) |

CRT (mg/dL) |

AST (U/L) |

ALT (U/L) |

Albumin (g/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Group I Group II Group III Group IV Group V Group VI Group VII |

101.8±3/304 222.8±7.042a 182.5±6.608c 167±10.420d 153±8.406e 105.5±1.732b 108.3±4.573 |

55.2±9/311 79.2±5.02 a 73.0±11.27 64.8±14.65 60.6±6.731 c 40.2±5.495b 62.4±5.941 |

0.418±0/087 0.554±0.032 a 0.5±0.049 0.488±0.058 0.452±0.023 c 0.432±0.008 b 0.448±0.26 |

32.42±1/293 76.9±8.926 a 64.4±10.01 37.8±5.621 c 34.32±5.837d 34.04±3.182 b 26.36±4.268 |

39.3±4/57 87.2±3.982 a 66.35±2.87 45.85±4.219c 43.5±33.73d 35.3±5.899 b 38.65±7.887 |

4.06±0/439 2.94±0.403a 2.8±0.122 2.84±0.151 3.3±0.2 4.12±0.178b 4.3±0.204 |

3.2. Assessment of oxidative stress markers

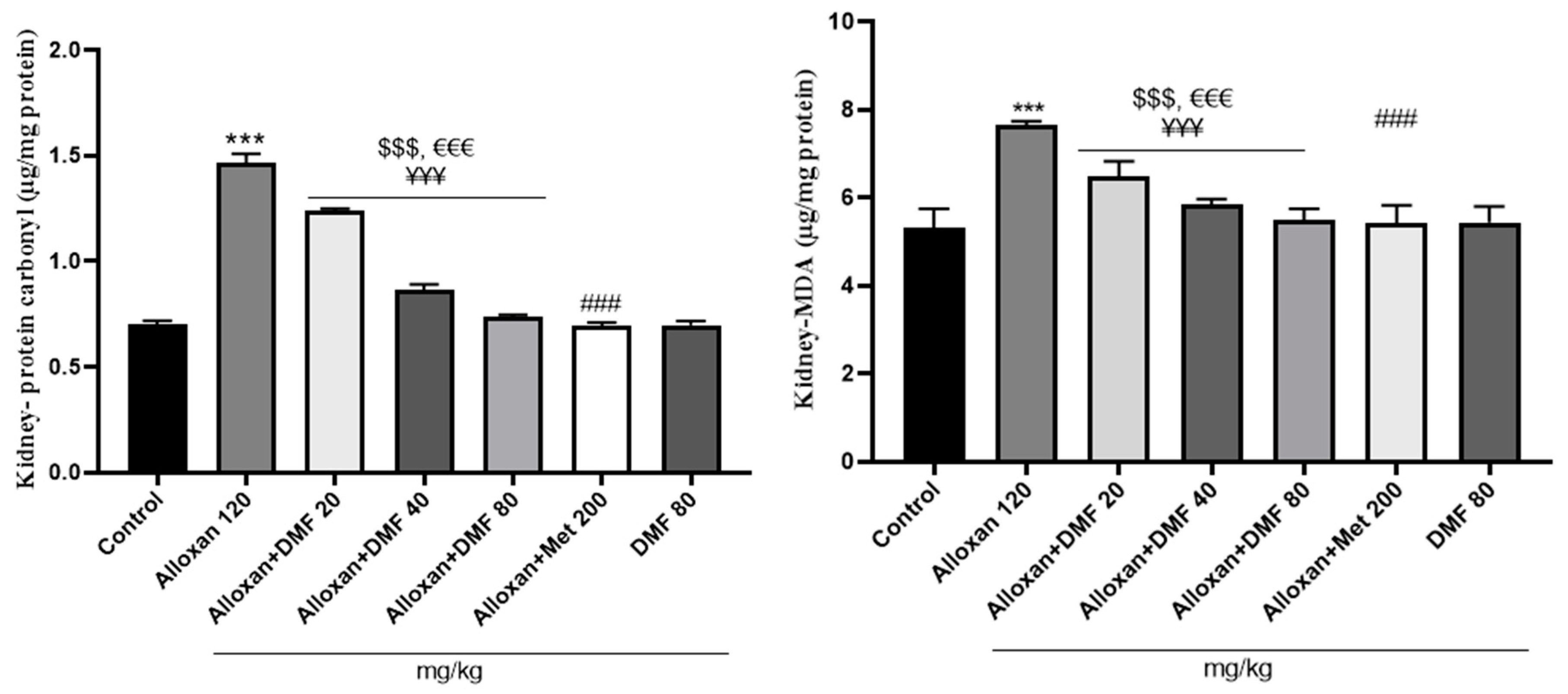

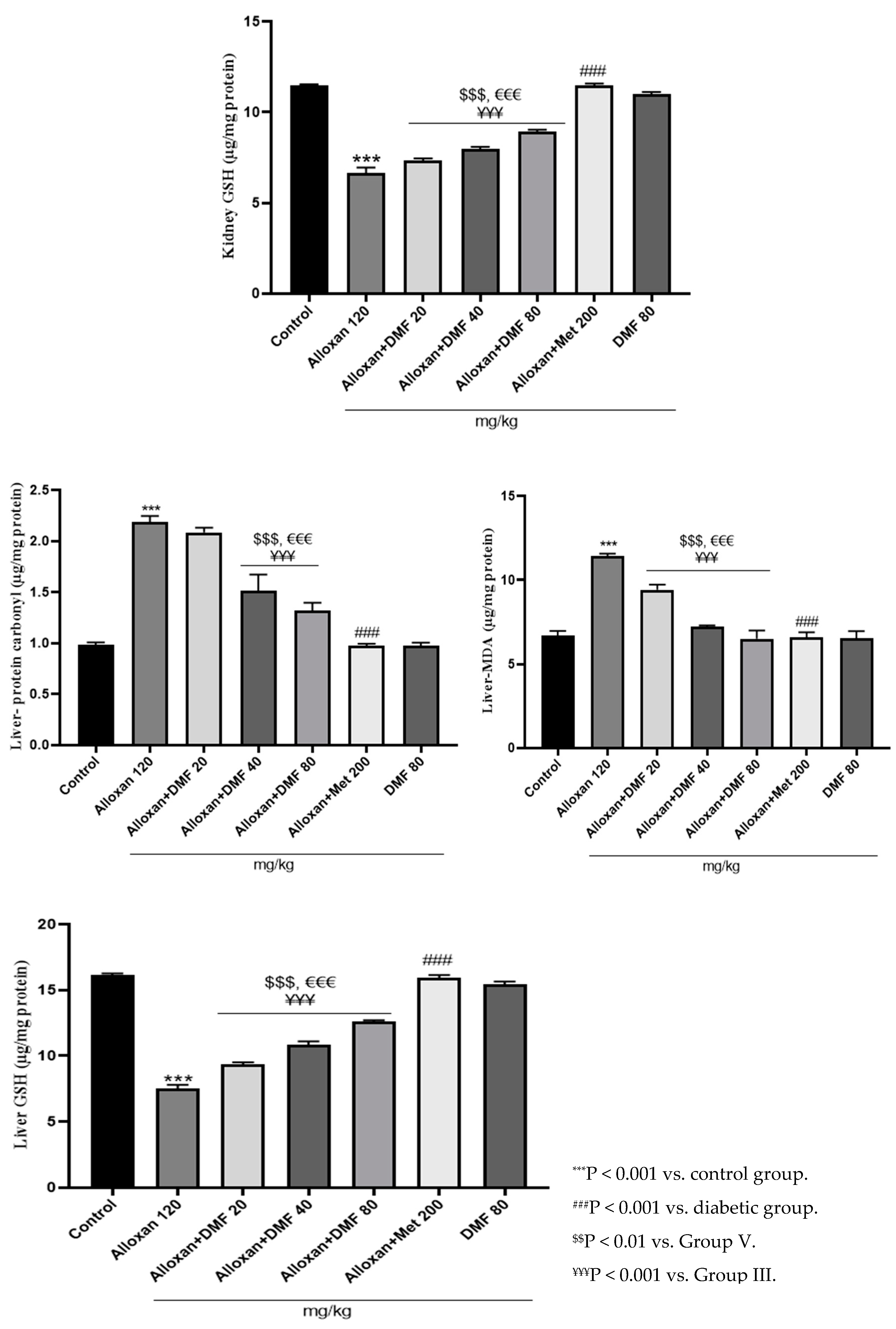

3.2.1. Pharmacological intervention and their effects on kidney and liver MDA content

3.2.2. Pharmacological intervention and their effects on kidney and liver protein carbonyl content

3.2.3. Pharmacological intervention and their effects on kidney and liver GSH levels

3.3. Histopathological observations

3.3.1. Renal histopathological changes

3.3.2. Hepatic histopathological changes

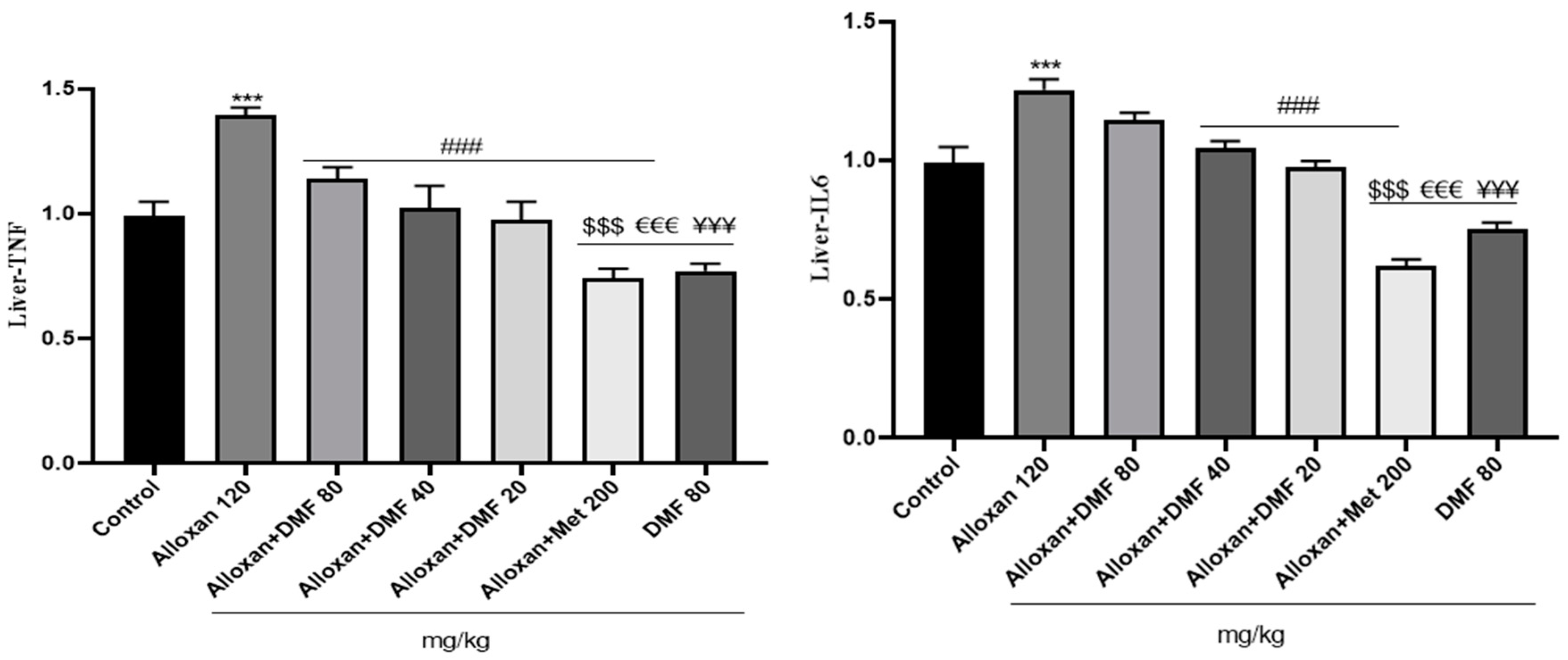

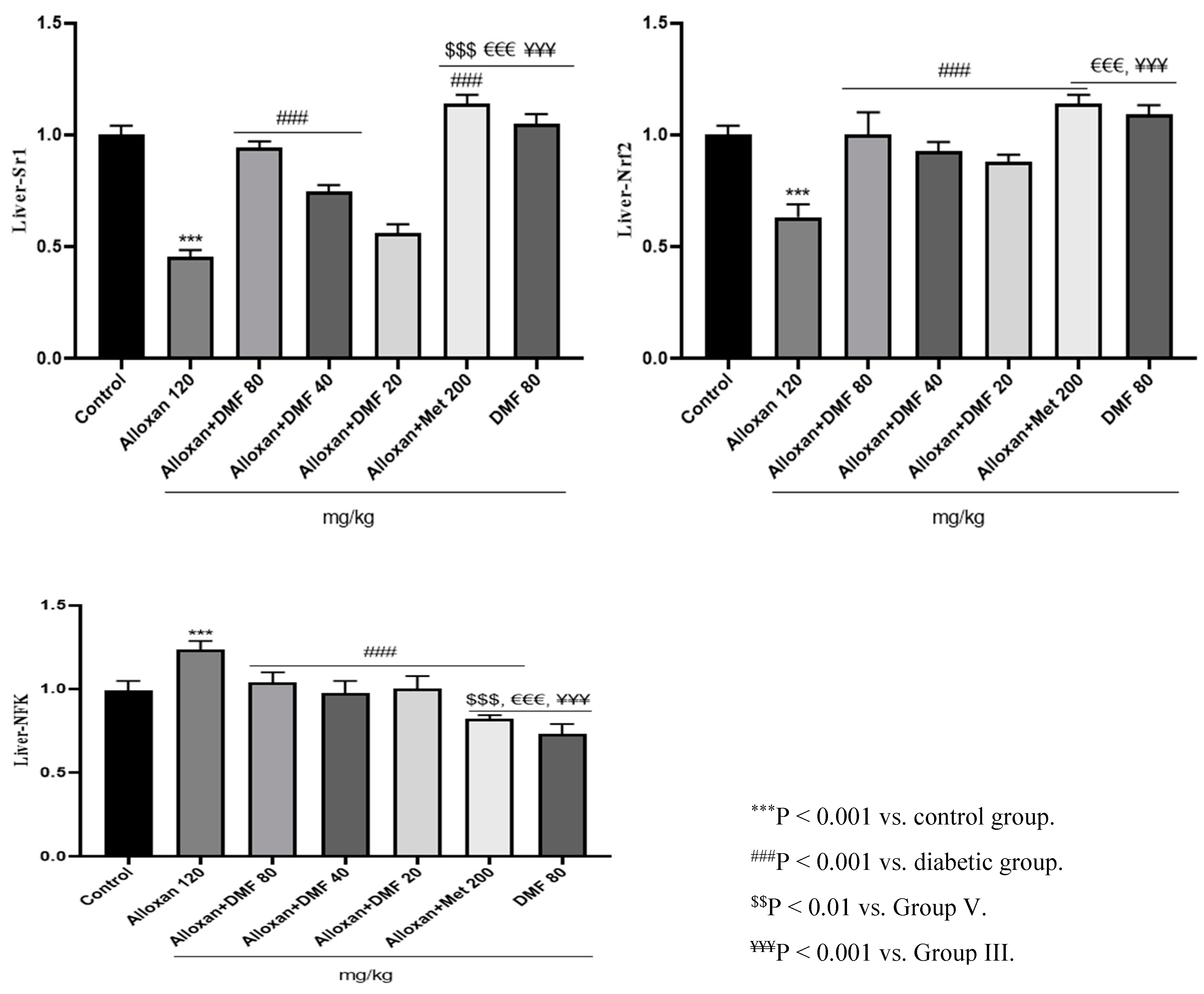

3.4. Effect of DMF on reno-hepato inflammatory genes expression

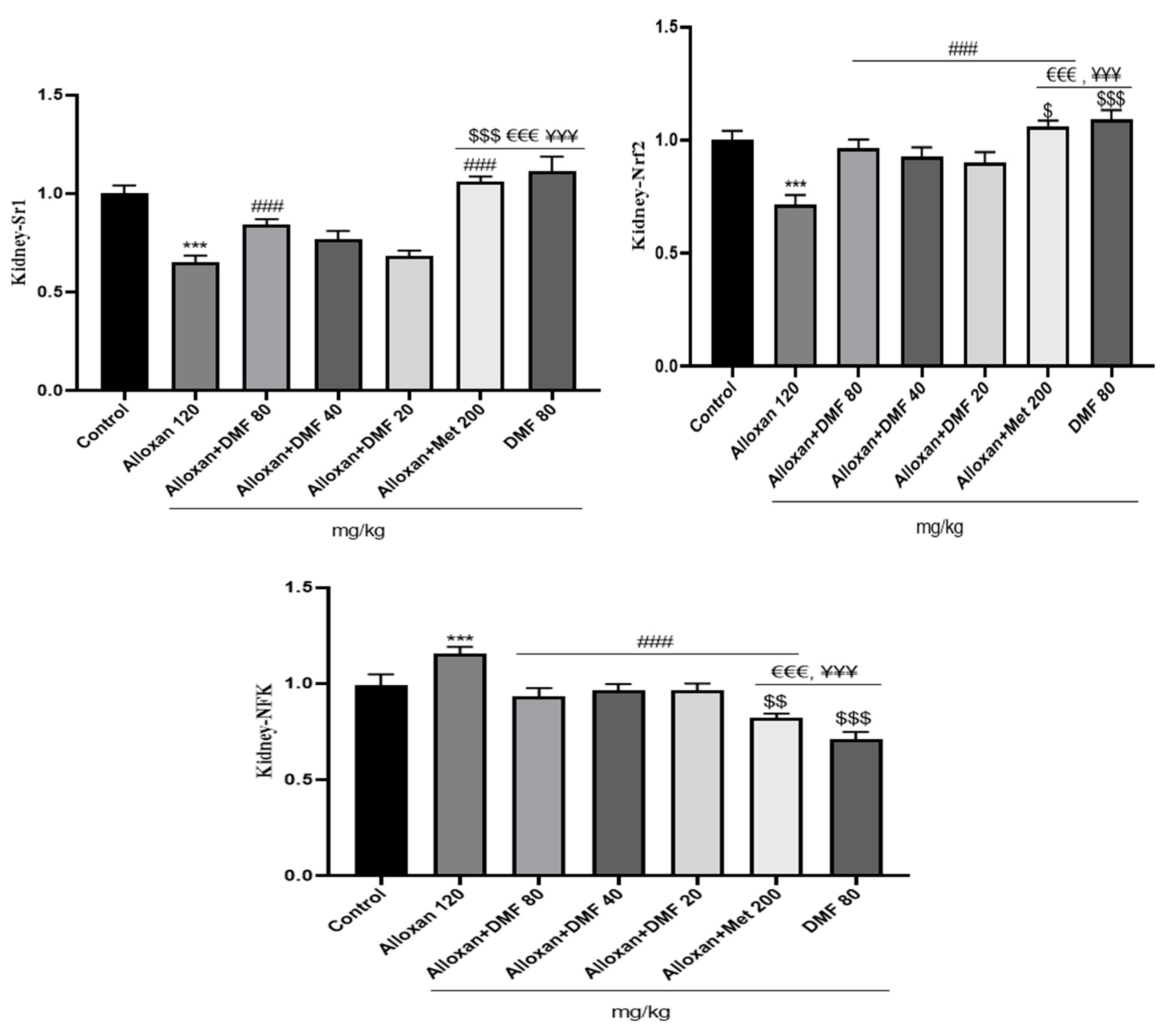

3.4.1. Renal levels of inflammatory genes expression

3.4.2. Hepatic levels of inflammatory genes expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Ethics approval

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

Abbreviations

References

- Fei, Y.; He, Y.; Sun, L.; Chen, J.; Lou, Q.; Bao, L.; Cha, J. The study of diabetes prevalence and related risk factors in Fuyang, a Chinese county under rapid urbanization. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctrie. 2016, 36, 213-219. [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Ding, X.; Putnam, N.; Farej, R.; Singh, R.; Wang, D.; Kuo, S.; Kong, S.X.; Elliott, J.C.; Lott, J.; Herman, W.H. Development of clinical prediction models for renal and cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease using time-varying predictors. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2022,36(5), 108180. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.T.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Bi, C.S.; Song, X.; Zhang, S.T. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is not related to the incidence of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13(11), 14698-14706. [CrossRef]

- Lone, A.; Behl, T.; Kumar, A.; Makkar, R.; Nijhawan, P.; Redhu, S.; Sharma, H.; Jaglan, D.; Goyal, A. Renoprotective potential of dimethyl fumarate in streptozotocin induced diabetic nephropathy in Wistar rats. Obes. Med. 2020, 18, 100237. [CrossRef]

- Oltean, S.; Coward, R.; Collino, M.; Baelde, H. Diabetic nephropathy: novel molecular mechanisms and therapeutic avenues. Biomed Res. Int. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Li, Y.; Cheng, B.; Zhou, T.; Gao, Y. Influence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on the occurrence and severity of chronic kidney disease. J. clin. transl. hepatol. 2020, 10(1), 164. [CrossRef]

- Adiga, U.S.; Malawadi, B.N. Association of diabetic nephropathy and liver disorders. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 2016, 10(10), BC05.

- Dubey, S.; Yadav, C.; Bajpeyee, A.; Singh, M.P. Effect of Pleurotus fossulatus aqueous extract on biochemical properties of liver and kidney in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020, 3035-3046. [CrossRef]

- Amin, FM.; Abdelaziz, R.R.; Hamed, M.F.; Nader, M.A.; Shehatou, G.S. Dimethyl fumarate ameliorates diabetes-associated vascular complications through ROS-TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117887. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Rajesh, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, L. Protection by dimethyl fumarate against diabetic cardiomyopathy in type 1 diabetic mice likely via activation of nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 287, 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Wrona, D, Majkutewicz, I, Świątek, G, Dunacka, J, Grembecka, B, Glac, W. Dimethyl fumarate as the peripheral blood inflammatory mediators inhibitor in prevention of streptozotocin-induced neuroinflammation in aged rats. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 33-52. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, F.; Li, H.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, H. Dimethyl fumarate accelerates wound healing under diabetic conditions. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 61(4), 163-172. [CrossRef]

- Mostafavinia, A.; Amini, A.; Ghorishi, S.K.; Pouriran, R.; Bayat, M. The effects of dosage and the routes of administrations of streptozotocin and alloxan on induction rate of typel diabetes mellitus and mortality rate in rats. Lab. Anim. Res. 2016, 32, 160-165.

- Khan, H.A.; Abdelhalim, M.A.K.; Al-Ayed, M.S.; Alhomida, A.S. Effect of gold nanoparticles on glutathione and malondialdehyde levels in liver, lung and heart of rats. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 19(4), 461-464. [CrossRef]

- Levine, RL. Carbonyl assay for determination of oxidatively modified proteins. Meth. Enzymol. 1994, 233, 246-257. [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, J.D.; Gamble, M. Theory and practice of histological techniques. Elsevier health sciences. J. Neuropathol. Exp. 2008, 67, 633.

- Seo, D.H.; Suh, Y.J.; Cho, Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Seo, S.; Hong, S.; Lee, Y.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, E.; Kim, S.H. Advanced liver fibrosis is associated with chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Metab J. 2022, 46(4), 630-639. [CrossRef]

- Jha JC, Banal C. Chow B.S, Cooper, ME, Jandeleit-Dahm, K. Diabetes and kidney disease: role of oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016, 25(12), 657-684. [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Mantovani, A.; Pichiri, I.; Mingolla, L.; Cavalieri, V.; Mantovani, W.; Pancheri, S.; Trombetta, M.; Zoppini, G.; Chonchol, M.; Byrne CD. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased incidence of chronic kidney disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2014, 37(6), 1729-1736. [CrossRef]

- Subba, R.; Ahmad, M.H.; Ghosh, B.; Mondal, A.C. Targeting NRF2 in Type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression: Efficacy of natural and synthetic compounds. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 925, 174993. [CrossRef]

- Trimeche, A.; Selmi, Y.; Slama, B.; Hazar, I.; Achour, A. Effect of protein restriction on renal function and nutritional status of type 1 diabetes at the stage of renal impairment. Tunis. Med. 2013, 91(2), 117-122.

- Laselva, O.; Allegretta, C.; Di Gioia, S.; Avolio, C.; Conese, M. Anti-Inflammatory and anti-oxidant effect of dimethyl fumarate in cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cells. Cells. 2021, 10(8), 2132. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Song, M.Y.; Song, E.K.; Kim, E.K.; Moon, W.S.; Han, M.K.; Park, J.W.; Kwon, K.B.; Park, B.H. Overexpression of SIRT1 protects pancreatic β-cells against cytokine toxicity by suppressing the nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway. Diabetes. 2009, 58(2), 344-351.

- Banks, A.S.; Kon, N.; Knight, C.; Matsumoto, M.; Gutiérrez-Juárez, R.; Rossetti, L.; Gu, W.; Accili, D. SirT1 gain of function increases energy efficiency and prevents diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2008, 8(4), 333-341. [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, J.; Drori S.; Uldry, M.; Silvaggi, J.M.; Rhee, J.; Jäger, S.; Handschin, C.; Zheng, K.; Lin, J.; Yang, W.; Simon, D.K. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006, 127(2), 397-408. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, B.K.; Park, J.Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, S.U. Evolution of liver fibrosis and steatosis markers in patients with type 2 diabetes after metformin treatment for 2 years. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2021, 35(1), 107747. [CrossRef]

- Nour, O.A.; Shehatou, G.S.; Rahim, M.A.; El-Awady, M.S.; Suddek, G.M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of dimethyl fumarate in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Egypt. j. basic appl. sci. 2017, 4(3), 153-159. [CrossRef]

| Primer | Sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Forward Reverse |

AGGGTCTGGGCCATAGAACT CCACCACGCTCTTCTGTCTAC |

| IL-6 | Forward Reverse |

AGACTTCCATCCAGTTGCCT CATTTCCACGATTTCCCAGAGA´ |

| NF-κB | Forward Reverse |

AGCCACAGAGATGGAGGAGTTG GGATGTCAGCACCAGCCTTTAG |

| Sirt1 | Forward Reverse |

AGCTCCTTGGAGACTGCGAT´ ATGAAGAGGTGTTGGTGGCA |

| Nrf2 | Forward Reverse |

CACCATGGGAATGGACTTGGAGCTGCC CTAGTTTTTCTTAACATCTGGCTTCTTAC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).