1. Introduction

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is the most common and complex presentation of food allergy in early childhood. 1–4 Cow’s milk allergy can be divided into IgE and non-IgE mediated forms of food allergy. Non-IgE mediated CMA is again classified into the food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), eosinophilic gastro-intestinal disorders, food protein induced proctocolitis5 and mild to moderate non-IgE mediated food allergies.4,6,7 IgE mediated CMA is diagnosed based on a combination of clinical history, specific IgE tests/skin prick tests and oral food challenges when required.5 CMA related FPIES are diagnosed by a clinical history and/or oral food challenge.8 Eosinophilic gastro-intestinal disorders are diagnosed by performing endoscopies followed by cow’s milk avoidance, reintroductions and follow-up endoscopies.9 Food protein induced proctocolitis and cow’s milk induced enteropathies are mainly diagnosed based on clinical features and the patient’s medical history and cow’s milk avoidance.10

Mild to moderate non-IgE mediated CMA have been described for the first time in 2014 by a group of clinicians from the United Kingdom.7 The authors suggested an algorithm for the diagnosis and management of mild to moderate non-IgE mediated CMA. Infants with mild to moderate non-IgE mediated CMA present with a combination of skin, gastrointestinal and sometimes respiratory symptoms in the absence of growth faltering and severe symptoms. The diagnosis is based on a clinical history, removal of cow’s milk protein and rechallenge of cow’s milk upon symptom resolution (usually 2- 4 weeks after removal of cow’s milk protein). After a period of avoidance, cow’s milk can be reintroduced at home in a sequential manner starting from lowest dose and allergenicity to highest dose and allergenicity over a time period, which can be individualized for each case.

The original ladder for use in children with mild to moderate non-IgE mediated CMA, was developed by a group of UK health care professionals calculating the amount and cooking temperature of 12 foods commonly consumed in the UK (malted milk biscuits, digestive biscuits, cupcakes/mini muffins, scotch pancakes, shepherd’s pie, lasagna, pizza, milk chocolate, yogurt, cheese, sterilized and pasteurized milk).7 It soon became apparent that the ladder was used world-wide and an amended version of the ladder, using more internationally accepted foods and only 6 steps was developed (biscuits/cookies, muffins, pancakes, cheese, yogurt, and pasteurized milk).6 Yet, it was clear that the foods in the ladder did not represent food preferences of all cultures.

Data from UK has shown that mothers were confused about the steps in the milk ladder and concerned about the limited number of foods that might not necessarily reflect the child’s food preferences which lead to the adaptation of the original ladder.11 A recent rostrum article, highlights the fact that milk ladders are increasingly being used in the care of children with IgE mediated food allergy.12 This rostrum further emphasizes the importance of milk ladders being simple with a limited number of foods per step, culturally and age appropriate, preferably healthy, along with attached recipes including the time and temperature of heating and also the milk protein content to be specified. The levels of protein present in the final product should be tested 12.

Indian food is different from the rest of the world, not only in taste, but also in cooking methods and ingredients used. It reflects a perfect blend of various cultures and ages. Kashmiri dishes reflect strong central Asian influences with rice as the staple diet compared to wheat as the staple diet in the rest of Northern India. Western Indian foods contain a range of lentil dishes and pickles or preserves. Food intake in Eastern India is dominated by fish and rice dishes. Southern Indian food also often contains fish as an ingredient as well as lamb, prawns and coconut. However, central to all Indian cooking is sweet, milky desserts. We have therefore considered the sugar and fat content of foods, but included some foods higher in fat and sugar content, to adhere to the Indian palate. The study aimed to, 1) Develop a milk ladder based on food cultures in India, 2) Consider and be mindful of the sugar and fat content in the Indian foods included in the ladder and 3) Calculate and test the amount of cooked milk protein in different Indian foods included in the ladder.

2. Materials and Methods

2.2. Initial development of the Indian Milk ladder

A list of common foods reflecting the different cultures in India was drawn up, analyzed for their milk protein content, temperature and timing of heating, sugar and fat content (

Table 1). The first list of foods included Maida Diamond Biscuits, Gulab jamoon, Ragi/Poha Dosa, Halwa, Rava Idli, Rice/Sago/Semolina pudding, Paneer, Scrambled egg with milk and Rava Laddoo. After discussion of the fat, sugar and allergen content, the milk ladder was adapted (

Table 1). Foods which are prevalent across different geographical locations and cultures were included. The initial/working Indian Milk Ladder was designed by consensus of working group.

Table 1.

Milk ladder built by Consensus.

Table 1.

Milk ladder built by Consensus.

| Step |

Food |

Milk/ Serving |

Milk protein/ Serving |

Cooking

Temperature (0C)

|

Cooking Time |

| Step 1 & 2: Gradually increasing amount of Protein with increasing cooking time |

| Step 1 |

Marie Biscuit |

|

0.050 g |

180 |

15 min |

| Maida Diamond Biscuits |

1.25 ml |

0.040 g |

180 |

15 min |

| Step 2 |

Milk Cookie |

1.8 g milk powder |

0.37 g |

180 |

10 min |

| |

Halwa |

25 ml |

0.75 g |

Boiled |

25 min |

| Ragi Sari/Kanji (with milk) |

25 ml |

0.75 g |

Boiled |

30 min |

| Step 3: Slightly lower amount of protein but heating time lower too |

| STEP 3 |

Ragi dosa |

21 ml |

0.74 g |

Fry |

2-4 min |

| Rava idli |

20 ml |

0.70 g |

Steam |

15 min |

| Step 4: Increased Protein and Increased Cooking time too |

Step 4

|

Gulab jamoon (dry) |

8.3 g milk powder |

2.15 g |

Boiled+ Fry |

20 min |

| Rasagullah |

100 ml |

3.5 g |

Boiled |

30 min |

| Rice Kheer |

100 ml |

3.5 g |

Boiled |

30 min |

| Step 5: No Cooking |

Step 5

|

Paneer |

|

3.7 g

|

No cooking

But through cheese making process |

| Shrikand or Yoghurt |

180 ml |

6.0 |

No cooking |

| Step 6: Pasteurized Milk |

| Step 6 |

Milk |

¼ cup |

2.17 g |

|

|

| ½ cup |

4.34 g |

|

| 1 cup |

8.68 g |

|

2.3. Testing of the milk protein content of food included in the milk ladder

To rationalize the steps of Indian Milk Ladder, we first calculated and then tested the content of milk protein in the different Indian foods included in the ladder. Food items were cooked freshly as per the recipe (detailed in Supplementary Material S1 and S2) which specified the ingredients, method of cooking and amount of milk/milk product to be added.

Kjeldahl nitrogen analysis, Association of Official Analytical Chemists [AOAC] methods13 and ELISA14 were used to determine the cooked milk protein content. Details of ELISA kits are as follows: RIDASCREEN®FAST Milk (Art No R4652), R-Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany, Lot Number: 25470 Expiry: 11/2021.

Total nitrogen analysis by Kjeldahl method, the international reference method for determining protein in milk and milk-based products due to its high precision and good reproducibility indirectly measures protein content by determining the total nitrogen content of the milk product. Total nitrogen is converted into percentage protein and accounts for the nitrogen content of the average amino acid composition present in the milk.13,15 For milk derived products tested, including Paneer, Cheese, Yogurt, Rasagulla, and Shrikhand, the protein content directly represented the total milk protein and AOAC 2001.1116 method was used. For products containing milk along with other ingredients (Gajar Halwa, Gulab jamoon, Ragi Sari, Rice Kheer), due to the ingredient variability and presence of protein sources other than milk, the milk proteins were determined as casein and albumin content per AOAC 939.0217 method.

The AOAC method is not recommended to determine milk protein content of samples which are presumed to contain less than 0.1% of milk proteins. The sandwich enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) for the quantitative determination of milk protein in food was used to determine milk protein14 for the following: Biscuit, Maida biscuit, Cookie, Pan Cake, Ragi Dosa, Rava Idli, Mufffin. The ELISA method uses antibodies against caseins and Beta-lactoglobulins and thus it is a direct measure of milk protein content in the sample.

Milk protein was estimated on three different samples at three different times by the methods described above. The average of three values was taken as the final result. Mean and standard deviations were calculated.

3. Results

3.1.1. Expert Consensus

The initial milk ladder was designed by consensus by expert committee by calculating the amount of milk in food and accounting for the cooking temperature and duration (

Table 1). The principle used to design each step of the ladder is outlined:

Step 1 & 2: Gradually increasing amount of protein and cooking time

Step 3: Slightly lower amount of protein and heating

Step 4: Increased protein with increased cooking time

Step 5: No cooking

Step 6: Pasteurized milk

3.1.2. Validation of milk protein in selected foods

Following expert consensus, the cooked milk protein content of foods making up the ladder was analyzed in the laboratory as described. Cooked Milk protein content of analyzed foods are outlined in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Cooked Milk protein content of foods in the Indian Milk Ladder (in grams/100 grams of food).

Table 2.

Cooked Milk protein content of foods in the Indian Milk Ladder (in grams/100 grams of food).

| Sample Name |

Method |

Reading 1 |

Reading 2 |

Reading 3 |

Mean |

SD |

| Biscuit |

ELISA |

0.005 |

0.005 |

0.005 |

0.005 |

0 |

| Maida biscuits |

ELISA |

0.006 |

0.005 |

0.006 |

0.005 |

0.0005 |

| Shrikhand |

AOAC 939.02 |

0.28 |

0.28 |

0.28 |

0.28 |

0 |

| Cookie |

ELISA |

0.32 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

0.36 |

0.0346 |

| Pan cake |

ELISA |

0.34 |

0.35 |

0.37 |

0.353 |

0.0152 |

| Gajar Halwa |

AOAC 939.02 |

0.41 |

0.41 |

0.41 |

0.41 |

0 |

| Gulabjamun |

AOAC 939.02 |

1.23 |

1.23 |

1.23 |

1.23 |

0 |

| Rasagulla |

AOAC 2001.11 |

2.49 |

2.67 |

2.49 |

2.55 |

0.1039 |

| Ragi sari |

AOAC 939.02 |

2.73 |

2.59 |

2.73 |

2.68 |

0.0808 |

| Rice kheer |

AOAC 939.02 |

2.87 |

2.87 |

2.73 |

2.82 |

0.0808 |

| Ragi Dosa |

ELISA |

2.92 |

2.997 |

2.87 |

2.92 |

0.0639 |

| Rava idli |

ELISA |

3.12 |

3.08 |

3.2 |

3.13 |

0.0611 |

| Muffin |

ELISA |

4.63 |

4.08 |

4.36 |

4.35 |

0.2750 |

| Yogurt |

AOAC 2001.11 |

7.33 |

7.21 |

7.16 |

7.23 |

0.0873 |

| Cheese |

AOAC 2001.11 |

21.15 |

21.28 |

21.1 |

21.17 |

0.0929 |

| Paneer |

AOAC 2001.11 |

21.37 |

21.49 |

21.49 |

21.45 |

0.0692 |

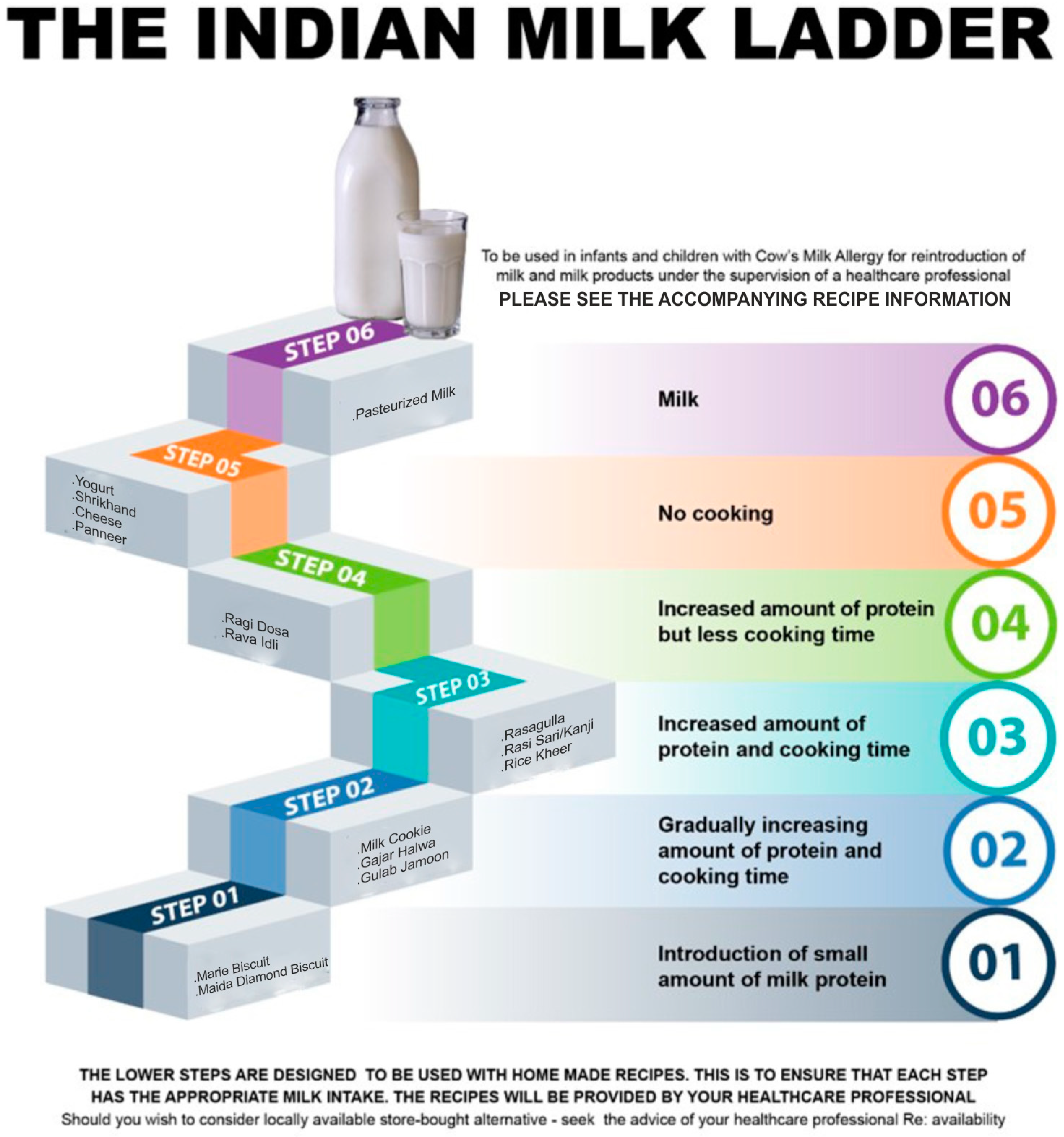

3.1.3. Finalization of the Indian Milk Ladder

The results obtained by laboratory milk protein estimation were compared with that of Milk ladder which was originally designed by consensus. The final milk ladder was prepared by rearranging the food products in the ladder according to the amount of protein present in the food item as determined by laboratory testing. The ladder contains 6 steps (

Table 3 and

Figure 1). Alternative Indian food to reflect cultural differences is provided in each step.

Table 3.

The final Indian Milk Ladder.

Table 3.

The final Indian Milk Ladder.

| STEP |

Food |

Cooked Milk Protein content (g/100 g) |

Recommended Portion per serving |

Cooking Temperature (0C) |

Cooking Time |

| Step 1: Introduction of small amount of milk Protein |

| Step 1 |

Marie Biscuit |

0.005 |

½ Biscuit to start with & build up gradually |

Commercial Preparation

|

| Maida Dimond Biscuit |

0.006 |

180 |

15 min |

| Step 2: Gradually increasing amount of protein and cooking time |

| Step 2 |

Milk Cookie |

0.35 |

Start with ¼ portion & increase gradually |

180 |

12 min |

| Gajar Halwa |

0.410 |

Boil |

25 min |

| Gulab Jamoon (dry) |

1.230 |

Boil + fry |

20+5 min |

| Step 3: Increasing amount of protein and cooking time |

| Step 3 |

Rasgulla |

2.550 |

Start with ¼ portion increase gradually |

Boil |

30 min |

| Ragi Sari/Kanji |

2.686 |

Boil |

30 min |

| Rice Kheer |

2.823 |

Boil |

30 min |

| Step 4: increasing amount of protein but less cooking time |

| Step 4 |

Ragi dosa |

2.929 |

Start with ¼ portion increase gradually |

Fry |

2-4 min |

| |

Rava idli |

3.120 |

Steam |

15 min |

| Step 5: No cooking |

| Step 5 |

Yoghurt |

7.330 |

Start with ¼ portion and increase gradually |

No Cooking |

Through Cheese making |

| Srikhand |

8.680 |

No Cooking |

|

| Cheese |

21.28 |

-- |

-- |

| Paneer |

21.49 |

|

|

| Step 6: Milk |

| Step 6 |

Pasteurized Milk |

|

Start with ¼ cup and increase gradually |

|

|

Figure 1.

The Indian Milk Ladder.

Figure 1.

The Indian Milk Ladder.

4. Discussion

The gradual reintroduction of baked milk products and milk in children with non-IgE mediated CMA which is done at home is called the “Milk Ladder”. The milk ladder is based on the knowledge that the addition of baked milk to the diet of children tolerating such foods appears to accelerate the development of milk tolerance compared with strict avoidance.18,19 We developed the first milk ladder based on unique features of Indian food habits through consensus of Indian experts along with international collaboration. This is the world’s first milk ladder that quantifies the amount of milk protein per step.

Heat treatment has long been recognized to have the potential to alter allergenicity of proteins. Now it is well recognized that the processing of food proteins alters their structure and potential to induce allergy.20,21 The allergenic characteristics of a protein are determined by the epitopes formed by the sequential amino acids and epitopes arising from the three-dimensional shape of the protein, called conformational epitopes. Heating causes a loss of the conformational epitopes and largely preserves the sequential epitopes.22

It is generally accepted that infants with a proven diagnosis of cow’s milk allergy should remain on a cow’s milk protein free diet until 9–12 months of age and for at least 6 months23 prior to re-introduction of cow’s milk into their diets. However, up to 90% of children with CMA may tolerate baked milk containing foods such as muffins and cupcakes.24 The inclusion of baked milk products in children’s diet is suggested to accelerate the development of tolerance to unheated milk compared to a strict milk avoidance approach. A significant increase in IgG4 against milk casein in children who are tolerant to baked milk, has been reported, similar to those treated with milk oral immunotherapy.25,26 Moreover, the consumption of baked milk is suggested to enhance the quality of life by removing unnecessary dietary restrictions and to change the natural history of CMA by promoting the tolerance acquisition to regular cow’s milk.18,27

All milk proteins have potential to act as allergens. In the current study, we designed the first milk ladder in the Indian subcontinent considering the cultural diversity in India, the amount of milk protein in the food item, the time/duration and temperature of heating, as well as the effect of other ingredients on the milk protein. The cooked milk protein in each chosen food substance was analyzed by standard laboratory methods. We estimated only total milk protein content of foods as we know that both casein and whey are equally implicated in the pathogenesis of milk allergy.28,29 In children, major milk allergens are suggested to be caseins, β-lactoglobulin and α-lactalbumin.30 The calculated protein content of foods in Step 1, Step 2, Step 3 and Step 4 did not corelate well with laboratory estimation of milk protein. Whereas foods in Step 5 (milk-derived products) of the Milk Ladder corelated well with the laboratory estimation. Based on the laboratory results we rearranged the foods of milk ladder in step 2, step 3 and step 4. As the foods in step 2, 3 and 4 contained other ingredients along with significant amount of milk, the interference of matrix would have contributed to this variation. Previous studies have shown that incorporating other substances (matrix) along with milk while cooking might promote the formation of complex milk–food components.31 We hypothesize these milk-food components may lead to interference in laboratory estimation of milk protein leading on to a difference between calculated and estimated milk protein content in cooked foods. It is also known that milk food components induce a modulation of the immunoreactivity towards milk allergens.31 Based on the results of milk protein content of different food substances the ladder was re-designed by arranging food items in increasing order of protein content.

It is generally accepted that the ladder approach can be used safely in children with mild to moderate non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy such as proctocolitis. It is however also known that the milk ladder is being used in children with IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy outside of the clinical setting.11 A recent article12 suggests that the milk ladder can be used safely in individuals with 1) non-IgE mediated allergy (excluding FPIES), 2) IgE-mediated food allergy with prior mild, non-anaphylactic reactions, 3) no diagnosis of asthma individuals, but considered for individuals with stable, treated asthma, 4) the ability to understand and comply with the instructions provided, 5) high previous reaction threshold 6) low or decreasing skin prick test wheal or serum specific-IgE levels 6) Younger patients or individuals of any age with limited co-existing allergies. However, because we are employing IML for home-based re-introduction, we strongly advise that it be used only for children with non-IgE mediated milk allergies.

One limitation of the study is that we only measured total milk protein content and not whey and casein fractions. Future analysis should include measuring the whey and casein fractions of baked and processed milk products.

5. Conclusions

This is the first ever attempt to design a milk ladder taking into account cultural food preferences such as foods consumed in India and elsewhere. We have developed a milk ladder with clear instructions for the use in cow’s milk allergic children. This is the first ladder that provides information on timing and temperature of cooking, and validated milk protein content.

We believe the “The Indian Milk Ladder” will be a very helpful tool for the Pediatricians looking after children with CMA and also for parents of such children worldwide, particularly clinicians who are not very well informed regarding Indian foods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Somashekara Hosaagrahara Ramakrishna: Conceptualization (lead); original draft (lead); data curation; methodology(lead); writing – original draft preparation. Neil Shah: Conceptualization (lead); methodology(lead); review and editing (equal). Bhaswati C Acharyya: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing – original draft (supporting); Writing – review and editing (equal). Emmany Durairaj: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing – original draft for recipes (lead). Lalit Verma: Writing – Conceptualization (supporting); original draft (supporting); Writing – review and editing (equal). Srinivas Sankaranarayanan: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing – review and editing (equal). Nishant Wadhwa: Conceptualization (supporting); Writing – review and editing (equal). Carina Venter: Conceptualization (lead); original draft (lead); data curation; methodology(lead); writing – review and editing (equal).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Sarath Gopalan, Senior Pediatric Gastroenterologist and Director Medical Affairs, Reckitt IFCN South Asia for the constant encouragement, throughout the initiative. Reckitt India (Mead Johnson Nutrition) for facilitating laboratory testing and guidance regarding identifying the appropriate certified laboratory testing facility (Mr. Anoop Tiwari). Microchem Silliker Private limited, Mumbai, India for the actual laboratory estimation of total milk protein in the food items constituting the ladder (Dr. Bappa Ghosh, Dr. Trupti Pawar and Mr. Rakesh Yadav).

Conflicts of Interest disclosure

Dr. Venter reports grants from Reckitt Benckiser, Food Allergy Research and Education, National Peanut Board; personal fees from Reckitt Benckiser, Nestle Nutrition Institute, Danone, Abbott Nutrition, Else Nutrition, and Before Brands. Dr. Neil Shah reports grants from Reckitt Nutrition. All other authors have no COI to declare.

References

- Muraro A, Werfel T, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, et al. EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines: diagnosis and management of food allergy. Allergy 2014; 69:1008-25. [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi A, Schünemann HJ, Brozek J, et al. Diagnosis and Rationale for Action Against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA): a summary report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6):1119-28.e12. [CrossRef]

- Luyt D, Ball H, Makwana N, et al. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2014; 44:642-72. [CrossRef]

- Fox A, Brown T, Walsh J, et al. An update to the Milk Allergy in Primary Care guideline. Clin Transl Allergy. 2019; 9:40. Published 2019 Aug 12. [CrossRef]

- Ball HB, Luyt D. Home-based cow’s milk reintroduction using a milk ladder in children less than 3 years old with IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49(6):911-920. [CrossRef]

- Venter C, Brown T, Meyer R, et al. Better recognition, diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy in infancy: iMAP-an international interpretation of the MAP (Milk Allergy in Primary Care) guideline [published correction appears in Clin Transl Allergy. 2018 Jan 25; 8:4]. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017; 7:26. [CrossRef]

- Venter C, Brown T, Shah N, Walsh J, Fox AT. Diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy in infancy - a UK primary care practical guide. Clin Transl Allergy 2013; 3:23. [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Chehade M, Groetch ME, et al. International consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: Executive summary-Workgroup Report of the Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4):1111-1126.e4. [CrossRef]

- Cianferoni A, Shuker M, Brown-Whitehorn T, Hunter H, Venter C, Spergel JM. Food avoidance strategies in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49(3):269-284. [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Szajewska H, Lack G. Food allergy and the gut. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(4):241-257. [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulou P, Deligianni E, Dean T, Dewey A, Venter C. Use of baked milk challenges and milk ladders in clinical practice: a worldwide survey of healthcare professionals. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(3):430-434. [CrossRef]

- Venter C, Meyer R, Ebisawa M, Athanasopoulou P, Mack DP. Food allergen ladders: A need for standardization. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(1): e13714. [CrossRef]

- Lynch JM, Barbano DM. Kjeldahl nitrogen analysis as a reference method for protein determination in dairy products. J AOAC Int. 1999;82(6):1389-1398. [CrossRef]

- Ivens KO, Baumert JL, Taylor SL. Commercial Milk Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kit Reactivities to Purified Milk Proteins and Milk-Derived Ingredients. J Food Sci. 2016;81(7): T1871-T1878. [CrossRef]

- Moore JC, DeVries JW, Lipp M, Griffiths JC, Abernethy DR. Total Protein Methods and Their Potential Utility to Reduce the Risk of Food Protein Adulteration. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2010;9(4):330-357. [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. (2012). AOAC Official method 2011.11 Protein (crude) in animal feed, forage (plant tissue), grain and oilseeds. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. Arlington, Vol II, (19th Edition) Chap 4, p.34 AOAC INTERNATIONAL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

- AOAC International. AOAC 939.02 (1939), Protein (milk) in milk chocolate. Kjeldahl method. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. Arlington, Vol II, (19th Edition) Chap 31, p.12 AOAC International, Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

- Kim JS, Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Sicherer SH, Noone S, Moshier EL, Sampson HA. Dietary baked milk accelerates the resolution of cow’s milk allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):125-131.e2. [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Bloom KA, Sicherer SH, et al. Tolerance to extensively heated milk in children with cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2):342-347.e3472. [CrossRef]

- Heppell LM, Cant AJ, Kilshaw PJ. Reduction in the antigenicity of whey proteins by heat treatment: a possible strategy for producing a hypoallergenic infant milk formula. Br J Nutr. 1984;51(1):29-36. [CrossRef]

- Bloom KA, Huang FR, Bencharitiwong R, et al. Effect of heat treatment on milk and egg proteins allergenicity. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25(8):740-746. [CrossRef]

- Upton J, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. The Impact of Baked Egg and Baked Milk Diets on IgE- and Non-IgE-Mediated Allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;55(2):118-138. [CrossRef]

- Vandenplas Y, Koletzko S, Isolauri E, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(10):902-908. [CrossRef]

- Bartnikas LM, Sheehan WJ, Hoffman EB, et al. Predicting food challenge outcomes for baked milk: role of specific IgE and skin prick testing. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109(5):309-313.e1. [CrossRef]

- Lack G. Epidemiologic risks for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(6):1331-1336. [CrossRef]

- Staden U, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Brewe F, Wahn U, Niggemann B, Beyer K. Specific oral tolerance induction in food allergy in children: efficacy and clinical patterns of reaction. Allergy. 2007;62(11):1261-1269. [CrossRef]

- 27. Sackesen C, Altintas DU, Bingol A, et al. Current Trends in Tolerance Induction in Cow’s Milk Allergy: From Passive to Proactive Strategies. Front Pediatr. 2019; 7:372. [CrossRef]

- Hochwallner H, Schulmeister U, Swoboda I, Spitzauer S, Valenta R. Cow’s milk allergy: from allergens to new forms of diagnosis, therapy and prevention. Methods. 2014;66(1):22-33. [CrossRef]

- Bartuzi Z, Cocco RR, Muraro A, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Contribution of Molecular Allergen Analysis in Diagnosis of Milk Allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17(7):46. [CrossRef]

- Lifschitz C, Szajewska H. Cow’s milk allergy: evidence-based diagnosis and management for the practitioner. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(2):141-150. [CrossRef]

- Bavaro SL, De Angelis E, Barni S, et al. Modulation of Milk Allergenicity by Baking Milk in Foods: A Proteomic Investigation. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1536. [CrossRef]

- Villa C, Costa J, Oliveira MBPP, Mafra I. Bovine Milk Allergens: A Comprehensive Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2018;17(1):137-164. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).