1. Introduction

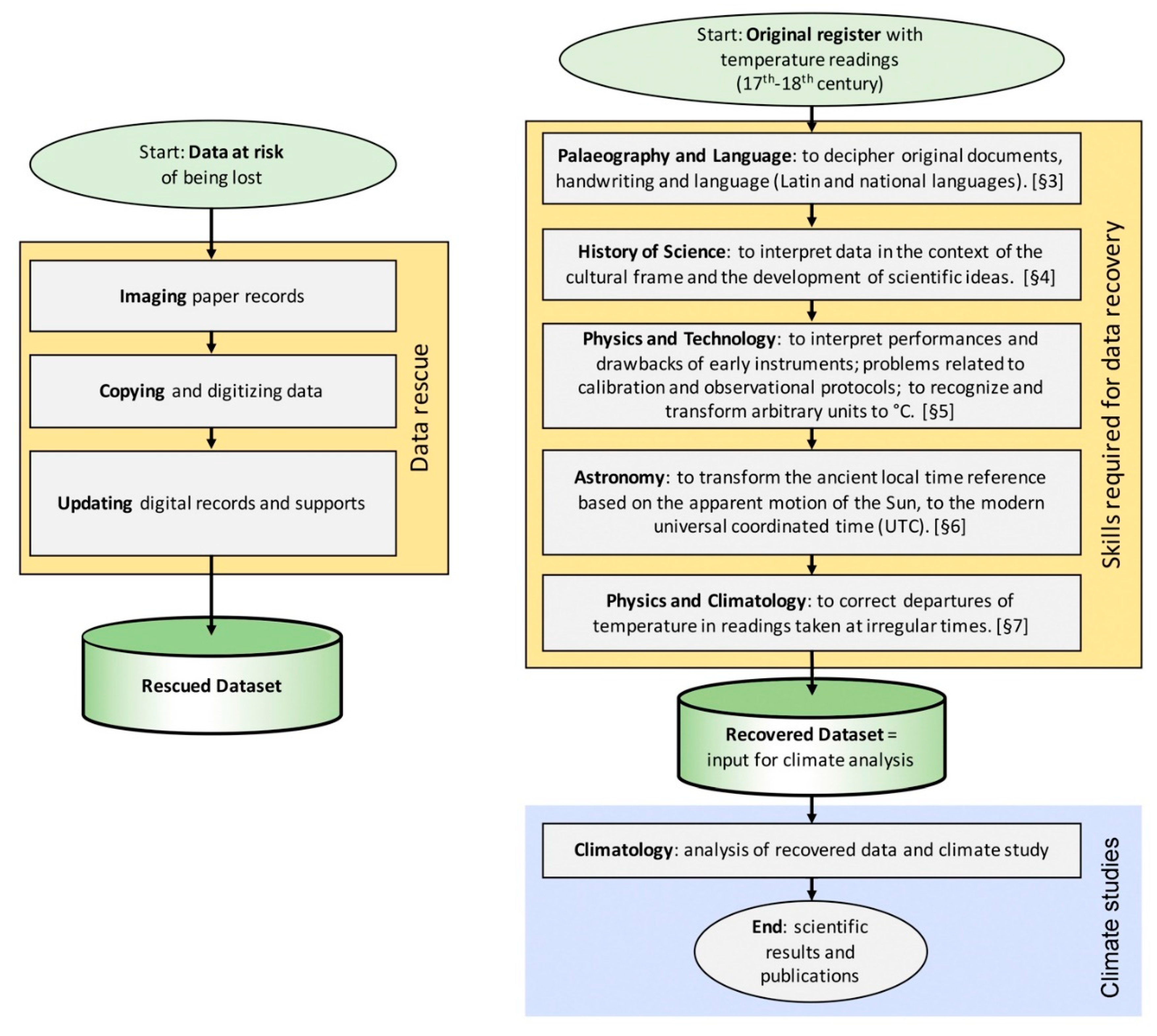

Data Rescue (DARE) is the process of securing data at risk of being lost due to deterioration, obsolescence of the storage media or other factors, and ensuring that data are freely available to the scientific community [

1]. DARE is finalized to archiving, imaging paper records, copying and digitizing data, updating digital records and supports. This is an ongoing task of World Meteorological Organization (WMO), Copernicus, ECMWF, National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, and other institutions. Guidelines on DARE have been published by WMO [

1]. The DARE activity has been documented by a number of authors focused on partial or global inventories [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In Europe, most rescued data and metadata are after the 1850 [

9], although there is an effort to gather records pre-1850 [

10].

In reality, the year 1873, when the International Meteorological Committee (IMC) was founded, is a turning point for meteorology because after then, meteorological observations were taken by National Services with standard instruments and protocols. In the pioneering period starting from 1641 when the liquid-in-glass thermometer was invented, or 1654 when the earliest records were performed, to 1873, every observer was free to invent, build and use instruments, individual methods, and protocols. Some international Networks, like the one established by the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinand II de' Medici (active 1654-1670), the Royal Society, London (active 1724-1735), and the Societas Meteorologica Palatina, Mannheim (active 1781-1792), contributed to homogenize instruments and practices. In the early period, thermometers differed for measuring principle, linear or non-linear response of thermometric fluids, calibration method, location and exposure (including indoor or outdoor use), reading times, adoption or non-adoption of shields or screens against rain and/or solar radiation. As a result, data changed from observer to observer, and caused records to be hardly comparable between them, or even difficult to interpret.

Another problem of that period is the lack of metadata, because observers thought that the focus was in the result, i.e., the observed values, and these had to be accepted due to the scientific authority of the author, who did not lend himself easily to be criticized or reveal his secrets. Furthermore, anything that seemed obvious or irrelevant to the observer was not mentioned. In most cases, registers of observations, and publications, reported a plenty of data but missed the metadata necessary to interpret them.

The turning point was with the first international agreement and the foundation of IMC in 1873. IMC was the ancestor of WMO, i.e., the specialized agency of the United Nations established in 1950 with 160 Members. Today, meteorological data are taken with instruments having the same characteristics and thresholds, and every observer follows a well-defined protocol established by WMO. The adoption of standard instruments and methods ensures the quality and comparability of all records.

Before the establishment of IMC and WMO, the number of active stations was much lower than at present, and this number decreases going back in time. The early instrumental records (EIR) are difficult to interpret and require many years of work, but are extremely relevant because they constitute our best information about the past climate. EIR are generally handwritten in logs kept in public or private archives. Only some of them have been published. Formally, EIR are intended to represent meteorological observations, but are seen and have been conceived with the eyes and mind of that time. EIR essentially differ from modern meteorological data: e.g., for units, instrument, exposure, shield, number of sub-daily readings, sampling time and so on. To be compared with the modern data, each EIR need a profound study to be deciphered and transformed, as discussed in the following sections.

Originally, the term

recovery was used to get back the use of something that was lost, e.g., to restore lost files from hard disks or other electronic supports. It has then been used in the European project IMPROVE [

11] finalized to recover and publish daily temperature and pressure data from the 18th century taken in seven European sites, with the methodology of assessing protocols for the correction of various biases, including homogenisation. Metadata have been considered as important as data, since they are fundamental not only to correct, make homogeneous and interpret data, but also to distinguish apparent climatic changes due to variations in observational methodology, from real climatic changes. Another IMPROVE aim was to publish the history of each series together with all the original data and metadata, and the final corrected, validated and homogenised series. A CD-ROM was added as an annex, with a detailed explanation of all the steps that were necessary to pass from the original registers to the final series [

12]. In IMPROVE, the term recovery was not a simple rescue operation of copying, digitizing and making publicly available data, but included a methodological study to produce new highly reliable series. Since then, other authors have used this term when recovering EIR.

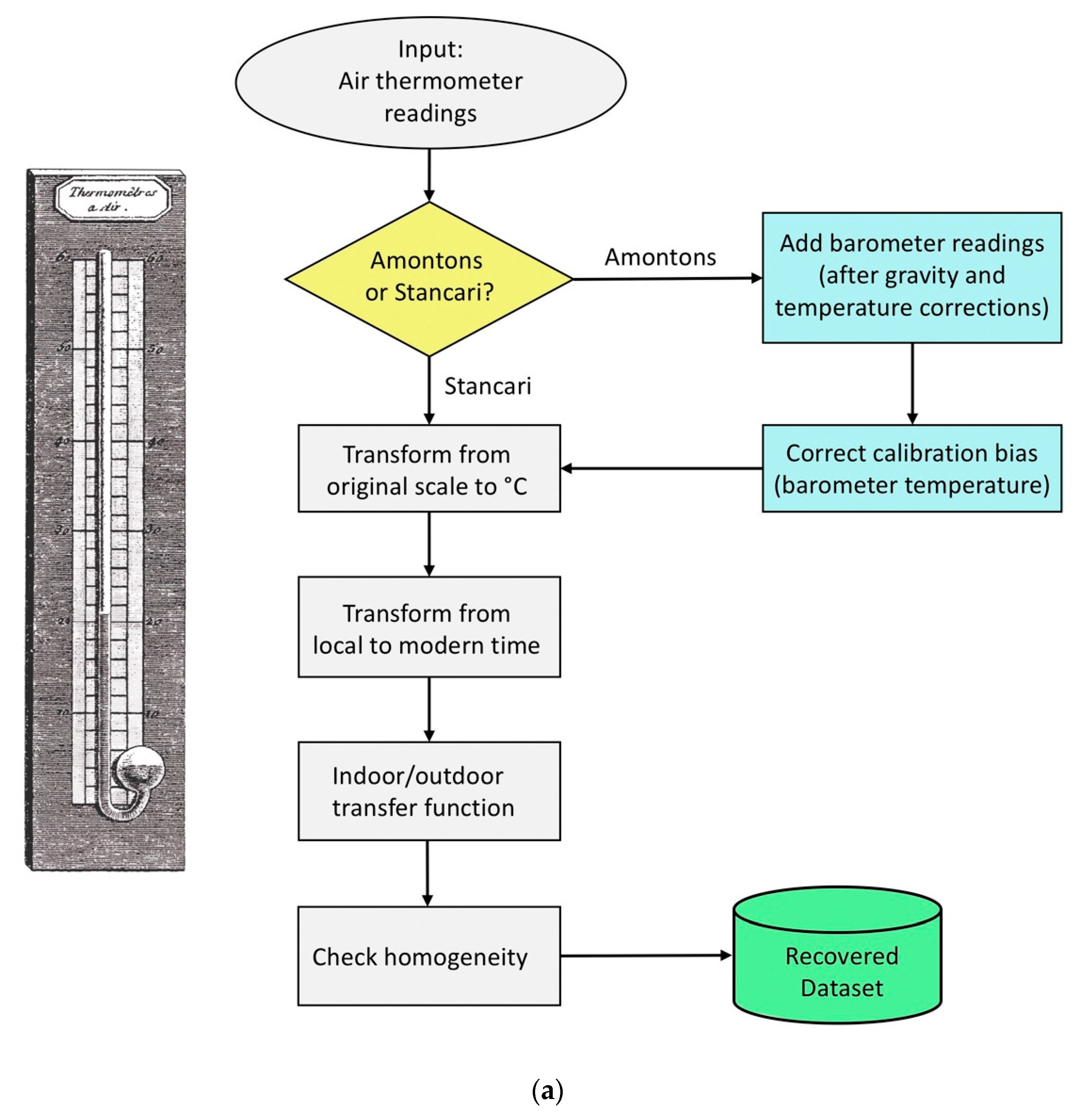

To avoid confusion, in the following the term Data Rescue (DARE) will be used for copying, digitizing or archiving datasets without changing data (

Figure 1a). As opposed, when EIR are studied and deciphered, and the original obscure readings are transformed into a dataset with the standard characteristics of modern ones, the term

recovery will be used (

Figure 1b). The recovered dataset is intended as a set of validated and homogeneous data, ready to be used as input for climate studies.

2. Aims and Structure of the Paper

2.1. Aims

For the complexity of the topics involved, the recovery of EIR requires experts, or specific skills, in a number of disciplines. Some climatologists work with a staff of colleagues with complementary skills (e.g., palaeography, ancient language, history, astronomy); others limit the field of research to what their skills can reach and cannot fully exploit EIR; only a few have a comprehensive background including the basic knowledge of the required disciplines. These difficulties explain why most EIR are still unknown and unexploited.

The purpose of this article is to illustrate the methodology to recover the early temperature records (i.e., 17th, 18th, and the first half of the 19th century), taking advantage of previous studies performed with the earliest Italian thermometric series. Therefore, the article is a review-guide, intended to help the young colleagues who want to tackle the difficult task of data recovery, by explaining the methodologies to afford and solve the various difficulties, taking advantage of clear examples.

The focus is on the operations that should be performed to interpret, correct, and transform the original raw data into a high-quality dataset of temperature, usable for climate studies (i.e., the yellow box in

Figure 1b). The aim is to assist in this task with a comprehensive review focused on the steps grounded on other disciplines with respect to climatology. Sections containing well-known topics will be short, while more detailed explanations will be reserved for the topics typical of other disciplines, likely less familiar to pure climate scientists.

This methodology follows the process that starts immediately after the discovery of an ancient register of weather observations with handwritten notes and numbers that should be transformed into a sound temperature dataset, ready to be used as an input for climate analysis. Study, use and application of the recovered dataset (i.e., cyan box in

Figure 1b) are outside the scope of this paper.

2.2. Structure

The structure of the paper is divided into operative sections (

Figure 1b). The starting point is when a register of EIR is found, and one wants to recover data and metadata.

Section 3. The first difficulty is to read and interpret the original log, data and notes. The handwriting was made in ancient style, discoloured, stained and damaged over time, difficult to read and needs a palaeographer. The language may constitute a problem, because most old documents are in Latin or in the local language, with ancient local, arbitrary or unknown units (An

arbitrary unit is not based on known references and predetermined fixed points, but constitutes a casual scale related to a specific instrument. An

unknown unit is a unit that we do not know because it was not documented by the observer.), or there are additional metadata, e.g., letters exchanged with other scientists from other countries.

Section 4. The history of science is necessary to interpret the original text within the cultural frame of that time and the development of scientific ideas. It helps to interpret, or guess and then verify, the choices of the observer, in terms of instrument, exposure, time of reading and so on.

Section 5. Physics and technology are needed to interpret performances and drawbacks of early instruments, the problems related to calibration and observational protocols, to recognize and transform arbitrary, or unknown units to °C.

Section 6. The time of readings was based on the local Solar Time as it appeared on sundials, based on the solar motion and the local meridian. Since the apparent motion of the Sun does not appear homogeneous to a terrestrial observer, this continuously shifted the time with reference to a modern clock. Furthermore, Italy and some other European Countries continued the Roman and Mediaeval use of the day that began at twilight, not at midnight. The transformation from the ancient time reference to the Coordinated Universal Time divided into Time Zones related to certain reference meridians (as we use today) requires a series of complex calculations. By the way, it is not possible to make a simple table to transform the local apparent Solar time in modern time because the transformation changes with the calendar day, the latitude and longitude of the site.

Section 7. In the early instrumental period, the observations constituted an additional, secondary task of the observers, and the reading times could change by one or more hours. The irregular sampling requires a further correction, not just for the time, but for the temperature change rate, i.e., to calculate the most likely temperature expected if the reading was taken at the scheduled time.

3. Registers, Data and Metadata: Handwriting and Language

Depending on the observer and the conservation, registers can be found ordered, or very messy, stained by water and ink, with the ink of the back page that has crossed the page and is superimposed on the poorly written and hardly legible words, numbers, symbols and letters. Reading documents of the 17th or 18th century requires a specific skill in palaeography for deciphering and interpreting the handwriting, that generally include abbreviations and symbols typical of the period and the cultural environment. The official language of educated people of the time, often university professors or priests, was Latin. Sometimes the local language was used in the registers, with raw annotations and obsolete terms.

Metadata help to identify instruments and observation protocols, and are fundamental for data interpretation. Unfortunately, it is rare to find all the necessary metadata, and the obscure items should be recognized with particular tests, as discussed later. The original registers are fundamental to copy the data from the original source, paying attention to read the data correctly, especially when they have bad handwriting and obscure units.

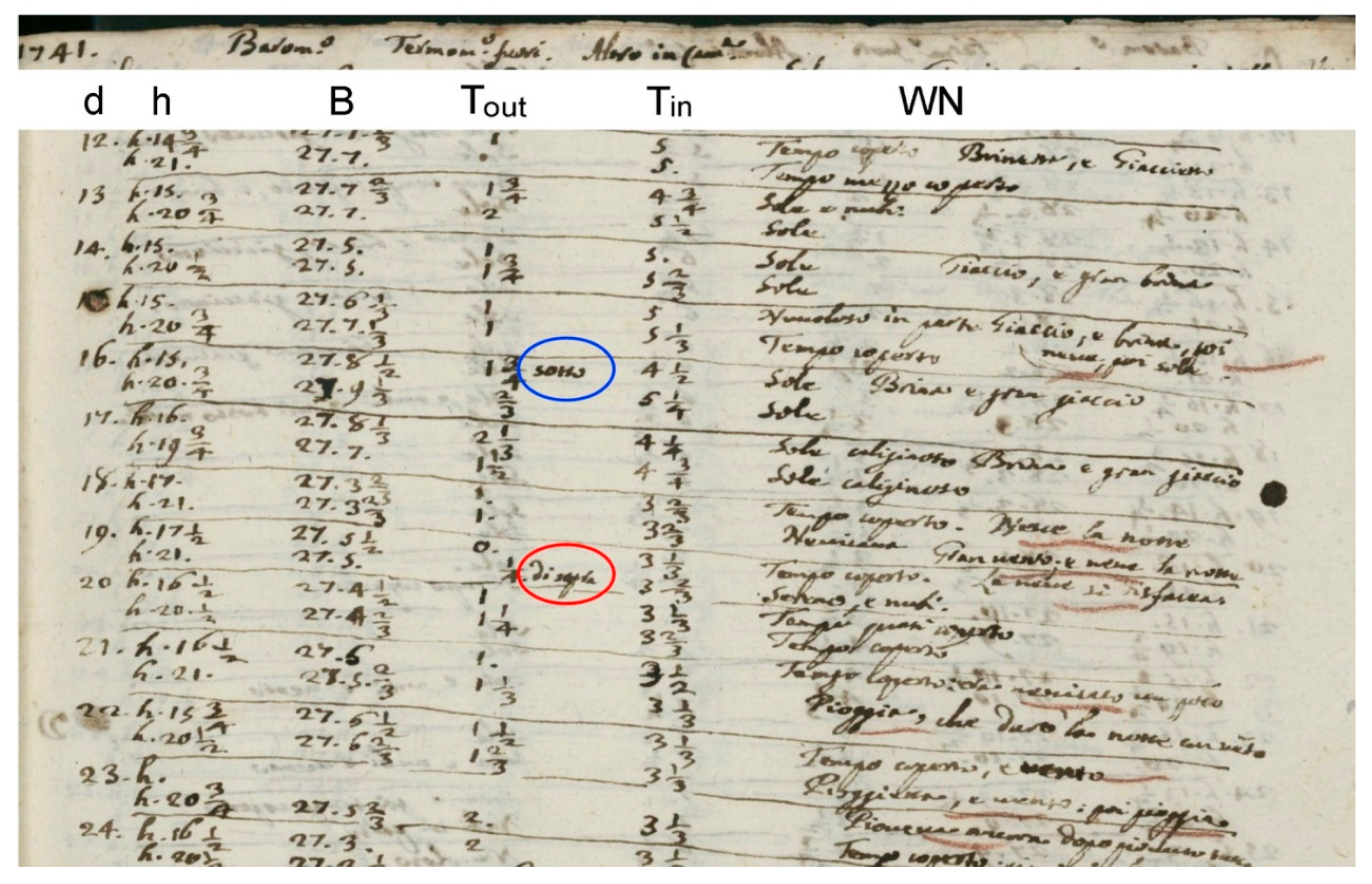

A very popular use that can generate confusion is that the signs ‘-’ and ‘+’ for negative or positive values, or a note ‘below’ or ‘above’ (implying below or above 0°R) were not associated with every number, but were considered a benchmark written only the first time the reading dropped below zero, or rose above it (

Figure 2). After this first minus (or ‘below’), it was considered obvious that all the readings were negative until the signal returned positive and the turning point was marked with a plus (or ‘above’). Sometimes the benchmark was repeated for a few consecutive times, and then interrupted. This practice may be confusing especially when the first minus or plus are hardy readable for water or ink stains, discoloured ink, or other drawbacks typical of early manuscripts. When data are simply rescued, the numbers are just copied. A period of intense cold with the temperature always below zero, e.g., a week, represented by only the first reading below zero and all the subsequent ones without sign, may be misinterpreted and considered positive. A period of intense cold can be mistakenly transformed in a mild period. The interpretation of the writing style is fundamental in the correct data recovery.

Sometimes the original registers have been lost, and it is necessary to rely on printed data, either daily, or monthly or yearly averages. This situation is not the best, but constitutes the only possibility to know early climate data in certain regions.

4. Short History and Technical Problems of Early Thermometers

4.1. The Origins, and the Thermoscope

The history of thermometers has been the object of several studies [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The original idea on which the thermometer is grounded has been attributed to two ancient philosophers, i.e., Philo of Byzantium (2nd or 3rd Century BC) [

25], and Heron of Alexandria (c.10–70 AD) [

26] who invented fountains and other amazing devices driven by water and air. However, when the thermoscope was invented, the books of Philo were unknown, probably because they were written in Greek and Arabic. As opposed, in the second half of the 16th century, the book of Heron,

Spiritalia, was translated from Greek to Latin [

25], then to Italian [

28,

29]. In addition, at the beginning of the 17th century, Della Porta [

30] published a similar fountain. Heron became popular because his book contained detailed explanations, each device with the operating principle and illustrated with a figure.

Galileo Galilei, Sanctorius Santorius and Cornelius Drebbel read these books and were stimulated to build devices where a pocket of air, when is heated, displaces a column of water. Robert Fludd was unable to read the text, but could interpret the drawings. These scholars invented their devices independently from each other, so that the thermoscope was invented several times [

24]. Galileo and Sanctorius gave the most scientific contributions. Galileo started around 1593, and considered the relationships between temperature, pressure and volume. In 1641, the last year of the Galileo’s life, Robert Boyle went to Florence and returned home to study the laws of gases with a replica of a Florentine thermometer. Sanctorius [

31,

32] added a quantitative scale to the instrument to read the ‘

heat’ (that was the old name of temperature) levels, or the ‘

heat’ changes. In 1598, Drebbel applied the principle of the thermoscope to build an astronomical water clock powered by solar energy. Fludd [

33,

34,

35] built solar fountains, applied the principle of the thermoscope to build a gigantic water calendar, and built some thermoscopes similar to Sanctorius.

In the thermoscope, the expansion of the air pocket was determined by both the temperature and the atmospheric pressure that was unknown till 1643, when Evangelista Torricelli and Vincenzo Viviani discovered it. However, it soon became clear that the thermoscope had a problem, i.e., it was not stable for the changes of atmospheric pressure, and was abandoned.

4.2. Liquid-in-glass Thermometers

In Florence, the Grand Duke Ferdinand II, Galileo and the members of the Accademia del Cimento realized that not only the air, but also the liquids change density (and volume) with temperature, and started measuring the density of springs, rivers, spirit beverages and many other liquids. This suggested the idea that a hermetically sealed phial of glass, containing inside a certain amount of alcohol and some air as well, would have caused the expansion of both, but being both enclosed in a fixed volume, the strength of the liquid would prevail over air and the length of the liquid column could be related to the ‘degree of heat’, i.e., the ‘temperature’ as it was named later.

The basic thermometer was the so-called Little Florentine Thermometer (LFT), invented around 1641 [

13,

14,

15,

36,

37,

38]. It was uniquely made of glass, except for the thermometric liquid, so that it could resist to any weather. The scale was composed of 50 enamel bids, and a range that could respond to the cold waters of the Arno River in winter, and the hottest days in summer. The response time was about 5 minutes [

39]. To interpret and make the readings of different thermometers comparable, the Grand Duke ordered to build a large number of instruments, all with exactly the same size and quantity of alcohol, and the scale was fixed by comparison with a reference prototype. Thermometers with different response were rejected. At this point all the LFTs gave comparable readings, and the Grand Duke organized an international Meteorological Network, i.e., the Medici Network, that operated from 1654 to 1670, with thermometer readings every 3-4 hours in Florence and Vallombrosa, and less readings in other stations [

40,

41].

The Florentine Academicians tested various thermometric liquids, including spirit (ethyl alcohol) and quicksilver (mercury). They preferred to use refined alcohol, i.e., the so-called

acquarzente (wine spirit or burning water), that was obtained by distilling grapes twice, until the spirit reached some 80% ABV (alcohol-by-volume). The Academicians, and after them Réaumur, as well as other scientists, preferred spirit to mercury because it expanded six times more, had a lower freezing point, was lighter and, in addition, cheaper. Robert Boyle preferred mercury; Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit in 1709 built alcohol thermometers, but after 1714 he preferred mercury. Isaac Newton used linseed oil, but the oil was soon abandoned because it adhered to the capillary tube and made difficult readings. In Italy, two thermometric liquids were used: spirit (the most popular) and mercury. Spirit had two problems, i.e., the deviation from linearity of spirit depends on the ABV composition; once the thermometer has been built, the deviation of the thermometer depends on how calibration was made, i.e., with two fixed points, or by comparison with a mercury thermometer (

Section 5). Mercury was a good choice because its response is linear and the calibration easy.

4.3. Air Thermometers

The thermoscope was abandoned because readings were biased by the atmospheric pressure. However, the idea of using air as thermometric fluid remained appealing for several reasons: (i) air is the most sensitive fluid to temperature, with volumetric expansion coefficient of 3400·10-6 (1/°C), much greater than ethyl alcohol 1100·10-6 (1/°C) and mercury 180·10-6 (1/°C); (ii) all thermometers could have the same fluid with the same composition, expansion and scale; (iii) air does not freeze; (iv) air is light; (v) air has no cost; (vi) in theory only one calibration point would be sufficient, but in reality two were needed. At the turn between the 17th and the 18th century, two scholars discovered how to solve the pressure drawback.

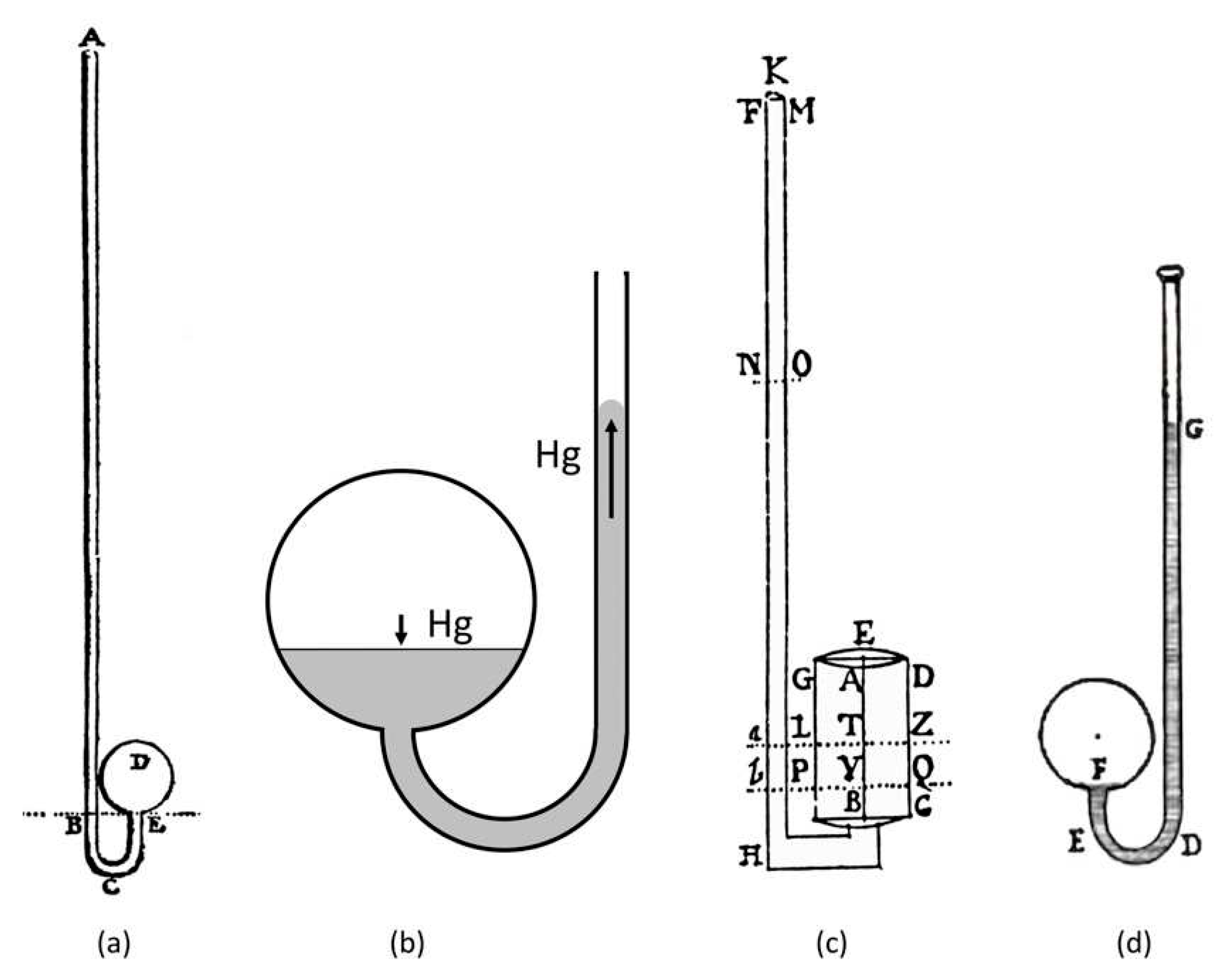

At the beginning of the 18th century, Guillaume Amontons [

42] considered that the atmospheric pressure was counteracting the pressure of the air pocket enclosed in the spherical bulb. Therefore, his solution consisted in adding the height of the barometer column to the height of the thermometric column. Readings of the air thermometer, taken alone, had no meaning, but the sum of the thermometric and barometric readings gave the actual temperature. So, the temperature measurement needed two instruments. This was not a problem for a fixed station, but it could be for field measurements that required to move two delicate instruments. The thermometer was J shaped, with a spherical bulb containing the (compressed) air pocket sealed to the lower end of the J shaped tube, while the upper end of the tube was open (

Figure 3a). A thermometer with open tube obliged to use mercury, because ethyl alcohol is volatile and would have evaporated in a short. In addition, the weight of the mercury increased the reactive spring of air.

The Amontons thermometer had other problems. (i) Depending on the temperature and the pressure in the air pocket, some molecules of water vapour could condense, lowering the reading. (ii) The air pocket was in a spherical bulb, compressed by the column of mercury (i.e., the distance between the upper meniscus on the tube and the free surface of mercury in the bulb). In the air pocket, any change in temperature or pressure displaced a certain volume of mercury that passed from the sphere to the column (

Figure 3b). However, the free surface of the mercury moved up and down in the spherical bulb. This surface constituted a circular cross section with variable radius. Under the same volume change of the gas, a different section of the mercury in the bulb resulted in a different height of the mercury displaced in the column of the capillary tube. Therefore, although this thermometer used linear fluids (i.e., air and mercury), its response was not linear. To avoid this drawback, Giovanni Poleni used a cylindrical bulb: the constant cross section provided a linear response [

43] (

Figure 3c). (iii) The calibration was another crucial item, as discussed later (

Section 5.6). In Italy, the Amontons thermometer was used by Giovanni Poleni in Padua (from 1725 to 1761) and Tommaso Temanza in Venice (from 1751 to 1755).

In the same period, in Bologna, Vittorio Francesco Stancari [

44] considered another approach [

45]. He built exactly the same J shaped glassware with the spherical air pocket on the lower end, but sealed the upper top of the tube without leaving air inside (

Figure 3d). Therefore, the upper part of the tube was empty, except for the vapour of mercury, and the height of the column with reference to the free surface of mercury in the bulb was uniquely determined by the temperature. This thermometer had the above-mentioned problems of the change of phase of some moisture, and the non-linearity caused by the spherical bulb. However, it was a self-sufficient instrument and avoided the drawback related to the barometer. This thermometer was used by Jacopo Beccari and co-workers in Bologna (from 1715 to 1737).

5. Scales and Calibration

5.1. The Thermometric Scale

The scale was used to read the height of the thermometric liquid in the graduated column, and this could be done starting from the base (i.e., direct scale with increasing values as the temperature increased) or from the top (i.e., reverse scale with decreasing values as the temperature increased). The Little Florentine thermometer only had bids, but no numbers, and could be read in either direction. All early thermometers had a scale, but not the same.

5.2. When the Scale is Unknown

Some observers published their data without specifying the scale that is in arbitrary units AU. Deciphering these arbitrary units, each one different from the other, poses a very difficult problem. The scales used by Beccari in Bologna have been recognized [

46]; the scale used by Temanza in Venice will be considered in the near future, taking advantage of the contemporary series in Padua.

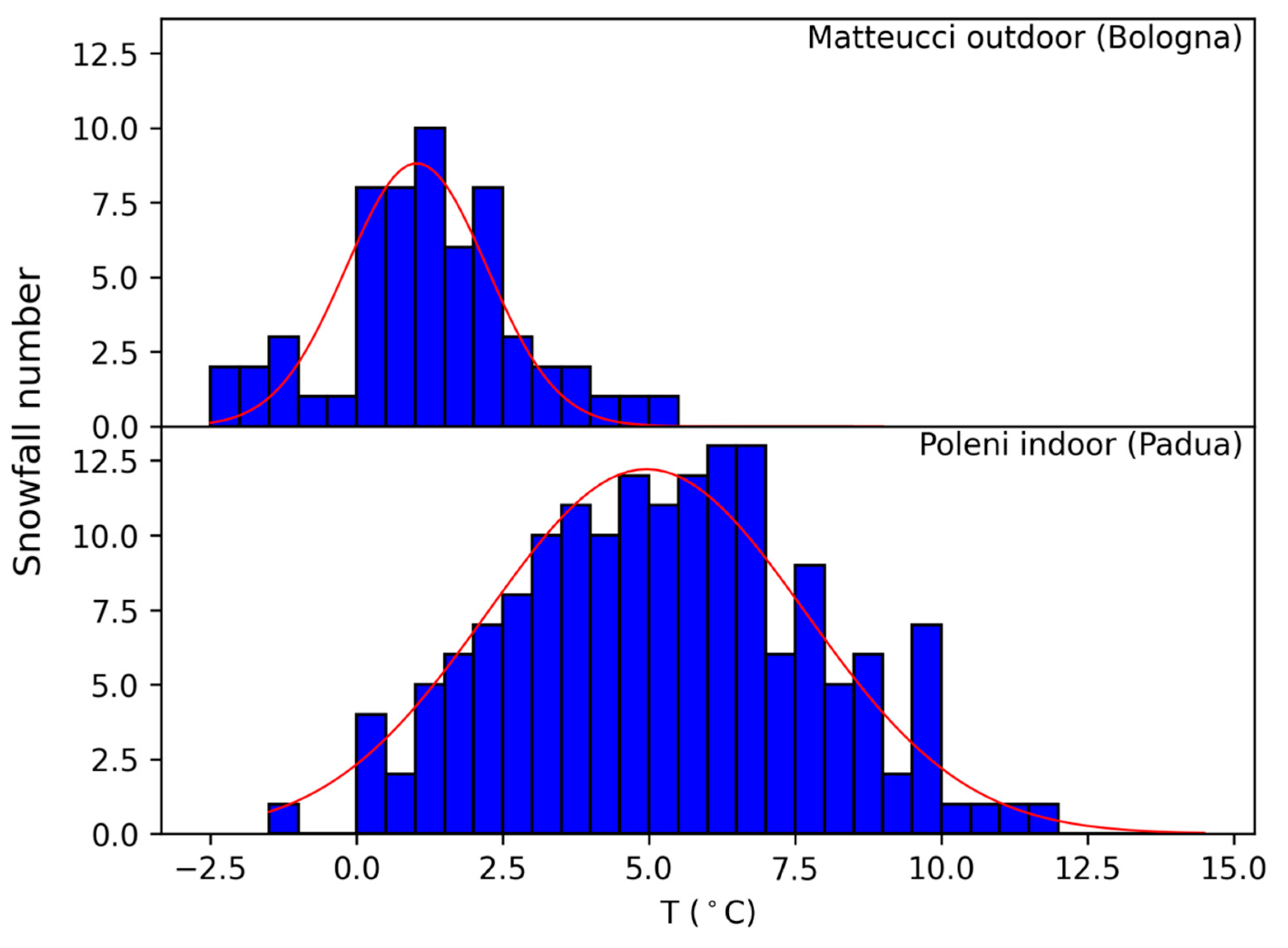

Very useful information is when the log contains notes about the weather. If the observer registered when it was snowing, we can take note of the AU temperatures of the snowing days, and consider that snowflakes may fall either at temperatures below 0°C, but also some degrees above 0°C if the air is dry enough, because vaporization lowers the temperature of falling snowflakes [

47,

48,

49]. This fact may be used to calibrate thermometers [

24]. The method consists in dividing the temperature in narrow intervals, each of them constituting a bin, and putting in each bin the number of times snowflakes were observed in that temperature interval (

Figure 4). After comparison with known temperature values, it has been found that the 0°C may be recognized as the upper inflexion of the bell-shaped histogram representing the number of snow days versus temperature. This method has been used in a number of case studies [

39,

46,

50].

Unfortunately, there is not a natural phenomenon to take advantage to recognize the upper part of the scale. If there is another contemporary record in the same locality or nearby, and we know the relationships between the two sites, it is possible to compare the average values of the same summer months in the two sites. This may give a crude but realistic indication.

5.3. Fixed Points for Calibration

To make readings comparable, some fixed points were suggested since the early period, e.g., Christian Huygens [

51] and then Carlo Renaldini [

52] suggested the melting point of ice and the boiling point of water; Joachim Dalencé [

53] the freezing water and the melting butter or the melting ice and deep cellars; Isaac Newton [

54] the melting snow and the blood temperature of a healthy adult male; Olaf Christiansen Roemer [

13] a mixture of sea salt and crushed ice, and in addition the blood temperature; Philippe de la Hire [

55] the freezing water and the cellars of the Paris Observatory; Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit [

56] adopted a three-point calibration, i.e., the mixture of ice and ammonium chloride, the melting ice and the body temperature; Jacques Barthélémi Micheli du Crest [

57] the underground caves of the Observatory of Paris and boiling water; Anders Celsius [

58] the centigrade scale, but inverted. In the 18th century, there was a plenty of scales. Martine [

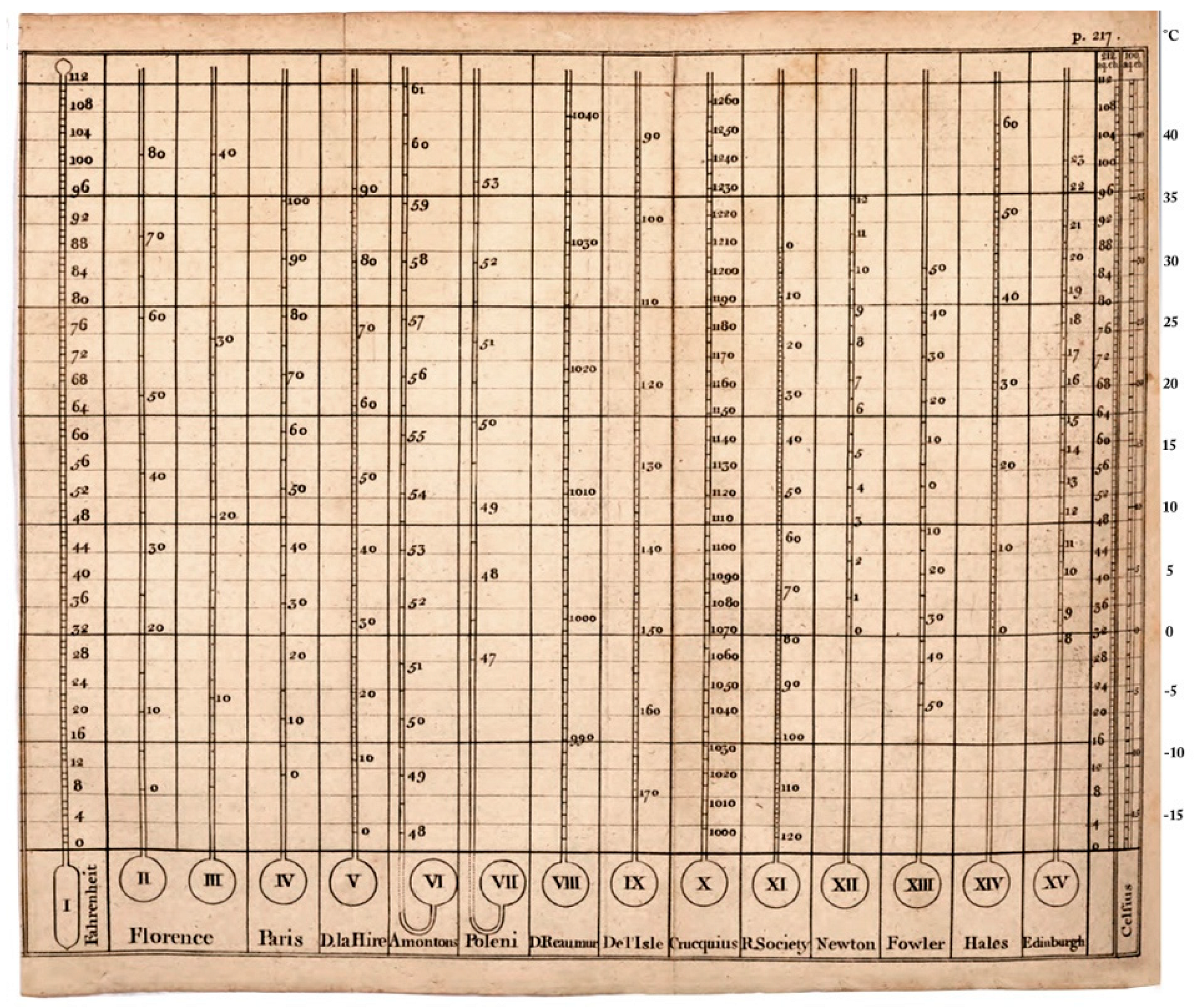

59] (

Figure 5), followed by Cotte [

60], published a table that compared 15 of the most popular scales in the first half of the century, and Landsberg [

17] a table including 36 scales. It is surprising to find in Martine [

59], in the last column, the Celsius scale, not the original reversed form (i.e., 100 °C at the freezing and 0°C at the boiling point) but as we use it today, and two years before the official publication by Celsius [

58]. This suggests that Celsius published it some years after he had proposed and used it [

61]. In Italy, the Celsius scale became popular at the end of the 19th century, substituting the largely dominant Réaumur scale.

Although calibration points constituted a big step forward, they were not always applied correctly, or they were not suitable for the thermometer. For example, many winter days were below the melting temperature of ice, especially on the mountains or the polar regions. This required an additional lower point, determined with a solution of brine made from a mixture of water, ice, and ammonium chloride. The ammonium chloride was substituted with the sodium chloride (marine salt) that was cheaper but with a slightly different value. Toaldo [

62] noted that the uncertainty was of 5°R, i.e., around 6°C. Similarly, the point of boiling water was not realistic for normal weather, indoor temperature, feverish suffers, and required too long a graduated column of which only a small fraction of it was used, e.g., 1/3. The upper limit based on the human body temperature was more convenient to the everyday use, because it was a good reference for the hottest days in northern Europe. Although these pragmatic calibration points were better viable, they had an uncertain definition. Nevertheless, they were more convenient to represent the upper and lower borders of the range of interest.

5.4. Deviations from Linearity, the ‘True’ and the ‘False’ Réaumur Scale

A serious difficulty was that, after calibration, wine-spirit thermometers had non-comparable readings [

57,

59,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. The fact that these thermometers had the same fixed points but different intermediate values meant that the deviation from linearity was not always the same, because it changed with the purity of the alcohol. This posed a very serious challenge to the scientists of the 18th century. Réaumur [

71,

72] conceived a single calibration point, i.e., freezing water, but added some additional reference points, i.e., the cold mixture of ice and salts, the body temperature, the temperature of the cellars of the Meteorological Observatory in Paris, and boiling spirit. The initial idea of Réaumur was to build a universal thermometer, with a calibration made adding known small volumes of spirit using phials of known volume, operating at room temperature. However, in his experimental apparatus, Réaumur made some misinterpretation about the boiling point of spirit and water and which of them should be attributed 80°R. The result was the so-called ‘

True Réaumur’ thermometer, as De Luc [

65] named it, that had 80°R (equal to 80°C) at the boiling point of spirit and is close to the Celsius scale [

61]. Thermometers with the ‘

True Réaumur’ scale were built from 1730 till 1740, when Martine [

59] made some serious criticisms to Réaumur.

Martine [

59] wrote: the boiling point is ‘very erroneously graduated’; ‘Réaumur was in the wrong’ when he evaluated the boiling point making confusion between spirit and water; the calibration made with phials at the same temperature disregarded the fact that glass and wine-spirit expand differently. This obliged Réaumur and Jean Antoine Nollet, his pupil and instrument maker, to change mind [

73,

74]. From Nollet we know that the revised Réaumur thermometers, built after 1740, were calibrated with 80°R at the boiling point of water, i.e., 100°C. De Luc [

65] named ‘

False Réaumur’ this revised generation of thermometers (i.e. 80°R = 100°C) to distinguish them from the previous generation of ‘

True Réaumur’ (i.e. 80°R = 80°C). The ‘

False Réaumur’ is the scale of the popular Réaumur thermometers that were adopted by the Network of the

Societas Meteorologica Palatina, Mannheim [

77] and have been used worldwide, especially in the 19th century [

61,

75,

76].

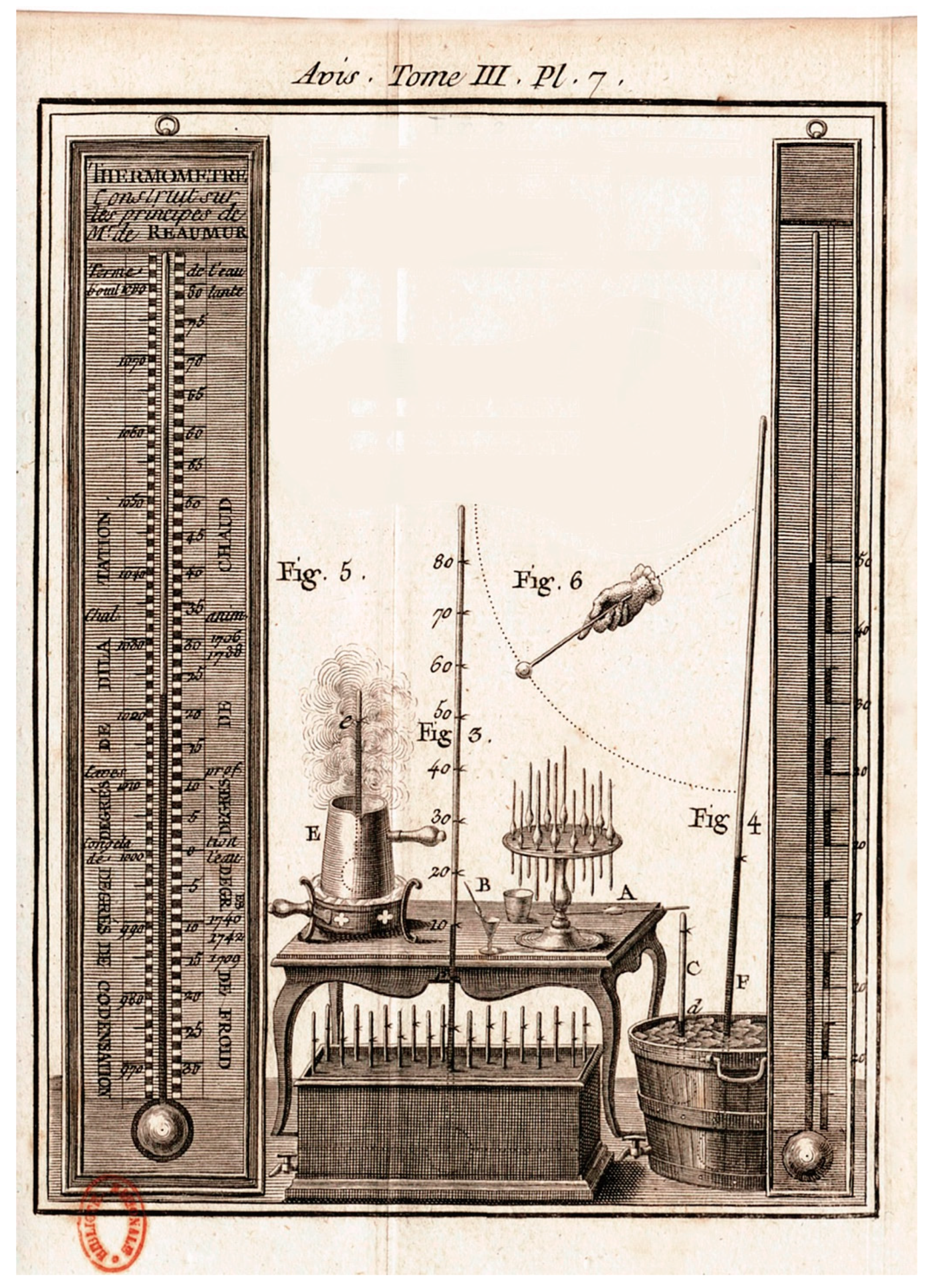

About the revised Réaumur scale, Nollet [

74] was clear in text and illustration (

Figure 6). The figure shows a pot of boiling water and crushed ice in which the thermometers were dipper. There was a big thermometer with long capillary tube, called primary, and several small thermometers that were compared to the primary one, and the level of the spirit in the tube was marked with a silk thread, well visible in the figure. On the table, a serving stand holds some glass phials for the volumetric calibration.

In general, the level of the meniscus at the calibration points was marked by knotting a silk thread on the capillary, and then dividing the length L of the capillary between the two fixed points in a selected number of equal intervals (e.g., 80 for the Réaumur scale, so that 1°R = L/80) and extrapolating these divisions on the side of the intense cold.

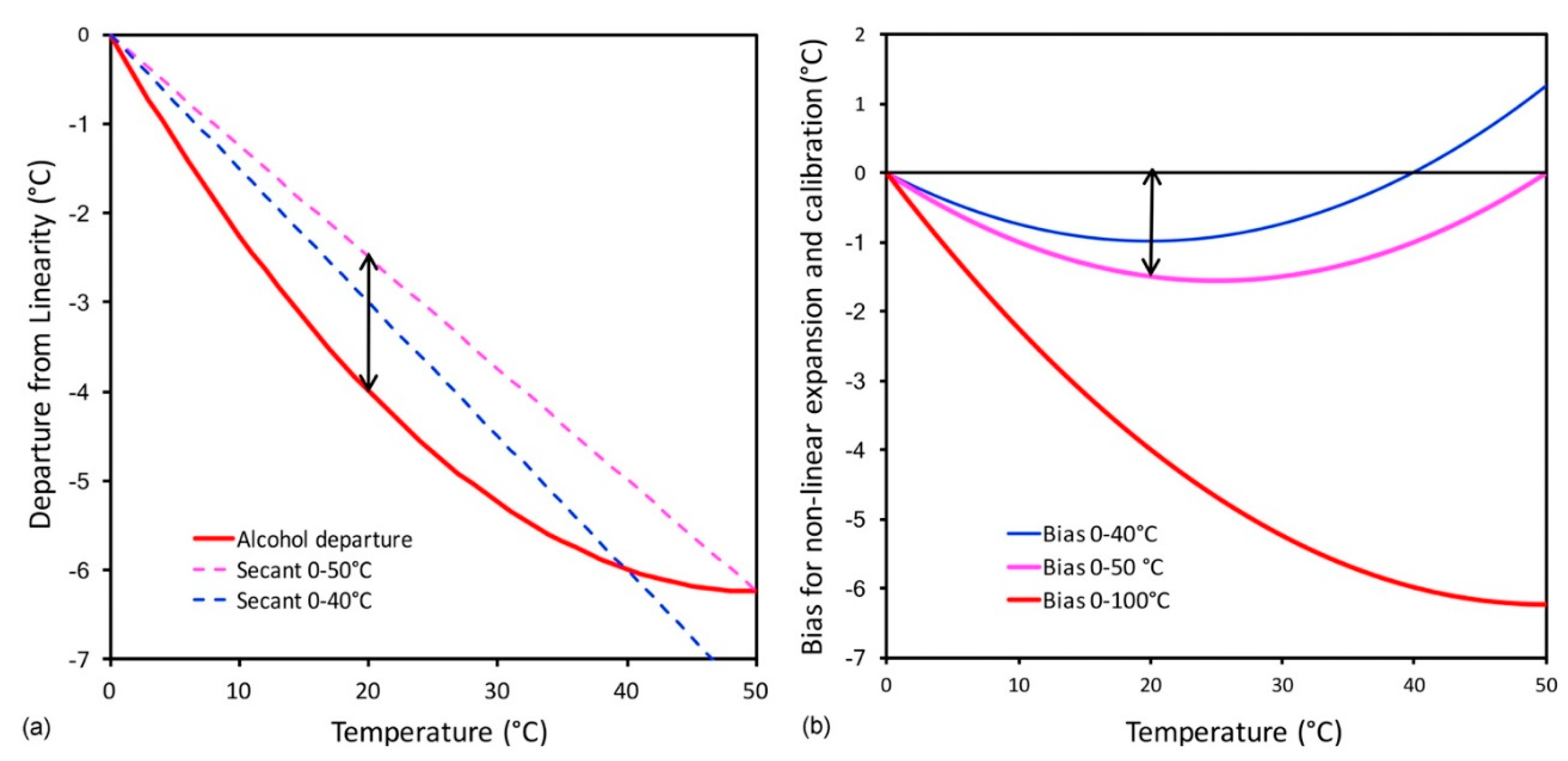

The method was fine for liquid with linear expansion, e.g., mercury above 0°C, linseed oil [

78], but not for alcohol that deviates from linearity. In addition, ethyl alcohol had a deviation that increased with the proportion of water mixed to it. In the hot summer days, at 40°C, the readings were underestimated by 4-5°C [

79]. Alcohol thermometers with spirit not at the same purity level gave different readings and even more different from mercury thermometers. The data comparability was a hard problem in the 18th century. The difference ∆(

THg,a) between the reading of a mercury (

THg) and of a well-purified (e.g., 95 % ABV) alcohol thermometer (

Ta) (

Figure 7a) is

The reading

Ta may be converted as it was taken with a mercury thermometer (

THg) using the inverse formula:

5.5. Calibration by Comparison with a Mercury Thermometer

Things were different if the spirit thermometer was not calibrated at the fixed points 0°C and 100°C, but by comparison with a primary (i.e., mercury) thermometer at two points, e.g., 0° and 40°C, or 0° and 50°C (

Figure 7a). At the calibration points, the readings are correct. For other temperatures, the bias is limited to the departure of the quadratic curve of non-linear expansion of alcohol from the secant that joins the two calibration points, e.g., 0° and 50°C. The secants represent a linear interpolation between the two calibration points, that is the behaviour of a mercury thermometer. Therefore, the departure of the quadratic curve from the secant represents the bias of a spirit thermometer with calibration made by comparison, with the upper point lower than 100°C (

Figure 7b). When calibration is made by comparison with a mercury thermometer, the maximum bias is strongly reduced, and is of the order of magnitude of 1° to 1.5°C. For the temperatures selected for the Little Florentine Thermometer, the bias was within ±0.5 °C [

79].

Excellent results were obtained if the calibration of the spirit thermometer was made at a number of selected temperature levels by comparison with a mercury thermometer as suggested by Cavendish [

80,

81]. The two thermometers were dipped in the same bath, e.g., a pot of hot water, where the temperature was allowed to decrease very slowly. When the column of the mercury thermometer reached some selected levels, e.g., 50°, 40°, 30°C and so on, the instrument builder knotted a silk thread on the capillary of the spirit thermometer and reported the same values on the scale. Therefore, these reference values were the same as the thermometer used for calibration, and the intervals between two consecutive benchmarks were divided linearly. However, if the interval was relatively small, e.g., 10°C, the departure was negligible.

5.6. Calibration of the Amontons Thermometer

For the Amontons thermometer, the calibration should be made considering both the Amontons thermometer and the barometer operating simultaneously. In the 18th century, the barometric corrections for gravity and temperature were not applied. Likely, the calibration was preferably made in winter to have ice available, and the freezing point was established with both instruments kept around 0°C. In contrast, the upper limit was established with just the bulb of the thermometer held in the hot steam of a boiling pot of water, while the barometer was left cold [

81]. The combination of hot thermometer and cold barometer was unrealistic because in the real world both instruments operate in the same room and at the same temperature. This required a specific correction, by calculating the true pressure and the expected bias for this difference.

6. Transformation from the Ancient to the Modern Time Frame

6.1. The Canonical Hours of the Italian Time

In the antiquity, most of Europe followed the tradition of the Roman Empire, of starting the new day immediately after the previous died, i.e., at sunset. For most countries, this practice continued over the Middle Ages, and the hours were announced with bells from the tower clocks, i.e., the so-called

canonical hours or

Italian Time [

82,

83]. The political events partially changed this situation, but Italy, Poland, Bohemia, Silesia, Portugal, and some others followed the tradition of the canonical hours till the end of the 18th century. In Padua, the change of the day starting from the twilight to midnight occurred in 1789, imposed by Napoleon. Theoretically, for every site, the new day started at twilight, when everyone fell into darkness. This was the most popular tradition. However, the time of darkness was not well defined because in clear days, twilight gained some 30-40 minutes of pale light, depending on the season, but in case of rain, cloud cover, or fog, darkness occurred earlier, e.g., an hour or even more. In addition, in the 18th century, the wall sundials responded to the actual position of the Sun and the mechanical clocks were adjusted every day with the upper culmination of the Sun (i.e., the Sun passing through the local meridian); sundials and clocks of cultured people responded to the actual Solar position, that could be related to the sunset (governed by precise astronomical laws), not the twilight (governed by astronomy and uncertain weather factors).

The definition of when the day began was unclear. Somebody preferred twilight because darkness was evident to everyone. Astronomers preferred the sunset, because it was objectively defined, but the people did not agree because in the cities there was no a free horizon and it was difficult to establish the precise moment in which Sun crossed it. However, given the imprecision of 18th century clocks, this didn't make much difference. Toaldo [

84,

85,

86] was clear on that issue, and published instructions and detailed tables with numerical values to pass from the canonical hours of the Italian Time (day starting from the local sunset) to the French Time (day starting from the local midnight). Most EIR in Italy are based on this reference and the ancient time must be transformed in modern time units. Astronomers were used to refer the position of the stars to the lower Solar culmination (i.e., local midnight when the Sun crosses the meridian from the opposite side of the Earth) and a minority of records follow this style.

The EIR recovery requires a series of adjustments for time, that changed day by day, i.e., for the running day j of the calendar year it is necessary to apply a number of astronomical corrections to transform the temporal frame based on the actual Sun motions represented in spherical coordinates, to the Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) of Italian Time Zone (UTC+1) referred to the Greenwich Meridian. This requires to calculate the solar declination over the year and combine it with the local latitude; the consequent change of the daylight time characterized by the effective instant of sunset and the time elapsed to reach the local midnight; the combined effects of the eccentricity and obliquity that make the Sun motions to appear slower or faster (i.e., the so-called Equation-of-Time to adjust these departures), and the correction for the difference of longitude between the local site and the Time Zone reference, as described in the following sections.

6.2. Solar Declination

The solar declination

of the running day

j of the year is an astronomical variable necessary to calculate the exact time of sunset. To make calculations, an adjustment should be made because the civil year starts on January 1

st, while the solar cycle starts with the winter solstice, on December 21. This requires adding

D =10 days to

j. When the precision of seconds is not relevant, the simplified equation is used:

The range of is ±23.44°.

6.3. Time Elapsed from Sunset to Local Midnight

As the day started from sunset, it is necessary to subtract the time elapsed from sunset of the day

j to the lower culmination of that day (i.e., the apparent local midnight). Then, the given hours are counted starting from the actual midnight also variable with the calendar day

j. Sunset may be found tabulated in astronomical or nautical almanacs with solar ephemerides, or may be calculated under the condition that the height

H⨀ of the Sun above the local horizon equals zero, i.e.

where

φ is the latitude, and

τ the astronomical hour angle 360°. The latter is transformed in 24 h clock time

t with the equation:

To make astronomical calculation easier, the t hours are considered after the upper culmination, i.e., midday assumed as t = 0; therefore, t < 0 in the morning, and t > 0 in the afternoon. After, t is transformed in accordance with the popular style 0 to 24 h, starting from midnight.

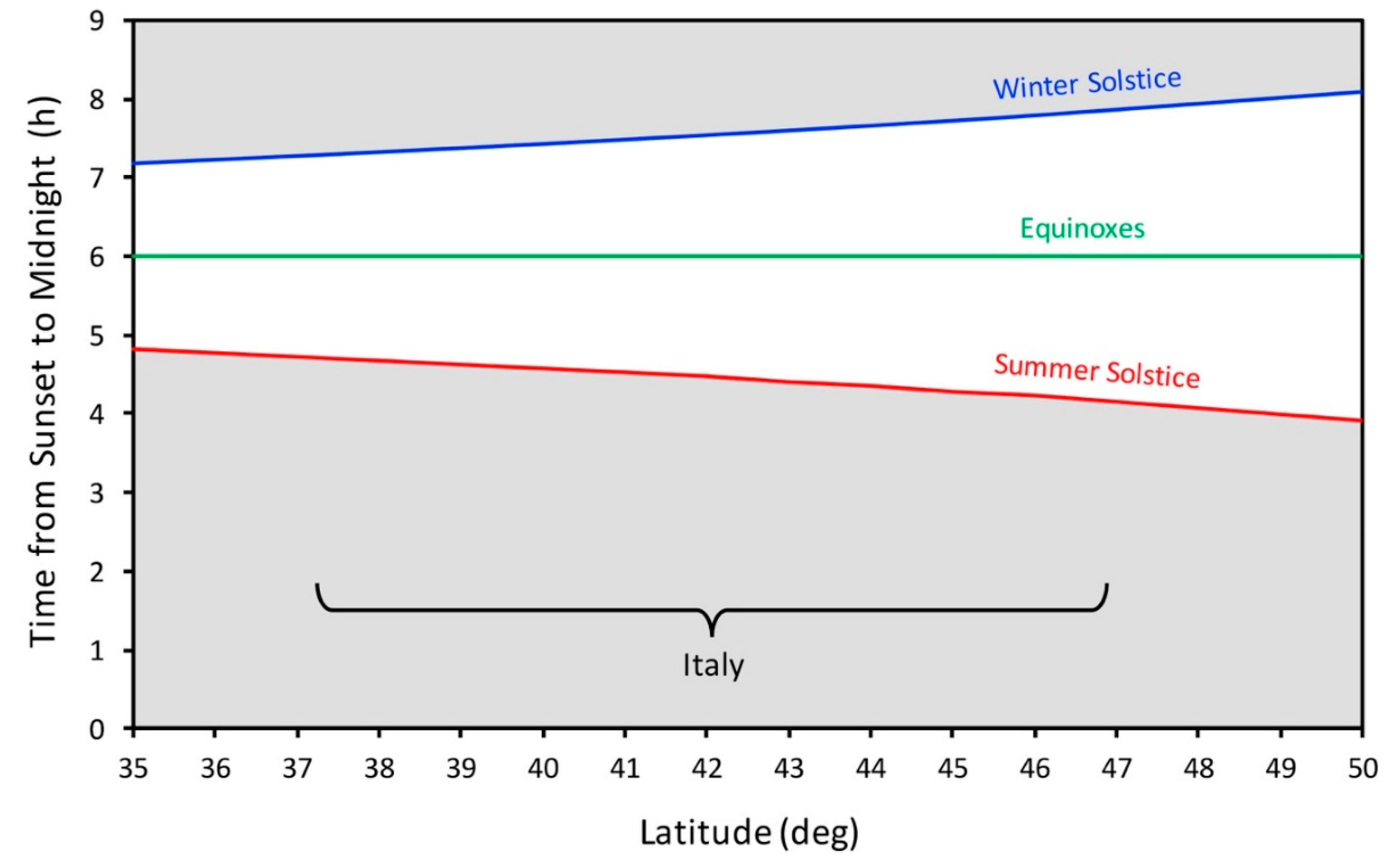

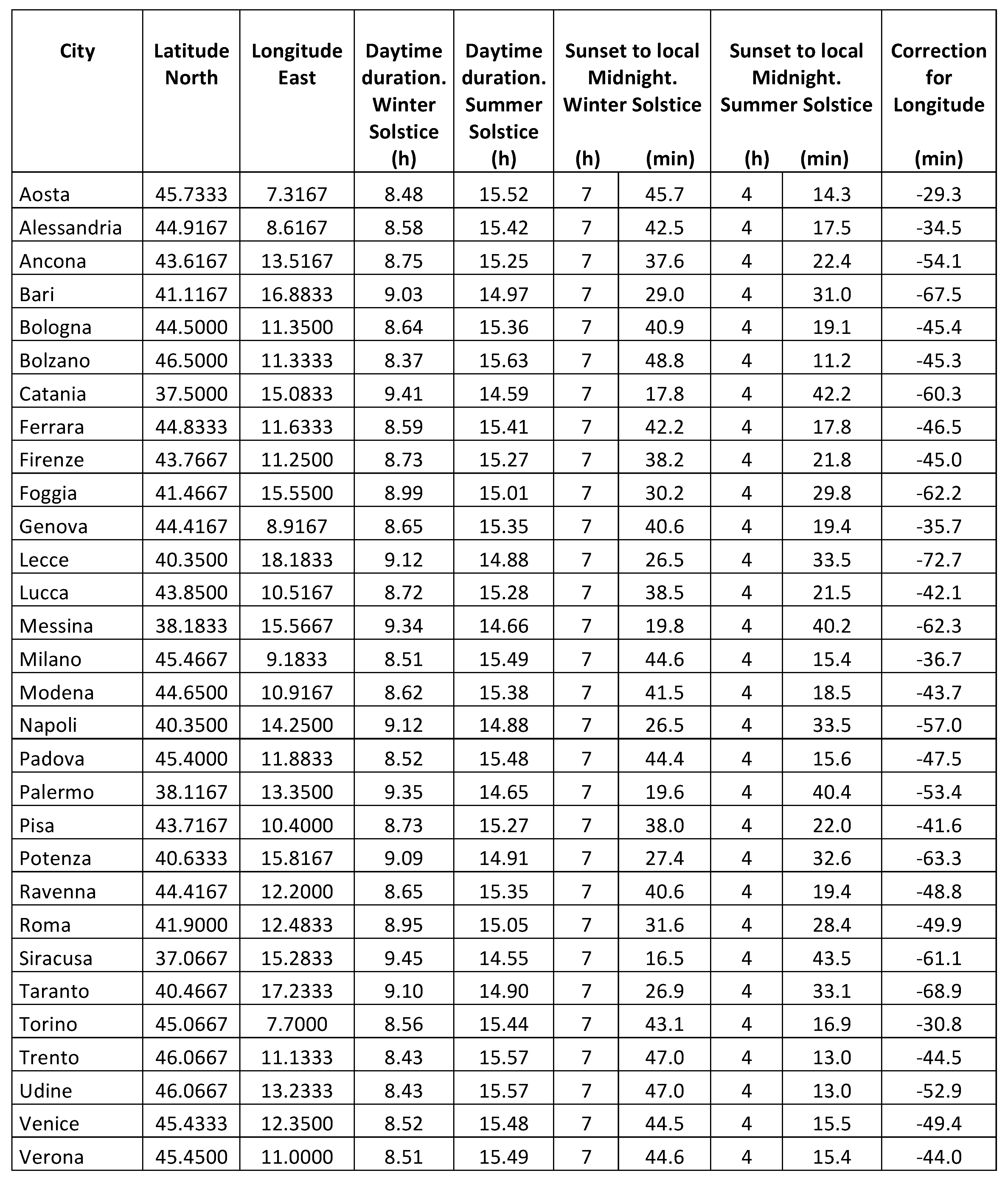

Equation (4) is represented in

Figure 8. Both show, either mathematically or graphically, that the time from sunset to the lower culmination changes with the declination and latitude. It can be noted that cos

τ vanishes for

τ = π/2 (i.e.,

t = 6 h) when

, i.e., at the equinoxes. The extreme values are reached at the solstices. Except for equinoxes, the daytime duration (i.e., from sunrise to sunset) increases with the latitude. At the solstices, sunrises and sunsets change each 3.522 min per degree of latitude, and the daylight duration 7.044 min per degree of latitude. As Italy lies in the latitude belt from around 37° to 47°, the sunset in the Northern borders occurs some 35 min later than in the Southern ones, and the change in the daytime duration is twice this value, i.e., 1 h 10 min. Examples of values for 30 selected cities over Italy are reported in

Table 1.

6.4. Equation-of-Time

The apparent motion of the Sun is uneven for the combined effects of the yearly cycles of the eccentricity of the Earth orbit, and the obliquity of the rotation axis of the Earth. The so-called equation-of-time (EoT) [

87] represents the departure between the apparent solar motion of the running day

j of the calendar year and the average solar motion over the year (

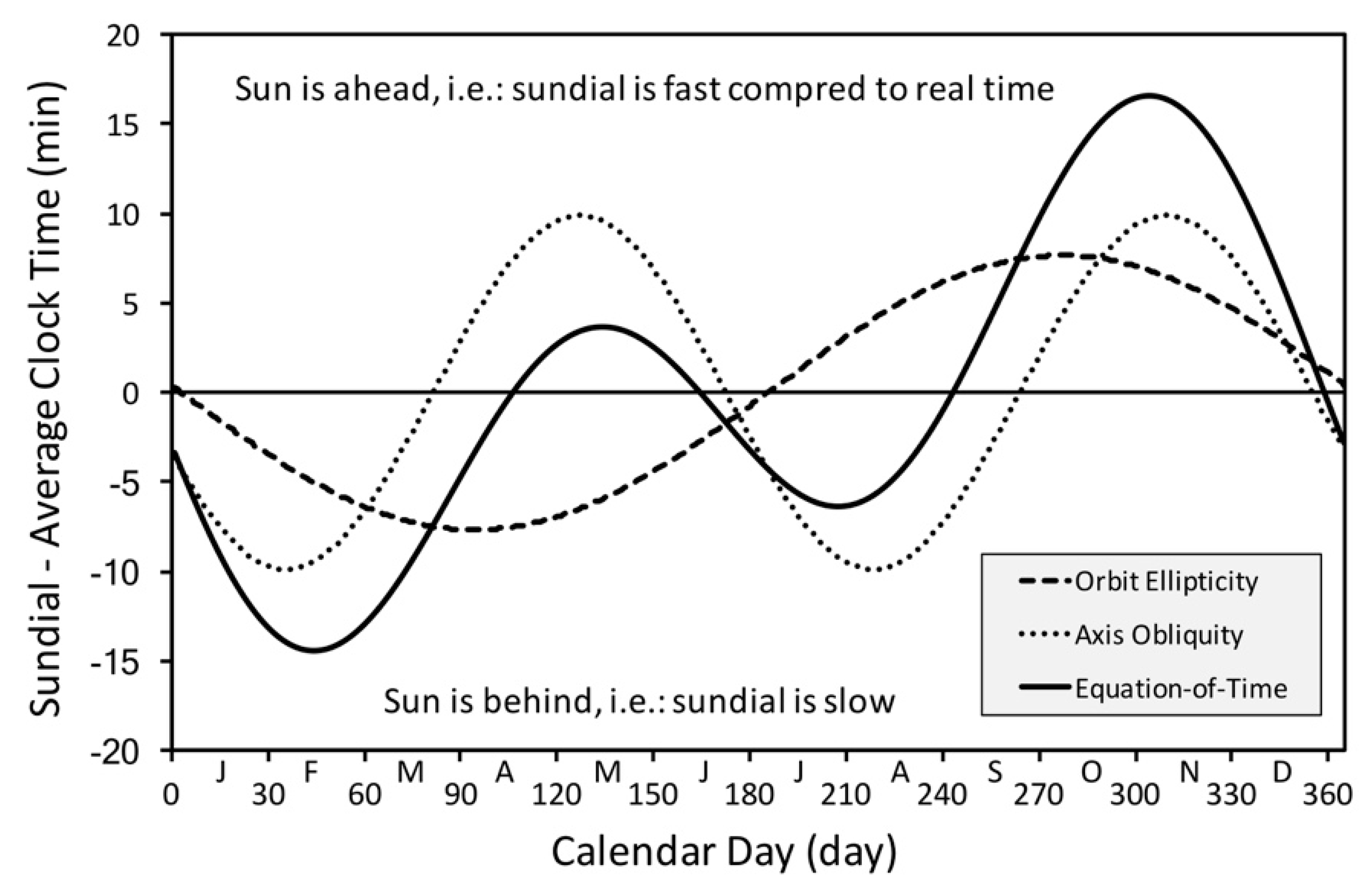

Figure 9).

where 365.25 days is the duration of the Julian astronomical year, and

P the perihelion calendar day, i.e., 2 ≤

P ≤ 5 days (from January 2 to 5 depending on the leap or post-leap years). The departure ranges from −14 min 6 s (February 11) to +16 min 30 s (November 3). Leap years, as well as leap +1 year, leap +2 years, and leap +3 years, change of the perihelion date, change of the winter solstice, Moon perturbation and atmospheric refraction will affect a little the mentioned dates (±2 days). The consequence on EoT values is within ±20 seconds, that are irrelevant for meteorological data. The secular change accounts for some 20 seconds per century, that is also irrelevant to our aims.

6.5. Correction for Longitude

For the rotation of the Earth, and the geographical location of the site, the local meridian is crossed earlier (longitude East) or later (longitude West) with reference to other selected meridians (i.e., local times are not simultaneous) and in particular to the reference meridian of the Time Zone. The departure

corresponds to the angular difference between the longitude

of the site and the meridian selected for the time zone (e.g., UTC+1 makes reference to the meridian 15 degrees East of Greenwich), and the difference accounts for 4 minutes of time every 1 degree of arc of longitude:

Italy lies between the longitudes 6.6° and 18.5° East, that means

= -26,4 and -74 min, respectively, i.e., around 48 min difference between the most eastern and most western borders. The longitude corrections for 30 selected cities of Italy are reported in

Table 1, last column.

6.6. From the Local Time to the Time Zone

In 1866, after Italy was unified and became a single state, all the cities adopted the mean local standard time of the Capital, i.e., Rome, with = 12.452333° longitude East. However, in 1893 the reference was changed to Mount Etna = 15.00° longitude East that nearly coincided with the First Meridian, 15° longitude East of Greenwich. The change of reference corresponded to -10 minutes; therefore, Italian readings made from 1866 to 1893 should be shifted by 10 minutes. In 1893, Italy adopted the Central European Time (CET), i.e., the Time Zone 1 or in Coordinated Universal Time UTC+1, that equals the Mount Etna reference.

6.7. Transformation from the Italian Time to Modern UTC Time

The transformation from the ancient time

tCH in canonical hours to the present-day time

tPD is obtained by combining the previous departures:

The exact transformation of time is crucial when one calculates the anomaly or investigates trends, because an incorrect transformation may cause consistent differences in the observing time and, consequently, in the related temperature [

88,

89]. More details about the methodology, as well as examples of specific case studies concerning selected Italian cities, Paris and Switzerland, can be found in the literature [

24,

39,

40,

45,

46,

82,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94].

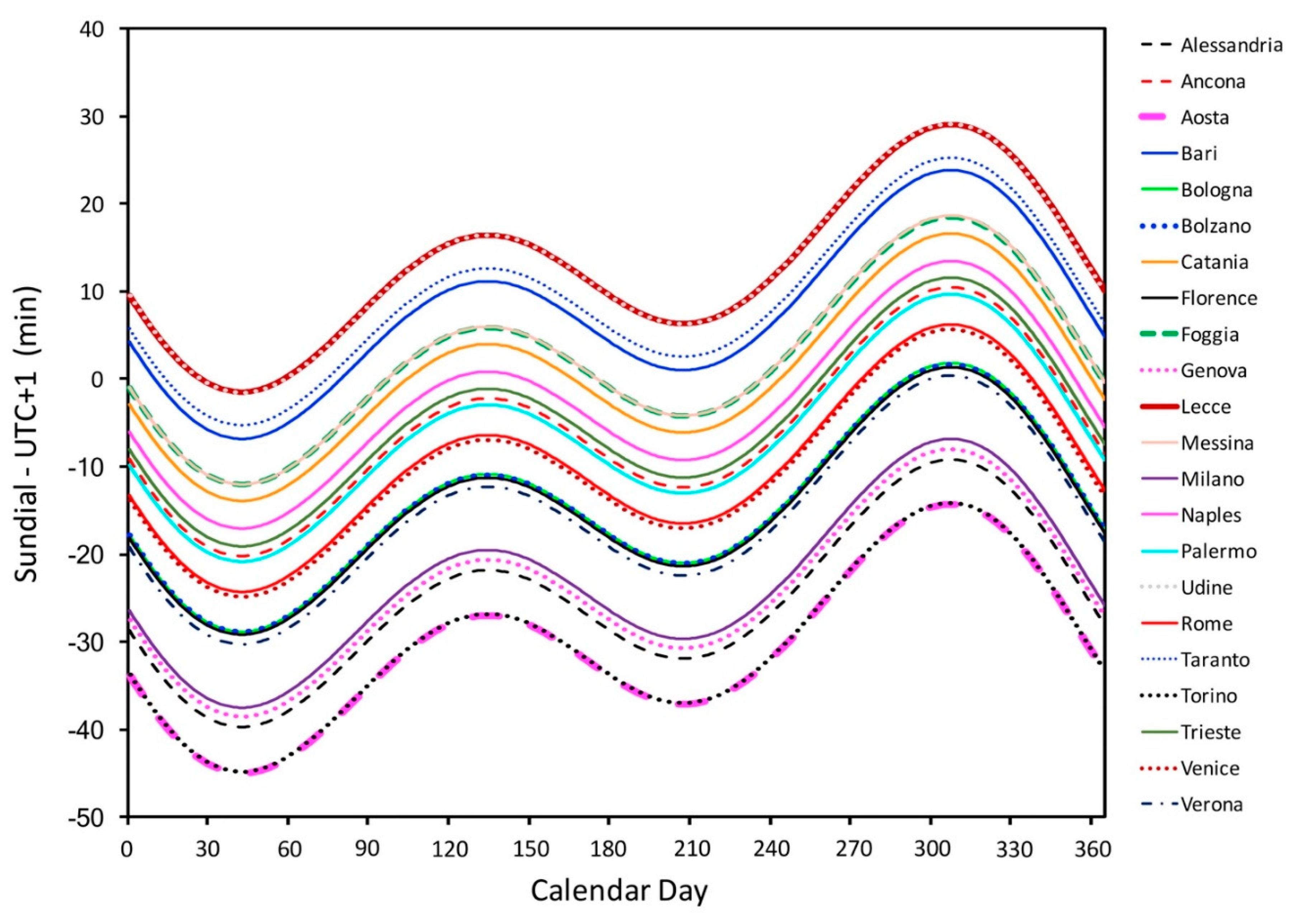

The difference between the apparent solar time (as observed with a sundial) and the official modern UTC time (i.e., the Coordinated Universal Time) of 92 selected sites over Europe, lying in the Time Zones UTC+0, UTC+1, and UTC+2, has been calculated by Camuffo et al. [

83]. Over Europe, the departures between a sundial and the related Time Zones range from -100 to + 40 minutes. An example of the difference between the local time of sundials in Italy and UTC+1 (calculated disregarding the change of 1 h in summer to save energy) is here reported for 22 Italian cities (

Figure 10). It is evident that the belt width is 35 minutes, and the two eastern cities that overlap on the top are Lecce and Udine, while the two western cities on the lower border are Aosta and Torino. The most extreme departures are around -45 minutes reached in February and +30 minutes in November.

7. Reading Times

7.1. Impact on Indoor or Outdoor Measurements

The long series are affected by changes in reading times, either random or systematic. When the measurements of EIR were taken inside, in unheated rooms, people considered that the room temperature was mainly constant over the day, so that readings were taken at the observer’s convenience around a selected time, e.g., when the observer woke up in the morning, or when he returned home for lunch, or in the evening after dinner. Some observers carefully followed the established protocol; others made observations at random times.

With indoor observations, the daily cycle was smoothed by the building envelope, so that a small change of reading time caused a negligible departure. However, indoor readings are difficult to relate to the outdoor temperature. Sometimes there is the lucky opportunity to find an outdoor series with a common sub-period. If the data over the common sub-period are represented in a scatter plot, i.e., the indoor versus the outdoor readings, by interpolating the dots with a polynomial fit, it is possible to obtain the transfer function and transform the whole period of indoor readings as they were taken outside. For instance, Poleni observed indoors, once a day. The parallel series by Morgagni, who measured both indoors and outdoors, was of little help, because his external thermometer was biased by the thermal inertia of the thick walls. It has been necessary to find the indoor/outdoor transfer function of the Beccari house [

46], that was a similar building, to transform the Poleni dataset as it was taken outdoors [

95,

96].

With outdoor observations, the regularity of the reading time is highly relevant, and a key problem is how many observations per day were made. Some different cases are considered in the next section.

7.2. Readings Made at Irregular Times

Especially in EIR, it is frequent to find that an observer planned some reading times, e.g., when he woke up and after lunch, but then readings were made earlier or later. Depending on the hour of the day, and the season, the departure from the reading time may cause a consistent bias in temperature. A methodology has been adopted to correct several case studies [

39,

46,

50,

82,

83,

92,

96]. The method consists in considering a climatically representative dataset of the site with data at hourly or sub-hourly resolution. After, a matrix with the calendar days (1-365 d) in abscissa and the hour (0-24 h) in ordinate is created that represents the combination of all the daily cycles over the year. Therefore, if in the day

j a reading was made at the time

tO+∆

t instead of at the time

tO, the matrix gives the average departure in temperature ∆

T that is related to a ∆

t earlier or later, in that day

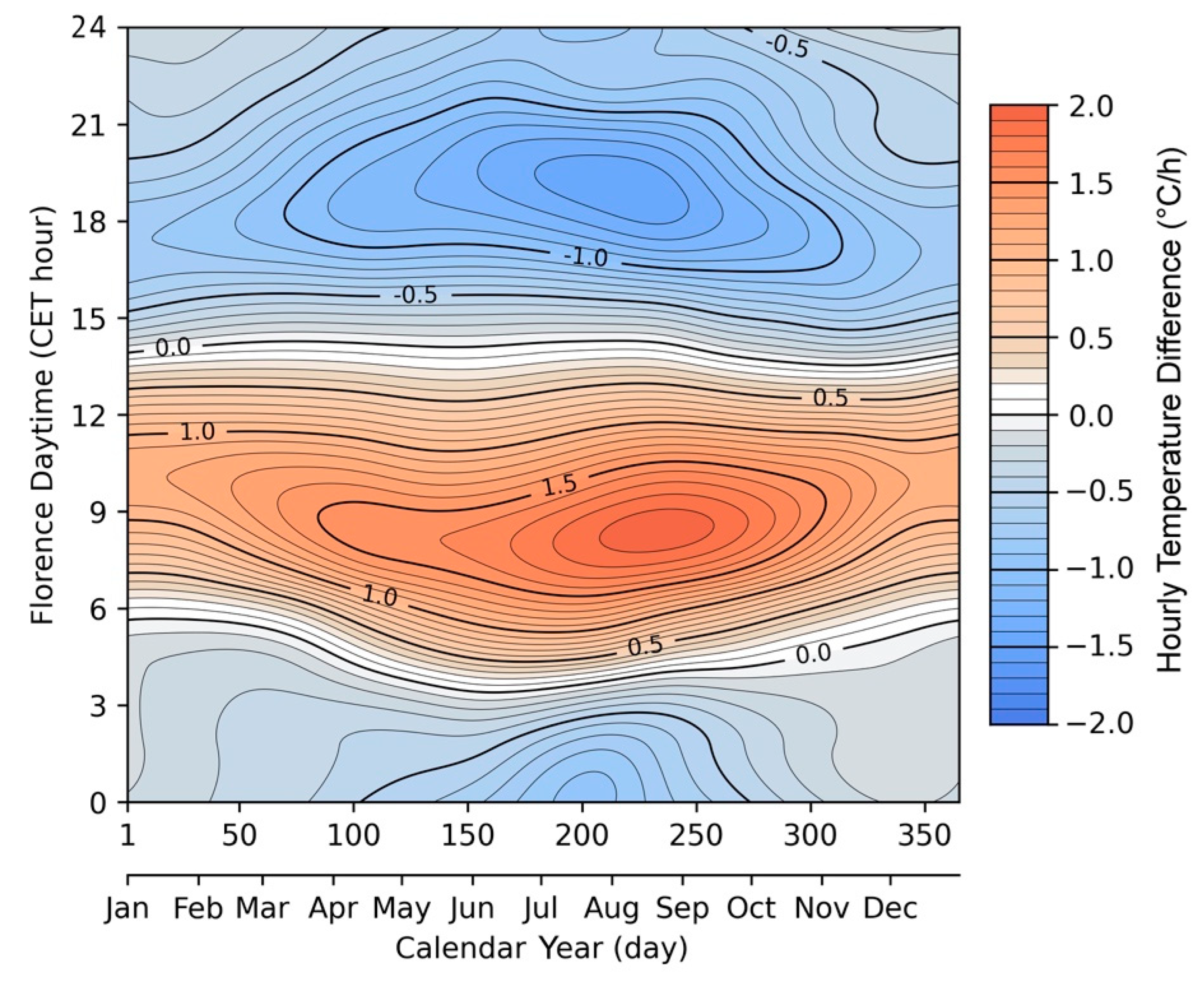

j of the calendar year (

Figure 11).

7.3. Single Observation per Day

Some EIR are composed of only one observation per day, taken at a selected time, e.g., the hour X. This shows how this particular temperature varied over time. The daily minimum, maximum and average daily values remain unknown. However, if one considers the series at the hour X and compares it with the data at the same hour X during the 1961-1990 (or 1991-2020) reference period, one obtains the anomaly for the hour X, i.e., the climate change from the early instrumental period to the modern reference period at that specific hour.

One might consider that the anomaly is only weakly dependent on the observation time, i.e., the anomaly of a series considered at a selected hour X1 is close to the anomaly at another selected hour X2. Based on this assumption, it is possible to apply the method in reverse, i.e., knowing the anomaly for the specific hour X, and knowing in the modern period the hourly changes ΔT(t) for every calendar day j, it is possible to apply the method backwards. This means that in the reference period one should establish, for every calendar day j, the temperature difference between the hour X and the hour of maximum temperature (Tmax), and the same for the minimum temperature (Tmin). Applying these values to the reconstructed series, one obtains the two series of Tmax and Tmin. Combining the above series (Tmax + Tmin)/2 over the calendar day and over the years of the record, one reconstructs the series of the average daily temperatures starting from readings taken at the hour X. The degree of approximation may be verified testing the method on a known, high-quality series.

7.4. Two Observations per Day

In the case of only two readings per day, since they were intended to be representative of the daily minimum and maximum temperatures, they were taken near sunrise and near noon, or a few hours after noon, e.g., Morgagni and Toaldo.

This choice is due to the fact that in antiquity the interest was focused on the median, not on the average. This concept was derived from Aristotle’s ‘

in medio stat virtus’, i.e., the best option lies in the middle, or between the two extremes, and on this ground the secondary stations of the Medici Network observed only in the middle of winter and summer, because the local climate was defined as the value between these two extremes [

24,

40]. This reference (

TA,2R) was initially named ‘

temperato’, i.e., temperate, literally: away from excesses or from the extremes and later average, and was computed as

In reality, the average of these two extremes, was very close to the 24-hour daily average (T

24h) [

11,

95]. An example of the degree of approximation between

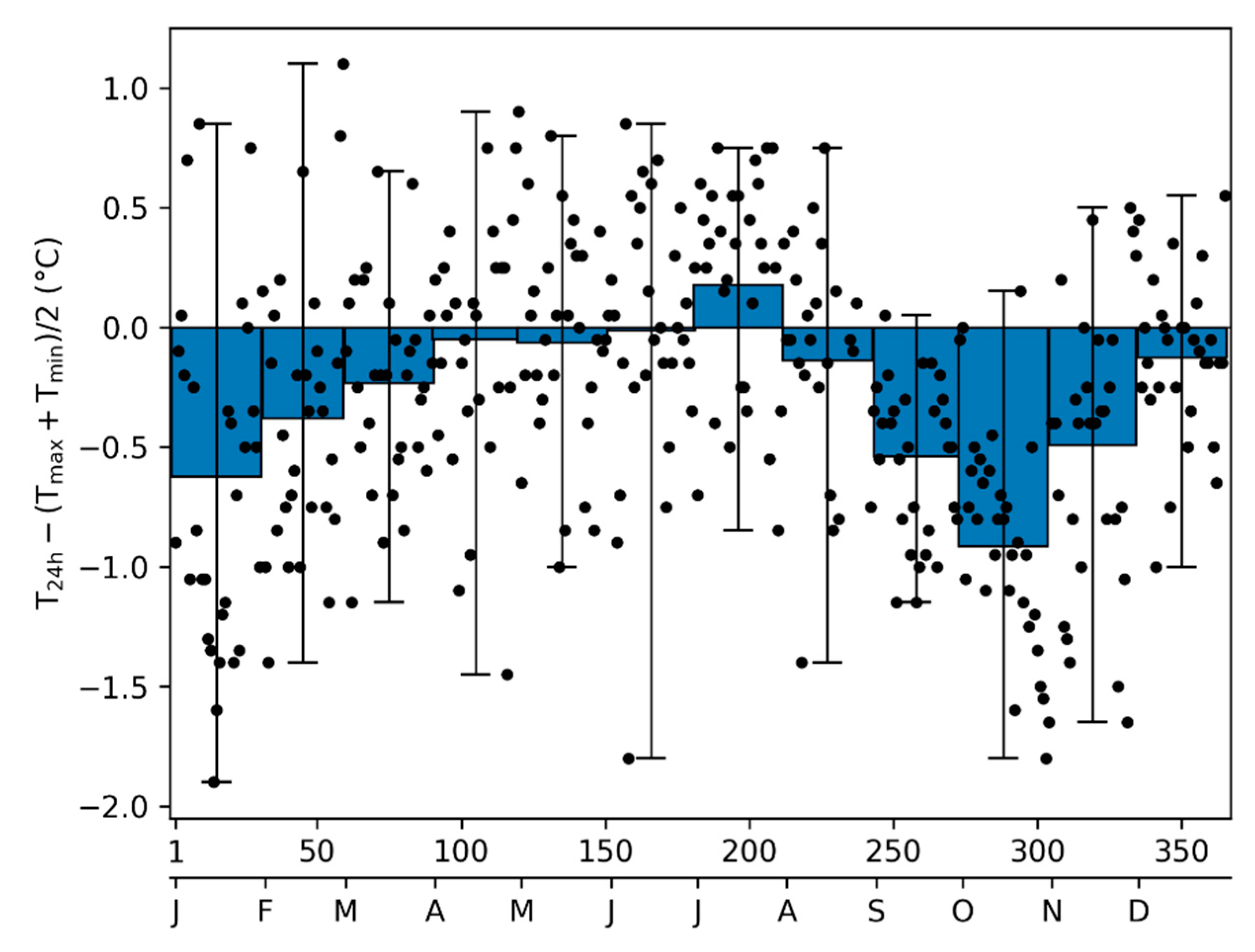

T24h and (

Tmin +

Tmax)/2 is made with modern data of Padua (

Figure 12) over the calendar year 2022. Over the year, the spreading is between -2° and +1°C. The monthly averages show an excellent agreement in the warm season. The maximum departures are in autumn for the heavy rains (maximum departure -1°C in October) and, secondarily, in January (-0.6°C). This general agreement is important, because several early instrumental observations were taken at sunrise and one or two hours after noon. The series of Padua has been corrected for this bias. It should be noted that the use of monthly averages improves the quality of the series, especially the weekly, monthly, and yearly means, but slightly reduces the variance of individual days.

7.5. Three or More Observations per Day

During the 18th century, it was realised that the air temperature

T falls from the late afternoon to sunrise, and it was noted that slightly after sunset there is a moment in which the plot crosses the daily average. This has been considered useful because it was possible to compute a more accurate daily average based on three readings

TA,3R:

that was better advantageous in the case of precipitation or wind change during the day that biased the normal daily cycle. On this ground, in 1783, the secretary of the

Societas Meteorologica Palatina, Mannheim, suggested readings at 7.00, 14.00 and 21.00 h local solar time [

77].

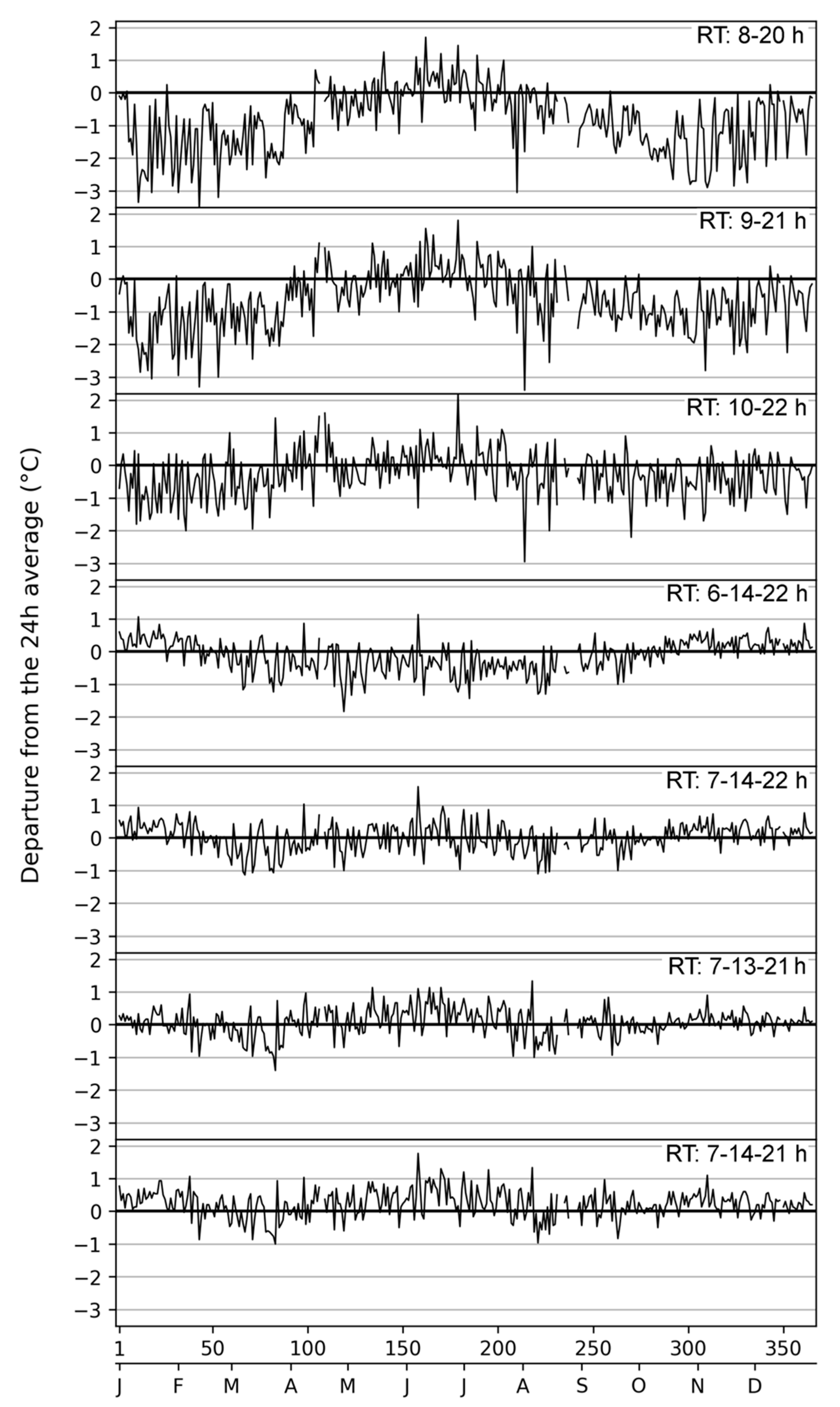

A century later, in 1874, the International Meteorological Congress [

97] recommended selected combinations of reading times (RT), i.e., RT at two equidistant hours (8–20 h; 9–21 h; 10–22 h), or three hours (6-14-22 h; 7-14-22 h; 7-13-21 h; 7-14-21 h), as well as some combinations of four readings including the daily minimum. These methods have been calculated for Padua (

Figure 13) as well as for ten European cities [

83]. In general, the most convenient combination changes with geographical coordinates, season, and local climate. In Padua, the combinations RT 8-20 h and RT 9-21 h give similar results, with seasonal swings (the best period is summer) and peaks reaching -3°C difference. A similar situation is for RT 10-22 h but with reduced seasonal effect that gives a smaller departure. Better results are obtained with the daily means computed from three RT. For them, the departures from the true mean

T24h generally lie within ±1°C.

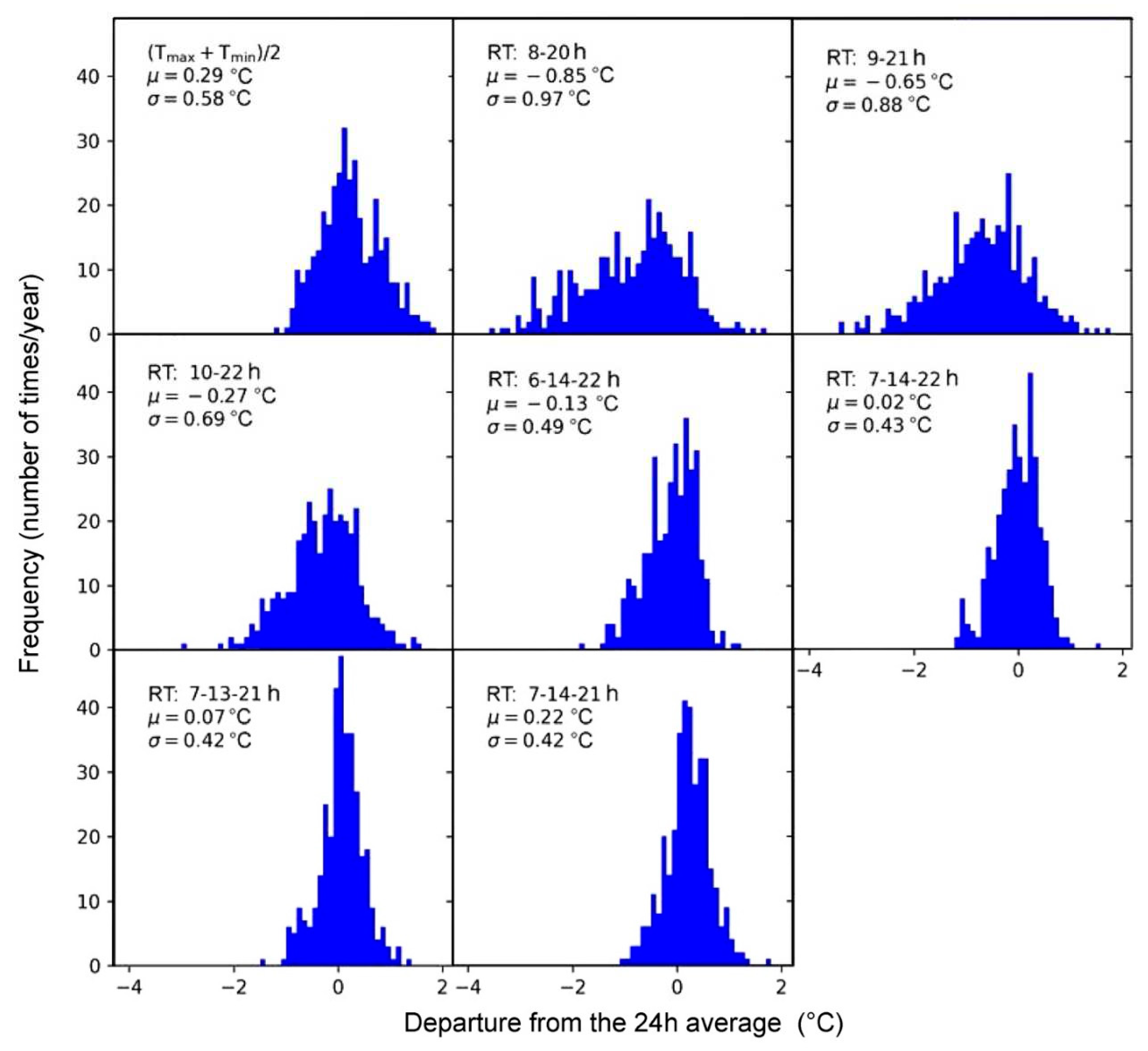

An overall view of the above methods to produce daily means with two or three readings a day is reported in

Figure 14, that summarises the results of

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, and in addition reports the average bias (µ) and the standard deviation (σ) but loses the information about the variability over the calendar year. The best results are obtained at RT 7-14-22 h with average bias µ = 0.02 °C and σ = 0.43°C, and the worst at RT 8-20 h with average bias µ = -0.85 °C and σ = 0.97°C. In this example, every bias remains |µ| < 1°C.

A key problem is that over time the National Services, as well as the International Agreements, changed the reading times. In the period of manual observations, or when data were extracted from strip charts of mechanical recorders, any change of observational protocol, like the three or four hours selected for the daily average, introduced systematic errors. The same type of bias appeared simultaneously over all stations and continued over time. This change in the observational protocol risks to be interpreted as a climate signal.

8. Exposure and Screens

8.1. Indoor or Outdoor Exposure

In the early period, thermometers where not screened from rain and radiation, except the LFTs that were hung on the same wall, one on the northern side and one on the southern side to investigate the impact of the southern and northern winds and the solar radiation [

37,

98]. Except this and other cases, it is rare to find documentation whether the thermometer was kept indoors or outdoors, because the exposure was considered obvious, and there was no need for specifying it. Sometimes useful notes may be found, and the analysis of the data may clarify. Each observer, however, adopted personal solutions. For instance, from 1658 to 1670, Ismaël Boulliau adhered to the Medici Network and the protocol required the thermometer exposed outside. However, he lived in Paris, in the city centre, at the ground floor of a building without private garden. He had the problem that, if the thermometer had been hung outside the window, it would have been stolen in no time. Therefore, his solution was to leave the house ten minutes before the reading and keep the thermometer exposed until it reached equilibrium [

39]. In the 18th century, most of the early thermometers were not weather resistant and were used indoors, with the advantage of investigating the conditions where people lived. When in 1723 the Royal Society, London, established an international network, the thermometer was kept inside [

99].

In Italy, the tradition established after Medici Network (active 1654-1670) of the thermometer exposed outdoors, was very strong. As opposed, the protocol of the Royal Society, London, required indoor measurements. In the 18th century, thermometers were not weatherproof and had to be kept indoors to be protected from rain and sunshine. This generated a series of hybrid solutions. The external thermometers were not in free position far from buildings, but were located in niches or partially open environments, and were affected by the thermal inertia of the masonry walls. The internal thermometers were kept in rooms well ventilated, with open windows, or opened some time before each reading to obtain measurements representative of the outdoor air. For instance, Giovanni Poleni observed in Padua from 1725 to 1761 keeping the thermometer indoors, but he ventilated the room thoroughly, for a long time, before each reading. Giovan Battista Morgagni also measured in Padua from 1740 to 1768, with a thermometer kept inside and another kept outside. Finally, Giuseppe Toaldo and Vincenzo Chiminello observed from 1777 to 1812 with the thermometer exposed outside of the astronomic tower. The problem is to quantitatively assess to what extent an indoor or outdoor thermometer of the 18th century was representative of the actual outdoor temperature, as it were measured following the WMO recommendations.

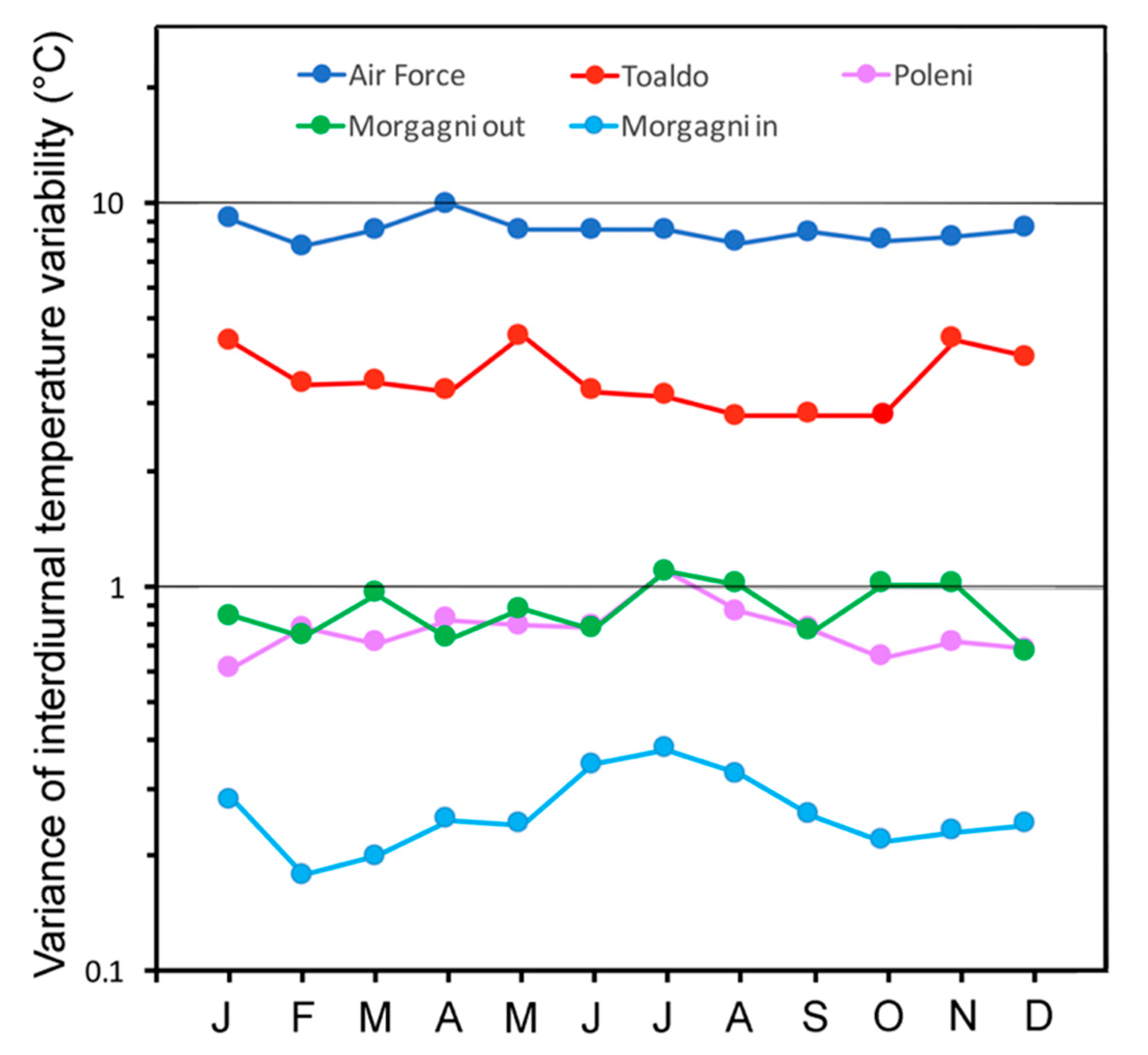

The best way to recognize the building influence is to test how much the daily range Tmax-Tmin is reduced comparing the values outdoors with those indoors. However, this is only possible when two or more readings are taken per day. In the case of a single reading, or two readings taken at times that are not representative of the daily cycle, the only way is to look at the variability of the difference of temperature between two consecutive days.

For each of the above observers, and for the modern data of the Air Force (1951-1990) taken as a reference, an analysis has been made of how much the day-by-day variability was penalized by the thermal inertia of the building [

95,

100]. The method consists in calculating over the calendar year the difference between the mean temperature of the running day

j and the previous day

j-1 and considering the variance of these departures, i.e., the larger the building influence, the smaller the variance (

Figure 15). The record of the Air Force, with the thermometer kept in a louvered Stevenson screen, shows the highest variance. The record by Toaldo, taken in the free air outside the Tower, but close to the widow to read data from inside, has about half the variance of the Air Force. The well-ventilated room of the indoor observations made by Poleni had similar characteristics to the outdoor ones made by Morgagni with a too much protected thermometer. For both Poleni and Morgagni outdoor, the variance is about one tenth of that of the Air Force. Finally, the indoor measurements by Morgagni show the most reduced variability. This poor variability is further reduced in winter, when the severe cold discouraged Morgagni from ventilating his room.

Another useful test to recognize indoor or outdoor readings consists in plotting the temperature of the snowy days (as discussed in

Section 5.2 and

Figure 4). If the thermometer was correctly exposed outside, the plot of the frequency of the snowy days includes negative and near zero temperatures. If the thermometer was kept inside, the peak of frequency is around a positive value (e.g., +5°C that represents the normal indoor temperature of an unheated, manned building of northern Italy).

In the second half of the 18th century, the technology improved, and the thermometers became weather resistant. The thermometers of the network of the

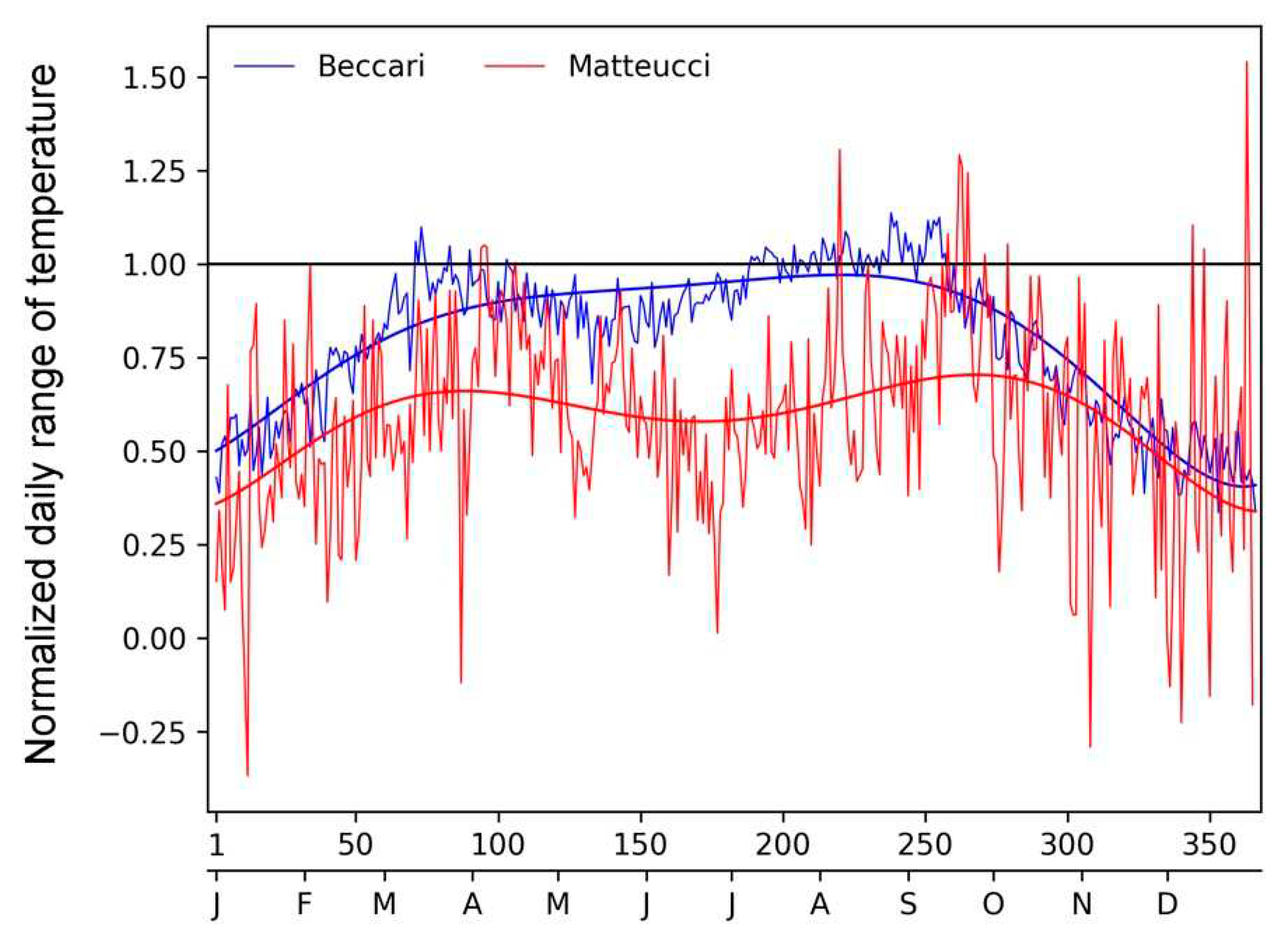

Societas Meteorologica Palatina, Mannheim [

77] were located outside, in positions not reached by the solar radiation, and far from buildings. This was the recommendation, but the efficiency of the free ventilation and the proximity to the wall can be tested with an index representing the normalized daily range of temperature (NDRT) over the calendar year, that is the range of the daily cycle (

Tmax –

Tmin) observed in the EIR, divided by the range of the corresponding calendar day over the modern reference period. As the WMO standard requires thermometers located outdoors, in a free space, NDRT = 1 when the thermometer was freely exposed outdoors, and adequately shielded form direct sunshine and precipitation. When NDRT < 1, the range is penalized (i.e.,

Tmax lower and

Tmin higher) because the thermometer was kept too close to a wall (NDRT slightly less than 1), or in a loggia (NDRT < 1), or indoors (NDRT << 1). As opposed, if the thermometer was not adequately shielded against solar radiation, T

max increases and NDRT > 1. An example of NDRT is shown in

Figure 16 considering Beccari (observations from 1742 to 1765) and Matteucci (from 1787 to 1792) who measured at their homes in Bologna [

46]. The NDRT index shows that Beccari measured correctly from April to October, and that in the cold season the daily cycle was penalized, being reduced to half of its normal cycle. This suggests that in winter the thermometer was kept in a semi-enclosed environment and the data variability was smoothed. NDTR suggests that Matteucci kept the thermometer in a narrow or semi-enclosed space, influenced by the building structures, that smoothed the temperature variability over the whole calendar year, but especially in winter, when the thermometer seems having been kept indoors.

8.2. Stands and Screens

To the best of our knowledge, Toaldo was the first who realized that some radiation caused a bias, and applied shields [

100]. In 1780, he noted that in summer the thermometer was hit by solar radiation during the first measurement in the morning, and applied a piece of cardboard to screen it, as he wrote in the log of 30 June 1780. In 1785, Toaldo hung outside some thermometers exposed to free air, but ‘protected against harm from the sky’ [

101], i.e., sheltered from rain and sunshine. This is the first documentation of screens in Italy.

In EIR, the situation is complex, and each observer must be considered as a separate case, because there was no standardization, and the protection adopted depended on the observer’s sensitivity. Middleton [

13] suggested that screens started to be used after 1835. Böhm et al. [

104] concluded that temperature records taken prior to 1860 could be affected by radiation bias. In 1874, the IMC recommended the use of screens [

97], but it was too early to tell which was best. However, screens were normally used after 1874.

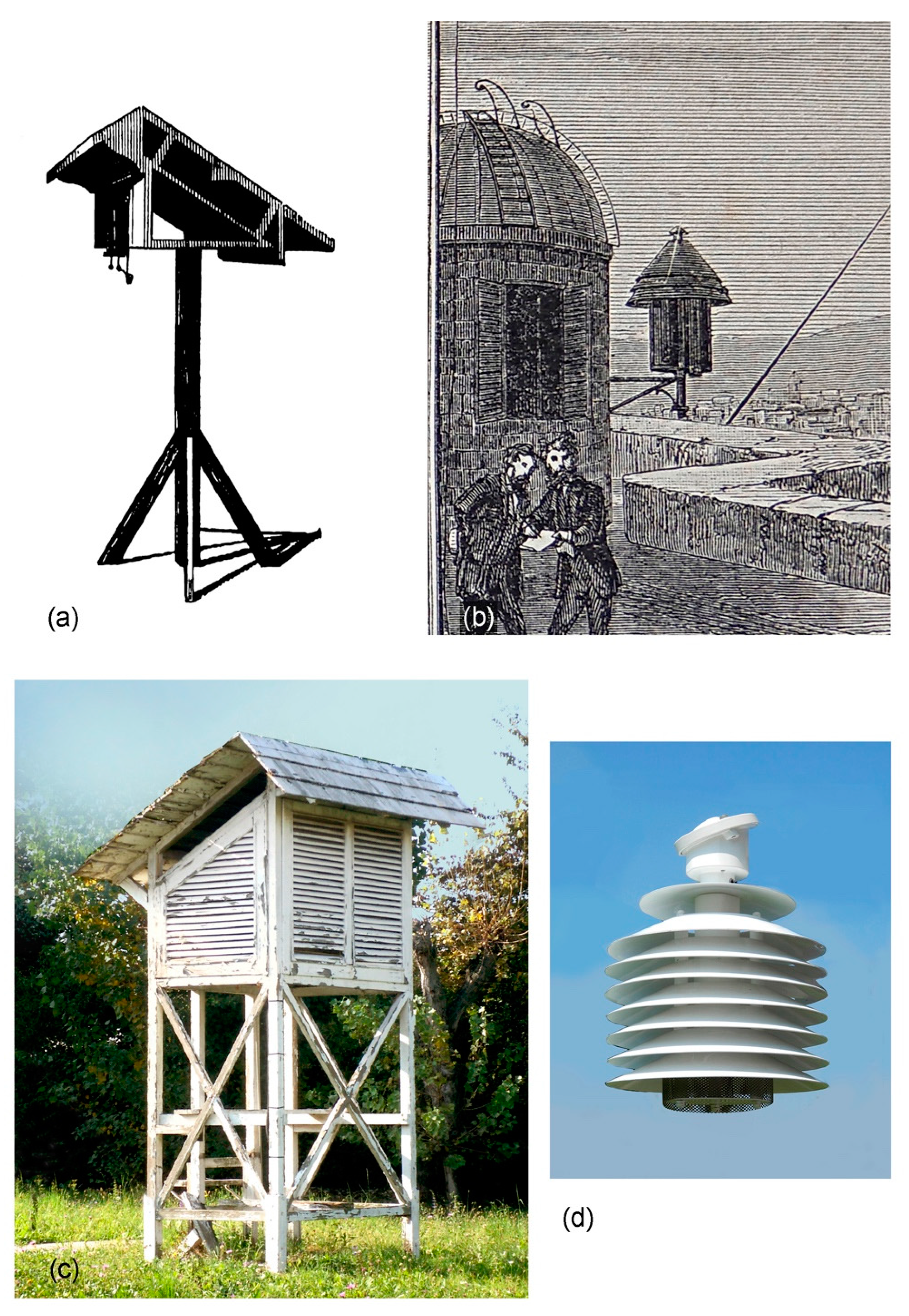

The earliest shelters [

24] that were used around the half of the 19th century, were named ‘stand’ (

Figure 17a) and were constituted of a wooden frame, where thermometers could be hung, a small roof on the top to shield from rain, but without any lateral protection [

102]. Screens against both radiation and rain became popular in the second half of the 19th century, and were metal cylinders with a cap (

Figure 17b), or wooden cages, and finally the louvered Stevenson Screen [

103] (

Figure 17c). In the 20th century, Aitken developed the multi-plate radiation shield (

Figure 17d), originally made of metal, and recently of plastics.

9. Overview of Data Recovery: from Original Readings to ‘Standardized’ Data

In the previous sections, some specific biases of temperature measurements, the related equations and the procedure to correct them, have been presented and discussed. Since the problems encountered are numerous and rather complex, it is convenient to put them in the order in which they are to be addressed, to avoid the risk of concentrating on the details and losing the logical flow of the overall methodology.

For the air thermometer (

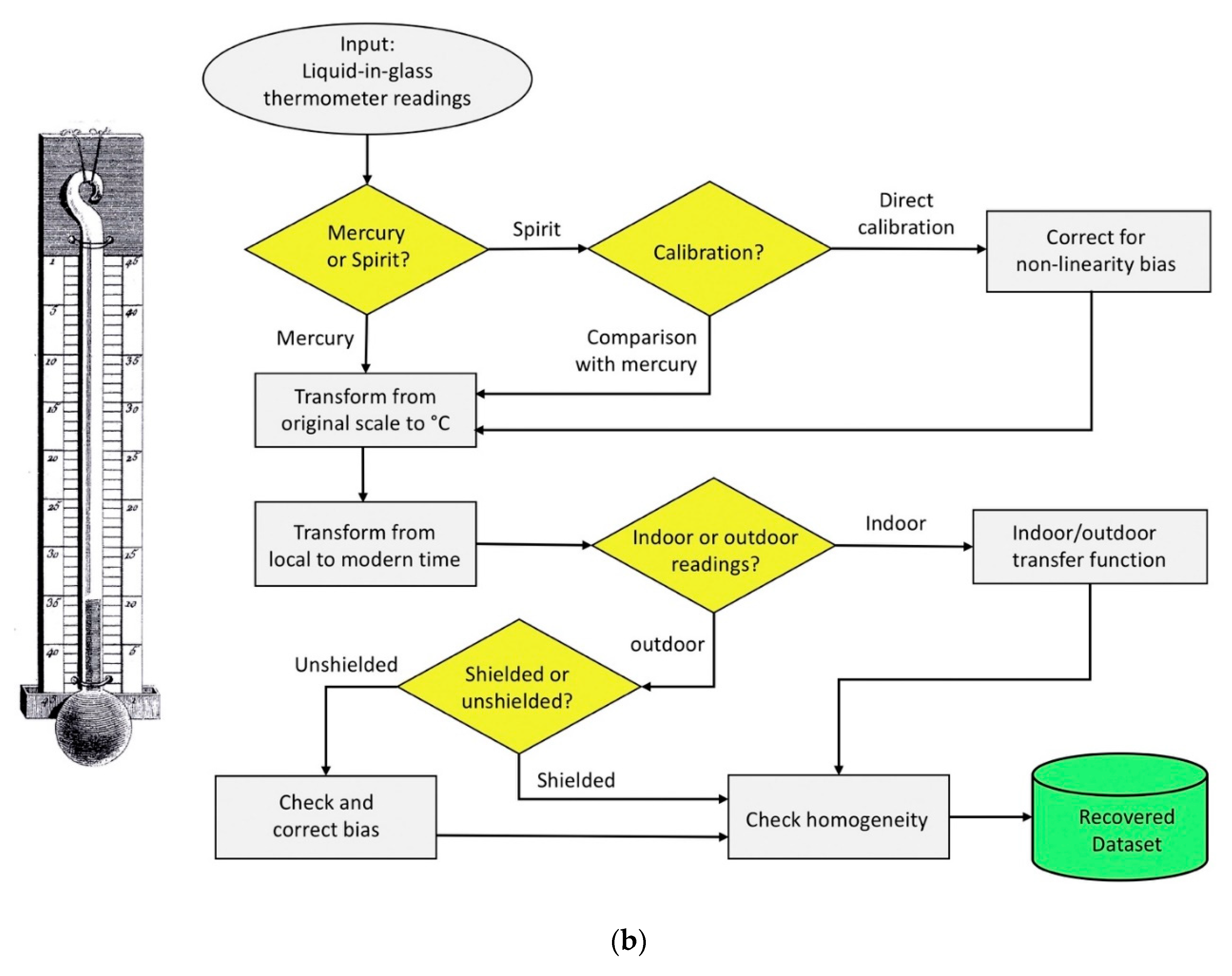

Figure 18a), the first question is whether it was a Stancari or Amontons type. If it was an Amontons, it is necessary to recover the pressure reading too, and correct them for gravity (latitude) and temperature. The correction for the level above the sea or the ground is not necessary, because both the thermometer and the barometer are at the same level. Then comes the correction for the different temperatures that had the thermometer (e.g., 100°C) and the barometer (e.g., 0°C) during the upper calibration point. From here on, the corrections are the same, regardless of thermometer type, i.e., the transformation to °C; the transformation to the modern time frame in UTC+1; the correction for indoor/outdoor readings; and the correction for irregular reading times.

For liquid-in-glass thermometers (

Figure 18b), a key difference occurs between mercury and spirit. Unfortunately, the liquid is not always specified in most metadata. Mercury is the best, because it is linear. Spirit also is almost linear if the thermometer was calibrated by comparison with a mercury thermometer: although the expansion is not linear, the scale is composed of sub-intervals to reflect and compensate for the departures. As opposed, if the spirit thermometer was calibrated with ice and boiling water, it needs to be corrected for the non-linearity, and in summer it underestimates the temperature by some 4-5°C. If the thermometer scale does not reach 100°C, but is limited to 40° or 50°C, this suggests that it was calibrated by comparison with a mercury thermometer and the bias for non-linearity is strongly reduced within ±0.5 °C (

Section 5.4).

10. Conclusions

This paper has made a fundamental distinction between data rescue end data recovery. The former is applied when data are copied, digitized, and made available in image or electronic media, without changes or transformations. The latter is applied when early readings are rescued and deciphered; the arbitrary units of temperature are transformed in °C, and the local time, based on the apparent solar cycle, is transformed in UTC. In addition, the data are corrected for the early instruments, exposure, and observational protocol. Finally, data are homogenized and validated. At this stage, they constitute a recovered dataset ready to be used as input for climate studies.

The methodology is long, complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach, with a number of skills in various disciplines (e.g., history of science, palaeography, old languages, physics, astronomy, and climatology) rarely found in the same person, but easily combined with a team of experts. This paper aims to assist, either as a review or as a guide, to addressing these issues.

Some basic considerations of IMPROVE are still relevant today, e.g., knowledge of the past is one of the keys to interpreting the present and forecasting the future. The answer is conditioned by the quality of our present information, and this gives rise to three further questions: Is our knowledge based on the best available data? Can we improve data quality? Can we learn more from the past by utilising new, unexploited data? Are we really utilising the best strategies to interpret available data? [

12].

To date, a widespread international approach has been devoted to data rescue. However, the recovery of early instrumental series requires a huge and long-lasting effort for data rescue and conversion. This explains why only a limited number of early records has been so far recovered. This paper has been devoted to explain the methodology in the hope of enticing and assisting young colleagues who want to tackle this fundamental issue, and increase the number of high-quality, early instrumental series available for climate studies.

Acknowledgements. The authors are grateful to the anonymous Reviewers, and all the Persons and Institutions that have facilitated this research, and have kindly allowed the consultation and the permission to publish documents, including Gallica, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Springer Nature, INAF Padua, ARPAV, Padua.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of this paper; the conceptualization of this multidisciplinary methodology was established in 1980s by DC, and over the years it was refined together with AdV and FB. All authors contributed to the data recovery, interpretation and discussion of results. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by DC and revised by AdV and FB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This paper presents the results of many years of research made with the financial support of CNR and the European Commission e.g., 1998-99 ENV4-CT97-0511 (IMPROVE); 2006-209 STRIP Contract no.: 017008-2 (Millennium); 2009-2014 FP7-ENV-2008-1 (GA 226973, Climate-for-Culture). This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets recovered during the previous studies mentioned here have been made publicly available as an annex to each publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this paper:

| ABV |

alcohol-by-volume |

| AU |

arbitrary unit |

| CET |

Central European Time |

| DARE |

Data Rescue |

| ECMWF |

European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| EIR |

early instrumental records |

| EoT |

Equation-of-Time |

| IMO |

International Meteorological Committee |

| IMPROVE |

EU Project: Improved Understanding of Past Climatic Variability from Early Daily European Instrumental Sources |

| LFT |

Little Florentine Thermometer |

| NDTR |

normalized daily range of temperature |

| RT |

reading times |

| Tmax

|

maximum daily temperature |

| Tmin

|

minimum daily temperature |

| UTC |

Universal Coordinated Time |

| UTC +1 |

Universal Coordinated Time plus 1 hour |

| WMO |

World Meteorological Organization |

References

- WMO. Guidelines on Best Practices for Climate Data Rescue ISBN 978-92-63-11182-1 WMO Pub No. 1182, Geneva, 2016.

- Brönnimann, S.; Brugnara, Y.; Allan, R.J.; Brunet, M.; Compo, G.P.; Crouthamel, R.I.; Jones, P.D.; Jourdain, S.; Luterbacher, J.; Siegmund, P.; et al. A roadmap to climate data rescue services. Geosci Data J. 2018, 5, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slivinski, L.C.; Compo, G.P.; Whitaker, J.S.; Sardeshmukh, P.D.; Giese, B.S.; McColl, C.; Allan, R.; Yin, X.; Vose, R.; Titchner, H.; et al. Towards a more reliable historical reanalysis: Improvements for version 3 of the Twentieth Century Reanalysis system. Quart. J. Roy. Met. Soc. 2019, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slivinski, L.C.; Compo, G.P.; Sardeshmukh, P.D.; Whitaker, J.S.; McColl, C.; Allan, R.J.; Brohan, P.; Yin, X.; Smith, C.A.; Spencer, L.J.; et al. An evaluation of the performance of the 20th Century Reanalysis version 3. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, A.; Di Napoli, C.; Cloke, H.L.; Kysely, J.; Pappenberger, F.; Sera, F.; Schneider, R.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Acquaotta, F.; Ragettli, M.S.; et al. Evaluation of the ERA5 reanalysis-based Universal Thermal Climate Index on mortality data in Europe. Environmental Research 2021, 8, 111227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, M.N.; Schneider, R.; Masselot, P.; Royé, D.; Armstrong, B.; Kyselý, J.; Orru, H.; Sera, F.; Tong, S.; Lavigne, É.; et al. Comparison of weather station and climate reanalysis data for modelling temperature-related mortality. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgdorf, A.-M.; Brönnimann, S.; Adamson, G.; Amano, T.; Aono, Y.; Barriopedro, D.; Bullon, T.; Camenisch, C.; Camuffo, D.; Daux, V. DOCU-CLIM: A global documentary climate dataset for climate reconstructions. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimani, B.; Auer, I.; Prohom, M.; Nadbath, M.; Paul, A.; Rasol, D. Data rescue in selected countries in connection with the EUMETNET DARE activity. Geoscience Data Journal 2022, 9, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brönnimann, S.; Allan, R.; Ashcroft, L.; Baer, S.; Barriendos, M.; Brázdil, R.; et al. Unlocking Pre-1850 instrumental meteorological records: A Global inventory. BAMS 2019, 100, ES389–ES413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Jones, P. (Eds.) Improved Understanding of Past Climatic Variability from Early Daily European Instrumental Sources; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, Boston, London, 2002; p. 392. ISBN 978-94-010-0371-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Jones, P. Improved Understanding of Past Climatic Variability from Early Daily European Instrumental Sources – Guest Editorial. Clim. Chang. 2002, 53, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, K.W.E. A history of the Thermometer and its use in Meteorology; Hopkins: Baltimore, 1996; p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- Borchi, E.; Macii, R. Termometri e termoscopi; Tipografia Coppini: Florence, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Borchi, E.; Macii, R. Meteorologia a Firenze. Nascita ed evoluzione; Pagnini: Florence, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frisinger, H.H. The History of Meteorology: To 1800; American Meteorological Society: Boston, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg, H.E. Historic Weather Data and Early Meteorological Observations. In Paleoclimate Analysis and Modelling; Hecht, A.D., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 1985; pp. 27–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kington, J. Observing and measuring the weather. In Climates of British Isles: Present Past and Future; Hulme, M., Barrow, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, 1997; pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. Inventing Temperature. Measurement and Scientific Progress. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2004.

- Brázdil, R.; Pfister, C.; Wanner, H.; von Storch, H.; Luterbacher, J. Historical climatology in Europe—the state-of-the-art. Clim. Chang. 2005, 70, 363–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brázdil, R.; Bělínová, M.; Dobrovolný, P.; Mikšovský, J.; Pišoft, P.; Řeznícková, L.; Štěpánek, P.; Valášek, H.; Zahradnícek, P. History of Weather and Climate in the Czech Lands, Vol. IX. Tem- perature and Precipitation Fluctuations in the Czech Lands During the Instrumental Period; Masarykova Univerzita: Brno, 2012; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylak, R.; Majorowicz, J.; Brázdil, R.; Kejan, M. (Eds.) The Polish Climate in the European Context: An Historical Overview; Springer: Dordrecht, 2010; p. 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincasa, F.; De Vincenzi, M.; Fasano, G. Storia della strumentazione meteorologica, nella cultura occidentale; CNR-IBIMET: Florence, 2019; ISBN 978. [Google Scholar]

- Camuffo, D. Microclimate for Cultural Heritage – Measurement, Risk Assessment, Conservation, Restoration and Maintenance of Indoor and Outdoor Monuments, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, New York, 2019; p. 582. ISBN 978-0-444-64106-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philo of Byzantium. De Ingeniis Spiritualibus. Codex Latinus Monacensis 534 (codex of the 14th century); Bayerische Staatsbibliothek: Munich, 2nd or 3rd Century BC.

- Heron of Alexandria. Spiritalia. Harleian Collection No 5605; British Museum: London, c.10–70 AD.

- Commandino, F. Heronis Alexandrini Spiritalium liber. A Federigo Commandino Urbinate, ex Graeco, nuper in Latinum conversus; Frisolini: Urbino, 1575. [Google Scholar]

- Aleotti, G.B. Artifitiosi et Curiosi Moti Spiritali di Herrone; Baldini: Ferrara, 1589. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, A. Spiritali di Herone Alessandrino ridotti in lingua volgare da Alessandro Giorgi da Urbino. Ragusi: Urbino, 1592.

- Della Porta, G.B. Magiae Naturalis sive de Miraculis Rerum Naturalium Libri Viginti; Hempelius: Frankfurt, 1607. [Google Scholar]

- Sanctorius, S. Commentaria in Artem Medicam; pars 3, Coll. 229; Somasco: Venice, 1612. [Google Scholar]

- Sanctorius, S. Commentaria in primam fen primi libri Canonis Avicennae; Sarcina: Venice, 1625. [Google Scholar]

- Fludd, R. (alias De Fluctibus, R.) Tractatus secundus, de naturae simia seu technica macrocosmi historia; Roetelii: Frankfurt, 1624. [Google Scholar]

- Fludd, R. (alias De Fluctibus, R.) Philosophia sacra & vere Christiana seu Meteorologia Cosmica; Bryan: Frankfurt, 1626. [Google Scholar]

- Fludd, R. (alias De Fluctibus, R.) Philosophia Moysaica in qua sapientia et scientia creationis explicantur; Ramazzeni: Gouda, 1638. [Google Scholar]

- Magalotti, L. Saggi di naturali esperienze fatte nell’Accademia del Cimento; Cocchini: Florence, 1666. [Google Scholar]

- Targioni Tozzetti, G. Notizie degli aggrandimenti delle Scienze Fisiche accaduti in Toscana nel corso di anni LX del secolo XVII; Tomo I; Bouchard: Florence, 1780. [Google Scholar]

- Antinori, V. Notizie istoriche relative all’Accademia del Cimento; Tipografia Galileiana, Florence, 1841.

- Camuffo, D.; della Valle, A.; Becherini, F.; Rousseau, D. The earliest temperature record in Paris, 1658–1660, by Ismaël Boulliau, and a comparison with the contemporary series of the Medici Network (1654–1670) in Florence. Clim. Chang. 2020, 162, 903–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Bertolin, C. The earliest temperature observations in the World: the Medici Network (1654-1670). Clim. Chang. 2012, 111, 335–363 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Bertolin, C. The earliest spirit-in-glass thermometer and a comparison between the earliest period of the Central England Temperature series and the instrumental observations of two Italian stations of the Medici Network, active 1654-1670. Weather 2012, 8, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amontons, G. Discours sur quelques propriétés de l'Air & le moyen d'en connoître la température dans tous les climats de la Terre. Mémoires de mathématique et de physique; Martin Coignard & Guerin: Paris, 1702; pp. 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Poleni, G. Johannis Poleni miscellanea hoc Est: I Dissertatio de Barometris et thermometris; Aloysium Pavinum: Venice, 1709. [Google Scholar]