Submitted:

02 August 2023

Posted:

04 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast and Plant Culture

2.2. Harvesting

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.3.1. Chlorophyll Concentrations and Fluorescence Determination

2.3.2. Fungal Growth and Root Infection under Different NaCl Concentrations

2.3.3. Determination of Ascorbate and Glutathione Concentrations

2.3.4. Soluble Sugar and PROTEIN determination

2.3.5. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

2.3.6. Determination of H2O2, Proline, and MDA Concentrations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

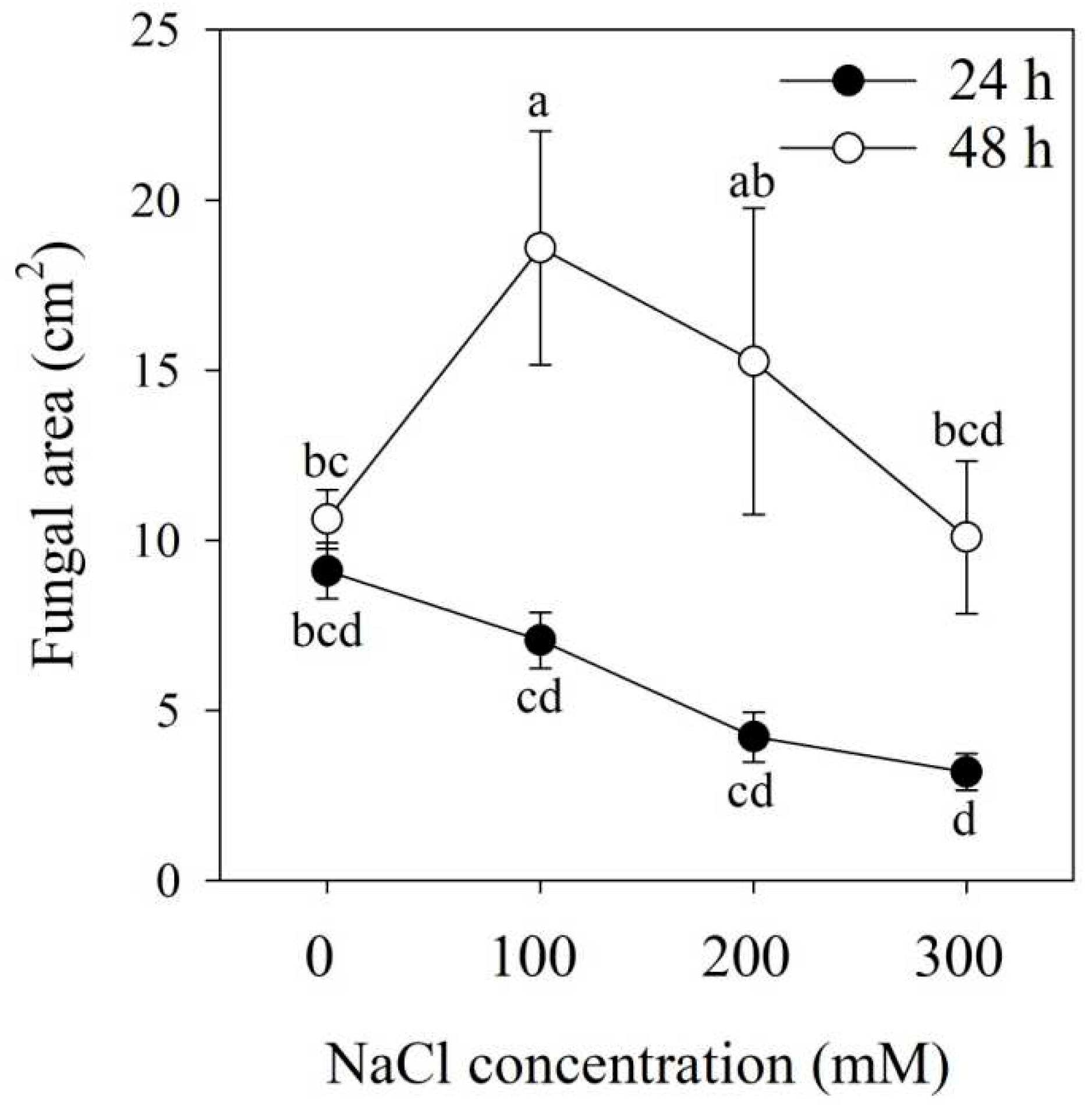

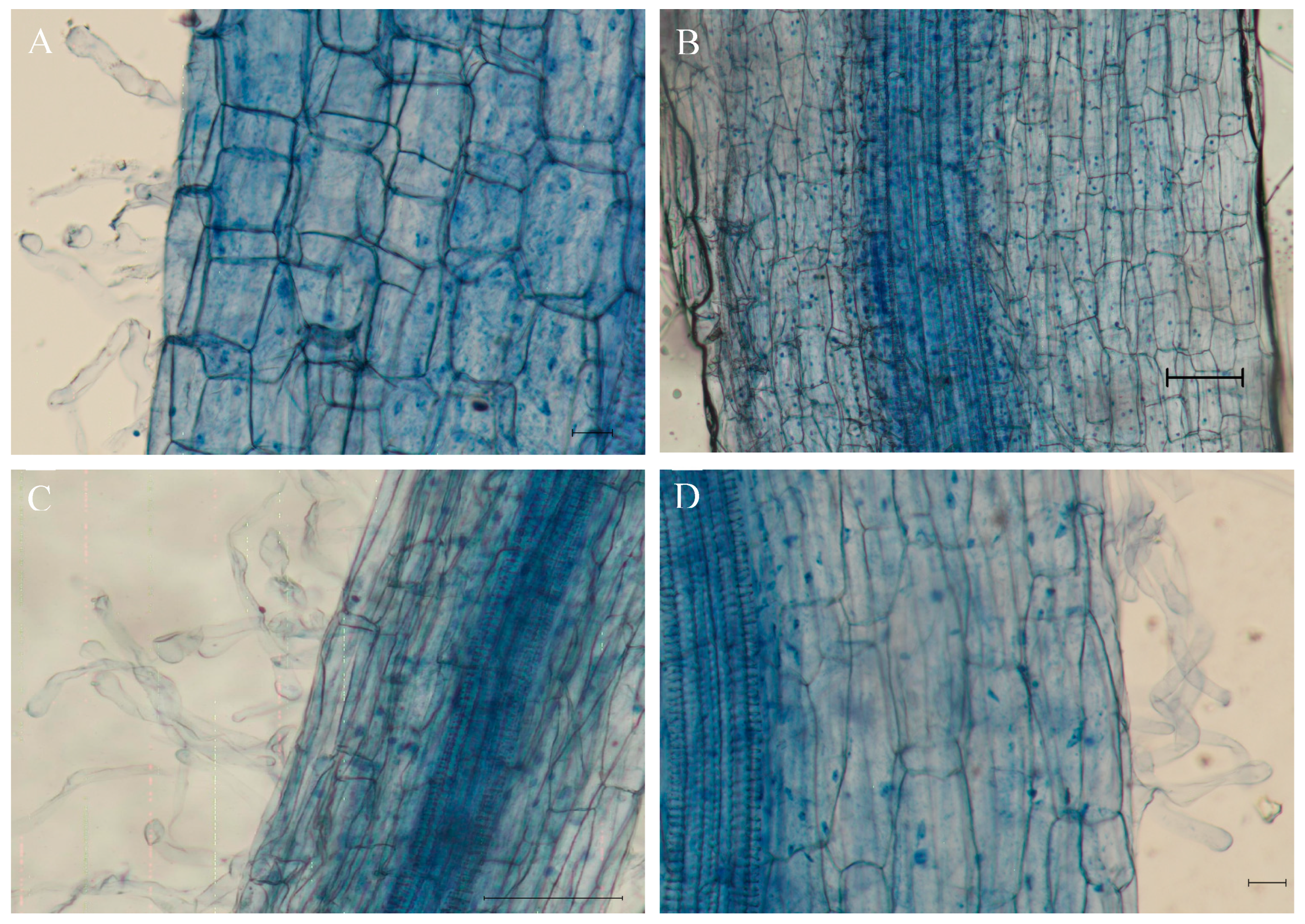

3.1. Yeast Growth and Infection under Different NaCl Concentrations

3.2. Megu Effects on Chlorophyll Concentrations and Fluorescence Parameters in Tomato Plants under Salt Stress

3.3. Effects of Megu Inoculation on Biomass Accumulation in Tomato Plants under Salt Stress

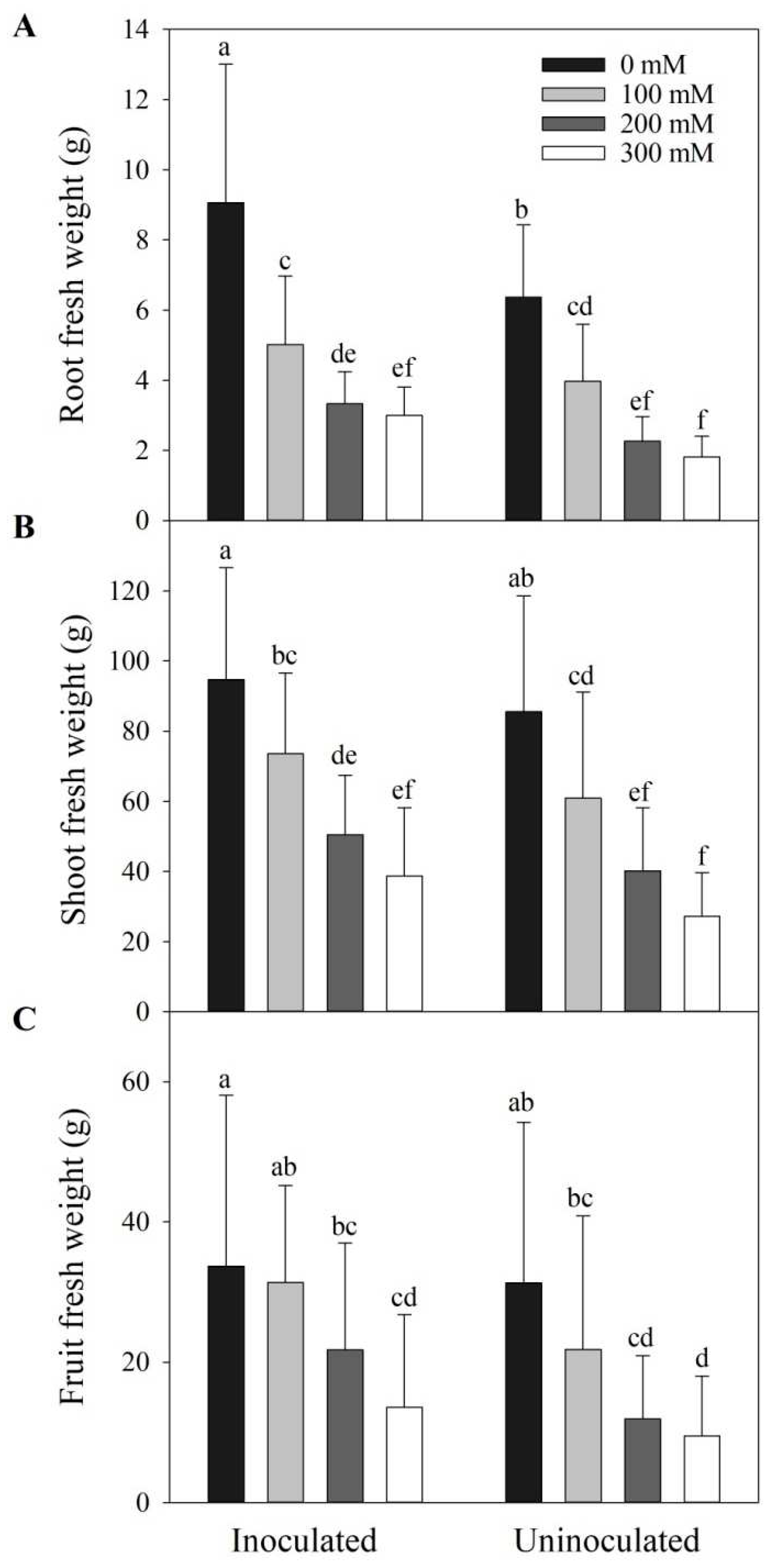

3.4. Megu Inoculation Regulated Levels of Antioxidants and Osmolytes in Tomat Plants under Salt Stress

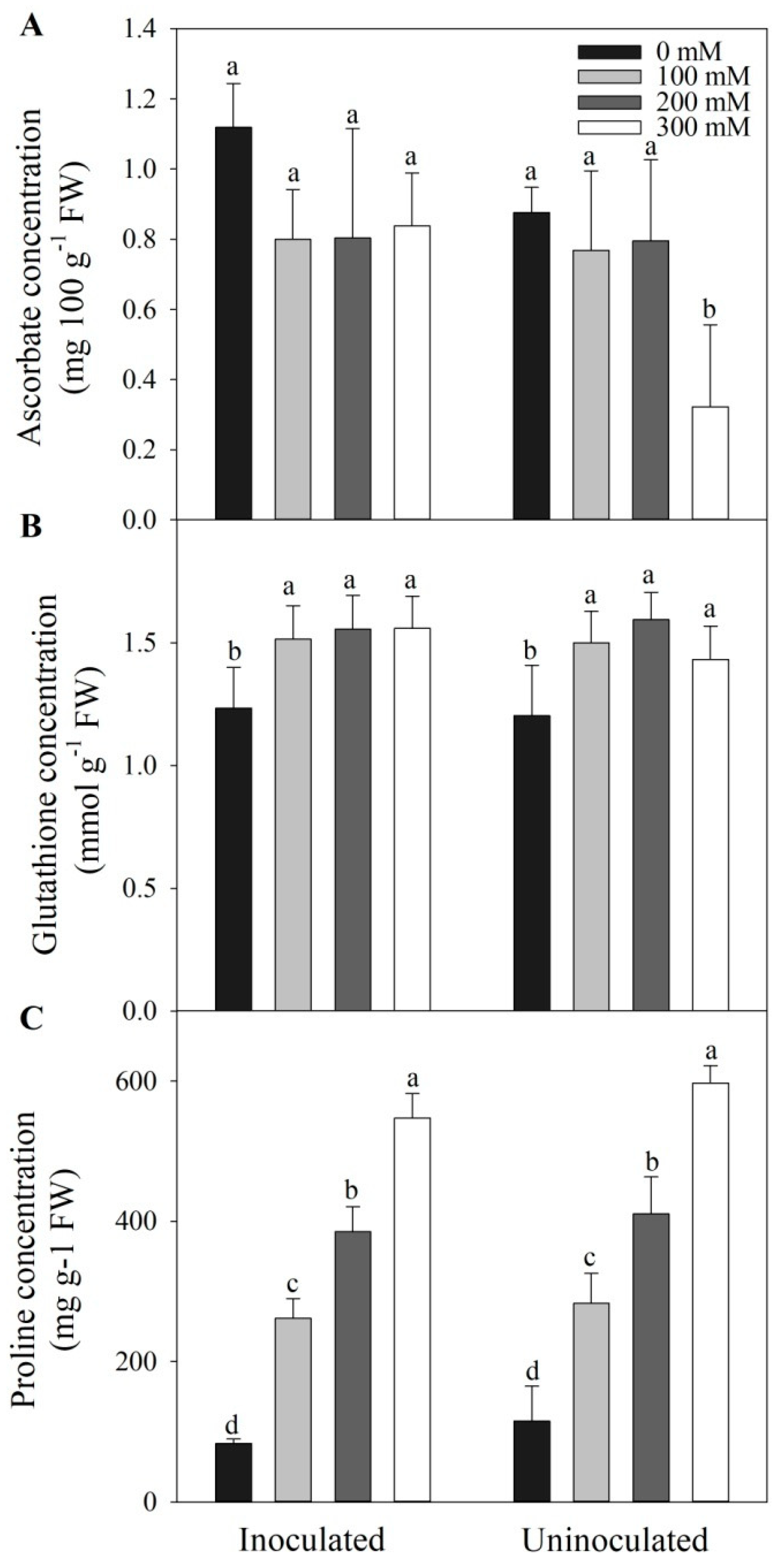

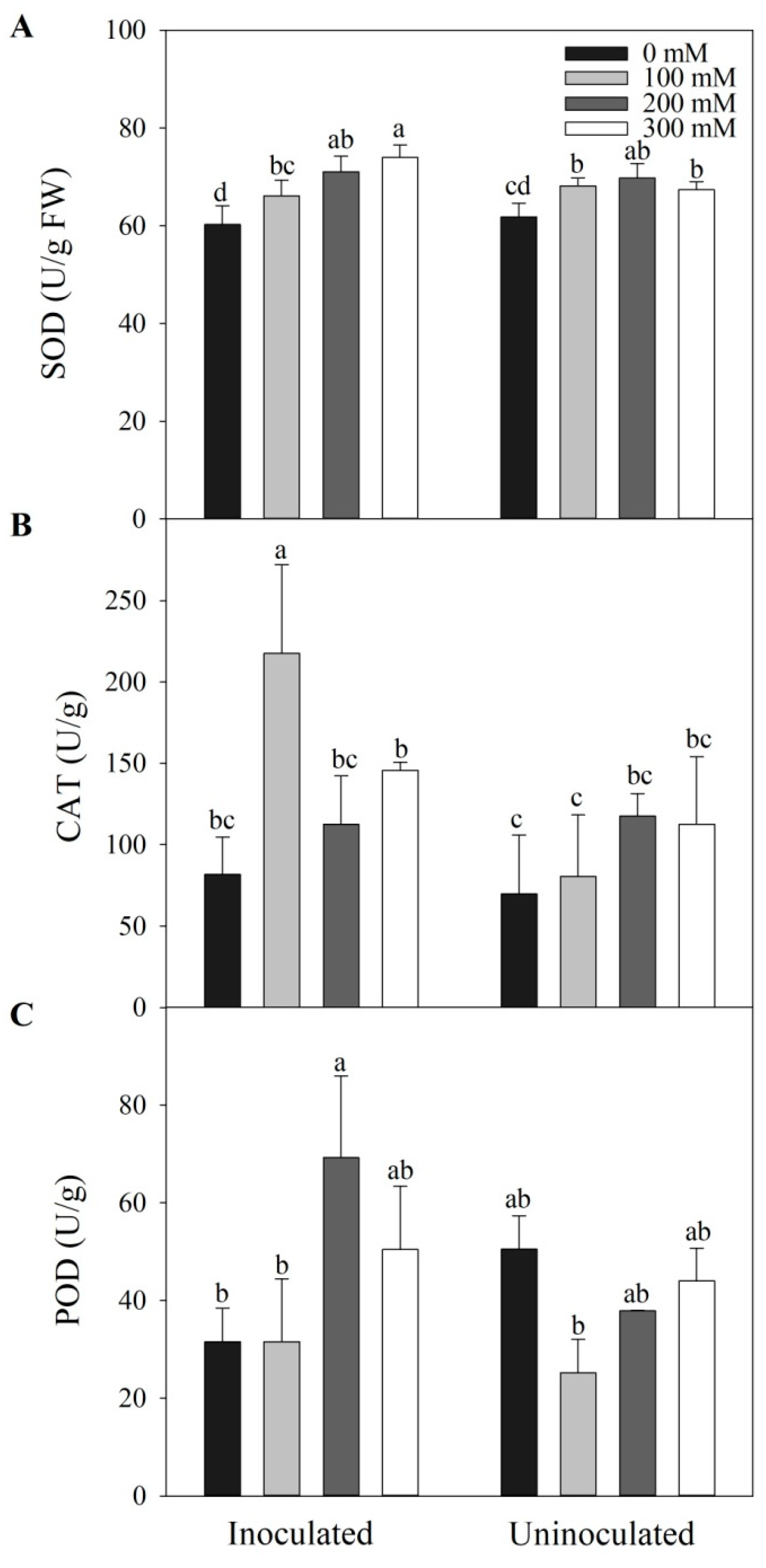

3.5. Megu Increased Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Tomato Plants under Salt Stress

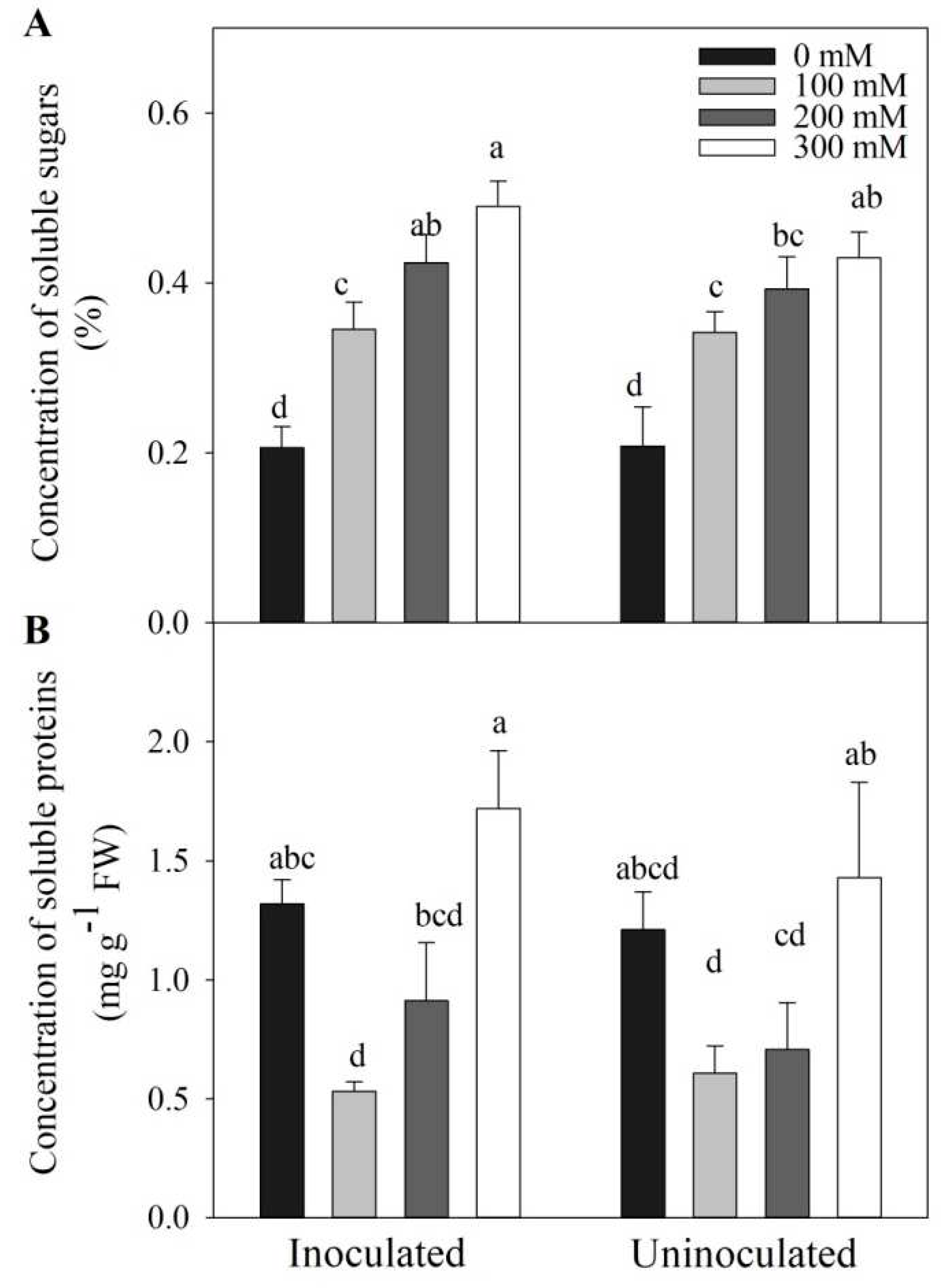

3.6. Inoculation Effects on Soluble Sugar and Protein Levels in Tomato Plants under Salt Stress

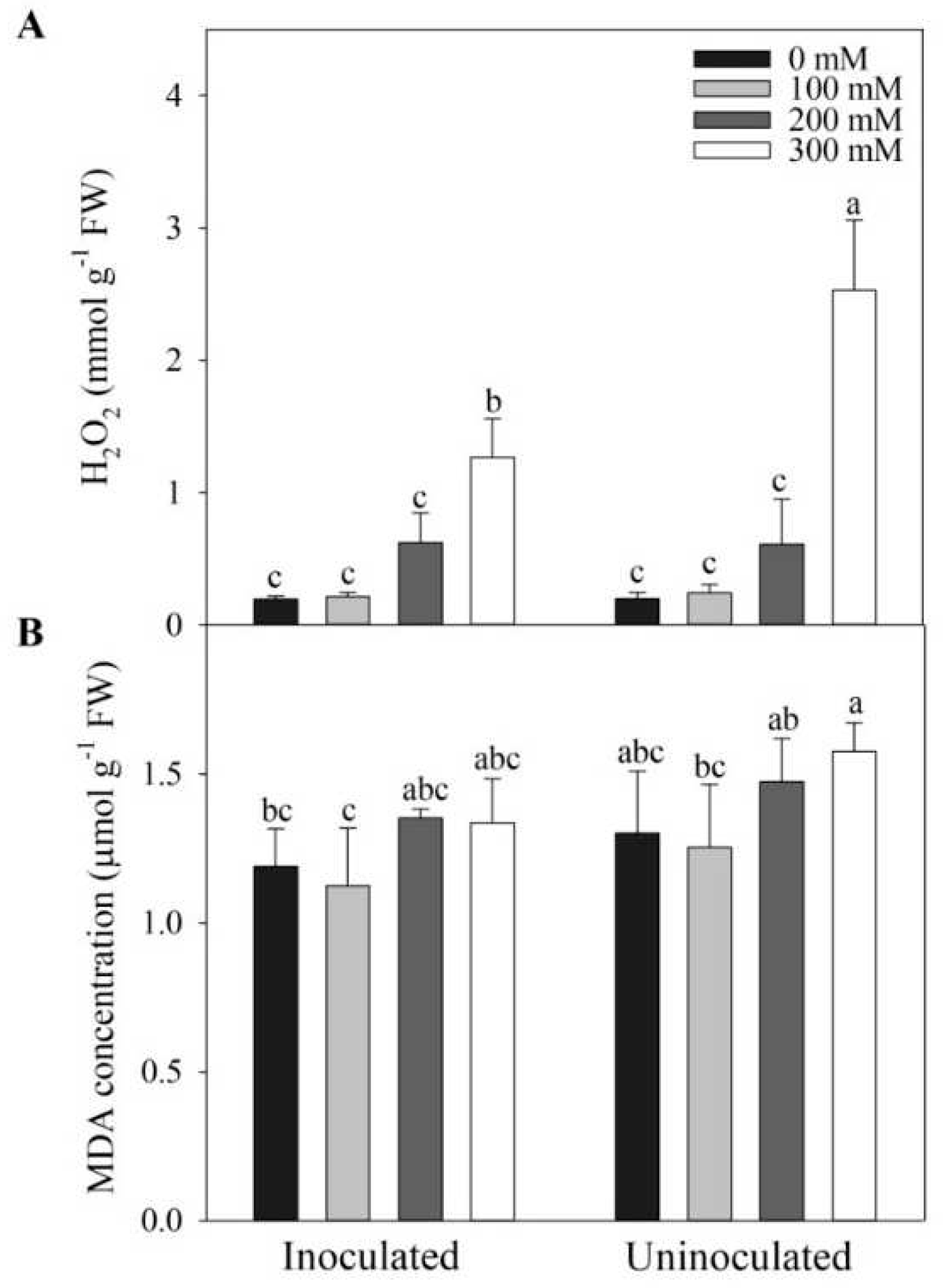

3.7. Effects of Megu Inoculation on H2O2 and MDA in Tomato Plants under Salt Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. Megu Inoculation Regulated ROS Scavenging in Tomato Plants under Salt Stress

4.2. Effect of Megu Inoculation on Osmoregulation of Plants under Salt Stress

4.3. Effects of Megu Inoculation on Growth of Tomato Plants under Salt Stress

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/soils-portal/soil-management/management-of-some-problem-soils/salt-afected-soils/more-information-on-salt-afected-soils/en/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Jamil, A.; Riaz, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Gene expression profiling of plants under salt stress. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, Y.; Sun, H.; Shi, X.; Pan, H.; Chen, Y. Effects of salt stress on growth and root development of two oak seedlings. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, J.; Dai, T.; Cao, W.; Pu, H.; Jiang, D. Salt stress increases content and size of glutenin macropolymers in wheat grain. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, P.; Kanagendran, A.; Samaddar, S.; Pazouki, L.; Sa, T.-M.; Niinemets, Ü. Inoculation of Brevibacterium linens RS16 in Oryza sativa genotypes enhanced salinity resistance: Impacts on photosynthetic traits and foliar volatile emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, B.; Huang, B. Mechanism of salinity tolerance in plants: Physiological, biochemical, and molecular characterization. Int. J. Genom. 2014, 2014, 701596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Y.; Singh, P.; Siddiqui, H.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Salinity induced physiological and biochemical changes in plants: An omic approach towards salt stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 156, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002, 53, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capula-Rodríguez, R.; Valdez-Aguilar, L.A.; Cartmill, D.L.; Cartmill, A.D.; Alia-Tejacal, I. Supplementary calcium and potassium improve the response of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) to simultaneous alkalinity, salinity, and boron stress. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2016, 47, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, A.; Huang, J. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on growth and nitrogen uptake of Chrysanthemum morifolium under salt stress. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çiçek, N.; Oukarroum, A.; Strasser, R.J.; Schansker, G. Salt stress effects on the photosynthetic electron transport chain in two chickpea lines differing in their salt stress tolerance. Photosynth. Res. 2018, 136, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methenni, K.; Abdallah, M.B.; Nouairi, I.; Smaoui, A.; Ammar, w.B.; Zarrouk, M.; Youssef, N.B. Salicylic acid and calcium pretreatments alleviate the toxic effect of salinity in the Oueslati olive variety. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 233, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Chanratana, M.; Kim, K.; Seshadri, S.; Sa, T. Impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on photosynthesis, water status, and gas exchange of plants under salt stress–a meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisarum, R.; Theerawitaya, C.; Samphumphuang, T.; Polispitak, K.; Thongpoem, P.; Singh, H.P.; Cha-um, S. Alleviation of salt stress in upland rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica cv. Leum Pua) using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation. Front. Plant Sci. [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.B.; Wang, W.J.; Fan, X.X.; Kurakov, A.V.; Liu, Y.F.; Song, F.Q.; Chang, W. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can ameli-orate salt stress in Elaeagnus angustifolia by improving leaf photosynthetic function and ultrastructure. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Galán, C.; Calvo-Polanco, M.; Zimmermann, S.D. Ectomycorrhizal symbiosis helps plants to challenge salt stress conditions. Mycorrhiza 2019, 29, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, G.; Yao, J.; Deng, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhao, R.; Lin, S.; et al. Amelioration of nitrate uptake under salt stress by ectomycorrhiza with and without a Hartig net. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 1951–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiazek, J.J.; Equiza, M.A.; Karst, J.; Senorans, J.; Wartenbe, M.; Calvo-Polanco, M. Role of urban ectomycorrhizal fungi in improving the tolerance of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) seedlings to salt stress. Mycorrhiza 2019, 29, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmus, N.; Yesilyurt, A.M.; Pehlivan, N.; Karaoglu, S.A. Salt stress resilience potential of a fungal inoculant isolated from tea cultivation area in maize. Biologia 2017, 72, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kord, H.; Fakheri, B.; Ghabooli, M.; Solouki, M.; Emamjomeh, A.; Khatabi, B.; Sepehri, M.; Salekdeh, G.H.; Ghaffari, M.R. Salinity-associated microRNAs and their potential roles in mediating salt tolerance in rice colonized by the endophytic root fungus Piriformospora indica. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2019, 19, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, G.C.; Nunes, K.G.; Soares, M.A.; de Siqueira, K.A.; Lima, W.C.; Neves, A.L.R.; de Lacerda, C.F.; Filho, E.G. Dark sep-tate endophytic fungi mitigate the effects of salt stress on cowpea plants. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzouina, M.; Kouadria, R.; Lotmani, B. Fungal endophytes alleviate salt stress in wheat in terms of growth, ion homeostasis and osmoregulation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 130, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Niu, M.-X.; Feng, C.-H.; Li, H.-G.; Su, Y.; Su, W.-L.; Pang, H.; Yang, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, H.-L.; et al. PeSTZ1 confers salt stress tolerance by scavenging the accumulation of ROS through regulating the expression of PeZAT12 and PeAPX2 in Populus. Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 1292–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkowni, R.; Jodeh, S.; Hamed, R.; Samhan, S.; Daraghmeh, H. The impact of Pseudomonas putida UW3 and UW4 strains on photosynthetic activities of selected field crops under saline conditions. Int. J. Phytoremed. 2019, 21, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafi, D.; Delangiz, N.; Lajayer, B.A.; Ghorbanpour, M. An overview on improvement of crop productivity in saline soils by halotolerant and halophilic PGPRs. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul Jan, F.; Hamayun, M.; Hussain, A.; Iqbal, A.; Jan, G.; Khan, S.A.; Khan, H.; Lee, I.-J. A promising growth promoting Meyerozyma caribbica from Solanum xanthocarpum alleviated stress in maize plants. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul Jan, F.; Hamayun, M.; Hussain, A.; Jan, G.; Iqbal, A.; Khan, A.; Lee, I.-J. An endophytic isolate of the fungus Yarrowia lipo-lytica produces metabolites that ameliorate the negative impact of salt stress on the physiology of maize. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, M. Efficiency of yeast in enhancement of the oxidative defense system in salt-stressed flax seedlings. Acta Biol. Hung. 2013, 64, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, C.; Rus, A.M.; Bolarín, M.C.; López-Coronado, J.M.; Arrillaga, I.; Montesinos, C.; Caro, M.; Serrano, R.; Moreno, V. The yeast HAL1 gene improves salt tolerance of transgenic tomato. Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; Norton, R.S. Metabolic changes induced during adaptation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to a water stress. Arch. Microbiol. 1991, 156, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Baek, J.-H.; Park, N.-H.; Kim, C. Complete genome sequence of halophilic yeast Meyerozyma caribbica MG20W isolated from rhizosphere soil. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00127–00115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.-l.; Liao, Y.-y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.-l. Comparative transcriptome analysis of salt tolerance mechanism of Meyerozyma guilliermondii W2 under NaCl stress. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, I.; Capusoni, C.; Molinari, F.; Musso, L.; Pellegrino, L.; Compagno, C. Marine microorganisms for biocatalysis: Selective hydrolysis of nitriles with a salt-resistant strain of Meyerozyma guilliermondii. Mar. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, X.; Apaliya, M.T.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Gu, X.; Zhang, H. Control of postharvest blue mold decay in pears by Meyerozyma guilliermondii and it’s effects on the protein expression profile of pears. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 136, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirman, B.; Erten, H. Biocontrol ability and action mechanisms of Aureobasidium pullulans GE17 and Meyerozyma guilliermon-dii KL3 against Penicillium digitatum DSM2750 and Penicillium expansum DSM62841 causing postharvest diseases. Yeast 2020, 37, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Huang, Y.; Lian, S.; Saleem, M.; Li, B.; Wang, C. Improving the biocontrol efficacy of Meyerozyma guilliermondii Y-1 with melatonin against postharvest gray mold in apple fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 171, 111351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Sun, C.; Guan, X.; Lian, S.; Li, B.; Wang, C. Biocontrol efficiency of Meyerozyma guilliermondii Y-1 against apple postharvest decay caused by Botryosphaeria dothidea and the possible mechanisms of action. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 338, 108957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Castrillón, M.; Jaramillo-Garcia, V.P.; Rosa, P.D.; Landell, M.F.; Vu, D.; Fabricio, M.F.; Ayub, M.A.Z.; Robert, V.; Henriques, J.A.P.; Valente, P. The oleaginous yeast Meyerozyma guilliermondii BI281A as a new potential biodiesel feedstock: Selection and lipid production optimization. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmüller, D.; Ullmann, N.; Zwirzitz, A. Identification of genes involved in xylose metabolism of Meyerozyma guilliermondii and their genetic engineering for increased xylitol production. AMB Express 2020, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, S.A.M.; Hashem, M.; Nafady, N.A.; Sayed, M.A.; Alshehri, A.M.; El-Shaboury, G.A. Controllable biogenic synthesis of intracellular silver/silver chloride nanoparticles by Meyerozyma guilliermondii KX008616. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, S.S.; Ruas, F.A.D.; Barboza, N.R.; de Oliveira Neves, V.G.; Leão, V.A.; Guerra-Sá, R. Manganese (Mn2+) tolerance and biosorption by Meyerozyma guilliermondii and Meyerozyma caribbica strains. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4538–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruas, F.A.D.; Barboza, N.R.; Castro-Borges, W.; Guerra-Sá, R. Manganese alters expression of proteins involved in the oxida-tive stress of Meyerozyma guilliermondii. J. Proteom. 2019, 196, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Gao, H.; Qian, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Dong, W.; Xin, F.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, M. Biotechnological applications of the non-conventional yeast Meyerozyma guilliermondii. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 46, 107674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertini, E.V.; Leguina, A.C.d.V.; Castellanos, L.I.; Nieto Peñalver, C.G. Endophytic microorganisms Agrobacterium tumefaciens 6N2 and Meyerozyma guilliermondii 6N serve as models for the study of microbial interactions in colony biofilms. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zhang, S.; Wu, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, J.; Dong, W.; Qian, X.; Jiang, M.; Xin, F. The draft genome sequence of Meyero-zyma guilliermondii strain YLG18, a yeast capable of producing and tolerating high concentration of 2-phenylethanol. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsalan, R.; Mathew, D. Draft genome of Meyerozyma guilliermondii strain vka1: A yeast strain with composting potential. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2020, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.R. Determination of carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, K.; Johnson, J.M.; Drzewiecki, C.; Oelmüller, R. Fungal staining tools to study the interaction between the beneficial endophyte Piriformospora indica with Arabidopsis thaliana roots. J. Endocyt. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj, K.L.; Kaur, G. Spectrophotometric determination of L-ascorbic acid in vegetables and fruits. Analyst, 1981, 106: 117-120. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, O.W. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulphide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal. Biochem. 1980, 106, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreywood, R. Qualitative test for carbohydrate material. Ind. Eng. Chem. Anal. Ed. 1946, 18, 499–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Bio-Chem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: Protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Kao, C.H. NaCl induced changes in ionically bound peroxidase activity in roots of rice seedlings. Plant Soil 1999, 216, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, A.; Karim, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Potassium-induced regula-tion of cellular antioxidant defense and improvement of physiological processes in wheat under water deficit condition. Phyton 2021, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinet. Stoichiom. Fat. Acid Peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liang, W.; Cheng, H.; Wang, H.; Lv, D.; Wang, W.; Liang, M.; Miao, C. NADPH Oxidase-derived ROS promote mito-chondrial alkalization under salt stress in Arabidopsis root cells. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1856546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; He, Q.; Tang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Lv, M.; Liu, H.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. The miR172/IDS1 signal-ing module confers salt tolerance through maintaining ROS homeostasis in cereal crops. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Costa, A.; Nakayama, H.; Katsuhara, M.; Shinmyo, A.; Horie, T. OsHKT2;2/1-mediated Na+ influx over K+ uptake in roots potentially increases toxic Na+ accumulation in a salt-tolerant landrace of rice Nona Bokra upon salinity stress. J. Plant Res. 2016, 129, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeranagamallaiah, G.; Chandraobulreddy, P.; Jyothsnakumari, G.; Sudhakar, C. Glutamine synthetase expression and pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase activity influence proline accumulation in two cultivars of foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) with differential salt sensitivity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 60, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan-Ampudia, C.S.; Testerink, C. Salt stress signals shape the plant root. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Jalmi, S.K.; Bhagat, P.K.; Verma, N.; Sinha, A.K. A bHLH transcription factor, MYC2, imparts salt intolerance by regulating proline biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 2560–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.; Alfaro-Cuevas, R.; López-Bucio, J. Trichoderma spp. improve growth of Arabidopsis seedlings under salt stress through enhanced root development, osmolite production, and Na+ elimination through root exudates. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, F.; Ge, H.; Tian, F.; Yang, T.; Ma, K.; Zhang, Y. Trichoderma harzianum mitigates salt stress in cucumber via multiple responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 170, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, N.; Sa, R.; Jiang, L. Effect of salt stress on antioxidant enzymes, soluble sugar and yield of oat. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 5, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boriboonkaset, T.; Theerawitaya, C.; Yamada, N.; Pichakum, A.; Supaibulwatana, K.; Cha-um, S.; Takabe, T.; Kirdmanee, C. Regulation of some carbohydrate metabolism-related genes, starch and soluble sugar contents, photosynthetic activities and yield attributes of two contrasting rice genotypes subjected to salt stress. Protoplasma 2013, 250, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabivand, S.; Parvaneh, A.; Aliloo, A.A. Root endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica affected growth, cadmium partition-ing and chlorophyll fluorescence of sunflower under cadmium toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 145, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ważny, R.; Rozpądek, P.; Domka, A.; Jędrzejczyk, R.J.; Nosek, M.; Hubalewska-Mazgaj, M.; Lichtscheidl, I.; Kidd, P.; Turnau, K. The effect of endophytic fungi on growth and nickel accumulation in Noccaea hyperaccumulators. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 144666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzur, M.E.; Garello, F.A.; Omacini, M.; Schnyder, H.; Sutka, M.R.; García-Parisi, P.A. Endophytic fungi and drought toler-ance: Ecophysiological adjustment in shoot and root of an annual mesophytic host grass. Funct. Plant Biol. 2022, 49, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wei, Q.; Deng, J.; Zhang, W. Changes in gas exchange, root growth, and biomass accumulation of Platycladus orientalis seedlings colonized by Serendipita indica. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pigment level (mg/g FW) | NaCl concentrations (mM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 200 | 300 | ||

| Chl a | N | 17.29 a | 18.58a | 18.06a | 16.41ab |

| Y | 17.92 a | 14.16 b | 18.98a | 18.05 a | |

| Chl b | N | 7.31abc | 8.95a | 7.94 ab | 7.09bc |

| Y | 7.54ab | 5.74c | 8.51 ab | 7.97 ab | |

| Carotenoids | N | 2.89ab | 2.84ab | 3.10a | 2.83 ab |

| Y | 3.08 a | 2.52 b | 3.02 a | 2.92 ab | |

| Total Chl | N Y |

24.60 a 25.46 a |

27.53a 19.90b |

26.00 a 27.49 a |

23.51 ab 26.01a |

| Fluorescence parameter | NaCl concentrations (mM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 200 | 300 | |||

| Y(II) | N | 0.56 e | 0.61 b | 0.58 d | 0.58 d | |

| Y | 0.59 c | 0.58 d | 0.61 b | 0.62 a | ||

| ETR | N | 29.51 g | 31.88 c | 30.51 d | 30.30 de | |

| Y | 30.19 e | 29.79 f | 32.15 b | 32.71 a | ||

| qP | N | 0.90 g | 0.95 d | 0.91 f | 0.93 c | |

| Y | 0.93 e | 1.00 a | 0.98 b | 0.96 c | ||

| qL | N | 0.78 f | 0.86 d | 0.79 f | 0.84 e | |

| Y | 0.85 de | 1.01 a | 0.94 b | 0.90 c | ||

| Y(NO) | N | 0.42 a | 0.37 c | 0.40 b | 0.40 b | |

| Y | 0.41a | 0.40 b | 0.37 c | 0.36 d | ||

| Fv/Fm | N | 0.62 c | 0.63 b | 0.62 c | 0.62 c | |

| Y | 0.60d | 0.60 d | 0.64 a | 0.64 a | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).