1. Introduction

Dental caries, is an important disease in children, and being the most prevalent disease in oral cavity at this stage of life 1. Nowadays, it has been reported in some countries with a prevalence greater than 90% in 6-year-old population therefore that the authors have considered to be a public health crisis 2.

This disease destroys dental hard tissue affecting pulp vitality with a high risk of development of pulp and periapical lesions 3. To eradicate this polymicrobial infection with aerobic and anaerobic bacteria 4-5, it has been proposed the non-instrumentation endodontic treatment (NIET) using a mixture of antibacterial drugs placed over the pulp floor 6, with the objective to prevent over instrumentation of root canals and irritation of periapical tissue decreasing chair time to only one visit 7, since endodontic treatment of primary teeth could be a challenge to the presence of root resorption and the successor tooth 6.

Antibiotic pastes have been proposed in endodontic therapy by their antimicrobial capacity and low cost 8. Since, if infected primary teeth are not effectively treated, premature tooth extraction could be necessary, affecting masticatory function, maxillofacial and systemic growth 9 and increasing the risk of malocclusions 10. Several antibiotics have been used in the preparation of these pastes, such as ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, minocycline, clindamycin 11, ornidazole 12 or rifampicin 13. Interestingly, a mixture of chloramphenicol 500 mg, tetracycline 500 mg, zinc oxide 1000 mg and one drop of eugenol (CTZ) in a ratio of 1:1:2 was introduced for Cappiello in 1964 showing promising results 14. The success of this paste is due to its composition, since, chloramphenicol is a broad spectrum antibiotic 15 with high solubility and bacteriostatic effect against gram positive anaerobic and gram negative aerobic bacteria 16; the tetracycline is a broad-spectrum bacteriostatic agent that inhibits bacterial protein synthesis 17, and also the antimicrobial capacity of the zinc oxide supposedly effected by the production of hydrogen peroxide 18, however, some authors it has been reported that the zinc oxide alone has no inhibitory effect and it is the eugenol which has the antimicrobial action 19-20.

In the clinic are used several other types of paste to disinfection of the root canal system and also to create a favorable environment for endodontic regeneration such as the Triple Antibiotic Paste (TAP) which is composed by ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline 21-22 . Herein, vehicles are well-known to be capable of interfering in several properties of endodontic materials, including cytotoxicity 23-25, specifically in TAP, it has been highlighted the importance of the vehicle since the use of the combination of Polyethylene Glycol and Propylene Glycol (PG) mixed as vehicle exhibit less cytotoxicity than when water is used 26. In addition, the change of vehicle can interfere in the antimicrobial capabilities of the TAP, since some of them can improve this property against some microorganism 27.

Actually. it has been reported that antibiotic resistance decreases the antibacterial properties of endodontic filling pastes for root canal treatment 13, which highlights the importance of looking for vehicles that enhance the antimicrobial effects of these pastes. In the CTZ paste the conventional vehicle recommended by Cappiello it is the eugenol 14, however other type of substance can be tested to achieve this aim such as PG, a dihydric alcohol 28, which has bactericidal activity 29, and as a vehicle has demonstrated to improve the diffusing property of drugs 30. Interestingly, chitosan has regeneration-inducting as well as antibacterial capabilities makes it a promising biomaterial with several applications on dentistry such as drug delivery vehicles 31. Also, Grapefruit-seed extract (GSE) is a natural product obtained from Citrus paradisi, grinding their seeds, pulp and white membranes mixing them with glycerin 32. This extract has shown a powerful antimicrobial activity 33 mainly attributed to the presence of polyphenolic compounds, flavonoids, citric and ascorbic acid, tocopherol and limonoid 34. Interestingly, super-oxidized solution (SOS) which is an electrochemically processed solution made from water and NaCl present antimicrobial capacity, since has been proposed to clean of root canal walls and including is able to eradicate Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) 35-37.

Several microorganisms, such as E. faecalis are present in endodontic infections, this one, has been widely studied due to its resistance to conventional endodontic treatment 38, being one of the most important bacteria on the root canal 39. E. faecalis is a gram-positive facultative anaerobe cocci bacteria that that inhabits the human oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and vagina 40. This bacteria has the capacity to invade dentinal tubules due to the presence of a collagen-binding protein (Ace) 41, and resist nutritional deprivation 42, as well as, delayed penetration of antimicrobial agents by the presence of its enterococcal surface protein (Esp), producing a biofilm of polystyrene 43. Also survive in environments of 10° to 60° of temperature, avoiding the action of lymphocytes 44, with the ability to grow in high pH ambient 45, even forming a biofilm in the presence of Ca(OH)2 solutions 46, mostly for this facility to attachment to abiotic surfaces 47 and other bacteria, serum, collagen and dentin 48. Hence the virulence factors of E. faecalis as adhesion and colonization, resistance to host defense, inhibition on other bacteria, tissue damage and induction of inflammation summarized by Kayaoglu et al. 48, emphasize on the necessity to find strategies to manage the elimination of this microorganism.

Until now, no studies have been found in the literature evaluating if the change of vehicle in this paste can modified the drug delivery and potentiate their action. For the above, the aim of this study was to evaluate if these products inhibit E. faecalis by themselves or have the capacity to potentiate the antimicrobial effect of CTZ paste.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

The evaluated vehicles were PG (Harleco, Mexico), chitosan (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), SOS (Esteripharma, México) and grapefruit-seed extract (Nutribiotic, Mexico) and as positive control and negative control were used eugenol (Viarden, Mexico) and 0.9% saline solution (S.S.) (PISA, Mexico), respectively. The CTZ (Farmacia Galenico, Mexico) was commercially obtained to avoid the variation in the formulation and the presence of excipients. The bacteria E. faecalis was donated by the Research Department of Endodontics of the Stomatology Faculty of the Autonomus University of San Luis Potosí, where was isolated from the root canal of patients with secondary endodontic infections employing a sterile paper tips, and subsequently cultivated in thioglycolate tubes that were incubated in an anaerobic chamber 49.

E. faecalis Characterization

E. faecalis was characterized by gram staining for the determination of cell morphology and to classify in gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria using an optical microscopy. Then, biochemical test with 26 substrates and antibiotic resistance of 20 drugs were determinated using the kit Microscan pos combo panel type 33 (Beckman coulter Cat. #B1017-211) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Growth Kinetic of E. faecalis

E. faecalis was cultivated in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) medium evaluating absorbance at 600 nm (Optizen pop, Mecasys, South Korea) every hour for 12 h to establish growth kinetics. Additionally, serial dilutions were made in trypto-casein soy agar plates (TSA) to evaluate colony forming units (CFU), evaluating cell viability during the growth kinetics.

Drugs Preparation

500 mg of CTZ was mixed with the vehicles, using a different amount of each to obtain a paste with a firm and adhesive consistency (

Table 1). The chitosan powder was incorporated with 0.4% of acetic acid in glycerol to obtain a hydrogel, for this was weight 1.34 g and mixed with 3 mL of saline solution to get a paste with the same consistency of the other groups.

Kirby–Bauer Disc Diffusion Method

The E. faecalis was adjusted equal to 0.5 McFarland standard by adding sterile distilled water, which corresponds to ~1.5x108 cells/mL. The bacterial suspension of 100 µL was distributed throughout to the plate with Müller Hilton agar (Becton Dickinson, USA) to place a triplicate of absorbent paper discs of 5 mm in diameter impregnated of each mixture or a triplicate of absorbent paper disc impregnated only with 5 µL of each different vehicles and as a control, discs impregnated with S.S. was employed. All plates were incubated 24 h at 37 ºC. After incubation the plates were observed and the inhibition zone was measured with a digital vernier (CALDI-6MP, Truper).

Statistical Analysis

For the analysis of the data, means and standard deviation of the inhibition zone size were used. One-way ANOVA and Tukey test were used with a significance level of p<0.05 using GraphPad prism v.8.

3. Results

E. faecalis Exhibit Resistance Behavior to Antibiotics

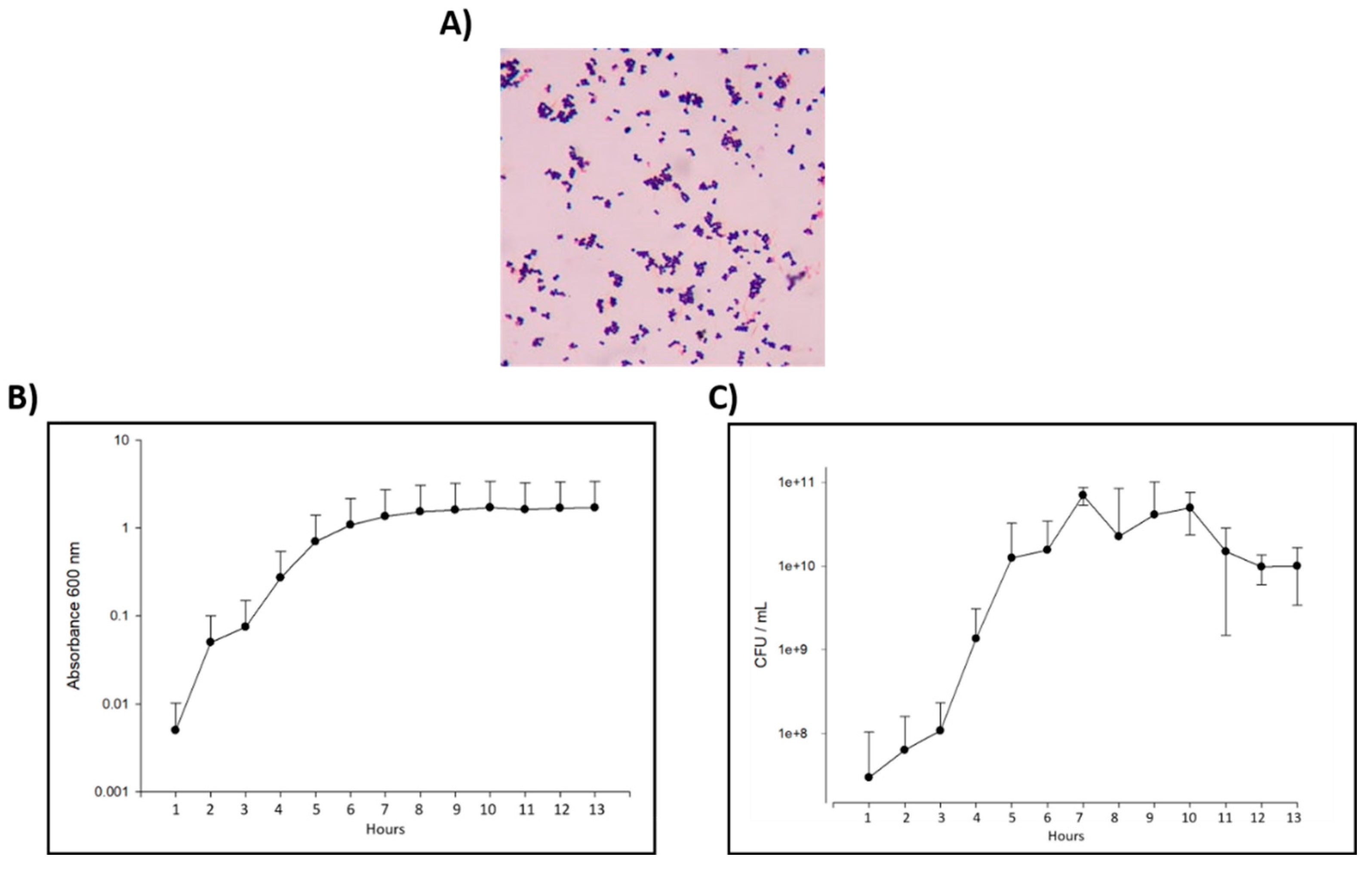

The clinical isolated of E. faecalis, showed the typical cell morphology of this bacteria as Gram-positive cocci in pairs and short chains on Gram stain (

Figure 1A). Also, the biochemical characterization showed that the clinical isolated has a 99.9% of correspondence with E. faecalis (

Table 2). Furthermore, this characterization was complemented by resistance to antibiotics analysis (

Table 3), observing that this bacterium was sensitive to Ampicillin, Ciprofloxacin, Daptomycin, Gentamicin, Penicillin, Rifampicin, and intermediate resistance to Linezolid. Interestingly, the clinical isolated was resistance to Erythromycin, Streptomycin and Tetracyclin, the latter being one of the main components of CTZ paste, highlighting the importance to improving the antimicrobial effect of CTZ paste.

E. faecalis Has a Conventional Pattern of Growth

The results of the bacterial calibration curve using OD showed that E. faecalis have a lag phase duration of 3 h, the logarithmic growth starts at hour 3 and continue for 6 more hours when the bacteria entrance in to the stationary phase (

Figure 1B). Viability evaluation was perform counting the CFU each hour in a period of 13 h, observing that the growth peak for E. faecalis starts at hour 4 (

Figure 1C), so at this time the bacteria was take it to carry out the antibiogram test with the CTZ paste mixed with different vehicles.

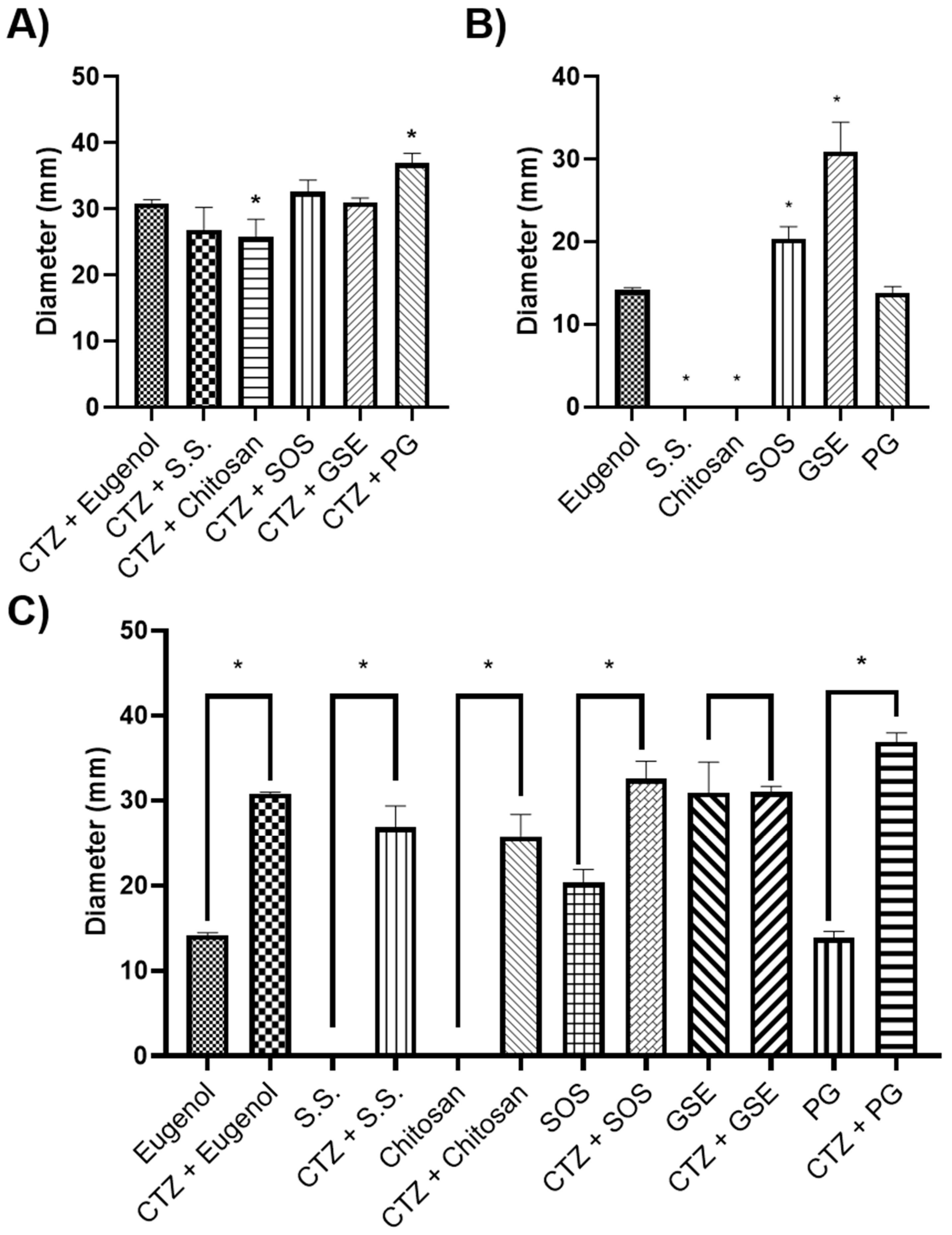

PG Potentiates CTZ Paste Effect on E. faecalis

The results of the bacterial growth inhibition by CTZ paste mixed with different vehicles after 24 h showed that the bacterial growth of the paste it was not potentiated when was mixed with SOS (32.6±2.0 mm, p= 0.2000) and GSE (26.8±2.5 mm, p= 0.9891), showing no significant difference to positive control Eugenol (30.8±0.1), however, PG did show greater inhibition of bacterial growth (36.9±1.0 mm, p= 0.0021) compared to the positive control (Figure 3A). Interestingly, no significant difference was found when eugenol was compared to negative control S.S. (26.8±2.5 mm, p= 0.1542), meaning that this vehicle no promotes a real antibacterial capacity of the CTZ paste.

GSE Has a Potential Antibacterial Effect Used Alone

To evaluated if the vehicles used to enhance the effect of the CTZ have antimicrobial capacity when is used alone, Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method was employed finding that S.S and Chitosan have a null antibacterial effect, however, PG (13.8±0.8, p= 0.9987) has a similar effect of Eugenol on E. faecalis (14.2±0.3), and interestingly a major inhibition was found by SOS (20.3±1.5, p= 0.0023) and GSE (30.9±3.6, p< 0.0001), been the last one the vehicle with the highest antibacterial effect (Figure 3B), proposing GSE as a solution that could be used alone as an irrigant.

4. Discussion

It has been reported that the presence of E. faecalis is similar in temporary and permanent teeth 50, so it is important to look for alternatives that allow the clinician to eliminate this microorganism. Currently, the use of a mixture of broad spectrum antibiotics has been introduced as a treatment for pulp therapy called CTZ paste 51, which have shown in vitro capacity to eliminate E. faecalis with the use of eugenol as a vehicle 15, 52-53, however, it has been reported that the change in the vehicle can improve the diffusion and release of this drugs 54, thus this study aimed to assess if the change of vehicle for CTZ paste improves the inhibition of E. faecalis in vitro.

Isolated strain in this study was examined in terms of antimicrobial susceptibility by a wide range of antibiotics and showed resistance to a large number of them such as Erythromycin, Streptomycin and Tetracyclin, however some of them being effective against E. faecalis such as to Ampicillin, Ciprofloxacin, Daptomycin, Gentamicin, Penicillin, Rifampicin. The above result differ to Pazhouhnia et al. 55, since they reported a different pattern of antibiotics resistance in several E. faecalis isolated strains from root canal of individuals with periodontitis, interestingly, agreeing that both the strains isolated by them and our clinical isolate of E. faecalis are resistant to tetracycline, one of the main components of CTZ paste. This highlights the variability in pathogenicity that can be found in different clinical isolates.

The bactericidal capacity of eugenol is due its ability to cause hydrophobicity, this alters the cell membrane making it more permeable 20, which leads to the extreme loss of molecules and ions and finally the cell death 56. Despite of this, in our results eugenol shows a medium inhibition alone and mixed with CTZ compare with the rest of the vehicles. The above results match with De Sales Reis et al. 53, who reported a similar inhibition to us of E. faecalis with CTZ paste mixed with eugenol. In the case of de Oliveira et al.15, they reported a major inhibition of E. faecalis, however they employed a clinical isolated as we mentioned above, different isolates may differ in their pathogenicity.

Currently, chitosan is one of the most important drug delivery system 57. Additionally, it has been reported that drug-free chitosan has antimicrobial activity against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria 58, including against E. faecalis 59, however, despite of the above reports, in our results we did not find any effect of chitosan used alone or as a vehicle for CTZ paste. We consider that this result was related with our high chitosan concentration since the dense consistency did not allow the release of the active principle.

Propylene glycol (1,2-propanediol), a dihydric alcohol 28, is a vehicle that has demonstrated to improve the diffusing property of drugs 30, which also have bactericidal activity 29. In our results, this vehicle showed similar inhibition to eugenol against E. faecalis used alone, which differs from what was reported by Thomas et al. 60, who found that eugenol presented antibacterial properties against E. faecalis, meanwhile, PG did not, which coincides with other authors 61. Conversely, other studies showed a bactericidal effect of 25 % against E. faecalis 29. As vehicle, PG mixed with endodontic medicament has shown antimicrobial activity against several bacteria including E. faecalis in vitro 54. Also, Pereira et al. evaluated this vehicle with tri-antibiotic pastes (TAP) against an ATCC of E. faecalis in vitro showing intratubular decontamination 61. In our study, when this vehicle was mixed with CTZ achieved the highest halo of inhibition compared to the rest of the vehicles, this could be related with the hygroscopic nature and viscosity of PG which allow the sustained release of ions increasing the antibacterial properties of the drugs 62. Our results showed that this vehicle allow the optimal release of the active principles.

In addition, super-oxidized solutions have been shown to be potent antimicrobial agents and disinfectants through oxidative damage 63, since electrolyzed water contains a mixture of inorganic oxidants, such as hypochlorous acid (HClO), hypochlorous acidic ion (ClO-), chlorine (Cl2), hydroxide (OH), and ozone (O3). Controversial results have been described to SOS antimicrobial capacity, since it may or may not be effective in eliminating E. faecalis from the root canal compared to NaOCl 36-37. Despite the above, our result showed that SOS may have an intermediate antibacterial effect against our clinical isolated of E. faecalis used alone, however, its properties as a vehicle are not remarkable compared to the other materials evaluated.

Grapefruit seed extract is a natural product obtained from Citrus paradisi, grinding their seeds, pulp and white membranes mixing them with glycerine 64. This extract has shown a powerful antimicrobial activity 65 mainly attributed to the presence of polyphenolic compounds, flavonoids, citric and ascorbic acid, tocopherol and limonoid34. This capacity has been evaluated against an ATCC reference strains of E. faecalis, showing from low 65 to high 66 antibacterial effect against this bacterium. In our study with E. faecalis clinical isolated, a great inhibition was observed, this could be related with the grapefruit seed extract concentration since in the previous studies were performed at concentration of 33%, meanwhile we employed a higher concentration of 46%. Although this extract by itself obtained the highest inhibition zone compared with the rest of the vehicles, the result was not the same when was mixed with CTZ showing a similar inhibition to eugenol, which is the recommend vehicle. Until now, no studies have evaluated this extract as a vehicle for CTZ, we observed that does not improve their antimicrobial activity, we consider that is not the ideal vehicle for the application of these antibiotics, although, could be used alone as irrigation solution, since it has demonstrated antimicrobial activity against bacteria gram negative and positive and yeast 65. It is very interesting since it could be used in primary and permanent endodontic procedures that includes periodontal tissues without side effects. Another putative advantage of this natural product, is that the bacteria does not show resistance to this product since it is a new substance, being the resistance an important persistent complication in endodontic treatment., and which have become in a global issue 13. Therefore, it is promissory to use it as a single solution against E. faecalis and other bacterial strains present in the oral microbiome associated with active dental infections. However, further experiments need to be performed inside the root canal.

Green technology extracts could be an excellent option against the oral microbiome associated with active dental infections. Furthermore, it is an excellent option to use plant or fruit extracts to clean the root canal system from the irrigation phase; currently the use of blueberry and wild strawberry extracts 67 and enzymes from the peel of papaya orange and pineapple 68, has been proposed as an alternative to sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), to avoid cause severe injuries that might occur with NaOCl accidents or in allergic patients 69, showing promising results in an in vitro study versus E. faecalis.

The effectiveness of GSE in the inhibition of biofilms by Porphyromonas endodontalis and Porphyromonas gingivalis it has been evaluated in vitro showing a promising antibiofilm activity, also a cytotoxicity assay with human gingival fibroblast was carried out observing high biocompatibility; missing characteristic in NaOCl, that can cause from a burning sensation in gingiva to periapical tissue necrosis 70.

5. Conclusions

The vehicle used to mix the CTZ paste plays an important role in the effect of inhibition against E. faecalis in vitro, although this is not the only bacteria that the clinician faces during pulp therapy, is one of the most resistant, therefore its eradication is extremely important. Our results showed that PG could be the best vehicle for the CTZ paste. Henceforth, it is necessary to evaluate if PG mixed with CTZ maintain a highest inhibition that eugenol against other microorganism related with pulpal pathologies.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, AFM, SSJE and SBEL; methodology, RVJY and RCF; software, RVJY and AFM; validation, ZANV and LRJP; formal analysis, RVJY and RCF; investigation, RVJY, RCF, AFM, SSJE and SBEL; resources, RQJG and CSGY; writing—original draft preparation, RVJY, RCF, CSGY, RAM, RQJG, LRJP, ZANV, AFM, SSJE and SBEL; writing—review and editing, RVJY, RCF, CSGY, RAM, RQJG, LRJP, ZANV, AFM, SSJE and SBEL; funding acquisition, CSGY, RQJG, RAM and SBEL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Distribuidora de Productos y Materias Primas Alimenticias Hidalgo S. A. de C. V. for the donation of the grapefruit-seed extract used in this work. We also thank to PhD. Elsa Maribel Aguilar Medina for giving us access to the Microbiology Laboratory under her responsibility at the Faculty of Biological Chemical Sciences to carry out this research.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”.

References

- Kazeminia, M.; Abdi, A.; Shohaimi, S.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Salari, N.; Mohammadi, M. Dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children's worldwide, 1995 to 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Face Med. 2020, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagramian, R.A.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Volpe, A.R. The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis. Am. J. Dent. 2009, 22, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. Sugars and Dental Caries; 2017.

- Reddy, S.; Ramakrishna, Y. Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of various root canal filling materials used in primary teeth: A microbiological study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2007, 31, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Sainz, J.E.; Alarcón-Romero, P.; Gastélum-Rosales, G.; Castro-Salazar, Y.; Ramos-Payán, R.; Romero-Quintana, G.; Aguilar-Medina, M. Presence of red complex bacteria and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in necrotic primary teeth with periapical abscess in children of Sinaloa, México. Rev. Biomédica 2020, 31, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchene, F.; Masmoudi, F.; Baaziz, A.; Maatouk, F.; Ghedira, H. Antibiotic Mixtures in Noninstrumental Endodontic Treatment of Primary Teeth with Necrotic Pulps: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 5518599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, R.; Koul, M.; Srivastava, S.; Upadhyay, V.; Dwivedi, R. Clinical evaluation of 3 Mix and Other Mix in non-instrumental endodontic treatment of necrosed primary teeth. J. Oral. Biol. Craniofac Res. 2014, 4, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo-Fereira, J.; Ayala-Jimenez, S.; Carlos-Medrano, L.E.; Toscano-Garcia, I.; Anaya-Alvarez, M. Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation of Formocresol and Chloramphenicol, Tetracycline and Zinc Oxide-Eugenol Antibiotic Paste in Primary Teeth Pulpotomies: 24 month follow up. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2019, 43, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Meng, M.; Law, C.S.; Rao, Y.; Zhou, X. Common dental diseases in children and malocclusion. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 2018, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujel, N.; Duggal, M.S.; Saini, P.; Day, P.F. The effect of premature extraction of primary teeth on the subsequent need for orthodontic treatment. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2016, 17, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raslan, N.; Mansour, O.; Assfoura, L. Evaluation of antibiotic mix in Non-instrumentation Endodontic Treatment of necrotic primary molars. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sain, S.; George, S. Lesion Sterilization and Tissue Repair-Current Concepts and Practices. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 11, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Albarrán, C.A.; Morales-Dorantes, V.; Ayala-Herrera, J.L.; Castillo-Aguillón, M.; Soto-Barreras, U.; Cabeza-Cabrera, C.V.; Domínguez-Pérez, R.A. Antibiotic Resistance Decreases the Efficacy of Endodontic Filling Pastes for Root Canal Treatment in Children's Teeth. Children 2021, 8, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappiello, J. Tratamientos pulpares en incisivos primarios. Rev. Asoc. Odontol. Argent. 1964, 52, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, S.C.M.; de Omena, A.L.C.S.; de Lucena Lira, G.A.; Ferreira, I.A.; Imparato, J.C.P.; Calvo, A.F.B. Do Different Proportions of Antibiotics in the CTZ Paste Interfere with the Antimicrobial Action? In Vitro Study. Pesqui. Bras. Em Odontopediatria E Clínica Integr. 2019, 19, 4801–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Borges, M.; Thong, B.; Blanca, M.; Ensina, L.F.; Gonzalez-Diaz, S.; Greenberger, P.A.; Jares, E.; Jee, Y.K.; Kase-Tanno, L.; Khan, D.; et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to non beta-lactam antimicrobial agents, a statement of the WAO special committee on drug allergy. World Allergy Organ. J. 2013, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.M.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Faveri, M.; Cortelli, S.C.; Duarte, P.M.; Feres, M. Mechanisms of action of systemic antibiotics used in periodontal treatment and mechanisms of bacterial resistance to these drugs. J. Appl. Oral. Sci. 2012, 20, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seil, J.T.; Webster, T.J. Antimicrobial applications of nanotechnology: Methods and literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 2767–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini Priya, M.; Bhat, S.S.; Sundeep Hegde, K. Comparative evaluation of bactericidal potential of four root canal filling materials against microflora of infected non-vital primary teeth. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2010, 35, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaidka, S.; Somani, R.; Singh, D.J.; Sheikh, T.; Chaudhary, N.; Basheer, A. Herbal combat against E. faecalis - An in vitro study. J. Oral. Biol. Craniofac Res. 2017, 7, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrah, A.H.A.; Yassen, G.H.; Liu, W.-C.; Goebel, W.S.; Gregory, R.L.; Platt, J.A. The effect of diluted triple and double antibiotic pastes on dental pulp stem cells and established Enterococcus faecalis biofilm. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2015, 19, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, H.; Abu-Seida, A.M.; Hashem, A.A.; Nagy, M.M. Regenerative potential following revascularization of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulps. Int. Endod. J. 2013, 46, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardo, M.R.; Bezerra da Silva, L.A.; Leonardo, R.; Utrilla, L.S.; Assed, S. Histological evaluation of therapy using a calcium hydroxide dressing for teeth with incompletely formed apices and periapical lesions. J. Endod. 1993, 19, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson Filho, P.; Silva, L.A.; Leonardo, M.R.; Utrilla, L.S.; Figueiredo, F. Connective tissue responses to calcium hydroxide-based root canal medicaments. Int. Endod. J. 1999, 32, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, M.A.H.; Alves de Aguiar, K.; Zeferino, M.A.; Vivan, R.R.; Ordinola-Zapata, R.; Tanomaru-Filho, M.; Weckwerth, P.H.; Kuga, M.C. Evaluation of the propylene glycol association on some physical and chemical properties of mineral trioxide aggregate. Int. Endod. J. 2012, 45, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, G.; Rodrigues, E.M.; Coaguila-Llerena, H.; Gomes-Cornelio, A.L.; Neto Angeloco, R.R.; Swerts Pereira, M.S.; Tanomaru Filho, M. Influence of the Vehicle and Antibiotic Formulation on Cytotoxicity of Triple Antibiotic Paste. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.S.; Margasahayam, S.V.; Shenoy, V.U. A Comparative Evaluation of the Influence of Three Different Vehicles on the Antimicrobial Efficacy of Triple Antibiotic Paste against Enterococcus faecalis: An In vitro Study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2020, 11, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, E.V.; Kota, K.; Huque, J.; Iwaku, M.; Hoshino, E. Penetration of propylene glycol into dentine. Int. Endod. J. 2002, 35, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalawade, T.M.; Bhat, K.; Sogi, S.H. Bactericidal activity of propylene glycol, glycerine, polyethylene glycol 400, and polyethylene glycol 1000 against selected microorganisms. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, E.G.; Parolia, A.; Ahlawat, P.; Pau, A.; Amalraj, F.D. Antifungal effectiveness of various intracanal medicaments against Candida albicans: An ex-vivo study. BMC Oral. Health 2014, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckiewicz, M.; W Boening, K.; Grychowska, N.; Paradowska-Stolarz, A. Clinical application of chitosan in dental specialities. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Ficelo, S.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Bioactivity of Grapefruit Seed Extract against Pseudomonas SPP. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2010, 34, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetnić, Z.; Vladimir-Knezević, S. Antimicrobial activity of grapefruit seed and pulp ethanolic extract. Acta Pharm. 2004, 54, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanmani, P.; Rhim, J.W. Antimicrobial and physical-mechanical properties of agar-based films incorporated with grapefruit seed extract. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 102, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tour Savadkouhi, S.; Mohtasham Maram, M.; Purhaji Bagher, M.; Afkar, M.; Fazlyab, M. In Vitro Activity of Superoxide Water on Viability of Enterococcus faecalis Biofilm on Root Canal Wall. Iran. Endod. J. 2021, 16, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi-Fedele, G.; Figueiredo, J.A.; Steier, L.; Canullo, L.; Steier, G.; Roberts, A.P. Evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of super-oxidized water (Sterilox®) and sodium hypochlorite against Enterococcus faecalis in a bovine root canal model. J. Appl. Oral. Sci. 2010, 18, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, R.; Alacam, T.; Hubbezoglu, I.; Tunc, T.; Sumer, Z.; Alici, O. Antibacterial Efficacy of Super-Oxidized Water on Enterococcus faecalis Biofilms in Root Canal. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2016, 9, e30000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basmaci, F.; Oztan, M.D.; Kiyan, M. Ex vivo evaluation of various instrumentation techniques and irrigants in reducing E. faecalis within root canals. Int. Endod. J. 2013, 46, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnaashari, M.; Eghbal, M.J.; Sahba Yaghmayi, A.; Shokri, M.; Azari-Marhabi, S. Comparison of Antibacterial Effects of Photodynamic Therapy, Modified Triple Antibiotic Paste and Calcium Hydroxide on Root Canals Infected With Enterococcus faecalis: An In Vitro Study. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 10 (Suppl 1), S23–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, F.; Shakir, M. The Influence of Enterococcus faecalis as a Dental Root Canal Pathogen on Endodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Du, J.; Peng, Z. Correlation between Enterococcus faecalis and Persistent Intraradicular Infection Compared with Primary Intraradicular Infection: A Systematic Review. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, C.H.; Schwartz, S.A.; Beeson, T.J.; Owatz, C.B. Enterococcus faecalis: Its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J. Endod. 2006, 32, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiniforush, N.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Parker, S.; Benedicenti, S.; Shahabi, S.; Bahador, A. The effect of sublethal photodynamic therapy on the expression of Enterococcal surface protein (esp) encoding gene in Enterococcus faecalis: Quantitative real-time PCR assessment. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 24, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, I.; Micó-Muñoz, P.; Giner-Lluesma, T.; Micó-Martínez, P.; Collado-Castellano, N.; Manzano-Saiz, A. Influence of microbiology on endodontic failure. Literature review. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Y Cir. Bucal 2019, 24, e364–e372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.; Davies, J.K.; Sundqvist, G.; Figdor, D. Mechanisms Involved In The Resistance Of Enterococcus Faecalis To Calcium Hydroxide. Aust. Endod. J. 2001, 27, 115–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhajharia, K.; Parolia, A.; Shetty, K.V.; Mehta, L.K. Biofilm in endodontics: A review. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Arana, A.; Valle, J.; Solano, C.; Arrizubieta, M.J.; Cucarella, C.; Lamata, M.; Amorena, B.; Leiva, J.; Penadés, J.R.; Lasa, I. The enterococcal surface protein, Esp, is involved in Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 4538–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaoglu, G.; Ørstavik, D. Virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis: Relationship to endodontic disease. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Oral. Biol. 2004, 15, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Pacheco, J.; Vitales-Noyola, M.; González-Amaro, A.M.; Bujanda-Wong, H.; Aragón-Piña, A.; Méndez-González, V.; Pozos-Guillén, A. Evaluation of in vitro biofilm elimination of Enterococcus faecalis using a continuous ultrasonic irrigation device. J. Oral. Sci. 2020, 62, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogulu, D.; Uzel, A.; Oncag, O.; Aksoy, S.C.; Eronat, C. Detection of Enterococcus faecalis in Necrotic Teeth Root Canals by Culture and Polymerase Chain Reaction Methods. Eur. J. Dent. 2007, 1, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokade, A.; Thakur, S.; Singhal, P.; Chauhan, D.; Jayam, C. Comparative evaluation of clinical and radiographic success of three different lesion sterilization and tissue repair techniques as treatment options in primary molars requiring pulpectomy: An in vivo study. J. Indian. Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2019, 37, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piva, F.; Italo, F.; Estrela, C. Antimicrobial activity of different root canal filling pastes used in deciduous teeth. J. Mat. Res. 2008, 11, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sales Reis, B.; Barbosa, C.C.N.; de Castro Soares, L.; Brum, S.C.; Cecilio, O.L.; Marques, M. Análise “in vitro” da atividade antimicrobiana da pasta ctz utilizada como material obturador na terapia pulpar de dentes decíduos. Rev. Prouniversus 2016, 7, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nalawade, T.M.; Bhat, K.G.; Sogi, S. Antimicrobial Activity of Endodontic Medicaments and Vehicles using Agar Well Diffusion Method on Facultative and Obligate Anaerobes. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2016, 9, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazhouhnia, S.; Bouzari, M.; Arbabzadeh-Zavareh, F. Isolation, characterization and complete genome analysis of a novel bacteriophage vB_EfaS-SRH2 against Enterococcus faecalis isolated from periodontitis patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantry, B.A.; Kumar, A.; Rahiman, S.; Tantry, M.N. Antibacterial evaluation and phytochemical screening of methanolic extract of Ocimum sanctum against some common microbial pathogens. Glob. Adv. Res. J. Microbiol. 2016, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, N.; Rana, D.; Salave, S.; Gupta, R.; Patel, P.; Karunakaran, B.; Sharma, A.; Giri, J.; Benival, D.; Kommineni, N. Chitosan: A Potential Biopolymer in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chi, Y.-Q.; Yu, C.-H.; Xie, Y.; Xia, M.-Y.; Zhang, C.-L.; Han, X.; Peng, Q. Drug-free and non-crosslinked chitosan scaffolds with efficient antibacterial activity against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 241, 116386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ji, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, X.; Mei, L.; Zhang, H.; Deng, J.; Wang, S. Antibacterial effect of chitosan and its derivative on Enterococcus faecalis associated with endodontic infection. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 3805–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, P.A.; Bhat, K.S.; Kotian, K.M. Antibacterial properties of dilute formocresol and eugenol and propylene glycol. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. 1980, 49, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.C.; Vasconcelos, L.R.; Graeff, M.S.; Duarte, M.A.; Bramante, C.M.; Andrade, F.B. Intratubular disinfection with tri-antibiotic and calcium hydroxide pastes. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2017, 75, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, S.; Jibhkate, N.; Baranwal, R.; Avinash, A.; Rathi, S. Propylene glycol: A new alternative for an intracanal medicament. J. Int. Oral. Health 2016, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-R.; Hung, Y.-C.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Huang, Y.-W.; Hwang, D.-F. Application of electrolyzed water in the food industry. Food Control 2008, 19, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Ficelo, S.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Bioactivity of grapefruit seed extract against Pseudomonas spp. J. Food Process Pres. 2010, 34, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetnic, Z.; Vladimir-Knezevic, S. Antimicrobial activity of grapefruit seed and pulp ethanolic extract. Acta Pharm. 2004, 54, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reagor, L.; Gusman, J.; McCoy, L.; Carino, E.; Heggers, J.P. The effectiveness of processed grapefruit-seed extract as an antibacterial agent: I. An in vitro agar assay. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2002, 8, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, A.; Razavi, S.A.; Mosaddeghmehrjardi, M.H.; Tabrizizadeh, M. The Effect of Fragaria vesca Extract on Smear Layer Removal: A Scanning Electron Microscopic Evaluation. Iran. Endod. J. 2015, 10, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavani, H.A.K.; Tew, I.M.; Wong, L.; Yew, H.Z.; Mahyuddin, A.; Ahmad Ghazali, R.; Pow, E.H.N. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Fruit Peels Eco-Enzyme against Enterococcus Faecalis: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ajitha, P.; Raghu, S. Muralidaran, Comparative evaluation of antimicrobial activity of 3% sodium hypochlorite, 2% chlorhexidine, and 5% grape seed extract against Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans - An in vitro study. Drug Invent. Today 2019, 12, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nurani Hayati, A.S.W.; Roeslan, B.O. Effectiveness of Grapefruit (Citrus Paradisi) And Lime (Citrus Aurantifolia) Against Pathogenic Root Canal Biofilms. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 12, 3494–3502. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).