4. Discussion

According to the literature data there are differences in the hatchability of the eggs between the young and old parent flocks [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In the study of Roque et al. [

21,

21] hatchability and viability (hatchability of fertile eggs) were lower in the younger, 27–31-week-old flock due to the increased early and late embryonic mortalities. This is consistent with those can be found in the breeders’ management manual [

14]. In our case the fertility and the embryonic death rate was not worse in the younger flock and the hatchability was even higher. Similarly, to our results Abudabos et al. [

22] found higher mid-term dead embryos from older hens. Egg storage before hatching could also be a factor, which depresses egg albumen Haugh units (HU) and chick quality [

20]. This effect is greater in old, 45-week-old breeding hens. Of course, these results are affected by several environmental and nutritional factors, also including the exact age of the flocks.

It is also well known that the breeder’s age influences the weight of the egg and the day-old chicken [

7,

8,

23] and this body weight effect can be persisting until slaughter [

24]. Our experiment proves these results and confirms, that broiler chickens have limited compensatory potential due to their almost continues feed intake and the short fattening period.

After the chick hatches and the remaining yolk complex is withdrawn into the abdominal cavity, the lipid assimilation and metabolism of the yolk continues and is sufficient to adequately maintain the chick for several days after hatching [

9]. The time of hatching resulted in our trial significantly higher hatching weight for birds hatched later. The reason behind this may be the weight loss of “early” hatched chicks and the greater depletion of their glycogen stores [

25]. In addition, the late hatched chickens are more mature in development at hatch [

5]. There are plenty results available on the effects of feed and water deprivation on the metabolism and viability of young broiler chickens [

26,

27,

28] The novelty of our result is that no artificial deprivations were used, but only the effects of the hatching window during a normal hatchery practice were measured. Similarly, to the parent flock age effect, the hatching time also affected the final body weight of the animals which was significant, 122 g higher final body weight in this trial. Beside the higher growth potential of the late hatched chickens, the higher variance in the day-old weight results also increase the live weight variance of the flocks later, that impairs feed conversion.

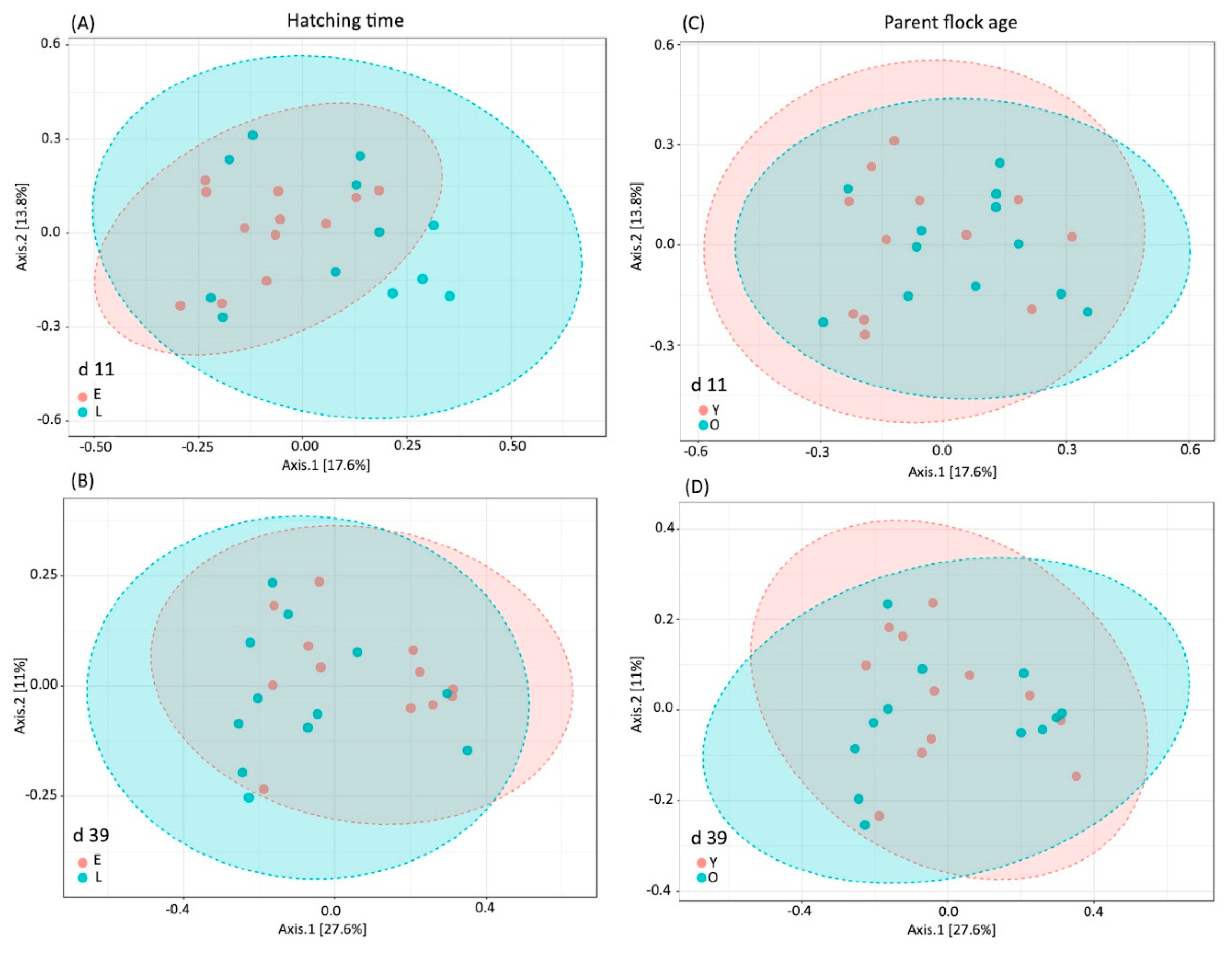

Our aim was also to find out if the different parent flocks or the hatching time of the chickens can modify the early development of the cecal microbiota. The potential impact of the parent flocks could be either the different eggshell structure or the differences in the environmental and farm conditions and this way the vertical microbiota transfer from the hens to the egg [

29,

30].

We could not find significant differences in the diversity indices and microbiota composition between the chickens of the two parent flocks at any time interval. Since the diets of the two flocks were identical, it means, that the bacteriota transfer via the eggs is determined mainly by genetic factors or the feed. The effects of the other farm conditions are low, probably since the bacteria cannot get through the eggshell and most of the bacteria are killed during the disinfection in the hatcheries [

31].

On the other hand, hatching time caused several significant changes in the cecal bacteriota in this trial. The time interval between hatch and first feeding affects the development and function of intestinal tract [

32]. The development of the intestinal tract consists of the increase of the total length and weight of the intestine, as well as the length and area of the intestinal villi [

4]. The immune and thermoregulatory system of poultry, undergo significant physiological changes too. The lipids of egg yolk are the primarily source of energy during the early post hatch period [

33,

34]. Several factors influence the residual yolk weight at hatch, especially egg size and incubation temperature, while the breeder hens’ age affects the nutrient composition of the residual yolk [

34]. The transport from the yolk sac into the intestine was observed up to 72 h after hatching [

35]. In addition, it was also described that the yolk utilisation was more rapid in fed than in fasted birds suggesting that the transport of yolk through the intestine could be increased by the greater intestinal activity found in fed chicks. It is known that in the first days after hatching the deprivation of feed slows down the gut development, as reflected by lower gut weight, shorter length, lower enzyme activity, altered villi and crypt cell density, and lower crypt depth and height in the short and long term [

5].

In mammals, it has been proven that microbes exist in different regions of the placenta and that microbial DNA can be transferred horizontally from mother to foetus through the placenta [

30,

36]. In addition, however, the structure and succession of the gut microbiota is influenced by many factors, such as the method of delivery, the birth environment, and dietary habits [

37,

38]. In the case of birds, the eggshell forms a barrier to microbial transfer to the embryo, but also provides an important protection against environmental pathogens [

39]. In hatcheries, the newly hatched chicks have only limited contact with the hen’s microbiota [

2]. This is mainly restricted to the transfer of microbes to their offspring during the egg formation process [

40]. This is important, because the host’s microbes can prevent the infections, increase hatchability and can be beneficial in the early bacteriota development [

41,

42].

Several studies reported that the delay in access to feed may affect the microbiota development. A huge increase in microorganisms occurs in the chicken’s intestine after the first ingestion of feed [

31,

43,

44]. According to our results the early hatched birds which were longer without feed, had more diverse caecal microbiota than the late hatched birds. The reason for this difference is not known. One explanation could be, that the early hatched chickens had more contacts with eggs in the brooder baskets and can be colonized with some spore forming bacteria that survive the disinfection in the hatchery. Disinfection reduces the bacterial load on eggshell surface from more than 10

4 cfu to about 10

3 cfu [

45]. On the eggs, the dominating phyla are Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Tenericutes. After the fumigation process in the hatchery the ratio of Firmicutes decrease, that of Actinobacteria increase and as new phyla, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Cyanobacteria are present [

45]. Disinfection results more divers egg surface bacteriota composition on lower taxonomic levels. We could not prove this hypothesis, since no changes in the spore-forming bacterial groups have been found due to the differences in the hatching time. Usually, early feed access increases the bacterial diversity in the intestine [

31], but we could not find results specifically on the hatching time induced changes.

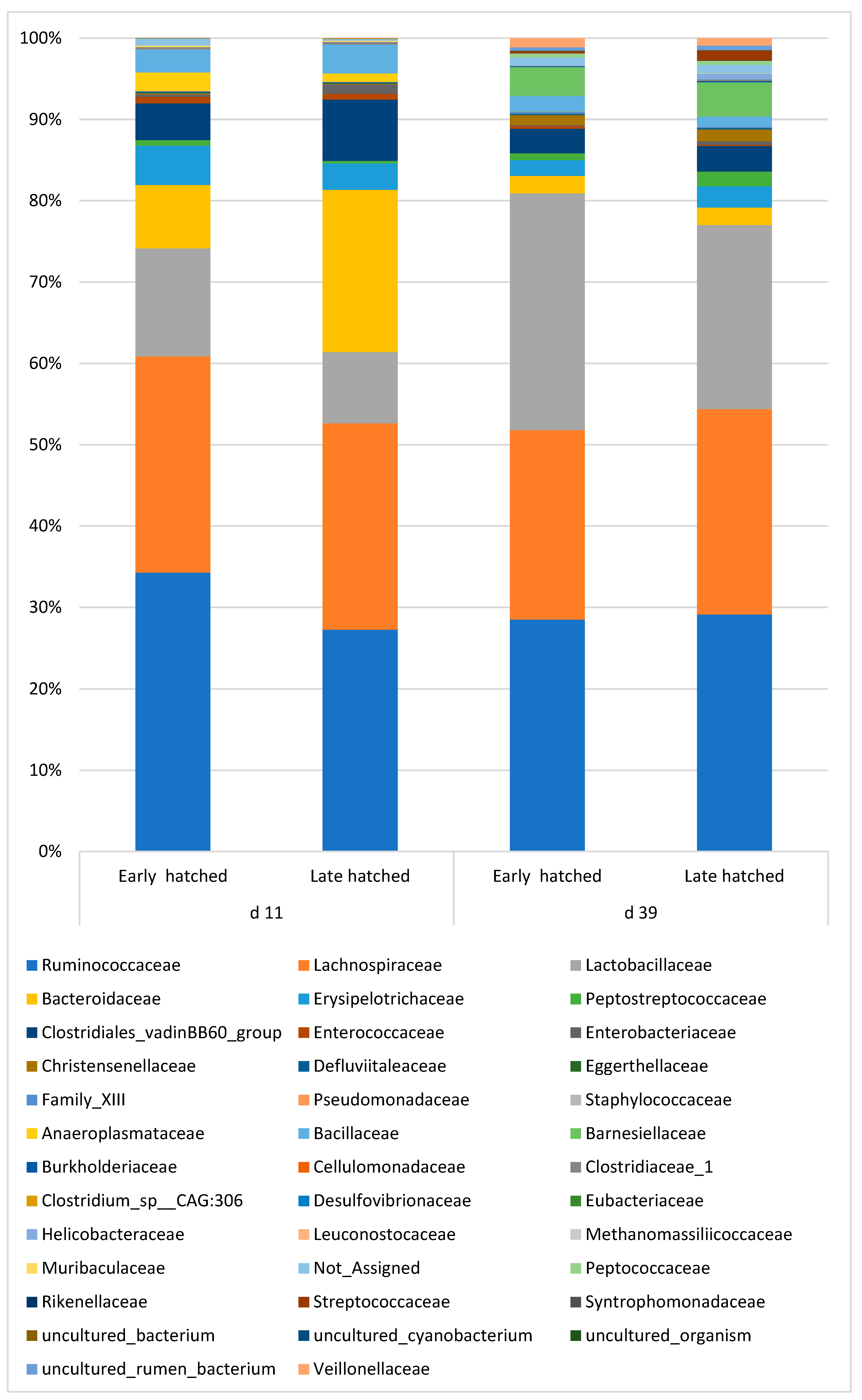

In our study, a higher abundance of

Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and lower abundance of

Firmicutes was found in the late-hatched chickens.

Actinobacteria is one of the four main phyla of the cecal microbiota, and although its abundance is low, the bacteria of this phylum playing important role in maintaining the intestinal homeostasis, since they can use a wide variety of complex polysaccharides [

46,

47]. Several studies proved the importance of the

Bacteroidetes and

Firmicutes ratio in the different gut segments [

48,

49,

50]. The frequency of the

Bacteroidetes phylum is very variable (10-57%) in birds of slaughter age. An important difference between the two phyla is that while members of

Firmicutes express fucose isomerase, members of

Bacteroidetes express xylose isomerase [

48] Members of

Bacteroidetes are present mostly in the distal intestine, where they participate in supplying the host with energy obtained from feed through the fermentation of otherwise indigestible polysaccharides [

51]. They are also important participants of the cross-feeding mechanisms, providing substrates for lactic acid producing bacteria and can provide extra energy if fibrous duets are fed [

46,

52,

53]. In addition, the secretion of antimicrobial peptides is also a characteristic feature of members of the phylum, which also supports the positive ecological function of

Bacteroidetes [

49,

54]. Furthermore, representatives of

Bacteroidetes also produce propionate, resulting in a beneficial balance between maintaining homeostasis and producing sufficient energy from available nutrients [

48]. In the case of the late-hatched birds, the higher frequency of

Bacteroidetes and

Actinobacteria phyla may be because the early-hatched animals longer only the nutrients of the yolk sac. It mostly contains mostly fats and protein, and only low amounts of carbohydrates [

27]. However, the late-hatched birds got access to digestible and indigestible carbohydrates containing feed sooner, which could promote the colonization of Bacteroidetes in the caeca. Li et al. [

55] found the opposite, when the 24- and 28-hour long feed deprivation resulted significantly higher

Bacteroidetes and

Actinobacteria abundances. However, the results are not fully comparable, because of the differences in the treatments.

In the first few days the dominance of the

Firmicutes phylum is more beneficial since many of its members are butyrate producers. The production of butyrate in the young chicken’s ceca is important because of the high demand for butyrate of the intensive growth of intestinal cells and to exclude the members of the first colonizer potential pathogens, for example

Clostridia and

Enterobacteriacea [

51,

56,

57].

Although at family level the differences between the early and late hatched chicken’s microbiota were not significant, the abundance of families

Lactobacillaceae and

Ruminococcaceae belonging to the

Firmicutes phylum decreased, while that of family

Bacteroidaceae increased in the late-hatched chickens. Members of the

Lactobacillaceae family produce lactic acid, which is the main substrate for several members of the

Ruminococcaceae family using lactate as a substrate to produce butyrate and caproic acid [

58]. Because this cross-feeding mechanism the close correlation between

Lactobacillaceae and

Ruminococcaceae is therefore not surprising. The other main butyrate producing family,

Lachnospiraceae was not influenced by the treatments. In contrast the members of the

Bacteroidaceae family to contain several genes encoding cellulose and complex polysaccharides-degrading enzymes [

54,

59,

60] and produce beside propionate and butyrate different oligosaccharides [

49,

61].