Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

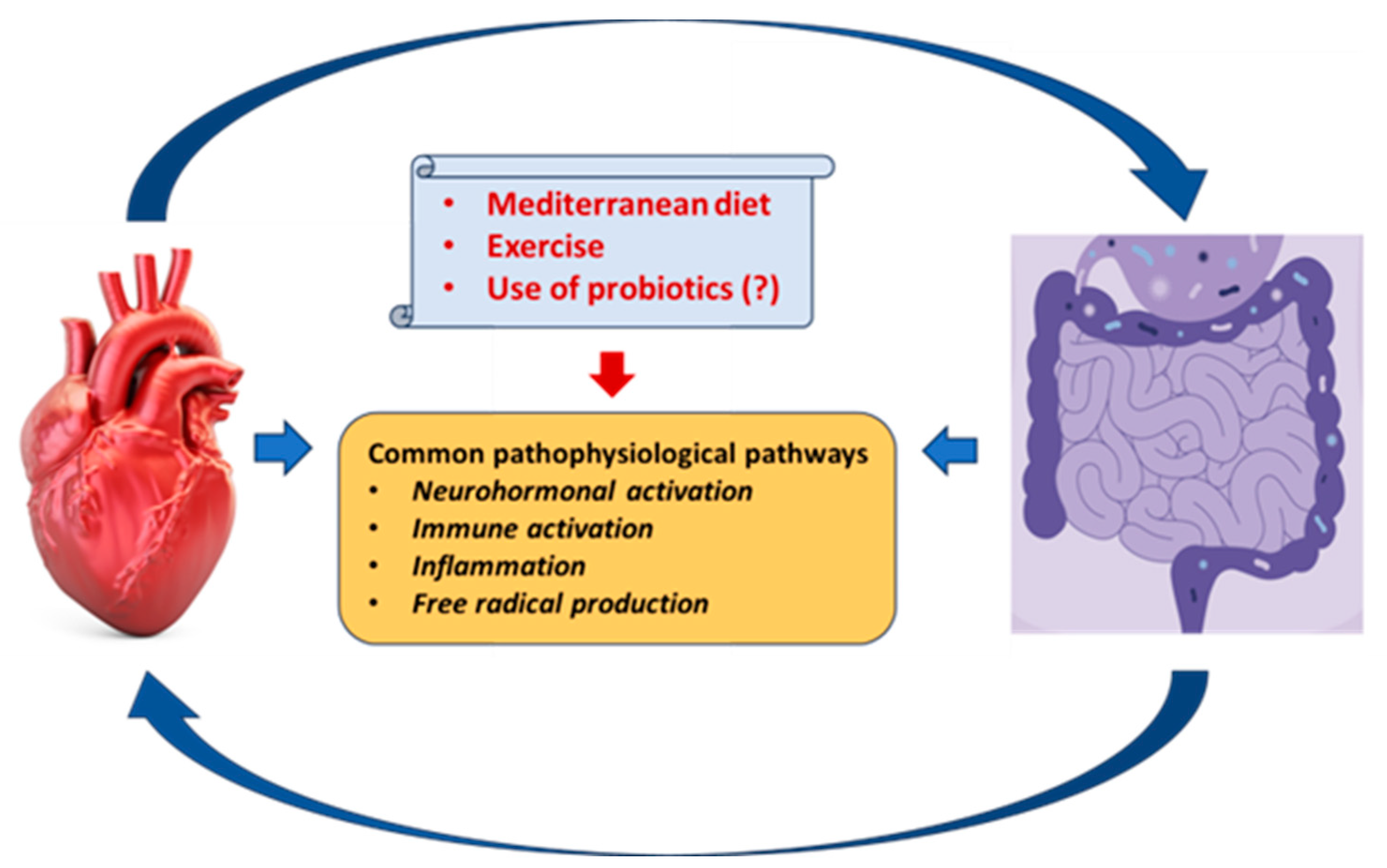

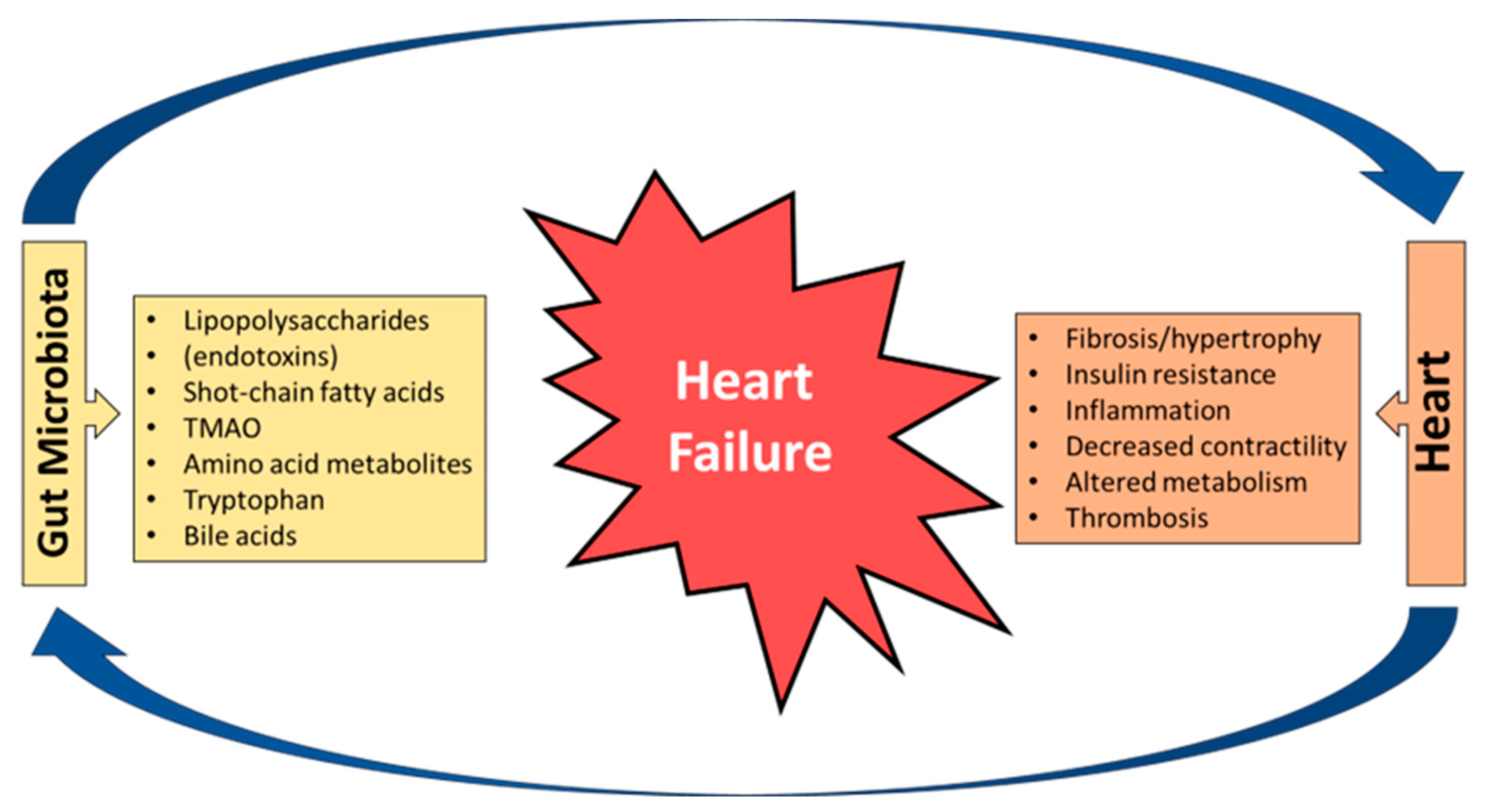

2. Bidirectional Relationship between the Heart and the Gut

3. Understanding Gut Microbiota

4. Gut Microbiota as a Diagnostic Marker

5. Gut Microbiota and Medications

6. Gut Microbiota, Aging, Diet, Exercise Training and Supplements

7. Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, Mohseni H, Hedgecott D, Crespillo AP, Allison M, Hemingway H, Cleland JG, McMurray JJV et al: Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet 2018, 391(10120):572-580.

- Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C: Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392(10159):1789-1858.

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN et al: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141(9):e139-e596.

- van Riet EE, Hoes AW, Limburg A, Landman MA, van der Hoeven H, Rutten FH: Prevalence of unrecognized heart failure in older persons with shortness of breath on exertion. Eur J Heart Fail 2014, 16(7):772-777.

- Gerber Y, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Chamberlain AM, Manemann SM, Jiang R, Killian JM, Roger VL: A contemporary appraisal of the heart failure epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med 2015, 175(6):996-1004.

- Tsao CW, Lyass A, Enserro D, Larson MG, Ho JE, Kizer JR, Gottdiener JS, Psaty BM, Vasan RS: Temporal Trends in the Incidence of and Mortality Associated With Heart Failure With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2018, 6(8):678-685.

- Savarese G, Lund LH: Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure. Card Fail Rev 2017, 3(1):7-11. 7: 3(1).

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Bohm M, Burri H, Butler J, Celutkiene J, Chioncel O et al: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021, 42(36):3599-3726.

- Paraskevaidis I, Farmakis D, Papingiotis G, Tsougos E: Inflammation and Heart Failure: Searching for the Enemy-Reaching the Entelechy. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2023, 10(1).

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr., Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM et al: 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2017, 136(6):e137-e161.

- Anker SD, Egerer KR, Volk HD, Kox WJ, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ: Elevated soluble CD14 receptors and altered cytokines in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1997, 79(10):1426-1430.

- Krack A, Sharma R, Figulla HR, Anker SD: The importance of the gastrointestinal system in the pathogenesis of heart failure. Eur Heart J 2005, 26(22):2368-2374.

- Mamic P, Snyder M, Tang WHW: Gut Microbiome-Based Management of Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81(17):1729-1739.

- Rogler G, Rosano G: The heart and the gut. Eur Heart J 2014, 35(7):426-430.

- Yu W, Jiang Y, Xu H, Zhou Y: The Interaction of Gut Microbiota and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: From Mechanism to Potential Therapies. Biomedicines 2023, 11(2).

- Witkowski M, Weeks TL, Hazen SL: Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res 2020, 127(4):553-570.

- Li Y, Yang S, Jin X, Li D, Lu J, Wang X, Wu M: Mitochondria as novel mediators linking gut microbiota to atherosclerosis that is ameliorated by herbal medicine: A review. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14:1082817.

- Gregory JC, Buffa JA, Org E, Wang Z, Levison BS, Zhu W, Wagner MA, Bennett BJ, Li L, DiDonato JA et al: Transmission of atherosclerosis susceptibility with gut microbial transplantation. J Biol Chem 2015, 290(9):5647-5660.

- Lian WS, Wang FS, Chen YS, Tsai MH, Chao HR, Jahr H, Wu RW, Ko JY: Gut Microbiota Ecosystem Governance of Host Inflammation, Mitochondrial Respiration and Skeletal Homeostasis. Biomedicines 2022, 10(4).

- Vezza T, Abad-Jimenez Z, Marti-Cabrera M, Rocha M, Victor VM: Microbiota-Mitochondria Inter-Talk: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9(9).

- Le Roy T, Moens de Hase E, Van Hul M, Paquot A, Pelicaen R, Regnier M, Depommier C, Druart C, Everard A, Maiter D et al: Dysosmobacter welbionis is a newly isolated human commensal bacterium preventing diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders in mice. Gut 2022, 71(3):534-543.

- Barrington WT, Lusis AJ: Atherosclerosis: Association between the gut microbiome and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017, 14(12):699-700.

- Jonsson AL, Backhed F: Role of gut microbiota in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017, 14(2):79-87.

- Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Clancy TE, Chung DC, Lochhead P, Hold GL et al: Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14(2):207-215.

- Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Mao H, Ma Z, Yin Y, Wang W, Tang W, Tan Z, Shi J et al: Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun 2015, 48:186-194.

- Zheng P, Zeng B, Zhou C, Liu M, Fang Z, Xu X, Zeng L, Chen J, Fan S, Du X et al: Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host's metabolism. Mol Psychiatry 2016, 21(6):786-796.

- Fromentin S, Forslund SK, Chechi K, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Chakaroun R, Nielsen T, Tremaroli V, Ji B, Prifti E, Myridakis A et al: Microbiome and metabolome features of the cardiometabolic disease spectrum. Nat Med 2022, 28(2):303-314.

- Gilbert JA, Blaser MJ, Caporaso JG, Jansson JK, Lynch SV, Knight R: Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat Med 2018, 24(4):392-400.

- Nemet I, Saha PP, Gupta N, Zhu W, Romano KA, Skye SM, Cajka T, Mohan ML, Li L, Wu Y et al: A Cardiovascular Disease-Linked Gut Microbial Metabolite Acts via Adrenergic Receptors. Cell 2020, 180(5):862-877 e822.

- Kummen M, Mayerhofer CCK, Vestad B, Broch K, Awoyemi A, Storm-Larsen C, Ueland T, Yndestad A, Hov JR, Troseid M: Gut Microbiota Signature in Heart Failure Defined From Profiling of 2 Independent Cohorts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 71(10):1184-1186.

- Hietbrink F, Besselink MG, Renooij W, de Smet MB, Draisma A, van der Hoeven H, Pickkers P: Systemic inflammation increases intestinal permeability during experimental human endotoxemia. Shock 2009, 32(4):374-378.

- Mu F, Tang M, Guan Y, Lin R, Zhao M, Zhao J, Huang S, Zhang H, Wang J, Tang H: Knowledge Mapping of the Links Between the Gut Microbiota and Heart Failure: A Scientometric Investigation (2006-2021). Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9:882660.

- Lupu VV, Adam Raileanu A, Mihai CM, Morariu ID, Lupu A, Starcea IM, Frasinariu OE, Mocanu A, Dragan F, Fotea S: The Implication of the Gut Microbiome in Heart Failure. Cells 2023, 12(8).

- Ferranti EP, Dunbar SB, Dunlop AL, Corwin EJ: 20 things you didn't know about the human gut microbiome. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014, 29(6):479-481.

- Beam A, Clinger E, Hao L: Effect of Diet and Dietary Components on the Composition of the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13(8).

- Hall AB, Tolonen AC, Xavier RJ: Human genetic variation and the gut microbiome in disease. Nat Rev Genet 2017, 18(11):690-699.

- Koppel N, Maini Rekdal V, Balskus EP: Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science 2017, 356(6344).

- Sonnenburg JL, Backhed F: Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 2016, 535(7610):56-64.

- Brown JM, Hazen SL: Targeting of microbe-derived metabolites to improve human health: The next frontier for drug discovery. J Biol Chem 2017, 292(21):8560-8568.

- Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmora N, Israeli D, Rothschild D, Weinberger A, Ben-Yacov O, Lador D, Avnit-Sagi T, Lotan-Pompan M et al: Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses. Cell 2015, 163(5):1079-1094.

- Marques FZ, Nelson E, Chu PY, Horlock D, Fiedler A, Ziemann M, Tan JK, Kuruppu S, Rajapakse NW, El-Osta A et al: High-Fiber Diet and Acetate Supplementation Change the Gut Microbiota and Prevent the Development of Hypertension and Heart Failure in Hypertensive Mice. Circulation 2017, 135(10):964-977.

- Goodrich JK, Waters JL, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Koren O, Blekhman R, Beaumont M, Van Treuren W, Knight R, Bell JT et al: Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell 2014, 159(4):789-799.

- Vatanen T, Kostic AD, d'Hennezel E, Siljander H, Franzosa EA, Yassour M, Kolde R, Vlamakis H, Arthur TD, Hamalainen AM et al: Variation in Microbiome LPS Immunogenicity Contributes to Autoimmunity in Humans. Cell 2016, 165(6):1551.

- Mayerhofer CCK, Ueland T, Broch K, Vincent RP, Cross GF, Dahl CP, Aukrust P, Gullestad L, Hov JR, Troseid M: Increased Secondary/Primary Bile Acid Ratio in Chronic Heart Failure. J Card Fail 2017, 23(9):666-671.

- Binah O, Rubinstein I, Bomzon A, Better OS: Effects of bile acids on ventricular muscle contraction and electrophysiological properties: studies in rat papillary muscle and isolated ventricular myocytes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1987, 335(2):160-165.

- Joubert P: An in vivo investigation of the negative chronotropic effect of cholic acid in the rat. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1978, 5(1):1-8.

- Gazawi H, Ljubuncic P, Cogan U, Hochgraff E, Ben-Shachar D, Bomzon A: The effects of bile acids on beta-adrenoceptors, fluidity, and the extent of lipid peroxidation in rat cardiac membranes. Biochem Pharmacol 2000, 59(12):1623-1628.

- Wang YD, Chen WD, Wang M, Yu D, Forman BM, Huang W: Farnesoid X receptor antagonizes nuclear factor kappaB in hepatic inflammatory response. Hepatology 2008, 48(5):1632-1643.

- Li YT, Swales KE, Thomas GJ, Warner TD, Bishop-Bailey D: Farnesoid x receptor ligands inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell inflammation and migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007, 27(12):2606-2611.

- Purcell NH, Tang G, Yu C, Mercurio F, DiDonato JA, Lin A: Activation of NF-kappa B is required for hypertrophic growth of primary rat neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98(12):6668-6673.

- Gordon JW, Shaw JA, Kirshenbaum LA: Multiple facets of NF-kappaB in the heart: to be or not to NF-kappaB. Circ Res 2011, 108(9):1122-1132.

- Pu J, Yuan A, Shan P, Gao E, Wang X, Wang Y, Lau WB, Koch W, Ma XL, He B: Cardiomyocyte-expressed farnesoid-X-receptor is a novel apoptosis mediator and contributes to myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Eur Heart J 2013, 34(24):1834-1845.

- Calkin AC, Tontonoz P: Transcriptional integration of metabolism by the nuclear sterol-activated receptors LXR and FXR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012, 13(4):213-224.

- Cook MD, Allen JM, Pence BD, Wallig MA, Gaskins HR, White BA, Woods JA: Exercise and gut immune function: evidence of alterations in colon immune cell homeostasis and microbiome characteristics with exercise training. Immunol Cell Biol 2016, 94(2):158-163.

- 55. Benedict C, Vogel H, Jonas W, Woting A, Blaut M, Schurmann A, Cedernaes J: Gut microbiota and glucometabolic alterations in response to recurrent partial sleep deprivation in normal-weight young individuals.

- Ying S, Zeng DN, Chi L, Tan Y, Galzote C, Cardona C, Lax S, Gilbert J, Quan ZX: The Influence of Age and Gender on Skin-Associated Microbial Communities in Urban and Rural Human Populations. PLoS One 2015, 10(10):e0141842.

- Zozaya M, Ferris MJ, Siren JD, Lillis R, Myers L, Nsuami MJ, Eren AM, Brown J, Taylor CM, Martin DH: Bacterial communities in penile skin, male urethra, and vaginas of heterosexual couples with and without bacterial vaginosis. Microbiome 2016, 4:16.

- Lax S, Smith DP, Hampton-Marcell J, Owens SM, Handley KM, Scott NM, Gibbons SM, Larsen P, Shogan BD, Weiss S et al: Longitudinal analysis of microbial interaction between humans and the indoor environment. Science 2014, 345(6200):1048-1052.

- David LA, Materna AC, Friedman J, Campos-Baptista MI, Blackburn MC, Perrotta A, Erdman SE, Alm EJ: Host lifestyle affects human microbiota on daily timescales. Genome Biol 2014, 15(7):R89.

- David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA et al: Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505(7484):559-563.

- Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Costello EK, Berg-Lyons D, Gonzalez A, Stombaugh J, Knights D, Gajer P, Ravel J, Fierer N et al: Moving pictures of the human microbiome. Genome Biol 2011, 12(5):R50.

- Knight R, Jansson J, Field D, Fierer N, Desai N, Fuhrman JA, Hugenholtz P, van der Lelie D, Meyer F, Stevens R et al: Unlocking the potential of metagenomics through replicated experimental design. Nat Biotechnol 2012, 30(6):513-520.

- Geva-Zatorsky N, Sefik E, Kua L, Pasman L, Tan TG, Ortiz-Lopez A, Yanortsang TB, Yang L, Jupp R, Mathis D et al: Mining the Human Gut Microbiota for Immunomodulatory Organisms. Cell 2017, 168(5):928-943 e911.

- Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L et al: Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med 2013, 19(5):576-585.

- Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL: Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2013, 368(17):1575-1584.

- Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM et al: Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472(7341):57-63.

- Zhao Y, Yang N, Gao J, Li H, Cai W, Zhang X, Ma Y, Niu X, Yang G, Zhou X et al: The Effect of Different l-Carnitine Administration Routes on the Development of Atherosclerosis in ApoE Knockout Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 2018, 62(5).

- Organ CL, Otsuka H, Bhushan S, Wang Z, Bradley J, Trivedi R, Polhemus DJ, Tang WH, Wu Y, Hazen SL et al: Choline Diet and Its Gut Microbe-Derived Metabolite, Trimethylamine N-Oxide, Exacerbate Pressure Overload-Induced Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail 2016, 9(1):e002314.

- Zhu W, Gregory JC, Org E, Buffa JA, Gupta N, Wang Z, Li L, Fu X, Wu Y, Mehrabian M et al: Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165(1):111-124.

- Bennett BJ, de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Wang Z, Shih DM, Meng Y, Gregory J, Allayee H, Lee R, Graham M, Crooke R et al: Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metab 2013, 17(1):49-60.

- Tang WH, Wang Z, Fan Y, Levison B, Hazen JE, Donahue LM, Wu Y, Hazen SL: Prognostic value of elevated levels of intestinal microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide in patients with heart failure: refining the gut hypothesis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 64(18):1908-1914.

- Tang WH, Wang Z, Shrestha K, Borowski AG, Wu Y, Troughton RW, Klein AL, Hazen SL: Intestinal microbiota-dependent phosphatidylcholine metabolites, diastolic dysfunction, and adverse clinical outcomes in chronic systolic heart failure. J Card Fail 2015, 21(2):91-96.

- Troseid M, Ueland T, Hov JR, Svardal A, Gregersen I, Dahl CP, Aakhus S, Gude E, Bjorndal B, Halvorsen B et al: Microbiota-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide is associated with disease severity and survival of patients with chronic heart failure. J Intern Med 2015, 277(6):717-726.

- Schuett K, Kleber ME, Scharnagl H, Lorkowski S, Marz W, Niessner A, Marx N, Meinitzer A: Trimethylamine-N-oxide and Heart Failure With Reduced Versus Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017, 70(25):3202-3204.

- Zhou X, Jin M, Liu L, Yu Z, Lu X, Zhang H: Trimethylamine N-oxide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction. ESC Heart Fail 2020, 7(1):188-193.

- Suzuki T, Heaney LM, Bhandari SS, Jones DJ, Ng LL: Trimethylamine N-oxide and prognosis in acute heart failure. Heart 2016, 102(11):841-848.

- Savi M, Bocchi L, Bresciani L, Falco A, Quaini F, Mena P, Brighenti F, Crozier A, Stilli D, Del Rio D: Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO)-Induced Impairment of Cardiomyocyte Function and the Protective Role of Urolithin B-Glucuronide. Molecules 2018, 23(3).

- Li X, Fan Z, Cui J, Li D, Lu J, Cui X, Xie L, Wu Y, Lin Q, Li Y: Trimethylamine N-Oxide in Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prognostic Value. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9:817396.

- Li DY, Tang WHW: Contributory Role of Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites Toward Cardiovascular Complications in Chronic Kidney Disease. Semin Nephrol 2018, 38(2):193-205.

- Tang WH, Wang Z, Kennedy DJ, Wu Y, Buffa JA, Agatisa-Boyle B, Li XS, Levison BS, Hazen SL: Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res 2015, 116(3):448-455.

- Vanholder R, Schepers E, Pletinck A, Nagler EV, Glorieux G: The uremic toxicity of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014, 25(9):1897-1907.

- Anand IS, Gupta P: Anemia and Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure: Current Concepts and Emerging Therapies. Circulation 2018, 138(1):80-98.

- Iorio A, Senni M, Barbati G, Greene SJ, Poli S, Zambon E, Di Nora C, Cioffi G, Tarantini L, Gavazzi A et al: Prevalence and prognostic impact of non-cardiac co-morbidities in heart failure outpatients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: a community-based study. Eur J Heart Fail 2018, 20(9):1257-1266.

- Schwartz AJ, Das NK, Ramakrishnan SK, Jain C, Jurkovic MT, Wu J, Nemeth E, Lakhal-Littleton S, Colacino JA, Shah YM: Hepatic hepcidin/intestinal HIF-2alpha axis maintains iron absorption during iron deficiency and overload. J Clin Invest 2019, 129(1):336-348.

- Xu MM, Wang J, Xie JX: Regulation of iron metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factors. Sheng Li Xue Bao 2017, 69(5):598-610.

- Mastrogiannaki M, Matak P, Peyssonnaux C: The gut in iron homeostasis: role of HIF-2 under normal and pathological conditions. Blood 2013, 122(6):885-892.

- Das NK, Schwartz AJ, Barthel G, Inohara N, Liu Q, Sankar A, Hill DR, Ma X, Lamberg O, Schnizlein MK et al: Microbial Metabolite Signaling Is Required for Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Cell Metab 2020, 31(1):115-130 e116.

- Malesza IJ, Bartkowiak-Wieczorek J, Winkler-Galicki J, Nowicka A, Dzieciolowska D, Blaszczyk M, Gajniak P, Slowinska K, Niepolski L, Walkowiak J et al: The Dark Side of Iron: The Relationship between Iron, Inflammation and Gut Microbiota in Selected Diseases Associated with Iron Deficiency Anaemia-A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14(17).

- Al-Sulaiti H, Diboun I, Agha MV, Mohamed FFS, Atkin S, Domling AS, Elrayess MA, Mazloum NA: Metabolic signature of obesity-associated insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. J Transl Med 2019, 17(1):348.

- Gurung M, Li Z, You H, Rodrigues R, Jump DB, Morgun A, Shulzhenko N: Role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 2020, 51:102590.

- Zhang Y, Gu Y, Ren H, Wang S, Zhong H, Zhao X, Ma J, Gu X, Xue Y, Huang S et al: Gut microbiome-related effects of berberine and probiotics on type 2 diabetes (the PREMOTE study). Nat Commun 2020, 11(1):5015.

- Pedersen HK, Gudmundsdottir V, Nielsen HB, Hyotylainen T, Nielsen T, Jensen BA, Forslund K, Hildebrand F, Prifti E, Falony G et al: Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature 2016, 535(7612):376-381.

- Lesko LJ, Atkinson AJ, Jr.: Use of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in drug development and regulatory decision making: criteria, validation, strategies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2001, 41:347-366.

- Shanahan F, Ghosh TS, O'Toole PW: The Healthy Microbiome-What Is the Definition of a Healthy Gut Microbiome? Gastroenterology 2021, 160(2):483-494.

- Ling Y, Gong T, Zhang J, Gu Q, Gao X, Weng X, Liu J, Sun J: Gut Microbiome Signatures Are Biomarkers for Cognitive Impairment in Patients With Ischemic Stroke. Front Aging Neurosci 2020, 12:511562.

- Schuijs MJ, Willart MA, Vergote K, Gras D, Deswarte K, Ege MJ, Madeira FB, Beyaert R, van Loo G, Bracher F et al: Farm dust and endotoxin protect against allergy through A20 induction in lung epithelial cells. Science 2015, 349(6252):1106-1110.

- Pascal M, Perez-Gordo M, Caballero T, Escribese MM, Lopez Longo MN, Luengo O, Manso L, Matheu V, Seoane E, Zamorano M et al: Microbiome and Allergic Diseases. Front Immunol 2018, 9:1584.

- Renz H, Brandtzaeg P, Hornef M: The impact of perinatal immune development on mucosal homeostasis and chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 12(1):9-23.

- Honda K, Littman DR: The microbiome in infectious disease and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol 2012, 30:759-795.

- Hofman P, Vouret-Craviari V: Microbes-induced EMT at the crossroad of inflammation and cancer. Gut Microbes 2012, 3(3):176-185.

- Salaspuro MP: Acetaldehyde, microbes, and cancer of the digestive tract. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2003, 40(2):183-208.

- Khan AA, Shrivastava A, Khurshid M: Normal to cancer microbiome transformation and its implication in cancer diagnosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1826(2):331-337.

- Sears CL, Garrett WS: Microbes, microbiota, and colon cancer. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15(3):317-328.

- Whisner CM, Athena Aktipis C: The Role of the Microbiome in Cancer Initiation and Progression: How Microbes and Cancer Cells Utilize Excess Energy and Promote One Another's Growth. Curr Nutr Rep 2019, 8(1):42-51.

- Peng J, Xiao X, Hu M, Zhang X: Interaction between gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease. Life Sci 2018, 214:153-157.

- Schirmer M, Franzosa EA, Lloyd-Price J, McIver LJ, Schwager R, Poon TW, Ananthakrishnan AN, Andrews E, Barron G, Lake K et al: Dynamics of metatranscription in the inflammatory bowel disease gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol 2018, 3(3):337-346.

- Zheng YY, Wu TT, Liu ZQ, Li A, Guo QQ, Ma YY, Zhang ZL, Xun YL, Zhang JC, Wang WR et al: Gut Microbiome-Based Diagnostic Model to Predict Coronary Artery Disease. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68(11):3548-3557.

- Liu H, Chen X, Hu X, Niu H, Tian R, Wang H, Pang H, Jiang L, Qiu B, Chen X et al: Alterations in the gut microbiome and metabolism with coronary artery disease severity. Microbiome 2019, 7(1):68.

- Liu M, Wang M, Peng T, Ma W, Wang Q, Niu X, Hu L, Qi B, Guo D, Ren G et al: Gut-microbiome-based predictive model for ST-elevation myocardial infarction in young male patients. Front Microbiol 2022, 13:1031878.

- Temraz S, Nassar F, Nasr R, Charafeddine M, Mukherji D, Shamseddine A: Gut Microbiome: A Promising Biomarker for Immunotherapy in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20(17).

- Lin H, He QY, Shi L, Sleeman M, Baker MS, Nice EC: Proteomics and the microbiome: pitfalls and potential. Expert Rev Proteomics 2019, 16(6):501-511.

- Ananthakrishnan AN: Microbiome-Based Biomarkers for IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2020, 26(10):1463-1469.

- Suzuki T, Yazaki Y, Voors AA, Jones DJL, Chan DCS, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Hillege HL et al: Association with outcomes and response to treatment of trimethylamine N-oxide in heart failure: results from BIOSTAT-CHF. Eur J Heart Fail 2019, 21(7):877-886.

- Savji N, Meijers WC, Bartz TM, Bhambhani V, Cushman M, Nayor M, Kizer JR, Sarma A, Blaha MJ, Gansevoort RT et al: The Association of Obesity and Cardiometabolic Traits With Incident HFpEF and HFrEF. JACC Heart Fail 2018, 6(8):701-709.

- Salzano A, Cassambai S, Yazaki Y, Israr MZ, Bernieh D, Wong M, Suzuki T: The Gut Axis Involvement in Heart Failure: Focus on Trimethylamine N-oxide. Cardiol Clin 2022, 40(2):161-169.

- Xu J, Yang Y: Gut microbiome and its meta-omics perspectives: profound implications for cardiovascular diseases. Gut Microbes 2021, 13(1):1936379.

- Dong Z, Zheng S, Shen Z, Luo Y, Hai X: Trimethylamine N-Oxide is Associated with Heart Failure Risk in Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Lab Med 2021, 52(4):346-351.

- den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM: The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res 2013, 54(9):2325-2340.

- Zhao T, Gu J, Zhang H, Wang Z, Zhang W, Zhao Y, Zheng Y, Zhang W, Zhou H, Zhang G et al: Sodium Butyrate-Modulated Mitochondrial Function in High-Insulin Induced HepG2 Cell Dysfunction. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020:1904609.

- Tang X, Ma S, Li Y, Sun Y, Zhang K, Zhou Q, Yu R: Evaluating the Activity of Sodium Butyrate to Prevent Osteoporosis in Rats by Promoting Osteal GSK-3beta/Nrf2 Signaling and Mitochondrial Function. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68(24):6588-6603.

- Kaye DM, Shihata WA, Jama HA, Tsyganov K, Ziemann M, Kiriazis H, Horlock D, Vijay A, Giam B, Vinh A et al: Deficiency of Prebiotic Fiber and Insufficient Signaling Through Gut Metabolite-Sensing Receptors Leads to Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2020, 141(17):1393-1403.

- Pluznick J: A novel SCFA receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes 2014, 5(2):202-207.

- Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL, Saeedi B, Scholz CC, Bayless AJ, Wilson KE, Glover LE, Kominsky DJ, Magnuson A et al: Crosstalk between Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Intestinal Epithelial HIF Augments Tissue Barrier Function. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17(5):662-671.

- van der Hee B, Wells JM: Microbial Regulation of Host Physiology by Short-chain Fatty Acids. Trends Microbiol 2021, 29(8):700-712.

- Niebauer J, Volk HD, Kemp M, Dominguez M, Schumann RR, Rauchhaus M, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ, Anker SD: Endotoxin and immune activation in chronic heart failure: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 1999, 353(9167):1838-1842.

- Zong X, Fan Q, Yang Q, Pan R, Zhuang L, Tao R: Phenylacetylglutamine as a risk factor and prognostic indicator of heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2022, 9(4):2645-2653.

- Romano KA, Nemet I, Prasad Saha P, Haghikia A, Li XS, Mohan ML, Lovano B, Castel L, Witkowski M, Buffa JA et al: Gut Microbiota-Generated Phenylacetylglutamine and Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail 2023, 16(1):e009972.

- Fang C, Zuo K, Jiao K, Zhu X, Fu Y, Zhong J, Xu L, Yang X: PAGln, an Atrial Fibrillation-Linked Gut Microbial Metabolite, Acts as a Promoter of Atrial Myocyte Injury. Biomolecules 2022, 12(8).

- Ren X, Wang X, Yuan M, Tian C, Li H, Yang X, Li X, Li Y, Yang Y, Liu N et al: Mechanisms and Treatments of Oxidative Stress in Atrial Fibrillation. Curr Pharm Des 2018, 24(26):3062-3071.

- Mesubi OO, Anderson ME: Atrial remodelling in atrial fibrillation: CaMKII as a nodal proarrhythmic signal. Cardiovasc Res 2016, 109(4):542-557.

- Triposkiadis F, Xanthopoulos A, Parissis J, Butler J, Farmakis D: Pathogenesis of chronic heart failure: cardiovascular aging, risk factors, comorbidities, and disease modifiers. Heart Fail Rev 2022, 27(1):337-344.

- Dias CK, Starke R, Pylro VS, Morais DK: Database limitations for studying the human gut microbiome. PeerJ Comput Sci 2020, 6:e289.

- Inkpen SA, Douglas GM, Brunet TDP, Leuschen K, Doolittle WF, Langille MGI: The coupling of taxonomy and function in microbiomes. Biology & Philosophy 2017, 32(6):1225-1243.

- Kamo T, Akazawa H, Suzuki JI, Komuro I: Novel Concept of a Heart-Gut Axis in the Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. Korean Circ J 2017, 47(5):663-669.

- Joice R, Yasuda K, Shafquat A, Morgan XC, Huttenhower C: Determining microbial products and identifying molecular targets in the human microbiome. Cell Metab 2014, 20(5):731-741.

- Zhu W, Wang Z, Tang WHW, Hazen SL: Gut Microbe-Generated Trimethylamine N-Oxide From Dietary Choline Is Prothrombotic in Subjects. Circulation 2017, 135(17):1671-1673.

- Zhernakova A, Kurilshikov A, Bonder MJ, Tigchelaar EF, Schirmer M, Vatanen T, Mujagic Z, Vila AV, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S et al: Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science 2016, 352(6285):565-569.

- Hata S, Okamura T, Kobayashi A, Bamba R, Miyoshi T, Nakajima H, Kitagawa N, Hashimoto Y, Majima S, Senmaru T et al: Gut Microbiota Changes by an SGLT2 Inhibitor, Luseogliflozin, Alters Metabolites Compared with Those in a Low Carbohydrate Diet in db/db Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14(17).

- Tuteja S, Ferguson JF: Gut Microbiome and Response to Cardiovascular Drugs. Circ Genom Precis Med 2019, 12(9):421-429.

- Alhajri N, Khursheed R, Ali MT, Abu Izneid T, Al-Kabbani O, Al-Haidar MB, Al-Hemeiri F, Alhashmi M, Pottoo FH: Cardiovascular Health and The Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem: The Impact of Cardiovascular Therapies on The Gut Microbiota. Microorganisms 2021, 9(10).

- Sanches Machado d'Almeida K, Ronchi Spillere S, Zuchinali P, Correa Souza G: Mediterranean Diet and Other Dietary Patterns in Primary Prevention of Heart Failure and Changes in Cardiac Function Markers: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2018, 10(1).

- Wang Z, Bergeron N, Levison BS, Li XS, Chiu S, Jia X, Koeth RA, Li L, Wu Y, Tang WHW et al: Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. Eur Heart J 2019, 40(7):583-594.

- Mayerhofer CCK, Kummen M, Holm K, Broch K, Awoyemi A, Vestad B, Storm-Larsen C, Seljeflot I, Ueland T, Bohov P et al: Low fibre intake is associated with gut microbiota alterations in chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2020, 7(2):456-466.

- Li J, Zhao F, Wang Y, Chen J, Tao J, Tian G, Wu S, Liu W, Cui Q, Geng B et al: Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the development of hypertension. Microbiome 2017, 5(1):14.

- Jie Z, Xia H, Zhong SL, Feng Q, Li S, Liang S, Zhong H, Liu Z, Gao Y, Zhao H et al: The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun 2017, 8(1):845.

- Chen X, Li HY, Hu XM, Zhang Y, Zhang SY: Current understanding of gut microbiota alterations and related therapeutic intervention strategies in heart failure. Chin Med J (Engl) 2019, 132(15):1843-1855.

- Ros M, Carrascosa JM: Current nutritional and pharmacological anti-aging interventions. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866(3):165612.

- McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, Nazroo J, Pendleton N, Degens H: Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 2016, 17(3):567-580.

- Godos J, Grosso G, Ferri R, Caraci F, Lanza G, Al-Qahtani WH, Caruso G, Castellano S: Mediterranean diet, mental health, cognitive status, quality of life, and successful aging in southern Italian older adults. Exp Gerontol 2023, 175:112143.

- De Filippis F, Pellegrini N, Vannini L, Jeffery IB, La Storia A, Laghi L, Serrazanetti DI, Di Cagno R, Ferrocino I, Lazzi C et al: High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut 2016, 65(11):1812-1821.

- Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, Power SE, O'Connor EM, Cusack S, Harris HM, Coakley M, Lakshminarayanan B, O'Sullivan O et al: Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature 2012, 488(7410):178-184.

- Kawano Y, Edwards M, Huang Y, Bilate AM, Araujo LP, Tanoue T, Atarashi K, Ladinsky MS, Reiner SL, Wang HH et al: Microbiota imbalance induced by dietary sugar disrupts immune-mediated protection from metabolic syndrome. Cell 2022, 185(19):3501-3519 e3520.

- Cai Y, Liu Y, Wu Z, Wang J, Zhang X: Effects of Diet and Exercise on Circadian Rhythm: Role of Gut Microbiota in Immune and Metabolic Systems. Nutrients 2023, 15(12).

- Frampton J, Murphy KG, Frost G, Chambers ES: Short-chain fatty acids as potential regulators of skeletal muscle metabolism and function. Nat Metab 2020, 2(9):840-848.

- Bermon S, Petriz B, Kajeniene A, Prestes J, Castell L, Franco OL: The microbiota: an exercise immunology perspective. Exerc Immunol Rev 2015, 21:70-79.

- Barton W, Penney NC, Cronin O, Garcia-Perez I, Molloy MG, Holmes E, Shanahan F, Cotter PD, O'Sullivan O: The microbiome of professional athletes differs from that of more sedentary subjects in composition and particularly at the functional metabolic level. Gut 2018, 67(4):625-633.

- Gan XT, Ettinger G, Huang CX, Burton JP, Haist JV, Rajapurohitam V, Sidaway JE, Martin G, Gloor GB, Swann JR et al: Probiotic administration attenuates myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure after myocardial infarction in the rat. Circ Heart Fail 2014, 7(3):491-499.

- Awoyemi A, Mayerhofer C, Felix AS, Hov JR, Moscavitch SD, Lappegard KT, Hovland A, Halvorsen S, Halvorsen B, Gregersen I et al: Rifaximin or Saccharomyces boulardii in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Results from the randomized GutHeart trial. EBioMedicine 2021, 70:103511.

- Roger AJ, Munoz-Gomez SA, Kamikawa R: The Origin and Diversification of Mitochondria. Curr Biol 2017, 27(21):R1177-R1192.

- Ni Lochlainn M, Nessa A, Sheedy A, Horsfall R, Garcia MP, Hart D, Akdag G, Yarand D, Wadge S, Baleanu AF et al: The PROMOTe study: targeting the gut microbiome with prebiotics to overcome age-related anabolic resistance: protocol for a double-blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2021, 21(1):407.

- Lynch SV, Pedersen O: The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N Engl J Med 2016, 375(24):2369-2379.

- Liang JQ, Li T, Nakatsu G, Chen YX, Yau TO, Chu E, Wong S, Szeto CH, Ng SC, Chan FKL et al: A novel faecal Lachnoclostridium marker for the non-invasive diagnosis of colorectal adenoma and cancer. Gut 2020, 69(7):1248-1257.

- van der Meulen TA, Harmsen HJM, Vila AV, Kurilshikov A, Liefers SC, Zhernakova A, Fu J, Wijmenga C, Weersma RK, de Leeuw K et al: Shared gut, but distinct oral microbiota composition in primary Sjogren's syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun 2019, 97:77-87.

- Shaukat A, Levin TR: Current and future colorectal cancer screening strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19(8):521-531.

- Pasolli E, Truong DT, Malik F, Waldron L, Segata N: Machine Learning Meta-analysis of Large Metagenomic Datasets: Tools and Biological Insights. PLoS Comput Biol 2016, 12(7):e1004977.

- Gacesa R, Kurilshikov A, Vich Vila A, Sinha T, Klaassen MAY, Bolte LA, Andreu-Sanchez S, Chen L, Collij V, Hu S et al: Environmental factors shaping the gut microbiome in a Dutch population. Nature 2022, 604(7907):732-739.

- Khan S, Kelly L: Multiclass Disease Classification from Microbial Whole-Community Metagenomes. Pac Symp Biocomput 2020, 25:55-66.

- Ghannam RB, Techtmann SM: Machine learning applications in microbial ecology, human microbiome studies, and environmental monitoring. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2021, 19:1092-1107.

- Goodswen SJ, Kennedy PJ, Ellis JT: Applying Machine Learning to Predict the Exportome of Bovine and Canine Babesia Species That Cause Babesiosis. Pathogens 2021, 10(6).

- Marcos-Zambrano LJ, Karaduzovic-Hadziabdic K, Loncar Turukalo T, Przymus P, Trajkovik V, Aasmets O, Berland M, Gruca A, Hasic J, Hron K et al: Applications of Machine Learning in Human Microbiome Studies: A Review on Feature Selection, Biomarker Identification, Disease Prediction and Treatment. Front Microbiol 2021, 12:634511.

- ff.

- Fernandes MR, Aggarwal P, Costa RGF, Cole AM, Trinchieri G: Targeting the gut microbiota for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2022, 22(12):703-722.

- Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Ahern A, Carbone C, Temko A, Claesson MJ, Gasbarrini A, Tortora G: Gut microbiome, big data and machine learning to promote precision medicine for cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17(10):635-648.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).