Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

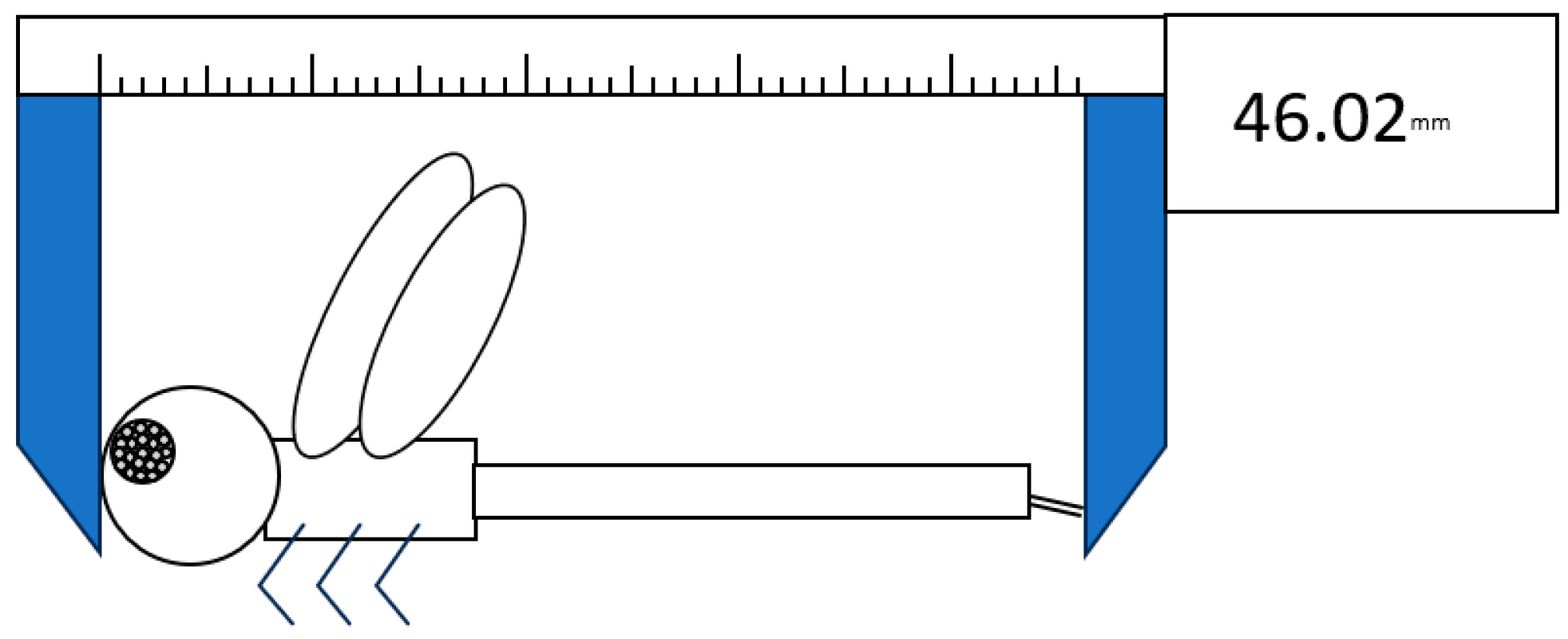

2.1. Measurement of Museum Specimens

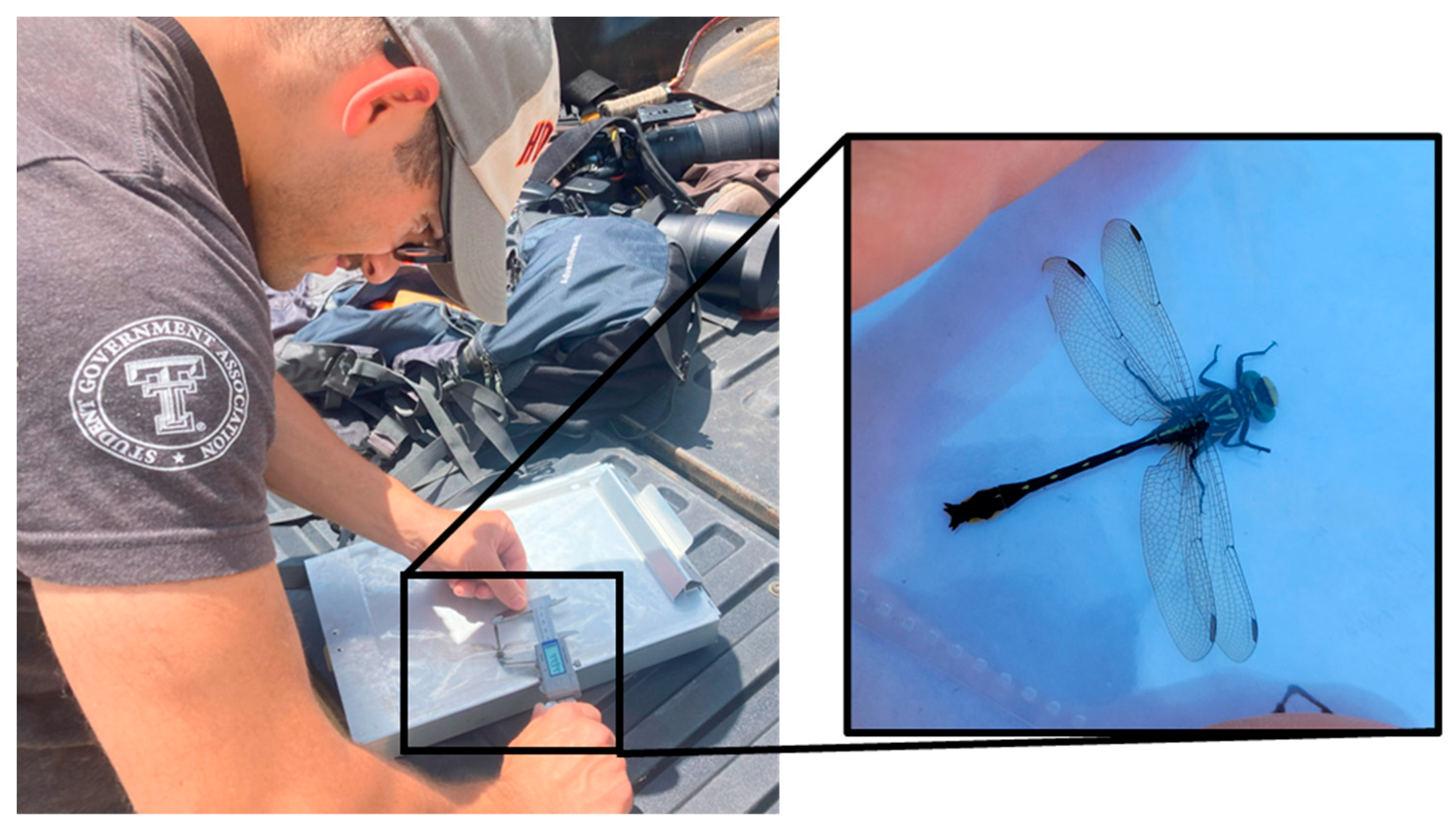

2.2. Selection of Field Locations and Live Specimen Measurements

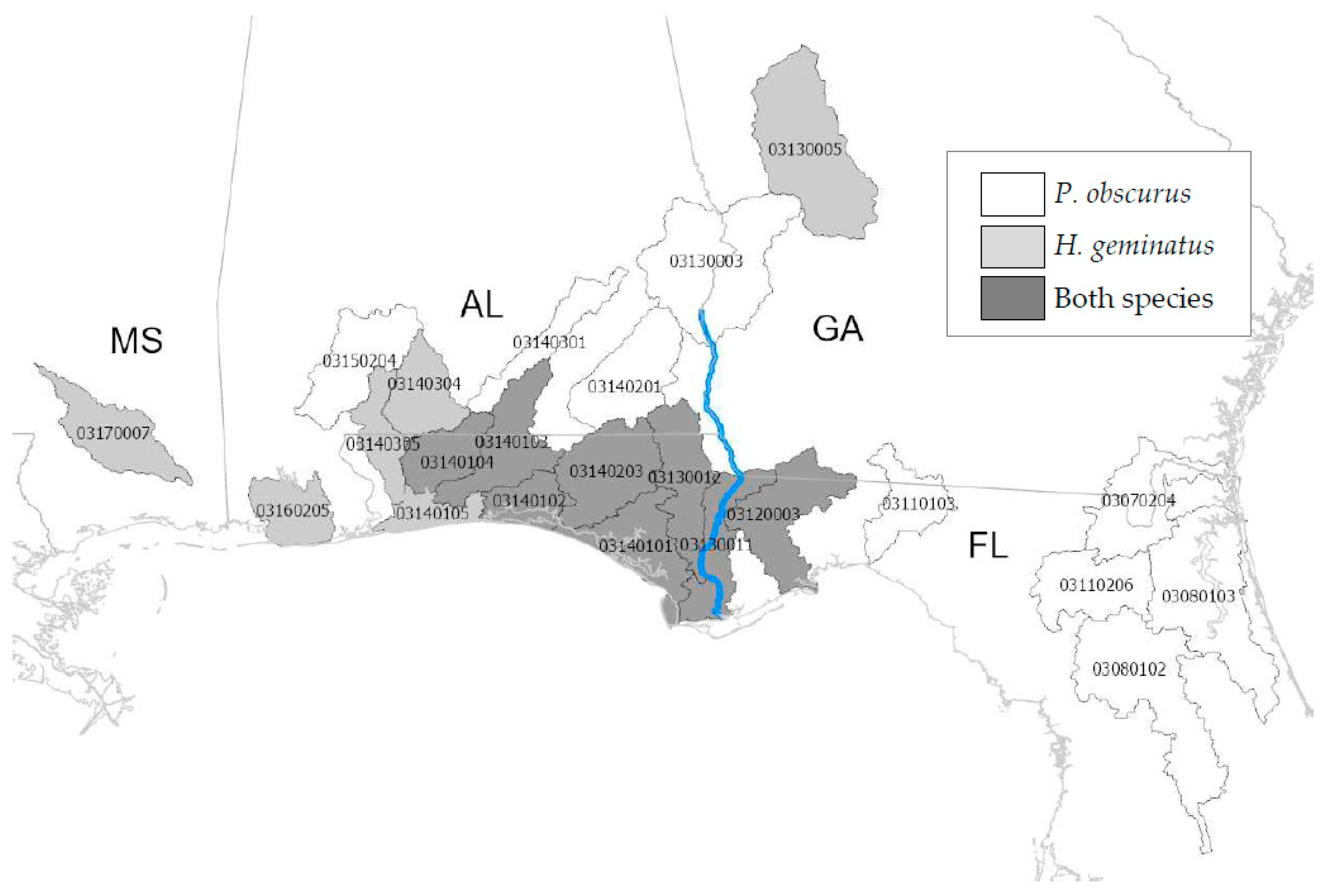

2.3. Watersheds

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

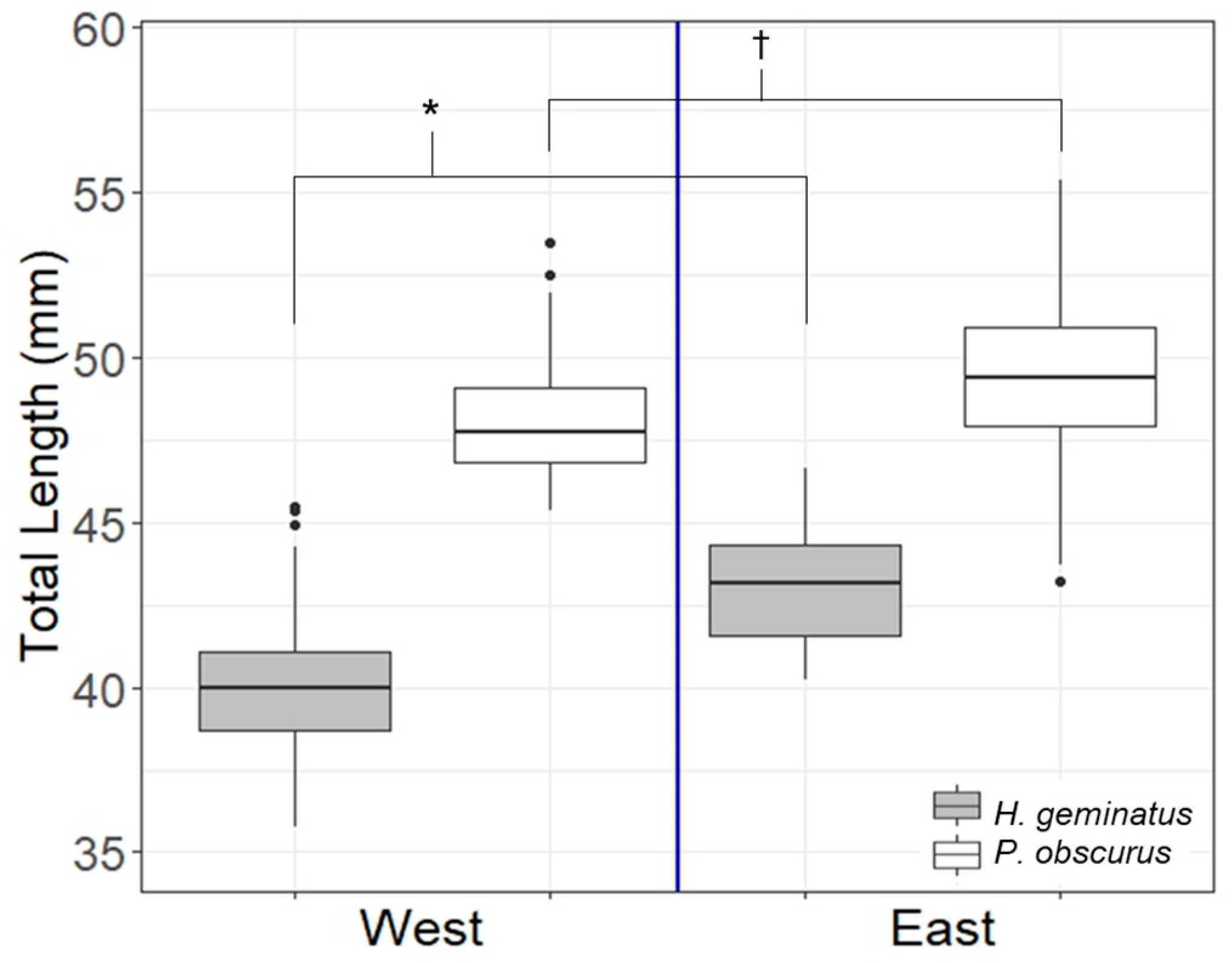

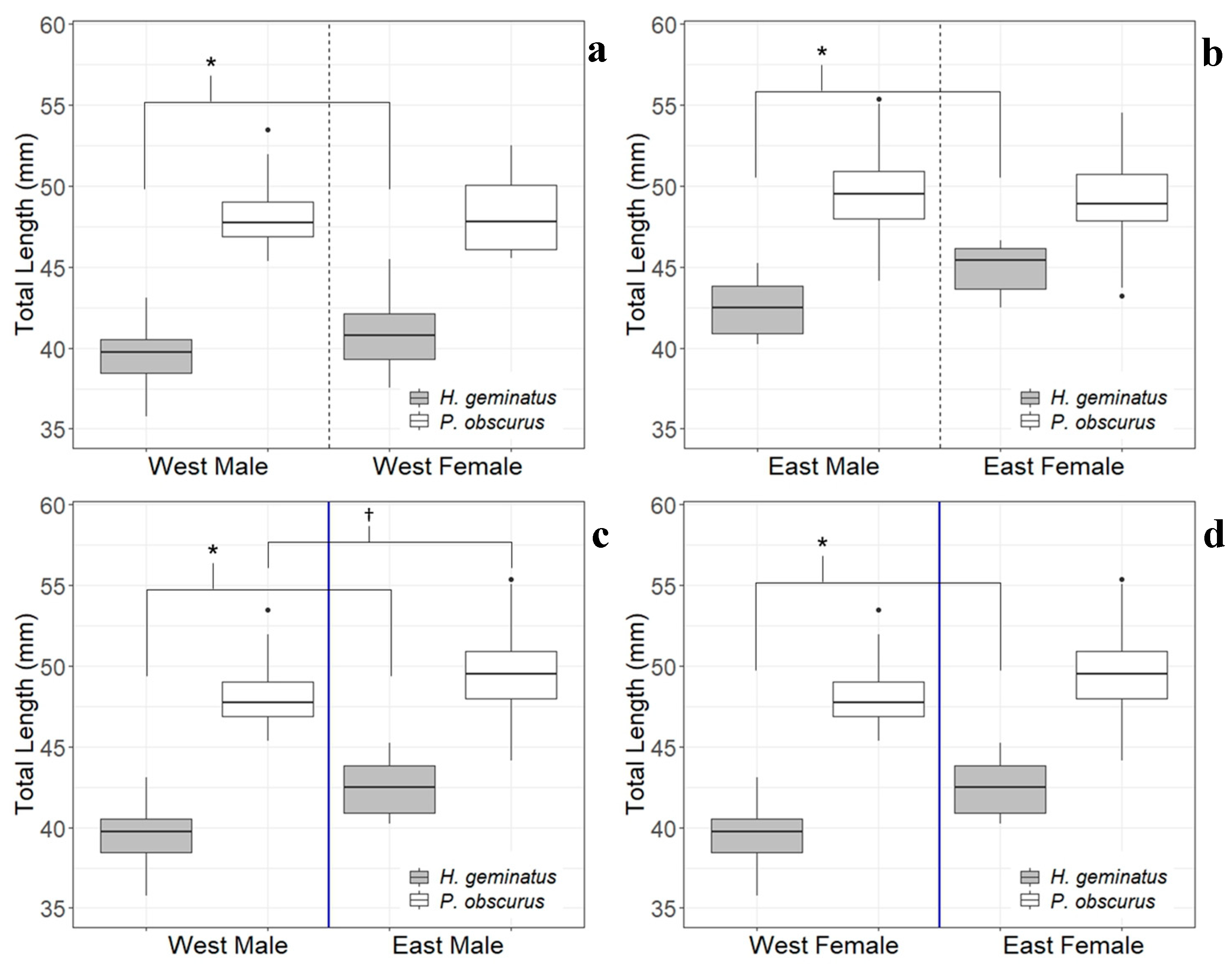

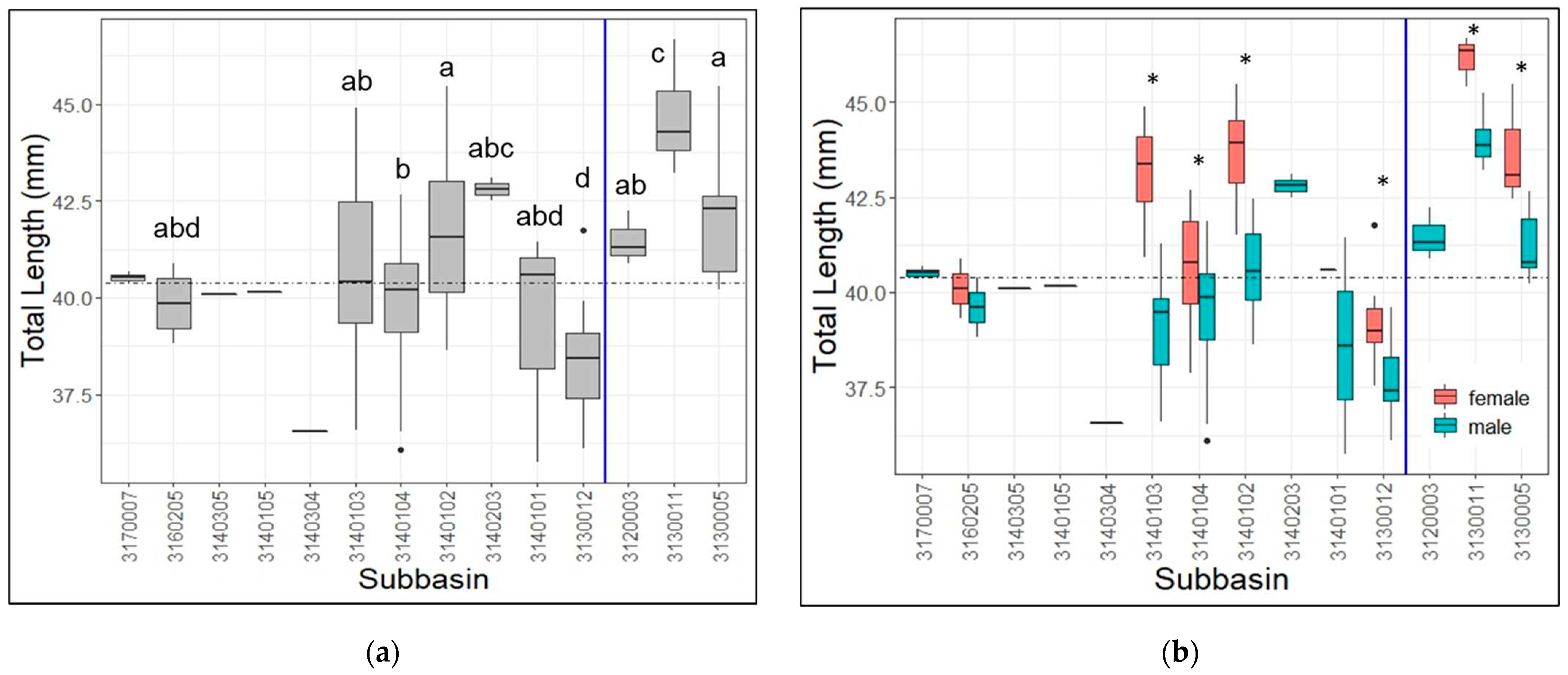

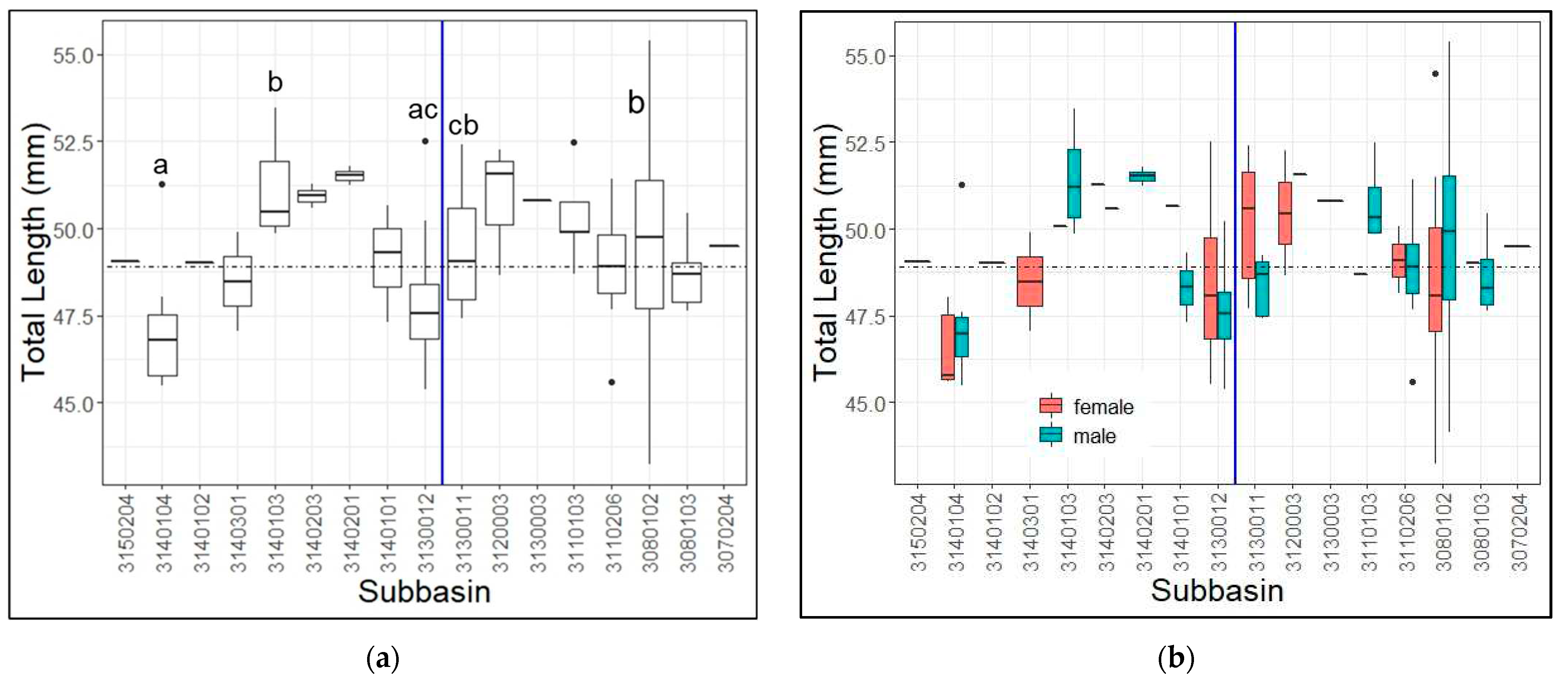

3.1. Patterns in Body Size

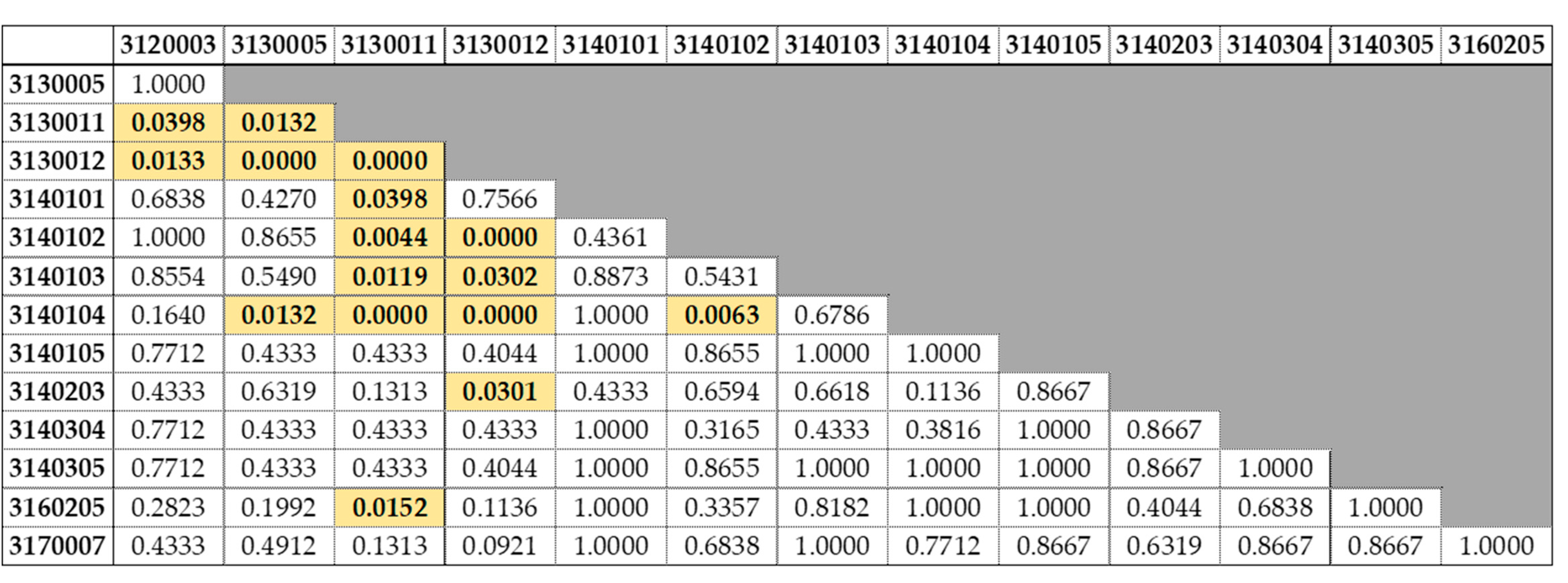

3.2. Lengths by Watershed

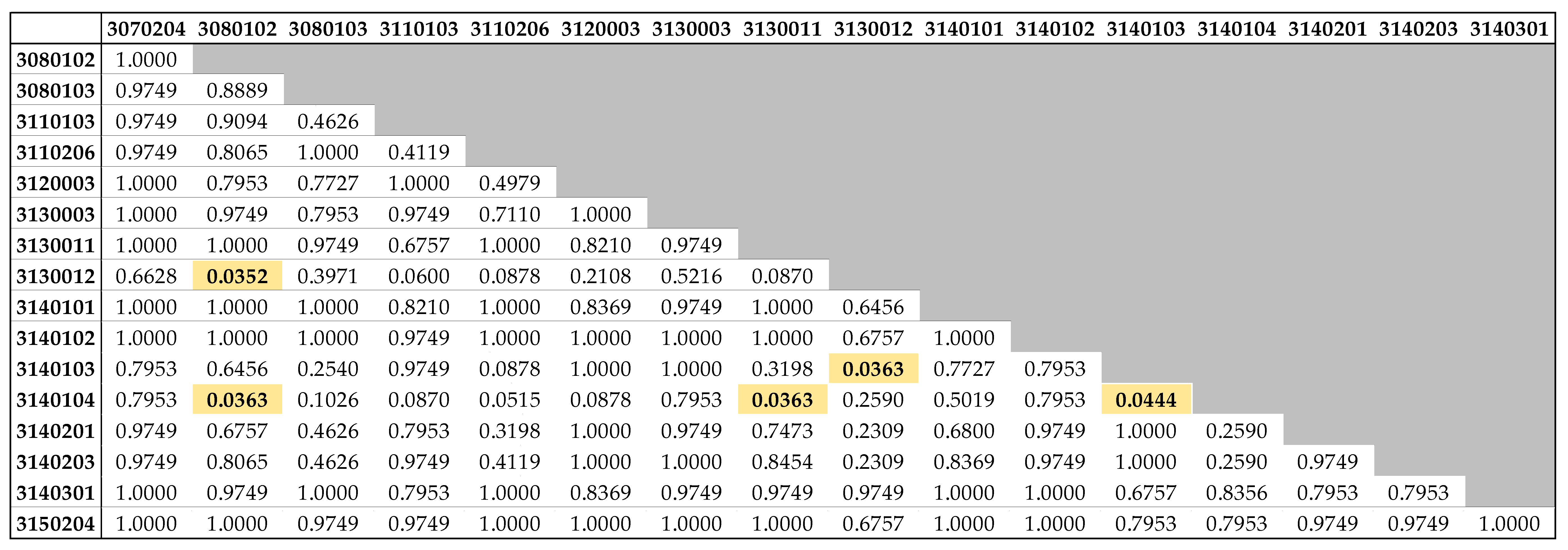

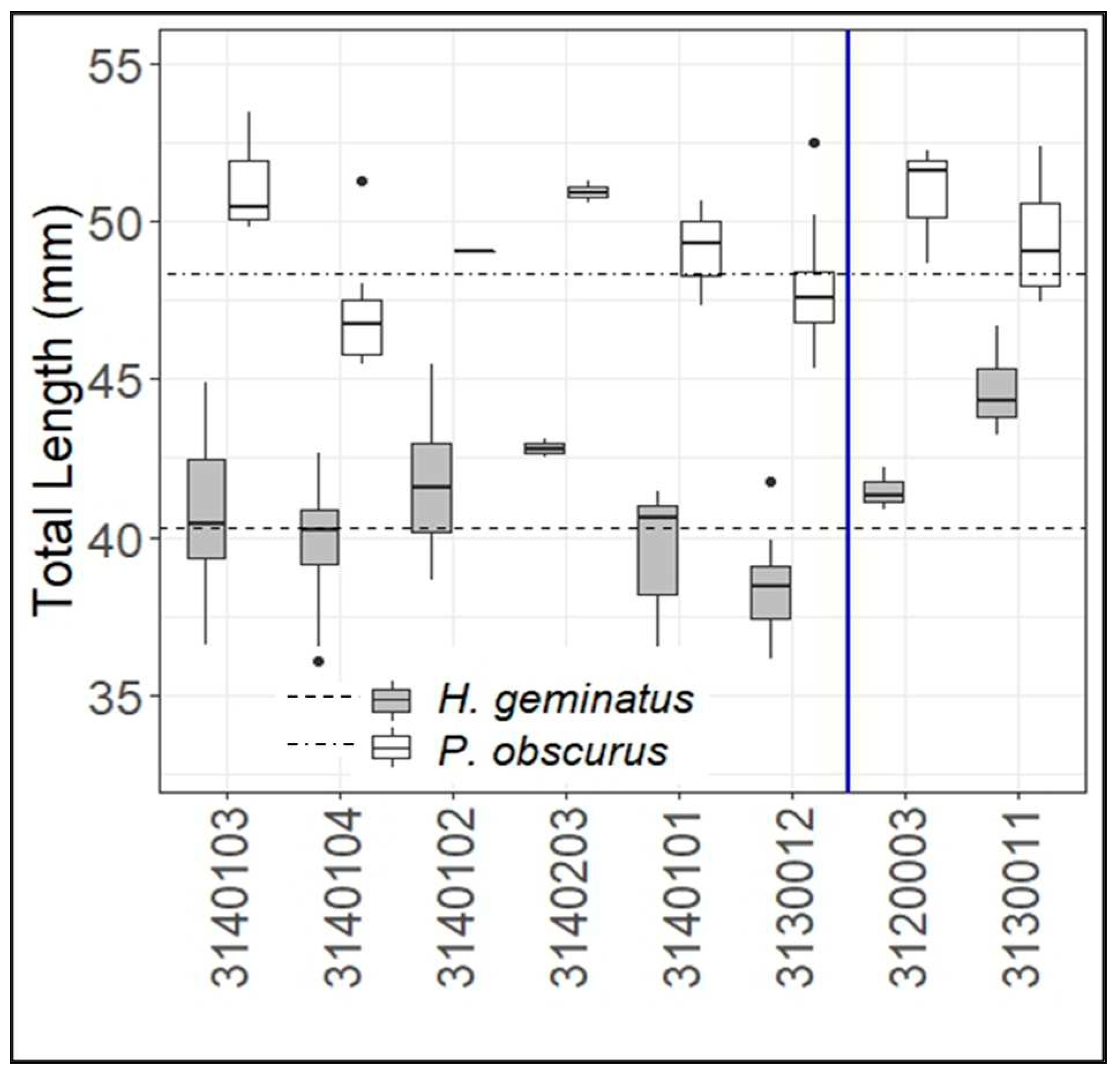

3.3. Comparisons of Body Size with Published Values

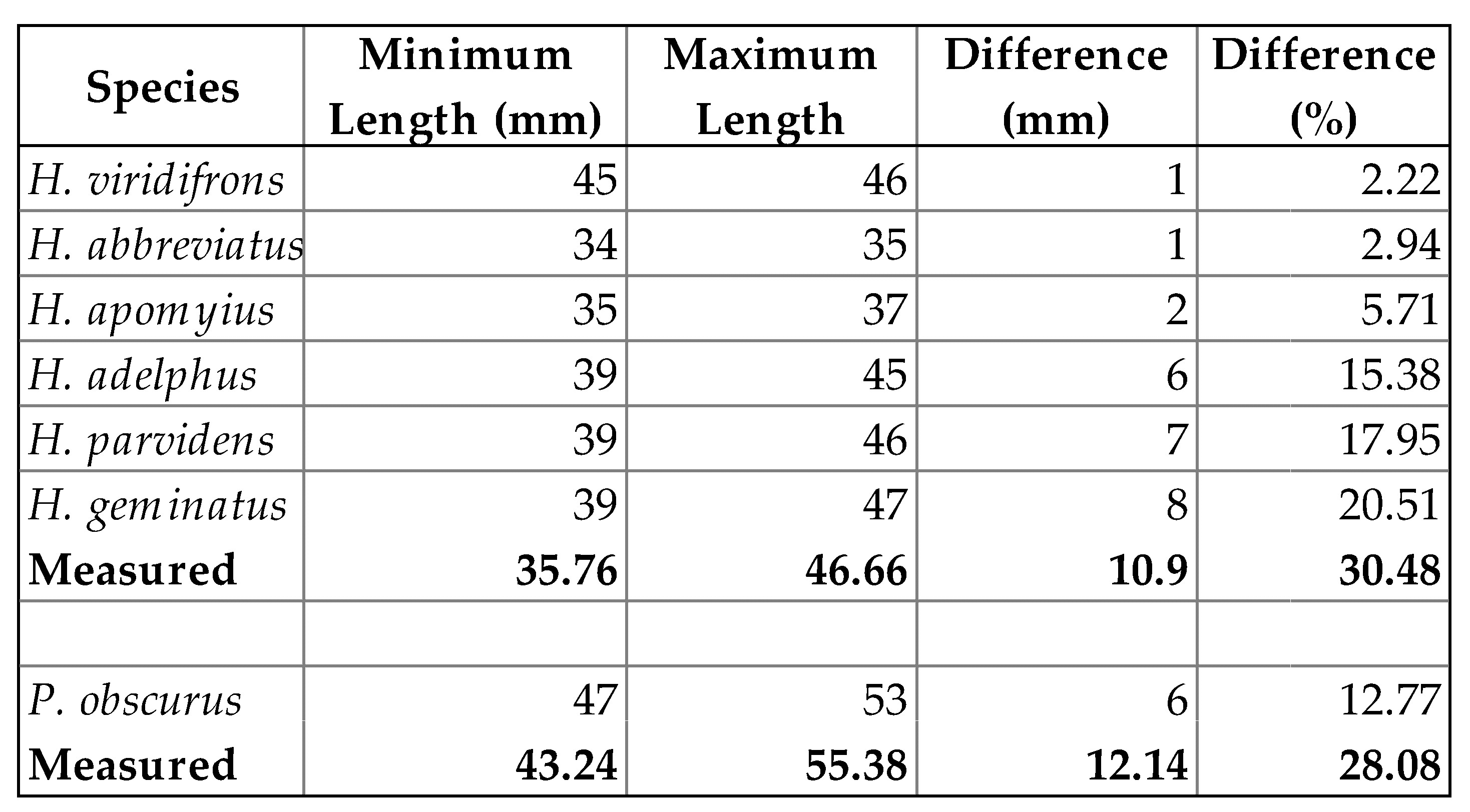

3.4. Land-cover Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Patterns in Body Size

4.2. Lengths by Watershed

4.3. Comparison of Body Size with Published Values

4.4. Land-cover Effects on Length

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Rocha-Ortega, M.; Khelifa, R.; Sandall, E.L.; Deacon, C.; Sánchez-Rivero, X.; Pinkert, S.; Patten, M.A. Linking traits to extinction risk in Odonata. In Dragonflies and Damselflies: Model Organisms for Ecological and Evolutionary Research, 2nd ed.; Córdoba-Aguilar, A., Beatty, C., Bried, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2023; pp. 343–358. [Google Scholar]

- Chichorro, F.; Juslén, A.; Cardoso, P. A review of the relation between species traits and extinction risk. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 237, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanzaib, M.; Kim, T.W. Exploring the influence of climate change-induced drought propagation on wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 149, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.K.; Wiederholm, T.; Rosenberg, D.M. Freshwater biomonitoring using individual organisms, populations, and species assemblages of benthic macroinvertebrates. In Freshwater Biomonitoring and Benthic Macroinvertebrates; Rosenberg, D.M., Resh, V.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Volume 488, pp. 39–158. [Google Scholar]

- Klok, C.J.; Harrison, J.F. The temperature size rule in arthropods: independent of macro-environmental variables but size dependent. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2013, 53, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonglersak, R.; Fenberg, P.B.; Langdon, P.G.; Brooks, S.J.; Price, B.W. Insect body size changes under future warming projections: A case study of Chironomidae (Insecta: Diptera). Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 2785–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertli, B. The use of dragonflies in the assessment and monitoring of aquatic habitats. In Dragonflies and Damselflies: Model Organisms for Ecological and Evolutionary Research; Córdoba-Aguilar, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2008; pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Samways, M. Dragonflies as focal organisms in contemporary conservation biology. In Dragonflies and Damselflies: Model Organisms for Ecological and Evolutionary Research; Córdoba-Aguilar, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2008; pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Šigutová, H.; Dolný, A.; Samways, M.; Hardersen, S.; Oliveira-Junior, J.; Juen, L.; Van Dinh, K.; Bried, J. Odonata as indicators of pollution, habitat quality, and landscape disturbance. In Dragonflies and Damselflies: Model Organisms for Ecological and Evolutionary Research, 2nd ed.; Córdoba-Aguilar, A., Beatty, C., Bried, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2023; pp. 371–384. [Google Scholar]

- Goldener, J.T.; Holland, J.D. Wing morphology of a damselfly exhibits local variation in response to forest fragmentation. Oecologia 2023, 202, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudová, P.; Boukal, D.S.; Klecka, J. Prey selectivity and the effect of diet on growth and development of a dragonfly, Sympetrum sanguineum. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautz, R.S. Land use and land cover trends in Florida 1936–1995. Fla. Sci. 1998, 171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Volk, M.; Hoctor, T.; Nettles, B.; Hilsenbeck, R.; Putz, F.; Oetting, J. Florida land use and land cover change in the past 100 years. In Florida's Climate: Changes, Variations, & Impacts; Chassignet, E., Jones, J., Misra, V., Obeysekera, J., Eds.; Florida Climate Institute: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 51–82. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J. Urbanization and land use change in Florida and the South. In Current Issues Associated with Land Values and Land Use Planning: Proceedings of a Regional Workshop; Bergstrom, J., Ed.; Bergstrom, J., Ed.; Southern Rural Development Center and Farm Foundation: Mississippi, USA, 2001; pp. 28–49. [Google Scholar]

- Suhling, F.; Suhling, I.; Richter, O. Temperature response of growth of larval dragonflies–an overview. Int. J. Odonatol. 2015, 18, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonglersak, R.; Fenberg, P.B.; Langdon, P.G.; Brooks, S.J.; Price, B.W. Temperature-body size responses in insects: a case study of British Odonata. Ecol. Entomol. 2020, 45, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.J. Towards a realistic predator-prey model: The effect of temperature on the functional response and life history of larvae of the damselfly, Ischnura elegans. J. Anim. Ecol. 1978, 47, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, T.J.; Mathavan, S.; Jeyagopal, C.P. Influence of temperature and body weight on mosquito predation by the dragonfly nymph Mesogomphus lineatus. Hydrobiologia 1979, 62, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresens, S.E.; Cothran, M.L.; Thorp, J.H. The influence of temperature on the functional response of the dragonfly Celithemis fasciata (Odonata: Libellulidae). Oecologia 1982, 53, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, T.P.; Luiza-Andrade, A.; Cabette, H.S.R.; Juen, L. How does environmental variation affect the distribution of dragonfly larvae (Odonata) in the Amazon-Cerrado transition zone in Central Brazil? Neotrop. Entomol. 2018, 47, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.B.; Boyer, E.W.; Smith, R.A.; Schwartz, G.E.; Moore, R.B. The role of headwater streams in downstream water quality. J. Am. Water. Resour. Assoc. Association 2007, 43, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carle, F. Two new Gomphus (Odonata: Gomphidae) from eastern North America with adult keys to the subgenus Hylogomphus. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1979, 72, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigle, J.J. (Gainesville, FL, USA); Personal communication, 2021.

- The Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River National Water Quality Assessment (NAWQA) Program study. Available online: https://www2.usgs.gov/water/southatlantic/ga/nawqa/basin/apalachicola-basin.html (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- De Block, M.; Stoks, R. Life-history variation in relation to time constraints in a damselfly. Oecologia 2004, 140, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorslaer, W.; Stoks, R. Growth rate plasticity to temperature in two damselfly species differing in latitude: contributions of behaviour and physiology. Oikos 2005, 111, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Block, M.; Slos, S.; Johansson, F.; Stoks, R. Integrating life history and physiology to understand latitudinal size variation in a damselfly. Ecography 2008, 31, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campero, M.; De Block, M.; Ollevier, F.; Stoks, R. Correcting the short-term effect of food deprivation in a damselfly: mechanisms and costs. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolovska, N.; Rowe, L.; Johansson, F. Fitness and body size in mature odonates. Ecol. Entomol. 2008, 25, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Pérez, U.; May, M.L.; Córdoba-Aguilar, A. Thermoregulation in Odonata. In Dragonflies and Damselflies: Model Organisms for Ecological and Evolutionary Research, 2nd ed.; Córdoba-Aguilar, A., Beatty, C., Bried, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2023; pp. 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Siepielski, A.M.; Gómez-Llano, M.; Haski, A.Z. Evolutionary community ecology of Odonata. In Dragonflies and Damselflies: Model Organisms for Ecological and Evolutionary Research, 2nd ed.; Córdoba-Aguilar, A., Beatty, C., Bried, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2023; pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, R.J.; Iverson, R.L.; Estabrook, R.H.; Keys, V.E.; Taylor Jr, J. Major features of the Apalachicola Bay system: physiography, biota, and resource management. Fla. Sci. 1974, 245–271. [Google Scholar]

- May, M.L. A critical overview of progress in studies of migration of dragonflies (Odonata: Anisoptera), with emphasis on North America. J. Insect. Conserv. 2013, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NatureServe. 2022. Available online: https://explorer.natureserve.org (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Hydrologic Unit Codes (HUCs) Explained. Available online: https://nas.er.usgs.gov/hucs.aspx (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- [dataset] USGS. 2021. Watershed Boundary Dataset. v2.3.1. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/national-hydrography/access-national-hydrography-products.

- [dataset] FWC & FNAI. 2022. Florida Cooperative Landcover Map. V3.6. Available online: https://myfwc.com/research/gis/wildlife/cooperative-land-cover/.

- Wickham, H. Data Analysis. In ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Publisher: Springer International Publishing New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series. B. Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, S. J. Body size and social dominance influence breeding dispersal in male Pachydiplax longipennis (Odonata). Ecol. Entomol. 2010, 35, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelibert, S.; Giani, N. Dispersal characteristics of three odonate species in a patchy habitat. Ecography. 2003, 26, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, G.H. Seasonal Variation in the adult size of Pachydiplax longipennis (Burmeister) (Odonata, Libellulidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1951, 44, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, F. Latitudinal shifts in body size of Enallagma cyathigerum (Odonata). J. Biogeogr. 2003, 30, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mähn, L.A.; Hof, C.; Brandl, R.; Pinkert, S. Beyond latitude: Temperature, productivity and thermal niche conservatism drive global body size variation in Odonata. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2023, 32, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, J.A.; Neal, C.; Jarvie, H.P; Doody, D.G. Agriculture and eutrophication: Where do we go from here? Sustainability. 2014, 6, 5853–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, G.H.; McDowell, L.L. Pesticides in agricultural runoff and their effects on downstream water quality. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1982, 1, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, C.W. Pesticide effects on aquatic habitats. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1982, 16, 48A–57A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hylogomphus geminatus | Progomphus obscurus |

|---|---|

| 3130011 | 3150204 |

| 3140105 | 3140104 |

| 3140104 | 3140102 |

| 3130012 | 3140301 |

| 3140103 | 3140103 |

| 3130005 | 3140203 |

| 3140304 | 3140201 |

| 3140305 | 3140101 |

| 3140102 | 3130012 |

| 3170007 | 3130011 |

| 3140101 | 3120003 |

| 3140203 | 3130003 |

| 3160205 | 3110103 |

| 3120003 | 3110206 |

| 3080102 | |

| 3080103 | |

| 3070204 |

| Land-cover Type | West of River | East of River |

|---|---|---|

| Upland/Sandhill | 10.9% | 21.7% |

| Perennial Wetland | 20.8% | 25.6% |

| Seasonal Wetland | 8.5% | 12.7% |

| Estuarine Wetland | 0.3% | 1.3% |

| Urban/Developed | 5.5% | 5.2% |

| Rural/Agriculture | 54.1% | 33.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).