Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

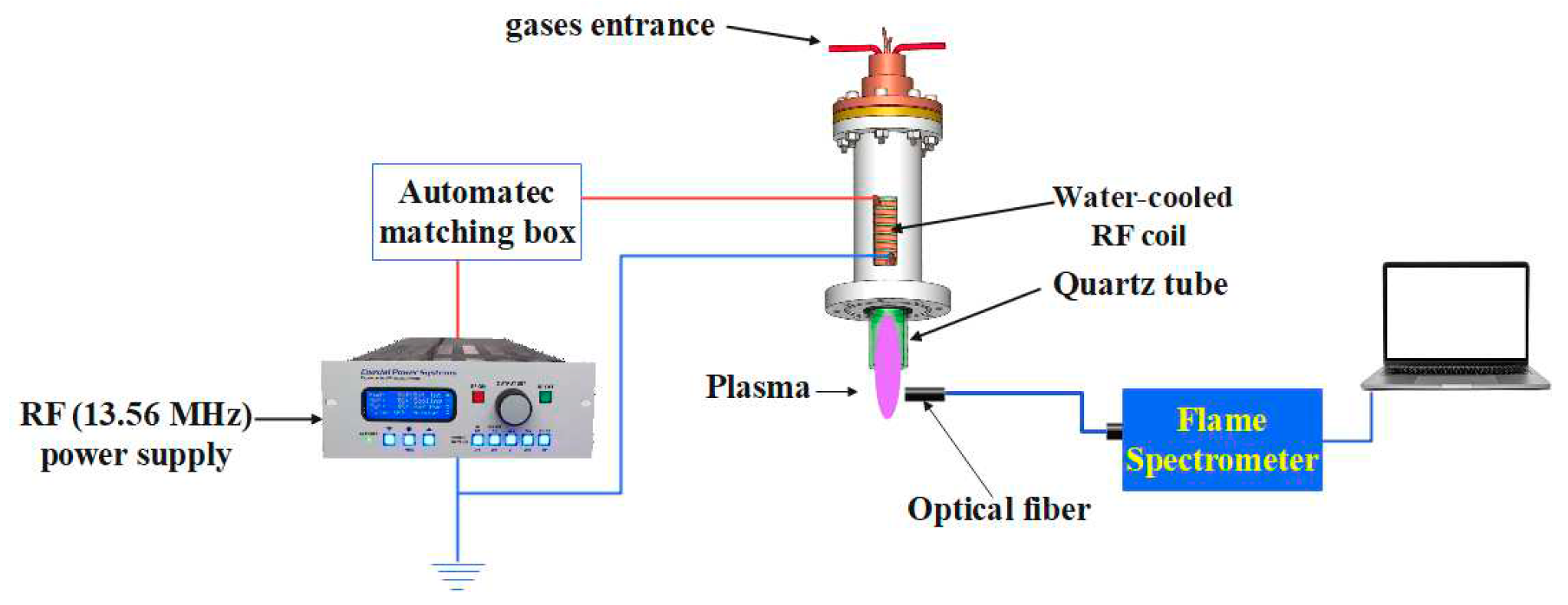

II. Experimental setup

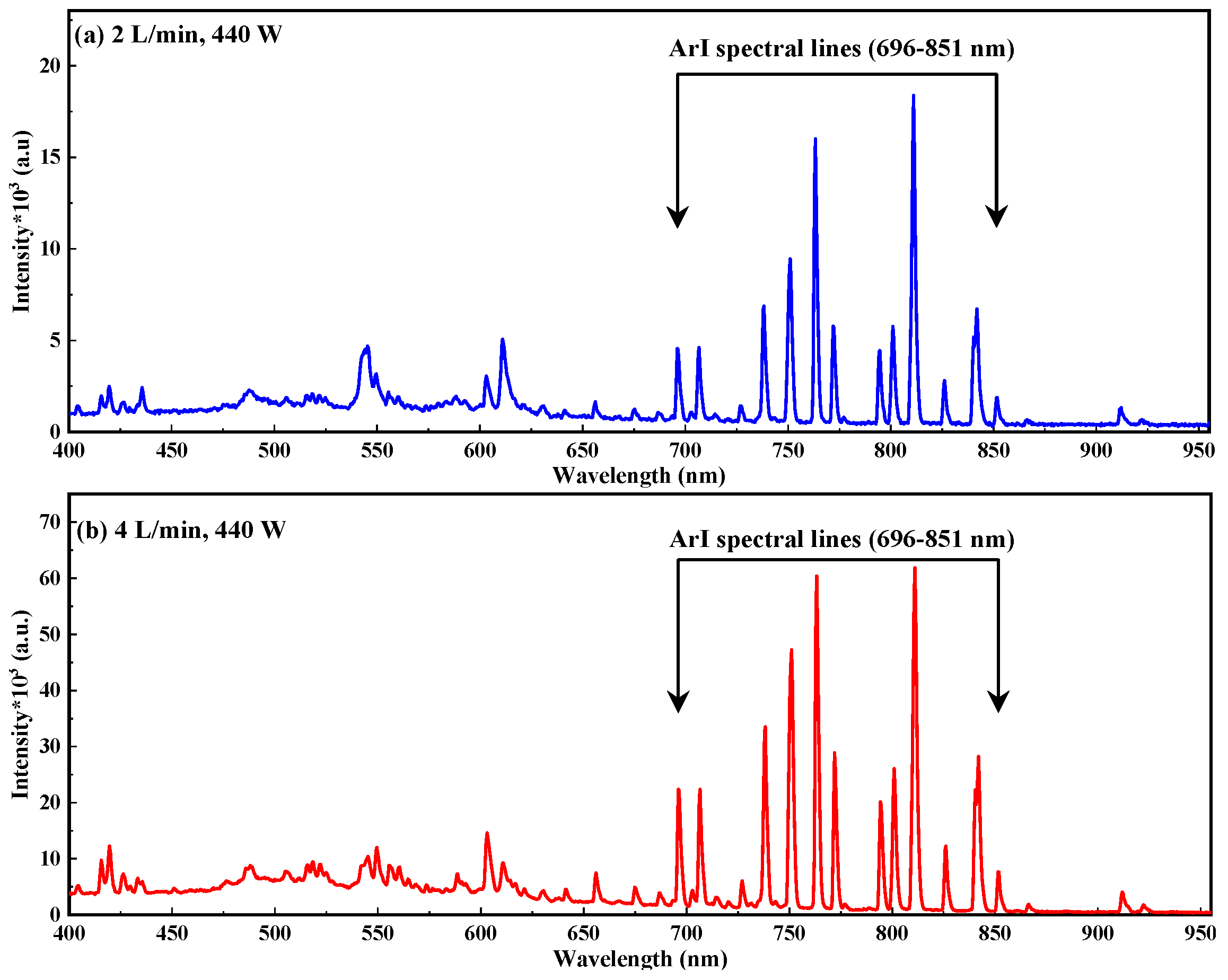

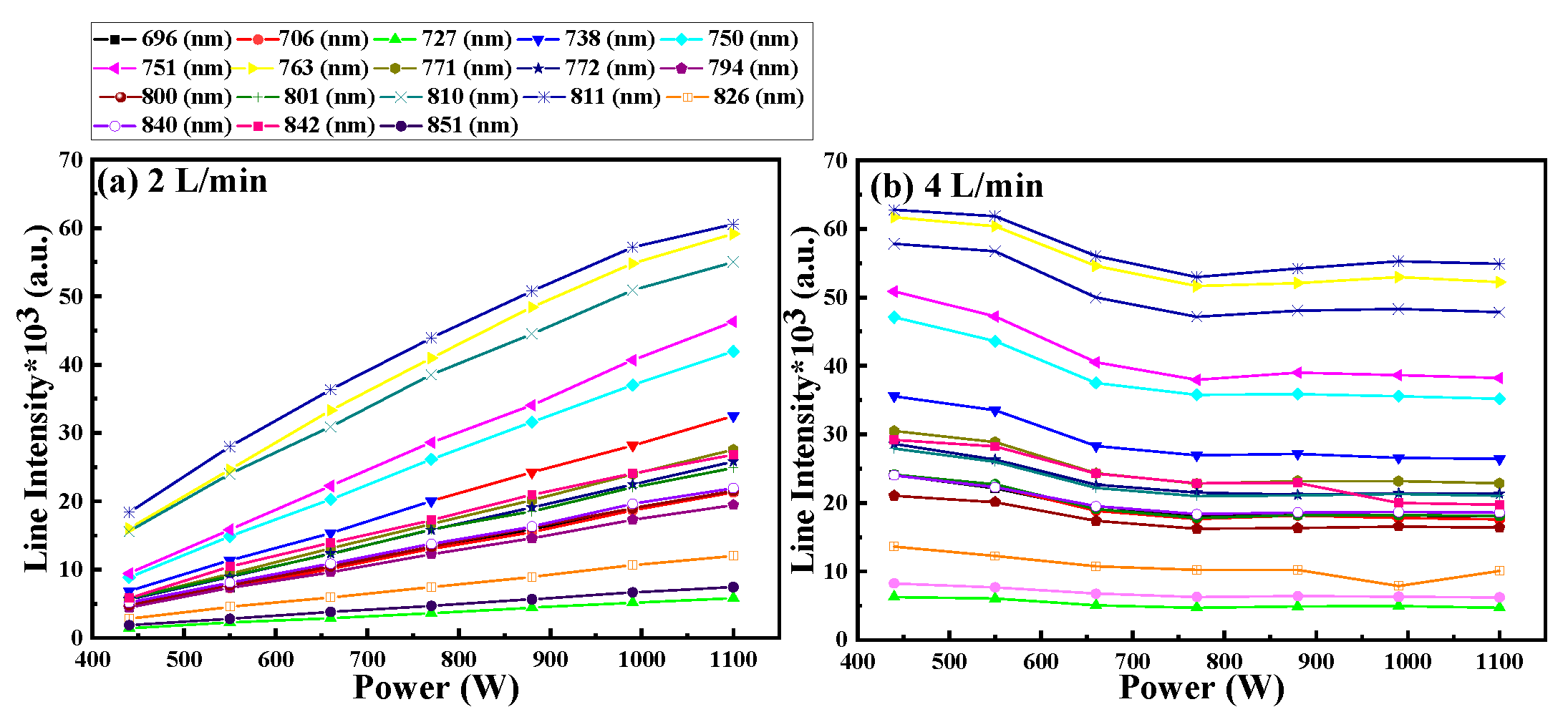

III. Result and discussion

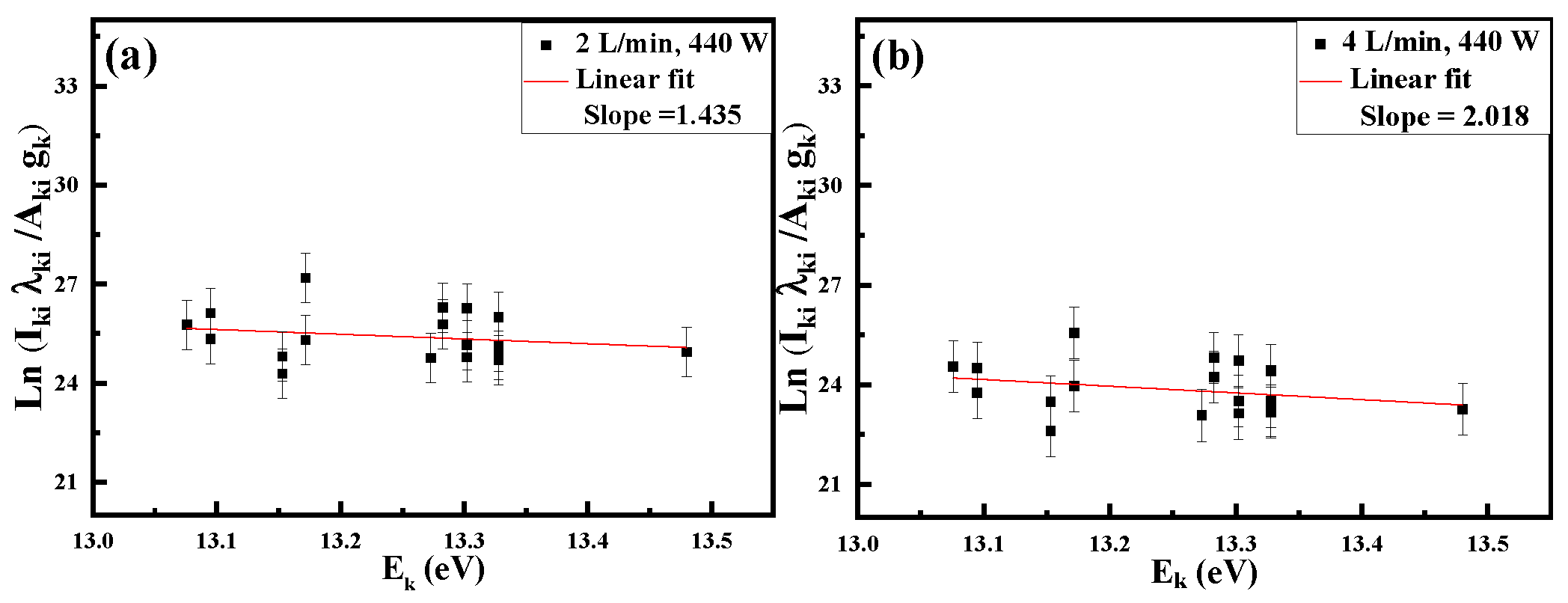

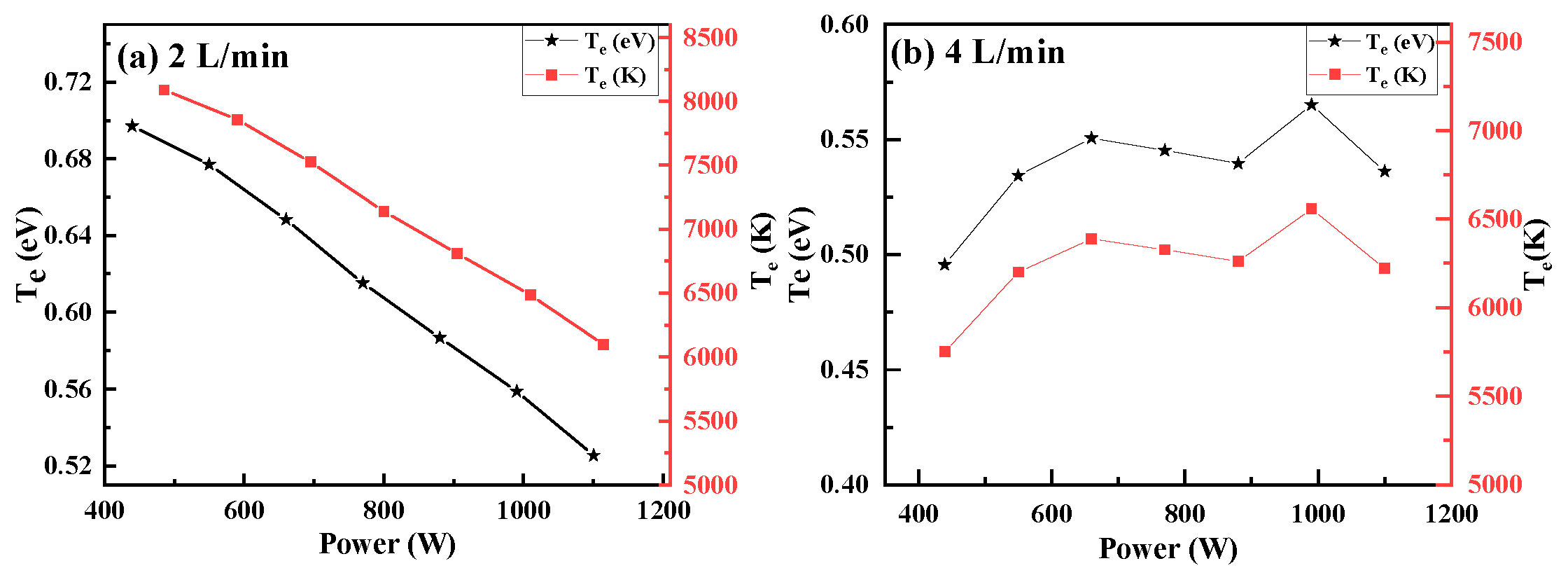

A. Excitation temperature

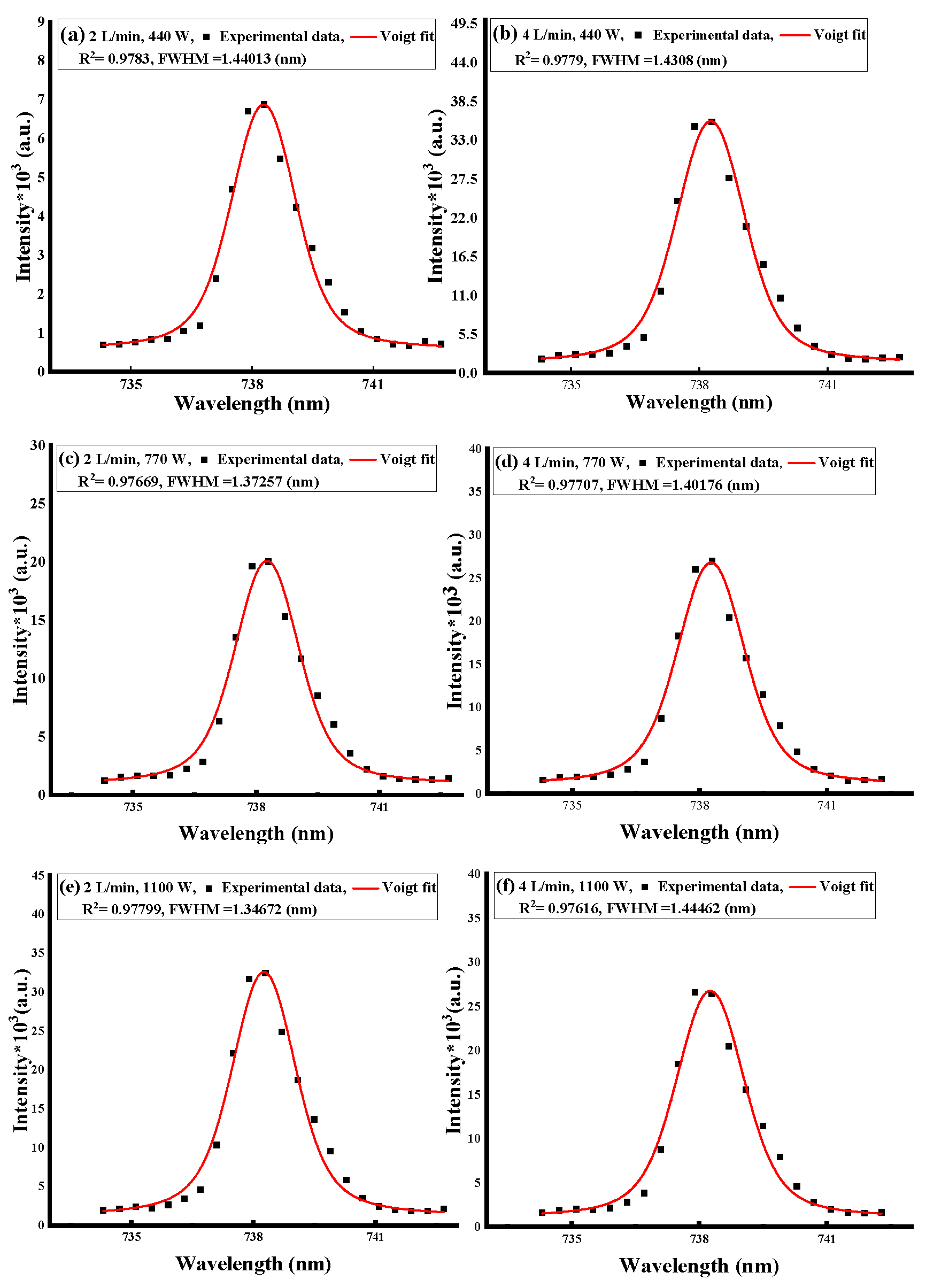

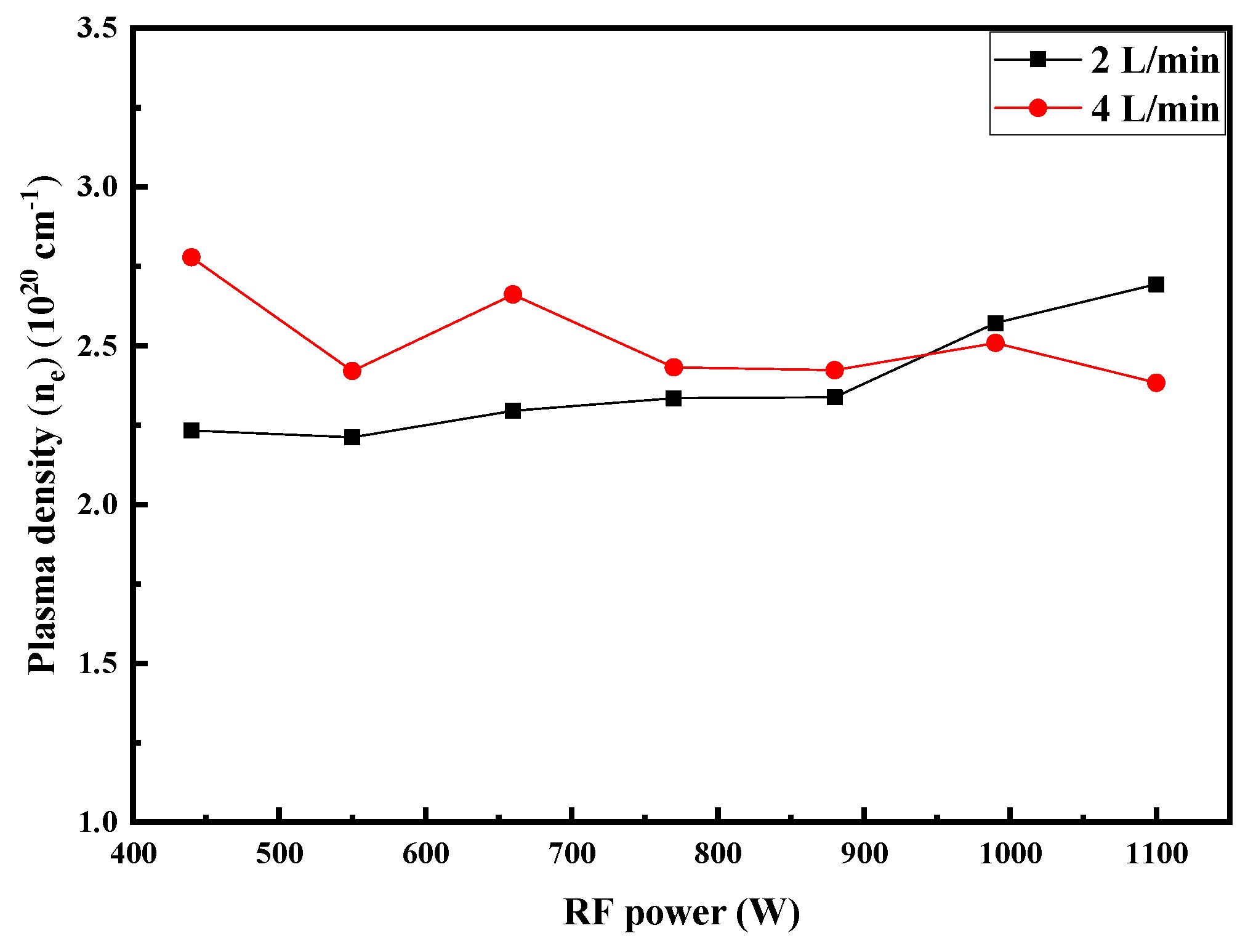

B. Electron density

IV. Conclusion

References

- H. E.-D. M. Saleh and H. E.-D. M. Saleh. Municipal Solid Waste Management. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, D.; Chong, Z.; Li, E.; Kong, X. A review of municipal solid waste in China: characteristics, compositions, influential factors and treatment technologies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 23, 6603–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Trends in Solid Waste Management.”. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/trends_in_solid_waste_management.html (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- New Science paper calculates magnitude of plastic waste going into the ocean - UGA Today.” https://news.uga.edu/new-science-paper-magnitude-plastic-waste-going-into-ocean-0215/ (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- A Nwachukwu, M.; Ronald, M.; Feng, H. Global capacity, potentials and trends of solid waste research and management. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2017, 35, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Ma, M.; Thompson, J.R.; Flower, R.J. Waste management, informal recycling, environmental pollution and public health. J. Epidemiology Community Heal. 2017, 72, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Alam, K. A.-I. J. of Sustainable, and undefined 2013, “Impact of solid waste on health and the environment,” intelligentjo.com, Accessed: Feb. 06, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://intelligentjo.com/images/Papers/general/waste/IMPACT-OF-SOLID-WASTE-ON-HEALTH-AND-THE-ENVIRONMENT.pdf.

- Das, S.; Lee, S.-H.; Kumar, P.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, S.S.; Bhattacharya, S.S. Solid waste management: Scope and the challenge of sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 658–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Rasheed, T.; Afreen, M.; Anwar, M.T.; Nawaz, Z.; Anwar, H.; Rizwan, K. Modalities for conversion of waste to energy — Challenges and perspectives. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 727, 138610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, K.; Loizidou, M.; Rehan, M.; Nizami, A. A review of recent developments in renewable and sustainable energy systems: Key challenges and future perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Rahman, G. Ishtiaq, and A. Amanat, “Assessment of Solid Waste Management and Sustainability Practices in District Swat, Pakistan,” PSM Microbiology, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 66–80, Sep. 2021, Accessed: Feb. 06, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://journals.psmpublishers.org/index.php/microbiol/article/view/587.

- Ghosal, D.; Kaur, R.; A Jadhav, D. Utilization and Management of Waste Derived Material for Sustainable Energy Production: A mini review. Acad. Lett. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, T.; Anwar, M.T.; Ahmad, N.; Sher, F.; Khan, S.U.-D.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, R.; Wazeer, I. Valorisation and emerging perspective of biomass based waste-to-energy technologies and their socio-environmental impact: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.S.; Oasmaa, A.; Pihkola, H.; Deviatkin, I.; Tenhunen, A.; Mannila, J.; Minkkinen, H.; Pohjakallio, M.; Laine-Ylijoki, J. Pyrolysis of plastic waste: Opportunities and challenges. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2020, 152, 104804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, J.; Chen, W.-H.; Tsang, D.C.; You, S. A critical review on the principles, applications, and challenges of waste-to-hydrogen technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Salaudeen, S.A.; Gilroyed, B.H.; Al-Salem, S.M.; Dutta, A. A review on co-pyrolysis of biomass with plastics and tires: recent progress, catalyst development, and scaling up potential. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, R. Rohit; Dhaka, A.K. A comprehensive review of the application of plasma gasification technology in circumventing the medical waste in a post-COVID-19 scenario. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, F.; Chen, Q. Optical Emission Spectroscopy Diagnostics of Atmospheric Pressure Radio Frequency Ar-H2 Inductively Coupled Thermal Plasma. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2020, 48, 3621–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.; Chéron, B.G.; Yan, J.H.; Cen, K.F. Electrical and spectroscopic diagnostic of an atmospheric double arc argon plasma jet. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2007, 16, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, A.Y.; Leys, C.; A Gonzalez, M.; Walsh, J.L. Electron density measurement in atmospheric pressure plasma jets: Stark broadening of hydrogenated and non-hydrogenated lines. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2015, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Fu, W.; Zhang, C.; Lu, D.; Han, M.; Yan, Y. Langmuir Probe Diagnostics with Optical Emission Spectrometry (OES) for Coaxial Line Microwave Plasma. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeeb, M.A.; Morgan, N.; Abouelsayed, A.; Amin, K.M.; Hassaballa, S. Electrical and Optical Characterization of Acetylene RF CCP for Synthesis of Different Forms of Hydrogenated Amorphous Carbon Films. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2019, 40, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. P. Raizer, M. N. Shneider, and N. A. Yatsenko, “Radio-Frequency capacitive discharges,” Radio-Frequency Capacitive Discharges, pp. 1–304, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Abbass, Q.; Ahmed, N.; Ahmed, R.; Baig, M.A. A Comparative Study of Calibration Free Methods for the Elemental Analysis by Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2016, 36, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, N.; Razzak, M.A.; Ukai, H.; Takamura, S.; Uesugi, Y. Validity of Electron Temperature Measurement by Using Boltzmann Plot Method in Radio Frequency Inductive Discharge in the Atmospheric Pressure Range. Plasma Fusion Res. 2006, 1, 028–028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Godyak, V.; Piejak, R.B.; Alexandrovich, B.M. Electron energy distribution function measurements and plasma parameters in inductively coupled argon plasma. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2002, 11, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Godyak, V. Electrical and plasma parameters of ICP with high coupling efficiency. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2011, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Kolobov, V.; Economou, D.J. The anomalous skin effect in gas discharge plasmas. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 1997, 6, R1–R17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godyak, V.A.; Kolobov, V.I. Effect of Collisionless Heating on Electron Energy Distribution in an Inductively Coupled Plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, M.I.; Fauchais, P.L.; Pfender, E. The Plasma State. 2016, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, A.Y.; Leys, C.; A Gonzalez, M.; Walsh, J.L. Electron density measurement in atmospheric pressure plasma jets: Stark broadening of hydrogenated and non-hydrogenated lines. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2015, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lari, E.S.; Askari, H.R.; Meftah, M.T.; Shariat, M. Calculation of electron density and temperature of plasmas by using new Stark broadening formula of helium lines. Phys. Plasmas 2019, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Wavelength (nm) | Ek (eV) | Aik (106 S-1) | gk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ArI | 696 | 13.328 | 6.40 | 3 |

| ArI | 706 | 13.302 | 3.80 | 5 |

| ArI | 727 | 13.328 | 1.83 | 3 |

| ArI | 738 | 13.302 | 8.50 | 5 |

| ArI | 750 | 13.479 | 45 | 1 |

| ArI | 751 | 13.273 | 40 | 1 |

| ArI | 763 | 13.172 | 24 | 5 |

| ArI | 771 | 13.153 | 5.20 | 3 |

| ArI | 772 | 13.328 | 11.7 | 3 |

| ArI | 794 | 13.283 | 18.6 | 3 |

| ArI | 800 | 13.172 | 49 | 5 |

| ArI | 801 | 13.095 | 9.30 | 5 |

| ArI | 810 | 13.153 | 25 | 3 |

| ArI | 811 | 13.076 | 33 | 7 |

| ArI | 826 | 13.328 | 15.3 | 3 |

| ArI | 840 | 13.302 | 22.3 | 5 |

| ArI | 842 | 13.095 | 21.5 | 5 |

| ArI | 851 | 13.283 | 13.9 | 3 |

| 2 L/min | 4 L/min | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power (W) |

(nm) |

(nm) | ne (1020 cm -1) |

Power (W) | (nm) | ne (1020 cm-1) |

|

| 440 | 1.431 | 1.126 | 2.231 | 440 | 1.440 | 1.138 | 2.778 |

| 550 | 1.406 | 1.096 | 2.211 | 550 | 1.358 | 1.037 | 2.421 |

| 660 | 1.415 | 1.108 | 2.295 | 660 | 1.461 | 1.162 | 2.661 |

| 770 | 1.402 | 1.091 | 2.335 | 770 | 1.372 | 1.055 | 2.432 |

| 880 | 1.377 | 1.061 | 2.338 | 880 | 1.363 | 1.044 | 2.423 |

| 990 | 1.436 | 1.133 | 2.571 | 990 | 1.419 | 1.113 | 2.508 |

| 1100 | 1.445 | 1.143 | 2.693 | 1100 | 1.346 | 1.023 | 2.384 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).