Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical approval

2.2. Animals

2.3. DNA extraction and Sequencing

2.4. Western blotting

2.5. Behavioral tests

2.5.1. Modified forced swim test (FST)

2.5.2. Tail suspension test (TST)

2.5.3. Elevated plus maze (EPM) test

2.5.4. Light Dark Box (LDB) test

2.5.5. Marble burying (MB) test

2.5.6. Passive avoidance test (PAT)

2.5.7. Open field (OF) test

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

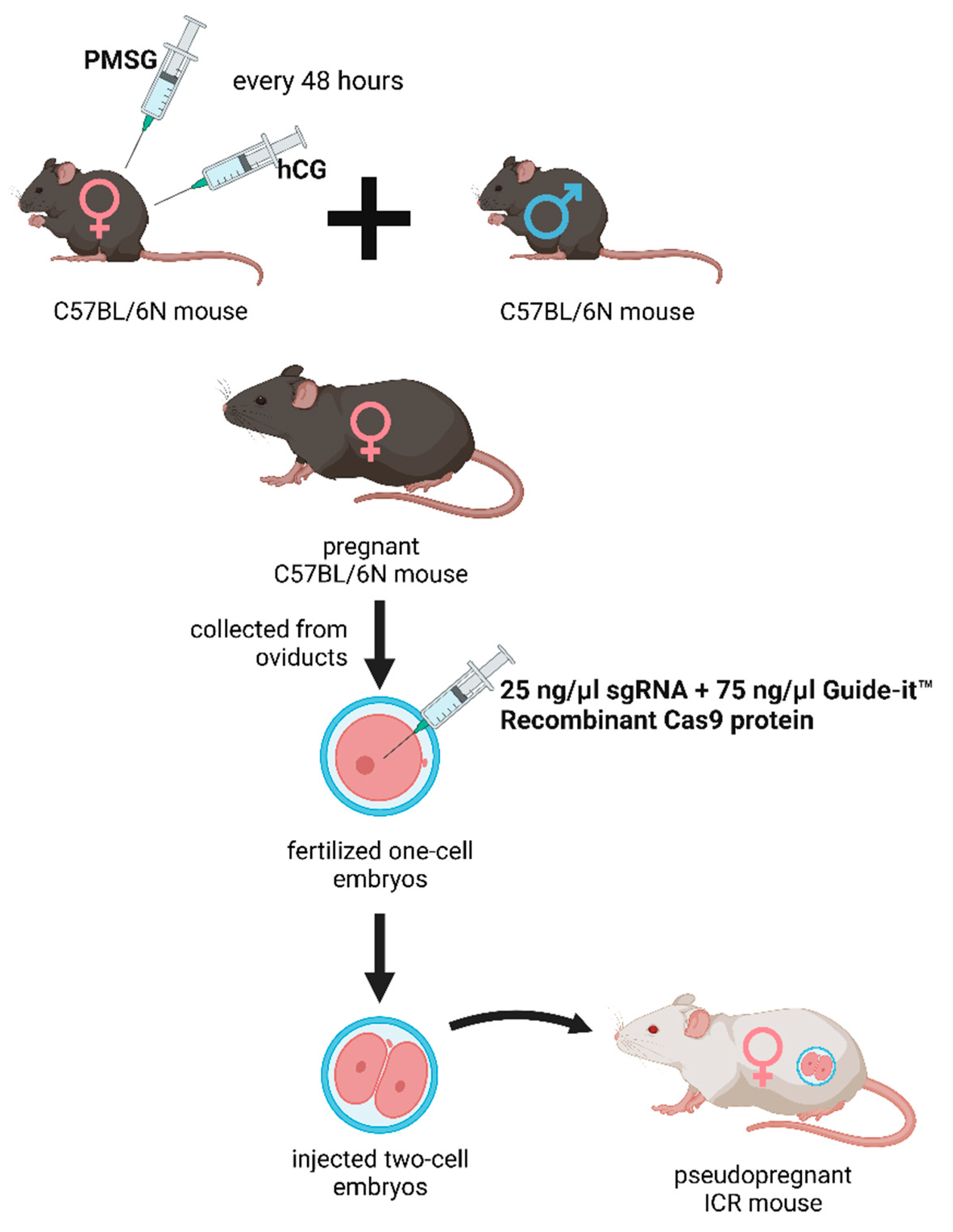

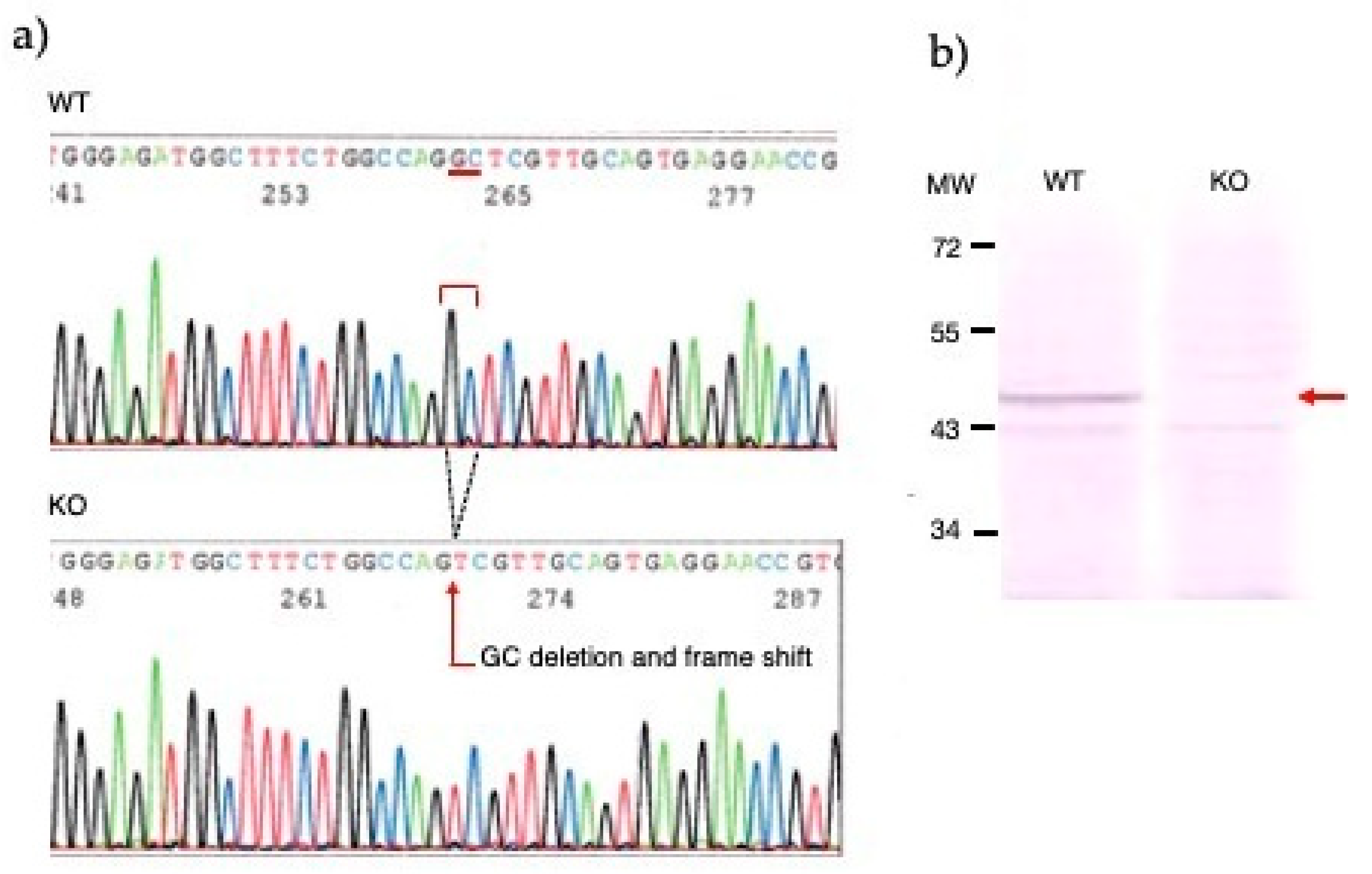

3.1. Generation of knockout mice by the CRIPR/Cas9 method

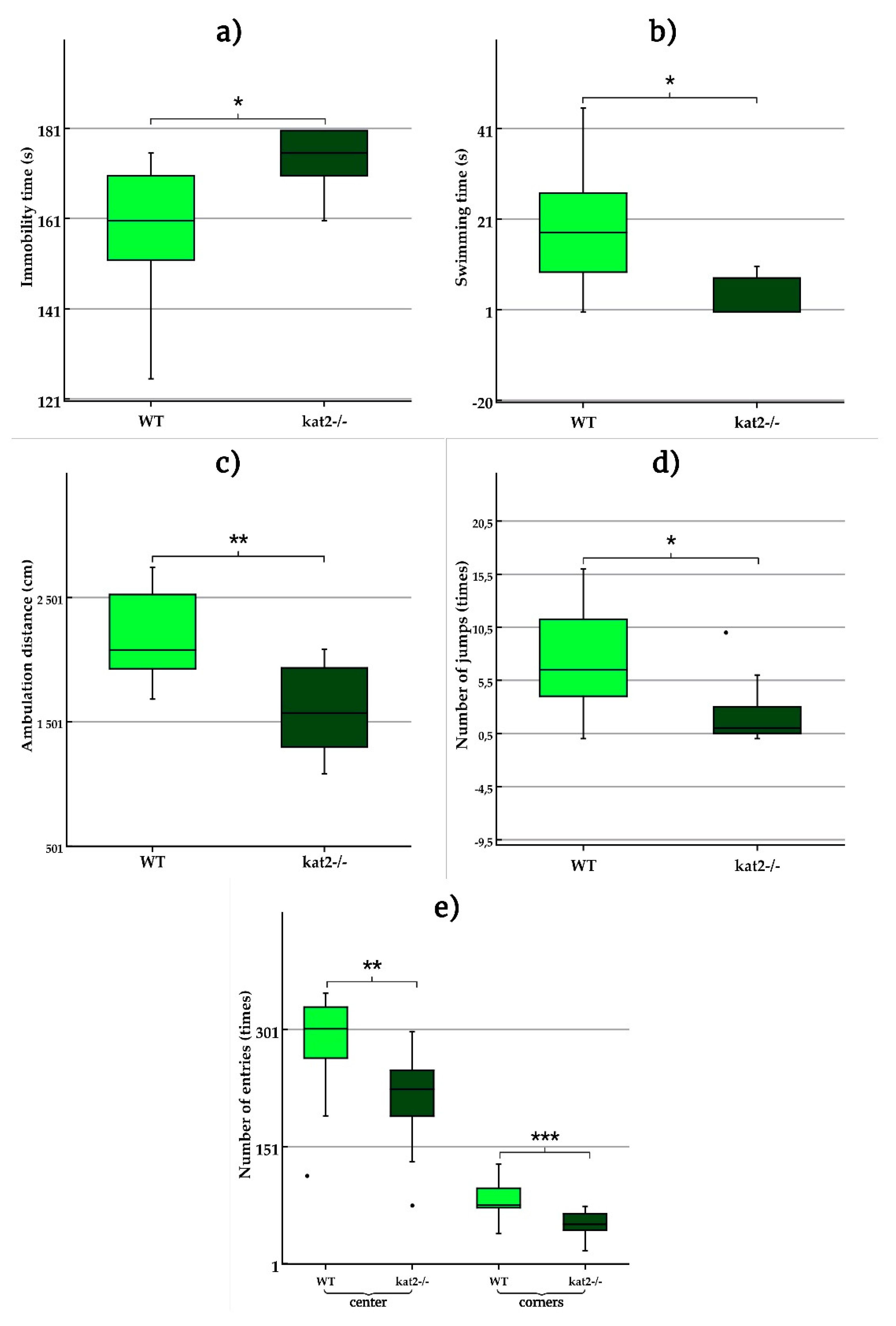

3.2. Depression-like behavior

3.2.1. Forced swim test (FST)

3.2.2. Tail suspension test (TST)

3.3. Aversive associative memory

3.4. Anxiety-like behavior

3.4.1. Elevated plus maze (EPM) test, Light Dark Box (LDB) test, and Marble burying (MB) test

3.4.2. Open field (OF) test

3.5. Exploratory behavior and motor function

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-HT | serotonin |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CBIR | cannabinoid 1 receptor |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| COMT | catechol-O-methyltransferase |

| EPM | elevated plus maze |

| FST | forced swim test |

| GABA | gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GAD | glutamic acid decarboxylase |

| hCG | human chorionic gonadotropin |

| KATII | α-aminoadipate aminotransferase/kynurenine aminotransferase II |

| KATs | kynurenine aminotransferases |

| KYN | kynurenine |

| KYNA | kynurenic acid |

| LDB | light dark box |

| MB | marble burying |

| MDD | major depressive disorder |

| OF | open field |

| PAT | passive avoidance test |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PMSG | pregnant mare serum gonadotropin |

| PTSD | posttraumatic stress disorder |

| SCZ | schizophrenia |

| sgRNA | single guide RNA |

| SSRI | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| Trp | tryptophan |

| TST | tail suspension test |

| WT | wild-type |

References

- Tyng, C.M.; Amin, H.U.; Saad, M.N.M.; Malik, A.S. The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, S.; Garofalo, S.; di Pellegrino, G.; Starita, F. Revaluing the Role of vmPFC in the Acquisition of Pavlovian Threat Conditioning in Humans. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 8491–8500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, S.; Harrison, B.J.; Falana, M.A. Does the human ventromedial prefrontal cortex support fear learning, fear extinction or both? A commentary on subregional contributions. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 784–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumsuzzman, D.M.; Choi, J.; Jin, Y.; Hong, Y. Neurocognitive effects of melatonin treatment in healthy adults and individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Battaglia, S.; Sciamanna, G.; Tortora, F.; Laricchiuta, D. Memories are not written in stone: Re-writing fear memories by means of non-invasive brain stimulation and optogenetic manipulations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasson, U.; Chen, J.; Honey, C.J. Hierarchical process memory: memory as an integral component of information processing. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 304–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clewett, D.; Sakaki, M.; Nielsen, S.; Petzinger, G.; Mather, M. Noradrenergic mechanisms of arousal’s bidirectional effects on episodic memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2017, 137, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, S.; Nazzi, C.; Thayer, J.F. Fear-induced bradycardia in mental disorders: Foundations, current advances, future perspectives. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 149, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Di Fazio, C.; Vicario, C.M.; Avenanti, A. Neuropharmacological Modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate, Noradrenaline and Endocannabinoid Receptors in Fear Extinction Learning: Synaptic Transmission and Plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.P.; Vanelzakker, M.B.; Shin, L.M. Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: a review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, D.G.; Pizzagalli, D.A. Mechanisms of Memory Disruption in Depression. Trends Neurosci. 2018, 41, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasebe, K.; Kendig, M.D.; Morris, M.J. Mechanisms Underlying the Cognitive and Behavioural Effects of Maternal Obesity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán-Vélez, E.; Feinstein, J.S.; Tranel, D. Feelings without memory in Alzheimer disease. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2014, 27, 117–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.; Marsh, L. Parkinson’s Disease: Cognitive Impairment. Focus (Am. Psychiatr. Publ). 2017, 15, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckee, A.C.; Daneshvar, D.H. The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 127, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Feng, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Fu, B.; Wang G, Lu, S. ; Zhong, N.; Hu, B. Emotional working memory in patients with major depressive disorder. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 1734–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, K.W. Post-traumatic stress disorder and declarative memory functioning: a review. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 346–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dere, E.; Pause, B.M.; Pietrowsky, R. Emotion and episodic memory in neuropsychiatric disorders. Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 215, 162–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Gray, J.A.; Roth, B.L. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009, 60, 355–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švob Štrac, D.; Pivac, N.; Mück-Šeler, D. The serotonergic system and cognitive function. Transl. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Cardellicchio, P.; Di Fazio, C.; Nazzi, C.; Fracasso, A.; Borgomaneri, S. Stopping in (e)motion: Reactive action inhibition when facing valence-independent emotional stimuli. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 998714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowen, P.; Sherwood, A.C. The role of serotonin in cognitive function: evidence from recent studies and implications for understanding depression. J. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 27, 575–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Cardellicchio, P.; Di Fazio, C.; Nazzi, C.; Fracasso, A.; Borgomaneri, S. The Influence of Vicarious Fear-Learning in “Infecting” Reactive Action Inhibition. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 946263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Thayer, J.F. Functional interplay between central and autonomic nervous systems in human fear conditioning. Trends Neurosci. 2022, 45, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, S.; Orsolini, S.; Borgomaneri, S.; Barbieri, R.; Diciotti, S.; di Pellegrino, G. Characterizing cardiac autonomic dynamics of fear learning in humans. Psychophysiology 2022, 59, e14122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gregorio, F.; La Porta, F.; Petrone, V.; Battaglia, S.; Orlandi, S.; Ippolito, G.; Romei, V.; Piperno, R.; Lullini, G. Accuracy of EEG Biomarkers in the Detection of Clinical Outcome in Disorders of Consciousness after Severe Acquired Brain Injury: Preliminary Results of a Pilot Study Using a Machine Learning Approach. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Battaglia, S.; Avenanti, A.; Pellegrino, G.D. Don’t Hurt Me No More: State-dependent Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for the treatment of specific phobia. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 286, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.; Godde, B.; Karim, A.A. The Link Between Creativity, Cognition, and Creative Drives and Underlying Neural Mechanisms. Front. Neural. Circuits. 2019, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Battaglia, S.; Garofalo, S.; Tortora, F.; Avenanti, A.; di Pellegrino, G. State-Dependent TMS over Prefrontal Cortex Disrupts Fear-Memory Reconsolidation and Prevents the Return of Fear. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 3672–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Garofalo, S.; di Pellegrino, G. Context-dependent extinction of threat memories: influences of healthy aging. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, P.R.; Vahid-Ansari, F.; Luckhart, C. Serotonin-prefrontal cortical circuitry in anxiety and depression phenotypes: pivotal role of pre- and post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptor expression. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewerton, T.D. Toward a unified theory of serotonin dysregulation in eating and related disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1995, 20, 561–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, A.; Wadhwa, R. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Teleanu, R.I.; Niculescu, A.G.; Roza, E.; Vladâcenco, O.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, D.M. Neurotransmitters-Key Factors in Neurological and Neurodegenerative Disorders of the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muneer, A. Kynurenine Pathway of Tryptophan Metabolism in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Pathophysiologic and Therapeutic Considerations. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Török, N.; Tóth, F.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Co-Players in Chronic Pain: Neuroinflammation and the Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic Pathway. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Le, A.; Hong, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, L.; Zang, W.; Jiang, C.; Wang, J.; Fan, X.; Wang, J. Tryptophan Metabolism in Central Nervous System Diseases: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 858–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyák, H.; Galla, Z.; Nánási, N.; Cseh, E.K.; Rajda, C.; Veres, G.; Spekker, E.; Szabó, Á.; Klivényi, P.; Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. The Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic System Is Suppressed in Cuprizone-Induced Model of Demyelination Simulating Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubková, B.; Valko-Rokytovská, M.; Čižmárová, B.; Zábavníková, M.; Mareková, M.; Birková, A. Tryptophan: Its Metabolism along the Kynurenine, Serotonin, and Indole Pathway in Malignant Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, A.; Tankiewicz-Kwedlo, A.; Krupa, A.; Pawlak, D. Role of Kynurenine Pathway in Oxidative Stress during Neurodegenerative Disorders. Cells 2021, 10, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, A.; Banfi, D.; Bistoletti, M.; Giaroni, C.; Baj, A. Tryptophan Metabolites Along the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: An Interkingdom Communication System Influencing the Gut in Health and Disease. Int. J. Tryptophan. Res. 2020, 13, 1178646920928984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spekker, E.; Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Neurogenic Inflammation: The Participant in Migraine and Recent Advancements in Translational Research. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Réus, G.Z.; Jansen, K.; Titus, S.; Carvalho, A.F.; Gabbay, V.; Quevedo, J. Kynurenine pathway dysfunction in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression: Evidences from animal and human studies. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 68, 316–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Tóth, F.; Polyák, H.; Szabó, Á.; Mándi, Y.; Vécsei, L. Immune Influencers in Action: Metabolites and Enzymes of the Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic Pathway. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Bohár, Z.; Martos, D.; Telegdy, G.; Vécsei, L. Antidepressant-like effects of kynurenic acid in a modified forced swim test. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martos, D.; Tuka, B.; Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L.; Telegdy, G. Memory Enhancement with Kynurenic Acid and Its Mechanisms in Neurotransmission. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/51166.

- Goh, D.L.; Patel, A.; Thomas, G.H.; Salomons, G.S.; Schor, D.S.; Jakobs, C.; Geraghty, M.T. Characterization of the human gene encoding alpha-aminoadipate aminotransferase (AADAT). Mol. Genet. Metab. 2002, 76, 172–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modoux, M.; Rolhion, N.; Mani, S.; Sokol, H. Tryptophan Metabolism as a Pharmacological Target. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 42, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palotai, M.; Telegdy, G.; Tanaka, M.; Bagosi, Z.; Jászberényi, M. Neuropeptide AF induces anxiety-like and antidepressant-like behavior in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 274, 264–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Telegdy, G. Involvement of adrenergic and serotonergic receptors in antidepressant-like effect of urocortin 3 in a modified forced swimming test in mice. Brain Res. Bull. 2008, 77, 301–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Schally, A.V.; Telegdy, G. Neurotransmission of the antidepressant-like effects of the growth hormone-releasing hormone antagonist MZ-4-71. Behav. Brain Res. 2012, 228, 388–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Telegdy, G. Neurotransmissions of antidepressant-like effects of neuromedin U-23 in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 259, 196–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telegdy, G.; Tanaka, M.; Schally, A.V. Effects of the growth hormone-releasing hormone (GH-RH) antagonist on brain functions in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 224, 155–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Csabafi, K.; Telegdy, G. Neurotransmissions of antidepressant-like effects of kisspeptin-13. Regul. Pept. 2013, 180, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rákosi, K.; Masaru, T.; Zarándia, M.; Telegdy, G.; Tóth, G.K. Short analogs and mimetics of human urocortin 3 display antidepressant effects in vivo. Peptides 2014, 62, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Editorial of Special Issue ‘Dissecting Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Diseases: Neurodegeneration and Neuroprotection’. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, K.N.; Nguyen, N.P.K.; Nguyen, L.T.H.; Shin, H.-M.; Yang, I.-J. Screening for Neuroprotective and Rapid Antidepressant-like Effects of 20 Essential Oils. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Integrating Armchair, Bench, and Bedside Research for Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychiatry: Editorial. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Kádár, K.; Tóth, G.; Telegdy, G. Antidepressant-like effects of urocortin 3 fragments. Brain Res. Bull. 2011, 84, 414–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telegdy, G.; Adamik, A.; Tanaka, M.; Schally, A.V. Effects of the LHRH antagonist Cetrorelix on affective and cognitive functions in rats. Regul. Pept. 2010, 159, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliellas, D.E.M.; Barros, M.P.; Vardaris, C.V.; Guariroba, M.; Poppe, S.C.; Martins, M.F.; Pereira, Á.A.F.; Bondan, E.F. Propentofylline Improves Thiol-Based Antioxidant Defenses and Limits Lipid Peroxidation following Gliotoxic Injury in the Rat Brainstem. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, M.; Imbriani, P.; Bonsi, P.; Martella, G.; Peppe, A. Beyond the Microbiota: Understanding the Role of the Enteric Nervous System in Parkinson’s Disease from Mice to Human. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garifulin, R.; Davleeva, M.; Izmailov, A.; Fadeev, F.; Markosyan, V.; Shevchenko, R.; Minyazeva, I.; Minekayev, T.; Lavrov, I.; Islamov, R. Evaluation of the Autologous Genetically Enriched Leucoconcentrate on the Lumbar Spinal Cord Morpho-Functional Recovery in a Mini Pig with Thoracic Spine Contusion Injury. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, C.R.d.S.; Tonin, M.C.C.; Buchaim, D.V.; Barraviera, B.; Ferreira Junior, R.S.; Santos, P.S.d.S.; Reis, C.H.B.; Pastori, C.M.; Pereira, E.d.S.B.M.; Nogueira, D.M.B.; Cini, M.A.; Rosa Junior, G.M.; Buchaim, R.L. Morphofunctional Improvement of the Facial Nerve and Muscles with Repair Using Heterologous Fibrin Biopolymer and Photobiomodulation. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalise, S.; Zannino, C.; Lucchino, V.; Lo Conte, M.; Scaramuzzino, L.; Cifelli, P.; D’Andrea, T.; Martinello, K.; Fucile, S.; Palma, E.; Gambardella, A.; Ruffolo, G.; Cuda, G.; Parrotta, E.I. Human iPSC Modeling of Genetic Febrile Seizure Reveals Aberrant Molecular and Physiological Features Underlying an Impaired Neuronal Activity. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datki, Z.; Sinka, R. Translational biomedicine-oriented exploratory research on bioactive rotifer-specific biopolymers. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2022, 31, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, K.-M.; Lee, M.-J.; Chung, H.-S.; Pak, J.-H.; Jeon, C.-J. The Organization of Somatostatin-Immunoreactive Cells in the Visual Cortex of the Gerbil. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.; Soga, T.; Ahemad, N.; Bhuvanendran, S.; Parhar, I. Kisspeptin-10 Rescues Cholinergic Differentiated SHSY-5Y Cells from α-Synuclein-Induced Toxicity In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Hasan, M.M.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Waliullah, A.S.M.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, C.; Oyama, S.; Mimi, M.A.; Tomochika, Y.; Nagashima, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Kahyo, T.; Ogawa, K.; Kaneda, D.; Yoshida, M.; Setou, M. UBL3 Interacts with Alpha-Synuclein in Cells and the Interaction Is Downregulated by the EGFR Pathway Inhibitor Osimertinib. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, A.; Cho, G.W.; Vijayakumar, K.A.; Moon, C.; Ang, M.J.; Kim, J.; Park, I.; Jang, C.H. Neuroprotective Effect of Valproic Acid on Salicylate-Induced Tinnitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibos, K.E.; Bodnár, É.; Bagosi, Z.; Bozsó, Z.; Tóth, G.; Szabó, G.; Csabafi, K. Kisspeptin-8 Induces Anxiety-Like Behavior and Hypolocomotion by Activating the HPA Axis and Increasing GABA Release in the Nucleus Accumbens in Rats. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliana, D.L.; Zhu, X.; Gomes, F.V.; Grace, A.A. Using animal models for the studies of schizophrenia and depression: The value of translational models for treatment and prevention. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 24, 16–935320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, S.; Kenyon, B.M.; Hamrah, P. Immunomodulatory Role of Neuropeptides in the Cornea. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirchandani-Duque, M.; Barbancho, M.A.; López-Salas, A.; Alvarez-Contino, J.E.; García-Casares, N.; Fuxe, K.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Narváez, M. Galanin and Neuropeptide Y Interaction Enhances Proliferation of Granule Precursor Cells and Expression of Neuroprotective Factors in the Rat Hippocampus with Consequent Augmented Spatial Memory. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taschereau-Dumouchel, V.; Michel, M.; Lau, H.; Hofmann, S.G.; LeDoux, J.E. Putting the “mental” back in “mental disorders”: a perspective from research on fear and anxiety. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, C.; Subedi, P.; Tian, X.; Lu, X.; Miriyala, S.; Panchatcharam, M.; Sun, H. Light Alcohol Consumption Promotes Early Neurogenesis Following Ischemic Stroke in Adult C57BL/6J Mice. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petković, A.; Chaudhury, D. Encore: Behavioural animal models of stress, depression and mood disorders. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 931964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahor, Z.; Nunes-Fonseca, C.; Thomson, L.D.; Sena, E.S.; Macleod, M.R. Improving our understanding of the in vivo modelling of psychotic disorders: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid. Based Preclin. Med. 2016, 3, e00022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasini, S.; Tidei, S.; Shkodra, A.; De Gregorio, D.; Cambiaghi, M.; Comai, S. Age-Related Effects of Exogenous Melatonin on Anxiety-like Behavior in C57/B6J Mice. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Spekker, E.; Szabó, Á.; Polyák, H.; Vécsei, L. Modelling the neurodevelopmental pathogenesis in neuropsychiatric disorders. Bioactive kynurenines and their analogues as neuroprotective agents-in celebration of 80th birthday of Professor Peter Riederer. J. Neural. Transm. (Vienna) 2022, 129, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolewska-Nowak, J.; Wachowska, K.; Nowak, A.; Orzechowska, A.; Szulc, A.; Płaza, O.; Gałecki, P. Exploring the Heart–Mind Connection: Unraveling the Shared Pathways between Depression and Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tug, E.; Fidan, I.; Bozdayi, G.; Yildirim, F.; Tunccan, O.G.; Lale, Z.; Akdogan, D. The relationship between the clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infections and ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression and polymorphisms. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, P.; Miranda, O.; Qi, X.; Kofler, J.; Sweet, R.A.; Wang, L. Unveiling the Enigma: Exploring Risk Factors and Mechanisms for Psychotic Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease through Electronic Medical Records with Deep Learning Models. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, F.; Medori, S.; Macrì, M. Move Your Body, Boost Your Brain: The Positive Impact of Physical Activity on Cognition across All Age Groups. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad, A.; Radwan, A.; Mohamed, N.A.; Mehanna, E.T.; Mostafa, Y.M.; El-Sayed, N.M.; Fattah, S.A. Rosiglitazone Mitigates Dexamethasone-Induced Depression in Mice via Modulating Brain Glucose Metabolism and AMPK/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statsenko, Y.; Habuza, T.; Smetanina, D.; Simiyu, G.L.; Meribout, S.; King, F.C.; Gelovani, J.G.; Das, K.M.; Gorkom, K.N.-V.; Zareba, K.; Almansoori, T.M.; Szolics, M.; Ismail, F.; Ljubisavljevic, M. Unraveling Lifelong Brain Morphometric Dynamics: A Protocol for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in Healthy Neurodevelopment and Ageing. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, J.; Tao, Q.; Niu, X.; Zhang, M.; Gao, X.; Yang, Z.; Yu, M.; Wang, W.; Han, S.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y. Meta-Analysis of Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Cocaine Addiction. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 927075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okanda Nyatega, C.; Qiang, L.; Jajere Adamu, M.; Bello Kawuwa, H. Altered striatal functional connectivity and structural dysconnectivity in individuals with bipolar disorder: A resting state magnetic resonance imaging study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1054380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Schmidt, A, Hassel, S.; Tanaka, M. Case Reports in Neuroimaging and Stimulation. Front. Psychiatry (submitted).

- Du, H.; Yang, B.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Xin, J.; Li, X. The non-linear correlation between the volume of cerebral white matter lesions and incidence of bipolar disorder: A secondary analysis of data from a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1149663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, R.; DeSouza, J.F.X.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, C.; Huang, P.; Wang, C. Differential responses from the left postcentral gyrus, right middle frontal gyrus, and precuneus to meal ingestion in patients with functional dyspepsia. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1184797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, M.J.; Qiang, L.; Nyatega, C.O.; Younis, A.; Kawuwa, H.B.; Jabire, A.H.; Saminu, S. Unraveling the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: insights from structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1188603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Wang, W.L.; Shieh, Y.H.; Peng, H.Y.; Ho, C.S.; Tsai, H.C. Case Report: Low-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation to Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex and Auditory Cortex in a Patient With Tinnitus and Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 847618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakia, H.; Iskandar, S. Case report: Depressive disorder with peripartum onset camouflages suspected intracranial tuberculoma. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 932635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyatega, C.O.; Qiang, L.; Adamu, M.J.; Kawuwa, H.B. Gray matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease: A voxel-based morphometry study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1027907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rymaszewska, J.; Wieczorek, T.; Fila-Witecka, K.; Smarzewska, K.; Weiser, A.; Piotrowski, P.; Tabakow, P. Various neuromodulation methods including Deep Brain Stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle combined with psychopharmacotherapy of treatment-resistant depression-Case report. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1068054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Xie, X.; Xie, J.; Tian, S.; Du, X.; Feng, H.; Zhang, H. Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease with depression as the first symptom: a case report with literature review. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1192562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.H.; Kim, S.H.; Han, C.; Jeong, H.G.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, J. Antidepressant-induced mania in panic disorder: a single-case study of clinical and functional connectivity characteristics. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1205126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Cao, Y.; Deng, G.; Fang, J.; Qiu, C. Transient splenial lesion syndrome in bipolar-II disorder: a case report highlighting reversible brain changes during hypomanic episodes. Front. Psychiatry. 2023, 14, 1219592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldema, J. Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation and Sex/Polypeptide Hormones in Reciprocal Interactions: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, L.; Tanaka, M.; Török, N.; Vécsei, L.; Taguchi, S. Crosstalk between Existential Phenomenological Psychotherapy and Neurological Sciences in Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gregorio, F.; Battaglia, S. Advances in EEG-based functional connectivity approaches to the study of the central nervous system in health and disease. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 32, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Diano, M.; Battaglia, S. Editorial: Insights into structural and functional organization of the brain: evidence from neuroimaging and non-invasive brain stimulation techniques. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1225755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakamata, Y.; Hori, H.; Mizukami, S.; Izawa, S.; Yoshida, F.; Moriguchi, Y.; Hanakawa, T.; Inoue, Y.; Tagaya, H. Blunted diurnal interleukin-6 rhythm is associated with amygdala emotional hyporeactivity and depression: a modulating role of gene-stressor interactions. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1196235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rassler, B.; Blinowska, K.; Kaminski, M.; Pfurtscheller, G. Analysis of Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia and Directed Information Flow between Brain and Body Indicate Different Management Strategies of fMRI-Related Anxiety. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliu, O. Efficacy, Tolerability, and Safety of Toludesvenlafaxine for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder—A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detke, M.J.; Rickels, M.; Lucki, I. Active behaviors in the rat forced swimming test differentially produced by serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1995, 121, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khisti, R.T.; Chopde, C.T.; Jain, S.P. Antidepressant-like effect of the neurosteroid 3alpha-hydroxy-5alpha-pregnan-20-one in mice forced swim test. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2000, 67, 137–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steru, L.; Chermat, R.; Thierry, B.; Simon, P. The tail suspension test: a new method for screening antidepressants in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1985, 85, 367–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; Mombereau, C.; Vassout, A. The tail suspension test as a model for assessing antidepressant activity: review of pharmacological and genetic studies in mice. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 571–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, R.G. The use of a plus-maze to measure anxiety in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1987, 92, 180–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, S.; Chopin, P.; File, SE.; Briley, M. Validation of open: closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1985, 14, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misslin, R.; Belzung, C.; Vogel, E. Behavioural validation of a light/dark choice procedure for testing anti-anxiety agents. Behav. Processes 1989, 18, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costall, B.; Coughlan, J.; Horovitz, Z.P.; Kelly, M.E.; Naylor, R.J.; Tomkins, D.M. The effects of ACE inhibitors captopril and SQ29,852 in rodent tests of cognition. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989, 33, 573–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaivi, E.S.; Martin, B.R. Neuropharmacological and physiological validation of a computer-controlled two-compartment black and white box for the assessment of anxiety. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1989, 13, 963–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekkamp, C.L.; Rijk, H.W.; Joly-Gelouin, D.; Lloyd, K.L. Major tranquillizers can be distinguished from minor tranquillizers on the basis of effects on marble burying and swim-induced grooming in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1986, 126, 223–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Poel, A.M. Ethological study of the behaviour of the albino rat in a passive-avoidance test. Acta Physiol. Pharmacol. Neerl. 1967, 14, 503–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.; Ballachey, E.L. A study of the rat’s behavior in a field: a contribution to method in comparative psychology. University of California Publications in Psychology 1932, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, T.D.; Dao, D.T.; Kovacsics, C.E. The Open Field Test. In: Gould, T. Mood and Anxiety Related Phenotypes in Mice. Neuromethods, vol 42. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, 2009. [CrossRef]

- ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/psychology/neurotransmitter (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Schwarz, M.J.; Ackenheil, M. The role of substance P in depression: therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2002, 4, 21–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Török, N.; Vécsei, L. Are 5-HT1 receptor agonists effective anti-migraine drugs? Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2021, 22, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindler, J.; Lim, C.K.; Weickert, C.S.; Boerrigter, D.; Galletly, C.; Liu, D.; Jacobs, K.R.; Balzan, R.; Bruggemann, J.; O’Donnell, M.; Lenroot, R.; Guillemin, G.J.; Weickert, T.W. Dysregulation of kynurenine metabolism is related to proinflammatory cytokines, attention, and prefrontal cortex volume in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 2860–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Cai, T.; Tagle, D.A.; Li, J. Structure, expression, and function of kynurenine aminotransferases in human and rodent brains. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 353–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Angkawidjaja, C.; Koga, Y.; Kanaya, S. Structural and mechanistic insights into the kynurenine aminotransferase-mediated excretion of kynurenic acid. J. Struct. Biol. 2014, 185, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucukkarapinar, M.; Yay-Pence, A.; Yildiz, Y.; Buyukkoruk, M.; Yaz-Aydin, G.; Deveci-Bulut, T.S.; Gulbahar, O.; Senol, E.; Candansayar, S. Psychological outcomes of COVID-19 survivors at sixth months after diagnose: the role of kynurenine pathway metabolites in depression, anxiety, and stress. J. Neural. Transm. (Vienna) 2022, 129, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Török, N.; Vécsei, L. Novel Pharmaceutical Approaches in Dementia. In: Riederer, P., Laux, G., Nagatsu, T., Le, W., Riederer, C. (eds) NeuroPsychopharmacotherapy. Springer, Cham. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Spekker, E.; Polyák, H.; Tóth, F.; Vécsei, L. Mitochondrial Impairment: A Common Motif in Neuropsychiatric Presentation? The Link to the Tryptophan–Kynurenine Metabolic System. Cells 2022, 11, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Bohár, Z.; Vécsei, L. Are Kynurenines Accomplices or Principal Villains in Dementia? Maintenance of Kynurenine Metabolism. Molecules 2020, 25, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Courtois, C.A. Complex PTSD and borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personal Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2021, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsy, B.; Kocsis, K.; Magyar, A.; Babiczky, Á.; Szabó, M.; Veres, J.M.; Hillier, D.; Ulbert, I.; Yizhar, O.; Mátyás, F. Associative and plastic thalamic signaling to the lateral amygdala controls fear behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberg, J.M.; Stewart, J.L.; Levin, R.L.; Miller, G.A.; Heller, W. Prefrontal Cortex, Emotion, and Approach/Withdrawal Motivation. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankland, P.W.; Josselyn, S.A.; Köhler, S. The neurobiological foundation of memory retrieval. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, A.A. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 524–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TenHouten, W. The Emotions of Hope: From Optimism to Sanguinity, from Pessimism to Despair. Am. Soc. 2023, 54, 76–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; McAdams, D.P. The Relation of Ego Integrity and Despair to Personality Traits and Mental Health. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Duan, T.T.; Tian, M.; Yuan, Q.; Tan, J.W.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Ding, Z.Y.; Cao, J.; Yang, Y.X.; Zhang, X.; Mao, R.R.; Richter-Levin, G.; Zhou, Q.X.; Xu, L. Despair-associated memory requires a slow-onset CA1 long-term potentiation with unique underlying mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, J. Despair and Hopelessness. Journal of the American Philosophical Association 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meerkerk-Aanen, P.J.; de Vroege, L.; Khasho, D.; Foruz, A.; van Asseldonk, J.T.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M. La belle indifférence revisited: a case report on progressive supranuclear palsy misdiagnosed as conversion disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 2057–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Depression: How effective are antidepressants? [Updated 2020 Jun 18]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK361016/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Raison, S.; Weissmann, D.; Rousset, C.; Pujol, J.F.; Descarries, L. Changes in steady-state levels of tryptophan hydroxylase protein in adult rat brain after neonatal 6-hydroxydopamine lesion. Neuroscience 1995, 67, 463–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, J.P.; Medvedev, I.O.; Caron, M.G. The 5-HT deficiency theory of depression: perspectives from a naturalistic 5-HT deficiency model, the tryptophan hydroxylase 2Arg439His knockin mouse. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 2444–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.J.; Wang, J.L.; Jing-Pan, Min-Liao. Tph2 Genetic Ablation Contributes to Senile Plaque Load and Astrogliosis in APP/PS1 Mice. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angoa-Pérez, M.; Kane, M.J.; Briggs, D.I.; Herrera-Mundo, N.; Sykes, C.E.; Francescutti, D.M.; Kuhn, D.M. Mice genetically depleted of brain serotonin do not display a depression-like behavioral phenotype. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 908–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbrini, G.; Hanswijk, S.I.; Brivio, P.; Middelman, A.; Bader, M.; Fumagalli, F.; Alenina, N.; Homberg, J.R.; Calabrese, F. Peripheral Serotonin Deficiency Affects Anxiety-like Behavior and the Molecular Response to an Acute Challenge in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemenhagen, K.C.; Gordon, J.A.; David, D.J.; Hen, R.; Gross, C.T. Increased fear response to contextual cues in mice lacking the 5-HT1A receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 101–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchekioua, Y.; Nebuka, M.; Sasamori, H.; Nishitani, N.; Sugiura, C.; Sato, M.; Yoshioka, M.; Ohmura, Y. Serotonin 5-HT2C receptor knockout in mice attenuates fear responses in contextual or cued but not compound context-cue fear conditioning. Trans. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellman, C.L.; Izquierdo, A.; Garrett, J.E.; Martin, K.P.; Carroll, J.; Millstein, R.; Lesch, K.P.; Murphy, D.L.; Holmes, A. Impaired stress-coping and fear extinction and abnormal corticolimbic morphology in serotonin transporter knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 684–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorgdrager, F.J.H.; Naudé, P.J.W.; Kema, I.P.; Nollen, E.A.; Deyn, P.P. Tryptophan Metabolism in Inflammaging: From Biomarker to Therapeutic Target. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint, A.M. Kynurenines: from the perspective of major psychiatric disorders. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 1375–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, M.R.; Di Fazio, C.; Battaglia, S. Activated Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic System in the Human Brain is Associated with Learned Fear. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorobogatov, K.; Autier, V.; Foiselle, M.; Richard, J.R.; Boukouaci, W.; Wu, C.L.; Raynal, S.; Carbonne, C.; Laukens, K.; Meysman, P. , et al. Kynurenine pathway abnormalities are state-specific but not diagnosis-specific in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2023, 27, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Xie, S.; He, Y.; Xu, M.; Qiao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, W. Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites as Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 9484217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszalek-Grabska, M.; Walczak, K.; Gawel, K.; Wicha-Komsta, K.; Wnorowska, S.; Wnorowski, A.; Turski, W.A. Kynurenine emerges from the shadows—Current knowledge on its fate and function. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 225, 107845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Di Prospero, N.A.; Sapko, M.T.; Cai, T.; Chen, A.; Melendez-Ferro, M.; Du, F.; Whetsell, W.O. Jr.; Guidetti, P.; Schwarcz, R.; Tagle, D.A. Biochemical and phenotypic abnormalities in kynurenine aminotransferase II-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 6919–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.C.; Elmer, G.I.; Bergeron, R.; Albuquerque, E.X.; Guidetti, P.; Wu, H.Q.; Schwarcz, R. Reduction of endogenous kynurenic acid formation enhances extracellular glutamate, hippocampal plasticity, and cognitive behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 1734–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbonnet, L.; Tighe, O.; Karayiorgou, M.; Gogos, J.A.; Waddington, J.L.; O’Tuathaigh, C.M. Physiological and behavioural responsivity to stress and anxiogenic stimuli in COMT-deficient mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2012, 228, 351–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kash, S.F.; Tecott, L.H.; Hodge, C.; Baekkeskov, S. Increased anxiety and altered responses to anxiolytics in mice deficient in the 65-kDa isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 1698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangha, S.; Narayanan, R.T.; Bergado-Acosta, J.R.; Stork, O.; Seidenbecher, T.; Pape, H.C. Deficiency of the 65 kDa isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase impairs extinction of cued but not contextual fear memory. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 15713–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.H.; Zhou, J.; Pan, H.Q.; Wang, X.Y.; Liu, W.Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; Yin, X.P.; Pan, B.X. δ Subunit-containing GABAA receptor prevents overgeneralization of fear in adult mice. Learn. Mem. 2017, 24, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sideris, A.; Piskoun, B.; Russo, L.; Norcini, M.; Blanck, T.; Recio-Pinto, E. Cannabinoid 1 receptor knockout mice display cold allodynia, but enhanced recovery from spared-nerve injury-induced mechanical hypersensitivity. Mol. Pain. 2016, 12, 1744806916649191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical SynthesisFull Access Highlights of Changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder American Psychiatric Association Division of Research Published Online:1 Jul 2013. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.11.3.358 (accessed on 20 July 2023). [CrossRef]

| Name of sgRNA | Sequence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M-KAT II-2 | GTTCCTCACTGCAACGAGCCguuuuagagcuagaaauagcaaguuaaaaaaggcuaguccguuaucaacuugaaaaaguggcacggacucggugcuuuu | ||

| Name of primer | Sequence | ||

| M-KAT II_1st_F | CCCTCTGTGGATGGACTTTG | ||

| M-KAT II_1st _R | TTGAAAGATGTGCCTCATGC | ||

| M-KAT II_2nd_F | GGATGGACTTTGTCCCTTCT | ||

| M-KAT II_2nd_R | ATGTGCCTCATGCTTGGCCC | ||

| Name of KAT gene | Transcript ID | CCDS | CCDS Nucleotide Sequence |

| Aadat-201 | ENSMUST00000079472.4 | CCDS22320 | 32-33 (2 nucleotide deletion) |

| Test type | Perspectives | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Modified forced swim test (FST) | Immobility time (s) | 0,022 |

| Swimming time (s) | 0,014 | |

| Climbing time (s) | 0,681 | |

| Tail suspension test (TST) | Immobility time (s) | 0,625 |

| Passive avoidance (PA) test | Time spent in the lit box on the training day (s) | 0,979 |

| Time spent in the lit box on the test day (s) | 0,822 | |

| Elevated plus maze (EPM) test | Time spent in the open arms (s) | 0,500 |

| Light-dark box (LDB) test | Time spent in the lit box (s) | 0,957 |

| Marble burying (MB) test | Number of immobile marbles (times) | 0,824 |

| Number of marbles that changed position (times) | 0,568 | |

| Number of 0-25% burried marbles (times) | 0,577 | |

| Number of 25-50% burried marbles (times) | 0,926 | |

| Number of 50-75% burried marbles (times) | 0,949 | |

| Number of 75-100% burried marbles (times) | 0,909 | |

| Open-field test (OFT) | Number of entries to the center zones (times) | 0,011 |

| Number of entries to the corner zones (times) | 0,001 | |

| Ambulation distance (cm) | 0,002 | |

| Number of jumps (times) | 0,034 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).