Submitted:

25 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preparation of Data for Analysis

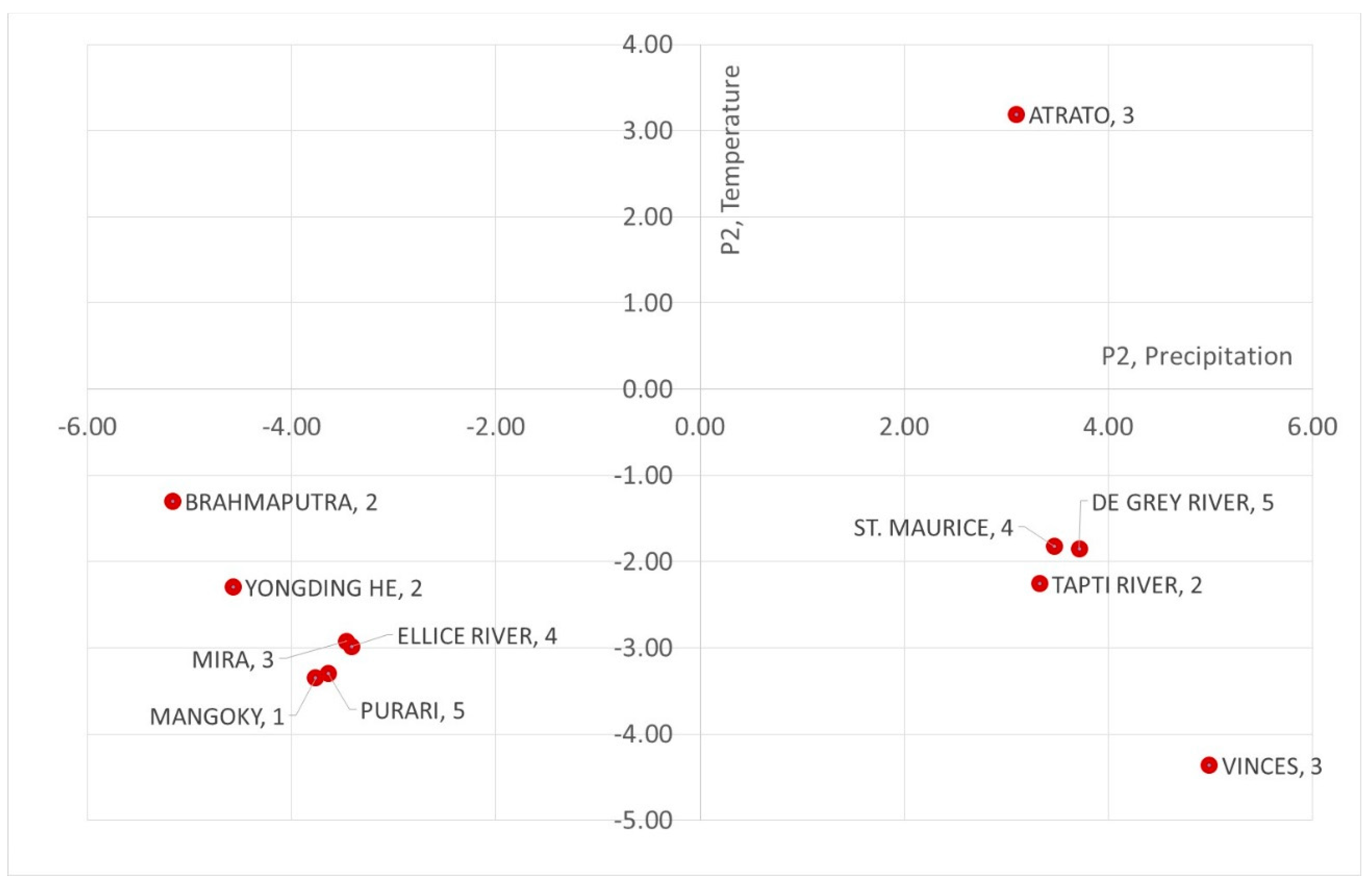

4. The polarisation of precipitation and temperature phenomena

5. The concept of polarisation measure

- The concentration ratio [85] determines the degree of concentration of values at one end of the distribution and is similar to the Gini coefficient. However, it should be noted that the Gini coefficient may be less useful in analysing asymmetric distributions, which means that other indicators such as the concentration ratio or Lorenz curve should be considered in such cases.

- The GMD (Gini Mean Difference) index [86] is an inequality measure used in statistical and econometric analysis to measure polarisation or inequality in a sample distribution. Unlike the Gini coefficient, which measures unevenness, the GMD index enables the analysis of unevenness in the distribution of any variable, such as income, age, weight, height, precipitation and temperature. The GMD index ranges from zero to one, where zero indicates complete evenness in the distribution and one indicates the concentration of all values in one class. The higher the GMD index value, the greater the unevenness in the variable distribution.

- The Lorenz indicator [78,82] is an inequality indicator in a distribution, which is based on the Lorenz curve. It is often used to measure income inequality but can also be used to measure inequality in other quantitative variables, including climate change studies. Higher values of the Lorenz curve indicate greater inequality in the occurrence of climate change effects such as droughts, floods, or sea level rises, meaning that some regions or social groups are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than others.

- The Atkinson index [77] is a measure of inequality in the distribution of quantitative variables, which is based on the idea of absolute deviations. It takes into account the differences between groups of values in the distribution; it is similar to the Gini index, but focuses more on average values than extreme values.

- Range relates to values calculated as max-min usually refering to the difference between the maximum and minimum values of a given variable in a specific period of time. In the case of assessing the polarisation of precipitation and temperature, max-min can be used as a measure of the amplitude of these variables in a given period.

6. Detecting a change point in the trend

7. Trend test

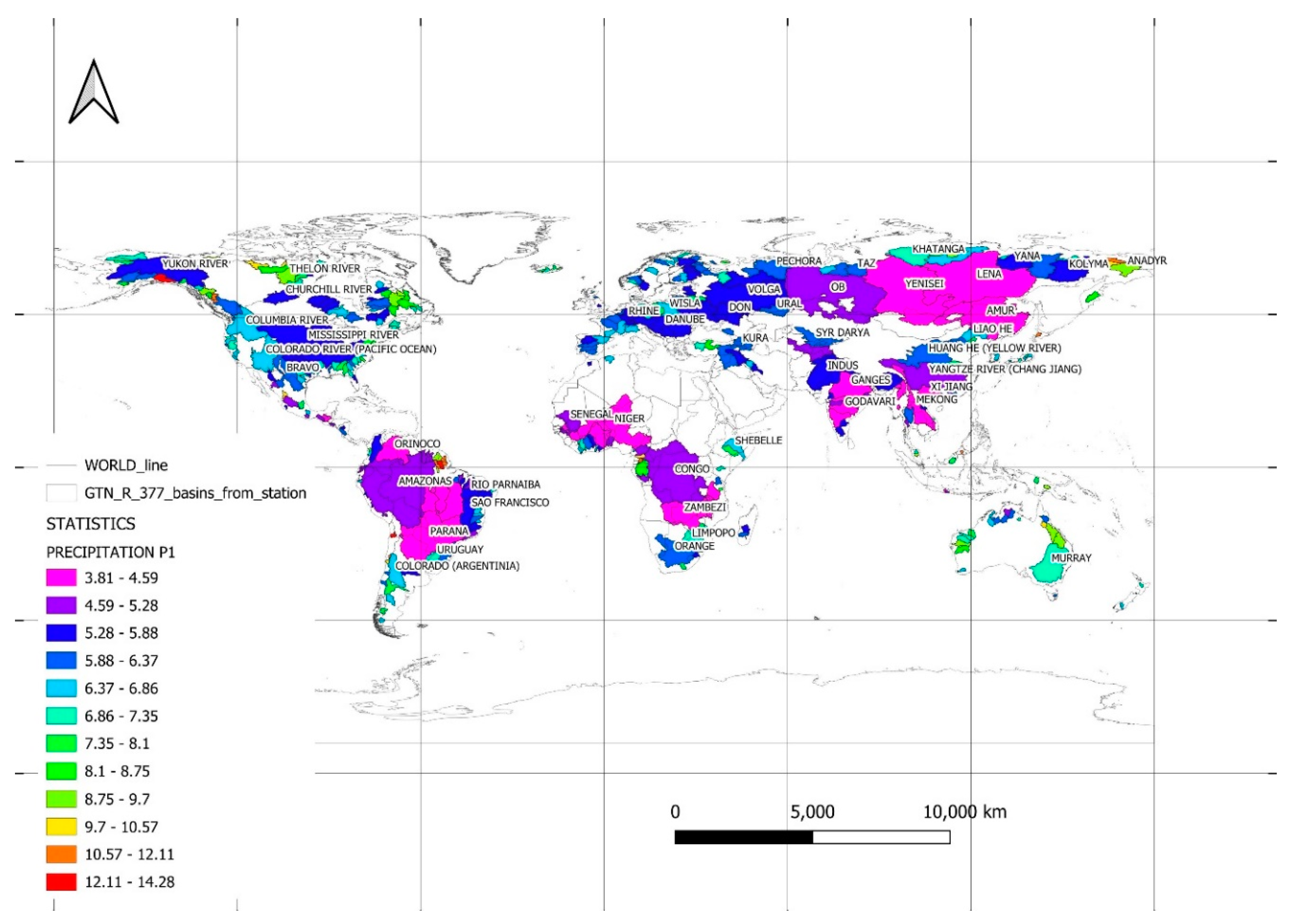

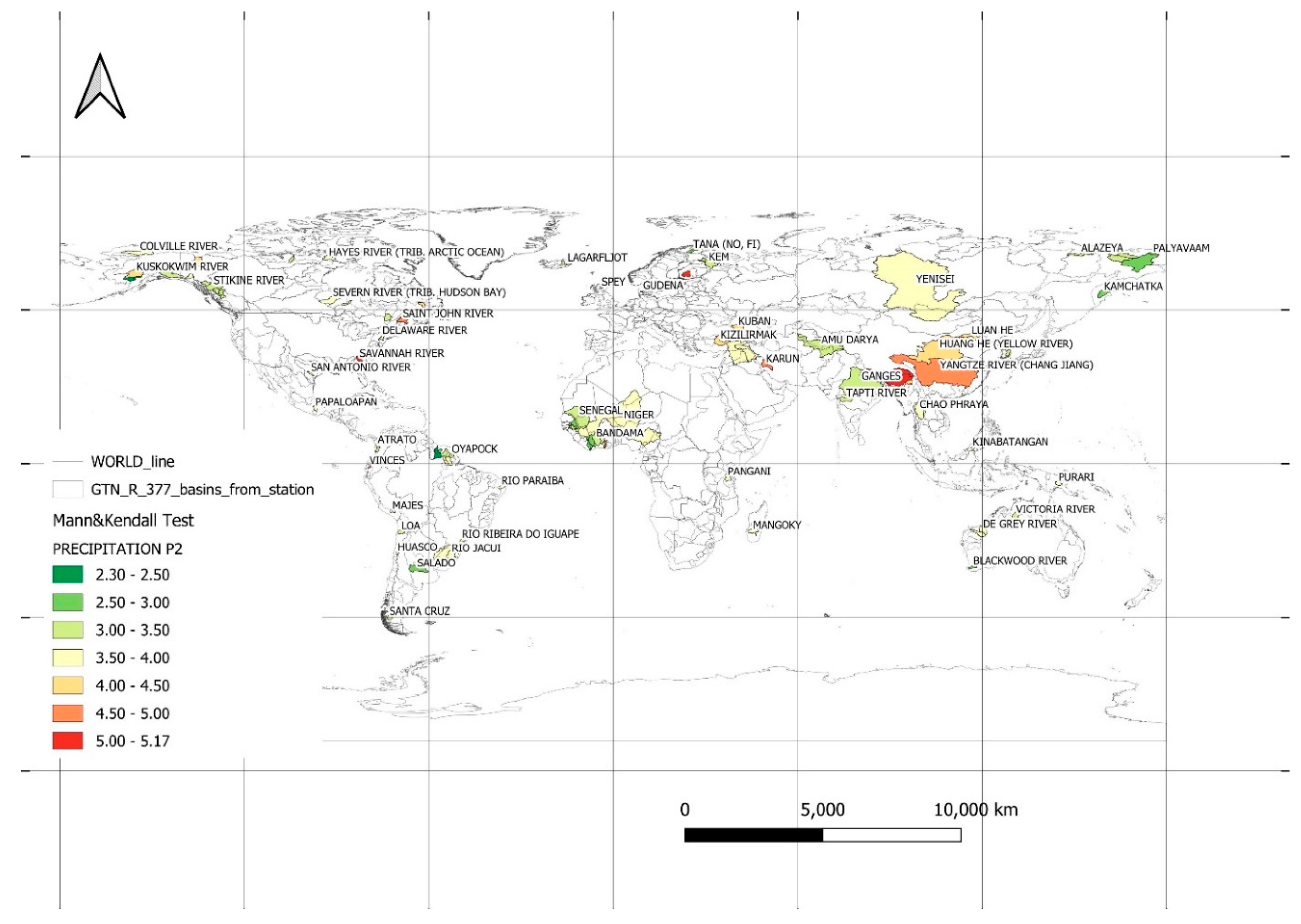

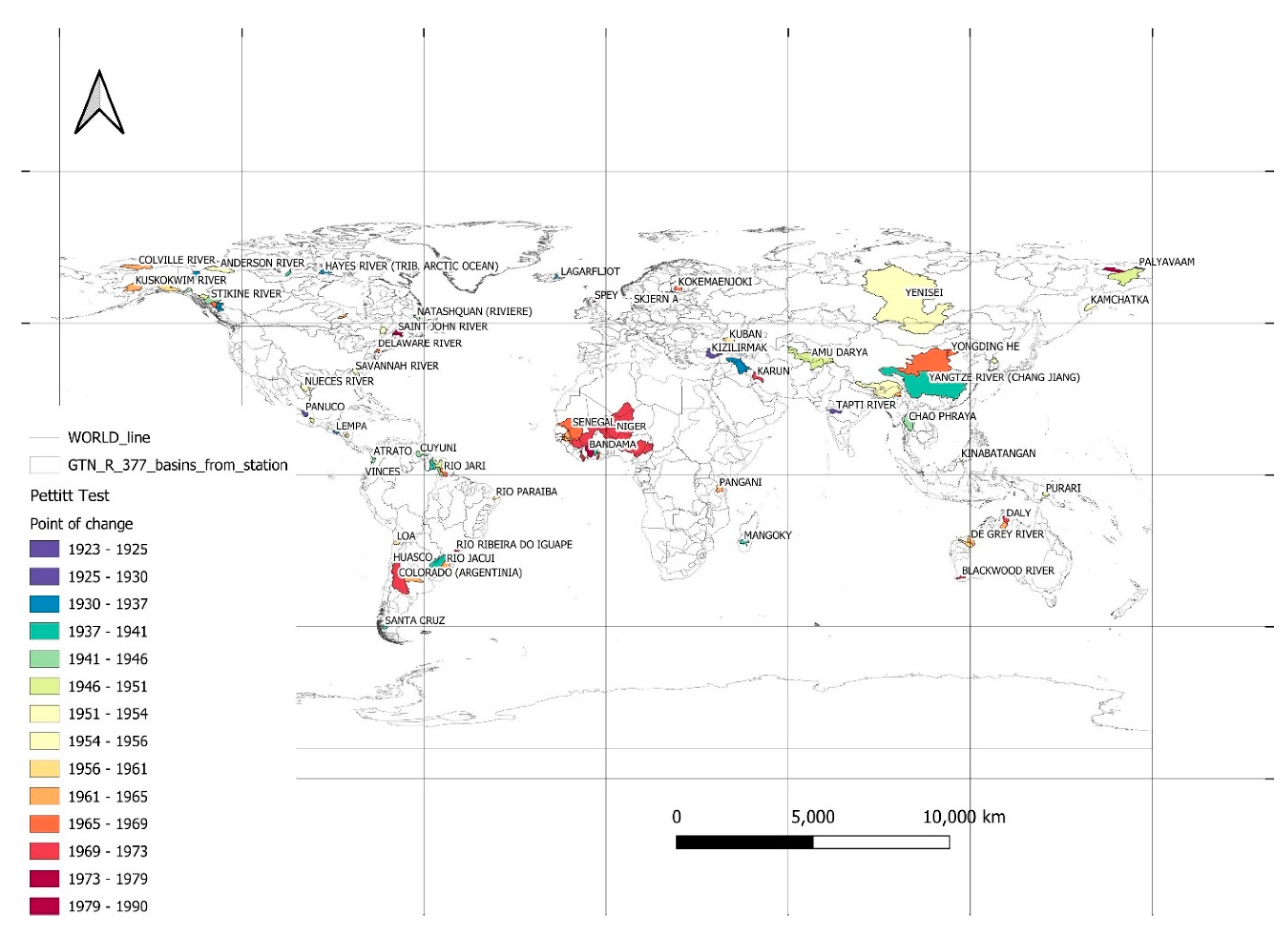

9. Results and Discussion

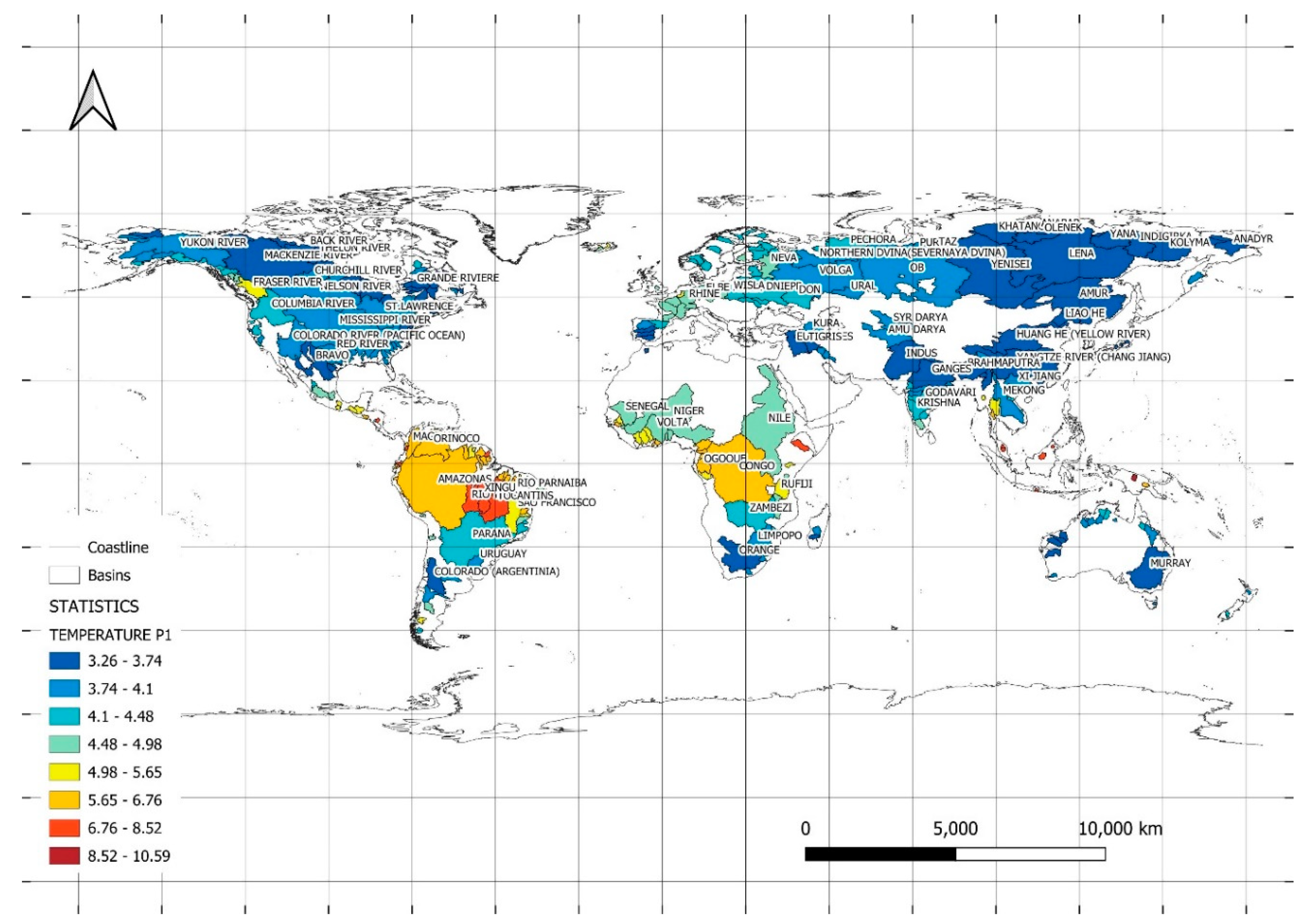

- the determination of the values of long-term monthly strings over a period of 110 years;

- the calculation of statistics relating to average values for each calendar month, the minimum value, the maximum value, the mean value and the standard deviation;

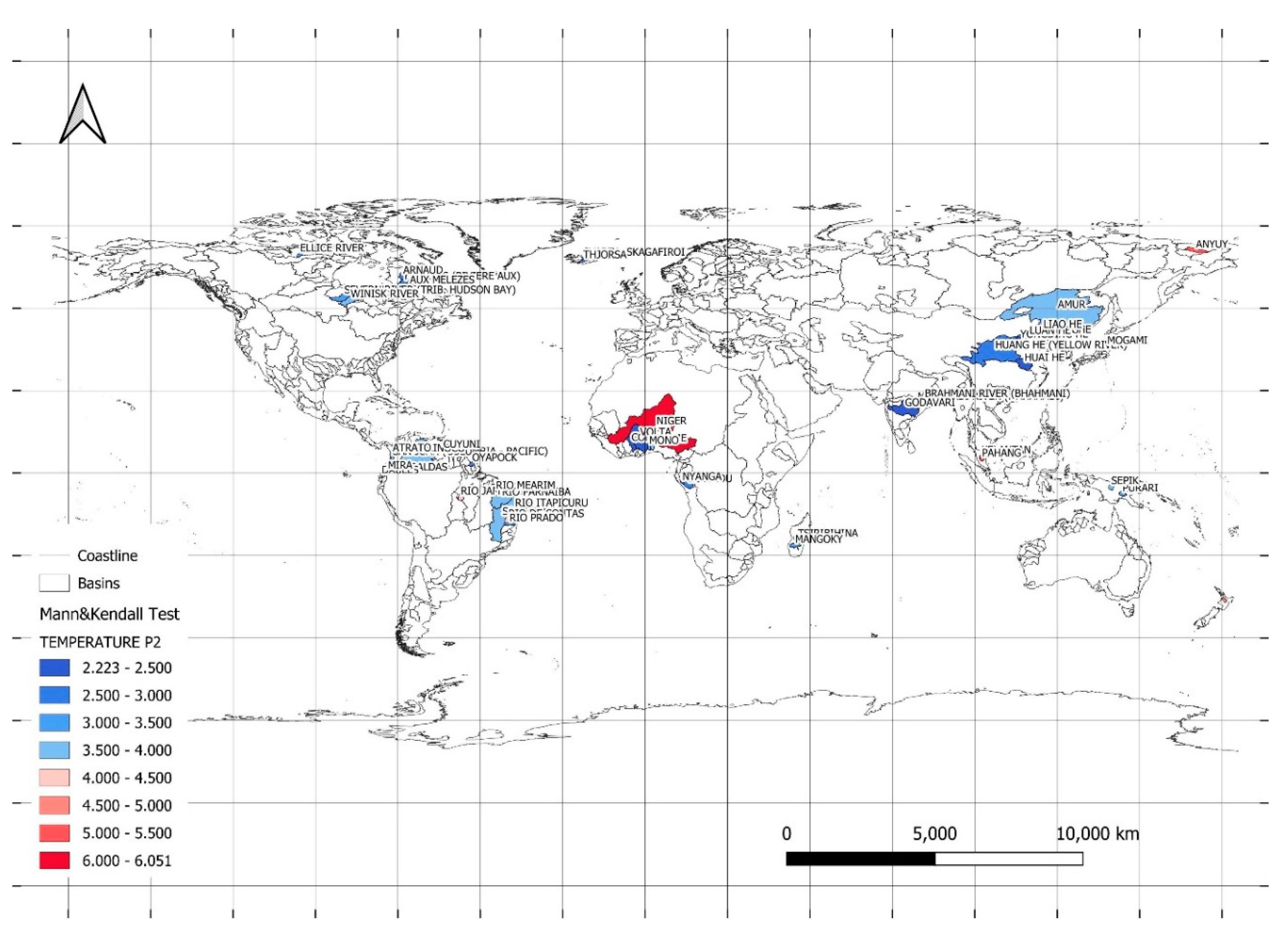

- the determination of the values of these trends with the Mann Kendall test (MKT) being used to evaluate the trend values;

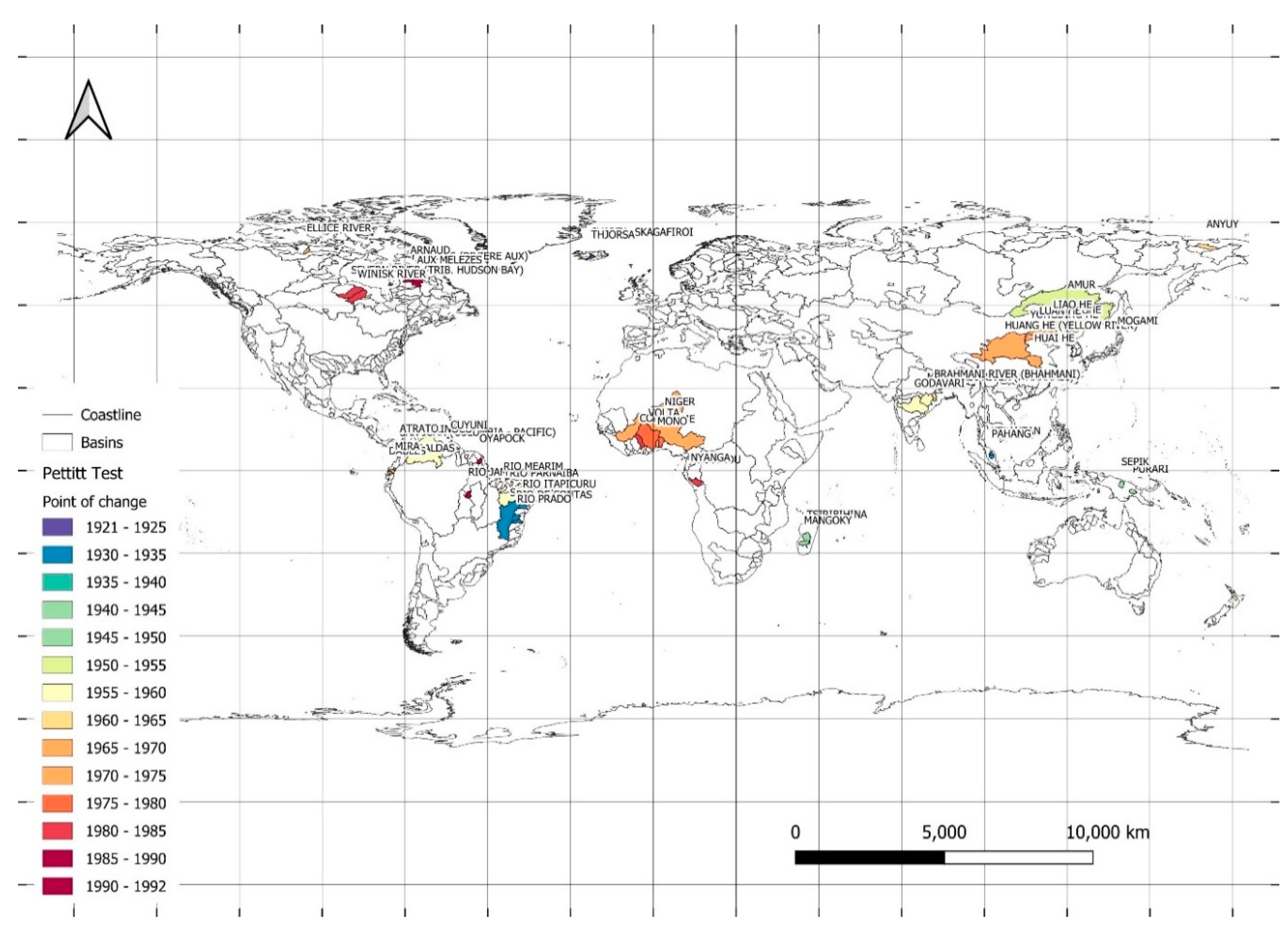

- the examination of whether the long-term series showed change points using the Pettitt test (PCPT);

- the examination of whether the sub-series (after the point of change up to 2010) has a significant trend in cases in which the long-term series showed points of change and to what extent this trend has changed.

- Asia: diversity of topography can affect air mass movements and precipitation formation, changes in atmospheric circulation such as monsoons, increasing urbanisation and infrastructure development can create the so-called 'heat island effect', which affects the microclimate, air pollution including particulate matter which affects condensation and cloud formation [36,104],

- South America: atmospheric circulation fluctuations, including those associated with El Niño and La Niña, topography of the region, including the Andes, deforestation, conversion of land for agriculture and urbanisation [32],

- Australia and Oceania: El Niño - La Niña cycle , changes in ocean circulation - variation in ocean surface temperature and atmospheric pressure between western and eastern areas of the Indian Ocean, deforestation, change in water use and air pollution, intensive agriculture and overexploitation of water resources [32,36].

9. Conclusions

- changes in atmospheric circulation: fluctuations in atmospheric circulation, such as changes in belt and monsoon patterns, can concentrate precipitation in certain regions, while other areas experience precipitation deficits [109],

- El Niño and La Niña phenomena: can lead to abrupt changes in ocean surface temperature, which affects rainfall patterns, areas that are normally wet can experience drought during El Niño, and dry areas can become flooded during La Niña [32],

- topographical changes: high mountain ranges can affect the movement of air masses and cloud formation, leading to more rainfall on one side of the mountain and droughts on the other, [32],

- urbanisation and land use changes: urban growth and land use changes can alter the microclimate and affect the distribution of precipitation in an area [32].

- changes in atmospheric circulation: may bring higher temperatures to tropical areas, while areas under the influence of lows may experience cooling [109],

- changes in greenhouse gases: increases in greenhouse gas concentrations can lead to an overall warming of the climate, but some areas may experience faster temperature increases than others [62],

- impact of urban areas: cities create so-called 'heat islands' where concrete and asphalt absorb and retain heat, which can lead to significant heating of urban areas [111].

- increased weather variability: polarisation of precipitation can lead to abrupt and unpredictable changes in weather patterns, which can make planning for agricultural and infrastructure activities difficult [41],

- risk of natural disasters: extremes of rainfall can increase the risk of natural disasters, such as floods in areas of increased rainfall or droughts in areas of decreased rainfall [112],

- impact on water availability: precipitation polarisation can lead to reduced water availability in drought-affected areas and increased risk of soil erosion during periods of intense rainfall [93],

- impact on ecosystems: extreme precipitation conditions can affect ecosystem structures and services, with potential implications for biodiversity and ecosystem products [113].

- human health risks: temperature extremes, both heat and cold, can pose a risk to human health, leading to heat- or cold-related diseases [112],

- effects on agriculture and food production: extreme temperatures can affect plant growth processes, leading to reduced yields and loss of quality of agricultural products [114],

- changes in species distribution: extreme temperatures can affect the distribution areas of different animal and plant species, which can disrupt the balance of ecosystems [115],

- changes in water levels: glacial melting and ocean warming associated with temperature polarisation can lead to rising sea and ocean levels [116].

- increased risk of natural disasters: the combination of extreme rainfall and temperatures can amplify the risk of floods, landslides and other natural disasters [106],

- impact on agri-food production: extreme precipitation and temperatures can negatively affect food production, which can lead to food security problems [112],

- changes in the landscape: the interaction of extreme rainfall and temperatures can lead to changes in the landscape, such as soil erosion and degradation of natural areas [112].

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. J. Romanowicz et al., “Climate Change Impact on Hydrological Extremes: Preliminary Results from the Polish-Norwegian Project,” Acta Geophys., vol. 64, no. 2, pp. 477–509, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Palaniswami and K. Muthiah, “Change point detection and trend analysis of rainfall and temperature series over the vellar river basin,” Polish J. Environ. Stud., vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 1673–1682, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Groves, D. Yates, and C. Tebaldi, “Developing and applying uncertain global climate change projections for regional water management planning,” Water Resour. Res., vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 1–16, 2008. [CrossRef]

- R. Katz, “Statistics of Extremes in Climatology and Hydrology,” Adv. Water Resour., vol. 25, pp. 1287–1304, 2002.

- R. W. Herschy, “The world’s maximum observed floods,” Flow Meas. Instrum., vol. 13, no. 5–6, pp. 231–235, 2002. [CrossRef]

- G. Blöschl et al., “Twenty-three unsolved problems in hydrology (UPH)–a community perspective,” Hydrol. Sci. J., vol. 64, no. 10, pp. 1141–1158, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Lewis and A. D. King, “Evolution of mean, variance and extremes in 21st century temperatures,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 15, no. July 2016, pp. 1–10, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Jaiswal, A. K. Lohani, and H. L. Tiwari, “Statistical Analysis for Change Detection and Trend Assessment in Climatological Parameters,” Environ. Process., vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 729–749, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Heim, “An overview of weather and climate extremes - Products and trends,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 10, pp. 1–9, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Sillmann et al., “Understanding, modeling and predicting weather and climate extremes: Challenges and opportunities,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 18, no. August, pp. 65–74, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Młyński, M. Cebulska, and A. Wałȩga, “Trends, variability, and seasonality of maximum annual daily precipitation in the Upper Vistula Basin, Poland,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1–14, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Młyński, A. Wałȩga, A. Petroselli, F. Tauro, and M. Cebulska, “Estimating maximum daily precipitation in the Upper Vistula Basin, Poland,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 10, no. 2, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Twardosz R., “Temporal variability of maximum monthly precipitation totals in the Polish Western Carpathian Mts during the period 1951 – 2005,” pp. 123–134, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ziernicka-Wojtaszek and J. Kopcińska, “Variation in atmospheric precipitation in Poland in the years 2001-2018,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 11, no. 8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Venegas-Cordero, Z. W. Kundzewicz, S. Jamro, and M. Piniewski, “Detection of trends in observed river floods in Poland,” J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud., vol. 41, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. W. Kundzewicz and M. Radziejewski, “Methodologies for trend detection,” IAHS-AISH Publ., no. 308, pp. 538–549, 2006.

- Z. W. Kundzewicz and A. Robson, “Detecting Trend and Other Changes in Hydrological Data,” World Clim. Program. - Water, no. May, p. 158, 2000, [Online]. Available: http://water.usgs.gov/osw/wcp-water/detecting-trend.pdf.

- T. Berezowski et al., “CPLFD-GDPT5: High-resolution gridded daily precipitation and temperature data set for two largest Polish river basins,” Earth Syst. Sci. Data, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 127–139, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Twaróg, “Characteristics of multi-annual variation of precipitation in areas particularly exposed to extreme phenomena. Part 1. the upper Vistula river basin,” E3S Web Conf., vol. 49, 2018.

- Y. Yu et al., “Climatic factors and human population changes in Eurasia between the Last Glacial Maximum and the early Holocene,” Glob. Planet. Change, vol. 221, p. 104054, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Chen, L. Zou, J. Xia, H. Liu, and F. Wang, “Decomposing the impacts of climate change and human activities on runoff changes in the Yangtze River Basin: Insights from regional differences and spatial correlations of multiple factors,” J. Hydrol., vol. 615, p. 128649, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Szolgayova, J. Parajka, G. Blöschl, and C. Bucher, “Long term variability of the Danube River flow and its relation to precipitation and air temperature,” J. Hydrol., vol. 519, no. PA, pp. 871–880, 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Pechlivanidis, J. Olsson, T. Bosshard, D. Sharma, and K. C. Sharma, “Multi-basin modelling of future hydrological fluxes in the Indian subcontinent,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 1–21, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Mudelsee, M. Börngen, G. Tetzlaff, and U. Grünewald, “Extreme floods in central Europe over the past 500 years: Role of cyclone pathway ‘Zugstrasse Vb,’” J. Geophys. Res. D Atmos., vol. 109, no. 23, pp. 1–21, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Vavrus, M. Notaro, and D. J. Lorenz, “Interpreting climate model projections of extreme weather events,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 10, pp. 10–28, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Angélil et al., “Comparing regional precipitation and temperature extremes in climate model and reanalysis products,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 13, pp. 35–43, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Michaelides, V. Levizzani, E. Anagnostou, P. Bauer, T. Kasparis, and J. E. Lane, “Precipitation: Measurement, remote sensing, climatology and modeling,” Atmos. Res., vol. 94, no. 4, pp. 512–533, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. Das, R. Bhattacharjee, A. Choubey, A. Ohri, S. B. Dwivedi, and S. Gaur, “Time series analysis of automated surface water extraction and thermal pattern variation over the Betwa river, India,” Adv. Sp. Res., vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 1761–1788, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Reinking, “An approach to remote sensing and numerical modeling of orographic clouds and precipitation for climatic water resources assessment,” Atmos. Res., vol. 35, no. 2–4, pp. 349–367, Jan. 1995. [CrossRef]

- C. López-Bermeo, R. D. Montoya, F. J. Caro-Lopera, and J. A. Díaz-García, “Validation of the accuracy of the CHIRPS precipitation dataset at representing climate variability in a tropical mountainous region of South America,” Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C, vol. 127, p. 103184, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. J. M. Knoben, R. A. Woods, and J. E. Freer, “Global bimodal precipitation seasonality: A systematic overview,” Int. J. Climatol., vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 558–567, 2019. [CrossRef]

- WMO, Guide to Climatological Practices 2018 edition, no. WMO-No. 100. 2018.

- S. M. Ross, Introduction to Probability and Statistics, no. 5. Academic Press is an imprint ofElsevier, 2014.

- Z. HAO, “APPLICATION OF ENTROPY THEORY IN HYDROLOGIC ANALYSIS AND SIMULATION,” 2016.

- C. Rica, “TROPICAL METEOROLOGY RESEARCH PROGRAMME (TMRP) COMMISSION FOR ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES (CAS),” Int. Organ., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 241–243, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Becker et al., “A description of the global land-surface precipitation data products of the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre with sample applications including centennial (trend) analysis from 1901-present,” Earth Syst. Sci. Data, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 71–99, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Gómez, J. D. Etchevers, A. I. Monterroso, C. Gay, J. Campo, and M. Martínez, “Spatial estimation of mean temperature and precipitation in areas of scarce meteorological information,” Atmosfera, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 35–56, 2008.

- D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, M. F. Wehner, and L. Sun, “Detection and attribution of climate extremes in the observed record,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 11, pp. 17–27, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Guimares Nobre, B. Jongman, J. Aerts, and P. J. Ward, “The role of climate variability in extreme floods in Europe,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 12, no. 8, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Petrow and B. Merz, “Trends in flood magnitude, frequency and seasonality in Germany in the period 1951–2002,” J. Hydrol., vol. 371, no. 1–4, pp. 129–141, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Singh, A. Gupta, and M. Singh, “Hydrological inferences from watershed analysis for water resource management using remote sensing and GIS techniques,” Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Sp. Sci., vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 111–121, 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, L. A. Vincent, W. D. Hogg, and A. Niitsoo, “Temperature and precipitation trends in Canada during the 20th century,” Atmos. - Ocean, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 395–429, 2000. [CrossRef]

- N. N. Karmeshu Supervisor Frederick Scatena, “Trend Detection in Annual Temperature & Precipitation using the Mann Kendall Test – A Case Study to Assess Climate Change on Select States in the Northeastern United States,” Mausam, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 1–6, 2015, [Online]. Available: http://repository.upenn.edu/mes_capstones/47.

- R. Dankers and R. Hiederer, “Extreme Temperatures and Precipitation in Europe: Analysis of a High-Resolution Climate Change Scenario,” JRC Sci. Tech. Reports, p. 82, 2008.

- R. W. Katz and M. B. Parlange, “Overdispersion phenomenon in stochastic modeling of precipitation,” J. Clim., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 591–601, 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. Sen Roy and R. C. Balling, “Trends in extreme daily precipitation indices in India,” Int. J. Climatol., vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 457–466, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Colmet-Daage et al., “Evaluation of uncertainties in mean and extreme precipitation under climate change for northwestern Mediterranean watersheds from high-resolution Med and Euro-CORDEX ensembles,” Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 673–687, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Y. Lenny Bernstein, Peter Bosch, Osvaldo Canziani, Zhenlin Chen, Renate Christ, Ogunlade Davidson, William Hare, Saleemul Huq, David Karoly, Vladimir Kattsov, Zbigniew Kundzewicz, Jian Liu, Ulrike Lohmann, Martin Manning, Taroh Matsuno, Bettina Menne, Bert M, “Climate Change 2007 : An Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,” Change, vol. 446, no. November, pp. 12–17, 2007, [Online]. Available: http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/syr/ar4_syr.pdf.

- J. Chapman, “A nonparametric approach to detecting changes in variance in locally stationary time series,” no. April 2019, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. H. and A. J. C. Philp K. Thornton, Pplly J. Ericksen, “Climate variability and vulnerability to climate change : a review,” pp. 3313–3328, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Swanson and A. A. Tsonis, “Has the climate recently shifted ?,” vol. 36, no. January, pp. 2–5, 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Balhane, F. Driouech, O. Chafki, R. Manzanas, A. Chehbouni, and W. Moufouma-Okia, “Changes in mean and extreme temperature and precipitation events from different weighted multi-model ensembles over the northern half of Morocco,” Clim. Dyn., vol. 58, no. 1–2, pp. 389–404, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Mesbahzadeh, M. M. Miglietta, M. Mirakbari, F. Soleimani Sardoo, and M. Abdolhoseini, “Joint Modeling of Precipitation and Temperature Using Copula Theory for Current and Future Prediction under Climate Change Scenarios in Arid Lands (Case Study, Kerman Province, Iran),” Adv. Meteorol., vol. 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Gerten, S. Rost, W. von Bloh, and W. Lucht, “Causes of change in 20th century global river discharge,” Geophys. Res. Lett., vol. 35, no. 20, pp. 1–5, 2008. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Walling, “Human impact on land–ocean sediment transfer by the world’s rivers,” Geomorphology, vol. 79, no. 3–4, pp. 192–216, Sep. 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Hunter, A. H. Clites, K. B. Campbell, and A. D. Gronewold, “Development and application of a North American Great Lakes hydrometeorological database — Part I: Precipitation, evaporation, runoff, and air temperature,” J. Great Lakes Res., vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 65–77, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chai et al., “Homogenization and polarization of the seasonal water discharge of global rivers in response to climatic and anthropogenic effects,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 709, p. 136062, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, Y. Shi, A. A. Argiriou, P. Ioannidis, A. Mamara, and Z. Yan, “A Comparative Analysis of Changes in Temperature and Precipitation Extremes since 1960 between China and Greece,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Jahn, “Economics of extreme weather events: Terminology and regional impact models,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 10, pp. 29–39, 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang et al., “Indices for monitoring changes in extremes based on daily temperature and precipitation data,” Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang., vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 851–870, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Allan and B. J. Soden, “Atmospheric warming and the amplification of precipitation extremes,” Science (80-. )., vol. 321, no. 5895, pp. 1481–1484, 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Christensen et al., “Climate phenomena and their relevance for future regional climate change,” Clim. Chang. 2013 Phys. Sci. Basis Work. Gr. I Contrib. to Fifth Assess. Rep. Intergov. Panel Clim. Chang., vol. 9781107057, pp. 1217–1308, 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. Rudolf, C. Beck, J. Grieser, and U. Schneider, “Global Precipitation Analysis Products of the GPCC,” Internet Publication, pp. 1–8, 2005, [Online]. Available: ftp://ftp-anon.dwd.de/pub/data/gpcc/PDF/GPCC_intro_products_2008.pdf.

- T. C. P. and R. S. Vose, “An overview of the global historical climatology network-daily database,” Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., vol. 78, no. 12, pp. 897–910, 1997. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Donat et al., “Updated analyses of temperature and precipitation extreme indices since the beginning of the twentieth century: The HadEX2 dataset,” J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., vol. 118, no. 5, pp. 2098–2118, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Persson et al., “No polarization-expected values of climate change impacts among European forest professionals and scientists,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 7, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Arheimer et al., “Global catchment modelling using World-Wide HYPE (WWH), open data, and stepwise parameter estimation,” Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 535–559, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. R. Iverson and D. McKenzie, “Tree-species range shifts in a changing climate: Detecting, modeling, assisting,” Landsc. Ecol., vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 879–889, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Franklin, “Mapping Species Distributions: Spatial Inference and Prediction,” Oryx, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 615–615, 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. Viner, M. Ekstrom, M. Hulbert, N. K. Warner, A. Wreford, and Z. Zommers, “Understanding the dynamic nature of risk in climate change assessments—A new starting point for discussion,” Atmos. Sci. Lett., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 1–8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Rosenzweig, C., Parry, “Potential impact of climate change on world food supply,” Nature, vol. 367, pp. 133–138, 1992. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Smith, R. W. Reynolds, T. C. Peterson, and J. Lawrimore, “Improvements to NOAA’s historical merged land-ocean surface temperature analysis (1880-2006),” J. Clim., vol. 21, no. 10, pp. 2283–2296, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Kosanic, K. Anderson, S. Harrison, T. Turkington, and J. Bennie, “Changes in the geographical distribution of plant species and climatic variables on the west cornwall peninsula (south west UK),” PLoS One, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 1–18, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen and S. Guo, Copulas and its application in hydrology and water resources. 2019.

- W. Hou, P. Yan, G. Feng, and D. Zuo, “A 3D Copula Method for the Impact and Risk Assessment of Drought Disaster and an Example Application,” Front. Phys., vol. 9, no. April, pp. 1–14, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Santos-Gómez, J. S. Fontalvo-García, and J. D. Giraldo Osorio, “Validating the University of Delaware’s precipitation and temperature database for northern South America,” Dyna, vol. 82, no. 194, pp. 86–95, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Amiel and F. Cowell, Thinking about Inequality, no. December 1999. 1999.

- M. O. Lorenz, “Methods of Measuring the Concentration of Wealth,” Publ. Am. Stat. Assoc., vol. 9, no. 70, pp. 209–219, 1905, [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2276207.

- M. G. and F. V. F. Francesco Nicolli, “Inequality and Climate Change: Two Problems, One Solution,” no. 2022, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep44832.

- M. Mccright and R. E. Dunlap, “The Politicization Of Climate Change And Polarization In The American Public’s Views Of Global Warming, 2001-2010,” Sociol. Q., vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 155–194, 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Ogwang, “Calculating a standard error for the Gini coefficient: Some further results: Reply,” Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat., vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 435–437, 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. Damgaard and J. Weiner, “Describing Inequality in Plant Size or Fecundity,” Ecology, vol. 81, no. 4, p. 1139, 2000. [CrossRef]

- T. Panek, “Polaryzacja ekonomiczna w Polsce,” Wiadomości Stat., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 41–62, 2017.

- T. Sitthiyot and K. Holasut, “A simple method for measuring inequality,” Palgrave Commun., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P.-M. Samson, Concentration of measure principle and entropy-inequalities. 2017.

- S. Yitzhaki, “Gini ’ s Mean Difference : A Superior Measure of Variability for Non-Normal Gini ’ s Mean difference : a superior measure of variability for non-normal distributions,” no. November, 2016.

- P. F. Pedro Conceição, “Young Person’s Guide to the Theil Index: Suggesting Intuitive Interpretations and Exploring Analytical Applications,” World, pp. 1–54, 2000, [Online]. Available: https://hal.science/hal-01365314.

- T. A. Buishand, “Some methods for testing the homogeneity of rainfall records,” J. Hydrol., vol. 58, no. 1–2, pp. 11–27, Aug. 1982. [CrossRef]

- K. Gupta, Jie Chen, “Parametric Statistical Change Point Analysis,” Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 6(11), 951–952., pp. 2013–2015, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Radziejewski, A. Bardossy, and Z. W. Kundzewicz, “Detection of change in river flow using phase randomization,” Hydrol. Sci. J., vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 547–558, 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. Salarijazi, “Trend and change-point detection for the annual stream-flow series of the Karun River at the Ahvaz hydrometric station,” African J. Agric. Reseearch, vol. 7, no. 32, pp. 4540–4552, 2012. [CrossRef]

- N. Pettitt, “A Non-Parametric Approach to the Change-Point Problem,” J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C (Applied Stat., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 126–135, Apr. 1979. [CrossRef]

- G. Verstraeten, J. Poesen, G. Demarée, and C. Salles, “Long-term (105 years) variability in rain erosivity as derived from 10-min rainfall depth data for Ukkel (Brussels, Belgium): Implications for assessing soil erosion rates,” J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., vol. 111, no. 22, pp. 1–11, 2006. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Conte, D. M. Bayer, and F. M. Bayer, “Bootstrap Pettitt test for detecting change points in hydroclimatological data: case study of Itaipu Hydroelectric Plant, Brazil,” Hydrol. Sci. J., vol. 64, no. 11, pp. 1312–1326, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Mann, “Nonparametric Tests Against Trend,” Econometrica, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 245–259, Apr. 1945. [CrossRef]

- S. Yue, P. Pilon, B. Phinney, and G. Cavadias, “The influence of autocorrelation on the ability to detect trend in hydrological series,” Hydrol. Process., vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 1807–1829, 2002. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Sen, “Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau,” J. Am. Stat. Assoc., vol. 63, no. 324, pp. 1379–1389, Dec. 1968. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Hirsch, J. R. Slack, and R. A. Smith, “Techniques of trend analysis for monthly water quality data,” Water Resour. Res., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 107–121, Feb. 1982. [CrossRef]

- “Production and consumption Gross energy consumption by source,” Borgartún 21A, 105 Reykjavík, 2023. https://statice.is/statistics/environment/energy/production-and-consumption/.

- G. Harrison, “The Year of Africa,” The African presence, pp. 1–24, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G.I.Khanin, “The 1950s: The Triumph of the Soviet Economy,” Eur. Asia. Stud., vol. 55, n, pp. 1187–211, 2003, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3594504.

- D. E. Stewart, C. Hardy, W. Kent, and S. All, “Encyclopædia Britannica zoom _ in First edition zoom _ in keyboard _ arrow _ right,” pp. 1–15, 2023.

- J. L. Love, “The Rise and Decline of Economic Structuralism in Latin America : New Dimensions,” Lat. Am. Res. Rev., vol. Vol. 40, N, pp. 100-125 (26 pages), 2023.

- C. W. van Eck, B. C. Mulder, and A. Dewulf, “Online Climate Change Polarization: Interactional Framing Analysis of Climate Change Blog Comments,” Sci. Commun., vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 454–480, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Pitt, “Increased Temperature and Entropy Production in the Earth’s Atmosphere: Effect on Wind, Precipitation, Chemical Reactions, Freezing and Melting of Ice and Electrical Activity,” J. Mod. Phys., vol. 10, no. 08, pp. 966–973, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. N. Lal et al., National systems for managing the risks from climate extremes and disasters, vol. 9781107025. 2012.

- H. E. Beck, N. E. Zimmermann, T. R. McVicar, N. Vergopolan, A. Berg, and E. F. Wood, “Present and future köppen-geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution,” Sci. Data, vol. 5, pp. 1–12, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Kottek, J. Grieser, C. Beck, B. Rudolf, and F. Rubel, “World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated,” Meteorol. Zeitschrift, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 259–263, 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. Tabari and P. Willems, “Lagged influence of Atlantic and Pacific climate patterns on European extreme precipitation,” Sci. Rep., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Gibbins and J. D. Haigh, “Entropy production rates of the climate,” J. Atmos. Sci., vol. 77, no. 10, pp. 3551–3566, 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. V. Kharin, F. W. Zwiers, X. Zhang, and M. Wehner, “Changes in temperature and precipitation extremes in the CMIP5 ensemble,” Clim. Change, vol. 119, no. 2, pp. 345–357, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. H. and A. J. C. Philip K. Thornton, Polly J. Eriksen, “Climate variability and vulnerability to climate change : a review,” pp. 3313–3328, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. G. R. Langdon and J. J. Lawler, “Assessing the impacts of projected climate change on biodiversity in the protected areas of western North America,” Ecosphere, vol. 6, no. 5, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Ramirez-Villegas et al., “Climate analogues: finding tomorrow’s agriculture today,” Work. Pap. No. 12, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 40, 2011.

- R. S. L. Lovell, T. M. Blackburn, E. E. Dyer, and A. L. Pigot, “Environmental resistance predicts the spread of alien species,” Nat. Ecol. Evol., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 322–329, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. F. Stocker et al., “Physical Climate Processes and Feedbacks,” Clim. Chang. 2001 Sci. Bases. Contrib. Work. Gr. I to Third Assess. Rep. Intergov. Panel Clim. Chang., p. 881, 2001.

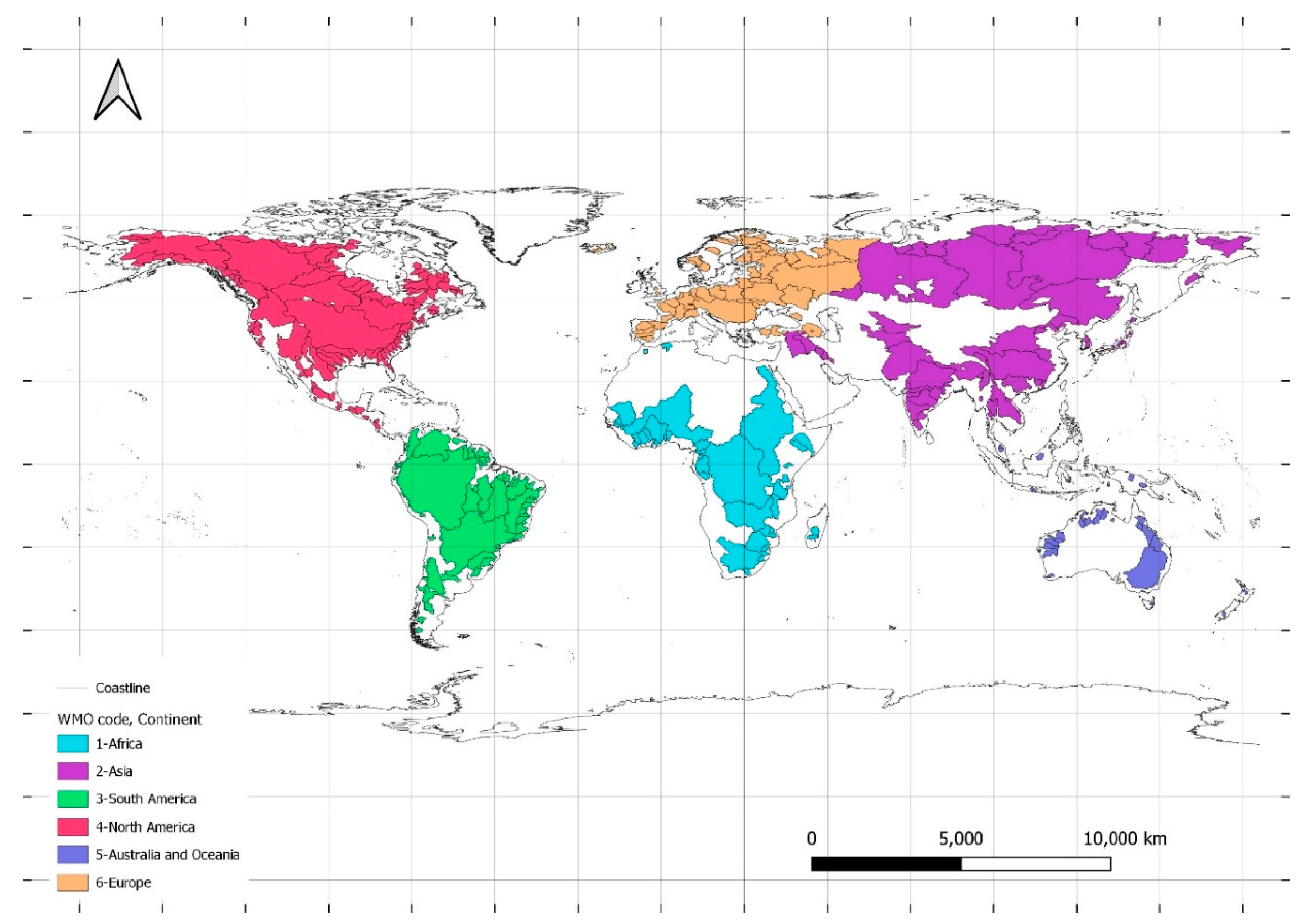

| Region WMO | Continent | Land area | Area catchment | Coverage of the continents |

| WMO_REG | 106 km2 | 106 km2 | % | |

| 1 | Africa | 30.3 | 8.43 | 27.83% |

| 2 | Asia | 44.3 | 20.3 | 45.86% |

| 3 | South America | 17.8 | 12.6 | 70.57% |

| 4 | North America | 24.2 | 13.0 | 53.87% |

| Antarctica | 13.1 | 0.0 | 0.00% | |

| 5 | Australia and Oceania | 8.5 | 1.1 | 13.07% |

| 6 | Europe | 10.5 | 6.7 | 64.10% |

| Total land area | 148.7 | 65.1 | 43.77% | |

| Earth, total | 509.9 | 65.1 | 12.76% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).