1. Introduction

One way to combat climate change is to promote renewable energy sources. For this reason, many countries all over the world have set up targets to produce a certain proportion of energy from renewable energy sources (RES). Biomass is one of the most significant RES in most Central European countries. This region has been hit by bark beetle calamity recently. We focus on the Czech Republic, twhich can be seen as a case study for the whole of Central Europe. In the Czech Republic, forest biomass is the largest source of clean energy. Biomass at the same time is quite flexible unlike many other RES, i.e. it can be burnt in the conventional power plants. However, transportation of biomass from one location to another may be cost-ineffective. In this article we have extended the Czech energy system optimizing model TIMES-CZ by splitting it into NUTS3 +1 regions. This allows for a more accurate allocation of the limited forest biomass given the transportation costs between the regions. In addition, we evaluate the impact of the potential spruce bark beetle calamity development scenarios on the Czech energy system until 2050.

Since 2012 bark beetles have been massively destroying spruce trees which occupy roughly half of the Czech forests [

1]. Institute for Forest Ecosystem Research (IFER) developed four possible scenarios on the availability of biomass for energy purpose given the spread of spruce beetles by Czech regions. These scenarios help measure the preparedness of Czech energy system to reach greenhouse gas emission reduction targets. Since forest biomass is unequally distributed across Czech regions as well as the infestation with spruce beetle is not uniform, it is crucial to apply the regionalization of the energy system modelling software.

TIMES-CZ is a complex energy system modelling tool. It uses energy balance components and certain constraints as inputs in order to identify the least-cost mix of energy technologies for a given time horizon. The original model [

2] had restricted capability to distinguish energy production and demand technologies by location. Regionalization of the model more conveniently takes into consideration possible transportation costs of energy fuels between the regions, enforces more realistic decisions on where to install new power plants, and facilitates trade. Therefore, regionalized TIMES-CZ model enhances the resolution of the Czech energy system.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, we describe the model and data used in the analysis. The modeled scenarios and their assumptions are described in

Section 3. We then analyze and discuss the results of the model in

Section 4 after which we conclude the paper in

Section 5.

2. Regionalized TIMES-CZ and Trade Parameters

TIMES is a bottom-up energy system optimization model which under initial conditions and certain constraints searches for a least-cost path to satisfy energy service demands. TIMES is developed and maintained within the Energy Technology System Analyses Program (ETSAP) by the International Energy Agency (IEA) [

3]. TIMES-CZ originally was a part of Pan-European TIMES PanEu model developed by the Institute of Energy Economics and Rational Energy Use at the University of Stuttgart [

4]. However, original TIMES-CZ model was a more aggregated version of the Czech energy system.

Multiple attempts have been made to improve the resolution of the TIMES-CZ model in the past. In the following, we list the ones more essential to the current research. First, thanks to the available data on individual facilities under EU ETS scheme, we have been able to identify locations, efficiencies, consumption of energy fuels, output of heat and power or various types of emissions for individual facilities. For the facilities outside the EU ETS scheme, we have kept the original structure of the TIMES-PanEu model. We, nevertheless, have split up the aggregated non- EU ETS energy sources by NUTS3 +1 regions [

5,

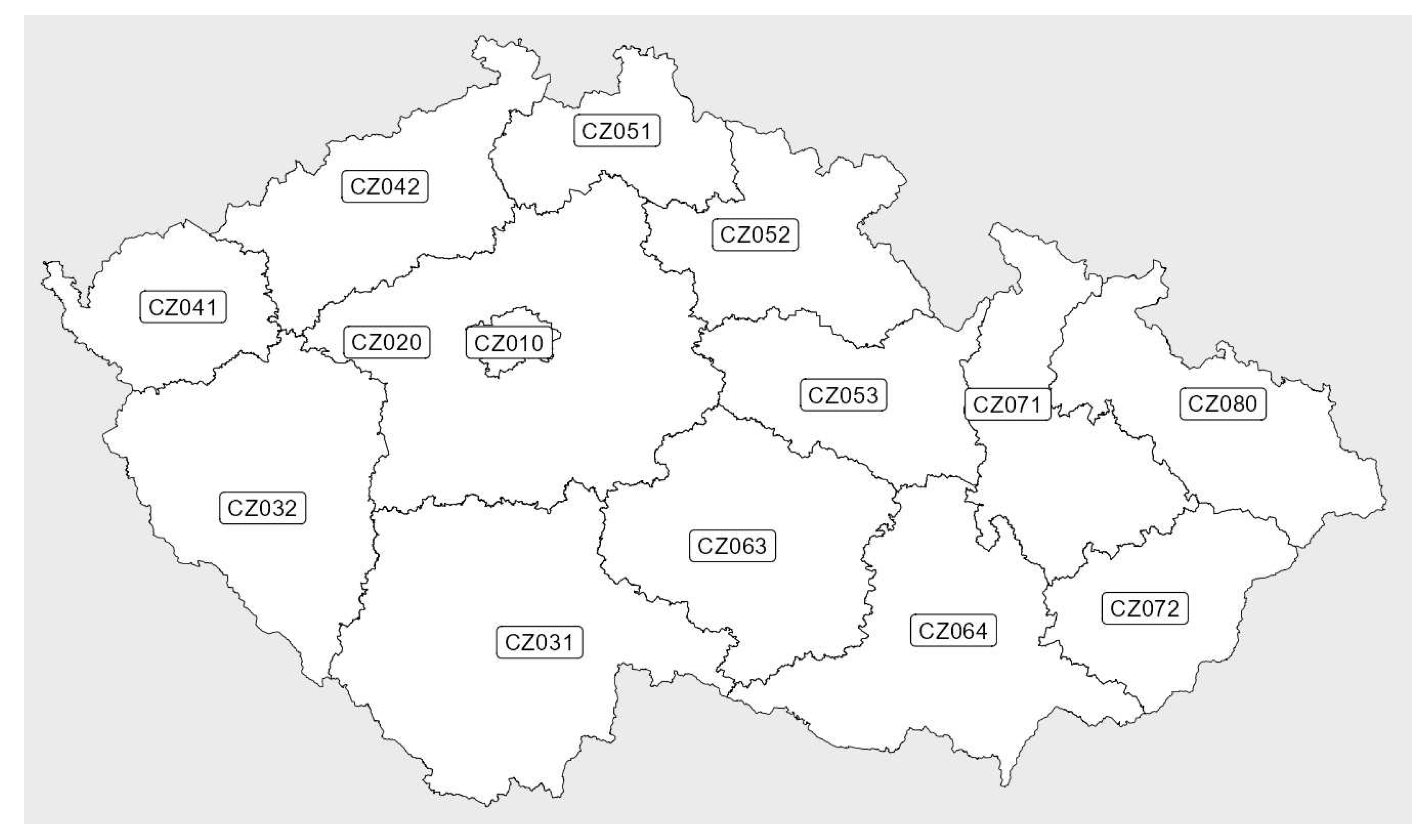

6], where NUTS3 classifies Czechia into 14 regions depicted on

Figure 1 and +1 implies Czechia aggregated as one region.

Second, we have regionalized final energy demand for the residential and commercial sectors by NUTS3 +1 regions using ENERGO data [

7] combined with the data on available stock of houses distinguished by family type, semi-detached or multi-flat buildings and by regions. Third, we have changed the base year to 2019. This is the year from which we take the Czech energy balance sheet as an initial condition for the model. One may argue that in 2019 the economy was behaving abnormally due to COVID19. However, comparing the 2018 and 2019 energy balance sheets, we could not observe significant differences. In perspective, a more recent base year certainly allows for a more accurate prediction of the future allocation of energy resources. Finally, we have integrated the forest biomass development scenarios by types of biomass.

Spruce bark beetles have become a major problem for Czech forests since 2012. These beetles destroy massive areas of forests as spruce is one of the most widespread species of trees. With the climate warming, bark beetles multiply even faster and the pace of felling trees and removing them from the forests fails to catch up. The driven calamity threatens the availability of biomass for various purposes, including energy.

IFER analyzed possible pathways for managing and adapting Czech forests to respond to the challenge. They developed four possible scenarios for the evolution of the bark beetle calamity [

8].

RED scenario, which we use as the baseline, anticipates that the spruce beetle calamity would subside in the existing area. The

GREEN scenario predicts that the calamity would end sooner than in

RED and allows 6% higher timber harvesting than the other three scenarios. The

BLACK scenario conjectures that the calamity would spread towards western regions given the riskiness level involved and finally, the

BLACK-REP scenario envisions that the calamity would repeat every ten years.

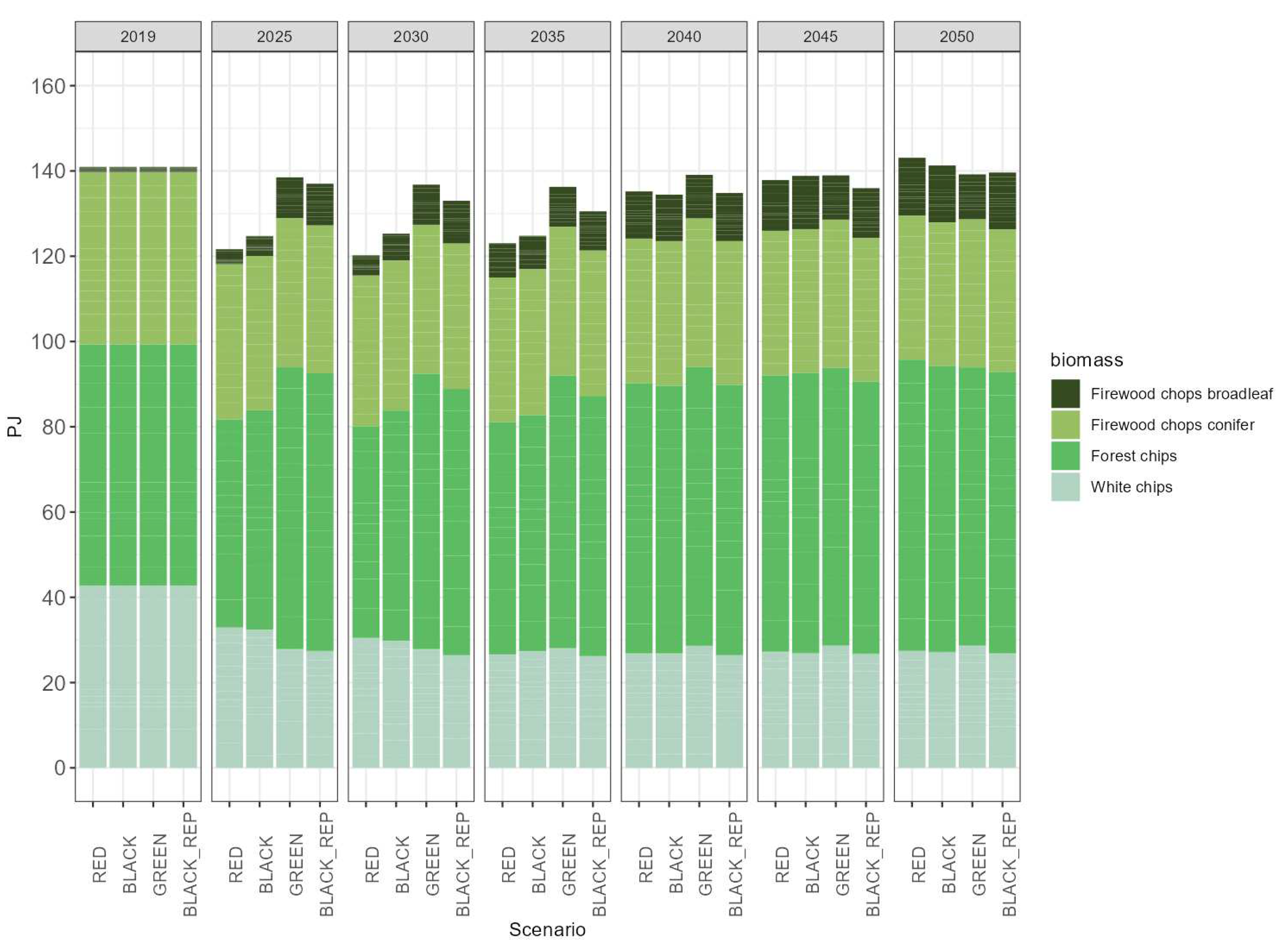

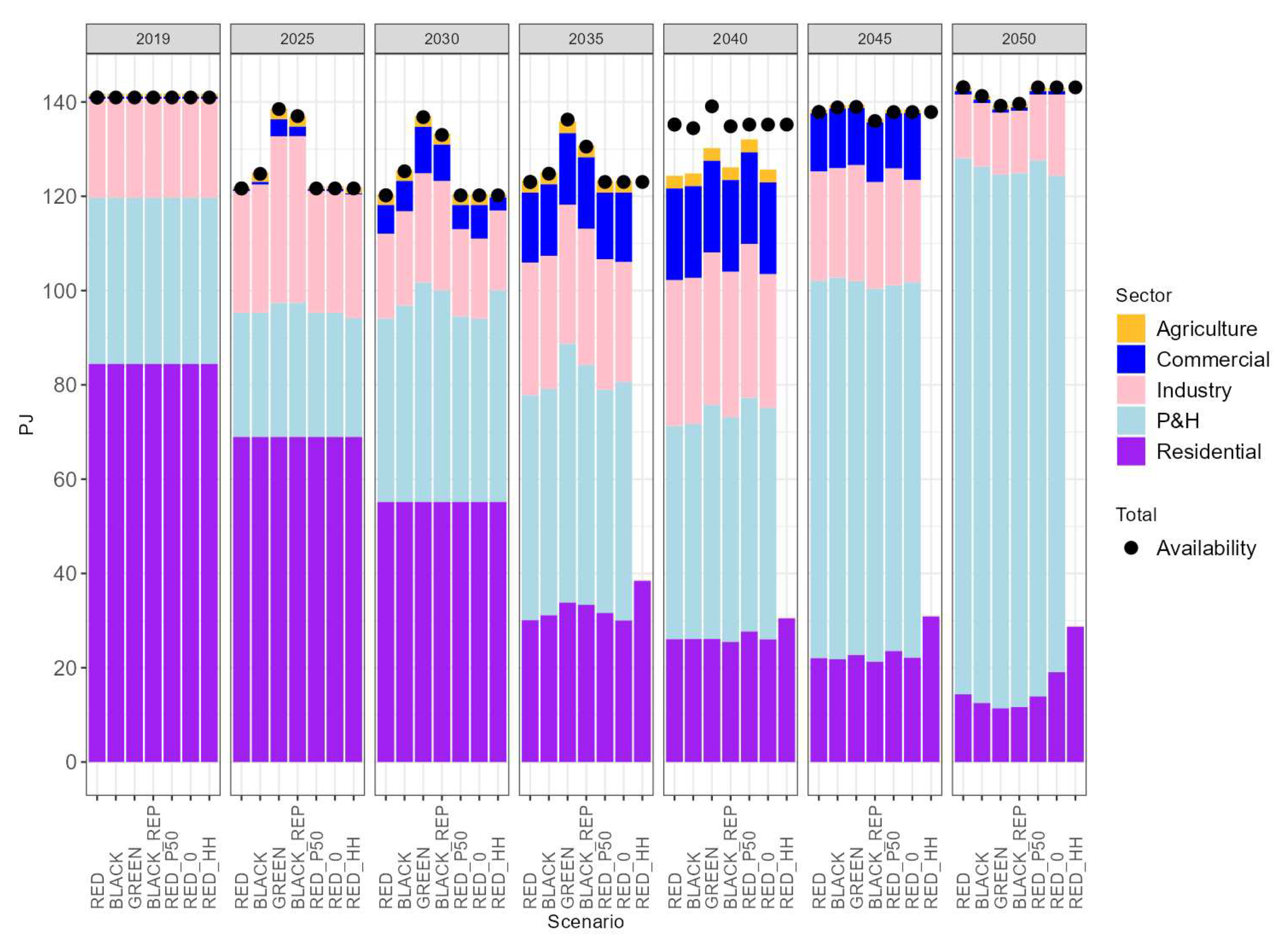

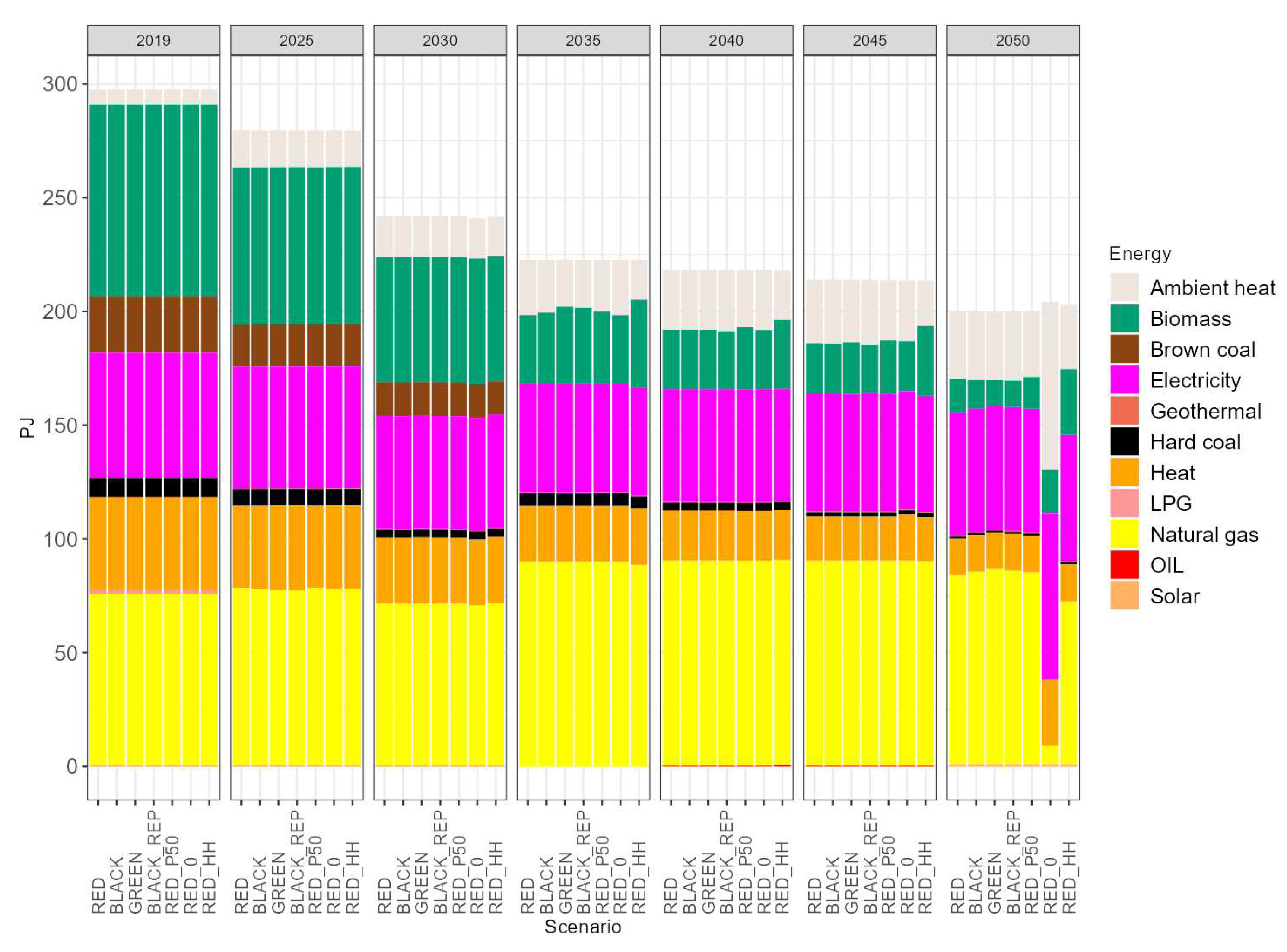

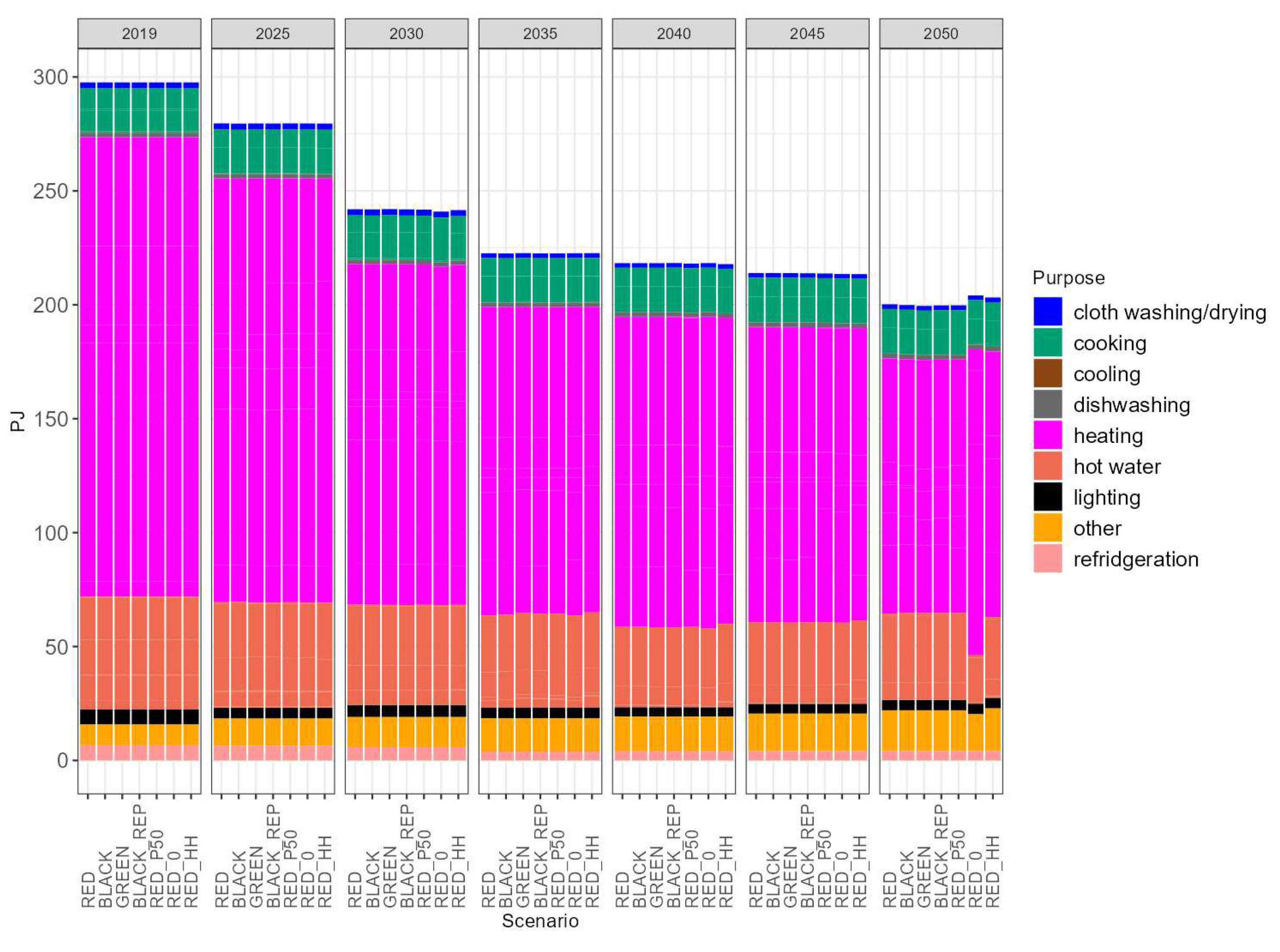

Figure 2 depicts the maximum amount of biomass harvest possible for energy purposes under these four scenarios. From

Figure 2 it is clear that the largest differences between scenarios occur in 2025 - 2035. Nevertheless, the magnitude may not be large enough to drive significant differences in the final allocation of resources.

In

Figure 2 it can be seen that biomass is categorized by types. Types of wood differ based on their energy content and quality. Such properties determine which type of wood is used primarily for what purpose. For example, firewood and pellets derived from white chips are primarily used by the residential sector, while forest chips are favored for heat and power production and industry. The

Figure 2 depicts the maximum possible supply of white chips and firewood. To avoid converting biomass into more expensive products, such as pellets, the model directs unprocessed white chips to power and heat and industry.

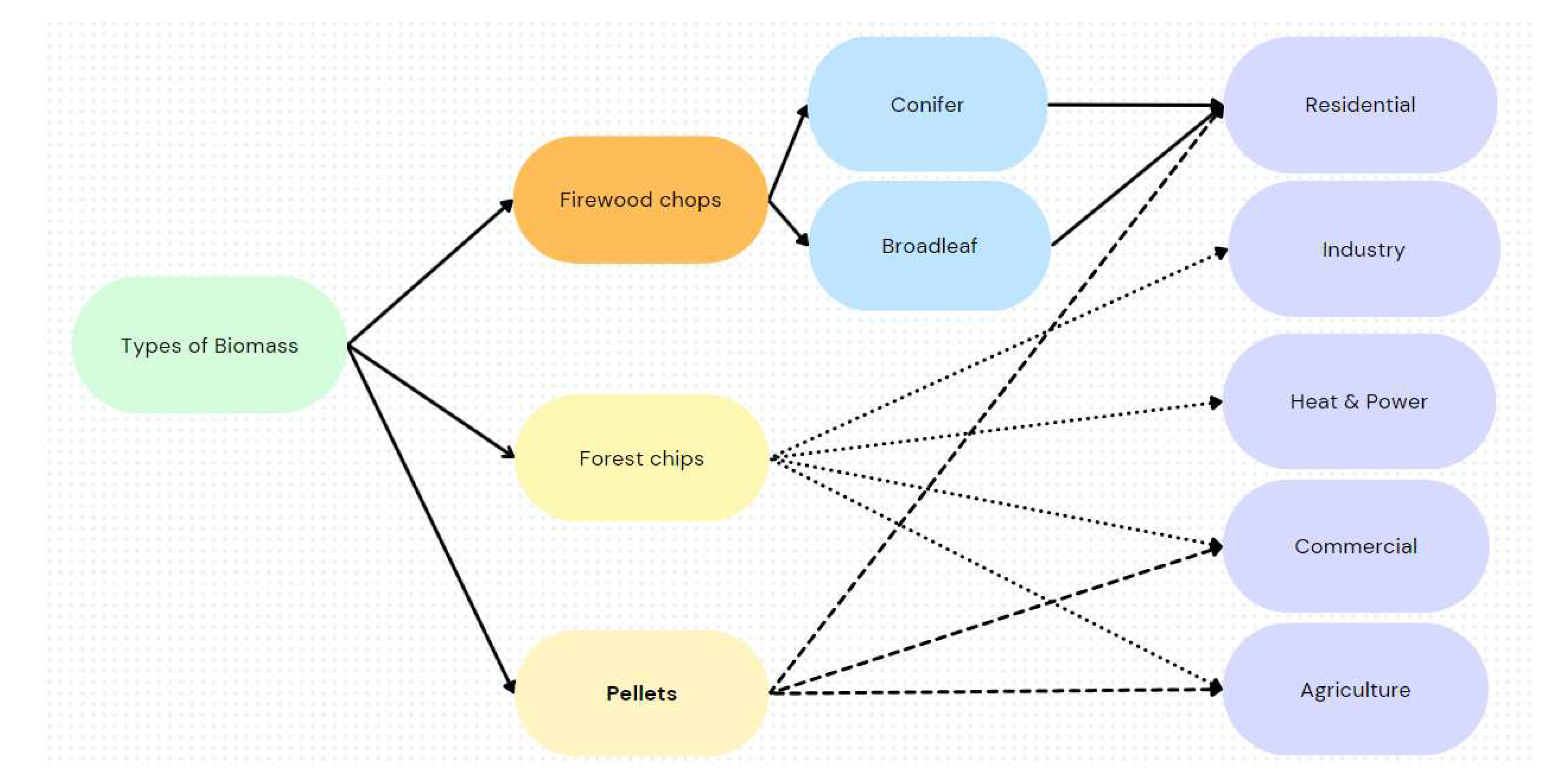

The general scheme of biomass flows across sectors and the price range for types of wood are shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 1, respectively.

The regionalized TIMES-CZ model takes into consideration the transportation costs of biomass. Transportation cost is distance-specific and time-variant. We have combined various sources to calculate average transportation costs for different types of wood.

Pellets and briquettes derived from white chips can be purchased in online stores. Online stores typically have fixed costs of transportation, around 45€. Given that pellets have roughly energy content of 18 MJ/kg [

9] and a typical homeowner would need approximately 2-3 tones of pellets [

10], in the cheapest case, to transport white chips would cost 0.8 €/GJ irrespective of the distance.

With firewood, calculating the transportation cost is more complex. For example, firewood is typically sold in one-cubic-meter cords (prm), where depending on whether the wood is ordered (prmr) or not (prms), weight and accordingly, energy content (

E) will differ [

11]. In addition, coniferous firewood is lighter and has less energy content compared to broadleaf firewood per cubic meter. Furthermore, the maximum volume of transportation by service providers is limited and differs. Therefore, we had to rely on some average figures and assume 9 prmr of capacity to calculate total energy transported per ride. According to [

11], 1 prm of wood pallet contains roughly 475kg of broadleaf wood with energy content of 14.6 MJ/kg and 340 kg of coniferous wood with energy content of 15.6 MJ/kg with moisture content of 15%.

In addition, we derived a 14x14 distance matrix between the centers of Czech regions to allow for trade between each of them. Because transportation companies typically charge for both the outbound and inbound transportation of biomass, we doubled the distances (

D) and multiplied them by the average transportation cost (

C) of biomass per kilometer. We obtained the average transportation cost (

C) of biomass per kilometer by reviewing offers from transportation companies. Subsequently, we divided the total transportation cost between regions by the total energy transported to calculate the cost of transportation between regions expressed in €/GJ. Therefore, simple formula for calculating the transportation cost of firewood between regions is the following:

where

is the transportation cost of biomass by type,

is the distance in kilometers between regions

i and

j,

C is the price of transportation per kilometer, and

is calculated total energy carried per ride by type of biomass. Equation

1 is valid for forest chips as well. Clearly, the assumptions on energy content are different. Forest chips, with 10% of moisture level have energy content of 16.4 MJ/kg, and 1 prms of forest chips weigh roughly 170kg [

11]. In addition, forest chips are primarily used by power and heat, and industry sectors, where transporting larger quantities on one ride is more likely. We assume the maximum capacity of the track reaches 85 prms [

12].

In the model, we also allow the transportation of biomass from regions to CZ as an aggregate region. We calculate the distance from each region to CZ as an average of all distances excluding Prague and Brno where availability of biomass is not significant. For the rest of the calculations equation

1 applies.

We made transportation cost time-variant considering EUA prices on CO2 emissions by HCT 2023 WAM schedule. EUA involves pricing

1 tone of CO2 emission in 2030 at 47 €/t and increasing it linearly every five years reaching 386 €/t in 2050. Provided that large tracks consume roughly 0.4 liters of diesel per kilometer [

13] and each liter of diesel produces 2.7 kg of CO2 [

14], then the time-variant element of the transportation cost starting from 2030 can be calculated by the following formula:

where

is the time-invariant part of the transportation cost calculated in equation

1,

is the EUA2 price of emission on tone of CO2,

l is the liters of diesel consumed per kilometer and EM is the tone of CO2 emitted per liter of diesel.

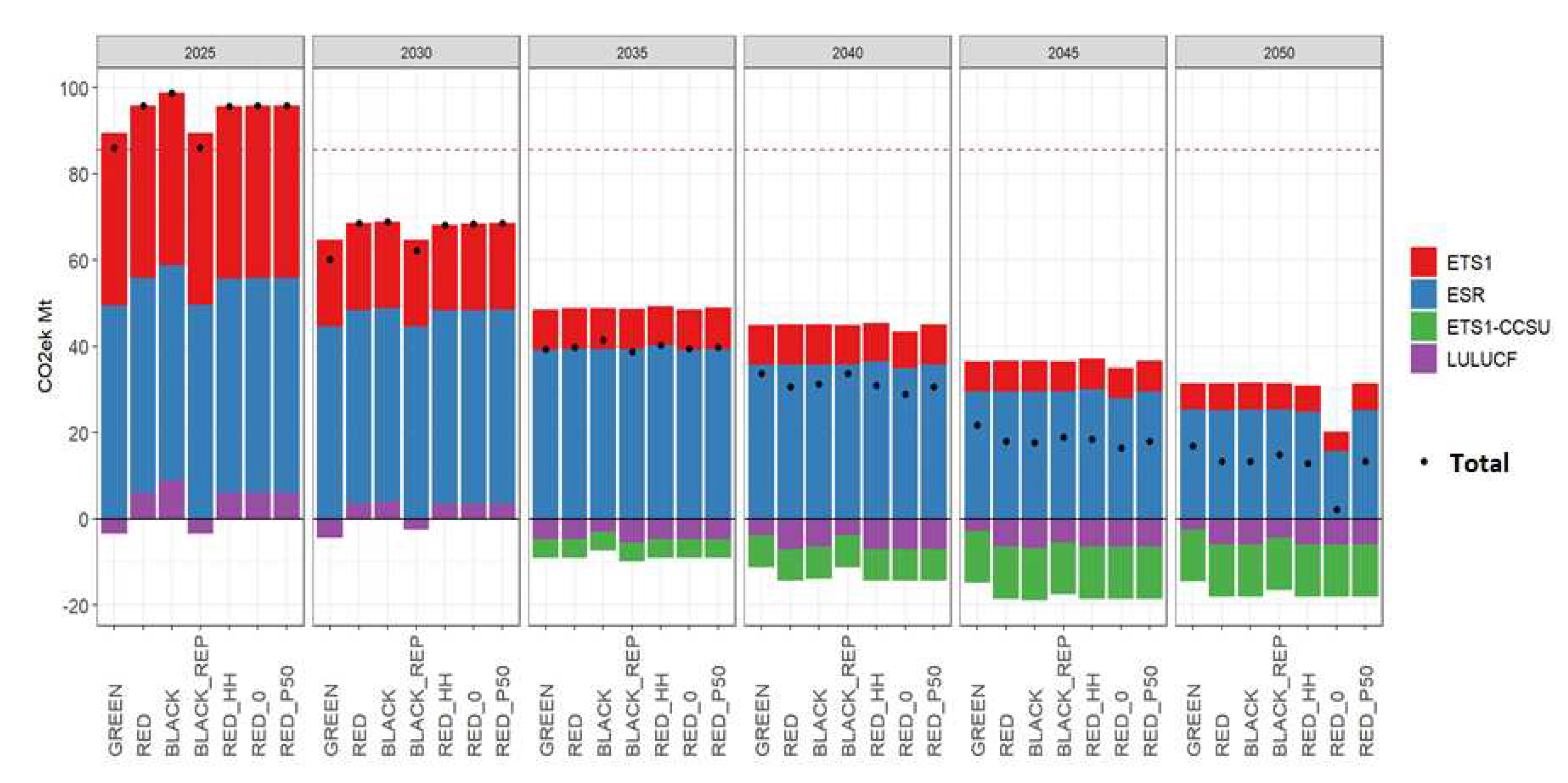

3. Scenarios

In order to assess the impact of various biomass development paths on the overall energy mix of the economy we first define the baseline scenario. The baseline scenario is derived from the National Energy and Climate plan [

15]. The main ingredients of the baseline scenario is that demands for energy services and energy-intensive products are derived from the National Plan. Czech Republic is assumed to be self-sufficient in terms of renewable and hydrogen energy production due to the fact that: (i) The main renewable energy source is biomass, which is not suitable for long-distance transportation, (ii) The effective State Energy Policy [

16] mandates to keep the import dependence for gaseous and liquid fuels at most at the current level, (iii) it is uncertain whether hydrogen will be sufficient for entire Europe to begin with [

17].

Other assumptions include: fossil fuel prices are according to HCT 2023 projection; development of new nuclear power plants is not limited and is the outcome of the model’s optimization problem; profile of possible electricity imports are according to Czech transmission system operator (ČEPS) and assumes no shortages; in 2050 maximum production of wind farms, solar PV’s and hydrogen imports are limited to 7 GW, 25.9 GW and 36.7 TWh, respectively; and carbon capture use and storage (CCUS). In the baseline scenario biomass development path is according to the

RED scenario of IFER predictions in

Figure 2. For this reason, we refer to the baseline scenario as

RED. Three other scenarios share the same assumptions as

RED but follow different IFER predictions from

Figure 2. These scenarios are referred to as

BLACK,

BLACK-REP, and

GREEN.

In addition to IFER projections, we consider three additional scenarios for sensitivity analysis. RED-0 assumes an exogenous reduction of greenhouse gas emissions to three megatons in 2050. The purpose is to see whether increased pressure to reduce emissions would encourage renewable production. RED-HH assumes that starting from 2030 biomass can only be consumed by households. The goal is to see how the limited availability of biomass would affect the overall energy mix and annualized system costs. Finally, RED-P50 considers 50% production cost subsidies on white chips to observe the possible substitution of alternative fuels with biomass. All three scenarios for sensitivity analysis rely on the projection of biomass development according to IFER.