4.1. Primary Energy Surces

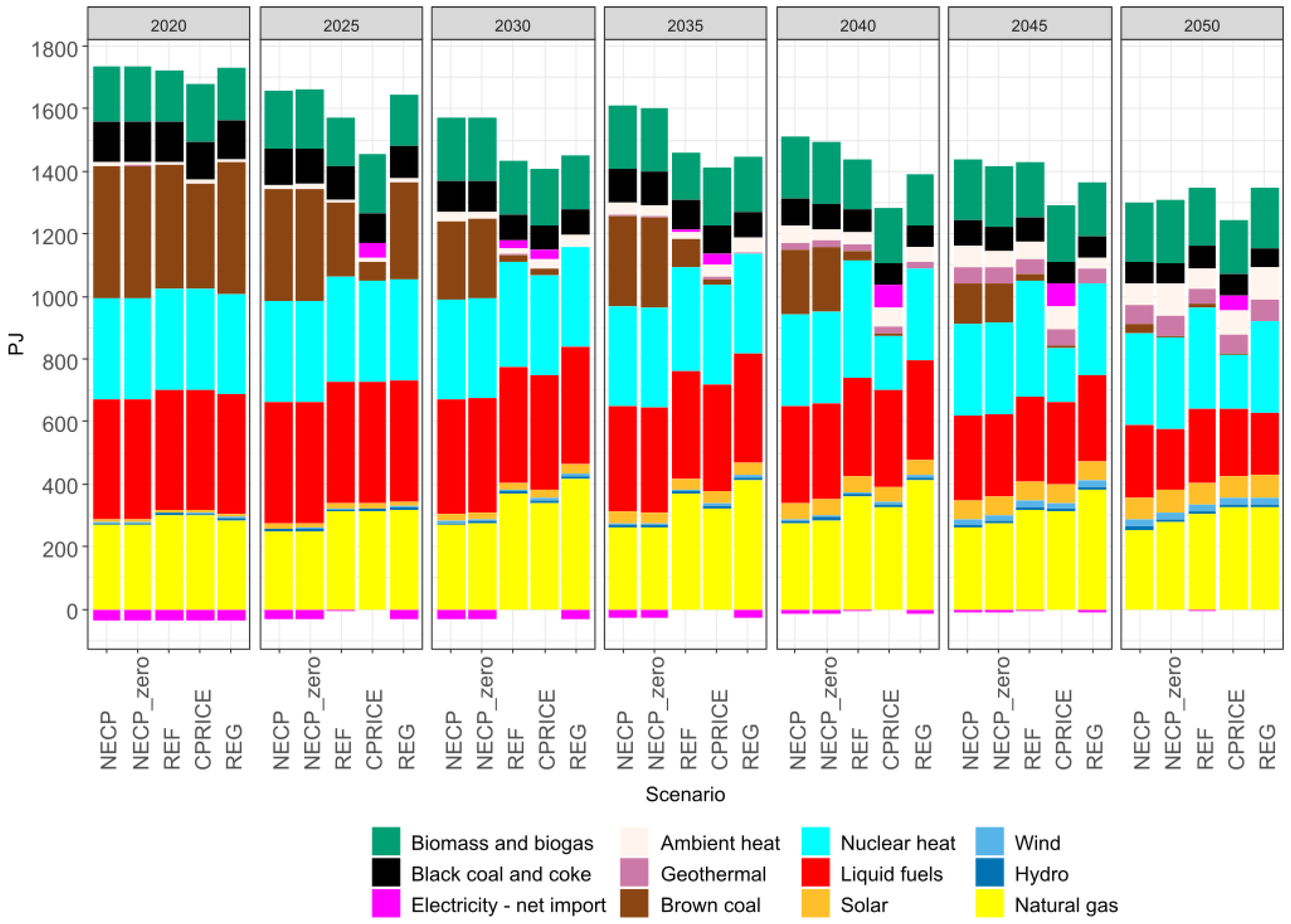

The evaluation of all modelled scenarios shows a general trend of a 24-30% decrease in consumption of primary energy sources (PES) by 2050 compared to 2015 (

Figure 1). The most rapid decline occurs in the CPRICE scenario, due to a rapid shift away from brown coal. The CPRICE scenario also has the highest net import of electricity - it is the only scenario that allows net import of electricity up to 20 TWh. In contrast, the slowest decline in PES consumption (and specifically of brown coal) occurs in the NECP and NECP_zero scenarios. After 2045, PES consumption is the highest in the REF scenario. In the REF, REG and partly also CPRICE scenarios, brown coal is mainly replaced by natural gas. In 2050, the total consumption of primary energy sources ranges from 1166 (CPRICE) to 1273 PJ (REF).

Consumption of black coal and coke falls in all scenarios to between 65 and 70 PJ in 2050, when it is almost exclusively used for iron and steel production. Consumption of fossil liquid fuels falls in all scenarios to between 194 (NECP_zero) and 235 PJ (REF) in 2050. In the REG scenario, brown coal consumption ceases from 2030 due to the cessation of domestic mining (exogenous assumption). In the other scenarios, brown coal consumption decreases to between 4.5 and 32 PJ (NECP). The NECP scenario is the only one where brown coal is consumed to a greater extent elsewhere than in households, specifically in electricity and heat generation.

Natural gas consumption is mainly influenced by assumptions about the future price of natural gas. In the NECP and NECP_zero scenarios, natural gas consumption in 2050 is the lowest, 255 and 279 PJ respectively. In the CPRICE, REF and REG scenarios, a significantly lower natural gas price is assumed (

Table 5) and its consumption increases significantly compared to the base year, peaking here between 2030 and 2040, from 339 (CPRICE) to 418 PJ (REG), and then natural gas consumption decreases to 303 (REF) to 327 PJ (REG).

In all scenarios, there is a significant increase in the consumption of flow RES, in the case of hydro, solar and wind, to the level of their projected potentials in 2050. Geothermal energy use ranges from 49 (REF) to 67 PJ (REG) in 2050.

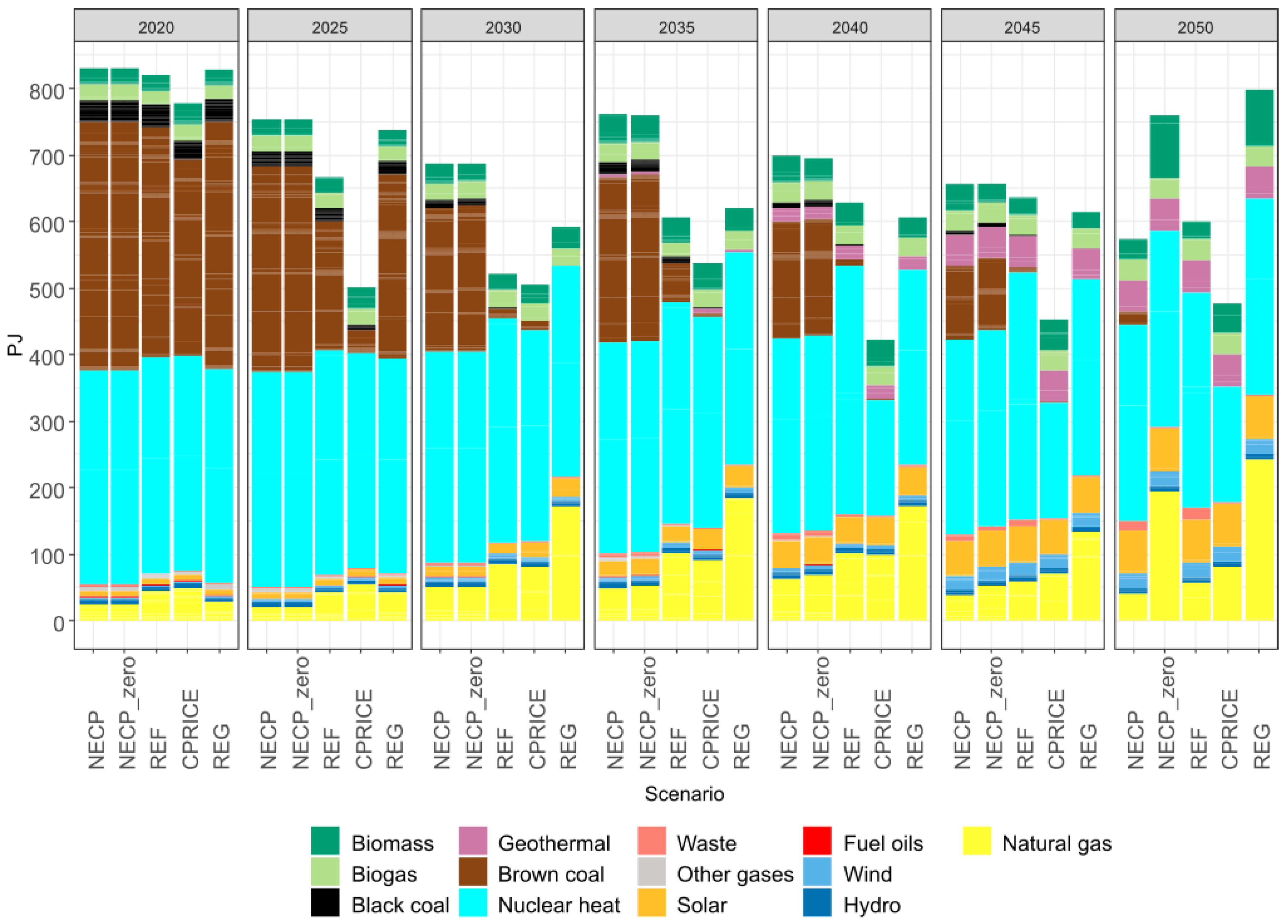

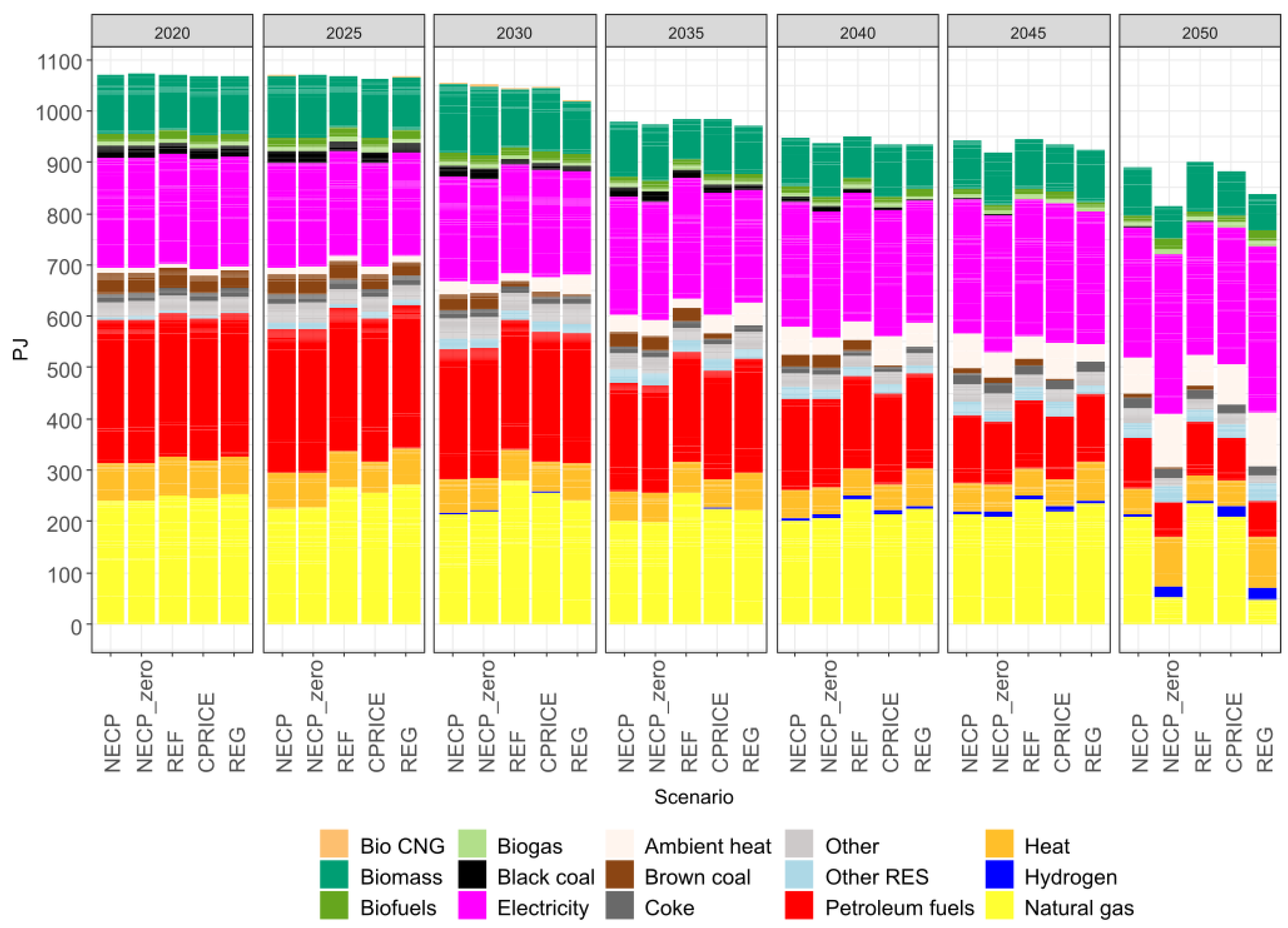

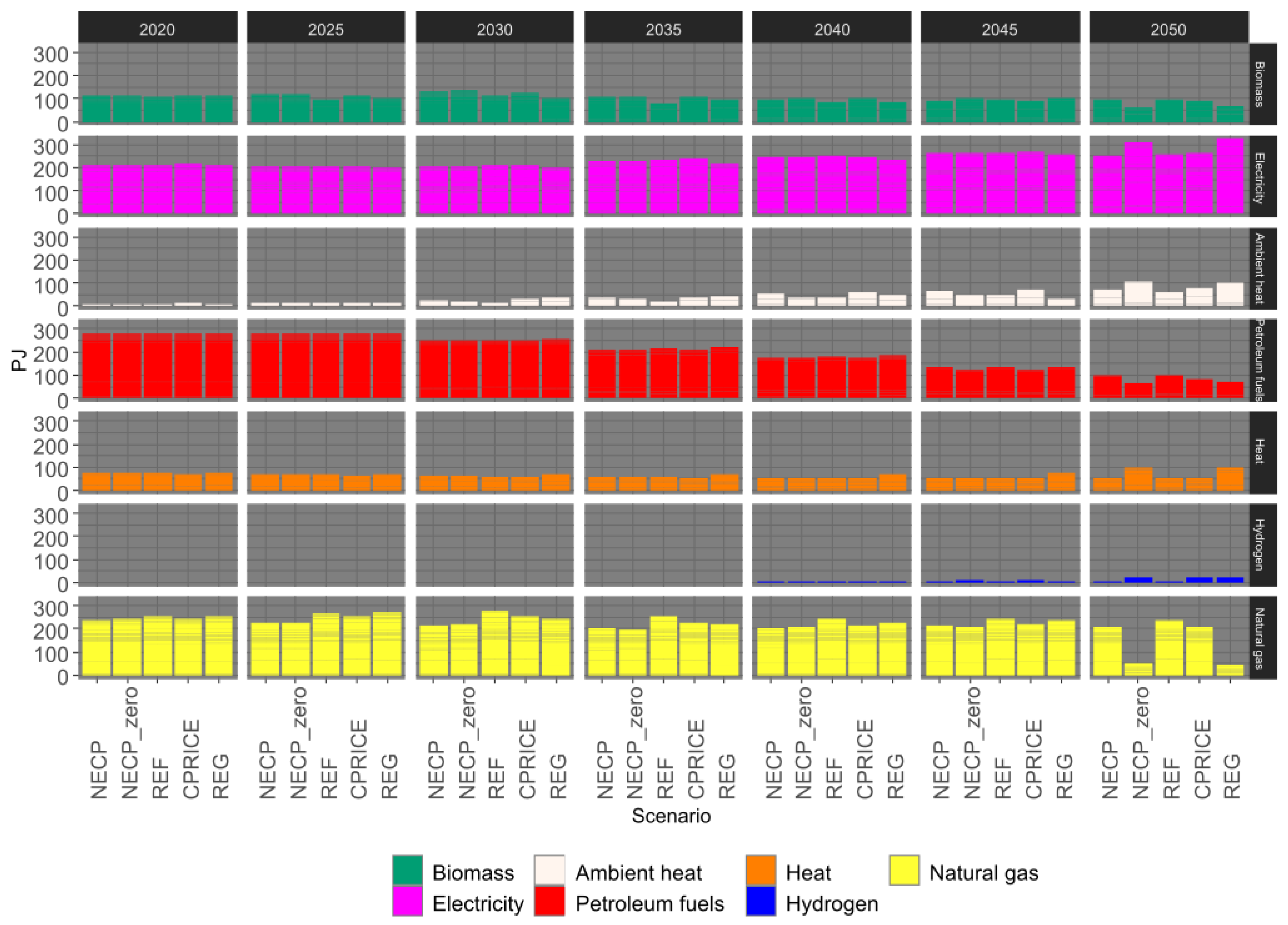

4.2. Energy Transformation - Electricity and Heat

In the energy consumption for electricity and heat production, the different rates of shift away from coal are again evident in the scenarios. In the CPRICE scenario, which assumes the highest allowance price while allowing for net imports of electricity from 2025 onwards, there is already a significant decline in brown coal consumption in electricity and heat generation (to 36 PJ) in 2025. In the REG scenario, brown coal is mainly replaced by natural gas already in 2030, while in the NECP scenario it is still marginally present (21 PJ) in 2050. In all scenarios, the representation of RES develops gradually, mainly solar, geothermal and wind energy; biomass use grows more slowly, except for a significant increase in the REG (87 PJ) and NECP_zero (97 PJ) scenarios in 2050, which is related to the need for carbon capture and storage (CCS) from biomass and a negative emission balance due to the scenario target of near to climate neutrality.

In all scenarios, there is a significant increase in flow RES (i.e. geothermal, solar, wind, and hydropower) and hydropower, solar, and wind reach their projected potentials in 2050.

4.4 Greenhouse Gas Emissions

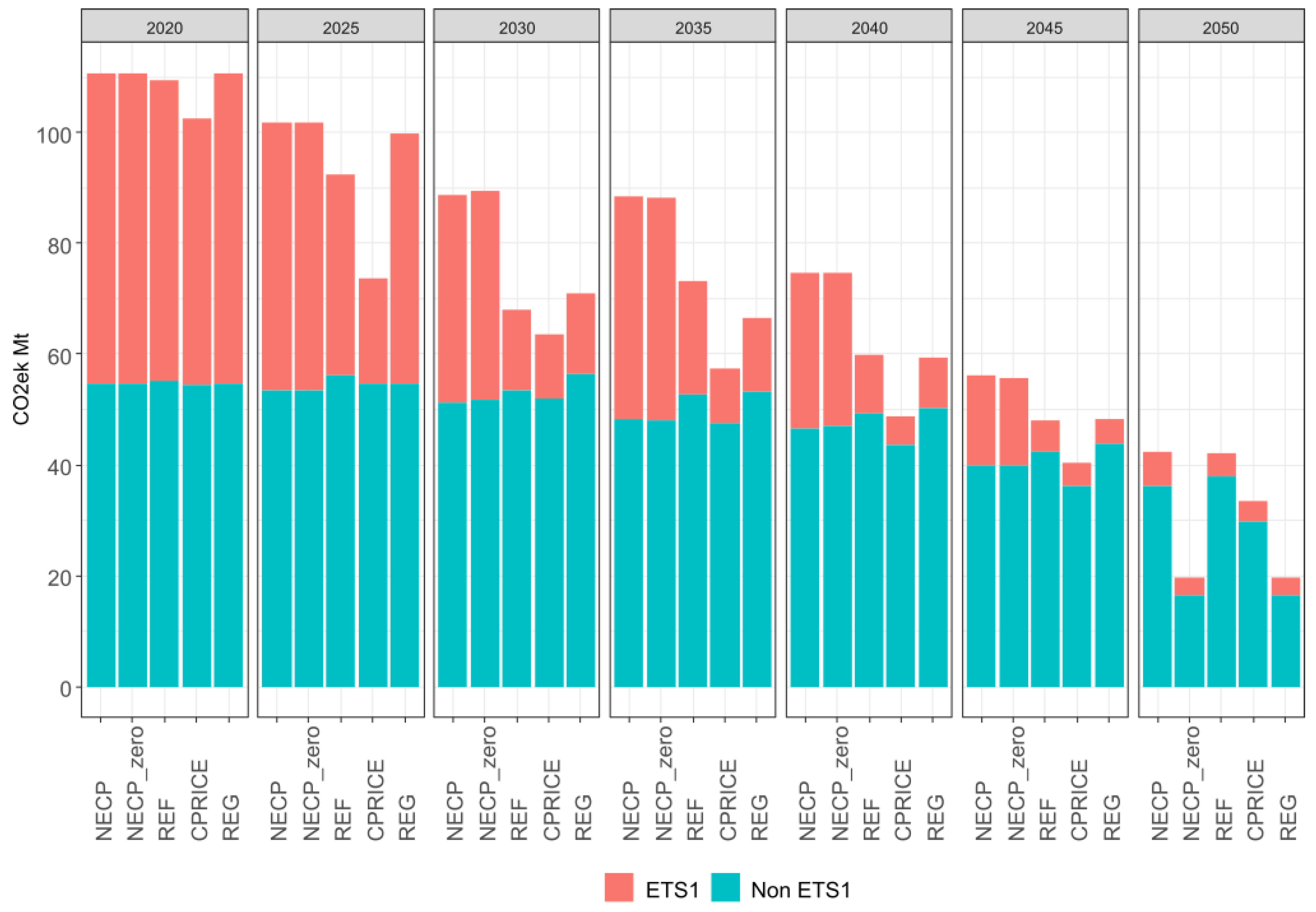

The distribution of GHG emissions between ETS and non-ETS sectors is summarized in

Figure 5. In the ETS sectors, emissions decline fastest in the CPRICE scenario, while the decline is slowest in the NECP and NECP_zero scenarios. The REF scenario assumes an EUA price in 2050 that is more than double that of the NECP scenario, and also almost half the price of natural gas. At the same time, due to decentralization and deliberate reduction of rated thermal input of fossil fuel heat plants and CHPs below 20 MW, individual installations are partially shifted from ETS to non-ETS. This shift of installations between ETS and non-ETS is one of the factors of the significantly faster decline in GHG emissions in the ETS sector compared to non-ETS.

Outside the ETS sectors, the decline is also initially largest in the CPRICE scenario, but after 2045 the largest reductions occur in the REG and NECP_zero scenarios, which aim to achieve carbon neutrality in 2050. However, carbon neutrality in 2050 is not achievable under the given assumptions (no imports of biofuels, hydrogen or electricity, and increasing emissions from agriculture). In the REG and NECP_zero scenarios, GHG emissions (not including LULUCF) are reduced to 20 Mt CO2ek, and taking into account the 4.5 Mt CO2ek captured from biomass sources, to less than 16 Mt CO2ek. Including the assumed LULUCF sinks, the REG and NECP_zero scenarios reduce the GHG emissions to less than 10 20 Mt CO2ek in 2050.

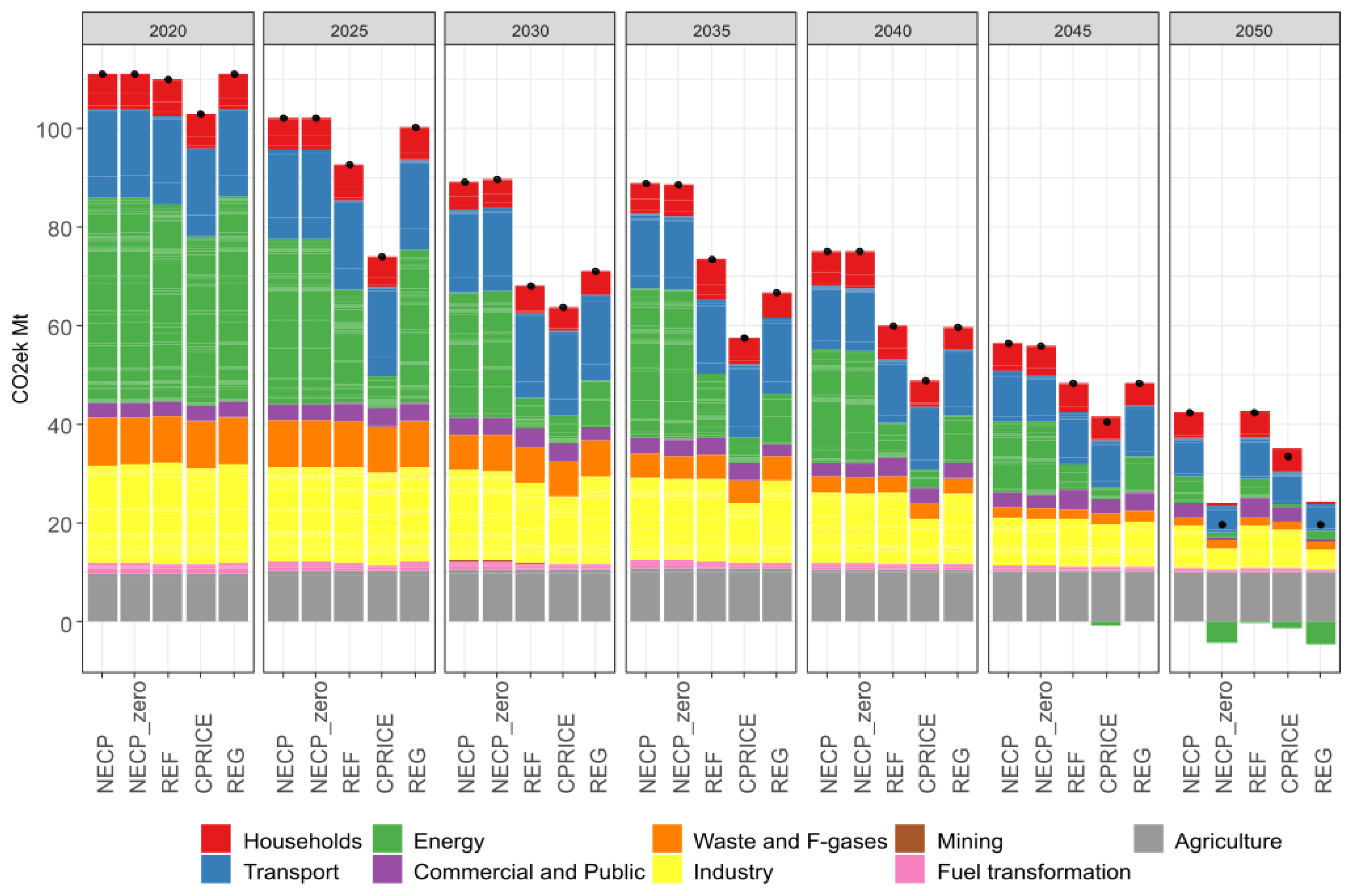

The GHG emissions decline fastest and the most significantly in the energy sector, across all scenarios. In the CPRICE, NECP_zero, REG and REF scenarios, the power sector even has a negative GHG emission balance, thanks to CCS technology in biomass electricity and heat production. In the scenarios with the lowest GHG emissions, NECP_zero and REG, the most significant GHG emitters are agriculture (9 Mt CO

2ek) followed by transport and industry (

Figure 6). GHG emissions from agriculture, waste and F-gases are in the model exogenous in the carbon balance.

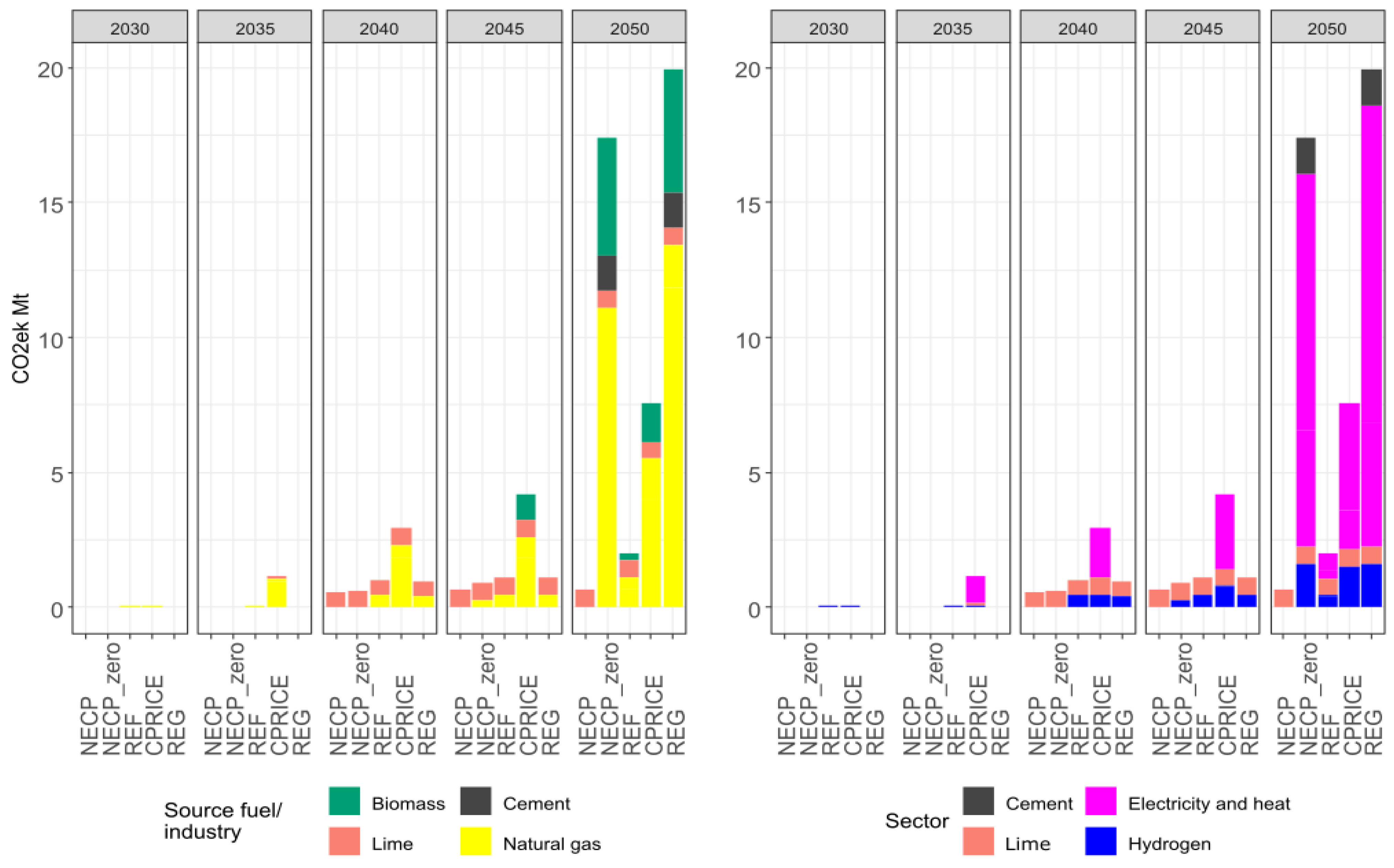

The CCS is piloted in 2030 in the CPRICE and REF scenarios. It is used to the least extent in the NECP scenario for lime production. In contrast, it is the most significant in the REG (20 Mt CO

2ek) and NECP_zero (17.5 Mt CO

2ek) scenarios, where CCS is mainly applied in the production of electricity and heat from natural gas and biomass, as shown in

Figure 7.

4.4.1. GHG Emission Savings and Comparison with the EC REF2020 Scenario

We evaluate the GHG emission saving and put them to the relation with the EC REF2020 scenario to assess the policy scenarios and to show if the EC REF2020 scenario is too ambitious for Czechia or not.

The overall GHG emission savings in 2030 of 55% compared to 1990 are realistic even at the Czech level, but mainly due to emission reductions in the EU ETS sectors.

Table 6 shows the savings in total GHG emissions compared to 1990 and the savings in nonETS sectors outside LULUCF (i.e. in ESR sectors) compared to 2005 for each scenario. The NECP and NECP_zero scenarios are the only scenarios that do not achieve an overall GHG emission reduction of 55% compared to 1990. The rate of GHG emission reductions in the ESR sectors is slow in all scenarios, which is also due to the increasing demand for energy services, and in 2030, GHG emissions in the ESR sectors are only reduced by 15 (REG) to 22% (NECP and NECP_zero) compared to 2005. After 2030, the rate of emission reductions in ESR sectors increases until 2050.

In 2050, the savings in total GHG emissions including LULUCF emissions range from 81% (NECP and REF) to 93% (NECP_zero and REG).

Table 7 shows the GHG emission savings in the EC REF2020 scenario and compares the main scenarios of this study with this scenario. We infer that the PRIMES model is most likely not able to correctly distinguish between ETS and non-ETS sectors due to its aggregation. In the REF2020 scenario, emissions in the ETS sectors are higher than verified EU ETS emissions [

31] and, conversely, emissions from the non-ETS sectors are underestimated (in 2005 ETS emissions in the REF2020 scenario are 8 Mt CO

2ek higher than verified emissions, in 2010 by 4.5 Mt CO

2ek , in 2015 by 8 Mt CO

2ek and in 2020 by 2 Mt CO

2ek). Again, this results in the REF2020 scenario achieving higher GHG savings in the non-ETS sectors than the scenarios modelled in this study.

The NECP and NECP_zero scenarios have higher GHG emissions than the REF2020 scenario in 2030. The other scenarios, applying additional policy measures on emissions, have lower total GHG emissions than REF2020 in 2030. The difference in non-ETS emissions between the modeled scenarios and the REF2020 scenario might be affected by the different structure of ETS and non-ETS sectors between the models.

In 2050, even the NECP scenario reaches 41 % lower total GHG emissions than the REF2020 scenario.

4.6. Cost

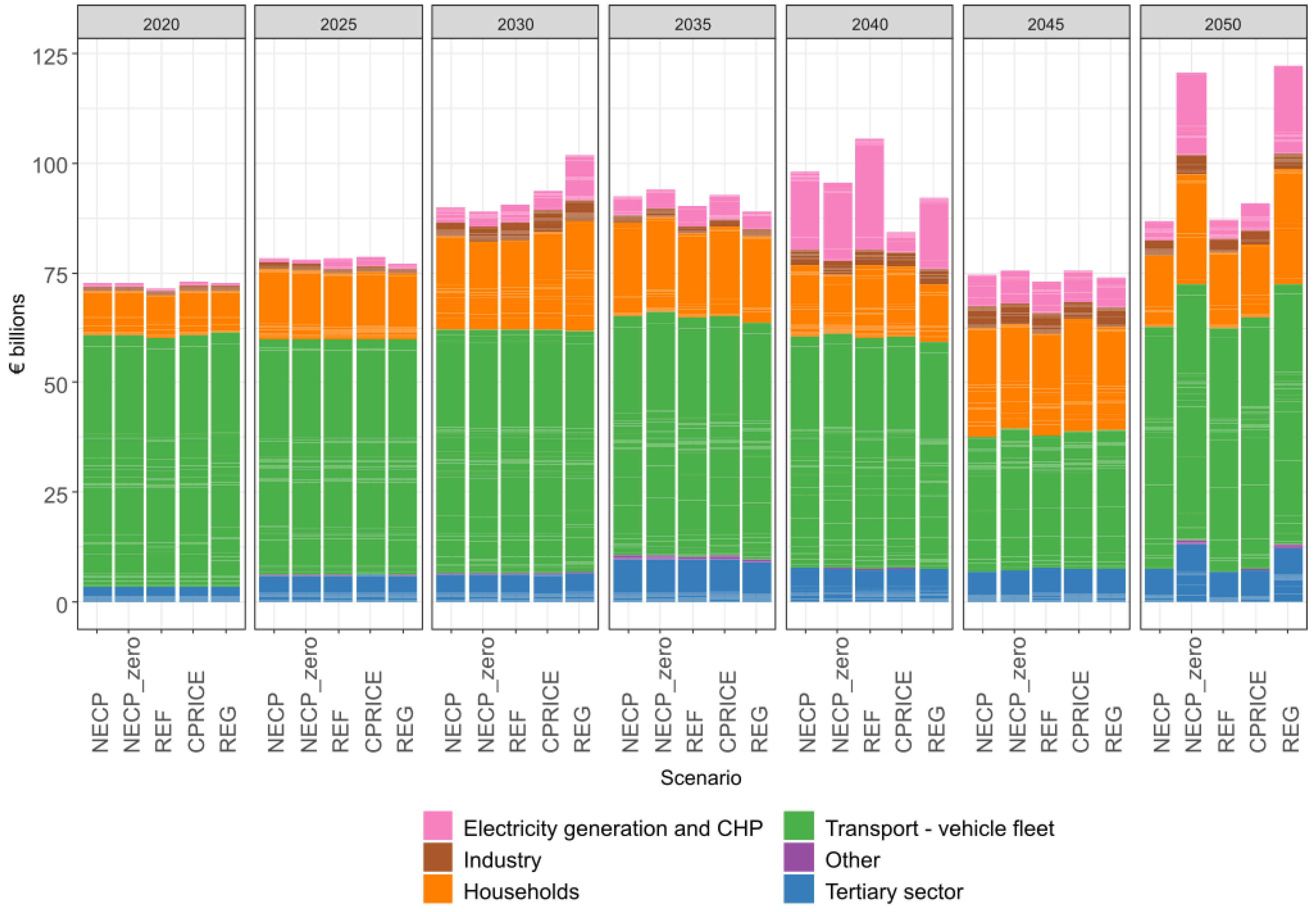

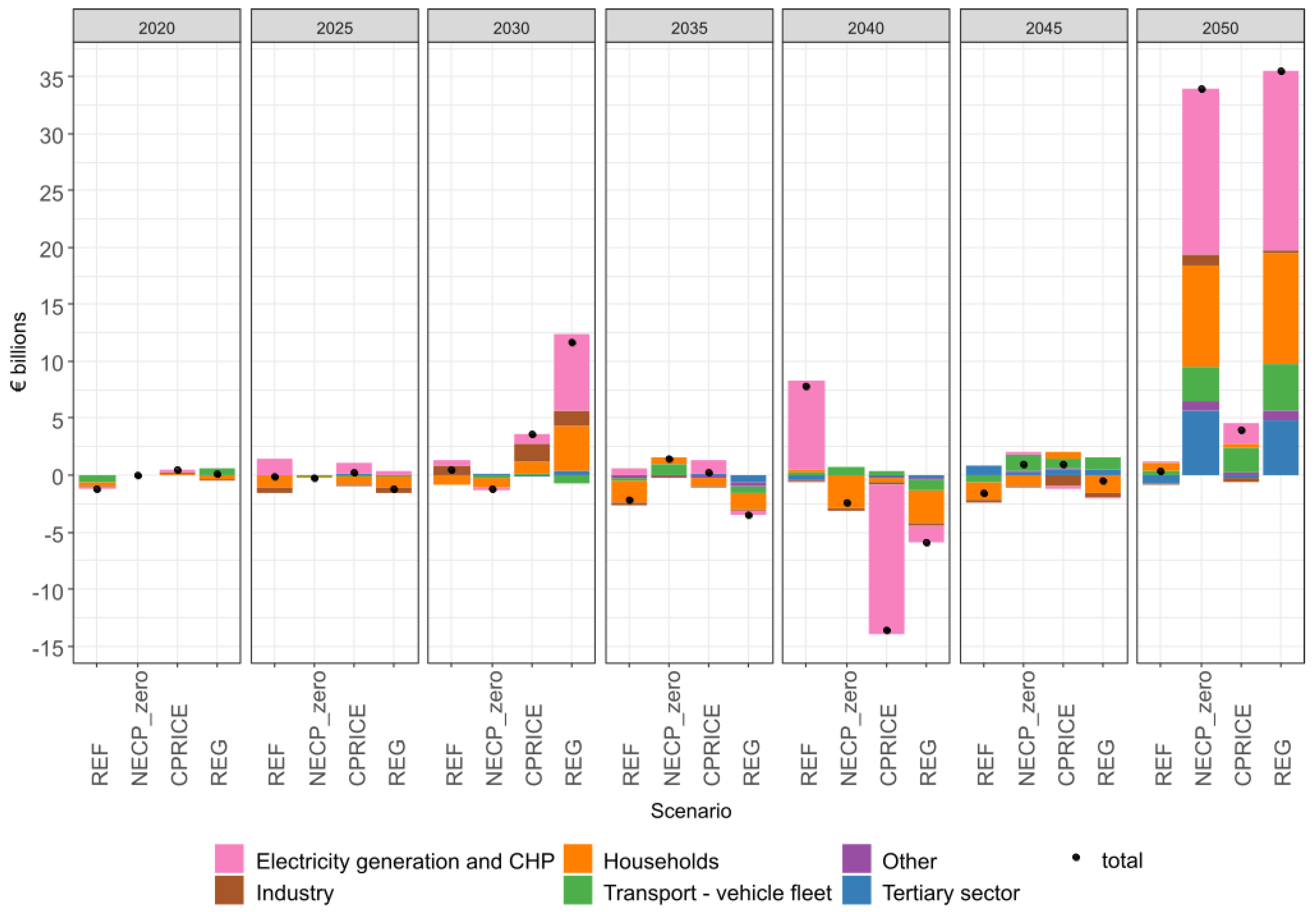

The investment costs of the whole system are on an increasing trend and are the most significant in the total cost structure of the whole energy system (including transport, industry, households, etc.) for all scenarios.

Figure 8 shows the overnight investment costs by sector, always aggregated over a 5-year period (e.g. "2030" covers the period 2028-2032) and

Figure 9 their differences from the NECP scenario, which serves as a reference scenario.

Road vehicles account for the largest share of investment costs. The drop in investment costs in road vehicles in 2045 is mainly due to the purchase of hydrogen vehicles in 2040 and partly due to some discrepancy in transport module, where detailed assumptions about available technologies end in 2040. This discrepancy is common to all scenarios and thus does not affect the assessment of the impacts of individual policies. All costs are in constant 2020 prices, excluding VAT.

It should be emphasised that, given the age of most of the technological units in the Czech Republic and the expected development of emission allowance prices, significant investments in new energy sources and energy savings will be necessary in the coming decades, regardless of the 2050 emission targets. Other significant investments are triggered by the natural renewal of technologies, e.g. the vehicle fleet, i.e. again regardless of emission targets. These (natural) investment costs (which would occur anyway) are quantified in the NECP scenario, which is the reference scenario in this respect.

In the NECP scenario, over the monitored period from 2018 to 2052, the cumulative investment costs in road vehicles - encompassing fleet replacement and partial transition to electromobility - amount to € 359 billion (i.e. 61% of total cumulative investment cost and on average € 10 billion per year), in households the cumulative investment costs amount to € 126 billion (i.e. € 4 billion per year on average), in the tertiary sector € 48 billion (i.e. € 1.4 billion per year on average), in the electricity and CHP sector € 39 billion (i.e. € 1.1 billion per year on average), and industrial investments related to energy processes or energy management amount to € 19 billion (i.e. € 0.5 billion per year on average). The total cumulative investment costs over 35 years in the NECP reference scenario amount to a total of € 591 billion (€ 17 billion on average per year).

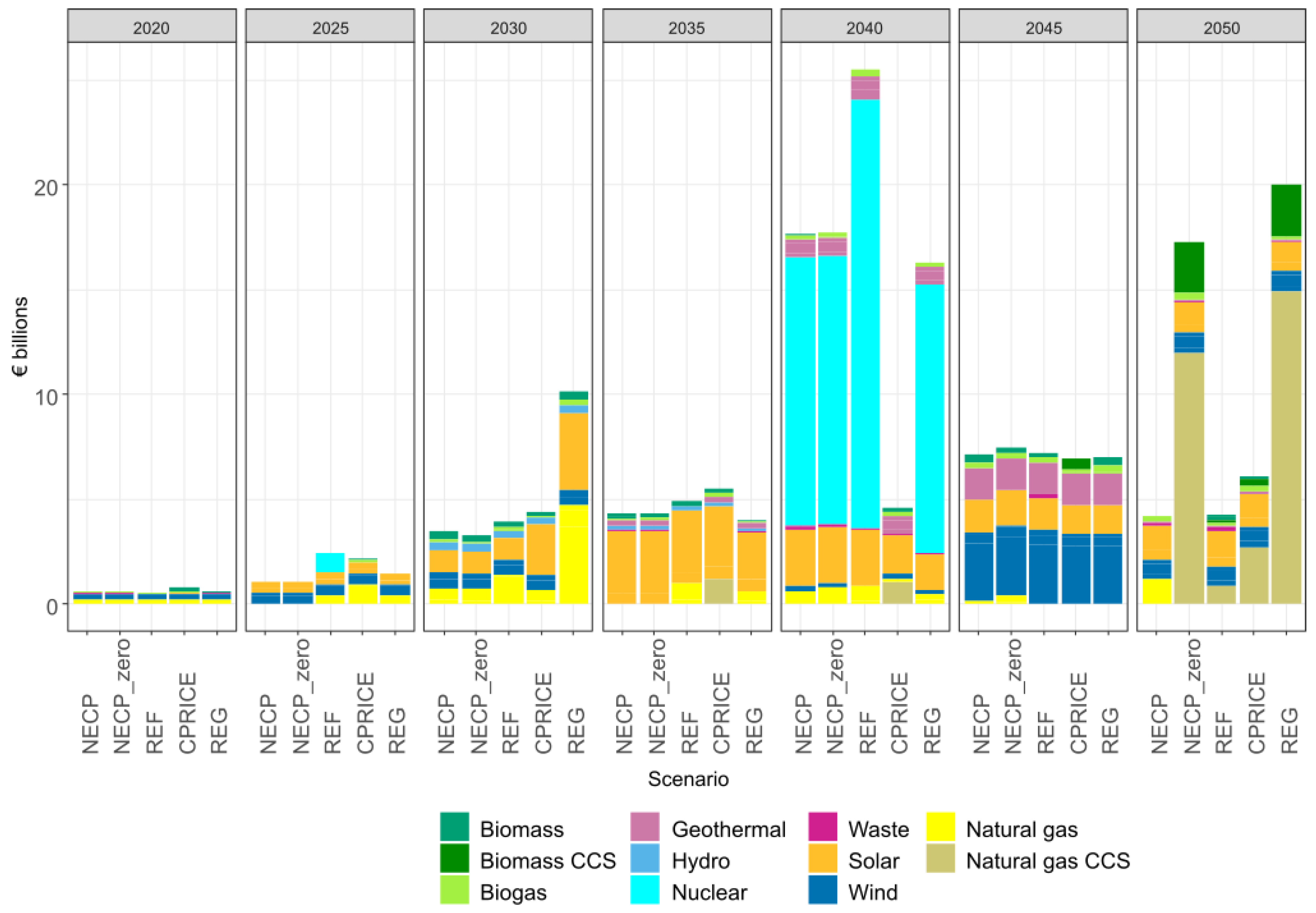

In terms of dynamics, investment in the energy sector for electricity and heat generation and in households grow the most over time (cf.

Figure 10). Newly installed nuclear units in 2040 in all scenarios (exogenous assumption) except CPRICE induce increased investment in electricity and heat generation by € 13 billion (NECP_zero, NECP, REG) and € 20 billion (REF). In the NECP scenario, investment in new nuclear power plants accounts for one third of all investment in the electricity and heat generation sector over the whole period.

In the NECP_zero and REG scenarios, targeting GHG emission neutrality, the investment costs in electricity and heat generation, households and the tertiary sector increase significantly after 2045. In the last period between 2048 and 2052, investment costs in the electricity and CHP sector are € 15 billion (+335%, i.e. € 3 billion per year on average) higher in NECP_zero than in the NECP scenario. In the tertiary sector, including public institutions, investment costs are € 6 billion (+75%, i.e. € 1.1 billion per year on average) higher in this period.

In REG, investment costs in the electricity and CHP sector are € 16 billion (+365%, i.e. € 3.2 billion per year on average) higher than in the NECP scenario over the period 2048-2052. In the tertiary sector, including public institutions, investment costs are € 5 billion (+63%, i.e. € 1 billion per year on average) higher in this period than in the NECP scenario.

For comparison, the gross fixed capital formation of the whole Czech economy was € 57 billion in 2020 [

32], the annual average of induced investment for the NECP reference scenario is around € 17 billion [

32]. For the REG scenario in the period 2048 to 2050, in which the average annual additional investment costs are not higher, they thus represent around 13% of the total gross fixed capital formation of the pandemic year 2020. In this comparison, the average annual additional investment in the electricity and CHP sector represents less than 6% of the total gross fixed capital formation in 2020.

The CPRICE scenario has the lowest total investment costs over the whole period, with the largest decreases in investment in electricity generation and CHP (no new nuclear units plus net electricity imports) compared to the other scenarios, while investment mainly in households and fleet renewal is higher than in the NECP and REF scenarios, which also do not have a 2050 emissions target.

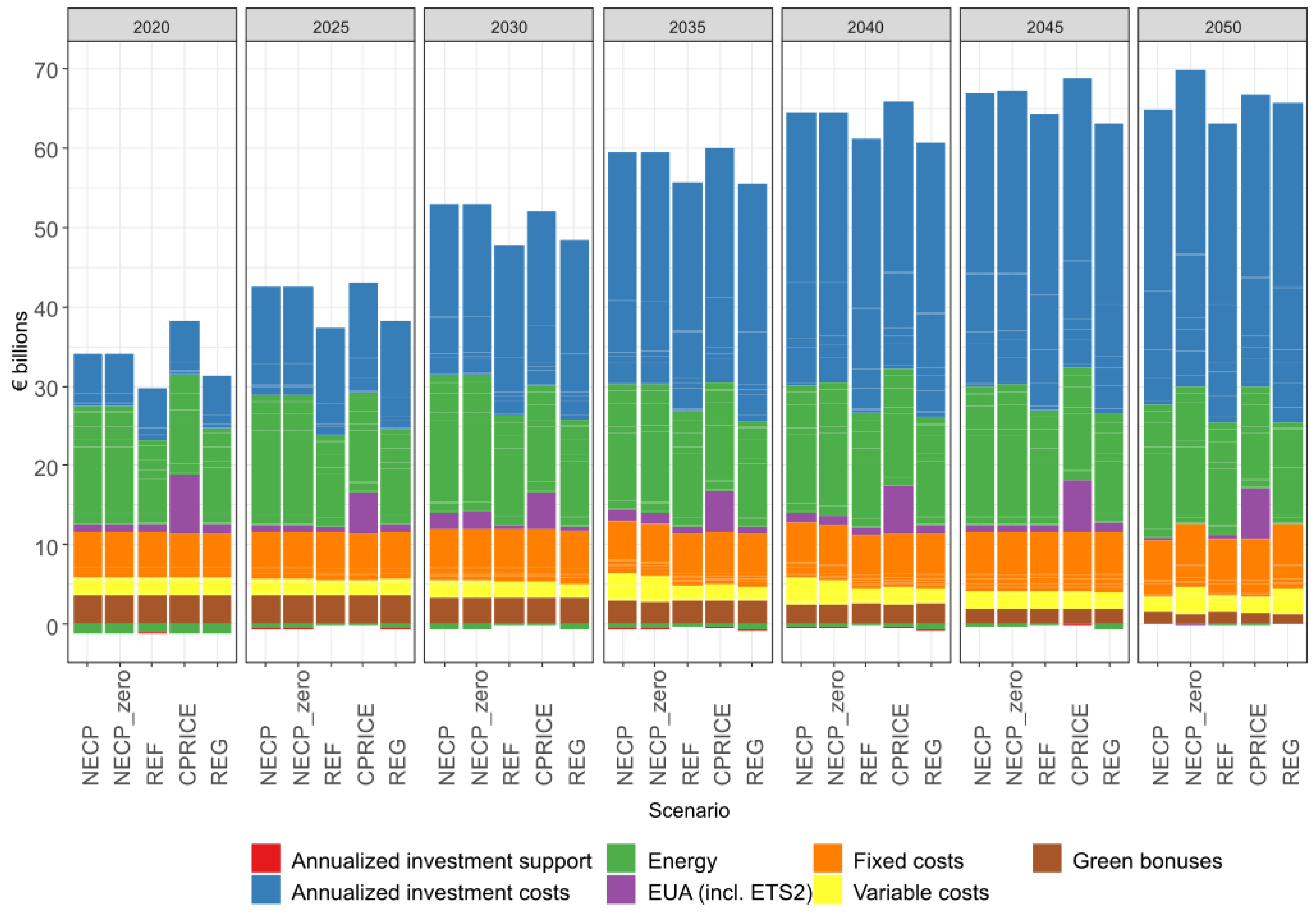

Annualized costs spread the investment costs over time according to the expected lifetime of the investment. In addition to the investment thus spread, energy (fuel) costs, operating costs and the cost of emission allowances are added to the total annualized costs.

Investments before 2020 are not quantified in the model, so energy costs are higher than annualized investment costs until 2025, after which annualized investment costs have the largest share of total annualized costs and account for more than half of total annualized costs in 2050.

Energy costs do not rise significantly over time. The cost of emission allowances (EUAs) differs the most between scenarios. The CPRICE scenario has the highest projected cost of an emission allowance and extends the emission allowance system to transport and buildings from 2030 onwards, therefore it has the highest cost of acquiring EUAs.

Annualized investment support includes support from envisaged subsidy programs. We assume a total volume of investment support for energy savings and new sources of heat and electricity in households and enterprises in the aggregate amount of 20 billion. Previous study on the development of renewable sources in Czechia until 2030 [

33] however showed that even the scenario with the originally planned volume of RES support from the Modernisation Fund of € 2.8 billion does not lead to a greater development of RES than foreseen in the National Plan.

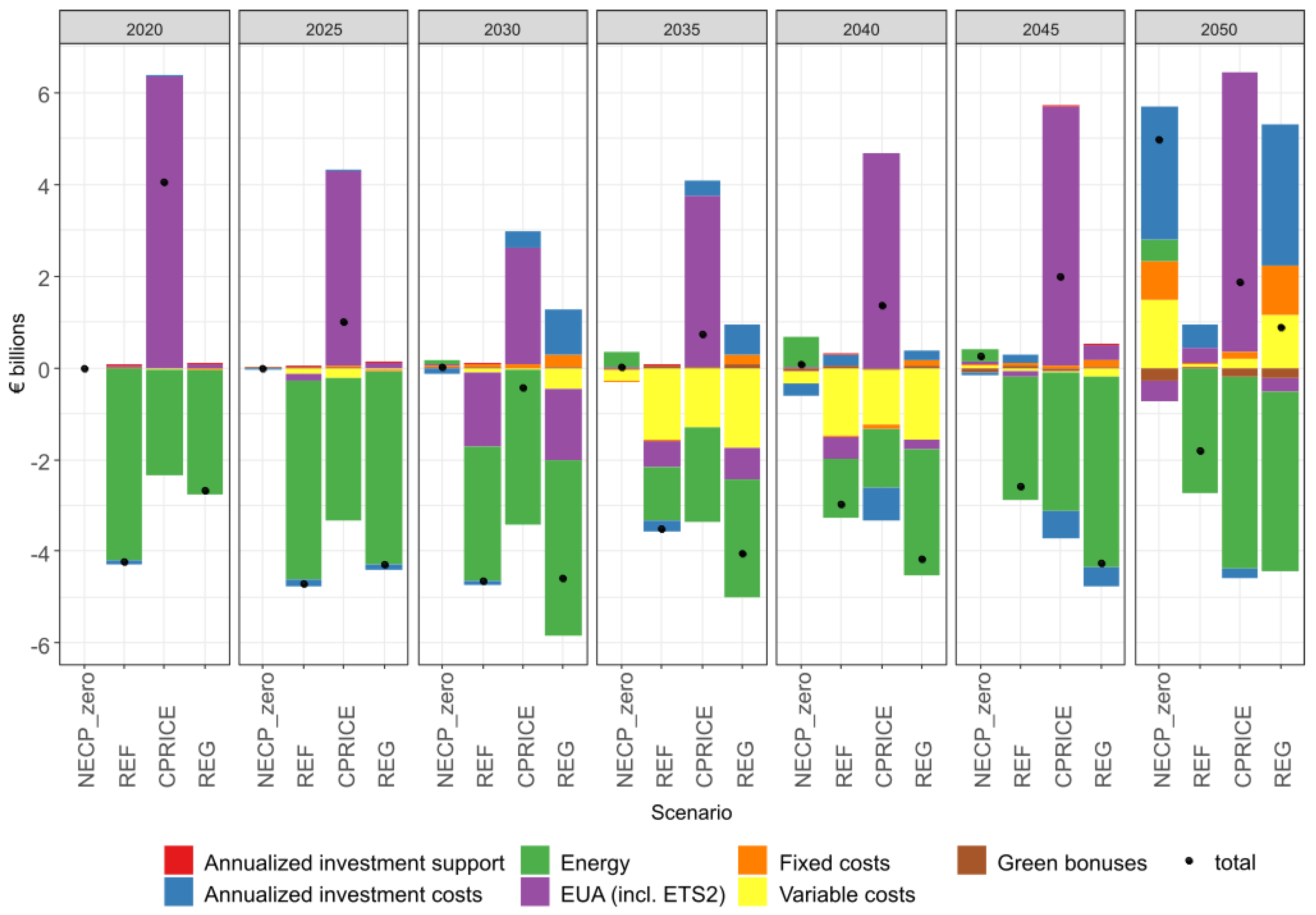

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show the absolute level of annualized costs and their difference from the NECP scenario.

Compared to the NECP scenario, the increased annualized investment, variable and fixed costs (and in the case of the CPRICE scenario also the cost of EUA emission allowances) are at least two-thirds offset by lower energy costs in all scenarios. Energy costs are lower due to lower assumed fossil fuel prices and lower energy consumption compared to the NECP scenario.

4.8. Sensitivity analyses

4.8.1. EUA Price Sensitivity Analysis - NECP and CPRICE Scenarios

A sensitivity analysis on the price of emission allowances (EUAs) is carried out for the NECP reference scenario and for the CPRICE scenario. The current EUA price most closely matches the prices of the 90 and 140 variants or the CPRICE scenario (also used for NECP_C), cf.

Table 9. These options reflect the current situation better than the original EUA price assumption from National Plan, so in a sense they could be said to update the National Plan with respect to the EUA price.

The NECP and CPRICE scenarios (except for the NECP scenario with no additional label as in the first row of

Table 6) differ mainly in the pricing (CPRICE) or non-pricing (NECP) of GHG emissions outside the current EU ETS. In addition, the CPRICE scenarios have a relaxed assumption on net electricity imports and may import up to 20 TWh of electricity per year from 2025 onwards.

We therefore focus mainly on the impact of the EUA price when interpreting the sensitivity analysis (CA).

For the CPRICE scenarios, the highest two projected EUA price trajectories lead to increased electrification, which is reflected in increased consumption of natural gas that is used for electricity generation when GHG emissions are simultaneously captured by CCS. Electricity generation here increases by approximately 15 TWh up to the level of the NECP scenarios. As the EUA price increases, GHG emissions decrease in both the current EU ETS and new ETS2 sector. In the highest EUA price variant (250), GHG emissions in CPRICE_250 fall to 33 MtCO2e in 2050. Even in this variant no new nuclear source is built.

In CPRICE and CPRICE_250 there is a significant deployment of hydrogen-propelled heavy good vehicles around 2050. This additional hydrogen is produced from natural gas using CCS.

In both cases the EUA price has an impact mainly on the cost of electricity and heat production. In the case of CPRICE, it is then reflected in the increased cost of buying emission allowances in ETS2.

In NECP and NECP_90, brown coal is used to a small extent for electricity and heat generation also in 2050. In contrast, in NECP_200 and NECP_250, biomass is replaced by natural gas in hydrogen production (with CCS) and this replaced biomass is used for electricity and heat production with CCS (i.e. providing negative GHG balance there).

The PES consumption responds the most to the emission allowance price in the CPRICE, CPRICE_090 and CPRICE_140 scenarios, due to the extension of the ETS to buildings and road transport.

In electricity and heat generation, the use of natural gas increases at high emission allowance prices, identically in the CPRICE_200, CPRICE_250, NECP_200 and NECP_250 scenarios.

Hydrogen production increases significantly after 2040 in the CPRICE and CPRICE_250 scenarios, dominated by natural gas. In the NECP, NECP_090, NECP_140 and NECP_C scenarios, biomass is dominant for hydrogen production.

4.8.2. Sensitivity of Nuclear Power Plant Construction in the REG Scenario

For the REG scenario, which aims to achieve carbon neutrality in 2050, a sensitivity analysis of the possible development of nuclear power in the Czech Republic is performed.

The most significant impact compared to option REG is the REG_c option, i.e. no extension of the NPP and new nuclear units in 2045 and 2050. Lack of installed capacity in 2035-2045 is replaced mainly by brown coal and natural gas (although brown coal mining is terminated, the necessary coal is imported from neighboring countries). REG_c therefore has the highest GHG emissions in 2030 and 2035 of the options considered.

The REG_o option, with endogenous construction of new nuclear units, installs a total of 160 MW more nuclear units than the REG option, which merely replaces the decommissioned Dukovany NPP.