Submitted:

26 July 2023

Posted:

31 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study location

2.2. Materials

2.3. Preparation of Rice samples

2.4. Phenotypic characterization

2.4.1. Morphological characteristics of the isolates

2.4.2. Physiological and biochemical characterization

- Culture preparation

- Growth at different temperatures

- Growth at different NaCl concentrations

- Gas production with glucose

- Milk coagulation assay

2.5. Carbohydrate fermentation pattern of isolates on API 50 CHL system

2.5.1. Preparation of the culture

2.5.2. Preparation of incubation box

2.5.3. Preparation of the strips

2.5.4. Inoculation of strip

2.5.5. Reading and Interpretation

2.6. Identification of Lactobacillus sp. by 16SrDNA sequencing

2.6.1. Extraction of genomic DNA

2.6.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction for the amplification of 16S rDNA Region

2.6.3. Separation of amplified PCR products

2.6.4. Sequencing and Phylogenic tree development.

3. Results

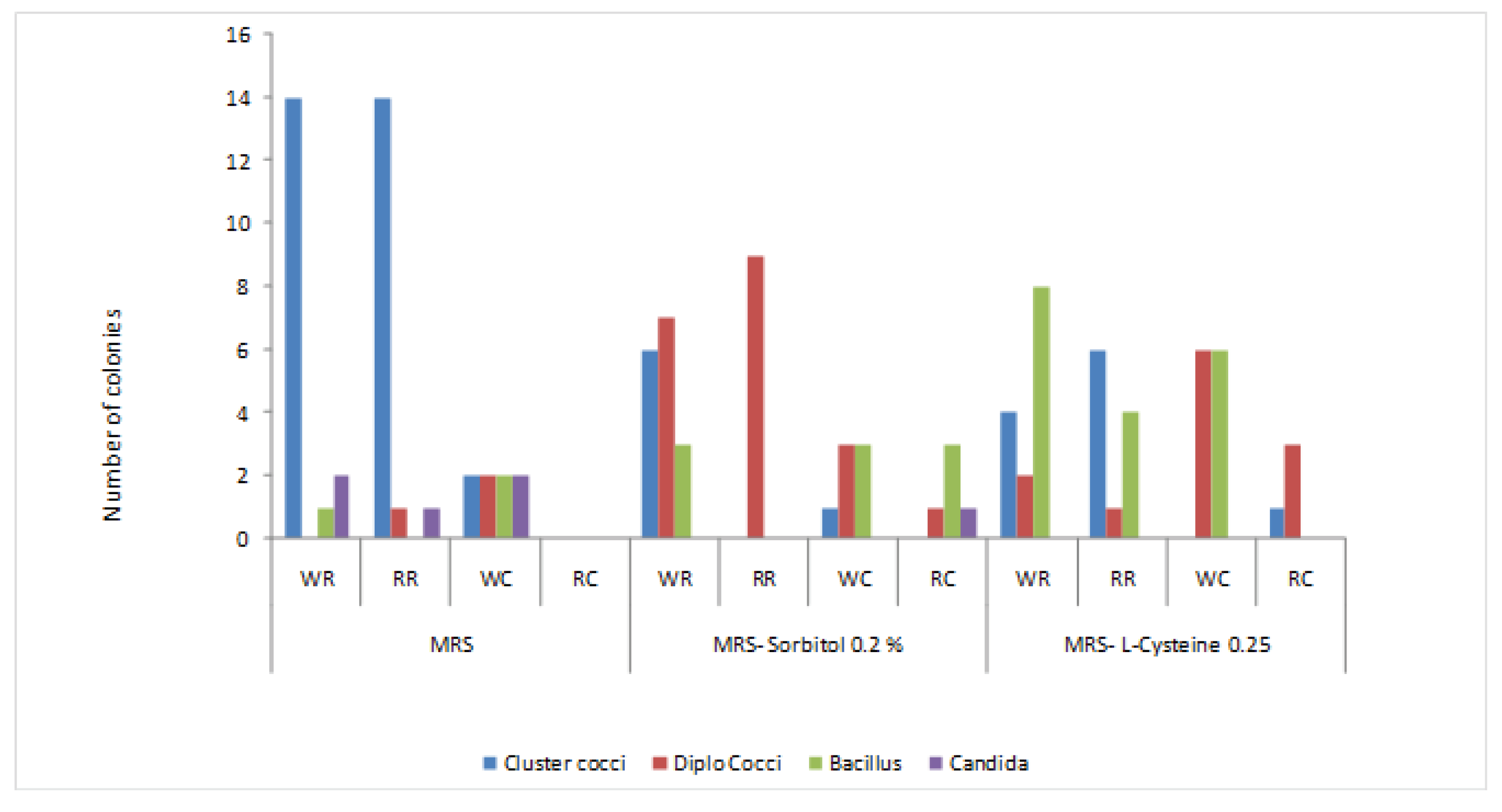

3.1. Morphological characteristics of isolates

3.2. Physiological and biochemical characterization

3.2.1. Growth at different temperatures

3.2.2. Growth at different NaCl concentrations

3.2.3. Gas production with glucose

3.2.4. Milk coagulation and curd formation

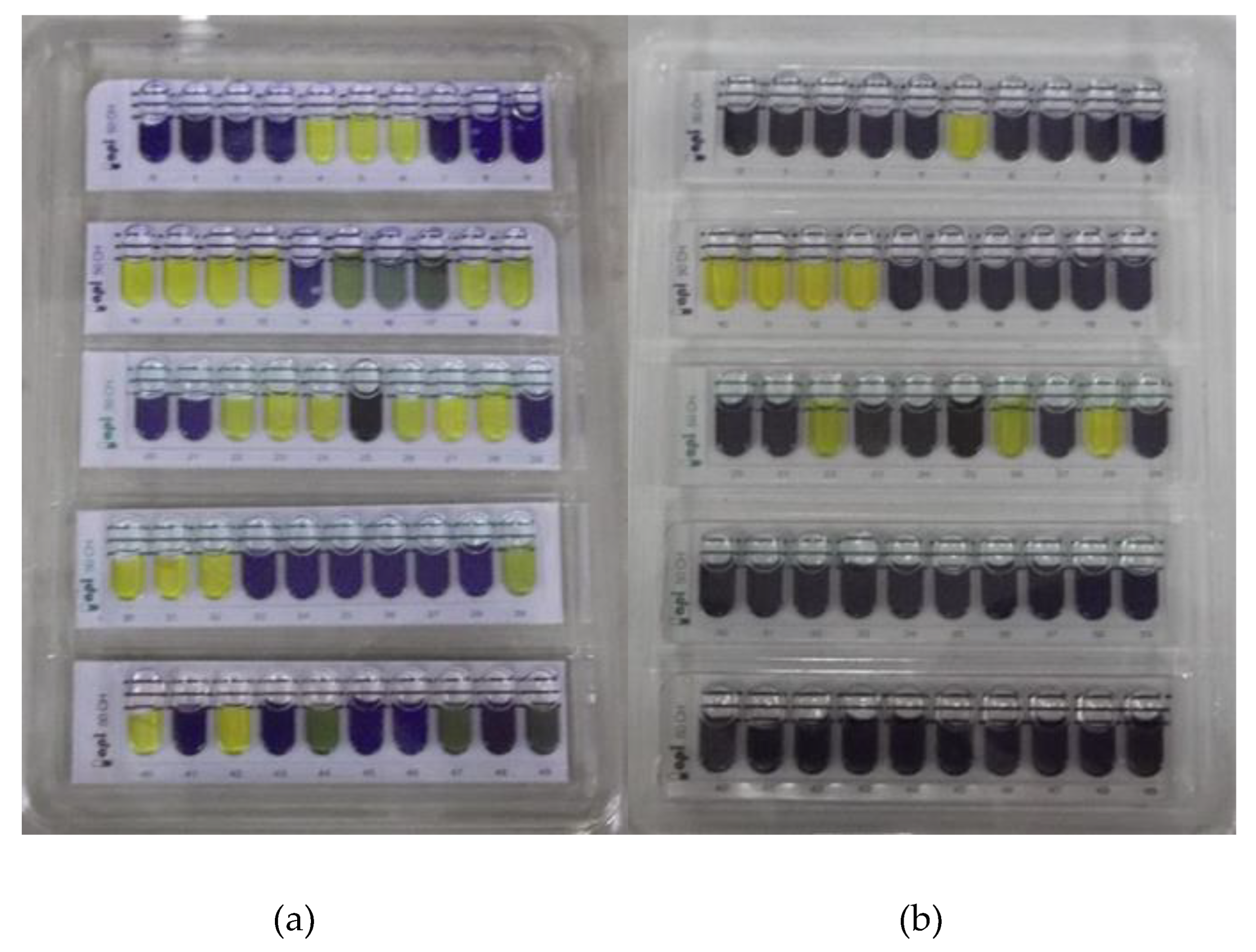

3.2.5. Carbohydrate fermentation pattern of Lactobacillus sp.

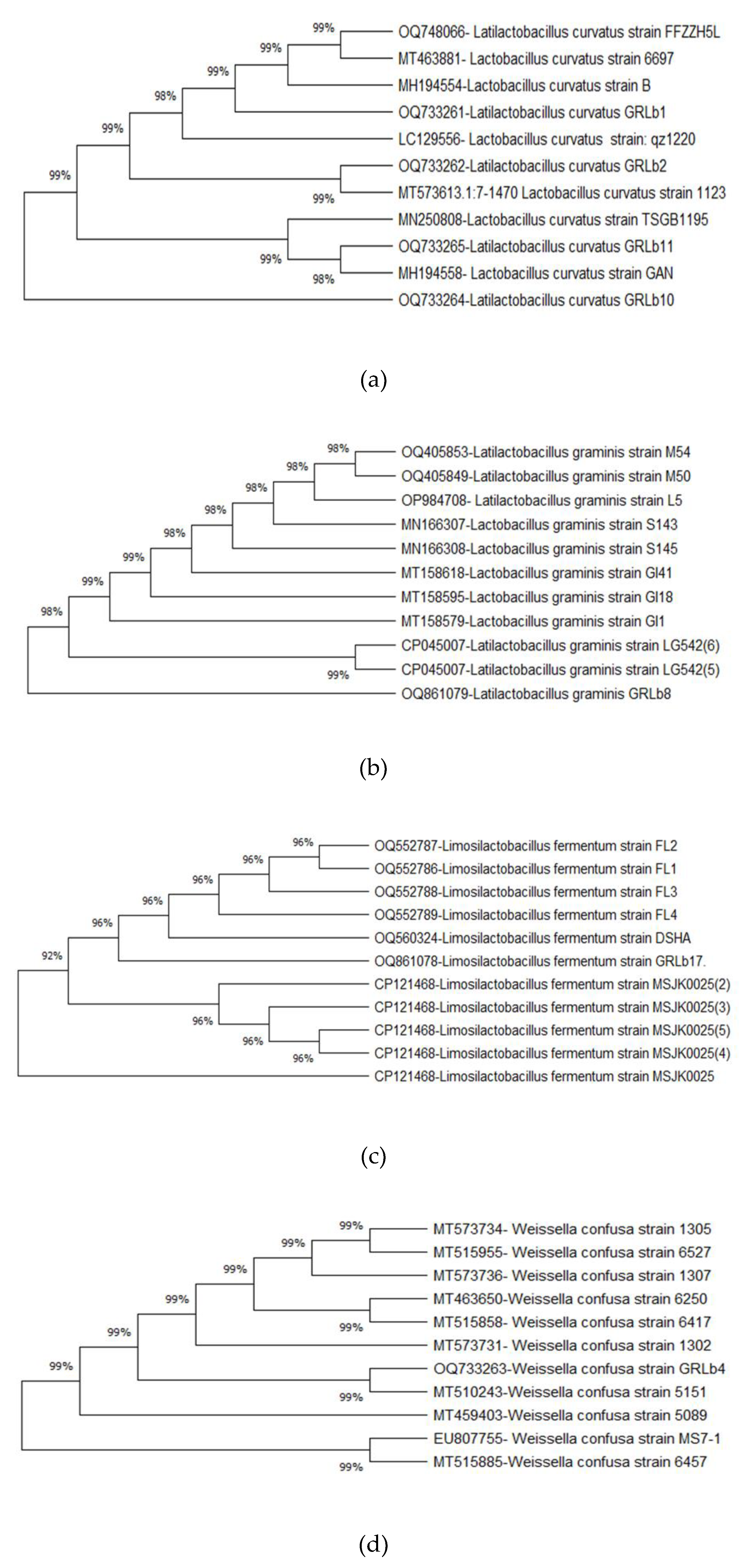

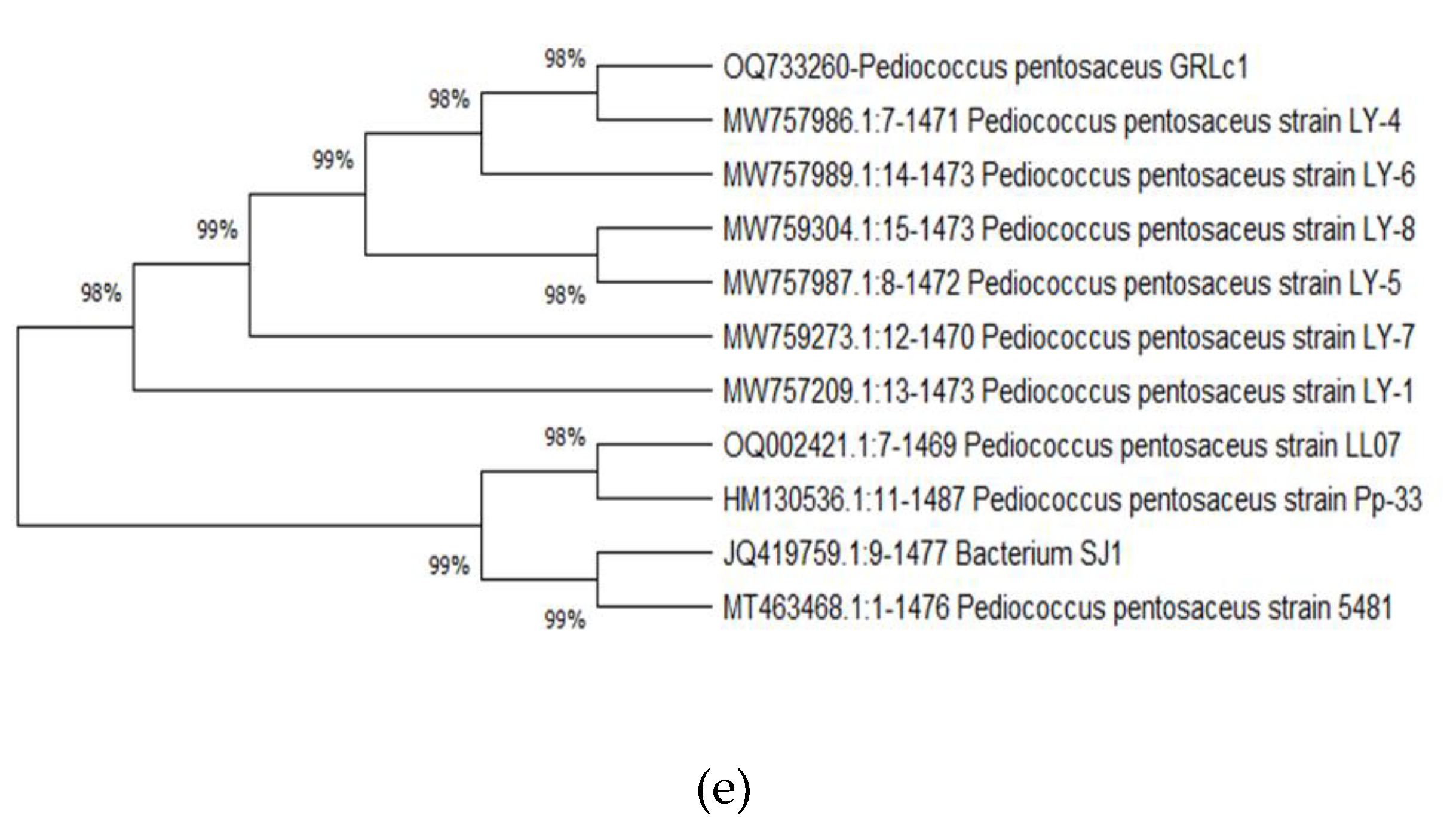

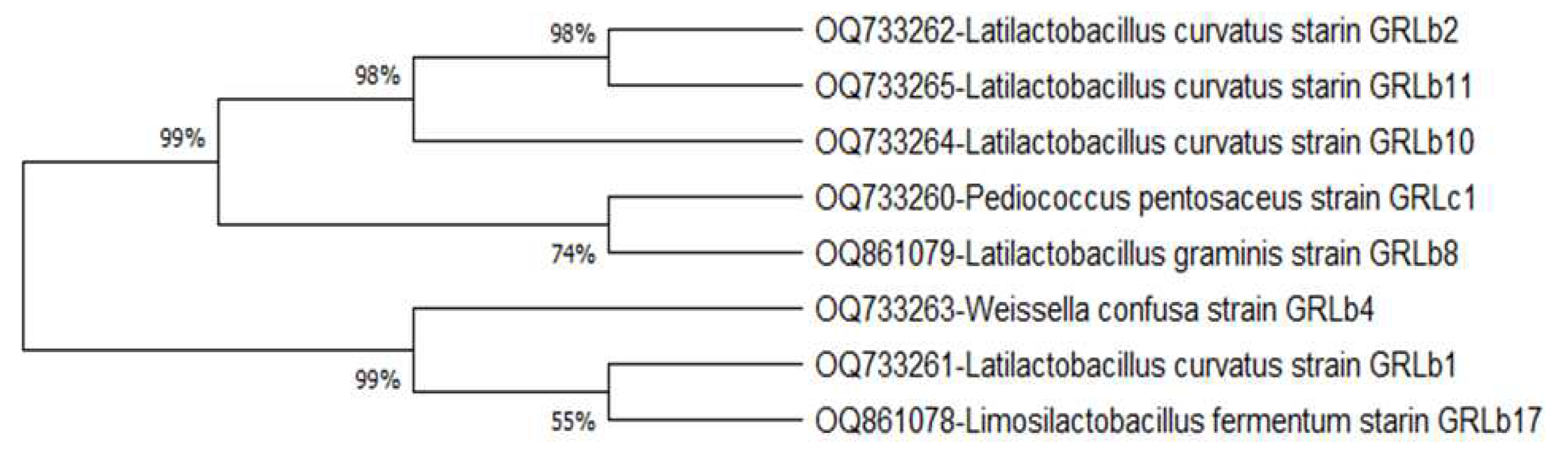

3.3. Molecular identification and genotypic characteristics of Lactobacillus sp.

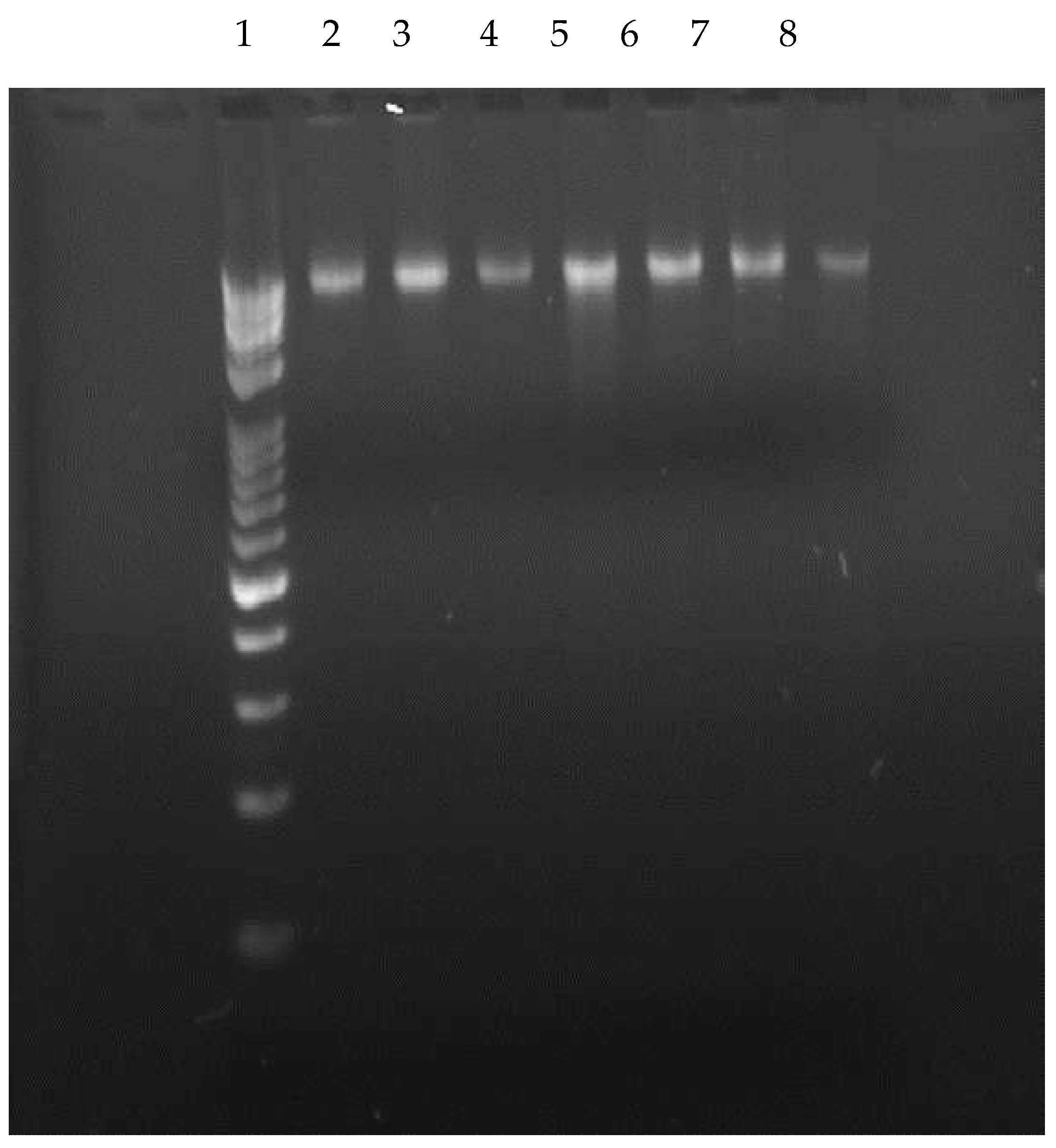

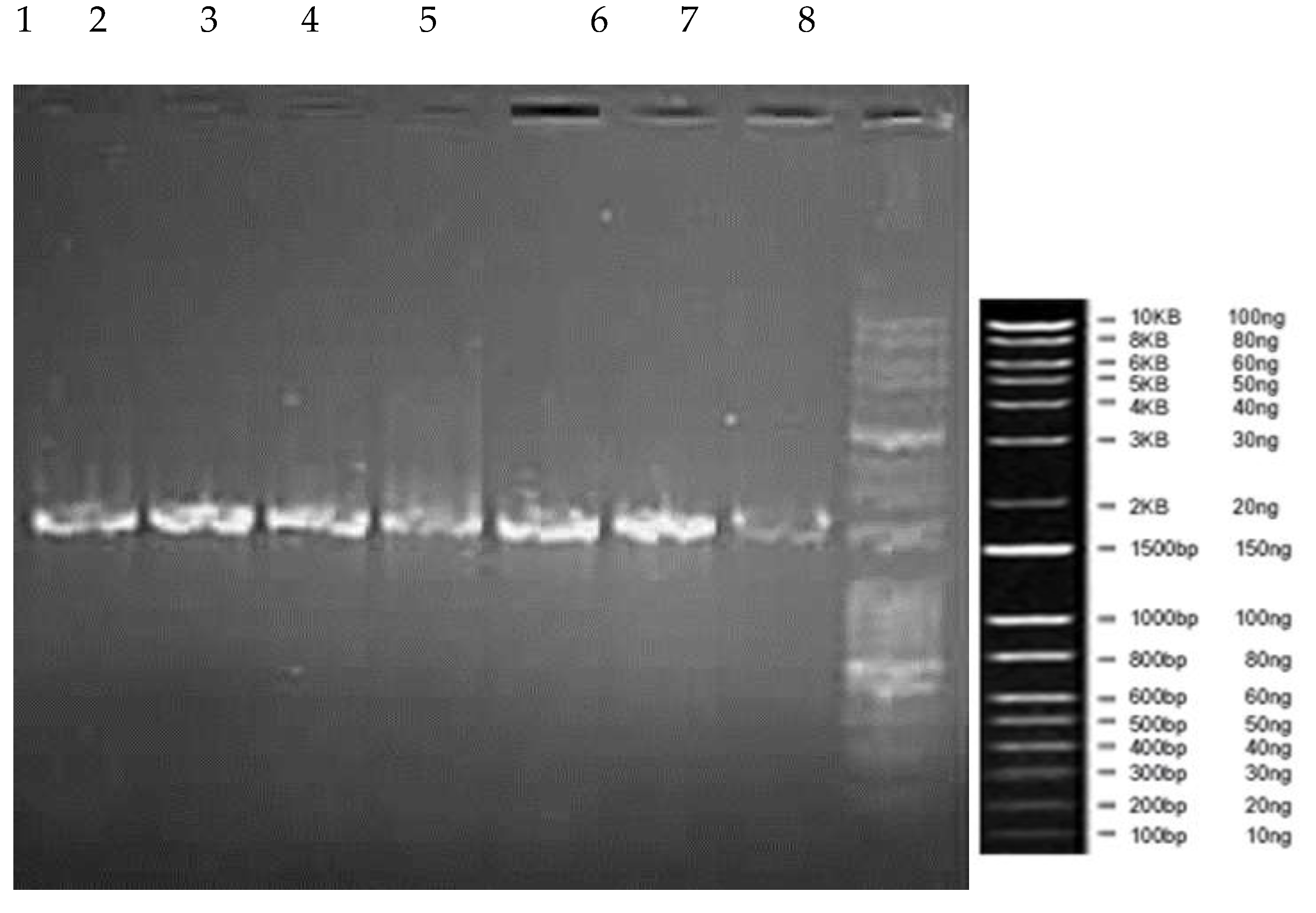

3.3.1. Genomic DNA Isolation

3.3.2. Amplification of 16S rDNA region

3.3.3. Identification of LAB based on phylogenetic analyses of 16S rDNA sequences

3.3.4. Phytogenic tree development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salovaara, H.; Simson, L. Fermented Cereal Based Functional Foods. In Hand Book of Food and Beverage Fermentation Technology; Hui, Y. H., Meunier-Goddik, L., Josephsen, J., Nip, W., Stanfield, P.S., Eds.; CRC press: Marcel Dekker, New York, 2004; p. 831. [Google Scholar]

- Blandinob, A.; Al-Aseeria, M.E.; Pandiellaa, S.S.; Canterob, D.; Webba, C. Review- Cereal-based fermented foods and beverages. Food Res Intern 2003, 36, 27–543. https://comenius.susqu.edu/biol/312/cerealbasedfermentedfoodsandbeverages.pdf.

- Jagadeeswari, S.; Vidya, P.; MukeshKumar, D.J.; Balakumaran, M.D. Isolation and Characterization of Bacteriocin producing Lactobacillus sp from Traditional Fermented Foods. Elect J Environ Agri Food 2010, 9, 575–581. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20103323984.

- Dahiya, D.; Nigam, P.S. Use of Characterized Microorganisms in Fermentation of Non-Dairy-Based Substrates to Produce Probiotic Food for Gut-Health and Nutrition. Fermentation. 2023, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, K.J. Probiotic bacteria in fermented foods: product characteristics and starter organisms. Am J Clin Nutr 2001, 73, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauli, C.M.; Mathara, J.M.; Kutima, P.M. Probiotic potential of spontaneously fermented cereal-based foods – A review. Afr J Biotechnol 2010, 9, 2490–2498. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajb/article/view/79704.

- Kumar, P.; Begum, V.H.; Kumaravel, S. Mineral nutrients of ‘pazhaya sadham’: A traditional fermented food of Tamil Nadu, India. Intern J Nutr Metab 2012, 4, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowsalya, M.; Sudha, K.G.; Ali1, S.; Velmurugan, T.; Karunakaran, G.; Rajeshkumar, M.P. In-vitro assessment of probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from naturally fermented rice gruel of south India. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikeramanayake, T.W. Legumes. In Food and Nutrition. 2nd edition. Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Training Institute: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2002; ISBN: 955-565-000-4,168.

- Hatti-Kaul, R.; Chen, L.; Dishisha, T.; Enshasy, H.E. Lactic acid bacteria: from starter cultures to producers of chemicals. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2018, 365(I20), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, L. Lactic Acid Bacteria Classification and Physiology in Lactic Acid Bacteria Microbiological and Functional Aspects, 3rded.; Salminen, S., Wright, A.V., Ouwehand, A., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, 2004; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyagowri, N.; Parahitiyawa, N.B.; Jeyatilake, J.A.M.S.; Ranadheera, C.S.; Madhujith, M.M.T. Study on Isolation of potentially probiotic Lactobacillus spp from fermented rice. Tropic Agri Res 2015, 26, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, G.H.; Feltham, R.K.A. Cowan and Steel’s Manual for Identification of Medical Bacteria, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1993; p. 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatice, Y.; Isolation, Characterization and determination of probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria from human milk. Thesis for Master of Science. Graduate School of Engineering and Sciences of Izmir Institute of Technology, Turkey. 2007. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/3341345/ (accessed on 16 October 2011).

- Marrokil, A.; Zuniga, M.; Kihal, M.; Martinez, G. Characterization of Lactobacillus from Algerian goats’s milk based on phenotypic, 16SrDNA Sequencing and their technological properties. Braz J Microbiol 2011, 42, 58–171. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 1. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulistiani,; Abinawanto,;Sukara, E.; Salamah, A.;Dinoto, A.; Mangunwardoyo, W. Identification of lactic acid bacteria in sayurasin from Central Java (Indonesia) based on 16S rDNA sequence. Intern Food Res J 2014, 21, 527–532.

- Hall, B.G. Building Phylogenetic Trees from Molecular Data with MEGA. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccalluzzo, A.; Pino., A.; Angelis., M.D.; Bautista-Gallego, J.; Romeo, F.V.; Foti, P.; Caggia, C.; Randazzo, C.L. Effects of Different Stress Parameters on Growth and on Oleuropein-Degrading Abilities of Lactobacillus plantarum Strains Selected as Tailored Starter Cultures for Naturally Table Olives. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunji, E.R.S.; Mierau, I.A.; Poolman, B.; Konings, W.N. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 1996, 70, 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, W.; Coolbear, T.; Sullivan, D.; Mckay, L.L. A deficiency in aspartate biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis C2 causes slow milk coagulation. Appl Environ Microbiol 1998, 64, 1673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quere, F.; Deschamps, A.; Urdaci, M.C. DNA probe and PCR specific reaction for Lactobacillus plantarum. J Appl Microbiol 1997, 82, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrne, S.; Molin, G.; Stahl, S. Plasmids in Lactobacillus strains isolated from meat and meat products. System Appl Microbiol 1989, 11, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.; Abulfazl. Isolation and Molecular Study of Potentially Probiotic Lactobacilli in Traditional White Cheese of Tabriz in Iran. Annals of Biological Research 2012, 3, 2019–2022. [PubMed]

- Patrick, C.Y.; Woo, A.M.Y.; Fung.; Susanna, K.P.L.; Yuen, K.Y. Identification by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing of Lactobacillus salivarius Bacteremic cholecystitis. J Clin Microbiol 2002, 40, 265–267.

- Tilahun, B.; Testaye, A.; Muleta, D; Baihru, A.; Terefework, Z.; Wessel G. Isolation and Molecular Identification of Lactic acid Bacteria using 16srRNA from fermented Teff (Eragrostis tef (Zucc.)) Dough. Intern J Food Sci 2018. [PubMed]

- Holt, J.G.; Krieg, N.R.; Sneath, P.H.A.; Staley, J.T.; Williams, S.T. Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, 9th ed.; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, 1994; pp. 505–542. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, M.Z.; Akter, F.; Hossain, K.M.; Rahman, M.S.M.; Billah, M.M.; Islam, K.M.D. Isolation, Identification and Analysis of Probiotic Properties of Lactobacillus Sp. From Selective Regional Yoghurts. World J Dairy Food Sci 2010, 5, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, M.; Abd El-Aziz, H.; Omran, N.; Anwar, S.; Awad, S.; El-Soda, M. Rep-PCR characterization and biochemical selection of lactic acid bacteria isolated from the Delta area of Egypt. Intern J Food Microbiol 2009, 128, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunajakr, N.; Wongwicharn, W.; Moonmangmee, D. Screening and identification of lactic acid bacteria producing antimicrobial compounds from Pig gastrointestinal Tracts. KMITL Sci Technol J 2008, 8, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Z.; Effat, B.; Magdoub, M.; Tawfik, N.; Sadek, Z.; Mabrouk, A. Molecular Identification of lactic bacteria isolated from fermented dairy product. Intern J Biol Pharm Allied Health Sci 2016, 5, 3221–3230. [Google Scholar]

- Tajabadi, N.; Mardan, M.; Nazamid, S.; Shuhaimi, M.; Bahreini, R.; Manap, M.Y.A. Identification of Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus pentosus and Lactobacillus fermentum from honey stomach of honeybee. Braz J Microbiol 2013, 44, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, S.; Engstrand, L.; Jonsson, H. Lactobacillus gastricus sp. nov., Lactobacillus antri sp. nov., Lactobacillus kalixensis sp. nov. and Lactobacillus ultunensis sp. nov., isolated from human stomach mucosa. Intern J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005, 55, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashiwagi, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kamakura, T. Lactobacillus nodensis sp. nov., isolated from rice bran. Intern J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009, 59, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.; Roos, S. Lactobacillus saerimneri sp. nov isolated from pig faces. Intern J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004, 54, 1365–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brolazo, E.M.; Leite, D.S.; Tiba, M.R.; Villarroel, M.; Marconi, C.; Simoes, J.A. Correlation between API 50CH and Multiple Polymerase Chain Reaction for the identification of Vaginal Lactobacillus in Isolates. Braz J Microbiol 2011, 42, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satishkumar, R.; Ragu-Varman, R.; Kanmani, P.N.; Yuvaraj, N.; Paari, K.A.; Pattukumar, V.; Arul, V. Isolation, Characterization and Identification of a Potential Probiont from South Indian Fermented Foods (Kallappam, Koozh and MorKuzhambu) and Its Use as Biopreservative. Prob Antimicrob Protein 2010, 2, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikanjana, K.; Siriporn, O. Antibacterial and Antioxidant actives of Acid and bile resistant strains of Lactobacillus fermentum isolated from Miang. Braz J Microbio 2009, 40, 757–766. [Google Scholar]

- Jeyagowri, N.; Parahitiyawa, N.B.; Jeyatilake, J.A.M.S.; Ranadheera, C.S.; Madhujith, W.M.T. Antimicrobial activity of potentially probiotic Lactobacillus spp from fermented rice. Proceedings Peradeniya University International Research Sessions (iPURSE 2014) Peradeniya. Sri Lanka, 4–5 July 2014; University of Peradeniya, Sri lanka, 18, p. 182. https://www.pdn.ac.lk/ipurse/2014/proceeding_book/FL/210.pdf.

- Ahmadova, A.; Todorov, S.D.; Hadji-Sfaxi, I.; Choiset, Y.; Rabesona, H.; Messaoudi, S.; Kuliyev, A.; Franco, B.D.; Chobert, J.M.; Haertle, T. Antimicrobial and antifungal activities of Lactobacillus curvatus strain isolated from homemade Azerbaijani cheese. Anaerobe. 2013, 20, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, F.; Favilla, M.; De Bellis, P.; Sisto, A.; Valerio, F. Antifungal activity of strains of lactic acid bacteria isolated from a semolina ecosystem against Penicillium roqueforti, Aspergillus niger and Endomyces fibuliger contaminating bakery products. Systemic Appl Microbiol 2013, 32, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divisekera, D.M.W.D.; Gooneratne, J.; Jayawardana, D. Isolation and characterization and identification of Lactic acid bacteria and yeast from fermented organically grown rice and coconut milk. In: Proceedings Peradeniya University International Research Sessions (iPURSE 2014) Peradeniya. Sri Lanka, 4–5 July 2014; University of peradeniya, Sri lanka,.18, pp. 210. https://www.pdn.ac.lk/ipurse/2014/proceeding_book/FL/210.pdf.

- Sukumar, G.; Ghosh, A.R. Pediococcus spp. – A potential probiotic isolated from Khadi (an Indian fermented food) and identified by 16SrDNA sequence analysis. Afr J Food Sci 2010, 4, 597–602. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, H.; Kim, Y.-T.; Jang, W.Y.; Kim, J.-Y.; Heo, K.; Shim, J.-J.; Lee, J.-L.; Yang, D.-C.; Kang, S.C. Effects of Lactobacillus curvatus HY7602-Fermented Antlers in Dexamethasone-Induced Muscle Atrophy. Fermentation 2022, 8, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Qiao,; Xiao,; Tian,; Zhao, J.; Zhang,H.; Chen,W.; Zhai.O. Latilactobacillus curvatus: A Candidate Probiotic with Excellent Fermentation Properties and Health Benefits. Foods 2020, 9, 1336. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32993033/.

- Bernard, D.; Jeyagowri, N.; Madhujith, T. Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria isolated from Idli Batter and their susceptibility to Antibiotics. Tropical Agricultural Research 2021, 32, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adikari, A.M.M.U.; Priyashantha, H.; Disanayaka, J.N.K.; Jayatileka, D.V.; Kodithuwakku, S.P.; Jayatilake, J.A.M.S.; Vidanarachchi, J.K. Isolation, identification and characterization of Lactobacillus species diversity from Meekiri: traditional fermented buffalo milk gels in Sri Lanka. Heliyon 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Isolates | Morphological description | Appearance under light microscope (x1000 magnification) |

|---|---|---|

| Latilactobacillus curvatus strain GRLb1 | Medium size, Rod (regular)shaped bacteria, arranged as single /pair or group in ‘V’ arrangement | |

| Latilactobacillus curvatus strain GRLb2 | Medium size, Rod (regular)shaped bacteria, arranged as single /pair or group in ‘V’ arrangement | |

| Weissella confusa strain GRLb4 | Very long size, Rod (regular)shaped bacteria, arranged as single /pair or group in ‘V’ arrangement | |

| Latilactobacillusgraminis strain GRLb8 | Small size, Rod (regular)shaped bacteria, arranged as single /pair or group in ‘V’ arrangement | |

| Latilactobacillus curvatus strain GRLb10 | Medium size, Rod (regular)shaped bacteria, arranged as single /pair or group in ‘V’ arrangement | |

| Latilactobacillus curvatus strain GRLb11 | Medium size, Rod (regular)shaped bacteria, arranged as single /pair or group in V arrangement | |

| Limosilactobacillusfermentum strain GRLb17 | Long size, Rod (regular)shaped bacteria, arranged as single /pair or group in V arrangement | |

| Pediococcus pentosaceus strain GRLc1 | Coccus shaped bacteria, arranged as single, tetrad, group/ cluster |

| Physiological and biochemical characteristics | Lb-1 | Lb-2 | Lb-4 | Lb-8 | Lb-10 | Lb-11 | Lb-17 | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram test | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | NA |

| Catalase test | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | NA | NA |

| Motility | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | NA | NA |

| Spore formation | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | NA | NA |

| Gas from glucose | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | ND | - |

| Growth at 10°C | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | NA | - |

| Growth at 37°C | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | - |

| Growth at 40°C | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | NA | - |

| Growth at 45°C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | - |

| Growth at 55°C | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | NA | - |

| 0% Nacl | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| 2% NaCl | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | NA | - |

| 4% NaCl | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | NA | - |

| 6.5% NaCl | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | NA | - |

| 10% NaCl | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | NA | - |

| Milk coagulation | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Isolate code | Species of Lactobacillus | *Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lb-1 | Lactobacillus curvatus ssp.curvatus | 98.9 |

| Lb-2 | Lactobacillus curvatus ssp.curvatus | 99.3 |

| Lb-4 | Lactobacillus helveticus | 86.3 |

| Lb-8 | Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. delbrueckii | 95.5 |

| Lb-10 | Lactobacillus pentosus | 63.3 |

| Lb-11 | Lactobacillus curvatus ssp.curvatus | 99.3 |

| Lb-17 | Lactobacillus plantrum | 91.3 |

| Lc-1 | Pediococcus pentosaceus | 99.9 |

| Sequence ID | Microorganism | Accession Number | Sequence length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lb1 | Latilactobacillus curvatus GRLb1 | OQ733261 | 1475 bp |

| Lb2 | Latilactobacillus curvatus GRLb2 | OQ733262 | 1465 bp |

| Lb4 | Weissella confusa strain GRLb4 | OQ733263 | 1486 bp |

| Lb8 | Latilactobacillus graminis GRLb8 | OQ861079 | 1097 bp |

| Lb10 | Latilactobacillus curvatus GRLb10 | OQ733264 | 1469 bp |

| Lb11 | Latilactobacillus curvatus GRLb11 | OQ733265 | 1456 bp |

| Lb17 | Limosilactobacillus fermentum GRLb17 | OQ861078 | 819 bp |

| Lc1 | Pediococcus pentosaceus GRLc1 | OQ733260 | 1480 bp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).