Submitted:

27 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

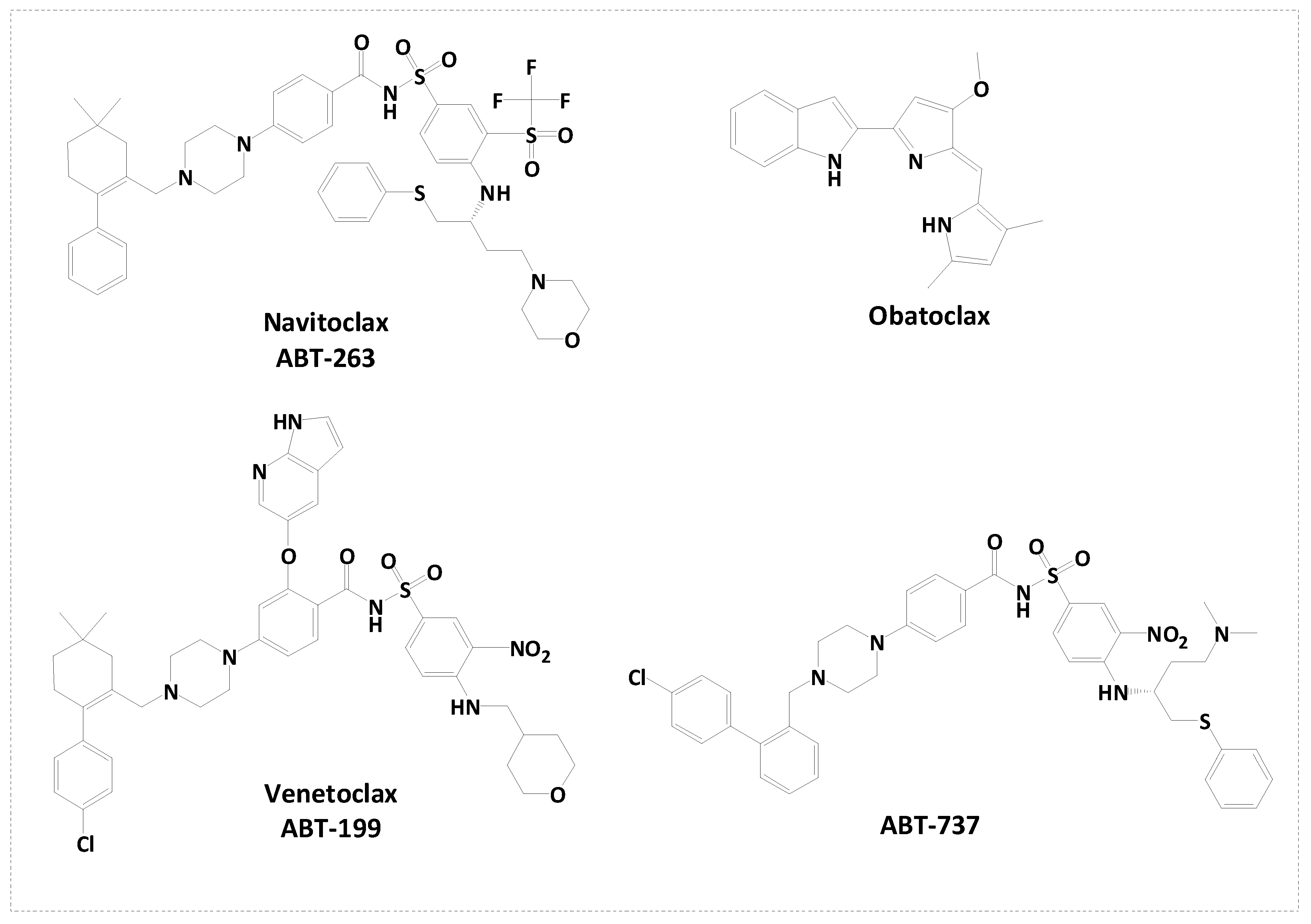

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

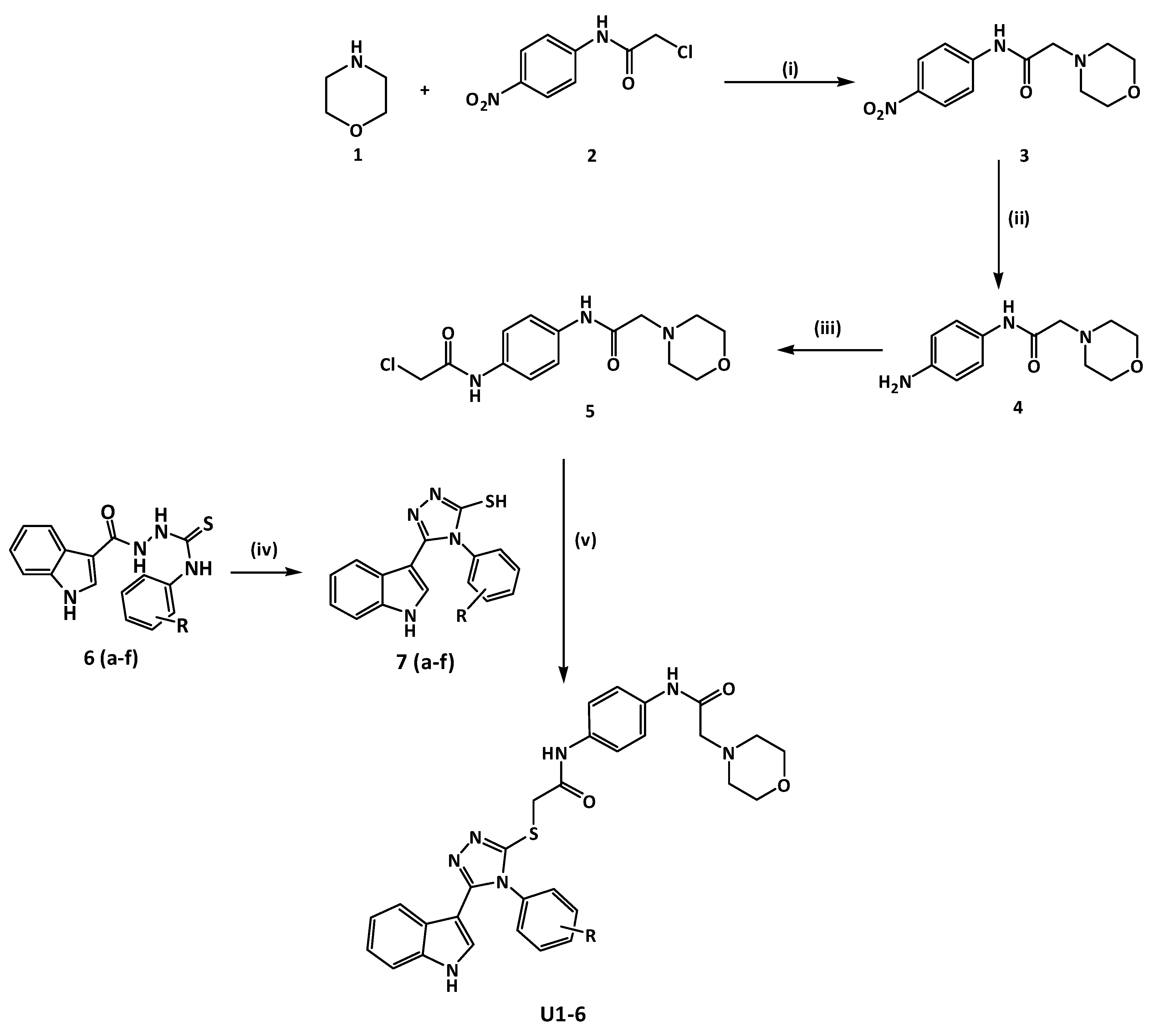

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. Synthesis of 2-chloro-N-(4-nitrophenyl)acetamide (2)

2.1.2. Synthesis of 2-morpholin-4-yl-N-(4-nitrophenyl)acetamide (3)

2.1.3. Synthesis of N-(4-amino-phenyl)-2-morpholin-4-yl-acetamide (4)

2.1.4. N-[4-(2-chloroacetylamino)phenyl]-2-morpholin-4-yl-acetamide (5)

2.1.5. General procedure for triazole thiol (7a-f) preparation

2.1.6. General procedure of S alkylation of triazole thiol (U1-6)

2.2. Biology

2.2.1. Cell culture and maintenance

2.2.2. Cytotoxicity assay

2.2.3. Cell cycle assay

2.2.4. Apoptosis Assay

2.2.5. Bim Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.3. Computational modeling

2.3.1. Protein and ligand preparation

2.3.2. Grid generation and molecular docking

2.3.3. Pharmacokinetics predication

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

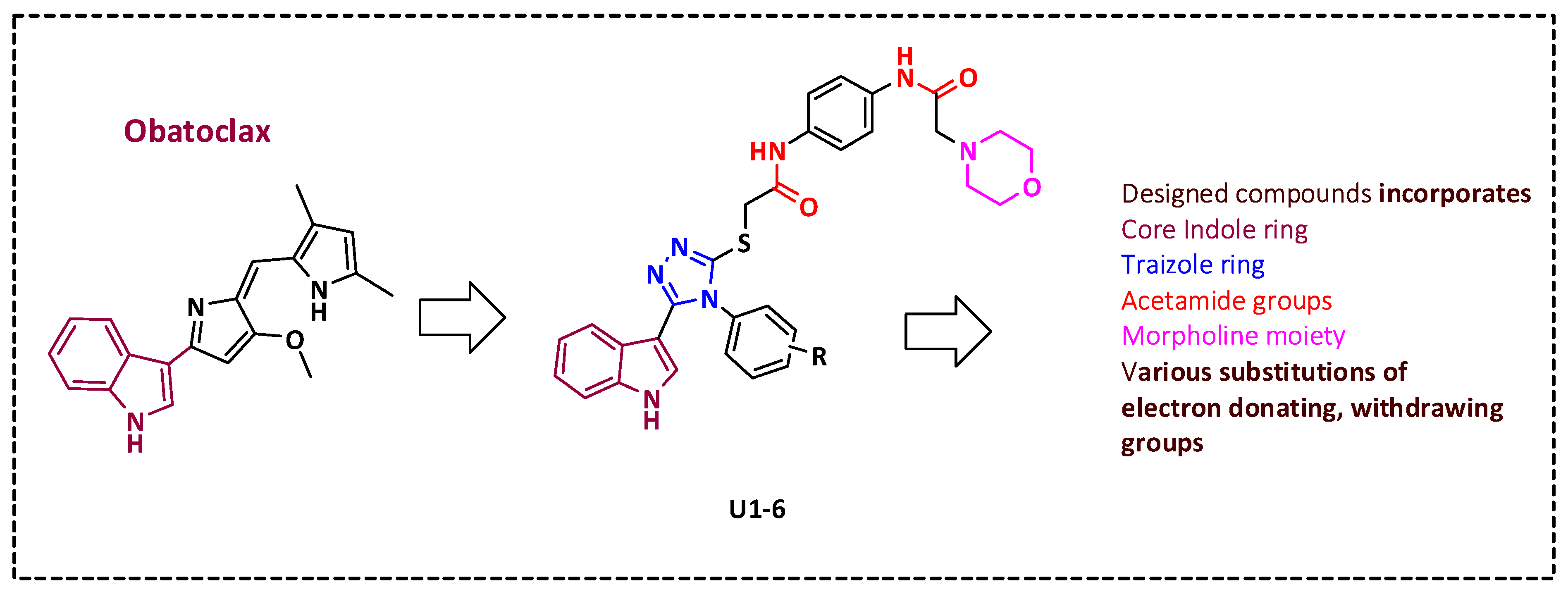

3.1. Rational design

3.2. Synthesis of the title compounds U1-6

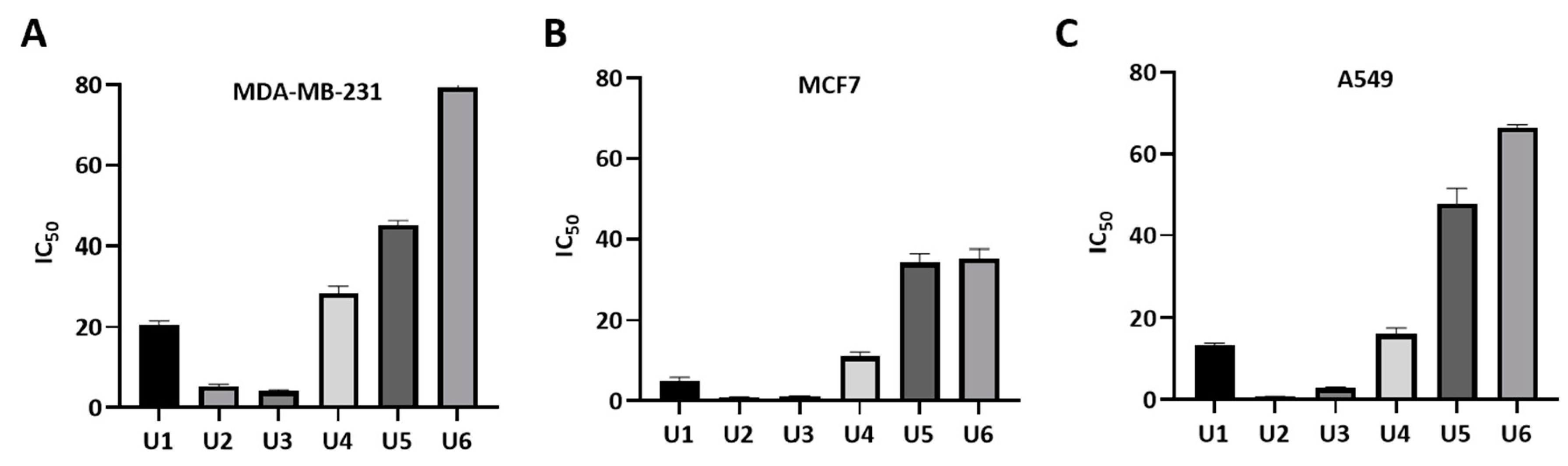

3.3. Compounds U2 and U3 showed potent inhibitory activity towards Bcl-2- expressing cancer cells

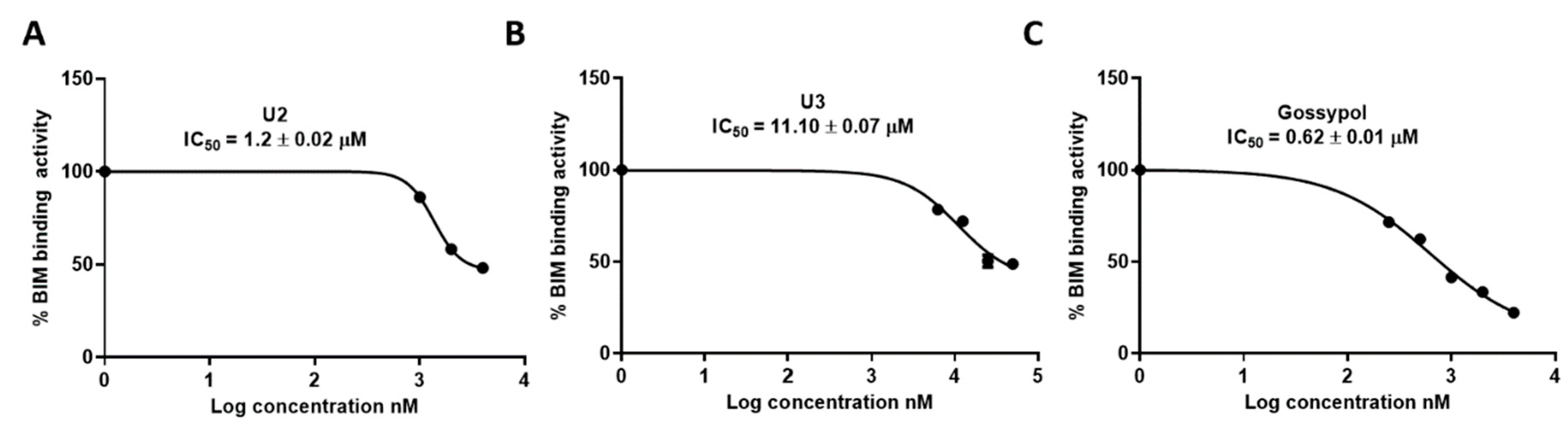

3.4. ELISA indicated the superior activity of compound U2 against Bcl-2 protein

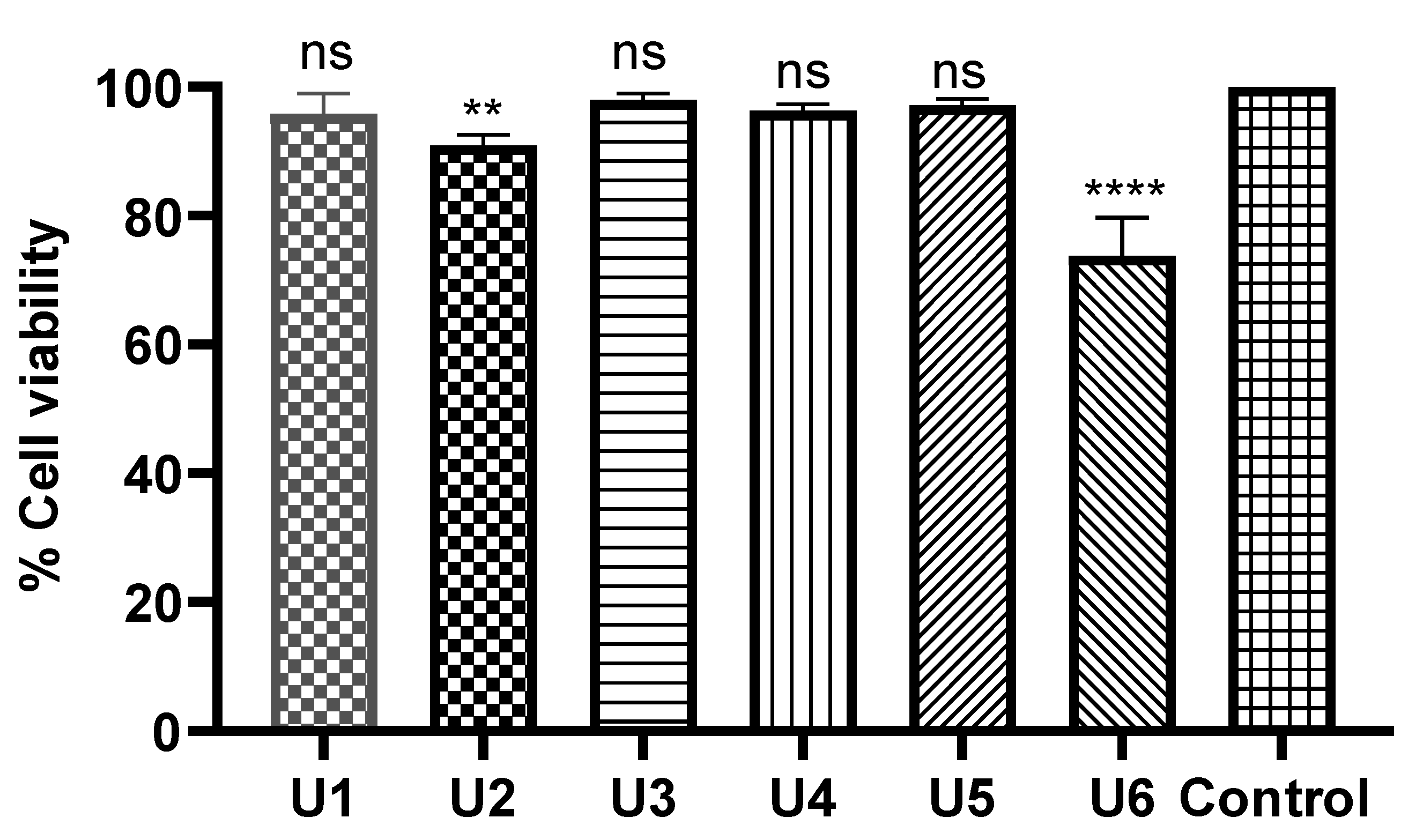

3.5. Compounds U1-6 showed an excellent safety prolife on human normal cells.

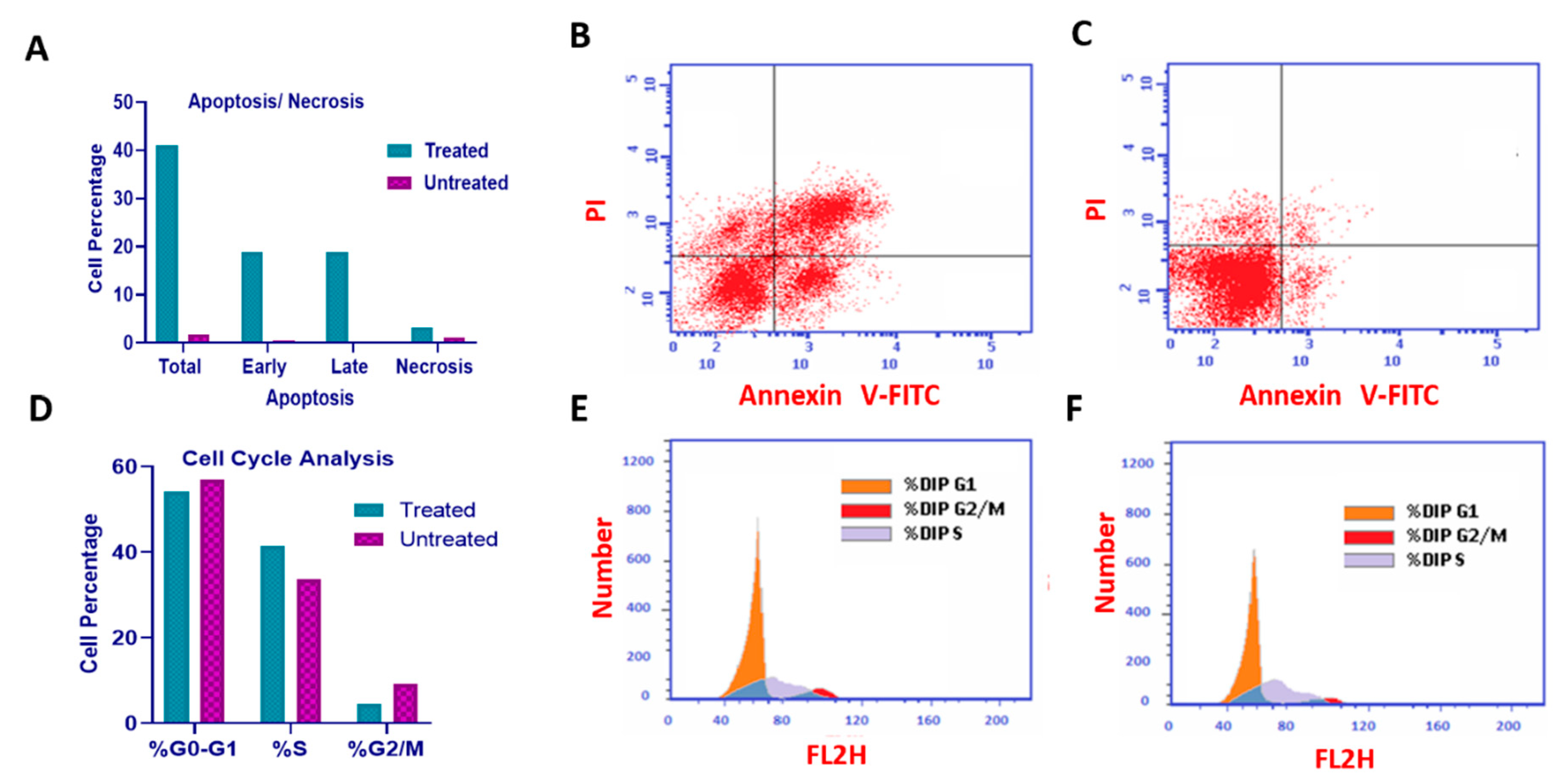

3.6. Compound U2 induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest at G1/S phase.

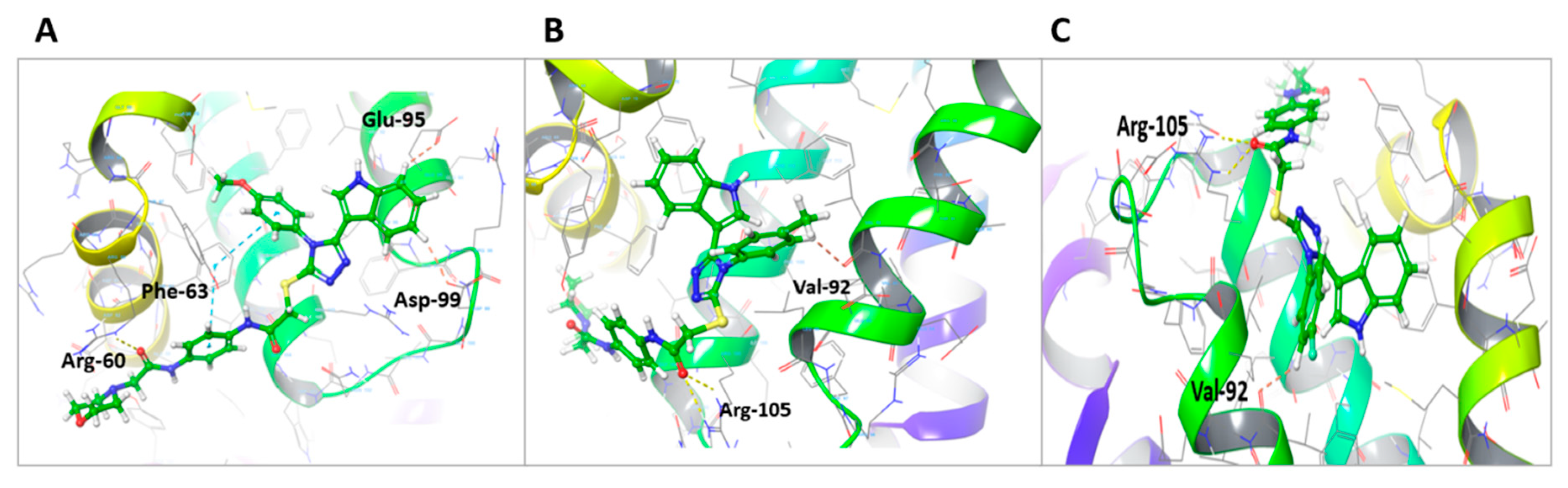

3.7. Molecular docking revealed efficacy and selectivity of U2 compound against Bcl-2

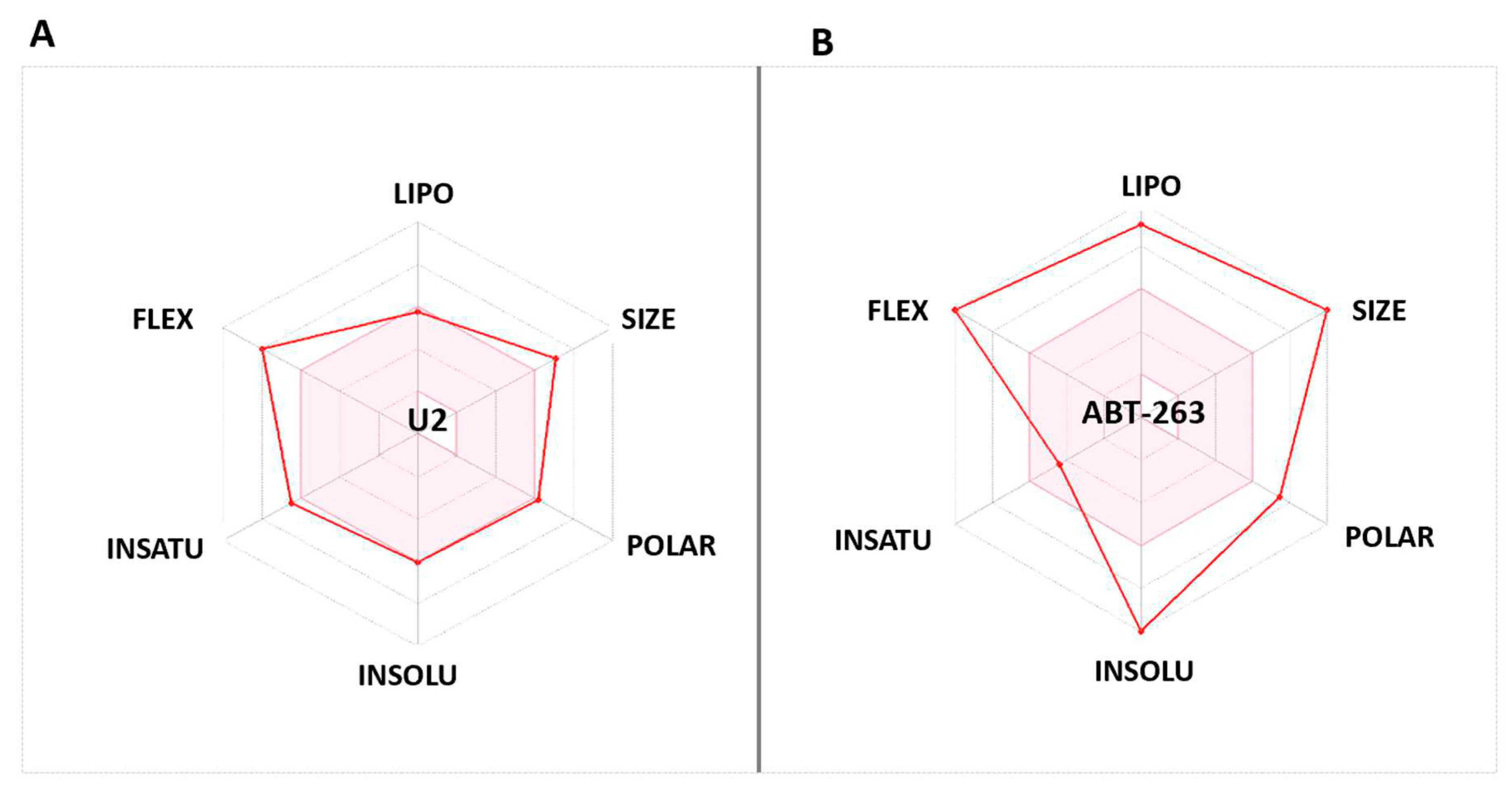

3.8. Compound U2 showed improved properties compared to small molecule inhibitor ABT263.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of interest

References

- Aniogo, E.C., B.P.A. George, and H. Abrahamse, Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in photodynamic therapy mediated cell survival and regulation. Molecules, 2020. 25(22): p. 5308. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, R., et al., New quinoline-based heterocycles as anticancer agents targeting bcl-2. Molecules, 2019. 24(7): p. 1274. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, R., et al., Design, synthesis and evaluation of new bioactive oxadiazole derivatives as anticancer agents targeting bcl-2. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020. 21(23): p. 8980. [CrossRef]

- Kaloni, D. , et al., BCL-2 protein family: Attractive targets for cancer therapy. Apoptosis, 2023. 28(1-2): p. 20-38. [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.A. , et al., Bcl-x short-isoform is essential for maintaining homeostasis of multiple tissues. Iscience, 2023. 26(4): p. 106409. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.H. and C.P. Reynolds, Bcl-2 inhibitors: targeting mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in cancer therapy. Clinical cancer research, 2009. 15(4): p. 1126-1132. [CrossRef]

- Longley, D. and P. Johnston, Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 2005. 205(2): p. 275-292.

- Mohammad, R.M., et al. Broad targeting of resistance to apoptosis in cancer. in Seminars in cancer biology. 2015. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. , et al., Targeting the Bcl-2 family for cancer therapy. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets, 2013. 17(1): p. 61-75. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S. , et al., Downregulation of autophagy by Bcl-2 promotes MCF7 breast cancer cell growth independent of its inhibition of apoptosis. Cell Death & Differentiation, 2011. 18(3): p. 452-464. [CrossRef]

- Akar, U. , et al., Silencing of Bcl-2 expression by small interfering RNA induces autophagic cell death in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Autophagy, 2008. 4(5): p. 669-679. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.G. , et al., Microarray determination of Bcl-2 family protein inhibition sensitivity in breast cancer cells. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 2013. 238(2): p. 248-256. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , et al., Curcumin inhibits human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell proliferation through regulation of Bcl-2/Bax and cytochrome C. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2013. 14(8): p. 4599-4602.

- Xiong, S. , et al., MicroRNA-7 inhibits the growth of human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells through targeting BCL-2. International journal of biological sciences, 2011. 7(6): p. 805. [CrossRef]

- Lima, K. , et al., Obatoclax reduces cell viability of acute myeloid leukemia cell lines independently of their sensitivity to venetoclax. Hematology, Transfusion and Cell Therapy, 2022. 44: p. 124-127. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, P.T. , et al., Guardians of cell death: the Bcl-2 family proteins. Essays in biochemistry, 2003. 39: p. 73-88. [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.F., M.W. Wong-Brown, and N.A. Bowden, BCL-2 family isoforms in apoptosis and cancer. Cell death & disease, 2019. 10(3): p. 177. [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, N., C. Liao, and Z. Nikolovska-Coleska, Inhibitors of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins: a patent review. Expert opinion on therapeutic patents, 2012. 22(1): p. 37-55. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, B.A. and W.S. El-Deiry, Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nature reviews Clinical oncology, 2020. 17(7): p. 395-417. [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. , Pioneering apoptosis-targeted cancer drug poised for FDA approval: AbbVie's BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax--the leading small-molecule protein-protein interaction inhibitor--could soon become the first marketed drug to directly target the ability of cancer cells to evade apoptosis. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2016. 15(3): p. 147-150.

- King, A.C. , et al., Venetoclax: a first-in-class oral BCL-2 inhibitor for the management of lymphoid malignancies. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 2017. 51(5): p. 410-416. [CrossRef]

- Korycka-Wolowiec, A. , et al., Venetoclax in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, 2019. 15(5): p. 353-366. [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, C.D. , et al., Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 2020. 383(7): p. 617-629.

- Mason, K.D. , et al., In vivo efficacy of the Bcl-2 antagonist ABT-737 against aggressive Myc-driven lymphomas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2008. 105(46): p. 17961-17966. [CrossRef]

- Tse, C. , et al., ABT-263: a potent and orally bioavailable Bcl-2 family inhibitor. Cancer research, 2008. 68(9): p. 3421-3428. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. , et al., The Bcl-2/Bcl-XL/Bcl-w Inhibitor, Navitoclax, Enhances the Activity of Chemotherapeutic Agents In Vitro and In VivoNavitoclax Enhances the Activity of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 2011. 10(12): p. 2340-2349.

- Gandhi, L. , et al., Phase I study of Navitoclax (ABT-263), a novel Bcl-2 family inhibitor, in patients with small-cell lung cancer and other solid tumors. Journal of clinical oncology, 2011. 29(7): p. 909. [CrossRef]

- Tolcher, A.W. , et al., Safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of navitoclax (ABT-263) in combination with erlotinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology, 2015. 76: p. 1025-1032. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, S.M. , et al., Phase I study of obatoclax mesylate (GX15-070), a small molecule pan–Bcl-2 family antagonist, in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 2009. 113(2): p. 299-305. [CrossRef]

- Bose, P., V. Gandhi, and M. Konopleva, Pathways and mechanisms of venetoclax resistance. Leukemia & lymphoma, 2017. 58(9): p. 2026-2039. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, R. , et al., Synthesis and evaluation of 5-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-aryl-1, 3, 4-oxadiazol-2-amines as Bcl-2 inhibitory anticancer agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2017. 27(4): p. 1037-1040. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, R. , et al., New bioactive fused triazolothiadiazoles as Bcl-2-targeted anticancer agents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. 22(22): p. 12272. [CrossRef]

- Ziedan, N.I. , et al., Virtual screening, SAR, and discovery of 5-(indole-3-yl)-2-[(2-nitrophenyl) amino][1, 3, 4]-oxadiazole as a novel Bcl-2 inhibitor. Chemical biology & drug design, 2017. 90(1): p. 147-155.

- Chan, G.K.Y. , et al., A simple high-content cell cycle assay reveals frequent discrepancies between cell number and ATP and MTS proliferation assays. PloS one, 2013. 8(5): p. e63583. [CrossRef]

- Vertrees, R.A. , et al., Synergistic interaction of hyperthermia and gemcitabine in lung cancer. Cancer biology & therapy, 2005. 4(10): p. 1144-1153. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, R. , et al., Synthesis and evaluation of 3-(benzylthio)-5-(1H-indol-3-yl)-1, 2, 4-triazol-4-amines as Bcl-2 inhibitory anticancer agents. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters, 2013. 23(8): p. 2391-2394. [CrossRef]

- Shelley, J.C. , et al., Epik: a software program for pK a prediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules. Journal of computer-aided molecular design, 2007. 21(12): p. 681-691. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, J.R. , et al., Towards the comprehensive, rapid, and accurate prediction of the favorable tautomeric states of drug-like molecules in aqueous solution. Journal of computer-aided molecular design, 2010. 24(6): p. 591-604. [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, R. , et al., Iterated virtual screening-assisted antiviral and enzyme inhibition assays reveal the discovery of novel promising anti-SARS-CoV-2 with dual activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. 22(16): p. 9057.

- Giardina, S.F. , et al., Novel, Self-Assembling Dimeric Inhibitors of Human β Tryptase. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 2020. 63(6): p. 3004-3027.

- Hamdy, R. , et al., Efficient selective targeting of Candida CYP51 by oxadiazole derivatives designed from plant cuminaldehyde. RSC Medicinal Chemistry, 2022. 13(11): p. 1322-1340. [CrossRef]

- Halgren, T.A. , et al., Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 2004. 47(7): p. 1750-1759.

- Friesner, R.A. , et al., Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 2004. 47(7): p. 1739-1749.

- Daina, A., O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Scientific reports, 2017. 7: p. 42717. [CrossRef]

- Alzaabi, M.M. , et al., Flavonoids are promising safe therapy against COVID-19. Phytochemistry Reviews, 2021: p. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Bang, S. , et al., Azaphilones from an endophytic Penicillium sp. prevent neuronal cell death via inhibition of MAPKs and reduction of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. Journal of Natural Products, 2021. 84(8): p. 2226-2237.

- Kamath, P.R. , et al., Indole-coumarin-thiadiazole hybrids: An appraisal of their MCF-7 cell growth inhibition, apoptotic, antimetastatic and computational Bcl-2 binding potential. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2017. 136: p. 442-451. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, M.I. , et al., Design, synthesis, anticancer activity, and solid lipid nanoparticle formulation of indole-and benzimidazole-based compounds as pro-apoptotic agents targeting bcl-2 protein. Pharmaceuticals, 2021. 14(2): p. 113.

- Liu, T. , et al., Single and dual target inhibitors based on Bcl-2: Promising anti-tumor agents for cancer therapy. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2020. 201: p. 112446. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.R. , et al., Morpholine substituted quinazoline derivatives as anticancer agents against MCF-7, A549 and SHSY-5Y cancer cell lines and mechanistic studies. RSC Medicinal Chemistry, 2022. 13(5): p. 599-609. [CrossRef]

- Ono, Y. , et al., Design and synthesis of quinoxaline-1, 3, 4-oxadiazole hybrid derivatives as potent inhibitors of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein. Bioorganic Chemistry, 2020. 104: p. 104245. [CrossRef]

- Kulabaş, N. , et al., Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of novel 2-(4H-1, 2, 4-triazole-3-ylthio) acetamide derivatives as inducers of apoptosis in cancer cells. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2016. 121: p. 58-70.

- Daina, A., O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Scientific reports, 2017. 7(1): p. 42717. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , et al., Mechanisms of venetoclax resistance and solutions. Frontiers in Oncology, 2022. 12: p. 1005659. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M. , et al., Venetoclax synergizes with gilteritinib in FLT3 wild-type high-risk acute myeloid leukemia by suppressing MCL-1. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 2022. 140(24): p. 2594-2610. [CrossRef]

- Timucin, A.C., H. Basaga, and O. Kutuk, Selective targeting of antiapoptotic BCL-2 proteins in cancer. Medicinal research reviews, 2019. 39(1): p. 146-175. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y. , et al., Small-molecule Mcl-1 inhibitors: Emerging anti-tumor agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2018. 146: p. 471-482. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. , et al., Design, synthesis and preliminary biological evaluation of indole-3-carboxylic acid-based skeleton of Bcl-2/Mcl-1 dual inhibitors. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 2017. 25(6): p. 1939-1948.

- Xu, G. , et al., 1-Phenyl-1H-indole derivatives as a new class of Bcl-2/Mcl-1 dual inhibitors: Design, synthesis, and preliminary biological evaluation. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry, 2017. 25(20): p. 5548-5556.

- Kamath, P.R. , et al., Some new indole–coumarin hybrids; Synthesis, anticancer and Bcl-2 docking studies. Bioorganic Chemistry, 2015. 63: p. 101-109.

- Nayak, S. , et al., 1, 3, 4-Oxadiazole-containing hybrids as potential anticancer agents: Recent developments, mechanism of action and structure-activity relationships. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society, 2021. 25(8): p. 101284. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., S. -J. Zhao, and Y. Liu, 1, 2, 3-Triazole-containing hybrids as potential anticancer agents: Current developments, action mechanisms and structure-activity relationships. European journal of medicinal chemistry, 2019. 183: p. 111700. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.C. , et al., Thiazole-containing compounds as therapeutic targets for cancer therapy. European journal of medicinal chemistry, 2020. 188: p. 112016. [CrossRef]

- Ashimori, N. , et al., TW-37, a small-molecule inhibitor of Bcl-2, mediates S-phase cell cycle arrest and suppresses head and neck tumor angiogenesis. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 2009. 8(4): p. 893-903. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D. , et al., Obatoclax Induces G1/G0-Phase Arrest via p38/p21waf1/Cip1 Signaling Pathway in Human Esophageal Cancer Cells. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 2014. 115(9): p. 1624-1635.

- Gupta, S., F. Afaq, and H. Mukhtar, Involvement of nuclear factor-kappa B, Bax and Bcl-2 in induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by apigenin in human prostate carcinoma cells. Oncogene, 2002. 21(23): p. 3727-3738. [CrossRef]

- Opydo-Chanek, M. , et al., The pan-Bcl-2 inhibitor obatoclax promotes differentiation and apoptosis of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Investigational New Drugs, 2020. 38: p. 1664-1676. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-c. and P.N. Rao, Effect of gossypol on DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression of mammalian cells in vitro. Cancer research, 1984. 44(1): p. 35-38.

| Compound | R | IC50 * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-231 | MCF-7 | A549 | ||

| U1 | 4-F | 20.66 ± 0.85 | 5.05 ± 0.80 | 13.34 ± 0.58 |

| U2 | 4-OCH3 | 5.22 ± 0.55 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.73 ± 0.07 |

| U3 | 4-CH3 | 4.07 ± 0.35 | 1.17 ± 0.10 | 2.98 ± 0.19 |

| U4 | 3-Cl | 28.38 ± 1.79 | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 16.11 ± 1.4 |

| U5 | 4-Cl | 45.1 ± 1.15 | 34.43 ± 2.20 | 47.77 ± 3.7 |

| U6 | 3,4-Dichloro | 79.4 ± 4.04 | 35.45 ± 2.14 | 66.5 ± 0.62 |

| Gossypol | 5.5 ± 0.35 | 4.43 ± 0.54 | 3.45 ± 0.40 | |

| Compound | IC50 * |

|---|---|

| U2 | 1.2 ± 0.02 |

| U3 | 11.10 ± 0.07 |

| Gossypol | 0.62 ± 0.01 |

| Compound | Moiety | Interaction | Amino acid |

|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | Carbonyl group Phenyl ring Phenyl ring Phenyl ring Phenyl ring Sulfanyl group |

2 H-bond interaction Aromatic H-bond Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction |

Arg-105 Val-92 Tyr-67 Phe-63 Glu-95 Leu- 96 |

| U2 | Carbonyl group Phenyl ring Phenyl ring Phenyl ring Phenyl ring Sulfanyl group Phenyl ring Phenyl ring Phenyl ring |

H-bond interaction Pi-pi staking Aromatic H-bond Pi-pi staking Aromatic H-bond Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction |

Arg-60 Phe-63 Asp-99 Phe-63 Glu-95 Arg-105, Tyr-63 and Ala-108 Ala-108 Tyr-67 Glu-95 |

| U3 | Carbonyl group Phenyl ring CH3 Sulfanyl group Carbonyl group Phenyl ring Phenyl ring Phenyl ring |

2 H-bond interaction Aromatic H-bond Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction Hydrophobic interaction |

Arg-105 Val-92 Glu-95 Leu-96 Arg-105 Asp-70 Tyr-67 and Glu-95 Val-92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).