Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Current Study

2.1. Theoretical framework

2.1.1. Executive functioning and reading comprehension

2.1.2. Intervention studies on executive functioning related to reading comprehension

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.1.2. Design and procedure

3.1.3. Materials

3. Results

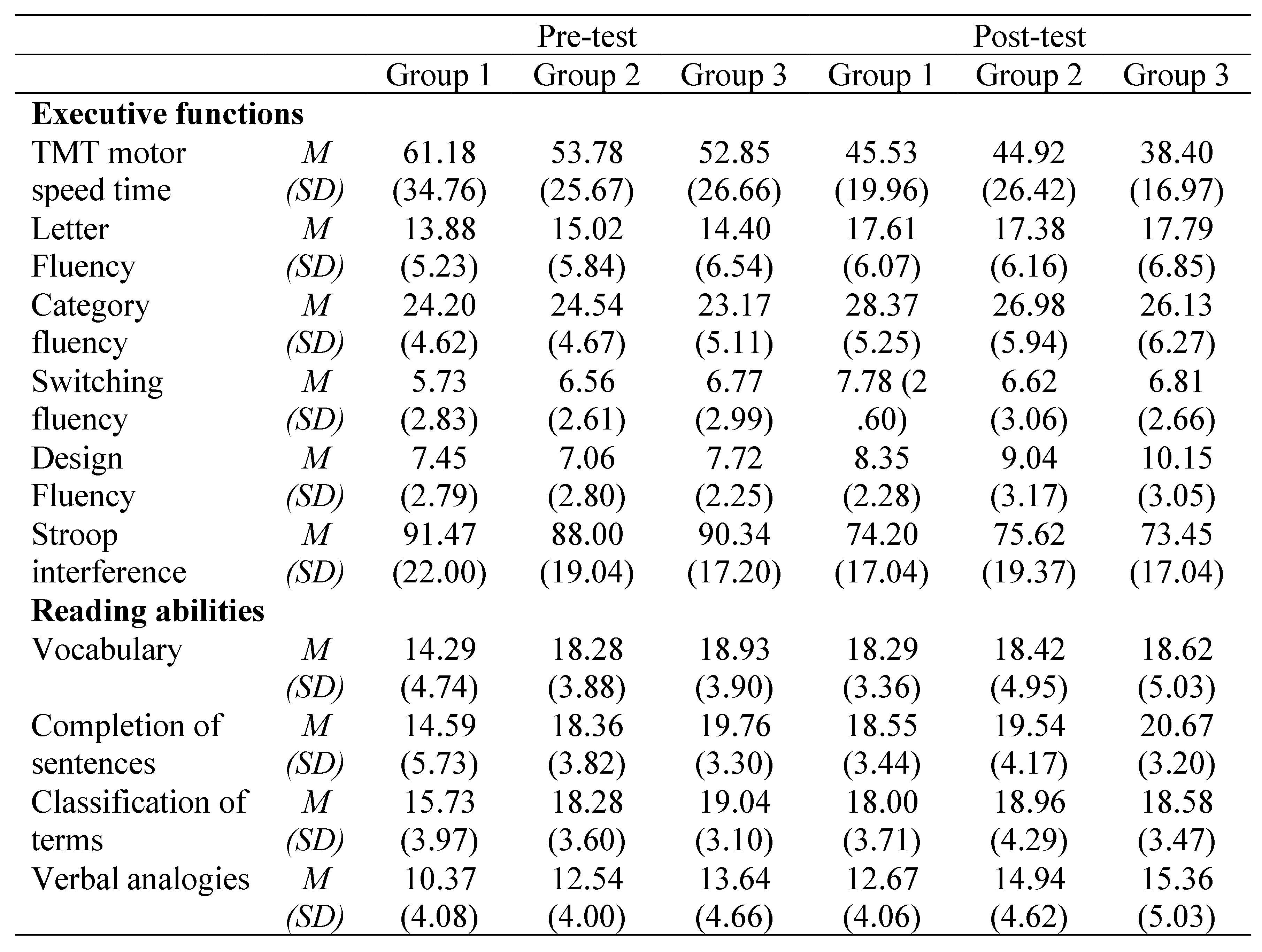

3.1. Effects of training on executive function

3.2. Effects of training on language abilities related to reading comprehension.

3.3. Effects of training on relationship with Slovak language school results.

4. Discussion

4.1. Executive Functioning

4.2. Language abilities related to reading comprehension

4.3. Relations with school performance

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thorndike, R.; Hagen, E. Measurement and Evaluation in Psychology and Education (4th Ed).; Wiley: New York, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, B.; Frias, S. A New Measurement for Assessing the Contributions of Higher Level Component Processes to Language Comprehension in Preschoolers. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 897–921. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins, I.W.; Satlow, E.; Presley, M. Executive Control of Reading Comprehension in Elementary School. In Executive Function in Education. From Theory to Practice.; Meltzer, L., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, 2007; pp. 194–215. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, S.J. Toward a Theory of Automatic Information Processing in Reading. In Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading.; Alvermann, D.E., Unrau, N.J., Ruddell, R.B., Eds.; International Reading Association: Newark, DE, 2013; pp. 698–718. ISBN 978-0-87207-710-2. [Google Scholar]

- Follmer, D.J. Executive Function and Reading Comprehension: A Meta-Analytic Review. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 53, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfuss, R.; Kendeou, P. The Role of Executive Functions in Reading Comprehension. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 30, 801–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.; Cutting, L.E. Relations among Executive Function, Decoding, and Reading Comprehension: An Investigation of Sex Differences. Discourse Process. 2021, 58, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeier, L.E.; Abbott, R.D.; Berninger, V.W. Executive Functions for Reading and Writing in Typical Literacy Development and Dyslexia. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2008, 30, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jablonski, S.; Awramiuk, E.; Grazyna, K.K. Inhibitory Control and Literacy Development among 3- to 5-Year-Old Children. Contribution to a Double Special Issue on Early Literacy Research in Poland. L1-Educ. Stud. Lang. Lit. 2013, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Meixner, J.M.; Warner, G.J.; Lensing, N.; Schiefele, U.; Elsner, B. The Relation between Executive Functions and Reading Comprehension in Primary-School Students: A Cross-Lagged-Panel Analysis. Early Child. Res. Q. 2019, 46, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhs, M.W.; Nesbitt, K.T.; Farran, D.C.; Dong, N. Longitudinal Associations between Executive Functioning and Academic Skills across Content Areas. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 1698–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive Functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.R.; Miller, P.H.; Naglieri, J.A. Relations between Executive Function and Academic Achievement from Ages 5 to 17 in a Large, Representative National Sample. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2011, 21, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, K.; Oakhill, J.; Bryant, P. Children’s Reading Comprehension Ability: Concurrent Prediction by Working Memory, Verbal Ability and Component Skills. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 96, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Daneman, M.; Carpenter, P.A. Individual Differences in Working Memory and Reading. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1980, 19, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, M.A.; Carpenter, P.A. A Theory of Reading: From Eye Fixations to Comprehension. Psychol. Rev. 1980, 87, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, K.B.; Coppage, E.A.; Lane, A.B.; Singleton, T.; Marshall, T.R.; Bentivegna, C. Cognitive Flexibility Deficits in Children with Specific Reading Comprehension Difficulties. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, K.B.; Marshall, T.R.; Huemer, C.M.; Payne, J.B. Executive Function in the Classroom: Cognitive Flexibility Supports Reading Fluency for Typical Readers and Teacher-Identified Low-Achieving Readers. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 88, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, S. Metacognition in Young Children; Routledge, Taylor & Francis group: New York, 2010; ISBN 978-0-415-46358-4. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A. Activities and Programs That Improve Children’s Executive Functions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, L.; Gilmore, C. Skills Underlying Mathematics: The Role of Executive Function in the Development of Mathematics Proficiency. Trends Neurosci. Educ. 2014, 3, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A.; Lee, K. Interventions Shown to Aid Executive Function Development in Children 4 to 12 Years Old. Science 2011, 333, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K.; Tang, Y. Developing Self-Regulation in Early Childhood. Trends Neurosci. Educ. 2013, 2, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M.R.; Checa, P.; Cómbita, L.M. Enhanced Efficiency of the Executive Attention Network after Training in Preschool Children: Immediate Changes and Effects after Two Months. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2012, 2, S192–S204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, T.M.; Barker, L.A.; Naglieri, J.A. Executive Function Treatment and Intervention in Schools. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2014, 3, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, K.B.; Bock, A.M.; Clause, J.H.; August, E.A.; Saunders, H.G.; Schmidt, K.J. Near-and-Far Transfer Effects of an Executive Functions Intervention for 2nd to 5th Grade Struggling Readers. Cogn. Dev. 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Parkinson, J. The Potential for School-Based Interventions That Target Executive Function to Improve Academic Achievement: A Reveiw. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 512–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretti, B.; Caldarola, N.; Tencati, C.; Cornoldi, C. Improving Reading Comprehension in Reading and Listening Settings: The Effect of Two Training Programmes Focusing on Metacognition and Working Memory. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 84, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, A.; Barnett, W.S.; Thomas, J.; Munro, S. Preschool Program Improves Cognitive Control. Science 2007, 318, 1387–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz-Kraus, T. The Role of Executive Functions in the Reading Process. In Reading Fluency; Khateb, A., Bar-Kochva, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2016; pp. 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Matějček, Z. Zkouška Čteni; Psychodiagnostika: Bratislava, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Delis, D.C.; Kaplan, E.; Kramer, J.H. The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ferjenčík, J.; Bobáková, M.; Kovalčíkovvá, I.; Ropovik, I.; Slavkovská, M. Proces a Vybrané Výsledky Slovenskej Adaptácie Delis-Kaplanovej Systému Exekutívnych Funkcií D=KEFS. (Process and Selected Results of Slovak Adaptation of Delis-Kaplan System of Executive Functions D-KEFS). Ceskoslovenská Psychol. Cas. Pszchologickou Teor. Praxi 2014, 58, 543–558. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike, R.; Hagan, E. Test Kognitívnzch Schopností. Príručka. Upravil Vonkomer, J. [Test of Cognitive Abilities. Administration Manual. Adapted by Vonkomer, J.]; Psychodiagnostika: Bratislava, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Partanen, P.; Jansson, B.; Lisspers, J.; Sundin, Ö. Metacognitive Strategy Training Adds to the Effects of Working Memory Training in Children with Special Educational Needs. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalčíková, I.; Veerbeek, J.; Vogelaar, B.; Prídavková, A.; Ferjenčík, J.; Šimčíková, E.; Tomková, B. Domain-Specific Stimulation of Executive Functioning in Low-Performing Students with a Roma Background: Cognitive Potential of Mathematics. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton-McDonald, R.; Erickson, J. Reading Comprehension in the Middle Grades: Characteristics, Challenges, and Effective Supports. In Handbook of research on reading comprehension, 2nd ed; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 2017; pp. 353–376. ISBN 978-1-4625-2888-2. [Google Scholar]

- Klauer, K.J.; Phye, G.D. Inductive Reasoning: A Training Approach. Rev. Educ. Res. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolean, L.; Lervag, A.; Visu-Petra, L.; Melby-Lervag, M. Language Skills, and Not Executive Functions, Predict the Development of Reading Comprehension of Early Readers: Evidence from an Orthographically Transparent Language - Institutt for Spesialpedagogikk. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer, L. Executive Function in Education: From Theory to Practice; Guilford Press: New York, 2007; ISBN 978-1-59385-428-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zanartu, C.R.; Doerr, P.; Portman, J. Teaching 21 Thinking Skills for the 21st Century: The MiCOSA Model; First edition.; Pearson: Boston, 2015; ISBN 978-0-13-269844-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, A.; Guo, Y.; Sun, S.; Lai, M.H.C.; Breit, A.; Li, M. The Contributions of Language Skills and Comprehension Monitoring to Chinese Reading Comprehension: A Longitudinal Investigation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 625555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.; Morgan, K. Intelligent and Effective Learning Based on the Model for Systematic Concept Teaching; SCT Resource. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mathematical and Analogical Reasoning of Young Learners; English, L., Ed.; Routledge: Cambridge, Mass, 2012; ISBN 978-0-262-57139-5. [Google Scholar]

- Richland, L.E.; Simms, N. Analogy, Higher Order Thinking, and Education: Analogy, Higher Order Thinking, and Education. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2015, 6, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | A program focusing on executive functioning stimulation via the Slovak language curriculum with a specific focus on enhancing reading comprehension. |

| 2 | A low performing pupil is understood, in the context of this paper, as a pupil who does not achieve optimal academic performance. According to The Instructional Guidelines no. 22/2011 for the assessment of primary school pupils (Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of Slovak Republic, 2011), pupil’s performance in each school subject (in Slovak Republic) is classified in the following 5-point grading scale: 1 – excellent, 2 – commendable, 3 – good, 4 – sufficient, and 5 – insufficient. A low performing pupil is defined in this chapter as a pupil who attains grades 3 – (good), 4 – (sufficient) or 5 – (insufficient) in the school performance summative assessment at the end of academic year in Slovak Language (mother tongue) and Mathematics. |

| 3 | For the calculation, either the internal consistency estimation via Cronbach’s alpha coefficient or Split-half S-Brown test reliability estimation was used (Delis, Kaplan, & Kramer, 2001); (Ferjenčík, Bobáková, Kovalčíková, Ropovik, & Slavkovská, 2014). |

| Condition | Boy | Girl | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| (active) control 1 | 29 | 22 | 51 |

| (passive) control 2 | 24 | 26 | 50 |

| Total | 78 | 73 | 151 |

| Module/linguistic material | Part Linguistis/cognitive focus |

Recommended number of lessons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word(domain specific) | 1 | Comparison, categorization, grouping | 3 – 4 |

| Word(domain specific) | 2 | Cross classification (similarities and differences) | 2 |

| Self-regulation(domain general) | 2/3 | Attention control and memory | 3 – 4 |

| Word/Sentence(domain specific) | 3 | Attention control and memory | 3 – 4 |

| Sentence(domain specific) | 4 | Deductive-hypothetical thinking | 3 – 4 |

| Sentence(domain specific) | 5 | Paraphrasing | 2 – 3 |

| Sentence(domain specific) | 6 | Co - referential relations between sentences | 2 – 3 |

| Paragraph(domain specific) | 7 | Text analysis and comprehension | 3 – 4 |

| Text(domain specific) | 8 | Self - regulation and pre - reading metacognitive strategies | 1 – 2 |

| Text(domain specific) | 9 | Text decoding and comprehensionReadingmetacognitive strategies | 3 – 4 |

| Text(domain specific) | 10 | Text comprehension 2Readingmetacognitive strategies | 2 – 3 |

| Wilk’s λ | F | p | ηp2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate effects | ||||

| Time | .37 | 38.61 | < .001 | .63 |

| Time x Condition | .85 | 1.91 | .033 | .08 |

| Univariate effects | ||||

| Time | ||||

| TMT motor speed time | 38.00 | <.001 | .21 | |

| Letter fluency | 54.60 | <.001 | .28 | |

| Category fluency | 51.82 | <.001 | .27 | |

| Switching fluency | 7.42 | .007 | .05 | |

| Design fluency | 44.51 | <.001 | .24 | |

| Stroop interference | 121.86 | <.001 | .46 | |

| Time x Condition | ||||

| TMT motor speed time | 1.00 | .369 | .01 | |

| Letter fluency | .95 | .390 | .01 | |

| Category fluency | 1.35 | .263 | .02 | |

| Switching fluency | 6.42 | .002 | .08 | |

| Design fluency | 2.91 | .058 | .04 | |

| Stroop interference | 1.27 | .285 | .02 |

| Wilk’s λ | F | p | ηp2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate effects | ||||

| Time | .68 | 16.11 | < .001 | .32 |

| Time x Condition | .81 | 3.94 | < .001 | .10 |

| Univariate effects | ||||

| Time | ||||

| Vocabulary | 9.79 | .002 | .07 | |

| Completion of sentences | 29.03 | < .001 | .17 | |

| Classification of terms | 5.12 | .025 | .04 | |

| Verbal analogies | 46.32 | < .001 | .25 | |

| Time x Condition | ||||

| Vocabulary | 11.32 | < .001 | .14 | |

| Completion of sentences | 6.82 | .001 | .09 | |

| Classification of terms | 4.64 | .011 | .06 | |

| Verbal analogies | .46 | .634 | .01 |

| Pretest x School result | Posttest x School result | |||

| Total | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

| Executive functions | ||||

| TMT motor speed time | -.19* | -.20 | -.39* | -.02 |

| Letter fluency | .11 | .04 | .16 | .01 |

| Category fluency | .16 | -.07 | .33* | .22 |

| Switching fluency | .28* | .09 | .35* | .11 |

| Design fluency | .04 | .01 | .31* | -.03 |

| Stroop interference | -.19* | -.24 | -.17 | -.15 |

| Reading abilities | ||||

| Vocabulary | .43* | .35* | .33* | .35* |

| Completion of sentences | .54* | .33* | .37* | .50* |

| Classification of terms | .49* | .17 | .20 | .47* |

| Verbal analogies | .50* | .30* | -.28 | .39* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).