Submitted:

13 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Origin and distribution

3. Varieties and varietal selection

4. Production of pearl millet

4.1. Production constraints and interventions

4.1.1. Abiotic constraints

4.1.2. Biotic constraints

4.2. Interventions adopted by farmers, the government and way forward

4.3. Way forward for pearl millet production

5. Potential Research Areas

- To develop improved varieties of pearl millet through germplasm evaluation and breeding

- To develop early maturing pearl millet varieties that are resistant to drought, downy mildew diseases

- To determine what factors make pearl millet immune to striga infestation in Eritrea

- To improve and develop the production environment through adoption of integrated drought management initiatives to ensure better production environment.

- To promote pearl millet production through integrated agronomic management technologies among the farmers

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

References

- Sati, V.P. Farming systems and strategies for sustainable livelihood in Eritrea. African Journal of Food Agriculture Nutrition and Development 2008, 8, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, S.; Naqvi, Y. Prevalence of economically important fungal diseases at different phenological stages of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) in Sub-zone Hamelmalo. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development 2013, 2, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Country report to the FAO international technical conference on plant genetic resources. Ministry of Agriculture, Eritrea. 1996.

- Gari, A.J. Review of the African millet diversity Paper for the International workshop on fonio, food security and livelihood among the rural poor in West Africa. 2002 Papier pour l’Atelier international sur le fonio, la sécurité alimentaire et le bien-être pour les paysans pauvres d’Afrique de l’Ouest. IPGRI / , Bamako, Mali, 19–22 November 2001. 19–22 November.

- Mason, C.S.; Maman, N.; Pale, S. Pearl millet production practices in semi-arid West Africa: a review. Explanation Agriculture. 2015, 51, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environmental Program. Sahel Atlas of Changing Landscapes: Tracing trends and variations in vegetation cover and soil condition. United Nations Environment Programme. Nairobi. 2012.

- Abraha, N.; Roden, P. Farmer experience with productivity enhancing technology uptake: A case study of pearl millet in Eritrea. In Integrated sorghum and millet sector for increased economic growth and improved livelihoods in Eastern and Central Africa Proceedings of the ECARSAM Stakeholders Conference 20–22 November 2006, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 2012.

- Ministry of Agriculture. Country report to the FAO international technical conference on plant genetic resources. Ministry of Agriculture, Eritrea. 2021.

- Dayakar-Rao, B.; Bhaskarachary, K.; Arlene Christina, G.D.; Sudha Devi, G.; Tonapi, V.A. Nutritional and health benefits of millets. ICAR-Indian Institute of Millets Research, Hyderabad, India, New Delhi, India. 2017; 104pp.

- Nithiyanantham, S. , Kalaiselvi P., Mahomoodally M.F., Zengin G., Abirami A., Srinivasan G.. Nutritional and functional roles of millets—A review. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2019, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfany, G.; Diack, O.; Kane, N.A.; Gangashetty, P.I.; Sy, O.; Fofana, A.; Cisse, N. Implications of farmer perceived constraints and varietal preferences to pearl millet breeding in Senegal. African Crop Science Journal 2020, 28, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. The world sorghum and millet economies: Facts, trends and outlook. A joint study by the Basic Foodstuffs Service FAO Commodities and Trade Division and the Socioeconomics and Policy Division. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. 1996. Rome Italy.

- Yadav, H.P.; Gupta, S.K.; Rajpurohit, B.S.; Pareek, N. Pearl millet. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roden, P.; Negusse, A.; Merhawit, D.; Menghistab, G.; Haile, B.; Thomas, K. Farmers’s appraisal of pearl millet varieties in Eritrea. Bern, Geographica Bernensia. 2007; 47 pp. SLM Eritrea; National Agricultural Research Institute (NARI), and Ministry of Agriculture, Eritrea; Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA), and Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern.

- Abdella, O.; Shemendi, G.; Naqvi, S.Y.; Jamo, L.M. Yield and Yield constraints Assessment of Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) in Sub Zoba-Hamelmalo, Eritrea, East Africa Bulletin of Environment. Pharmacology and Life Sciences 2021, 10, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, O.P.; Rai, K.N.; Gupta, S.K. Pearl millet: genetic improvement for tolerance to abiotic stresses. In: Improving Crop Resistance to Abiotic Stress. Edited by N. Tuteja, S. S. GilL and R. Tuteja. Wlley·VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. 2012; pp. 261-288.

- Gupta, S.M.; Arora, S.; Mirza, N.; Pande, A.; Lata, C.; Puranik, S. Finger millet: a “certain” crop for an “uncertain” future and a solution to food insecurity and hidden hunger under stressful environments. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, F.T.; Griffiths, R.I.; Knight, C.G.; Nicolitch, O. Williams, A. Harnessing rhizosphere microbiomes for drought-resilient crop production. Science 2020, 368, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabo, I.; Zangre, R.G.; Dangquah, Y.E.; Ofori, K.; Witcombe, J.R.; Hash, T. Identifying farmer’s preferences and constraints to pearl millet production in the Sahel and North Sudan Zones of Burkina Faso. Experimental Agriculture 2019, 55, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. FAOSTAT data base. 2014. Available at: http://faostat.fao.org/site/5676/DesktopDefault.aspx.

- NAAS Promoting millet production, value addition and consumption. Policy Paper No. 114, National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, New Delhi. 2022; 24 p.

- Ministry of Land, Water and Environment. The 4th national report to the convention on biological diversity. The State of Eritrea Ministry of Land, Water and Environment Department of Environment. 2010.

- Natarajan, M. Strengthening the agricultural research and extension in Eritrea, GCP/ERI/001/ITA. Report of the consultation on Production/Farming Systems Agronomy. State of Eritrea Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Agricultural Research and Human Resources Development and FAO. 1999; PP 48. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ogba-Michael, B. Agronomy in spate irrigated areas of Eritrea. Ministry of Agriculture. The State of Eritrea. 2003.

- Hatzig, S.; Nuppenau, J.N.; Snowdom, R.J.; Schiel, S.V. Drought stresshas transgenerational effect on seeds and seedlings in winter oilseed rape (Brassicae napus L). BMC Plant Biology 2018, 8, 297. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Tarafder, J.C.; Painuli, D.K.; Raina, P.; Singh, M.P.; Beniwal, R.K.; Soni, M.L.; Kumar, M.; Santra, P.; Shamsudin, M. Variability in arid soils characteristics. In: Kar A, Garg BK, Singh MP, Kathju S (eds) Trends in arid zone research in India. Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur. 2009; pp 78–112.

- Bationo, A.; Kihara, J.; Waswa, B.; Ouattara, B.; Vanlauwe, B. Technologies for sustainable management of sandy Sahelian soils. In: Management of Tropical Sandy soils for sustainable agricultura. A holistic approach for sustainable development of problematic soils in the tropics. FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok. 2014; 414-429.

- Bhasker, R.; Bidinger, A.G.; Panduranga, F.; Rao, V.; Negusse, A. Report of a survey of downy mildew incidence in farmers’ fields in Anseba and Gash Barka Regions and an evaluation of the pearl millet breeding trials and nurseries at the Hagaz Research Station. ICRISAT, Patancheru, India, and ARHRD, Ministry of Agriculture, Eritrea. 2000; 121-128. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Roumba A, Shimelis H, Drabo I, Laing M, Gangashetty P, Mathew Isack, Mrema E, Shayanowako A. Constraints to Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) Production and Farmers’ Approaches to Striga hermonthica Management in Burkina Faso. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Kanampiu, F.K.; Karaya, H.; Charnikhova, T.; Bouwmeester, H.J. Striga hermonthica parasitism in maize in response to N and P fertilizers. Field Crops Research 2012, 134, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, K.; Awad, A.A.; Xie, X.; Takeuchi, Y. Strigolactones as germination stimulants for root parasitic plants. Plant Cell Physiolgy 2010, 51, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawud, M.A.; Angarawai, I.I.; Tongoona, P.B.; Ofori, K.; Eleblu, J.S.; Ifie, B. Farmers’ production constraints, knowledge of striga and preferred traits of pearl millet in Jigawa State, Nigeria. Global Journal of Science Frontier Research 2017, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo, N.; Sanou, J.; Kam, H.; Traore, H.; Adam, M.; Gracen, V.; Danquah, E.Y. Farmers’ perception on impact of drought and their preference for sorghum cultivars in Burkina Faso. Agricultural Science Research Journal 2017, 7, 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Rouw, A. Long-term topsoil changes under pearl millet production in the Sahel. in management of tropical sandy soils for sustainable agriculture. A holistic approach for sustainable development of problems soils in the tropics. Proceedings held on the 27th November - 2nd December 2005 in Khon Kaen, Thailand. 20 December.

- Reddy, K.C.; van der Ploeg, J.; Maga, I. Genotype effects in millet/cowpea intercropping in the semi-arid tropics of Niger. Experimental Agriculture 1990, 26, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.; Koala, S.; Bationo, A. Long term soil fertility trials in Niger, West Africa. In lessons learned from long term soil fertility management experiments in Africa, 105-120(EdsB. Bationo, B. Waswa, J Kihara, I, Adolwa, B. Vanlauwe and KSaidou). 2012; Dordrecht: Springer. S.

- Roupsard, O.; Ferhi, A.; Granier, A.; Pallo, F.; Depommier, D.; Mallet, B.; Joly, H.I.; Dreyer, D. Reverse phenology and dry-season water uptake by Faidherbia albida (Del.) A. Chev. in an agroforestry parkland of Sudanese West Africa. Functional Ecology 1999, 13, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doso, S.J. Land degradation and agriculture in the Sahel of Africa: causes, impacts and recommendations. Journal of Agricultural Science and Applications 2014, 3, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mokgolodi, N.C.; Setshogo, M.P.; Ling-ling, S.; Yu-jun, L.; Chao, M.A. Achieving food and nutritional security through agroforestry: a case of Faidherbia albida in Sub-Saharan Africa. Forestry Studies China 2011, 13, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfany, G.; Diack, O.; Kane, N.A.; Gangashetty, P.I.; Sy, O.; Fofana, A.; Cisse, N. Implications of farmer perceived constraints and varietal preferences to pearl millet breeding in Senegal. African Crop Science Journal 2020, 28, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulatu, E.; Belete, K. Participatory varietal selection in lowlands sorghum in Eastern Ethiopia: Impact on adoption and genetic diversity. Experimental Agriculture 2001, 37, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omanya, G.O.; Weltzien-Rattunde, E.; Sogodogo, D.; Sanogo, M.; Hansens, N.; Guero, Y.; Zangre, R. Participatory varietal selection with improved pearl millet in West Africa. Experimental Agriculture 2007, 43, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaka, A. Development of downy mildew resistant F1 pearl millet hybrids in Niger. PhD Thesis, University of Ghana, Ghana, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka, Y.; Awala, S.K.; Hove, K.; Nanhapo, P.I.; Iijima, M. Effects of Cultivation Management on Pearl Millet Yield and Growth Differed with Rainfall Conditions in a Seasonal Wetland of Sub-Saharan Africa. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Development Group. Eritrea interim country strategy paper (I-CSP) 2017-2019. African Development Bank. 2017.

- IFAD State of Eritrea: Country Strategic Opportunities Programme 2020-2025. 2020.

- Tesso, T.; Ejeta, G. Integrating multiple control options enhances Striga management and sorghum yield on heavily infested soils. Agronomy Journal 2011, 103, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrema, E.; Shimelis, H.; Laing, M.; Bucheyeki, T. Farmers’ perception of sorghum production constraints and striga control practices in semi-arid area of Tanzania. International Journal of Pest Management 2016, 63, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

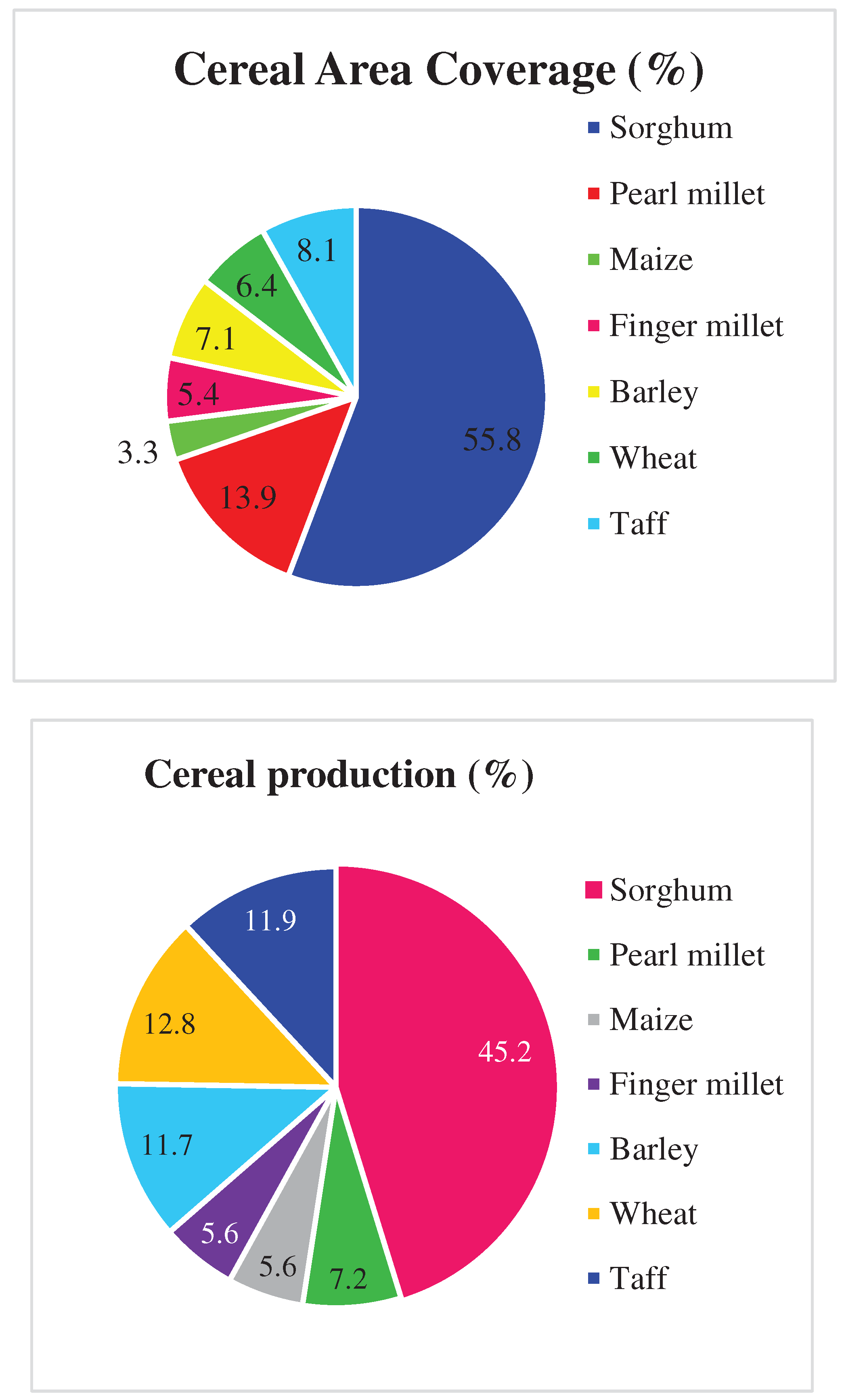

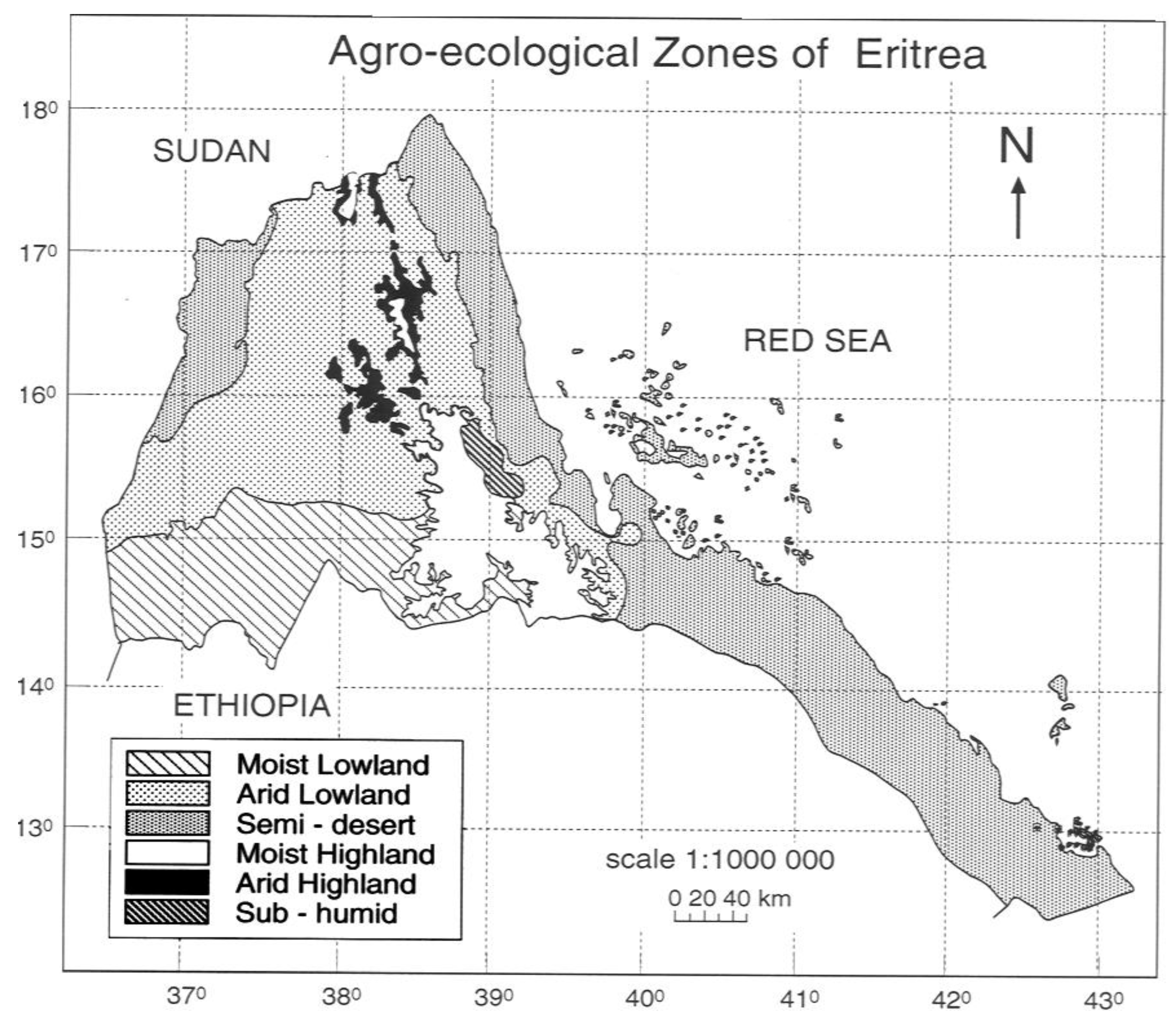

| Agro-ecological Zone (AEZ) | Dominant crop | Altitude (m.asl) | Rainfall (mm) | Temperature (oC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arid highland | Sorghum, pearl millet, barley | 1600-2600 | 200-500 | 15-21 |

| Moist lowland | Sorghum, pearl millet, sesame, cotton, Finger millet, maize | 500-1600 | 500-800 | 21-28 |

| Arid lowland | Sorghum, pearl millet | 400-1600 | 200-500 | 21-29 |

| Variety/Landrace | Preferred characteristics | Drawbacks | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dukun (Landrace) | Very high tillering capacity. Shoots produce new branches when panicles are removed. Tall statured and resistant to stink and ear head bug, | Susceptible to downy mildew, low yields | [14,15,23] |

| Kona (ICMV221)(Improved variety) | High yielding (2.0 – 2.8t/ha) compared to the local varieties, early maturity (70-75 days), short to medium in height, drought tolerant, Resistant to downy mildew, long durability. | Susceptible to bird damage | [14,15,23] |

|

Hagaz (Improved variety) |

High yielding (2.2 – 3.0 t/ha, intermediate maturity (75-85 days), medium plant height (200 -230 cm), drought tolerant, Fairly resistant to downy mildew | Susceptible to bird damage | [14] |

| Tokroray (Landrace) | Very high tillering capacity shoots produce new branches when panicles are removed. | Late maturing, Susceptible to downy mildew, low yields | [14,15] |

| Zibedi (Landrace) | Very high tillering capacity | late maturity, high water demand, Susceptible to downy mildew, low yielding | [14,15,23] |

| Baryay (Landrace) | Adapted to the local environmental conditions, has good taste with good marketability, | Susceptible to downy mildew | [15] |

| Bultug (Landrace) | Long durability | Susceptible to downy mildew, late maturity (90-110 days), | [14,15,23] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).