Submitted:

27 July 2023

Posted:

27 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Raw material

2.2. Physicochemical characterization of cascalote pods

2.3. Microorganisms

2.4. Solid-state fermentation (SSF)

2.5. Evaluation of the SSF factors for the total polyphenol extraction

2.6. Analytical analysis

2.6.1. Determination of polyphenol content

2.6.2. Antioxidant activity

2.6.3. Identification of phenolic compounds

2.7. Experimental design

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical characterization of cascalote pods

3.2. Kinetics of TPC extraction and AA using Aspergillus strains

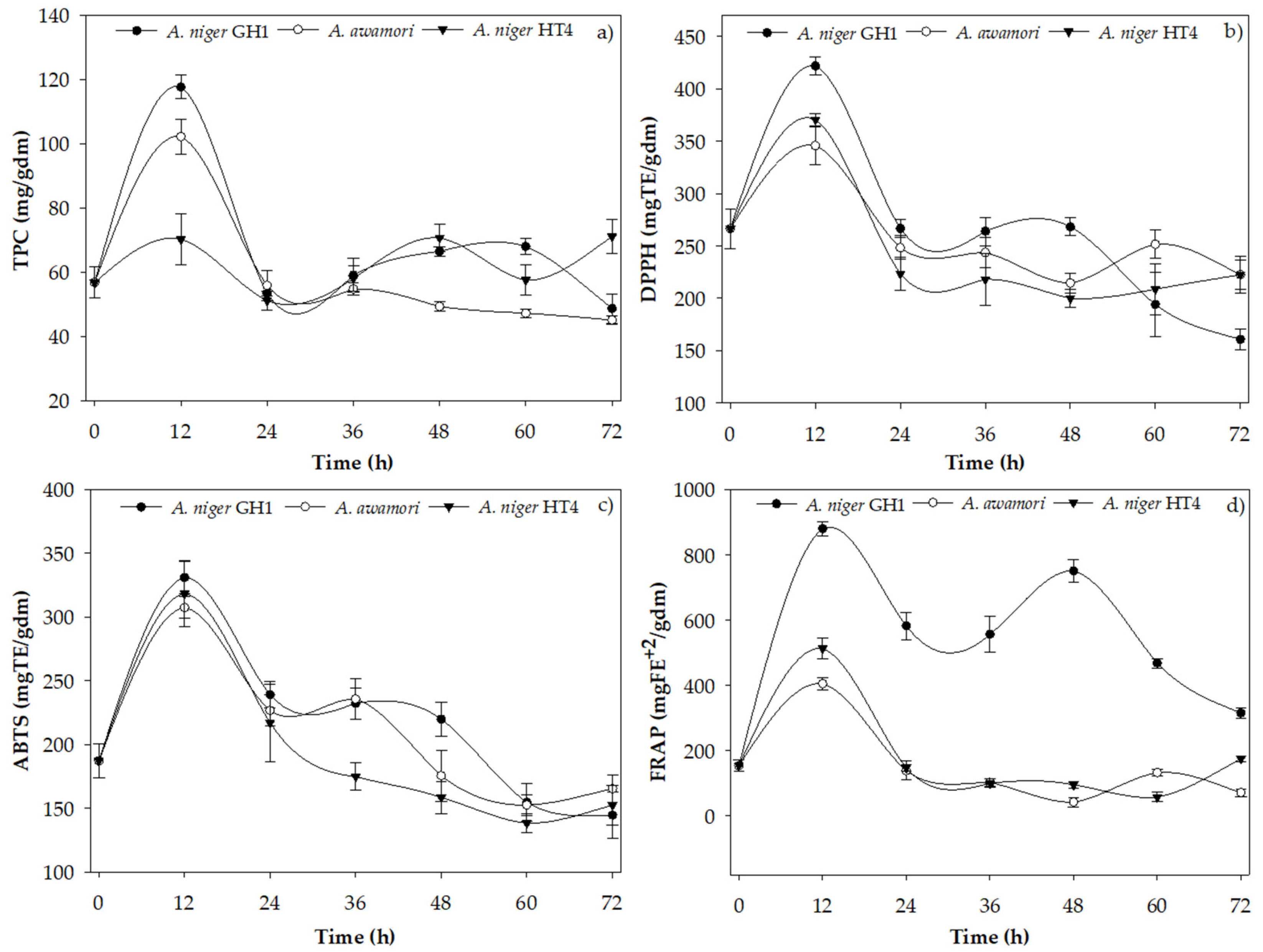

3.3. Significant factors for TPC release by SSF

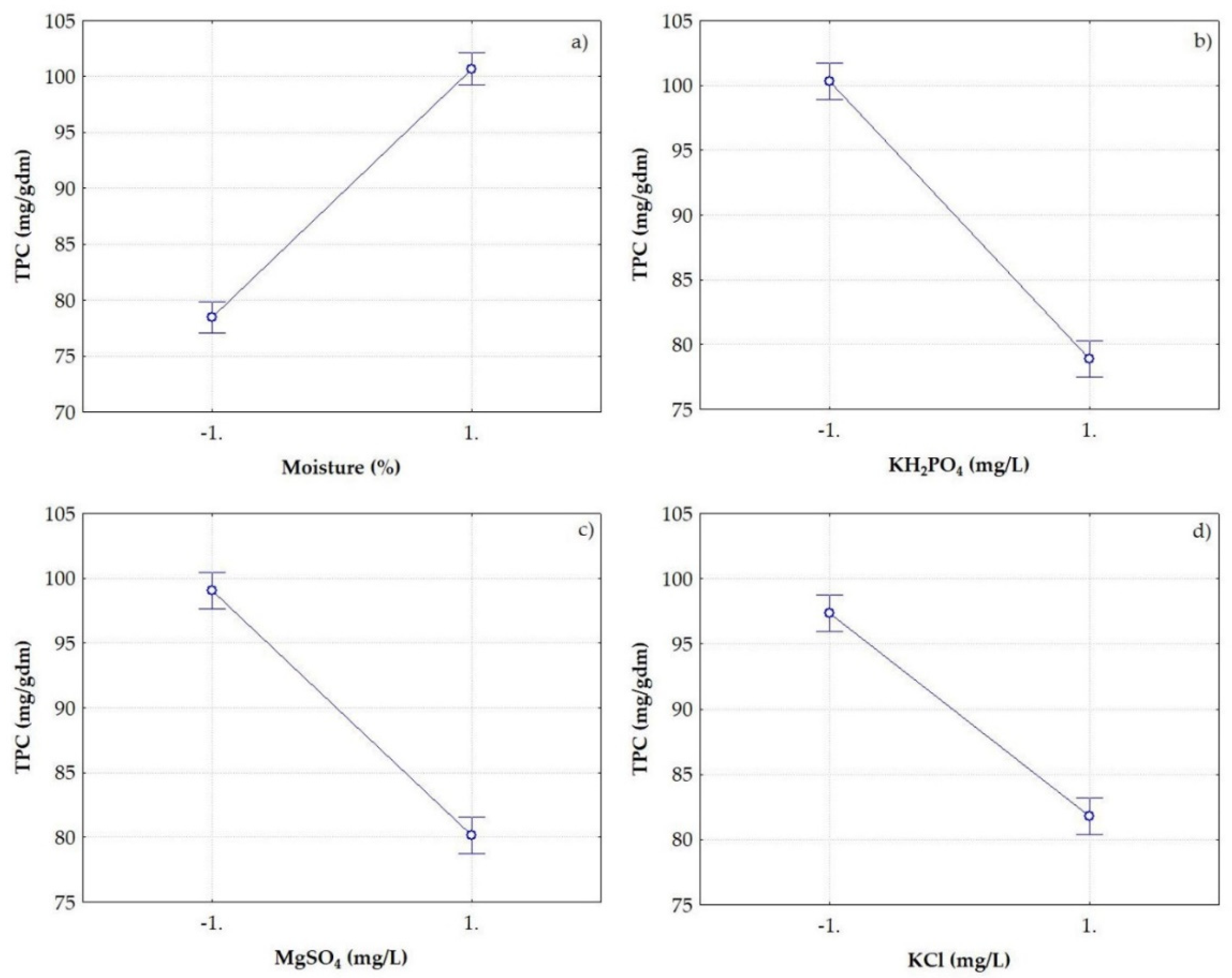

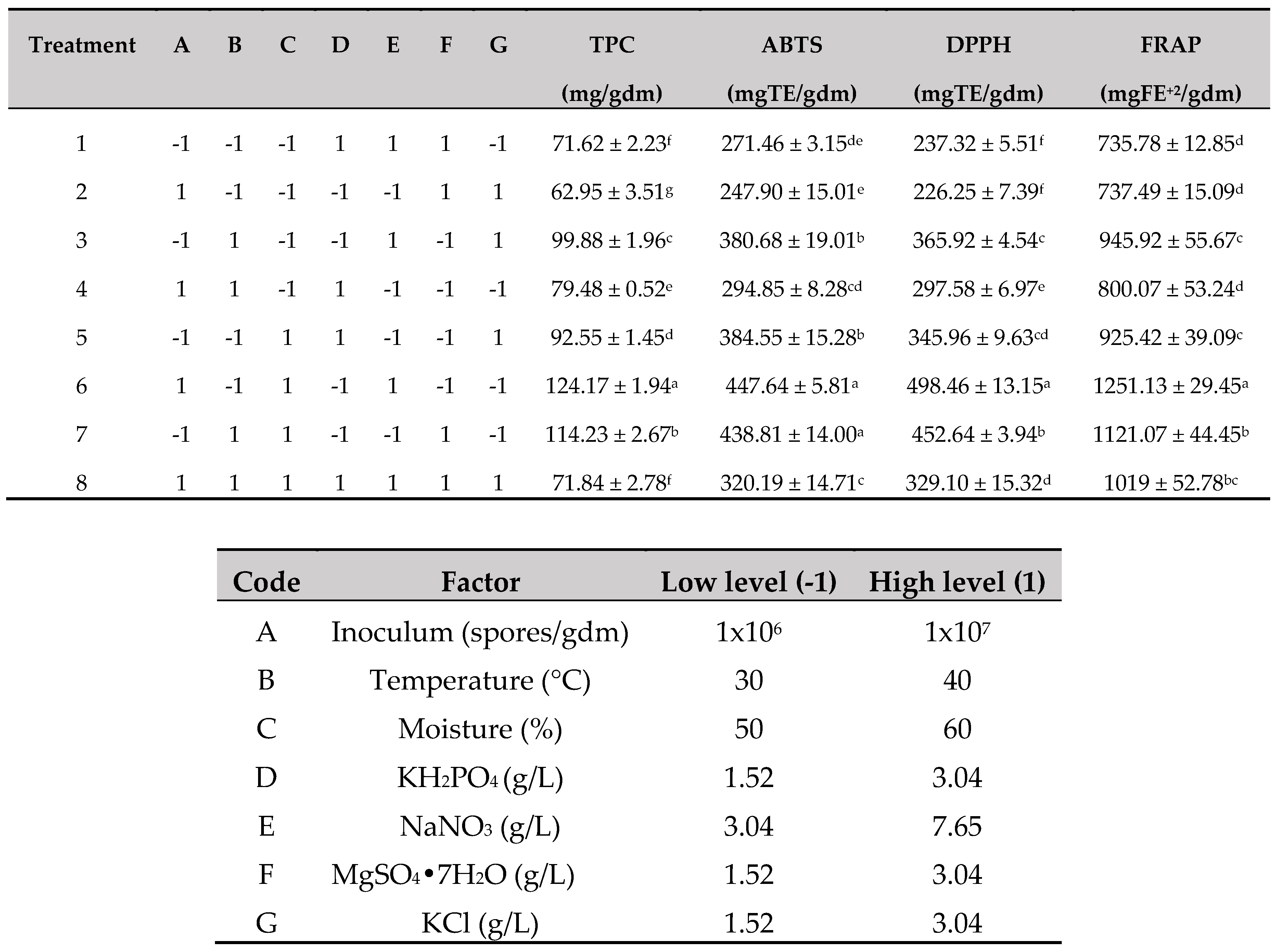

3.4. Effect of SSF on chemical composition, tannin content, and antioxidant activity

3.5. Identification of phenolic compounds by RP-HPLC-ESI-MS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Palma García, J.M. Caesalpinia coriaria (Jacq.) Wild. In Recursos arboreos y arbustivos tropicales, Palma García, J.M., González-Reveles, C., Eds.; Universidad de Colima: México, 2018; pp. 30–34, http://ww.ucol.mx/content/publicacionesenlinea/adjuntos/Recursos-arboreos-y-arbustivostropicales_462.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Carranza, J.N.; Alvarez, L.; Marquina-Bahena, S.; Salas-Vidal, E.; Cuevas, V.; Jiménez, E.W.; Veloz G, R.A.; Carraz, M.; González-Maya, L. Phenolic Compounds Isolated from Caesalpinia coriaria Induce S and G2/M Phase Cell Cycle Arrest Differentially and Trigger Cell Death by Interfering with Microtubule Dynamics in Cancer Cell Lines. Molecules 2017, 22, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeva, K.; Thiyagarajan, M.; Elangovan, V.; Geetha, N.; Venkatachalam, P. Caesalpinia coriaria leaf extracts mediated biosynthesis of metallic silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity against clinically isolated pathogens. Industrial Crops and Products 2014, 52, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo-Juárez, A.; Briones-Robles, T.I.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A.; Zamilpa, A.; Ojeda-Ramírez, D.; Mendoza de Gives, P.; Olivares-Pérez, J.; Rivero-Perez, N. Antibacterial activity of compounds isolated from Caesalpinia coriaria (Jacq) Willd against important bacteria in public health. Microbial Pathogenesis 2019, 136, 103660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, W.; Chen, L.; Tong, Q.; Ming, Y. Corilagin, a promising medicinal herbal agent. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 99, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, D.P.; Boskou, G.; Andrikopoulos, N.K. Recovery of antioxidant phenolics from white vinification solid by-products employing water/ethanol mixtures. Bioresource Technology 2007, 98, 2963–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of phenolic compounds: A review. Current Research in Food Science 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano y Postigo, L.O.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; Guajardo-Flores, D.; Garcia Amezquita, L.E.; García-Cayuela, T. Solid-state fermentation for enhancing the nutraceutical content of agrifood by-products: Recent advances and its industrial feasibility. Food Bioscience 2021, 41, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.T.; Van Camp, J.; Smagghe, G.; Raes, K. Improved Release and Metabolism of Flavonoids by Steered Fermentation Processes: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 15, 19369–19388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Mussatto, S.I.; Martínez-Avila, G.; Montañez-Saenz, J.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J.A. Bioactive phenolic compounds: Production and extraction by solid-state fermentation. A review. Biotechnology Advances 2011, 29, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; Ramírez-Guzmán, N.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.; Serna-Cock, L.; dos Santos Correia, M.T.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. Solid-state fermentation with Aspergillus niger to enhance the phenolic contents and antioxidative activity of Mexican mango seed: A promising source of natural antioxidants. LWT 2019, 112, 108236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda-Cejudo, N.D.; Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J.; Sepúlveda, L.; Torres-Leon, C.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N. Recovery of ellagic acid from mexican rambutan peel by solid-state fermentation-assisted extraction. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2022, 134, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Liao, W.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J.; Chang, X.; Peng, G.; Huang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, N.; Yu, Q. Release characteristic and mechanism of bound polyphenols from insoluble dietary fiber of navel orange peel via mixed solid-state fermentation with Trichoderma reesei and Aspergillus niger. LWT 2022, 161, 113387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Sepúlveda, L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Pedroza-Islas, R.; Huerta-Ochoa, S.; Arely Prado-Barragán, L. Improved Extraction of High Value-Added Polyphenols from Pomegranate Peel by Solid-State Fermentation. Fermentation 2023, 9, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Arteaga, S.L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Cadena-Chamorro, E.; Serna-Cock, L.; Aguilar-González, M.A.; Ramírez-Guzmán, N.; Torres-León, C. Bioprocessing of pineapple waste for sustainable production of bioactive compounds using solid-state fermentation. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2023, 85, 103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC, I.; Latimer, G.W. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC, 19th ed ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, Md, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Orzua, M.C.; Mussatto, S.I.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Rodriguez, R.; de la Garza, H.; Teixeira, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N. Exploitation of agro industrial wastes as immobilization carrier for solid-state fermentation. Industrial Crops and Products 2009, 30, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Paz, J.E.; Muñiz-Márquez, D.B.; Aguilar-Zárate, P.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Aguilar, C.N. Microplate Quantification of Total Phenolic Content from Plant Extracts Obtained by Conventional and Ultrasound Methods. Phytochemical Analysis 2014, 25, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, N.P.; Nevárez-Moorillón, V.; Rodriguez-Herrera, R.; Espinoza, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. A microassay for quantification of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydracyl (DPPH) free radical scavening. African Journal of Biochemical Research 2014, 8, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Gutiérrez, E.; Carrasco-Molinar, O.; Tirado-Gallegos, J.M.; Levario-Gómez, A.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Baeza-Jiménez, R.; Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J. Evaluation of green extraction processes, lipid composition and antioxidant activity of pomegranate seed oil. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2021, 15, 2098–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, R.; Bravo, L.; Saura-Calixto, F. Antioxidant activity of dietary polyphenols as determined by a modified ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2000, 48, 3396–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Santacruz, A.; Roman-Miranda, M.L.; González-Cueva, G.; Barrientos-Ramírez, L. Chemical composition of cascalote Caesalpinia coriaria (Jacq.) Willd. and diversity of uses in the rural areas of dry tropics. Revista de Investigación y Desarrollo 2018, 4, 24–28, https://www.ecorfan.org/spain/researchjournals/Investigacion_y_Desarrollo/vol4num12/Revista_de_Investigacion_y_Desarrollo_V4_N12_4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Z.E.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. Development of fibre-enriched wheat breads: impact of recovered agroindustrial by-products on physicochemical properties of dough and bread characteristics. European Food Research and Technology 2017, 243, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ávila, G.C.; Aguilera-Carbó, A.F.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Aguilar, C.N. Fungal enhancement of the antioxidant properties of grape waste. Annals of Microbiology 2012, 62, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.; Ascacio-Valdés, A.; Sepúlveda, L.; De La Cruz, R.; Prado-Barragán, A.; Aguilar-González, M.A.; Rodríguez, R.; Aguilar, C.N. Potential use of different agroindustrial by-products as supports for fungal ellagitannase production under solid-state fermentation. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2014, 92, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J.; Velázquez, M.; Flores-Ortega, O.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Huerta-Ochoa, S.; Aguilar, C.N.; Prado-Barragán, L.A. Solid state fermentation of fig (Ficus carica L.) by-products using fungi to obtain phenolic compounds with antioxidant activity and qualitative evaluation of phenolics obtained. Process Biochemistry 2017, 62, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, M.K.; Krishna, C.; Moo-Young, M. Fungal solid state fermentation — an overview. In Applied Mycology and Biotechnology, Khachatourians, G.G., Arora, D.K., Eds.; Elsevier: 2001; Volume 1, pp. 305-352. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1874533401800149.

- Jericó Santos, T.R.; Santos Vasconcelos, A.G.; Lins de Aquino Santana, L.C.; Gualberto, N.C.; Buarque Feitosa, P.R.; Pires de Siqueira, A.C. Solid-state fermentation as a tool to enhance the polyphenolic compound contents of acidic Tamarindus indica by-products. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2020, 30, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Maia, I.; Thomaz dos Santos D'Almeida, C.; Guimarães Freire, D.M.; d'Avila Costa Cavalcanti, E.; Cameron, L.C.; Furtado Dias, J.; Simões Larraz Ferreira, M. Effect of solid-state fermentation over the release of phenolic compounds from brewer's spent grain revealed by UPLC-MSE. LWT 2020, 133, 110136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, C. Solid-State Fermentation Systems—An Overview. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2005, 25, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, L.; Aguilera-Carbó, A.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Martínez-Hernández, J.L.; Aguilar, C.N. Optimization of ellagic acid accumulation by Aspergillus niger GH1 in solid state culture using pomegranate shell powder as a support. Process Biochemistry 2012, 47, 2199–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisansaneeyakul, S.; Jitbanjongkit, S.; Prasomsart, N.; Luangpituksa, P. Production of β-Fructofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger ATCC 20611. Agricultural and Natural Resources 2000, 34, 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rubio, R.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Rivera, J.; Trevijano-Contador, N. The Fungal Cell Wall: Candida, Cryptococcus, and Aspergillus Species. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espitia-Hernández, P.; Ruelas-Chacón, X.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Flores-Naveda, A.; Sepúlveda-Torre, L. Solid-State Fermentation of Sorghum by Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus niger: Effects on Tannin Content, Phenolic Profile, and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2022, 11, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, N.; Mendoza, G.D.; Martínez, J.A.; Hernández, P.A.; Camacho Diaz, L.M.; Lee-Rangel, H.A.; Vazquez, A.; Flores Ramirez, R. Effect of Caesalpinia coriaria Fruits and Soybean Oil on Finishing Lamb Performance and Meat Characteristics. BioMed Research International 2018, I, 9486258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Morales, D.; Cubides-Cárdenas, J.; Montenegro, A.C.; Martínez, C.A.; Ortíz-Cuadros, R.; Rios-de Álvarez, L. Anthelmintic effect of four extracts obtained from Caesalpinia coriaria foliage against the eggs and larvae of Haemonchus contortus. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2021, 30, e002521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Peña, E.A.; Capistran-Amezcua, D.; Reyes-Ramírez, A.; Xolalpa-Molina, S.; Chávez-Piña, A.E.; Figueroa, M.; Navarrete, A. Gastroprotective effect methanol extract of Caesalpinia coriaria pods against indomethacin- and ethanol-induced gastric lesions in Wistar rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2023, 305, 116057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pájaro González, Y.; Méndez Cuadro, D.; Fernández Daza, E.; Franco Ospina, L.A.; Redondo Bermúdez, C.; Díaz Castillo, F. Inhibitory activity of the protein carbonylation and hepatoprotective effect of the ethanol-soluble extract of Caesalpinia coriaria Jacq. Oriental Pharmacy and Experimental Medicine 2016, 16, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, C.; Rojo-Rubio, R.; Olmedo-Juárez, A.; Zamilpa, A.; Mendoza de Gives, P.; Antonio-Romo, I.A.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L.; Arece-García, J.; Tapia-Maruri, D.; González-Cortazar, M. Galloyl derivatives from Caesalpinia coriaria exhibit in vitro ovicidal activity against cattle gastrointestinal parasitic nematodes. Experimental Parasitology 2019, 200, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-López, L.; Rivero-Perez, N.; Valladares-Carranza, B.; Olmedo-Juárez, A.; Delgadillo-Ruiz, L.; Vega-Sánchez, V.; Hori-Oshima, S.; Nassan, M.A.; Batiha, G.E.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A. Antibacterial Potential of Caesalpinia coriaria (Jacq) Willd Fruit against Aeromonas spp. of Aquaculture Importance. Animals 2022, 12, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, C.; Rojo-Rubio, R.; Gives, P.M.-d.; González-Cortazar, M.; Zamilpa, A.; Mondragón-Ancelmo, J.; Villa-Mancera, A.; Olivares-Pérez, J.; Tapia-Maruri, D.; Olmedo-Juárez, A. In vitro and in vivo anthelmintic properties of Caesalpinia coriaria fruits against Haemonchus contortus. Experimental Parasitology 2022, 242, 108401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulansari, A.; Elya, B.; Noviani, A. Arginase Inhibitory and Antioxidant Activities of Caesalpinia coriaria (Jacq.) Willd. Bark Extract. Pharmacognosy Journal 2018, 10, 1174–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitre-Ruiz, L.; Galván-Ayala, D.; Castro-Uriana, O.; Ávila Mendez, K.J.; Lopez-Pazos, S.A. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Caesalpinia coriaria (Jacq.) Willd extracts on Streptococcus pyogenes and Candida albicans. Vitae 2021, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Content |

|---|---|

| Moisture (g/100 gdb) | 3.36 ± 0.15 |

| Fat (g/100 gdb) | 0.65 ± 0.09 |

| Fiber (g/100 gdb) | 6.54 ± 0.25 |

| Protein (g/100 gdb) | 3.44 ± 0.13 |

| Ash (g/100 gdb) | 2.13 ± 0.21 |

| Carbohydrates (g/100 gdb) | 87.24 ± 0.96 |

| Water absorption capacity (g of gel/gdw) | 2.97 ± 0.07 |

| Critical humidity point (%) | 3.75 ± 0.29 |

| Maximum moisture of cascalote pods (%) | 79.33 ± 2.08 |

| Variables | HP | CP | TPC | ABTS | DPPH | FRAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP | 1 | 0.94* | 0.98* | 0.94* | 0.94* | 0.82* |

| CP | 1 | 0.98* | 0.93* | 0.94* | 0.84* | |

| TPC | 1 | 0.95* | 0.95* | 0.85* | ||

| ABTS | 1 | 0.95* | 0.87* | |||

| DPPH | 1 | 0.95* | ||||

| FRAP | 1 |

| Parameter/Treatment | Control (0 h) | Treatment 6 (12 h)* |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture (g/100 gdb) | 4.90 ± 0.04b | 5.40 ± 0.20a |

| Fat (g/100 gdb) | 0.23 ± 0.05b | 0.34 ± 0.10a |

| Fiber (g/100 gdb) | 5.54 ± 0.23a | 1.77 ± 0.12b |

| Protein (g/100 gdb) | 3.24 ± 0.15b | 3.59 ± 0.10a |

| Ash (g/100 gdb) | 52.88 ± 0.95b | 59.28 ± 0.93a |

| Carbohydrates (g/100 gdb) | 38.11 ± 1.95a | 35.02 ± 1.76b |

| Hydrolyzed polyphenols (mgGAE/gdm) | 45.76b | 76.22a |

| Condensed polyphenols (mgCE/gdm) | 10.97b | 47.95a |

| Total polyphenol content (mg/gdm) | 56.73b | 124.17a |

| Antioxidant activity: | ||

| DPPH (mgTE/gdm) | 266.63b | 444.64a |

| ABTS (mgTE/gdm) | 258.18b | 498.46a |

| FRAP (mgFe+2/gdm) | 354.03b | 551.13a |

| # | RT | [M-H]- | Bioactive compound | Molecular formula | Family | 0 h | 12 h SSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UA | UA | ||||||

| 1 | 10.41 | 342.5 | 5-O-Galloylquinic acid | C14H16O10 | Hydroxybenzoic acids | 0.026 | 0.343 |

| 2 | 15.02 | 798.4 | Ellagic acid derivate | Hydroxybenzoic acids | 0.136 | 1.539 | |

| 3 | 17.64 | 494.7 | Unidentified | 0.373 | 2.479 | ||

| 4 | 18.51 | 1118.1 | Unidentified | 0.384 | 2.451 | ||

| 5 | 20.51 | 632.6 | Corilagin | C27H22O18 | Ellagitannins | 0.747 | 2.501 |

| 6 | 24.18 | 782.4 | Gallagyl-hexoside | C34H22O22 | Ellagitannins | 0.338 | ND |

| 7 | 24.62 | 968.1 | Lagerstannin B derivate | Ellagitannins | ND | 2.458 | |

| 8 | 25.79 | 952.2 | Geraniin | C41H28O27 | Ellagitannins | 0.377 | 2.307 |

| 9 | 28.84 | 300.6 | Ellagic acid | C14H6O8 | Hydroxybenzoic acid dimers | 0.247 | 2.155 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).