Submitted:

26 July 2023

Posted:

28 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

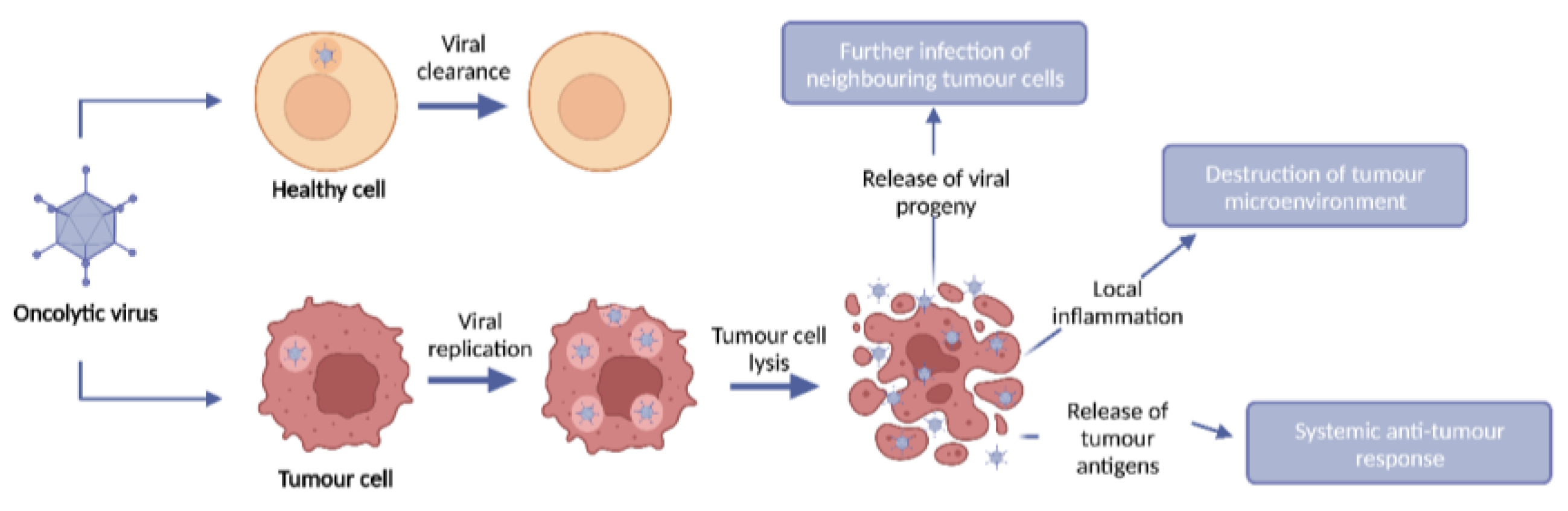

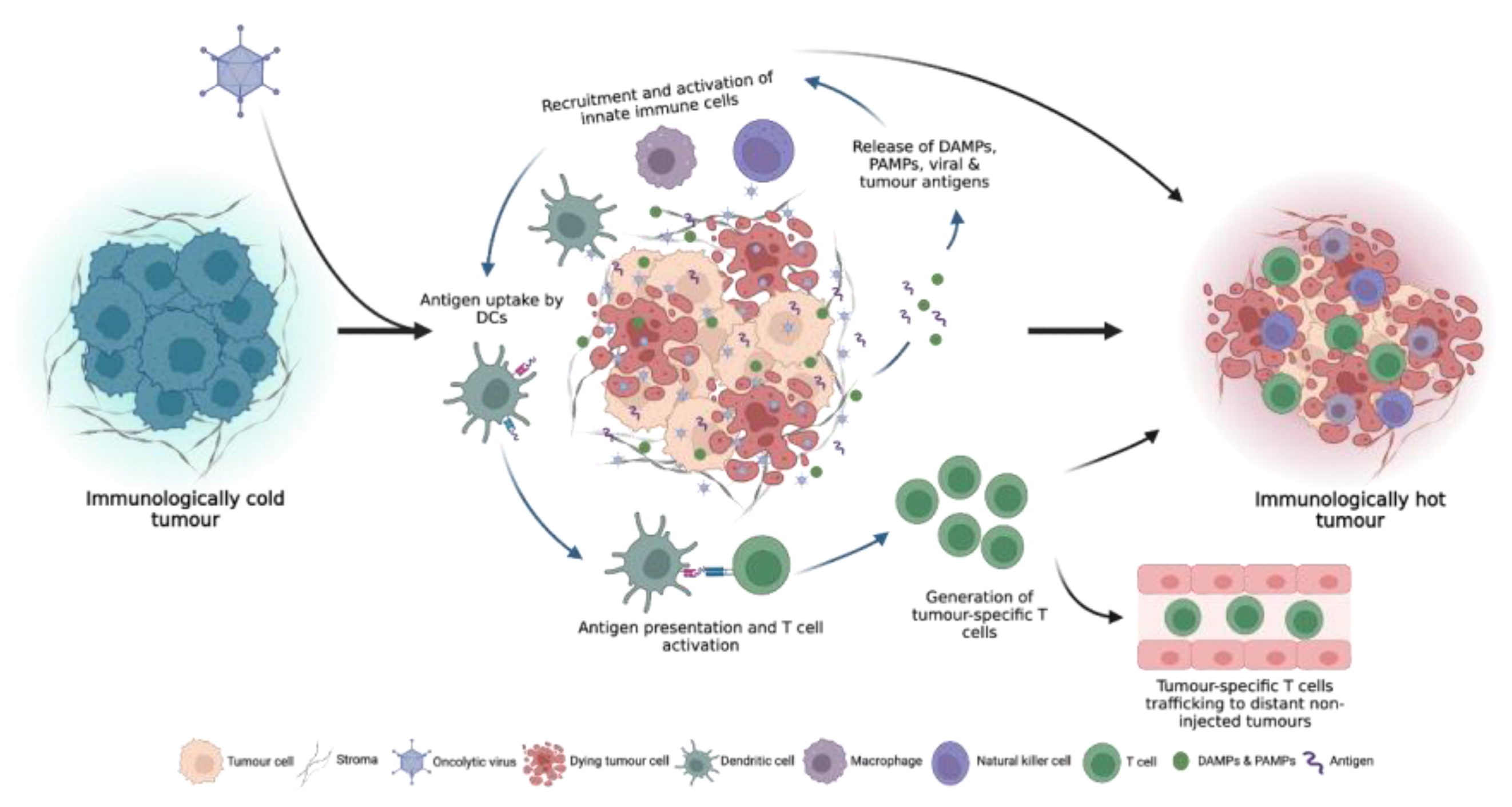

2. Oncolytic viruses

2.1. Turning cold tumours hot: the OV immune response

3. Oncolytic virus monotherapy

4. Combined OV and ICI therapy

4.1. Neoadjuvant therapies

4.1.2. Markers of response

4.1.3. Adverse events

4.2. OVs encoding ICIs

4.2.1. Additional targets

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dyck, L.; Mills, K.H.G. Immune Checkpoints and Their Inhibition in Cancer and Infectious Diseases. European Journal of Immunology 2017, 47, 765–779. [CrossRef]

- Maleki Vareki, S. High and Low Mutational Burden Tumors versus Immunologically Hot and Cold Tumors and Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2018, 6, 4–8. [CrossRef]

- Harrington, K.; Freeman, D.J.; Kelly, B.; Harper, J.; Soria, J.C. Optimizing Oncolytic Virotherapy in Cancer Treatment. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2019, 18, 689–706. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.K.; Hong, J.; Yun, C.O. Oncolytic Viruses and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Preclinical Developments to Clinical Trials. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ramachandran, M.; Jin, C.; Quijano-Rubio, C.; Martikainen, M.; Yu, D.; Essand, M. Characterization of Virus-Mediated Immunogenic Cancer Cell Death and the Consequences for Oncolytic Virus-Based Immunotherapy of Cancer. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Bommareddy, P.K.; Shettigar, M.; Kaufman, H.L. Integrating Oncolytic Viruses in Combination Cancer Immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology 2018, 18, 498–513. [CrossRef]

- Hotte, S.J.; Lorence, R.M.; Hirte, H.W.; Polawski, S.R.; Bamat, M.K.; O’Neil, J.D.; Roberts, M.S.; Groene, W.S.; Major, P.P. An Optimized Clinical Regimen for the Oncolytic Virus PV701. Clinical Cancer Research 2007, 13, 977–985. [CrossRef]

- Heinzerling, L.; Künzi, V.; Oberholzer, P.A.; Kündig, T.; Naim, H.; Dummer, R. Oncolytic Measles Virus in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas Mounts Antitumor Immune Responses in Vivo and Targets Interferon-Resistant Tumor Cells. Blood 2005, 106, 2287–2294. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, Y.A.; Wang, E.; Chen, N.; Danner, R.L.; Munson, P.J.; Marincola, F.M.; Szalay, A.A. Eradication of Solid Human Breast Tumors in Nude Mice with an Intravenously Injected Light-Emitting Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus. Cancer Research 2007, 67, 10038–10046. [CrossRef]

- Felt, S.A.; Grdzelishvili, V.Z. Recent Advances in Vesicular Stomatitis Virus-Based Oncolytic Virotherapy: A 5-Year Update. J Gen Virol 2017, 98, 2895–2911. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, V.; Hoeben, R.C.; van den Wollenberg, D.J.M. Exploring Reovirus Plasticity for Improving Its Use as Oncolytic Virus. Viruses 2015, 8, 4. [CrossRef]

- Geisler, A.; Hazini, A.; Heimann, L.; Kurreck, J.; Fechner, H. Coxsackievirus B3—Its Potential as an Oncolytic Virus. Viruses 2021, 13, 718. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, H.L.; Kohlhapp, F.J.; Zloza, A. Oncolytic Viruses: A New Class of Immunotherapy Drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2015, 14, 642–662. [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, T.G.; Bates, E.A.; Parker, A.L. Hitting the Target but Missing the Point: Recent Progress towards Adenovirus-Based Precision Virotherapies. Cancers 2020, 12, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Shalhout, S.Z.; Miller, D.M.; Emerick, K.S.; Kaufman, H.L. Therapy with Oncolytic Viruses: Progress and Challenges. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2023, 20, 160–177. [CrossRef]

- Vesely, M.D.; Kershaw, M.H.; Schreiber, R.D.; Smyth, M.J. Natural Innate and Adaptive Immunity to Cancer. Annual Review of Immunology 2011, 29, 235–271. [CrossRef]

- Twumasi-Boateng, K.; Pettigrew, J.L.; Kwok, Y.Y.E.; Bell, J.C.; Nelson, B.H. Oncolytic Viruses as Engineering Platforms for Combination Immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer 2018, 18, 419–432. [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Wei, J. Combining Oncolytic Viruses With Cancer Immunotherapy: Establishing a New Generation of Cancer Treatment. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Miao, J.M.; Wang, Y.Y.; Fan, Z.; Kong, X.B.; Yang, L.; Cheng, G. Oncolytic Viruses Combined with Immune Checkpoint Therapy for Colorectal Cancer Is a Promising Treatment Option. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tan, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Kong, X.; Meng, J.; Yang, L.; Cen, S. The Gamble between Oncolytic Virus Therapy and IFN. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13.

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Qian, L.; Wang, P. Oncolytic Virotherapy Reverses the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment and Its Potential in Combination with Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell International 2021, 21, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Coffelt, S.B.; Wellenstein, M.D.; De Visser, K.E. Neutrophils in Cancer: Neutral No More. Nature Reviews Cancer 2016, 16, 431–446. [CrossRef]

- Hofman, L.; Lawler, S.E.; Lamfers, M.L.M. The Multifaceted Role of Macrophages in Oncolytic Virotherapy. Viruses 2021, 13, 1570. [CrossRef]

- Prestwich, R.; Errington, F.; Ilett, E.; Morgan, R.; Scott, K.; Kottke, T.; Thompson, J.; Morrison, E.; Harrington, K.; Pandha, H.; et al. Tumor Infection by Oncolytic Reovirus Primes Adaptive Anti-Tumor Immunity. Clin Cancer Res 2008, 14, 7358–7366. [CrossRef]

- Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Collichio, F.; Harrington, K.J.; Middleton, M.R.; Downey, G.; Öhrling, K.; Kaufman, H.L. Final Analyses of OPTiM: A Randomized Phase III Trial of Talimogene Laherparepvec versus Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor in Unresectable Stage III-IV Melanoma. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2019, 7, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Todo, T.; Ito, H.; Ino, Y.; Ohtsu, H.; Ota, Y.; Shibahara, J.; Tanaka, M. Intratumoral Oncolytic Herpes Virus G47∆ for Residual or Recurrent Glioblastoma: A Phase 2 Trial. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 1630–1639. [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Reid, T.; Ruo, L.; Breitbach, C.J.; Rose, S.; Bloomston, M.; Cho, M.; Lim, H.Y.; Chung, H.C.; Kim, C.W.; et al. Randomized Dose-Finding Clinical Trial of Oncolytic Immunotherapeutic Vaccinia JX-594 in Liver Cancer. Nature Medicine 2013, 19, 329–336. [CrossRef]

- Holloway, R.W.; Kendrick, J.E.; Stephens, A.; Kennard, J.; Burt, J.; LeBlanc, J.; Sellers, K.; Smith, J.; Coakley, S. Phase 1b Study of Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus GL-ONC1 in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer (ROC). JCO 2018, 36, 5577–5577. [CrossRef]

- Streby, K.A.; Currier, M.A.; Triplet, M.; Ott, K.; Dishman, D.J.; Vaughan, M.R.; Ranalli, M.A.; Setty, B.; Skeens, M.A.; Whiteside, S.; et al. First-in-Human Intravenous Seprehvir in Young Cancer Patients: A Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Mol Ther 2019, 27, 1930–1938. [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.F.; Conrad, C.; Gomez-Manzano, C.; Alfred Yung, W.K.; Sawaya, R.; Weinberg, J.S.; Prabhu, S.S.; Rao, G.; Fuller, G.N.; Aldape, K.D.; et al. Phase I Study of DNX-2401 (Delta-24-RGD) Oncolytic Adenovirus: Replication and Immunotherapeutic Effects in Recurrent Malignant Glioma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018, 36, 1419–1427. [CrossRef]

- Galanis, E.; Hartmann, L.C.; Cliby, W.A.; Long, H.J.; Prema, P.; Barrette, B.A.; Kaur, J.S.; Jr, P.J.H.; Aderca, I.; Zollman, P.J.; et al. Phase I Trial of Intraperitoneal Administration of an Oncolytic Measles Virus Strain Engineered to Express Carcinoembryonic Antigen for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Research 2010, 70, 875–882. [CrossRef]

- Ranki, T.; Pesonen, S.; Hemminki, A.; Partanen, K.; Kairemo, K.; Alanko, T.; Lundin, J.; Linder, N.; Turkki, R.; Ristimäki, A.; et al. Phase I Study with ONCOS-102 for the Treatment of Solid Tumors - an Evaluation of Clinical Response and Exploratory Analyses of Immune Markers. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2016, 4, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Ross, M.I.; Agarwala, S.S.; Taylor, M.H.; Vetto, J.T.; Neves, R.I.; Daud, A.; Khong, H.T.; Ungerleider, R.S.; Tanaka, M. Efficacy and Genetic Analysis for a Phase II Multicenter Trial of HF10, a Replication-Competent HSV-1 Oncolytic Immunotherapy, and Ipilimumab Combination Treatment in Patients with Stage IIIb-IV Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018, 36, 9541–9541. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Peng, K.W.; Witzig, T.E.; Broski, S.M.; Villasboas, J.C.; Paludo, J.; Patnaik, M.; Rajkumar, V.; Dispenzieri, A.; Leung, N.; et al. Clinical Activity of Single-Dose Systemic Oncolytic VSV Virotherapy in Patients with Relapsed Refractory T-Cell Lymphoma. Blood Advances 2022, 6, 3268–3279. [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Gross, N.D.; Nemunaitis, J.J.; Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Argiris, A.; Ohr, J.; Vetto, J.T.; Senzer, N.N.; Bedell, C.; Ungerleider, R.S.; et al. Phase I Trial of Intratumoral Therapy Using HF10, an Oncolytic HSV-1, Demonstrates Safety in HSV+/HSV- Patients with Refractory and Superficial Cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2014, 32, 6082–6082. [CrossRef]

- Markert, J.M.; Razdan, S.N.; Kuo, H.C.; Cantor, A.; Knoll, A.; Karrasch, M.; Nabors, L.B.; Markiewicz, M.; Agee, B.S.; Coleman, J.M.; et al. A Phase 1 Trial of Oncolytic HSV-1, G207, given in Combination with Radiation for Recurrent GBM Demonstrates Safety and Radiographic Responses. Molecular Therapy 2014, 22, 1048–1055. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.L.; Wang, X.; Lian, B.; Ji, Q.; Zhou, L.; Chi, Z.; Si, L.; Sheng, X.; Kong, Y.; Yu, J.; et al. OrienX010, an Oncolytic Virus, in Patients with Unresectable Stage IIIC-IV Melanoma: A Phase Ib Study. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, Y.; Tazawa, H.; Tanabe, S.; Kanaya, N.; Noma, K.; Koujima, T.; Kashima, H.; Kato, T.; Kuroda, S.; Kikuchi, S.; et al. Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of Endoscopic Intratumoral Injection of OBP-301 (Telomelysin) with Radiotherapy in Oesophageal Cancer Patients Unfit for Standard Treatments. European Journal of Cancer 2021, 153, 98–108. [CrossRef]

- Musher, B.L.; Smaglo, B.G.; Abidi, W.; Othman, M.; Patel, K.; Jawaid, S.; Jing, J.; Brisco, A.; Wenthe, J.; Eriksson, E.; et al. A Phase I/II Study of LOAd703, a TMZ-CD40L/4-1BBL-Armed Oncolytic Adenovirus, Combined with Nab-Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022, 40, 4138–4138. [CrossRef]

- Annels, N.E.; Mansfield, D.; Arif, M.; Ballesteros-Merino, C.; Simpson, G.R.; Denyer, M.; Sandhu, S.S.; Melcher, A.A.; Harrington, K.J.; Davies, B.; et al. Phase I Trial of an ICAM-1-Targeted Immunotherapeutic-Coxsackievirus A21 (CVA21) as an Oncolytic Agent Against Non Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 25, 5818–5831. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, V.; Barretina-Ginesta, M.P.; García-Donas, J.; Jayson, G.C.; Roxburgh, P.; Vázquez, R.M.; Michael, A.; Antón-Torres, A.; Brown, R.; Krige, D.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the Tumor-Selective Adenovirus Enadenotucirev with or without Paclitaxel in Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer: A Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2021, 9, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bazan-Peregrino, M.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Laquente, B.; Álvarez, R.; Mato-Berciano, A.; Gimenez-Alejandre, M.; Morgado, S.; Rodríguez-García, A.; Maliandi, M.V.; Riesco, M.C.; et al. VCN-01 Disrupts Pancreatic Cancer Stroma and Exerts Antitumor Effects. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2021, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, G.K.; Johnston, J.M.; Bag, A.K.; Bernstock, J.D.; Li, R.; Aban, I.; Kachurak, K.; Nan, L.; Kang, K.-D.; Totsch, S.; et al. Oncolytic HSV-1 G207 Immunovirotherapy for Pediatric High-Grade Gliomas. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384, 1613–1622. [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, Y.; Kasuya, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Kawashima, H.; Ohno, E.; Villalobos, I.B.; Naoe, Y.; Ichinose, T.; Koyama, N.; Tanaka, M.; et al. A Phase I Clinical Trial of EUS-Guided Intratumoral Injection of the Oncolytic Virus, HF10 for Unresectable Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, J.; Tang, J.; Hu, S.; Luo, S.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, F.; Tan, S.; Ying, J.; Chang, Q.; et al. Intratumoral OH2, an Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus 2, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors: A Multicenter, Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2021, 9, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mayo Clinic Phase I Trial of a Measles Virus Derivative Producing CEA (MV-CEA) in Patients With Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM); clinicaltrials.gov, 2019;

- Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Gil Martín, M.; Alvarez Gallego, R.; Macarulla Mercade, T.; Riesco Martinez, M.C.; Guillen-Ponce, C.; Vidal, N.; Real, F.X.; Moreno, R.; Maliandi, V.; et al. Systemic Administration of the Hyaluronidase-Expressing Oncolytic Adenovirus VCN-01 in Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: First-in-Human Clinical Trial. Annals of Oncology 2019, 30, v271–v272. [CrossRef]

- Packiam, V.T.; Lamm, D.L.; Barocas, D.A.; Trainer, A.; Fand, B.; Davis, R.L.; Clark, W.; Kroeger, M.; Dumbadze, I.; Chamie, K.; et al. An Open Label, Single-Arm, Phase II Multicenter Study of the Safety and Efficacy of CG0070 Oncolytic Vector Regimen in Patients with BCG-Unresponsive Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Interim Results. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2018, 36, 440–447. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Sun, Z.J. Fueling Immune Checkpoint Blockade with Oncolytic Viruses: Current Paradigms and Challenges Ahead. Cancer Letters 2022, 550, 215937–215937. [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, E.I.; Desai, A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways Similarities, Differences, and Implications of Their Inhibition. American Journal of Clinical Oncology: Cancer Clinical Trials 2016, 39, 98–106. [CrossRef]

- De Silva, P.; Aiello, M.; Gu-Trantien, C.; Migliori, E.; Willard-Gallo, K.; Solinas, C. Targeting CTLA-4 in Cancer: Is It the Ideal Companion for PD-1 Blockade Immunotherapy Combinations? International Journal of Cancer 2021, 149, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Keir, M.E.; Butte, M.J.; Freeman, G.J.; Sharpe, A.H. PD-1 and Its Ligands in Tolerance and Immunity. Annual Review of Immunology 2008, 26, 677–704. [CrossRef]

- Schalper, K.A.; Kaftan, E.; Herbst, R.S. Predictive Biomarkers for PD-1 Axis Therapies: The Hidden Treasure or a Call for Research. Clinical Cancer Research 2016, 22, 2102–2104.

- Doroshow, D.B.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Hastings, K.; Politi, K.; Rimm, D.L.; Chen, L.; Melero, I.; Schalper, K.A.; Herbst, R.S. Immunotherapy in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: Facts and Hopes. Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 25, 4592–4602. [CrossRef]

- Kontermann, R.E.; Ungerechts, G.; Nettelbeck, D.M. Viro-Antibody Therapy: Engineering Oncolytic Viruses for Genetic Delivery of Diverse Antibody-Based Biotherapeutics. mAbs 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Steinberg, G.; Uchio, E.; Lamm, D.; Paras, S.; Kamat, A.; Bivalacqua, T.; Packiam, V.; Chisamore, M.; McAdory, J.; et al. 666 Phase 2, Single Arm Study of CG0070 Combined with Pembrolizumab in Patients with Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC) Unresponsive to Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG).; BMJ Specialist Journals 2022.

- Nassiri, F.; Patil, V.; Yefet, L.S.; Singh, O.; Liu, J.; Dang, R.M.A.; Yamaguchi, T.N.; Daras, M.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Colman, H.; et al. Oncolytic DNX-2401 Virotherapy plus Pembrolizumab in Recurrent Glioblastoma: A Phase 1/2 Trial. Nat Med 2023, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Chesney, J.A.; Ribas, A.; Long, G.V.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Dummer, R.; Puzanov, I.; Hoeller, C.; Gajewski, T.F.; Gutzmer, R.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Global Phase III Trial of Talimogene Laherparepvec Combined with Pembrolizumab for Advanced Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023, 41, 528–540. [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M.G.; Wang, D.; Harb, W.; Rosen, L.; Mahadevan, D.; Berlin, J.D.; Basciano, P.; Brown, R.; Arogundade, O.; Cox, C.; et al. SPICE, a Phase I Study of Enadenotucirev in Combination with Nivolumab in Tumours of Epithelial Origin: Analysis of the Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients in the Dose Escalation Phase. Annals of Oncology 2019, 30, v231–v231. [CrossRef]

- Lillie, T.; Stone, A.; Lockwood, S.; Brown, R.; Fox, A.; Bournazou, E.; Beadle, J. 329 Prolonged Overall Survival (OS) in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (MCRC) in SPICE, a Phase I Study of Enadenotucirev in Combination with Nivolumab.; 2020; Vol. 8, p. A202.1-A202.

- Krige, D.; Fakih, M.; Rosen, L.; Wang, D.; Harb, W.; Babiker, H.; Berlin, J.; Di Genova, G.; Miles, D.; Mark, P.; et al. Combining enadenotucirev and nivolumab increased tumour immune cell infiltration/ activation in patients with microsatellite- stable/instability-low metastatic colorectal cancer in a phase 1 study. 2021; Vol. 5, pp. 2021–2021.

- Shoushtari, A.N.; Olszanski, A.J.; Nyakas, M.; Hornyak, T.J.; Wolchok, J.D.; Levitsky, V.; Kuryk, L.; Hansen, T.B.; Jäderberg, M. Pilot Study of ONCOS-102 and Pembrolizumab: Remodeling of the Tumor Microenvironment and Clinical Outcomes in Anti-PD-1-Resistant Advanced Melanoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2023, 29, 100–109. [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Dummer, R.; Puzanov, I.; VanderWalde, A.; Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Michielin, O.; Olszanski, A.J.; Malvehy, J.; Cebon, J.; Fernandez, E.; et al. Oncolytic Virotherapy Promotes Intratumoral T Cell Infiltration and Improves Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cell 2017, 170, 1109-1119.e10. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.M.; Antonescu, C.R.; Bowler, T.; Munhoz, R.; Chi, P.; Dickson, M.A.; Gounder, M.M.; Keohan, M.L.; Movva, S.; Dholakia, R.; et al. Objective Response Rate Among Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Sarcoma Treated With Talimogene Laherparepvec in Combination With Pembrolizumab: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology 2020, 6, 402–408. [CrossRef]

- Monge, C.; Xie, C.; Myojin, Y.; Coffman, K.; Hrones, D.M.; Wang, S.; Hernandez, J.M.; Wood, B.J.; Levy, E.B.; Juburi, I.; et al. Phase I/II Study of PexaVec in Combination with Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2023, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chesney, J.; Puzanov, I.; Collichio, F.; Singh, P.; Milhem, M.M.; Glaspy, J.; Hamid, O.; Ross, M.; Friedlander, P.; Garbe, C.; et al. Randomized, Open-Label Phase II Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Talimogene Laherparepvec in Combination with Ipilimumab versus Ipilimumab Alone in Patients with Advanced, Unresectable Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018, 36, 1658–1667. [CrossRef]

- Fransen, M.F.; Van Der Sluis, T.C.; Ossendorp, F.; Arens, R.; Melief, C.J.M. Controlled Local Delivery of CTLA-4 Blocking Antibody Induces CD8 + T-Cell-Dependent Tumor Eradication and Decreases Risk of Toxic Side Effects. Clinical Cancer Research 2013, 19, 5381–5389. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, D.; Chen, Z.; Gu, Z. Local and Targeted Delivery of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapeutics. Acc Chem Res 2020, 53, 2521–2533. [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Shi, G.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, J.F.; Tian, H.W.; Wei, Y.Q.; Deng, H.; Yu, D.C. Tumor-Specific Oncolytic Adenoviruses Expressing Granulocyte Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor or Anti-CTLA4 Antibody for the Treatment of Cancers. Cancer Gene Therapy 2014, 21, 340–348. [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.D.; Hemminki, O.; Diaconu, I.; Hirvinen, M.; Bonetti, A.; Guse, K.; Escutenaire, S.; Kanerva, A.; Pesonen, S.; Löskog, A.; et al. Targeted Cancer Immunotherapy with Oncolytic Adenovirus Coding for a Fully Human Monoclonal Antibody Specific for CTLA-4. Gene Therapy 2012, 19, 988–998. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Kuncheria, L.; Roulstone, V.; Kyula, J.N.; Mansfield, D.; Bommareddy, P.K.; Smith, H.; Kaufman, H.L.; Harrington, K.J.; Coffin, R.S. Development of a New Fusion-Enhanced Oncolytic Immunotherapy Platform Based on Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2019, 7, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.R.; Vijayakumar, G.; Palese, P. A Recombinant Antibody-Expressing Influenza Virus Delays Tumor Growth in a Mouse Model. Cell Reports 2018, 22, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Wang, X.; Xing, M.; Yang, X.; Wu, M.; Shi, H.; Zhu, C.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Tang, S.; et al. Intratumoral Delivery of a Novel Oncolytic Adenovirus Encoding Human Antibody against PD-1 Elicits Enhanced Antitumor Efficacy. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 2022, 25, 236–248. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Ren, W.; Luo, Y.; Li, S.; Chang, Y.; Li, L.; Xiong, D.; Huang, X.; Xu, Z.; Yu, Z.; et al. Intratumoral Delivery of a PD-1-Blocking ScFv Encoded in Oncolytic HSV-1 Promotes Antitumor Immunity and Synergizes with TIGIT Blockade. Cancer Immunology Research 2020, 8, 632–648. [CrossRef]

- Ju, F.; Luo, Y.; Lin, C.; Jia, X.; Xu, Z.; Tian, R.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chang, Y.; Huang, X.; et al. Oncolytic Virus Expressing PD-1 Inhibitors Activates a Collaborative Intratumoral Immune Response to Control Tumor and Synergizes with CTLA-4 or TIM-3 Blockade. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2022, 10, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Sun, C.; Zhu, W.; Yin, Y.; Li, X. Enhanced Anti-Tumor Response Elicited by a Novel Oncolytic HSV-1 Engineered with an Anti-PD-1 Antibody. Cancer Letters 2021, 518, 49–58. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, X.; Feng, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Duan, X.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, K. Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy of a Novel Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Encoding an Antibody Against Programmed Cell Death 1. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 2019, 15, 201–213. [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, A.; Chaurasiya, S.; Park, A.K.; Lu, J.; Kim, S.I.; Warner, S.G.; Von Hoff, D.; Fong, Y. Novel Chimeric Immuno-Oncolytic Virus CF33-HNIS-AntiPDL1 for the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2020, 230, 709–717. [CrossRef]

- Chaurasiya, S.; Yang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, J.; Valencia, H.; Kim, S.I.; Woo, Y.; Warner, S.G.; Olafsen, T.; Zhao, Y.; et al. A Comprehensive Preclinical Study Supporting Clinical Trial of Oncolytic Chimeric Poxvirus CF33-HNIS-Anti-PD-L1 to Treat Breast Cancer. Molecular Therapy - Methods and Clinical Development 2022, 24, 102–116. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Chaurasiya, S.; Park, A.K.; Kim, I.; Priceman, S.; Fong, Y.; Jung, A.; Lu, J. Development of the Oncolytic Virus , CF33 , and Its Derivatives for Peritoneal- Directed Treatment of Gastric Cancer Peritoneal Metastases. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2023, 11, e006280–e006280. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wu, M.; Liang, M.; Xiong, S.; Dong, C. A Novel Oncolytic Virus Engineered with PD-L1 ScFv Effectively Inhibits Tumor Growth in a Mouse Model. Cellular and Molecular Immunology 2019, 16, 780–782. [CrossRef]

- Veinalde, R.; Pidelaserra-Martí, G.; Moulin, C.; Jeworowski, L.M.; Küther, L.; Buchholz, C.J.; Jäger, D.; Ungerechts, G.; Engeland, C.E. Oncolytic Measles Vaccines Encoding PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Blocking Antibodies to Increase Tumor-Specific T Cell Memory. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 2022, 24, 43–58. [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.L.; Wang, L.P.; Dong, S.H.; Sun, F.; Cheng, J.X.; Yang, X.L.; Zhang, S.G.; Wang, X.L.; Wang, X.X.; Yang, P.H. A Recombinant Influenza Virus with a CTLA4-Specific ScFv Inhibits Tumor Growth in a Mouse Model. Cell Biology International 2021, 45, 1202–1210. [CrossRef]

- Kleinpeter, P.; Fend, L.; Thioudellet, C.; Geist, M.; Sfrontato, N.; Koerper, V.; Fahrner, C.; Schmitt, D.; Gantzer, M.; Remy-Ziller, C.; et al. Vectorization in an Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus of an Antibody, a Fab and a ScFv against Programmed Cell Death -1 (PD-1) Allows Their Intratumoral Delivery and an Improved Tumor-Growth Inhibition. OncoImmunology 2016, 5, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, G.; McCroskery, S.; Palese, P. Engineering Newcastle Disease Virus as an Oncolytic Vector for Intratumoral Delivery of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Immunocytokines. Journal of Virology 2020, 94. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.; Scialò, F.; Passariello, M.; Leggiero, E.; D’Agostino, A.; Tripodi, L.; Gentile, L.; Bianco, A.; Castaldo, G.; Cerullo, V.; et al. Oncolytic Adenoviral Vector-Mediated Expression of an Anti-PD-L1-ScFv Improves Anti-Tumoral Efficacy in a Melanoma Mouse Model. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Passaro, C.; Alayo, Q.; De Laura, I.; McNulty, J.; Grauwet, K.; Ito, H.; Bhaskaran, V.; Mineo, M.; Lawler, S.E.; Shah, K.; et al. Arming an Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 with a Single-Chain Fragment Variable Antibody against PD-1 for Experimental Glioblastoma Therapy. Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 25, 290–299. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, A.; Chaurasiya, S.; Park, A.K.; Lu, J.; Kim, S.I.; Warner, S.G.; Yuan, Y.C.; Liu, Z.; Han, H.; et al. CF33-HNIS-AntiPDL1 Virus Primes Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma for Enhanced Anti-PD-L1 Therapy. Cancer Gene Therapy 2022, 29, 722–733. [CrossRef]

- Engeland, C.E.; Grossardt, C.; Veinalde, R.; Bossow, S.; Lutz, D.; Kaufmann, J.K.; Shevchenko, I.; Umansky, V.; Nettelbeck, D.M.; Weichert, W.; et al. CTLA-4 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade Enhances Oncolytic Measles Virus Therapy. Molecular Therapy 2014, 22, 1949–1959. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Kang, X.; Chen, K.S.; Jehng, T.; Jones, L.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.F.; Chen, S.Y. An Engineered Oncolytic Virus Expressing PD-L1 Inhibitors Activates Tumor Neoantigen-Specific T Cell Responses. Nature Communications 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, G.; Palese, P.; Goff, P.H. Oncolytic Newcastle Disease Virus Expressing a Checkpoint Inhibitor as a Radioenhancing Agent for Murine Melanoma. EBioMedicine 2019, 49, 96–105. [CrossRef]

- Barrueto, L.; Caminero, F.; Cash, L.; Makris, C.; Lamichhane, P.; Deshmukh, R.R. Resistance to Checkpoint Inhibition in Cancer Immunotherapy. Transl Oncol 2020, 13, 100738. [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Verma, R.; Sznol, M.; Boddupalli, C.S.; Gettinger, S.N.; Kluger, H.; Callahan, M.; Wolchok, J.D.; Halaban, R.; Dhodapkar, M.V. Combination Therapy with Anti–CTLA-4 and Anti–PD-1 Leads to Distinct Immunologic Changes in Vivo. The Journal of Immunology 2015, 194, 950–959. [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J.-M.; Zarour, H.M. TIGIT in Cancer Immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8, e000957. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Wei, M.; He, B.; Chen, A.; Wang, S.; Kong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, G.; Xu, T.; Wu, J.; et al. Enhanced Antitumor Efficacy of a Novel Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus Encoding a Fully Monoclonal Antibody against T-Cell Immunoglobulin and ITIM Domain (TIGIT). EBioMedicine 2021, 64, 103240–103240. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Wei, M.; Xu, T.; Kong, L.; He, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Dong, J.; Wei, J. An Engineered Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus Encoding a Single-Chain Variable Fragment against TIGIT Induces Effective Antitumor Immunity and Synergizes with PD-1 or LAG-3 Blockade. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9, e002843. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; Ha, S.-J.; Kim, H.R. Clinical Insights Into Novel Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12.

- Popat, S.; Grohé, C.; Corral, J.; Reck, M.; Novello, S.; Gottfried, M.; Radonjic, D.; Kaiser, R. Anti-Angiogenic Agents in the Age of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Do They Have a Role in Non-Oncogene-Addicted Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer? Lung Cancer 2020, 144, 76–84. [CrossRef]

- Seidel, J.A.; Otsuka, A.; Kabashima, K. Anti-PD-1 and Anti-CTLA-4 Therapies in Cancer: Mechanisms of Action, Efficacy, and Limitations. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 86. [CrossRef]

| Virus | Diameter | Genome | Genome size | Transgene capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus | 90-100 nm | dsDNA | 30-36 kb | ~2.5 kb |

| Herpes simplex virus | 200 nm | dsDNA | ~152 kb | ~30 kb |

| Vaccinia virus | 350 nm | dsDNA | ~192 kb | ~25 kb |

| Influenza A virus | 80-120 nm | ss(-)RNA | ~13.5 kb | ~2.4 kb |

| Newcastle disease virus | 100-500 nm | ss(-)RNA | ~15 kb | ~4.5 kb |

| Measles virus | 100-200 nm | ss(-)RNA | ~16 kb | ~6 kb |

| Vesicular stomatitis virus | 70 nm | ss(-)RNA | ~11.1 kb | ~4.5 kb |

| Coxsackie virus | 22-30 nm | ss(+)RNA | ~7.5 kb | < 1 kb |

| Reovirus | 80 nm | dsRNA | 24 kb | ~1.5 kb |

| Virus | OV | Engineered specificity | Transgene | Indication | Delivery | Key findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus | CG0070 | Ad5 with E1a under E2F-1 promoter | GM-CSF | NMIBC Phase II |

IVS | 47% 6-month CR; 29% 12-month CR | [48] |

| DNX-2401 | Ad5 with 24 bp E1a deletion; RGD integrin-binding motif | GBM Phase I |

IT | 20% >3-year survival; 12% demonstrated >95% tumour reduction; increased tumour CD8+ and T-bet+ cells; decreased TIM-3+ cells | [30] | ||

| EnAd | Ad11p/3 chimera generated through directed evolution | Ovarian Phase I |

IV | 64% PFS; 10% ORR; 35% achieved stable disease; 65% saw reduction in tumour burden; 83.3% demonstrated increased CD8+ TILs | [41] | ||

| LoAd-703 | Ad5 with 24 bp E1a deletion; pseudotyped Ad35 knob |

TMZ-CD40L; 4-1BBL |

PDAC Phase I/II |

IT | 44% ORR; 94% DCR; OS 8.7 months; increased effector memory T cells; decreased Tregs and MDSCs; | [39] | |

| ONCOS-102 | Ad5 with 24 bp E1a deletion; pseudotyped Ad3 knob |

GM-CSF | Solid tumours Phase I |

IT | Increase in TILs; increase in systemic tumour-specific CD8+ T cells; increased tumour PD-L1 expression | [32] | |

| Telomelysin | Ad5 with E1a under hTERT promoter | Oesophageal Phase I |

IT | 91.7% ORR; 83.3% Stage I and 60% Stage II/III CRR; increased tumour CD8+ T cells; increased tumour PD-L1 expression | [38] | ||

| VCN-01 | Ad5 with 24 bp E1a deletion; E2F1 promoter insertion; RGDK integrin-binding motif | Hyaluronidase | PDAC Phase I |

IT | Injected tumours reduced in size or remained stable; reduction in tumour stiffness | [42] | |

| IV | 40-45% ORR including 1 complete response; CD8+ T cell tumour infiltration and IDO upregulation in 64% of patients | [47] | |||||

| Coxsackie virus | CVA21 | NMIBC Phase I |

IVS | 1/15 demonstrated CR; CR patient demonstrated increased immune infiltration; viral protein detected in 86% of tumours with no viral protein seen in stroma; RNA-seq demonstrated increased intrinsic apoptotic cell death pathway and PD-L1, LAG-3 and IDO within the TME | [40] | ||

| Herpes simplex virus |

T-VEC | HSV1 with ICP34.5 deletion; US11 deletion | GM-CSF | Melanoma Phase III |

IT | Median OS 23.3 months; 19% DRR; 31.5% ORR; 50% demonstrated CR of which 88.5% were estimated to survive at 5-years; median time to CR 8.6 months Approved for the local treatment of unresectable metastatic stage IIIB/C–IVM1a melanoma in Europe and US |

[25] |

| G207 | HSV1 with ICP34.5 deletion; UL39 deletion; | GBM Phase I (+Rad) |

IT | Median OS 7.5 months; median PFS 2.5 months; 67% demonstrated stable or partial response at ≥ 1 time point | [36] | ||

| Paediatric glioma Phase I |

IT | Median OS 12.2 months; 18% demonstrated stable disease at 12 months; 36% still alive at 18 months; increased CD4+ and CD8+ T cell tumour infiltration | [43] | ||||

| G47∆ | G207 with additional α47 deletion; US11 promoter deletion | GBM Phase II |

IT | Median OS 20.2 months; median PFS 4.7 months; 84.2% survival at 12 months; stable disease in 18 patients at 2 years; increased CD4+, CD8+ and decreased Foxp3+ TIL Approvd for treatment of GBM in Japan |

[26] | ||

| HF10 | HSV1 with UL43, UL49.5, UL55 & UL56 deletions; Latency-associated transcripts deletions; UL53 & UL54 overexpression | Pancreatic cancer Phase I |

IT | Median OS 15.5 months; median PFS 6.3 months; 33.3% PR; 44.4% SD; 2 patients demonstrated surgical CR; 2 patients were alive at 3 year follow up; increased CD4+, CD8+ TILs | [44] | ||

| Superficial solid tumours Phase II |

IT | 33.3% SD; 1 patient demonstrated pathological CR after 4 months; 30-61% reduction in tumour size in those demonstrating responses | [35] | ||||

| Seprehvir | HSV1 with ICP34.5 deletion | Paediatric solid tumours Phase I |

IT | Median OS 7 months; 80% demonstrated SD at 14 days; 43% SD at 28 days | [29] | ||

| OrienX010 | HSV1 with ICP34.5 deletion; US12 deletion | GM-CSF | Melanoma Phase I |

IT | Median OS 19.2 months; median PFS 2.9 months; 54.6% of injected tumours regressed, 25.8% of which regressed by ≥30%; 54.1% of non-injected regional tumours regressed, 32.8% of which regressed by ≥30%; 1 distant non-injected metastases regressed by 58% | [37] | |

| OH2 | HSV2 with ICP34.5 & ICP47 deletion; | GM-CSF | Solid tumours Phase I/II |

IT | 1 PR; 33% stable disease; 79% saw increased CD8+ TILs; 86% increased CD3+ TILs; 71.4% increased PD-L1+ cells | [45] | |

| Newcastle disease virus | PV701 | Solid tumours Phase I |

IV | 61% PFS at 4 months; 33% OR; 1 CR cervical cancer; 2 PRs colorectal; 1 PR melanoma | [7] | ||

| Measles virus | MV-CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen | Ovarian cancer Phase I/II |

IP | Median OS 12.15 months; 67% SD; 36% demonstrated >30% tumour reduction | [8] | |

| GBM Phase I |

IT | Median OS 11.6 months; 59% 3-month PFS; 23% 6-month PFS | [46] | ||||

| MV-NIS | Sodium iodide symporter | Ovarian cancer Phase I |

IP | Median OS 26.2 months; 81% SD | [31] | ||

| Vaccinia virus | GL-ONC1 | Β-galactosidase; β-glucuronidase | Ovarian cancer Phase I |

IP | Median PFS 11.6 months; 78% 6-month PFS; 63% ORR; 52% CR; increased CD4+ & CD8+ TILs | [28] | |

| JX-594 | TK1 deletion | GM-CSF | HCC Phase II |

IT | Median OS 9 months; ~35% alive at 2 years; 46% demonstrated tumour control at 8 weeks; average 32.2% decrease in tumour size; increased tumour specific CD8+ TILs | [27] | |

| Vesicular stomatitis virus | VSV-IFNβ-NIS | IFN-β; sodium iodide symporter | TCL Phase I |

IV | 1 6-month PR; 1 20-month CR; 71.4% reduction in ≥1 tumour | [34] |

| Virus | OV | ICI | Indication | Key findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad | CG0070 (IVS) |

PD-1: Pembrolizumab |

NMIBC Phase II |

82% 6-month CR; 81% 9-month CR; 68% 12-month CR | |

| DNX-2401 (IT) |

GBM Phase II |

ORR 10.4%; 42.9% SD; 4.8% CR; 7.1% PR; 52.7% 12-month survival; 12.5 months median OS; 3 patients alive > 45 months | [57] | ||

| EnAd (IT) |

PD-1: Nivolumab |

mCRC Phase I |

Median OS 15.4 months (5 months placebo); median PFS 2.8 months; 85% demonstrated increased CD8+ TILs; 77% increased CD4+ TILs; 62% increased PD-L1+ TILs | [59–61] | |

| ONCOS-102 (IT) |

PD-1: Pembrolizumab |

Melanoma progressing post-PD-1 blockade Pilot |

35% ORR; 64% SD; 27% demonstrated CR in injected tumour 53% demonstrated reduction in ≥1 non-injected tumour; increased CD4+ & CD8+ TILs | [62] | |

| HSV | T-VEC (IT) |

PD-1: Pembrolizumab |

Melanoma Phase Ib |

82% demonstrated >50% reduction of injected tumours; 43% in non-injected tumours; 67% demonstrated increased CD8+ TILs; demonstrated increased systemic proliferating CD8+ T cells | [63] |

| Melanoma Phase III T-VEC+Pemb vs Pemb |

T+P: 17.9% CR; 48.6% ORR (CR/PR); 14.3 months PFS P: 11.6% CR; 41.3% ORR; 8.5 months PFS |

[58] | |||

| Sarcoma Phase II |

21% PR; 47% SD; median PFS 17.1 months; responders saw increased CD8+ TILs and CD8+ aggregates at tumour edge; non-responders saw no increase in CD8+ TILs or aggregates | [64] | |||

| CTLA-4: Ipilimumab |

Melanoma Phase II TVEC+Ipi vs Ipi |

T+I: 13% CR; 26% PR; 39% ORR (CR/PR); 8.2 months median PFS; 52% non-injected visceral tumour reduction I: 7% CR; 11% PR; 18% ORR; 6.4 months median PFS; 23% non-injected visceral tumour reduction |

[66] | ||

| HF10 (IT) |

CTLA-4: Ipilimumab |

Melanoma Phase II |

Median OS 26 months; median PFS 19 months; 68% SD; increased CD8+ and decreased CD4+ TILs | [33] | |

| VV | JX-594 (IT) |

CTLA-4: Tremelumab PD-L1: Durvalumab |

ICI refractory CRC Phase I/II |

J+D: Median OS 7.5 months; median PFS 2.3 months; 12.5% DCR J+D+T: Median OS 5.2 months; median PFS 2.1 months; 16.7% DCR Increased proliferating CD3+ TILs after OV treatment and again after ICI treatment; increased M1 macrophages in tumours |

[65] |

| OV | Target | ICI format | Indication | Key findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad5 | CTLA-4 mouse |

IgG2 | Melanoma NSCLC SCLC |

Subcutaneous mouse xenograft model with intravenous OV injection: significant 72% reduction in tumour growth compared to untreated tumours Subcutaneous mouse xenograft model with intratumoural OV injection: significant 3-fold decrease in tumour growth compared to untreated tumours |

[69] |

| Ad5/3 | CTLA-4 human |

IgG2 | NSCLC Prostate |

Subcutaneous T-cell-deficient mouse xenograft model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth compared to untreated; 43-fold increase in tumour anti-CTLA-4 antibody concentrations compared to systemic plasma In vitro human T cell activation assay: PBMCs from advanced solid cancer patients cultured in the presence of supernatant from OV-infected cells saw increase in T cell IL-2 and IFN-γ production |

[70] |

| HSV-1 | CTLA-4 & GM-CSF mouse |

scFv fused to mouse IgG1 | Lymphoma | Bilateral subcutaneous mouse xenograft model with single-sided intratumoural OV injection: decreased tumour growth in both injected and non-injected tumours (not significant) | [71] |

| IAV | CTLA-4 mouse |

scFV | Melanoma | Bilateral subcutaneous mouse xenograft model with single-sided intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth in both injected and non-injected tumours and prolonged survival compared to parental virus | [72] |

| IAV | CTLA-4 mouse | scFV | HCC | Spontaneous homograft model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to parental OV | [83] |

| NDV | CTLA-4 mouse |

scFV | Melanoma | Intradermal mouse tumour model with intratumoural OV injection: demonstrated the same efficacy as systemic CTLA-4 treatment plus parental NDV, with comparable tumour growth inhibition and prolonged survival | [91] |

| MV | CTLA-4 mouse | scFV-IgG1 Fc fusion | Melanoma | Subcutaneous synergic mouse tumour model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth compared to parental virus and untreated; significant increase in tumour T cell infiltration and a decrease in Treg infiltration compared to parental OV and untreated; increased splenocyte IFN-γ release upon re-stimulation with tumour cells in vitro compared to parental OV and untreated | [89] |

| Ad68 | PD-1 | IgG4 | Colorectal | Bilateral subcutaneous humanised PD-1 transgenic mouse tumour model with single-sided intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to parental OV and untreated, with successful tumour rejection upon rechallenge; significantly increased systemic CD8+ T cell and effector and central memory T cell proportions; significantly decreased PD-1+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proportions | [73] |

| HSV-1 | PD-1 mouse | scFv | HCC | Bilateral subcutaneous synergic mouse tumour model with single-sided intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth in both injected and non-injected tumours and greater long-term tumour growth inhibition compared to parental OV and untreated; successful tumour rejection upon rechallenge; significantly increased activated CD4+ and CD8+ cell tumour infiltration compared to parental OV; however, also saw significantly greater MDSC infiltration compared to parental OV | [74] |

| HSV-1 | PD-1 human | scFv | HCC | Orthotopic HCC xenograft tumour model with intravenous OV injection in humanised PD-1 transgenic mice: significantly decreased tumour growth and increased overall survival compared to parental OV and untreated mice, with all anti-PD-1 OV treated mice tumour free at 12 weeks Bilateral subcutaneous mouse xenograft tumour model with single-sided intratumoural OV injection in humanised PD-1 transgenic mice: significantly decreased tumour growth in both injected and non-injected tumours compared to parental OV and untreated; anti-PD-1 OV treated tumours demonstrated significantly reduced proportions of exhausted CD8+ T cell populations and increased effector memory CD8+ T cell populations compared to parental OV and untreated |

[75] |

| HSV-1 | PD-1 human | scFv | Melanoma | Bilateral subcutaneous mouse xenograft tumour model with intratumoural OV injection in humanised PD-1 transgenic mice: significantly decreased tumour growth compared to untreated and parental OV; significantly increased tumour CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration compared to untreated; RNA-seq analysis demonstrated significant enrichment in anti-viral, IFN and antigen presentation and processing pathways compared to untreated | [76] |

| HSV-1 | PD-1 human | scFV | GBM | Orthoptic GBM synergic mouse tumour model with intratumoural OV injection: increased median survival time compared to untreated (significant) and parental OV (not significant); successful tumour rejection following rechallenge | [87] |

| HSV-2 | PD-1 human | IgG | Melanoma | Subcutaneous mouse xenograft tumour model with intratumoural OV injection in humanised PD-1 transgenic mice: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to untreated; improved tumour-free survival compared to parental OV and untreated; successful tumour rejection following rechallenge; increased systemic percentages of CD4+, CD8+ and CD3+ T cells and significant increase in T cell activation markers compared to parental OV and untreated; significant reduction in Tregs and MDSCs compared to untreated | [77] |

| VV | PD-1 mouse | IgG & scFV | Fibrosarcoma Melanoma |

Subcutaneous synergic mouse tumour model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth, and prolonged survival (IgG significant; scFV not significant) compared to parental OV and untreated; IgG-OV significantly increased tumour infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the proportion of activated CD8+ T cells, and the CD8+/Foxp3+ T cell ratio compared to systemic anti-PD-L1 treatment, but to a lesser extent than parental OV alone | [84] |

| NDV | PD-1 and PD-L1 mouse & IL-2 | scFV | Melanoma | Unilateral subcutaneous synergic mouse tumour model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to parental OV Bilateral subcutaneous synergic mouse tumour model with single-sided intratumoural OV injection: when combined with systemic anti-CTLA-4 treatment, PD-1 and PD-L1 OV demonstrated significantly prolonged survival and inhibited tumour growth in non-injected tumours compared to parental OV |

[85] |

| MV | PD-1 & PD-L1 mouse | scFV-IgG1 Fc fusion | Melanoma | Subcutaneous synergic mouse tumour model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to parental OV and untreated; successful tumour rejection following rechallenge; significantly increased activated CD8+ T cell and reduced Foxp3+ Treg tumour infiltration; higher effector memory T cell: central memory T cell ratio for PD-1 (significant) and PD-L1 (not significant) OVs compared to untreated | [82,89] |

| Ad5/24 | PD-L1 mouse |

scFV | Colorectal | Bilateral subcutaneous synergic mouse tumour model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to parental OV and untreated; significantly increased tumour CD8+ T cell infiltration compared to parental OV | [86] |

| Chimeric poxvirus | PD-L1 human | scFv | Breast cancer Gastric cancer PDAC |

Orthotopic synergic mouse breast cancer model with intratumoural or intravenous OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to untreated Orthotopic mouse breast cancer xenograft model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to untreated Peritoneal mouse GC and PDAC xenograft tumour model with intraperitoneal OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to untreated |

[78–80,88] |

| VSV | PD-L1 human | scFV | Lung carcinoma | Subcutaneous mouse hPD-L1 knock-in synergic tumour model with intratumoural OV injection: significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival compared to untreated; successful tumour rejection following rechallenge; significant systemic increase in total number of CD8+ effector memory and CD8/CD4+ central memory T cells | [81] |

| VV | PD-L1 & GM-CSF human | Soluble PD-1 ED fused to IgG1 Fc | Melanoma | Bilateral subcutaneous synergic mouse tumour models with intratumoural OV injection: decreased tumour growth in 3 solid tumour models; significantly decreased tumour growth and prolonged survival upon tumour rechallenge compared to untreated and parental OV; significantly increased CD45+, DC, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell, and decreased MDSC and Treg tumour infiltration in injected tumours; untreated distant tumours also demonstrated increased infiltration and activation of lymphocytes and other immune cells | [90] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).