Submitted:

26 July 2023

Posted:

27 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of a Pathogenicity-Attenuated Mutant in S. sclerotiorum through Forward Genetic Screening

2.2. Sscle_11g085070 Is the Candidate mutated Gene of M14-9

2.3. SsCak1 Deletion Impairs Mycelial Growth and Sclerotia Development

2.4. Knockout of SsCak1 Results in Complete Loss of pathogenicity in S. sclerotiorum

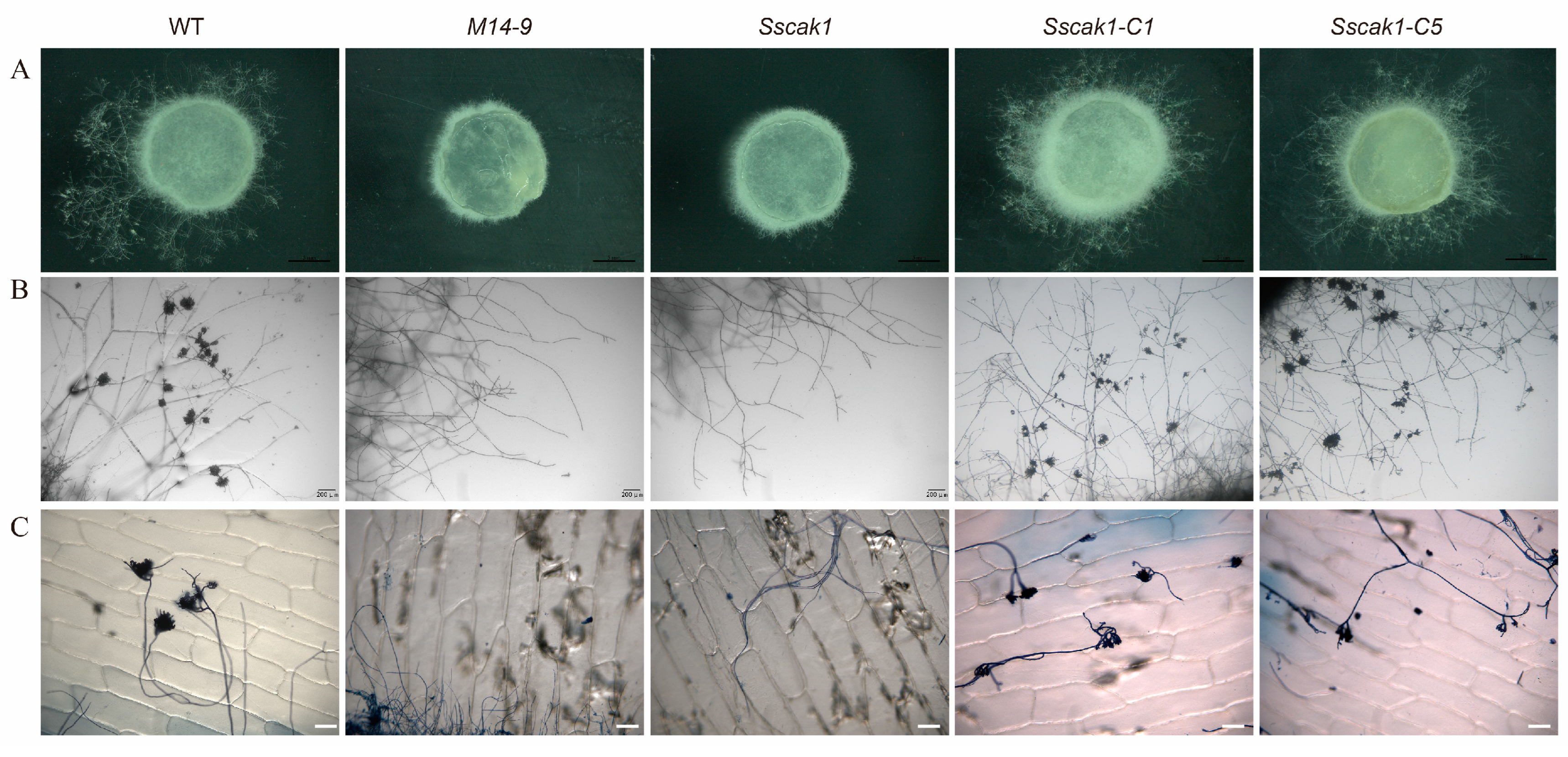

2.5. SsCak1 is essential for appressorium formation and penetration

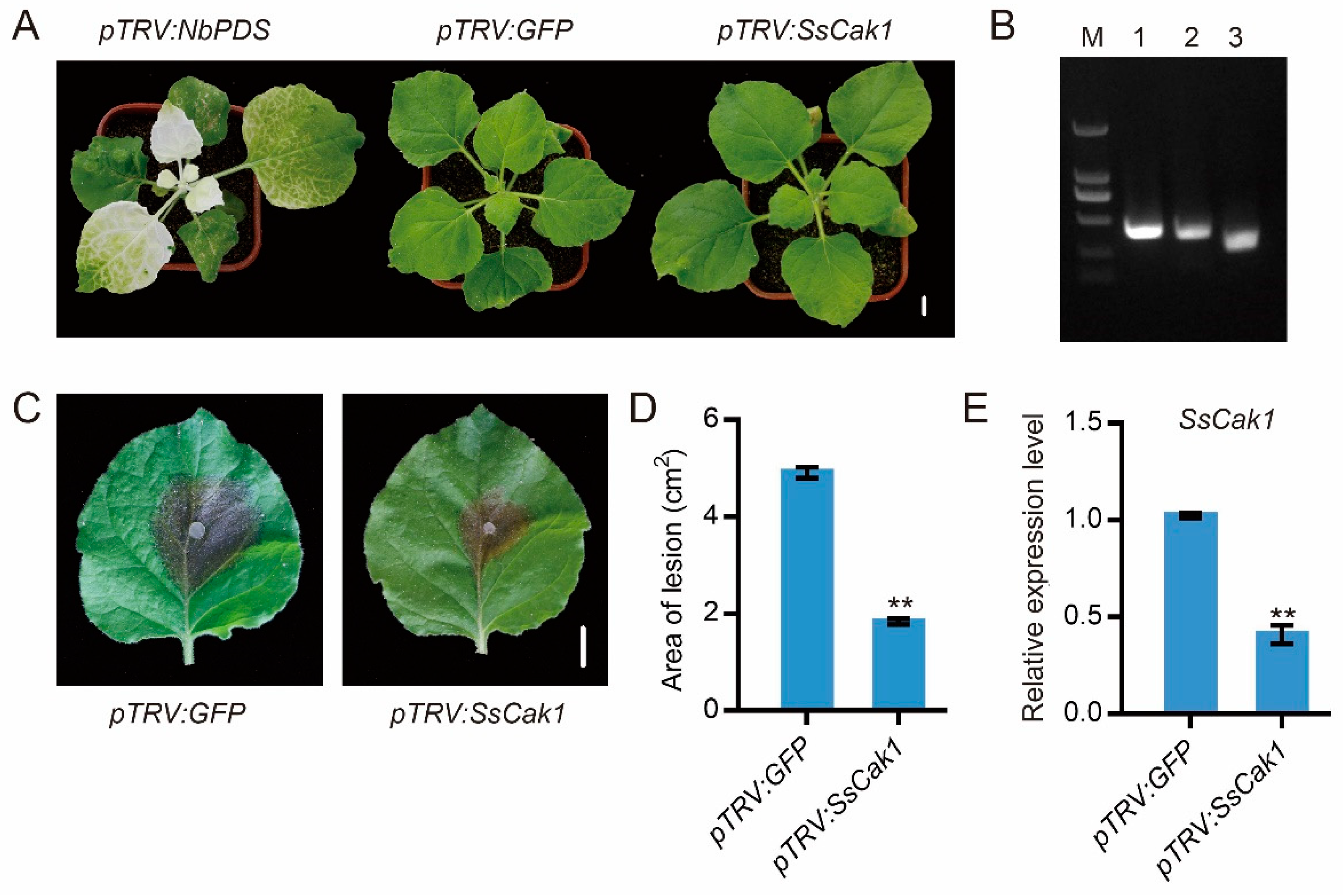

2.6. HIGS of SsCak1 in N. benthamiana Enhances Resistance to S. sclerotiorum

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fungal Strains, Plants and Culture Conditions

4.2. Inoculation and Virulence Assessment

4.3. Screening for mutants defective in virulence

4.4. Genomic DNA Extraction and NGS

4.5. Candidate Genes Identification

4.6. Target Gene Knockout and Transgene Complementation

4.7. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

4.8. RT-qPCR

4.9. Compound Appressoria Observation

4.10. Construction of TRV-HIGS Vectors and Agro-infiltration in N. benthamiana

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boland, G.J.; Hall, R. Index of plant hosts of sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Canadian journal of plant pathology 1994, 2, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, M.D.; Thomma, B.P.; Nelson, B.D. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: Biology and molecular traits of a cosmopolitan pathogen. Molecular plant pathology 2006, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Rollins, J.A. Mechanisms of broad host range necrotrophic pathogenesis in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, J.A.; Dickman, M.B. pH signaling in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: Identification of a pacC/RIM1 homolog. Applied and environmental microbiology 2001, 67, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifbarghi, S.; Borhan, M.H.; Wei, Y.; Coutu, C.; Robinson, S.J.; Hegedus, D.D. Changes in the Sclerotinia sclerotiorum transcriptome during infection of Brassica napus. BMC genomics 2017, 18, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yan, B.; Liao, H.; Dong, M.; Meng, X.; Wan, H.; Qian, W. Host-induced gene silencing of a multifunction gene Sscnd1 enhances plant resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Frontiers in microbiology 2021, 12, 693334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Kabbage, M.; Kim, H.J.; Britt, R.; Dickman, M.B. Tipping the balance: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum secreted oxalic acid suppresses host defenses by manipulating the host redox environment. PLoS pathogens 2011, 7, e1002107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittem, K.; Yajima, W.R.; Goswami, R.S.; Del Río Mendoza, L.E. Transcriptome analysis of the plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum interaction with resistant and susceptible canola (Brassica napus) lines. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Buchenauer, H.; Han, Q.; Zhang, X.; Kang, Z. Ultrastructural and cytochemical studies on the infection process of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in oilseed rape. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection 2008, 115, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, V.N.; Jeffries, P. Ultrastructure of penetration of Phaseolus spp. by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Canadian Journal of Botany 1986, 64, 2909–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, H.; Li, H.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Kuo, J.; Barbetti, M.J. The infection processes of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in cotyledon tissue of a resistant and a susceptible genotype of Brassica napus. Annals of botany 2010, 106, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andradeab, C.M.; Tinocoa, M.L.P.; Rietha, A.F.; Maiaa, F.C.O.; Araga~Oa, F.J.L. Host-induced gene silencing in the necrotrophic fungal pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Pathology 2016, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Yuan, J.; Liao, H.; Banga, S.S.; Kumar, R.; Qian, W.; Ding, Y. Host-induced gene silencing reveals the role of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase gene in fungal oxalic acid accumulation and virulence. Microbiol Res. 2022, 258, 126981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wytinck, N.; Ziegler, D.J.; Walker, P.L.; Sullivan, D.S.; Biggar, K.T.; Khan, D.; Sakariyahu, S.K.; Wilkins, O.; Whyard, S.; Belmonte, M.F. Host induced gene silencing of the Sclerotinia sclerotiorum ABHYDROLASE-3 gene reduces disease severity in Brassica napus. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Ding, Y.; Banga, S.S.; Liao, H.; Zhao, S.; Yu, Y.; Qian, W. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Thioredoxin1 (SsTrx1) is required for pathogenicity and oxidative stress tolerance. Molecular plant pathology 2021, 22, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. A cAMP phosphodiesterase is essential for sclerotia formation and virulence in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1175552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, T.; Josh, L.; Yan, X.; Yilan, Q.; Xin, L. A MAP kinase cascade broadly regulates development and virulence of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and can be targeted by HIGS for disease control. bioRxiv 2003, 2023.2003.2001.530680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ao, K.; Tian, L.; Qiu, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, X.; Hoy, R.; Zhang, Y.; Rashid, K.Y.; Xia, S.; et al. A forward genetic screen in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum revealed the transcriptional regulation of its sclerotial melanization Pathway. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI 2022, 35, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Sun, Y.; Orduna, A.R.; Jetter, R.; Li, X. The Mediator kinase module serves as a positive regulator of salicylic acid accumulation and systemic acquired resistance. The Plant journal 2019, 98, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Ma, J.; Dai, Y.; Li, C.; Lyu, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, J.R. Two Cdc2 Kinase Genes with distinct functions in vegetative and infectious hyphae in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS pathogens 2015, 11, e1004913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cai, G.; Tu, J.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Luo, X.; Zhou, L.; Fan, C.; Zhou, Y. Identification of QTLs for resistance to sclerotinia stem rot and BnaC.IGMT5.a as a candidate gene of the major resistant QTL SRC6 in Brassica napus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, S.K.; Hunter, T. Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: Kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB journal 1995, 9, 576–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, G.; Plowman, G.D.; Hunter, T.; Sudarsanam, S. Evolution of protein kinase signaling from yeast to man. Trends in biochemical sciences 2002, 27, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda-Saavedra, D.; Barton, G.J. Classification and functional annotation of eukaryotic protein kinases. Proteins 2007, 68, 893–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Harel, A.; Gorovoits, R.; Yarden, O.; Dickman, M.B. MAPK regulation of sclerotial development in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is linked with pH and cAMP sensing. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI 2004, 17, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashi, Z.D.; Gyawali, S.; Bekkaoui, D.; Coutu, C.; Lee, L.; Poon, J.; Rimmer, S.R.; Khachatourians, G.G.; Hegedus, D.D. The Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Slt2 mitogen-activated protein kinase ortholog, SMK3, is required for infection initiation but not lesion expansion. Canadian journal of microbiology 2016, 62, 836–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Kipreos, E.T. Evolution of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and CDK-activating kinases (CAKs): Differential conservation of CAKs in yeast and metazoa. Mol Biol Evol 2000, 17, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.O. Cyclin-dependent kinases: Engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1997, 13, 261–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, F.H.; Farrell, A.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Morgan, D.O. (1996). A cyclin-dependent kinase-activating kinase (CAK) in budding yeast unrelated to vertebrate CAK. Science 1997, 273, 1714–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, J.E.; Fisher, R.P. A CDK-activating kinase network is required in cell cycle control and transcription in fission yeast. Curr Biol 2000, 12, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.W. The Function of Cell Division Cycle Protein SsCdc28 in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Master, Jilin University, Jilin, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castanheira, S.; Pérez-Martín, J. Appressorium formation in the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis requires a G2 cell cycle arrest. Plant signaling & behavior 2015, 10, e1001227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osés-Ruiz, M.; Talbot, N.J. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of plant infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Communicative & integrative biology 2017, 10, e1372067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, A.; Castanheira, S.; Pérez-Martín, J. Incompatibility between proliferation and plant invasion is mediated by a regulator of appressorium formation in the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117, 30599–30609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Cao, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.R.; Wang, C. MoCDC14 is important for septation during conidiation and appressorium formation in Magnaporthe oryzae. Molecular plant pathology 2018, 19, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science (New York, NY) 2018, 360, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowara, D.; Schweizer, P.; Gay, A.; Lacomme, C.; Shaw, J.; Ridout, C.; et al. HIGS: Host-induced gene silencing in the obligate biotrophic fungal pathogen Blumeria graminis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 3130–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, J.H.; Gao, F.; Zhou, B.J.; Fang, Y.Y.; et al. (2016). Host-induced gene silencing of the target gene in fungal cells confers effective resistance to the cotton wilt disease pathogen Verticillium dahliae. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 939–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, M.; Pugliesi, C.; Fambrini, M.; Pecchia, S. (2021). Silencing of the Slt2-type MAP kinase Bmp3 in Botrytis cinerea by application of exogenous dsRNA affects fungal growth and virulence on Lactuca sativa. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2021, 22, 5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, J.G.; Duan, J.J. RNAi-based insecticidal crops: Potential effects on nontarget species. Bioscience 2013, 63, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, W.; Huang, X.; Tang, X.; Qin, L.; Liu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Peng, Z.; Xia, S. SsNEP2 contributes to the virulence of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D.; Wittkop, B.; Ding, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Wan, H.; Li, Z.; Ge, X.; et al. Transfer of sclerotinia resistance from wild relative of Brassica oleracea into Brassica napus using a hexaploidy step. Theor Appl Genet 2015, 128, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, C.; Wan, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Yamamoto, N.; Zhou, E.; Shu, C. Functional validation of pathogenicity genes in rice sheath blight pathogen Rhizoctonia solani by a novel host-induced gene silencing system. Molecular plant pathology 2021, 22, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, G.C.; Flores-Vergara, M.A.; Krasynanski, S.; Kumar, S.; Thompson, W.F. A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nature protocols 2006, 1, 2320–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; Del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Current protocols in bioinformatics 2013, 43, 11.10.11–11.10.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catlett, N.L.; Lee, B.N.; Yoder, O.C.; Turgeon, B.G. Split-marker recombination for efficient targeted deletion of fungal genes. Fungal Genetics Newsletter 2003, 50, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, H. The Sclerotinia sclerotiorum FoxE2 gene is required for apothecial development. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthil-Kumar, M.; Mysore, K.S. Tobacco rattle virus-based virus-induced gene silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. Nat Protoc 2014, 9, 1549–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, E.; Page, J.E. Optimized cDNA libraries for virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) using tobacco rattle virus. Plant Methods 2008, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).