Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

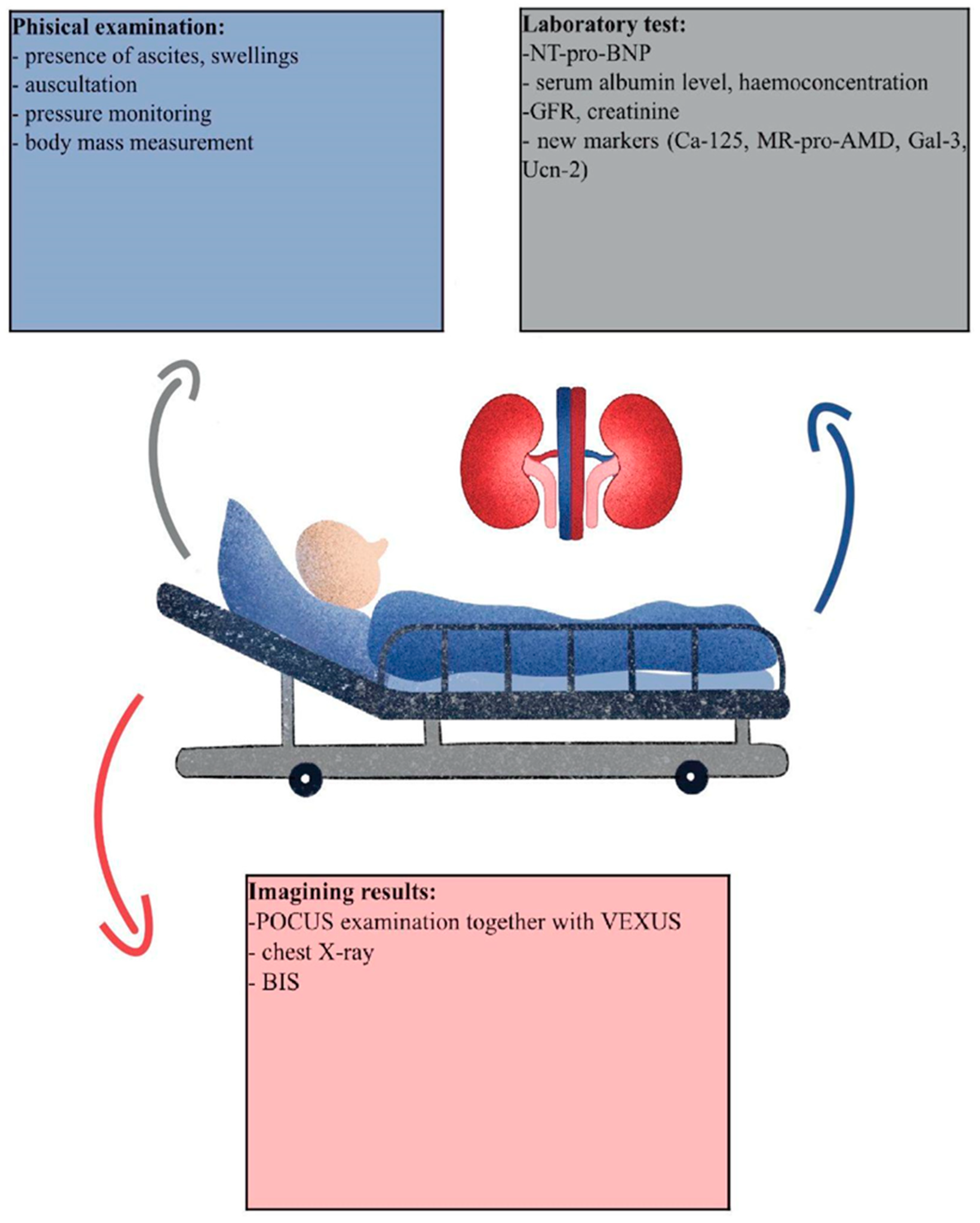

3.1. Available markers

3.2. Gold standard: Bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS)

3.3. Serum markers

3.3.1. NT-pro-BNP

3.3.2. Ca-125

3.3.3. Adrenomedullin and proadrenomedullin

3.3.4. Galectin-3

3.3.5. Urocortin-2

3.3.6. Imaging studies

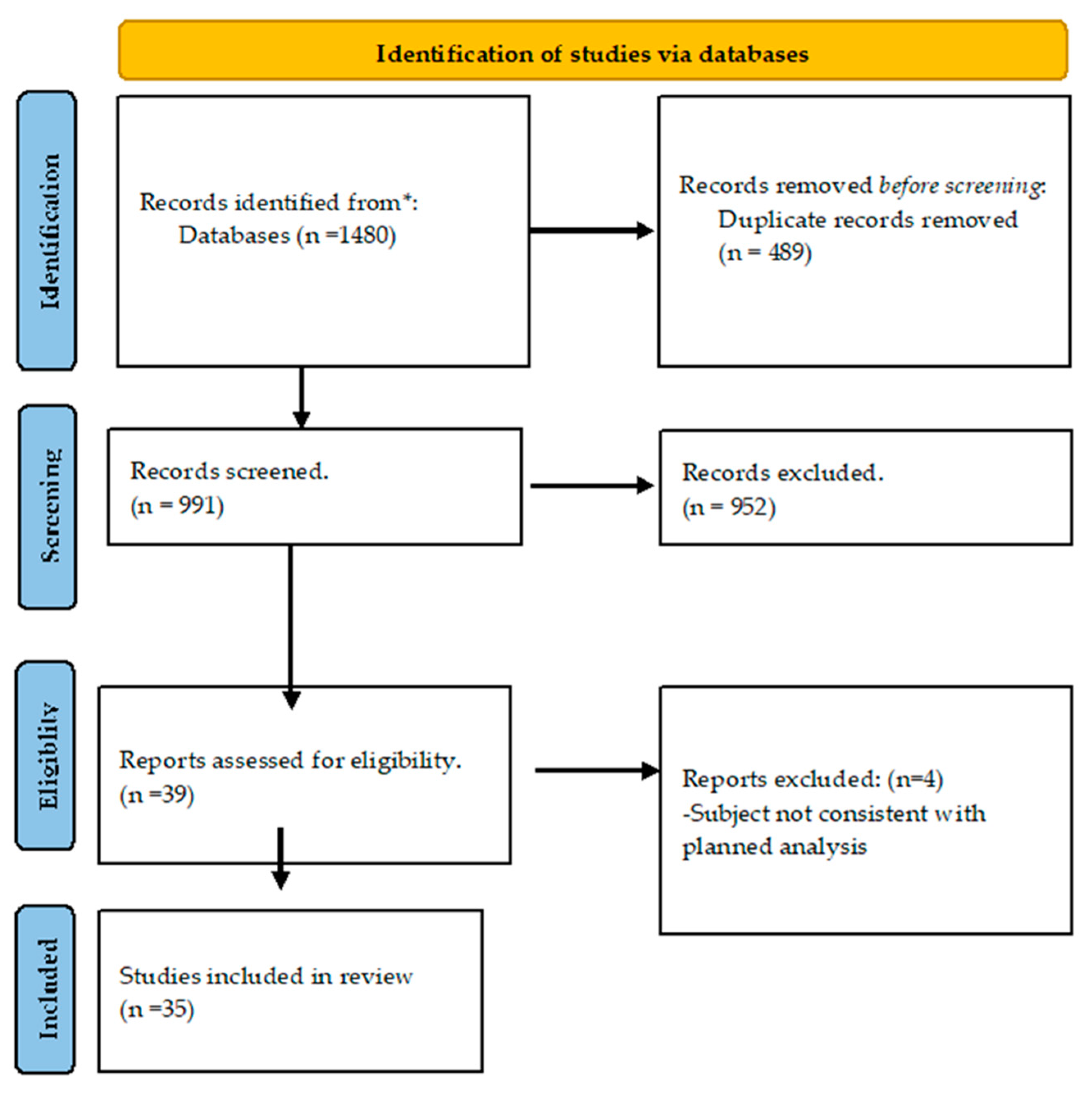

4. Materials and methods

5. Conclusion and results

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADM | adrenomedullin |

| AKI | acute kidney injury |

| BCM | Body Composition Monitor |

| BIS | Bioimpendance spectroscopy |

| Ca-125 | Carbohydrate antigen 125 |

| CKD | chronic kidney disease |

| CPK | congenital polycystic kidney |

| CT | computer tomography |

| ECW | internal cell water |

| eGFR | estimated GFR |

| ESRD | end stage renal disease |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FFM | fat free mass |

| GFR | glomerular filtration rate |

| HD | haemodialysis |

| HF | heart failure |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| ICW | internal cell water |

| IVC | inferior vena cava |

| MAP | mean arterial pressure |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imagining |

| MR-pro-AMD | Mid-regional AMD |

| MR-pro-AMP | Pro-atrial Natriuretic Peptide |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| OH | overhydration |

| PAH | pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| POCUS | point of care ultrasonography |

| Pro-ADM | proadrenomedullin |

| TBW | total body water |

| USG | ultrasonography |

| VEXUS | Venous Excess Ultrasound Score |

References

- Ohashi, Y.; Sakai, K.; Hase, H.; Joki, N. Dry weight targeting: The art and science of conventional hemodialysis. Semin. Dial. 2018, 31, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccali, C.; Moissl, U.; Chazot, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Tripepi, G.; Arkossy, O.; Wabel, P.; Stuard, S. Chronic Fluid Overload and Mortality in ESRD. 2017.

- Wang, Y.; Gu, Z. Effect of bioimpedance-defined overhydration parameters on mortality and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, S.C.; Kuo, K.L.; Peng, C.H.; Wu, C.H.; Lien, Y.C.; Wang, Y.C.; Tarng, D.C. Volume overload correlates with cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2014, 85, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati, P.A.; Guevara, J.M.; Ardiles, V.; Guillemi, E.C.; Londoño, L.; Dubin, A. Caudal vena cava collapsibility index as a tool to predict fluid responsiveness in dogs. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2020, 30, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B. Fluid Overload. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Bouchard, J.; Desjardins, G.; Lamarche, Y.; Liszkowski, M.; Robillard, P.; Denault, A. Extracardiac Signs of Fluid Overload in the Critically Ill Cardiac Patient: A Focused Evaluation Using Bedside Ultrasound. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutradis, C.; Papadopoulos, C.E.; Sachpekidis, V.; Ekart, R.; Krunic, B.; Karpetas, A.; Bikos, A.; Tsouchnikas, I.; Mitsopoulos, E.; Papagianni, A.; et al. Lung Ultrasound–Guided Dry Weight Assessment and Echocardiographic Measures in Hypertensive Hemodialysis Patients: A Randomized Controlled Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Andersen, M.J.; Pratt, J.H. On the importance of pedal edema in hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaga; Aguilar; Ruíz-Tovar; Calpena; García; Durán Hydration status according to impedance vectors and its association with clinical and biochemical outcomes and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nutr Hosp 2016, 33, 832–837.

- Koratala, A.; Ronco, C.; Kazory, A. The Promising Role of Lung Ultrasound in Assessment of Volume Status for Patients Receiving Maintenance Renal Replacement Therapy. Blood Purif. 2020, 49, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.; Abad, S.; Macías, N.; Aragoncillo, I.; García-Prieto, A.; Linares, T.; Torres, E.; Hernández, A.; Luño, J. Any grade of relative overhydration is associated with long-term mortality in patients with Stages 4 and 5 non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2018, 11, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Pang, W.F.; Jin, L.; Li, H.; Chow, K.M.; Kwan, B.C.H.; Leung, C.B.; Li, P.K.T.; Szeto, C.C. Peritoneal protein clearance predicts mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2019, 23, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chazot, C.; Wabel, P.; Chamney, P.; Moissl, U.; Wieskotten, S.; Wizemann, V.; Le, S.F. Original Articles Importance of normohydration for the long-term survival of haemodialysis patients. 2012, 2404–2410. [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Iguacel, C.; González-Parra, E.; Mahillo, I.; Ortiz, A. Low intracellular water, overhydration, and mortality in hemodialysis patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siriopol, D.; Onofriescu, M.; Voroneanu, L.; Apetrii, M.; Nistor, I.; Hogas, S.; Kanbay, M.; Sascau, R.; Scripcariu, D.; Covic, A. Dry weight assessment by combined ultrasound and bioimpedance monitoring in low cardiovascular risk hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, S.C.; Lai, Y.S.; Kuo, K.L.; Tarng, D.C. Volume overload and adverse outcomes in chronic kidney disease: clinical observational and animal studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koratala, A.; Ronco, C.; Kazory, A. Diagnosis of Fluid Overload: from Conventional to Contemporary Concepts. Cardiorenal Med. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, M.J.E.; Kooman, J.P. Fluid status assessment in hemodialysis patients and the association with outcome: Review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2018, 27, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofriescu, M.; Siriopol, D.; Voroneanu, L.; Hogas, S.; Nistor, I.; Apetrii, M.; Florea, L.; Veisa, G.; Mititiuc, I.; Kanbay, M.; et al. Overhydration, cardiac function and survival in hemodialysis patients. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krediet, R.T.; Smit, W.; Coester, A.M.; Struijk, D.G. Dry body weight and ultrafiltration targets in peritoneal dialysis. Contrib. Nephrol. 2009, 163, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgos, S.; Hartmann, A.; Bollerslev, J.; Vörös, P.; Rosivall, L. The importance of body composition and dry weight assessments in patients with chronic kidney disease (Review). Acta Physiol. Hung. 2011, 98, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earthman, C.; Traughber, D.; Dobratz, J.; Howell, W. Bioimpedance spectroscopy for clinical assessment of fluid distribution and Body cell mass. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2007, 22, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Rola, P.; Haycock, K.; Bouchard, J.; Lamarche, Y.; Spiegel, R.; Denault, A.Y. Quantifying systemic congestion with Point-Of-Care ultrasound: development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system. Ultrasound J. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schork, A.; Bohnert, B.N.; Heyne, N.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Artunc, F. Overhydration Measured by Bioimpedance Spectroscopy and Urinary Serine Protease Activity Are Risk Factors for Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2020, 45, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, H.; Gürel, O.M.; Çelik, H.T.; Şahiner, E.; Yildirim, M.E.; Bilgiç, M.A.; Bavbek, N.; Akcay, A. CA 125 levels and left ventricular function in patients with end-stage renal disease on maintenance hemodialysis. Ren. Fail. 2014, 36, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijayaratne, D.; Muthuppalaniappan, V.M.; Davenport, A. Serum CA125 a potential marker of volume status for peritoneal dialysis patients? Int. J. Artif. Organs 2021, 44, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, A.M.; Marques, R.; Domingos, A.T.; Silva, A.P.; Bernardo, I.; Neves, P.L.; Rodrigues, A.; Krediet, R.T. Overhydration May Be the Missing Link between Peritoneal Protein Clearance and Mortality. Nephron 2021, 145, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Marín, G.; de la Espriella, R.; Santas, E.; Lorenzo, M.; Miñana, G.; Núñez, E.; Bodí, V.; González, M.; Górriz, J.L.; Bonanad, C.; et al. CA125 but not NT-proBNP predicts the presence of a congestive intrarenal venous flow in patients with acute heart failure. Eur. Hear. Journal. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2021, 10, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Benkreira, A.; Robillard, P.; Bouabdallaoui, N.; Chassé, M.; Desjardins, G.; Lamarche, Y.; White, M.; Bouchard, J.; Denault, A. Alterations in portal vein flow and intrarenal venous flow are associated with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: A prospective observational cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argaiz, E.R.; Rola, P.; Gamba, G. Dynamic Changes in Portal Vein Flow during Decongestion in Patients with Heart Failure and Cardio-Renal Syndrome: A POCUS Case Series. CardioRenal Med. 2021, 11, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornejo-Pareja, I.; Vegas-Aguilar, I.M.; Lukaski, H.; Talluri, A.; Bellido-Guerrero, D.; Tinahones, F.J.; García-Almeida, J.M. Overhydration Assessed Using Bioelectrical Impedance Vector Analysis Adversely Affects 90-Day Clinical Outcome among SARS-CoV2 Patients: A New Approach. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacHek, P.; Jirka, T.; Moissl, U.; Chamney, P.; Wabel, P. Guided optimization of fluid status in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Choi, G.H.; Shim, K.E.; Lee, J.H.; Heo, N.J.; Joo, K.W.; Yoon, J.W.; Oh, Y.K. Changes in bioimpedance analysis components before and after hemodialysis. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 37, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covic, A.; Ciumanghel, A.I.; Siriopol, D.; Kanbay, M.; Dumea, R.; Gavrilovici, C.; Nistor, I. Value of bioimpedance analysis estimated “dry weight” in maintenance dialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 2231–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, W.Y.; Park, S.; Kim, Y.W.; Jin, K. Clinical efficacy of biomarkers for evaluation of volume status in dialysis patients. Med. (United States) 2020, 99, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.Y.M.; Lam, C.W.K.; Yu, C.M.; Wang, M.; Chan, I.H.S.; Zhang, Y.; Lui, S.F.; Sanderson, J.E. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide: An independent risk predictor of cardiovascular congestion, mortality, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koratala, A.; Kazory, A. Natriuretic Peptides as Biomarkers for Congestive States: The Cardiorenal Divergence. Dis. Markers 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, G. Pathophysiology of cardiovascular damage in the early renal population. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2001, 16, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astor, B.C.; Yi, S.; Hiremath, L.; Corbin, T.; Pogue, V.; Wilkening, B.; Peterson, G.; Lewis, J.; Lash, J.P.; Van Lente, F.; et al. N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide as a predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality in blacks with hypertensive kidney disease: The African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK). Circulation 2008, 117, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, T.; Takase, H.; Toriyama, T.; Sugiura, T.; Kurita, Y.; Tsuru, N.; Masuda, H.; Hayashi, K.; Ueda, R.; Dohi, Y. Increased circulating levels of natriuretic peptides predict future cardiac event in patients with chronic hemodialysis. Nephron 2002, 92, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Luo, L.; Ye, P.; Yi, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Wang, L.; Xiao, T.; Bai, Y. The ability of NT-proBNP to detect chronic heart failure and predict all-cause mortality is higher in elderly Chinese coronary artery disease patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LA, O.; A, S.; JS, B. Amino-terminal Pro B-Type Natriuretic Peptide for Diagnosis and Prognosis in Patients with Renal Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 176, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwaruddin, S.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Baggish, A.; Chen, A.; Krauser, D.; Tung, R.; Chae, C.; Januzzi, J.L. Renal function, congestive heart failure, and amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide measurement: Results from the ProBNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFilippi, C.R.; Seliger, S.L.; Maynard, S.; Christenson, R.H. Impact of renal disease on natriuretic peptide testing for diagnosing decompensated heart failure and predicting mortality. Clin. Chem. 2007, 53, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pousset, F.; Masson, F.; Chavirovskaia, O.; Isnard, R.; Carayon, A.; Golmard, J.L.; Lechat, P.; Thomas, D.; Komajda, M. Plasma adrenomedullin, a new independent predictor of prognosis in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2000, 21, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voors, A.A.; Kremer, D.; Geven, C.; ter Maaten, J.M.; Struck, J.; Bergmann, A.; Pickkers, P.; Metra, M.; Mebazaa, A.; Düngen, H.D.; et al. Adrenomedullin in heart failure: pathophysiology and therapeutic application. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, T.; Kuriyama, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Saito, S.; Tanaka, R.; Iwao, M.; Tanaka, M.; Maki, T.; Itoh, H.; Ihara, M.; et al. Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin is a novel biomarker for arterial stiffness as the criterion for vascular failure in a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikimi, T.; Nakagawa, Y. Adrenomedullin as a Biomarker of Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2018, 14, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ-Crain, M.; Morgenthaler, N.G.; Struck, J.; Harbarth, S.; Bergmann, A.; Müller, B. Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin as a prognostic marker in sepsis: an observational study. Crit. Care 2005, 9, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigué, B.; Leblanc, P.E.; Moati, F.; Pussard, E.; Foufa, H.; Rodrigues, A.; Figueiredo, S.; Harrois, A.; Mazoit, J.X.; Rafi, H.; et al. Mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin (MR-proADM), a marker of positive fluid balance in critically ill patients: Results of the ENVOL study. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouya, G.; Sturm, G.; Lamina, C.; Zitt, E.; Freistätter, O.; Struck, J.; Wolzt, M.; Knoll, F.; Lins, F.; Lhotta, K.; et al. The association of mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin and mid-regional pro-atrial natriuretic peptide with mortality in an incident dialysis cohort. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutin, L.; Dépret, F.; Gayat, E.; Legrand, M.; Chadjichristos, C.E. Galectin-3 in Kidney Diseases: From an Old Protein to a New Therapeutic Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Meng, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Cao, M.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y. Hypoxia contributes to galectin-3 expression in renal carcinoma cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 890, 173637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Jiang, H.; Eliaz, A.; Kellum, J.A.; Peng, Z.; Eliaz, I. Galectin-3 in septic acute kidney injury: a translational study. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkurt, S.; Dogan, I.; Ozcan, O.; Fidan, N.; Bozaci, I.; Yilmaz, B.; Bilgin, M. Correlation of serum galectin-3 level with renal volume and function in adult polycystic kidney disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.M.; Tsai, M.T.; Chen, H.Y.; Li, F.A.; Tseng, W.C.; Lee, K.H.; Chang, F.P.; Lin, Y.P.; Yang, R.B.; Tarng, D.C. Identification of Galectin-3 as Potential Biomarkers for Renal Fibrosis by RNA-Sequencing and Clinicopathologic Findings of Kidney Biopsy. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.M.; Tsai, M.T.; Chen, H.Y.; Li, F.A.; Lee, K.H.; Tseng, W.C.; Chang, F.P.; Lin, Y.P.; Yang, R.B.; Tarng, D.C. Urinary Galectin-3 as a Novel Biomarker for the Prediction of Renal Fibrosis and Kidney Disease Progression. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Shen, Y.; Lin, C.; Qin, L.; He, S.; Dai, M.; Okitsu, S.L.; DeMartino, J.A.; Guo, Q.; Shen, N. Urinary galectin-3 binding protein (G3BP) as a biomarker for disease activity and renal pathology characteristics in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2022, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Zhang, P.; Zeng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, L.; Chen, B. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate renal fibrosis by galectin-3/Akt/GSK3β/Snail signaling pathway in adenine-induced nephropathy rat. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Yang, S.; Li, J.C.; Feng, J.X. Galectin 3 inhibition attenuates renal injury progression in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravaca Perez, P.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Nuche, J.; Matute-Blanco, L.; Serrano, I.; Martínez Selles, M.; Vázquez García, R.; Martínez Dolz, L.; Gómez-Bueno, M.; Pascual Figal, D.; et al. Renal Function Impact in the Prognostic Value of Galectin-3 in Acute Heart Failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, A.; Ibrahim, M.; El Fallah, A.A.; Elian, M.; Deraz, S.E. Galectin-3 as an early marker of diastolic dysfunction in children with end-stage renal disease on regular hemodialysis. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2022, 15, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rademaker, M.T.; Charles, C.J.; Ellmers, L.J.; Lewis, L.K.; Nicholls, M.G.; Richards, A.M. Prolonged urocortin 2 administration in experimental heart failure: Sustained hemodynamic, endocrine, and renal effects. Hypertension 2011, 57, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintalhao, M.; Maia-Rocha, C.; Castro-Chaves, P.; Adão, R.; Barros, A.S.; Clara Martins, R.; Leite-Moreira, A.; Bettencourt, P.; Bras-Silva, C. Urocortin-2 in Acute Heart Failure: Role as a Marker of Volume Overload and Pulmonary Hypertension. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2022, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rademaker, M.T.; Charles, C.J.; Nicholls, G.; Richards, M. Urocortin 2 sustains haemodynamic and renal function during introduction of beta-blockade in experimental heart failure. J. Hypertens. 2011, 29, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Frishman, W.H. A New Potential Approach to Inotropic Therapy in the Treatment of Heart Failure: Urocortin. Cardiol. Rev. 2013, 21, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, E.; Monge, L.; Fernández, N.; Climent, B.; Diéguez, G.; Garcia-Villalón, A.L. Mechanisms of relaxation by urocortin in renal arteries from male and female rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 140, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.E.; Pemberton, C.J.; Yandle, T.G.; Fisher, S.F.; Lainchbury, J.G.; Frampton, C.M.; Rademaker, M.T.; Richards, A.M. Urocortin 2 Infusion in Healthy Humans. Hemodynamic, Neurohormonal, and Renal Responses. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adão, R.; Mendes-Ferreira, P.; Santos-Ribeiro, D.; Maia-Rocha, C.; Pimentel, L.D.; Monteiro-Pinto, C.; Mulvaney, E.P.; Reid, H.M.; Kinsella, B.T.; Potus, F.; et al. Urocortin-2 improves right ventricular function and attenuates pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, M.T.; Ellmers, L.J.; Charles, C.J.; Mark Richards, A. Urocortin 2 protects heart and kidney structure and function in an ovine model of acute decompensated heart failure: Comparison with dobutamine. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 197, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, M.T.; Charles, C.J.; Nicholls, M.G.; Richards, A.M. Urocortin 2 inhibits furosemide-induced activation of renin and enhances renal function and diuretic responsiveness in experimental heart failure. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2009, 2, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.S.A.; Collin, M.; Thiemermann, C. Urocortin does not reduce the renal injury and dysfunction caused by experimental ischaemia/reperfusion. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 496, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.Y.W.; Frampton, C.M.; Crozier, I.G.; Troughton, R.W.; Richards, A.M. Urocortin-2 infusion in acute decompensated heart failure: Findings from the UNICORN study (urocortin-2 in the treatment of acute heart failure as an adjunct over conventional therapy). JACC Hear. Fail. 2013, 1, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.; de la Espriella, R.; Miñana, G.; Santas, E.; Llácer, P.; Núñez, E.; Palau, P.; Bodí, V.; Chorro, F.J.; Sanchis, J.; et al. Antigen carbohydrate 125 as a biomarker in heart failure: a narrative review. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arik, N.; Adam, B.; Akpolat, T.; Haşil, K.; Tabak, S. Serum tumour markers in renal failure. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 1996, 28, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koratala, A.; Reisinger, N. POCUS for Nephrologists: Basic Principles and a General Approach. Kidney360 2021, 2, 1660–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexiadis, G.; Panagoutsos, S.; Roumeliotis, S.; Stibiris, I.; Markos, A.; Kantartzi, K.; Passadakis, P. Comparison of multiple fluid status assessment methods in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loutradis, C.; Sarafidis, P.A.; Ekart, R.; Papadopoulos, C.; Sachpekidis, V.; Alexandrou, M.E.; Papadopoulou, D.; Efstratiadis, G.; Papagianni, A.; London, G.; et al. The effect of dry-weight reduction guided by lung ultrasound on ambulatory blood pressure in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Tomar, D.S. Vexus—the third eye for the intensivist? Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 746–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Arjun D. Agarwal, Rajiv- Can Chronic Volume Overload Be Recognized and Prevented in Hemodialysis Patients? The Pitfalls of the Clinical Examination in Assessing Volume Status. Seminars in Dialysis. 2009, 22, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name of the test | Includes kidney function? | Includes water balance? | Clinical application | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS | No | Yes | Content of ICW and ECW | Not all clinical conditions |

| USG | No | Yes | IVC diameter, VEXUS protocol, IJV?. | Not all structures are always available during the test. Depends on doctors’ experience |

| NT-pro-BNP | No | No | Correlation with OH consequences like heart failure and inflammation process. | Neither kidney nor OH direct marker |

| Ca-125 | No | Yes | Cancer marker, research among the usage in HF and CKD | Novel approach, needs further research |

| ADM/ MR-pro-ADM | No | Yes | Marker of vasodilatation and vessel injury due to fluid overload | Does not correlate in all studies with other available markers, needs further investigation |

| Gal-3 | Yes | No | Marker of renal injury, inflammation and fibrogenesis | Does not correlate directly with OH, but with kidney function, needs further investigation |

| Ucn-2 | No | No | Increases heart dynamic properties, stimulates diuresis and sodium excretion | Needs further investigation as mixed results are obtained |

| Author | BIS | Creatinine | eGFR | NT-pro-BNP | Ca-125 | USG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schork et al.[25] | + | +* | + | + | N/M | N/M |

| Hung et al. [17] | + | +* | + | + | N/M | N/M |

| Yilmaz et al. [26] | N/M | N/M | N/M | + | + | + |

| Wijayaratne et al. [27] | + | - | N/M | + | + | N/M |

| Guedes et al. [28] | + | + | N/M | N/M | N/M | + |

| Núñez-Marín et al. [29] | N/M | N/M | N/M | - | + | + (vexus) |

| Beaubien-Souligny [24] | N/M | + | N/M | + | N/M | + |

| Beaubien-Souligny et al. [30] | N/M | + | + | + | N/M | + |

| Argaiz et al. [31] | N/M | + | N/M | + | N/M | + |

| Vega et al. [12] | + | + | N/M | + | N/M | N/M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).