1. Introduction

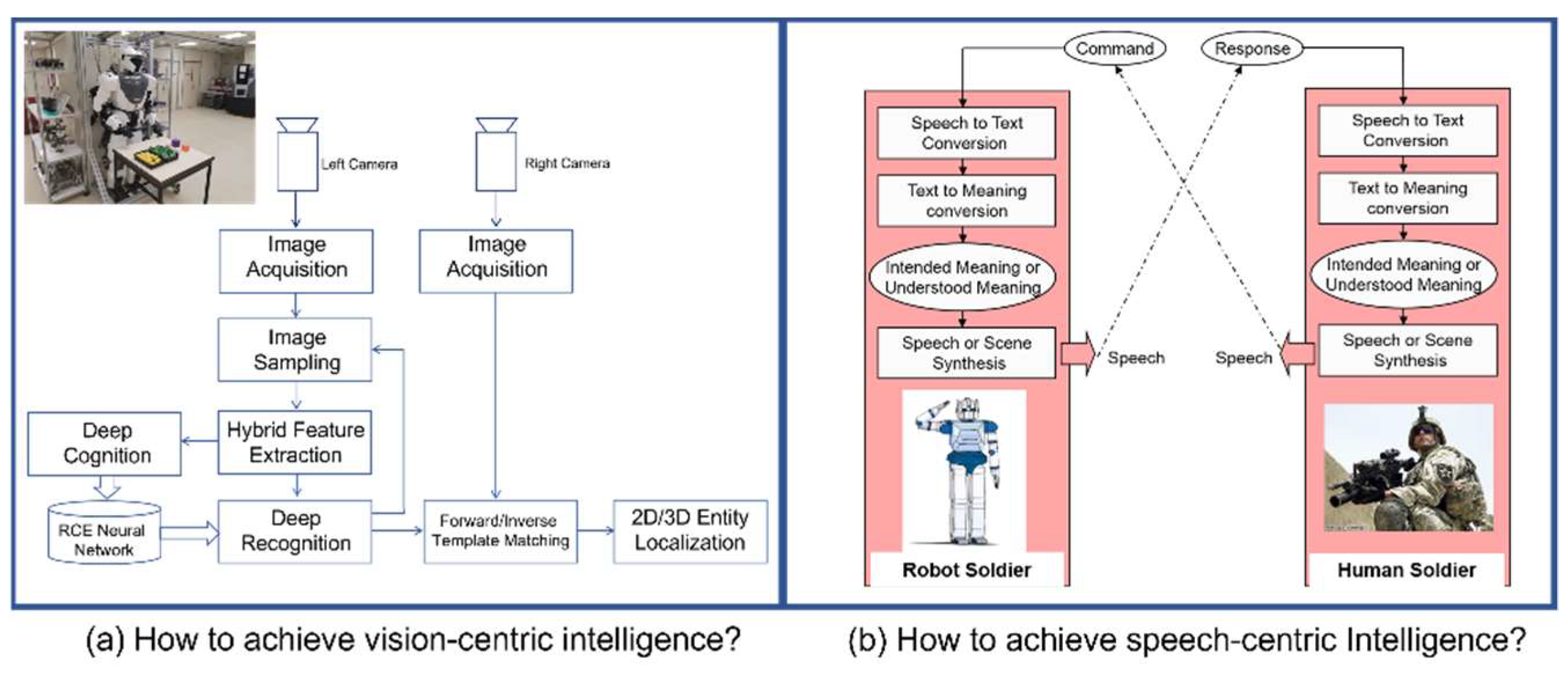

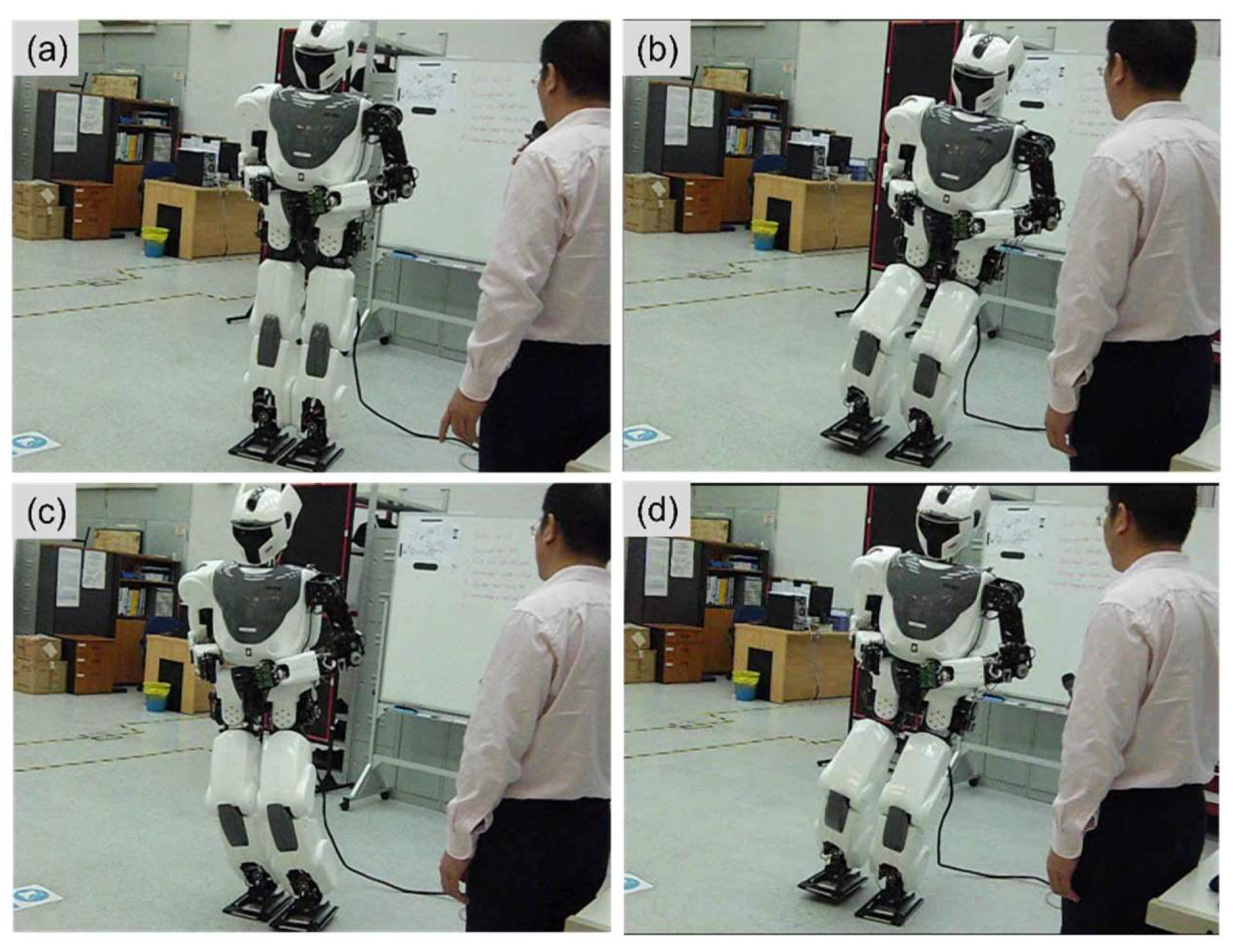

Our missions on Earth include the understanding of the world as well as the improvement of the world. These missions are only achievable by doing research and innovation. Today, we know that one of the last frontiers in science is the understanding of our brain and our mind, while one of the last challenges in engineering is the development (i.e., top-down design) of cognitive machines with human-like intelligence and skills. Interestingly, humanoid robotics seems to be the best field of R&D, which offers unique platforms for the design, integration, and testing of vision-centric intelligence as well as speech-centric intelligence [Tsagarakis et al (2007); Cheng (2014)].

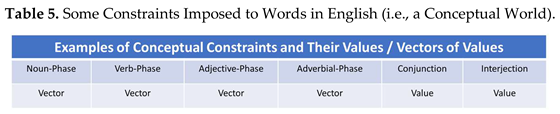

We, at Nanyang Technological University, have embarked on the R&D of humanoid robots since 1996 with two scientific focuses. The first one is to investigate the scientific principles which will enable humanoid robots to demonstrate human-like skills. In other words, the objective of this research focus is to develop the outer loop of perception, planning, and control, which will enable humanoid robots to achieve vision-centric intelligence. The second focus is to investigate scientific principles which will enable humanoid robots to demonstrate human-like communications with the use of natural languages. More specifically, the objective of this research focus is to develop the outer loop of perception, composition, and communication (with the use of natural languages), which will enable humanoid robots to achieve speech-centric intelligence.

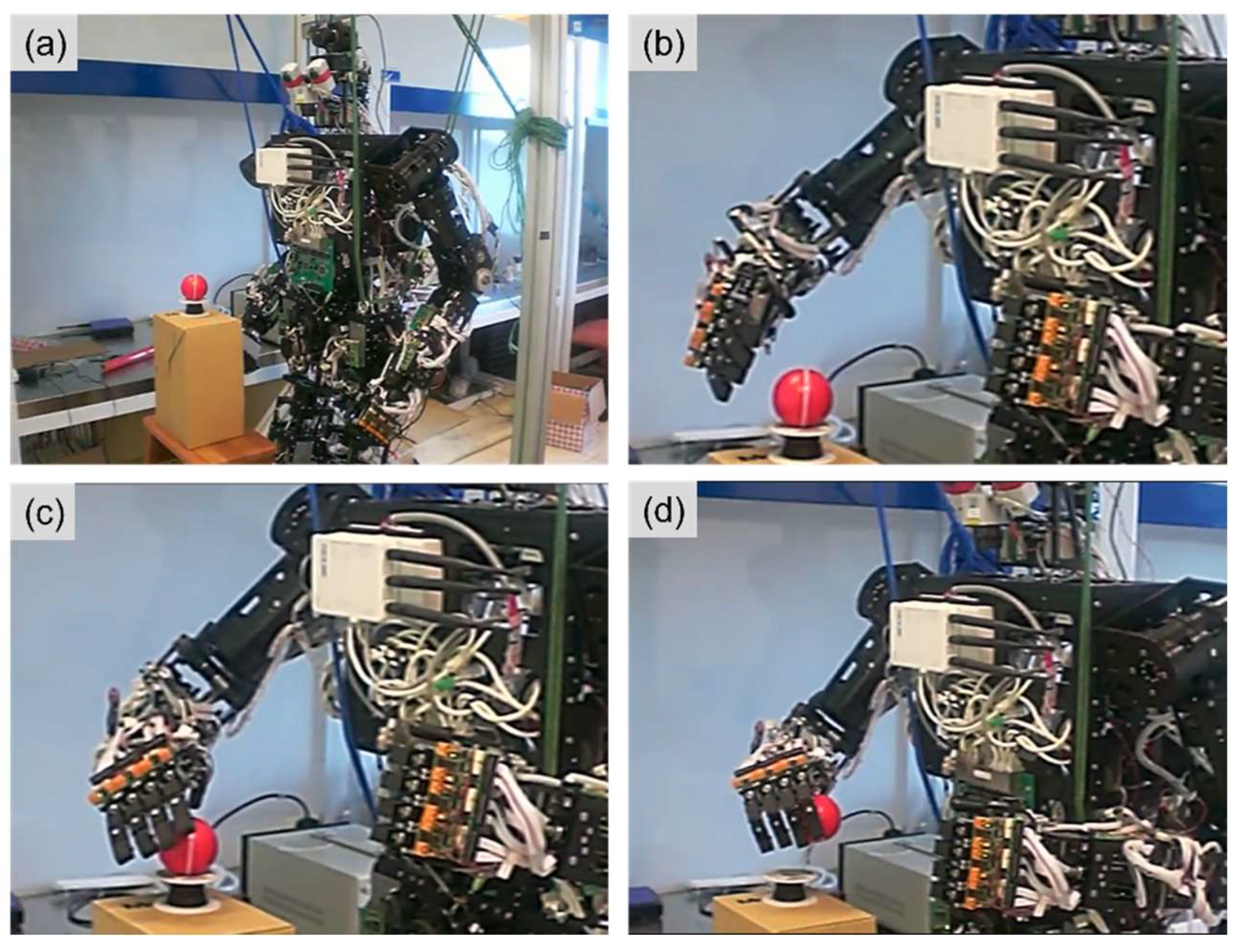

As shown in

Figure 1, our first research focus is motivated by the application of deploying humanoid robots as workers in future manufacturing industries, while our second research focus is motivated by the application of deploying humanoid robots as tour guides in museums. The prototypes shown in

Figure 1. have been developed by our teams in the past years. Our continuous effort is now more or less toward achieving the top-down design of a cognitive mind which will make future humanoid robots to be teachable with the use of natural languages [Xie, M. (2003); Wächter, M. et al, (2018)].

This paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we will discuss the problems encountered during the journey toward achieving teachable humanoid robots (and many other robots) under the context of using natural languages. In

Section 3, we will highlight existing works which are related to the top-down design of teachable minds or human-like minds, which will enable humanoid robots to be teachable with the use of natural languages. This section also includes basic introduction to ChatGPT (GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer) and Restricted Coulomb Energy (RCE) neural network. In

Section 4, we will present an engineering perspective about the foundation of human-like brains. We hope that the contents in Sections 4 will be convincing enough for us to say that mind is mind while brain is brain, and that there is no clear interplay between the top-down design of human-like brains and the top-down design of human-like minds. In

Section 5, we will describe the details of a cognitive framework, which could serve as a foundation to guide the top-down design of a teachable mind, or human-like mind, with the use of natural languages. On the ground of the proposed cognitive framework underlying teachable minds, some experimental results are included in

Section 6. Finally,

Section 7 concludes this paper.

2. Problem Statement

Strictly speaking, the history of artificial intelligence (AI), which has the origin back to the study of intelligence and mind, is much longer than the history of robotics, which has the origin back to the study of motion and mechanism. Over the past decades, both fields have made tremendous progress. For example, robotics research has already achieved a very successful contribution (e.g., robot-integrated manufacturing) in our modern industry. However, AI research is still struggling with the attempt of making impactful outcome [Arrieta et al (2020); Zhang et al (2020); Xie et al (2021)].

Interestingly, we now see the convergence of these two fields, which could become a unified discipline under the umbrella of humanoid robotics. The main reason behind this claim is the fact that human beings are the most advanced creatures of nature, while humanoid robots should be the most advanced creatures of human beings. Also, it is true to say that humanoid robotics research generally addresses all, or one of, the following three major issues [Hirose et al (2007)]:

How to design a humanoid robot’s agile body with absolute controllable motion?

How to design a humanoid robot’s computational brain which could be as similar as possible to human beings’ one as expected by many people in the public?

How to design a humanoid robot’s teachable mind which could be as similar as possible to human beings’ one as anticipated by many people in the public?

So far, there is no major obstacle toward the design of a humanoid robot’s agile body with nicely controllable motion. However, progress is still expected toward achieving human-like brains. In

Section 4, we will outline a very likely new finding about our brain. This finding may help guide the development of the 5

th generation of digital computers or electronic brains in future [Gill et al (2022)].

It goes without saying that the area, which still needs much more effort and attention from our research community, is the design of cognitively intelligent mind which could make humanoid robots to be teachable with the use of natural languages. The stagnation in this area is largely due to the existence of some superficial problems caused by some inappropriate beliefs in AI research community [Arrieta et al (2020)], for example:

The first inappropriate belief is to meaninglessly say that our brain is a complex system which is built on top of a massive network of interconnected neurons. This inappropriate belief is equivalent to the statement saying meaninglessly that a robot is a complex system which is built on top of a massive network of interconnected molecules. In

Section 4, we will provide evidence to support a new finding which is to meaningfully say that a brain is a complex system that is built on top of a massive network of neural logical gates. As we know, logical gates are the foundation of today’s digital computers. Surprisingly enough, the new finding suggests that a human-like brain could be considered as being a massive network of digital computers [Cross et al (2009)].

The second inappropriate belief is to blindly say that a network of artificial neurons is a universal solution to all problems if they could be solved by our brain. For example, a person can learn how to drive and how to swim. Hence, people inappropriately believe that procedural knowledge, which is different from propositional knowledge, could also be represented by an artificial deep neural network. In

Section 3, we will provide examples to show that artificial deep neural networks are simply graphical representations of equations of variables, which must be smooth and differentiable. Such prerequisites are only satisfied by systems of variables, but not systems of events, episodes, and stories, etc. For example, the history of a country could never be described by systems of equations of differentiable variables [Roberts et al (2022)].

The third inappropriate belief is to wrongly say that our mind is part of our brain. This inappropriate belief is equivalent to the statement saying that the blueprint of operating systems is part of the blueprint of digital computers. It is worth noting that research about the nature of our mind, intelligence or wisdom is not a new topic in the history of human beings. This topic has been studied many thousand years ago by experts in religions. Their findings are largely ignored by today’s scientific communities [Rosenthal (1991); Smythies (2014)]. However, their findings about the truths behind our brain and mind are verifiable with repeatable experiments. Hopefully, public research institutions could be tasked to collect evidence or findings discovered and demonstrated by experts in religions.

On top of the above-mentioned inappropriate beliefs which contribute to the creation of superficial problems, there are misleading terminologies which also contribute to the creation of superficial problems. For example, some serious misleading terminologies include the following popular cases [Newman-Griffis et al (2021); Roberts et al (2022)]:

Machine tuning or calibration is misleadingly defined as machine learning. If we compare machine learning with human learning, it is easy for us to know what the true meaning of learning should be. We should not forget the fact that a person may spend many years to learn in schools and universities in order to obtain higher degrees. Especially, if a robot is not teachable with the use of natural languages, it could learn nothing which is written in the form of texts in natural languages.

Text processing is misleadingly defined as natural language processing (or NLP in short) [Cambria et al (2014)]. Natural languages are tools for human beings, and future humanoid robots, to use for the purpose of composing meaningful texts as well as reconstructing meanings from intentionally composed texts. In computer vision, image processing has never been defined as electronic camera processing (or ECP in short). Under the umbrella of NLP, another misleading terminology is LLM (i.e., large language model [Kasneci et al (2023)]) which in fact refers to large text model (or LTM) for the purpose of representing meaningful texts in a natural language.

Vectorizing or quantizing words is misleadingly defined as word embedding [Selva et al (2020)]. In mathematics, a word in a western language could be easily represented by its characters’ ASCII codes, each of which is weighted by a base number to the power which is equal to the position of a character. For example, the quantization of the word ‘love’ in English by using ASCII codes will result in a feature vector such as

where b is a base number such as 2, 3, 4, etc. However, instead of using less meaningful values, a better way to numerically represent a word is to use the values which are attributed to a word’s meaningful properties and constraints in both the physical world and a conceptual world. We will discuss this topic more in

Section 5.

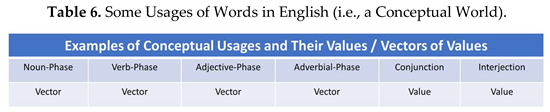

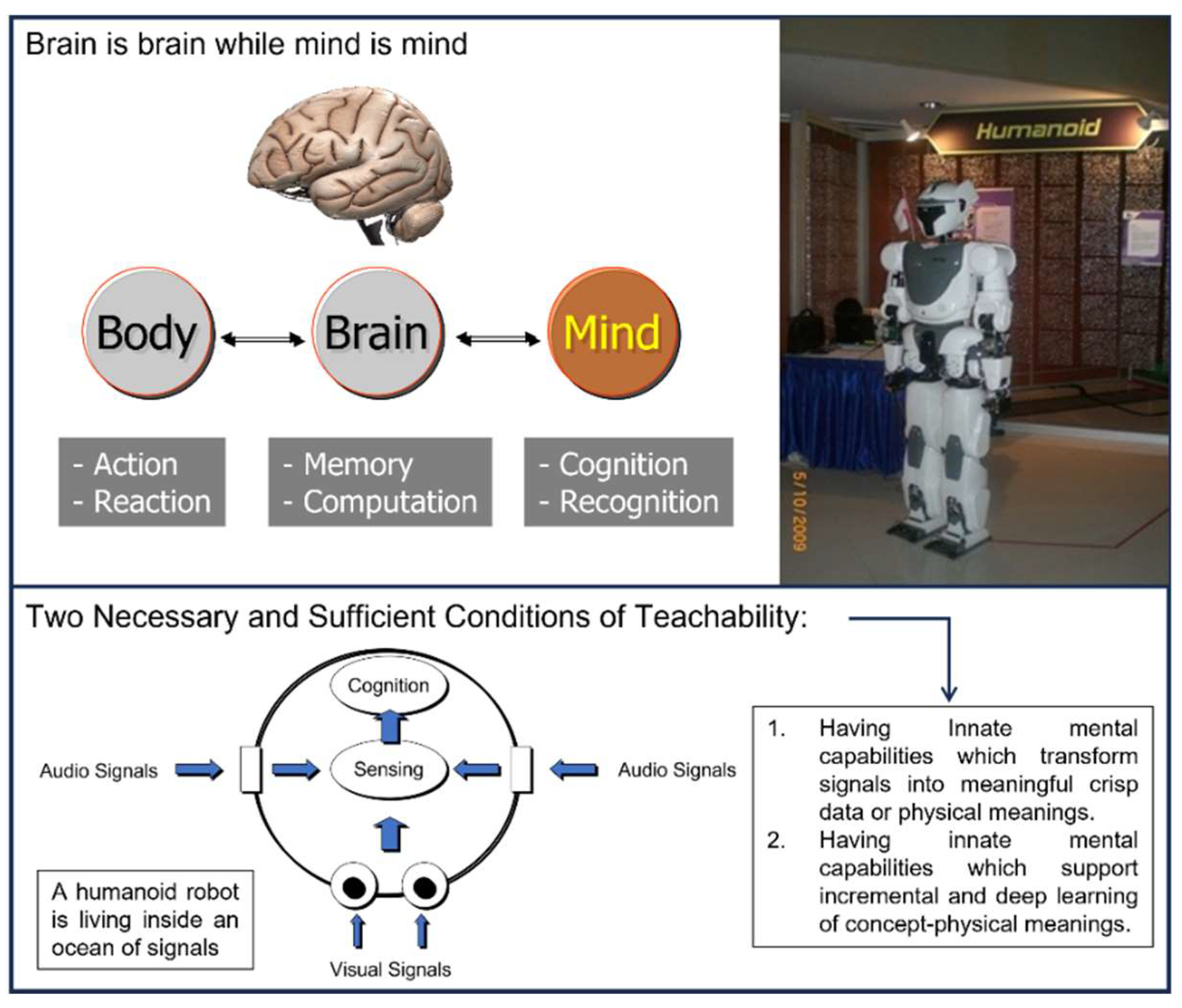

In this paper, we advocate the Body-Brain-Mind model as shown in

Figure 2. This model helps us to better understand the nature of a humanoid robot’s body, brain, and mind. For example, the primary functions of a humanoid robot’s body are to perform actions and reactions. On the other hand, the primary functions of a humanoid robot’s brain are to do computation and memorization, while the primary functions of a humanoid robot’s mind are to do cognition and recognition. Clearly, this model will prevent us from being distracted by superficial problems as mentioned above [Xie et al (2021)].

With the Body-Brain-Mind model as shown in

Figure 2., the key problem addressed by this paper could be formulated as follows:

How to design a humanoid robot’s cognitively intelligent mind which will make it to be teachable with the use of natural languages?

More specifically, the challenge, which needs to be addressed as the top priority in the study of teachable mind, is to find the answers to the following two questions:

What are the physical principles which will enable a humanoid robot to gain its innate mental capabilities of transforming signals into meaningful crisp data?

What are the physical principles which will enable a humanoid robot to gain its innate mental capabilities of undertaking incremental learning as well as deep learning with the focus of associating conceptual labels in a natural language to meaningful crisp data?

3. Related Works

Today’s robots are all programmable or reprogrammable due to the use of programming languages [Yamazaki et al (2015)]. For example, all industrial robots come with a device called Teach Pendant. Although the key word Teach appears inside the name of the device, it does not mean that Teach Pendant is the evidence which proves an industrial robot’s status of being teachable with the use of natural language. In other words, the ability of being programmable or reprogrammable only enables a robot to receive and execute instructions from human operators in the form of programs. Such ability will not directly enable a robot to undertake communications or conversational dialogues as shown in

Figure 1. However, it is worth noting that the ability of being programmable or reprogrammable is a necessary condition for the implementation of physical principles which will enable a robot to be teachable.

Here, we focus our survey on existing works which could contribute to the achievement of making a humanoid robot to be teachable with the use of natural languages. Obviously, one of today’s popular existing works is ChatGPT (NOTE: GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer) [Vemprala et al (2023)]. Before we will be able to clearly explain the working principle of ChatGPT, it is necessary for us to first give a short overview about artificial neural network and artificial deep neural network [Galvan et al (2021)].

3.1. Mathematics Behind Artificial Neural Network

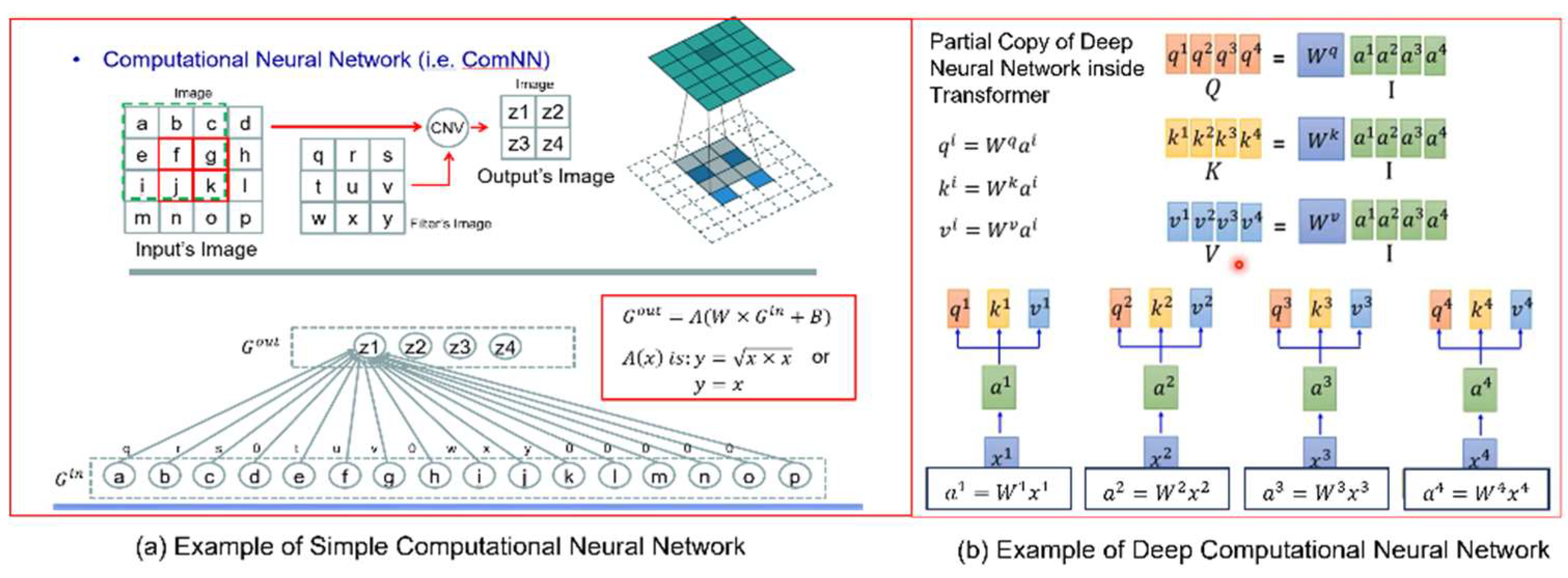

When we talk about neural networks, our mind will immediately visualize the images of diagrams which could be as similar as to the ones shown in

Figure 3.

Interestingly,

Figure 3(a) clearly shows that an artificial neural network is analytically a system of linear equations, which is coupled with a so-called activation function for the purpose of adding non-linearity to the relationship between input and output. Hence, the analytical representation of an artificial neural network with a single hidden layer could be described by the following equation in matrix form:

where

is the input vector or matrix,

is the output vector or matrix,

is the matrix of weighting coefficients which could be the values of a kernel image (or template),

is the bias vector or matrix, and

is the activation function at the output layer, which could be SoftPlus function (i.e.,

), SoftMax function (i.e.,

in which

is a possibility function or probability function), Sigmoid function (i.e.,

), etc.

Here, it is worth mentioning that there are three ways for us to determine the values of weighting coefficients inside matrix . They are:

Top-top design method: The values inside matrix are chosen by the designer so as to achieve any intended outcome (e.g., computation of derivatives).

Bottom-up optimization method: The values inside matrix are calculated by an optimization process such as backpropagation, which minimizes a cost function. In this case, training data must be available in advance.

Calibration method: The values inside matrix are calculated by solving Eq.(1) if training data is available. This is equivalent to a process of doing least-square estimation.

In addition, it is important to remind us that Eq.(1) is only useful for the representation of some propositional knowledge (e.g., equations of lines and curves, etc), but not suitable for the representation of procedural knowledge (e.g., skills of driving or swimming, etc).

3.2. Mathematics Behind Artificial Deep Neural Network

If we treat vectors

and

as position vectors in a space, Eq.(1) could be interpreted as transformation of coordinates from one space to another space. In principle, we could repeatedly undertake the transformation along a series of spaces. Such repeated transformations will result in the so-called artificial deep neural network. One typical example of artificial deep neural network is a series of neural networks which undertake convolutions. Another typical example of artificial deep neural network is a series of neural networks inside ChatGPT’s transformer as shown in

Figure 3(b). Analytically, an artificial deep neural network could be described by the following equation in matrix form:

where

represents the number of hidden layers (i.e.,

),

is the matrix of coefficients at

hidden layer,

is the bias vector or matrix at

hidden layer, and

is the activation function at

output layer. It is important to take note that the sizes of the weighting coefficient matrices do not need to be the same as long as any pair of two adjacent matrices in multiplication satisfy the constraint in which the number of columns in the left matrix is equal to the number of rows in the right matrix.

Similarly, there are two ways for us to determine the values of the weighting coefficients inside matrices . They are:

Top-down design method: The values inside each of matrices are chosen by the designer so as to achieve any intended outcome (e.g., computation of derivatives)

Bottom-up optimization method: The values inside all matrices are calculated all together by an optimization process such as backpropagation, which minimizes a cost function. In this case, training data must be available in advance. In literature, this process is called Deep Learning. Clearly, optimization process is very much different from learning process which is routinely undertaken by human beings. Obviously, a better terminology is to call it Deep Tuning or Deep Calibration.

Also, it is important to remind us that Eq.(2) is only useful for the representation of some propositional knowledge (e.g., equations of lines and curves, etc), but not suitable for the representation of procedural knowledge (e.g., skills of driving or swimming, etc).

3.3. Working Principle Behind ChatGPT

R&D works on intelligent voice response (IVR) systems are not new [Schmandt et al (1982)]. Also, R&D works on machine translation are not new [Poibeau (2017)]. However, it is only recently that we see the excitement about machine’s mental capabilities of undertaking communication or conversational dialogue with the use of natural languages. This excitement is fueled by the release of various versions of ChatGPT. Hence, it is important for us to have a basic understanding about the working principle of ChatGPT and to see whether or not the working principle behind ChatGPT consists of the answer to the question of how to achieve the goal of making future humanoid robots to be teachable with the use of natural languages [Spiliotopoulos et al (2001)].

In literature, there are many good papers which make efforts to explain the details of the working principle behind ChatGPT. Here, we only provide a basic explanation at a conceptual level without go into too much the technical details which will occupy too many pages. Also, we will not use the original terminologies of Transformer inside ChatGPT because they are not informative nor meaningful for people with engineering or mathematical mindsets [Chomsky et al (2023)].

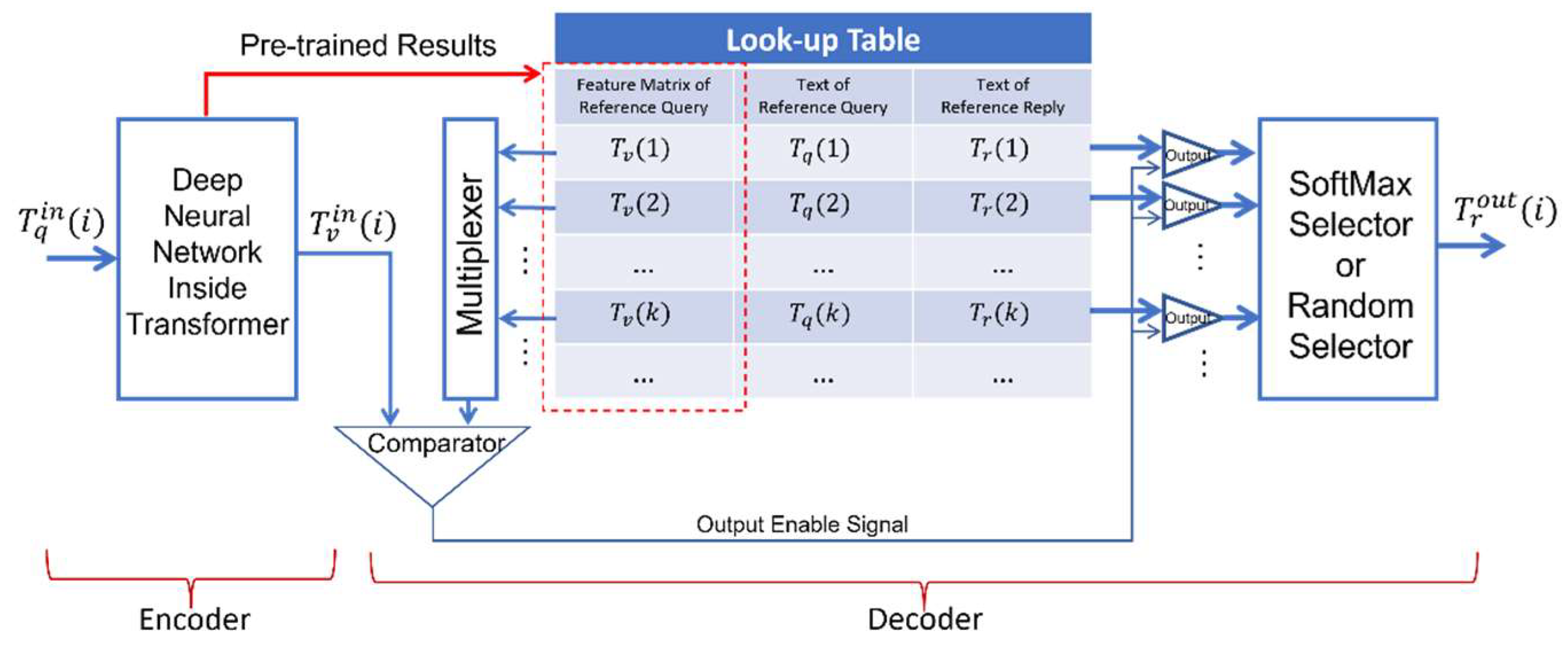

Refer to

Figure 4. The philosophy behind ChatGPT comes from the main idea of combining the working principle of doing machine translation (i.e., translating sentences in one natural language into sentences of other natural languages) together with the simplicity of using look-up table to index and to retrieve output. For example, input text

(i.e., a list of words in a query which seeks for a reply) in any natural language could be represented by value matrix

which could be associated with output text

(i.e., a list of words in a reply to a query) in the same or another natural language. In practice, if input text

is given, it could be converted into its feature matrix

(i.e., a matrix of feature values obtained by vectorizing all the words of input text). In ChatGPT, feature matrix

is produced by a series of transformations which occur inside a module named as Transformer.

Now, if we have a list of reference queries in the form of reference query texts

, we could pre-train the ChatGPT to obtain a list of feature matrices

. Also, during the pre-training stage, we could manually associate a list of reference replies in the form of reference replies’ texts

to the list of reference queries. As a result, we will have three lists which could be put together to form a query-to-reply look-up table as shown in

Figure 4. This query-to-reply look-up table could be huge in order to memorize all possible pairs of queries and replies in one or more natural languages.

After the pre-training stage, a ChatGPT is ready to be deployed to the public for use. For example, when a ChatGPT receives i-th query , i-th query’s text is first converted into its corresponding feature matrix . Subsequently, feature matrix is compared with all the feature matrices inside the first column of the query-to-reply look-up table. In mathematics, a comparison between two vectors could be the calculation of their cosine distance. The successful comparisons (e.g., the cosine distance is greater than a threshold value) will trigger the output of enable signals which will release a single or multiple acceptable replies as output from the query-to-reply look-up table.

If there are multiple acceptable replies as output, one way is to activate SoftMax Selector which will output the reply with the maximum value of probability or possibility. Alternatively, Random Selector could be activated to randomly choose one among all the acceptable replies, as output. In this way, users will feel that a same query may receive different replies at different times.

Now, we may raise the following questions [Chomsky et al (2023)]:

Does ChatGPT have its own intelligence?

Is ChatGPT able to initiate or lead conversational dialogues with the use of natural languages (e.g., to give a lecture about robot kinematics)?

Is ChatGPT teachable with the use of a new natural language without going through a new round of pre-training which requires a huge of amount of new training data (i.e., texts)?

Obviously, the answers to the above questions are negative. The reason is simply because ChatGPT is a successful software under the paradigm of achieving computer-aided human intelligence, which is not the same as computer intelligence or computer’s self-intelligence. Mathematically speaking, the conversion of i-th query text query into i-th feature matrix destroys the concept-physical meanings behind i-th query text query completely.

Then, the next question will be: how to preserve the concept-physical meanings inside any meaningful data such as texts and images? The remaining part of this paper is making the attempt to describe a solution.

3.4. Working Principle Behind Restricted Coulomb Energy (RCE) Neural Network

Here, it is worth mentioning the famous statement made by the great inventor Nikola Tesla, which says that if we would like to understand the secret of the universe, it is good enough for us to think in terms of energy, vibration, and frequency. This statement could be called Energy-Vibration-Frequency model of the universe.

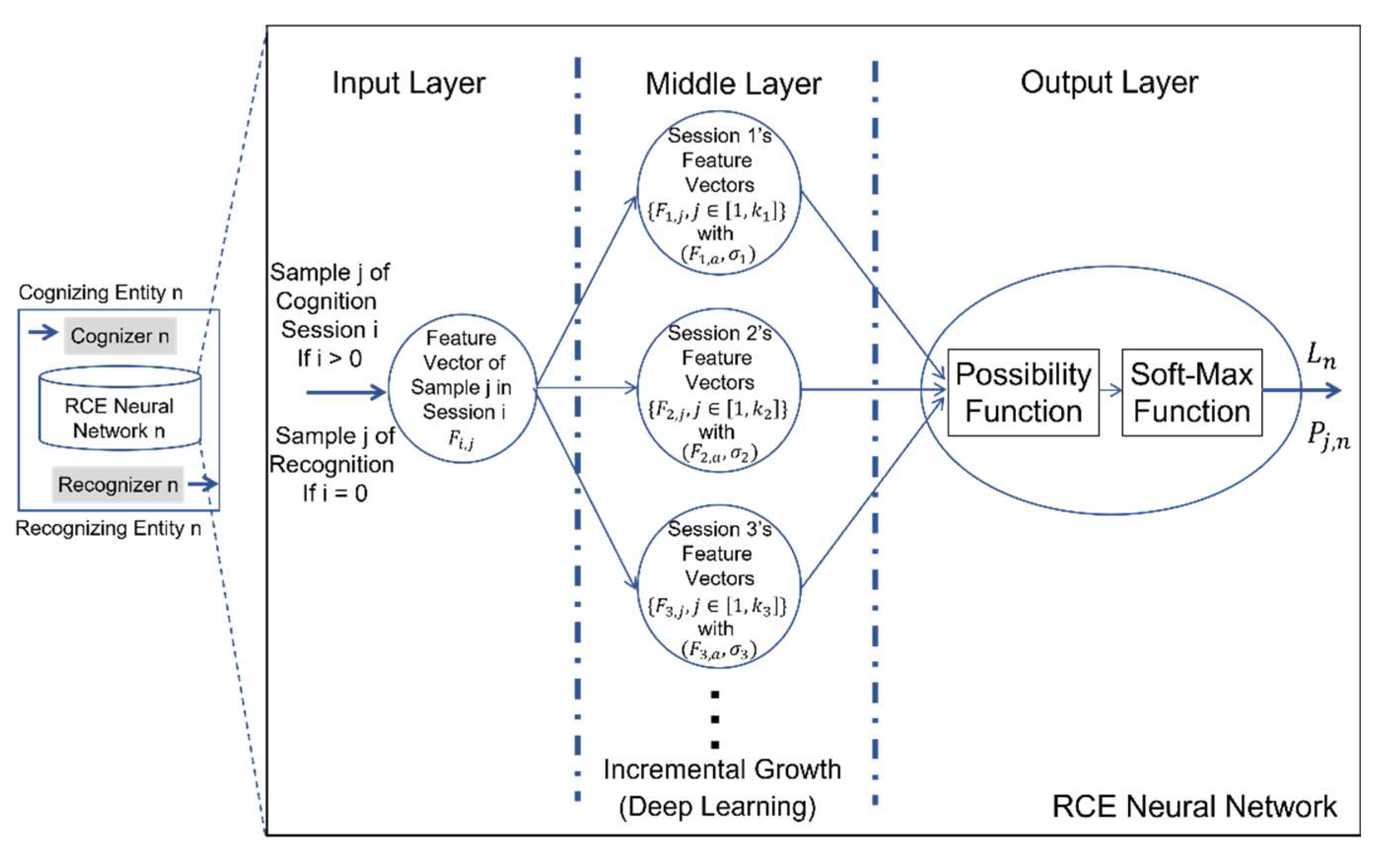

In a similar vein, it is interesting for us to say that if we would like to understand the secret of human-like mind, it is good enough for us to think in terms of space, vector, and time. Interestingly, the scientific principle, which supports this statement of Space-Vector-Time model of human-like mind, is the discovery and invention of Restricted Coulomb Energy (RCE) neural network by a team led by a laureate of 1972’s Noble Prize in Physics. With the use of RCE neural network, a general blueprint underlying a human-like mind for cognizing and recognizing any meaningful entity is shown in

Figure 5 [Xie et al (2023)].

As shown in

Figure 5., a RCE neural network consists of three layers. The input layer consists of a single node which represents a vector. The middle payer consists of a list of nodes, each of which represents a vector in a vector space, while the output layer also consists of a single node which represents a conceptual label such as symbol or word in any natural language. More specifically, the working principle underlying any pair of cognizer and recognizer, which is dedicate to entity

, is summarized as follows:

During the process of cognition dedicated to the learning (or re-learning) of any new (or existing) entity

, training session

will consist of a set of training data samples (e.g., words or sentences in a natural language, images of reference entities, etc). If training data sample

in training session

is represented by its feature vector

, a set of training data samples, denoted by

, from training session

could be represented by:

where

is the number of training data samples in set

. In addition, set

allows the RCE neural network to self-determine the following two important parameters:

The mean vector of set .

The standard deviation from the mean vector to all the vectors in set .

Graphically, these two parameters define a hyper-sphere in a high dimensional space. Moreover, at the middle layer, the cognition process will assign a conceptual label to represent the learnt conceptual output from training session .

With the above learnt concept-physical knowledge which are stored at each node inside the middle layer, the node at the output layer will be able to compute the value of possibility

which indicates the possibility for the mind to believe that input sample data

should trigger conceptual label

as output. The value of possibility

could be computed by the following possibility function:

Finally, a SoftMax function will determine output label

from recognizer

as follows:

Clearly, a RCE neural network takes a feature vector (e.g., ) as input and generates a conceptual label (e.g., ) as output. A conceptual label could be any meaningful symbol or word in any natural language. So far, we believe that RCE neural network should be the best answer to the AI’s long-lasting problem of symbol grounding. With the use of RCE neural network, we could easily design a pair of cognizer and recognizer for both incremental learning and deep learning of any meaningful entity or signal.

4. Engineering Foundation Behind Human-like Brain

Today, if people ask this question of what a robot is, certainly, the answer will not be the statement saying that a robot is a network of massively interconnected molecules. Instead, a meaningful answer should be to say that a robot is a network or a system of interconnected links, joints, motors, sensors, microcontrollers, computing units, and power supply units, etc. [Xie (2003)].

Similarly, if we ask computer scientists about the question of what a digital computer is. Certainly, none of them will say that a digital computer is a massive network of interconnected transistors. Instead, they will say that a digital computer consists of central processing units (CPU), memory devices, and input/output (I/O) devices, etc. At a deeper level, some experts may say that a digital computer is a massive network of interconnected logical gates which are the foundation of CPUs, memory devices, and I/O devices, etc.

However, in the AI research community, there are many people who still believe that our brains are simply massive networks of interconnected neurons. This belief is not wrong, but meaningless because it leads many people to further believe that massive networks of neurons are the universal solutions to problems if these problems could be solved by human beings’ brains. Unfortunately, this is a misleading belief because of the reason given below.

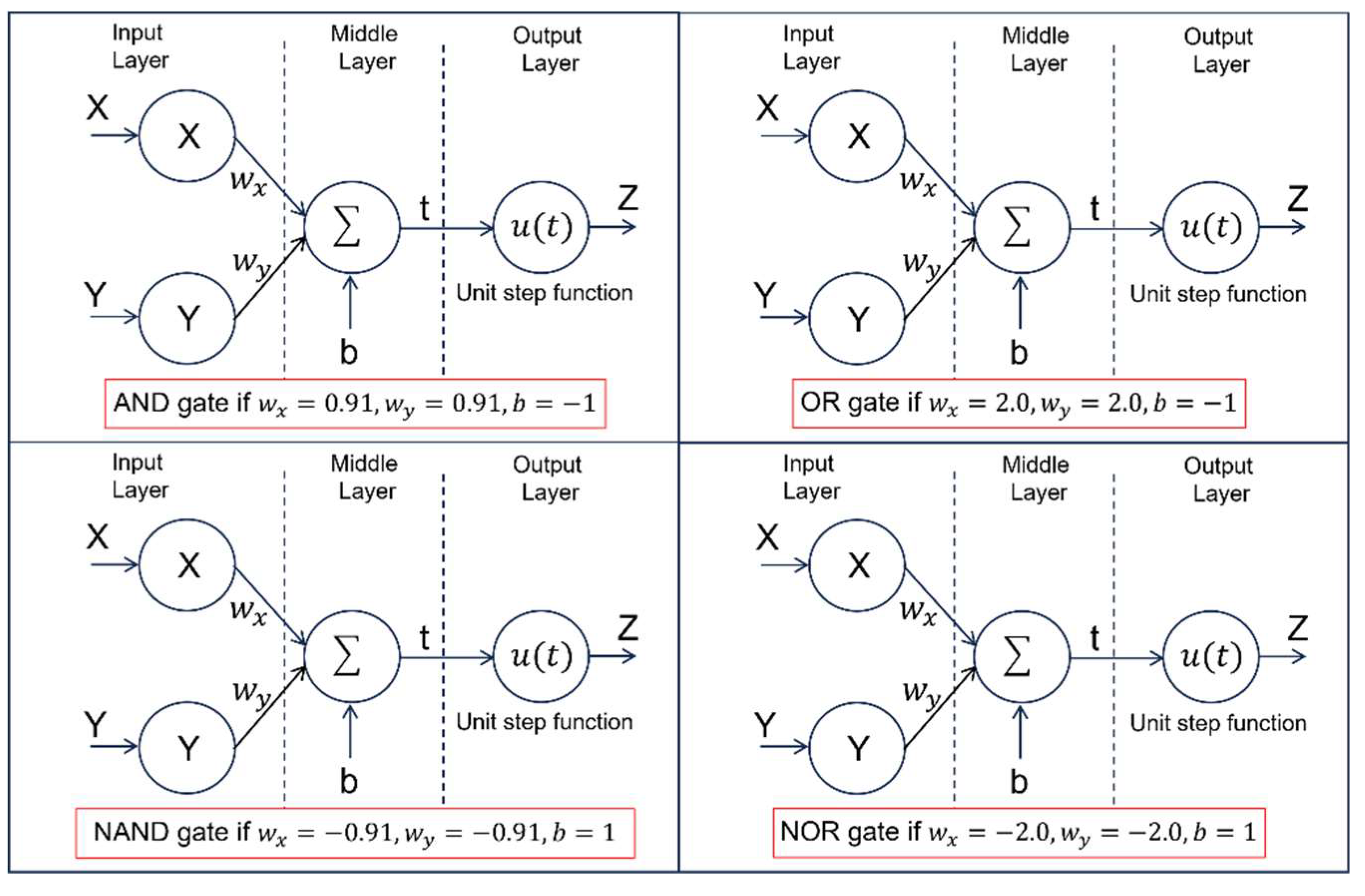

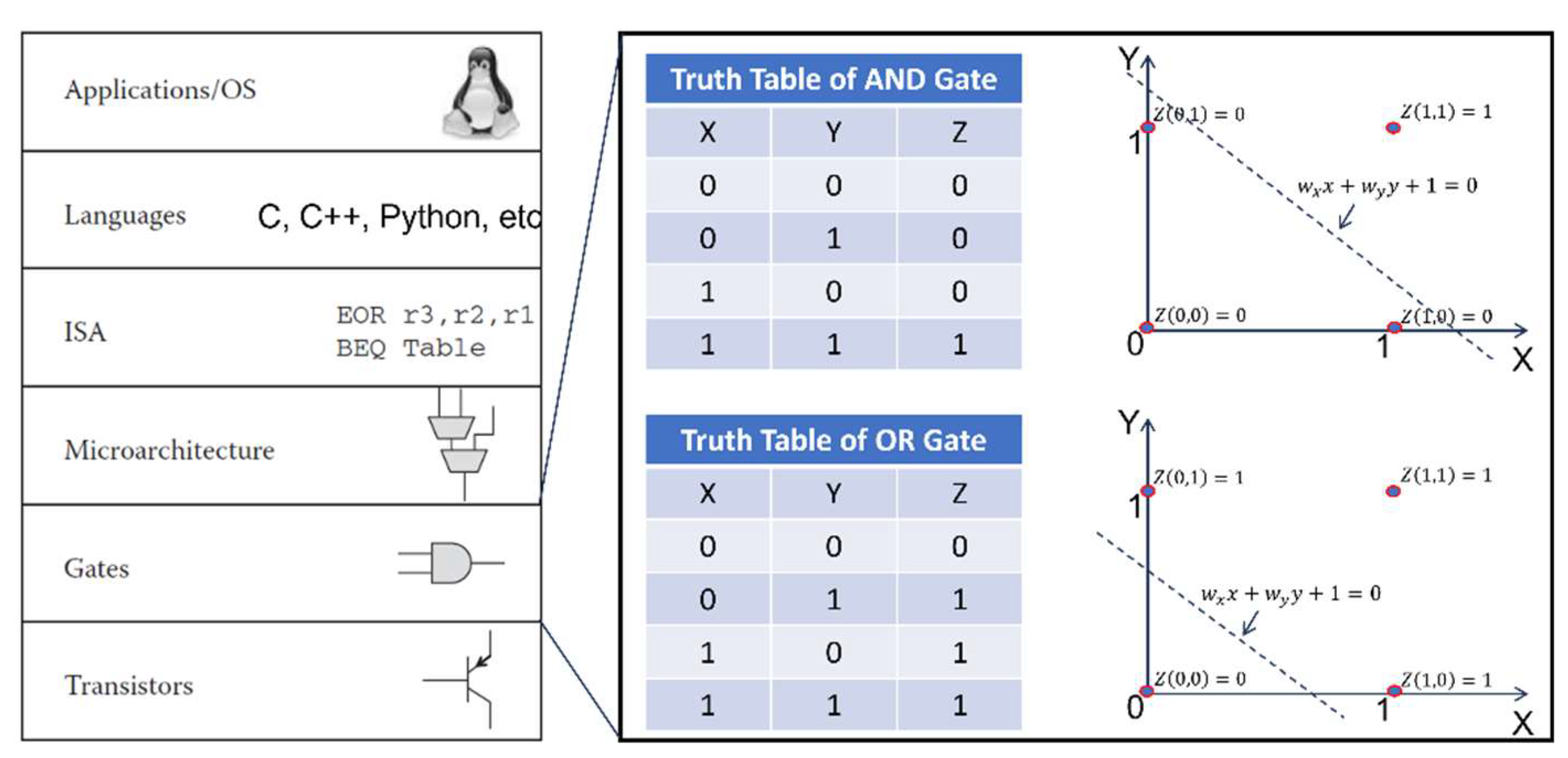

Here, we offer a different perspective about the foundation of human-like brains. As shown in

Figure 6., logical gates [Jiao et al (2022)] could be readily constructed from neurons of biological brains such as human beings’ brains.

Moreover, if we denote

a AND gate,

a OR gate,

a NAND gate, and

a NOR gate, the circuit of XOR gate (i.e.,

) could be readily constructed by the following logical equation of design:

The above truth leads us to make this exciting statement which is to say that the foundation of human beings’ brains is the same as the foundation of today’s digital computers. This exciting statement is nicely illustrated by

Figure 7. which clearly indicates that there is a common ground between human-like brains and digital computers. On the ground of logical gates, we could make this astonishing assumption saying that a human-like brain is a massive network of digital computers at a higher level. This fact gives us the engineering explanation about the answer to the question of why human-like brains are so powerful. Nevertheless, this new finding is extremely important because it indicates a new direction for us to venture into for the purpose of developing 5

th generation of digital computers or human-like electronic brains [Meier (2017); Kendall et al (2020)].

Before we move on to the next section, it is worth mentioning a small highlight which is to say that bottom-up optimization process will not work with the types of neural networks in

Figure 6. because there are infinite number of workable solutions for the weighting coefficients, all of which are acceptable ones as well as good ones.

5. Key Details Behind Design of Human-like Teachable Mind

By now, it is clear to us that today’s digital computers could become human-like electronic brains while today’s operating systems could become human-like cognitive minds. This is why we advocate the separation of the study of human-like cognitive mind from the study of human-like electronic brain. Since we know already that the engineering foundation of human-like brains are logical gates, then, the next question will be what the physical principles behind the top-down design of teachable minds should be.

Roughly speaking, today’s operating systems inside digital computers (or future human-like electronic brains) consist of modules or computational processes which are dedicated to memory management, CPU management, and the scheduling of multiple tasking (i.e., the planning and execution of programs which share common CPUs and common memory units). In other words, today’s operating systems inside digital computers have zero mental capability which could transform signals into the cognitive states of knowing the meanings behind these signals. Therefore, today’s operating systems inside digital computers are not good enough to enable humanoid robots or other machines to be teachable with the use of natural languages. As a result, the top-down design of human-like teachable minds is still one of the biggest challenges in science and engineering.

5.1. Key Characteristics of Human Mind

We human beings live inside an ocean of signals. These surrounding signals enable us to see, to read, to hear, to dream, to imagine, to create, to compose, to study, and to imitate, etc. This should be the upmost important observation about human-like teachable minds.

The second important observation is the fact that the best way to represent knowledge by human-like teachable minds is the use of natural languages with the extension to include technical languages (i.e., mathematics) and programming languages. The evidence behind this observation is the libraries in various locations on Earth. Inside these libraries, we could find and retrieve all kinds of knowledge which have been discovered or invented by human beings so far. Moreover, all the knowledge could be described in the form of texts in any human language. Here, a human language means a natural language with its extensions to include technical languages and programming languages [Xie et al (2021)].

In addition to the two observations mentioned above, the top-down design of human-like teachable minds must also pay attention to the following important realities:

The first reality is the fact about the motivation which drives human minds to invent natural languages. It is true to say that the motivation behind the invention of natural languages is our ancestors’ desire to represent and to communicate the knowledge which have been discovered from the physical world. Here, it is worth mentioning that the inventive aspect of natural languages has been largely overlooked in our educational systems at the levels of kindergartens, primary schools, and secondary schools. This could be the major reason contributing to the difficulty faced by many students when they learn natural languages.

The second reality is the fact about the fuzzy aspect of human being’s sensory systems, which has been largely overlooked by the AI research community. This fact tells us that all the sensory systems inside a human being are fuzzy systems. For example, our skin systems are not able to tell the crisp values of temperature, humidity, and pressures. Our vision systems are not able to tell the crisp values of geometries and colors. This reality implies that signals entering human being’s sensory systems will first undergo the transformation from signals to meaningful crisp data, and then undergo the process of fuzzification which transforms crisp data into conceptual labels in any human language [Zimmermann (2001)].

The third reality is the fact about the representation of knowledge with the use of human languages which include natural languages, technical languages, and programming languages. Most importantly, the representation of knowledge with the use of human languages (which include natural languages) will result in huge collections of texts which could be better named as individual Conceptual Worlds or individual Mental Worlds. In this paper, we will stick to the terminology of individual Conceptual Worlds. Also, it is true to say that the conceptual worlds, which have been internalized inside the minds of different individuals, are not the same. In other words, the same knowledge in the physical world may result in different versions of internalized conceptual worlds among different individuals. Most importantly, the process of learning is to internalize the knowledge from the physical world by each learner. Such process has no direct connection with the process of tuning the internal parameters inside a system or a machine.

The fourth reality is the fact about the unprecedented strength of human mind. It is obvious to us that human minds are very powerful in playing with knowledge in both the physical world and a conceptual world. Most importantly, the mental processes behind such unprecedented strength of a human mind include at least the following three dualities, which are the duality between cognition and recognition, the duality between analysis and synthesis, and the duality between encoding and decoding. We will discuss these three dualities in more details in subsequent sections.

The fifth reality is the fact about the unprecedented weakness of human mind. For example, our minds have tremendous difficulty in undertaking complex computations as well as complex compositions. For example, it is very hard for our minds to find the roots of a polynomial equation of degree if is greater than five (5). Also, it is very hard for our minds to write down all the meaningful sentences with a set of given words if is greater than 50. This reality indicates that a humanoid robot could outperform a human being in terms of some mental capabilities such as complex computations as well as complex compositions.

5.2. Blueprint of Human-like Teachable Mind

One of the last frontiers in science and engineering should be the discovery of the physical principles behind the top-down design of human being’s mind. So far, we know a lot of astonishing phenomena demonstrated by human being’s mind. However, we are still struggling with the understanding of the physical principles which enable human beings to see, to hear, to read, to create, to compose, to communicate, to study, and to imitate, etc., in some meaningful manners [Barrett (2011)].

The above situation is very much like the case in which our ancestors have observed the flying birds in the sky for thousands of years. However, it is only about one hundred years ago when two brothers in USA have made the first significant attempt of inventing flying machines, then we started to fully discover the theory of aerodynamics. In this way, we could then apply these theoretical findings to gradually improve the top-down design of today’s aircrafts. Here, we would like to follow the same philosophy of doing invention first and discovery later.

We know that all signals are important to the mind of a humanoid robot. However, without loss of generality, we assume that input to the mind of a humanoid robot are visual signals as well as audio signals.

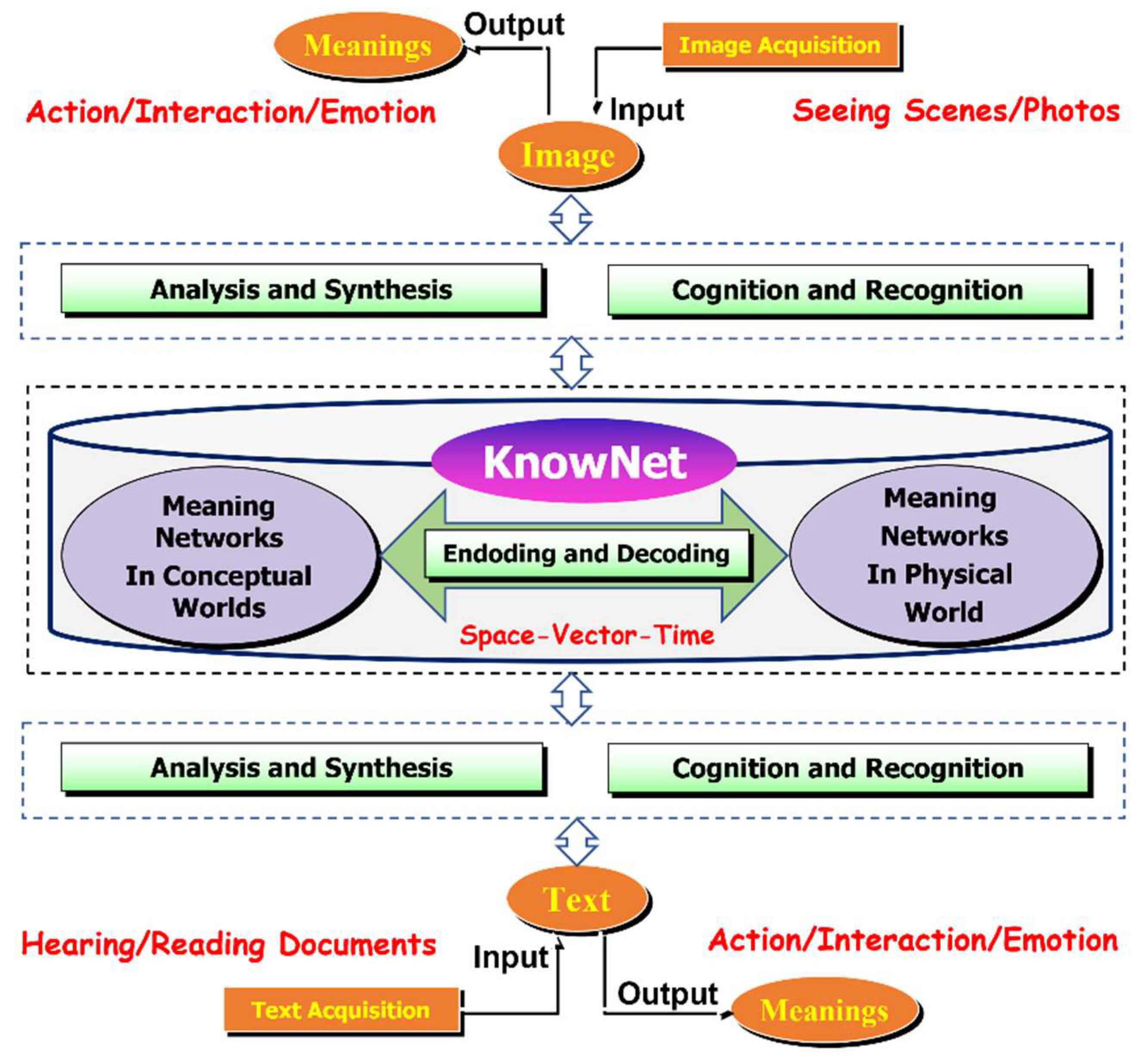

As shown in

Figure 1., if a humanoid robot is to exhibit vision-centric intelligence (i.e., Perception-Planning-Control loop) as well as speech-centric intelligence (i.e., Perception-Composition-Communication loop), its teachable mind must include at least three mental dualities as shown in

Figure 8. These three mental dualities are:

Mental duality No.1 is the duality between cognition and recognition. The objective of cognition module is to associate the physical world’s feature vectors (i.e., physical knowledge) with conceptual labels (i.e., conceptual knowledge) in a human language (i.e., a natural language with its extension to include technical languages and programming languages). The outcome obtained from a session of cognition process is called concept-physical knowledge. These concept-physical knowledge are memorized in a database which is called vectorized database or vectorized space, as shown in

Figure 5. In literature, a cognition process is also called learning process with the goal of memorizing newly received concept-physical knowledge. In contrast, the objective of recognition module to retrieve conceptual labels associated with given feature vectors which have been learnt beforehand. Clearly, recognition process depends on both cognition process and the availability of vectorized database of learnt concept-physical knowledge. In our research works, a vectorized database of learnt concept-physical knowledge is called KnowNet which will be discussed in detail later.

Mental duality No. 2 is the duality between encoding and decoding. From the viewpoint of knowledge representation, the association of conceptual labels to feature vectors could be called encoding, while the retrieval of feature vectors associated to conceptual labels are called decoding. It is important to take note that the duality between encoding and decoding is different from the duality between cognition and recognition. More specifically, a typical scenario of application with the use of encoding process is image understanding, while a typical example of application with the use of decoding process is text understanding. Another important application with the use of the duality between encoding and decoding is machine translation. For example, an input text in one natural language could be decoded into its physical meanings, which are in return encoded into output text in another natural language.

Mental duality No. 3 is the duality between analysis and synthesis. The objective of analysis module is to extract the details of concept-physical meanings from an input such as texts or images, while the objective of synthesis module is to plan, or to compose, meaningful outputs such as motions or speeches. A typical example of application with the use of the duality between analysis and synthesis is motion planning in robotics. Another typical scenario of application is human-robot interaction at cognitive level (i.e., conversational dialogues with the use of natural language).

Clearly, the interplay among these three dualities will internally grow vectorized meaningful databases which form the so-called KnowNet. Most importantly, these three mental dualities are the pillars underlying the foundation of artificial self-intelligence which must have the following three basic mental capabilities:

Transformation from sensory signals to concept-physical knowledge (e.g., learning of new meaningful properties, constraints, usages, or behaviors)

Transformation from one type of concept-physical knowledge to another type of concept-physical knowledge (e.g., inference and reasoning)

Transformation from concept-physical knowledge back to motor signals (e.g., planning and control)

5.3. Necessary and Sufficient Conditions of Teachability

In view of the above three mental dualities inside a human-like mind, it is clear to us that a teachable mind must satisfy the following two necessary and sufficient conditions of teachability:

-

Necessary and Sufficient Condition No. 1:

It refers to the innate mental capabilities which transform sensory signals into meaningful crisp data.

-

Necessary and Sufficient Condition No. 2:

It refers to the innate mental capabilities of associating meaningful crisp data with conceptual labels which could be incrementally taught by teachers or trainers.

In literature, tremendous amounts of research works are dedicated to the development of measurement and sensing systems together with data analysis and feature extraction. These intelligent sensory systems enable today’s humanoid robots or many other robots to have the senses of vision, audition, touch, smell, and taste, etc. In other words, the outcomes of these research works allow us to achieve the teachability’s first necessary and sufficient condition.

Surprisingly enough, the RCE neural network as shown in

Figure 5. provides the answer which allows us to achieve the teachability’s second necessary and sufficient condition.

5.4. Blueprint of KnowNet

A human-like teachable mind is a dynamic system which includes both internal processes and internal data. In the previous section, we have highlighted the key details about the internal processes of a human-like teachable mind, which mainly consist of three mental dualities as shown in

Figure 8. Now, the next question will be what the internal data of a human-like teachable mind should be and how they are organized internally.

Before we lay down the key details about the blueprint of KnowNet which stores the organized internal data inside a human-like teachable mind, it is important to remind us about the complexity of the knowledge in the physical world as well as in a conceptual world (i.e., an internalized partial version of the physical world). This statement is witnessed by the fact that a human being normally spends many years to do studies in schools/universities for the purpose of obtaining academic degrees, and that a human being normally spends many years for undertaking experiments and investigations before making impactful discoveries and/or inventions in science and engineering.

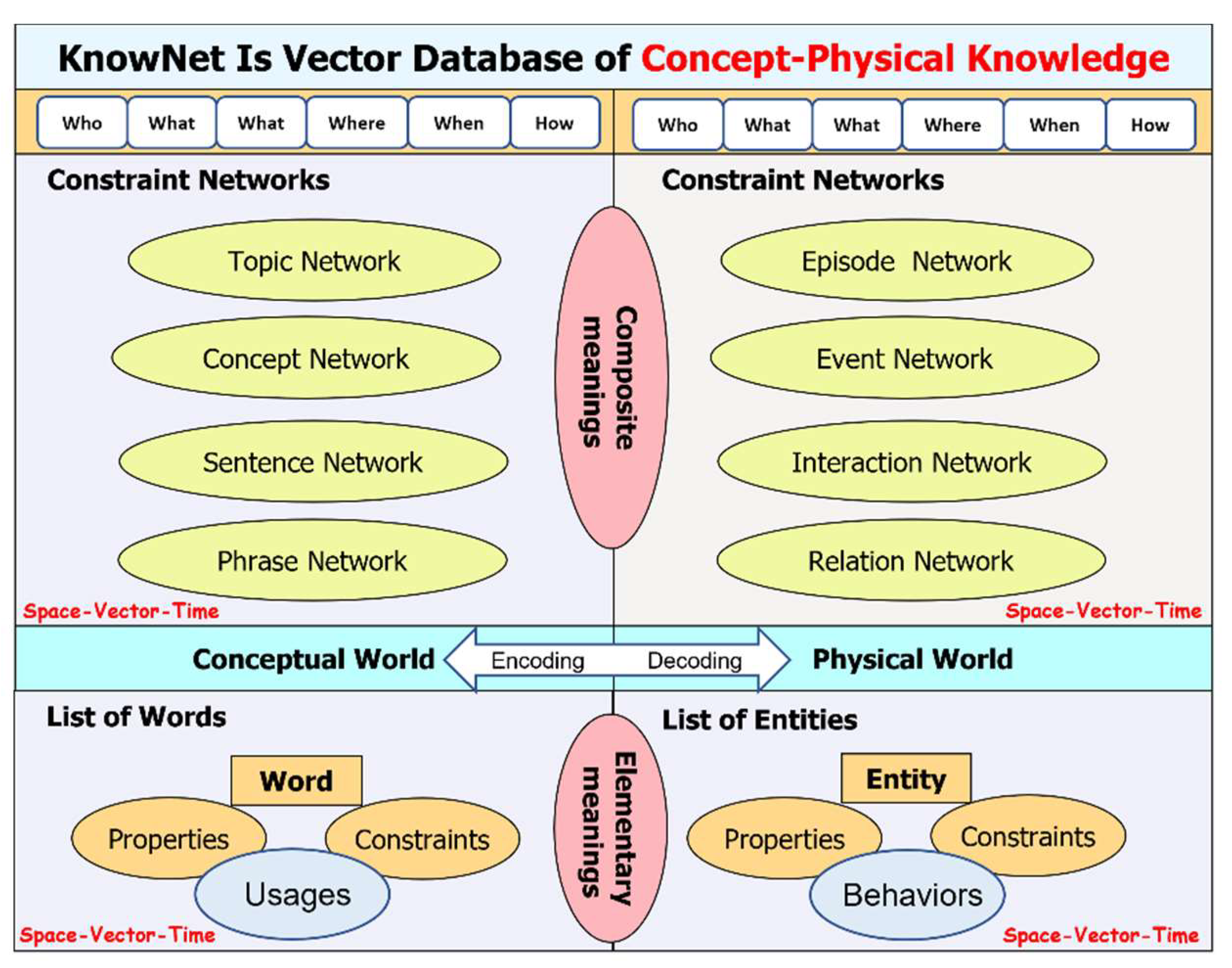

To cope with such complexity of knowledge, we believe that human minds divide the concept-physical knowledge into both elementary meanings and composite meanings as shown in

Figure 9. In this way, it will be easier for our minds to learn and to organize the elementary meanings of the individual entities in the physical world (i.e., the natural objects, the human-made objects and machines, the life-like creatures, etc.) as well as the elementary meanings of the individual words in a conceptual world (e.g., the noun-type words in English) [Jayakumar et al (2010)].

As shown in

Figure 9., the elementary meanings or physical knowledge of the individual entities in the physical world include [Jayakumar et al (2010)]:

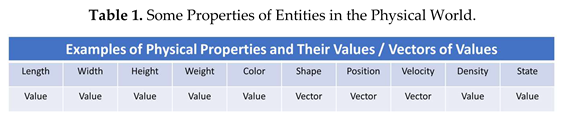

Properties: Each entity may have properties related to physics, chemistry, biology, etc. Hence, each entity has a huge amount of properties in the physical world. It will take time for a humanoid robot to learn these properties in full detail. Table 1 shows some properties that an entity in the physical world may have:

- 2.

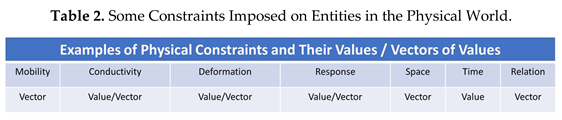

Constraints: In the physical world, an entity may be subject to external constraints which determine the entity’s mobility, deformation, conductivity, existence in space, existence in time, and relationship, etc. Table 2 shows some constraints which may be imposed on an entity in the physical world:

- 3.

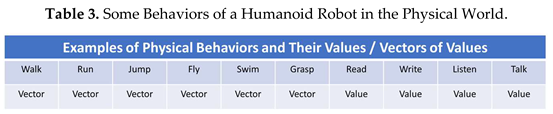

Behaviors: Due to the presence of constraints, an entity such as a system may exhibit dynamic behaviors in the physical world over certain periods of time. Table 3 shows some typical behaviors that a humanoid robot could exhibit in the physical world:

It is important to take note that these elementary meanings or knowledge in terms of properties, constraints, and behaviors are normally described by values or vectors of values. These values are meaningful. As a result, these values are naturally the meaningful numeric representations of corresponding words in a conceptual world.

On our planet Earth, there are more than one thousand natural languages which are very different. However, all of them share the same physical world. This fact opens the door for a humanoid robot to achieve machine translation of multiple languages in parallel. In this paper, our focus is on the top-down design of human-like teachable mind which includes KnowNet. Without loss of generality, we use English as an example to illustrate the elementary meanings in a conceptual world of KnowNet.

As shown in

Figure 9., the elementary meanings or conceptual knowledge of the individual entities (i.e., words in English) include [Jayakumar et al (2010)]:

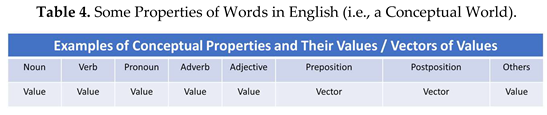

Properties: In English, each word has at least one type such as noun, verb, adjective, adverb, etc. Some words may have more than one type. Table 4 shows some properties of words in English:

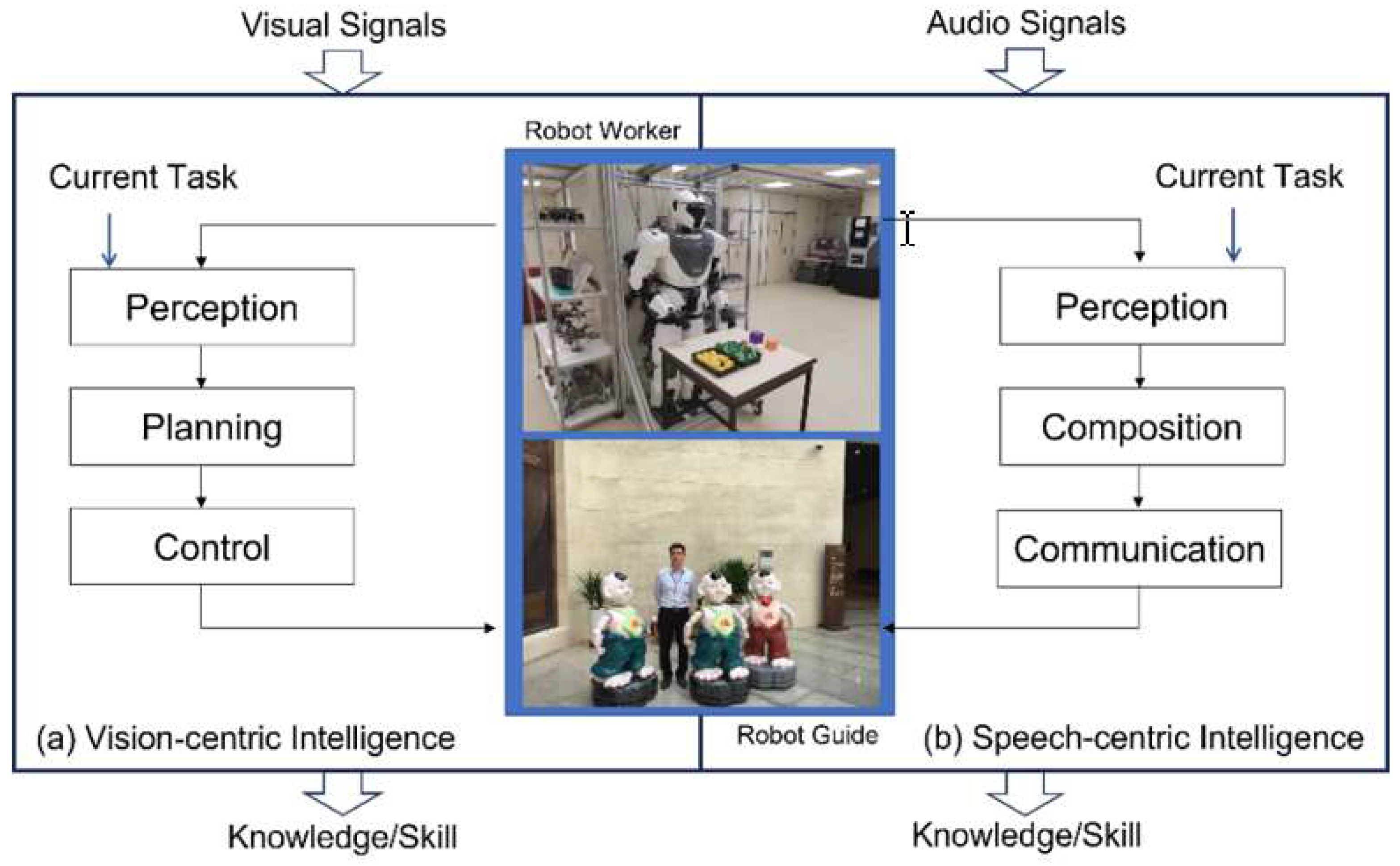

- 2.

Constraints: In English, the typical constraints imposed to words are noun-phase, verb-phase, adjective phase, adverbial phase, conjunction, interjection, etc. These constraints imposed to words also dictate the usages of words in English. One must pay attention to the fact that constraints in English may not be applicable to constraints in other languages such as Chinese. Table 5 shows some typical constrains imposed to words in English.

- 3.

Usages: As mentioned above, the constraints imposed to words also dictate the usage of words. Hence, usages of words in a language depend on constraints imposed on these words. Table 6, which is the same as Table 5, shows some typical usages of words in English.

From the above discussions, it is clear to us that it is possible to attribute meaningful values to words in any natural language. Most importantly, these values allow us to meaningfully determine the similarities or dissimilarities among words, phases, sentences, and texts.

6. Experimental Works

Achieving humanoid robot’s self-intelligence is a big challenge in science and engineering. Any breakthrough in this domain requires huge efforts which are continuously on-going. In this section, we share some unpublished results from research projects which are funded by Future Systems Directorate (now under the name of Future Systems and Technology Directorate), Ministry of Defense, Singapore.

Two of our major projects are highlighted in

Figure 10. As shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 8., the two upmost important signals in the physical world are visual signals and audio signals. Without loss of generality, we do not consider other types of important signals such as signals from touch sensors, signals from smell sensors, and signals from taste sensing. etc. Hence, for a humanoid robot’s mind to be teachable, the first necessary and sufficient condition is the innate capabilities of transforming incoming signals (e.g., visual signals or audio signals) into meaningful crisp data in the physical world.

For the project as shown in

Figure 10(a), if the input signals come from stereo cameras, a teachable humanoid robot must have the innate mental ability to transform the visual signals into feature vectors of values in both time domain and frequency domain [Xie et al (2023)].

Similarly, for the project as shown in

Figure 10(b), a teachable humanoid robot must have the innate mental ability to transform audio signals into feature vectors of meaningful crisp values in both time domain and frequency domain.

6.1. Results of Achieving Vision-centric Intelligence with Real Robot

In

Figure 11, we share one example of unpublished results which demonstrate the teachable mental capabilities of a humanoid robot under the context of autonomously executing a taught task which consists of the following steps:

To receive task description in the form of text such as “pick up a red ball and hand it to a user in front of you”.

To perceive the presence and location of a red ball.

To plan the right arm’s motion.

To control the right arm’s motion so that the right hand is approaching the perceived red ball.

To plan the motion of the right hand’s fingers.

To control the motion of the right hand’s fingers.

To grasp the perceived red ball.

To pick up the perceived red ball.

To hand the red ball over to a user in front the robot.

6.2. Results of Achieving Speech-centric Intelligence with Virtual Robot

In

Figure 12, we share one example of unpublished results which demonstrate the scenario of speech-centric intelligence under the context of deploying humanoid robots to do search and rescue in urban areas. This demonstration shows the following teachable mental capabilities of a humanoid robot:

Transformation of taught texts into understood meanings or knowledge.

Transformation of internally intended meanings or responses into output texts.

Transformation of taught commands in texts into the execution of behaviors.

6.3. Results of Achieving Speech-centric Intelligence with Real Robot

In

Figure 13, we share one example of unpublished results which demonstrate the scenario of speech-centric intelligence under the context of teaching a humanoid robot to undertake certain behaviors such as biped walking. This demonstration shows the following teachable mental capabilities of a humanoid robot:

Transformation of taught texts into understood meanings or knowledge.

Transformation of internally intended responses into output texts.

Transformation of taught commands in texts into the execution of behaviors.

7. Conclusions

First of all, in this paper, we have made the effort to clear the deep confusion about the nature of brain, the nature of mind, the nature of artificial neural network, and the nature of RCE neural network. Then, by adopting the Body-Brain-Mind model for the R&D of a humanoid robot, we have outlined the key details underlying the top-down design of human-like teachable mind and have also stipulated two necessary and sufficient conditions of teachability. Subsequently, we have explained the functionalities of three important dualities inside a human-like mind. They are the duality between cognition and recognition, the duality between encoding and decoding, and the duality between analysis and synthesis. The interplay among these three dualities will enable a human-like mind to fully undertake a pipeline of three transformations such as transformation from sensory signals into knowledge, transformation from one type of knowledge into another type of knowledge, and transformation from knowledge into motor signals. These transformations are the foundation of artificial self-intelligence or AI 3.0. On top of the contribution of revealing the key details of human-like teachable mind, an additional contribution of this paper is to open the horizon for researchers to venture into the R&D of human-like electronic brain or 5th generation digital computers. With the understanding of teachability, the extra benefit from this paper should be the clearance of confusion among machine tuning, machine calibration, and machine learning. Lastly, it is clear to us that more research efforts are expected from more researchers who are willing to venture into this direction of achieving deep impactful outcomes in humanoid robotics and artificial intelligence.

Acknowledgments

The research works presented in this paper have benefited from several research projects funded by Future Systems Directorate (now under the name of Future Systems and Technology Directorate), Ministry of Defense, Singapore. Without these research project grants, it is not possible to achieve the research findings reported in this paper.

References

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; García, S.; Gil-López, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; Chatila, R. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Information fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.L.; 2011. Cognitive science, religion, and theology: From human minds to divine minds. Templeton Press.

- Cambria, E.; White, B. Jumping NLP curves: A review of natural language processing research. IEEE Computational intelligence magazine 2014, 9, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G. (Editor). (2014). Humanoid Robotics and Neuroscience: Science, Engineering and Society. CRC Press.

- Chomsky, N.; Roberts, I.; Watumull, J. The False Promise of ChatGPT. The New York Times 2023, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, E.S.; Hortensius, R.; Wykowska, A. From social brains to social robots: applying neurocognitive insights to human–robot interaction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2019, 374, p20180024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, M.; Ogawa, K. Honda humanoid robots development. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2007, 365, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, E.; Mooney, P. Neuroevolution in deep neural networks: Current trends and future challenges. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2021, 2, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Xu, M.; Ottaviani, C.; Patros, P.; Bahsoon, R.; Shaghaghi, A.; Golec, M.; Stankovski, V.; Wu, H.; Abraham, A.; Singh, M. AI for next generation computing: Emerging trends and future directions. Internet of Things 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Aguirre, D.; Vollert, M.; Asfour, T.; Dillmann, R. Ground-truth uncertainty model of visual depth perception for humanoid robots. In 12th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids 2012) 2012, pp. 436-442.

- Jiao, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yu, F.; Zuo, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, F.; Lin, W.; Shao, L. All-optical logic gate computing for high-speed parallel information processing. Opto-Electronic Science 2022, 1, 220010–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; Krusche, S. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences 2023, 103, p102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, J.D.; Kumar, S. The building blocks of a brain-inspired computer. Applied Physics Reviews 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, K.S.; Xie, M. (2010). Natural Language Understanding by Robots. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing Co.

- Meier, K. Special report: Can we copy the brain? - The brain as computer. IEEE Spectrum 2017, 54, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poibeau, T. (2017). Machine translation. MIT Press.

- Roberts, D.A.; Yaida, S.; Hanin, B. (2022). The principles of deep learning theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Rosenthal, D.M. (Editor). (1991). The nature of mind. Oxford University Press.

- Selva, B.S.; Kanniga, D. R. (2020). A review on word embedding techniques for text classification. Innovative Data Communication Technologies and Application: Proceedings of ICIDCA 2020, 267-281.

- Schmandt, C.; Hulteen, E.A. (1982). The intelligent voice-interactive interface. In Proceedings of the 1982 conference on Human factors in computing systems, pp. 363-366.

- Smythies, J.R. (Editor). (2014). Brain and mind: Modern concepts of the nature of mind. Routledge.

- Spiliotopoulos, D.; Androutsopoulos, I.; Spyropoulos, C.D. (2001). Human-robot interaction based on spoken natural language dialogue. In Proceedings of the European workshop on service and humanoid robots, pp. 25-27.

- Tsagarakis, N.G.; Metta, G.; Sandini, G.; Vernon, D.; Beira, R.; Becchi, F.; Righetti, L.; Santos-Victor, J.; Ijspeert, A.J.; Carrozza, M.C.; Caldwell, D.G. iCub: the design and realization of an open humanoid platform for cognitive and neuroscience research. Advanced Robotics 2007, 21, 1151–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemprala, S.; Bonatti, R.; Bucker, A.; Kapoor, A. ChatGPT for robotics: Design principles and model abilities. Microsoft Autonomous Systems. Robotics Research 2023, 2, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Wächter, M.; Ovchinnikova, E.; Wittenbeck, V.; Kaiser, P.; Szedmak, S.; Mustafa, W.; and Asfour, T. Integrating multi-purpose natural language understanding, robot’s memory, and symbolic planning for task execution in humanoid robots. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2018, 99, pp148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, A.; Henze, B.; Rodriguez, D. A.; Gabaret, J.; Porges, O.; & Roa, M. A. (2016). Multi-contact planning and control for a torque-controlled humanoid robot. In 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), pp. 5708-5715.

- Xie, M. Fundamentals of Robotics: Linking Perception to Action. World Scientific.

- Xie, M.; Chen, H.; Hu, Z.C. (2021). New Foundation of Artificial Intelligence. World Scientific.

- Xie, M.; Lai, T.F.; Fang, Y.H. New Principle Toward Robust Matching in Human-like Stereovision. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Honda, K.; Washizaki, H.; Fukazawa, Y. (2015). Comparative Study on Programmable Robots as Programming Educational Tools. In ACE, pp. 155-164.

- Zimmermann, H.J. (2011). Fuzzy set theory and its applications. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Zhang, J.; Tao, D. Empowering things with intelligence: a survey of the progress, challenges, and opportunities in artificial intelligence of things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 8, 7789–7817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Our R&D projects on the development of humanoid robot with two focuses: a) to achieve vision-centric intelligence and b) to achieve speech-centric intelligence.

Figure 1.

Our R&D projects on the development of humanoid robot with two focuses: a) to achieve vision-centric intelligence and b) to achieve speech-centric intelligence.

Figure 2.

A humanoid robot’s Body-Brain-Mind model in which the study of mind is separated from the study of brain.

Figure 2.

A humanoid robot’s Body-Brain-Mind model in which the study of mind is separated from the study of brain.

Figure 3.

Graphical illustrations of one artificial neural network with a single hidden layer as well as another artificial deep neural network (i.e. a portion of Transformer) with a complex series of hidden layers.

Figure 3.

Graphical illustrations of one artificial neural network with a single hidden layer as well as another artificial deep neural network (i.e. a portion of Transformer) with a complex series of hidden layers.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the working principle behind ChatGPT at a conceptual level.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the working principle behind ChatGPT at a conceptual level.

Figure 5.

Illustration of the working principle behind RCE neural network (i.e., its improved version by us).

Figure 5.

Illustration of the working principle behind RCE neural network (i.e., its improved version by us).

Figure 6.

Evidence which shows that logical gates could be constructed with biological brains’ neurons.

Figure 6.

Evidence which shows that logical gates could be constructed with biological brains’ neurons.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the common ground or foundation between human-like brains and digital computers.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the common ground or foundation between human-like brains and digital computers.

Figure 8.

A proposed blueprint underlying human-like minds in which there are three mental dualities such as: duality between cognition and recognition, duality between encoding and decoding, and duality between analysis and synthesis. The interplay among these three dualities will internally grow vectorized meaningful databases which form the so-called KnowNet.

Figure 8.

A proposed blueprint underlying human-like minds in which there are three mental dualities such as: duality between cognition and recognition, duality between encoding and decoding, and duality between analysis and synthesis. The interplay among these three dualities will internally grow vectorized meaningful databases which form the so-called KnowNet.

Figure 9.

A proposed blueprint for the top-down design of KnowNet in which the concept-physical knowledge are organized into both elementary meanings databases and composite meanings databases.

Figure 9.

A proposed blueprint for the top-down design of KnowNet in which the concept-physical knowledge are organized into both elementary meanings databases and composite meanings databases.

Figure 10.

Two major projects which aim at achieving human-like teachable minds: first one with the objective of achieving vision-centric intelligence and the second one with the goal of achieving speech-centric intelligence.

Figure 10.

Two major projects which aim at achieving human-like teachable minds: first one with the objective of achieving vision-centric intelligence and the second one with the goal of achieving speech-centric intelligence.

Figure 11.

One example of results which show vision-centric intelligence of a humanoid robot under the context of autonomously executing a taught task.

Figure 11.

One example of results which show vision-centric intelligence of a humanoid robot under the context of autonomously executing a taught task.

Figure 12.

One example of results which show speech-centric intelligence of a humanoid robot under the context of doing search and rescue in urban areas, which are taught by human operators with the use of English.

Figure 12.

One example of results which show speech-centric intelligence of a humanoid robot under the context of doing search and rescue in urban areas, which are taught by human operators with the use of English.

Figure 13.

One example of results which show speech-centric intelligence of a humanoid robot under the context of performing some behaviors, which are taught by human operators with the use of English.

Figure 13.

One example of results which show speech-centric intelligence of a humanoid robot under the context of performing some behaviors, which are taught by human operators with the use of English.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).