1. Introduction

Over the past decade, the market for multirotor drones has experienced rapid growth, driven by the popularity of drones for photography and videography, as well as their use in various industries such as agriculture, construction, and surveying [

1]. The employment of exterior-rotor brushless motors within multirotor drones has catalyzed the development of various motor dimensions and configurations. Compared to their interior-rotor counterparts, these motors provide higher torque density [

2,

3,

4], making them attractive for various applications in the field of robotics that are space and weight constrained in design, such as legged robots [

5,

6,

7], prostheses [

8,

9,

10], and exoskeletons [

11,

12,

13]. To effectively harness the benefits of exterior-rotor brushless motors in these applications, it is important to understand their performance characteristics under different operating conditions. Unfortunately, manufacturers of drone motors generally do not provide comprehensive data on the motors’ performance in various conditions beyond drone-specific applications. A few research groups have conducted investigations into the performance of such brushless motors across a range of applications. Lee

et al. [

14] performed an empirical characterization of a widely used exterior-rotor motor (U8 KV100, T-motor, Nanchang, Jiangxi, China) and an accompanying drive (Dephy Actuator Package, Dephy Inc., Maynard, MA, USA) with a focus on wearable robotics applications. In the study, the motor was tested under 36 V and up to 23.8 A peak current (20 seconds). Katz [

15] conducted tests on a motor with similar specifications using a custom 4-quadrant motor dynamometer and a custom drive, with a focus on legged robot applications. The motor was subjected to a voltage of 22 V and peak current of up to 36.99 A. While these studies provide valuable insights into the performance characteristics of the motor, the data were collected in conjunction with the associated custom drives and did not involve direct measurement of the electrical power entering the motor. Furthermore, these studies did not comprehensively explore high-power use cases. For the aforementioned applications, high-power, short-duration operation is often required due to the periodic nature of the loads, such as those encountered during walking, running, or jumping. It is possible to slightly undersize the motor to reduce the system’s weight and size while still achieving accurate peak torque tracking by briefly overpowering it. Manufacturers generally discourage overpowering the motors due to several potential issues, including reduced efficiency and performance caused by torque saturation, and permanent damage to the motors resulting from overheating and demagnetization. Nevertheless, with careful temperature monitoring and proper thermal management, overpowering can be performed safely.

In this study, we conducted an energy efficiency and performance evaluation of the U8Lite KV100 motor, which shares the same specifications as those motors that have demonstrated success in various robotic applications [

6,

7,

9,

16,

17,

18]. The drive system (EVEREST XCR-C, Novanta Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) is a commercially available product that provides high power output. The characterization process involved the direct measurements of the electrical power input to both the drive and motor, as well as the mechanical power output from the motor shaft, including high-power, short-duration operation. Moreover, to obtain a comprehensive evaluation, the corresponding thermal responses of the motor were also recorded throughout the testing. The outcomes of this study are relevant for the selection and design of actuators for a range of robotics applications, especially those demanding high power output for brief duration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Architecture

Figure 1 illustrates the system employed for testing.

Figure 1a presents the overall schematic representation of the system, while

Figure 1b depicts its physical embodiment. Two distinct tests were conducted using switching power supplies rated at 2500 W, operating under 24 V and 36 V. (UHP-2500-24 and UHP-2500-36, MEAN WELL Enterprises Co., Ltd., New Taipei City, Taiwan). The drive system, EVEREST XCR-C motor driver, has a power rating of 3000W and is capable of supporting voltage inputs ranging from 8 to 80 V, with a continuous current of 45 A and a 3-second peak current of 60 A. The driver was tuned to drive the U8Lite KV100 using a 100 kHz PWM switching frequency and a 50 kHz current control loop. The current control loop utilized an internal field-oriented control algorithm. The U8Lite KV100 motor is a delta-winding brushless motor with a weight of 238 g and 21 pole pairs. To facilitate feedback control, an absolute encoder (RM44, RLS Merilna tehnika d.o.o., Slovenia) was installed at the back of the motor. In addition, a temperature sensor (NTC thermistor B57861S0103A039, TDK Electronics AG, Munich, Germany) was directly installed on the stator winding coil using a thermally conductive epoxy (EP42HT-2AO-1 Black, Master Bond Inc., Hackensack, NJ, USA) to measure the thermal response of the motor. For more accurate measurement, the thermistor was connected to a 2.5 kOhm reference resistor (USR2G-2K5X1, Riedon, Alhambra, CA, USA) to form a half bridge circuit. To maintain a consistent starting temperature of 25°C and facilitate cooling, a fan was positioned adjacent to the motor. The fan operation was controlled based on readings from the temperature sensor. To monitor the DC voltage and current entering the motor driver, a differential voltage divider (Entube DE, Verivolt, San Francisco, CA, USA) and a zero-flux current sensor (IsoBlock I-ZF, Verivolt, San Francisco, CA, USA) were used. The voltage sensor has a measuring range of ±100 V with an 85 kHz bandwidth and ±0.05% accuracy, while the current sensor has a measuring range of ±100 A with an 100 kHz bandwidth and ±0.02% accuracy. Both the voltage and current sensors produce an output of ±10V, a value that aligns with the input requirements of a typical data acquisition (DAQ) device. To measure the line currents entering the motor, the same current sensors were utilized, while the line voltages were measured using a 3-channel differential voltage down-converter specifically designed for 3-phase systems (Entube TE, Verivolt, San Francisco, CA, USA). The Entube TE has the same measuring range, bandwidth, accuracy, and output as Entube DE. The output torque and speed of the motor were measured using a rotary torque sensor with integrated encoder (TRS705 FSH02564, Futek, Irvine, CA, USA). The torque sensor has a sensing range of ±5 Nm and a nonlinearity of ±0.2%. It was calibrated by the manufacturer prior to shipping. The driving motor (CPM-MCVC-D1003A-RLN, Teknics Industries, Inc., Lincoln Park, NJ, USA ) is an integrated 3-phase servo motor that operated under 208 V AC and has a power rating of 4 hp (2982.8 W). It has a continuous torque of 13.4 Nm, a peak torque of 32.9 Nm, and a maximum speed of 2760 RPM.

Data from the voltage and current sensors were acquired using two analog input modules (NI 9215, Austin, TX, USA) at 40,000 samples/second, while the data from the thermistor were collected via a different analog input module (NI 9219, Austin, TX, USA) at 100 samples/second. This module has built-in voltage and current excitation and supports half-bridge inputs. A digital output module (NI 9401, Austin, TX, USA) was used to control the 3-phase servo motor. All these input and output modules were installed within a chassis (NI cDAQ-9178), which interfaced with a host computer via USB. Data from the torque sensor were collected at 100 samples/second and processed utilizing an separate DAQ system (USB 520, Futek, Irvine, CA, USA), which was also connected to the computer via USB. The configuration used for measuring both electrical power and temperature is represented in

Figure 2, which provide a detailed depiction of the setup, offering a close-up view that allows for a comprehensive understanding of the measurement apparatus.

2.2. Efficiency and Loss Mapping Procedure

The experimental procedure involved a systematic exploration of the entire torque-speed plane through the establishment of a mesh of reference operating points, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The figure represents the operating points utilized during testing under 24 V conditions. The speed range spanned from 0 to 1500 RPM (1700 RPM for the 36 V test) and was divided into equally spaced intervals of 100 RPM. This interval selection ensured an adequate resolution. Similarly, for each speed value, the torque, corresponding to the commanded current A, was adjusted from 0 to 50 A in increments of 5 A. These increments were also chosen to achieve an appropriate resolution. To further enhance resolution, additional points of 2 A and 4 A were included for each speed value in both the 24 V and 36 V tests. Note that in this setup, the driving motor was regulated based on speed and sets the desired speed for a specific operating point. On the other hand, the U8Lite KV100 motor was current controlled.

For each operating point, the driving motor would first start for one second to ensure it reached the target speed, and then the U8 KV100 motor would begin applying torque. The tests were conducted for a duration of 3.5 seconds. After the 3.5-second interval, both motors were stopped, but the DAQ continued to collect temperature readings for an additional 15 seconds. Subsequently, the fan was activated to cool the motor until its temperature dropped below 25°C before commencing the next operating point. During data processing, the initial and final 20% of the data were trimmed, and the remaining portion was utilized for calculations. To calculate the motor’s input electrical power, the following equation was used [

19]:

where

,

, and

represent the measured line currents, and

,

, and

represent the measured line voltages.

represents the phase difference between

with respect to

,

represents the phase difference between

with respect to

, and

represents the phase difference between

with respect to

. The DC power entering the drive was calculated using the following equation:

where

and

represent the root mean square (RMS) values of the DC voltage and current, respectively, coming out of the power supply. The RMS values of

and

were used due to motor’s behavior at certain high-speed operating points. At these points, the motor essentially operates as a generator with negligible torque output, as opposed to its typical function as a torque generator. As a result, AC currents were measured, necessitating the utilization of RMS values. The output mechanical power from the U8Lite KV100 motor was calculated as:

where

is the measured torque and the

is the measured speed. Using these power values, the motor efficiency

can be determined as:

Similarly, the motor driver efficiency

can be calculated as:

Furthermore, the power loss of the motor

can be determined by subtracting the output mechanical power

from the input electrical power

:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Motor Efficiency and Loss Maps

The procedure outlined above was executed using 24 V and 36 V power supplies. However, during the 36 V test, the motor could not complete the test at 1700 RPM with current setpoints of 45 A and 50 A due to the triggering of the protection. At these two operating points, the current controller would briefly overshoot beyond 60 A, which is the absolute maximum for the drive. While the motor managed to operate for 3 seconds at these operating points, it failed to maintain the necessary duration of 3.5 seconds, as prescribed by this study.

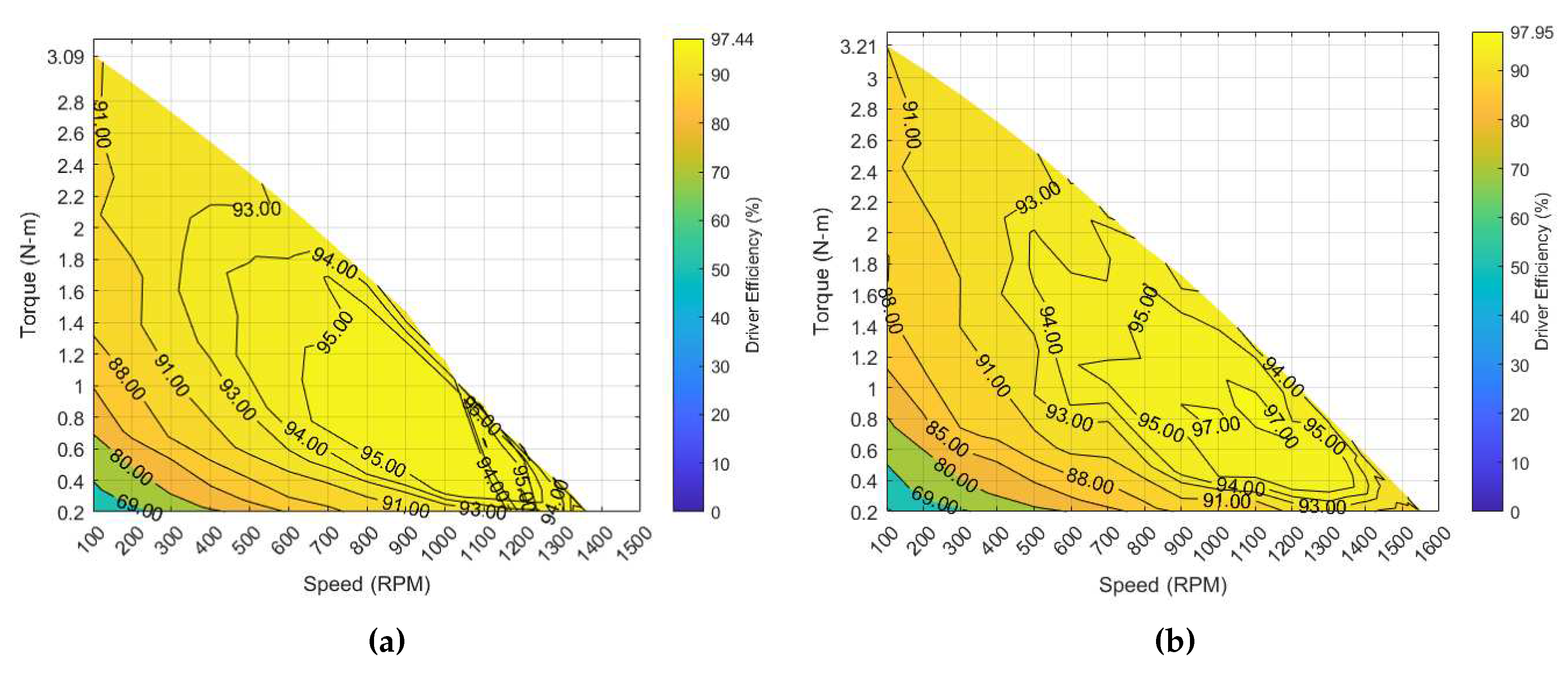

Figure 4 illustrates the motor efficiency and loss maps for the two voltage conditions. These maps play a crucial role in assessing the motor’s efficiency across the entire torque-speed range, providing insights into its performance characteristics. For instance, in mobile applications, operating the motor within the high-efficiency region is highly desirable to optimize battery usage. From the results depicted in

Figure 4, this region is observed to span speeds ranging from 200 RPM to 700 RPM, with torque values below 1 Nm. Furthermore, these efficiency maps can also provide information on how to momentarily exceed the motor’s power rating and ascertain the torque and speed limits that the motor can attain.

The loss maps provide information about the power dissipation in the motor at different operating points. However, it is important to note that the loss maps for the motor do not include the zero current and zero velocity operating points. These operating points were excluded because, at zero speed, the motor does not produce any output mechanical power, and at zero current, the motor does not apply any torque. Therefore, including these points in the loss maps would not provide meaningful information about power dissipation. Nonetheless, the data from these points were included in the motor efficiency maps to provide a comprehensive view of the motor’s performance, including its maximum torque and speed capabilities. Further, under the 24 V condition, there are certain operating points, particularly at 1200 RPM and above, where the motor was unable to generate any positive torque. As a result, all the electrical power input was considered as loss, resulting in an irregular pattern in the loss map depicted in

Figure 4b at high speeds.

From

Figure 4, it is evident that operating the U8Lite Kv100 motor at 36 V yields improved performance compared to 24 V. When comparing the efficiency maps between the 24 V and 36 V conditions, it can be observed that the torque outputs are approximately 5% to 10% higher for speeds up to 600 RPM and 10% to 25% higher for speeds above 600 RPM. This indicates that the motor can generate higher levels of torque at higher operating voltages. Notably, under the 36 V condition, the motor exhibits the capability to generate torque even at higher speeds.

Table 1 provides a more detailed comparison of the increase in torque generated by the motor at 36 V compared to 24 V. In addition to higher torque generation, the motor also exhibits higher efficiency under the 36 V condition. Furthermore, the area of the high-efficiency region is larger when operating the motor at 36 V.

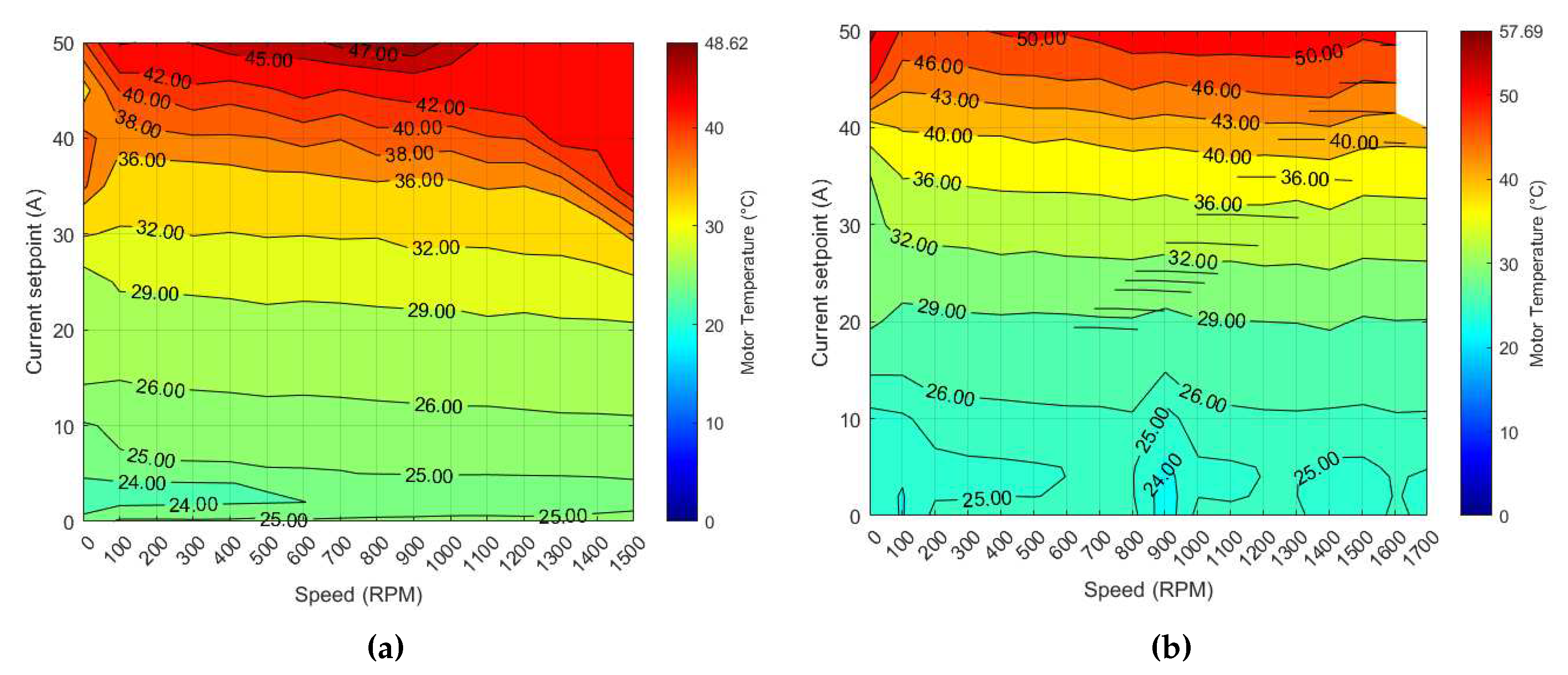

3.2. Motor Driver Efficiency Maps

Because the primary focus of this study is to evaluate the motor’s performance, it was crucial to ensure that the motor driver does not impede the motor’s capabilities. To mitigate this, the driver was affixed to an aluminum plate, and a low-profile CPU cooler (C7 Cu, Cryorig, New Taipei City, Taiwan) was mounted on the plate. However, it is important to acknowledge that this thermal management solution may not be feasible for mobile applications due to weight and size considerations. Therefore, for mobile applications, it is recommended to conduct further tests to assess the thermal properties of the motor drive under various cooling methods.

Figure 5 presents the efficiency maps for the EVEREST XCR-C motor driver at the two voltage conditions. The results obtained align with the energy efficiency specifications provided by the vendor [

20]. The driver efficiency maps do not incorporate the zero current and zero velocity operating points for the same reason as the loss maps.

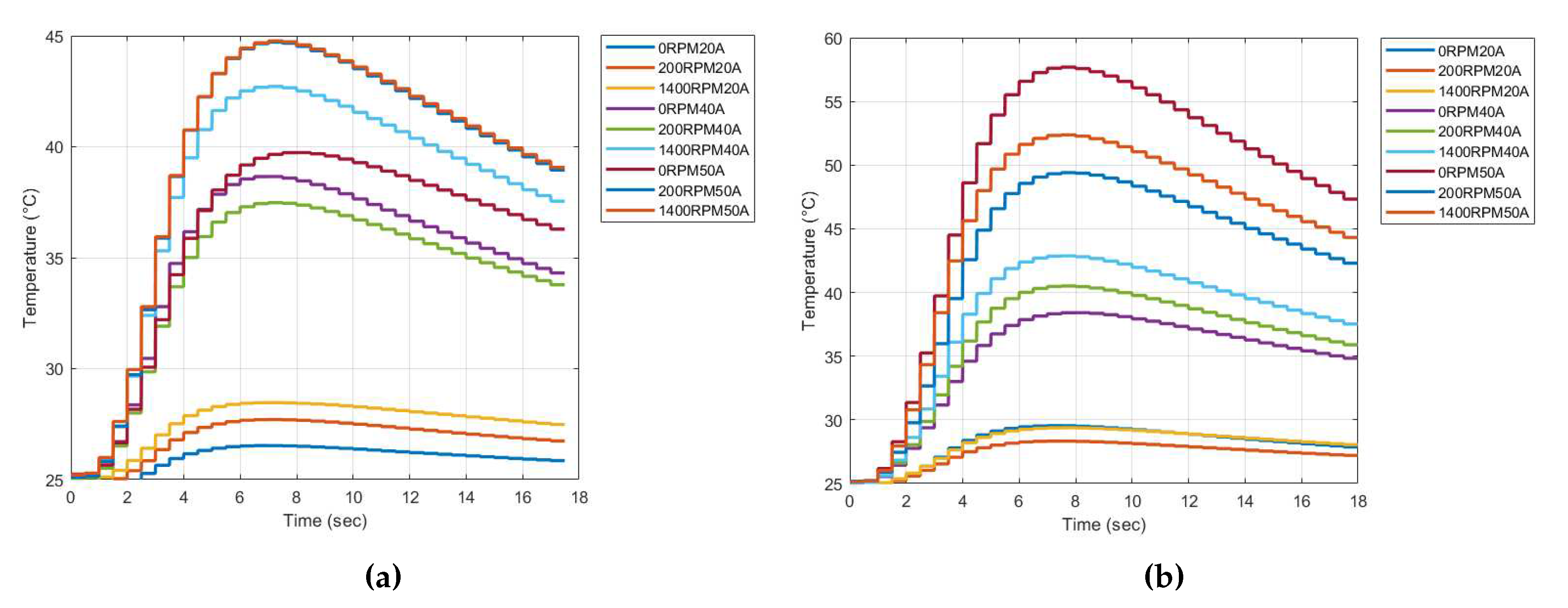

3.3. Motor Thermal Responses

Joule heating within the motor’s windings significantly impacts the motor’s performance. This thermal effect, caused by the resistance of the windings to the electric current, can lead to increased temperatures, potentially affecting the efficiency and longevity of the motor. Therefore, monitoring the temperature of the windings is crucial to ensure the motor is operated within safe limits when overpowering it. As mentioned earlier, during the tests at each operating point, the motor did not receive any active cooling and was only cooled after the test was completed. It is important to note that the motor should not exceed a temperature of 95°C at any point during operation.

Figure 6 illustrates the maximum temperature reached by the motor under both the 24 V and 36 V operating conditions.

These data provide assurance that briefly exceeding the motor’s power rating for a limited duration is acceptable within the specified thermal limits. Furthermore,

Figure 7 displays the thermal responses of selected operating points, providing additional insights into the temperature behavior of the motor.

Upon comprehensive analysis of thermal behavior, it becomes clear that the introduction of a higher voltage triggers a more accelerated rise in temperature, culminating in greater peak temperatures. Nonetheless, throughout the span of the 3.5-second test interval, this amplified temperature did not significantly affect the efficiency of the motor. Under the 36 V condition, the temperature peaked at approximately 57°C when operating at high current setpoints, which remains comfortably below the specified limit of 95°C.

In real-world applications where the motor might need to be momentarily overpowered, it is crucial to continuously monitor the temperature. The motor drive incorporates an protection system, which acts as a safety measure against situations where the instantaneous thermal energy surpasses a predetermined limit. This is vital as temperature sensors may not be quick enough to identify potentially hazardous conditions.

The instantaneous energy that the motor releases is directly proportional to the square of the current flowing through it and the time this current persists. The "nominal current" is defined as the maximum current that a motor can sustain continuously without breaching its thermal boundaries. Any current that goes beyond this nominal value results in an accumulation of thermal energy within the motor and its surroundings, which then needs to be dissipated by the cooling system.

If the thermal energy buildup exceeds the cooling system’s dissipation capacity, the system could reach its thermal limits, posing a risk of irreversible damage to the motor or the drive. The

principle is associated with a value that is inversely proportional to the energy that the motor dissipates. The

protection system serves as a control mechanism to ensure that the total power that the motor releases as thermal energy does not go beyond its thermal constraints. [

21].

4. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive experimental analysis of the performance characteristics of the U8 KV100 motor under different operating conditions. The motor’s efficiency, power loss, driver efficiency, and thermal responses were thoroughly examined under two voltage conditions, 24 V and 36 V.

The results reveal that the motor demonstrates enhanced performance when operated at 36 V, producing higher torque outputs and efficiency compared to the 24 V condition. The efficiency maps generated in this study offer insights into the motor’s performance across the entire torque-speed range, which can be crucial in optimizing battery usage in mobile applications. However, in practical scenarios, a 36 V battery of the same capacity as a 24 V one would be larger and heavier, which may not be ideal for certain mobile applications. Although a smaller capacity battery can be used to mitigate the size and weight issues, the performance boost may not sufficiently compensate for the reduced capacity. Therefore, a careful balance between performance enhancement and battery capacity must be considered for optimal results.

The thermal responses of the motor were also closely monitored, with the results indicating that the motor can safely operate beyond its power rating for brief periods, provided the temperature does not exceed the specified limit of 95°C. The introduction of a higher voltage resulted in a more accelerated rise in temperature, but this did not significantly affect the motor’s efficiency during the test interval.

The study also highlighted the importance of the protection scheme integrated into the motor drive. This mechanism ensures that the integral of power released by the motor as thermal energy does not exceed its thermal limits, thereby preventing potential damage to the motor or the drive.

In light of these findings, it is recommended that further tests be conducted to assess the thermal properties of the motor drive under various cooling methods, particularly for mobile applications where weight and size considerations may limit the feasibility of certain thermal management solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H. and H.H.; methodology, T.H. S.Y. and H.H.; software, T.H.; validation, T.H.; formal analysis, T.H.; data curation, T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H.; writing—review and editing, T.H. and H.H.; visualization, T.H.; supervision, H.H.; project administration, H.H.; funding acquisition, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The MIT K. Lisa Yang Center for Bionics and MIT Media Lab Consortia.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Multirotor Drone Market - Report Overview. Available online: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/multirotor-drone-market-A09185 (accessed on 04/18/2023).

- Kenneally, G., De, A., and Koditschek, D. E. Design principles for a family of direct-drive legged robots. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 2016, 1(2), 900-907. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T., Nussbaumer, T., and Kolar, J.W. Torque scaling laws for interior and exterior rotor permanent magnet machines. IEEE International Magnetics Conference, 2009, 3, 4-7.

- Lee, J.J., Kim, W.H., Yu, J.S., Yun, S.Y., Kim, S.M., Lee, J.J., and Lee, J. Comparison between concentrated and distributed winding in IPMSM for traction application. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems, 2010, 1172-1174.

- Brill, A. L., De, A., Johnson, A. M., and Koditschek, D. E. Tail-assisted rigid and compliant legged leaping. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 2015, pp. 6304-6311.

- Katz, B., Carlo, J.D., and Kim, S. Mini cheetah: A platform for pushing the limits of dynamic quadruped control. In 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2019, 6295-6301.

- Kalouche, S. GOAT: A legged robot with 3D agility and virtual compliance. In 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017, 4110-4117.

- Carney, M.E., Shu, T., Stolyarov, R., Duval, J.-F., and Herr, H.M. Design and Preliminary Results of a Reaction Force Series Elastic Actuator for Bionic Knee and Ankle Prostheses. IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics, 2021, 3(3), 542-553. [CrossRef]

- Azocar, A. F., Mooney, L. M., Duval, J. F., Simon, A. M., Hargrove, L. J., and Rouse, E. J. Design and clinical implementation of an open-source bionic leg. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 2020, 4, 1-13.

- Zhu, J., Jiao, C., Dominguez, I., Yu, S., and Su, H. Design and Backdrivability Modeling of a Portable High Torque Robotic Knee Prosthesis With Intrinsic Compliance for Agile Activities. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 2022, 27(4), 1837-1845. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S., Huang, T.-H., Yang, X., Jiao, C., Yang, J., Chen, Y., Yi, J., and Su, H. Quasi-Direct Drive Actuation for a Lightweight Hip Exoskeleton With High Backdrivability and High Bandwidth. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 2020, 25(4), 1794-1802. [CrossRef]

- Nesler, C., Thomas, G., Divekar, N., Rouse, E.J. and Gregg, R.D. Enhancing Voluntary Motion With Modular, Backdrivable, Powered Hip and Knee Orthoses. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7(3), pp.6155-6162. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-H.; Zhang, S.; Yu, S.; MacLean, M.K.; Zhu, J.; Di Lallo, A.; Jiao, C.; Bulea, T.C.; Zheng, M.; Su, H. Modeling and Stiffness-Based Continuous Torque Control of Lightweight Quasi-Direct-Drive Knee Exoskeletons for Versatile Walking Assistance. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2022, 38, 1442–1459. [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.H.; Pan, C.-W.; Rouse, E.J. Empirical Characterization of a High-performance Exterior-rotor Type Brushless DC Motor and Drive. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 4-8 November 2019; 8018-8025.

- Katz, G. B., A low cost modular actuator for dynamic robots. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018.

- Hsieh, T. H., Design and control of a Two-Degree-of-Freedom powered ankle-foot prosthesis. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019.

- Nesler, C.; Thomas, G.; Divekar, N.; Rouse, E.J.; Gregg, R.D. Enhancing Voluntary Motion With Modular, Backdrivable, Powered Hip and Knee Orthoses. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 6155–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, I.; Peterson, R.R.; Herrin, K.R.; Mazumdar, A.; Young, A.J. Design and Validation of a Torque-Controllable Series Elastic Actuator-Based Hip Exoskeleton for Dynamic Locomotion. J. Mechanisms Robotics 2023, 15, 021007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, J. E. Three-Phase Electrical Power, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 182–184. [Google Scholar]

- Everest XCR Product Description. Available online: https://drives.novantamotion.com/eve-xcr/ product-description (accessed on 02/08/2023).

- Drive protections. Available online: https://drives.novantamotion.com/denxcr/drive-protections (accessed on 05/18/2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).