Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

21 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

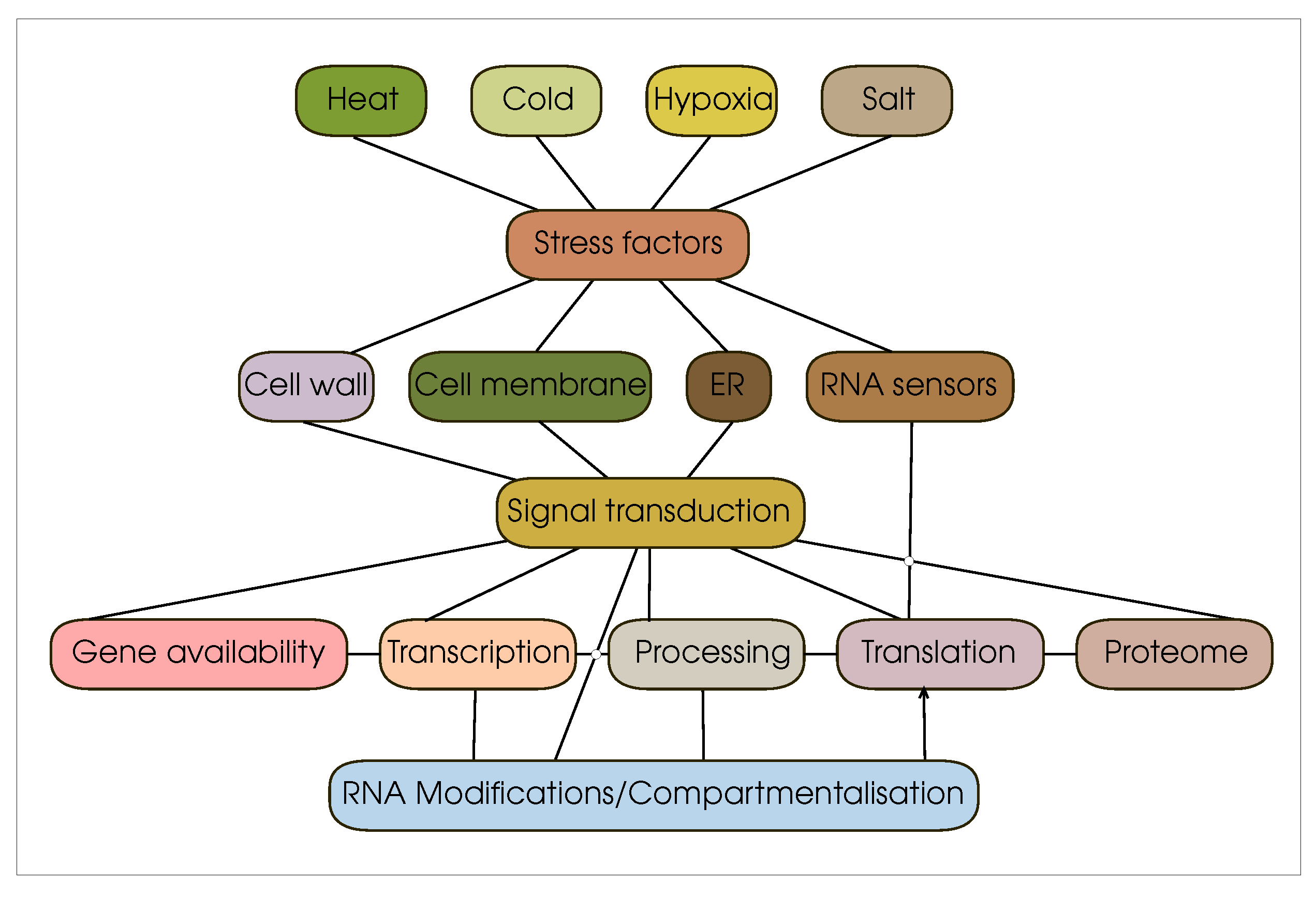

2. Regulation of plant translation under stress conditions

2.1. Signaling pathways

2.2. Translation factors are a necessary part of translation

2.3. Protein thermosensors

2.4. RNA binding proteins

2.5. MicroRNAs

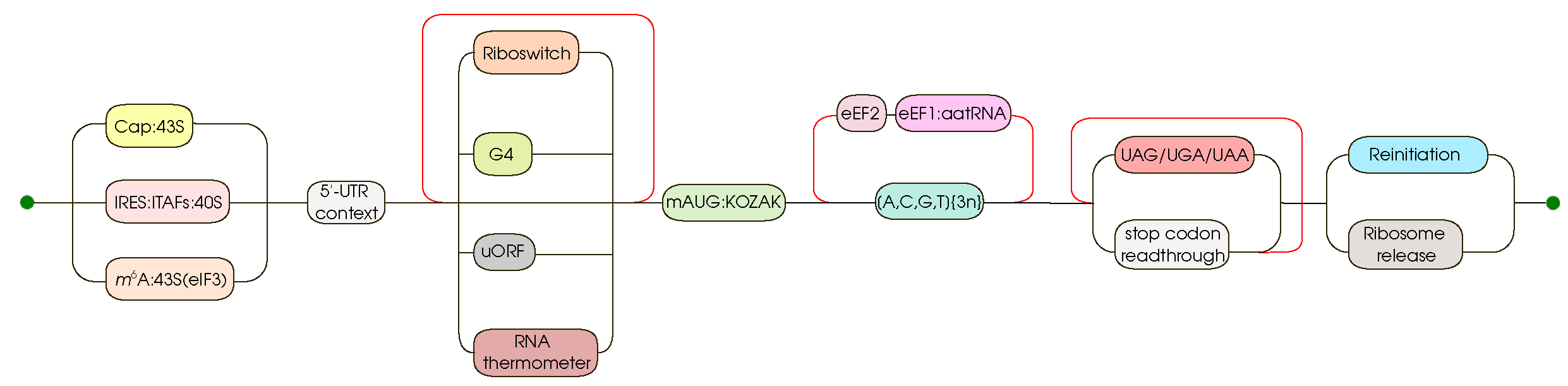

2.6. 5’-Untranslated regions’ unstructured features

2.7. lncRNA

2.8. IRES

2.9. Leaderless mRNAs

2.10. uORFs

2.11. Riboswitches

2.12. RNA thermometers

2.13. Plant ribosomes also act as an independent sensor

2.14. G-quadruplexes

2.15. Kozak consensus sequence

2.16. Codon usage

2.17. Global changes in plant mRNA structure under abiotic stress

3. Methods for studying translation in plants

3.1. Analysis of the involvement of mRNA in the translation process

3.2. Examination of mRNA secondary structure

- For analysis under in vivo conditions, chemical modification of bases should be preferred since large molecules of RNases and proteases may have significant problems crossing the plasmalemma and, in the case of plants, the cell wall.

-

Reagents used to modify unbound bases must not be toxic.

- −

- For example, dimethyl sulphate (DMS) [193], selectively methylating adenines and cytosines as part of single-stranded RNA regions; or N-cyclohexyl- N’-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide metho-p-toluenesulfonate (CMCT), which forms adducts with N1 and N3 of pseudouridine, N3 of uridine, and N1 of guanosine and inosine, as well as a combination of these two methods [194].

- −

- A separate method is icSHAPE [195], the essence of which is to modify free (single-stranded) RNA bases of all 4 types.

- −

- A similar approach is SHAPE-MaP [196]

- When analysing the temperature modulation of translation, one should take into account the increase in reactivity of modifying reagents and carry out the appropriate normalisation of the obtained data.

-

To eliminate the ambiguity arising from the protection of bases by RNA-bound proteins, it is necessary to apply approaches based on selective combinatorial degradation:

- −

- double-stranded RNA

- −

- single-stranded RNA

- −

- proteins that protect the backbone of the RNA molecule

3.3. In silico mRNA structure prediction

4. Concluding remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Czékus, Z.; Csíkos, O.; Ördög, A.; Tari, I.; Poór, P. Effects of Jasmonic Acid in ER Stress and Unfolded Protein Response in Tomato Plants. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czékus, Z.; Szalai, G.; Tari, I.; Khan, M.I.R.; Poór, P. Role of ethylene in ER stress and the unfolded protein response in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2022, 181, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Je, S.; Lee, Y.; Yamaoka, Y. Effect of Common ER Stress–Inducing Drugs on the Growth and Lipid Phenotypes of Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis. Plant and Cell Physiology 2023, 64, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.Y.; Kanehara, K. The Unfolded Protein Response Modulates a Phosphoinositide-Binding Protein through the IRE1-bZIP60 Pathway. Plant Physiology 2020, 183, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raxwal, V.K.; Ghosh, S.; Singh, S.; Katiyar-Agarwal, S.; Goel, S.; Jagannath, A.; Kumar, A.; Scaria, V.; Agarwal, M. Abiotic stress-mediated modulation of the chromatin landscape in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 71, 5280–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, C.; Hu, G.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Gu, X. Reorganization of the 3D chromatin architecture of rice genomes during heat stress. BMC Biology 2021, 19, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Jing, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Xue, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, D.; He, H.; Qian, W. Heat stress-induced transposon activation correlates with 3D chromatin organization rearrangement in Arabidopsis. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selma, S.; Orzáez, D. Perspectives for epigenetic editing in crops. Transgenic Research 2021, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kaur, S.; Seem, K.; Kumar, S.; Mohapatra, T. Understanding 3D Genome Organization and Its Effect on Transcriptional Gene Regulation Under Environmental Stress in Plant: A Chromatin Perspective. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Vazquez, R.; Desvoyes, B.; Gutierrez, C. Histone variants and modifications during abiotic stress response. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.B.; Sullivan, S.; Nimmo, H.G. Global spatial analysis of Arabidopsis natural variants implicates 5’UTR splicing of LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL in responses to temperature. Plant, Cell and Environment 2018, 41, 1524–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorban, A.N.; Harel-Bellan, A.; Morozova, N.; Zinovyev, A. Basic, simple and extendable kinetic model of protein synthesis. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 2019, 16, 6602–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muench, D.G.; Zhang, C.; Dahodwala, M. Control of cytoplasmic translation in plants. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 2012, 3, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokdarshi, A.; Morgan, P.W.; Franks, M.; Emert, Z.; Emanuel, C.; von Arnim, A.G. Light-Dependent Activation of the GCN2 Kinase Under Cold and Salt Stress Is Mediated by the Photosynthetic Status of the Chloroplast. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kørner, C.; Du, X.; Vollmer, M.; Pajerowska-Mukhtar, K. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling in Plant Immunity—At the Crossroad of Life and Death. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2015, 16, 26582–26598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Afrin, T.; Pajerowska-Mukhtar, K.M. Arabidopsis GCN2 kinase contributes to ABA homeostasis and stomatal immunity. Communications Biology 2019, 2, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokdarshi, A.; von Arnim, A.G.; Akuoko, T.K. Modulation of GCN2 activity under excess light stress by osmoprotectants and amino acids. Plant Signaling and Behavior 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Im, J.H.; Song, G.; Park, S.R. SNF1-Related Protein Kinase 1 Activity Represses the Canonical Translational Machinery. Plants 2022, 11, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, R.M.; Browning, K.S. The eIF4F and eIFiso4F Complexes of Plants: An Evolutionary Perspective. Comparative and Functional Genomics 2012, 2012, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lu, M.J.; Shih, M. The Sn RK 1- eIF iso4G1 signaling relay regulates the translation of specific mRNA s in Arabidopsis under submergence. New Phytologist 2019, 222, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D.R.; Le, H.; Caldwell, C.; Tanguay, R.L.; Hoang, N.X.; Browning, K.S. The Phosphorylation State of Translation Initiation Factors Is Regulated Developmentally and following Heat Shock in Wheat. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuteja, N.; Vashisht, A.A.; Tuteja, R. Translation initiation factor 4A: a prototype member of dead-box protein family. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2008, 14, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toribio, R.; Muñoz, A.; Castro-Sanz, A.B.; Merchante, C.; Castellano, M.M. A novel eIF4E-interacting protein that forms non-canonical translation initiation complexes. Nature Plants 2019, 5, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.L.; Hong, S.K. Sensitivity of Translation Initiation Factor eIF1 as a Molecular Target of Salt Toxicity to Sodic-Alkaline Stress in the Halophytic Grass Leymus chinensis. Biochemical Genetics 2013, 51, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Gao, C. The Translation Initiation Factor 1A (TheIF1A) from Tamarix hispida Is Regulated by a Dof Transcription Factor and Increased Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, Y.; des Georges, A.; Dhote, V.; Langlois, R.; Liao, H.Y.; Grassucci, R.A.; Hellen, C.U.; Pestova, T.V.; Frank, J. Structure of the Mammalian Ribosomal 43S Preinitiation Complex Bound to the Scanning Factor DHX29. Cell 2013, 153, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Gaikwad, K.; Kou, X.; Wang, F.; Tian, X.; Xin, M.; Ni, Z.; Sun, Q.; Peng, H.; Vierling, E. Mutations in eIF5B Confer Thermosensitive and Pleiotropic Phenotypes via Translation Defects in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1952–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorsch, J.R.; Dever, T.E. Molecular View of 43 S Complex Formation and Start Site Selection in Eukaryotic Translation Initiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 21203–21207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Maroco, J.P.; Pereira, J.S. Understanding plant responses to drought — from genes to the whole plant. Functional Plant Biology 2003, 30, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Jain, M.; Kulshreshtha, R.; Khurana, J.P.; Kumar, S.; Singh, P. Expression analysis of genes encoding translation initiation factor 3 subunit g (TaeIF3g) and vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein (TaVAP) in drought tolerant and susceptible cultivars of wheat. Plant Science 2007, 173, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, A.A.; Jankowsky, E. DEAD-box helicases as integrators of RNA, nucleotide and protein binding. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2013, 1829, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, V.; Parihar, V.; Malik, G.; Kalra, V.; Kapoor, S.; Kapoor, M. The DEAD-box RNA helicase eIF4A regulates plant development and interacts with the hnRNP LIF2L1 in Physcomitrella patens. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2020, 295, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Mudgil, Y.; Pandey, S.; Fartyal, D.; Reddy, M.K. Structural modelling and phylogenetic analyses of PgeIF4A2 (Eukaryotic translation initiation factor) from Pennisetum glaucum reveal signature motifs with a role in stress tolerance and development. Bioinformation 2016, 12, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boex-Fontvieille, E.; Daventure, M.; Jossier, M.; Zivy, M.; Hodges, M.; Tcherkez, G. Photosynthetic Control of Arabidopsis Leaf Cytoplasmic Translation Initiation by Protein Phosphorylation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guihur, A.; Rebeaud, M.E.; Goloubinoff, P. How do plants feel the heat and survive? Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2022, 47, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merret, R.; Carpentier, M.C.; Favory, J.J.; Picart, C.; Descombin, J.; Bousquet-Antonelli, C.; Tillard, P.; Lejay, L.; Deragon, J.M.; yung Charng, Y. Heat Shock Protein HSP101 Affects the Release of Ribosomal Protein mRNAs for Recovery after Heat Shock. Plant Physiology 2017, 174, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, F.; Basha, E.; Fowler, M.E.; Kim, M.; Bordowitz, J.; Katiyar-Agarwal, S.; Vierling, E. Class I and II small heat-shock proteins protect protein translation factors during heat stress. Plant Physiology, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, R.W.; Parker, R. Coupling of Ribostasis and Proteostasis: Hsp70 Proteins in mRNA Metabolism. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2015, 40, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuramalingam, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Mahalingam, R. Interacting protein partners of Arabidopsis RNA-binding protein AtRBP45b. Plant Biology 2017, 19, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Tsuda, K.; Joe, A.; Sato, M.; Nguyen, L.V.; Glazebrook, J.; Alfano, J.R.; Cohen, J.D.; Katagiri, F. A Putative RNA-Binding Protein Positively Regulates Salicylic Acid–Mediated Immunity in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2010, 23, 1573–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbudak, M.A.; Yildiz, S.; Filiz, E. Pathogenesis related protein-1 (PR-1) genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.): Bioinformatics analyses and expression profiles in response to drought stress. Genomics 2020, 112, 4089–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.S.; Nam, H.G.; Chen, Y.R. A salt-regulated peptide derived from the CAP superfamily protein negatively regulates salt-stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 2015, 66, 5301–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, P. A role for SR proteins in plant stress responses. Plant Signaling and Behavior 2011, 6, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laloum, T.; Martín, G.; Duque, P. Alternative Splicing Control of Abiotic Stress Responses. Trends in Plant Science 2018, 23, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Du, B.; Liu, D.; Qi, X. Splicing factor SR34b mutation reduces cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis by regulating iron-regulated transporter 1 gene. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2014, 455, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Cui, P.; Chen, H.; Ali, S.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, L. A KH-Domain RNA-Binding Protein Interacts with FIERY2/CTD Phosphatase-Like 1 and Splicing Factors and Is Important for Pre-mRNA Splicing in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genetics 2013, 9, e1003875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Luthe, D.S. Heat Sensitivity in a Bentgrass Variant. Failure to Accumulate a Chloroplast Heat Shock Protein Isoform Implicated in Heat Tolerance. Plant Physiology 2003, 133, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Montagu, M.V.; Verbruggen, N. Small heat shock proteins and stress tolerance in plants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression 2002, 1577, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Nie, J.; Wang, H. MicroRNA biogenesis in plant. Plant Growth Regulation 2021, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- oki Iwakawa, H.; Tomari, Y. Molecular Insights into microRNA-Mediated Translational Repression in Plants. Molecular Cell 2013, 52, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkar, R.; Zhu, J.K. Novel and Stress-Regulated MicroRNAs and Other Small RNAs from Arabidopsis[W]. The Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2001–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S. The role of the activated macrophage in clearing Listeria monocytogenes infection. Frontiers in Bioscience 2007, 12, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ge, L.; Liang, R.; Li, W.; Ruan, K.; Lin, H.; Jin, Y. Members of miR-169 family are induced by high salinity and transiently inhibit the NF-YA transcription factor. BMC Molecular Biology 2009, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.C.; Liu, P.P.; Goloviznina, N.A.; Nonogaki, H. microRNA, seeds, and Darwin?: diverse function of miRNA in seed biology and plant responses to stress. Journal of Experimental Botany 2010, 61, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, N.; Yuan, S.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Hu, Q.; Luo, H. Heterologous expression of a rice miR395 gene in Nicotiana tabacum impairs sulfate homeostasis. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 28791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthewman, C.A.; Kawashima, C.G.; Húska, D.; Csorba, T.; Dalmay, T.; Kopriva, S. miR395 is a general component of the sulfate assimilation regulatory network in Arabidopsis. FEBS Letters 2012, 586, 3242–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, T.J.; Aung, K.; Lin, S.I.; Wu, C.C.; Chiang, S.F.; lin Su, C. Regulation of Phosphate Homeostasis by MicroRNA in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2006, 18, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazin, J.; Baerenfaller, K.; Gosai, S.J.; Gregory, B.D.; Crespi, M.; Bailey-Serres, J. Global analysis of ribosome-associated noncoding RNAs unveils new modes of translational regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Role of MicroRNAs in Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses in Crop Plants. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2014, 174, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E.A.; Araus, V.; Lu, C.; Parry, G.; Green, P.J.; Coruzzi, G.M.; Gutiérrez, R.A. Nitrate-responsive miR393/ AFB3 regulatory module controls root system architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 4477–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; Kang, J.; Wang, T.; Cong, L.; Yang, Q. A Novel miRNA Sponge Form Efficiently Inhibits the Activity of miR393 and Enhances the Salt Tolerance and ABA Insensitivity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 2017, 35, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, S.; Xie, H. Advances in the regulation of plant development and stress response by miR167. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2021, 26, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Lu, Y.; Zinta, G.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.K. UTR-Dependent Control of Gene Expression in Plants. Trends in Plant Science 2018, 23, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, H.; Shinmyo, A.; Kato, K. Preferential translation mediated by Hsp81-3 5’-UTR during heat shock involves ribosome entry at the 5’-end rather than an internal site in Arabidopsis suspension cells. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2008, 105, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D.; Patil, D.P.; Zhou, J.; Zinoviev, A.; Skabkin, M.A.; Elemento, O.; Pestova, T.V.; Qian, S.B.; Jaffrey, S.R. 5’ UTR m6A Promotes Cap-Independent Translation. Cell 2015, 163, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, D.; Voß, B.; Maass, D.; Wüst, F.; Schaub, P.; Beyer, P.; Welsch, R. Carotenogenesis Is Regulated by 5’UTR-Mediated Translation of Phytoene Synthase Splice Variants. Plant Physiology 2016, 172, 2314–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, H.; Takenami, S.; Kubo, Y.; Ueda, K.; Ueda, A.; Yamaguchi, M.; Hirata, K.; Demura, T.; Kanaya, S.; Kato, K. A Computational and Experimental Approach Reveals that the 5’-Proximal Region of the 5’-UTR has a Cis-Regulatory Signature Responsible for Heat Stress-Regulated mRNA Translation in Arabidopsis. Plant and Cell Physiology 2013, 54, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, S.; Sanada, Y.; Imase, R.; Matsuura, H.; Ueno, D.; Demura, T.; Kato, K. Arabidopsis thaliana cold-regulated 47 gene 5’-untranslated region enables stable high-level expression of transgenes. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2018, 125, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hamilton, J.P.; Hardigan, M.; Yin, D.; He, T.; Vaillancourt, B.; Reynoso, M.; Pauluzzi, G.; Funkhouser, S.; Cui, Y.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Jiang, J.; Buell, C.R.; Jiang, N. Analysis of Ribosome-Associated mRNAs in Rice Reveals the Importance of Transcript Size and GC Content in Translation. Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2017, 7, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Du, R.; Meng, X.; Zhao, W.; Kong, L.; Chen, J. Third-Generation Sequencing Indicated that LncRNA Could Regulate eIF2D to Enhance Protein Translation Under Heat Stress in Populus simonii. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 2021, 39, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cheng, Z.; Dong, S.; Li, Z.; Zou, L.; Zhao, P.; Guo, X.; Bao, Y.; Wang, W.; Peng, M. Global identification of full-length cassava lncRNAs unveils the role of cold-responsive intergenic lncRNA 1 in cold stress response. Plant, Cell and Environment 2022, 45, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, T.E. Translation initiation: adept at adapting. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 1999, 24, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terenin, I.M.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Andreev, D.E.; Royall, E.; Belsham, G.J.; Roberts, L.O.; Shatsky, I.N. A Cross-Kingdom Internal Ribosome Entry Site Reveals a Simplified Mode of Internal Ribosome Entry. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2005, 25, 7879–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holcik, M.; Sonenberg, N.; Korneluk, R.G. Internal ribosome initiation of translation and the control of cell death. Trends in Genetics 2000, 16, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelis, S.; Bruynooghe, Y.; Denecker, G.; Huffel, S.V.; Tinton, S.; Beyaert, R. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Cell Cycle–Regulated Internal Ribosome Entry Site. Molecular Cell 2000, 5, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyronnet, S.; Pradayrol, L.; Sonenberg, N. A Cell Cycle–Dependent Internal Ribosome Entry Site. Molecular Cell 2000, 5, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, W.C. Cap-dependent and cap-independent translation in eukaryotic systems. Gene 2004, 332, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingras, A.C.; Raught, B.; Sonenberg, N. eIF4 Initiation Factors: Effectors of mRNA Recruitment to Ribosomes and Regulators of Translation. Annual Review of Biochemistry 1999, 68, 913–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubtsova, M.P.; Sizova, D.V.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Ivanov, D.S.; Prassolov, V.S.; Shatsky, I.N. Distinctive Properties of the 5’-Untranslated Region of Human Hsp70 mRNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 22350–22356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova, T.D.; Zepeda, H.; Martínez-Salas, E.; Martínez, L.M.; Nieto-Sotelo, J.; Jiménez, E.S. Cap-independent translation of maize Hsp101. The Plant Journal 2005, 41, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouiaa, S.; Khoudi, H.; Leidi, E.O.; Pardo, J.M.; Masmoudi, K. Expression of wheat Na+/H+ antiporter TNHXS1 and H+- pyrophosphatase TVP1 genes in tobacco from a bicistronic transcriptional unit improves salt tolerance. Plant Molecular Biology 2012, 79, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorokhov, Y.L.; Skulachev, M.V.; Ivanov, P.A.; Zvereva, S.D.; Tjulkina, L.G.; Merits, A.; Gleba, Y.Y.; Hohn, T.; Atabekov, J.G. Polypurine (A)-rich sequences promote cross-kingdom conservation of internal ribosome entry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 5301–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, H.; Peer, W.A.; Richter, G.; Blakeslee, J.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Titapiwantakun, B.; Undurraga, S.; Khodakovskaya, M.; Richards, E.L.; Krizek, B.; Murphy, A.S.; Gilroy, S.; Gaxiola, R. Arabidopsis H+ -PPase AVP1 Regulates Auxin-Mediated Organ Development. Science 2005, 310, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, K.; Aida, N.K.; S. ; ra, G.; Khaled, M. Optimization of regeneration and transformation parameters in tomato and improvement of its salinity and drought tolerance. African Journal of Biotechnology 2009, 8, 6068–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, S.; Mukhtar, Z.; Nazir, F.; Hashmi, J.A.; Mansoor, S.; Zafar, Y.; Arshad, M. Silicon Carbide Whisker-Mediated Embryogenic Callus Transformation of Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) and Regeneration of Salt Tolerant Plants. Molecular Biotechnology 2008, 40, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU, H.; WANG, Q.; YU, M.; ZHANG, Y.; WU, Y.; ZHANG, H. Transgenic salt-tolerant sugar beet ( Beta vulgaris L.) constitutively expressing an Arabidopsis thaliana vacuolar Na+ / H+ antiporter gene, AtNHX3 , accumulates more soluble sugar but less salt in storage roots. Plant, Cell and Environment 2008, 31, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LI, Z.; BALDWIN, C.M.; HU, Q.; LIU, H.; LUO, H. Heterologous expression of Arabidopsis H+ -pyrophosphatase enhances salt tolerance in transgenic creeping bentgrass ( Agrostis stolonifera L.). Plant, Cell and Environment 2010, 33, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Rao, S.; Chang, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Hou, X.; Zhu, X.; Wu, H.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, C.; Huang, T. AtLa1 protein initiates IRES-dependent translation of WUSCHEL mRNA and regulates the stem cell homeostasis of A rabidopsis in response to environmental hazards. Plant, Cell and Environment 2015, 38, 2098–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouiaa, S.; Khoudi, H. Co-expression of vacuolar Na+/ H+ antiporter and H+-pyrophosphatase with an IRES-mediated dicistronic vector improves salinity tolerance and enhances potassium biofortification of tomato. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán, V.; Leidi, E.O.; Andrés, Z.; Rubio, L.; Luca, A.D.; Fernández, J.A.; Cubero, B.; Pardo, J.M. Ion Exchangers NHX1 and NHX2 Mediate Active Potassium Uptake into Vacuoles to Regulate Cell Turgor and Stomatal Function in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1127–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, I.; Grill, S.; Gualerzi, C.O.; Blasi, U. Leaderless mRNAs in bacteria: surprises in ribosomal recruitment and translational control. Molecular Microbiology 2002, 43, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, I. Translation initiation with 70S ribosomes: an alternative pathway for leaderless mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2004, 32, 3354–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Matsunaga, N.; Akabane, S.; Yasuda, I.; Ueda, T.; Takeuchi-Tomita, N. Reconstitution of mammalian mitochondrial translation system capable of correct initiation and long polypeptide synthesis from leaderless mRNA. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remes, C.; Khawaja, A.; Pearce, S.F.; Dinan, A.M.; Gopalakrishna, S.; Cipullo, M.; Kyriakidis, V.; Zhang, J.; Dopico, X.C.; Yukhnovets, O.; Atanassov, I.; Firth, A.E.; Cooperman, B.; Rorbach, J. Translation initiation of leaderless and polycistronic transcripts in mammalian mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreev, D.E.; Terenin, I.M.; Dunaevsky, Y.E.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Shatsky, I.N. A Leaderless mRNA Can Bind to Mammalian 80S Ribosomes and Direct Polypeptide Synthesis in the Absence of Translation Initiation Factors. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2006, 26, 3164–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akulich, K.A.; Andreev, D.E.; Terenin, I.M.; Smirnova, V.V.; Anisimova, A.S.; Makeeva, D.S.; Arkhipova, V.I.; Stolboushkina, E.A.; Garber, M.B.; Prokofjeva, M.M.; Spirin, P.V.; Prassolov, V.S.; Shatsky, I.N.; Dmitriev, S.E. Four translation initiation pathways employed by the leaderless mRNA in eukaryotes. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 37905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, A.B.; Qureshi, A.A. Leaderless mRNAs are circularized in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii mitochondria. Current Genetics 2018, 64, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.; Peixeiro, I.; Romão, L. Gene Expression Regulation by Upstream Open Reading Frames and Human Disease. PLoS Genetics 2013, 9, e1003529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, T.G.; Bazzini, A.A.; Giraldez, A.J. Upstream ORF s are prevalent translational repressors in vertebrates. The EMBO Journal 2016, 35, 706–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, Y. uORF Shuffling Fine-Tunes Gene Expression at a Deep Level of the Process. Plants 2020, 9, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Arnim, A.G.; Jia, Q.; Vaughn, J.N. Regulation of plant translation by upstream open reading frames. Plant Science 2014, 214, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashikanth, M.; Krishna, A.R.; Ramya, G.; Devi, G.; Ulaganathan, K. Genome-wide comparative analysis of Oryza sativa (japonica) and Arabidopsis thaliana 5’-UTR sequences for translational regulatory signals. Plant Biotechnology 2008, 25, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Arce, A.J.D.; Noderer, W.L.; Wang, C.L. Complete motif analysis of sequence requirements for translation initiation at non-AUG start codons. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. The scanning model for translation: an update. Journal of Cell Biology 1989, 108, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.J.; Hellen, C.U.T.; Pestova, T.V. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2010, 11, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.K.; Wek, R.C. Upstream Open Reading Frames Differentially Regulate Gene-specific Translation in the Integrated Stress Response. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 16927–16935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.P.B. The evolution and diversity of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, A. Role of SMG-1-mediated Upf1 phosphorylation in mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Genes to Cells 2013, 18, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.P.; Loughran, G.; Atkins, J.F. uORFs with unusual translational start codons autoregulate expression of eukaryotic ornithine decarboxylase homologs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 10079–10084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Horst, S.; Filipovska, T.; Hanson, J.; Smeekens, S. Metabolite Control of Translation by Conserved Peptide uORFs: The Ribosome as a Metabolite Multisensor. Plant Physiology 2020, 182, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, A.; Elzinga, N.; Wobbes, B.; Smeekens, S. A Conserved Upstream Open Reading Frame Mediates Sucrose-Induced Repression of Translation[W]. The Plant Cell 2004, 16, 1717–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.; Dadalto, S.; Gonçalves, A.; Souza, G.D.; Barros, V.; Fietto, L. Plant bZIP Transcription Factors Responsive to Pathogens: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14, 7815–7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sornaraj, P.; Luang, S.; Lopato, S.; Hrmova, M. Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors involved in abiotic stresses: A molecular model of a wheat bZIP factor and implications of its structure in function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2016, 1860, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noman, A.; Liu, Z.; Aqeel, M.; Zainab, M.; Khan, M.I.; Hussain, A.; Ashraf, M.F.; Li, X.; Weng, Y.; He, S. Basic leucine zipper domain transcription factors: the vanguards in plant immunity. Biotechnology Letters 2017, 39, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H.; Sato, K.; Berberich, T.; Miyazaki, A.; Ozaki, R.; Imai, R.; Kusano, T. LIP19, a Basic Region Leucine Zipper Protein, is a Fos-like Molecular Switch in the Cold Signaling of Rice Plants. Plant and Cell Physiology 2005, 46, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, F.; Maeta, E.; Terashima, A.; Kawaura, K.; Ogihara, Y.; Takumi, S. Development of abiotic stress tolerance via bZIP-type transcription factor LIP19 in common wheat. Journal of Experimental Botany 2008, 59, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditzer, A.; Bartels, D. Identification of a dehydration and ABA-responsive promoter regulon and isolation of corresponding DNA binding proteins for the group 4 LEA gene CpC2 from C. plantagineum. Plant Molecular Biology 2006, 61, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, U.K.S.; Ganapathi, T.R. Transgenic banana plants overexpressing MusabZIP53 display severe growth retardation with enhanced sucrose and polyphenol oxidase activity. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2014, 116, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.; Pedrotti, L.; Weiste, C.; Fekete, A.; Schierstaedt, J.; Göttler, J.; Kempa, S.; Krischke, M.; Dietrich, K.; Mueller, M.J.; Vicente-Carbajosa, J.; Hanson, J.; Dröge-Laser, W. Crosstalk between Two bZIP Signaling Pathways Orchestrates Salt-Induced Metabolic Reprogramming in Arabidopsis Roots. The Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2244–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, H.; Lv, X.; Liu, D.; Wen, X.; Liao, Y. Effect of polyamines on the grain filling of wheat under drought stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2016, 100, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Merewitz, E.B. Polyamine Application Effects on Gibberellic Acid Content in Creeping Bentgrass during Drought Stress. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2017, 142, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Q. The Effect of Exogenous Spermidine Concentration on Polyamine Metabolism and Salt Tolerance in Zoysiagrass (Zoysia japonica Steud) Subjected to Short-Term Salinity Stress. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peynevandi, K.M.; Razavi, S.M.; Zahri, S. The ameliorating effects of polyamine supplement on physiological and biochemical parameters of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni under cold stress. Plant Production Science 2018, 21, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, T.E.; Ivanov, I.P. Roles of polyamines in translation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293, 18719–18729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I.P.; Atkins, J.F.; Michael, A.J. A profusion of upstream open reading frame mechanisms in polyamine-responsive translational regulation. Nucleic Acids Research 2010, 38, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfrey, C.; Elliott, K.A.; Franceschetti, M.; Mayer, M.J.; Illingworth, C.; Michael, A.J. A Dual Upstream Open Reading Frame-based Autoregulatory Circuit Controlling Polyamine-responsive Translation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 39229–39237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, A.; Akiyama, T.; Kato, T.; Sato, S.; Tabata, S.; Yamamoto, K.T.; Takahashi, T. Spermine is not essential for survival of Arabidopsis. FEBS Letters 2004, 556, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, A.; Hanzawa, Y.; Komura, M.; Yamamoto, K.T.; Komeda, Y.; Takahashi, T. The dwarf phenotype of the Arabidopsis acl5 mutant is suppressed by a mutation in an upstream ORF of a bHLH gene. Development 2006, 133, 3575–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, C.A.; Jorgensen, R.A. Identification of novel conserved peptide uORF homology groups in Arabidopsis and rice reveals ancient eukaryotic origin of select groups and preferential association with transcription factor-encoding genes. BMC Biology 2007, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishitsuka, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Miyamoto, M.; Kuwashiro, Y.; Imai, A.; Motose, H.; Takahashi, T. Complexity and Conservation of Thermospermine-Responsive uORFs of SAC51 Family Genes in Angiosperms. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Chan, Z. ROS Regulation During Abiotic Stress Responses in Crop Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Rivero, R.M.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. The Plant Journal 2017, 90, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, N.A.; Shafiq, F.; Ashraf, M. Ascorbic Acid-A Potential Oxidant Scavenger and Its Role in Plant Development and Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broad, R.C.; Bonneau, J.P.; Beasley, J.T.; Roden, S.; Sadowski, P.; Jewell, N.; Brien, C.; Berger, B.; Tako, E.; Glahn, R.P.; Hellens, R.P.; Johnson, A.A.T. Effect of Rice GDP-L-Galactose Phosphorylase Constitutive Overexpression on Ascorbate Concentration, Stress Tolerance, and Iron Bioavailability in Rice. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laing, W.A.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.; Wright, M.A.; Bulley, S.M.; Brewster, D.; Dare, A.P.; Rassam, M.; Wang, D.; Storey, R.; Macknight, R.C.; Hellens, R.P. An Upstream Open Reading Frame Is Essential for Feedback Regulation of Ascorbate Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2015, 27, 772–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Si, X.; Ji, X.; Fan, R.; Liu, J.; Chen, K.; Wang, D.; Gao, C. Genome editing of upstream open reading frames enables translational control in plants. Nature Biotechnology 2018, 36, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serganov, A.; Nudler, E. A Decade of Riboswitches. Cell 2013, 152, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocobza, S.; Adato, A.; Mandel, T.; Shapira, M.; Nudler, E.; Aharoni, A. Riboswitch-dependent gene regulation and its evolution in the plant kingdom. Genes and Development 2007, 21, 2874–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkert, B.; Narberhaus, F. Microbial thermosensors. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2009, 66, 2661–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortmann, J.; Narberhaus, F. Bacterial RNA thermometers: molecular zippers and switches. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2012, 10, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samtani, H.; Unni, G.; Khurana, P. Microbial Mechanisms of Heat Sensing. Indian Journal of Microbiology 2022, 62, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somero, G.N. RNA thermosensors: how might animals exploit their regulatory potential? Journal of Experimental Biology 2018, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.Y.W.; Balcerowicz, M.; Antonio, M.D.; Jaeger, K.E.; Geng, F.; Franaszek, K.; Marriott, P.; Brierley, I.; Firth, A.E.; Wigge, P.A. An RNA thermoswitch regulates daytime growth in Arabidopsis. Nature Plants 2020, 6, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Oh, H.J.; Goh, C.J.; Lee, K.; Hahn, Y. Heat Shock RNA 1, Known as a Eukaryotic Temperature-Sensing Noncoding RNA, Is of Bacterial Origin. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2015, 25, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Tang, Y.; Ritchey, L.E.; Tack, D.C.; Zhu, M.; Bevilacqua, P.C.; Assmann, S.M. Genome-wide RNA structurome reprogramming by acute heat shock globally regulates mRNA abundance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 12170–12175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.E.; Balcerowicz, M.; Chung, B.Y.W. RNA structure mediated thermoregulation: What can we learn from plants? Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume-Schöpfer, D.; Jaeger, K.E.; Geng, F.; Doccula, F.G.; Costa, A.; Webb, A.A.R.; Wigge, P.A. Ribosomes act as cryosensors in plants. bioRxiv, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirpe, F.; Barbieri, L.; Gorini, P.; Valbonesi, P.; Bolognesi, A.; Polito, L. Activities associated with the presence of ribosome-inactivating proteins increase in senescent and stressed leaves. FEBS Letters 1996, 382, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippmann, J.F.; Michalowski, C.B.; Nelson, D.E.; Bohnert, H.J. Induction of a ribosome-inactivating protein upon environmental stress. Plant Molecular Biology 1997, 35, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Seidel, F.; Beine-Golovchuk, O.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Eshraky, K.E.; Gorka, M.; Cheong, B.E.; Jimenez-Posada, E.V.; Walther, D.; Skirycz, A.; Roessner, U.; Kopka, J.; Firmino, A.A.P. Spatially Enriched Paralog Rearrangements Argue Functionally Diverse Ribosomes Arise during Cold Acclimation in Arabidopsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefos, G.C.; Theodorou, G.; Politis, I. DNA G-quadruplexes: functional significance in plant and farm animal science. Animal Biotechnology 2021, 32, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugaut, A.; Balasubramanian, S. 5’-UTR RNA G-quadruplexes: translation regulation and targeting. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40, 4727–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Cho, H.S.; Nam, H.; Jo, H.; Yoon, J.; Park, C.; Dang, T.V.T.; Kim, E.; Jeong, J.; Park, S.; Wallner, E.S.; Youn, H.; Park, J.; Jeon, J.; Ryu, H.; Greb, T.; Choi, K.; Lee, Y.; Jang, S.K.; Ban, C.; Hwang, I. Translational control of phloem development by RNA G-quadruplex–JULGI determines plant sink strength. Nature Plants 2018, 4, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volná, A.; Bartas, M.; Nezval, J.; Špunda, V.; Pečinka, P.; Červeň, J. Searching for G-Quadruplex-Binding Proteins in Plants: New Insight into Possible G-Quadruplex Regulation. BioTech 2021, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, W.O.; Shum, K.T.; Tanner, J.A. G-quadruplex DNA Aptamers and their Ligands: Structure, Function and Application. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2012, 18, 2014–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volná, A.; Bartas, M.; Karlický, V.; Nezval, J.; Kundrátová, K.; Pečinka, P.; Špunda, V.; Červeň, J. G-Quadruplex in Gene Encoding Large Subunit of Plant RNA Polymerase II: A Billion-Year-Old Story. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Duncan, S.; Yang, X.; Abdelhamid, M.A.S.; Huang, L.; Zhang, H.; Benfey, P.N.; Waller, Z.A.E.; Ding, Y. G-quadruplex structures trigger RNA phase separation. Nucleic Acids Research 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoszek, R.; Feist, P.; Ignatova, Z. Insights into the adaptive response of Arabidopsis thaliana to prolonged thermal stress by ribosomal profiling and RNA-Seq. BMC Plant Biology 2016, 16, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, M.A.; Olson, K.J.; Dallaire, P.; Major, F.; Assmann, S.M.; Bevilacqua, P.C. RNA G-Quadruplexes in the model plant species Arabidopsis thaliana: prevalence and possible functional roles. Nucleic Acids Research 2010, 38, 8149–8163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagirici, H.B.; Sen, T.Z. Genome-Wide Discovery of G-Quadruplexes in Wheat: Distribution and Putative Functional Roles. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2020, 10, 2021–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andorf, C.M.; Kopylov, M.; Dobbs, D.; Koch, K.E.; Stroupe, M.E.; Lawrence, C.J.; Bass, H.W. G-Quadruplex (G4) Motifs in the Maize (Zea mays L.) Genome Are Enriched at Specific Locations in Thousands of Genes Coupled to Energy Status, Hypoxia, Low Sugar, and Nutrient Deprivation. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2014, 41, 627–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagirici, H.B.; Budak, H.; Sen, T.Z. Genome-wide discovery of G-quadruplexes in barley. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.K.; Balasubramanian, S. Targeted Detection of G-Quadruplexes in Cellular RNAs. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2015, 54, 6751–6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.K.; Marsico, G.; Balasubramanian, S. Detecting RNA G-Quadruplexes (rG4s) in the Transcriptome. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2018, 10, a032284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Chow, E.Y.C.; Yeung, P.Y.; Zhang, Q.C.; Chan, T.F.; Kwok, C.K. Enhanced transcriptome-wide RNA G-quadruplex sequencing for low RNA input samples with rG4-seq 2.0. BMC Biology 2022, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yang, M.; Deng, H.; Ding, Y. New Era of Studying RNA Secondary Structure and Its Influence on Gene Regulation in Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, M. How do eucaryotic ribosomes select initiation regions in messenger RNA? Cell 1978, 15, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. An analysis of 5’-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 1987, 15, 8125–8148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEIJER, H.A.; THOMAS, A.A. Control of eukaryotic protein synthesis by upstream open reading frames in the 5’-untranslated region of an mRNA. Biochemical Journal 2002, 367, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavener, D.R.; Ray, S.C. Eukaryotic start and stop translation sites. Nucleic Acids Research 1991, 19, 3185–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Recognition of AUG and alternative initiator codons is augmented by G in position +4 but is not generally affected by the nucleotides in positions +5 and +6. The EMBO Journal 1997, 16, 2482–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.; Osnaya, V.G.; Pérez-Martínez, X. Conservation and Variability of the AUG Initiation Codon Context in Eukaryotes. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2019, 44, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Rangan, L.; Ramesh, T.V.; Gupta, M. Comparative analysis of contextual bias around the translation initiation sites in plant genomes. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2016, 404, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lin, J.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Tang, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X. Over-expression of a glutamate dehydrogenase gene, MgGDH, from Magnaporthe grisea confers tolerance to dehydration stress in transgenic rice. Planta 2015, 241, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, M.B.; Ghalei, H.; Ward, E.A.; Potts, E.L.; Karbstein, K. Rps26 directs mRNA-specific translation by recognition of Kozak sequence elements. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology 2017, 24, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, M.B.; Barre, J.L.; Karbstein, K. Translational Reprogramming Provides a Blueprint for Cellular Adaptation. Cell Chemical Biology 2018, 25, 1372–1379.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, D.; Wei, L. Characterizing the heat response of Arabidopsis thaliana from the perspective of codon usage bias and translational regulation. Journal of Plant Physiology 2019, 240, 153012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, S.A.; Molla, K.A.; Henry, R.J.; Bhat, K.V.; Mondal, T.K. Advances in understanding salt tolerance in rice. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2019, 132, 851–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi-Melerdi, E.; Nematzadeh, G.A.; Shokri, E. Isolation and Gene Expression Investigation in Photosynthetic Isoform of Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxylase Gene in Halophytic Grass Aeluropus Littoralis under Salinity Stress. Journal of Crop Breeding 2018, 9, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, H.S.; Chakraborty, S.; Deka, H. Stress induced MAPK genes show distinct pattern of codon usage in Arabidopsis thaliana, Glycine max and Oryza sativa. Bioinformation 2014, 10, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohasses, F.C.; Solouki, M.; Ghareyazie, B.; Fahmideh, L.; Mohsenpour, M. Correlation between gene expression levels under drought stress and synonymous codon usage in rice plant by in-silico study. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0237334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, M.M.; Almotairy, H.M. Analysis of Heat Shock Proteins Based on Amino Acids for the Tomato Genome. Genes 2022, 13, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Qiao, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Xu, S.; Sun, D. Factors affecting the rapid changes of protein under short-term heat stress. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kage, U.; Powell, J.J.; Gardiner, D.M.; Kazan, K. Ribosome profiling in plants: what is not lost in translation? Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 71, 5323–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingolia, N.T. Ribosome profiling: new views of translation, from single codons to genome scale. Nature Reviews Genetics 2014, 15, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Shi, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Sun, S.; Xie, S.; Li, X.; Zeng, B.; Peng, L.; Hauck, A.; Zhao, H.; Song, W.; Fan, Z.; Lai, J. Ribosome profiling reveals dynamic translational landscape in maize seedlings under drought stress. The Plant Journal 2015, 84, 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.L.; Song, G.; Walley, J.W.; Hsu, P.Y. The Tomato Translational Landscape Revealed by Transcriptome Assembly and Ribosome Profiling. Plant Physiology 2019, 181, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntawong, P.; Girke, T.; Bazin, J.; Bailey-Serres, J. Translational dynamics revealed by genome-wide profiling of ribosome footprints in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, M.E.; Chang, I.F.; Gong, F.; Galbraith, D.W.; Bailey-Serres, J. Immunopurification of Polyribosomal Complexes of Arabidopsis for Global Analysis of Gene Expression. Plant Physiology 2005, 138, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustroph, A.; Zanetti, M.E.; Jang, C.J.H.; Holtan, H.E.; Repetti, P.P.; Galbraith, D.W.; Girke, T.; Bailey-Serres, J. Profiling translatomes of discrete cell populations resolves altered cellular priorities during hypoxia in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 18843–18848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablok, G.; Powell, J.J.; Kazan, K. Emerging Roles and Landscape of Translating mRNAs in Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Liu, C.X.; Chen, L.L.; Zhang, Q.C. RNA structure probing uncovers RNA structure-dependent biological functions. Nature Chemical Biology 2021, 17, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talkish, J.; May, G.; Lin, Y.; Woolford, J.L.; McManus, C.J. Mod-seq: high-throughput sequencing for chemical probing of RNA structure. RNA 2014, 20, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incarnato, D.; Neri, F.; Anselmi, F.; Oliviero, S. Genome-wide profiling of mouse RNA secondary structures reveals key features of the mammalian transcriptome. Genome Biology 2014, 15, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitale, R.C.; Flynn, R.A.; Zhang, Q.C.; Crisalli, P.; Lee, B.; Jung, J.W.; Kuchelmeister, H.Y.; Batista, P.J.; Torre, E.A.; Kool, E.T.; Chang, H.Y. Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nature 2015, 519, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smola, M.J.; Weeks, K.M. In-cell RNA structure probing with SHAPE-MaP. Nature Protocols 2018, 13, 1181–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, I.M.; Gregory, B.D. Transcriptome-wide ribonuclease-mediated protein footprinting to identify RNA–protein interaction sites. Methods 2015, 72, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, I.M.; Li, F.; Alexander, A.; Goff, L.; Trapnell, C.; Rinn, J.L.; Gregory, B.D. RNase-mediated protein footprint sequencing reveals protein-binding sites throughout the human transcriptome. Genome Biology 2014, 15, R3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Hanson, J.; Paliwal, K.; Zhou, Y. RNA secondary structure prediction using an ensemble of two-dimensional deep neural networks and transfer learning. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Akiyama, M.; Sakakibara, Y. RNA secondary structure prediction using deep learning with thermodynamic integration. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Singh, D.; Singh, A.; Eswarappa, S.M. Identification of mRNAs that undergo stop codon readthrough in Arabidopsis thaliana. bioRxiv, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Hong, Y.; Li, Q.Q. Heat Shock Responsive Gene Expression Modulated by mRNA Poly(A) Tail Length. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnot, T.; Nagel, D.H. Time of the day prioritizes the pool of translating mRNAs in response to heat stress. The Plant Cell 2021, 33, 2164–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).