Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

21 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Atypical morphological feature

3. Atypical immunophenotype

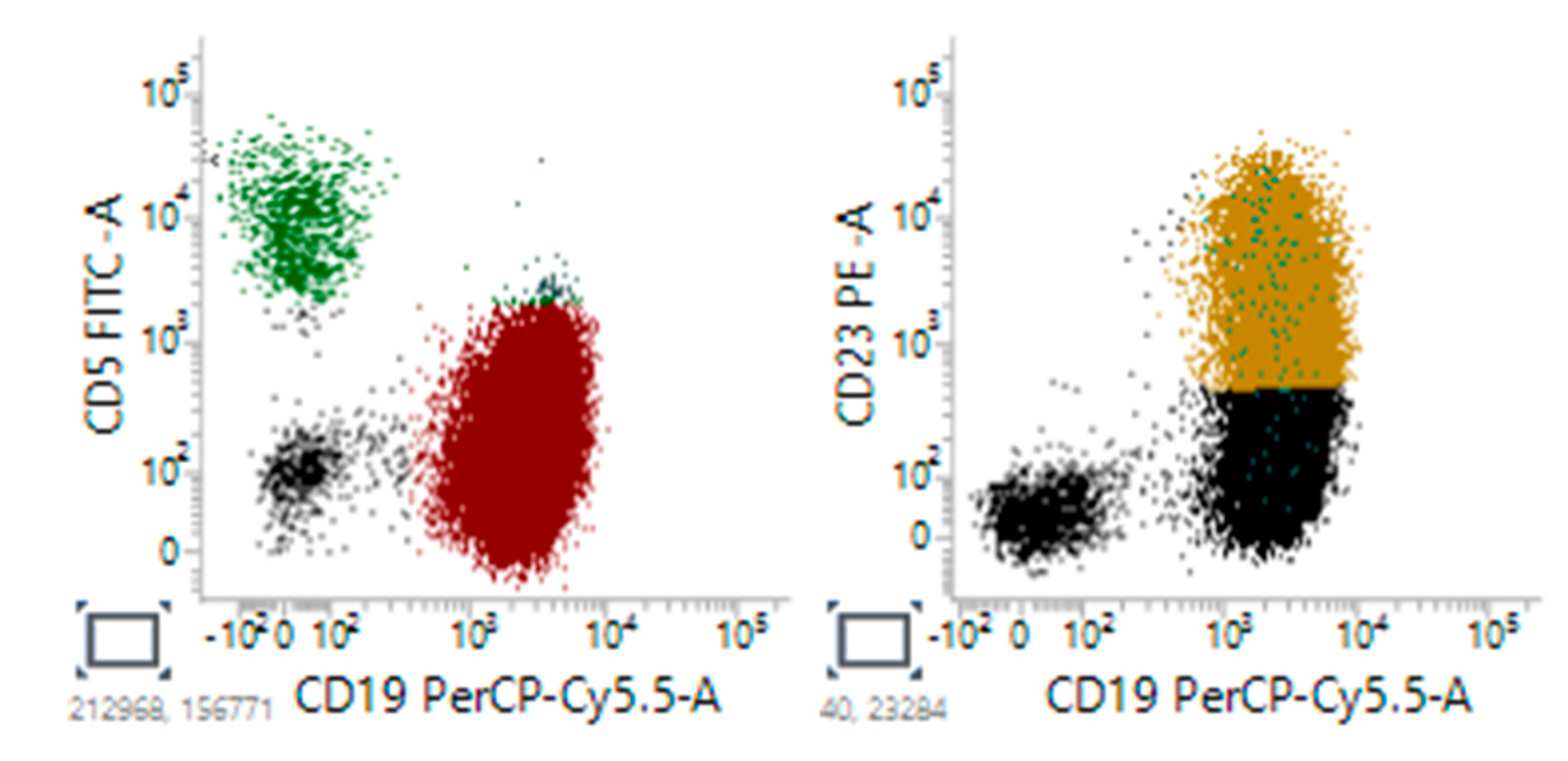

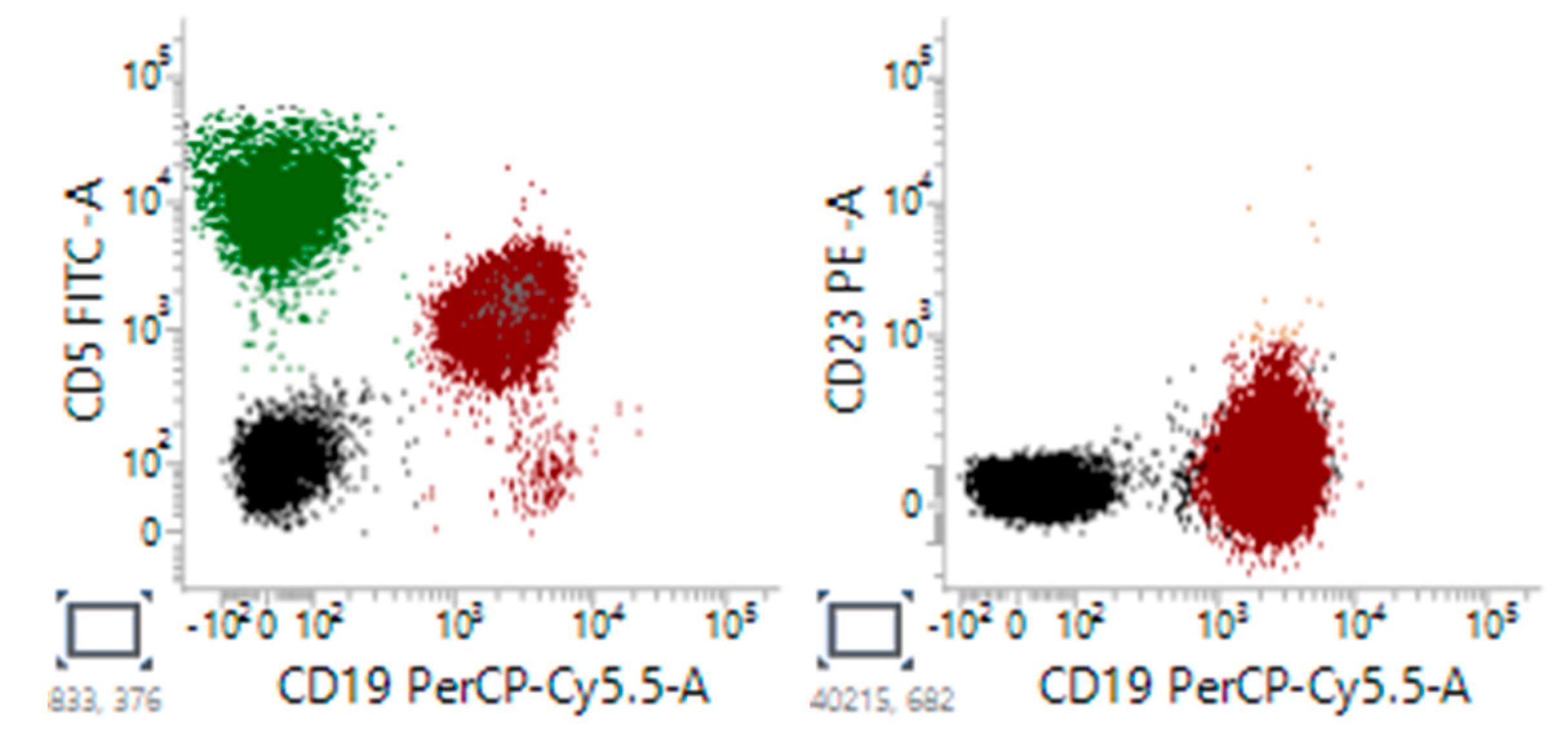

3.1. CD5-negative CLL

4. Atypical genotype

5. Scoring systems for CLL diagnosis

6. Differential diagnosis of atypical CLL with other lymphoproliferative disorders

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hallek, M.; Cheson, B.D.; Catovsky, D.; Caligaris-Cappio, F.; Dighiero, G.; Dohner, H.; Hillmen, P.; Keating, M.; Montserrat, E.; Chiorazzi, N.; et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood. 2018, 131, 2745–2760 / Blood 2018 Jun21;131(25):2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichhorst, B.; Robak, T.; Montserrat, E.; Ghia, P.; Niemann, C.U.; Kater, A.P.; Gregor, M.; Cymbalista, F.; Buske, C.; Hillmen, P.; Hallek, M.; Mey, U. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021, 32, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarfò L, Ferreri AJM, Ghia P. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016, 104, 169–182. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teras L.R., DeSantis C.E., Cerhan J.R., Morton L.M., Jemal A., Flowers C.R. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016, 66, 443–459.

- Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Wagle N.S, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48.

- The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: Leukemia—Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/clyl.html; 2021.

- Campo E., Jaffe E.S., Cook J.R., Quintanilla-Martinez L., Swerdlow S.H., Anderson K.C., Brousset P., Cerroni L., de Leval L., Dirnhofer S., et al. The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: a report from the Clinical Advisory Committee. Blood. 2022, 140, 1229–1253.

- Alaggio R., Amador C., Anagnostopoulos I., Attygalle A.D., Araujo IBO, Berti E., Bhagat G., Borges A.B. , Boyer D., Calaminici M., et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022, 36, 1720–1748. [CrossRef]

- Rawstron A.C, Kreuzer K.A., Soosapilla A., Spacek M., Stehlikova O., Gambell P., McIver-Brown N., Villamor N., Psarra K., Arroz M., et al. Reproducible diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia by flow cytometry: an European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC) & European Society for Clinical Cell Analysis (ESCCA) Harmonisation project. Cytom B Clin Cytom. 2018, 94, 121–128.

- Giné E., Martinez A., Villamor N., López-Guillermo A., Camos M., Martinez D., Esteve J., Calvo X., Muntañola A., Abrisqueta P., et al. Expanded and highly active proliferation centers identify a histological subtype of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (“accelerated” chronic lymphocytic leukemia) with aggressive clinical behavior. Haematologica. 2010, 95, 1526–1533.

- Bennett J.M., Catovsky D., Daniel M.T., Flandrin G., Galton D.A., Gralnick H.R., Sultan C. Proposals for the classification of chronic (mature) B and T lymphoid leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) Cooperative Group. J Clin Pathol. 1989, 42, 567–584. [CrossRef]

- Criel A., Michaux L., De Wolf-Peeters C. The concept of typical and atypical chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999, 33, 33–45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landau D.A., Tausch E., Taylor-Weiner A.N., Stewart C., Reiter J.G., Bahlo J., Kluth S., Bozic I., Lawrence M., Böttcher S., et al. Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature. 2015, 526, 525–535.

- Jaffe E.S., Harris N.L., Stein H., Vardiman J.W., eds. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: WHO Press; 2001. Swerdlow S.H, Campo E., Harris N.L., et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: WHO Press; 2008.

- Swerdlow, S.H., Campo E., Harris N.L., et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: WHO Press; 2017.

- Navarro A., Clot G., Martínez-Trillos A., Pinyol M., Jares P., González-Farré B., Martínez D., Trim N., Fernández V., Villamor N., et al. Improved classification of leukemic B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders using a transcriptional and genetic classifier. Haematologica. 2017, 102, e360–e363.

- Sorigue M., Junca J. Atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Brief historical overview and current usage of an equivocal concept. Int J Lab Hematol. 2019, 41, e17–e19.

- Frater J.L., McCarron K.F., Hammel J.P., Shapiro J.L., Miller M.L., Tubbs R.R., Pettay J., Hsi E.D. Typical and atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia differ clinically and immunophenotypically. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001, 116, 655–66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor S.J., Su’ut L., Morgan G.J., Jack A.S. The relationship between typical and atypical B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. A comparative genomic hybridization-based study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000, 114, 448–458. [CrossRef]

- Marionneaux S., Maslak P., Keohane E.M. Morphologic identification of atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia by digital microscopy. Int J Lab Hematol. 2014, 36, 459–464. [CrossRef]

- Matutes E, Attygalle A, Wotherspoon A, Catovsky D. Diagnostic issues in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2010, 23, 3–20. [CrossRef]

- Hallek M, Al-Sawaf O. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2022 update on diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Am J Hematol. 2021, 96, 1679–1705. [CrossRef]

- Oscier DG, Matutes E, Copplestone A, Pickering RM, Chapman R, Gillingham R, Catovsky D, Hamblin TJ. Atypical lymphocyte morphology: an adverse prognostic factor for disease progression in stage A CLL independent of trisomy 12. Br J Haematol 1997, 98, 934–939. [CrossRef]

- Melo JV, Catovsky D, Galton DA. The relationship between chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and prolymphocytic leukaemia. I. Clinical and laboratory features of 300 patients and characterization of an intermediate group. Br J Haematol. 1986, 63, 377–387.

- Ghani AM, Krause JR. Investigation of cell size and nuclear clefts as prognostic parameters in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1986, 58, 2233–2238. [CrossRef]

- Molica S, Alberti A. Investigation of nuclear clefts as a prognostic parameter in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 1988, 41, 62–5;

- Vallespí T, Montserrat E, Sanz MA. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: prognostic value of lymphocyte morphological subtypes. A multivariate survival analysis in 146 patients. Br J Haematol. 1991, 77, 478–485.

- Ahn A, Kim M S, Park C J, Seo E J, Jang S, Cho Y U, Ji M, Choi YM, Lee K H, Lee J Het al. Atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia has a worse prognosis than CLL and shows different clinical and laboratory features from B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. HemaSphere 2019, 3, 864. [CrossRef]

- D'Arena G, Dell'Olio M, Musto P, Cascavilla N, Perla G, Savino L, Greco MM. Morphologically typical and atypical B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias display a different pattern of surface antigenic density. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001, 42, 649–54. [CrossRef]

- Cro L, Ferrario A, Lionetti M, Bertoni F, Zucal N N, Nobili L, Fabris S, Todoerti K, Cortelezzi A, Guffanti A, et al. The clinical and biological features of a series of immunophenotypic variant of B-CLL. Eur J Haematol. 2010, 85, 120–129.

- Criel A, Verhoef G, Vlietinck R, et al. Further characterization of morphologically defined typical and atypical CLL: a clinical, immunophenotypic, cytogenetic, and prognostic study on 390 cases. Br J Haematol. 1997, 97, 383–391. [CrossRef]

- Finn WG, Thangavelu M, Yelavarthi KK, et al. Karyotype correlates with peripheral blood morphology and immunophenotype in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996, 105, 458–467. [CrossRef]

- Marionneaux S, Maslak P, Keohane EM. Morphologic identification of atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia by digital microscopy. Int J Lab Hematol. 2014 Aug;36(4):459-64. [CrossRef]

- Peterson LC, Bloomfield CD, Brunning RD. Relationship of clinical staging and lymphocyte morphology to survival in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1980, 45, 563–567.

- Ralfkiær E, Geisler C, Hansen MM, et al. Nuclear clefts in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a light microscopic and ultrastructural study of a new prognostic parameter. Scand J Haematol. 1983, 30, 5–12.

- Urbaniak M, Iskierka-Jażdżewska E, Majchrzak A, Robak T. Atypical immunophenotype of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Acta Haematol Pol. 2022, 53, 48–52. [CrossRef]

- Sandes AF, de Lourdes Chauffaille M, Oliveira CR, Maekawa Y, Tamashiro N, Takao TT, Ritter EC, Rizzatti EG. CD200 has an important role in the differential diagnosis of mature B-cell neoplasms by multiparameter flow cytometry. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2014, 86, 98–105. [CrossRef]

- Ting YS, Smith SABC, Brown DA, Dodds AJ, Fay KC, Ma DDF, Milliken S, Moore JJ, Sewell WA. CD200 is a useful diagnostic marker for identifying atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia by flow cytometry. Int J Lab Hematol. 2018, 40, 533–539. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh SS, Kallakury BV, Al-Kuraya KA, Meck J, Hartmann DP, Bagg A. CD5-negative, CD10-negative small B-cell leukemia: variant of chronic lymphocytic leukemia or a distinct entity? Am J Hematol. 2002, 71, 306–310 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang JC, Finn WG, Goolsby CL, Variakojis D, Peterson LC. CD5-small B-cell leukemias are rarely classifiable as chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999, 111, 123–130. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delia D, Bonati A, Giardini R, Villa S, De Braud F, Cattoretti G, Rilke F. Expression of the T1 (CD5, p67) surface antigen in B-CLL and B-NHL and its correlation with other B-cell differentiation markers. Hematol Oncol. 1986, 4, 237–248. [CrossRef]

- Cartron G, Linassier C, Bremond JL, Desablens B, Georget MT, Fimbel B, Luthier F, Dutel JL, Lamagnere JP, Colombat P. CD5 negative B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical and biological features of 42 cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998, 31, 209–216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efstathiou S, Tsioulos D, Zacharos I, Tsiakou A, Mastorantonakis S, Salgami E, Katirtzoglou N, Psarra A, Roussou P. The prognostic role of CD5 negativity in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a case-control study. Haematologia (Budap). 2002, 32, 209–218. [CrossRef]

- Demir C, Kara E, Ekinci Ö, Ebinç S. Clinical and Laboratory Features of CD5-Negative Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Med Sci Monit. 2017, 23, 2137–2142. [CrossRef]

- Friedman DR, Guadalupe E, Volkheimer A, Moore JO, Weinberg JB. Clinical outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia associated with expression of CD5, a negative regulator of B-cell receptor signalling. Br J Haematol. 2018, 183, 747–754. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurec AS, Threatte GA, Gottlieb AJ, Smith JR, Anderson J, Davey FR. Immunophenotypic subclassification of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Br J Haematol. 1992, 81, 45–51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano C, Sellitto A, Chiurazzi F, Simeone L, De Fanis U, Raia M, Del Vecchio L, Lucivero G. Clinical and phenotypic features of CD5-negative B cell chronic lymphoproliferative disease resembling chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2015, 101, 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Jurisic V, Colovic N, Kraguljac N, Atkinson HD, Colovic M. Analysis of CD23 antigen expression in B-chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and its correlation with clinical parameters. Med Oncol. 2008, 25, 315–322. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier S, Yang LP, Delespesse G, Rubio M, Biron G, Sarfati M. The two CD23 isoforms display differential regulation in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1995, 89, 373–379. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilo MN, Dorfman DM. The utility of flow cytometric immunophenotypic analysis in the distinction of small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia from mantle cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996, 105, 451–457. [CrossRef]

- Gong JZ, Lagoo AS, Peters D, Horvatinovich JM, Benz P, Buckley PJ. Value of CD23 determination by flow cytometry in differentiating mantle cell lymphoma from chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am J clin Pathol. 2001, 116, 893–897. [CrossRef]

- Barna G, Reiniger L, Tátrai P, Kopper L, Matolcsy A. The cut-off levels of CD23 expression in the differential diagnosis of MCL and CLL. Hematol Oncol. 2008, 26, 167–170. [CrossRef]

- Hjalmar V, Kimby E, Matutes E, Sundström C, Wallvik J, Hast R. Atypical lymphocytes in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and trisomy 12 studied by conventional staining combined with fluorescence in situ hybridization. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000, 37, 571–576. [CrossRef]

- Matutes E, Oscier D, Garcia-Marco J, Ellis J, Copplestone A, Gillingham R, Hamblin T, Lens D, Swansbury GJ, Catovsky D. Trisomy 12 defines a group of CLL with atypical morphology: correlation between cytogenetic, clinical and laboratory features in 544 patients. Br J Haematol. 1996, 92, 382–388.

- Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, Conde L, Ordóñez GR, Villamor N, Escaramis G, Jares P, Beà S, González-Díaz M, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011, 475, 101–105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puente XS, Beà S, Valdés-Mas R, Villamor N, Gutiérrez-Abril J, Martín-Subero JI, Munar M, Rubio-Pérez C, Jares P, Aymerich M, et al. Non-coding recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2015, 526, 519–524.

- Huret, J. t(11;14)(q13;q32). Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 1998, 2, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddasani R, Talwar N, Suarez-Londono JA, Braunstein M. Management of atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia presenting with extreme leukocytosis. Clin Case Rep. 2020, 8, 877–882. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuneo A, Balboni M, Piva N, Rigolin GM, Roberti MG, Mejak C, Moretti S, Bigoni R, Balsamo R, Cavazzini P, et al. Atypical chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with t(11;14)(q13;q32): karyotype evolution and prolymphocytic transformation. Br J Haematol. 1995, 90, 409–416. [CrossRef]

- Gómez Pescie M, Denninghoff V, García A, Rescia C, Avagnina A, Elsner B. Linfoma del manto vs. leucemia linfatica crónica atipica. Utilización de inmunohistoquímica, citometría de flujo y biología molecular para su correcta tipificación [Mantle cell lymphoma vs. atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Use of immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and molecular biology for their adequate typing]. Medicina (B Aires). 2005, 65, 419–424.

- DE Braekeleer M, Tous C, Guéganic N, LE Bris MJ, Basinko A, Morel F, Douet-Guilbert N. Immunoglobulin gene translocations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A report of 35 patients and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016, 4, 682–694. [CrossRef]

- Matutes E, Owusu-Ankomah K, Morilla R, Garcia Marco J, Houlihan A, Que TH, Catovsky D. The immunological profile of B-cell disorders and proposal of a scoring system for the diagnosis of CLL. Leukemia. 1994, 8, 1640–1645.

- Moreau EJ, Matutes E, A'Hern RP, Morilla AM, Morilla RM, Owusu-Ankomah KA, Seon BK, Catovsky D. Improvement of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia scoring system with the monoclonal antibody SN8 (CD79b). Am J Clin Pathol. 1997, 108, 378–382. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Tong X, Huang L, Li L, Wang C, He C, Liu S, Wang Z, Xiao M, Mao X, Zhang D. A new score including CD43 and CD180: Increased diagnostic value for atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Med. 2022, 10, 4387–4396.

- Ho AK, Hill S, Preobrazhensky SN, Miller ME, Chen Z, Bahler DW. Small B-cell neoplasms with typical mantle cell lymphoma immunophenotypes often include chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009, 131, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Qiu L, Xu J, Tang G, Wang SA, Lin P, Ok CY, Garces S, Yin CC, Khanlari M, Vega F, Medeiros LJ, Li S. Mantle cell lymphoma with chronic lymphocytic leukemia-like features: a diagnostic mimic and pitfall. Hum Pathol. 2022, 119, 59–68. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sewefy DA, Khattab DA, Sallam MT, Elsalakawy WA, Dahlia A. Flow cytometric evaluation of CD200 as a tool for differentiation between chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma. Egypt J Haematol. 2014, 39, 42–46. [CrossRef]

- Palumbo GA, Parrinello NL, Fargione G, Cardillo K, Chiarenza A, Berretta S, Conticello C, Villari L, Di Raimondo F. CD200 expression may help in differential diagnosis between mantle cell lymphoma and B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2009, 33, 1212–1216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo GA, Parrinello N, Fargione G, Cardillo K, Chiarenza A, Berretta S, Conticello C, Villari L, Di Raimondo F. CD200 expression may help in differential diagnosis between mantle cell lymphoma and B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2009, 33, 1212–1216. [CrossRef]

- Ting YS, Smith SABC, Brown DA, Dodds AJ, Fay KC, Ma DDF, Milliken S, Moore JJ, Sewell WA. CD200 is a useful diagnostic marker for identifying atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia by flow cytometry. Int J Lab Hematol. 2018, 40, 533–539. [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouri M, Sadat Hosseini M, Jafari L, Mosleh M, Shahabi Satlsar E. A Flow Cytometry Panel for Differential Diagnosis of Mantle Cell Lymphoma from Atypical B-Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia. Iran Biomed J. 2023, 27, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Maljaei SH, Asvadi-E-Kermani I, Eivazi-E-Ziaei J, Nikanfar A, Vaez J. Usefulness of CD45 density in the diagnosis of B-cell chronic lymphoproliferative disorders. Indian J Med Sci. 2005, 59, 187–94. [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam TR, Mohanraj S, Muthu A, Prabhakar V, Ramakrishnan B, Vaidhyanathan L, Easow J, Raja T. Independent diagnostic utility of CD20, CD200, CD43 and CD45 in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2022, 63, 377–384. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann J, Rother M, Kaiser U, Thrun MC, Wilhelm C, Gruen A, Niebergall U, Meissauer U, Neubauer A, Brendel C. Determination of CD43 and CD200 surface expression improves accuracy of B-cell lymphoma immunophenotyping. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2020, 98, 476–482. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir ZN, Falay M, Parmaksiz A, Genc E, Beyler O, Gunes AK, Ceran F, Dagdas S, Ozet G. A novel differential diagnosis algorithm for chronic lymphocytic leukemia using immunophenotyping with flow cytometry. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2023, 45, 176–181. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman DS, Al-Kuwari E, Siveen KS, Al-Abdulla R, Chandra P, Yassin M, Nashwan A, Hilmi FA, Taha RY, Nawaz Z, El-Omri H, Mateo JM, Al-Sabbagh A. Downregulation of Lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1) expression (by immunohistochemistry and/ flow cytometry) in chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia with atypical immunophenotypic and cytologic features. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021, 43, 515–525.

| Authors/ Reference |

No of pts CD5- vs CD5+ | Median age: CD5- vs CD5+ | Definition of CD5- CLL | PB CD5- vs CD5+ |

Treatment CD5- vs CD5+ |

Survival CD5- vs CD5+ |

Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cartron et al 1998 [42] | 42 vs 79 | 68/64.8 | <5% of mononuclear cells | Hb: 126/137 G/L(p=ns) PLT: 216/200 x 109/L (p=ns) Lymphocytes:27.3/32,7 x 109/L x 109/L (p=ns) |

No initially treated:64.3% vs 29.1% | 52% at 120 m vs 6% at 90 m (p=0.97) | CD5- CLL expressed a higher level of surface of immunoglobulin and had more frequently isolated splenomegaly. |

| Efstathiou et al 2002 [43] | 29 vs 29 | 68.8/68.4 | <5% of mononuclear cells | Hb: 131/10.5 G/L(p=ns) (p<0.05) PLT: 211/198 x 109/L(p=ns) Lymphocytes:38.2/39.6 x 109/L (p=ns) |

No initially treated:72.4% vs 24.1% | Median:97.2m vs 84.0m (p=0.0025) |

Splenomegaly, lymph node involvement, and haemolytic anemia less common in CD5- CLL. CD5- CLL patients had a more favourable prognosis compared with CD5+ patients |

| Demir et al. 2017 [44] | 19 vs 105 | 65.8/66.5 | <20% of mononuclear cells | HB: 133/127g/L (p=0.180) PLT: 144/ 160×6 x 109/L (p=0.044) Neutrophils: 3.5/3.36 x 109/L (p=0.169) Lymphocytes: 43.2/ 36.7 x 109/L (p=0.001). |

NR | 84.2% vs 90.5% at 5 yr (p=0.393) | Lymphadenopathy less frequent in CD5- (p=0.029). Splenomegaly more frequent in CD5- (p=0.029). No difference in clinical stage, autoimmune phenomena, hemo- globin and neutrophil count, and survival |

| Kurec et al 1992 [46] | 12 vs 27 | 66/67 | <20% of lymphoid cells | Hb: 11.2/13.7g/L PLT:172/175 x 109/L WBC:88 x 109/L /60 x109/L |

NR | 55% vs 90 % at 5 yr | Lack of CD5 antigen was with more advanced stage of disease and poor patient survival. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).