Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

21 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

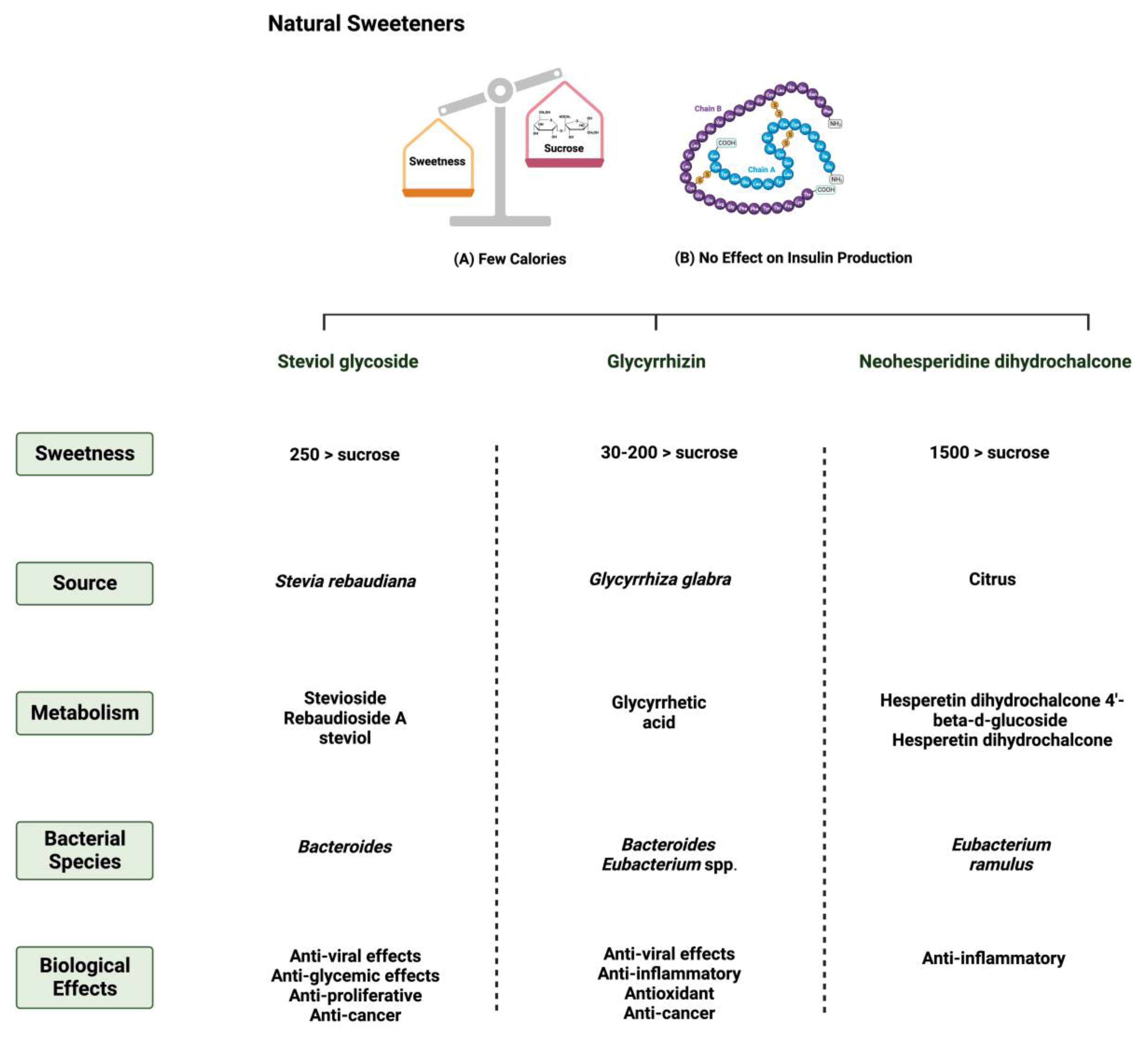

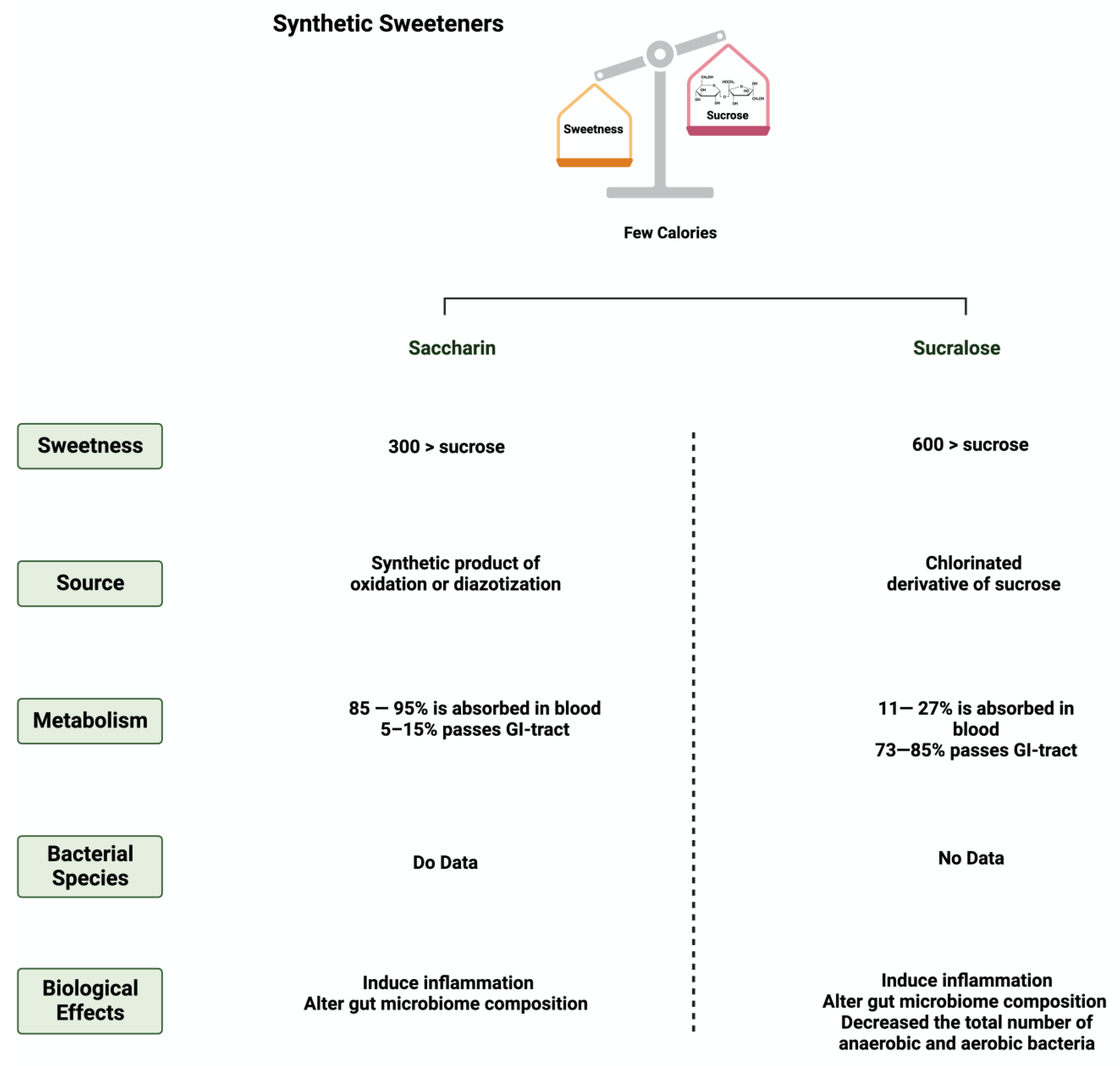

1.1. Natural and Synthetic Sweeteners

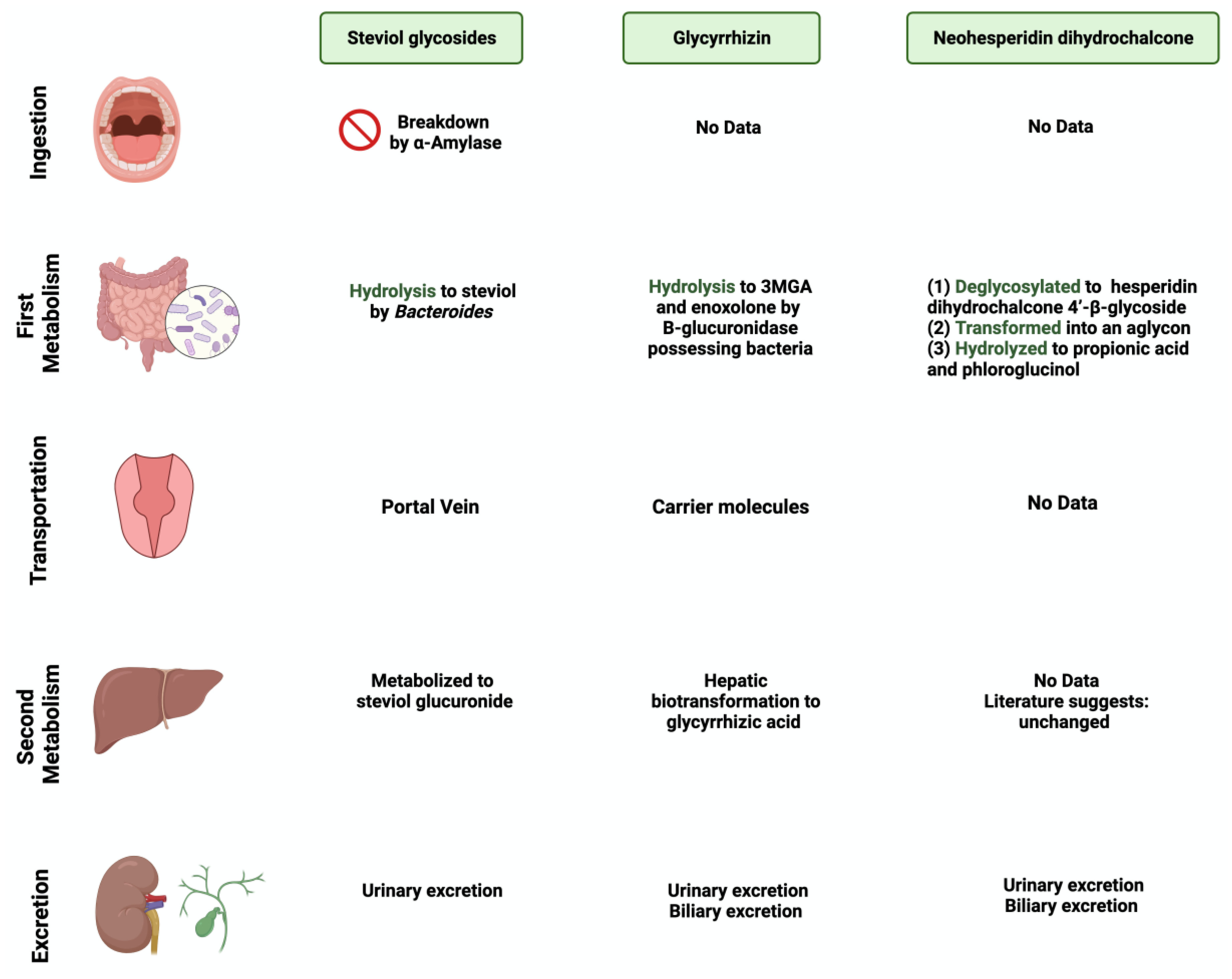

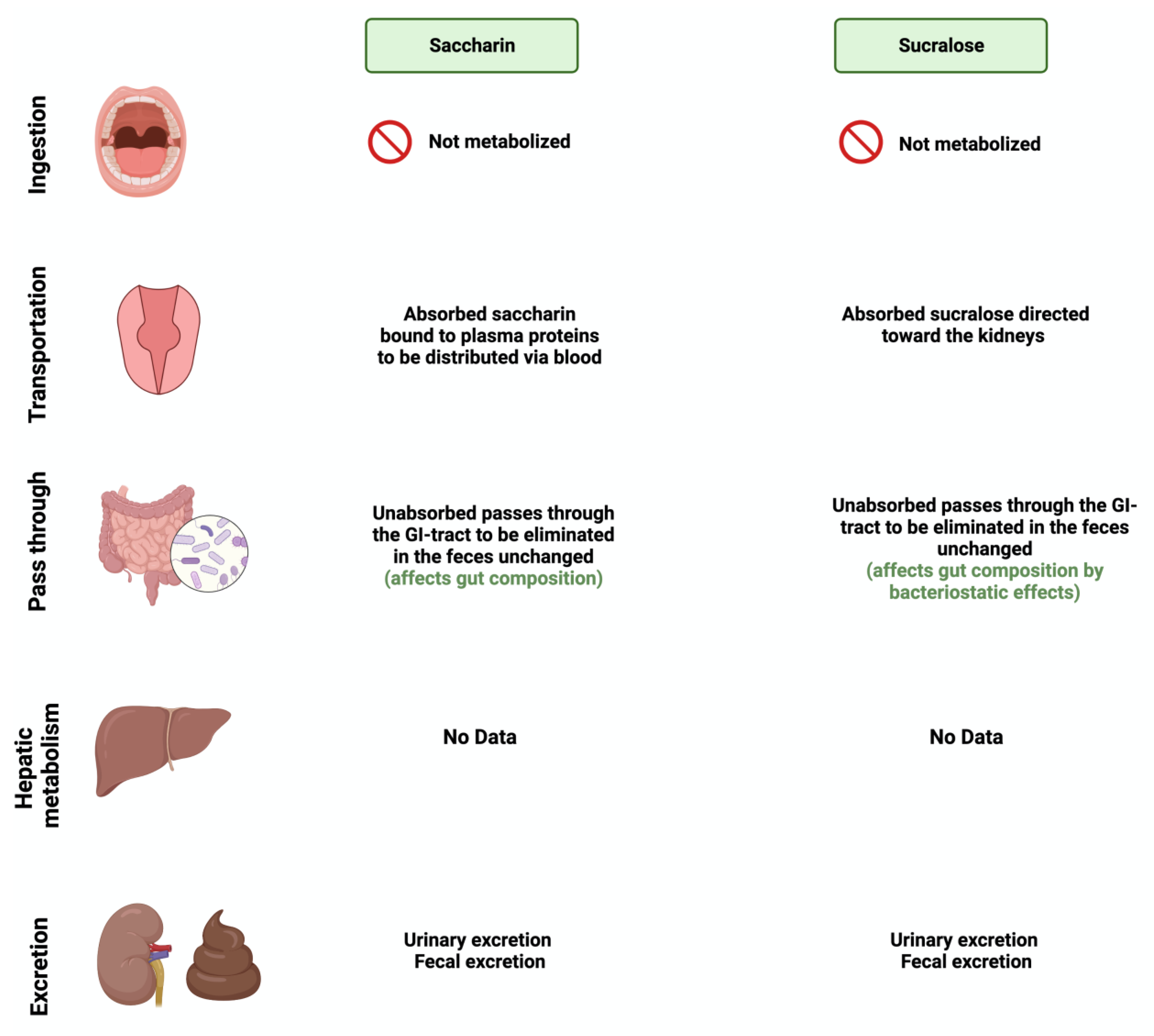

1.2. Metabolization of Sweeteners by Gut Microbiome

1.3. Sweeteners and GI Cancers

2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

3. Sweeteners and the Gut Microbiome

3.1. Steviol glycoside

3.2. Glycyrrhizin

3.3. Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone

3.4. Saccharin

3.5. Sucralose

4. Sweeteners' Role in Gastrointestinal Cancers

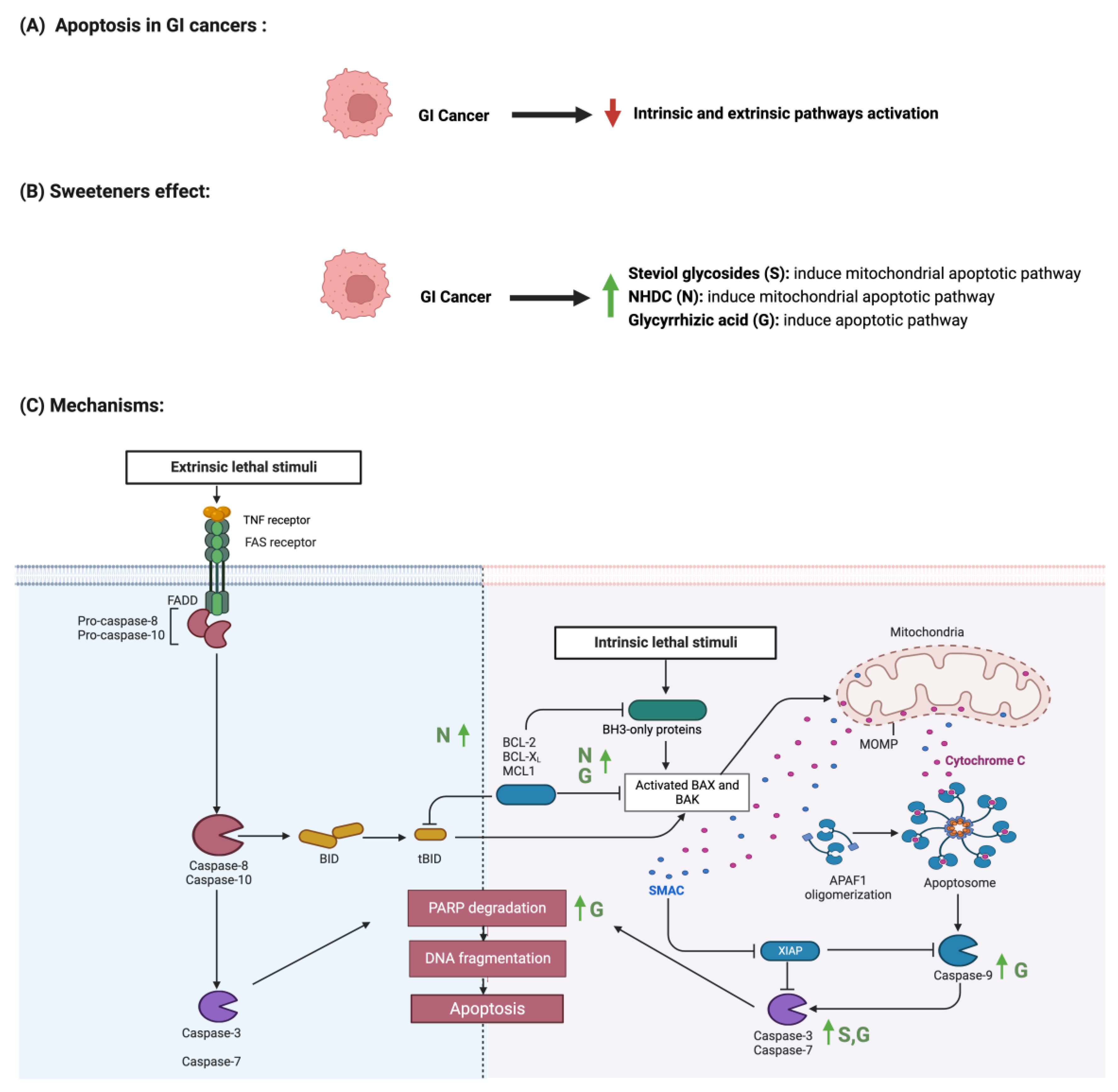

4.1. Apoptosis

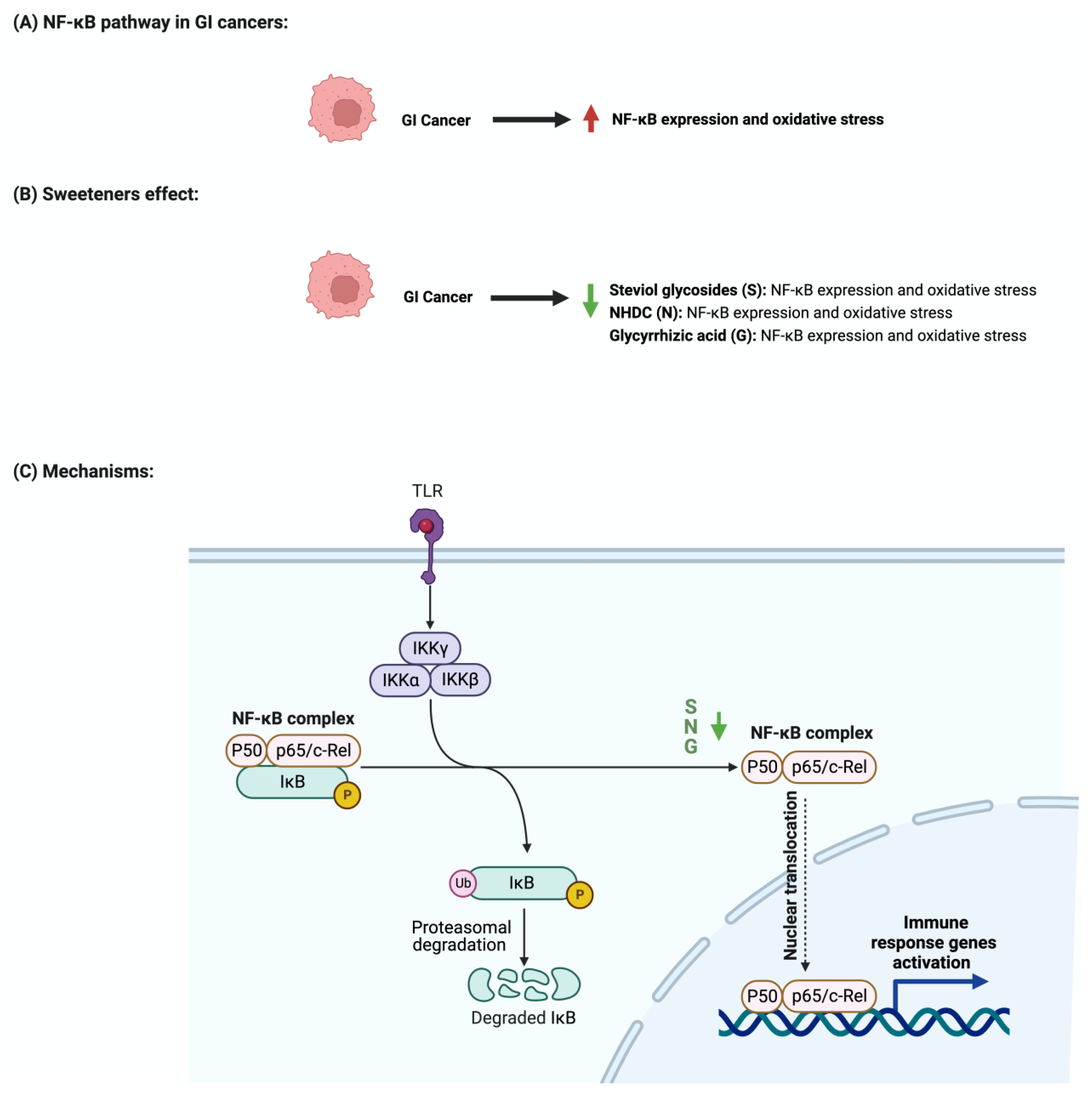

4.2. NF-KB Pathway

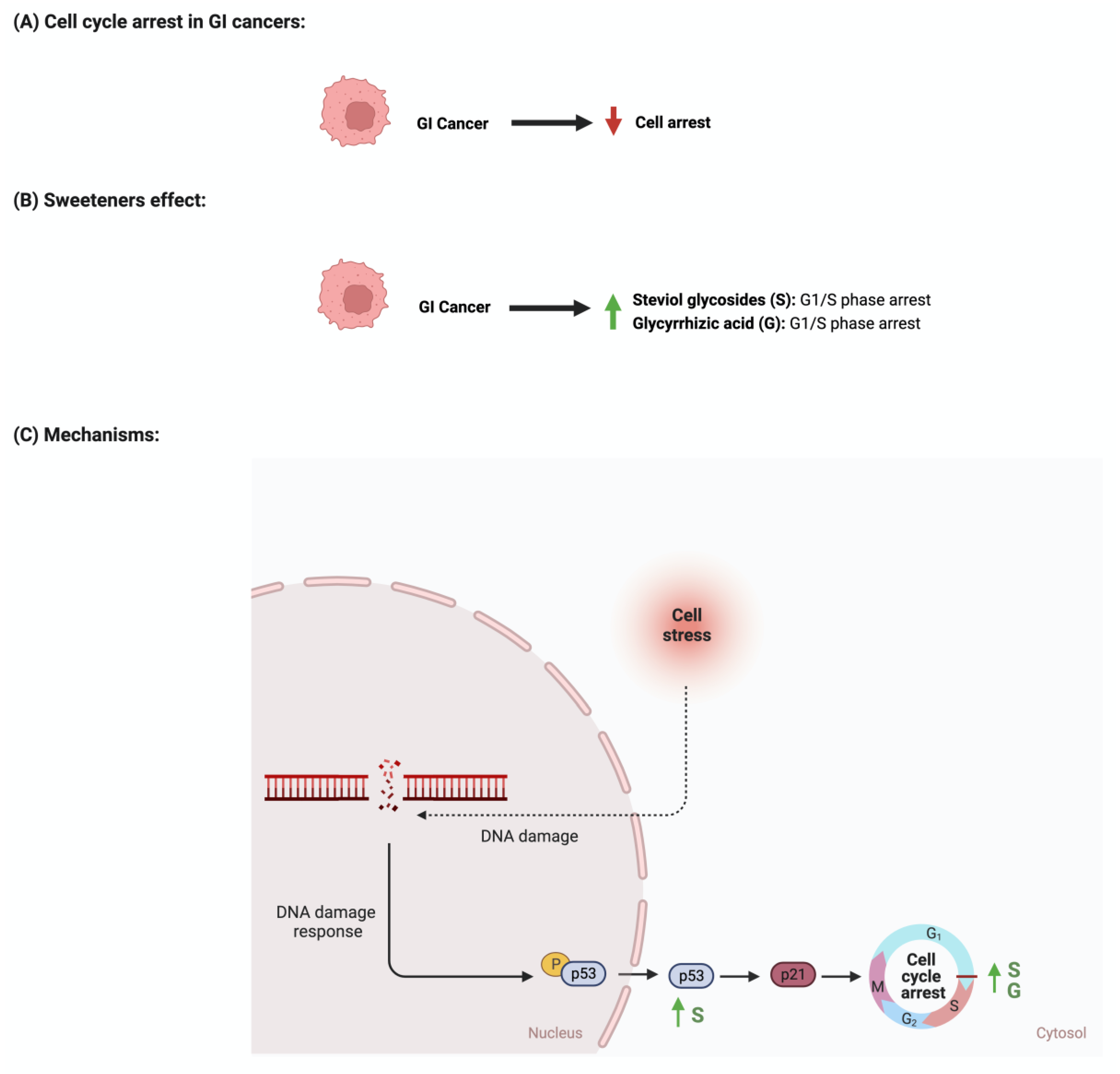

4.3. Cellular Cycle Arrest

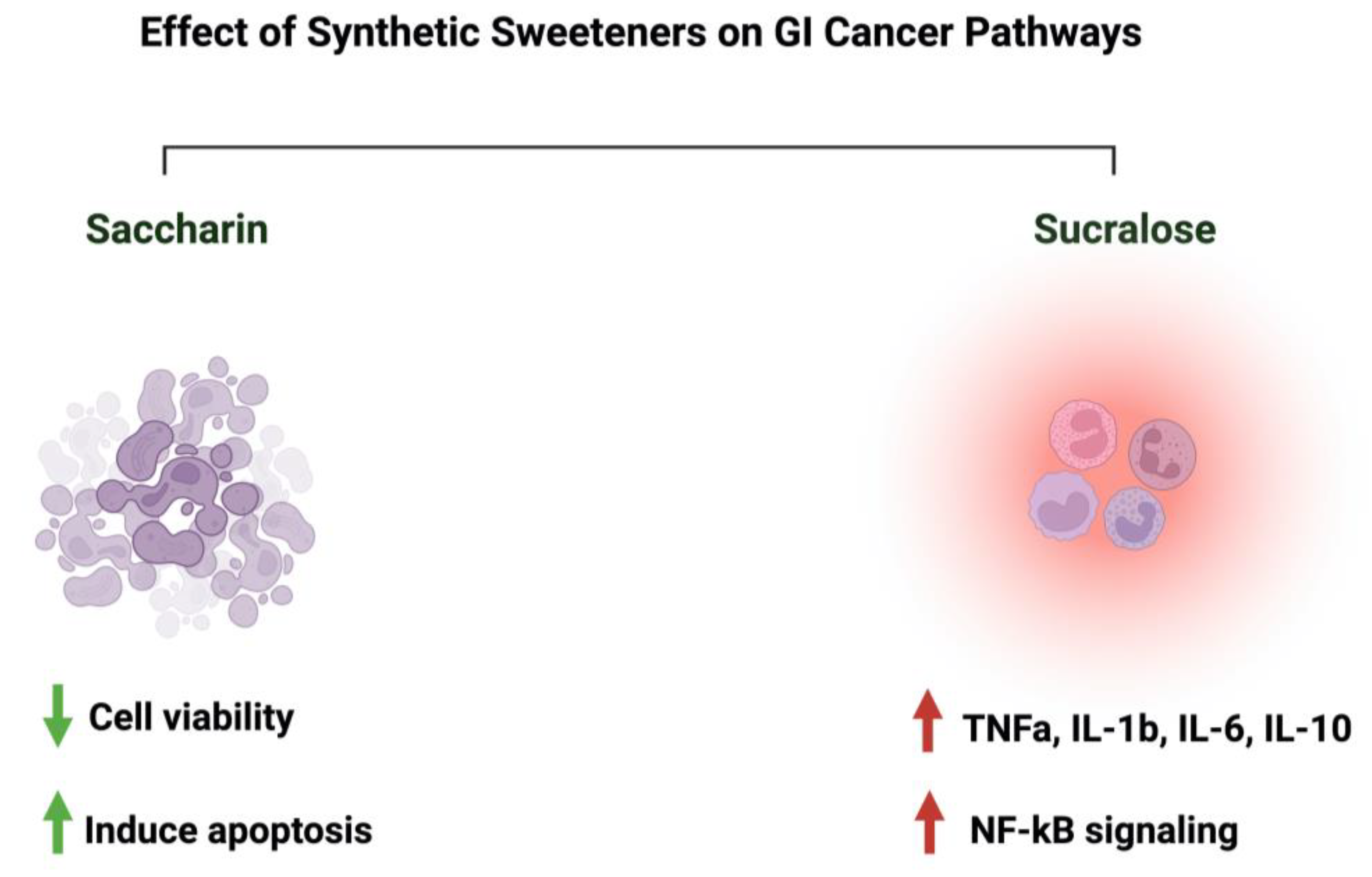

4.4. Synthetic Sweeteners and GI Cancers

5. Discussion

5.1. Safety of Sweeteners and Challenges in the Field

5.2. Sweeteners' Role in Cancer Therapy Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NNS | non-nutritive sweeteners |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| NHDC | neohesperidin dihydrochalcone |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| NF-B | nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

References

- Stanhope, K.L. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2016, 53, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohner, S.; Toews, I.; Meerpohl, J.J. Health outcomes of non-nutritive sweeteners: Analysis of the research landscape. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, A.; Carrascosa, C.; Raheem, D.; Ramos, F.; Raposo, A. Natural Sweeteners: The Relevance of Food Naturalness for Consumers, Food Security Aspects, Sustainability and Health Impacts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grembecka, M. Natural sweeteners in a human diet. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2015, 66, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Carocho, M.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I. Sweeteners as food additives in the XXI century: A review of what is known, and what is to come. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 107, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, S.; Rehman, T.; Saif, S.; Rajoka, M.S.R.; Ranjha, M.; Hassoun, A.; Cropotova, J.; Trif, M.; Younas, A.; Aadil, R.M. Replacement of refined sugar by natural sweeteners: Focus on potential health benefits. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Muñoz, R.; Correa-Delgado, M.; Córdova-Almeida, R.; Lara-Nava, D.; Chávez-Muñoz, M.; Velásquez-Chávez, V.F.; Hernández-Torres, C.E.; Gontarek-Castro, E.; Ahmad, M.Z. Natural sweeteners: Sources, extraction and current uses in foods and food industries. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 130991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvetsky, A.C.; Jin, Y.; Clark, E.J.; Welsh, J.A.; Rother, K.I.; Talegawkar, S.A. Consumption of Low-Calorie Sweeteners among Children and Adults in the United States. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 441–448.e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Sáez-Lara, M.J.; Gil, A. Effects of Sweeteners on the Gut Microbiota: A Review of Experimental Studies and Clinical Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S31–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.R.; Dando, R. The sensory properties and metabolic impact of natural and synthetic sweeteners. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 1554–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, M.A.; Bird, A.R. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients 2014, 7, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, A.M.; Walter, J.; Segal, E.; Spector, T.D. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Br. Med. J. 2018, 361, k2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, R.D., Jr.; Pontefract, B.A.; Mishcon, H.R.; Black, C.A.; Sutton, S.C.; Theberge, C.R. Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. Non-caloric artificial sweeteners and the microbiome: Findings and challenges. Gut Microbes 2015, 6, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, I.L.; Frese, S.A. Non-nutritive sweeteners and their impacts on the gut microbiome and host physiology. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 988144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Thaiss, C.A.; Maza, O.; Israeli, D.; Zmora, N.; Gilad, S.; Weinberger, A.; et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 2014, 514, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Bian, X.; Gao, B.; Tu, P.; Lai, Y.; Ru, H.; Lu, K. Effects of the Artificial Sweetener Neotame on the Gut Microbiome and Fecal Metabolites in Mice. Molecules 2018, 23, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepino, M.Y.; Bourne, C. Non-nutritive sweeteners, energy balance, and glucose homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Abbeele, P.; Van de Wiele, T.; Verstraete, W.; Possemiers, S. The host selects mucosal and luminal associations of coevolved gut microorganisms: A novel concept. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 681–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schernhammer, E.S.; Bertrand, K.A.; Birmann, B.M.; Sampson, L.; Willett, W.C.; Feskanich, D. Consumption of artificial sweetener- and sugar-containing soda and risk of lymphoma and leukemia in men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Cui, W.; Li, D. The relationship between the use of artificial sweeteners and cancer: A meta-analysis of case-control studies. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 4589–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepler, A.; Hoffman, G.; Jindal, S.; Narula, N.; Shah, S.C. Intake of artificial sweeteners among adults is associated with reduced odds of gastrointestinal luminal cancers: A meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. Nutr. Res. 2021, 93, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosetti, C.; Gallus, S.; Talamini, R.; Montella, M.; Franceschi, S.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Artificial sweeteners and the risk of gastric, pancreatic, and endometrial cancers in Italy. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 2235–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Yan, F.; Liu, L.; Li, B.; Liu, S.; Cui, W. Can Artificial Sweeteners Increase the Risk of Cancer Incidence and Mortality: Evidence from Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debras, C.; Chazelas, E.; Srour, B.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Agaësse, C.; De Sa, A.; Lutchia, R.; Gigandet, S.; et al. Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmachari, G.; Mandal, L.C.; Roy, R.; Mondal, S.; Brahmachari, A.K. Stevioside and related compounds—Molecules of pharmaceutical promise: A critical overview. Arch. Pharm. 2011, 344, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carakostas, M.C.; Curry, L.L.; Boileau, A.C.; Brusick, D.J. Overview: The history, technical function and safety of rebaudioside A, a naturally occurring steviol glycoside, for use in food and beverages. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46 (Suppl. 7), S1–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P.; Ayoob, K.T.; Magnuson, B.A.; Wölwer-Rieck, U.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Rogers, P.J.; Rowland, I.; Mathews, R. Stevia Leaf to Stevia Sweetener: Exploring Its Science, Benefits, and Future Potential. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1186s–1205s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana-Paucar, A.M. Steviol Glycosides from Stevia rebaudiana: An Updated Overview of Their Sweetening Activity, Pharmacological Properties, and Safety Aspects. Molecules 2023, 28, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard Anker, C.C.; Rafiq, S.; Jeppesen, P.B. Effect of Steviol Glycosides on Human Health with Emphasis on Type 2 Diabetic Biomarkers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soejima, A.; Tanabe, A.S.; Takayama, I.; Kawahara, T.; Watanabe, K.; Nakazawa, M.; Mishima, M.; Yahara, T. Phylogeny and biogeography of the genus Stevia (Asteraceae: Eupatorieae): An example of diversification in the Asteraceae in the new world. J. Plant Res. 2017, 130, 953–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renwick, A.G.; Tarka, S.M. Microbial hydrolysis of steviol glycosides. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46 (Suppl. 7), S70–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardana, C.; Simonetti, P.; Canzi, E.; Zanchi, R.; Pietta, P. Metabolism of stevioside and rebaudioside A from Stevia rebaudiana extracts by human microflora. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6618–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnuson, B.A.; Carakostas, M.C.; Moore, N.H.; Poulos, S.P.; Renwick, A.G. Biological fate of low-calorie sweeteners. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 670–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwell, M. Stevia, Nature’s Zero-Calorie Sustainable Sweetener: A New Player in the Fight Against Obesity. Nutr. Today 2015, 50, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröfelbauer, B.; Raffetseder, J.; Hauner, M.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; Ernst, W.; Szolar, O.H. Glycyrrhizin, the main active compound in liquorice, attenuates pro-inflammatory responses by interfering with membrane-dependent receptor signalling. Biochem. J. 2009, 421, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Liu, D.; Li, J. Pharmacological perspective: Glycyrrhizin may be an efficacious therapeutic agent for COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohbakhsh, A.; Iranshahy, M.; Iranshahi, M. Glycyrrhetinic Acid and Its Derivatives: Anticancer and Cancer Chemopreventive Properties, Mechanisms of Action and Structure-Cytotoxic Activity Relationship. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, H.R.; Komarova, I.; El-Ghonemi, M.; Fathy, A.; Rashad, R.; Abdelmalak, H.D.; Yerramadha, M.R.; Ali, Y.; Helal, E.; Camporesi, E.M. Licorice abuse: Time to send a warning message. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 3, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.J.; Son, D.H.; Chung, T.H.; Lee, Y.J. A Review of the Pharmacological Efficacy and Safety of Licorice Root from Corroborative Clinical Trial Findings. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.J.; Cho, K.H.; Jung, W.S.; Moon, S.K.; Park, E.K.; Kim, D.H. Biotransformation of ginsenoside Rb1, crocin, amygdalin, geniposide, puerarin, ginsenoside Re, hesperidin, poncirin, glycyrrhizin, and baicalin by human fecal microflora and its relation to cytotoxicity against tumor cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 18, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deutch, M.R.; Grimm, D.; Wehland, M.; Infanger, M.; Krüger, M. Bioactive Candy: Effects of Licorice on the Cardiovascular System. Foods 2019, 8, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbrucker, R.A.; Burdock, G.A. Risk and safety assessment on the consumption of Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza sp.), its extract and powder as a food ingredient, with emphasis on the pharmacology and toxicology of glycyrrhizin. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 46, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Yu, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, W. Effects of Neohesperidin Dihydrochalcone (NHDC) on Oxidative Phosphorylation, Cytokine Production, and Lipid Deposition. Foods 2021, 10, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnig, M.; Bufe, B.; Kratochwil, N.A.; Slack, J.P.; Meyerhof, W. The binding site for neohesperidin dihydrochalcone at the human sweet taste receptor. BMC Struct. Biol. 2007, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, P. The role of dietary sugars in health: Molecular composition or just calories? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, G.; Clifford, M.N. Role of the small intestine, colon and microbiota in determining the metabolic fate of polyphenols. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 139, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Fernández, A.R.; Santacruz, A.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. The complex relationship between metabolic syndrome and sweeteners. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 1511–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.; Manthey, J.A.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. Neohesperidin Dihydrochalcone and Neohesperidin Dihydrochalcone-O-Glycoside Attenuate Subcutaneous Fat and Lipid Accumulation by Regulating PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway In Vivo and In Vitro. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, S.; Gómez-Martínez, S.; Díaz, L.E.; Nova, E.; Urrialde, R.; Marcos, A. Potential Effects of Sucralose and Saccharin on Gut Microbiota: A Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, K.A.; AlMuzafar, H.M. Alterations in lipid profile, oxidative stress and hepatic function in rat fed with saccharin and methyl-salicylates. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 6133–6144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Azeez, O.H.; Alkass, S.Y.; Persike, D.S. Long-Term Saccharin Consumption and Increased Risk of Obesity, Diabetes, Hepatic Dysfunction, and Renal Impairment in Rats. Medicina 2019, 55, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaziz, I.; Ashour Ael, R. Effect of saccharin on albino rats’ blood indices and the therapeutic action of vitamins C and E. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2011, 30, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.L.; Kirkland, J.J. The effect of sodium saccharin in the diet on caecal microflora. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1980, 18, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, M.; Zechman, J.M.; Brand, J.G.; Kare, M.R.; Sandovsky, V. Effects of sodium saccharin on the activity of trypsin, chymotrypsin, and amylase and upon bacteria in small intestinal contents of rats. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1985, 178, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, B.A.; Roberts, A.; Nestmann, E.R. Critical review of the current literature on the safety of sucralose. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 106, 324–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlDeeb, O.A.; Mahgoub, H.; Foda, N.H. Sucralose. Profiles Drug Subst. Excip. Relat. Methodol. 2013, 38, 423–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.; Santibañez, R.; Aguirre, C.; Galgani, J.E.; Garrido, D. Short-term impact of sucralose consumption on the metabolic response and gut microbiome of healthy adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 122, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, I. The development and applications of sucralose, a new high-intensity sweetener. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1994, 72, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Chi, L.; Gao, B.; Tu, P.; Ru, H.; Lu, K. Gut Microbiome Response to Sucralose and Its Potential Role in Inducing Liver Inflammation in Mice. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvetsky, A.C.; Rother, K.I. Trends in the consumption of low-calorie sweeteners. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 164, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Ge, L.; Lai, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, M.; Li, S.; Tian, J.; Yang, K.; et al. Association of soft drink and 100% fruit juice consumption with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular diseases mortality, and cancer mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 8908–8919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norbury, C.J.; Hickson, I.D. Cellular responses to DNA damage. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001, 41, 367–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiss, C.J. The apoptosis-necrosis continuum: Insights from genetically altered mice. Vet. Pathol. 2003, 40, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.; Sengupta, S.; Bandyopadhyay, T.K.; Bhattacharyya, A. Stevioside induced ROS-mediated apoptosis through mitochondrial pathway in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xia, Y.; Sui, X.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Steviol, a natural product inhibits proliferation of the gastrointestinal cancer cells intensively. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 26299–26308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatridis, N.; Kougioumtzi, A.; Vlataki, K.; Papadaki, S.; Magklara, A. Anti-Cancer Properties of Stevia rebaudiana; More than a Sweetener. Molecules 2022, 27, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaško, L.; Vašková, J.; Fejerčáková, A.; Mojžišová, G.; Poráčová, J. Comparison of some antioxidant properties of plant extracts from Origanum vulgare, Salvia officinalis, Eleutherococcus senticosus and Stevia rebaudiana. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2014, 50, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukiya, M.; Sawada, S.; Kikuchi, T.; Kushi, Y.; Fukatsu, M.; Akihisa, T. Cytotoxic and apoptosis-inducing activities of steviol and isosteviol derivatives against human cancer cell lines. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabe, Y.; Koike, I.; Yamamoto, T.; Hirai, M.; Kanai, A.; Furuhata, R.; Tsugawa, H.; Harada, E.; Sugase, K.; Hanadate, K.; et al. Glycyrrhizin Derivatives Suppress Cancer Chemoresistance by Inhibiting Progesterone Receptor Membrane Component 1. Cancers 2021, 13, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Sun, X.; Guo, X. Naturally occurring glycyrrhizin triterpene exerts anticancer effects on colorectal cancer cells via induction of apoptosis and autophagy and suppression of cell migration and invasion by targeting MMP-9 and MMP-2 expression. J. BUON 2020, 25, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nourazarian, S.M.; Nourazarian, A.; Majidinia, M.; Roshaniasl, E. Effect of Root Extracts of Medicinal Herb Glycyrrhiza glabra on HSP90 Gene Expression and Apoptosis in the HT-29 Colon Cancer Cell Line. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 8563–8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuli, H.S.; Garg, V.K.; Mehta, J.K.; Kaur, G.; Mohapatra, R.K.; Dhama, K.; Sak, K.; Kumar, A.; Varol, M.; Aggarwal, D.; et al. Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.)-Derived Phytochemicals Target Multiple Signaling Pathways to Confer Oncopreventive and Oncotherapeutic Effects. Onco Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 1419–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Khan, A.Q.; Lateef, A.; Rehman, M.U.; Tahir, M.; Ali, F.; Hamiza, O.O.; Sultana, S. Glycyrrhizic acid suppresses the development of precancerous lesions via regulating the hyperproliferation, inflammation, angiogenesis and apoptosis in the colon of Wistar rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Rehman, M.U.; Khan, A.Q.; Tahir, M.; Sultana, S. Glycyrrhizic acid suppresses 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon tumorigenesis in Wistar rats: Alleviation of inflammatory, proliferation, angiogenic, and apoptotic markers. Environ. Toxicol. 2018, 33, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ge, X.; Qu, H.; Wang, N.; Zhou, J.; Xu, W.; Xie, J.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, L.; Qin, Z.; et al. Glycyrrhizic Acid Inhibits Proliferation of Gastric Cancer Cells by Inducing Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 2853–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Dong, R.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Zheng, J.; Cui, S.; Ying, M.; Yang, B.; Cao, J.; et al. Neohesperidin prevents colorectal tumorigenesis by altering the gut microbiota. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 148, 104460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.H.; Kim, I.H.; Nam, T.J. Phloroglucinol induces apoptosis via apoptotic signaling pathways in HT-29 colon cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 32, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.; Bing, S.J.; Cho, J.; Ahn, G.; Kim, D.S.; Al-Amin, M.; Park, S.J.; Jee, Y. Phloroglucinol protects small intestines of mice from ionizing radiation by regulating apoptosis-related molecules: A comparative immunohistochemical study. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2013, 61, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Shen, S.; Verma, I.M. NF-κB, an active player in human cancers. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasti, A.N.; Nikolaki, M.D.; Synodinou, K.D.; Katsas, K.N.; Petsis, K.; Lambrinou, S.; Pyrousis, I.A.; Triantafyllou, K. The Effects of Stevia Consumption on Gut Bacteria: Friend or Foe? Microorganisms 2022, 10, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonkaewwan, C.; Burodom, A. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of stevioside and steviol on colonic epithelial cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3820–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Hussein, M.A.; Pierce, S.; Martens, C.; Shahagadkar, P.; Munirathinam, G. Oncopreventive and oncotherapeutic potential of licorice triterpenoid compound glycyrrhizin and its derivatives: Molecular insights. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 178, 106138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Fu, J.; Song, X.; Shi, Q.; Su, C.; Song, E.; Song, Y. Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone down-regulates MyD88-dependent and -independent signaling by inhibiting endotoxin-induced trafficking of TLR4 to lipid rafts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Song, X.; Fu, J.; Su, C.; Xia, X.; Song, E.; Song, Y. Artificial sweetener neohesperidin dihydrochalcone showed antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptosis effects against paraquat-induced liver injury in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallaert, W.; Taylor, S.R.; Kedziora, K.M.; Taylor, C.D.; Sobon, H.K.; Young, C.L.; Limas, J.C.; Varblow Holloway, J.; Johnson, M.S.; Cook, J.G.; et al. The molecular architecture of cell cycle arrest. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2022, 18, e11087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.K.; Shah, M.A. Targeting the cell cycle: A new approach to cancer therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 9408–9421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, X.L.; Nan, Y.; Du, Y.H.; Yang, Y.; Lu, D.D.; Zhang, J.F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Niu, Y.; et al. 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid inhibits proliferation of gastric cancer cells through regulating the miR-345-5p/TGM2 signaling pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 3622–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqui, A.; Khan, F.; Khan, I.; Ansari, I.A. Glycyrrhizin induces reactive oxygen species-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle arrest at G(0)/G(1) in HPV18(+) human cervical cancer HeLa cell line. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavanello, S.; Moretto, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Alicandro, G. Non-sugar sweeteners and cancer: Toxicological and epidemiological evidence. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 139, 105369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shil, A.; Olusanya, O.; Ghufoor, Z.; Forson, B.; Marks, J.; Chichger, H. Artificial Sweeteners Disrupt Tight Junctions and Barrier Function in the Intestinal Epithelium through Activation of the Sweet Taste Receptor, T1R3. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Guo, M.; Tan, Y.; Qin, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, M. Sucralose Promotes Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer Risk in a Murine Model Along With Changes in Microbiota. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Hiramoto, K.; Ma, N.; Yoshikawa, N.; Ohnishi, S.; Murata, M.; Kawanishi, S. Glycyrrhizin Attenuates Carcinogenesis by Inhibiting the Inflammatory Response in a Murine Model of Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qurratul, A.; Khan, S.A. Artificial sweeteners: Safe or unsafe? J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2015, 65, 225–227. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A. The safety and regulatory process for low calorie sweeteners in the United States. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 164, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, G.A.; Heintz, M.M.; Borghoff, S.J.; Doepker, C.L.; Wikoff, D.S. Lack of potential carcinogenicity for steviol glycosides—Systematic evaluation and integration of mechanistic data into the totality of evidence. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 150, 112045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, I.A.; Chappell, G.A.; Wikoff, D.S. Overall lack of genotoxic activity among five common low- and no-calorie sweeteners: A contemporary review of the collective evidence. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2021, 868–869, 503389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Overy, A.J.; Büsselberg, D. Phytochemicals and Gastrointestinal Cancer: Cellular Mechanisms and Effects to Change Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Liskova, A.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D. Enzymatic Metabolism of Flavonoids by Gut Microbiota and Its Impact on Gastrointestinal Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Koklesova, L.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D. Immunomodulation by Gut Microbiome on Gastrointestinal Cancers: Focusing on Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samec, M.; Mazurakova, A.; Lucansky, V.; Koklesova, L.; Pecova, R.; Pec, M.; Golubnitschaja, O.; Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Caprnda, M.; Gaspar, L.; et al. Flavonoids attenuate cancer metabolism by modulating Lipid metabolism, amino acids, ketone bodies and redox state mediated by Nrf2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 949, 175655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaybullin, R.N.; Zhang, M.; Fu, J.; Liang, X.; Li, T.; Katritzky, A.R.; Okunieff, P.; Qi, X. Design and synthesis of isosteviol triazole conjugates for cancer therapy. Molecules 2014, 19, 18676–18689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sweetener Type | Targeted Metabolites/Proteins/Genes/Pathway | Targeted Disease/Tissue | Mechanism of Action | Methods of Testing | Model Used | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo | In Vitro | ||||||

| Steviol glycosides | Apoptosis Cellular proliferation |

Gastric cancer Colon cancer |

- Steviol inhibited mitochondrial apoptotic pathway - The administration of steviol-activated p21 and p53 - It increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio |

MTT assay Western blot miRNA analysis Flow cytometry |

- HGC-27 cells - Caco-2 cells - HCT-8 cells - HCT 116 cells - MKN-45 cells - MGC-803 cells |

[67] | |

| Cytotoxic Apoptosis |

Stomach cancer | - Induced apoptosis cell death - Increased cytotoxicity |

MTT assay Apoptotic assays Flow cytometry |

- AZ521 cells | [70] | ||

| Apoptosis | Colon cancer | - The administration of steviol decreased cell viability in colorectal cancer cell line | MTT assay Bicinchoninic acid assay |

- Wistar rats | - Caco-2 cells | [69] | |

| Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone |

Apoptosis Angiogenesis |

Colon cancer | - The administration of Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone induced apoptosis and blocked angiogenesis - The administration of Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone altered the gut microbiota |

PCR Western blot Luciferase assay Cell survival assay TUNEL assay |

- C57BL/6 J - APCmin/+ mice |

- HCT116 cells - SW480 cells - CT26 cells |

[78] |

| Glycyrrhizin | Apoptosis | Colon cancer | - The administration of glycyrrhizin inhibited cellular growth in a dose-dependent manner - It also induced apoptosis through nuclear fragmentation and chromatin condensation |

Transmission electron microscopy Apoptotic assay Cell invasion assay Western blot |

- SW48 cells | [72] | |

| Apoptosis Inflammation |

Colon cancer | - Treatment with glycyrrhizic acid suppressed the development of early markers of colon cancer - It also suppressed the development of precancerous lesions - Suppressed the immunostaining of NF-Kb and p65 |

Immunohistochemical staining ELISA Aberrant Crypt Foci (ACF) assay |

- Albino rats | [75] | ||

| Inflammation | Colon cancer | - The administration of glycyrrhizin reduced the plasma level of IL-6 and TNF-a - Glycyrrhizin significantly reduced the expression of 8- NitroG, 8-OxodG, COX-2, and HMGB1 |

ELISA Immunohistochemical staining |

- ICR mice | [95] | ||

| Apoptosis Inflammation |

Colon cancer | - Treatment with glycyrrhizic acid reduced the expression of NF-kB and COX-2 - It enhanced the expression of cleaved caspase 3 - It also reduced mast cells infiltration |

ELISA Immunohistochemical staining Mast cell staining |

- Albino rats | [76] | ||

| Apoptosis Cellular proliferation |

Gastric cancer | - Treatment with glycyrrhizic acid downregulated the level of G1 phase-related proteins in a dose and time-dependent manner - It also upregulated the levels of Bax, cleaved PARP, and pro-caspase-3, -8, -9 |

CCK-8 assay Apoptotic assay EdU assay Cell cycle assay Western blot |

- MGC-803 cells - BGC-823 cells - SGC-7901 cells |

[77] | ||

| Saccharin | Apoptosis Cell viability |

Intestinal epithelium | - The administration of saccharin at a lower concentration (up to 100 uM) induced apoptosis, while at a higher concentration (<=1000 uM) induced cell death - Saccharin administration decreases cell viability and disrupts the intestinal epithelial barrier through the binding to the sweet taste receptors |

RT-PCR Annexin V assay siRNA and cDNA Transfections ROS assay ELISA |

- C57BL/6 mice | - Caco-2 cells | [93] |

| Sucralose | Inflammation | Colitis-associated colorectal cancer | - Sucralose significantly increased the number and size of colorectal tumor - The administration of sucralose significantly increased expressions of TNFa and TLR4 - Sucralose significantly increased the abundance of Firmicures, Clostridium symbiosum, and Peptostreptococcus anaerobius while it decreased the abundance of Solobacterium moorei and Bifidobacteria |

Spectrophotometry qRT-PCR Western blot ELISA |

- C57BL/6 mice | [94] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).