Submitted:

19 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bucaramanga Metropolitan Area (BMA) in context

2.2. Study approach

2.3. Environmental health topics in newspaper and scientific articles

2.4. Survey of citizen´s perceptions

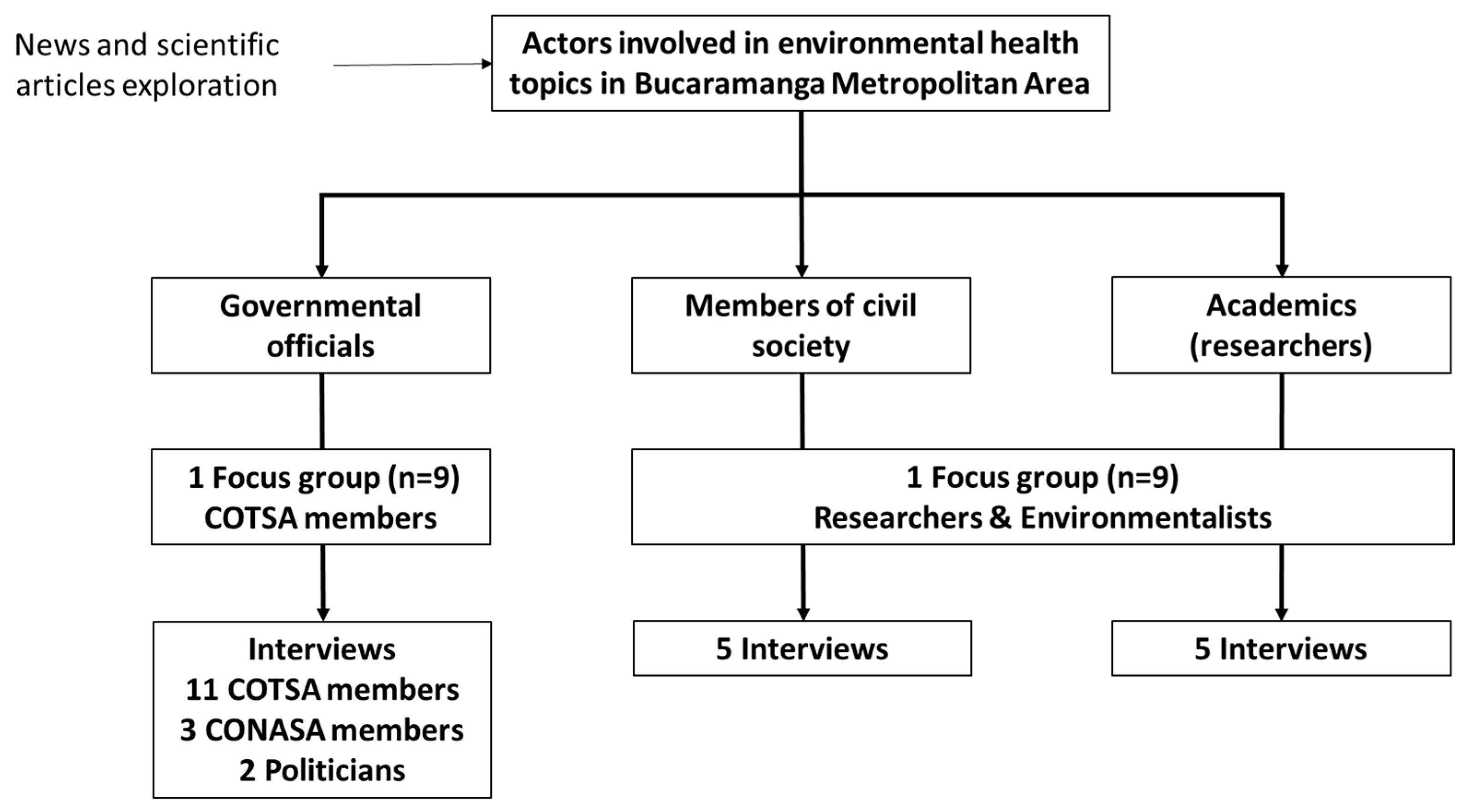

2.5. Interviews and focus groups with key stakeholders

2.6. Ethical considerations

3. Results

3.1. Findings from newspaper and scientific articles

3.2. Survey of citizen´s perceptions

3.3. Interviews and focus groups with key stakeholders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolf, M.J.; Emerson, J.W.; Esty, D.C.; de Sherbinin, A.; Wendling, Z.A., et al. 2022 Environmental Performance Index. Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy: New Haven, CT, USA, 2022.

- Rodríguez-Villamizar, L.A.; González, B.E.; Vera, L.M.; Patz, J.; Bautista, L.E. Environmental and Occupational Health Research and Training Needs in Colombia: A Delphi Study. Biomedica 2015, 35(supl.2):58-65. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rincón, M.P.; Peralta-Ardila, M.; Vélez-Torres, I.; Méndez, F. Conflicto Armado Interno y Ambiente en Colombia: Análisis desde los Conflictos Ecológicos, 1960-2016. J Pol Ecol 2022, 29:672-703. [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, J.; Milanese, J.P.; Valencia, I.H.; Wolff, J. Local Competitive Authoritarianism and Post-Conflict Violence. An Analysis of the Assassination of Social Leaders in Colombia. Int Interact 2022, 49:237-67. [CrossRef]

- Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social (CONPES). Documento. 3550. Lineamientos para la formulación de la política integral de salud ambiental con énfasis en los componentes de calidad de aire, calidad de agua y seguridad química. República de Colombia, Departamento Nacional de Planeación, Bogotá, 2008.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Documento técnico de avances de la Política Integral de Salud Ambiental, el CONPES 3550/2008 y los Consejos Territoriales de Salud Ambiental – COTSA. Bogotá DC, 2014.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Plan Decenal de Salud Pública 2012-2021: La salud en Colombia la construyes tú. Bogotá DC, 2013.

- Lenihan, H.; McGuirk, H.; Murphy, K.R. Driving Innovation: Public Policy and Human Capital. Res Pol 2019, 48:103791. [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L. Public Policy and Behavior Change. Public Adm Rev 2019, 79:925-30. [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Villamizar, R.; Mejía-Jerez, A.; Acevedo-Tarazona, A. Territorialidades y Representaciones Sociales Superpuestas en la Dicotomía Agua vs. Oro: El Conflicto Socioambiental por Minería Industrial en el Páramo de Santurbán. Territorios 2020, 42-Esp:1-25. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, N.E.; Restrepo, r.; Cardeñosa, M. Índices de Contaminación para Caracterización de Aguas Continentales y Vertimientos. Formulaciones. CT&F: Ciencia, Tecnología y Futuro, 1999; 1:89–99.

- Gómez-Monsalve, M.; Domínguez, I.C.; Yan, X.; Ward, S.; Oviedo-Ocaña, E.R. Environmental Performance of a Hybrid Rainwater Harvesting and Greywater Reuse System: A Case Study on a High Water Consumption Household in Colombia. J Clean Prod 2022, 345:131125. [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, J.C.; Morales, E.; Uribe Delgado, N.; Flórez, A.A. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastrointestinal Parasites in Backyard Pigs Reared in the Bucaramanga Metropolitan Area, Colombia Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2020, 29:e015320. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Manrique, F.M.; Vesga-Gómez, C.; Angulo-Silva, M.L. Empoderamiento para la Prevención y Control del Dengue. Rev Salud Pública (Bogota) 2010, 12:798-806. [CrossRef]

- Hernández Jaruffe, L.A.; Zárate, A.; Díaz Martínez, L.A. Factores de Riesgo para Infección Respiratoria Aguda con Énfasis en la Contaminación Ambiental. Salud UIS 1993, 21:7–15. https://revistas.uis.edu.co/index.php/revistasaluduis/article/view/10438.

- Rodríguez-Villamizar, L.A.; Castro-Ortiz, H.; Rey-Serrano, J.J. The Effects of Air Pollution on Respiratory Health in Susceptible Populations: A Multilevel Study in Bucaramanga, Colombia. Cad Saúde Publica 2012, 28:749-57. [CrossRef]

- Valbuena-García, A.M.; Rodríguez-Villamizar, L.A.; Uribe-Pérez, C.J.; Moreno-Corzo, F.E.; Ortiz-Martínez, R.G. A Spatial Analysis of Childhood Cancer and Industrial Air Pollution in a Metropolitan Area of Colombia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2020, 67:e28353. [CrossRef]

- Tortola, PD. Clarifying Multilevel Governance. Eur J Pol Res 2017, 56:234–50. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rodríguez, J.; Salgado-Meza, P.A.; Asorey, H.; Núñez, L.A.; Núñez-Castiñeyra, A.; Sarmiento-Cano, C.; Suárez-Durán, M. RACIMO@Bucaramanga: A Citizen Science Project on Data Science and Climate Awareness. arXiv:2203.05431. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Salud, Observatorio Nacional de Salud. Carga de Enfermedad Ambiental. Décimo Informe Técnico Especial. Instituto Nacional de Salud; Bogotá, D.C., 2018.

- Stanaway, J.D.; Afshin, A.; Gakidou, E.; Lim, S.S.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Comparative Risk Assessment of 84 Behavioural, Environmental and Occupational, and Metabolic Risks or Clusters of Risks for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392:1923–94. [CrossRef]

- Katz, AR. Noncommunicable Diseases: Global Health Priority or Market Opportunity? An Illustration of the World Health Organization at its Worst and at its Best. Int J Health Serv 2013, 43:437-458. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. The Global Burden of Disease Study: A Useful Projection of Future Global Health? Public Health Med 2000, 22:518-524. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, R.M.; Sellers, S.P.; Baker, M.G.; Kalman, R.B.; Frostad, J.; Suter, M.K.; et al. Improving and Expanding Estimates of the Global Burden of Disease Due to Environmental Health Risk Factors. Environ Health Perspect 2019, 127:105001. [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.; Gaudin, S.; Corvalán, C.; Earle, A.J.; Hanssen, O.; Prüss-Ustun, A.; et al. The Case for Public Financing of Environmental Common Goods for Health. Health Syst Ref 2019, 5:366-381. [CrossRef]

- Belalcazar-Cerón, L.C.; Dávila, P.; Rojas, A.; Guevara-Luna, M.A.; Acevedo, H.; Rojas, N. Effects of Fuel Change to Electricity on PM2.5 Local Levels in the Bus Rapid Transit System of Bogota. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021, 28:68642-68656. [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, G.A.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Medaglia, A.L.; Cabrales, S.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Quistberg, D.A.; López, S. Bicycle Safety in Bogotá: A Seven-Year Analysis of Bicyclists' Collisions and Fatalities. Accid Anal Prev 2020, 144:105596. [CrossRef]

- Milanes, C,B.; Martínez-González, M.B.; Moreno-Gómez, J.; Saltarín, J.A.; Suarez, A.; Padilla-Llano, S.E.; et al. Multiple Hazards and Governance Model in the Barranquilla Metropolitan Area, Colombia. Sustainability 2021, 13:2669. [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Bonilla, L.H. La Investigación Acción Participativa: Un Camino para Construir el Cambio y la Transformación Social. Ediciones Desde Abajo: Bogotá, DC; 2017.

- Molina-Orjuela, D.E.; Rojas, A. ¿Se está Construyendo Paz Ambiental Territorial con los Pueblos Ancestrales de Puerto Nariño, Amazonas-Colombia?: Una Mirada desde la Ecología Social y el Buen Vivir. Reflexión Política, 2019, 21:162–173. [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, A.; Furumo, P.R.; Moss, S.; Figot Kuthy, A.G.; García Aguirre, D.; Mandle, L.; et al. Colombian Biodiversity is Governed by a Rich and Diverse Policy Mix. Nat Ecol Evol 2023, 7:382–392. [CrossRef]

- Finkel, A.M. Perceiving others' Perceptions of Risk: Still a Task for Sisyphus. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008, 1128:121-37. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.; Freudenburg, W. Gender and Environmental Risk Concerns A Review and Analysis of Available Research. Environ Behav 1996, 28,302–339. [CrossRef]

- Bolte, G.; Jacke, K.; Groth, K.; Kraus, U.; Dandolo, L.; Fiedel, L.; et al. Integrating sex/gender into environmental health research: development of a conceptual framework. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18:12118. [CrossRef]

- Gamboa-Arévalo, A.P. Género y Gestión Ambiental en los Humedales de Bogotá. Prospectiva. Rev Trab Soc Interv Soc 2019, 28:169–201. [CrossRef]

- Klier, G.; Núñez, P.G. Verde que te Quiero Verde: Una Mirada Feminista para la Conservación de la Biodiversidad. Intropica. [CrossRef]

| Odor annoyance & Water pollution |

Noise | Air pollution | |

| Year publication | |||

| 2016 | 92 | 52 | 37 |

| 2017 | 105 | 86 | 45 |

| 2018 | 117 | 66 | 40 |

| 2019 | 26 | 46 | 42 |

| 2020 (until April) | 4 | 6 | 23 |

| Actions to solve problems (examples) | |||

| Actors | Environmental agency, mayor's offices, and civil society | Civil society | Universities and CDMB |

| Specific action | Cleaning of water sources Creek cleaning and environmental education |

Complaints, mobilizations, and lawsuits | Scientific studies and dissemination of results |

| Debate on landfill issues |

| Variable | Yes | No | No response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of policies and regulations | |||

| Environmental protection | 48.0 | 46.9 | 5.1 |

| Protection of water sources | 31.6 | 62.2 | 6.2 |

| Air quality management | 36.7 | 55.1 | 8.2 |

| Recycling and solid waste management | 62.2 | 36.7 | 1.1 |

| Residential waste collection | 56.1 | 37.8 | 6.1 |

| Management of waste generated at home | 53.1 | 43.9 | 3.0 |

| Noise management | 35.7 | 58.2 | 6.1 |

| Vehicle gas emission control | 40.8 | 52.0 | 7.2 |

| Contamination control of commercial establishments | 26.5 | 64.3 | 9.2 |

| Pro-environmental culture | 25.5 | 67.3 | 7.2 |

| Encourage reforestation | 22.4 | 70.4 | 7.2 |

| Citizen experience in environmental governance | |||

| You know institutions in charge of environmental management | 72.4 | 23.5 | 4.1 |

| Participation in the generation of environmental policy | 10.2 | 87.8 | 2.0 |

| You have been asked for your opinion on environmental issues | 17.3 | 80.6 | 2.1 |

| Has received information for the generation of environmental policies | 18.4 | 79.6 | 2.0 |

| Citizen participation in the generation of environmental policies is important | 93.9 | 4.1 | 2.0 |

| If you are invited, you would participate in the generation of environmental policies | 88.8 | 4.1 | 7.1 |

| Decisions on environmental management d must be discussed and agreed between the government and citizens | 98.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Control and surveillance | “When, for example, the CDMB requests an accompaniment to verify an odor problem with a farm, that does not happen every day. But when it happens, the ICA veterinarian goes to accompany them." (Int-11) “The truth is that I have not had very good articulation with the environmental authorities, we have not worked very well, it is a sad reality.” (Int-5) |

| Information management | "What we have had to do is demand from the State entities, so we have requested information from the different health entities such as the Bucaramanga Municipal Health Secretariat and the Departmental Health Secretariat." (Int-1) "Frequently we use, let's say, official or governmental air information, for example, so I have contact with the environmental, local, national and health authorities." (Int-8) |

| Development of research in environmental health. | “From coordination, we execute inter-administrative agreements with the academy, with the UPB, with the UDES, UIS, Pamplona, Santo Tomás, with the Colombian Meteorological Service in which we generate environmental research projects, taking into account the environmental priorities that exist in the region. The CDMB has an environmental research plan, which has several strategic lines, and we have research projects that we need to develop and those priority research projects are the ones that we develop with the academy.” (Int-4) “With the UIS, we have supported each other since 2007 in various phases of research on air quality and health, in different projects [...] We already had the first meeting this month; The sites where the different systems to be measured have been chosen. Here PM2.5 will be measured, in different strategic sites in Bucaramanga, ozone will also be measured..." (Int-4) |

| Coordination of activities | "The municipalities [of the BMA] have their own environmental health officers from their mayors' offices, but the other 82 remaining municipalities that are category 4, 5 and 6, those are the responsibility of the Department." (Int-5) “Here at the CDMB, we only know how environmental health is being managed when the Ministry of Health issues the reports [...] There is no more direct communication, each institution does its part according to what corresponds to them.” (Int-4) |

| More pro-environmental awareness | “… the pressure that there is towards the rulers, commitment of the same civil society, in reducing contaminants, trying to reduce water consumption, generating minimum waste; in other words, everything, between the public and the private, civil society, educational institutions have also collaborated a lot, there is a lot of commitment in recent years, it has been seen that young people are more committed.” (Int-7) |

| Increased data availability | “[about air data] there is information that was not available before and had to be managed in a particular way, waiting for them to consolidate it; now there is information that is more freely available, others not so much but it can be requested and accessed…” (Int-15) |

| Less technological and workforce capacity | “With the CDMB, many years ago, we had a study group on air quality that we moved in [scientific] congresses. The CDMB managed the equipment of the air quality system well, but due to economic problems that network fell down. It was a national example because they had automatic equipment and they had professionals who could manage the network" (Int-4) |

| Political disputes with technical consequences | “But here, too, each one does his own thing; look at the fight between the AMB and the CDMB a few years ago, instead of working together, many times the authorities fight among themselves, so there is no such integration” (Int-14) |

| Growth with environmental deterioration | “The results are not good, the processes have to be discussed with the results. We are already in the 21st century and Bucaramanga treats only 10% of its wastewater, to give you an example. And the city grows, more wastewater is produced, more problems occur, deforestation increases because in Bucaramanga in the 70s and 80s it was much greener, but that is being lost.” (Int-2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).