Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

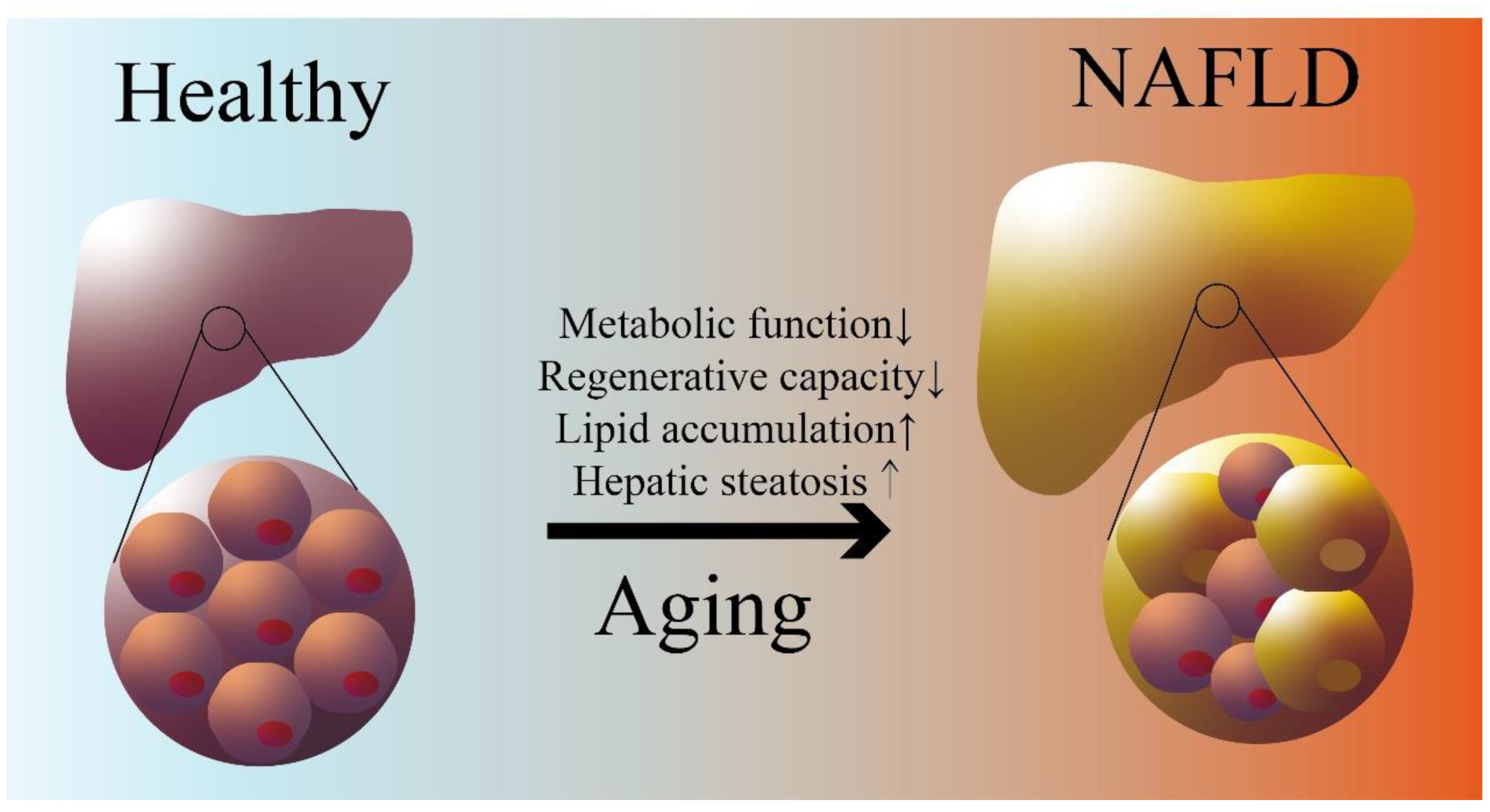

2. Aging is A Risk Factor for NAFLD

2.1. Aging and Liver Aging

2.2. Aging-associated Impaired Lipid Metabolism and NAFLD

3. CRP is A Potential Biomarker for Aging associated NAFLD

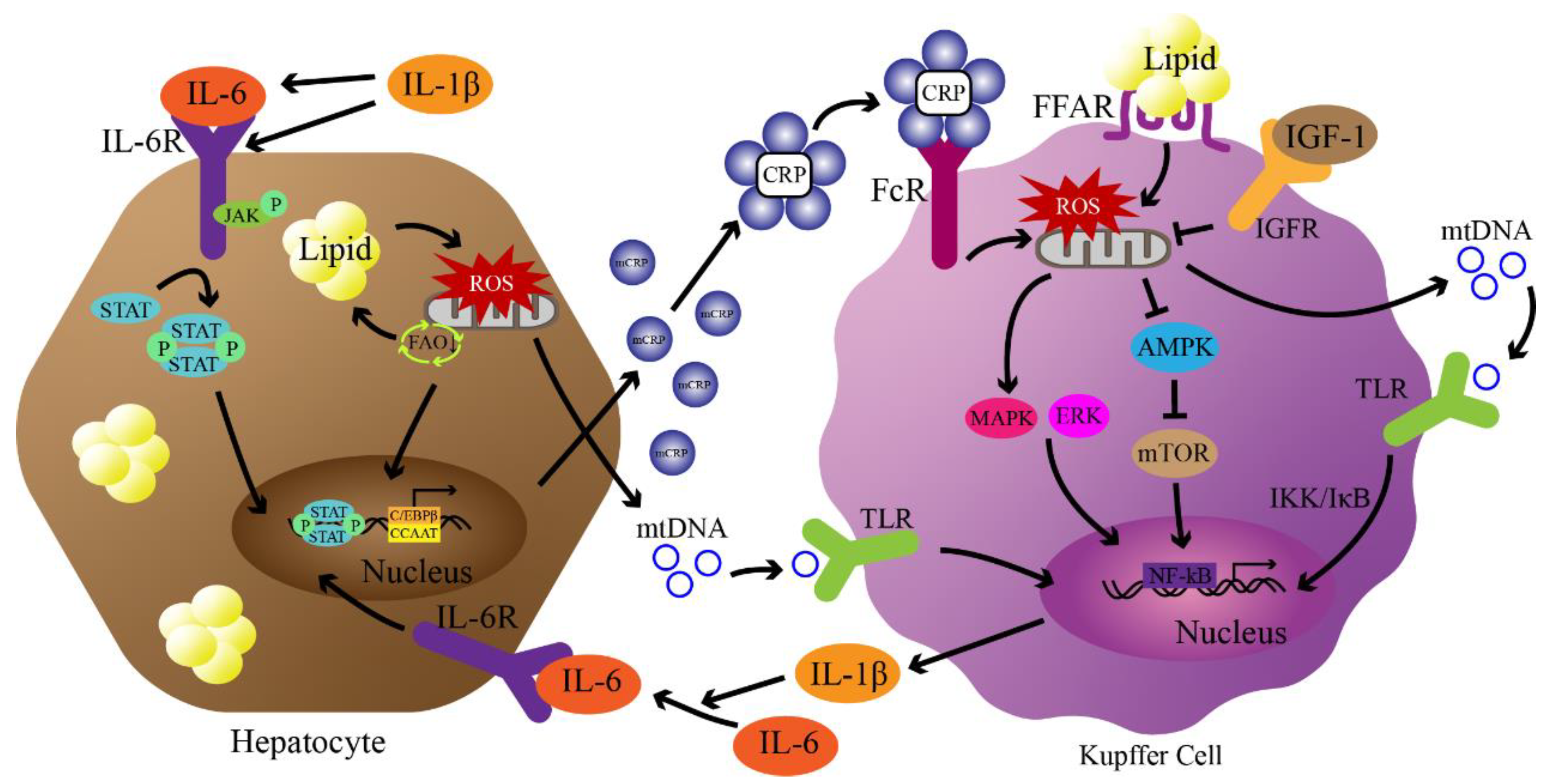

3.1. CRP definition, expression regulation and function

3.2. CRP, Insulin signaling pathway and aging-associated NAFLD

3.3. CRP, mitochondria dysfunction and aging-associated NAFLD

3.4. CRP, NF-κB pathway and aging-associated NAFLD

4. CRP as a potential therapeutic target for aging associated NAFLD (Table 1)

| CRP-lowering Strategies | Drugs/Methods | Mechanisms | Effectiveness | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caloric restriction and Antioxidation | MedDiet, Dietary restriction, Astaxanthin and β-Cryptoxanthin |

Energy intake reduction, Anti-oxidative stress, Inflammatory factors reduction |

Weight Loss, Increased Lifespan, Reduced risk of NAFLD |

lacking long-term clinical evidence, Requiring long-time maintenance |

| CRP-lowering drugs | Pioglitazone, Statins, Vitamin E, MitoQ |

PPARγ agonists, HMG CoA reductase inhibitors, Anti-oxidation |

Reducing steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis, Anti-inflammation |

Drug inefficiency, Nonspecific binding, Immunosuppression |

| CPR Adsorption Technology | CPR Apheresis | Using adsorbent specifically binding CRP in serum | Effectively reducing CRP acute infection, Recyclable and no side effects |

Safety and efficacy evaluations needed in the treatment of NAFLD |

4.1. Caloric restriction and Antioxidation

4.2. CRP-lowering drugs for NAFLD treatment

4.3. CPR Adsorption Technology

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, W.; Goodkind, D.; Kowal, P. R., An aging world: 2015. United States Census Bureau Washington, DC: 2016.

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M. A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. , The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M. A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. , Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J. V.; Mark, H. E.; Anstee, Q. M.; Arab, J. P.; Batterham, R. L.; Castera, L.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Crespo, J.; Cusi, K.; Dirac, M. A. , Advancing the global public health agenda for NAFLD: a consensus statement. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2022, 19, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, B. E. , NASH: regulatory considerations for clinical drug development and US FDA approval. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2022, 43, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassir, F. , NAFLD: Mechanisms, treatments, and biomarkers. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Huang, Y.; Bao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shi, D.; Liu, F.; Gao, Z.; Yu, X. , Prevalence and factors associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Shanghai work-units. BMC gastroenterology 2012, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ng, C. H.; Quek, J.; Chan, K. E.; Tan, C.; Zeng, R. W.; Yong, J. N.; Tay, H.; Tan, D. J. H.; Lim, W. H. , The growing prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), determined by fatty liver index, amongst young adults in the United States. A 20-year experience. Metabol Target Organ Damage 2022, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S. A.; Schattenberg, J. M. , NAFLD in the Elderly. Clinical interventions in aging 2021, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, H. K.; Weiskirchen, S.; Weiskirchen, R. , Current status in testing for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Cells 2019, 8, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.; Hillersdal, L. , Aging biomarkers and the measurement of health and risk. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 2021, 43, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkin, F.; Mamoshina, P.; Aliper, A.; de Magalhães, J. P.; Gladyshev, V. N.; Zhavoronkov, A. , Biohorology and biomarkers of aging: Current state-of-the-art, challenges and opportunities. Ageing Research Reviews 2020, 60, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oruc, N.; Ozutemiz, O.; Yuce, G.; Akarca, U. S.; Ersoz, G.; Gunsar, F.; Batur, Y. , Serum procalcitonin and CRP levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a case control study. BMC gastroenterology 2009, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Porwal, Y. C.; Dev, N.; Kumar, P.; Chakravarthy, S.; Kumawat, A. , Association of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Asian Indians: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2020, 9, 390. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Fung, E.; Xu, A.; Lan, H. Y. , C-reactive protein and ageing. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology 2017, 44, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassale, C.; Batty, G. D.; Steptoe, A.; Cadar, D.; Akbaraly, T. N.; Kivimäki, M.; Zaninotto, P. , Association of 10-year C-reactive protein trajectories with markers of healthy aging: findings from the English longitudinal study of aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2019, 74, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sproston, N. R.; Ashworth, J. J. , Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sławińska, N.; Krupa, R. , Molecular aspects of senescence and organismal ageing—DNA damage response, telomeres, inflammation and chromatin. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodig, S.; Čepelak, I.; Pavić, I. , Hallmarks of senescence and aging. Biochemia medica 2019, 29, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulos, G. K., Liver regeneration. The Liver: Biology and Pathobiology 2020, 566-584.

- Heinke, P.; Rost, F.; Rode, J.; Trus, P.; Simonova, I.; Lázár, E.; Feddema, J.; Welsch, T.; Alkass, K.; Salehpour, M. , Diploid hepatocytes drive physiological liver renewal in adult humans. Cell Systems 2022, 13, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, K. P.; Baur, O.; Verheij, J.; Bennink, R. J.; van Gulik, T. M. , Liver function declines with increased age. Hpb 2016, 18, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, J. , Understanding the unique microenvironment in the aging liver. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K. W. , Advances in understanding of the role of lipid metabolism in aging. Cells 2021, 10, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V. W.-S.; Wong, G. L.-H.; Woo, J.; Abrigo, J. M.; Chan, C. K.-M.; Shu, S. S.-T.; Leung, J. K.-Y.; Chim, A. M.-L.; Kong, A. P.-S.; Lui, G. C.-Y. , Impact of the new definition of metabolic associated fatty liver disease on the epidemiology of the disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2021, 19, 2161–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koehler, E. M.; Schouten, J. N. L.; Hansen, B. E.; van Rooij, F. J. A.; Hofman, A.; Stricker, B. H.; Janssen, H. L. A. , Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the elderly: results from the Rotterdam study. Journal of hepatology 2012, 57, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureddin, M.; Yates, K. P.; Vaughn, I. A.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B. A.; Sanyal, A. J.; McCullough, A.; Merriman, R.; Hameed, B.; Doo, E.; Kleiner, D. E. , Clinical and histological determinants of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and advanced fibrosis in elderly patients. Hepatology 2013, 58, 1644–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtkooper, R. H.; Argmann, C.; Houten, S. M.; Cantó, C.; Jeninga, E. H.; Andreux, P. A.; Thomas, C.; Doenlen, R.; Schoonjans, K.; Auwerx, J. , The metabolic footprint of aging in mice. Sci Rep 2011, 1, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, Y.; Liu, S.; Ye, L.; Zhang, R. , A new NASH model in aged mice with rapid progression of steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Plos one 2023, 18, e0286257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Kang, H.; Choi, H.; Choi, W.; Jun, H. S. , Reactive oxygen species-induced changes in glucose and lipid metabolism contribute to the accumulation of cholesterol in the liver during aging. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Miwa, S.; Tchkonia, T.; Tiniakos, D.; Wilson, C. L.; Lahat, A.; Day, C. P.; Burt, A.; Palmer, A.; Anstee, Q. M. , Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nature communications 2017, 8, 15691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillett, W. S.; Francis Jr, T. , Serological reactions in pneumonia with a non-protein somatic fraction of pneumococcus. The Journal of experimental medicine 1930, 52, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, R. J.; Schott, M. B.; Casey, C. A.; Tuma, P. L.; McNiven, M. A. , The cell biology of the hepatocyte: A membrane trafficking machine. Journal of Cell Biology 2019, 218, 2096–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knolle, P. A. , Staying local—Antigen presentation in the liver. Current opinion in immunology 2016, 40, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Xu, M.-J.; Gao, B. , Hepatocytes: a key cell type for innate immunity. Cellular & molecular immunology 2016, 13, 301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, M.; Samols, D.; Kushner, I. , STAT3 Participates in Transcriptional Activation of the C-reactive Protein Gene by Interleukin-6 (∗). Journal of Biological Chemistry 1996, 271, 9503–9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwa, D. N.; Pathak, A.; Agrawal, A. , IL-6 regulates induction of C-reactive protein gene expression by activating STAT3 isoforms. Molecular immunology 2022, 146, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Cha-Molstad, H.; Samols, D.; Kushner, I. , Transactivation of C-reactive protein by IL-6 requires synergistic interaction of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ) and Rel p50. The Journal of Immunology 2001, 166, 2378–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, F.; Torzewski, J.; Kamenz, J.; Veit, K.; Hombach, V.; Dedio, J.; Ivashchenko, Y. , Interleukin-1β stimulates acute phase response and C-reactive protein synthesis by inducing an NFκB-and C/EBPβ-dependent autocrine interleukin-6 loop. Molecular immunology 2008, 45, 2678–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, M.; Khechai, F.; Ollivier, V.; Ternisien, C.; Bridey, F.; Hakim, J.; de Prost, D. , Interleukin-10 and pentoxifylline inhibit C-reactive protein-induced tissue factor gene expression in peripheral human blood monocytes. FEBS Lett 1994, 356, 86–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Agrawal, A. , Evolution of C-reactive protein. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, S.; Samols, D.; Dailey, P. , Two carboxylesterases bind C-reactive protein within the endoplasmic reticulum and regulate its secretion during the acute phase response. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1994, 269, 24496–24503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, W., Multiple Faces of C-Reactive Protein: Structure–Function Relationships. Clinical Significance of C-reactive Protein 2020, 1-34.

- Torzewski, M. , C-reactive protein: friend or foe? Phylogeny from heavy metals to modified lipoproteins and SARS-CoV-2. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braig, D.; Nero, T. L.; Koch, H.-G.; Kaiser, B.; Wang, X.; Thiele, J. R.; Morton, C. J.; Zeller, J.; Kiefer, J.; Potempa, L. A. , Transitional changes in the CRP structure lead to the exposure of proinflammatory binding sites. Nature communications 2017, 8, 14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepys, M. B.; Hirschfield, G. M. , C-reactive protein: a critical update. The Journal of clinical investigation 2003, 111, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, L.; Cimmino, G.; Loffredo, F.; De Palma, R.; Abbate, G.; Calabrò, P.; Ingrosso, D.; Galletti, P.; Carangio, C.; Casillo, B. , C-reactive protein is released in the coronary circulation and causes endothelial dysfunction in patients with acute coronary syndromes. International journal of cardiology 2011, 152, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H. , Regulation of C-reactive protein conformation in inflammation. Inflammation Research 2019, 68, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Y.-y.; Yao, Y.-m. , The clinical significance and potential role of C-reactive protein in chronic inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaka, T. P.; Hombach, V.; Torzewski, J. , C-reactive protein–mediated low density lipoprotein uptake by macrophages: implications for atherosclerosis. Circulation 2001, 103, 1194–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, I. N.; White, M.; Hoeksema, M.; Deluna, X.; Hartshorn, K. , Histone H4 potentiates neutrophil inflammatory responses to influenza A virus: Down-modulation by H4 binding to C-reactive protein and Surfactant protein D. PloS One 2021, 16, e0247605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Y.; Tang, Z.-M.; Wang, Z.; Lv, J.-M.; Liu, X.-L.; Liang, Y.-L.; Cheng, B.; Gao, N.; Ji, S.-R.; Wu, Y. , C-reactive protein protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury by preventing complement overactivation. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2022, 13, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, M.; Mawatari, H.; Fujita, K.; Iida, H.; Yonemitsu, K.; Kato, S.; Takahashi, H.; Kirikoshi, H.; Inamori, M.; Nozaki, Y.; Abe, Y.; Kubota, K.; Saito, S.; Iwasaki, T.; Terauchi, Y.; Togo, S.; Maeyama, S.; Nakajima, A. , High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is an independent clinical feature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and also of the severity of fibrosis in NASH. Journal of Gastroenterology 2007, 42, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, E. T. H.; Willerson, J. T. , Coming of age of C-reactive protein: using inflammation markers in cardiology. Circulation 2003, 107, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Szmitko, P. E.; Ridker, P. M. , C-reactive protein comes of age. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine 2005, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liang, P.; Chen, J.; Fu, S.; Liu, B.; Feng, M.; Lin, B.; Lee, B.; Xu, A.; Lan, H. Y. , The baseline levels and risk factors for high-sensitive C-reactive protein in Chinese healthy population. Immunity & Ageing 2018, 15, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz, B. A.; Corrada, M. M.; Kawas, C. H. , High levels of serum C-reactive protein are associated with greater risk of all-cause mortality, but not dementia, in the oldest-old: results from The 90+ Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009, 57, 641–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Kumar, R.; Lin, S. , Serum high-sensitive C-reactive protein is a simple indicator for all-cause among individuals with MAFLD. Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marušić, M.; Paić, M.; Knobloch, M.; Liberati Pršo, A.-M. , NAFLD, insulin resistance, and diabetes mellitus type 2. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai, N.; Ferrucci, L. , Insulin Resistance and Aging: A Cause or a Protective Response? The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2012, 67, 1329–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alissa, E. M.; Algarni, S. A.; Khaffji, A. J.; Al Mansouri, N. M. , Role of inflammatory markers in polycystic ovaries syndrome: In relation to insulin resistance. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2021, 47, 1409–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, E. G.; Demir, N.; Sen, I. , The Relationship between Insulin Resistance and Liver Damage in non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Patients. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul 2020, 54, 411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Tanigaki, K.; Mineo, C.; Yuhanna, I. S.; Chambliss, K. L.; Quon, M. J.; Bonvini, E.; Shaul, P. W. , C-reactive protein inhibits insulin activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase via the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif of FcgammaRIIB and SHIP-1. Circ Res 2009, 104, 1275–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Qiu, S.; He, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, T.; Ding, N.; Li, F.; Zhao, A. Z.; Yang, G. , Genetic ablation of C-reactive protein gene confers resistance to obesity and insulin resistance in rats. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 1169–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowski, R.; Szczubiał, M.; Kostro, K.; Wawron, W.; Ceron, J. J.; Tvarijonaviciute, A. , Serum insulin-like growth factor-1 and C-reactive protein concentrations before and after ovariohysterectomy in bitches with pyometra. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Nilsson, E.; Lindholm, B.; Heimbürger, O.; Barany, P.; Stenvinkel, P.; Qureshi, A. R.; Chen, J. , Low-plasma insulin-like growth factor-1 associates with increased mortality in chronic kidney disease patients with reduced muscle strength. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2023, 33, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashi, Y.; Sukhanov, S.; Anwar, A.; Shai, S.-Y.; Delafontaine, P. , Aging, Atherosclerosis, and IGF-1. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2012, 67A, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashpole, N. M.; Sanders, J. E.; Hodges, E. L.; Yan, H.; Sonntag, W. E. , Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 and the aging brain. Exp Gerontol 2015, 68, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dichtel, L. E.; Corey, K. E.; Misdraji, J.; Bredella, M. A.; Schorr, M.; Osganian, S. A.; Young, B. J.; Sung, J. C.; Miller, K. K. , The Association Between IGF-1 Levels and the Histologic Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2017, 8, e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T. L.; Fourman, L. T.; Zheng, I.; McClure, C. M.; Feldpausch, M. N.; Torriani, M.; Corey, K. E.; Chung, R. T.; Lee, H.; Kleiner, D. E.; Hadigan, C. M.; Grinspoon, S. K. , Relationship of IGF-1 and IGF-Binding Proteins to Disease Severity and Glycemia in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2020, 106, e520–e533. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, B. D.; Goncalves, M. D.; Cantley, L. C. , Insulin–PI3K signalling: an evolutionarily insulated metabolic driver of cancer. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2020, 16, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-J.; Zhong, Y.; You, X.-Y.; Liu, W.-H.; Li, A.-Q.; Liu, S.-M. , Insulin-like growth factor 1 opposes the effects of C-reactive protein on endothelial cell activation. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2014, 385, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entezari, M.; Hashemi, D.; Taheriazam, A.; Zabolian, A.; Mohammadi, S.; Fakhri, F.; Hashemi, M.; Hushmandi, K.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Ertas, Y. N.; Mirzaei, S.; Samarghandian, S. , AMPK signaling in diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance and diabetic complications: A pre-clinical and clinical investigation. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 146, 112563. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.; Pan, J.; Qu, N.; Lei, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, J.; Han, D. , The AMPK pathway in fatty liver disease. Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, D.; Hellberg, K.; Chaix, A.; Wallace, M.; Herzig, S.; Badur, M. G.; Lin, T.; Shokhirev, M. N.; Pinto, A. F. M.; Ross, D. S.; Saghatelian, A.; Panda, S.; Dow, L. E.; Metallo, C. M.; Shaw, R. J. , Genetic Liver-Specific AMPK Activation Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity and NAFLD. Cell Reports 2019, 26, 192–208e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, L.; Guo, M.; He, J.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, J.; Ma, L. , Clinically relevant high levels of human C-reactive protein induces endothelial dysfunction and hypertension by inhibiting the AMPK-eNOS axis. Clinical Science 2020, 134, 1805–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. , AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) controls the aging process via an integrated signaling network. Ageing Research Reviews 2012, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D. M. , mTOR signaling at a glance. Journal of cell science 2009, 122, 3589–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Qiu, S.; Zhou, S.; Tan, Y.; Bai, Y.; Cao, H.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. , mTOR: A potential new target in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 9196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Weng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, K.; Fu, G.; Li, Y.; Bai, X.; Gao, Y. , mTOR direct crosstalk with STAT5 promotes de novo lipid synthesis and induces hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death & Disease 2019, 10, 619. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, S.; Zhan, Q.; Jiang, G.; Shan, Q.; Yin, L.; Wang, R.; Que, Q.; Wei, X.; Xu, S.; Yu, J. , E2F7 promotes mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 2022, 22, 2323–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.-K.; Huang, X.-R.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lyu, X.-F.; Liu, H.-F.; Lan, H. Y. , C-reactive protein promotes diabetic kidney disease in db/db mice via the CD32b-Smad3-mTOR signaling pathway. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 26740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwung, P.; Petersen, K. F.; Shulman, G. I.; Knowles, J. W. , Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Insulin Resistance, and Potential Genetic Implications: Potential Role of Alterations in Mitochondrial Function in the Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrinology 2020, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A. R.; Roden, M. , NAFLD and diabetes mellitus. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2017, 14, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, E. C.; Vousden, K. H. , The role of ROS in tumour development and progression. Nature Reviews Cancer 2022, 22, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanatos, R.; Sanz, A. , The role of mitochondrial ROS in the aging brain. FEBS letters 2018, 592, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Hu, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y. , The role of mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Molecular immunology 2018, 103, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, J.; Bogner, B.; Kiefer, J.; Braig, D.; Winninger, O.; Fricke, M.; Karasu, E.; Peter, K.; Huber-Lang, M.; Eisenhardt, S. U. , CRP Enhances the Innate Killing Mechanisms Phagocytosis and ROS Formation in a Conformation and Complement-Dependent Manner. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 721887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.-W.; Jung, I.-H.; Park, E.-Y.; Kim, K.-H.; Kim, K.; Yeom, J.; Jung, J.; Lee, S.-w. , Radiation-induced C-reactive protein triggers apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells through ROS interfering with the STAT3/Ref-1 complex. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2022, 26, 2104–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzanegi, P.; Dana, A.; Ebrahimpoor, Z.; Asadi, M.; Azarbayjani, M. A. , Mechanisms of beneficial effects of exercise training on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Roles of oxidative stress and inflammation. European journal of sport science 2019, 19, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I. C.; Liu, C.-S.; Cheng, W.-L.; Lin, T.-T.; Chen, H.-L.; Chen, P.-F.; Wu, R.-C.; Huang, C.-W.; Hsiung, C. A.; Hsu, C.-C. , Association of leukocyte mitochondrial DNA copy number with longitudinal C-reactive protein levels and survival in older adults: a cohort study. Immunity & Ageing 2022, 19, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Knez, J.; Marrachelli, V. G.; Cauwenberghs, N.; Winckelmans, E.; Zhang, Z.; Thijs, L.; Brguljan-Hitij, J.; Plusquin, M.; Delles, C.; Monleon, D. , Peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA content in relation to circulating metabolites and inflammatory markers: A population study. Plos one 2017, 12, e0181036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, B.; Xu, L.; Yu, S.; Fu, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, X.; Su, J. , ROS-Induced mtDNA Release: The Emerging Messenger for Communication between Neurons and Innate Immune Cells during Neurodegenerative Disorder Progression. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.-C. , NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2017, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilstra, J. S.; Clauson, C. L.; Niedernhofer, L. J.; Robbins, P. D. , NF-κB in Aging and Disease. Aging Dis 2011, 2, 449–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kunnumakkara, A.; Shabnam, B.; Girisa, S.; Harsha, C.; Banik, K.; Devi, T. B.; Choudhury, R.; Sahu, H.; Parama, D.; Sailo, B. L. , Inflammation, NF-κB, and chronic diseases: how are they linked? Critical Reviews™ in Immunology 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, K.; Cao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, C. , miR-125b promotes the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response in NAFLD via directly targeting TNFAIP3. Life Sciences 2021, 270, 119071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Badiwala, M. V.; Weisel, R. D.; Li, S.-H.; Wang, C.-H.; Fedak, P. W. M.; Li, R.-K.; Mickle, D. A. G. , C-reactive protein activates the nuclear factor-κB signal transduction pathway in saphenous vein endothelial cells: implications for atherosclerosis and restenosis. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2003, 126, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Bian, Z.-M.; Yu, W.-Z.; Yan, Z.; Chen, W.-C.; Li, X.-X. , Induction of interleukin-8 gene expression and protein secretion by C-reactive protein in ARPE-19 cells. Experimental Eye Research 2010, 91, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, C.; Gonzalez-Rodríguez, M.; Francisco, V.; Rajab, I. M.; Gómez, R.; Conde, J.; Lago, F.; Pino, J.; Mobasheri, A.; Gonzalez-Gay, M. A. , Monomeric C reactive protein (mCRP) regulates inflammatory responses in human and mouse chondrocytes. Laboratory Investigation 2021, 101, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, W. C.; Sherlock, L. G.; Grayck, M. R.; Zheng, L.; Lacayo, O. A.; Solar, M.; Orlicky, D. J.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Wright, C. J. , Innate Immune Zonation in the Liver: NF-κB (p50) Activation and C-Reactive Protein Expression in Response to Endotoxemia Are Zone Specific. The Journal of Immunology 2023, 210, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y. R.; Hunter, H.; de Gracia Hahn, D.; Duret, A.; Cheah, Q.; Dong, J.; Fairey, M.; Hjalmarsson, C.; Li, A.; Lim, H. K. , A systematic review of animal models of NAFLD finds high-fat, high-fructose diets most closely resemble human NAFLD. Hepatology 2021, 74, 1884–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, W.; Dillin, A. , Aging and survival: the genetics of life span extension by dietary restriction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 727–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. B.; Ramsey, J. J. , Honoring Clive McCay and 75 years of calorie restriction research. The Journal of nutrition 2010, 140, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.; Libina, N.; Kenyon, C. , Caenorhabditis elegans integrates food and reproductive signals in lifespan determination. Aging cell 2007, 6, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moatt, J. P.; Savola, E.; Regan, J. C.; Nussey, D. H.; Walling, C. A. , Lifespan extension via dietary restriction: time to reconsider the evolutionary mechanisms? BioEssays 2020, 42, 1900241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C. L.; Lamming, D. W.; Fontana, L. , Molecular mechanisms of dietary restriction promoting health and longevity. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2022, 23, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T. T.; McCullough, M. L.; Newby, P.; Manson, J. E.; Meigs, J. B.; Rifai, N.; Willett, W. C.; Hu, F. B. , Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction–. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2005, 82, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M. A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. , The Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular health: A critical review. Circulation research 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemalasari, I.; Fitri, N. A.; Sinto, R.; Tahapary, D. L.; Harbuwono, D. S. , Effect of calorie restriction diet on levels of C reactive protein (CRP) in obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2022, 16, 102388. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, T., Prevention of NAFLD/NASH by Astaxanthin and β-Cryptoxanthin. Carotenoids: Biosynthetic and Biofunctional Approaches 2021, 231-238.

- Xia, W.; Tang, N.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Low, T. Y.; Tan, S. C.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Y. , The effects of astaxanthin supplementation on obesity, blood pressure, CRP, glycemic biomarkers, and lipid profile: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacological Research 2020, 161, 105113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, C.; Galan, P.; Touvier, M.; Meunier, N.; Papet, I.; Sapin, V.; Cano, N.; Faure, P.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. , Antioxidant Status and the Risk of Elevated C-Reactive Protein 12 Years Later. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2014, 65, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, K. H. H.; Finck, B. N. , PPARs and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochimie 2017, 136, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, N.; Ogawa, Y.; Usui, T.; Tagami, T.; Kono, S.; Uesugi, H.; Sugiyama, H.; Sugawara, A.; Yamada, K.; Shimatsu, A. , Antiatherogenic effect of pioglitazone in type 2 diabetic patients irrespective of the responsiveness to its antidiabetic effect. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 2493–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Liu, J.-t.; Li, K.; Wang, S.-y.; Xu, S. , Genistein inhibits Ang II-induced CRP and MMP-9 generations via the ER-p38/ERK1/2-PPARγ-NF-κB signaling pathway in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Life sciences 2019, 216, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimbeni, F.; Pellegrini, E.; Lugari, S.; Mondelli, A.; Bursi, S.; Onfiani, G.; Carubbi, F.; Lonardo, A. , Statins and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the era of precision medicine: More friends than foes. Atherosclerosis 2019, 284, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandelouei, T.; Abbasifard, M.; Imani, D.; Aslani, S.; Razi, B.; Fasihi, M.; Shafiekhani, S.; Mohammadi, K.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Reiner, Ž. , Effect of statins on serum level of hs-CRP and CRP in patients with cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mediators of Inflammation 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboori, S.; Shab-Bidar, S.; Speakman, J. R.; Yousefi Rad, E.; Djafarian, K. , Effect of vitamin E supplementation on serum C-reactive protein level: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European journal of clinical nutrition 2015, 69, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashimada, M.; Ota, T. , Role of vitamin E in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. IUBMB life 2019, 71, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumpail, B. J.; Li, A. A.; John, N.; Sallam, S.; Shah, N. D.; Kwong, W.; Cholankeril, G.; Kim, D.; Ahmed, A. , The Role of Vitamin E in the Treatment of NAFLD. Diseases 2018, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano-Lopez, I.; Diaz-Morales, N.; Rovira-Llopis, S.; de Marañon, A. M.; Orden, S.; Alvarez, A.; Bañuls, C.; Rocha, M.; Murphy, M. P.; Hernandez-Mijares, A.; Victor, V. M. , The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ modulates oxidative stress, inflammation and leukocyte-endothelium interactions in leukocytes isolated from type 2 diabetic patients. Redox Biology 2016, 10, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torzewski, J.; Brunner, P.; Ries, W.; Garlichs, C. D.; Kayser, S.; Heigl, F.; Sheriff, A. , Targeting C-reactive protein by selective apheresis in humans: pros and cons. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattecka, S.; Brunner, P.; Hähnel, B.; Kunze, R.; Vogt, B.; Sheriff, A. , PentraSorb C-Reactive Protein: Characterization of the Selective C-Reactive Protein Adsorber Resin. Therapeutic Apheresis and Dialysis 2019, 23, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, W.; Torzewski, J.; Heigl, F.; Pfluecke, C.; Kelle, S.; Darius, H.; Ince, H.; Mitzner, S.; Nordbeck, P.; Butter, C. , C-reactive protein apheresis as anti-inflammatory therapy in acute myocardial infarction: results of the CAMI-1 study. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine 2021, 8, 591714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, F.; Matthes, H.; Schad, F. , Seven COVID-19 patients treated with C-reactive protein (CRP) apheresis. Journal of clinical medicine 2022, 11, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fendl, B.; Weiss, R.; Eichhorn, T.; Linsberger, I.; Afonyushkin, T.; Puhm, F.; Binder, C. J.; Fischer, M. B.; Weber, V. , Extracellular vesicles are associated with C-reactive protein in sepsis. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).