1. Introduction

In 1977, the Woesian revolution recognized archaea as a distinct domain of life (Balch et al. 1977). Since then, archaeal membranes have been studied comprehensively for their intriguing chemical composition, as well as for their contribution to robustness when thriving in extreme environments. A hallmark of archaeal phospholipids is the presence of ether bonds that connect the glycerol-1-phosphate (G1P) backbone to two isoprenoid chains (Jain, Caforio, and Driessen 2014). It differs from the phospholipids in bacterial membranes, which consist of a glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) backbone with ester bonded to two fatty acyl chains (Jain, Caforio, and Driessen 2014). This inherent difference in chemical composition of archaeal and bacterial membranes has been linked to their early evolution and is termed as the ‘lipid divide”, reflecting the split of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) into these two domains that occurred over 4.3 billion years ago. This ‘lipid divide’ is still evident in the organisms that live today, where the bulk phospholipid composition of most organisms adheres to the ‘lipid divide’ conundrum.

It has been proposed that mixed heterochiral membranes are intrinsically unstable, and this would have been the driving force of the ‘lipid divide’ where life originated from the last universal common ancestor, LUCA (Koga, Kyuragi, Nishihara, & Sone, 1998)(Wächtershäuser 2003). This hypothesis has been challenged by in vitro studies showing that liposomes composed of mixed heterochiral membranes are stable (Shimada and Yamagishi 2011). Furthermore, reconstruction of the archaeal phospholipid biosynthetic pathway in E. coli resulted in mixed heterochiral membranes that supported the growth of this engineered strain (Caforio et al. 2018). Additionally, the reconstruction of lipid biosynthetic pathways from uncultured Lokiarchaeota_BC1 and Thorarchaeota AB led to the production of a heterochiral mixed membrane in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, wherein the G3P-based enantiomer constituted a minor fraction (0.51-0.69%) of the total unsaturated archaeol pool (Zhang et al., 2023). Hence, membrane instability is unlikely the main reason for the ‘lipid divide’ and rather, it is believed that LUCA was not a single life form, but a heterogeneous mixture of organisms which eventually led to the successful emergence of two lineages – Archaea and Bacteria. Hence, the question about the driving force behind the ‘lipid divide’ remains unanswered for now. Recently, it was hypothesized that archaeal and bacterial membranes are differently optimized for efficient energy transduction, where in archaeal membranes would be optimized for limited H+ leaks under a wide range of environmental conditions whereas bacterial membranes would be optimized for efficient lateral H+ transport along the carbonyl oxygen of the ester bond supporting localized chemioosmosis (Mencía 2020).

Likely due to horizontal or convergent evolution, exceptions to this divide also seem to exist. For instance, members of Ca.Cloacimonetes from the bacterial Fibrobacteres–Chlorobi–Bacteroidetes (FCB) superphylum have the potential to synthesize archaeal ether-linked phospholipids with a presumed G1P stereochemistry (Villanueva et al. 2021). Additionally, bacteria from Rubrobacteracles contain ~46% ether-linked phospholipids of their core lipids (Sinninghe Damsté et al. 2023). A similar phenomenon is observed in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima wherein mixed membrane-spanning tetraethers/tetraesters are found (Sahonero-Canavesi et al. 2022). However, in both these studies, the stereochemistry of the phospholipids was not determined.

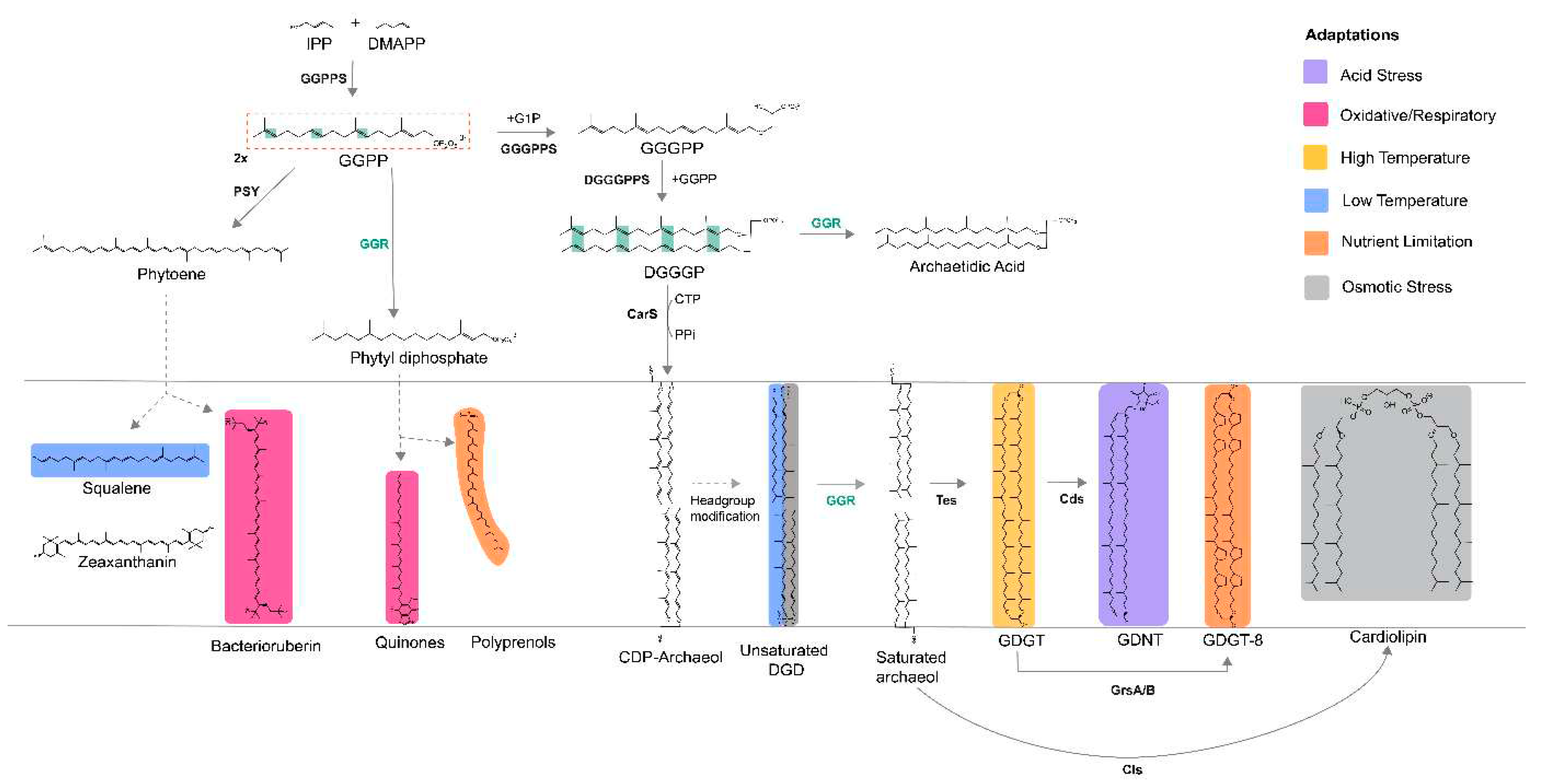

In recent years, the biosynthetic pathway of archaeal membrane phospholipids has been elucidated near to completion (Jain, Caforio, and Driessen 2014)(Lloyd et al. 2022). This pathway is initiated with two isoprenoid building blocks, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), via the alternate or classical mevalonate pathway (

Figure 1) (Rastädter et al. 2020). Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) synthase catalyzes the condensation of IPP and DMAPP to form geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) (

Figure 1) (Jain, Caforio, and Driessen 2014). GGPP is condensed with the G1P backbone by geranylgeranyl glycerol phosphate synthase (GGGPS) to form GGGP (

Figure 1) (Jain, Caforio, and Driessen 2014). GGGP is processed by digeranylgeranyl glyceryl phosphate synthase (DGGGPS) to form DGGGP (Ren et al. 2020). Next, DGGGP is activated by CarS with CTP for polar headgroup attachment, yielding CMP-DGGGP or CDP archaeols (Jain, Caforio, Fodran, et al. 2014). CDP-archaeol is a key intermediate in this pathway and a precursor for polar headgroup diversification (Jain, Caforio, Fodran, et al. 2014). There is uncertainty at what stage the isoprenoid chains are saturated by geranylgeranyl reductase (GGR) as saturated archaetidic acid is a poor substrate for CarS (Jain, Caforio, Fodran, et al. 2014). However, GGR can reduce DGGGP to archaetidic acid

in-vitro (Sato et al. 2008). Next, polar head group differentiation occurs that involves members of the universal family of transferases (Jain, Caforio, Fodran, et al. 2014).

Membrane-spanning glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetrathers (GDGTs) are formed through tail-to-tail condensation of saturated archaeols or dialkyl glycerol diethers (DGDs) via tetraether synthase (Tes, radical SAM enzyme) (Lloyd et al. 2022)(Zeng et al. 2022). GDGTs can be linked by calditol or nonnitol headgroups to form glycerol dialkyl nonnitol tetraether (GDNTs) through another rSAM enzyme, calditol synthase (Cds) (Zeng et al. 2018). GDGTs can be found in nature with cyclopentane rings ranging from 0 to 8 (Sinninghe Damsté et al. 2002). Cyclized GDGTs increase the membrane packing and stability (Zhou et al. 2019). The GDGT ring synthases – GrsA and GrsB introduce rings at the C-7 and C-3 positions, respectively, in the GDGT core lipid (Zeng et al. 2019), whereas the enzyme that introduces a hexyl ring in the tetraether lipids of Thaumarcheota has not been identified yet. The incorporation of these rings in archaeal GDGTs is regulated by pH, temperature, energy availability, and electron donor flux (Zhou et al. 2019)(Yang et al. 2022). It is also a diagnostic tool to identify different clades of archaea.

Apart from membrane lipids, isoprene or terpene units can undergo chain elongation and modifications (like cyclization) to form respiratory quinones or carotenoids or polyprenols in archaea. As a deviation of the aforementioned phospholipid biosynthetic pathway, GGPP can also undergo partial reduction by GGR to form diphytyl diphosphate, which for instance in

Sulfolobus acidocaldarius is a precursor for caldariellaquinones (CQ) (Sasaki et al. 2011). Additionally, two molecules of GGPP can condense to form phytoene via phytoene synthase (PSY) (

Figure 1) (Giani et al. 2020)(De Castro et al. 2022). The biosynthesis of phytoene is a crucial regulatory step in carotenogenesis, which subsequently leads to the formation of lycopene, squalene, or zeaxanthanin (De Castro et al. 2022). The enzymes responsible for chain elongation and modification of membrane-associated terpenoids in archaea remain unknown. Based on the canonical pathways in bacteria, this likely occurs through

cis-isoprenyl diphosphate synthase (IPPS) or

trans-IPPS enzymes which catalyze the head-to-tail condensation of isoprene units (Hoshino and Villanueva 2023). Specifically, the synthesis of squalene and carotenoids in archaea could be catalyzed by homologs of enzymes such as phytoene synthase (CrtB) or hydroxysqualene dehydroxylase (HpnE) (Hoshino and Villanueva 2023).

2. Saturation in Archaeal Membranes

Some Archaea thrive in extreme and unstable environments of low or high temperatures (as low as 0°C, or up to 121°C), acidic or alkaline pH (as low as pH 0.8, or up to pH 11), salinity (saturated salt lakes with aw as low as 0.6), and pressure (up to 1100 bar) (Baker et al. 2020). Some are even polyextremophiles which inhabit environments with multiple extremes. Further, not all archaea are extremophilic and this domain also contains mesophiles that thrive in more moderate environments. The physicochemical properties of archaeal membranes are distinctive and modulated through unique mechanisms (Koga 2012). However, different environments require distinct adaptations to the membranes; hence, various mechanisms of membrane adaptation can be found. Studies on the ion and proton permeability of diether-based archaeal liposomes revealed the presence of methyl groups on the phospholipid tails, and the ether bond present between the glycerol backbone and hydrophobic tail aids in the low permeability of membranes formed from diether phospholipids (Łapińska et al. 2023). However, liposomes consisting of only diether G1P based archaeal lipids show a higher proton permeability compared to liposomes composed mostly of tetraether lipids from S. acidocaldarius (Łapińska et al. 2023)(Komatsu and Chong 1998)(Gmajner et al. 2011)(Chong, Bonanno, and Ayesa 2017). Furthermore, the membranes of archaea may harbor various proportions of DGDs and GDGTs, which helps in regulating the permeability characteristics depending on the environmental conditions. For example, hyperthermophilic methanogens increase the membrane-spanning GDGTs content at higher temperatures at the expense of DGDs (Koga 2012). Membranes of archaea typically show a low phase transition temperature and a broad melting behavior (Siliakus, van der Oost, and Kengen 2017), which is attributed to the presence of the isoprenoid chains, their length, degree of saturation and the positioning of methyl groups (Driessen and Albers 2007) (Dannenmuller et al. 2000). In psychrophilic archaea, an increase in unsaturation of the isoprenoid chains has been observed as an adaptation to cold temperatures or increasing salinity (Dawson, Freeman, and Macalady 2012)(Dong and Chen 2012). Saturated membranes provide resistance against hydrolysis and oxidation, aiding the survival of archaea in extreme environments (Sasaki et al. 2011). In bacterial membranes, the degree of saturation and variations in the length of fatty acid chains are adaptations that maintain the viscosity of membranes in response to varying temperatures, also termed homovisceous adaptation. Similar suggestions have been made for archaeal membranes (Siliakus et al. 2017), which was confirmed experimentally for one archaeal psychrophile and three halophiles. Methanococcoides burtonii is a psychrophilic archaeon which produces unsaturated species of archaetidylglycerol (AG), archaetidylinositol (AI) and hydroxyarchaeol (ArOH) only when grow at 4°C, but not when grown at its optimum temperature of 23°C (Nichols et al. 2004). The genome of this psychrophile contains a single copy of the GGR and four paralogs (Allen et al. 2009); however, it lacks homologs of desaturases from bacteria and eukaryotes, which can catalyze the addition of hydrogen bonds (Saunders et al. 2003)(Goodchild et al. 2004). Later, a putative phytoene desaturase from Methanosarcina acetivorans was investigated; however, this enzyme was found to be responsible for the biosynthesis of hydroxyarchaeols (Mori et al. 2015).

Halophiles such as Natronomonas pharaonis, Haloferax sulfurifontis, and Halobaculum gomorrense demonstrate a strong correlation between optimal growth salinity and the fraction of unsaturated DGDs in their membranes, except for Halohabdus utahensis (Dawson et al. 2012). Polyextremophiles (psychrophiles and halophiles) such as Halohasta litchfieldiae and Halorubrum lacusprofundi synthesize lower levels of GGR in response to growth at 4 and 10°C (Williams et al. 2017). Additionally, the levels of hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) synthase from the mevalonate pathway were elevated in the proteomes of these organisms at cold temperatures (Williams et al. 2017). Notably, unsaturated DGDs are not exclusive to psychrophiles or halophiles and can also be found in hyperthermophilic methanogens, such as Methanopyrus kandleri and Thermococcus sp. (Sprott, Agnew, and Patel 1997)(Hafenbradl et al. 1993)(Gonthier et al. 2001).

GGRs are flavoenzymes found in archaea, plants and photosynthetic bacteria (Wang et al. 2014)(Tsukatani et al. 2022)(Nishimura and Eguchi 2006b). They are promiscuous and can catalyze the partial or complete saturation of a variety of substrates including DGGGP, GGPP, farnesyl pyrophosphate (FP), farnesol (FOH), and geranylgeraniol (GOH) (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Meadows et al. 2018). Because of their promiscuity, they have been of interest as biocatalysts to reduce polyterpenes of various chain lengths (Kung et al. 2014)(Cervinka et al. 2021a). Archaeal GGRs reduce only three distal C

= C bonds of their natural substrate GGPP, whereas GGGP derivatives can be fully saturated (Sasaki et al. 2011) (

Figure 1). Remarkably, they were able to reduce all double bonds when the substrate was elongated with a succinate spacer region (Cervinka et al. 2021b). The introduction of a spacer region allows for binding to the anion binding site of the enzyme while presenting proximal double bonds to the active site, leading to the full reduction of the substrate (Cervinka et al. 2021b). Thus, the chain length of the substrate appears to be a regulatory factor in the extent of saturation.

GGRs from

Archaeoglobus fulgidus, Thermoplasma acidophilum, and

Methanosarcina acetivorans have been successfully expressed, purified and characterized in

Escherichia coli (Murakami et al., 2007)(Ogawa et al. 2014).

M. acetivorans GGR requires a specific

in vivo reducer to catalyze the reduction of DGGGP, which is the native ferredoxin-encoding gene that is localized in the same genomic locus and displays regiospecificity for the ω-terminal double bond (Isobe et al. 2014). The

in vivo reducers of

A. fulgidus and

S. acidocaldarius remain unknown; thus, sodium dithionite was used in

in-vitro reactions(Murakami et al., 2007) (Sasaki et al. 2011).

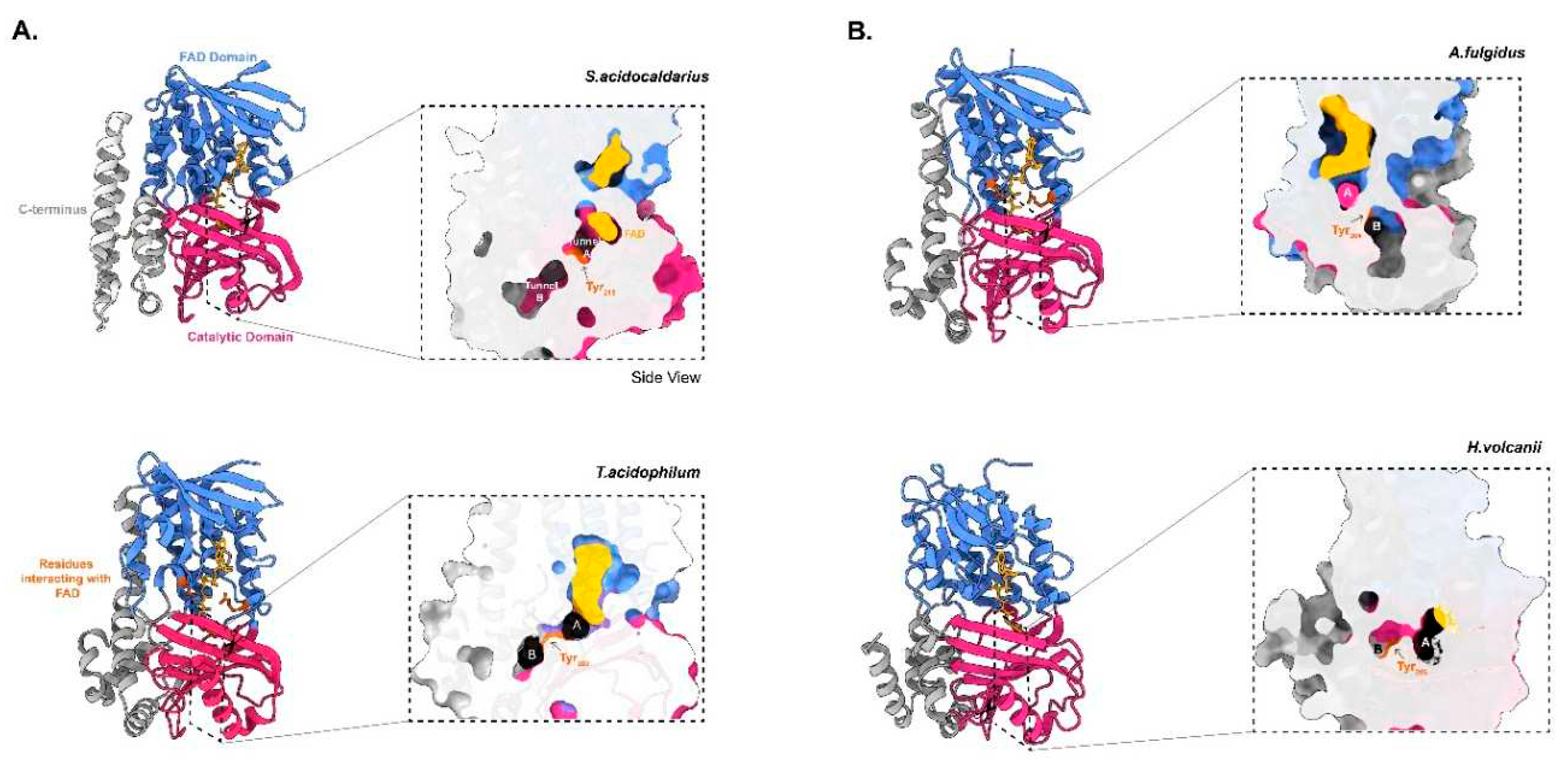

Thermoplasma acidophilum GGR requires NADP as a reducer (Nishimura & Eguchi, 2006). So far, the crystal structures of only two archaeal GGRs are available:

Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and

T. acidophilum (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Nishimura & Eguchi, 2006) (

Figure 2). Both the crystal structures were obtained in complex with FAD (Sasaki et al. 2011) (Nishimura & Eguchi, 2006) (

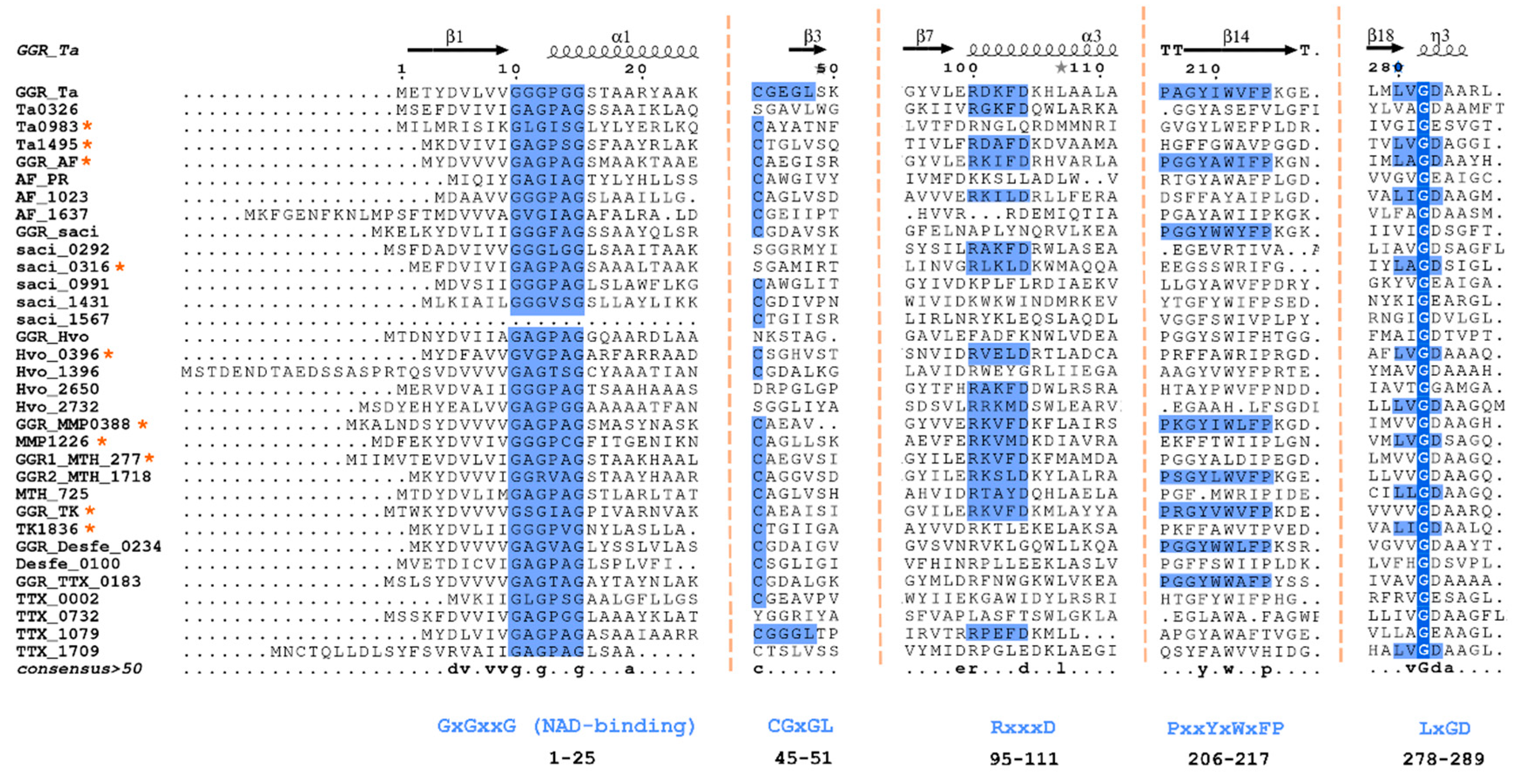

Figure 2).Some sequence motifs are conserved throughout all archaeal GGRs. Examples include GxGxxG (NAD-binding domain) and PxxxWxFP (catalytic domain) (

Figure 2)(Murakami et al. 2007). Motifs associated with FAD interaction, such as LxGD and RxxxD, are conserved in

A. fulgidus,

T. acidophilum, and

M. acetivorans (Murakami et al. 2007). Additionally, the CGGG motif which interacts with the isoalloxazine ring of the FAD has been reported only in

T. acidophilum (

Figure 2) (Murakami et al., 2007). However, the Cys47 residue itself is conserved throughout all archaeal GGRs and is essential for catalysis in

the S. acidocaldarius enzyme (

Figure 2) (Sasaki et al. 2011). This cysteine is speculated to be involved in electron transfer or modulation of the reactivity of flavin (Xu et al. 2010). The ligand binding domain of archaeal GGRs consists of two tunnels: A and B (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Xu et al. 2010). Tunnel A is narrow and restrictive, whereas tunnel B is more permissive in its size (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Xu et al. 2010) (

Figure 2). Tunnel B harbors hydrophobic amino acid residues and tunnel A is close to the isoallozaxine ring of FAD (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Xu et al. 2010) (

Figure 2). Both tunnels are separated by a tyrosine residue (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Xu et al. 2010) (

Figure 2). The catalytic motif PxxxWxFP is close to the FAD ring and forms a β-strand with hydrophobic residues such as tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Xu et al. 2010). The positioning of these residues form a cavity that can accommodate the geranyl group and ensures the optimal positioning of the unsaturated substrate towards FAD for reduction (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Xu et al. 2010). The FAD ring undergoes conformational changes depending on its reduction state (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Xu et al. 2010).The arginine residue from RxxFD motif interacts with the O4′ (3.0 Å) and O2′ (3.1 Å) of the FAD; this motif is placed opposite to the LxGD in the

T. acidophilum structure (Xu et al. 2010) (

Figure 2). Therefore, it is proposed that these residues likely play a role in the conformational switch of FAD (Xu et al. 2010). Interestingly, the

S. acidocaldarius GGR lacks these motifs (Sasaki et al. 2011).

Although GGRs act on lipophilic substrates, they do not contain transmembrane domains. Nevertheless, the

T.

acidophilum GGR was expressed and purified from the membrane fraction of

E.coli (Nishimura & Eguchi, 2006). Remarkably, only the

S. acidocaldarius GGR contains amphipathic α-helices at its C-terminus, which are thought to mediate membrane association (

Figure 2) (Sasaki et al. 2011)(Kung et al. 2014). Interestingly, this structural motif is shared by a set of lipid-synthesizing enzymes including the Tes and the cyclopropane fatty acid synthase from

E.coli (Lloyd et al. 2022). This structure seems to act as lipid pocket that is lined solely by hydrophobic residues (Lloyd et al. 2022). The

S.acidocaldarius structure also contains a disulfide bridge formed by Cys310 and Cys335, which is unique to GGR (Sasaki et al. 2011).

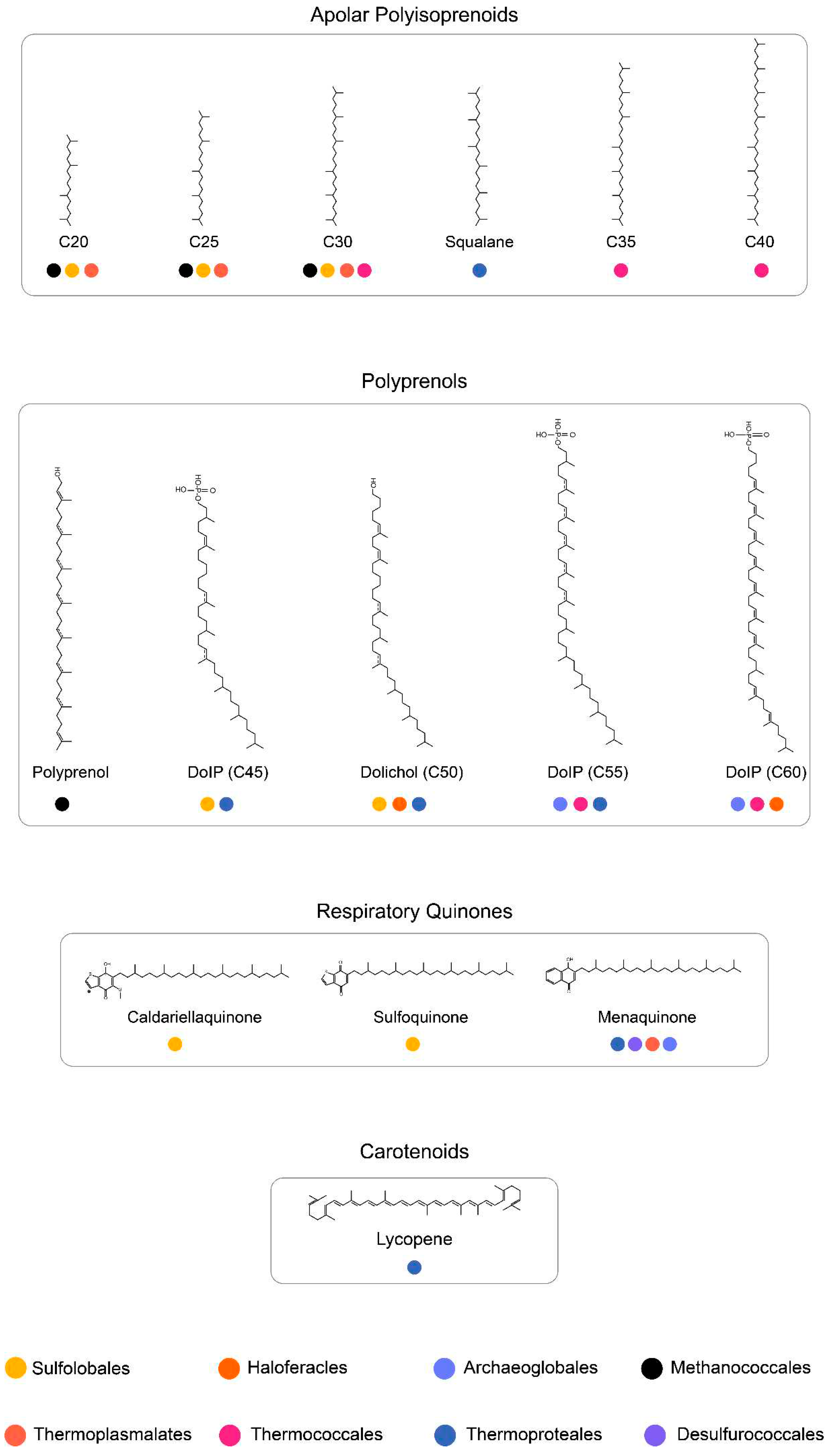

3. Multiplicity of GGRs in Archaeal Genomes

Apart from membrane phospholipids, archaea also harbor isoprenoid-based polyterpenes, such as carotenoids, apolar polysioprenoids, polyprenyl phosphates, and quinones, whose complete biosynthetic pathways are not yet known (Salvador-Castell et al. 2019). These polyterpenes are found in various saturation states in archaeal membranes, and some have been proposed to modulate membrane properties (Salvador-Castell et al. 2019). Most archaea have a multiplicity of GGRs in their genomes, which are clustered in the archaeal orthologous cluster of genes arCOG00570 (Hernández-Plaza et al. 2022)(Makarova, Wolf, and Koonin 2015). Currently, this cluster consists of 2024 genes from 452 archaeal species (Makarova et al. 2015). Investigation of some of these proteins from

A. fulgidus led to the discovery of menaquinone (MK)-specific prenyl reductase (AF_PR) (Hemmi et al. 2005). This enzyme was found to be responsible for producing partially saturated side chains of octaprenyl MK in

E. coli (Hemmi et al. 2005). Interestingly, this enzyme does not have any predicted transmembrane domains nor does it contain the catalytic and FAD-associated GGR motifs (

Figure 3) (Hemmi et al. 2005). Other paralogs from

A. fulgidus were also investigated in this study; however, their expression did not lead to any alteration in the quinone profile of

E. coli (Hemmi et al. 2005). Such GGR paralogs have also been found in mycobacteria, one of which was recently identified as heptaprenyl reductase (HepR)(Abe et al. 2022). HepR was able to reduce ω- and

E- prenyl units in Z,E-mixed heptaprenyl diphosphates from

Mycolicibacterium vanbaalenii (Abe et al. 2022). The majority of GGR paralogs from archaea remain uncharacterized, and their presence has been correlated with the saturation states of polyterpenes in archaeal membranes (Guan et al. 2011).

The focus of this review is on the uncharacterized GGR paralogs present in the genomes of extremophilic archaea. These will be discussed through structural information obtained through AlphaFold2 modeling, analyses of the genomic loci, conserved domains, extant protein or transcript expression datasets from these organisms, and where possible correlated to specific terpenoids or isoprenoids.

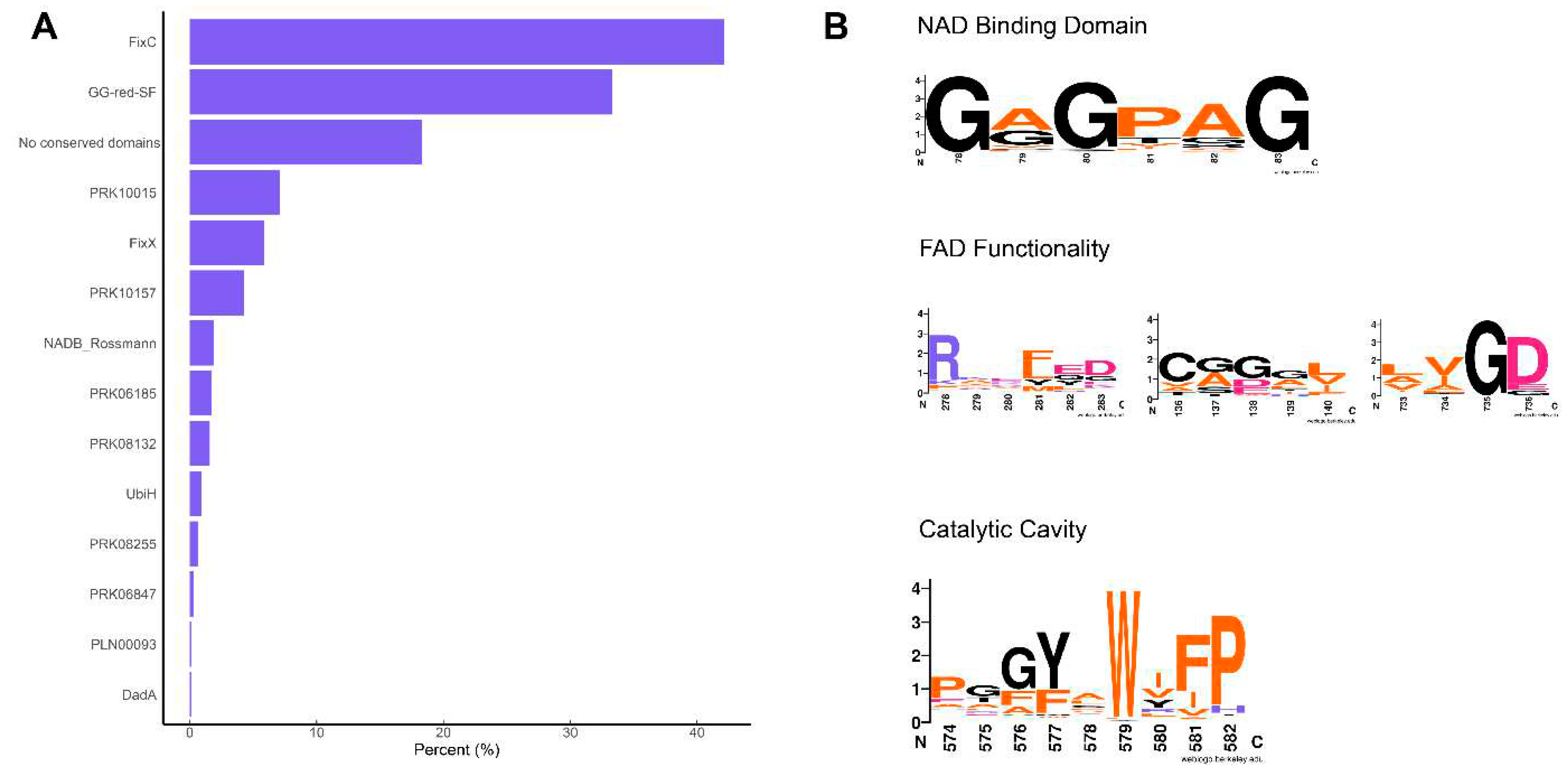

4. Conserved Sequence and Structural Motifs in Archaeal GGR Paralogs

A batch conserved domain analysis indicated that 40% of these proteins had a FixC domain (flavoproteins, such as dehydrogenase), 33% had a GG-red-SF domain (containing the GGR family), 18.3% did not contain any conserved domains, and only 5% had the NADB_Rossman domain (

Figure 3A). The latter is found in the FAD domain of all identified archaeal GGRs (Xu et al. 2010). The GxGxxG motif that is associated with NAD binding showed high sequence conservation in this arCOG (

Figure 3B)(Lesk 1995). The entire PxxYxWxFP motif associated with the catalytic cavity of GGRs is not highly conserved in this arCOG (

Figure 3B). However, the hydrophobic residues tyrosine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine were quite well conserved (

Figure 3B). As previously described, these residues play a critical role in determining the shape of the catalytic cavity in archaeal GGRs. Low sequence conservation was observed for the LxGD and RxxFD motifs, which are involved in FAD interaction (

Figure 3B). The arginine from the RxxFD motif is highly conserved in this cluster and is likely associated with the interaction and conformational switch of FAD (

Figure 3b).

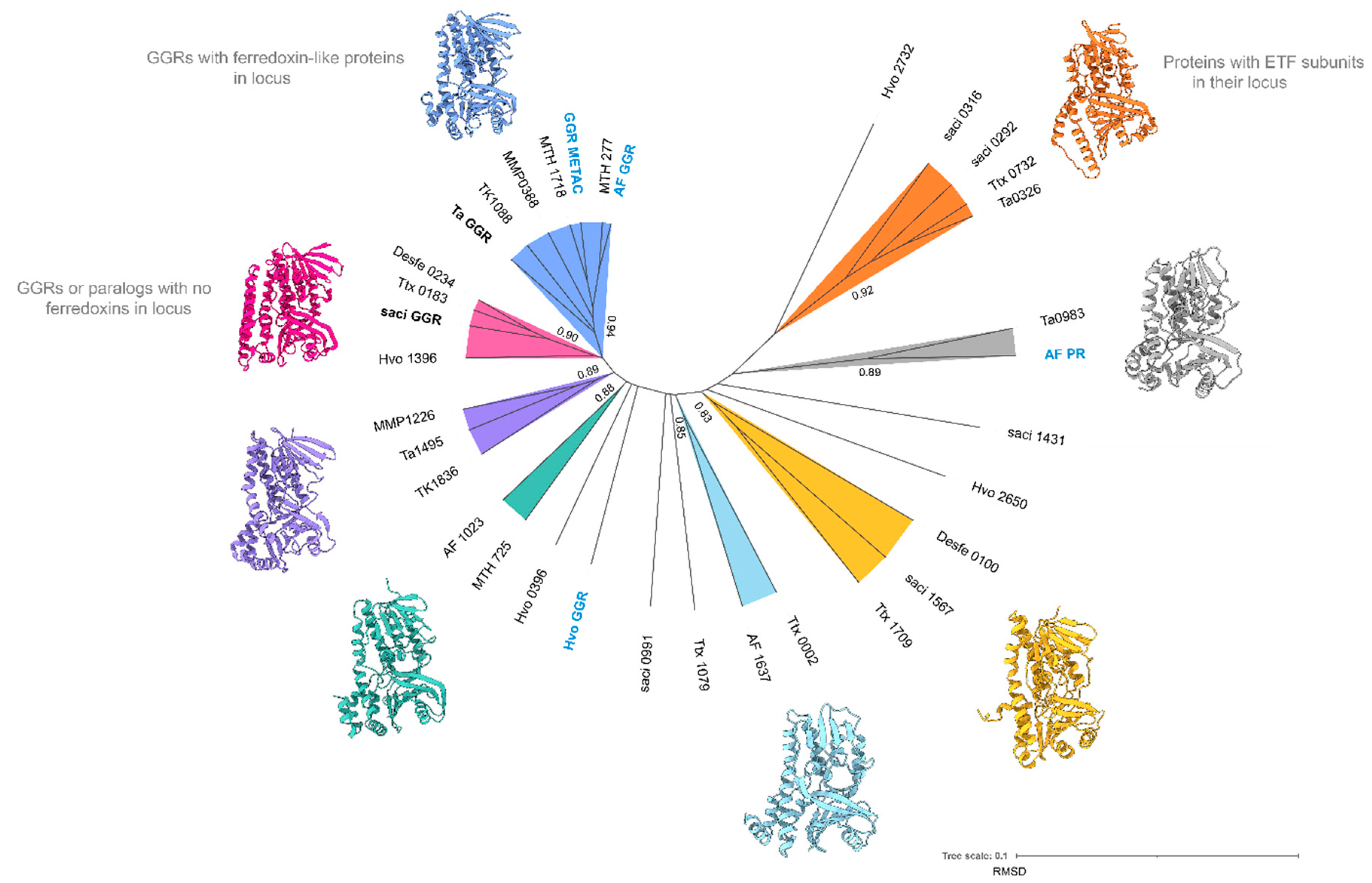

To understand the structural conservation among these paralogs, a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) tree was constructed from extremophilic archaeal model organisms using mTM-align (

Figure 4) (Dong et al. 2018). For this RMSD tree, the available crystal structures of archaeal GGRs and structure models from AlphaFold were used as the input (Jumper et al. 2021). Structural alignment shows diversity among these paralogs. Notably, GGR or paralogs with ferredoxin-like proteins in their genomic loci tend to cluster together (

Figure 4, orange and blue). Similarly, GGRs or paralogs with no such proteins in their loci clustered amongst themselves (

Figure 4, pink). In the following sections, these paralogs are discussed in more depth based on their structural models, conservation of motifs, and genomic loci from extremophilic archaeal species. The predicted structures of the representative proteins from the various colored nodes (

Figure 4) were supplemented with co-factors and/or ligands with AlphaFill (Figures 5B, 7B, 8B, 9B, 10B, 11B, AND 14B) (Hekkelman et al. 2023).

Figure 4.

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) tree of archaeal GGRs and their paralogs. Proteins with available crystal structures are indicated in bold. Functionally characterized proteins (through heterologous expression or gene deletion) are denoted in blue and bold, respectively. The remaining structures were generated using AlphaFold2 (Jumper et al. 2021). mTM-Align was used as an algorithm for structural imposition and the tree was constructed using the neighbor joining method in PHYLIP (Dong et al. 2018)(Eguchi 2011). TM scores for structural impositions are indicated at the nodes. Tree was visualized, annotated through iTOL and UCSF Chimera (Letunic and Bork 2021)(Pettersen et al. 2004).

Figure 4.

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) tree of archaeal GGRs and their paralogs. Proteins with available crystal structures are indicated in bold. Functionally characterized proteins (through heterologous expression or gene deletion) are denoted in blue and bold, respectively. The remaining structures were generated using AlphaFold2 (Jumper et al. 2021). mTM-Align was used as an algorithm for structural imposition and the tree was constructed using the neighbor joining method in PHYLIP (Dong et al. 2018)(Eguchi 2011). TM scores for structural impositions are indicated at the nodes. Tree was visualized, annotated through iTOL and UCSF Chimera (Letunic and Bork 2021)(Pettersen et al. 2004).

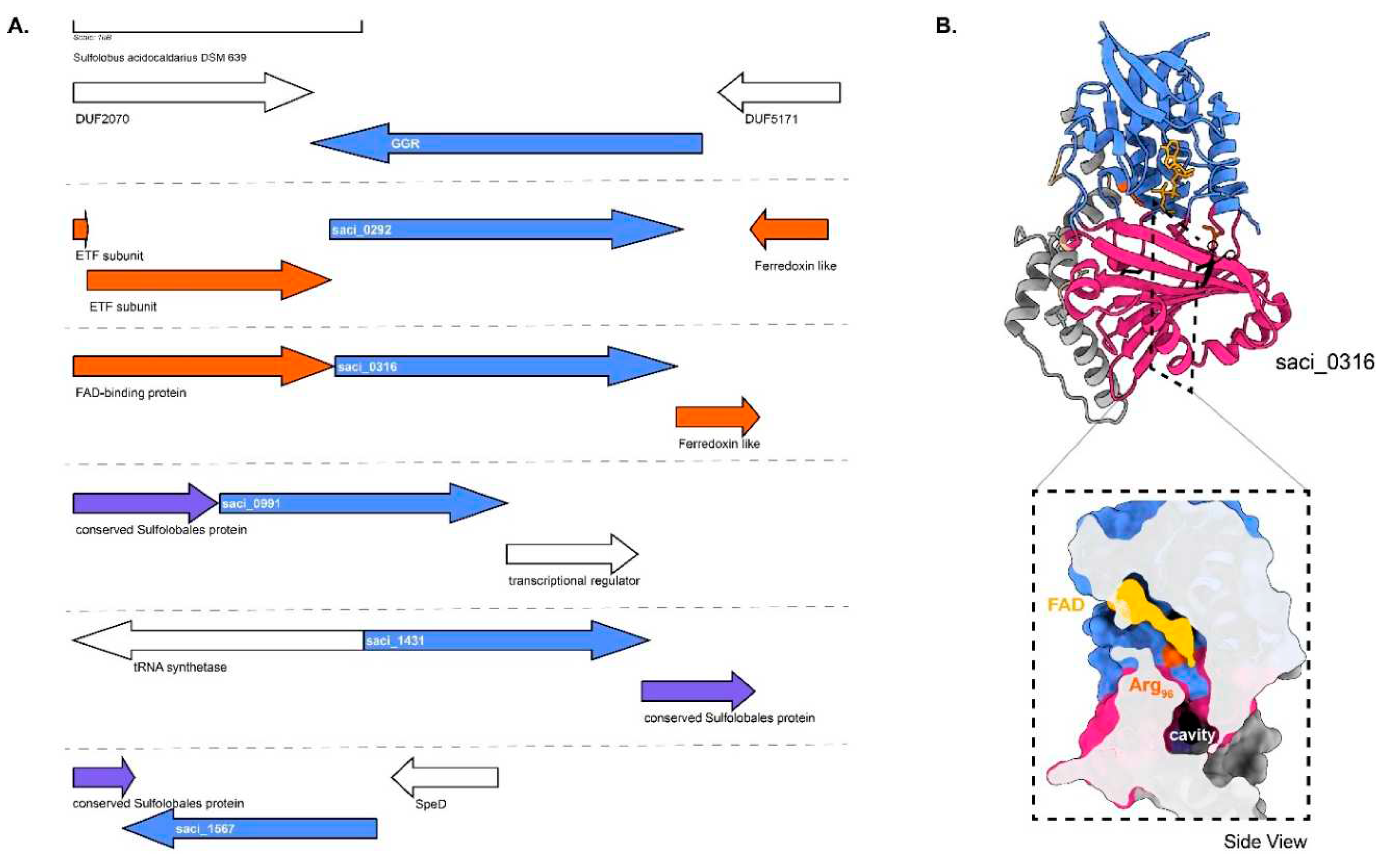

Figure 5.

Genomic locus of

S. acidocaldarius GGR and its paralogs, modeled structure of saci_0316 with a cross-section across its surface: A. Figure was generated using GeneGraphics(Harrison, Crécy-Lagard, and Zallot 2018). ETF, electron transfer flavoprotein; SpeD, S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. FAD binding/ETF/ferredoxin-like proteins are colored orange. Conserved proteins in the same order are colored purple. Annotations have been added based on conservation information from the arCOGs or Uniprot. B. Colors in the Alphafold2 model structure indicate domains, and the color scheme is the same as that in

Figure 2.

Figure 5.

Genomic locus of

S. acidocaldarius GGR and its paralogs, modeled structure of saci_0316 with a cross-section across its surface: A. Figure was generated using GeneGraphics(Harrison, Crécy-Lagard, and Zallot 2018). ETF, electron transfer flavoprotein; SpeD, S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. FAD binding/ETF/ferredoxin-like proteins are colored orange. Conserved proteins in the same order are colored purple. Annotations have been added based on conservation information from the arCOGs or Uniprot. B. Colors in the Alphafold2 model structure indicate domains, and the color scheme is the same as that in

Figure 2.

5. GGR Paralogs from Sulfolobales

The order Sulfolobales consists of sulfur-metabolizing, strictly aerobic thermoacidophiles in crenarchaeota (Liu et al. 2021). The membrane of Sulfolobales is composed of ~99% monolayer forming GDGTs and GDNTs (Jensen et al. 2015). GDGTs are the dominant species in the membrane, whereas GDNTs are less abundant (Jensen et al. 2015). Deletion of the calditol synthase (Cds) in S. acidocaldarius, and hence the loss of GDNTs in the membrane, rendered cells lethal to a low pH (1.0) environment; thus, GDNTs have been proposed to aid in acidic stress (Zeng et al. 2018). Bilayer-forming DGDs constitute a minor fraction of the membrane (Jensen et al. 2015). The common polar headgroups found in membrane phospholipids include: monohexose, di-hexose, penta-hexose and sulfoquinovose (Jensen et al. 2015)(de Kok et al. 2021). Interestingly, the presence of carotenoids has only been reported in a natural mutant of Sulfolobus shibatae (Kull and Pfander 1997). The carotenoid species were identified as C50 (Z)- isomers of zeaxanthin and were proposed as membrane reinforcers (Kull and Pfander 1997).

S. acidocaldarius (optimum: 75°C, pH 3.0) is a model organism from the order of Sulfolobales and its membrane has been studied extensively. The most common adaptations of the membrane include the incorporation of cyclopentane rings (0–8) and altering the ratio of GDGTS to DGDs (Rastädter et al. 2020b)(Quehenberger et al. 2020). The latter is dependent on the growth phase and rate (Quehenberger et al. 2020). Specifically, an increase in the growth rate is correlated with an increased ratio (from 1:3 to 1:5) of GDGTs to DGDs and a decrease in the average number of cyclopentane rings (from 5.1 to 4.6) (Quehenberger et al. 2020). The incorporation of pentacyclic rings is also affected by the availability of nutrients and growth phase (Quehenberger et al. 2020)(Bischof et al. 2019). Under nutrient-rich conditions, the overall number of cyclopentane rings decreases, leading to increased permeability, whereas under conditions of nutrient depletion, the overall number of rings remains unchanged (Bischof et al. 2019). The organism also produces species of respiratory quinones, such as caldariellaquinone (CQ) and sulfoquinone (SQ), membrane anchors, such as dolichol phosphate (DoIP), and C20-C35 apolar polyisoprenoids (Salvador-Castell et al. 2019)(Holzer, Oró, and Tornabene 1979)(Elling et al. 2016). Typically, CQ and SQs are found in their fully saturated forms, and their production is dependent on the amount of oxygen (Elling et al. 2016)(Trincone et al. 1989). Fully saturated species of α- and ω-of C40,C45, and C50 DoIP species have been found in Sulfolobus (Guan et al. 2011). Partially saturated species of C45 DoIP with three to eight double bonds have also been reported (Guan et al. 2016). However, the saturation profiles of C20-C35 polyisoprenoids remain elusive (Holzer et al. 1979).

The crystal structure of GGR from

S. acidocaldarius consists of three distinct domains: FAD binding, catalytic, and a C-terminal domain (Sasaki et al. 2011) (

Figure 2). This GGR does not have a ferredoxin-encoding gene near its genomic locus (

Figure 5A). There are five uncharacterized paralogs of GGRs in this species, saci_0292 (PRK10015 superfamily, provisional oxidoreductases), saci_0316 (FixC superfamily), saci_0991, saci_1431, and saci_1567. All these paralogs are well expressed in the stationary growth phase of

S. acidocaldarius (Cohen et al. 2016). Notably, none of these paralogs clustered with

the S. acidocaldarius GGR in the RMSD tree (

Figure 4).

Saci_0316 is in the vicinity of genes encoding a FAD-binding protein and a ferredoxin family protein (

Figure 6). Saci_0292 has two predicted electron transport flavoprotein (ETF) subunits in its cluster: saci_0290 (arCOG00446) and saci_0291 (arCOG00447) (

Figure 6). Meanwhile, saci_0293 is a predicted ferredoxin-like protein conserved only in crenarchaeota (arCOG01985) (

Figure 6). Saci_0292 and saci_0316 share the node with other paralogs in the RMSD tree, which also harbors ferredoxins or

other subunits in their genomic locus (

Figure 4). These proteins contain the RxxxD motif, whereas saci_0316 contains the LxGD motif (

Figure 6). A cross-section across the surface of the model structure of saci_0316 shows the presence of a cavity (

Figure 5B). Interestingly, the Cys47 residue (essential for catalysis in

S. acidocaldarius GGR) was conserved only in saci_0991, saci_1431, and saci_1567 (

Figure 6). Meanwhile, Saci_0991 and Saci _1567 have conserved Sulfolobales proteins in their genomic loci (

Figure 6). Saci_0316, saci_1431 and saci_1567 are suggested to encode for essential proteins based on a genome wide transposon mutagenesis study in

S. islandicus (Zhang et al. 2018).

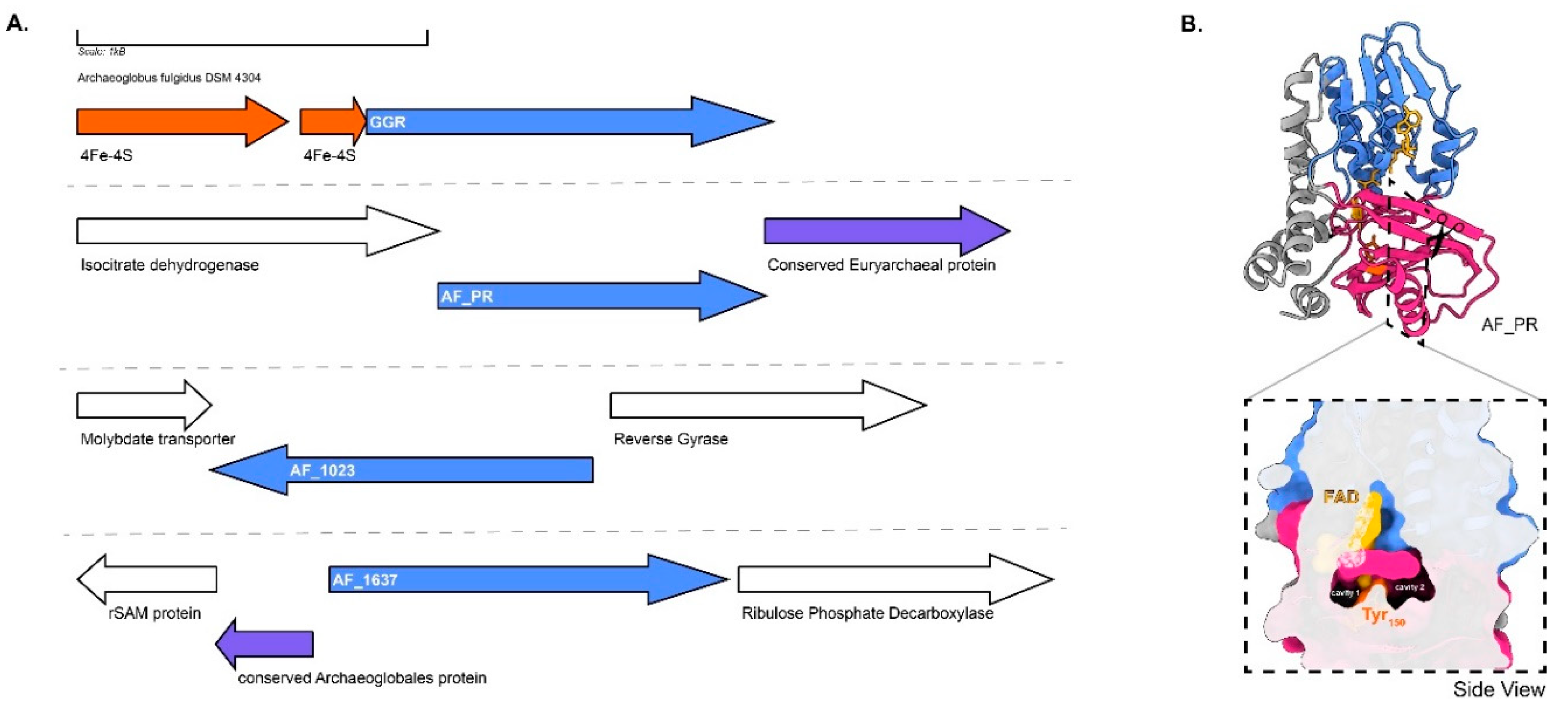

6. Archaeoglobales

Archaeoglobales are sulfur-metabolizing hyperthermophiles that are strict anaerobes (Beeder et al. 1994). Organisms belonging to this order can be found in hydrothermal environments such as vents, oil wells, and springs (Beeder et al. 1994). Archaeoglobus fulgidus is a model organism of this order and is slightly halophilic (1.9% NaCl, wt/vol) (Borges et al. 2006). The membrane of A. fulgidus is primarily composed of archaeols, caldarchaeols, and MK-7 (Koga and Morii 2005)(Tarui et al. 2007)(Lai, Springstead, and Monbouquette 2008). Archaeol species include AA, archaetidylinositol (AI), and diglycosylarchaeol (DGA), and caldarchaeol species include caldarchaetidylinositol (CI), caldarchaetidic acid (CA), diglycosylcaldarchaeol (DGC), and diglycosylcaldarchaetidylinositol (DGCI) (Tarui et al. 2007). Additionally, an unidentified polar lipid is present in the membrane (Tarui et al. 2007). C55, C60, and C65 heptasaccharide-charged dolichol phosphates have been reported in A. fulgidus membranes (Taguchi, Fujinami, and Kohda 2016). The organism responds to heat and osmotic stress by increasing the content of di-myo-inositol phosphate (D1P) and diglycerol phosphate (DGP), which are rare osmolytes found only in Archaeoglobales and Aquifex bacteria (Borges et al. 2006)(Gonçalves et al. 2003).

GGR from A. fulgidus has been characterized by heterologous expression in E. coli (Murakami et al. 2007a). The enzyme noncovalently binds to FAD (Murakami et al. 2007a). Sodium dithionite and not NADPH is required as a reducing agent in the in vitro reaction for the reduction of DGGGP to AA (Murakami et al. 2007). This indicates that the enzyme likely accepts electrons from specific reducing agents, such as ferredoxins or cofactor F

420 (Murakami et al. 2007a). The locus of the gene encoding GGR contains a predicted 4Fe-4S protein upstream, AF_RS02355 (WP_048064240.1), which could possibly function as a reducer (

Figure 7A). The A. fulgidus GGR clustered with the Thermoplasma acidophilum GGR in the RMSD tree, which also contained a 4Fe-4FS encoding gene downstream in the locus (

Figure 4 and

Figure 7B). The structural model of this GGR has a similar organization of the catalytic cavity as other archaeal GGRs (

Figure 2). This organism contains three paralogs of GGR: AF_0648 (PR), AF_1023 (FixC superfamily), and AF_1637 (GG-red-SF superfamily). One archaeal GGR paralog (AF_0648) was characterized by A. fulgidus (Hemmi et al. 2005). The paralog was found to be responsible for the production of partially saturated derivatives of menaquinone-8 (MK-8) when expressed in E. coli and annotated as a menaquinone-specific PR (Hemmi et al. 2005). A cross-section across the surface of the modeled AF_PR indicates two cavities separated by Tyr150 (

Figure 7b). Cavity 1 was in close proximity to the introduced FAD cofactor in this model (

Figure 7B). This structural organization is similar to that of the archaeal GGRs (

Figure 2). Other paralogs (AF_1023 and AF_1637) were also expressed in E. coli, but this did not lead to any alteration in the quinone profiles (Hemmi et al. 2005). AF_1637 is an interesting uncharacterized protein, as it contains the PxxYxWxFP catalytic cavity associated with GGRs along with a conserved Archaeoglobales protein upstream in its locus (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7B). AF_1023 contained RxGD and LxxxD motifs associated with FAD interaction (

Figure 6).

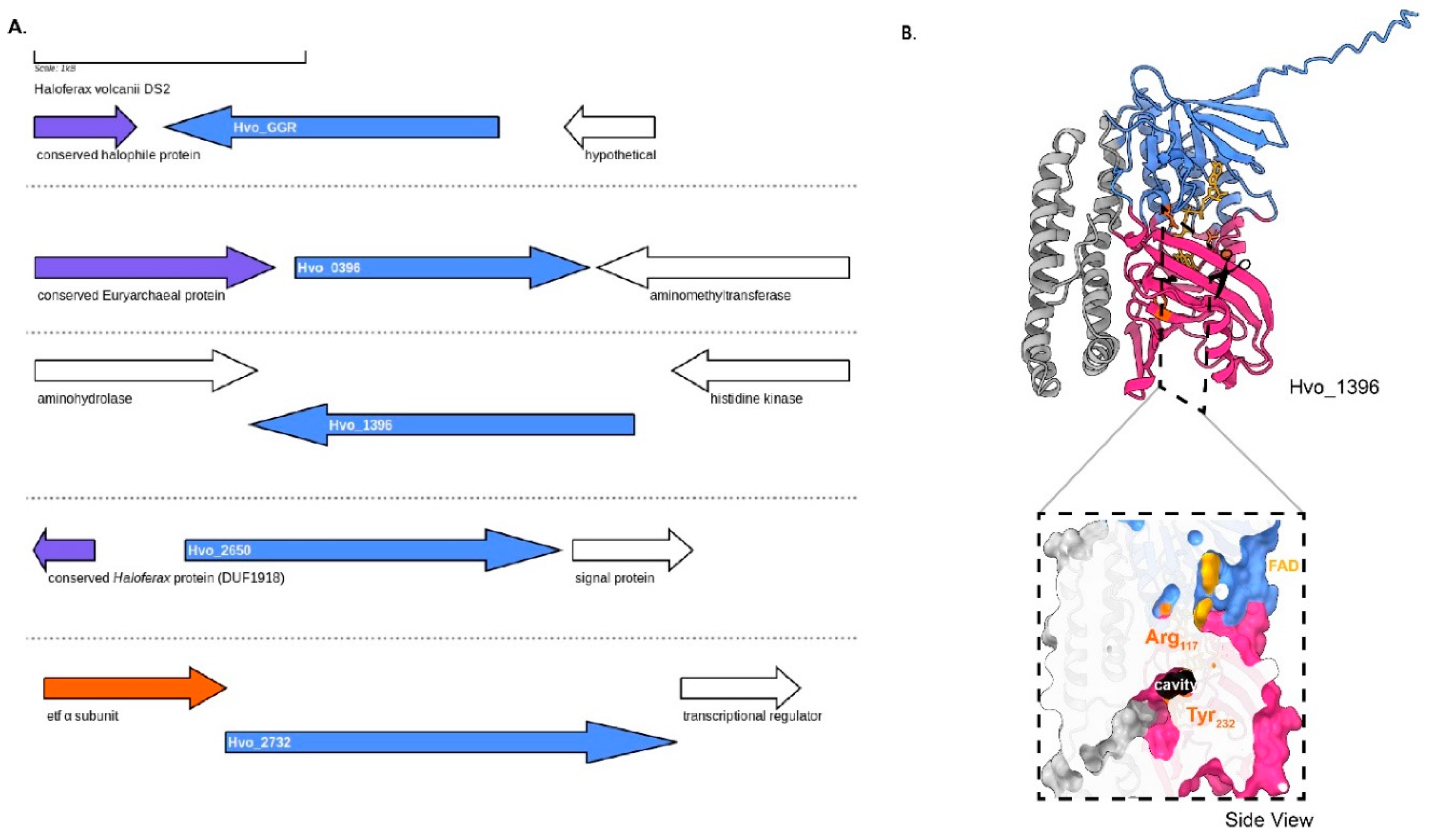

7. Haloferacles

The order Haloferacles comprises halophiles that thrive in environments approaching salt saturation, such as natural brine, alkaline salt lakes, hypersaline lakes, and marine solar salterns (Stan-Lotter and Fendrihan 2015). The membranes of these organisms contain bilayer-forming glycolipids, phospholipids, cardiolipins, carotenoids such as bacterioruberin (monolayer-like), and respiratory quinones such as menaquinone (Kellermann et al. 2016). Haloferax volcanii (optimum : 45°C, 2M NaCl) is a model organism from this order. This halophile is pleomorphic and it has been suggested that it utilizes various shapes to create turbulence in the membrane, leading to efficient diffusion (Kellermann et al. 2016). The membranes of halophiles harbor the highest content of respiratory quinones known in archaea (Kellermann et al. 2016). In particular, their membranes are dominated by MK (relative abundance:65%) and bilayer-forming glycerolipids such as AG (Kellermann et al. 2016). The impact of such a high MK content on the physiochemical properties of the haloarchaeal membrane are not known. However, molecular dynamics simulations have suggested that MK-8 increases membrane thickness, thereby increasing the membrane bending constant (Feng et al. 2021). This, in turn, allows the membrane to resist shrinkage in a hypersaline environment (Feng et al. 2021).

These membranes are one of the most negatively charged among all domains of life, considering that they also contain cardiolipins (CLs) and methylated archetidylglycerophosphate (AGP-Me) (Bale et al. 2019) (Stan-Lotter and Fendrihan 2015). The divalent negative charge of polar head groups such as AGP-Me stabilizes the trimeric structure of bacteriorhodopsins (bRs) found in halophilic membranes, while the branched methyl chains significantly enhance the affinity for bRs (Umegawa et al. 2023). Recently, acetylated phospholipid species such as acetylated archaeol and acetylated AG have been reported in the membranes of H. volcanii and Halobacterium salinarum (Kropp et al. 2022). They were found in various saturation states ranging from 1-8 to double bonds in the structure (Kropp et al. 2022). The functional significance of such polar headgroup modifications in membranes remain unclear.

The elevated contents of MKs and extremely negatively charged membranes have been hypothesized to fulfil high rates of electron transport, which would be required for energy maintenance in chronic energy stresses such as high salinity (Kellermann et al. 2016) (Valentine 2007). De-novo synthesis of CLs in Halobacterium salinarum has been experimentally correlated with hypotonic osmotic shock (from 4M NaCl to 0.1M NaCl) (Lobasso et al. 2003)(Lopalco et al. 2004). Glycocardiolipins are also known to interact with bacteriorhodopsin in halophilic membranes (Corcelli, Lattanzio, and Oren 2004).

Thus, it has been hypothesized that cardiolipins form an efficient barrier in the halophilic membrane against the high ionic levels while also stabilizing bacteriorhodopsin (Lopalco et al. 2004)(Corcelli et al. 2004). However, it must be noted that the homologs of the only identified archaeal cardiolipin synthase (Cls) from Methanospirillium hungatei are not exclusive to halophiles and are also found in crenarchaeotes such as Nitrosphaera gargensis (moderate thermophile, optimum: 46°C), hyperthermophiles such as Pyrobaculum ferrireducens (optimum: 95°C) and A. fulgidus (Exterkate et al. 2021)(Slobodkina et al. 2015)(Pitcher et al. 2010). In Haloferax mediterranei, the levels of carotenoids such as bacteroruberin increase in the membrane in response to oxidative stress (Giani and Martínez-Espinosa 2020).

Membrane modulation in halophiles is through a

LonB protease which acts on PSY, a rate limiting enzyme in carotenoid synthesis (Cerletti et al. 2018). The contents of bacterioruberins (BRs) and a few uncharacterized polar lipids have been found to increase in

LonB mutants (Cerletti et al. 2014). It is worth noting that a deletion mutant of GGR has only been obtained in

H.volcanii amongst all archaea (Naparstek, Guan, and Eichler 2012). In the absence of GGR, the organism was unable to produce saturated dolichol phosphates and diether phospholipids (Naparstek et al. 2012). Remarkably, in this mutant, partial saturation at the ω-position of the C

60 dolichol phosphate (DoIP) occured (Naparstek et al. 2012). Unsaturated molecules of AGP-Me and archaetidylglycerol (AG) were also detected in the lipidome of the deletion mutant (Naparstek et al. 2012). Growth and lipidomic analysis of this deletion mutant grown at various ranges of salinity and temperature could provide more insights about the role of saturated membranes in halophiles. A crystal structure of this GGR is not available, however, the enriched structural model with ligands shows a similar organization of the catalytic cavity as other archaeal GGRs (

Figure 2).

The genome of

H. volcanii harbors four GGR paralogs: Hvo_0396, Hvo_1396, Hvo_2650, Hvo_2732 and all of them are expressed under standard culturing conditions(Schulze et al. 2020). The GGR from

H. volcanii and Hvo_2650 genes co-localize in their locus with genes encoding conserved haloarchaeal proteins (

Figure 8A). One of the paralogs – Hvo_2732 has a conserved alpha subunit of ETF encoding gene in its locus (arCOG00447) (

Figure 8A). This protein contains the following motifs: RRKMD and LVDG, both of which are associated with FAD interaction (

Figure 6) (Nishimura and Eguchi 2006b). Hvo_0396 contains only the RxxxD motif (

Figure 6). All the structure predictions of GGR paralogs from this order are distinct, except Hvo_1396 which shares some structural conservation with the

S. acidocaldarius GGR (

Figure 4). The enriched model of Hvo_1396 shows a Tyr

232 residue separating a potential catalytic cavity (

Figure 8B).

8. Thermoproteales

Thermoproteales represent a group of strict anaerobes and sulfur dependent hyperthermophiles of the crenarchaeota order (Siebers et al. 2011). Aeropyrum pernix (optimum: 90-95°C, 3.5 % salinity) from this group produces C25,25-achaetidylinositol and C25,25-achaetidyl(glucosyl)inositol, also known as extended archaeol (Kejžar, Osojnik Črnivec, and Poklar Ulrih 2022). These extended archaeols are reduced by geranylfarsenylreductase (GFR) (Yoshida, Yoshimura, and Hemmi 2018).Remarkably, S. acidocaldarius GGR was not able to reduce the C25 extended archaeols in E. coli, suggesting that GFR is specialized for the reduction of geranylfarsenyl groups (Yoshida et al. 2018).

Thermoproteus tenax is a model organism from this order which grows optimally at 86°C, pH 5.6 (Siebers et al. 2011). The organism has a facultative chemolithoautotrophic metabolism (Siebers et al. 2011)(Zaparty et al. 2008). Not much is known about the membrane composition of

T.tenax, however, homologs of the membrane lipid biosynthetic pathway are found in the genome (Siebers et al. 2011).

T. tenax utilizes MK as electron carriers in the respiratory chain (Thurl, Buhrow, and Schäfer 1985). Specifically, three species of MKs are found in their fully saturated and mono-saturated forms in the organism: MK-4, MK-5 and MK-6 (Thurl et al. 1985). Methylated species of MK-5 and MK-6 have also been reported in the quinone fraction (Thurl et al. 1985).

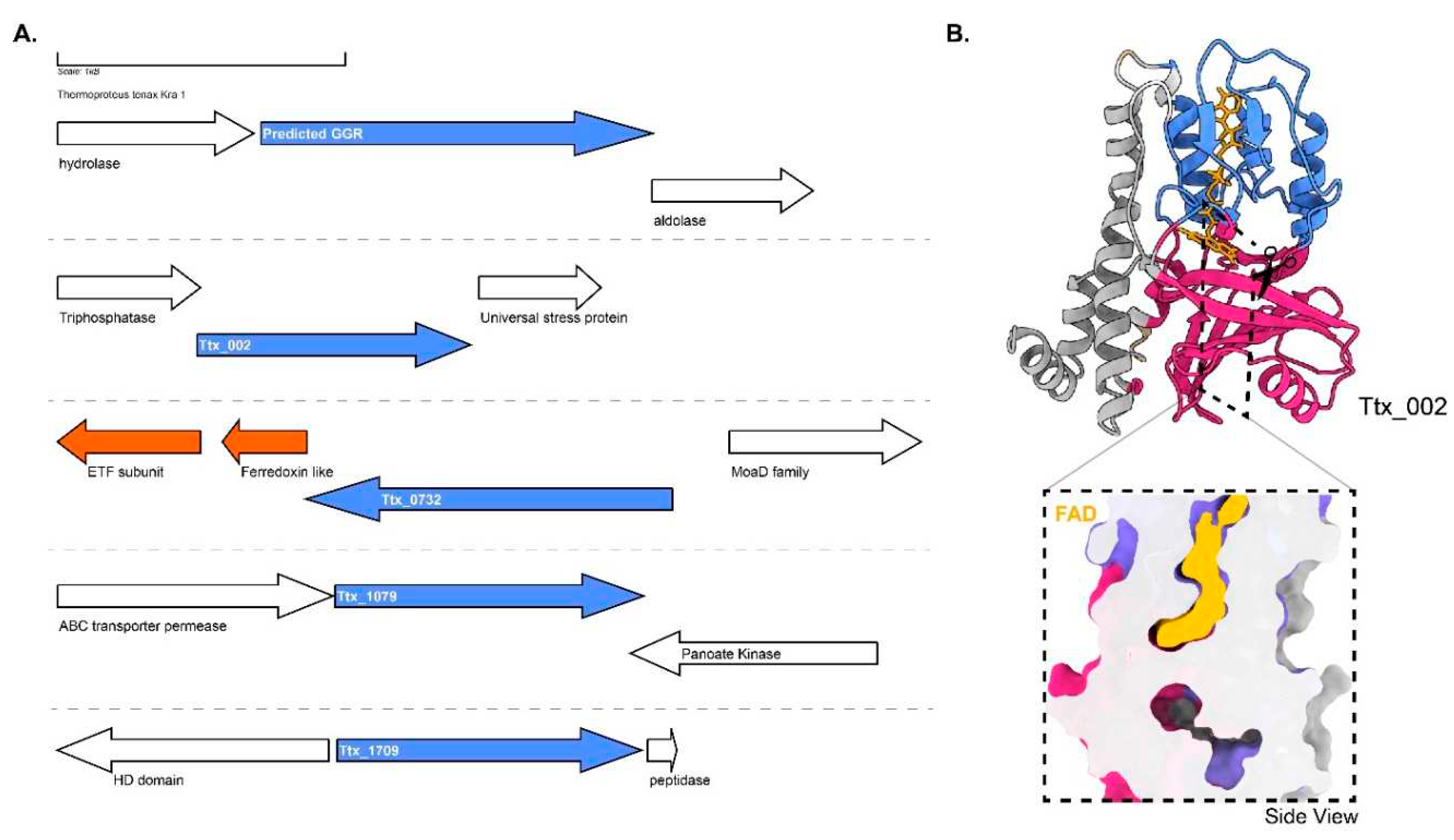

T. tenax harbors 3 GGR paralogs: Ttx_002, Ttx_0732 (PRK10157 superfamily, putative oxidoreductases) and Ttx_1709. The predicted GGR from

T. tenax does not have any ferredoxin encoding gene in its locus and shares structural similarities with the

S. acidocaldarius GGR (

Figure 4 and

Figure 6). Ttx_0732 contains a ferredoxin encoding gene (arCOG01984, conserved in haloarchaea and a few archaea from TACK superphylum) upstream in its locus (

Figure 9A). Interestingly, the AlphaFold2 prediction of this protein clusters with other archaeal GGR paralogs which also have a ferredoxin encoding gene in their locus (

Figure 4). The protein sequence of Ttx_1079 contains CxxxG and RxFD motifs (

Figure 6). Meanwhile, the sequence of Ttx_1709 includes the LxGD motif and is conserved structurally with Saci_1567, Desfe_0100 (

Figure 4 and

Figure 6). Remarkably, Ttx_002 shares structural similarities with AF_1637 and Ttx_1079 (

Figure 4). A cross-section across its enriched structural model shows a cavity, however, it is not in the vicinity of FAD (

Figure 9B).

9. Desulfurococcales

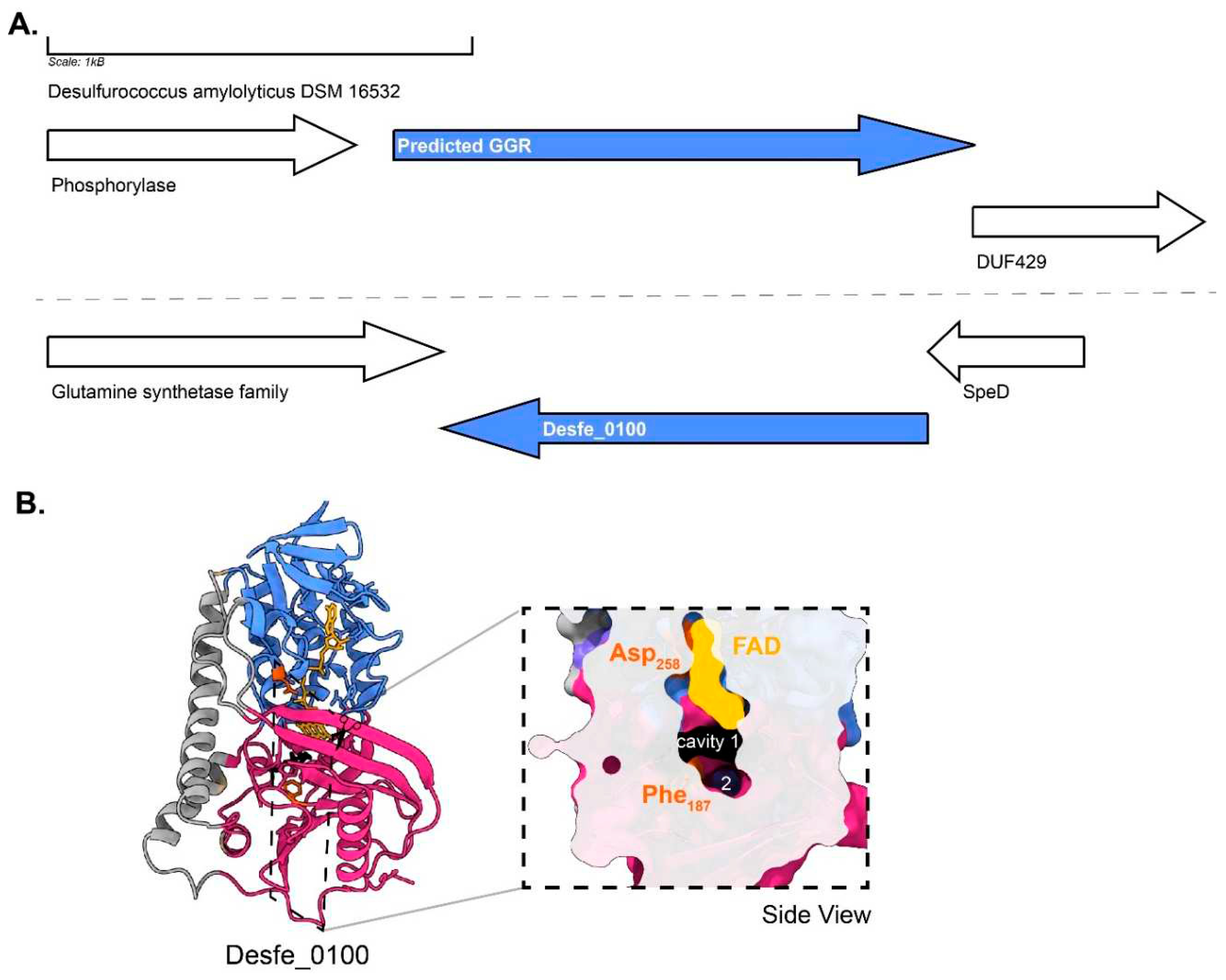

Organisms belonging to Desulfurococcales are hyperthermophiles which are obligate anaerobes and organoheterotrophs (Perevalova et al. 2005).

Desulfurococcus amylolyticus (formerly known as

D. fermentans) is a representative organism from this order which is able to metabolize formate (Ergal et al. 2020)(Perevalova et al. 2016). The optimum growth is observed between 80-82°C, pH 6.0 (Perevalova et al. 2005). The membrane composition of organisms from this order remains unknown, however, genes for the archaeal lipid biosynthetic pathway (including Tes) have been found in the genome (Perevalova et al. 2005). This archaeon harbors some unique quinone species whose structures have not yet been resolved (THURL et al. 1986). The genome contains the predicted GGR (Desfe_0234) and one paralog (Desfe_0100) (Perevalova et al. 2016). The AlphaFold2 prediction of Desfe_0100 clusters with the

S. acidocaldarius GGR (

Figure 4). The enriched model of this paralog shows a Phe187 residue dividing a potential catalytic cavity into two (

Figure 10B). Cavity 1 is in the close vicinity of FAD (

Figure 10B). The characteristic PxxYxWxFP motif is conserved in Desfe_0234 corresponding to the GGR catalytic cavity (

Figure 6). Interestingly, none of the motifs associated with FAD interaction are conserved in these proteins and the genomic locus does not have ferredoxins or iron-sulphur cluster binding proteins in the neighborhood (

Figure 6 and

Figure 10).

10. Thermococcales

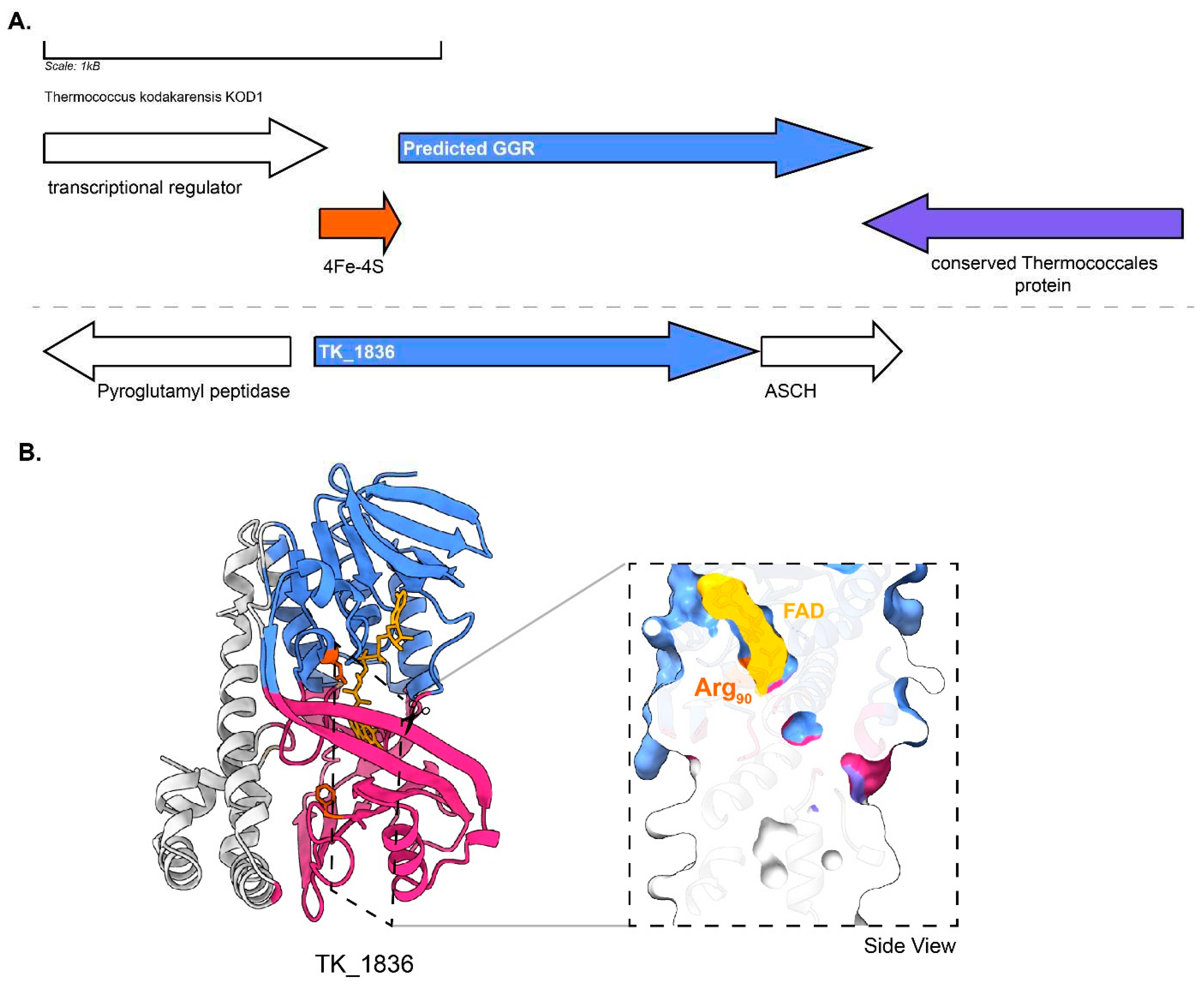

Organisms from this order comprise marine hyperthermophiles which thrive at high temperatures and high salt conditions. Thermococcus kodakarensis is a model organism from this order. The membrane of this organism consists of ~50% DGDs and ~50% DGTs at the start of the stationary phase (Gagen et al. 2016). In the stationary phase, the membrane is dominated by GDGT lipids which constitute ~70% of the membrane (Gagen et al. 2016). Trace amounts of unsaturated GDGTs have also been reported in the membrane (Bauersachs et al. 2015). T. kodakarensis is assumed to regulate its membrane fluidity by altering the length of hydrocarbon chains of the membrane phospholipids (Matsuno et al. 2009). Apart from membrane phospholipids, apolar polyisoprenoids corresponding to lycopene are found in minor fractions in the T. hydrothermalis and T. barophilus lipidome (Salvador-Castell et al. 2019). In T. hydrothermalis, four acyclic tetrapernoid hydrocarbons in their di-saturated and tri-saturated forms were identified (Lattuati et al. 1998). The T. barophilus membrane contains polyunsaturated species of C30 squalane and C35, C40 lycopene (Cario et al. 2015). The relative abundance of C40:4 squalene increases slightly at low temperature and high hydrostatic pressure (Lattuati et al. 1998). Meanwhile, the levels of C40:2 squalene increases at high temperature and C40:3 decreases at low temperature (Cario et al. 2015). The exact localization of squalene and lycopene in membranes remains unclear. However, a study using neutron diffraction has shown that squalene resides in the midplane of a synthetic membrane consisting of 1,2-di-O-phytanyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DoPhPC) and 1,2-di-O-phytanyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanol-amine (DoPhPE) (Salvador-Castell et al. 2021). Lipid unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) consisting of the aforementioned lipids with 1 mol% of squalene had lower permeability to protons but increased permeability to water (Salvador-Castell et al. 2021).

The predicted GGR (TK1088) from

T. kodakarensis has 4Fe-4S binding protein (arCOG00958, conserved in thermophilic methanogenic archaea and other euryarchaeota) upstream in the locus (

Figure 11). The protein sequence comprises of the catalytic PxxYxWxFP and the LxGD domains (

Figure 3). The AlphaFold2 structure of this GGR clusters with the

A. fulgidus and

T. acidophilum counterparts in the RMSD tree (

Figure 4). All known species of Thermococcales harbor 1 GGR paralog: TK1836 (FixC superfamily) (Bauersachs et al. 2015). TK1836 contains the LxGD motif in its sequence and shares structural similarities with other paralogs from

T. acidophilum and

Methanoccocus maripaludis (

Figure 4 and

Figure 6).

11. Thermoplasmalates

Thermoplasma acidophilum was isolated from a self-heating coal refuse pile in 1970 and was classified as a thermoacidophilic organism (Stern et al. 1992). The organism is a facultative anaerobe with an optimum growth temperature at 59°C and pH of 1-2 (Ruwart and Haug 1975). The membrane is composed of apolar lipids, glycolipids and glycophospholipids wherein the main constituent is the membrane-spanning DGT (Stern et al. 1992). The quinone species found in the organism include: cis and trans isomers of thermoplasmaquinone (TPQ-7), MK-7 and unsaturated species of methylthio-1, 4-naphthoquinone (MTK-7) (Shimada et al. 2001). The abundance of all quinones is similar under aerobic growth conditions (Shimada et al. 2001). However, TPQ-7 dominates (97%) when the organism is grown anaerobically (Shimada et al. 2001). Apolar polyisoprenoids with C16-C20 have also been reported in the membrane (Holzer et al. 1979).

The GGR from

T. acidophilum is a membrane-associated and stereospecific as it has a preference for the addition of hydrogen in a

syn manner to DGGGP (Xu et al. 2010)(Nishimura and Eguchi 2007). The crystal structure of this GGR was obtained with a bound FAD molecule in extended conformation (Xu et al. 2010) (

Figure 2A). The structure from

T. acidophilum lacks the amphiphatic α-helices found in the

S. acidocaldarius enzyme (Nishimura and Eguchi 2006b) (

Figure 2A). Enzymatic assays confirmed the essentiality of co-factors like FAD and NADH to catalyze the reduction of DGGGP (Nishimura and Eguchi 2006). The genomic locus of the

T. acidophilum GGR contains a 4Fe-4S domain protein (arCOG00958, conserved in Euryarchaeota and Thermoproteus), it is likely that this protein fulfils the role of a reducer

in-vivo (

Figure 12).

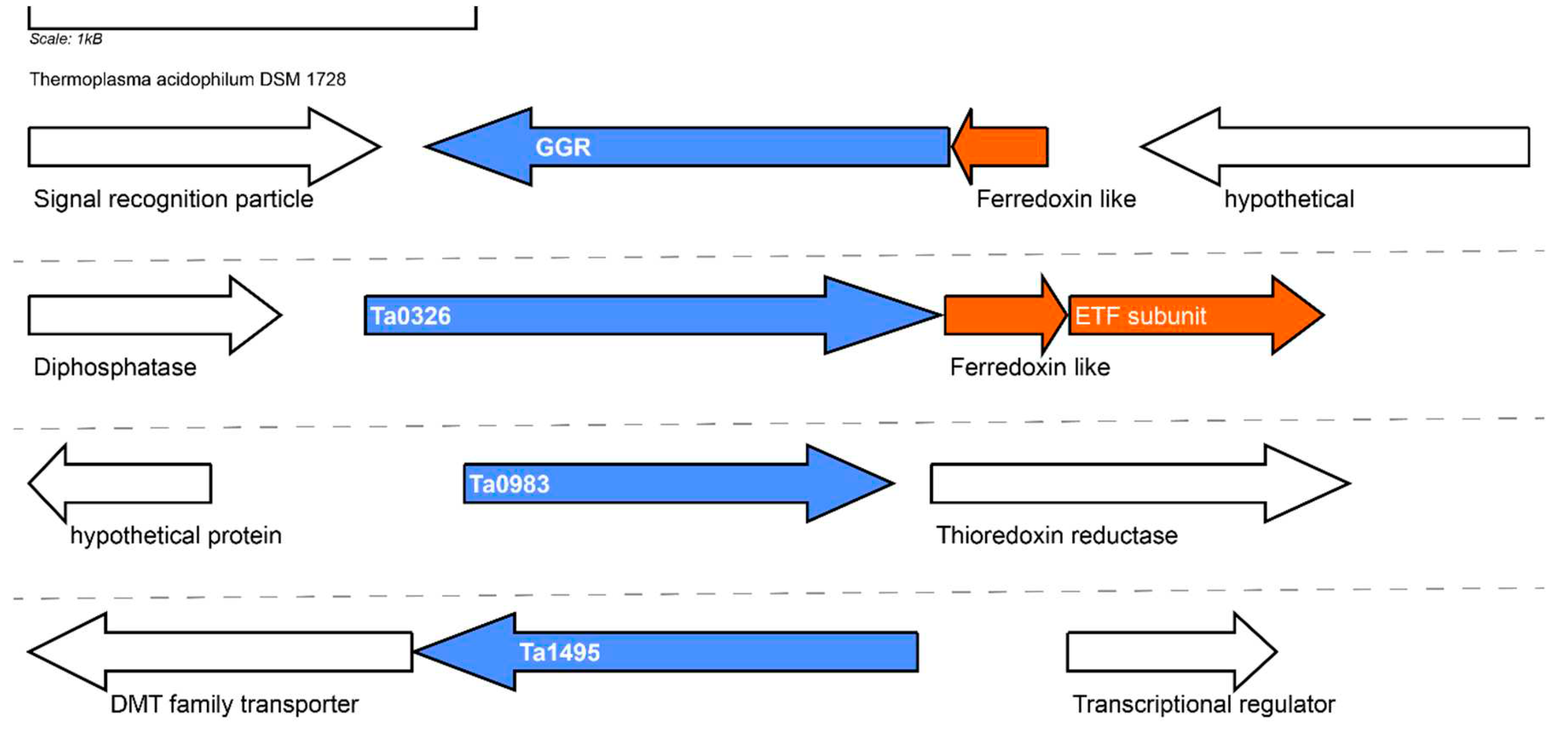

The genome of

T. acidophilum contains 3 GGR paralogs: Ta0326, Ta0983 and Ta1495. Ta0326 contains a ferredoxin-like protein (Ta0327) just downstream in its locus corresponding to arCOG01984 (conserved in Euryarchaeotes and organisms from the TACK superphylum) (

Figure 12). Additionally, an ETF β subunit (arCOG00446, conserved in halophiles and TACK superphylum) is present in the locus (

Figure 12). The AlphaFold model of Ta0326 clusters with other archaeal GGR orthologs with either ETF or ferredoxin encoding genes in their locus (

Figure 5). Conserved motifs associated with FAD interaction (RxxD and LxGD) are found only in Ta0326 and Ta1495 (

Figure 3). Ta0983 does not have any ferredoxin or electron transfer subunits in its locus (

Figure 12). However, Ta0982 in the locus is a protein of unknown function present just in

T.acidophilum and

T.volcanium (

Figure 12). The genomic organization and AlphaFold prediction of Ta0983 is similar to the MK specific PR from

A.fulgidus (

Figure 4 and

Figure 12). Thus, this protein could be a putative prenyl reductase for MK.

12. Methanococcales

Methanococcales is an order consisting of anaerobic methanogens which can grow in a broad temperature (<20 – 88°C) and pH (4.5-9.8) range (Angelidaki et al. 2011)(Thauer et al. 2008). Methanococcus maripaludis is a well-studied model organism from this order due to its hydrogenotrophic metabolism which can convert CO2 and H2 to CH4 (Goyal, Zhou, and Karimi 2016). The organism is mesophilic (optimum: 38°C) and the membrane of M. maripaludis consists of bilayer forming archaeols and hydroxyarchaeols with galactose or N-acetylglucoamine or serine headgroups (Y Koga et al. 1998). Monolayer forming GDGTs have not been detected in the lipid extracts from the membrane (Goyal et al. 2016). Apolar polyisoprenoids consisting of C15 and C18 chains have been reported in the membrane of M.vannielli (Holzer et al. 1979).

Thermophilic methanogens such as Methanothermoccus okinawensis (optimum: 65°C, pH 6.7) and Methanothermobacter marburgensis (optimum:65°C) contain archaeols (with and without cyclopentane rings), isomers of glycerol monoalkyl glycerol tetraether (GMGT), GDGTs and glycerol trialkyl glycerol tetraether (GTGT) in the membrane (Taubner et al. 2019)(Baumann et al. 2022). A switch to glycolipids from phospholipids has been observed under nutrient limitation conditions in Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus (Yoshinaga et al. 2015). Additionally, an increase in polyprenols consisting of 9-11 isoprene units was observed during conditions of energy limitation (H2) (Yoshinaga et al. 2015). The production of these phosphate-free polyprenols has been hypothesized to biochemically stabilize membranes (Hartmann and König 1990).

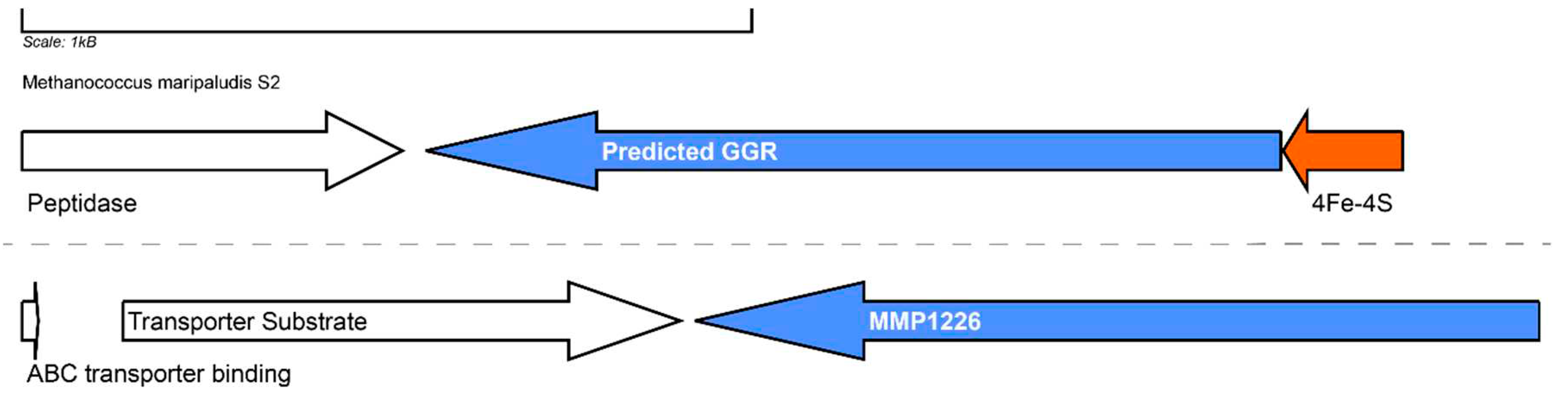

Mesophilic methanogens (such as

M. maripaludis) harbor one GGR paralog: MMP1266 (FixC superfamily) whereas thermophilic methanogens (such as

Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus) have two GGRs (MTH_277 and MTH_1718) and one paralog (MTH_725) in the genome (Goyal et al. 2016)(Yoshinaga et al. 2015). The predicted GGR from

M. maripaludis contains a ferredoxin encoding gene in its locus and the characteristic PxxYxWxFP catalytic motif, however it lacks the motifs associated with FAD interaction (

Figure 6 and

Figure 13). Interestingly, both the AlphaFold predictions of the GGR (MMP0388) and its paralog (MMP1226) from

M. maripaludis cluster close to their

T. acidophilum and

A. fulgidus counterparts in the RMSD tree (

Figure 4). The RxFD and LxGD conserved motifs are present in MMP1226 (

Figure 6).

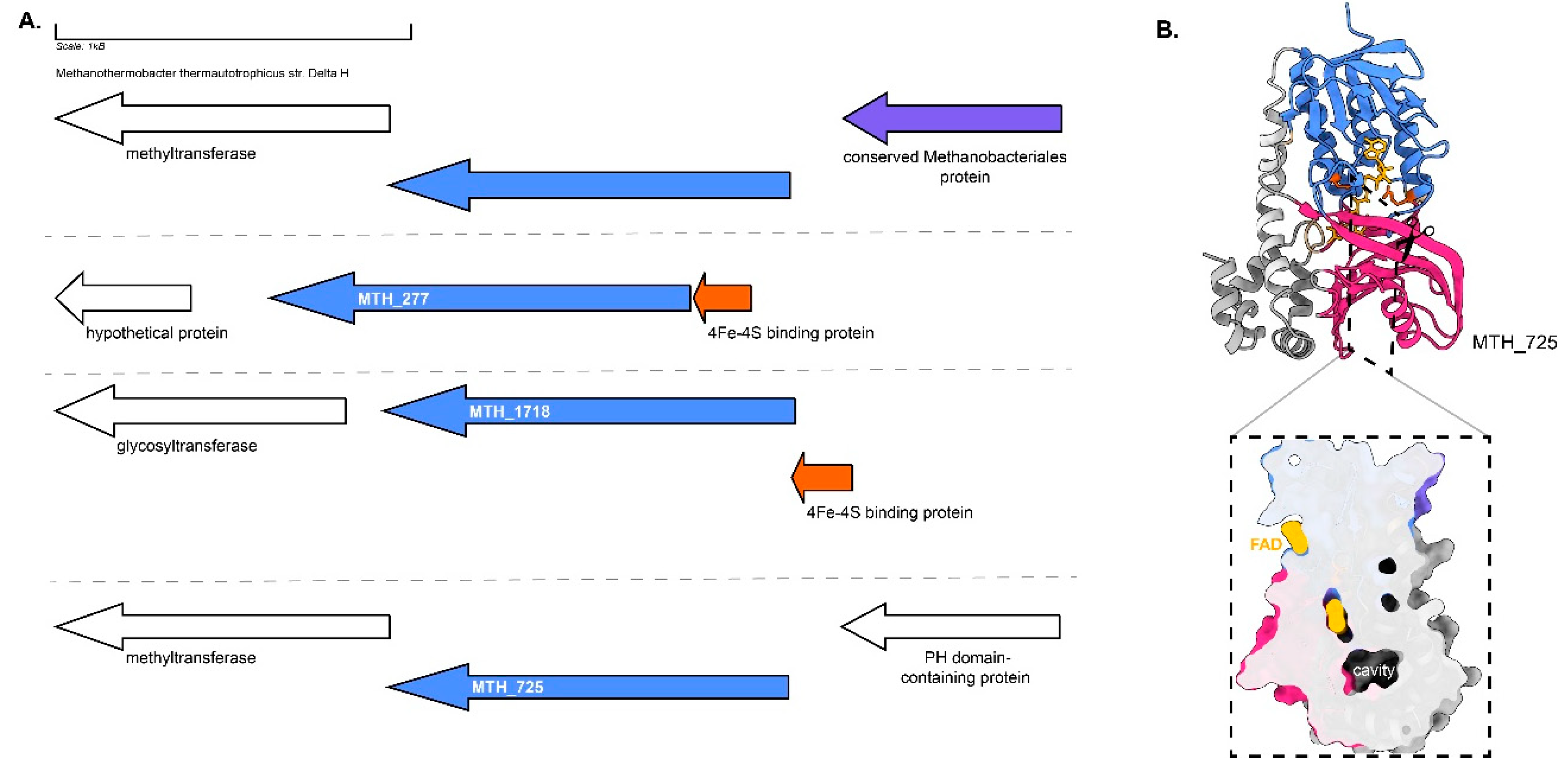

Both MTH_277 and MTH_1718 contain a 4Fe-4S binding protein in their locus (

Figure 14A). MTH_277 and MTH_1718 are structurally similar to GGRs from

M. acetivorans,

T. acidophilum and

A. fulgidus (

Figure 4). Both these proteins have all the FAD associated motifs conserved in their sequence (

Figure 6). However, only MTH_1718 contains the catalytic PxxYxWxFP cavity associated with GGRs (

Figure 6). The paralog MTH_725 shares some structural conservation with AF_1023 and contains FAD associated motifs just like the latter (

Figure 4 and

Figure 6). A cross-section across the surface of the enriched MTH_725 model shows a cavity in close vicinity of the FAD molecule (

Figure 14B).

13. Concluding Remarks

There have been considerable advancements in elucidating the biosynthetic pathways of membrane phospholipids in archaea. However, the role and biosynthetic pathways of the various polyterpenes in archaea remains to be investigated. The majority of these polyterpenes have been hypothesized to function in a similar fashion as their bacterial counterparts since

in-vivo and

in-vitro studies of these molecules; there is little information about their exact localization and their impact on the membrane. GGR is an enzyme that plays a key role in the saturation of the isoprenoid chains of the phospholipids, however, this group of proteins is also involved in the biosynthesis of other lipophilic compounds. The saturation states of polyterpenes (

Figure 15) has been correlated with the multiplicity of GGRs in archaeal genomes which are represented by the arCOG00570.

GGRs are promiscuous enzymes and recent studies have shown that the chain length of the substrate seems to be a regulatory factor for catalysis (Cervinka et al. 2021b)(Yoshida et al. 2018). Therefore, it is possible that archaeal GGR paralogs fulfil this void and act on polyterpenes with longer chain lengths for saturation such as quinones, polyprenols, apolar polyisoprenoids and carotenoids. None of the GGR paralogs listed in this study contain a signal peptide for secretion, thereby suggesting a cytosolic localization. Preliminary bioinformatics analysis into enriched structural models and sequence alignments combined with extant information from literature reveals that these GGR paralogs are quite diverse structurally and likely functionally. Transcriptomic and proteomic datasets of S. acidocaldarius and H.volcanii indicate that the GGRs are well expressed proteins under standard laboratory conditions (Cohen et al. 2016) (Schulze et al. 2020). Interestingly, some of these paralogs along with a few archaeal GGRs co-localize in clusters together with genes encoding ferredoxin or electron transfer proteins that may function as reducing agents and add to the electron transfer. Future study of these proteins should reveal their exact functions as well as their interactions. This should also involve genetic studies to address whether GGRs are essential proteins.

Funding Information

This research was funded by the University of Groningen and the Netherlands Organization for the Advancement of Science (NWO) through the “BaSyC – Building a Synthetic Cell” Gravitation grant (024.003.019) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Madhurya Lutikurti for the help with visualization of protein structures and active sites in ChimeraX

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict(s) of interest

Abbreviations

| GGR |

geranylgeranylreductase |

| G1P |

glycerol-1-phosphate |

| G3P |

glycerol-3-phosphate |

| IPP |

isopentenyl pyrophosphate |

| DMAPP |

dimethylallyl pyrophosphate |

| GGPP |

geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate |

| GGPPS |

GGPP synthase |

| GGGP |

geranylgeranyl glycerol phosphate |

| GGGPS |

GGGP synthase |

| DGGGP |

digeranylgeranyl glyceryl phosphate |

| DGGGPS |

DGGGP synthase |

| AA |

archaetidic acid |

| DGD |

dialkyl glycerol diether |

| AG |

archaetidylglycerol |

| CDP-archaeol |

cytidine diphosphate archaeol |

| GDGT |

glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers |

| GDNT |

glycerol dialkyl nonnitol tetraether |

| GMGT |

glycerol monoalkyl glycerol tetreather |

| GTGT |

glycerol trialkyl glycerol tetrather |

| AF_PR |

Archaeoglobus fulgidus prenyl reductase |

| MK |

menaquinone |

| CQ |

caldariellaquinone |

| DoIP |

dolichol phosphate |

| SQ |

sulfoquinone |

References

- Abe, Tohru, Mariko Hakamata, Akihito Nishiyama, Yoshitaka Tateishi, Sohkichi Matsumoto, Hisashi Hemmi, Daijiro Ueda, and Tsutomu Sato. 2022. “Identification and Functional Analysis of a New Type of Z,E -mixed Prenyl Reductase from Mycobacteria.” The FEBS Journal 289(16):4981–97.

- Allen, Michelle A., Federico M. Lauro, Timothy J. Williams, Dominic Burg, S. Khawar, Davide De Francisci, Kevin W. Y. Chong, Oliver Pilak, Hwee H. Chew, Z. Matthew, De Maere, Lily Ting, Marilyn Katrib, Charmaine Ng, Kevin R. Sowers, Michael Y. Galperin, Iain J. Anderson, Natalia Ivanova, Eileen Dalin, Michele Martinez, Alla Lapidus, Miriam Land, Torsten Thomas, and Ricardo Cavicchioli. 2009. “The Genome Sequence of the Psychrophilic Archaeon , Methanococcoides Burtonii : The Role of Genome Evolution in Cold - Adaptation School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences , The University of New South Wales , Centre for Marine Bio - Innovation ,.” The ISME Journal 3(9):1012–35.

- Angelidaki, Irini, Dimitar Karakashev, Damien J. Batstone, Caroline M. Plugge, and Alfons J. M. Stams. 2011. “Biomethanation and Its Potential.” Pp. 327–51 in Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 494. Academic Press Inc.

- Baker, Brett J., Valerie De Anda, Kiley W. Seitz, Nina Dombrowski, Alyson E. Santoro, and Karen G. Lloyd. 2020. “Diversity, Ecology and Evolution of Archaea.” Nature Microbiology 5(7):887–900.

- Balch, William E., Linda J. Magrum, George E. Fox, Ralph S. Wolfe, and Carl R. Woese. 1977. “An Ancient Divergence among the Bacteria.” Journal of Molecular Evolution 9(4):305–11.

- Bale, Nicole J., Dimitry Y. Sorokin, Ellen C. Hopmans, Michel Koenen, W. C. Irene Rijpstra, Laura Villanueva, Hans Wienk, and Jaap S. Sinninghe Damsté. 2019. “New Insights into the Polar Lipid Composition of Extremely Halo(Alkali)Philic Euryarchaea from Hypersaline Lakes.” Frontiers in Microbiology 10(MAR):377. [CrossRef]

- Bauersachs, Thorsten, Katrin Weidenbach, Ruth A. Schmitz, and Lorenz Schwark. 2015. “Distribution of Glycerol Ether Lipids in Halophilic, Methanogenic and Hyperthermophilic Archaea.” Organic Geochemistry 83–84:101–8.

- Baumann, Lydia M. F., Ruth-Sophie Taubner, Kinga Oláh, Ann-Cathrin Rohrweber, Bernhard Schuster, Daniel Birgel, and Simon K. M. R. Rittmann. 2022. “Quantitative Analysis of Core Lipid Production in Methanothermobacter Marburgensis at Different Scales.” Bioengineering 9(4):169. [CrossRef]

- Beeder, J., R. K. Nilsen, J. T. Rosnes, T. Torsvik, and T. Lien. 1994. “Archaeoglobus Fulgidus Isolated from Hot North Sea Oil Field Waters.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 60(4):1227–31. [CrossRef]

- Bischof, Lisa F., M. Florencia Haurat, Lena Hoffmann, Andreas Albersmeier, Jacqueline Wolf, Astrid Neu, Trong Khoa Pham, Stefan P. Albaum, Tobias Jakobi, Stefan Schouten, Meina Neumann-Schaal, Phillip C. Wright, Jörn Kalinowski, Bettina Siebers, and Sonja-Verena Albers. 2019. “Early Response of Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius to Nutrient Limitation.” Frontiers in Microbiology 9:3201. [CrossRef]

- Borges, Nuno, Luis G. Gonçalves, Marta V. Rodrigues, Filipa Siopa, Rita Ventura, Christopher Maycock, Pedro Lamosa, and Helena Santos. 2006. “Biosynthetic Pathways of Inositol and Glycerol Phosphodiesters Used by the Hyperthermophile Archaeoglobus Fulgidus in Stress Adaptation.” Journal of Bacteriology 188(23):8128–35. [CrossRef]

- Caforio, Antonella, Melvin F. Siliakus, Marten Exterkate, Samta Jain, Varsha R. Jumde, Ruben L. H. Andringa, Servé W. M. Kengen, Adriaan J. Minnaard, Arnold J. M. Driessen, and John van der Oost. 2018. “Converting Escherichia Coli into an Archaebacterium with a Hybrid Heterochiral Membrane.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115(14):3704–9.

- Cario, Anaïs, Vincent Grossi, Philippe Schaeffer, and Philippe M. Oger. 2015. “Membrane Homeoviscous Adaptation in the Piezo-Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Thermococcus Barophilus.” Frontiers in Microbiology 6(OCT):1152. [CrossRef]

- De Castro, Rosana E., Micaela Cerletti, Agustín Rabino, Roberto A. Paggi, Celeste C. Ferrari, Ansgar Poetsch, Harri Savilahti, and Saija Kiljunen. 2022. “ The C-Terminal Region of Phytoene Synthase Is a Key Element to Control Carotenoid Biosynthesis in the Haloarchaeon Haloferax Volcanii .” Biochemical Journal 479(22).

- Cerletti, Micaela, María J. Martínez, María I. Giménez, Diego E. Sastre, Roberto A. Paggi, and Rosana E. De Castro. 2014. “The LonB Protease Controls Membrane Lipids Composition and Is Essential for Viability in the Extremophilic Haloarchaeon Haloferax Volcanii.” Environmental Microbiology 16(6):1779–92. [CrossRef]

- Cerletti, Micaela, Roberto Paggi, Christian Troetschel, María Celeste Ferrari, Carina Ramallo Guevara, Stefan Albaum, Ansgar Poetsch, and Rosana De Castro. 2018. “LonB Protease Is a Novel Regulator of Carotenogenesis Controlling Degradation of Phytoene Synthase in Haloferax Volcanii.” Journal of Proteome Research 17(3):1158–71. [CrossRef]

- Cervinka, Richard, Daniel Becker, Steffen Lüdeke, Sonja Verena Albers, Thomas Netscher, and Michael Müller. 2021a. “Enzymatic Asymmetric Reduction of Unfunctionalized C=C Bonds with Archaeal Geranylgeranyl Reductases.” ChemBioChem 22(17):2693–96. [CrossRef]

- Cervinka, Richard, Daniel Becker, Steffen Lüdeke, Sonja Verena Albers, Thomas Netscher, and Michael Müller. 2021b. “Enzymatic Asymmetric Reduction of Unfunctionalized C=C Bonds with Archaeal Geranylgeranyl Reductases.” ChemBioChem 22(17):2693–96. [CrossRef]

- Chong, Parkson L. G., Alexander Bonanno, and Umme Ayesa. 2017. “Dynamics and Organization of Archaeal Tetraether Lipid Membranes.” Membrane Oganization and Dynamics 20:243–58. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Ofir, Shany Doron, Omri Wurtzel, Daniel Dar, Sarit Edelheit, Iris Karunker, Eran Mick, and Rotem Sorek. 2016. “Comparative Transcriptomics across the Prokaryotic Tree of Life.” Nucleic Acids Research 44(W1):W46–53. [CrossRef]

- Corcelli, Angela, Veronica M. T. Lattanzio, and Aharon Oren. 2004. “The Archaeal Cardiolipins of the Extreme Halophiles.” Pp. 205–14 in Halophilic Microorganisms. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Crooks, Gavin E., Gary Hon, John Marc Chandonia, and Steven E. Brenner. 2004. “WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator.” Genome Research 14(6):1188–90.

- Dannenmuller, O., K. Arakawa, T. Eguchi, K. Kakinuma, S. Blanc, A. M. Albrecht, M. Schmutz, Y. Nakatani, and G. Ourisson. 2000. “Membrane Properties of Archaeal Macrocyclic Diether Phospholipids.” Chemistry (Weinheim an Der Bergstrasse, Germany) 6(4):645–54. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, Katherine S., Katherine H. Freeman, and Jennifer L. Macalady. 2012. “Molecular Characterization of Core Lipids from Halophilic Archaea Grown under Different Salinity Conditions.” Organic Geochemistry 48:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Runze, Zhenling Peng, Yang Zhang, and Jianyi Yang. 2018. “MTM-Align: An Algorithm for Fast and Accurate Multiple Protein Structure Alignment” edited by A. Valencia. Bioinformatics 34(10):1719–25.

- DDong, Xiu Zhu, and Zi Juan Chen. 2012. “Psychrotolerant Methanogenic Archaea: Diversity and Cold Adaptation Mechanisms.” Science China Life Sciences 55(5):415–21. [CrossRef]

- Driessen, Arnold J. M. M., and Sonja-Veerana Sonja-Verena Albers. 2007. “Membrane Adaptations of (Hyper)Thermophiles to High Temperatures.” Pp. 104–16 in Physiology and Biochemistry of Extremophiles, edited by C. Gerday and N. Glansdorff. ASM Press.

- Eguchi, Yukinori. 2011. “PHYLIP-GUI-Tool (PHYGUI): Adapting the Functions of the Graphical User Interface for the PHYLIP Package.” Journal of Biomedical Science and Engineering 04(02):90–93. [CrossRef]

- Elling, Felix J., Kevin W. Becker, Martin Könneke, Jan M. Schröder, Matthias Y. Kellermann, Michael Thomm, and Kai Uwe Hinrichs. 2016. “Respiratory Quinones in Archaea: Phylogenetic Distribution and Application as Biomarkers in the Marine Environment.” Environmental Microbiology 18(2):692–707. [CrossRef]

- Ergal, Ipek, Barbara Reischl, Benedikt Hasibar, Lokeshwaran Manoharan, Aaron Zipperle, Günther Bochmann, Werner Fuchs, and Simon K. M. R. Rittmann. 2020. “Formate Utilization by the Crenarchaeon Desulfurococcus Amylolyticus.” Microorganisms 8(3):454. [CrossRef]

- Exterkate, Marten, Niels A. W. De Kok, Ruben L. H. Andringa, Niels H. J. Wolbert, Adriaan J. Minnaard, and Arnold J. M. Driessen. 2021. “A Promiscuous Archaeal Cardiolipin Synthase Enables Construction of Diverse Natural and Unnatural Phospholipids.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 296. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Shasha, Ruixing Wang, Richard W. Pastor, Jeffery B. Klauda, and Wonpil Im. 2021. “Location and Conformational Ensemble of Menaquinone and Menaquinol, and Protein-Lipid Modulations in Archaeal Membranes.” Journal of Physical Chemistry B 125(18):4714–25.

- Gagen, Emma J., Marcos Y. Yoshinaga, Franka Garcia Prado, Kai-Uwe Uwe Hinrichs, and Michael Thomm. 2016. “The Proteome and Lipidome of Thermococcus Kodakarensis across the Stationary Phase.” Archaea 2016:1–15.

- Giani, Micaela, and Rosa María Martínez-Espinosa. 2020. “Carotenoids as a Protection Mechanism against Oxidative Stress in Haloferax Mediterranei.” Antioxidants 9(11):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Giani, Micaela, Jose María Miralles-Robledillo, Gloria Peiró, Carmen Pire, and Rosa María Martínez-Espinosa. 2020. “Deciphering Pathways for Carotenogenesis in Haloarchaea.” Molecules 25(5). [CrossRef]

- Gmajner, Dejan, Ajda Ota, Marjeta Šentjurc, and Nataša Poklar Ulrih. 2011. “Stability of Diether C25,25 Liposomes from the Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Aeropyrum Pernix K1.” Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 164(3):236–45. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, LuÃ-s G., Robert Huber, Milton S. Costa, and Helena Santos. 2003. “ A Variant of the Hyperthermophile Archaeoglobus Fulgidus Adapted to Grow at High Salinity .” FEMS Microbiology Letters 218(2):239–44.

- Gonthier, Isabelle, Marie Noëlle Rager, Pierre Metzger, Jean Guezennec, and Claude Largeau. 2001. “A Di-O-Dihydrogeranylgeranyl Glycerol from Thermococcus S 557, a Novel Ether Lipid, and Likely Intermediate in the Biosynthesis of Diethers in Archæa.” Tetrahedron Letters 42(15):2795–97.

- Goodchild, Amber, Neil F. W. Saunders, Haluk Ertan, Mark Raftery, Michael Guilhaus, Paul M. G. Curmi, and Ricardo Cavicchioli. 2004. “A Proteomic Determination of Cold Adaptation in the Antarctic Archaeon, Methanococcoides Burtonii.” Molecular Microbiology 53(1):309–21.

- Goyal, Nishu, Zhi Zhou, and Iftekhar A. Karimi. 2016. “Metabolic Processes of Methanococcus Maripaludis and Potential Applications.” Microbial Cell Factories 15(1):107. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Ziqiang, Antonia Delago, Phillip Nußbaum, Benjamin Meyer, Sonja-Verena Albers, and Jerry Eichler. 2016. “N-Glycosylation in the Thermoacidophilic Archaeon Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius Involves a Short Dolichol Pyrophosphate Carrier.” FEBS Letters 590(18):3168–78.

- Guan, Ziqiang, Benjamin H. Meyer, Sonja Verena Albers, and Jerry Eichler. 2011. “The Thermoacidophilic Archaeon Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius Contains an Unsually Short, Highly Reduced Dolichyl Phosphate.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1811(10):607–16.

- Hafenbradl, Doris, Martin Keller, Ralf Thiericke, and Karl O. Stetter. 1993. “A Novel Unsaturated Archaeal Ether Core Lipid from the Hyperthermophile Methanopyrus Kandleri.” Systematic and Applied Microbiology 16(2):165–69. [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, Jeppe, Konstantinos D. Tsirigos, Mads Damgaard Pedersen, José Juan Almagro Armenteros, Paolo Marcatili, Henrik Nielsen, Anders Krogh, and Ole Winther. 2022. “DeepTMHMM Predicts Alpha and Beta Transmembrane Proteins Using Deep Neural Networks.” BioRxiv 2022.04.08.487609.

- Harrison, Katherine J., Valérie De Crécy-Lagard, and Rémi Zallot. 2018. “Gene Graphics: A Genomic Neighborhood Data Visualization Web Application.” Bioinformatics 34(8):1406–8.

- Hartmann, E., and H. König. 1990. “Comparison of the Biosynthesis of the Methanobacterial Pseudomurein and the Eubacterial Murein.” Naturwissenschaften 77(10):472–75. [CrossRef]

- Hekkelman, Maarten L., Ida de Vries, Robbie P. Joosten, and Anastassis Perrakis. 2023. “AlphaFill: Enriching AlphaFold Models with Ligands and Cofactors.” Nature Methods 20(2):205–13. [CrossRef]

- Hemmi, Hisashi, Yoshihiro Takahashi, Kyohei Shibuya, Toru Nakayama, and Tokuzo Nishino. 2005. “Menaquinone-Specific Prenyl Reductase from the Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Archaeoglobus Fulgidus.” Journal of Bacteriology 187(6):1937–44. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Plaza, Ana, Damian Szklarczyk, Jorge Botas, Carlos P. Cantalapiedra, Joaquín Giner-Lamia, Daniel R. Mende, Rebecca Kirsch, Thomas Rattei, Ivica Letunic, Lars J. Jensen, Peer Bork, Christian von Mering, and Jaime Huerta-Cepas. 2022. “EggNOG 6.0: Enabling Comparative Genomics across 12 535 Organisms.” Nucleic Acids Research 51(D1):D389–94. [CrossRef]

- Holzer, Guther, J. Oró, and T. G. Tornabene. 1979. “Gas Chromatographic-Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Neutral Lipids from Methanogenic and Thermoacidophilic Bacteria.” Journal of Chromatography A 186(C):795–809. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, Yosuke, and Laura Villanueva. 2023. “Four Billion Years of Microbial Terpenome Evolution.” FEMS Microbiology Reviews 47(2). [CrossRef]

- Isobe, Keisuke, Takuya Ogawa, Kana Hirose, Takeru Yokoi, Tohru Yoshimura, and Hisashi Hemmi. 2014. “Geranylgeranyl Reductase and Ferredoxin from Methanosarcina Acetivorans Are Required for the Synthesis of Fully Reduced Archaeal Membrane Lipid in Escherichia Coli Cells.” Journal of Bacteriology 196(2):417–23. [CrossRef]

- Jain, Samta, Antonella Caforio, and Arnold J. M. Driessen. 2014. “Biosynthesis of Archaeal Membrane Ether Lipids.” Frontiers in Microbiology 5:641. [CrossRef]

- Jain, Samta, Antonella Caforio, Peter Fodran, Juke S. Lolkema, Adriaan J. Minnaard, and Arnold J. M. Driessen. 2014. “Identification of CDP-Archaeol Synthase, a Missing Link of Ether Lipid Biosynthesis in Archaea.” Chemistry & Biology 21(10):1392–1401. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Sara Munk, Vinnie Lund Neesgaard, Sandra Landbo Nedergaard Skjoldbjerg, Martin Brandl, Christer S. Ejsing, and Alexander H. Treusch. 2015. “The Effects of Temperature and Growth Phase on the Lipidomes of Sulfolobus Islandicus and Sulfolobus Tokodaii.” Life 5(3):1539–66. [CrossRef]

- Jumper, John, Richard Evans, Alexander Pritzel, Tim Green, Michael Figurnov, Olaf Ronneberger, Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool, Russ Bates, Augustin Žídek, Anna Potapenko, Alex Bridgland, Clemens Meyer, Simon A. A. Kohl, Andrew J. Ballard, Andrew Cowie, Bernardino Romera-Paredes, Stanislav Nikolov, Rishub Jain, Jonas Adler, Trevor Back, Stig Petersen, David Reiman, Ellen Clancy, Michal Zielinski, Martin Steinegger, Michalina Pacholska, Tamas Berghammer, Sebastian Bodenstein, David Silver, Oriol Vinyals, Andrew W. Senior, Koray Kavukcuoglu, Pushmeet Kohli, and Demis Hassabis. 2021. “Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold.” Nature 596(7873):583–89. [CrossRef]

- Kejžar, Jan, Ilja Gasan Osojnik Črnivec, and Nataša Poklar Ulrih. 2022. “Advances in Physicochemical and Biochemical Characterization of Archaeosomes from Polar Lipids of Aeropyrum Pernix K1 and Stability in Biological Systems.” ACS Omega. [CrossRef]

- Kellermann, Matthias Y., Marcos Y. Yoshinaga, Raymond C. Valentine, Lars Wörmer, and David L. Valentine. 2016. “Important Roles for Membrane Lipids in Haloarchaeal Bioenergetics.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Biomembranes 1858(11):2940–56. [CrossRef]

- Koga, Y., T. Kyuragi, M. Nishihara, and N. Sone. 1998. “Did Archaeal and Bacterial Cells Arise Independently from Noncellular Precursors? A Hypothesis Stating That the Advent of Membrane Phospholipid with Enantiomeric Glycerophosphate Backbones Caused the Separation of the Two Lines of Descent.” Journal of Molecular Evolution 46(1):54–63. [CrossRef]

- Koga, Y, H. Morii., M. Akagawa-Matsushita, and Mami Ohga. 1998. “Correlation of Polar Lipid Composition with 16S RRNA Phylogeny in Methanogens. Further Analysis of Lipid Component Parts.” Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry 4(1):88–100.

- Koga, Yosuke. 2012. “Thermal Adaptation of the Archaeal and Bacterial Lipid Membranes.” Archaea 2012. [CrossRef]

- Koga, Yosuke, and Hiroyuki Morii. 2005. “Recent Advances in Structural Research on Ether Lipids from Archaea Including Comparative and Physiological Aspects.” Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry 69(11):2019–34. [CrossRef]

- de Kok, Niels A. W., Marten Exterkate, Ruben L. H. Andringa, Adriaan J. Minnaard, and Arnold J. M. Driessen. 2021. “A Versatile Method to Separate Complex Lipid Mixtures Using 1-Butanol as Eluent in a Reverse-Phase UHPLC-ESI-MS System.” Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 240:105125. [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, Hiroaki, and Parkson Lee Gau Chong. 1998. “Low Permeability of Liposomal Membranes Composed of Bipolar Tetraether Lipids from Thermoacidophilic Archaebacterium Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius.” Biochemistry 37(1):107–15. [CrossRef]

- Kropp, Cosimo, Julius Lipp, Anna Lena Schmidt, Christina Seisenberger, Mona Linde, Kai-Uwe Hinrichs, and Patrick Babinger. 2022. “Identification of Acetylated Diether Lipids in Halophilic Archaea.” MicrobiologyOpen 11(3):e1299. [CrossRef]

- Kull, Daniel R., and Hanspeter Pfander. 1997. “Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Carotenoid Glycosides from the Thermoacidophilic Archaea Sulfolobus Shibatae.” Journal of Natural Products 60(4):371–74. [CrossRef]

- Kung, Yan, Ryan P. McAndrew, Xinkai Xie, Charlie C. Liu, Jose H. Pereira, Paul D. Adams, and Jay D. Keasling. 2014. “Constructing Tailored Isoprenoid Products by Structure-Guided Modification of Geranylgeranyl Reductase.” Structure 22(7):1028–36.

- Lai, Denton, James R. Springstead, and Harold G. Monbouquette. 2008. “Effect of Growth Temperature on Ether Lipid Biochemistry in Archaeoglobus Fulgidus.” Extremophiles 12(2):271–78. [CrossRef]

- Łapińska, Urszula, Georgina Glover, Zehra Kahveci, Nicholas A. T. Irwin, David S. Milner, Maxime Tourte, Sonja Verena Albers, Alyson E. Santoro, Thomas A. Richards, and Stefano Pagliara. 2023. “Systematic Comparison of Unilamellar Vesicles Reveals That Archaeal Core Lipid Membranes Are More Permeable than Bacterial Membranes.” PLoS Biology 21(4):e3002048. [CrossRef]

- Lattuati, Agnès, Jean Guezennec, Pierre Metzger, and Claude Largeau. 1998. “Lipids of Thermococcus Hydrothermalis, an Archaea Isolated from a Deep- Sea Hydrothermal Vent.” Lipids 33(3):319–26.

- Lesk, Arthur M. 1995. “NAD-Binding Domains of Dehydrogenases.” Current Opinion in Structural Biology 5(6):775–83.

- Letunic, Ivica, and Peer Bork. 2021. “Interactive Tree of Life (ITOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation.” Nucleic Acids Research 49(W1):W293–96. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Li Jun, Zhen Jiang, Pei Wang, Ya Ling Qin, Wen Xu, Yang Wang, Shuang Jiang Liu, and Cheng Ying Jiang. 2021. “Physiology, Taxonomy, and Sulfur Metabolism of the Sulfolobales, an Order of Thermoacidophilic Archaea.” Frontiers in Microbiology 12:3096. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, Cody T., David F. Iwig, Bo Wang, Matteo Cossu, William W. Metcalf, Amie K. Boal, and Squire J. Booker. 2022. “Discovery, Structure and Mechanism of a Tetraether Lipid Synthase.” Nature 609(7925):197–203. [CrossRef]

- Lobasso, Simona, Patrizia Lopalco, Veronica M. T. Lattanzio, and Angela Corcelli. 2003. “Osmotic Shock Induces the Presence of Glycocardiolipin in the Purple Membrane of Halobacterium Salinarum.” Journal of Lipid Research 44(11):2120–26. [CrossRef]

- Lopalco, Patrizia, Simona Lobasso, Francesco Babudri, and Angela Corcelli. 2004. “Osmotic Shock Stimulates de Novo Synthesis of Two Cardiolipins in an Extreme Halophilic Archaeon.” Journal of Lipid Research 45(1):194–201. [CrossRef]

- Makarova, Kira S., Yuri I. Wolf, and Eugene V. Koonin. 2015. “Archaeal Clusters of Orthologous Genes (ArCOGs): An Update and Application for Analysis of Shared Features between Thermococcales, Methanococcales, and Methanobacteriales.” Life 5(1):818–40.

- Matsuno, Yasuhiko, Akihiko Sugai, Hiroki Higashibata, Wakao Fukuda, Katsuaki Ueda, Ikuko Uda, Itaru Sato, Toshihiro Itoh, Tadayuki Imanaka, and Shinsuke Fujiwara. 2009. “Effect of Growth Temperature and Growth Phase on the Lipid Composition of the Archaeal Membrane from Thermococcus Kodakaraensis.” Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry 73(1):104–8. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, Corey W., Florence Mingardon, Brett M. Garabedian, Edward E. K. Baidoo, Veronica T. Benites, Andria V. Rodrigues, Raya Abourjeily, Angelique Chanal, and Taek Soon Lee. 2018. “Discovery of Novel Geranylgeranyl Reductases and Characterization of Their Substrate Promiscuity 06 Biological Sciences 0605 Microbiology 06 Biological Sciences 0601 Biochemistry and Cell Biology.” Biotechnology for Biofuels 11(1):340.

- Mencía, Mario. 2020. “The Archaeal-Bacterial Lipid Divide, Could a Distinct Lateral Proton Route Hold the Answer?” Biology Direct 15(1):7.

- Mori, Takeshi, Keisuke Isobe, Takuya Ogawa, Tohru Yoshimura, and Hisashi Hemmi. 2015. “A Phytoene Desaturase Homolog Gene from the Methanogenic Archaeon Methanosarcina Acetivorans Is Responsible for Hydroxyarchaeol Biosynthesis.” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 466(2):186–91. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Motomichi, Kyohei Shibuya, Toru Nakayama, Tokuzo Nishino, Tohru Yoshimura, and Hisashi Hemmi. 2007a. “Geranylgeranyl Reductase Involved in the Biosynthesis of Archaeal Membrane Lipids in the Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Archaeoglobus Fulgidus.” FEBS Journal 274(3):805–14. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Motomichi, Kyohei Shibuya, Toru Nakayama, Tokuzo Nishino, Tohru Yoshimura, and Hisashi Hemmi. 2007b. “Geranylgeranyl Reductase Involved in the Biosynthesis of Archaeal Membrane Lipids in the Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Archaeoglobus Fulgidus.” FEBS Journal 274(3):805–14. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Motomichi, Kyohei Shibuya, Toru Nakayama, Tokuzo Nishino, Tohru Yoshimura, and Hisashi Hemmi. 2007c. “Geranylgeranyl Reductase Involved in the Biosynthesis of Archaeal Membrane Lipids in the Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Archaeoglobus Fulgidus.” FEBS Journal 274(3):805–14. [CrossRef]

- Naparstek, Shai, Ziqiang Guan, and Jerry Eichler. 2012. “A Predicted Geranylgeranyl Reductase Reduces the ω-Position Isoprene of Dolichol Phosphate in the Halophilic Archaeon, Haloferax Volcanii.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1821(6):923–33.

- Nichols, David S., Matthew R. Miller, Noel W. Davies, Amber Goodchild, Mark Raftery, and Ricardo Cavicchioli. 2004. “Cold Adaptation in the Antarctic Archaeon Methanococcoides Burtonii Involves Membrane Lipid Unsaturation.” Journal of Bacteriology 186(24):8508–15. [CrossRef]