Submitted:

18 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

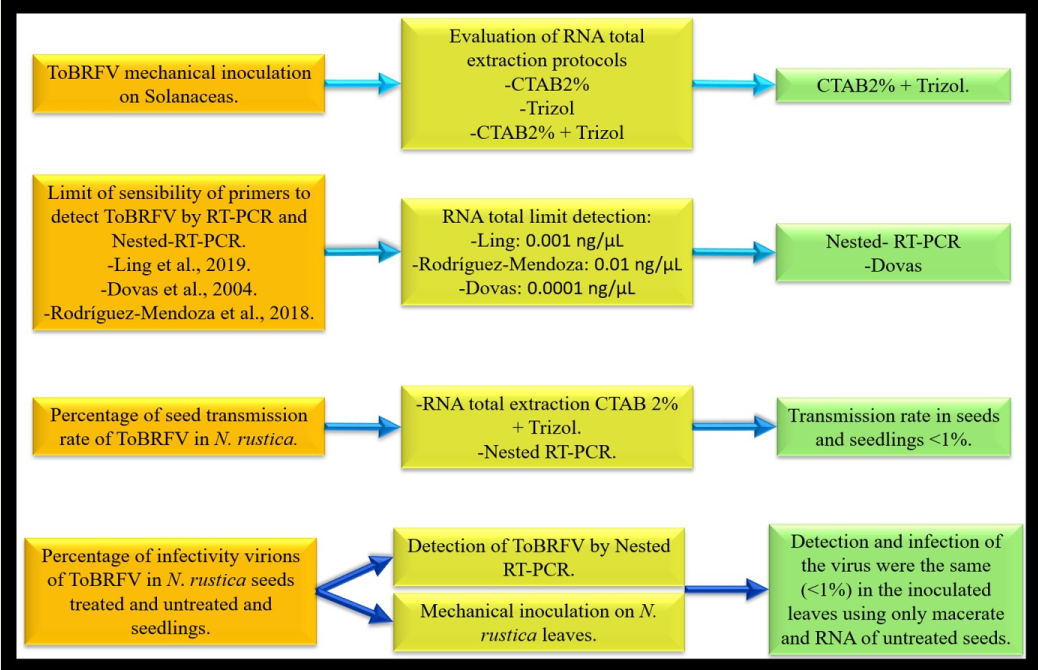

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials Used as an Inoculum Source

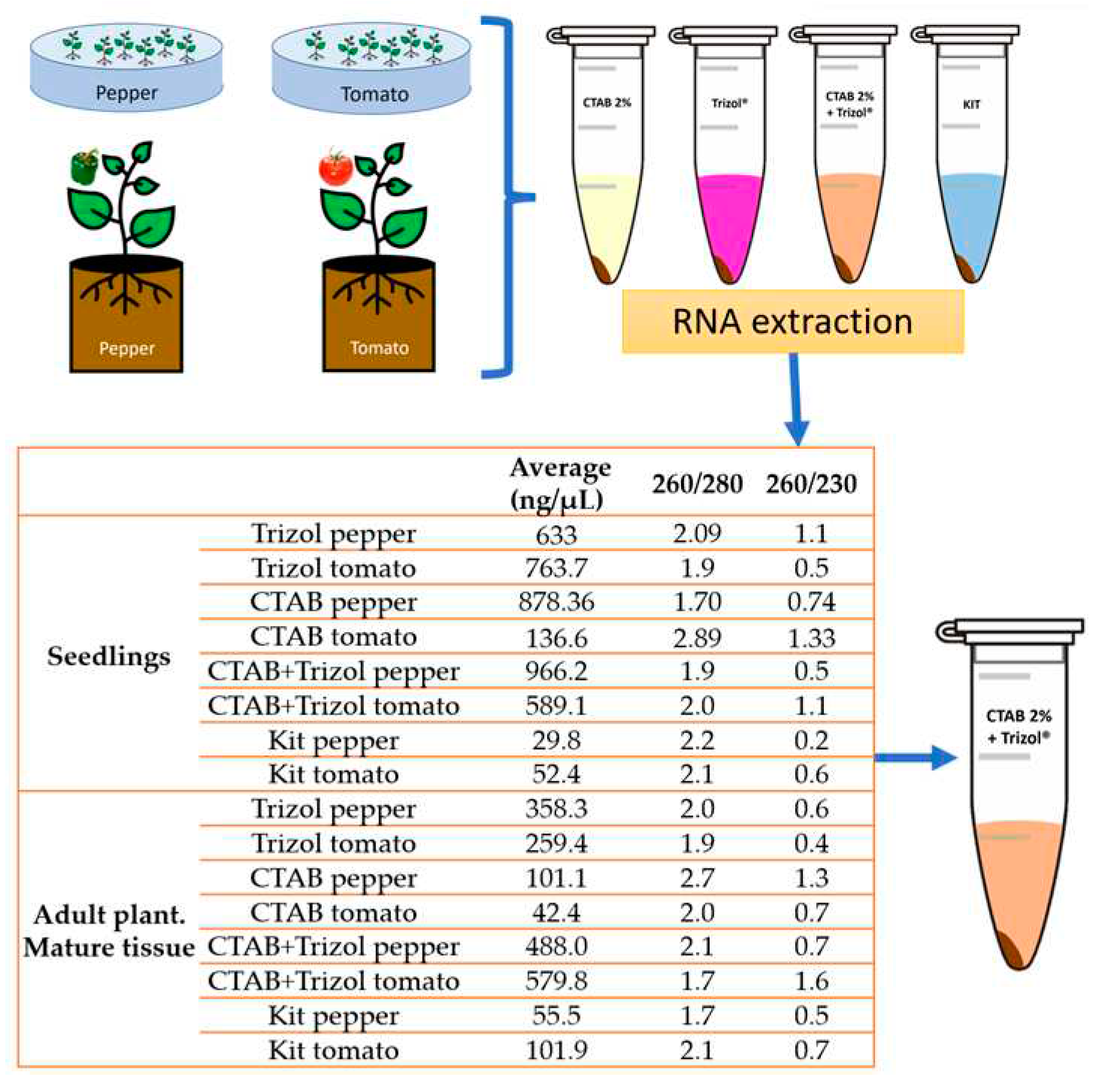

2.2. RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

2.3. Evaluation of Total RNA Extraction Methods

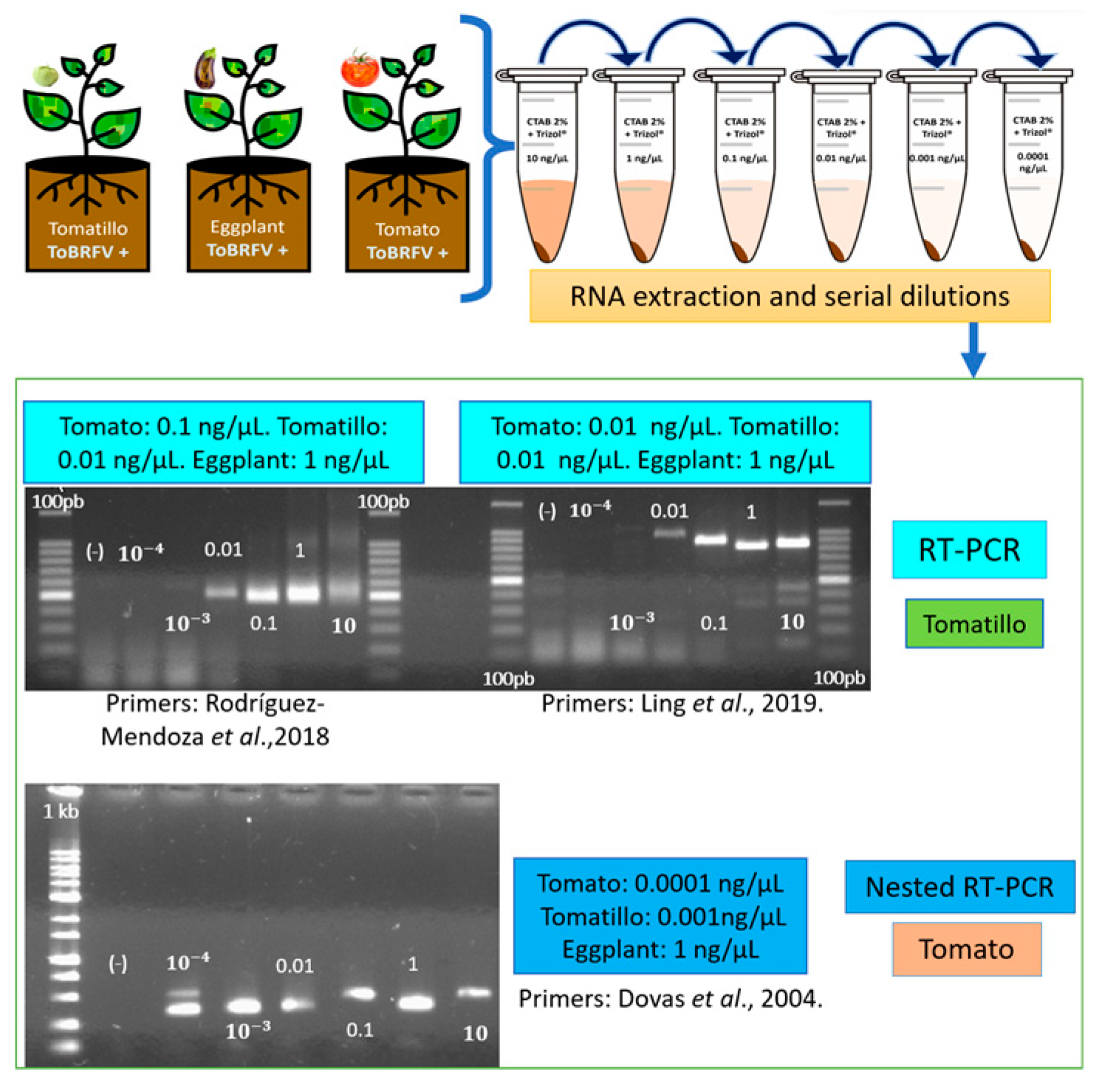

2.4. Primer Evaluation and Sensitivity Limit

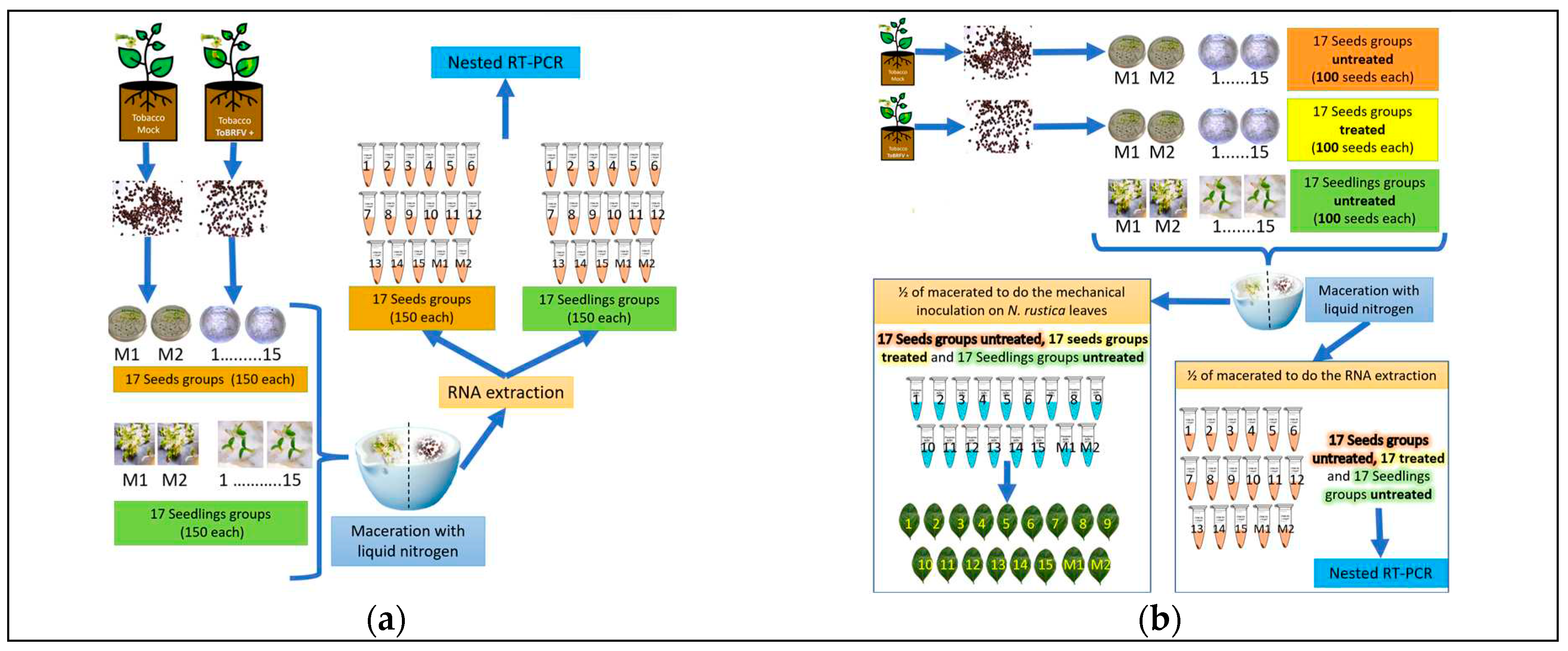

2.5. Seed Transmission Test

2.5.1. Acquisition of Seeds

2.5.2. Germination Test

2.5.3. Estimation of Percentage of Infection in Seeds or Seedlings

2.5.4. Experimental Method to Determine the Percentage of Infected Seeds

2.5.5. Infectivity Tests of Viral Particles in Seeds

2.6. Bioassays of Potential Hosts

3. Results

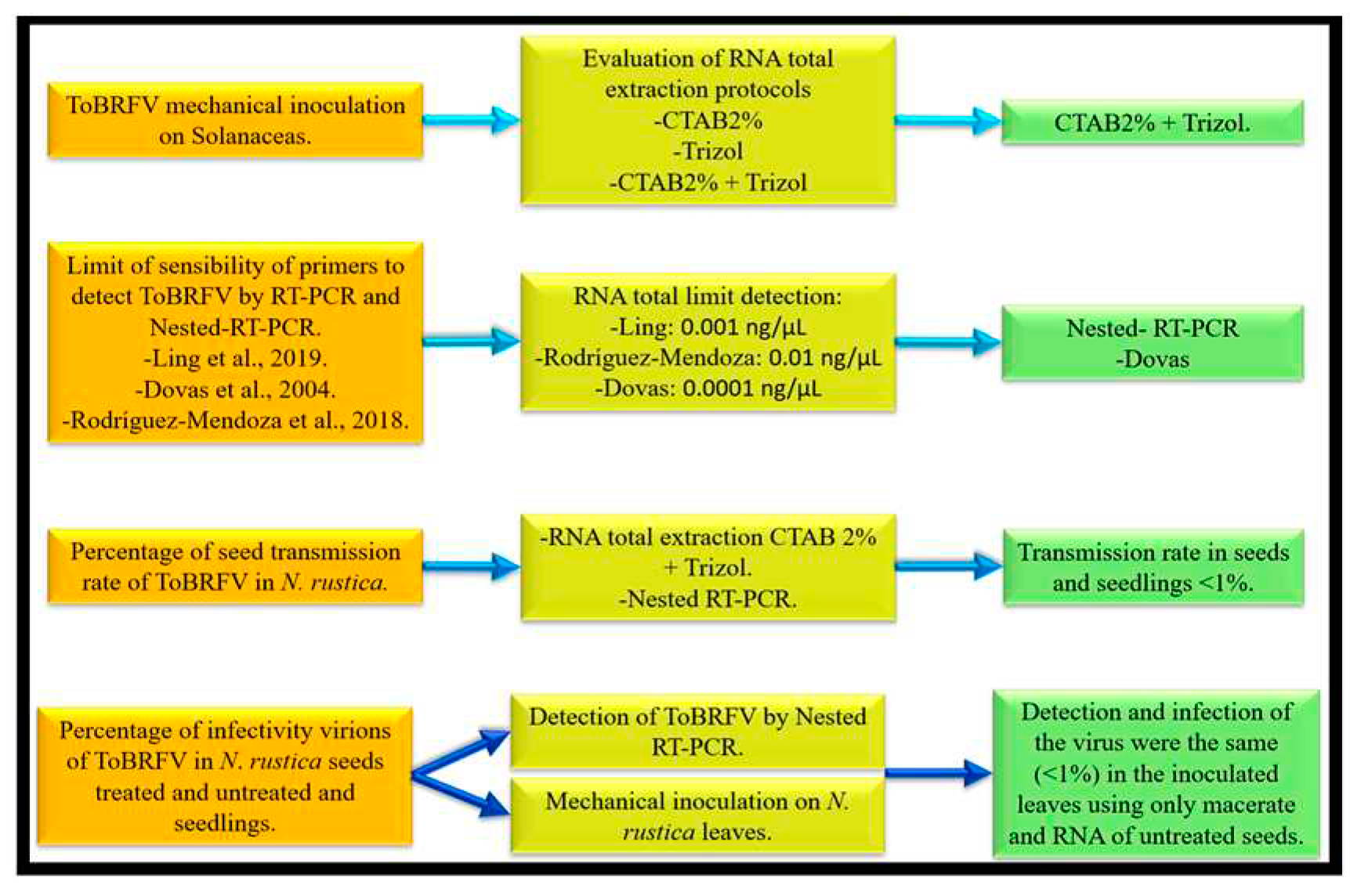

3.1. Evaluation of Total RNA Extraction Methods

3.2. Primer Evaluation and Sensitivity Limit

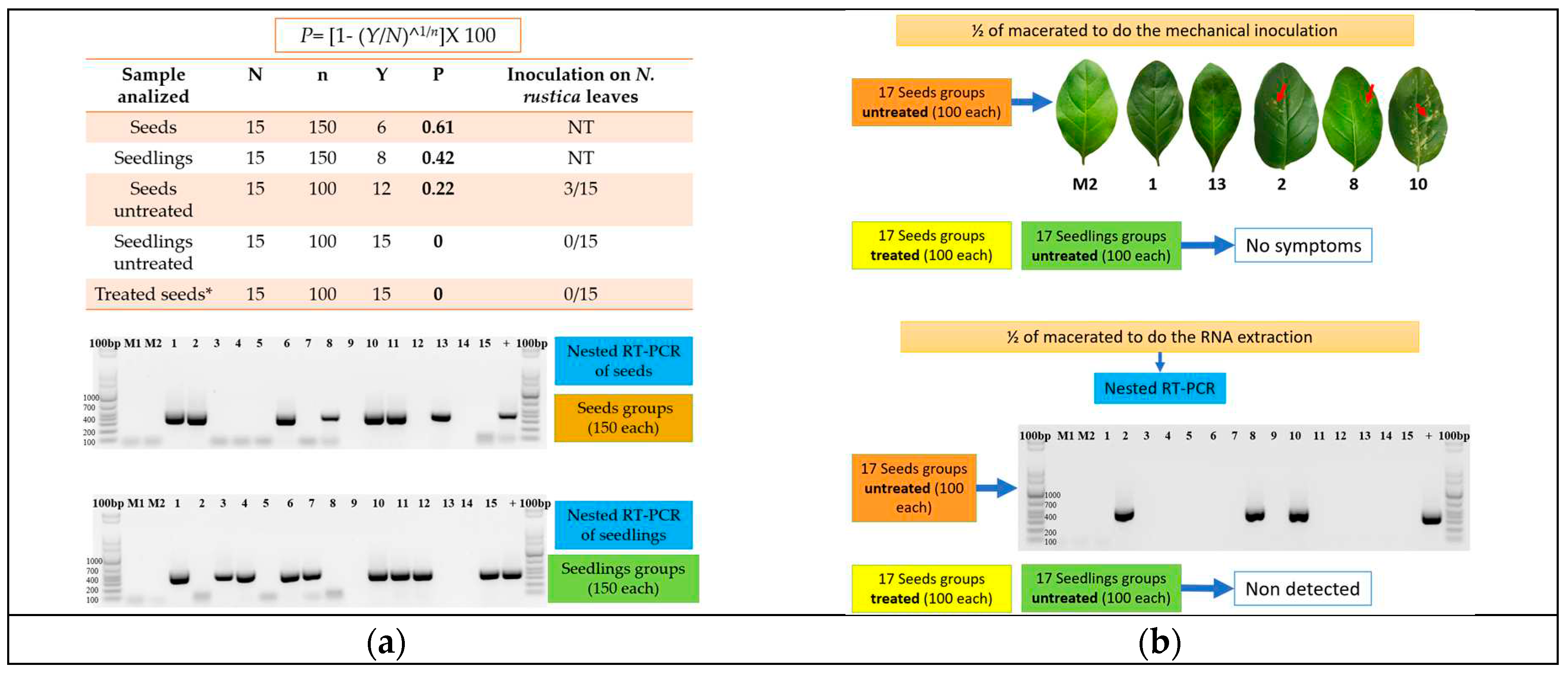

3.3. Seed Transmission

3.3.1. Collection of Seeds and Germination Test

3.3.2. Percentage of Infection in Seeds and Seedlings

3.3.3. Infectivity Tests of Viral Particles in Seeds

3.4. Biological Assays to Test Potential Hosts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (A)

-

Trizol protocol:

- Macerate 100 mg of plant tissue with liquid nitrogen and add it immediately to an Eppendorf tube with 1 mL of cold Trizol. Give a pulse of the vortex and leave them for 5 minutes on ice.

- Add 400 ml of chloroform and mix by inversion 7 times. Leave the tube on ice for 10 minutes.

- Centrifuge by 10 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4°C.

- Recover carefully the supernatant (approx. 400 µL) and transfer it to a clean Eppendorf tube.

- Add 1.5 V of cold isoamyl alcohol and leave the tube at -20°C for 20 minutes.

- Centrifuge by 15 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4°C.

- Discard the alcohol taking care of the pellet at the bottom of the tube.

- Wash the pellet with 1 mL of cold ethanol at 90% and centrifuge again for 5 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4°C.

- Discard all the ethanol, take care of the pellet, and let it dry at room temperature.

- Resuspend and dissolve the pellet in 30 to 50 µL of RNAsa-free distilled water.

- (B)

-

CTAB 2% protocol:

- Macerate 100 mg of plant tissue with liquid nitrogen and add it immediately on an Eppendorf tube with 700 mL of CTAB 2% + PVP (1%) + BME (0.2%). Give a pulse with a vortex.

- Incube at 55°C in a water bath for 10 minutes.

- Add 470 ml of cold chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (24:1) and mix by inversion 7 times.

- Centrifuge by 10 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4°C.

- Recover carefully the supernatant (approx. 400 µL) and transfer it to a new Eppendorf tube.

- Add 1 V of cold isoamyl alcohol and 1/10 V of sodium acetate (3M) and mix by inversion. Left the tube at -20°C for 20 minutes.

- Centrifuge by 15 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4°C.

- Discard the liquid taking care of the pellet at the bottom of the tube.

- Wash the pellet with 1 mL of cold ethanol at 90% and centrifuge again for 5 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4°C.

- Discard all the ethanol, take care of the pellet, and let it dry at room temperature.

- Resuspend and dissolve the pellet in 50 to 100 µL of RNAsa-free distilled water.

- (C)

-

CTAB2% + Trizol

- Follow steps 1 to 5 of section (B) of Appendix 1.

- Add 500 µL of Trizol and mix by inversion 7 times.

- Follow steps 2 to 10 of section (A) of Appendix 1.

References

- Dovas, C.I.; Efthimiou, K., Katis, N.I. Generic detection and differentiation of tobamoviruses by a spot nested RT-PCR-RFLP using dI-containing primers along with homologous dG-containing primers. Journal of Virological Methods 2004, 117, 137–144. [CrossRef]

- Luria, N.; Smith, E.; Reingold, V.; Bekelman, I.; Lapidot, M.; Levin, I.; Elad, N.; Tam, Y.; Sela N.; Abu-Ras, A.: Ezra, N.; Haberman, A.; Yitzhak L.; Lachman, O.; Dombrovsky, A. A New Israeli Tobamovirus Isolate Infects Tomato Plants Harboring Tm-22 Resistance Genes. PloS One 2017, 12(1), e0170429. PMID: 28107419. [CrossRef]

- Levitzky, N.; Smith, E.; Lachman, O.; Luria, N.; Mizrahi, Y.; Bakelman, H.; Sela, N.; Laskar, O.; Milrot, E.; Dombrovsky, A. The bumblebee Bombus terrestris carries a primary inoculum of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus contributing to disease spread in tomatoes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(1), e0210871. [CrossRef]

- Panno, S.; Caruso, G.A.; Stefano, B.; Lo Bosco Giosuè, E. R.A.; Salvatore, D. Spread of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus in Sicily and Evaluation of the Spatiotemporal Dispersion in Experimental Conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 834. [CrossRef]

- Dombrovsky, A., Smith, E., 2017. Seed Transmission of Tobamoviruses: Aspects of Global Disease Distribution. In: Advances in seed biology, Jimenez-Lopez, J.C., Ed. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.G., 2014. Plant Viruses: Soil-borne. In: eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester. 12 p. [CrossRef]

- Davino, S.; Caruso, A.G.; Bertacca, S.; Barone, S.; Panno, S.. Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Seed Transmission Rate and Efficacy of Different Seed Disinfection Treatments. Plants 2020. 9, 1615. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Vásquez, J.A.; Córdoba-Sellés, M.C.; Cebrián, M.C.; Alfaro-Fernandez, A.; Jordá, C. Seed transmission of Melon necrotic spot virus and efficacy of seed-disinfection treatments. Plant Pathology 2009. 58, 7. [CrossRef]

- Rast, A. Th. B.; Stijger, C.C.M.M. Disinfection of pepper seed infected with different strains of capsicum mosaic virus by trisodium phosphate and dry heat treatment. Plant Pathology 1987, 36 (4), 583-588. [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.S. Occurrence of two tobamovirus diseases in cucurbits and control measures in Korea. Plant Pathology Journal 2001. 17, 243–248. https://www.ppjonline.org/upload/pdf/PPJ021-03-09.pdf.

- Li, J.X.; Liu, S.S.; Gu, Q.S. Transmission efficiency of Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus via seeds, soil, pruning and irrigation water. Journal of Phytopathology 2015, 164(5), 300-309. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Udaya, S.A.; Nayaka, S.; Lund, O.; Prakash, H. Detection of Tobacco mosaic virus and Tomato mosaic virus in pepper and tomato by multiplex RT–PCR. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2011, 53(3), 359-363. [CrossRef]

- International Seed Federation (ISF), 2019. https://www.worldseed.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Tomato-ToBRFV_2019.09.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- SENASICA (Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria). 2019. Dirección general de sanidad vegetal- Centro nacional de referencia fitosanitaria, Protocolo de Diagnóstico: Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV). Versión 2.0. http://sinavef.senasica.gob.mx/CNRF/AreaDiagnostico/DocumentosReferencia/Documentos/ProtocolosFichas/Protocolos/VirusFitopatogenos/PD%20ToBRFV%20V.2%20PUB.pdf (accesed on 15 August 2021).

- Rodríguez-Mendoza, J.; García-Ávila, C.J.; López-Buenfil, J.A.; Araujo-Ruiz, K.; Quezada-Salinas, A.; Cambrón-Crisantos, J.M. Identification of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus by RT-PCR from a coding region of replicase (RdRP). Mexican Journal of Phytopathology 2018, 37(2), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Jordon-Thaden, I.E.; Chanderbali, A.S.; Gitzendanner, M.A.; Soltis D.E. Protocol note. Modified CTAB and Trizol protocols improve RNA extraction from chemically complex embryophyta. Applications in Plant Sciences 2015, 3(5), 1400105. [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.S.; Tian, T.; Gurung, S.; Salati, R.; Gilliard, A. First report of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus infecting greenhouse tomato in the United States. Plant Disease 2019, 103, 1439. [CrossRef]

- Albrechtsen, S.E. Testing methods for seed transmitted viruses: principles and protocols. Publisher: CABI, Wallingford, 2006. 268 p.

- Salem, N.M.; Sulaiman, A.; Samarah, N.; Turina, M.; Vallino, M. Localization and mechanical transmission of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus in tomato seeds. Plant Disease 2021, 106, 275-281. [CrossRef]

- Samarah, N.; Sulaiman, A.; Salem, N.M.; Turina, M. Disinfection treatments eliminated tomato brown rugose fruit virus in tomato seeds. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2021, 159, 153–162. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, B.; Shamimuzzaman, M.D.; Gilliard, A.; Ling, K.S. Effectiveness of disinfectants against the spread of tobamoviruses: Tomato brown rugose fruit virus and Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus. Virology Journal 2021. 18, 7. [CrossRef]

- Marodin, J.C.; Resende, F.V.; Gabriel, A.; Souza, R.J.De; Resende, J.T.V. De; Camargo, C.K.; Zeist, A.R. Agronomic performance of both virus-infected and virus free garlic with different seed bulbs and clove sizes. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira 2019, 54, e01448. [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, K.; McLean, D. L. Gamete-Seed Transmission of Alfalfa Mosaic Virus and Its Effect on Seed Germination and Yield in Alfalfa Plants. Disease Detection and Losses. AMV in alfalfa seed. Phytopathology 1977, 67, 576-579. https://www.apsnet.org/publications/phytopathology/backissues/Documents/1977Articles/Phyto67n05_576.pdf.

- Mohan, B.G., Baruah, G., Sen, P., Deb, N.P., Kumar, B.B. Host-Parasite Interaction During Development of Major Seed-Transmitted Viral Diseases. In: Seed-Borne Diseases of Agricultural Crops: Detection, Diagnosis & Management; Kumar, R.A., Gupta, Eds., Springer, 2020; pp.265-289. [CrossRef]

- Froissart, R.; Doumayrou, J.; Vuillaume, F.; Alizon, S.; Michalakis, Y. The virulence –transmission trade-off in vector-borne plant viruses: a review of (non-)existing studies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2010, 365, 1907–1918. [CrossRef]

- Lipsitch, M.; Nowak, M.A.; Ebert, D.; May, R.M. The population dynamics of vertically and horizontally transmitted parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological 1995, 260, 321–327. [CrossRef]

- Cobos, A.; Montes, N.; López-Herranz, M.; Gil-Valle, M.; Pagán, I. Within-Host Multiplication and Speed of Colonization as Infection Traits Associated with Plant Virus Vertical Transmission. Journal of virology 2019, 93(23), e01078-19. [CrossRef]

- Montes, N.; Pagán, I. Light Intensity Modulates the Efficiency of Virus Seed Transmission through Modifications of Plant Tolerance. Plants 2019, 8 (304), 15p. [CrossRef]

- Fidan, H.; Pelin, S.; Kubra, Y.; Bengi, T.; Gozde, E.; Ozer, C. Robust molecular detection of the new Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in infected tomato and pepper plant from Turkey. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2020, 19, 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.; Yin, W.C.; Wang, C.K.; To, K.Y. Isolation of functional RNA from different tissues of tomato suitable for developmental profiling by microarray analysis. Botanical Studies 2009, 50(2), 115-125. https://ejournal.sinica.edu.tw/bbas/content/2009/2/Bot502-01.pdf.

- Dadáková, K.; Heinrichová, T.; Lochman, J.; Kašparovský, T. Production of Defense Phenolics in Tomato Leaves of Different Age. Molecules 2020, 25(21), 4952. [CrossRef]

- Salzman, R.A.; Fujita, T.; Zhu-Salzman, K.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Bressan, R.A. An improved RNA isolation method for plant tissues containing high levels of phenolic compounds or carbohydrates. Plant Molecular Biology Report 1999, 17, 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Gambino, G.; Perrone, I.; Gribaudo, I. A Rapid and effective method for RNA extraction from different tissues of grapevine and other woody plants. Phytochemical Analysis 2008, 19(6), 520-5. [CrossRef]

- Toni, L.S.; Garcia, A.M.; Jeffrey, D.A.; Jiang, X.; Stauffer, B.L.; Miyamoto, S.D.; Sucharov, C.C. Optimization of phenol-chloroform RNA extraction. MethodsX 2018, 5, 599-608. [CrossRef]

- Mathioudakis, Μ.Μ.; Saponari, M.; Hasiów-Jaroszewska B.; Elbeaino, T.; Koubouris, G. Detection of viruses in olive cultivars in Greece, using a rapid and effective RNA extraction method, for certification of virus-tested propagation material. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 2020, 59(1), 203-211. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Puryear, J.; Cairney, J. A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 1993, 11, 113–116. [CrossRef]

- Magaña-Álvarez, A.A.; Pérez-Brito, D.; Vargas-Hernández, B.Y.; Ramírez-Pool, J.A.; Núñez-Muñoz, L.A.; Salgado-Ortiz, H.; de la Torre-Almaraz R.; Ruiz- Medrano R.; Xoconostle-Cázares, B. Detection of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) in solanaceous plants in Mexico. Journal of Plant Disease Protection 2021, 128, 1627–1635. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Cho, K.; Cho, H.; Kang, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, N. Comparison of one-step RT-PCR and a nested PCR for the detection of canine distemper virus in clinical samples. Australian Veterinary Journal 2004, 82(1-2), 83–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.2004.tb14651.x.

- Panno, S.; Ruiz-Ruiz, S.; Caruso, A.G.; Alfaro-Fernandez, A.; San Ambrosio, M.I.; Davino, S. Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction development for rapid detection of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus and comparison with other techniques. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7928. [CrossRef]

- Oladokun, J.; Halabi, M.; Barua, P.; Nath, P.J.P.P. Tomato brown rugose fruit disease: current distribution, knowledge and future prospects. Plant Pathology 2019, 68, 1579-1586. [CrossRef]

- European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO). 2019. Reporting Service 2019/192. https://gd.eppo.int/reporting/article-6622 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Fajinmi, A. A.; Fajinmi, O. B. Incidence of Okra mosaic virus at different growth stages of okra plants (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench) under tropical condition. Journal of General and Molecular Virology 2010, 2, 28-3.

- Chellappan, P.; Vanitharani, R.; Ogbe, F.; Fauquet, C.M. Effect of temperature on geminivirus-induced RNA Silencing in Plants. Plant Physiology 2005, 138, 1828–1841. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Singh, J.; Li, D.; Qua, F. Temperature- dependent survival of Turnip crinkle virus-infected Arabidopsis plants relies on an RNA silencing-based defense that requires DCL2, AGO2, and HEN1. Journal of Virolgy, 2012, 12, 6847–6854. [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.N.; Kyung, S.C.; Jeong, J.A.; Jae, H.J.; Ki, S.D.; Kyo-Sun, P. Effects of Temperature on Systemic Infection and Symptom Expression of Turnip mosaic virus in Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris). Journal of Plant Pathology 2015, 31(4), 363-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.NT.06.2015.0107.

- Szittya, G.; Silhavy, D.; Molnár, A.; Havelda, Z.; Lovas, A.; Lakatos, L.; Bánfalvi, Z.; Burgyán, J. Low temperature inhibits RNA silencing-mediated defense by the control of siRNA generation. EMBO Journal 2003, 22, 633–640. [CrossRef]

| Number of Germinated Seeds | ||

|---|---|---|

| Repetition | +ToBRFV | Healthy |

| 1 | 58 | 92 |

| 2 | 56 | 87 |

| 3 | 64 | 88 |

| 4 | 56 | 75 |

| 5 | 74 | 88 |

| 6 | 52 | 82 |

| 7 | 46 | 44 |

| 8 | 63 | 89 |

| 9 | 51 | 93 |

| Inoculated Specie | Nested RT-PCR | ELISA |

|---|---|---|

| Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) | 0*, 0°, 0" | 0, 0, 0 |

| Cantaloupe (Cucumis melo) | 0, 0, 0 | 0, 0, 0 |

| Squash (Cucurbita pepo) | 0, 0, 0 | 0, 0, 0 |

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) | 0, 0, 0 | 0, 0, 0 |

| Pea (Pisum sativum) | 0, 0, 0 | 0, 0, 0 |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | 5, 5, 5 | 5, 5, 5 |

| Tomatillo (Physalis ixocarpa) | 3, 4, 3 | 3, 4, 3 |

| Tobacco (Nicotiana rustica) | 5, 5, 5 | 5, 5, 5 |

| Pepper (Capsicum annum) | 2, 4, 5 | 2, 4, 5 |

| Eggplant (Solanum melongena) | 0, 1, 5 | 0, 1, 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).