3.1. Problem Descriptions

Consider a market with two competing e-commerce platforms, Platform 1 and Platform 2. Each platform provides services such as trading venues and social interaction for consumers and merchants. Platform 1 offers a lenient and high-quality return service, such as instant refunds. While platform 2 adopts a strict and low-quality return service, where the merchant decides whether to refund or not after testing the returned items. Platform 1’s return service reduces logistics waiting time for consumers, promoting repurchases and creating more trading opportunities for merchants. However, the lack of risk supervision in the return process makes it challenging to ensure the authenticity and integrity of returned items, leading to consumer behaviors such as opportunistic returns, fraudulent returns and incomplete returns. Comparatively, in Platform 2, refunds are less likely to succeed for consumers who exploit the return policy opportunistically, as the returned items are inspected before that. Therefore, it can be assumed that there are no consumers on Platform 2 who abuse the return policy.

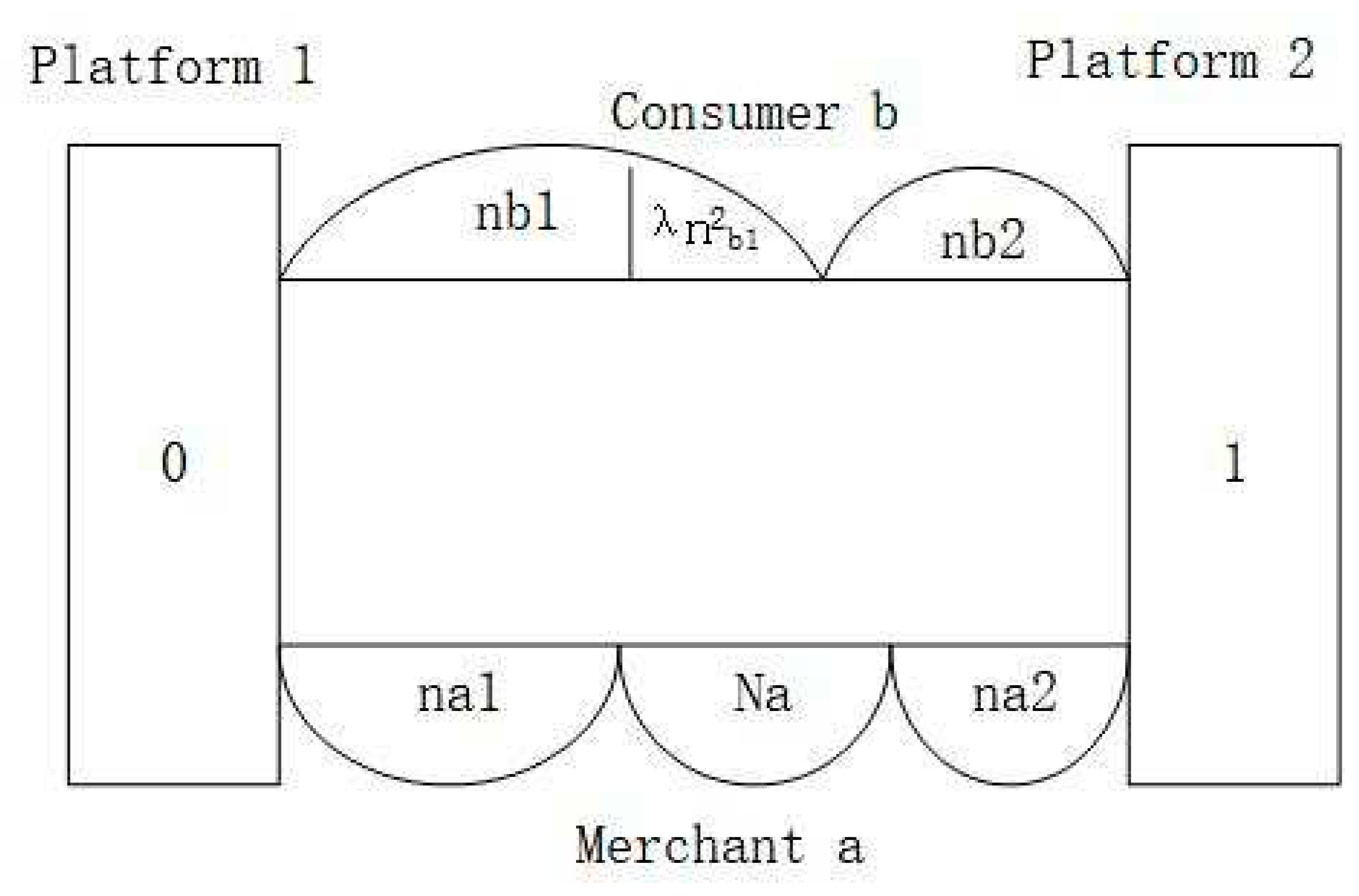

Based on the Hotelling model, it is assumed that Platform 1 and Platform 2 are situated at opposite ends of the linear market [0,1], offering transaction services for merchants and consumer, and charging a certain registration fee [

21]. Assuming that the total market size of merchants (

) and consumers (

) is 1, each follows a uniform distribution on line segment [0,1]. Due to the restriction that consumers (

) can only return items to the platform from which they make their original purchase, for simplicity, in this study, we assume that each consumer is exclusively associated with a single platform. Set the scale of consumers exclusively associated with platform 1 to be

and the scale of consumers exclusively associated with platform 2 to be

.Therefore, we have

, and it is true that

. For merchants, they can choose to join either a single platform or multiple platforms, leading to single- or multi-homing merchants. In this study, we assume that a portion of them are multi-homing merchants. Let

denote the scale of multi-homing merchants,

denote the scale of merchants exclusively affiliated with platform 1, and

denote the scale of merchants exclusively affiliated with platform 2. Thus, we have

, and it holds true that

. Platform 1 charges a registration fee,

, for consumer and a registration fee,

, for merchant. Platform 2 charges a registration fee,

, for consumer and a registration fee,

, for merchant. The model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The services provided by platforms to consumers can be categorized into basic services and after-sales return services, including returns and refunds. Since only Platform 1 offers a flexible return policy, this study assumes that the basic services provided to consumers by Platform 1 and Platform 2 are the same, resulting in the same utility, . This utility is assumed to be high enough for both platforms to cater to the entire consumer market. The level of return service on Platform 1 is denoted by , and the consumer service perception coefficient is denoted by . The utility derived from this service for the consumer is given by . Similarly, it is assumed that both platforms provide the same services to merchants, resulting in the same utility, . It is assumed that this utility is sufficiently high for both platforms to cover the entire merchant market. It is also specified that .

Due to the cross-network externalities in e-commerce platforms, where the scale of one user group can affect the utility of the other user group, the coefficient of cross-network externalities caused by merchants on consumers is denoted as

, and the coefficient of cross-network externalities caused by consumers on merchants is denoted as

. Under lenient return policies, consumers are prone to abusive return practices. Therefore, this study assumes that a proportion

of consumers in the market engage in abusive return behavior, such as opportunistic or fraudulent returns, to obtain benefits denoted as

. Without loss of generality, we assume that the losses incurred by merchants due to abusive return policies are represented as

and a negative externality coefficient is

.The cost coefficient of lenient return service on Platform 1 is denoted as

, and the service cost is represented as

[

22]. The penalty imposed on consumers abusing return policies by platform 1 is denoted as

, the penalty cost coefficient is denoted as

, and the incurred penalty cost is denoted as

.

Consumers and merchants each choose to join Platform 1 or Platform 2 based on their individual utilities. Within the consumers, the utilities of honest consumers ,who engage in regular returns and do not abusing return policies, joining Platform 1 and Platform 2 are denoted as and , respectively, with corresponding scales of and , where . The utilities of consumers who abusing return policies joining Platform 1 and Platform 2 are denoted as and , with scales of and , where . The distance of the honest consumer to platform 1 is denoted by , and the distance to platform 2 is denoted by . Similarly, the distance to platform 1 for consumers abusing return policies is denoted by , and the distance to platform 2 is denoted by . For merchants, the utility of being exclusively affiliated with Platform 1 is denoted as , the utility of being exclusively affiliated with Platform 2 is denoted as , and the utility of multi-homing merchants is denoted as . For merchants exclusively affiliated with Platform 1, the distance to Platform 1 is denoted by. And for merchants exclusively affiliated with Platform 2, the distance to Platform 2 is denoted by . The parameters mentioned above satisfy . Since we do not focus on the transportation costs for both merchants and consumers between the two platforms, they are assumed to be 1. The profits obtained by platforms 1 and 2 are denoted as and , respectively.

3.2. Model Construction

Construct utility functions for consumers and merchants, as well as profit functions for both platforms, based on given parameters. For honest consumers in the market, the utility of joining Platform 1 includes the utility of basic platform services, the utility of lenient return services, the utility of network externalities due to the scale of merchants, platform registration fees, and transportation costs. Utility of joining Platform 2 includes utility of basic platform services, utility of network externalities due to the scale of merchants, platform registration fees, and transportation costs. Thus, we have:

For consumers abusing return policies in the market, the utility of joining Platform 1 includes the utility of basic platform services, the utility of lenient return services, the utility of network externalities due to the scale of merchants, the benefits obtained from abusing return policies, platform penalties, registration fees, and transportation costs. Thus, we have:

For merchants in the market, the utility of exclusively affiliated with Platform 1 includes the utility of platform services, the utility of network externalities due to the scale of honest consumers, the losses incurred due to the scale of consumers abusing return policies and negative network externalities, registration fees, and transportation costs. Utilities exclusively affiliated with Platform 2 include the utility of platform services, the utility of network externalities due to the scale of consumers, registration fees, and transportation costs. The utility of multi-homing merchants includes the utility of services from both platforms, the utility of network externalities due to the scale of honest consumers, losses due to the scale of consumers abusing return policies and negative network externalities, registration fees, and transportation costs. Thus, we have:

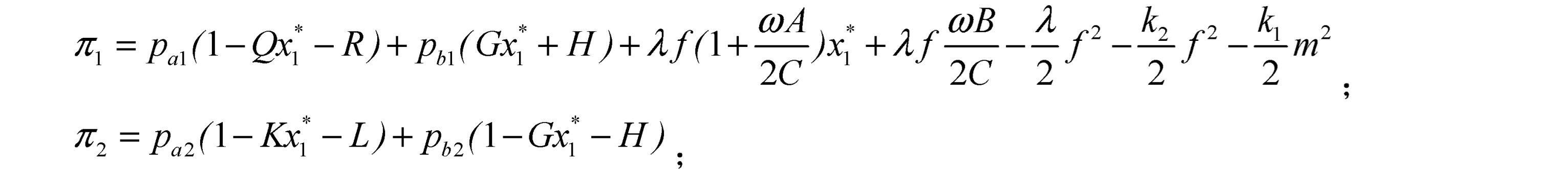

Platform 1's profit includes registration fees received from consumers and merchants, revenue from penalties imposed on consumers who abusing return policies, the cost of those penalties, and the cost of the return service. As for Platform 2, its profit includes registration fees obtained from consumers and merchants. Thus, we have:

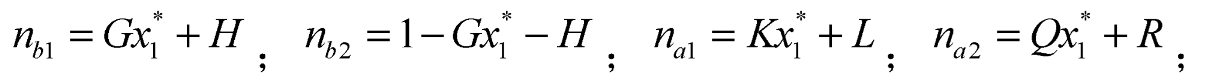

The decision sequence in this paper is as follows. First, each platform independently determines the price for consumers and merchants, i.e., the registration fee charged, where platform 1 also needs to determine the level of return service for consumers. Second, given the price set by Platform 1 and Platform 2, the merchant decides which platform to join for the transaction. Finally, different types of consumers decide to join Platform 1 or Platform 2 for consumption based on their own utility. We adopt the inverse solution method, where the sizes of consumers and merchants in platforms 1 and 2 are first determined and then substituted into the profit functions of the platforms to solve for equilibrium prices that maximizes profit. The specific solving process is as follows:

For honest consumers, the indifference point in terms of utility between the two platforms is determined by the condition

. If

is larger than

, they choose to join Platform 1, and if

is smaller than

, they choose to join Platform 2. The utility indifference point is:

Considering that the scale of honest consumers on Platform 1 is given by

, we can deduce the following:

For consumers abusing return policies, they choose to join Platform 1 when

, and they choose to join Platform 2 when

. Therefore, the indifference point for abusive return consumers in terms of utility between the two platforms is:

Considering that the scale of consumers abusing return policies on Platform 1 is

, we can deduce that:

Given that the proportion of consumers abusing return policies is denoted as

, we can determine the scale of the consumers in Platform 1,

, and the scale of the consumers in Platform 2,

, as follows:

For merchants, when

and

, they choose to be multi-homing. Setting

yields

, and setting

yields

. Taking into account that the scale of exclusively affiliated merchants in Platform 1 is denoted as

, the scale of exclusively affiliated merchants in Platform 2 is denoted as

and the scale of multi-homing merchants is denoted as

, we have:

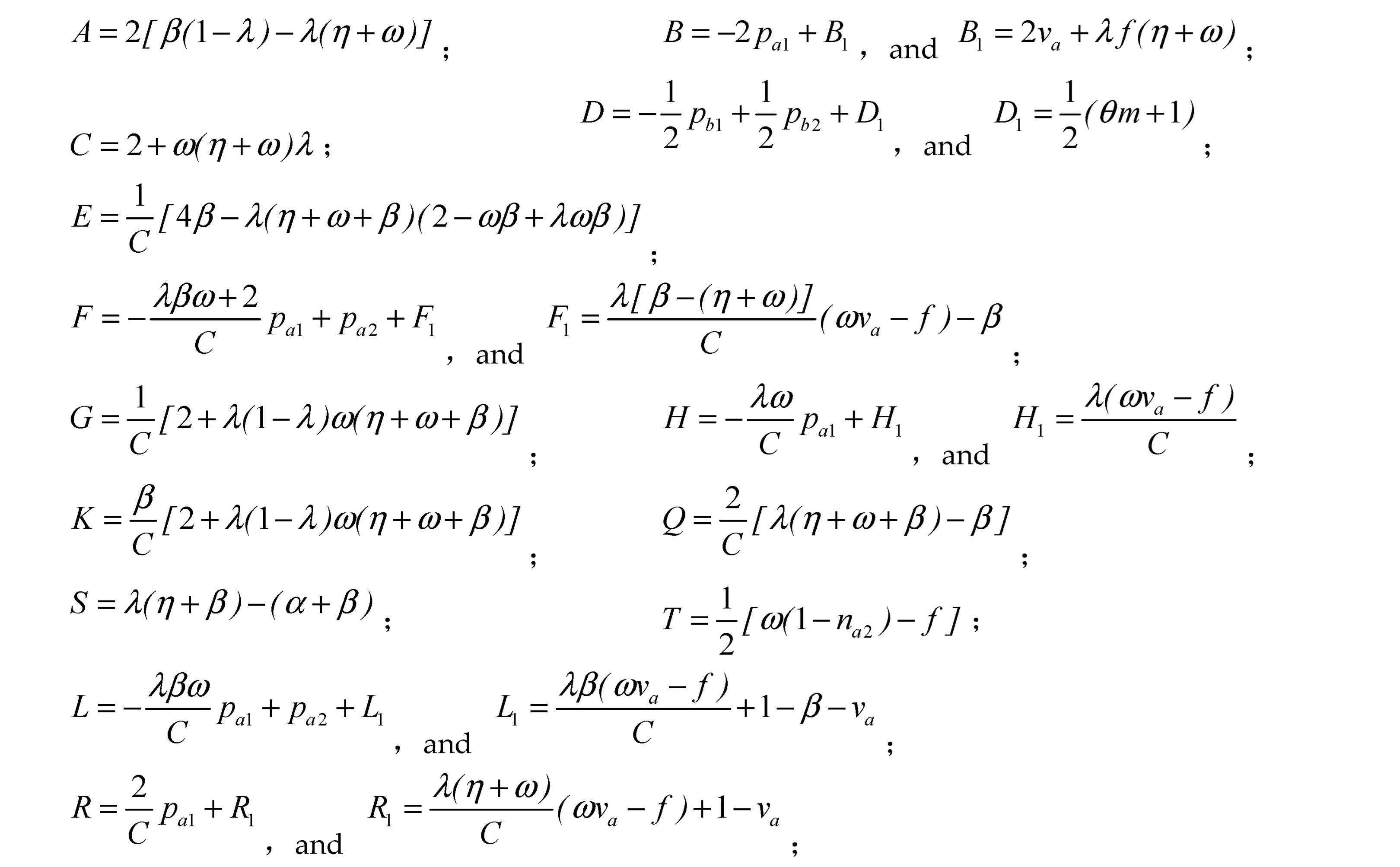

By solving the simultaneous equations for the scale of consumers and merchants in both platforms 1 and 2, and substituting the respective user scale into the profit function of each platform, we obtain the profit functions for platforms 1 and 2 as follows:

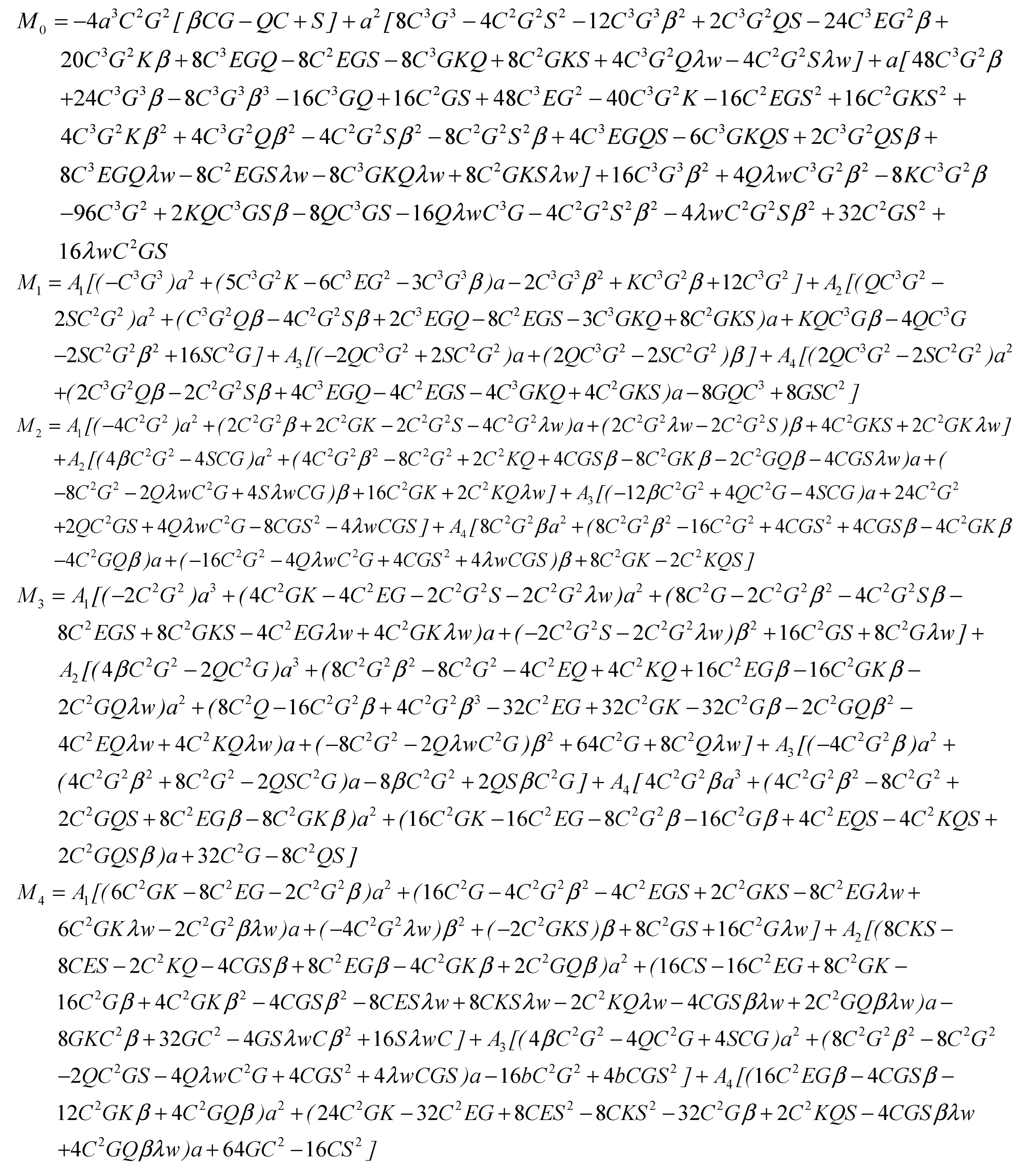

The expression for

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

can be found in the

Appendix A. From the profit function, we obtain the Hessian matrix of Platform 1 with respect to

and

as follows,

When

and

, the Hessian matrix of the profit function indicates that it is negative definite, ensuring that the function has a maximum value. The Hessian matrix of Platform 2 with respect to

and

is as follows,

When and , the matrix is negative definite, and the function profit has a maximum value.

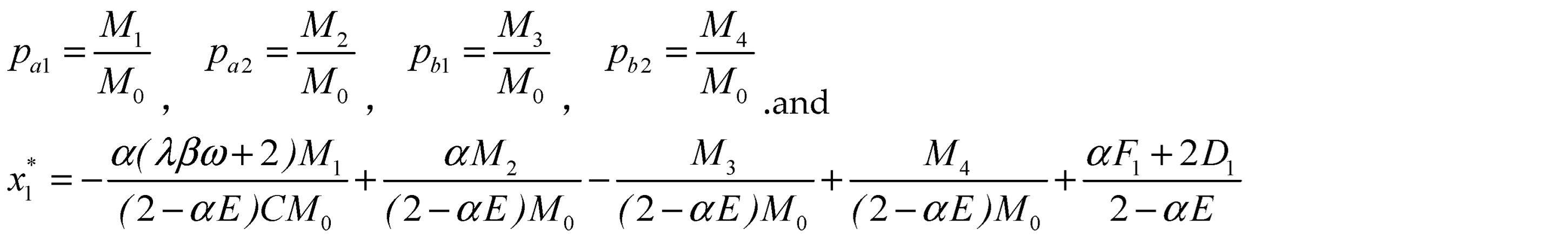

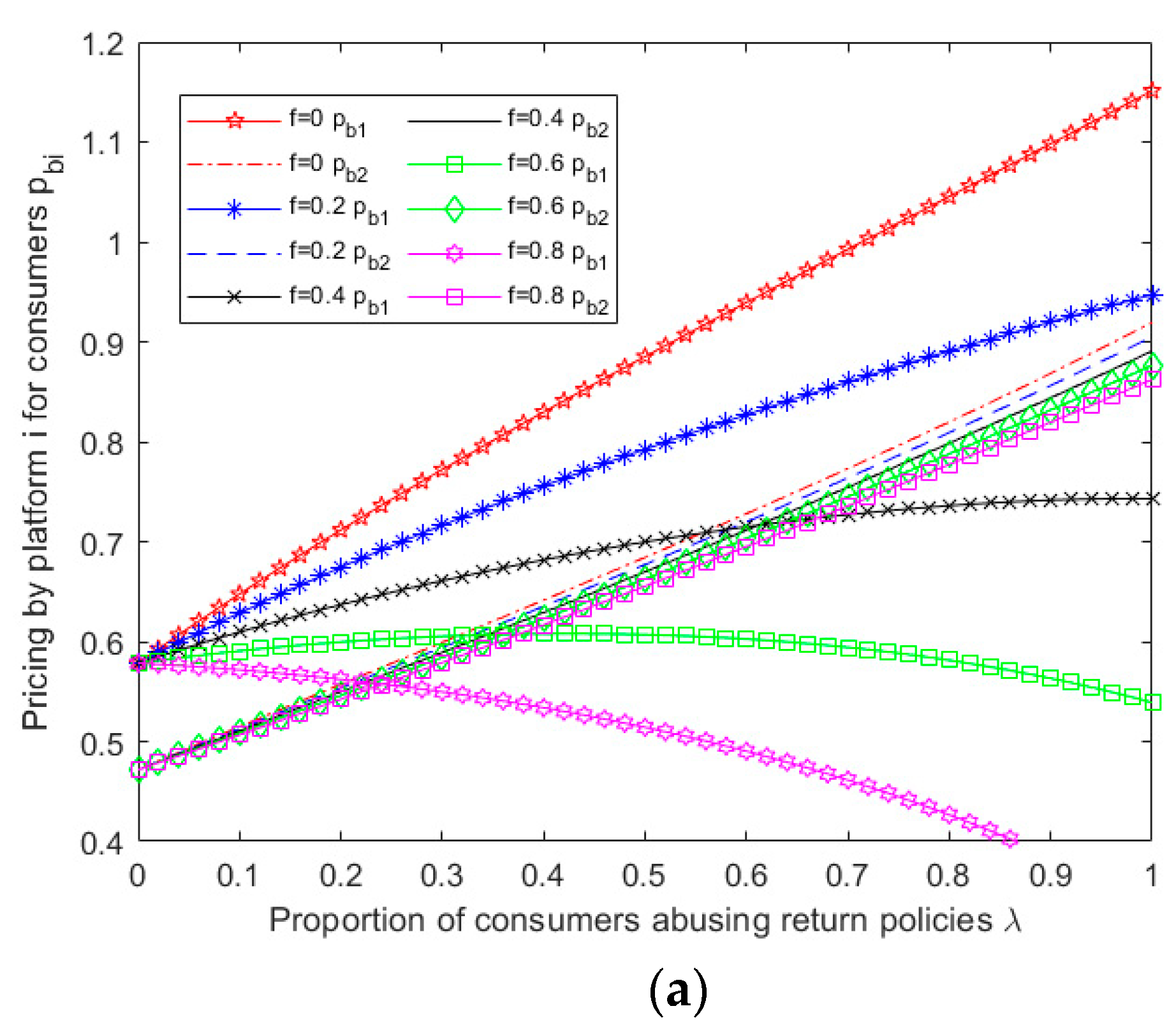

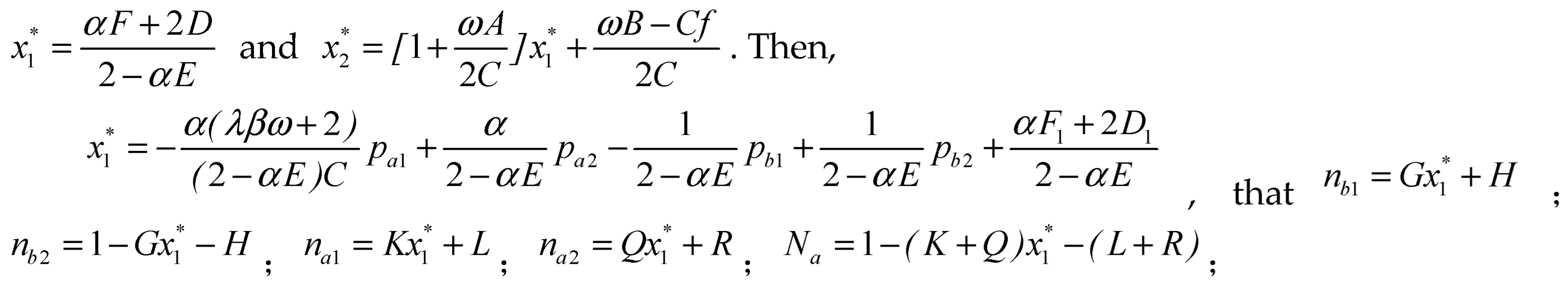

Under the given conditions, the profit functions of Platform 1 and 2 are differentiated with respect to the pricing of their respective merchants and consumers. The optimal prices for both platforms are obtained by setting the partial derivatives to zero. The optimal prices for Platform 1 are

for consumers and

for merchants, while the optimal prices for Platform 2 are

for consumers and

for merchants. The specific values of

,

,

,

and

can be found in the

Appendix A.

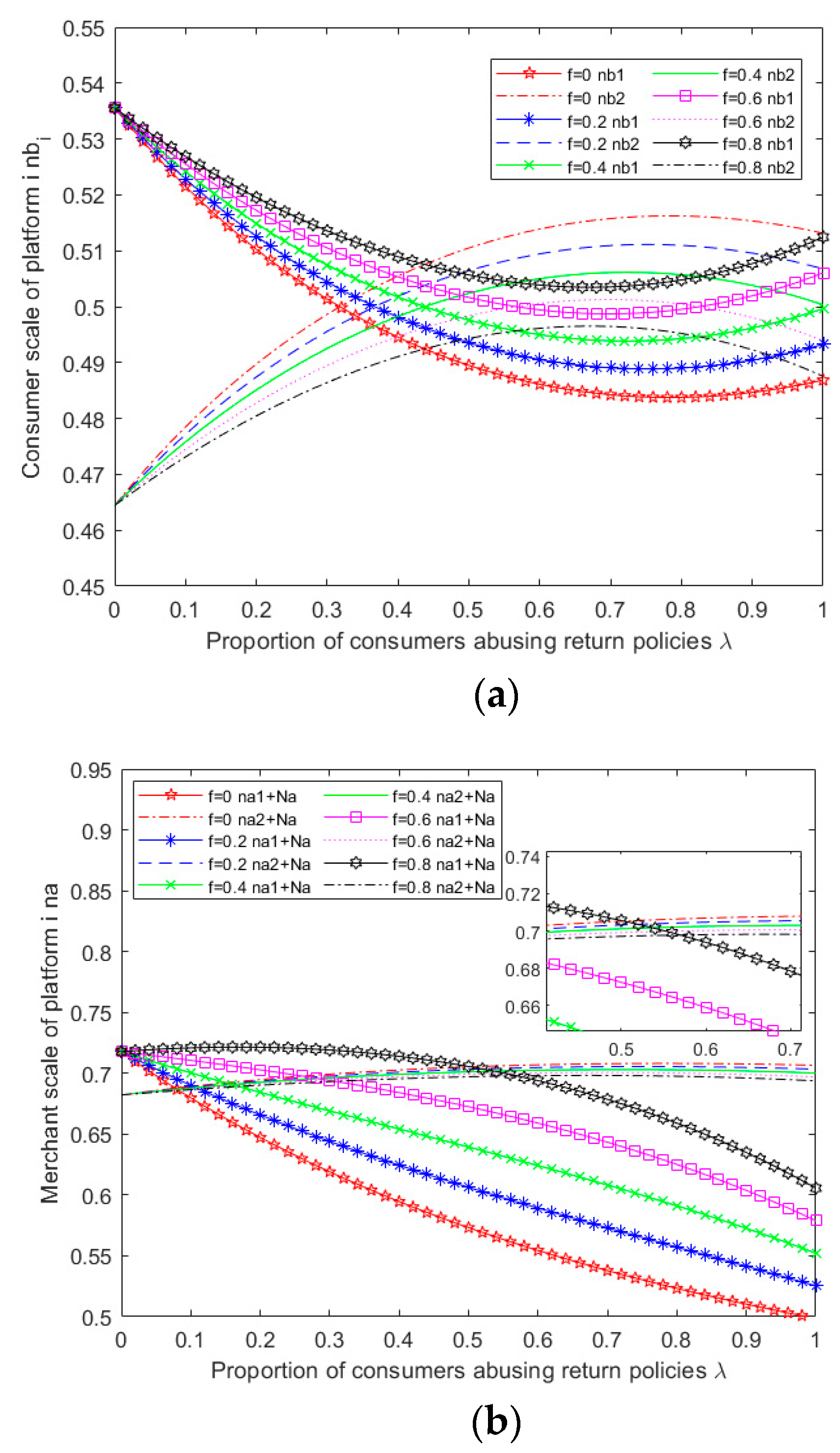

By substituting the equilibrium pricing into the expression for the equilibrium size, we obtain the equilibrium scale of bilateral users for both platforms as follows,,,,,. By substituting the above equilibrium pricing and equilibrium scale into the profit expressions for both platforms, we can obtain the optimal profit for Platform 1 and Platform 2, respectively. And the platform profit expressions are showed in the appendix A.

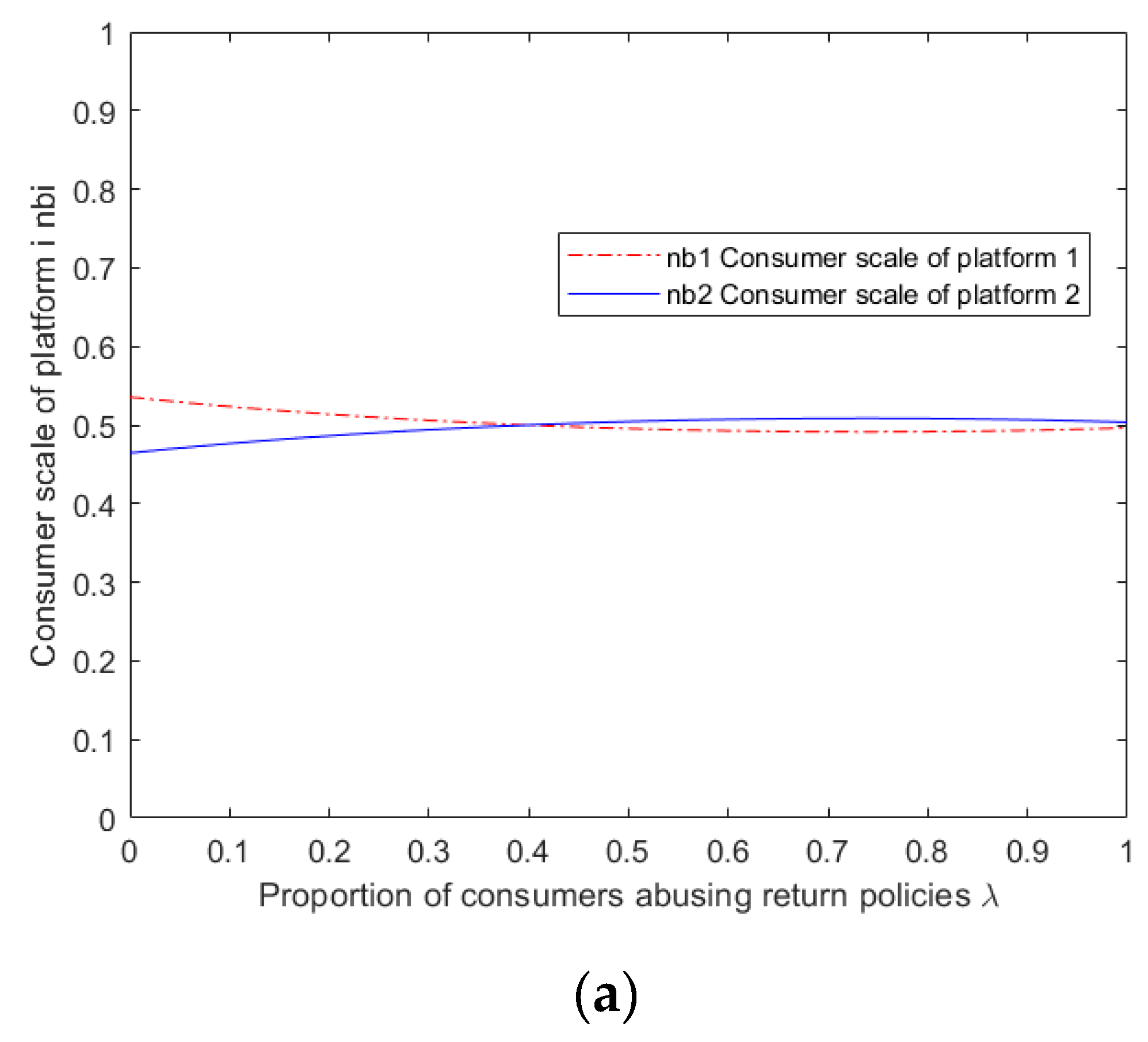

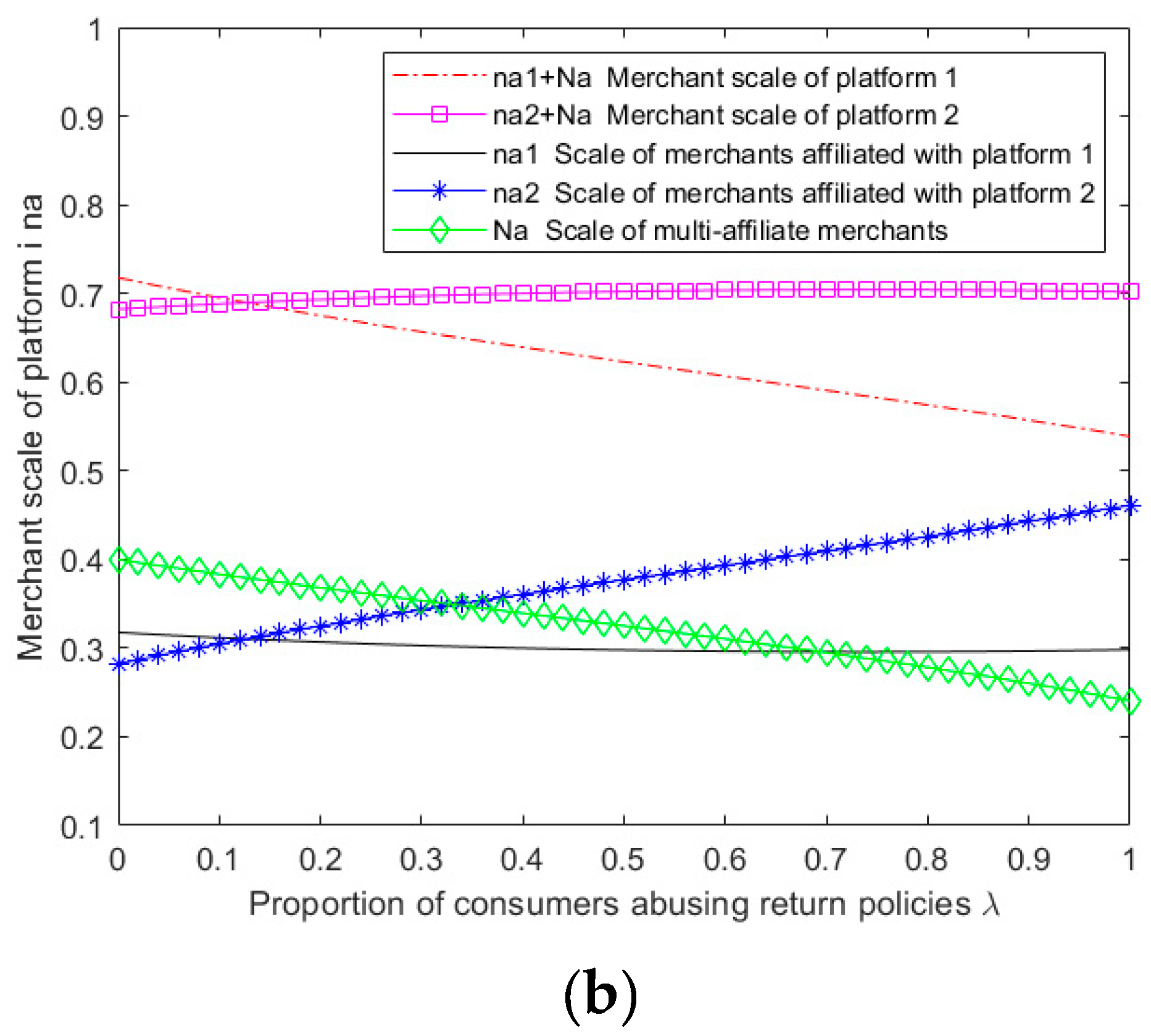

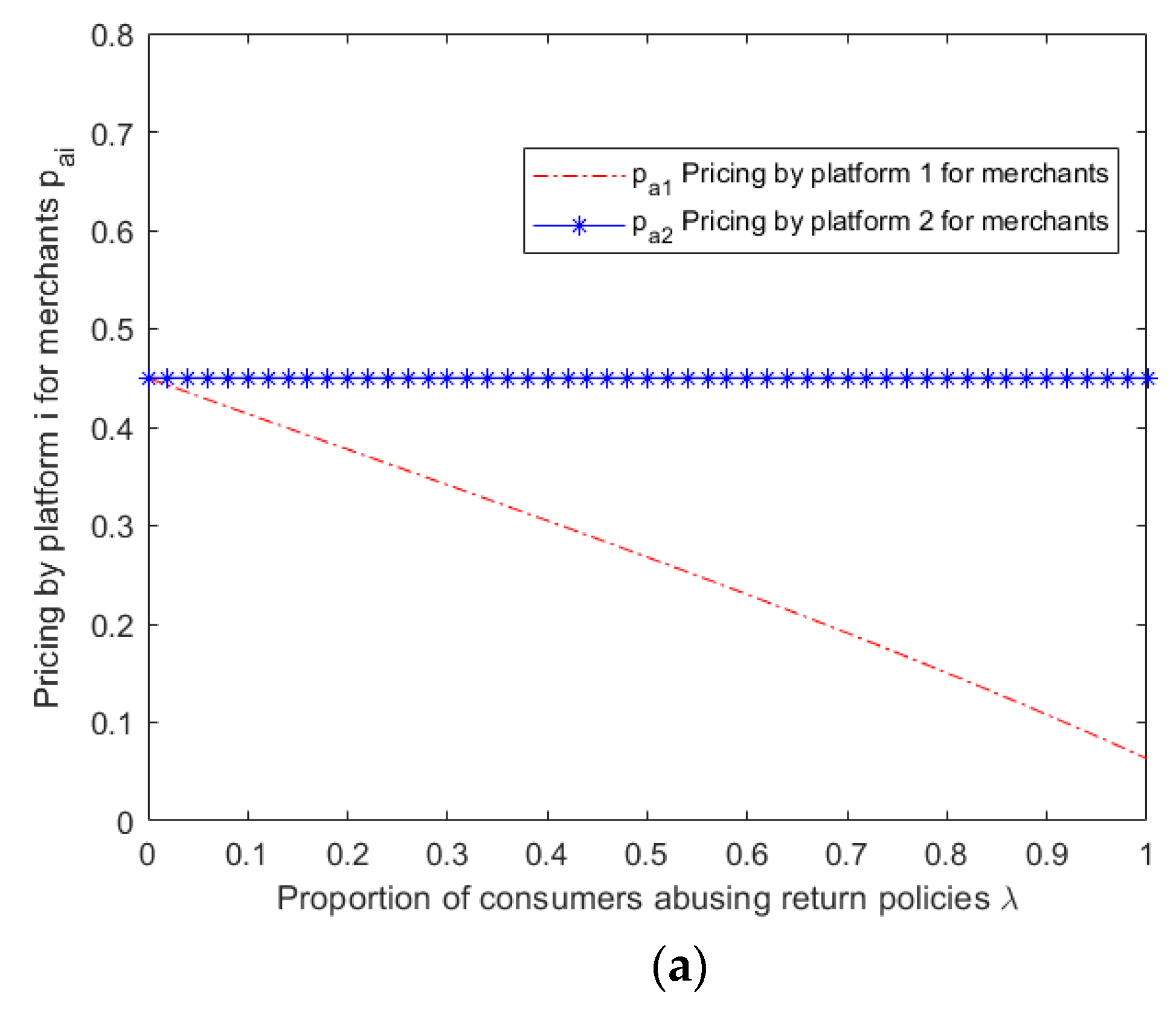

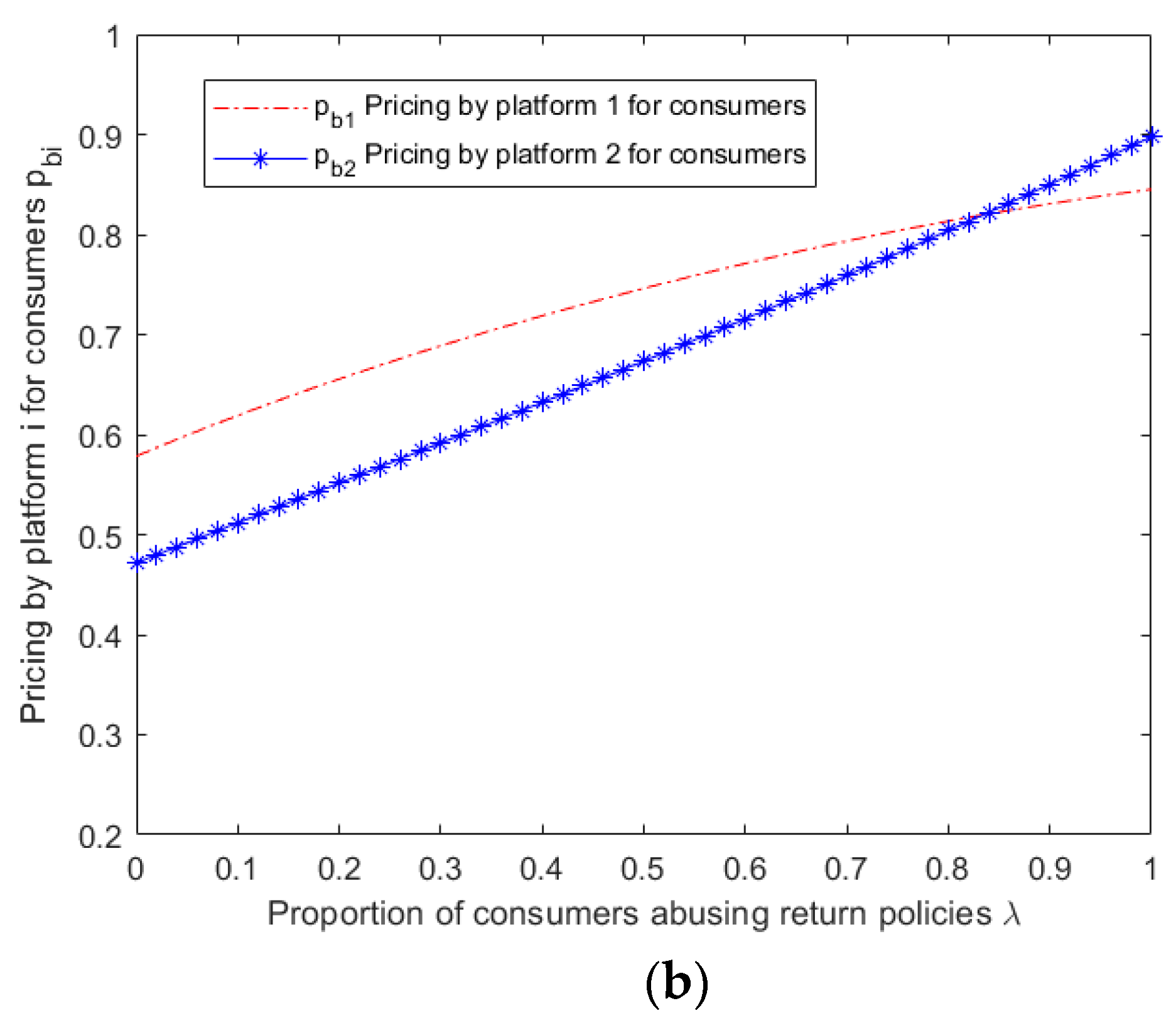

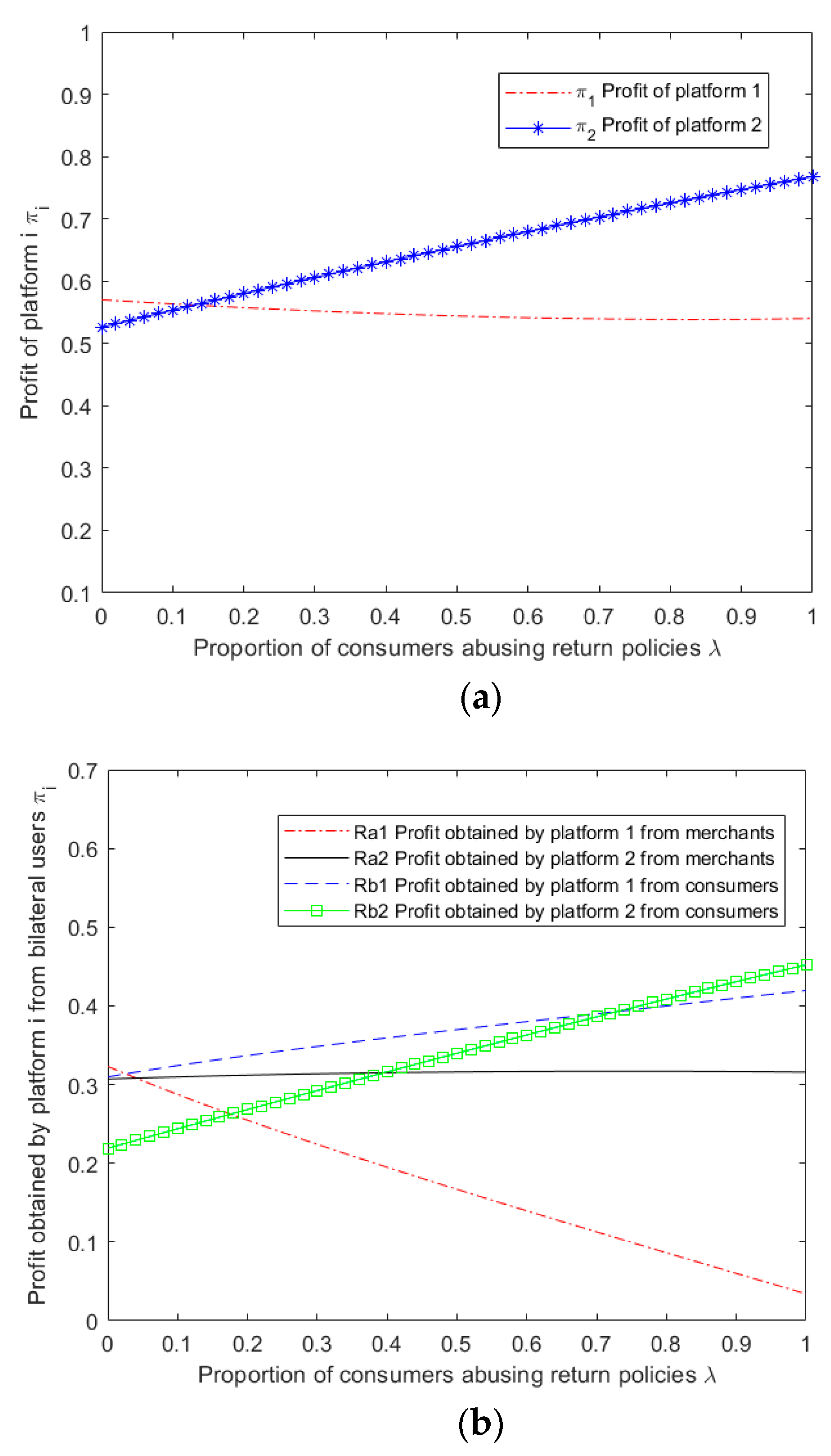

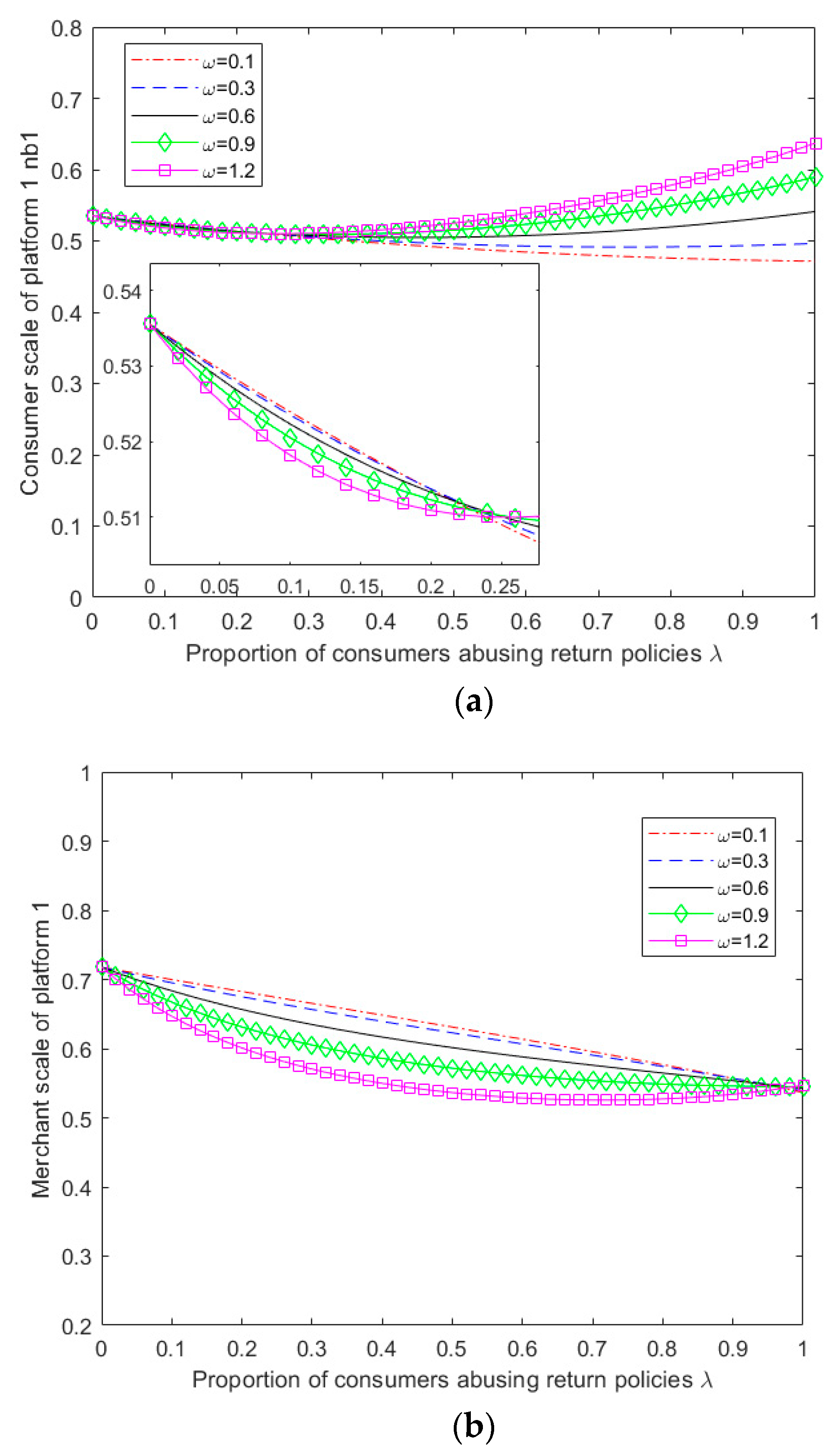

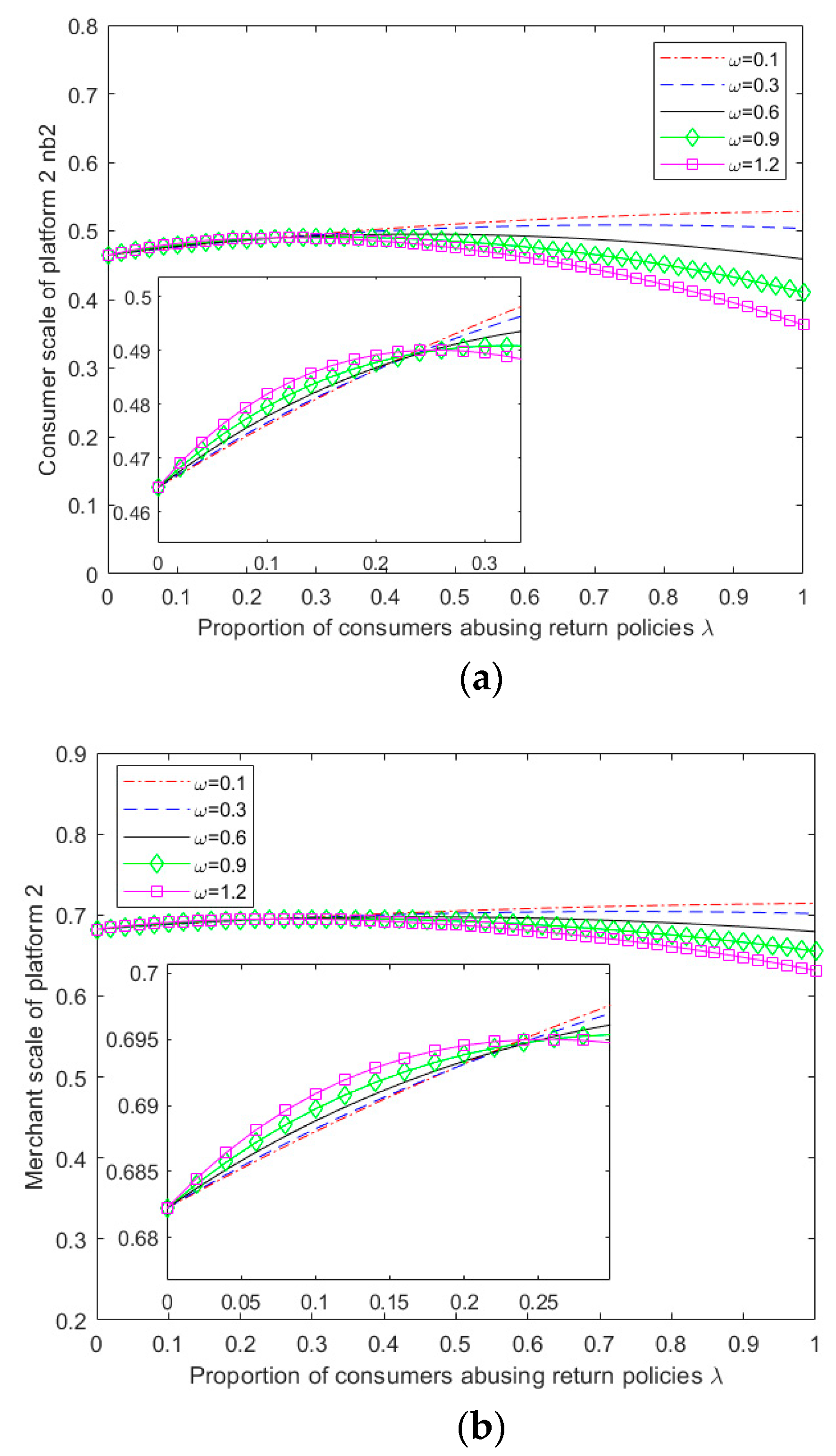

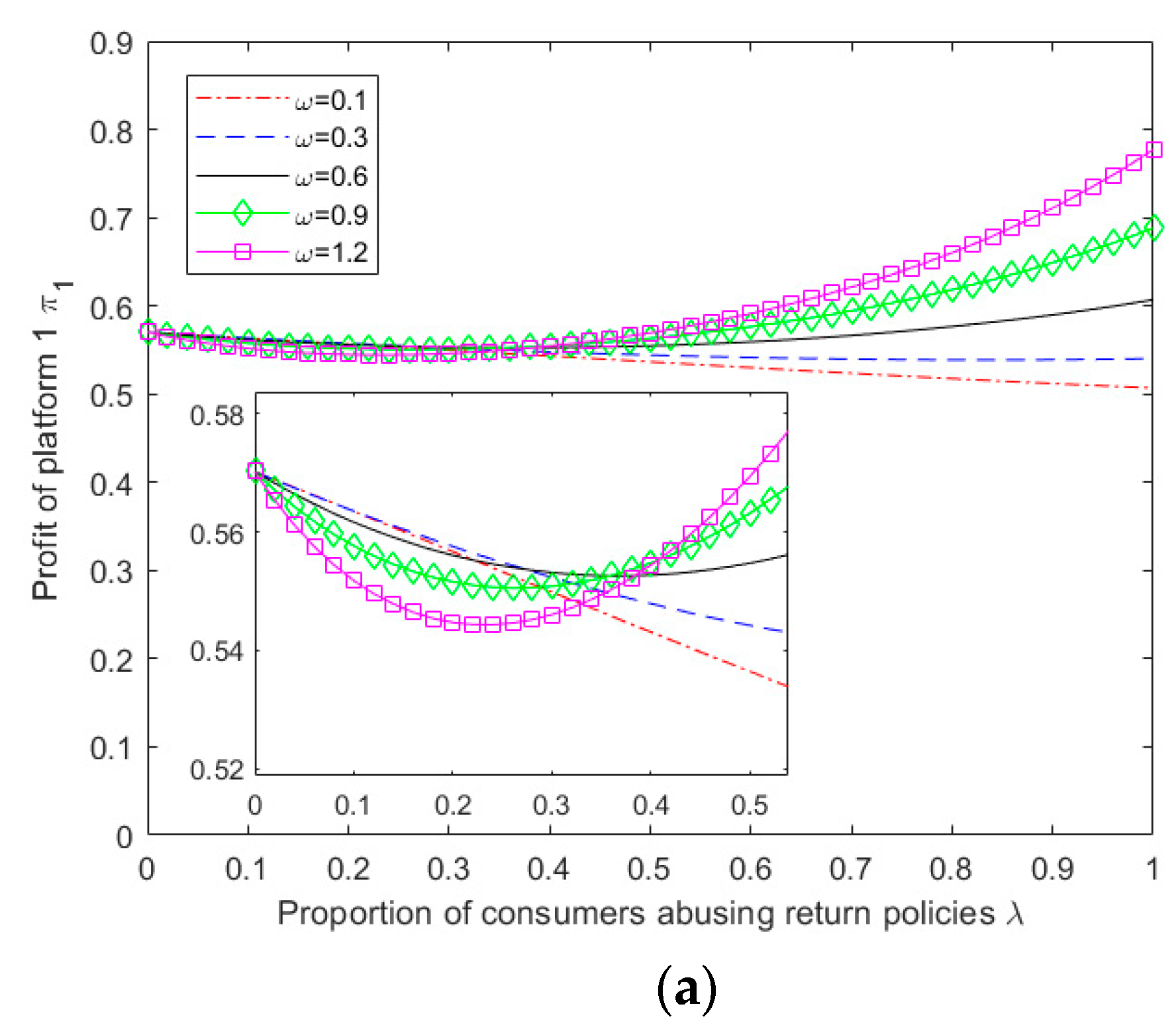

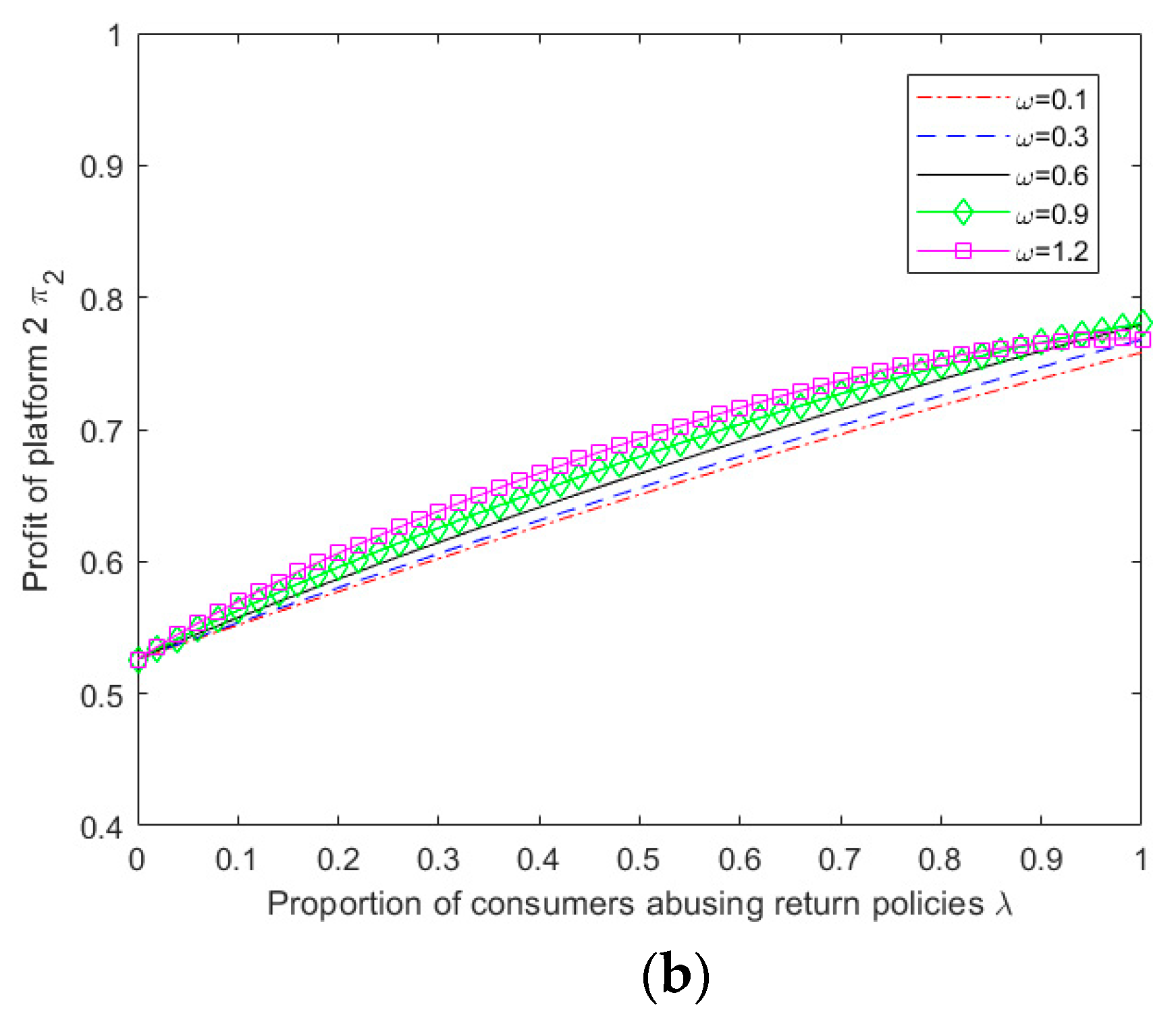

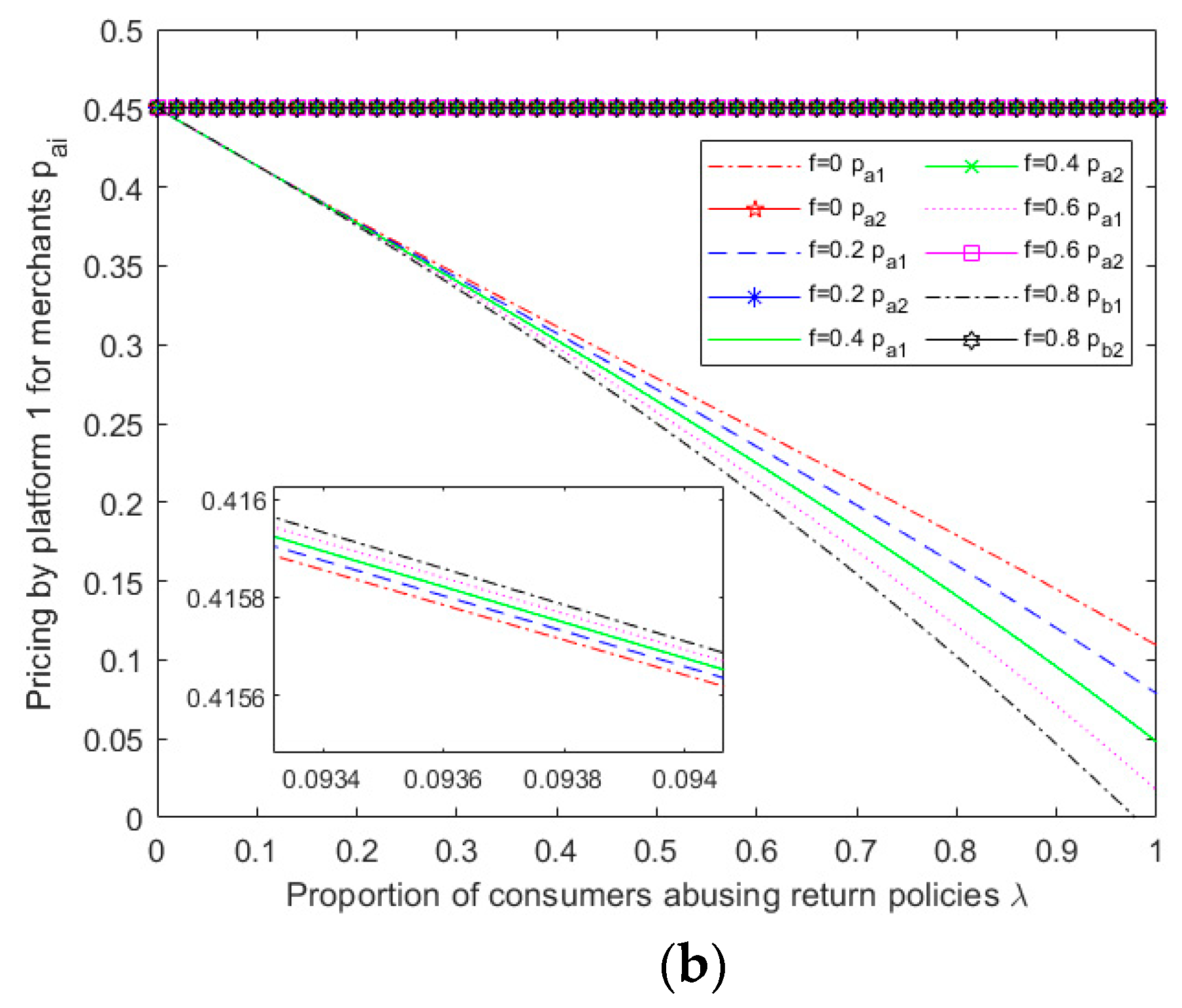

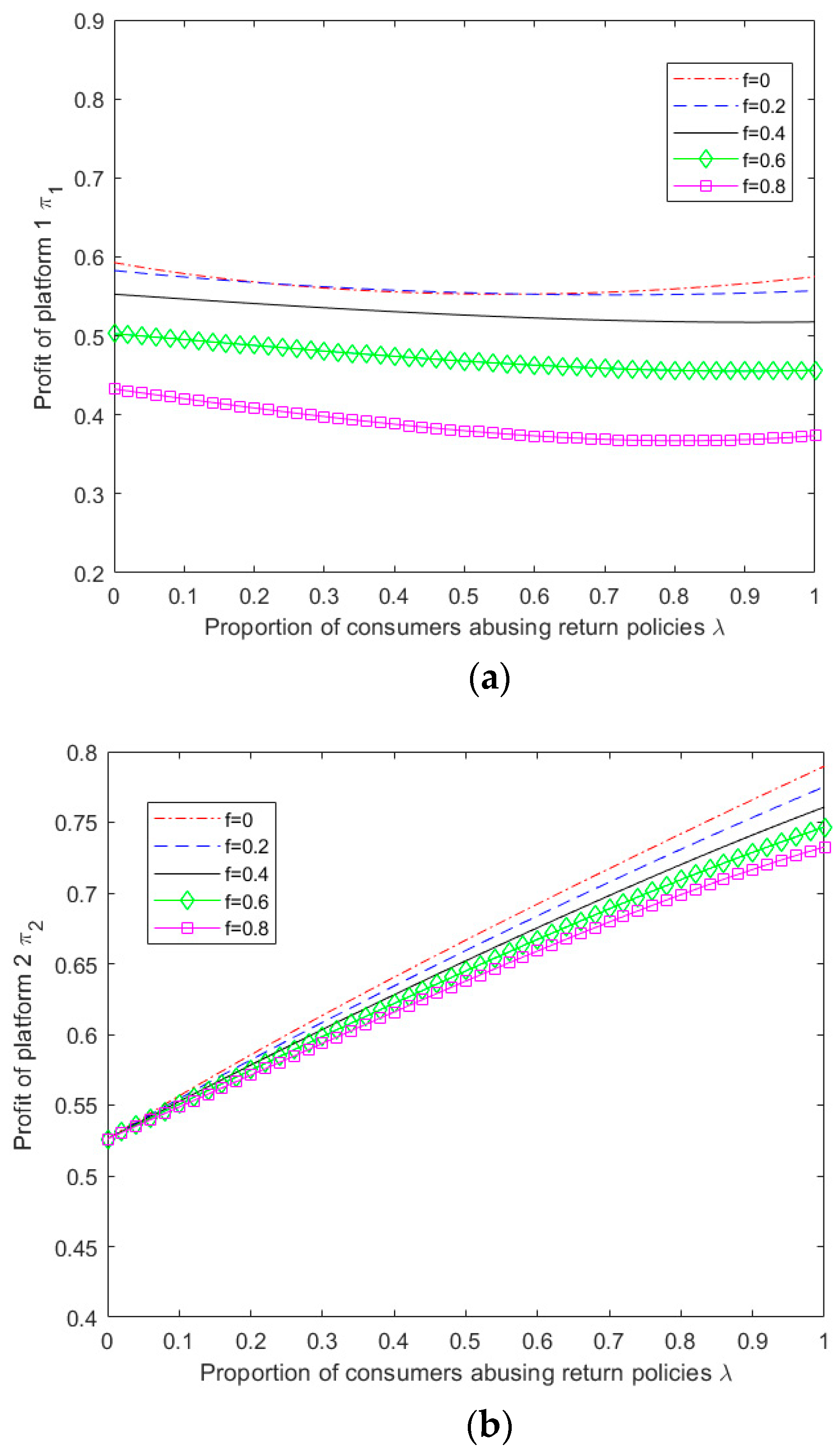

Given the complexity of the expressions obtained from the above model for equilibrium pricing, user size, and profit for both platforms, it becomes challenging to perform a theoretical analysis of the impact of abusive consumer returns on platform service strategies. Therefore, this study employs MATLAB 2019b software to perform numerical simulation analysis on the obtained results, specifically considering the scenario of multi-homing merchants ,and explore the impact of parameter variation on the outcome of competition between platforms.

From and ,that ,then and

From and ,that ,then and  Profit

Profit