1. Introduction

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a widely used tool that enables the detection of risk factors and provides a comprehensive assessment of older people in an integrated manner. It consists of four main sections: clinical, physical, mental, and social. Different and varied evaluation tools are used to provide a reliable measure of all parameters in a common language [

1]. Among the data that are normally collected by the professionals of the elderly care centers through the VGI, and framed in the functional section, those referring to physical functioning stand out.

The physical performance of older people is closely related to the concepts of frailty, comorbidity, and sarcopenia. Physical performance tests are strongly associated with the onset of functional dependence; therefore, their use is advised to develop a risk assessment strategy that could identify subgroups of older people, independent in activities of daily living (ADL), who are at higher risk of functional dependence [

2].

Within the lines of the European Innovation Partnership on aging, the prevention and early diagnosis of functional and cognitive impairment with interventions aimed at frailty is defined as a main line. In addition, the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation 2014-2020 (Horizon 2020) includes 6 sub-programmes on. The Innovative Medicines Initiative 2013 also plans the "development of innovative therapeutic interventions for physical frailty and sarcopenia, as a prototype geriatric indication" [

3].

In the 1990s, the World Health Organization referred to active aging, which is defined as: "the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security with the aim of improving quality of life as people age [

3]. Thus, maintaining autonomy and independence throughout the years are primary objectives.

The Consensus Document on Frailty and Falls in Older People establishes inactivity as the most relevant frailty risk factor [

3] and proposes the SPPB instrument as a screening tool for frailty and fall risk among older people.

Older adults who are frail may progress toward dependence and disability; this process follows a pattern beginning with impairment of mobility and flexibility, which subsequently progresses to difficulties in performing daily activities and eventually prevents the proper performance of basic activities of daily living.

Several simple tests of physical performance were strongly associated with the occurrence of functional dependence. These results support the potential use of physical performance tests to develop a risk assessment strategy that could identify subgroups of older people, independent in all activities of daily living (ADLs), who are at increased risk for functional dependence [

2]. The SPPB is a standardized physical performance assessment instrument that is specifically designed to predict disability and is also capable of predicting adverse events, dependency, institutionalization, and mortality.

Other studies have confirmed its usefulness as a screening tool to detect the frailty syndrome in community-dwelling older adults [

4,

5,

6,

7]. However, a systematic review [

8], determined that, although it is a reliable and valid tool for physical performance in older adults over 60 years old, it has limited scope and is more appropriate for frail older adults who can walk and are cognitively capable of following instructions. Additionally, it is not particularly sensitive to change, so it is a useful instant screening tool, but its usefulness is limited for long-term follow-up.

The psychometric characteristics of the scale have been studied in different places and populations, obtaining good results. There is scientific evidence of its validity [

9,

10]; reference values were established according to sex and 3 age groups (between 70 and 75, between 76 and 80, and over 80). The SPPB proved to be a valid and reliable tool in the assessment of physical fitness in Colombian older adults [

11,

12]; Norwegians [

13,

14], Brazilians [

7] and Canadians [

15]; in different pathologies such as cardiac [

10,

16], asthma [

17], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [

18]; chronic kidney disease [

19], multiple sclerosis20, among others; and in different contexts, especially in the hospital environment [

10,

21] y community [

4,

5]; however, studies in institutionalised older adults are not as common [

22].

The SPPB scale has been found to be a useful tool for the assessment of lower extremity functioning in older adults and is a good predictor for numerous health outcomes such as ADL dependence, mobility difficulties, disability, hospitalisation, prolonged hospitalisation, institutionalisation and even death, as well as poorer quality of life [

10,

15,

23,

24,

25].

A systematic review on performance-based physical function assessment in people living in the community concluded that the SPPB was the most recommended tool in terms of validity, reliability and responsiveness [

26]. Another review [

27] showed that speed or SPPB were the most valid, reliable and feasible tools for the assessment of physical performance in a home environment.

Despite all previous studies, the psychometric properties of the SPPB in institutionalised Spanish older adults had not been previously explored, which was the main objective of this study. In addition, three specific objectives for this research were established: 1) to determine the reliability of the SPPB scale; 2) to determine the construct validity of the SPPB scale; 3) to determine the convergent validity of the SPPB scale.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 202 entries were recorded in a dossier prepared for this purpose and distributed to the participating centres, of which 8 were discarded because they were incorrectly completed or incomplete. Thus, the sample consisted of a total of 194 institutionalised older adult people in four residential centres: Burgos (n = 63); Aranda de Duero (n = 38); Salamanca (n = 76); San Sebastián de los Reyes (n = 17).

The geographical distribution of the sample is as follows:

- -

Province of Burgos (Spain): 63 in burgos city; and 38 in Aranda de Duero.

- -

Province of Salamanca: 76 in Salamanca coty.

- -

Province of Madrid: San Sebastián de los Reyes 17.

The ages of the participants are between 63 and 97 years old. As for the type of center in which the participants are admitted, all of them are residential centers. The ownership of the centers varies as follows: 156 are in privately owned centers and 38 in publicly owned centers.

2.2. Data collection

In order to obtain the sample, several centers managed by Grupo Norte were contacted. This is a business group dedicated to the management of care services for the elderly, among other activities. After signing a collaboration and confidentiality agreement document with the participating centers, the data collection necessary for this research was carried out. The Ethics Committee of the University of Burgos positively assessed the research plan in the IR 11/2018 Approval Committee.

Each of the participating centers performed the data collection thanks to the professionals of the multidisciplinary teams. The data, which are obtained through the participating centers as part of their routine documentation (each of these centers has its own approved data protection procedure in place, accordingly to legal requiremets) and sent to the investigating team after a process of anonymization; from this point on, they are always treated anonymously and in aggregate. Each of these centers has its own approved and current data protection procedure.

An anonymization procedure consisting of the following steps was established: 1st data collection, 2nd coding, 3rd introduction of the data into the statistical program, 4th data processing in the cross-sectional phase, and 5th custody of the anonymized data.

Therefore, non-probability and convenience sampling was performed, where no randomization procedure is carried out; this type of sampling is widely used in the health and social sciences. No sample calculation was performed and sampling errors were not taken into account.

The IBM SPSS-v5 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software program was used for the statistical analysis.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB or Guralnik Test)

It is a widely used performance test in geriatric medicine that has been validated in different study populations and is adjusted for age, sex and comorbidity. It is easy to use and does not require any equipment. The scale makes it possible to monitor follow-up over time and the evolution of the person; changes of 1 point in the SPPB are clinically significant. It is a useful tool for the assessment of mobility limitations [

3].

This tool is divided in three sections: balance (0-4 points): in the standing, semi-tandem and tandem positions; walking speed (0-4 points): in 2.4 or 4 metres; getting up and sitting down in a chair five times (0-4 points). The established sequence must be respected and the administration time is between 6 and 10 minutes.

As normative values, scores can be between 0 and 12; so that 0 is the worst situation and scores below [

10] indicate poor physical condition, frailty and high risk of falls [

3]. The ViviFrail multicomponent physical training programme for the prevention of frailty and falls in the over 70s proposes the following cut-off points [

28]: severe limitation (dependent or disabled) SPPB 0-3; moderate limitation (frail) SPPB 4-6; mild limitation (prefrail) SPPB 7-9; and minimal limitation (autonomous or robust) SPPB 10-12.

2.3.2. Barthel Index

Published to assess and monitor progress in independence in self-care in patients with neuromuscular and/or musculoskeletal pathology admitted to chronic hospitals [

29].

The British Geriatrics Society recommends its use for the assessment of basic ADLs in older patients and it is especially useful in rehabilitation units. It is administered in 5 minutes through direct observation and/or questioning of the person or their caregivers. It assesses ten basic activities and its total score ranges from 0 to 100 points (90 for wheelchair users). It has very good reproducibility with weighted kappa correlation coefficients of 0.98 intraobserver and higher than 0.88 interobserver [

29]. And it has excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.90 - 0.92 [

30]. It has cut-off points established in [

3]: independence: 100; low dependence: 91-99; moderate dependence: 61-90; severe dependence: 21-60; and total dependence: <21.

2.3.3. Lawton & Brody Scale

Developed for the older population, institutionalised or not, to assess physical autonomy and instrumental ADLs and is frequently used. It assesses eight instrumental activities. It is a hetero-administered questionnaire in which the person or their carers are consulted with an administration time of 5-10 minutes.

It can be used for the assessment of the functional capacity of any person. Each area is scored according to the description that best corresponds to the subject so that each area scores a maximum of 1 point and a minimum of 0 points. The score ranges between 0 and 8 points where lower scores imply greater dependence.

It was translated, adapted and validated in Spanish, obtaining a high inter- and intra-observer reproducibility coefficient (0.94) [

29] and a good inter-observer reliability coefficient, although it presents some problems of construct [

3].

2.3.4. Global Deterioration Scale & Functional Assessment Stating (GDS-FAST)

It is an easy-to-use standardised tool that specifies the stage of clinical evolution of a patient. It is considered a "generalisable and widely applicable global measure for the assessment of cognitive impairment secondary to primary degenerative dementia [

31]". It is widely used and is one of the most common classifications for the stages of Alzheimer's disease [

32]. It consists of seven degrees of impairment (GDS 1 - GDS 7) in which both cognitive symptoms and functional impairments are assessed; it is the functional part that is of use in this research. At GDS 4 there is a deterioration of cognitive skills and functionally the ability to perform daily activities is affected. From GDS 5 onwards, the situation of the person being assessed means that he/she is no longer able to survive without assistance, i.e., he/she would be dependent for basic ADLs. The last two stages are further subdivided (SDG 6a - SDG 6e; and SDG 7a - SDG 7f) [

32].

2.3.5. Downton Risk Fall Index

This scale consists of 11 items and is intended to measure the risk of falling. Each item can be scored 1 or 0. A total score of 3 or more is indicative of a high risk of falling. It is considered to have good content validity and is a useful instrument for the prediction of fall risk in the residential setting [

33].

The Downton scale was developed for older adults in intensive care units. Subsequently, research was conducted in residential facilities for the elderly [

33] which concluded that it is also a useful instrument for the prediction of fall risk in the residential setting. This study also showed a higher sensitivity at three months.

2.4. Statistical analysis

First, a descriptive analysis of the sample was performed in such a way that the categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while the quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. After this, a normality analysis was performed for the quantitative variables with the Kolmogorof-Smirnof test, the result of which showed that the sample did not conform to normality (p > .05).

Subsequently, we proceeded to the psychometric analysis of the SPPB scale, for which several actions were performed. First, for the reliability analysis, internal consistency was tested by means of Cronbach's alpha, correlations between the items and the total score, and the half-and-half test. For the validity analysis, construct validity was tested by means of an exploratory factor analysis, multi-dimensional scaling and the validity of known groups; and convergent validity by means of the correlation with the Barthel index, Lawton and Brody scale and GDS-FAST.

3. Results

The sample of 194 institutionalised older adult people has a mean age of 86.46 years (SD ± 9.01). Most of the participants are in a situation of dependency (46%) or frailty (43.8%).

Appendix A shows the descriptive data of for quantitative variables;

Appendix B shows the descriptive data according to frequencies and percentages of the GDS-FAST and SPPB scale according to dependent, fragile, pre-fragile and robust score ranges [

28].

3.1. Results for Reliability analysis

3.1.1. Results for Internal Consistency

The obtained Cronbach's alpha was .86. Additionally, Cronbach's alpha for each of the items that were eliminated ranges from .77 to .85, and the overall corrected item correlation is always higher than .69.

High correlations between each item of SPPB with each other were found, with correlation coefficients between .704 and .771 (p<.001). Correlations between each item and the total score of SPPB were also high, with correlation coefficients between .839 and .940 (p<.001).

The reliability of the SPPB scale was also examined using the half-and-half test as shown in

Table 1; a value indicating very good reliability.

3.2. Results for Validity analysis

3.2.1. Results for Construct Validity

A principal components analysis with oblique rotation was performed as the correlations between the items were higher than .70 in all cases. None of the three items was eliminated as they were all grouped into a single factor with factor loadings between .858 and .905.

In the proposed solution, eigenvalues greater than 1 determined that the scale would be composed of a single (unidimensional) dimension. This explains 78.83% of the variance; the three items have factor loadings higher than .80 within the single factor and communalities higher than .73 (

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4). Since it is a one-dimensional scale, rotation is not carried out.

Finally, a scale with a single dimension composed of three items is obtained. Barlett's test of sphericity was significant (282.48; gl = 3; p<.001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin sample size adequacy indicator was appropriate (.726).

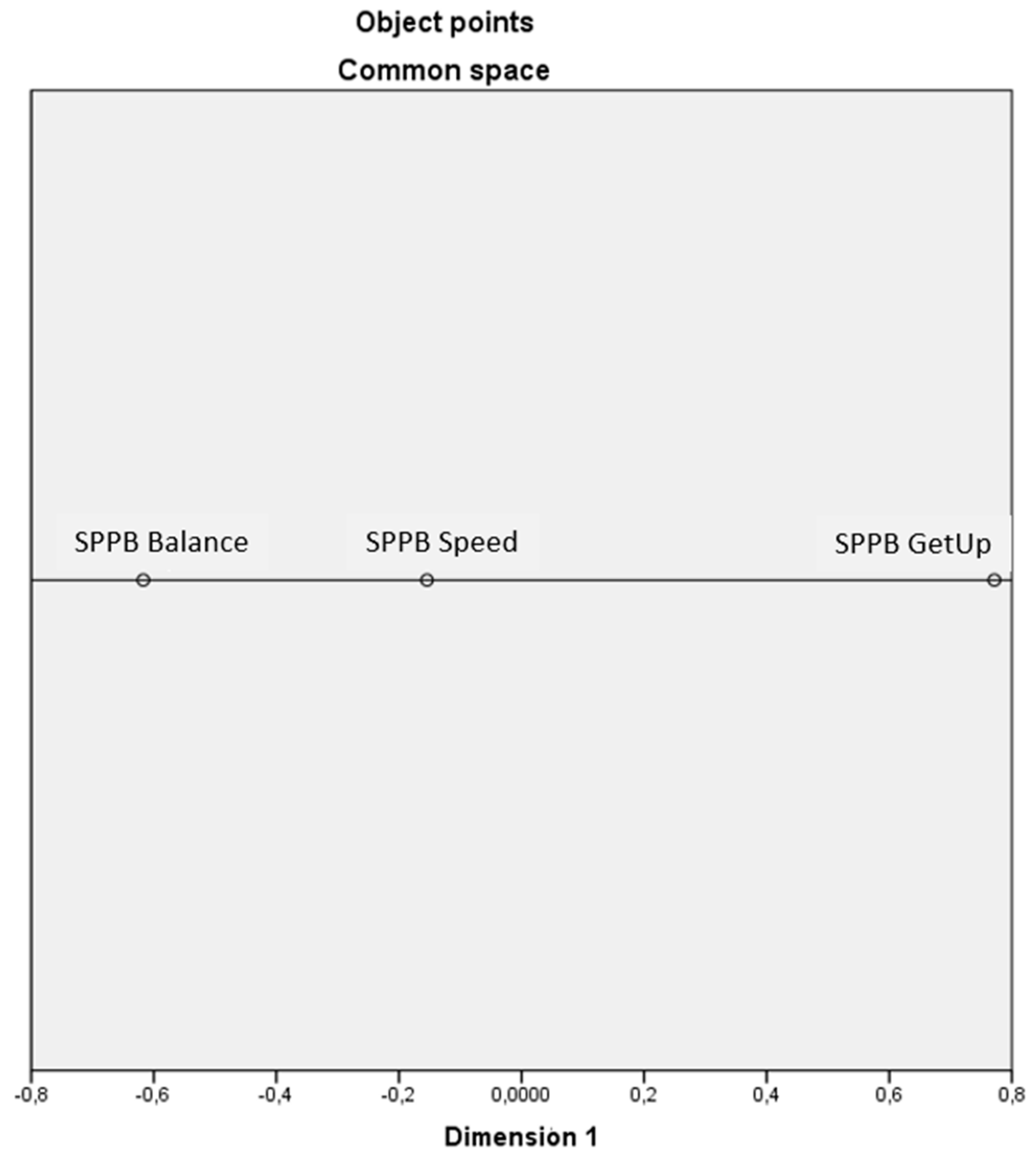

The graph obtained from the multidimensional scaling analysis (

Figure 1) shows that the SPPB is a one-dimensional scale; with final coordinates and distances shown in the

Table 5 and

Table 6.

The stress and fit measures show a very low stress index, so the proposed model is considered appropriate (

Table 7).

There is evidence associating a higher risk of falls with worse physical performance [

34,

35], which is why the falls risk variable is chosen for this analysis.

Table 8 shows the existence of statistically significant differences in the SPPB score for the groups with and without falls risk.

3.2.2. Results for Convergent Validity

The scores of each SPPB item and its total score show significant correlation with ADL (Barthel Index), instrumental ADL (Lawton and Brody) and functionality (GDS-FAST) scores as shown in

Table 9.

4. Discussion

The descriptive statistics reveal that the study population is older people and that most of the participants are in a situation of dependency (46%) or frailty (43.8%) which is consistent with data reported by other studies [

3,

36]. The sample is therefore considered to be in line with the situation in residential care homes for older people and representative of this population.

This study shows a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .863, which implies a good internal consistency of the scale if we take into account that alpha values between 0.7 and 0.8 are considered "good" [

37]. In turn, it is also necessary to point out that a value above .90 would indicate that several items are measuring exactly the same thing (redundancy or duplication) [

37], so we can consider that this is not the case with our scale. Taking also into account that the alpha values between .774 and .851 with each deleted item and that the total correlation with the corrected items is greater than .69, we can also affirm that it is not necessary to delete any of the items that make up the scale.

The results obtained for the item-total score correlation show good homogeneity, i.e., the three items are part of a single construct [

37]. Subsequently, in our analysis, this is confirmed by the results obtained in the factor analysis used for construct validity.

On the other hand, the internal consistency assessed by means of the half-and-half test obtains a result for the Spearman-Brown coefficient greater than .80, which means again and consistently together with the rest of the results a good internal consistency.

Based on the above, it can be affirmed that the SPPB scale has adequate internal consistency; that all its items are part of and are measuring the same construct and that the linear relationship between the sum of the scores of the items with the measured construct is fulfilled [

37].

In terms of validity, it was decided to assess construct validity and contingent validity, but content validity was not assessed, although quantitative tools whose purpose is to collect information on the importance of a variable need to verify their content validity through an analysis of the concept expressed in the variable [

38].

The most commonly used content validation processes involve the assessment of the scale items by a panel of experts, but, in this case, it is an instrument whose use has been recommended since the Consensus Document on Frailty and Falls [

3] and is widely used by geriatric physicians [

39], which gives it this de facto expert opinion. In addition, it is an instrument whose translation into Spanish has been used in other validation processes of its properties [

9,

11,

23,

40], so it is considered that this content validity process has already been carried out for this version of the tool.

As for construct validity, the exploratory factor analysis corroborated the version of the SPPB used in the literature and shows that it is composed of a single factor since the three items show a correct theoretical grouping with this single factor. Bartlet's test showed a good correlation between the variables (p<.001), and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin sample size indicator also obtained an optimal result above 0.7 as stated by Carvajal et al. [

38] (2011); Sánchez-Martínez et al. [

41] (2019) or Garmendia [

42].

The literature proposes several ways to determine the unidimensionality of an instrument, most of them using the variance explained by the first factor extracted. Thus, it is established that the amount of variance explained by the first factor should be for some authors higher than 20%, 30% or even 40% [

43]; although there is no consensus. The present research meets this criterion in either case with a total variance explained by the first factor of 78.83%. However, and due to this variability of criteria among the authors, we proceeded to carry out a multidimensional scaling whose data corroborated that the SPPB is a unidimensional tool composed of three items.

In addition, to test construct validity, we also examined the existence of differences between two known subgroups, with and without risk of falls because there are numerous studies that relate them. We used the cut-off point proposed by the Downton scale of risk of falls, which indicates that scores equal to or greater than 3 are indicative of high risk of falls [

33]. The results show that there are significant statistical differences between the groups of people with and without risk of falls both for the SPPB total score and for each of its items, results in concordance with other studies that relate falls and/or fall risk to the SPPB [35, 44–46] and, even that propose the SPPB as a good instrument in itself to measure the risk of falling [

47] and to predict those falls [

3].

The total score of the SPPB and each of its component items also have positive correlations with the scores from Barthel, Lawton, and Brody and negative correlations with the score from the GDS-FAST. This shows that the worse a person's physical performance, the more limitations they have for basic and instrumental ADLs as well as overall impairment, and that the scores from the various scales tend to converge in the same direction. The findings show that the SPPB has strong convergent validity for the sample because this link between the SPPB and ADLs has also been confirmed in previous research [

48,

49,

50].

Its multicenter design and focus on a population with particular needs and features that call for proven evaluation tools should be acknowledged as positives. The findings provide extremely valuable information that enables us to suggest the use of the SPPB to evaluate the physical capabilities of institutionalised older people. A blinding technique is indicated by the method by which the individuals in responsibility of data collection are distinct from those in charge of the statistical analysis of the data.

It is important to emphasise the study's shortcomings, which include the convenience sample it used and the absence of sample calculation or randomization. To corroborate these findings, more research along similar lines is needed.

5. Conclusions

The SPPB's Spanish version has proven to be a reliable and valid resource for geriatric specialists working in these types of facilities since it has strong validity and reliability for the assessment of the physical performance in institutionalised older adults.

The instrument was found to have good internal consistency as a sign of its reliability. The SPPB also exhibits strong convergent validity and strong construct validity for a unidimensional model.

The SPPB tool is advised for use as a component of the CGA for the evaluation of the physical or functional sphere, and it may also be a helpful marker for the beginning of frailty, dependence and fall risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M. S.-P., J.J. G.-B. and A. dS.-G.; methodology, M. S.-P., J.J. G.-B. and A. dS.-G.; software, M. S.-P.; J. F.-S., and J. M.-A.; validation, M. S.-P., J. F.-S., and J. M.-A; formal analysis, M. S.-P., J. F.-S., and J. M.-A; investigation, M. S.-P., A. G-G. and J. G.-S.; resources, M. S.-P., and A. G.-G.; data curation, M.S.-P., E. M.- P., and J. F.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.-P., J.J.G.-B, and J. F.-S.; writing—review and editing, M.S.-P., A. G.-G., J. F.-S., and J. G.-S.; visualization, M.S.-P., J.J.G.-B., A.dS.-G., E.M.-P., A.G.-G., J. F.-S., J. M.-A., and J.G.-S.; supervision, M.S.-P., J.J.G.-B, and J. M.-A.; project administration, M. S.-P. and E. M.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was prospectively registered and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Burgos (IR 11/2018).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the company Grupo Norte, who participated, on the one hand, by providing the sample necessary to carry out this research and, on the other hand, in the data collection process. We would also like to thank the professionals from each of the participating centers involved in the process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Public Involvement Statement

Aim: the participants were included in the research with the objective of evaluating the psychometric properties of the scale. Methods: They participated voluntarily, the purpose and procedure of the study and their involvement in it were explained to them. The sample used was convenience, as it was accessible to researchers. Study resuts: the results of participants reporting include both positive ans negative outcomes. Reflections/critical perspective: there were no relevbant issues with public involvement.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the STROBE for observational studies.

Appendix A

Appendix A.

Descriptive data for quantitative variables.

Appendix A.

Descriptive data for quantitative variables.

| |

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

| SPPB Balance |

194 |

0 |

4 |

1.81 |

1.52 |

| SPPB Speed |

194 |

0 |

4 |

1.57 |

1.33 |

| SPPB GetUp |

194 |

0 |

10 |

.86 |

1.28 |

| SPPB Total |

194 |

0 |

12 |

4.17 |

3.58 |

| Barthel |

194 |

0 |

100 |

58.61 |

32.97 |

| Lawton & Brody |

194 |

0 |

8 |

1.49 |

2.33 |

| Downton |

194 |

0 |

7 |

2.67 |

1.57 |

Appendix B

Appendix B.

Descriptive data for ordinal variables.

Appendix B.

Descriptive data for ordinal variables.

| |

|

Frecuency |

Percentage |

Valid percentage |

Cumulative percentaje |

| GDS_FAST |

GDS1 |

32 |

16.5 |

16.5 |

16.5 |

| GDS2 |

31 |

16.0 |

16.0 |

32.5 |

| GDS3 |

15 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

40.2 |

| GDS4 |

28 |

14.4 |

14.4 |

54.6 |

| GDS5 |

42 |

21.6 |

21.6 |

76.3 |

| GDS6A |

29 |

14.9 |

14.9 |

91.2 |

| GDS7A |

17 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

100.0 |

| Total |

194 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| SPPB |

Dependent |

91 |

46.9 |

46.9 |

46.9 |

| |

Frail |

52 |

26.8 |

26.8 |

73.7 |

| |

Prefrail |

33 |

17.0 |

17.0 |

90.7 |

| |

Robust |

18 |

9.3 |

9.3 |

100.0 |

| |

Total |

194 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

References

- Redín, JM. Valoración geriátrica integral (I). Evaluación del paciente geriátrico y concepto de fragilidad Comprehensive geriatric assessment (I). Evaluation of the geriatric patient and the concept of fragility. In: ANALES Sis San Navarra. Vol 22. ; 1999.

- Gill TM, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Assessing risk for the onset of functional dependence among older adults: the role of physical performance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(6):603-609. [CrossRef]

- Abizanda P, Espinosa JM, Vela R, López A. Documento de consenso sobre Prevención de Fragilidad y Caídas en la Persona Mayor. Estrategia de Promoción de la Salud y Prevención en el SNS. Published online 2014.

- Perracini MR, Mello M, de Oliveira Máximo R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the short physical performance battery for detecting frailty in older people. Phys Ther. 2020;100(1):90-98. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves RS dos SA, de Figueiredo KMOB, Fernandes SGG, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Short Physical Performance Battery in Detecting Frailty and Prefrailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Results From the PRO-EVA Study. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. Published online 2022:10-1519. [CrossRef]

- Fukui K, Maeda N, Sasadai J, et al. Predicting ability of modified short physical performance battery. Int J Gerontol. 2020;14(3):212-216.

- Rocco LLG, Fernandes TG. Validity of the short physical performance battery for screening for frailty syndrome among older people in the Brazilian Amazon region. A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 2020;138:537-544. [CrossRef]

- Kameniar K, Mackintosh S, Van Kessel G, Kumar S. The psychometric properties of the Short Physical Performance Battery to assess physical performance in older adults: a systematic review. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. Published online 2022:10-1519. [CrossRef]

- Cabrero-García J, Munoz-Mendoza CL, Cabanero-Martínez MJ, González-Llopís L, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Reig-Ferrer A. Valores de referencia de la Short Physical Performance Battery para pacientes de 70 y más años en atención primaria de salud. Aten Primaria. 2012;44(9):540-548.

- Franchignoni F, Giordano A, Rinaldo L, Kara M, Özçakar L. Assessing individual-level measurement precision of the Short Physical Performance Battery using the test information function. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2023;46(1):46-52. [CrossRef]

- Gómez JF, Curcio CL, Alvarado B, Zunzunegui MV, Guralnik J. Validity and reliability of the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB): a pilot study on mobility in the Colombian Andes. Colomb Med. 2013;44(3):165-171. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Vélez R, López Sáez de Asteasu M, Morley JE, Cano-Gutierrez CA, Izquierdo M. Performance of the Short Physical Performance Battery in identifying the frailty phenotype and predicting geriatric syndromes in community-dwelling elderly. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:209-217. [CrossRef]

- Bergland A, Strand BH. Norwegian reference values for the short physical performance battery (SPPB): the Tromsø study. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Olsen CF, Bergland A. Reliability of the Norwegian version of the short physical performance battery in older people with and without dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Freire AN, Guerra RO, Alvarado B, Guralnik JM, Zunzunegui MV. Validity and reliability of the short physical performance battery in two diverse older adult populations in Quebec and Brazil. J Aging Health. 2012;24(5):863-878. [CrossRef]

- Miyata K, Igarashi T, Tamura S, Iizuka T, Otani T, Usuda S. Rasch analysis of the Short Physical Performance Battery in older inpatients with heart failure. Disabil Rehabil. Published online 2023:1-6. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira JM de, Spositon T, Cerci Neto A, Soares FMC, Pitta F, Furlanetto KC. Functional tests for adults with asthma: validity, reliability, minimal detectable change, and feasibility. Journal of Asthma. 2022;59(1):169-177.

- Medina-Mirapeix F, Bernabeu-Mora R, Llamazares-Herrán E, Sánchez-Martínez MP, García-Vidal JA, Escolar-Reina P. Interobserver reliability of peripheral muscle strength tests and short physical performance battery in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective observational study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(11):2002-2005. [CrossRef]

- Johnstone LM, Roshanravan B, Rundell SD, et al. Instrumented and Standard Measures of Physical Performance in Adults With Chronic Kidney Disease. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2022;13(3):110-118. [CrossRef]

- Motl RW, Learmonth YC, Wójcicki TR, et al. Preliminary validation of the short physical performance battery in older adults with multiple sclerosis: secondary data analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Fisher S, Ottenbacher KJ, Goodwin JS, Graham JE, Ostir G V. Short physical performance battery in hospitalized older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21:445-452. [CrossRef]

- Tabue-Teguo M, Dartigues JF, Simo N, Kuate-Tegueu C, Vellas B, Cesari M. Physical status and frailty index in nursing home residents: Results from the INCUR study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;74:72-76. [CrossRef]

- Poveda Asencio, V. Recopilación de test de campo para la valoración de la condición física en mayores. Published online 2015.

- Somech J, Joshi A, Mancini R, et al. Comparison of Questionnaire and Performance-Based Physical Frailty Scales to Predict Survival and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. Published online 2023:e026951. [CrossRef]

- Oh B, Cho B, Choi HC, et al. The influence of lower-extremity function in elderly individuals’ quality of life (QOL): an analysis of the correlation between SPPB and EQ-5D. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58(2):278-282. [CrossRef]

- Freiberger E, De Vreede P, Schoene D, et al. Performance-based physical function in older community-dwelling persons: a systematic review of instruments. Age Ageing. 2012;41(6):712-721. [CrossRef]

- Mijnarends DM, Meijers JMM, Halfens RJG, et al. Validity and reliability of tools to measure muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(3):170-178. [CrossRef]

- Vivifrail. Proyecto Vivifrail. Guía práctica para la prescripción de un programa de entrenamiento físico multicomponente para la prevención de la fragilidad y caídas en mayores de 70 años. Published 2016. https://vivifrail.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/VIVIFRAILESP-Interactivo.pdf.

- Gobierno de Aragón, G. Programa de atención a enfermos crónicos dependientes. Anexo IX: Escalas de valoración funcional y cognitiva Recuperado de: Http://www aragon es/estaticos/ImportFiles/09/docs/Ciudadano/InformacionEstadistica Sanitaria/InformacionSanitaria/programa+ atencion+ enfermos+ cronicos+ dependientes pdf. Published online 2009.

- Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(8):703-709. [CrossRef]

- Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. Published online 1982. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad Política Social e Igualdad. Guía de práctica clínica sobre la atención integral a las personas con enfermedad de Alzheimer y otras demencias. Published online 2010.

- Rosendahl E, Lundin-Olsson L, Kallin K, Jensen J, Gustafson Y, Nyberg L. Prediction of falls among older people in residential care facilities by the Downton index. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15(2):142-147. [CrossRef]

- Chen JC, Liang CC, Chang QX. Comparison of fallers and nonfallers on four physical performance tests: A prospective cohort study of community-dwelling older indigenous Taiwanese women. Int J Gerontol. 2018;12(1):22-26. [CrossRef]

- Fukui K, Maeda N, Komiya M, et al. The relationship between Modified Short Physical Performance Battery and falls: a cross-sectional study of older outpatients. Geriatrics. 2021;6(4):106. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, G. Prevalence of frailty in nursing homes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(11):940-945. [CrossRef]

- Luján Tangarife JA, Cardona Arias JA. Construcción y validación de escalas de medición en salud: revisión de propiedades psicométricas. Published online 2015.

- Carvajal A, Centeno C, Watson R, Martínez M, Sanz Rubiales Á. ¿Cómo validar un instrumento de medida de la salud?. Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra. 2011;34:63-72.

- Bruyère O, Beaudart C, Reginster JY, et al. Assessment of muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance in clinical practice: an international survey. Eur Geriatr Med. 2016;7(3):243-246. [CrossRef]

- Poveda Asensio, V. Recopilación de test de campo para la valoración de la condición física en mayores (trabajo final de grado). Universidad Miguel Hernández Recuperado de: https://pdfs semanticscholar org/170c/416cce7a2dbb4b76164e7b2aafa76f1dfeb6 pdf. Published online 2014.

- Sánchez-Martínez MP, Bernabeu-Mora R, García-Vidal JA, San Agustín RM, Gacto-Sánchez M, Medina-Mirapeix F. Estructura y propiedades métricas de un cuestionario para medir discapacidad en las actividades de movilidad en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (cuestionario DIAMO-EPOC). Rehabilitacion (Madr). 2019;53(4):232-239.

- Garmendia, ML. Análisis factorial: una aplicación en el cuestionario de salud general de Goldberg, versión de 12 preguntas. Revista chilena de salud pública. 2007;11(2):57-65. [CrossRef]

- León, AB. La unidimensionalidad de un instrumento de medición: perspectiva factorial. Revista de psicología. 2006;24(1):53-80. [CrossRef]

- Lauretani F, Ticinesi A, Gionti L, et al. Short-Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score is associated with falls in older outpatients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(10):1435-1442. [CrossRef]

- Hua A, Quicksall Z, Di C, et al. Accelerometer-based predictive models of fall risk in older women: a pilot study. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Park WC, Kim M, Kim S, et al. Introduction of Fall Risk Assessment (FRA) system and cross-sectional validation among community-dwelling older adults. Ann Rehabil Med. 2019;43(1):87. [CrossRef]

- Welch SA, Ward RE, Beauchamp MK, Leveille SG, Travison T, Bean JF. The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB): a quick and useful tool for fall risk stratification among older primary care patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(8):1646-1651. [CrossRef]

- Casas-Herrero A, Anton-Rodrigo I, Zambom-Ferraresi F, et al. Effect of a multicomponent exercise programme (VIVIFRAIL) on functional capacity in frail community elders with cognitive decline: study protocol for a randomized multicentre control trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Loveland PM, Reijnierse EM, Island L, Lim WK, Maier AB. Geriatric home-based rehabilitation in Australia: Preliminary data from an inpatient bed-substitution model. J Am Geriatr Soc. Published online 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Zhang J, Shen S, et al. Clinical frailty scale and biomarkers for assessing frailty in elder inpatients in China. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(1):77-83. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).