Submitted:

18 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. CDM Model

-

Hubble Constant(h): It represents the universe’s current pace of expansion. Its value is estimated to be around 0.68. It can be represented mathematically asrepresents the Hubble Constant.

-

Baryon Density (): It expresses the density of baryonic matter in the universe as a whole. It is the ratio of a baryon’s density to the universe’s critical density. critical density (), is the density necessary for the universe to remain flat, and its value is determined by the gravitational constant (G) and the Hubble constant (). It is written as follows:Now, is given by:is a proportion of the total energy provided by baryonic matter. We usually useIt is a unitless quantity as it is a density ratio.

-

Dark Matter Density (): It describes the density of cold dark matter in the universe. It is the ratio of a CDM’s density to the universe’s critical density. Now, is provided by:It depicts a fraction of the overall energy provided by dark matter (only exhibits interaction with the gravitational field). We usually useThe density of dark matter is also 5 times the density of baryons .

-

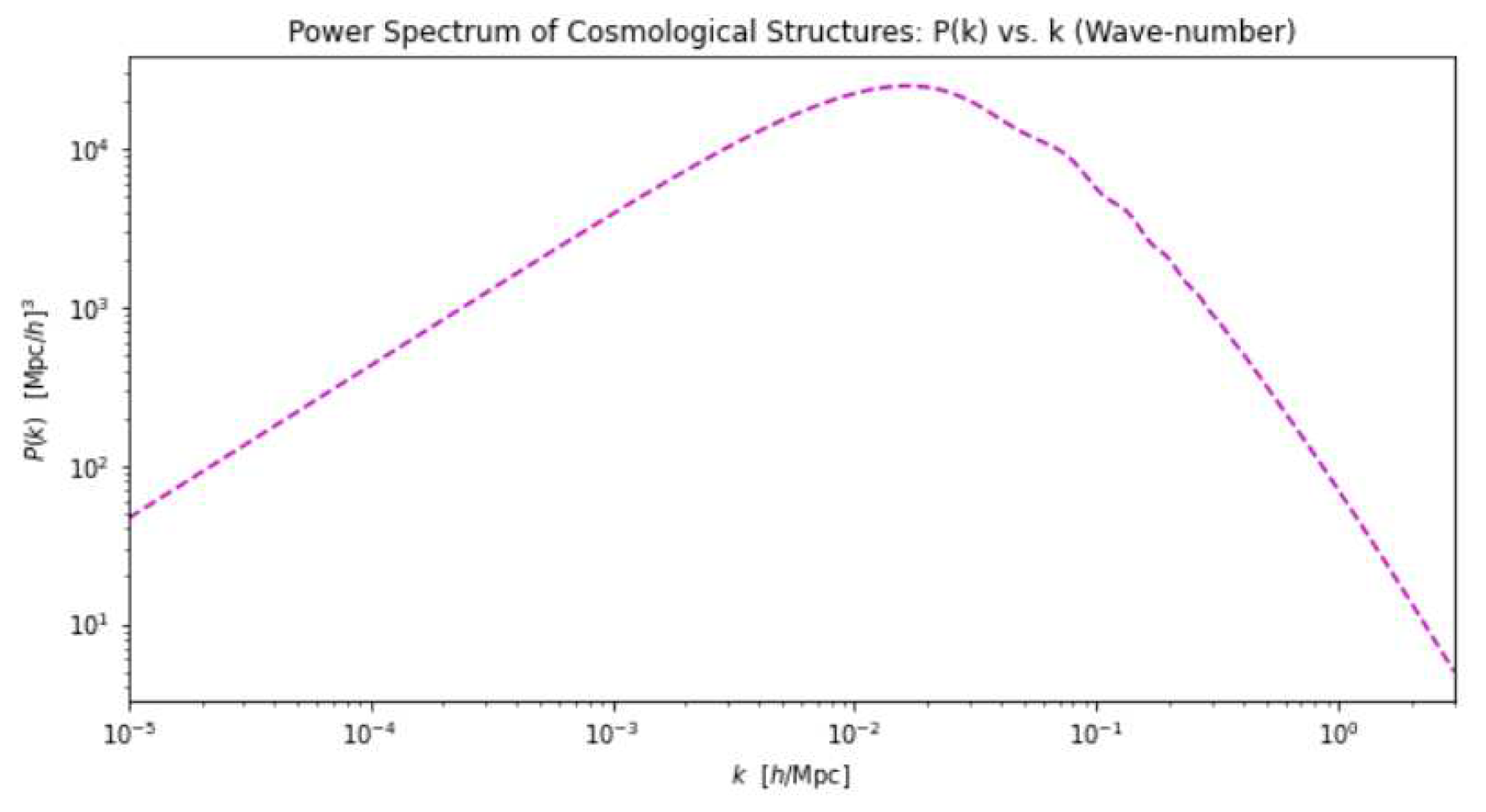

Spectral index of primordial density fluctuation (): It characterizes the early irregularities in matter distribution and states the features of the CMB and the emergence of large-scale structures. It describes ’how density fluctuations vary with scale’. A scalar index of ’1’ implies that the variance is the same in all directions. It can be expressed mathematically asIn this case, the power spectrum depicts the amplitude of density variations as a function of wave-number (k). We usually use

-

Scalar amplitude of primordial density fluctuation (): It indicates the magnitude of the oscillations in primordial density. It is commonly used to keep track of temperature fluctuations in the CMB. It is mathematically stated asThe equation determines the value of the power spectrum at a certain pivot scale, which is generally indicated as . Typically, we apply

- Optical depth due to the epoch of re-ionization (: It is a unitless number that measures the free electron opacity of the CMB radiation in the line of sight. A greater value of () indicates a higher potential for CMB photon scattering or absorption by free electrons. Typically, we use

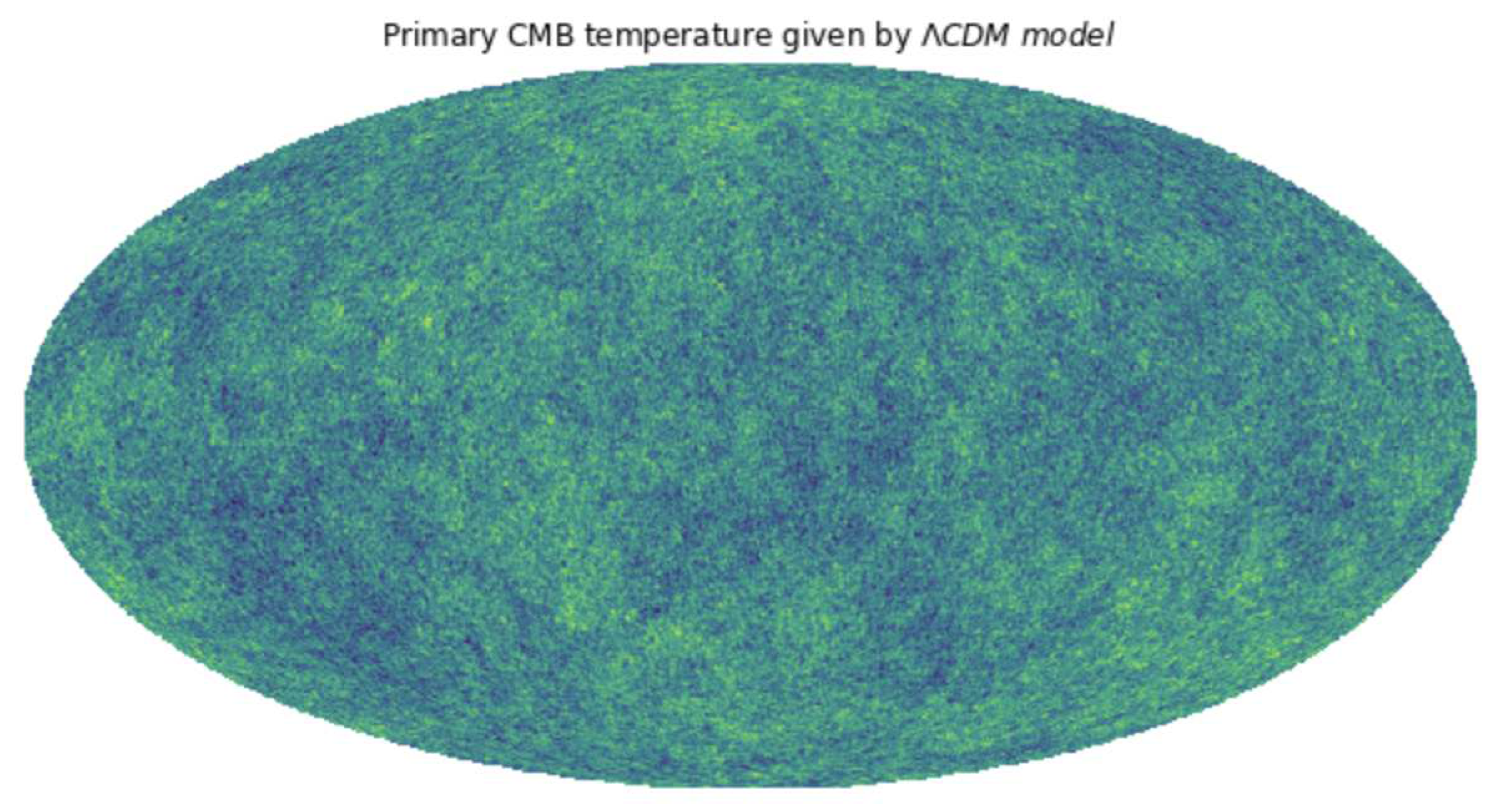

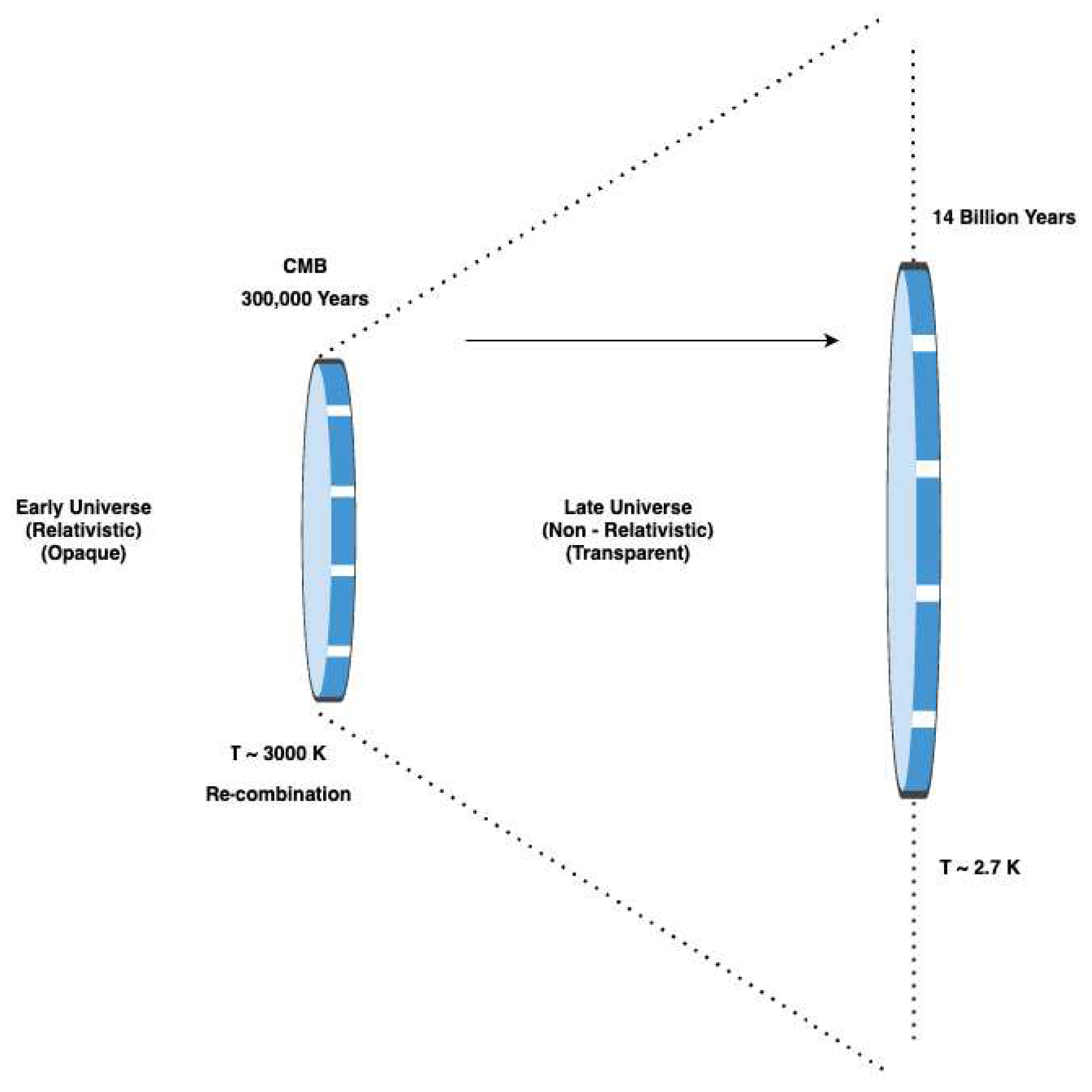

1.2. Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB)

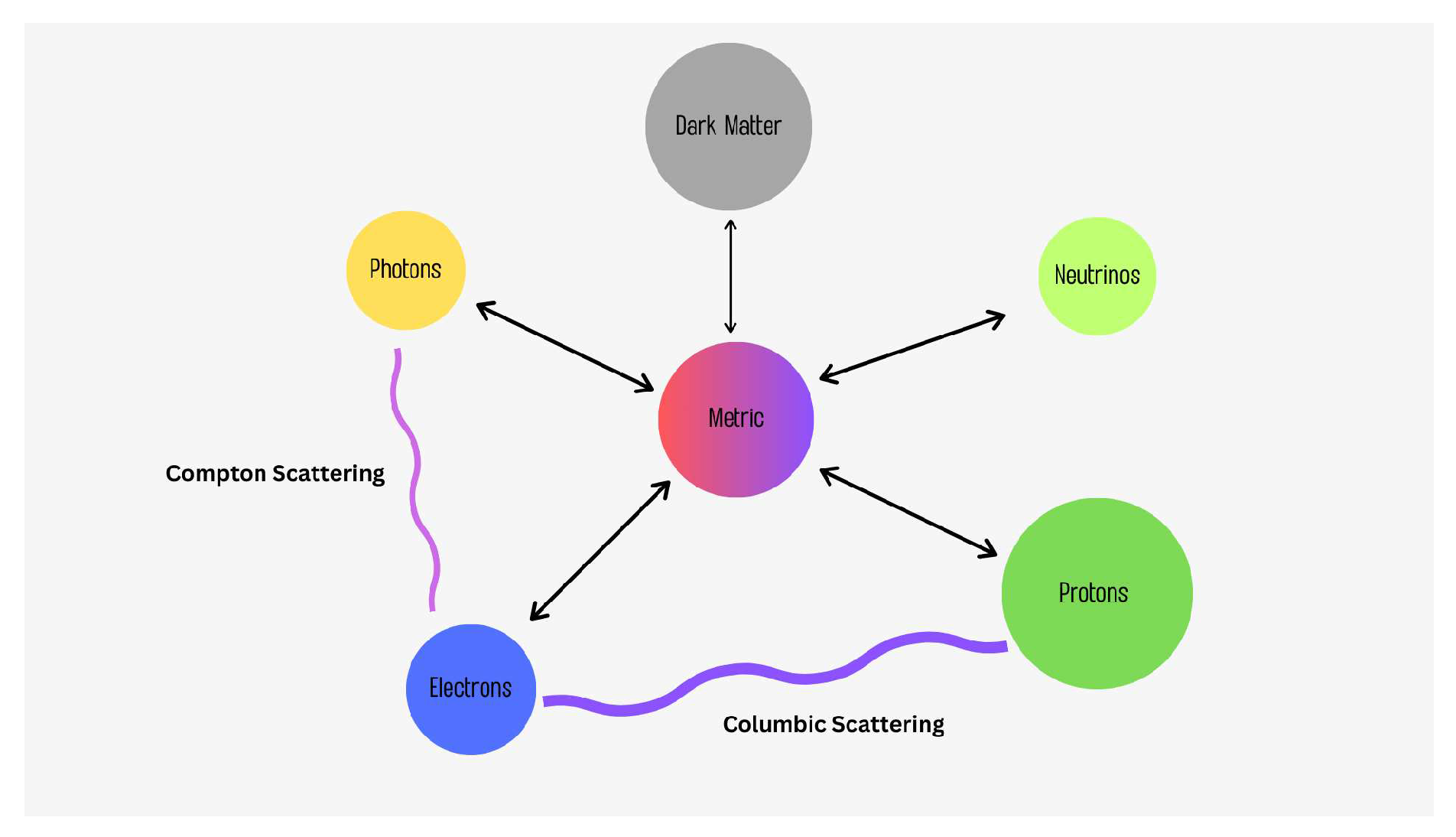

- Baryon-to-photon ratio (): This ratio represents the number density of baryons (subatomic particles like protons and neutrons) relative to the number density of photons. By accurately determining this ratio, we can derive important properties of the photon-baryon fluid, such as the sound speed and inertia. These properties play a significant role in understanding the behavior of the early universe.

- Matter-to-radiation ratio (): This ratio signifies the ratio of the matter density () to the density of radiation (). By determining this ratio, we can gain insights into the abundance of various components in the universe, including dark matter, neutrinos, and other relativistic particles.

- Power Spectrum: The power spectrum is a valuable tool for studying the anisotropies present in the CMB. It provides a detailed analysis of the fluctuations in the CMB temperature across different angular scales ℓ. By examining the power spectrum, researchers can extract information about the underlying structures and perturbations in the early universe. For a more comprehensive discussion on the power spectrum, please refer to Section 1.2.1.

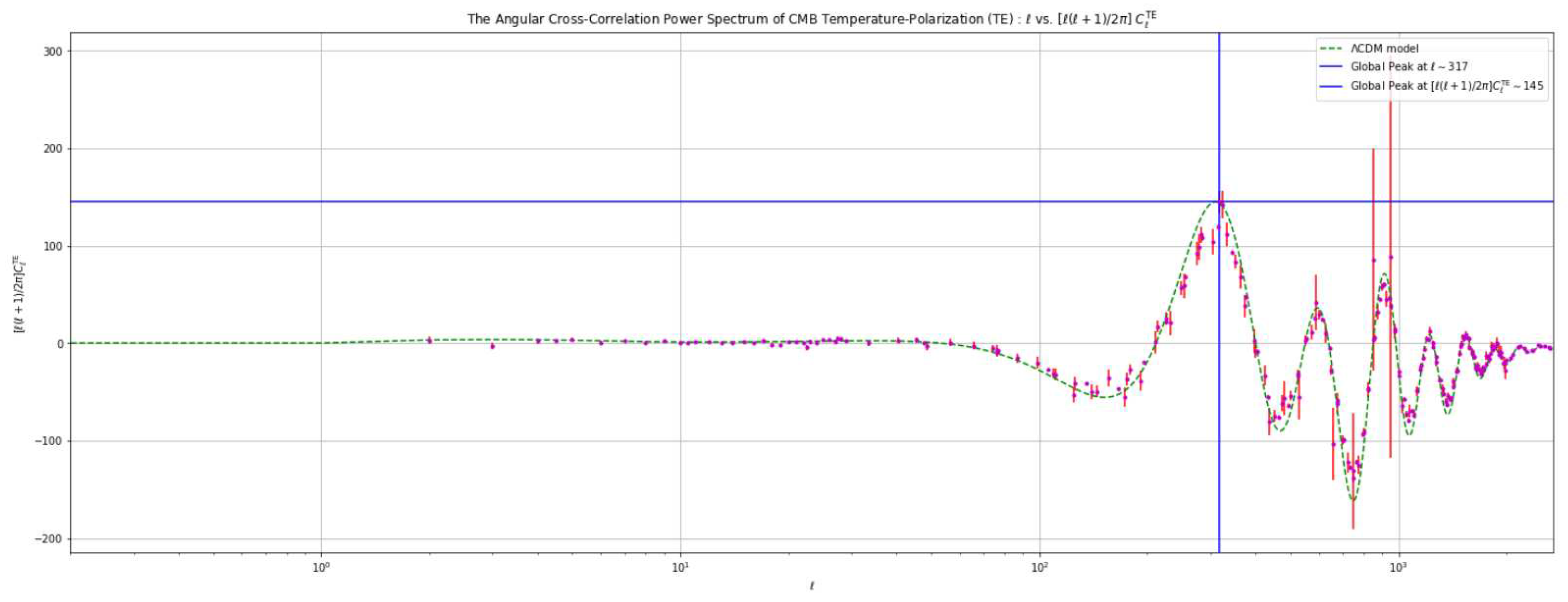

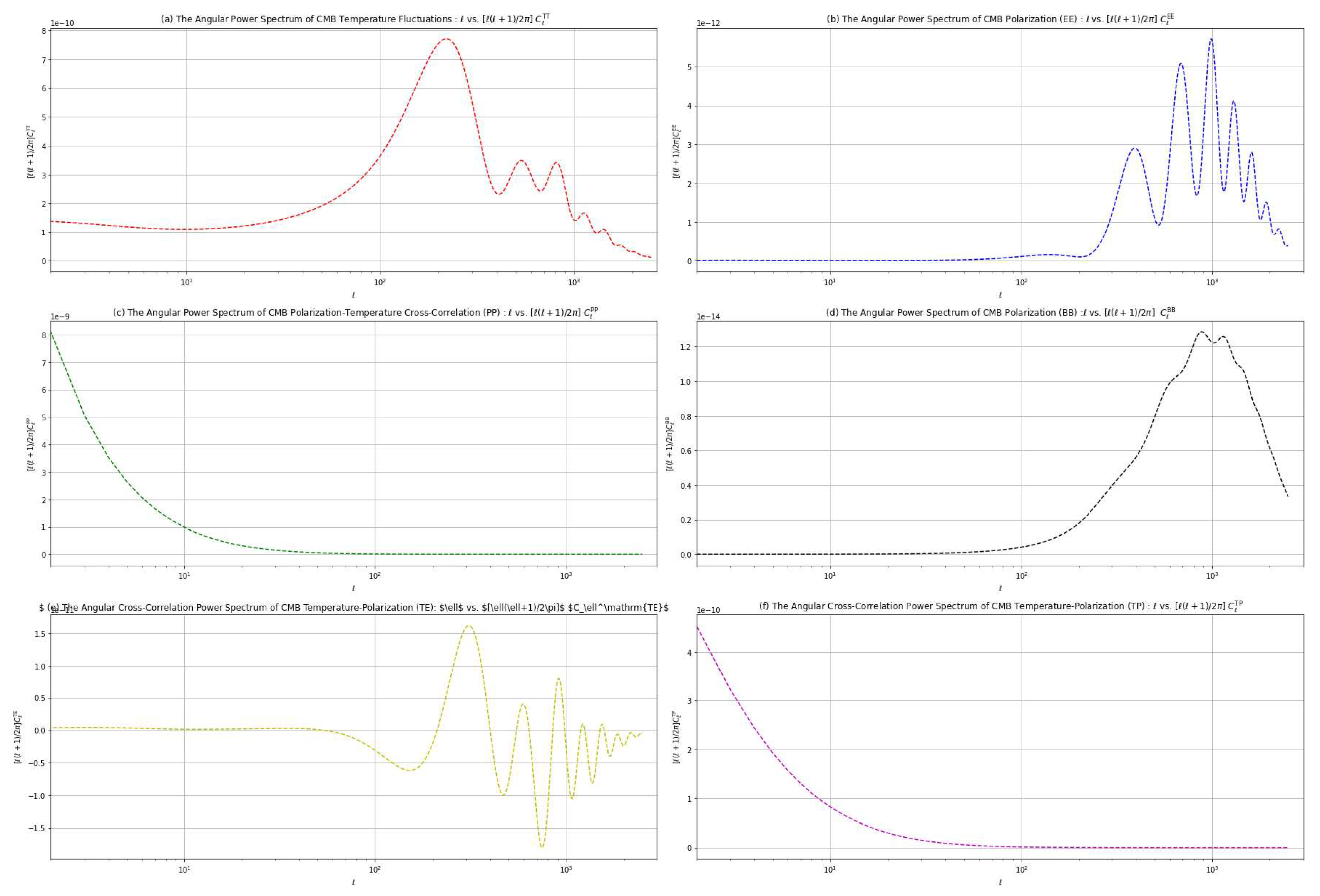

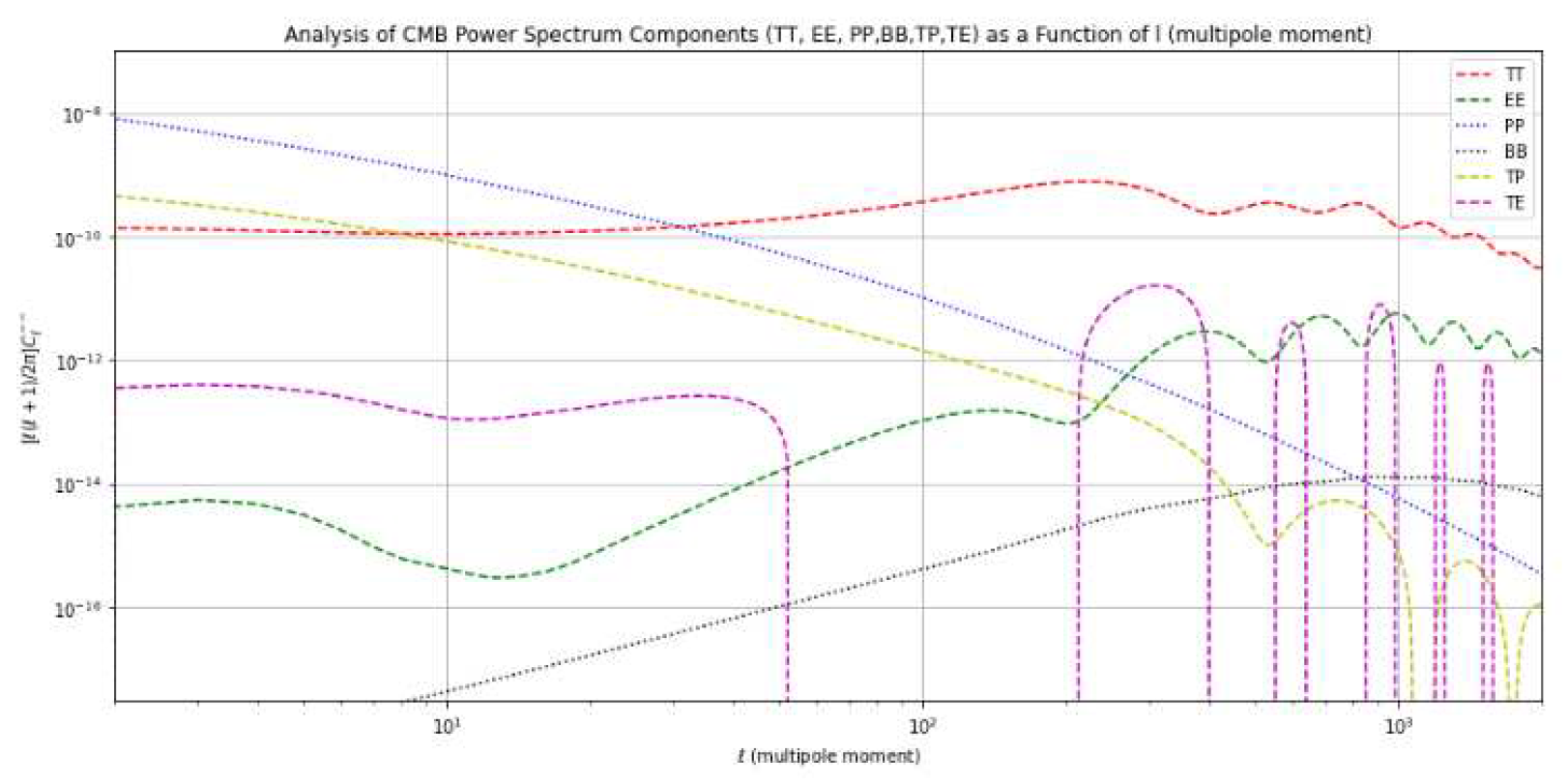

1.2.1. Power Spectrum:

-

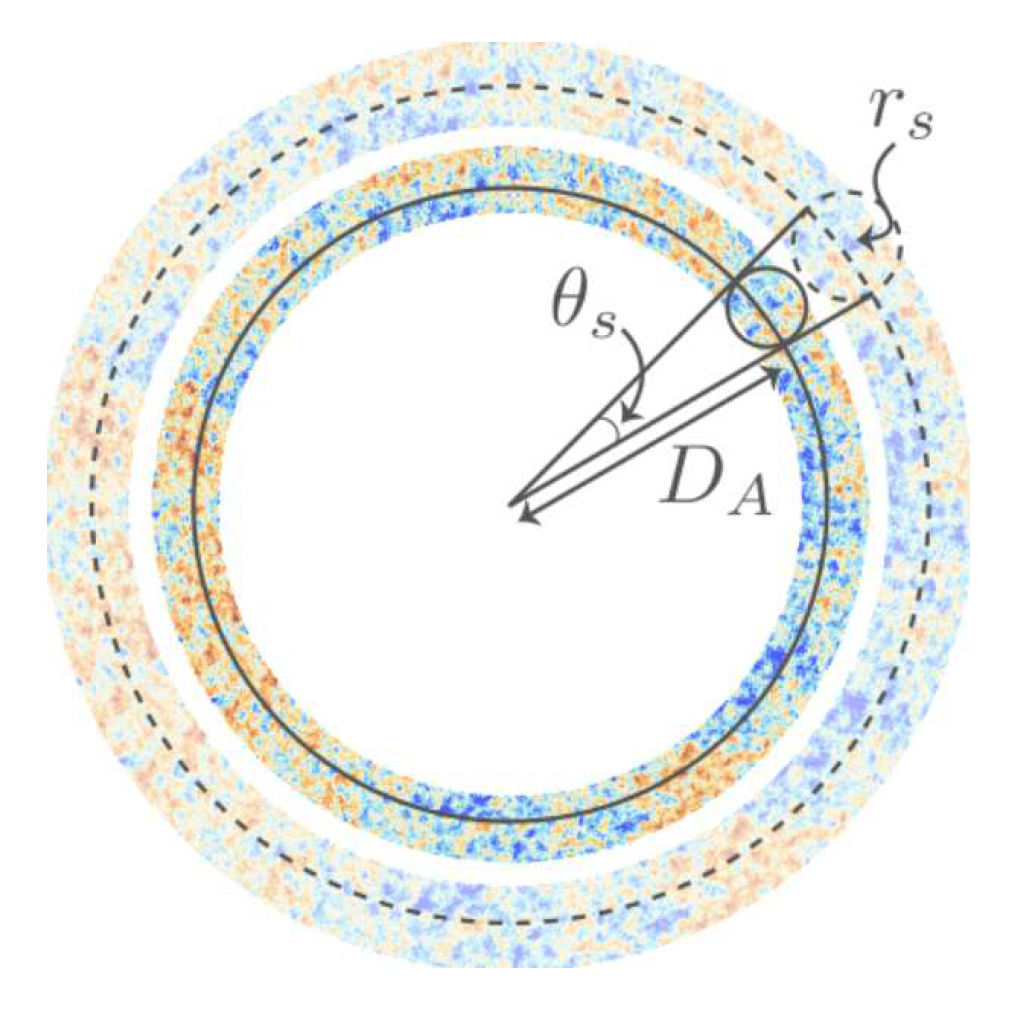

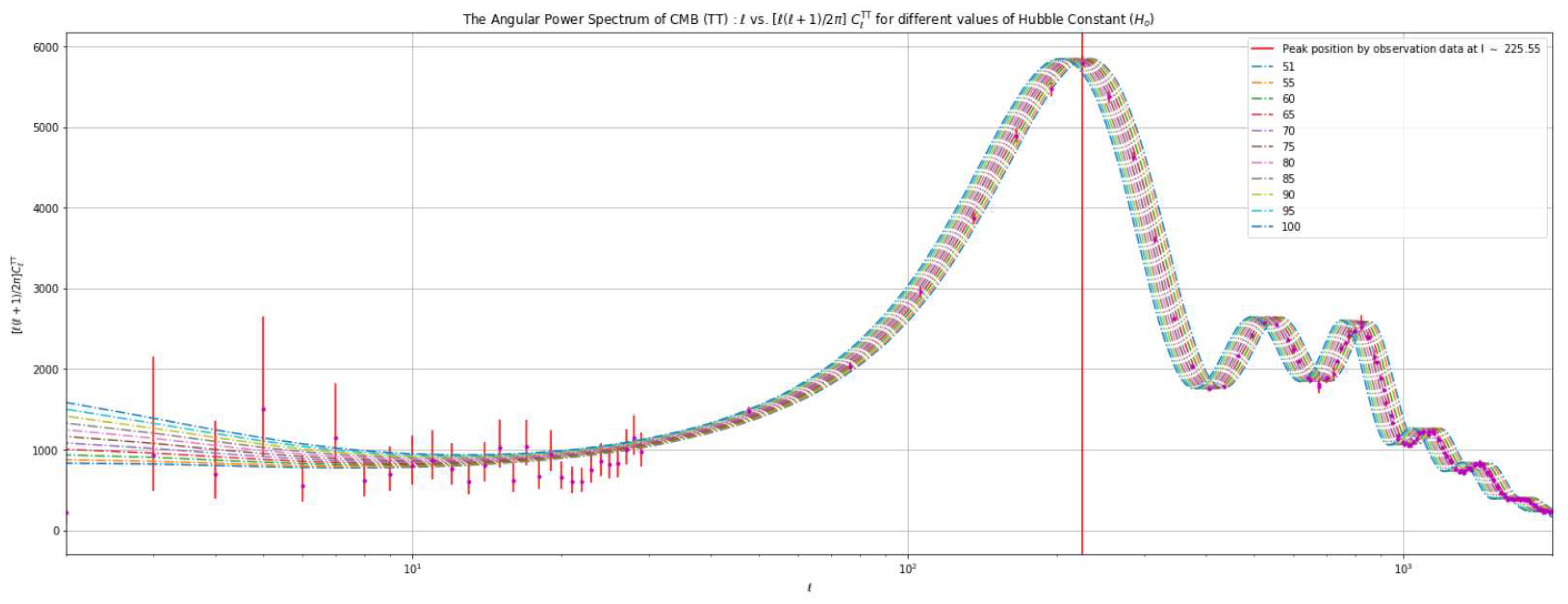

Acoustic Peaks:The cosmic microwave background (CMB) power spectrum exhibits a distinct and characteristic series of peaks and troughs, commonly referred to as acoustic peaks. These peaks arise due to the oscillations present in the photon-baryon fluid (BAO) 2 during the early stages of the universe. These oscillations are a consequence of the delicate balance between the gravitational pull and the pressure forces at play. The interplay of gravity and pressure causes the photon-baryon fluid to undergo rhythmic compression and rarefaction, akin to sound waves propagating through a medium. These acoustic oscillations leave an imprint on the CMB radiation, resulting in the observed pattern of peaks in the power spectrum.Each peak in the power spectrum corresponds to a specific angular scale, reflecting the size of the sound horizon at the time of photon decoupling, marking the moment when photons and baryons became free to propagate independently.The positions and heights of these peaks carry valuable information about the geometry (curvature) of the universe and the density fluctuations present during the era of photon decoupling. By analyzing the properties of the acoustic peaks, cosmologists can glean insights into the curvature of spacetime, the matter and energy content of the universe, and the primordial fluctuations that ultimately gave rise to the large-scale structures we observe today.

-

First Peak:As mentioned earlier, different peaks in the power spectrum of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) convey distinct characteristics and provide valuable insights into the universe.The first peak also referred to as the fundamental or Doppler peak, holds particular significance. It corresponds to the largest angular scale and exhibits the highest amplitude among the peaks. This peak’s position is primarily determined by the density of baryonic matter or ordinary matter in the universe, offering a reference scale for measuring the angular size of the universe.Moreover, the first peak provides insights into the curvature of spacetime. Its location and shape yield valuable clues about the geometry of the universe. By studying the first peak, scientists can discern whether the universe is flat, positively curved (closed), or negatively curved (open), illuminating the overall shape of our universe.

-

Subsequent/ Higher moment Peaks:After the first peak, a series of smaller peaks follow up in the power spectrum. These peaks are the result of higher frequency oscillations of the photon-baryonic fluid and are associated with the harmonics of the fundamental mode.Second Peak: It indicates a substantial amount of baryons (baryon density), which is consistent with inferences drawn from nucleosynthesis3.Third Peak: It reflects the physical density of the dark matter in the cosmos.

-

Damping Tail:In addition to the prominent higher frequency peaks, the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Power spectrum displays a distinctive feature called the damping tail, characterized by a gradual decrease in amplitude. This damping tail phenomenon emerges as a result of the diffusion of photons caused by two key factors: the free-streaming motion of electrons and the finite thickness of the photon-baryonic fluid4.The damping tail’s position contains significant information on the baryon-to-photon ratio as well as the total density of matter in the universe. This understanding helps us to better comprehend the basic cosmological constants by shedding light on the structure and dynamics of the early universe.Table 1. Power Spectrum Characteristics

Characteristic Significance First Peak Baryonic Density, Curvature Second Peak Baryonic Density Third Peak Dark Matter Density Damping Tail Total density of matter, Baryon-to-photon ratio. -

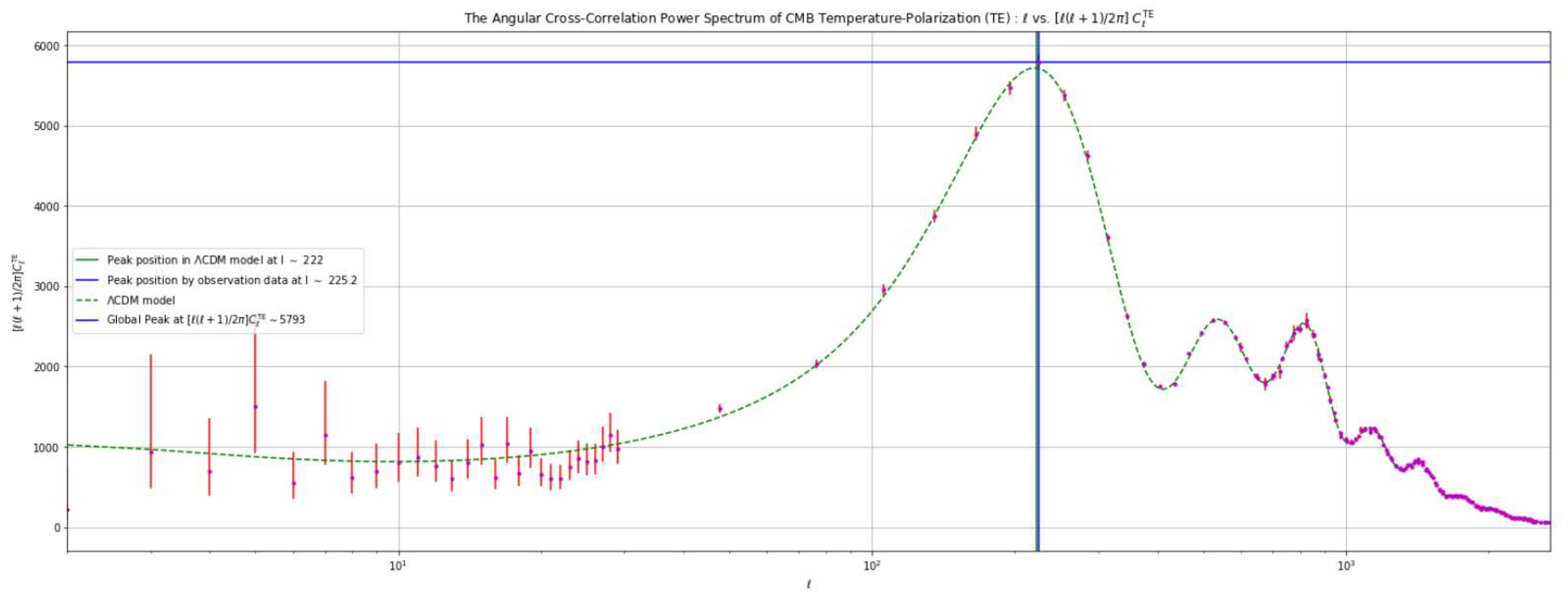

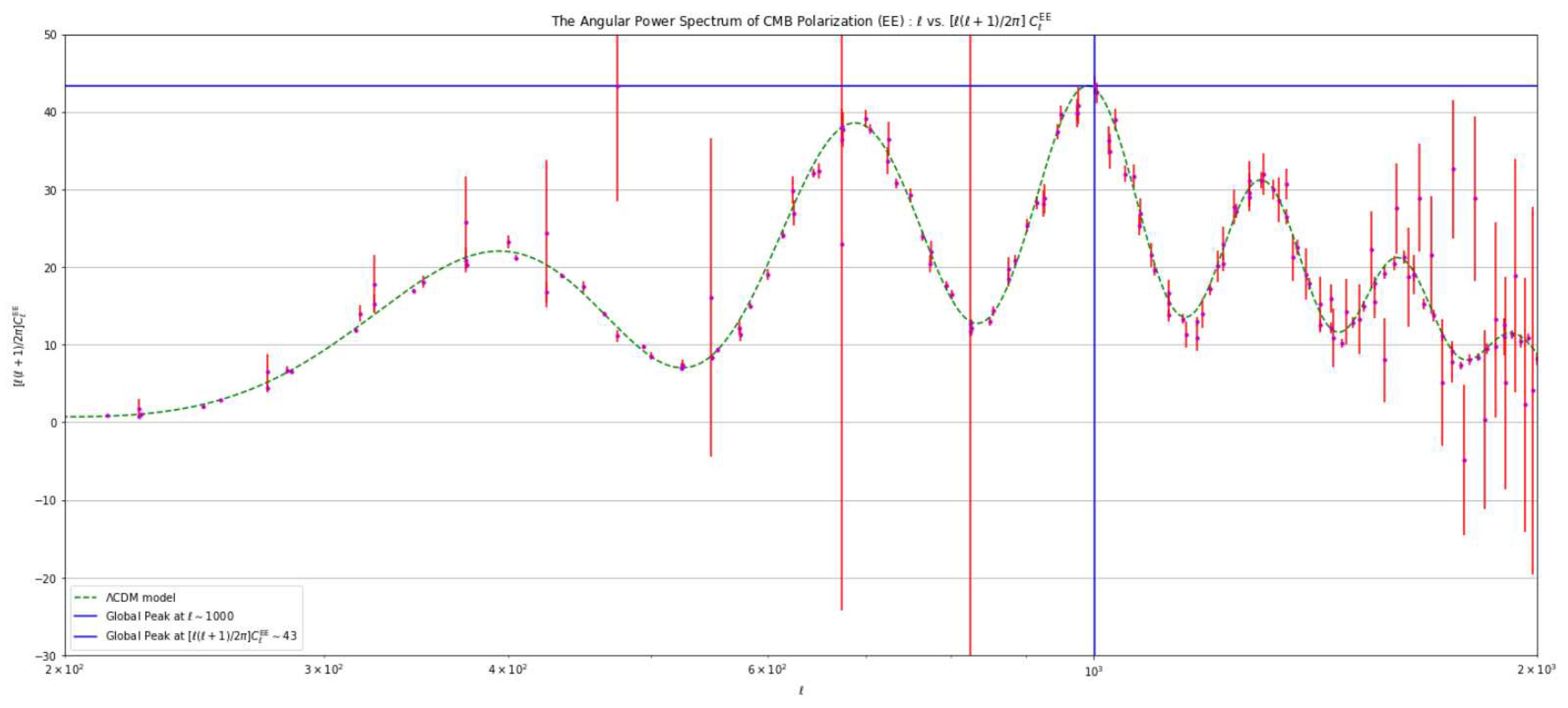

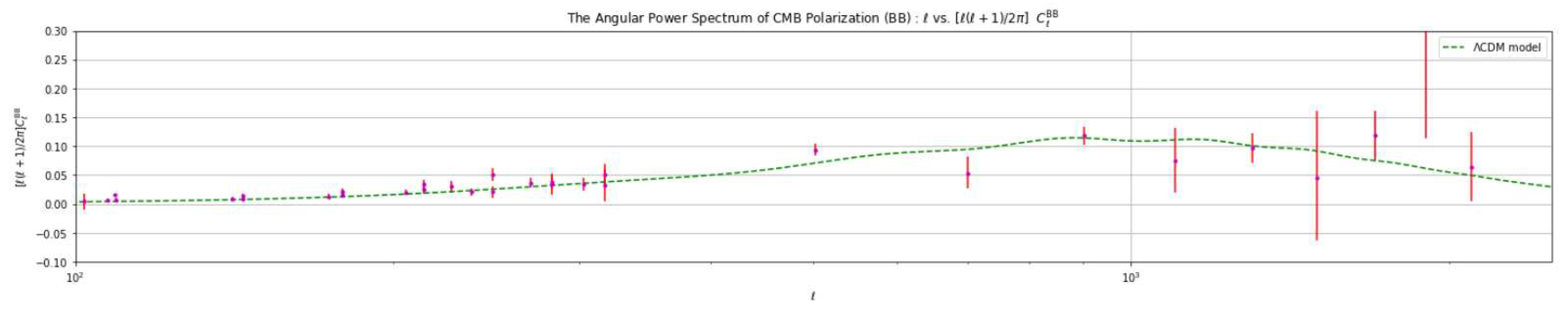

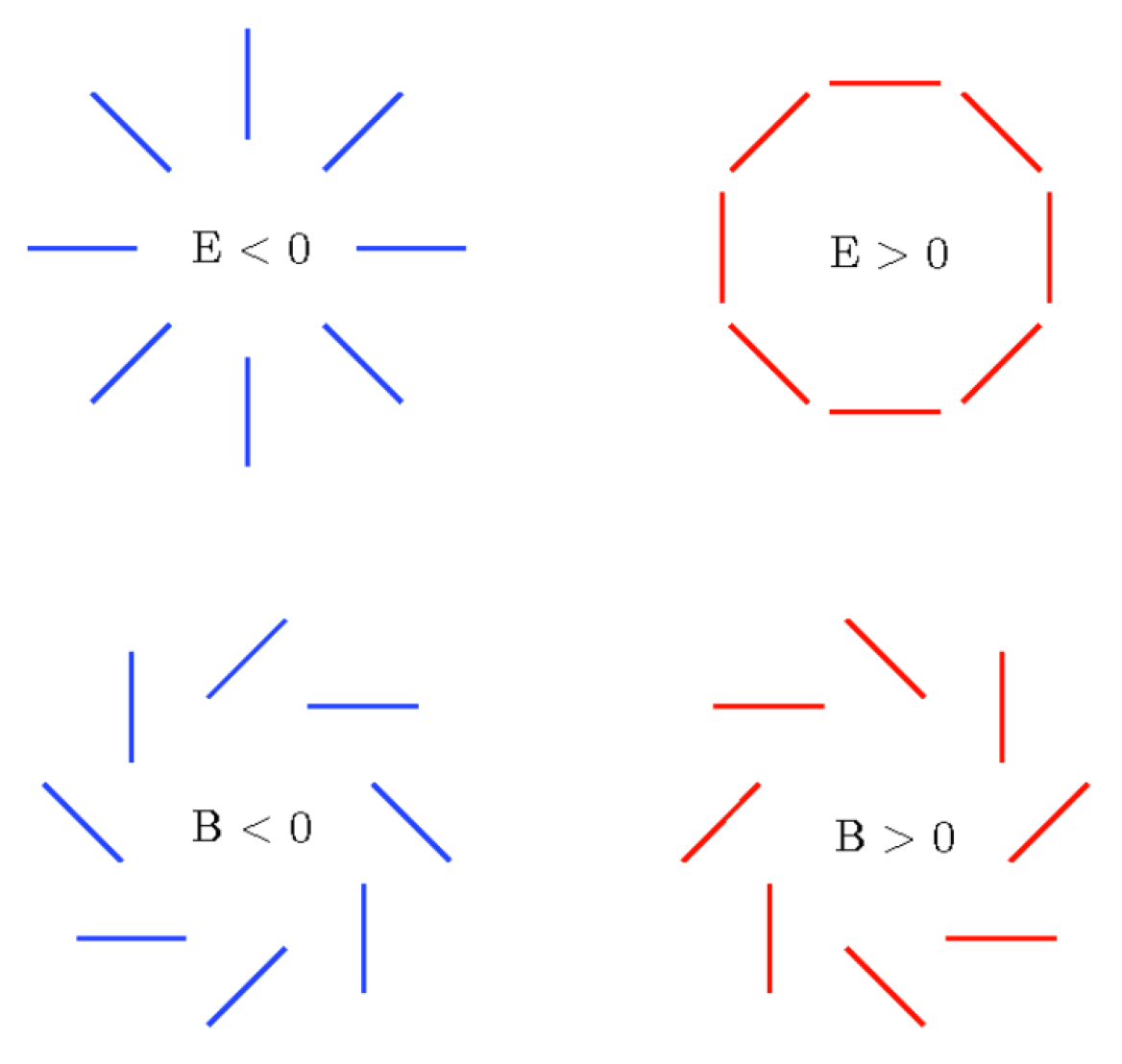

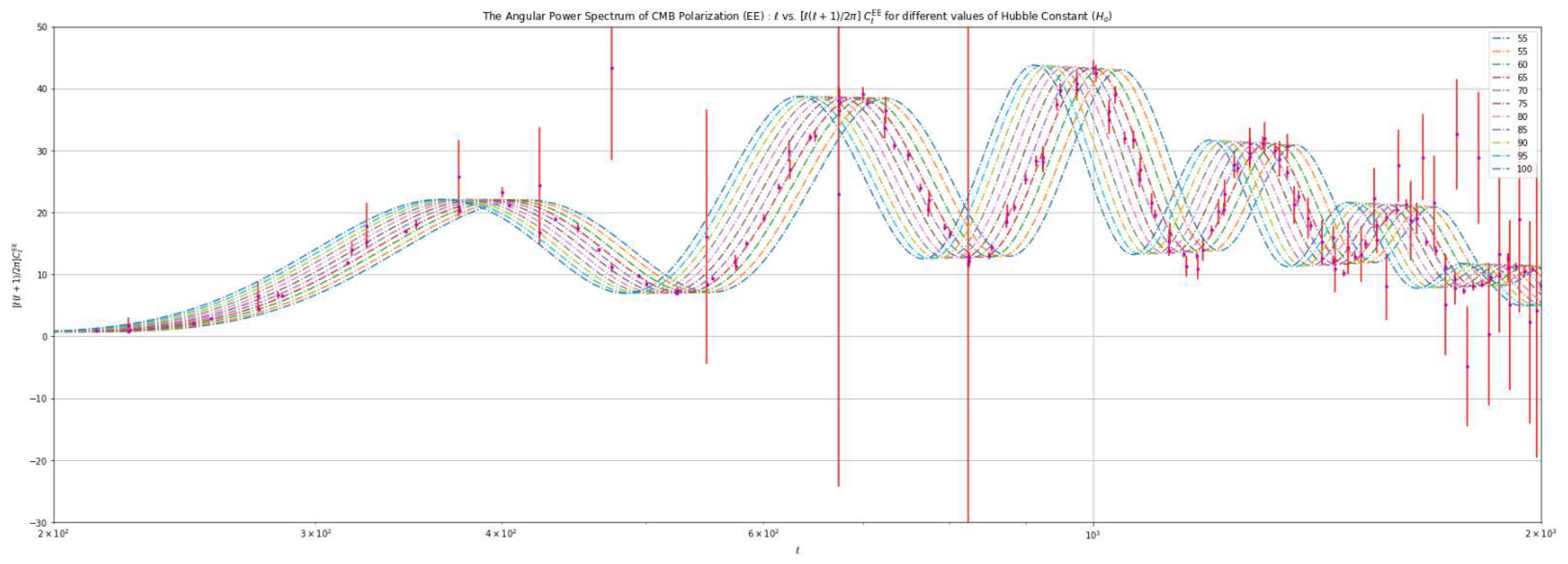

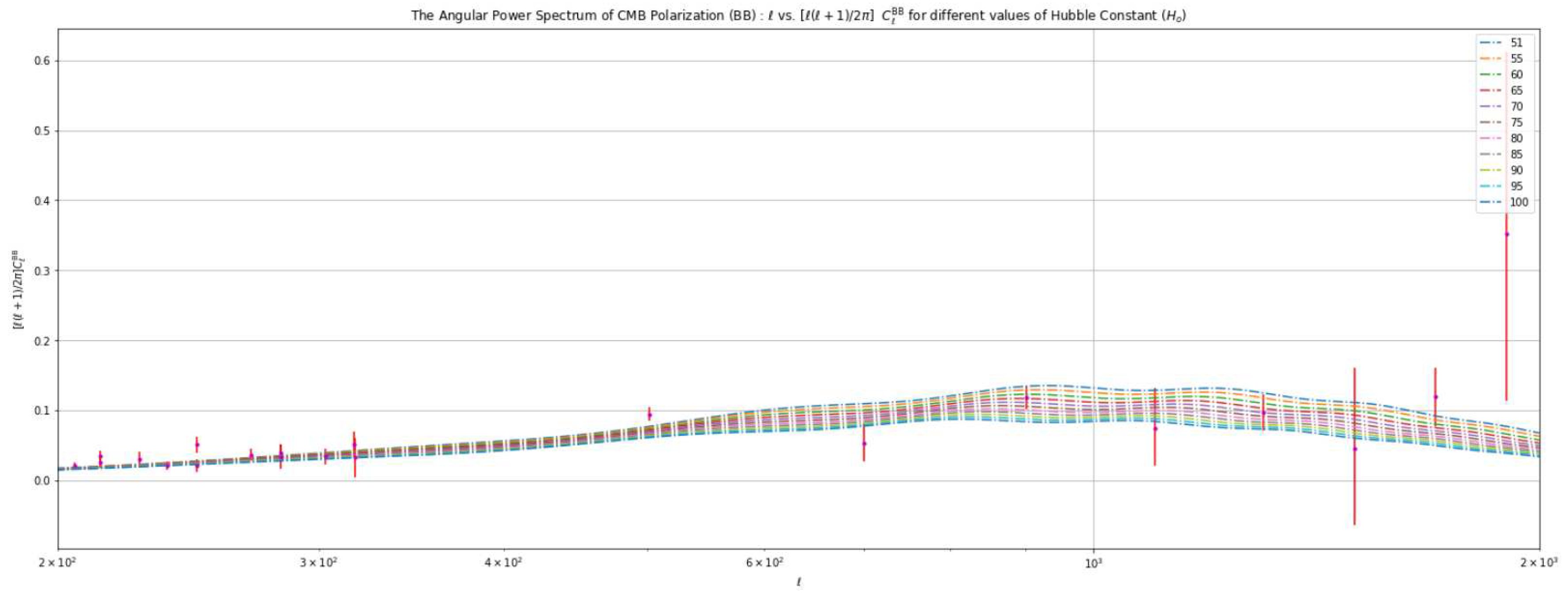

Polarization Spectrum:The polarization patterns observed in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) provide valuable information about the early universe. They reveal details about the re-ionization5 process and density variations during that period. The polarization power spectrum, derived from analyzing the polarization patterns in the CMB, offers insights into the distribution of matter across space. It reveals density variations at different angular scales. There are two primary types of polarization: E-mode and B-mode. E-mode polarization arises from scalar (density) perturbations and represents a curl-free component without any rotation. B-mode polarization, on the other hand, arises from vector perturbations. It is divergence-free, meaning it lacks sources or sinks and does not form closed loops.Both E-mode and B-mode polarization can be produced by tensor perturbations. The observed polarization in the CMB results from a combination of E-mode and B-mode contributions. Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the properties of these modes.

- The odd peaks in this context represent the compression region, while the even peaks represent the rarefaction region. These regions of compression and rarefaction are a result of quantum fluctuations7, which arise from the interplay between the forces of photon pressure and baryon gravitational pull.

- All of the peaks positions and amplitude are affected by multiple parameters.

- When baryons are added to the plasma, the oscillations’ frequency is reduced, which causes the peaks to move to somewhat higher multipoles (ℓ).

- The total peak amplitude is diminished when the dark matter density is increased.

- Reducing the density of dark matter eliminates the baryons loading8 effect, which results in enhanced compression over rarefaction regions.

- Raising the baryon density shifts the damping tail to higher multipoles.

- Raising the matter density (baryonic matter and non-baryonic matter) ships the damping tail to lower multipoles.

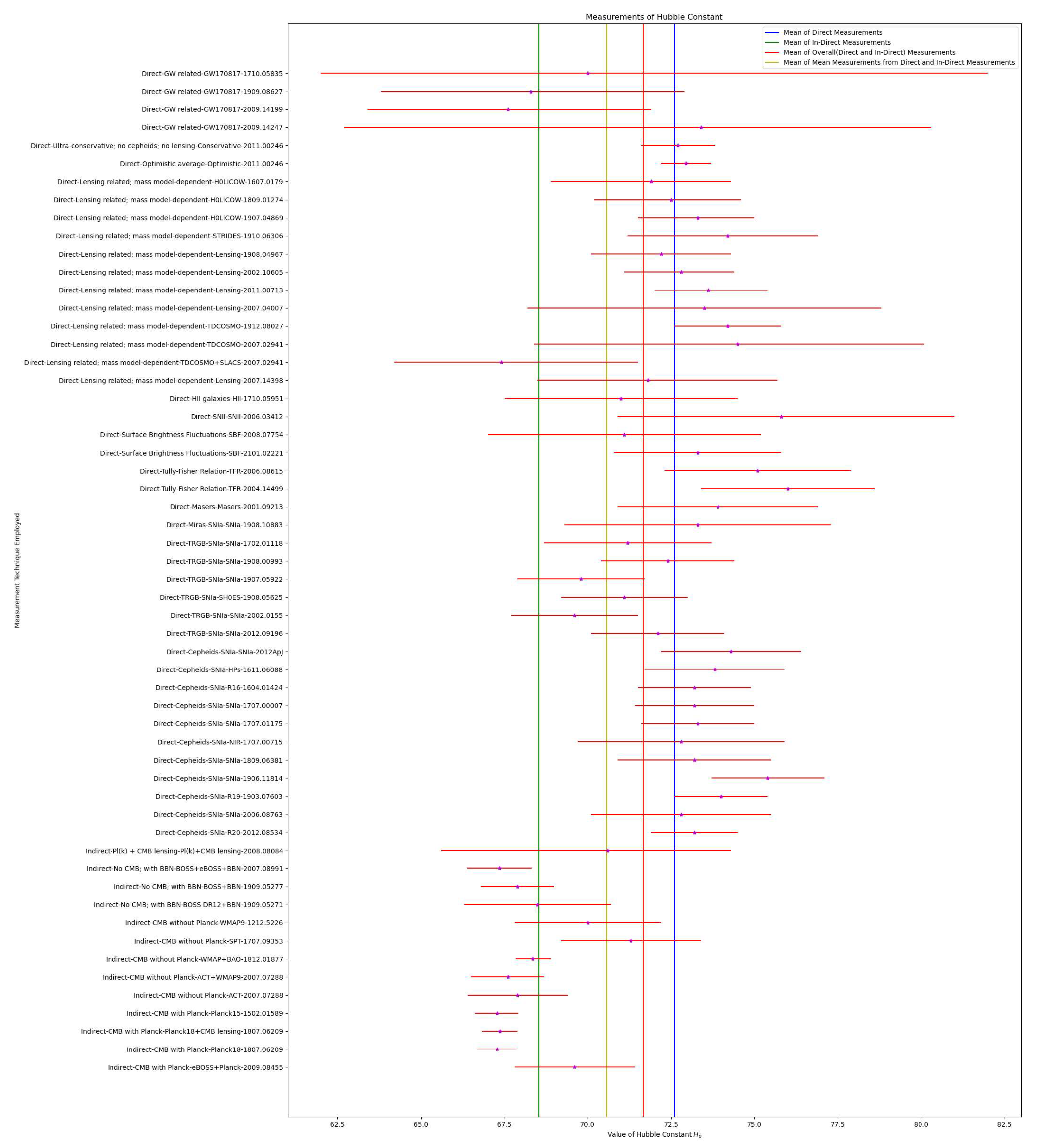

1.3. Hubble Tension

1.4. Perturbation Theory

| Perturbation Type | Significance |

| Scalar | Fluctuations in matter or energy density |

| Vector | Fluctuations in vector fields |

| Tensor | Fluctuations in the gravitational field |

1.5. Sound Horizon ()

2. Literature Review

-

Keeping fixed which means keeping CMB peaks fixed such that .Now following up on this idea we can do some mathematical manipulation to get the crucks of the given statement. Let us make use of the information given in section[1.5], we takeAlso, we know thatwhich states,Here, we find that for constant ;This implies that as the Hubble constant increases, the sound horizon decreases, and vice versa.Hence by keeping the sound horizon fixed while varying the Hubble constant, we can study the impact of different Hubble constant values on the properties of the CMB peaks. This analysis allows us to explore the effects of changes in the expansion rate of the Universe on the observed characteristics of the CMB radiation.

-

Decrease , which increase the pre-CMB expansion rate.The physical interpretation of the equationstates as the pre-CMB expansion rate is inversely proportional to the sound horizon that means to increase the pre-CMB expansion rate we have to consequently decrease the sound horizon , which results in shifting characteristics of the CMB peaks in the power spectrum.

- Leave unchanged, so modification must disappear at late times. The physical meaning of the equationmeans that the angular diameter distance () remains inversely proportional to the post-CMB expansion rate () while the modification disappears at late times.

-

Recombination shifted by primordial magnetic field:The concept proposes the intriguing notion of small-scale, mildly non-linear inhomogeneities in the baryon density during the process of recombination, influenced by primordial magnetic fields (Schöneberg et al., 2022 [14]; Jedamzik & Saveliev, 2019 [15]). If these magnetic fields exist, they have the potential to alter the dynamics of charged particles during recombination, consequently leaving observable imprints on the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. Although these small-scale inhomogeneities do not directly contribute to CMB temperature and polarization anisotropies, they significantly impact the CMB anisotropy spectra by modifying the ionization history of the Universe. Specifically, the recombination rate is directly proportional to the square of the electron density (). Therefore, the presence of an inhomogeneous plasma can induce modifications in the mean free electron fraction at a given epoch. This, in turn, leads to an earlier recombination of the clumpy plasma, resulting in a reduction of the sound horizon () at the time of recombination. Consequently, the CMB spectra display a noticeable shift in the positions of the peaks. This shift can be compensated by considering a larger value of the Hubble constant () (Jedamzik & Pogosian, 2021)[16]. Exploring the implications of these inhomogeneities driven by primordial magnetic fields adds another layer of complexity to our understanding of the recombination process and its impact on the CMB radiation.

- Recombination shifted by varying effective electron mass: This hypothesis postulates that variations in the effective mass of electrons may have an impact on the recombination process. The period of recombination in the early Universe can be altered in one of the most efficient ways through this (Schöneberg et al., 2022 [14]; Sekiguchi & Takahashi, 2021 [17]; J.-P. Uzan, 2003 [18]).

- Recombination shifted by varying effective electron mass in a curved universe: This model extends the previous theory that considers variations in electron mass during recombination by incorporating an additional parameter () to account for the effects of a curved or non-flat universe (Sekiguchi & Takahashi, 2021 [17]). By investigating the combined influence of spatial curvature and variations in electron mass, researchers aim to gain a deeper understanding of how these variables impact the recombination process and its observable manifestations. The inclusion of the curvature parameter () allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the recombination epoch within the context of a curved universe. By considering the spatial curvature alongside the variations in electron mass, researchers can explore how these combined factors shape the dynamics of recombination and its detectable signatures.

-

Self-interacting neutrinos plus free-streaming Dark Radiation: In this scenario, the behavior of neutrinos, which are weakly interacting (Park et al., 2019)[19] particles, is considered alongside the presence of free-streaming Dark Radiation. The large neutrino masses accommodate for larger values of (Ghosh et al., 2020)[20]. Neutrinos, being self-interacting, can affect the large-scale structure formation of the universe. (Archidiacono & Gariazzo, 2022)[21] has showcased the interaction between sterile neutrinos and dark radiation and given some account for hubble tension.In this model researchers explore the behavior of neutrinos, which are weakly interacting particles (Park et al., 2019)[19], in conjunction with the presence of free-streaming Dark Radiation. The consideration of large neutrino masses accommodates for larger values of (Ghosh et al., 2020)[20]. Neutrinos, despite their weak interactions, have a significant impact on the dynamics of the universe, especially at large scales. The consideration of sterile neutrinos, which do not participate in weak interactions, introduces an additional element that can influence the behavior of neutrinos and contribute to resolving the Hubble tension as demonstrated by Archidiacono & Gariazzo (2022)[21].

3. Methodology

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. CDM Model Analysis

| Power Spectrum Component Type | Perturbation Associated |

| TT | Scalar |

| EE | Scalar |

| PP | Tensor |

| BB | Tensor |

| TE | Scalar |

| TP | Scalar |

4.2. CDM Model Vs Real Observation Measurements Analysis

- The amplitude of each peak in the actual measured values is lower compared to the expected values predicted by the CDM model. Specifically, for the first peak, the difference amounts to approximately 2000 units.

- In the low ℓ region, the data points exhibit significantly higher levels of erroneous values compared to other data points along the ℓ spectrum. Additionally, these data points do not align with the expected trace of the CDM model, a discrepancy that persists across the entire curve.

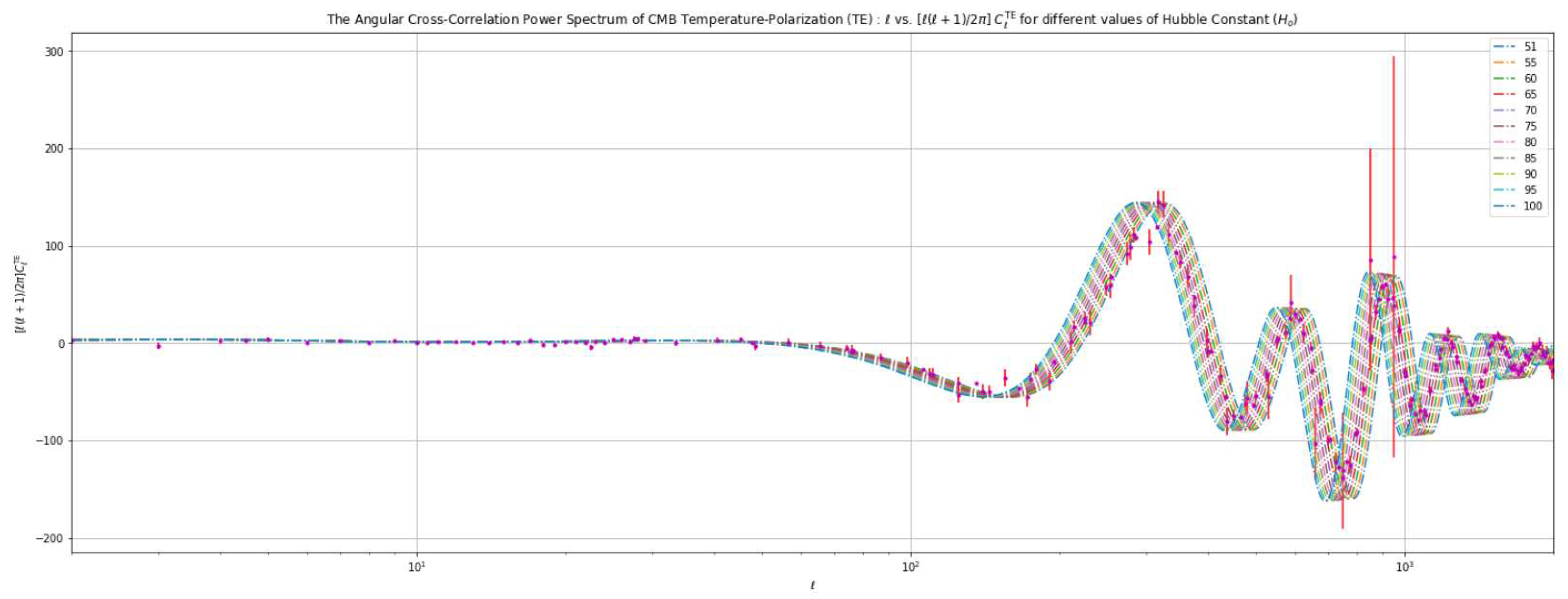

4.3. Analysis Based on Varying the Value of the Hubble Constant ()

4.4. Real Data Measurements via MCMC Technique

-

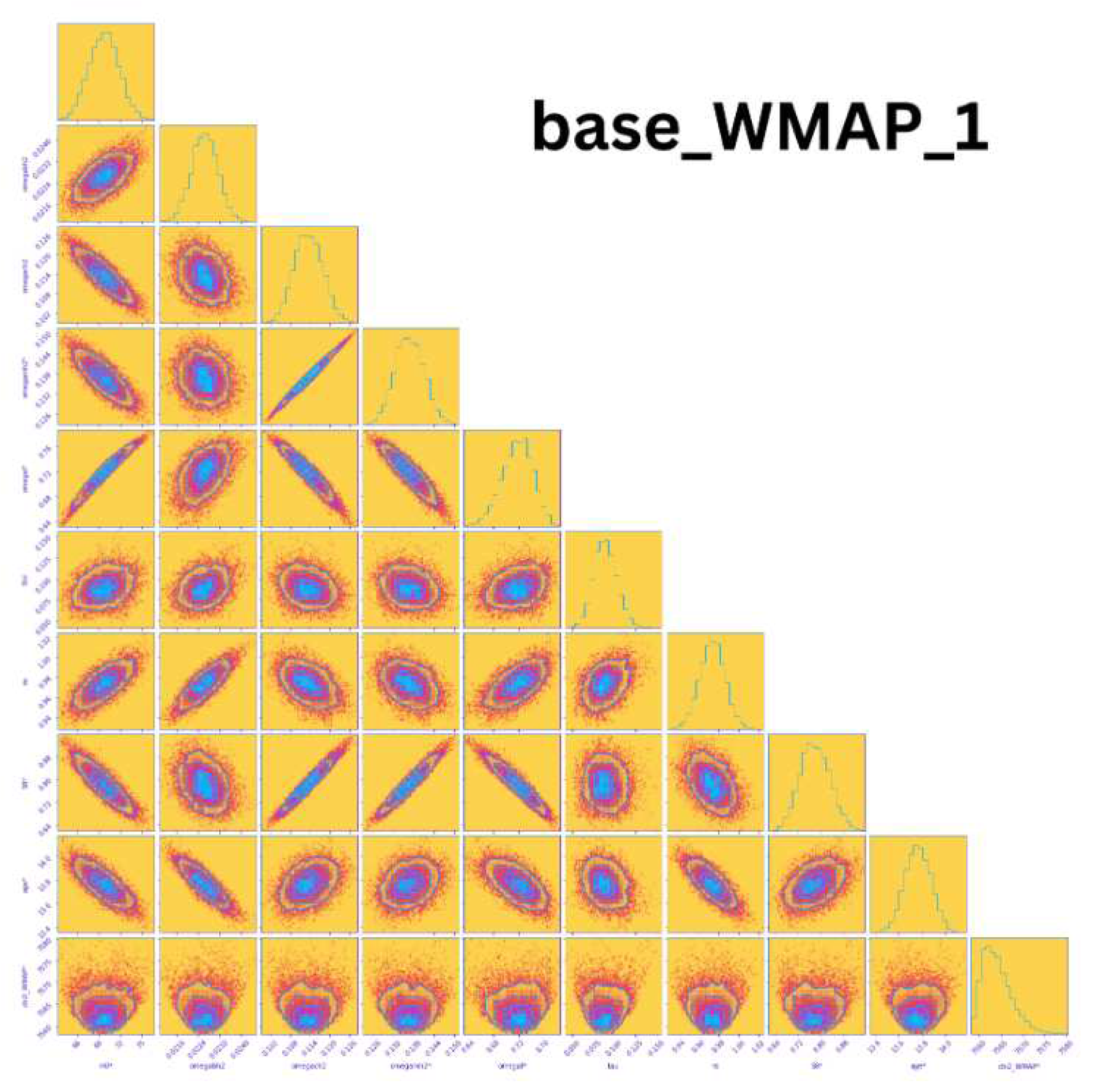

Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP)WMAP was a significant survey mission launched in 2001 and operated until 2010. It was positioned in the L2 orbit to minimize exposure to solar radiation. The primary objective of WMAP was to analyze temperature fluctuations in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). Figure 18 showcases a corner plot displaying ten parameters (, , , , , , , , , ) measured by the WMAP probe, highlighting their correlations. The first column of the plot reveals variations in the Hubble constnat with variations in other cosmological parameters. Notably, these measurements have a value of zero. Furthermore, the value of amounts to 0.000645.

-

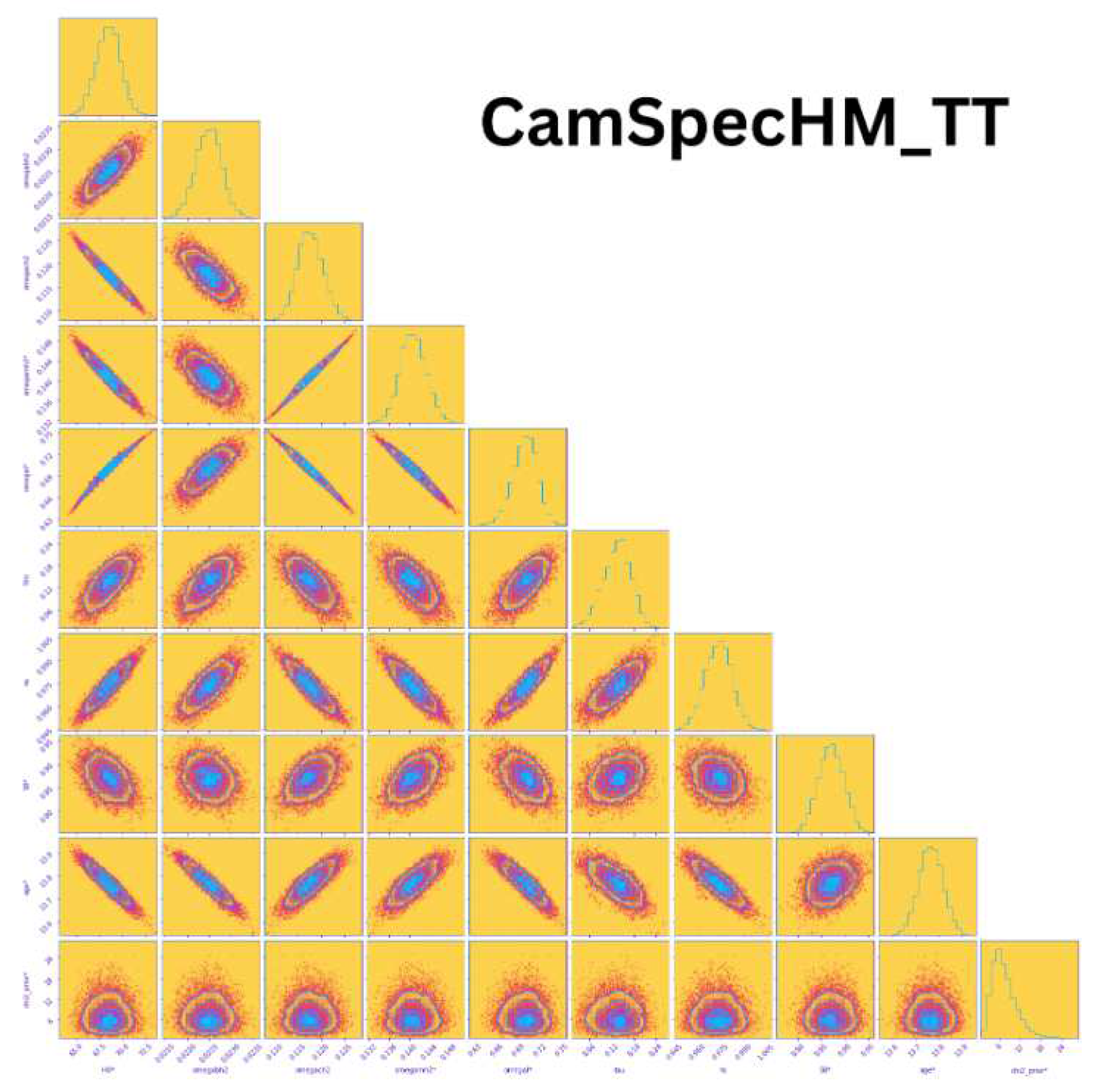

Planck Large Scale Survey MissionThe Planck survey mission, which commenced in 2009 and operated until 2013, was another significant endeavor in the field of cosmology. Similar to WMAP, Planck was also positioned in the L2 orbit around Earth. This satellite leveraged the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) to obtain measurements of great importance. The corner plot depicted in Figure 19 showcases ten parameters (, , , , , , , , , ) measured by the Planck mission. In particular, the first column of the plot allows us to assess the correlation between the Hubble constant and various cosmological parameters. This analysis provides valuable insights into the relationship between the Hubble constant and other fundamental aspects of the universe. Moreover, the value of is found to be 0.000645.

-

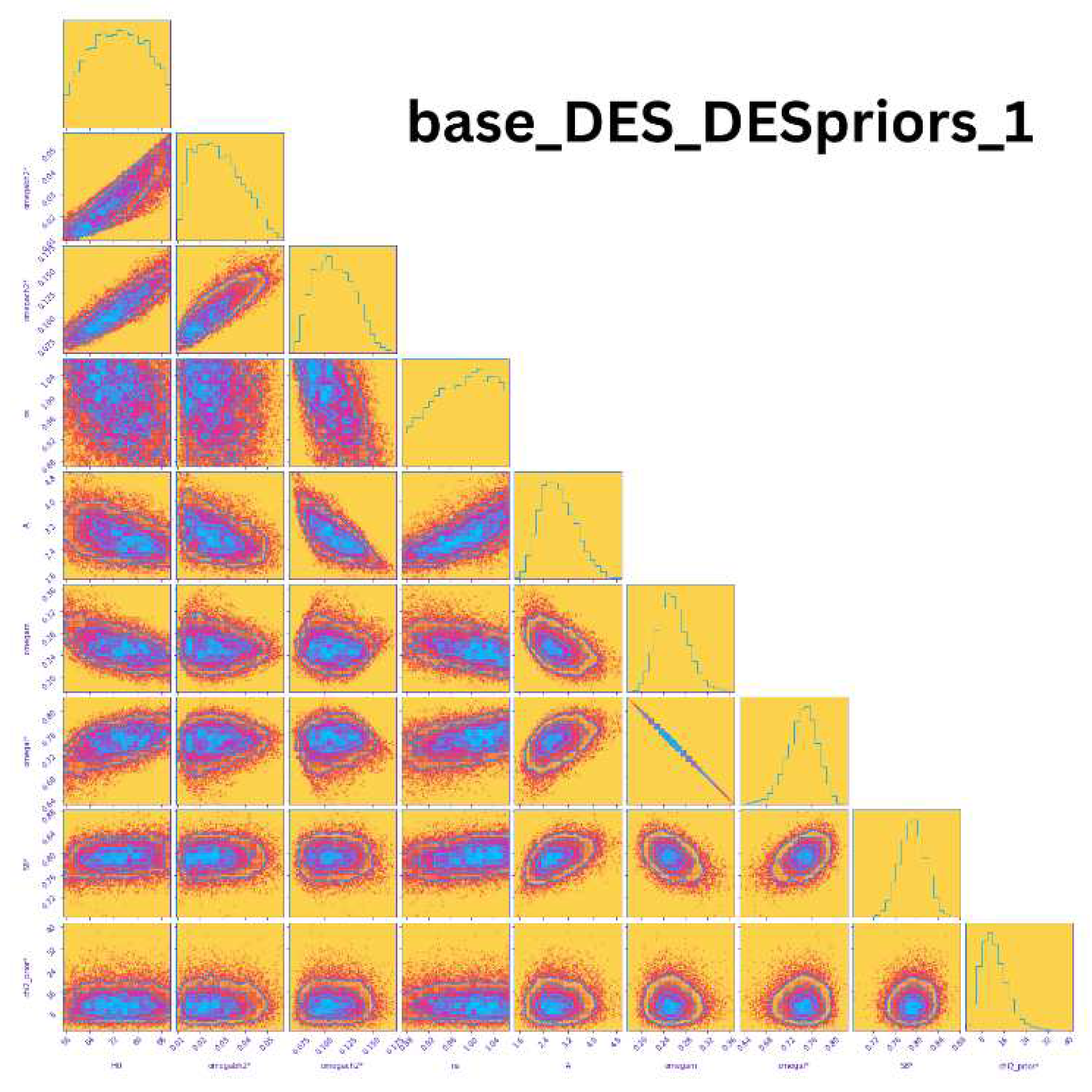

Dark Energy Survey (DES)The DES (Dark Energy Survey) mission was launched in 2013 and successfully operated until 2019. This survey primarily utilized measurements from Type Ia supernovae and baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) to capture data from the late universe. The results obtained from DES are presented in Figure 20, which highlights the nine parameters (, , , , A, , , , ) that were measured made by the DES mission. In this figure, the uncertainties in the measurements are more pronounced, providing valuable insights into the precision of the data. Specifically, the first column of the plot illustrates variations in the value of the Hubble constant in relation to other cosmological parameters. This analysis offers a comprehensive understanding of how the Hubble constant interacts with various aspects of the universe. Additionally, the value of is found to be 0.000645.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Riess, Adam G., et al. "Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid standards provide a 1% foundation for the determination of the Hubble constant and stronger evidence for physics beyond ΛCDM." The Astrophysical Journal 876.1 (2019): 85.

- Riess, Adam G., et al. "A comprehensive measurement of the local value of the Hubble constant with 1 kms-1mpc-1 uncertainty from the Hubble space telescope and the sh0es team." The Astrophysical Journal Letters 934.1 (2022): L7.

- Migkas, K., et al. "Cosmological implications of the anisotropy of ten galaxy cluster scaling relations." Astronomy & Astrophysics 649 (2021): A151.

- Wong, Kenneth C., et al. "H0LiCOW–XIII. A 2.4 per cent measurement of H 0 from lensed quasars: 5.3 σ tension between early-and late-Universe probes." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 498.1 (2020): 1420-1439.

- Millon, M., et al. "TDCOSMO-I. An exploration of systematic uncertainties in the inference of H0 from time-delay cosmography." Astronomy & Astrophysics 639 (2020): A101.

- Reid, M. J., et al. "The megamaser cosmology project. IV. A direct measurement of the Hubble constant from UGC 3789." The Astrophysical Journal 767.2 (2013): 154.

- Kuo, C. Y., et al. "The megamaser cosmology project. V. An angular-diameter distance to NGC 6264 at 140 Mpc." The Astrophysical Journal 767.2 (2013): 155.

- Mooley, K. P., et al. "Superluminal motion of a relativistic jet in the neutron-star merger GW170817." Nature 561.7723 (2018): 355-359.

- DLT40 Collaboration Haislip JB 241 Kouprianov VV 241 Reichart DE 241 Tartaglia L. 242 243 Sand DJ 242 Valenti S. 243 Yang S. 243 244 245, and Las Cumbres Observatory Collaboration Arcavi Iair 246 247 Hosseinzadeh Griffin 246 247 Howell D. Andrew 246 247 McCully Curtis 246 247 Poznanski Dovi 248 Vasylyev Sergiy 246 247. "A gravitational-wave standard siren measurement of the Hubble constant." Nature 551.7678 (2017): 85-88.

- Benisty, David, and Denitsa Staicova. "Testing late-time cosmic acceleration with uncorrelated baryon acoustic oscillation dataset." Astronomy & Astrophysics 647 (2021): A38.

- Addison, G. E., et al. "Elucidating Λ CDM: impact of baryon acoustic oscillation measurements on the Hubble constant discrepancy." The Astrophysical Journal 853.2 (2018): 119.

- Poulin, V., Smith, T. L., Karwal, T., & Kamionkowski, M. (2019). Early dark energy can resolve the hubble tension. Physical Review Letters, 122(22), 221301. 22. [CrossRef]

- Niedermann, F., & Sloth, M. S. (2022). Hot new early dark energy: Towards a unified dark sector of neutrinos, dark energy and dark matter. Physics Letters B, 835, 137555. [CrossRef]

- Schöneberg, N., Abellán, G. F., Sánchez, A. P., Witte, S. J., Poulin, V., & Lesgourgues, J. (2022). The H 0 Olympics: A fair ranking of proposed models. Physics Reports, 984, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Jedamzik, K., & Saveliev, A. (2019). Stringent limit on primordial magnetic fields from the cosmic microwave background radiation. Physical Review Letters, 123(2), 021301. 2. [CrossRef]

- Jedamzik, K., Pogosian, L. & Zhao, GB. Why reducing the cosmic sound horizon alone can not fully resolve the Hubble tension. Commun Phys 4, 123 (2021). [CrossRef]

- T. Sekiguchi and T. Takahashi, “Early recombination as a solution to the H0 tension,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 103, no. 8, p. 083507, 2021.

- J.-P. Uzan, “The Fundamental Constants and Their Variation: Observational Status and Theoretical Motivations,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 75, p. 403, 2003.

- M. Park, C. D. Kreisch, J. Dunkley, B. Hadzhiyska, and F.-Y. Cyr-Racine, “ΛCDM or self-interacting neutrinos: How CMB data can tell the two models apart,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 100, no. 6, p. 063524, 2019.

- S. Ghosh, R. Khatri, and T. S. Roy, “Can dark neutrino interactions phase out the Hubble tension?,” Physical Review D, vol. 102, p. 123544, Dec. 2020.

- Archidiacono, M., & Gariazzo, S. (2022). Two sides of the same coin: Sterile neutrinos and dark radiation. Status and perspectives. Universe, 8(3), 175. [CrossRef]

| 1 | Recombination refers to the period when ions cooled down sufficiently to combine, forming neutral hydrogen atoms. |

| 2 | Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAO): These are the imprints of primordial acoustic waves that were frozen in the early universe’s density distribution. The characteristic scale of BAO is extracted via Fourier analysis. It serves as a standard ruler for measuring the history of the universe’s expansion and prohibiting dark energy. |

| 3 | Nucleosynthesis is the process by which light elements were formed in the early universe, and its predictions align with the observed abundance of certain elements, such as hydrogen and helium. |

| 4 | The diffusion of photons occurs due to the unimpeded motion of electrons in the early universe and the limited thickness of the photon-baryonic fluid |

| 5 | Re-ionization refers to the process when the initially neutral hydrogen in the universe becomes ionized by the first light sources, such as stars and quasars. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | The potential wells and hills observed are a consequence of density fluctuations. These fluctuations can be likened to a spring-mass system, where the baryon mass acts as the loaded mass and the photon pressure represents the spring. |

| 8 | adding mass to the baryon |

| 9 | Gravitational Waves: Ripples in the spacetime fabric. |

| 10 | Post-doc at the Centre for Particle Cosmology at the University of Pennsylvania.(https://tanvikarwal.wordpress.com/) |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Dark Energy Survey |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | LAMBDA - TE and EE Power Spectrum Plot Data Sources. (n.d.). LAMBDA - TE and EE Power Spectrum Plot Data Sources. Retrieved June 7, 2023, from https://lambda.gsfc.nasa.gov/education/lambda-graphics/more/te-spectrum-source.html

|

| 17 | *THE NEW MODEL IS A TOPIC OF FURTHER RESEARCH AND HOLDS ITS IMPORTANCE BEYOND THE SCOPE OF THIS 2 MONTHS INTERNSHIP* |

| Universe | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Mean | Mean of Mean |

| Value | Value | Value | Overall | values of Direct and | |

| Indirect Measurements | |||||

| Early | 67.27 | 71.3 | 68.54 | ||

| (Indirect) | 71.65 | 70.56 | |||

| Late | 67.4 | 76.0 | 72.59 | ||

| (Direct) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).