Submitted:

15 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Mechanism of action

Biomarkers

- PD-L1:

- Tumour mutational burden (TMB):

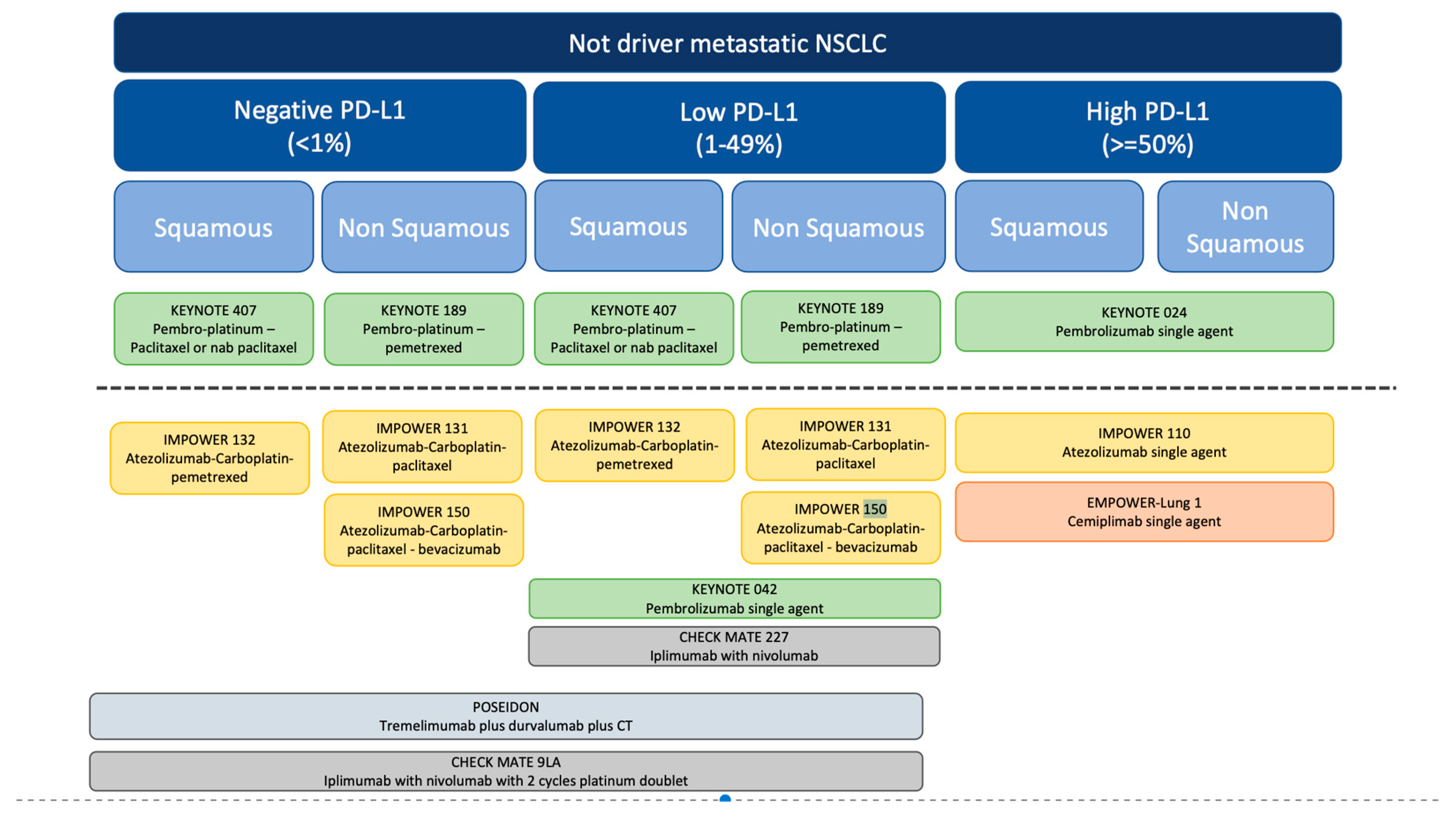

Chemotherapy free regimens

Single agent

Pembrolizumab

Atezolizumab

Cemiplimab

Immunotherapy combinations

- Nivolumab plus ipilimumab

- Durvalumab plus tremelimumab

Combinations with chemotherapy

- Atezolizumab

- Cemiplimab

- Nivolumab/Ipilimumab

- Pembrolizumab

- Tremelimumab plus durvalumab

Second line therapy

Atezolizumab

Nivolumab

Pembrolizumab

Adverse effects

Discussion/ practical considerations

-Biomarkers

-Regimen selection

-Duration of therapy

-Effectiveness in target population

Conclusion

References

- Punekar, S.R.; Shum, E.; Grello, C.M.; Lau, S.C.; Velcheti, V. Immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: Past, present, and future directions. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 877594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steven A, Fisher SA, Robinson BW. Immunotherapy for lung cancer. Respirology [Internet]. 2016 Jul;21(5). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27101251/ (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Hsu, M.L.; Naidoo, J. Principles of Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2020, 30, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowshanravan, B.; Halliday, N.; Sansom, D.M. CTLA-4: a moving target in immunotherapy. Blood 2018, 131, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, A.; Gharibi, T.; Marofi, F.; Babaloo, Z.; Baradaran, B. CTLA-4: From mechanism to autoimmune therapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 80, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder EI, Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways: Similarities, Differences, and Implications of Their Inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2016 Feb;39(1). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26558876/ (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Freeman, G.J.; Long, A.J.; Iwai, Y.; Bourque, K.; Chernova, T.; Nishimura, H.; Fitz, L.J.; Malenkovich, N.; Okazaki, T.; Byrne, M.C.; et al. Engagement of the Pd-1 Immunoinhibitory Receptor by a Novel B7 Family Member Leads to Negative Regulation of Lymphocyte Activation. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Boyle TA, Zhou C, Rimm DL, Hirsch FR. PD-L1 Expression in Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol [Internet]. 2016 Jul;11(7). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27117833/ (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Kerr KM, Tsao MS, Nicholson AG, Yatabe Y, Wistuba II, Hirsch FR. Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Immunohistochemistry in Lung Cancer: In what state is this art? J Thorac Oncol [Internet]. 2015 Jul;10(7). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26134220/ (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Büttner R, Gosney JR, Skov BG, Adam J, Motoi N, Bloom KJ, et al. Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Immunohistochemistry Testing: A Review of Analytical Assays and Clinical Implementation in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2017 Dec 1;35(34). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29053400/ (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Hirsch, F.R.; McElhinny, A.; Stanforth, D.; Ranger-Moore, J.; Jansson, M.; Kulangara, K.; Richardson, W.; Towne, P.; Hanks, D.; Vennapusa, B.; et al. PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry Assays for Lung Cancer: Results from Phase 1 of the Blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassanelli, M.; Sioletic, S.; Martini, M.; Giacinti, S.; Viterbo, A.; Staddon, A.; Liberati, F.; Ceribelli, A. Heterogeneity of PD-L1 Expression and Relationship with Biology of NSCLC. Anticancer. Res. 2018, 38, 3789–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munari, E.; Zamboni, G.; Lunardi, G.; Marchionni, L.; Marconi, M.; Sommaggio, M.; Brunelli, M.; Martignoni, G.; Netto, G.J.; Hoque, M.O.; et al. PD-L1 Expression Heterogeneity in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: Defining Criteria for Harmonization between Biopsy Specimens and Whole Sections. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, L.; Kerr, K.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.; Solomon, B.; et al. Non-oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw [Internet]. 2021 Mar 2;19(3). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33668021/ (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Bodor, J.N.; Boumber, Y.; Borghaei, H. Biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibition in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Cancer 2020, 126, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesma, A.; Pardo, J.; Cruellas, M.; Gálvez, E.M.; Gascón, M.; Isla, D.; Martínez-Lostao, L.; Ocáriz, M.; Paño, J.R.; Quílez, E.; et al. From Tumor Mutational Burden to Blood T Cell Receptor: Looking for the Best Predictive Biomarker in Lung Cancer Treated with Immunotherapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Bernabe Caro, R.; Zurawski, B.; Kim, S.-W.; Carcereny Costa, E.; Park, K.; Alexandru, A.; Lupinacci, L.; de la Mora Jimenez, E.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2020–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thai, A.A.; Solomon, B.J.; Sequist, L.V.; Gainor, J.F.; Heist, R.S. Lung cancer. Lancet 2021, 398, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50%. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2339–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, T.S.K.; Wu, Y.-L.; Kudaba, I.; Kowalski, D.M.; Cho, B.C.; Turna, H.Z.; Castro, G., Jr.; Srimuninnimit, V.; Laktionov, K.K.; Bondarenko, I.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Giaccone, G.; de Marinis, F.; Reinmuth, N.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Andric, Z.; Geater, S.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1–Selected Patients with NSCLC. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassem, J.; de Marinis, F.; Giaccone, G.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Oprean, C.; Kim, Y.-C.; Andric, Z.; et al. Updated Overall Survival Analysis From IMpower110: Atezolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Treatment-Naive Programmed Death-Ligand 1–Selected NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1872–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiravand, Y.; Khodadadi, F.; Kashani, S.M.A.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Hosseini, S.; Sadeghirad, H.; Ladwa, R.; O’byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3044–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, A.; Kilickap, S.; Gümüş, M.; Bondarenko, I.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Gogishvili, M.; Turk, H.M.; Cicin, I.; Bentsion, D.; Gladkov, O.; et al. Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: a multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garassino, M.; Kilickap, S.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Sezer, A.; Gumus, M.; Bondarenko, I.; Gogishvili, M.; Nechaeva, M.; Schenker, M.; Cicin, I.; et al. OA01.05 Three-year Outcomes per PD-L1 Status and Continued Cemiplimab Beyond Progression + Chemotherapy: EMPOWER-Lung 1. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, e2–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Pluzanski, A.; Lee, J.S.; Otterson, G.A.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Minenza, E.; Linardou, H.; Burgers, S.; Salman, P.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmer JR, Lee JS, Ciuleanu TE, Bernabe CR, Nishio M, Urban L, et al. Five-Year Survival Outcomes With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab Versus Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in CheckMate 227. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2023 Feb 20;41(6). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36223558/ (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Rizvi NA, Cho BC, Reinmuth N, Lee KH, Luft A, Ahn MJ, et al. Durvalumab With or Without Tremelimumab vs Standard Chemotherapy in First-line Treatment of Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The MYSTIC Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology [Internet]. 2020 May 1;6(5). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32271377/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Socinski, M.A.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2288–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogami, N.; Barlesi, F.; Socinski, M.A.; Reck, M.; Thomas, C.A.; Cappuzzo, F.; Mok, T.S.; Finley, G.; Aerts, J.G.; Orlandi, F.; et al. IMpower150 Final Exploratory Analyses for Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab and Chemotherapy in Key NSCLC Patient Subgroups With EGFR Mutations or Metastases in the Liver or Brain. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 17, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IMpower150 Final Overall Survival Analyses for Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab and Chemotherapy in First-Line Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2021, 16, 1909–1924. [CrossRef]

- West, H.; McCleod, M.; Hussein, M.; Morabito, A.; Rittmeyer, A.; Conter, H.J.; Kopp, H.-G.; Daniel, D.; McCune, S.; Mekhail, T.; et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 924–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jotte, R.; Cappuzzo, F.; Vynnychenko, I.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Hussein, M.; Soo, R.; Conter, H.J.; Kozuki, T.; Huang, K.-C.; et al. Atezolizumab in Combination With Carboplatin and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Squamous NSCLC (IMpower131): Results From a Randomized Phase III Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Saito, H.; Goto, K.; Watanabe, S.; Sueoka-Aragane, N.; Okuma, Y.; Kasahara, K.; Chikamori, K.; Nakagawa, Y.; Kawakami, T. IMpower132: Atezolizumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy vs chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC in Japanese patients. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogishvili, M.; Melkadze, T.; Makharadze, T.; Giorgadze, D.; Dvorkin, M.; Penkov, K.; Laktionov, K.; Nemsadze, G.; Nechaeva, M.; Rozhkova, I.; et al. Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2374–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makharadze, T.; Gogishvili, M.; Melkadze, T.; Baramidze, A.; Giorgadze, D.; Penkov, K.; Laktionov, K.; Nemsadze, G.; Nechaeva, M.; Rozhkova, I.; et al. Cemiplimab Plus Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Alone in Advanced NSCLC: 2-Year Follow-Up From the Phase 3 EMPOWER-Lung 3 Part 2 Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.G.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Cobo, M.; Bennouna, J.; Schenker, M.; Cheng, Y.; Juan-Vidal, O.; Mizutani, H.; Lingua, A.; Reyes-Cosmelli, F.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab With Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Alone for Metastatic NSCLC in CheckMate 9LA: 3-Year Clinical Update and Outcomes in Patients With Brain Metastases or Select Somatic Mutations. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 18, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Cobo, M.; Schenker, M.; Zurawski, B.; Menezes, J.; Richardet, E.; Bennouna, J.; Felip, E.; Juan-Vidal, O.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, L.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Gadgeel, S.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; De Angelis, F.; Domine, M.; Clingan, P.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2078–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garassino, M.C.; Gadgeel, S.; Speranza, G.; Felip, E.; Esteban, E.; Dómine, M.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; Bischoff, H.G.; Peled, N.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Luft, A.; Vicente, D.; Tafreshi, A.; Gümüş, M.; Mazières, J.; Hermes, B.; Çay Şenler, F.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2040–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, S.; Kowalski, D.M.; Luft, A.; Gümüş, M.; Vicente, D.; Mazières, J.; Rodríguez-Cid, J.; Tafreshi, A.; Cheng, Y.; Lee, K.H.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Langer, C.J.; Paz-Ares, L.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Halmos, B.; Garassino, M.C.; Houghton, B.; Kurata, T.; Cheng, Y.; Lin, J.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer without tumor PD-L1 expression: A pooled analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials. Cancer 2020, 126, 4867–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.L.; Cho, B.C.; Luft, A.; Alatorre-Alexander, J.; Geater, S.L.; Laktionov, K.; Kim, S.-W.; Ursol, G.; Hussein, M.; Lim, F.L.; et al. Durvalumab With or Without Tremelimumab in Combination With Chemotherapy as First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The Phase III POSEIDON Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittmeyer, A.; Barlesi, F.; Waterkamp, D.; Park, K.; Ciardiello, F.; von Pawel, J.; Gadgeel, S.M.; Hida, T.; Kowalski, D.M.; Dols, M.C.; et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazieres, J.; Rittmeyer, A.; Gadgeel, S.; Hida, T.; Gandara, D.R.; Cortinovis, D.L.; Barlesi, F.; Yu, W.; Matheny, C.; Ballinger, M.; et al. Atezolizumab Versus Docetaxel in Pretreated Patients With NSCLC: Final Results From the Randomized Phase 2 POPLAR and Phase 3 OAK Clinical Trials. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 16, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; Spigel, D.R.; Steins, M.; Ready, N.E.; Chow, L.Q.; Vokes, E.E.; Felip, E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CheckMate 171: A phase 2 trial of nivolumab in patients with previously treated advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer, including ECOG PS 2 and elderly populations_OLD [Internet]. Available online: https://es.ereprints.elsevier.cc/checkmate-171-phase-2-trial-nivolumab-patients-previously-treated-advanced-squamous-non-small-cell/fulltext (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, Chow LQM, Burgio MA, de Castro Carpeno J, et al. Five-Year Outcomes From the Randomized, Phase III Trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2021 Mar 1;39(7). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33449799/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Herbst, R.S.; Baas, P.; Kim, D.-W.; Felip, E.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Han, J.-Y.; Molina, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Arvis, C.D.; Ahn, M.-J.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 387, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, R.S.; Garon, E.B.; Kim, D.-W.; Cho, B.C.; Gervais, R.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Han, J.-Y.; Majem, M.; Forster, M.D.; Monnet, I.; et al. Five Year Survival Update From KEYNOTE-010: Pembrolizumab Versus Docetaxel for Previously Treated, Programmed Death-Ligand 1–Positive Advanced NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1718–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown TJ, Mamtani R, Bange EM. Immunotherapy Adverse Effects. JAMA oncology [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1;7(12). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34709372/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Martins, F.; Sofiya, L.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Lamine, F.; Maillard, M.; Fraga, M.; Shabafrouz, K.; Ribi, C.; Cairoli, A.; Guex-Crosier, Y.; et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: Epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara R, Imbimbo M, Malouf R, Paget-Bailly S, Calais F, Marchal C, et al. Single or combined immune checkpoint inhibitors compared to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for people with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2021;2021(4). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8092423/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Zhou, C.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; An, D.; Li, B. Adverse events of immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 102, 108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichloo, A.; Albosta, M.; Dahiya, D.; Guidi, J.C.; Aljadah, M.; Singh, J.; Shaka, H.; Wani, F.; Kumar, A.; Lekkala, M. Systemic adverse effects and toxicities associated with immunotherapy: A review. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 12, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson JA, Schneider BJ, Brahmer J, Achufusi A, Armand P, Berkenstock MK, et al. Management of Immunotherapy-Related Toxicities, Version 1.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw [Internet]. 2022 Apr;20(4). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35390769/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Di Federico A, De Giglio A, Parisi C, Gelsomino F. STK11/LKB1 and KEAP1 mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: Prognostic rather than predictive? Eur J Cancer [Internet]. 2021 Nov;157. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34500370/ (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Sholl, L.M. Biomarkers of response to checkpoint inhibitors beyond PD-L1 in lung cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Herbst, R.S.; Goldberg, S.B. Selecting the optimal immunotherapy regimen in driver-negative metastatic NSCLC. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, D.M.; Garon, E.B.; Chandler, J.; McCleod, M.; Hussein, M.; Jotte, R.; Horn, L.; Daniel, D.B.; Keogh, G.; Creelan, B.; et al. Continuous Versus 1-Year Fixed-Duration Nivolumab in Previously Treated Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: CheckMate 153. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3863–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazieres, J.; Drilon, A.; Lusque, A.B.; Mhanna, L.; Cortot, A.; Mezquita, L.; Thai, A.A.; Mascaux, C.; Couraud, S.; Veillon, R.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainor, J.F.; Shaw, A.T.; Sequist, L.V.; Fu, X.; Azzoli, C.G.; Piotrowska, Z.; Huynh, T.G.; Zhao, L.; Fulton, L.; Schultz, K.R.; et al. EGFR Mutations and ALK Rearrangements Are Associated with Low Response Rates to PD-1 Pathway Blockade in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4585–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, A.T.; Lee, S.-H.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Bauer, T.M.; Boyer, M.J.; Costa, E.C.; Felip, E.; Han, J.-Y.; Hida, T.; Hughes, B.G.M.; et al. Avelumab (anti–PD-L1) in combination with crizotinib or lorlatinib in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC: Phase 1b results from JAVELIN Lung 101. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 9008–9008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxnard, G.R.; Yang, J.C.-H.; Yu, H.; Kim, S.-W.; Saka, H.; Horn, L.; Goto, K.; Ohe, Y.; Mann, H.; Thress, K.S.; et al. TATTON: a multi-arm, phase Ib trial of osimertinib combined with selumetinib, savolitinib, or durvalumab in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug | Type | Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Atezolizumab | Anti-PD-L1 | First-line treatment (*, **): - Monotherapy for patients with mNSCLC without EGFR or ALK genomic tumour aberrations and PD-L1 stained ≥ 50% of tumour cells or PD-L1 stained tumour-infiltrating immune cells ≥ 10%. - In combination with bevacizumab and chemotherapy (platinum- based + paclitaxel/nab-paclitaxel) for patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC without EGFR or ALK aberrations and regardless PDL1 status. - In combination with chemotherapy (platinum- based + paclitaxel/nab-paclitaxel/ pemetrexed) for patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC without EGFR or ALK aberrations and regardless PDL1 status. Subsequent line monotherapy for the treatment of patients with mNSCLC who have disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy regardles histology and PDL1 status (*, **). |

| Cemiplimab | Anti-PD1 | First-line treatment (*, **): - Monotherapy for patients with mNSCLC with no EGFR, ALK or ROS1 aberrations and with high PD-L1 expression [Tumour Proportion Score (TPS) ≥ 50%]. - In combination with chemotherapy for patients with mNSCLC without EGFR, ALK or ROS1 aberrations, regardless histology and PD-L1 status. |

| Nivolumab | Anti-PD1 | Subsequent line monotherapy for the treatment mNSCLC who has been progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients with EGFR or ALK aberrations must have disease progression at least one target therapy (*, **). |

| Nivolumab/ Ipililumab | Anti-PD1/ Anti-CTLA4 | First-line treatment (*, **): - In combination for patients with mNSCLC expressing PD-L1 ≥1%, with no EGFR or ALK genomic tumour aberrations. - In combination with platinum-based chemotherapy for 2 cycles in adults, whose tumours have no EGFR mutation or ALK translocation, regardless PDL-1 expression. |

| Pembrolizumab | Anti-PD1 | First-line treatment (*, **): - Single agent for patients with NSCLC expressing PD-L1 (TPS) ≥1% with no EGFR or ALK genomic tumour aberrations. - In combination with pemetrexed and platinum chemotherapy for patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC, without EGFR or ALK genomic tumour aberrations. - In combination with carboplatin and either paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel for patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC. Subsequent-line treatment (*, **): - Single agent patients with mNSCLC with PD-L1 (TPS ≥1%), whose had progression on or after platinum-containing chemotherapy. Patients with EGFR or ALK aberrations must have disease progression at least one target therapy. |

| Tremelimumab/ Durvalumab | Anti-CTLA4/Anti-PD-L1 | First-line treatment in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with mNSCLC without EGFR or ALK genomic tumour aberrations, regardless histology. |

| ICIs | Trial | Population | Primary endpoint | ORR | PFS | OS | 5y/ 3y *-ORR | 5y/3y*- PFS | 5y/3y*-OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atezolizumab | IMpower 110 | PD-L1 ≥ 50% or IC ≥10%; squamous and non-squamous histology | OS | 38.3 vs 28.6 % | 8.1 vs 5.0 months | 20.2 vs 13.1 months | 40.2% | 8.2 months | 20.2 vs 14.7 months |

| Cemiplimab | EMPOWER-Lung 1 | PD-L1 ≥ 50%; squamous and non-squamous histology | OS and PFS | 39.0 vs 20% | 8.2 vs 5.7 months | NR vs 14.2 months | 46.5 vs 21.0%* | 8.1 vs 5.3 months* | 26.1 months* |

| Nivolumab plus ipilimumab | CheckMate 227 | PD-L1 ≥ 1%; squamous and non-squamous histology | OS | 35.9 vs 30.0% | 5.1 vs 5.6 months | 17.1 vs 14.9 months | 24% | ||

| Pembrolizumab | KEYNOTE-024 | PD-L1 ≥ 50%; squamous and non-squamous histology | PFS | 45% | 10.3 months | 26.3 months (80.2%). | 46.1 vs 31.1% | 7.7 vs 5.5 months | 26.3 vs 13.4 months (31.9%) |

| KEYNOTE-042 | PD-L1 ≥ 1%; squamous and non-squamous histology | OS | 27vs 27% | 5.4 vs 6.5 months | 16.7 vs 12.1 months | 27.3% | 5.6 months | 16.4 months |

| ICIs | Trial | Population | Primary endpoint | ORR | PFS | OS | 5y/ 3y *-ORR | 5y/3y*- PFS | 5y/3y*-OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab plus CT | IMpower150 | Any PD-L1 and Non-squamous histology | PFS and OS | 63.5% (ABCP) vs 48.0% (BCP) |

8.3 vs 6.8 months ABCP vs BCP HR 0.62 (95% CI 0.52-0.74) |

19.5 vs 14.7 months ABCP vs BCP: HR 0.78 (95% CI 0.64-0.96) |

8.4 vs 6.8 months ABCP vs BCP HR 0.57 (95% CI 0.48-0.67) |

19.5 vs 14.7 months HR 0.80 (95% CI 0.67-0.95) | |

| Atezolizumab plus platinum plus paclitaxel/nab paclitaxel | IMpower130 | Any PD-L1 and Non-squamous histology | PFS and OS | 49.2% vs 31.9% | 7.0 versus 5.5 months (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.54-0.77) | 18.6 versus 13.9 months (HR 0.79; 95% CI 0·64-0·98) | - | - | - |

| Atezolizumab plus platinum plus paclitaxel/nab paclitaxel | IMpower131 | Any PD-L1 and squamous histology | PFS and OS | 49.4% vs 41.3% | 6.3 vs 5.6 months HR 0.71 (95% CI 0.60–0.85) | 14.2 versus 13.5 months (HR 0.88; 95% CI 0.73-1.05) | - | - | - |

| Atezolizumab plus platinum plus pemetrexed | IMpower132 | Any PD-L1 and Non-squamous histology | PFS and OS | 47% vs 32% | 7.6 versus 5.2 months; HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.49-0.72 | 18.1 versus 13.6 months; HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.64-1.03 | - | - | 17.5 vs 13.6 months*; HR 0.86 (0.71-1.06) |

| Cemiplimab plus platinum-doublet chemotherapy | EMPOWER-Lung 3 | Any PD-L1; squamous and Non-squamous histology | OS | 43.3% vs 22.7% | 8.2 vs 5.0 months HR = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.44–0.70 | 21.9 vs 13.9 months; HR 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53- 0.93 | 43.6% versus 22.1% | 8.2 months versus 5.5 months (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.44–0.68 | 21.1 versus 12.9 months; HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.51–0.82 |

| Nivolumab plus ipilimumab and 2 cycles of platinum-doublet chemotherapy | CheckMate 9LA | Any PD-L1; squamous and Non-squamous histology | OS | 37.7% vs 25.1% | 6.8 vs 5.0 months HR 0.70 [97·48% CI 0.57–0.86 |

14.1 versus 10.7 months; HR 0.69; 96.71% CI 0.55-0.87 | 38% vs 25%* | 6.4 versus 5.3 months * | 15.8 versus 11 months *; HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.62–0.87 |

| Pembrolizumab plus platinum (carboplatin or cisplatin) plus pemetrexed | KEYNOTE-189 | Any PD-L1 and Non-squamous histology | PFS and OS | 47.6% vs 18.9% | 8.8 vs 4.9 months HR 0.52 (95% CI 0.43–0.64) |

NR vs 11.3 months; HR 0.49; 95% CI 0.38 - 0.64 |

48.3% vs 19.9% | 9.0 versus 4.9 months; HR 0.5; 95% CI 0.42‒0.60 | 22.0 versus 10.6 months; HR 0.6; 95% CI 0.50-0.72 |

| Pembrolizumab plus platinum (carboplatin or cisplatin) plus Paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel | KEYNOTE-407 | Any PD-L1 and squamous histology | PFS and OS | 57.9% vs 38.4% | 6.4 versus 4.8 months; HR 56; 95% CI 0.45-0.70 | 15.9 months and 11.3 months HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.49 - 0.85 | 66.2% vs 38.8% | 8 versus 5.1 months; HR 0.62; CI 0.52-0.74 | 17.2 versus 11.6 months HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.59-0.85 |

| Tremelimumab plus durvalumab plus CT | POSEIDON | Any PD-L1; squamous and Non-squamous histology | PFS and OS | 46.3% vs 33.4% | 6.2 v 4.8 months; HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.60 - 0.86 | 14.0 versus 11.7 months; HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.65 - 0.92 | - | - | - |

| ICIs | Trial | Population | Primary endpoint | ORR | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atezolizumab | OAK | Patients with NSCLC, any histology, whose had received one or two previous chemotherapy regimens for stage IIIB or IV, except docetaxel, CD137 agonists, anti-CTLA4, anti PD-L1 or PD-1. | OS | 14% vs 13% | 2.8 VS 4.0 months; HR 0.95 95% CI 0.82-1.10 | 13.8 vs 9.6 months; HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.62-0.87. 4y rate: 15.5% vs 8.7%. |

| Nivolumab | CheckMate-057 | Patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC who progressed after the first line with platinum-based doublet CT. | OS | 19% vs 12% | 2.3 vs 4.7 months (HR 0.92; 95% CI 0.77-1.11 | 12.2 vs 9.4 months (HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.59-0.89 |

| CheckMate-017 | Patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC who progressed after the first line with platinum-based doublet CT. | OS | 20% vs 9% | 3.5 versus 2.8 months (HR 0.62; 95% CI 0.47- 0.81 | 9.2 vs 6.0 months HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.44–0.79 | |

| Pembrolizumab | KEYNOTE-010 | Previously treated patients with PD-L1 positive (≥1%) advanced NSCLC, regardless histology | PFS and OS | 18% vs 9% | 4.0 versus 4.0 months (HR 0·79, 0·66–0·94 | 12.7 vs 5.5 months HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.58-0.88 5y: 11.8 months versus 8.4 months (HR 0.70; CI 0.61–0.80) |

| Drug | Dose | Diarrhea | Colitis | Pulmonary | Rash | Neurological | Endocrinopathy | Hepatic | Renal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atezolizumab | |||||||||

| IMPOWER 110 | 1,200 mg 3-weekly | - | - | 4.9% | - | - | - | - | - |

| IMPOWER 150 | 1,200 mg 3-weekly | 20.6% | - | - | 13.3% | 49.4% (neuropathy included) | - | - | |

| OAK | 1,200 mg 3-weekly | 15.4% | 0.3% | 1% | - | - | - | 0.3% | - |

| Cemiplimab | |||||||||

| EMPOWER-Lung 1 | 350 mg 3-weekly | 5% | 1% | 6% | 5% | 3% | - | 6% | 1% |

| EMPOWER-Lung 1 | 350 mg 3-weekly | 10.6% | - | 12.5% | - | - | - | 30% | - |

| Nivolumab | |||||||||

| CheckMate 057 |

3 mg/kg, 2-weekly | 8% | 1% | 4.9% | 9% | 0.3% | 10.5% |

10.8% | 2% |

| Nivolumab/ Ipililumab | |||||||||

| CHECK MATE 227 |

1 mg/kg 6-weekly ipilimumab plus 3 mg/kg 2-weekly nivolumab (576) |

16.3% | 1% | 3% | 16.7% | - |

12.3% |

3.5% | - |

| Pembrolizumab | |||||||||

| KEYNOTE-054 | 200 mg, 3-weekly | 19.1% | 3.7% | 4.7% | 16.1% | – | 23.4% | 1.8% | 0.4% |

| KEYNOTE-010 | 10 mg/kg, 3-weekly | 6% | 1% | 4% | 13% | – | 16.5% | 1% | – |

| KEYNOTE-189 | 200 mg, 3-weekly | - | 2.2% | 4.4% | 2% | - | 12.8% | - | 1.7% |

| KEYNOTE-042 | 200 mg, 3-weekly | 5% | 1% | 8% | 7% | 1% | 18% | 7% | <1% |

| Tremelimumab/ Durvalumab | |||||||||

| POSEIDON | 13.9% | 3.9% | 3.6% | 3.9% | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).