Submitted:

14 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Literature search

2.2. Delphi process

2.3. Antimicrobial resistance

2.4. General use of antibiotics

2.5. The use of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections

2.6. The use of antibiotics for urinary tract infections

3. Discussion.

3.1. Main findings

3.2. Strengths and limitations of the study

3.3. Comparison with existing literature

4. Materials and Methods

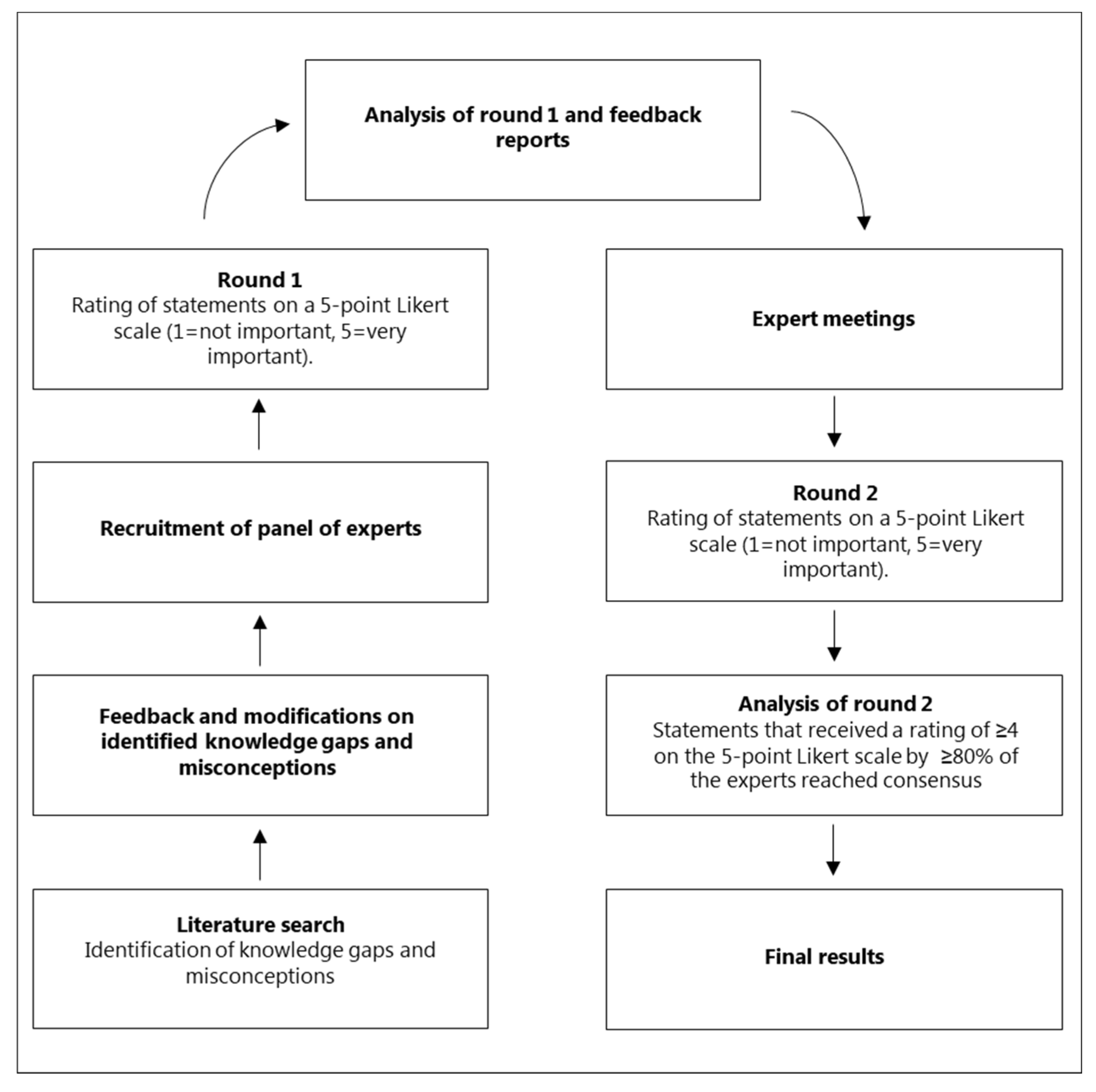

4.1. Design

4.2. Recruitment and sample size

4.3. Identification of misconceptions and knowledge gaps

4.4. Data collection

4.4.1. Round 1

4.4.2. Feedback and expert meetings

4.4.3. Round 2

4.5. Definition of consensus and end of Delphi process

4.6. Data analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of abbreviations:

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| HCP(s) | Healthcare professional(s) |

| EU | European Union |

| HAPPY PATIENT | Health Alliance for Prudent Prescribing and Yield of Antibiotics in a Patient-Centred Perspective |

| OoHS | Out-of-hours services |

| RTIs | Respiratory tract infections |

| UTIs | Urinary tract infections |

References

- World Health Organisation. Antimicrobial resistance [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance.

- Murray CJ, Shunji Ikuta K, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Robles Aguilar G, Gray A, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 25];399:629–55. [CrossRef]

- Ventola CL. The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis: Part 1: Causes and Threats. Pharmacy and Therapeutics [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 Oct 25];40(4):277. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4378521/.

- Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Dec 7];5(6):229. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4232501/.

- Charani E, Cooke J, Holmes A. Antibiotic stewardship programmes-what’s missing? Antibiotic prescribing-a global concern. J Antimicrob Chemother [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2022 Oct 25];65:2275–7. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jac/article/65/11/2275/768215.

- Macdougall C, Polk RE. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Health Care Systems. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(4):638–56.

- Slettli Wathne J, Kåre L, Kleppe S, Harthug S, Blix HS, Nilsen RM, et al. The effect of antibiotic stewardship interventions with stakeholder involvement in hospital settings: a multicentre, cluster randomized controlled intervention study. [cited 2022 Oct 25] . [CrossRef]

- van Buul LW, Sikkens JJ, van Agtmael MA, H Kramer MH, van der Steen JT, P M Hertogh CM. Participatory action research in antimicrobial stewardship: a novel approach to improving antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals and long-term care facilities. [cited 2022 Oct 25]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jac/article/69/7/1734/2911110.

- Napolitano F, Izzo MT, di Giuseppe G, Angelillo IF. Public Knowledge, Attitudes, and Experience Regarding the Use of Antibiotics in Italy. PLoS One [Internet]. 2013 Dec 23 [cited 2022 Dec 7];8(12):e84177. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0084177.

- Tangcharoensathien V, Chanvatik S, Kosiyaporn H, Kirivan S, Kaewkhankhaeng W, Thunyahan A, et al. Population knowledge and awareness of antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance: results from national household survey 2019 and changes from 2017. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Dec 7];21(1):1–14. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-12237-y.

- Jairoun A, Hassan N, Ali A, Jairoun O, Shahwan M, Hassali M. University students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding antibiotic use and associated factors: a cross-sectional study in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Gen Med [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Dec 7];12:235. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6607982/.

- Sakr S, Ghaddar A, Hamam B, Sheet I. Antibiotic use and resistance: An unprecedented assessment of university students’ knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) in Lebanon. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Apr 19 [cited 2022 Dec 7];20(1):1–9. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-08676-8.

- Karasneh RA, Al-Azzam SI, Ababneh M, Al-Azzeh O, Al-Batayneh OB, Muflih SM, et al. Prescribers’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors on antibiotics, antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in jordan. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2022 Dec 7];10(7):858. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/10/7/858/htm.

- El-Sokkary R, Kishk R, El-Din SM, Nemr N, Mahrous N, Alfishawy M, et al. Antibiotic Use and Resistance Among Prescribers: Current Status of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice in Egypt. Infect Drug Resist [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Dec 7];14:1209–18. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33790591/.

- Al-Taani GM, Al-Azzam S, Karasneh RA, Sadeq AS, Mazrouei N al, Bond SE, et al. Pharmacists’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Behaviors and Information Sources on Antibiotic Use and Resistance in Jordan. Antibiotics (Basel) [Internet]. 2022 Feb 1 [cited 2022 Dec 7];11(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35203777/.

- Bjerrum A, García-Sangenís A, Modena D, Córdoba G, Bjerrum L, Chalkidou A, et al. Health alliance for prudent prescribing and yield of antibiotics in a patient-centred perspective (HAPPY PATIENT): a before-and-after intervention and implementation study protocol. BMC Primary Care [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Dec 7];23(1):1–11. Available from: https://bmcprimcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-022-01710-1.

- Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and Reporting the Delphi Method for Selecting Healthcare Quality Indicators: A Systematic Review. PLoS One [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2022 Oct 25];6(6):20476. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3111406/.

- Trevelyan EG, Robinson N. Delphi methodology in health research: how to do it? Eur J Integr Med. 2015 Aug 1;7(4):423–8.

- Mcmillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:655–62.

- Belton I, MacDonald A, Wright G, Hamlin I. Improving the practical application of the Delphi method in group-based judgment: A six-step prescription for a well-founded and defensible process. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2019 Oct 1;147:72–82.

- Skulmoski GJ, Hartman FT, Krahn J. The Delphi Method for Graduate Research The Delphi Method for Graduate Research 2. Journal of Information Technology Education. 2007;6.

- Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs [Internet]. 2003 Feb 1 [cited 2022 Oct 25];41(4):376–82. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x.

- Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and Reporting the Delphi Method for Selecting Healthcare Quality Indicators: A Systematic Review. PLoS One [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2022 Nov 17];6(6):20476. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3111406/.

- Lange T, Kopkow C, Lützner J, Günther KP, Gravius S, Scharf HP, et al. Comparison of different rating scales for the use in Delphi studies: Different scales lead to different consensus and show different test-retest reliability. BMC Med Res Methodol [Internet]. 2020 Feb 10 [cited 2022 Nov 17];20(1):1–11. Available from: https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-020-0912-8.

- Keeney S, Hasson F, Mckenna H. The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research. The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research [Internet]. 2010 Dec 3 [cited 2022 Nov 22]; Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781444392029.

- Toma C, Picioreanu I. The Delphi Technique: Methodological Considerations and the Need for Reporting Guidelines in Medical Journals. Int J Public Health Res [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Nov 17];4(6):47–59. Available from: http://www.openscienceonline.com/journal/ijphr.

- Md Rezal RS, Hassali MA, Alrasheedy AA, Saleem F, Md Yusof FA, Godman B. Physicians’ knowledge, perceptions and behaviour towards antibiotic prescribing: a systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther [Internet]. 2015 May 1 [cited 2022 Dec 7];13(5):665–80. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25813839/.

- Harris A, Chandramohan S, Awali RA, Grewal M, Tillotson G, Chopra T. Physicians’ attitude and knowledge regarding antibiotic use and resistance in ambulatory settings. Am J Infect Control. 2019 Aug 1;47(8):864–8.

- Teixeira Rodrigues A, Roque F, Falcão A, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Understanding physician antibiotic prescribing behaviour: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013 Mar 1;41(3):203–12.

- Dempsey PP, Businger AC, Whaley LE, Gagne JJ, Linder JA. Primary care clinicians perceptions about antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchitis: A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract [Internet]. 2014 Dec 12 [cited 2022 Nov 28];15(1):1–10. Available from: https://bmcprimcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-014-0194-5.

- Gourgoulis GM, Katerelos P, Maragos A, Gargalianos P, Lazanas M, Maltezou HC. Antibiotic prescription and knowledge about antibiotic costs of physicians in primary health care centers in Greece. Am J Infect Control. 2013 Dec 1;41(12):1296–7.

- Cordoba G, Siersma V, Lopez-Valcarcel B, Bjerrum L, Llor C, Aabenhus R, et al. Prescribing style and variation in antibiotic prescriptions for sore throat: cross-sectional study across six countries. BMC Fam Pract [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 Dec 7];16(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25630870/.

- van der Velden A, Duerden MG, Bell J, Oxford JS, Altiner A, Kozlov R, et al. Prescriber and Patient Responsibilities in Treatment of Acute Respiratory Tract Infections — Essential for Conservation of Antibiotics. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2013 Jun 4 [cited 2022 Dec 7];2(2):316. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4790342/.

- Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Lador A, Sauerbrun-Cutler MT, Leibovici L. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2015 Apr 8 [cited 2022 Dec 7];2015(4). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8407041/.

- Mcnulty CAM, Collin SM, Cooper E, Lecky DM, Butler CC. Public understanding and use of antibiotics in England: findings from a household survey in 2017. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2019 Oct 1 [cited 2022 Dec 7];9(10):e030845. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/10/e030845.

- Pavydė E, Veikutis V, Mačiulienė A, Mačiulis V, Petrikonis K, Stankevičius E. Public Knowledge, Beliefs and Behavior on Antibiotic Use and Self-Medication in Lithuania. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2015 Jun 17 [cited 2022 Dec 7];12(6):7002. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4483745/.

- Godycki-Cwirko M, Cals JWL, Francis N, Verheij T, Butler CC, Goossens H, et al. Public Beliefs on Antibiotics and Symptoms of Respiratory Tract Infections among Rural and Urban Population in Poland: A Questionnaire Study. PLoS One [Internet]. 2014 Oct 2 [cited 2022 Dec 7];9(10):e109248. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0109248.

- Cals JWL, Boumans D, Lardinois RJM, Gonzales R, Hopstaken RM, Butler CC, et al. Public beliefs on antibiotics and respiratory tract infections: an internet-based questionnaire study. The British Journal of General Practice [Internet]. 2007 Dec 12 [cited 2022 Dec 7];57(545):942. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2084132/.

- van Hecke O, Butler CC, Wang K, Tonkin-Crine S. Parents’ perceptions of antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance (PAUSE): a qualitative interview study. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2019 Jun 1 [cited 2022 Dec 7];74(6):1741–7. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jac/article/74/6/1741/5382160.

- McCullough AR, Parekh S, Rathbone J, del Mar CB, Hoffmann TC. A systematic review of the public’s knowledge and beliefs about antibiotic resistance. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2016 Jan 1 [cited 2022 Dec 7];71(1):27–33. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jac/article/71/1/27/2363966.

- Course: TARGET antibiotics toolkit hub [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 7]. Available from: https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/course/view.php?id=553.

- Antibiotic awareness: posters and leaflets - GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/european-antibiotic-awareness-day-and-antibiotic-guardian-posters-and-leaflets.

- Print Materials | Antibiotic Use | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/print-materials.html.

- Communication toolkit to promote prudent antibiotic use aimed at primary care prescribers [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 7]. Available from: https://antibiotic.ecdc.europa.eu/en/toolkit-primary-care-prescribers.

| General practice | Out-of-hours Services | Nursing homes | Pharmacies | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Greece | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Lithuania | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

| Poland | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| Spain | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

| Total | 13 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 45 |

| General Practice | Out-of-Hours Services | Nursing Homes | Community Pharmacies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 (N=17) | Round 2 (N=13) | Round 1 (N=16) | Round 2 (N=12) | Round 1 (N=15) | Round 2 (N=8) | Round 1 (N=18) | Round 2 (N=12) | |

| Theme 1: AMR1 (8) | 8 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Theme 2: Antibiotic use (9) | 7 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| Theme 3: RTIs2 (15) |

13 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 12 |

| Theme 4: UTIs3 (12) |

11 | 12 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 8 |

| Total (44): | 39 | 34 | 26 | 30 | 18 | 24 | 31 | 36 |

| No | Statements Divided by Theme | Mean | Consensus Level (%) | Mean | Consensus Level (%) | Mean | Consensus Level (%) | Mean | Consensus Level (%) | 4-Setting Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Statements related to antimicrobial resistance in general | General practice | Out-of-hours services | Nursing homes | Community pharmacies | All settings | |||||

| 1 | Bacteria resistant to antibiotics are only present in hospitals* | 4.46 | 100.0 | 3.92 | 66.6 | 4.38 | 75.0 | 4.46 | 91.7 | |

| 2 | Antimicrobial resistance is not a problem in my country* | 4.46 | 84.6 | 4.46 | 91.7 | 4.46 | 87.5 | 4.46 | 91.7 | x |

| 3 | I cannot contribute to the increase of antimicrobial resistance* | 4.38 | 92.4 | 4.25 | 75.0 | 4.38 | 87.5 | 4.38 | 91.7 | |

| 4 | Others, not me, are responsible for controlling the problem of antimicrobial resistance† | 4.23 | 92.3 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 4.23 | 87.5 | 4.23 | 91.7 | |

| 5 | Antimicrobial Resistance is not a problem where I work† | 4.15 | 92.3 | 4.15 | 83.3 | 4.15 | 100.0 | 4.15 | 83.3 | x |

| 6 | Antimicrobial resistance is not an important problem because better antibiotics are continuously being discovered† | 4.08 | 84.7 | 4.08 | 91.7 | 4.08 | 100.0 | 4.08 | 91.7 | x |

| 7 | Not all antibiotics are at risk of becoming ineffective against infections by resistant bacteria* | 4.00 | 77.0 | 4.00 | 83.3 | 4.00 | 62.5 | 4.00 | 91.6 | x |

| 8 | If I am not exposed to antibiotics (e.g. directly by consuming antibiotics, or indirectly via the environment), then I cannot carry or transmit antibiotic-resistant bacteria* | 4.00 | 77.0 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 3.85 | 87.5 | 3.67 | 66.7 | |

| Theme 2: Statements about the use of antibiotics in general | General practice | Out-of-hours services | Nursing homes | Community pharmacies | All settings | |||||

| 9 | It is fine to use leftover antibiotics (or sharing antibiotics with family and friends) without consulting a healthcare professional, when experiencing similar symptoms to previous acute infections* | 4.92 | 100.0 | 4.92 | 91.6 | 4.13 | 75.0 | 4.92 | 100.0 | |

| 10 | The single presence of fever suggests high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics* | 4.46 | 92.3 | 4.17 | 75.0 | 4.46 | 87.5 | 4.46 | 100.0 | |

| 11 | The benefits of prescribing antibiotics when unsure of the bacterial or viral origin of the symptoms outweigh the harms of exposure to antibiotics† | 4.46 | 84.6 | 4.46 | 100.0 | 4.46 | 100.0 | 4.46 | 100.0 | x |

| 12 | Antibiotics are effective against all type of infections* | 4.38 | 84.6 | 4.38 | 100.0 | 4.38 | 100.0 | 4.38 | 100.0 | x |

| 13 | Broad spectrum antibiotics, such as quinolones and 3rd - 5th generation cephalosporines, are the best treatment options because they cover a wide range of bacteria† | 3.85 | 69.3 | 3.85 | 91.6 | 3.85 | 87.5 | 3.85 | 83.3 | |

| 14 | Ending the consultation without an antibiotic prescription, when the patient is asking for it, indicates lack of empathy from the doctor* | 3.85 | 77.0 | 3.85 | 91.7 | 4.13 | 75.0 | 3.85 | 91.7 | |

| 15 | Ending the consultation without an antibiotic prescription indicates that the doctor is not taking my symptoms seriously enough* | 3.77 | 69.3 | 4.25 | 91.7 | 3.77 | 100.0 | 3.77 | 91.7 | |

| 16 | Ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, tetracycline, trimethoprim do not cause sensitivity to sunlight† | 3.23 | 53.9 | 3.67 | 66.7 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 3.23 | 83.4 | |

| 17 | A good doctor is the one that prescribes the newest type of antibiotics† | 3.15 | 53.9 | 3.83 | 75.0 | 4.13 | 75.0 | 3.15 | 91.6 | |

| Theme 3: Statements about the use of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections | General practice | Out-of-hours services | Nursing homes | Community pharmacies | All settings | |||||

| 18 | More than 2 weeks coughing suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.69 | 92.3 | 4.69 | 100.0 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 4.69 | 100.0 | |

| 19 | As soon as I feel symptoms like sore throat, running nose, fever I should seek medical care to get antibiotics* | 4.62 | 92.3 | 4.62 | 83.3 | 4.62 | 100.0 | 4.62 | 91.6 | x |

| 20 | All children with middle ear inflammation and ear pain require antibiotic therapy† | 4.54 | 92.3 | 4.54 | 91.7 | 3.50 | 50.0 | 4.54 | 100.0 | |

| 21 | The single presence of tonsillar exudate in patients with sore throat suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.46 | 92.3 | 4.46 | 91.6 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 4.46 | 83.3 | |

| 22 | In patients with sore throat and other symptoms such as tonsillar exudates, fever, tender anterior cervical adenopathy, antibiotics have a great impact in the course of symptoms by shortening the length of symptoms by more than two days† | 4.46 | 100.0 | 4.46 | 91.7 | 4.46 | 100.0 | 4.46 | 83.4 | x |

| 23 | Based on the characteristics of the cough the health care professional can differentiate the viral or bacterial origin of the cough. For example, a chesty cough (wet, productive or phlegmy) means that it is caused by a bacterium† | 4.38 | 92.3 | 4.38 | 91.7 | 3.38 | 62.5 | 4.38 | 83.4 | |

| 24 | A patient with the combination of two or more of the following symptoms : a) nasal congestion, b) nasal discharge, c) pain in the face/teeth, d) reduced sense of smell, e) fever; requires antibiotic therapy independently of the number of days with symptoms† | 4.31 | 92.3 | 4.31 | 83.3 | 3.63 | 62.5 | 4.31 | 100.0 | |

| 25 | Cough with purulent sputum (or change of color of the sputum) suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.31 | 84.6 | 4.31 | 91.6 | 4.31 | 100.0 | 4.31 | 100.0 | x |

| 26 | The single presence of tender anterior cervical adenopathy in patients with sore throat suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.23 | 84.7 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 4.23 | 87.5 | 4.17 | 75.0 | |

| 27 | Purulent nasal discharge suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.23 | 84.6 | 4.23 | 91.7 | 4.23 | 87.5 | 4.23 | 100.0 | x |

| 28 | The majority of patients with a sore throat require antibiotic treatment† | 4.15 | 84.7 | 4.15 | 83.4 | 3.63 | 62.5 | 4.15 | 91.7 | |

| 29 | A bacterial infection is the most common cause of the single or combined presentation of the following symptoms: a) nasal congestion, b) nasal discharge, c) pain in the face/teeth, d) reduced sense of smell, e) fever† | 3.92 | 84.6 | 4.17 | 75.0 | 3.88 | 75.0 | 4.50 | 83.4 | |

| 30 | The presence of cough without other symptom suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.08 | 77.0 | 4.08 | 83.3 | 3.75 | 62.5 | 4.08 | 91.7 | |

| 31 | Macrolides are the best first option for treating a bacterial lower respiratory tract infection in order to cover typical and atypical pathogens† | 3.85 | 69.3 | 3.85 | 91.6 | 4.13 | 75.0 | 3.83 | 66.7 | |

| 32 | A sinus X-Ray can help doctors to discriminate the bacterial or viral origin of the rhinosinusitis symptoms† | 3.31 | 53.9 | 3.33 | 58.3 | 3.50 | 50.0 | 3.33 | 41.6 | |

| Theme 4: Statements about the use of antibiotics for urinary tract infections | General practice | Out-of-hours services | Nursing homes | Community pharmacies | All settings | |||||

| 33 | The single presence of painful discharge of urine suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.69 | 100.0 | 4.69 | 83.3 | 4.69 | 87.5 | 4.69 | 91.6 | x |

| 34 | The single presence of frequent urination suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.54 | 100.0 | 4.54 | 91.7 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 4.54 | 100.0 | |

| 35 | The single presence of burning sensation during urination suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.54 | 100.0 | 4.54 | 91.7 | 3.88 | 75.0 | 4.54 | 100.0 | |

| 36 | The single presence of blood in urine suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.46 | 92.3 | 4.46 | 83.3 | 4.46 | 87.5 | 4.46 | 100.0 | x |

| 37 | When a patient comes with acute UTI symptoms it is okay to prescribe antibiotics, despite of the negative result of a dipstick test [nitrites (-), leucocytes (-)]. A negative dipstick test is not a good predictor of absence of UTI† | 4.46 | 100.0 | 4.46 | 100.0 | 4.46 | 87.5 | 3.17 | 25.0 | |

| 38 | Leucocytes positive and nitrite negative result in a dipstick test indicates with high certainty bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.31 | 92.3 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 4.31 | 87.5 | 3.58 | 41.7 | |

| 39 | The single presence of smelly urine suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.31 | 84.7 | 3.92 | 75.0 | 4.00 | 75.0 | 4.31 | 83.4 | |

| 40 | The single presence of cloudy urine suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.31 | 84.7 | 3.75 | 66.7 | 4.31 | 87.5 | 4.31 | 83.4 | |

| 41 | A positive dipstick in the elderly without urinary tract symptoms is a strong indicator for urinary tract infection and requires antibiotics† | 4.31 | 92.3 | 4.31 | 83.4 | 4.31 | 100.0 | 3.67 | 50.0 | |

| 42 | The single presence of persistent urge to urinate suggests a high probability of bacterial infection and need of antibiotics† | 4.23 | 84.7 | 4.23 | 83.3 | 3.75 | 75.0 | 4.23 | 100.0 | |

| 43 | In an uncomplicated UTI, antibiotic treatment should be started as soon as possible to prevent the dissemination of the infection to the kidneys and bloodstream, independently of the risk of complication† | 4.23 | 84.7 | 4.23 | 83.3 | 4.23 | 87.5 | 4.23 | 91.7 | x |

| 44 | Cognitive changes (e.g. agitation, confusion) in the elderly suggest a high probability of bacterial infection and the need of antibiotics, even without the presence of urinary tract symptoms† | 4.00 | 84.7 | 4.08 | 75.0 | 4.00 | 87.5 | 3.75 | 58.3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).