Submitted:

14 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How should one construct a framework for sustainability learning in STEAM?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Justification for Case Study

- (a)

- Detailed descriptions must be obtained from immersion in the context of the case;

- (b)

- The case must be temporally and spatially bounded;

- (c)

- There must be frequent engagement between the case itself and the unit of analysis.

2.2. The Scope of a STEAM Case Study

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3.1. Data Source

2.3.2. Data Collection from B2B and B2C Sustainability Learning

2.3.3. Reliability and Validity of Qualitative Data

3. Results

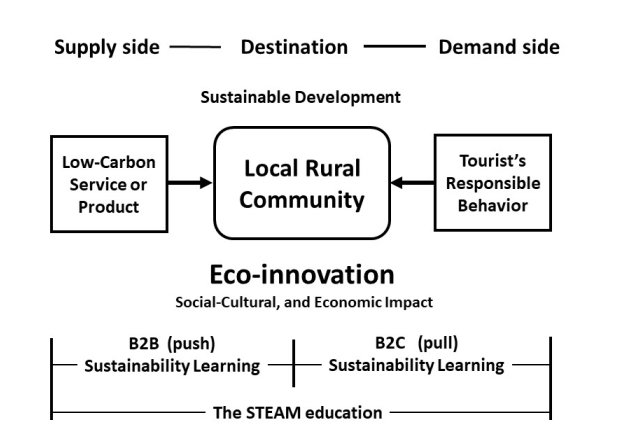

3.1. Destination: The Eco-innovation Strategy in Rural Development

3.1.1. The History and Problem of Wanlaun Township

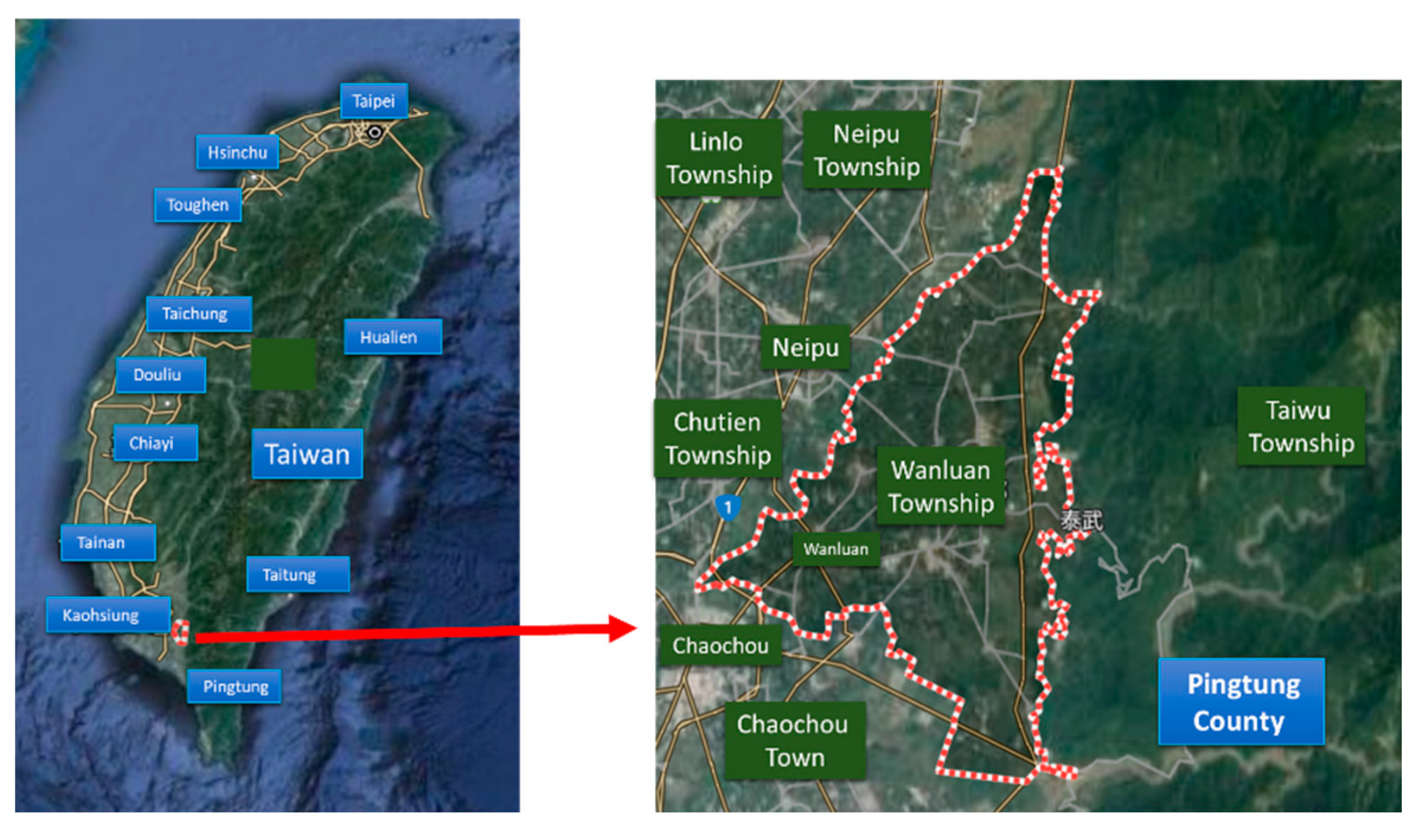

3.1.2. The Geographic Condition of Wanlaun Township

3.1.3. The Eco-innovation Strategy of Wanlaun Township

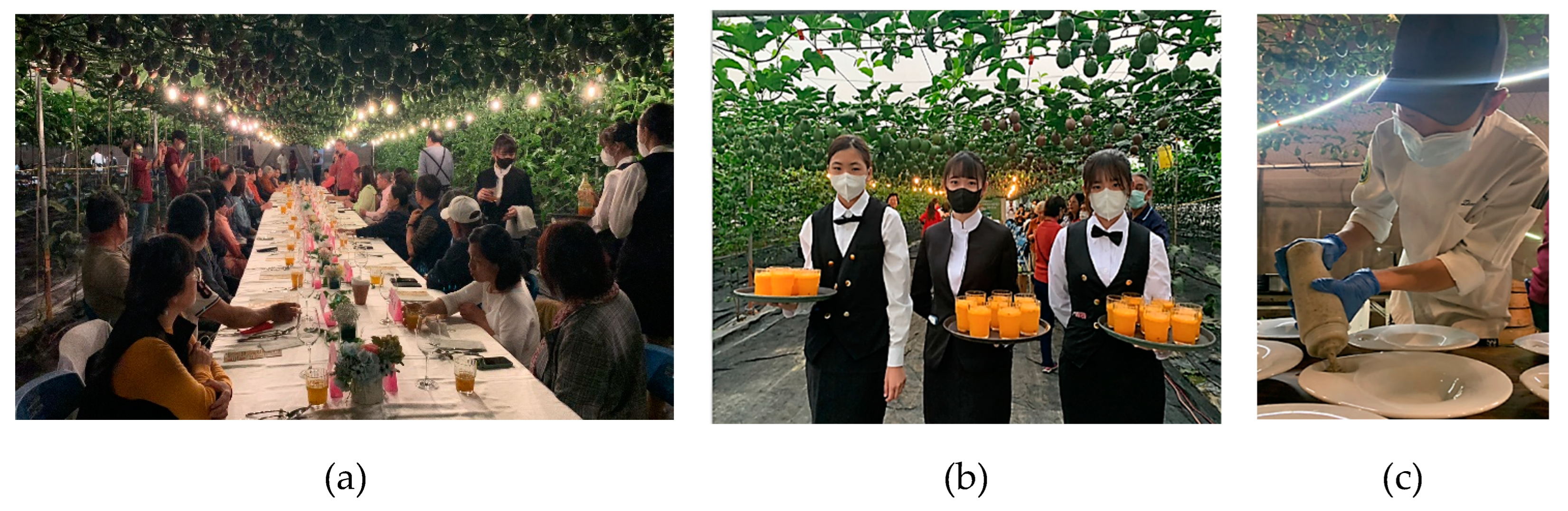

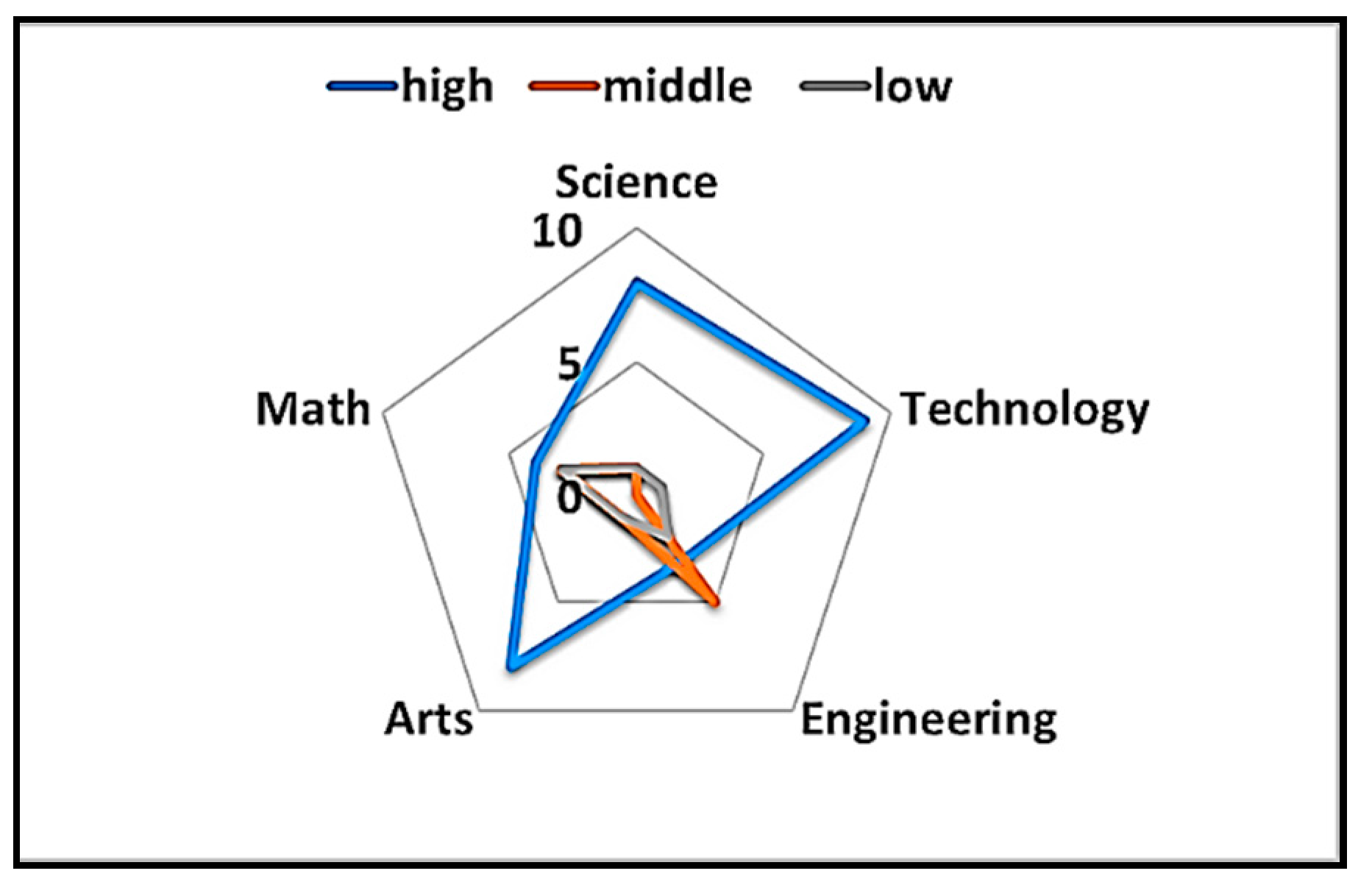

3.2. B2B Sustainability Learning: Farm-to-Table

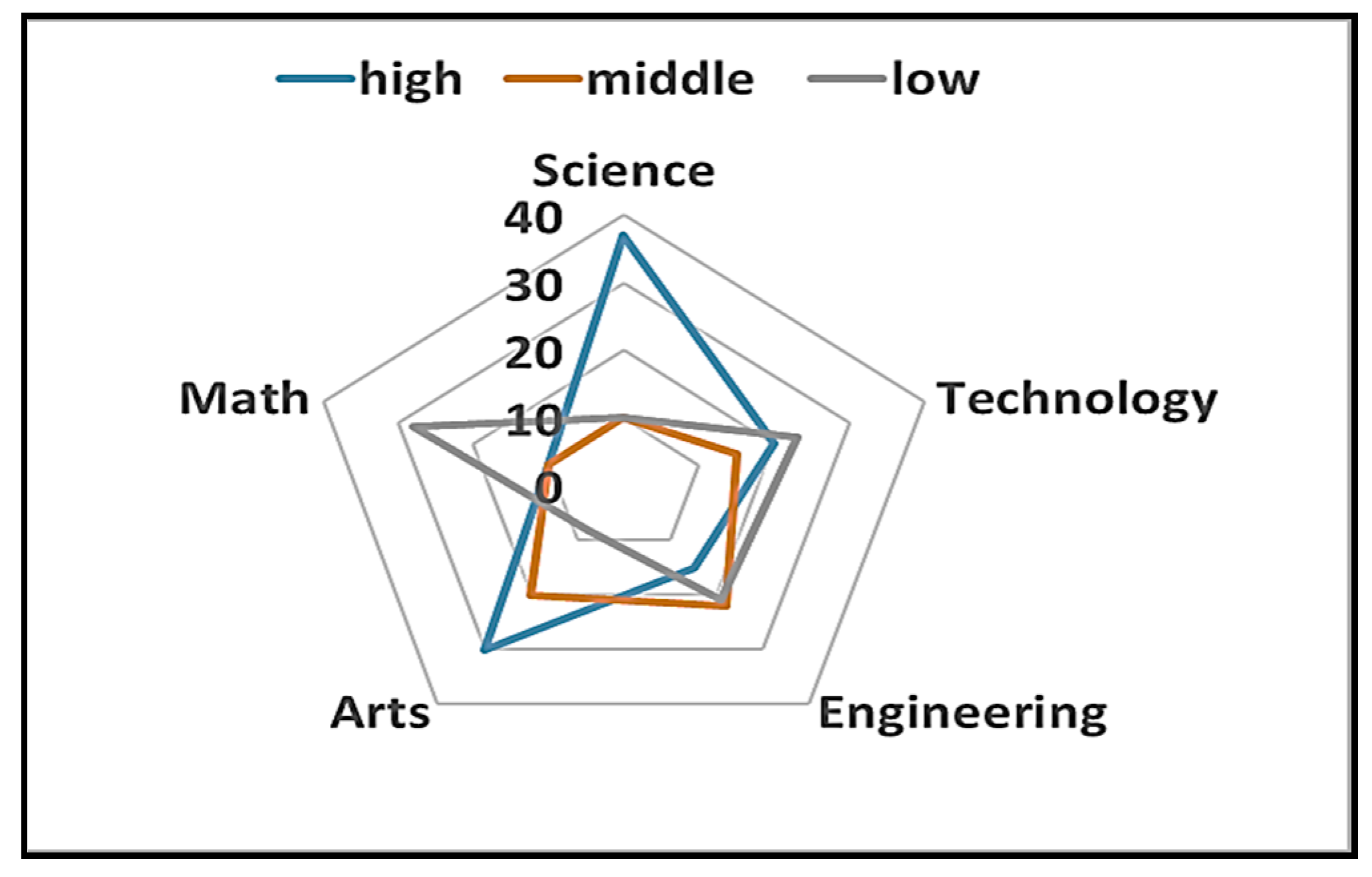

3.3. B2C Sustainability Learning: Self-Guided Travel to a Rural Community

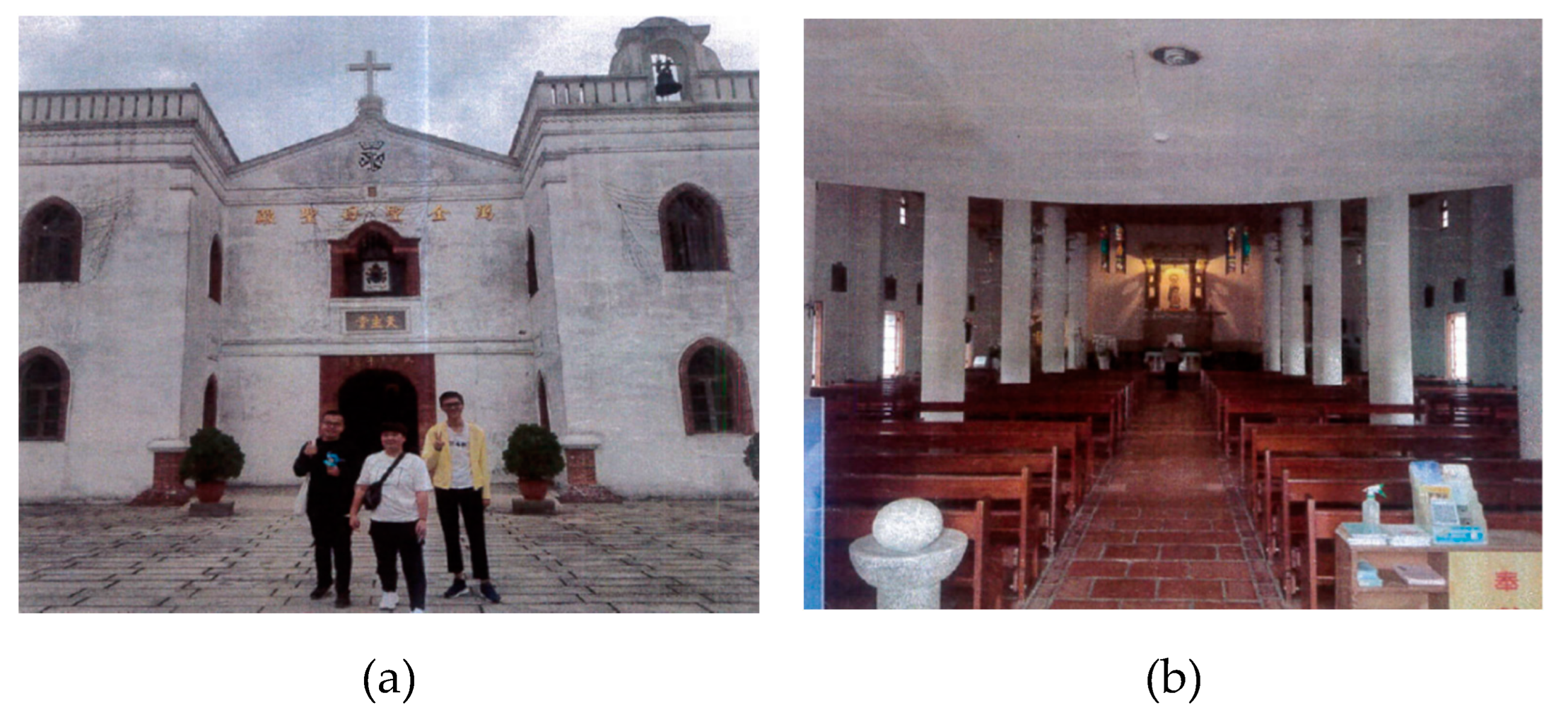

- Outside the building: We (the students) called this single-color church the “white house.” It has a lonely appearance, with small doors and windows. However, its appearance made us reflect on why a traditional architecture approach can make the building still live. The Catholic logo and official seal of the Qing dynasty looked ancient but nevertheless clear. These simple symbols appeared to embody a spirit in people‘s hearts. We thought that a person could live like this building; simply, but for a long time (stronger). The Catholic church has been through some disasters, such as fire, earthquake, and typhoon, but remains standing.

- Inside the building: We saw a wood carving of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This is an exquisite carving, with the face of a young girl. Although the wood is over 100 years old, the colors remain beautiful. The building inside was akin to an art gallery, with its church pews and ceiling artwork that remains clean and beautiful. Recently, the old building has been combined with new technology — a light show that takes place on Christmas Eve every year. The building fits the meaning of eco-innovation, namely that an “old building has new life.”

- The students asked the teacher “Is green eco-innovation? In rural areas, everywhere is green.” This was an example of incomplete critical thinking. Rural areas are subject to greening, but continue to need more greening engineering. The students recalled feeling somewhat nervous when they stood in front of the Columbarium Pagoda and took photos. However, they agreed that the pagoda has created a new style for traditional customs because, prior to the new building, the location was a mausoleum. According to Taiwanese custom, the mausoleums of ancestors should not be moved; however, the mausoleum has now been replaced by an architectural pyramid. The local government faced many objections to moving the mausoleum. However, the students saw that the pyramid fit the natural background and looked pleasing.

- The students also asked, “Is this a new strategy for rural marketing?” They said that they did not often travel to rural areas because they perceived such regions as dark. After the visit, they students saw that the region was clean and nice, and they showed the photos they took on social media. However, they were surprised that many people, especially younger people, tagged the posts, which the students believed reflection new attraction to Facebook users. They believed that the Life memorial Park was a nicer term than Columbarium Pagoda. The park beautified the living environment and calmed the heart and spirit.

3.4. STEAM within Sustainability Learning:

4. Discussion

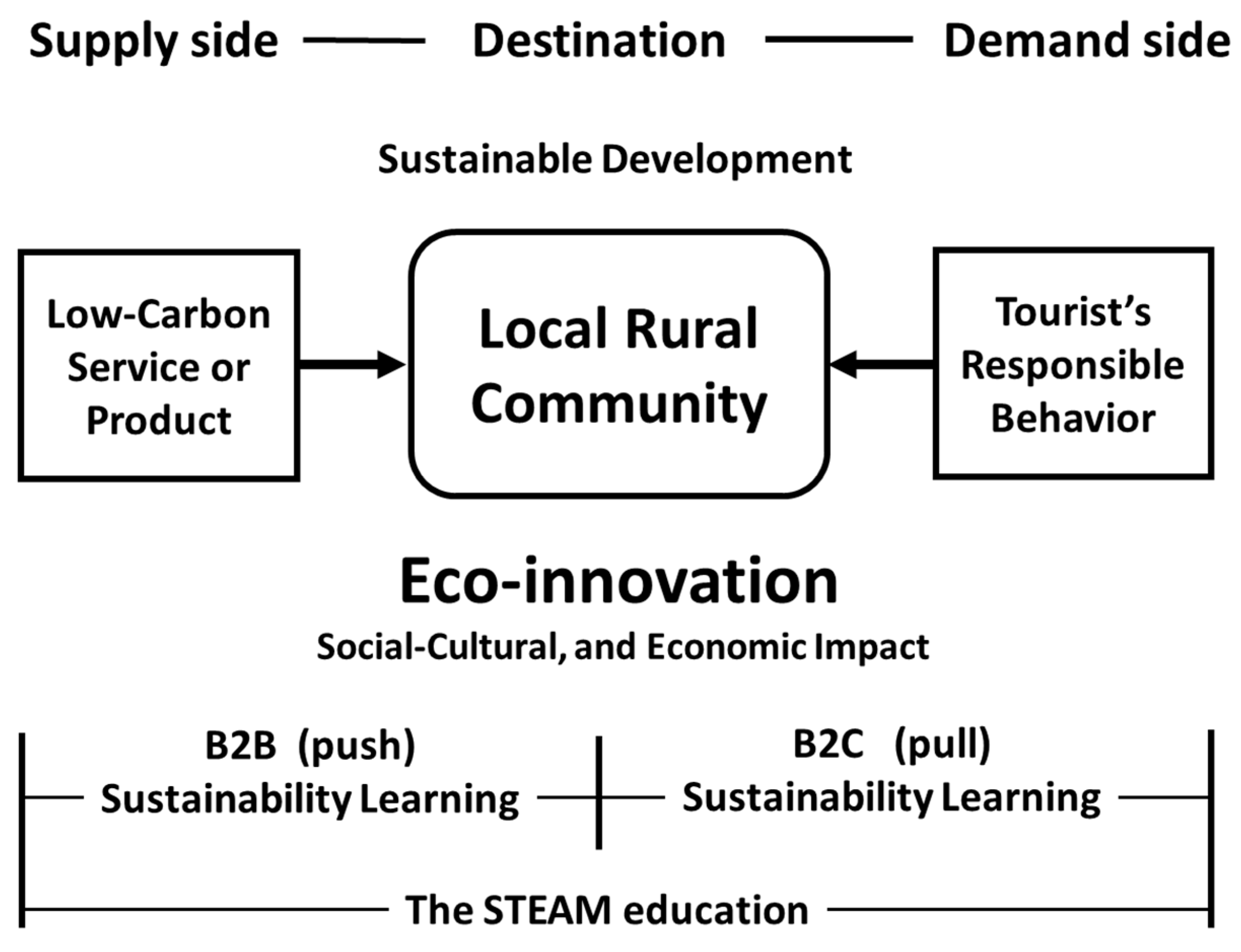

4.1. Sustainability Learning Framework for STEAM and Eco-Innovation

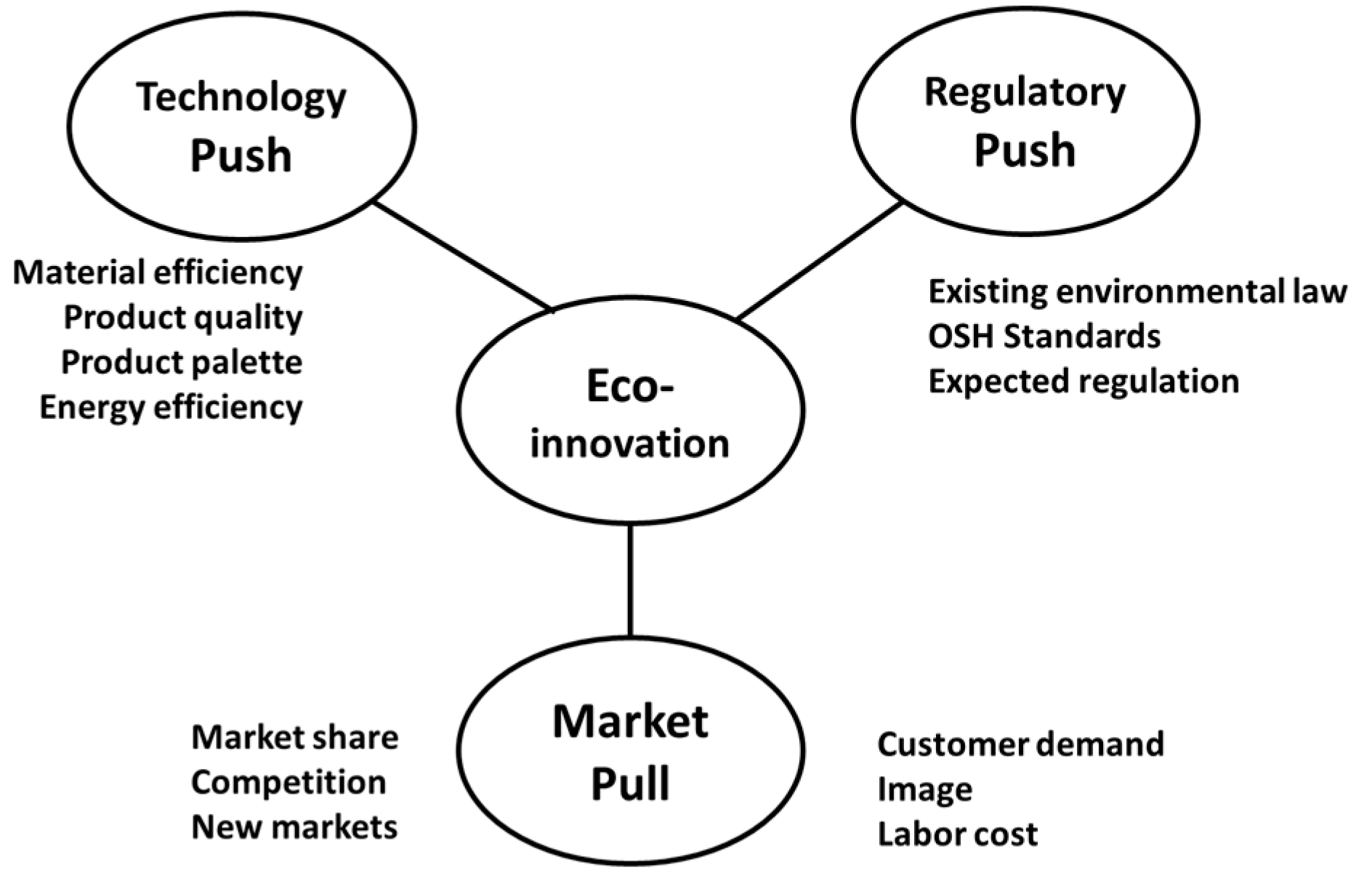

4.2. Eco-Innovation Theory “Push and Pull” can fit a Real Case of Situated Learning

4.3. Situated Learning Fosters Responsible Behavior and Reflection with Personal Authenticity

- Supply side (B2B sustainability learning): This form of learning represents a push. This component relates to providing low-carbon services or products for customers. This is complex because different stakeholders exist, such as the local government, small farms, the community, and outside customers. We found that the students worked together but they have had relative few prior social experiences; therefore, the students were shy when talking with farmers and customers. However, the students were interested in the organic approach to fruit farming. We further summarize this learning as follows:

- Situated learning fosters students’ responsible behavior because they must use teamwork to solve problems. With suitable pressure, students can grow to a greater extent, and in particular, they can experience personal authenticity associated with real-life interactions.

- Situated learning is not necessarily the best approach, as students’ performance is observed at specific times and places. However, with addition practice, students can slowly gain confidence. After engagement in situated learning, student’s potential thus be increased.

- Situated learning fostered some aspects of student cognitions, one of which was empathy for how hard farmers work farm. Consequently, the students were careful not to waste food materials in the classroom.

- Demand side (B2C sustainability learning): This learning component presented as a pull. The learning subject was self-guided travel in a rural community. This was chosen to provide students with a different perspective, namely that of a tourist. Another reason was to enhance cognitions regarding environmental conservation. We found that an important part of this this task was to ask (not force) students to become close to their local community. Most students live in or pass through their community, but they do not know any community history, even if they are residents. The travel task was therefore not only a trip to the countryside, but also an experience of local community that fostered knowing and understanding a place. We further summarize the outcomes of this task as follows:

- Situated learning fosters students’ responsible behavior because they see that the rural environment is green while simultaneously learning that greening the environment requires considerable effort and responsible behavior. In particular, irresponsible tourist behavior can create noise and garbage.

- Situated learning enhances personal life experiences; observation and touch can engender emotions that affect cognitions. The experience of historical heritage can enable one to understand its relationship to current lifestyles. For example, the understanding of how old buildings can continue to exist (Million Gold Mary Temple and Liou Family Ancestral Hall) involves comprehension of maintenance, recovery, and survival to today. Understanding this history fosters wisdom (accumulated experiences). A trip can engender changes in the individual [46], not only changed behavior but also changes in the mind.

- Situated learning illustrates that eco-innovation is not entirely focused on environmental engineering, but it also applies to cultural or social contexts. For example, the Catholic church is over 100 years old, but engenders the spirit of learning in STEAM because the building is relevant to science, technology, engineering, the arts, and math. Religion has components of architectural technology, recovery engineering, and Western science and art, all of which may relate to mathematics. Therefore, we can understand how the Columbarium Pagoda can change to a pyramid architecture and becoming part of eco-innovation.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. M., A. Eco-innovation–Towards a Taxonomy and a Theory. In Proceedings of Entrepreneurship and Innovation (Organizations, Institutions, Systems and Region), The 25th celebration DRUID conference, June 17-20, 2008.

- Díaz-García, C.; González-Moreno, A.; Sáez-Martíínez, F.J. Eco-innovation: insights from a literature review. Innovation 2015, 17, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva M, G.-G.; Piedra-Muñoz, L.; Galdeano-Gómez, F. Multidimensional Assessment of Eco-innovation Implementation: Evidence from Spanish Agri-food Sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus Pacheco, D.A.; Ten Caten, C.S.; Jung, C.F.; Ribeiro, J.LD.; Navas, H.V.; Cruz-Machado, V.A. Eco-innovation Determinants in Manufacturing SMEs: Systematic Review and Research Directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2277–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.-d.M.; Rocafort, A.; Borrajo, F. Shedding Light on Eco-Innovation in Tourism: A Critical Analysis. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.Y. Eco-innovation in hospitality research (1998-2018): a systematic review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 32, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, R. Redefining Innovation—Eco-innovation Research and The Contribution from Ecological Economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sally, G.; McMeekin, A. Eco-innovation Systems and Problem Sequences: The Contrasting Cases of US and Brazilian Biofuels. Ind. Innov. 2011, 18, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Dhamija, P.; Bryde, D.J.; Singh, R.K. Effect of eco-innovation on green supply chain management, circular economy capability, and performance of small and medium enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melek, Y.; Kazan, H. Effects of Eco-innovation on Economic and Environmental Performance: Evidence from Turkey’s Manufacturing Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3167. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, E. Eco-innovation for Environmental Sustainability: Concepts, Progress and Policies. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2010, 7, 267–290. [Google Scholar]

- Brunekreef, B.; Holgate, S. T. Air Pollution and Health. The Lancet 2002, 360, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaman, M.; Long, X. Rule of Law and CO2 Emissions: A Comparative Analysis Across 65 Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, L.B. Sears’ Repair of its Auto Service Image: Image Restoration Discourse in the Corporate Sector. Commun. Stud. 1995, 46, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, M.P. A Status-based Model of Market Competition. Am. J. Sociol. 1993, 98, 829–872. [Google Scholar]

- Rolf, W.; Bilharz, M. Green Energy Market Development in Germany: Effective Public Policy and Emerging Customer Demand. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen, K.; Meijers, F. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): Exploring Theoretical and Practical Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 188–207. [Google Scholar]

- Shulla, K.; Filho, W.L.; Lardjane, S.; Sommer, J.H.; Borgemeister, C. Sustainable development education in the context of the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federica, C.M.; Celone, A. SDGs and Innovation in the Business Context Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, Y.; Battisti, B.; Grimm, K. Achieving Transformative Sustainability Learning: Engaging Head, Hands and Heart. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.A.; Reder, L.M.; Simon, H.A. Situated Learning and Education. Educ. Res. 1996, 25, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Anne, P.T.; Oskamp, S. Relationships Among Ecologically Responsible Behaviors. J. Environ. Syst. 1984, 13, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald, E.H. The Role and Experience in Learning: Giving Meaning and Authenticity to the Learning Process in Schools. J. Technol. Educ. 2000, 11, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Georgette, Y.; Lee, H. Exploring the Exemplary STEAM education in the US as a Practical educational Framework for Korea. J. Korean Assoc. Sci. Educ. 2012, 32, 1072–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Safapour, E.; Kermanshachi, S.; Taneja, P. A Review of Nontraditional Teaching Methods: Flipped Classroom, Gamification, Case Study, Self-Learning, and Social Media. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlosky, J.; Rawson, K.A.; Marsh, E.J.; Nathan, M.J.; Willingham, D.T. Improving Students’ Learning with Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions from Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2013, 14, 4–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuichiro, A.; Simon, H.A. The Theory of Learning by Doing. Psychol. Rev. 1979, 86, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Sharan, M.B. The Case Study in Educational Research: A Review of Selected Literature. J. Educ. Thought 1985, 204–217. [Google Scholar]

- Helen, K.; Meijers, F. Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring Theoretical and Practical Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 188–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dzintra, I.; Badyanova, Y. A Case Study of ESD Implementation: Signs of Sustainable Leadership. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2014, 5, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Walter, A.I.; Stauffacher, M. Transdisciplinary Case Studies as A Means of Sustainability Learning: Historical Framework and Theory. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2006, 7, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaeys, F.; Oliveira, M.; Crissien, T.; Solano, D.; Suarez, A. State of the art of university social responsibility: a standardized model and compared self-diagnosis in Latin America. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2022, 36, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, A.D. Validity and Reliability in Social Science Research. Educ. Res. Perspect. 2011, 38, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rob, V.; Khan, S. Redefining Case Study. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2007, 6, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, P.S.; Christakis, N.A. Social Networks and Health. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2008, 34, 405–429. [Google Scholar]

- Jesionkowska, J.; Wild, F.; Deval, Y. Active Learning Augmented Reality for STEAM Education—A Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejias, S.; Thompson, N.; Sedas, R.M.; Rosin, M.; Soep, E.; Peppler, K.; Roche, J.; Wong, J.; Hurley, M.; Bell, P.; et al. The trouble with STEAM and why we use it anyway. Sci. Educ. 2021, 105, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhari, A.A. ; King Abdulaziz University Universities‟ Social Responsibility (USR) and Sustainable Development: A Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 4, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.K.; Yoels, W.C. The College Classroom: Some Observations on the Meanings of Student Participation. Sociol. Soc. Res. 1976, 60, 421–439. [Google Scholar]

- Lobe, B.; Morgan, D.; Hoffman, K.A. Qualitative Data Collection in an Era of Social Distancing. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J.J.; Boeije, H.R. Data Collection, Primary Versus Secondary. Encycl. Soc. Meas. 2005, 593–599. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, H.; Heale, R. Triangulation in Research, with Examples. Evid. -Based Nurs. 2019, 22, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanlaun Township Office Website. Available online: https://www.pthg.gov.tw/townwlt/Default.aspx (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Soil and Water Conservation Bureau Website. Available online: https://www.swcb.gov.tw/Home/eng/ (accessed on 02 July 2023).

- Lipiäinen, S.; Kuparinen, K.; Sermyagina, E.; Vakkilainen, E. Pulp and paper industry in energy transition: Towards energy-efficient and low carbon operation in Finland and Sweden. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, C. This Trip Really Changed Me: Backpackers’ Narratives of Self-Change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Antonucci, F.; Pallottino, F.; Aguzzi, J.; Sarriá, D.; Menesatti, P. A Review on Agri-food Supply Chain Traceability by Means of RFID Technology. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, D.; Wood, L.; Harding, A. Using Radar Charts with Qualitative Evaluation: Techniques to Assess Change in Blended Learning. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, P.; Shen, J.; Sun, H. Reviewing assessment of student learning in interdisciplinary STEM education. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2020, 7, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G. Societal transformation in response to global environmental change: A review of emerging concepts. AMBIO 2015, 44, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.locale=en (accessed on 05 July 2023).

- Tsai, K.-H.; Liao, Y.-C. Innovation Capacity and the Implementation of Eco-innovation: Toward a Contingency Perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attractions | Travel Experiences and their Eco-Innovation Meaning |

|---|---|

| Million Gold Mary Temple | This Catholic temple was built 1860. It is the residents’ religious center but also an example of live heritage because the building used local materials such as honey, lime, unrefined sugar, and soil mixed together. Although, it has been damaged several times, it remains standing in its original location. The eco-innovation meaning is that an old building has a new function (education) and represents a local cultural-social attraction. |

| Liou Family Ancestral Hall | The building was constructed in 1864 and is occupied by descendants of the original inhabitants. The building is located at the front of a traditional Hakka settlement because the occupants, the Liou family, had a good reputation and were wealthy at that point in time. In particular, the building has a rich Chinese cultural heritage and arts. The students saw Chinese feng shui in the design. For example, the river flowing in front of house represents wealth and protection from external forces. The eco-innovation meaning is wisdom, as the building was designed in harmony with nature, without damaging the environment. The old building is not only a residence but also has new function for the cultural trip. |

| Life Memorial Park (Columbarium Pagoda) | The park was built in 2019. It has a special place in Taiwanese culture. As most Taiwanese people revere their ancestry, many people are unwilling to support change. However, this problem was overcome, and the park was constructed, including two pyramids. Younger people frequently visit the park to take photos. The eco-innovation meaning is effective use of land, and making the landscape more beautiful and friendly. |

| Kulaluce Tribe (Permanent House the for Typhoon Morakot Disaster) | Typhoon Morakot caused massive damage in southern Taiwan in August 2009. After the disaster, the indigenous people were moved to this location to begin a new life. The Permanent House was built in a traditional cultural style, and has become a popular park that promotes high sea-level coffee. The eco-innovation meaning is re-construction, cultural conservation, and the production of high-quality coffee. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).