1. Introduction

Palm oil is extracted from the mesocarp (flesh) and endosperm (kernel) of the fruits of the oil palm tree (

Elaeis guineensis Jacq.), which is native to West and Central Africa. Palm oil has a high content of saturated fatty acids, which makes it suitable for frying and baking, as well as for producing margarine, soap, detergents, cosmetics, and biofuels. Palm kernel oil, which is extracted from the kernel, is mainly used for soap making and other industrial purposes [

1]. Palm oil is an essential multipurpose raw material for both food and non-food industries. It is estimated that for every Nigerian household of five, about two liters of palm oil is consumed weekly for cooking [

2]. It has also been shown from the 2008 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey that one out of every two households (54%) in the country and four out of five (80%) households in the Centre Region used palm oil in food preparations [

3]. Small-scale palm oil processing has been shown to be profitable and can also be a source of employment. [

4].

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global palm oil production reached 71 million tonnes in 2018, accounting for 37% of the total vegetable oil output. The demand for palm oil has rapidly increased owing to its positive health impacts such as improving brain health, decreasing cholesterol levels, reducing oxidative stress, and improving hair and skin health [

5].

Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand currently contribute over 85% to the global supply of palm oil [

6]. Other major producers include Colombia, Nigeria, and Ecuador. Africa as a whole produced 6.3 million tonnes of palm oil in 2018, representing 9% of the global production [

7].

The scale of palm oil production in Africa ranges from subsistence production for use within farm families to industrial production, as is the case with the Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC), PAMOL Plantations PLC, and ‘Société Camerounaise de Palmeraies’ (SOCAPALM), among others. Other authors have divided palm oil production into two main categories, namely, industrial and non–industrial. Industrial production refers to large-scale plantations (>1000 ha) that are owned or managed by multinational corporations or national companies that use modern technologies and inputs to maximize yields and profits, whereas nonindustrial production refers to small- (<10 ha) and medium-scale (10–1000 ha) plantations that are owned or managed by individual farmers or cooperatives that use traditional or semi modern methods and inputs to produce palm oil for subsistence or local markets [

8]. The state of Cameroon classifies nonindustrial operators in farm sectors as smallholders. In the palm oil production sector, smallholders abound and contribute significantly to meeting the national palm oil needs of the country. However, their characteristics remain largely undertaken.

Awere et al. [

3] observed the need for the treatment of wastewater produced from palm oil processing activities before disposal. They proposed the exploration of treatment technologies that could achieve recovery of resources (e.g., biogas, compost, and earthworm biomass) and fit into the framework of the circular economy.

The characterisation of palm oil production is essential to guide government and international policies more effectively. For instance, the understanding of demographic characteristics will provide information on how to direct innovations in agriculture. It has been shown that demographic characteristics play a key role in technology adoption in the corn sector [

9] and the Ricinodendron heudelotii sector in South Cameroon [

10]. How these characteristics play out in the oil palm sector in Cameroon is yet to be studied. A major challenge in economies dependent on agriculture is that investments typically do not make commensurate returns. This is especially true in sectors such as the oil palm with long juvenile phases. The understanding of the production, processing, labour, and other cultural characteristics of this sector is essential to better direct resources. It will guide investors in the sector on where to pay more attention. For instance, Ayompe et al. [

11] used an econometric approach to show that there are better profits for investors in selling crude palm oil than for those who market fresh fruit bunches (FFBs). Similar studies in the oil palm sector are rare.

Deforestation, soil erosion, water contamination, noise and air pollution, and others, which are inevitable consequences, have all been linked to palm oil production and processing [

12,

13]. In Cameroon, these impacts have not received sufficient attention, especially in the smallholder sector. It is essential therefore to comprehensively characterise the smallholder oil palm sector in Cameroon so that policy makers can direct resources on areas that would stimulate growth and enhance the relationship between rural communities hosting such palm oil processing units, and the smallholder palm oil mills. In this research, we aimed at filling this gap, and the findings are significant for the valorisation of smallholders’ efforts in the sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reconnaissance survey and ethical clearance

A reconnaissance survey was first carried out to familiarise ourselves with the sites and identify the key actors in the sector. This required meetings with the regional representatives of Agriculture and Rural Development for the Littoral and Centre Regions, where information on the nature and organisation of smallholder oil palm plantations was obtained. Key respondents were also identified at this stage to act as contact points and guides during the actual survey. Thereafter, visits were made to the different subdivisions in the two regions where oil palm activity is most intensive, and from the findings of these visits, the sites were selected. Then, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (UBIACUC) of the University of Buea, Cameroon, which is the authority for issuing clearances for research of this nature in the South west Region of Cameroon.

2.2. Study site

The study was carried out in the Centre and Littoral regions of Cameroon. In the Centre Region, the areas covered included Sombo Village, Sombo Centre, and Nyachou-Pesupal. In the Littoral Region, Fiko (Bonalea subdivision) and Nkapa (Dibombari subdivision) of Mungo were covered (

Figure 1). The sites selected are known centres of smallholder oil palm cultivation in Cameroon. The Centre Region falls within Cameroons humid equatorial agroecological zone V with bimodal rainfall, whereas the Littoral Region falls within agroecological zone IV, which is a humid equatorial zone with monomodal rainfall. The natural vegetation in both zones is tropical forests, with mangroves along the coastlines and riparian fringes. Agriculture is the dominant activity of the inhabitants of the hinterlands in both areas, and the major plantation crop for smallholders is the oil palm.

2.3. Population and sample size

The study population comprised smallholder farmers in the oil palm sector in the Centre and Littoral Regions of Cameroon. On the basis of accessibility, samples were drawn from the five sites that are cited above. A total of 45 respondents were selected for this study on the basis of the size of their plantations (small scale, <5 ha; medium scale, 5–1000 ha) and their proximity to forests (forest edge, <1 km; non-forest edge, >1 km).

2.4. Methods

Mixed-methods research approaches were applied in this study. Semi structured questionnaires were administered to 45 respondents selected on the basis of the criteria cited in

Section 2.3. The major items of the questionnaire included demographics, oil palm plantations, palm oil processing, land tenure, yield and income, labour and inputs, market access and prices, environmental awareness and practices, and perceived opportunities and constraints.

Observations and ethnography were used to identify and record aspects that would not be covered sufficiently by the items, for instance, modes of disposal of palm oil mill wastes and the different methods of oil processing and storage. Informed consent was obtained from the respondents prior to administering the questionnaire. The 45 respondents all of them completed the questionnaires thus obtaining a response rate of 100%.

Secondary data were obtained by desktop research on palm oil production publications in the University of Buea Library, the FAO statistics yearbook for 2020, and other scientific publications listed in the references.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The data generated from the questionnaire were encoded in SPSS Version 21, by binary coding. The data were checked for integrity by outlier analysis and missing value analysis. Subsequently, exploratory descriptive analyses were conducted to identify underlying patterns. Spearman rank correlation analysis was conducted to find relationships between demographic and non–demographic variables and factor analysis was carried out to determine special associations between the variables, on the basis of their correlations. Where necessary, analyses were conducted at α = 0.05.

4. Discussion

This study revealed that the smallholder oil palm sector in Cameroon is dominated by adult males, mostly married with a significant household size. These characteristics could in part be expected because this is the age bracket of responsibility, wherein the needs of life and family challenges require the men to provide. Cultural aspects are also in play here, especially when it concerns land tenure systems, which culturally favour males over females. The oil palm agribusiness, being land-intensive, requires somebody with access to land to establish, and males fit this profile, as reported by de Vos and Delabre [

14] and Mehraban et al. [

15]. Indeed, cultural land tenure systems in Cameroon favour men over women in terms of ownership inheritance of land, and our findings corroborate those of Fonjong and Gyapong [

16], and suggest that for the most part, the smallholder oil palm plantation sector in Cameroon will remain male-dominated for quite a while. Our findings also hold promise for increasing gender diversification in the sector, considering the significant as though but not dominant proportion (35.6%) of female participation in the smallholder oil palm sector. Ayompe et al. [

11] have shown that in Cameroon, land ownership is an important parameter that determines profitability in the oil palm sector. A significant demographic finding of note is that a majority of the respondents have attained at most secondary school education. Typically, the less educated find themselves employed in agriculture, which is actually a very knowledge-intensive sector. This is especially challenging where there is a need for comprehension of deeper issues such as how the sector affects the environment, access to finances, and adoption of innovations, consistent with the findings of Harvey et al. [

17]. Subsequently, we attempt to assess the relationship of demographic strata with oil palm production and processing variables.

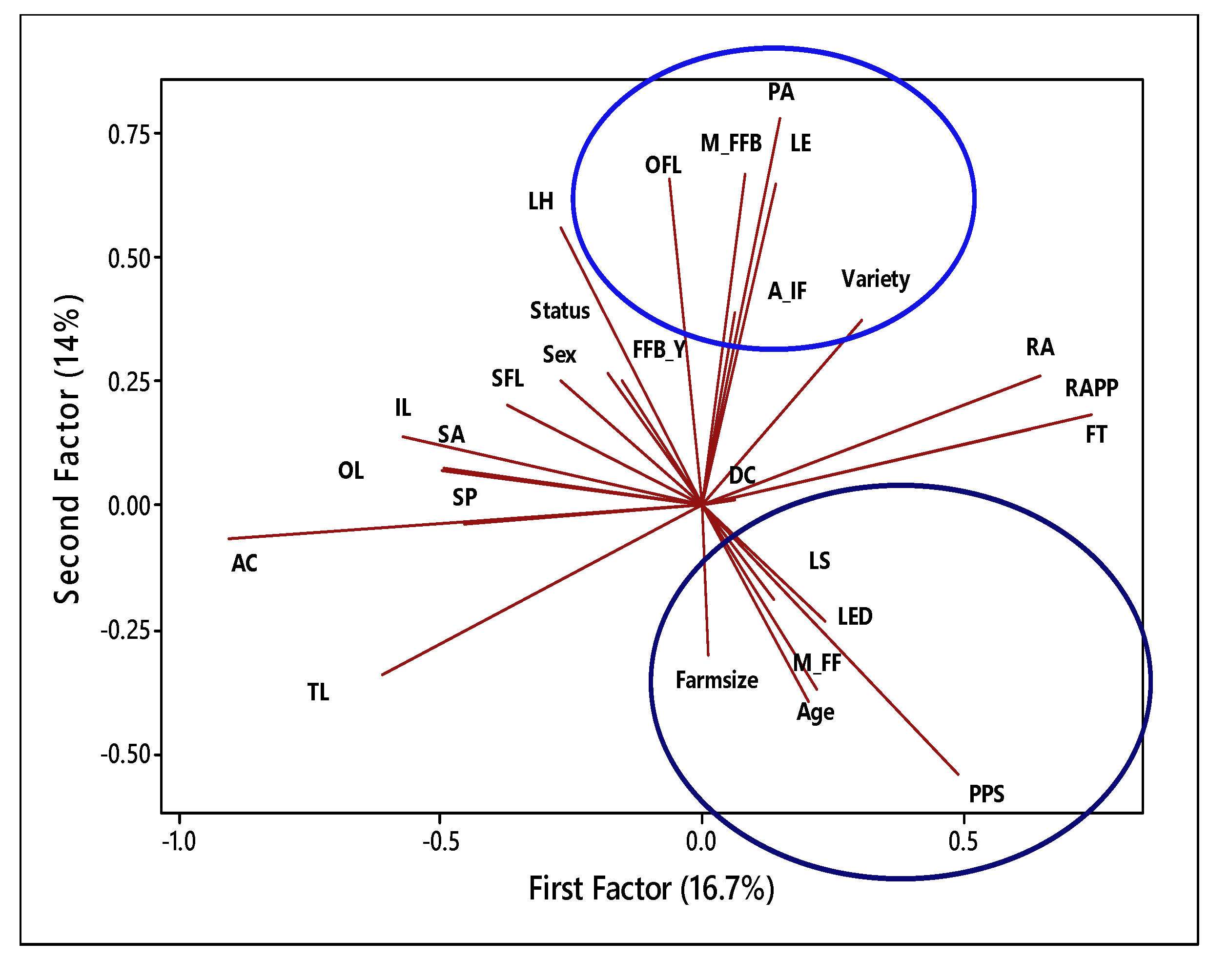

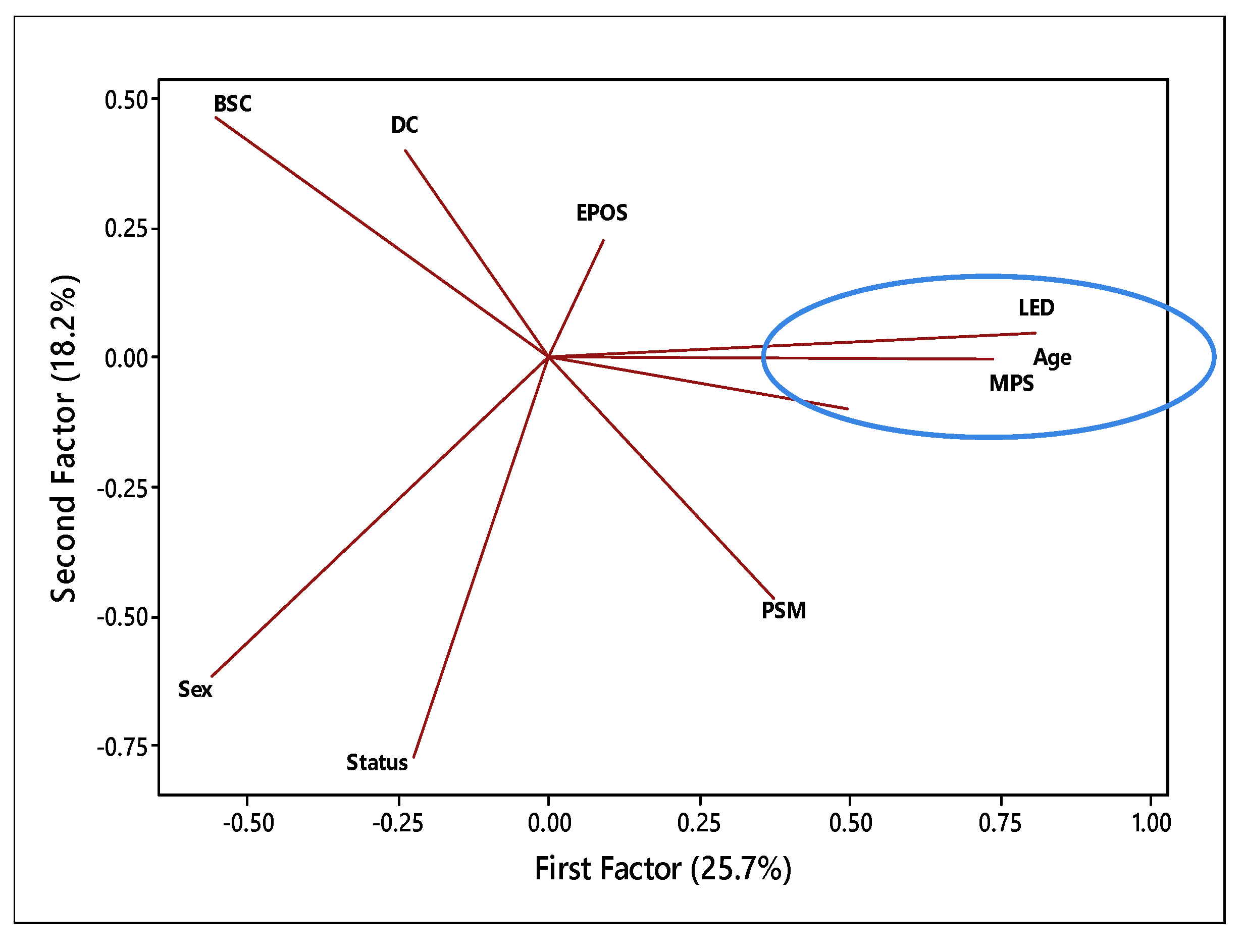

Most smallholders in the oil palm sector in Cameroon have over 21 years of farming experience, which is correlated with their appropriate variety selection and knowledge of key parameters, such as when to plant in new fields, the economic lifespan of the plantations, pruning frequencies, and perception of farm-related risks among other technical considerations raised. Fosso and Nanfosso [

9] have shown that farmers’ age, education, and farm sizes are key determinants in the adoption of agricultural innovations in the West Region of Cameroon, which is consistent with the findings of Mbosso et al. [

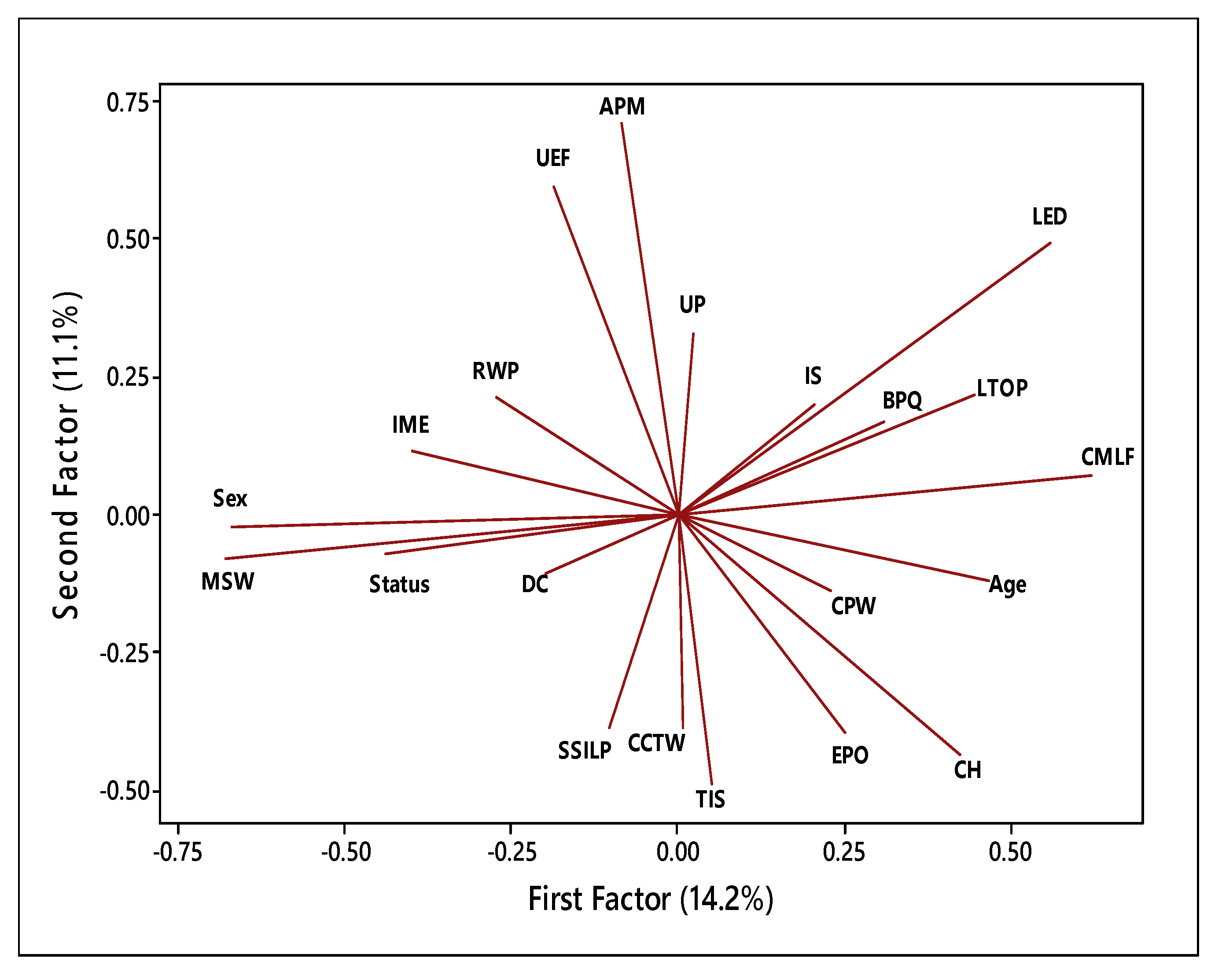

10] in Southern Cameroon. Indeed, factor analyses of the correlation matrix in terms of oil palm production characteristics in the study sites indicates that the farmers’ level of education, level of experience in the farm, and farmers’ age are key determinants of access to farm finances, production per season, and labour safety in the plantations.

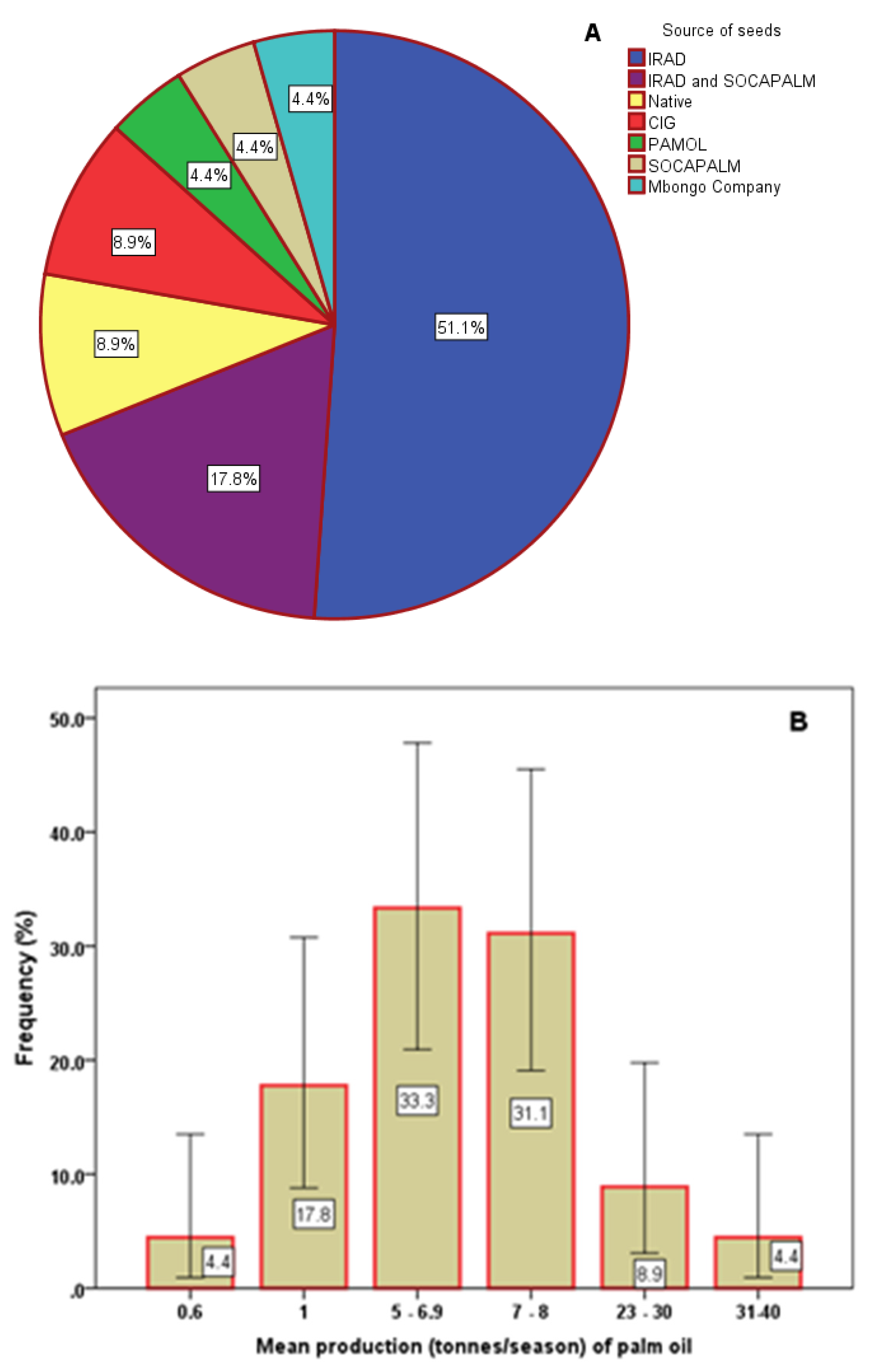

State research institutions and parastatal oil palm production enterprises are pre-eminent to the survival of small-scale oil palm producers in the study sites; IRAD, SOCAPALM, and PAMOL jointly provide over 75% of the seeds for plantation establishment by smallholders. Our study suggests a need for continued state support for the oil palm sector and shows that the state has been instrumental in some way to the growth observed in the sector. Improved palm seeds are expensive compared with the palm oil output per season. It is clear that few smallholders have the capacity for high palm oil output, but cost considerations of improved seeds could be an issue as is the case with other innovations [

10]. Indeed, our findings indicate that a majority of the respondents experience a limited output, which they attribute to the lack of finances, failure to apply fertilizers, and failure to prune palm trees. The latter could be in some way related back to the lack of finances for the sector.

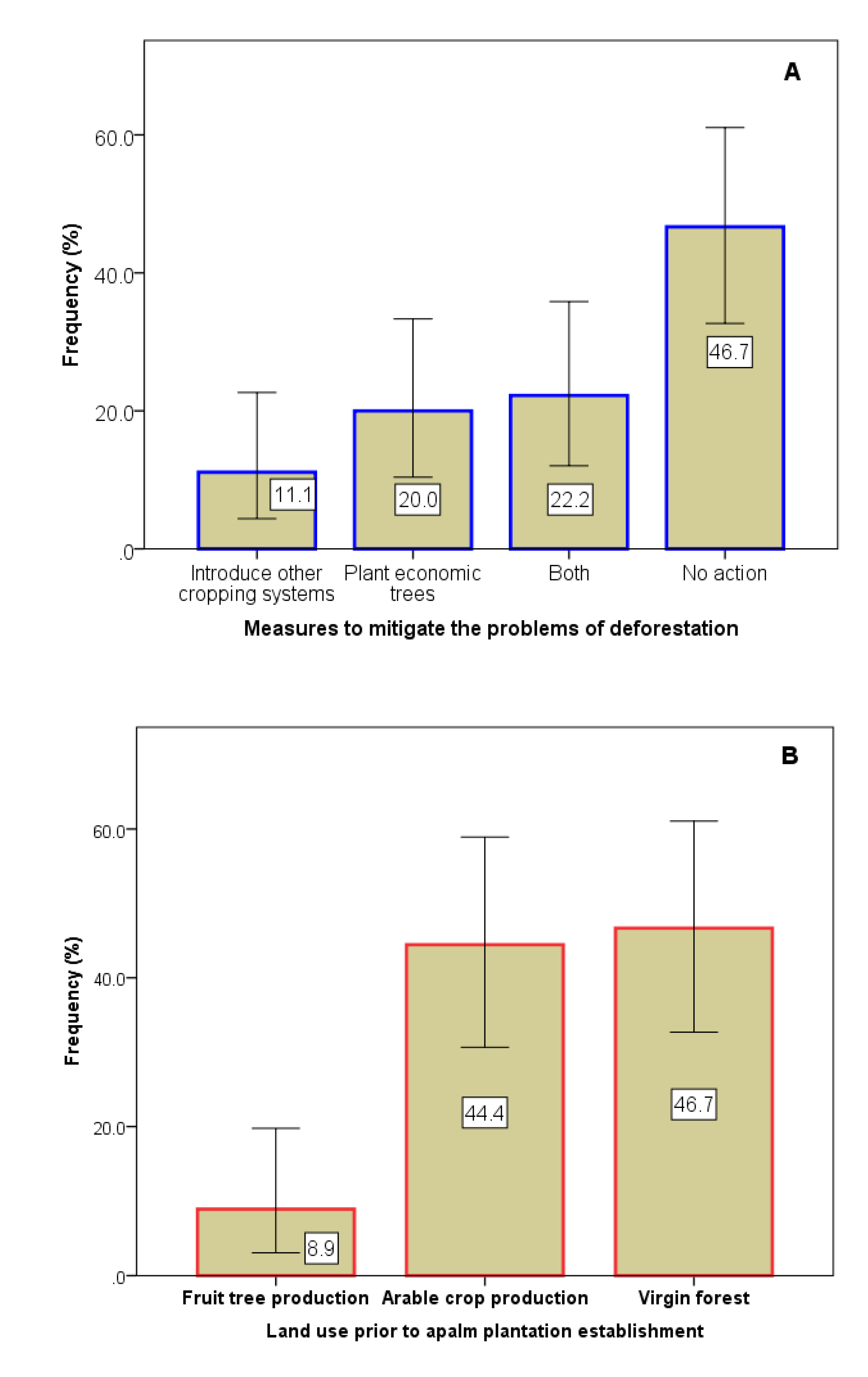

In the production chain for oil palm, deforestation is always present; distribution of land uses prior to plantation establishment shows that about 47% of smallholder oil palm plantations surveyed have replaced pristine forests. Land clearing is an indispensable step in oil palm plantation establishment because the seedlings are poor competitors for light (if shaded) and nutrients (if crowded with weeds or other plants). Alternative planting solutions that do not involve deforestation are rare. The FAO suggests that oil palm contributes 5% to tropical deforestation, whereas the European Commission revealed that oil palm contributes 2.3% to global deforestation. The negative effects of tropical deforestation on climate change, water resources, soil erosion, and public health have been well established e.g., Lawrence et al. [

18]. The dominant proposed measure in the face of deforestation is mitigation, and our findings show that over one-third of the respondents mitigate deforestation by planting economic trees and adopting cropping systems that could act as net sinks for carbon; this is a popular solution in the face of deforestation and climate change [

19].

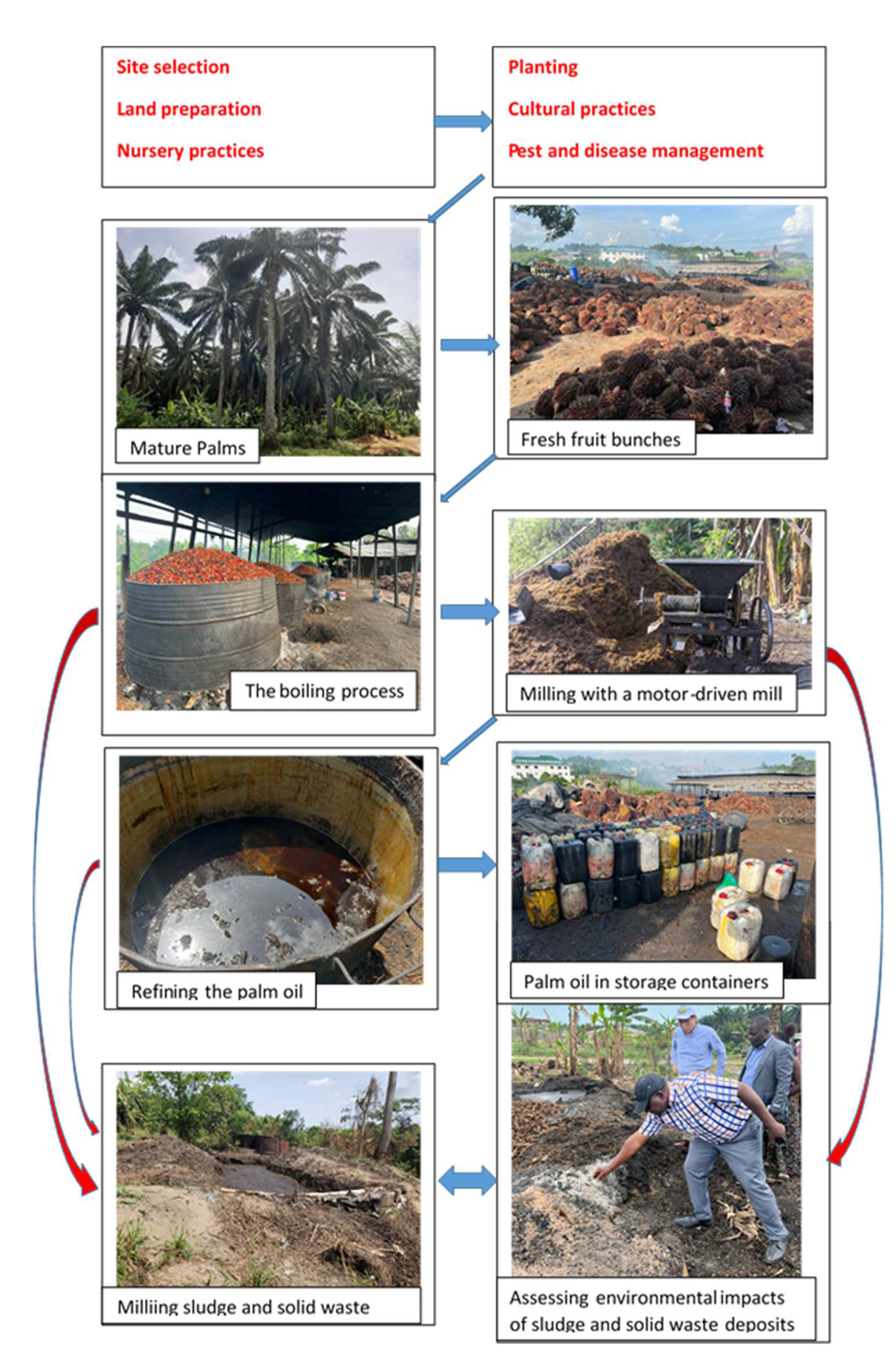

Palm oil processing is a key step for up–scaling profits from the enterprise, as sales of crude palm oil earn far more profits than that of FFBs [

11]. Like all other crops, processing adds value to the produce and crude palm oil sells for more because it has multiple uses – in culinary, cosmetic, chemical and confectionary industries, just to name a few. Through this survey, we have ascertained the state of smallholder processing in the study sites, which are artisanal at best. Although the farmers demonstrate deep knowledge of the milling process, they report the that lack of finances remains a key challenge in the sector. The cost of acquiring an artisanal mill of reasonable capacity is high, and so the adoption rate of innovations in this regard has been low, consistent with the findings of Mbosso et al. [

10].

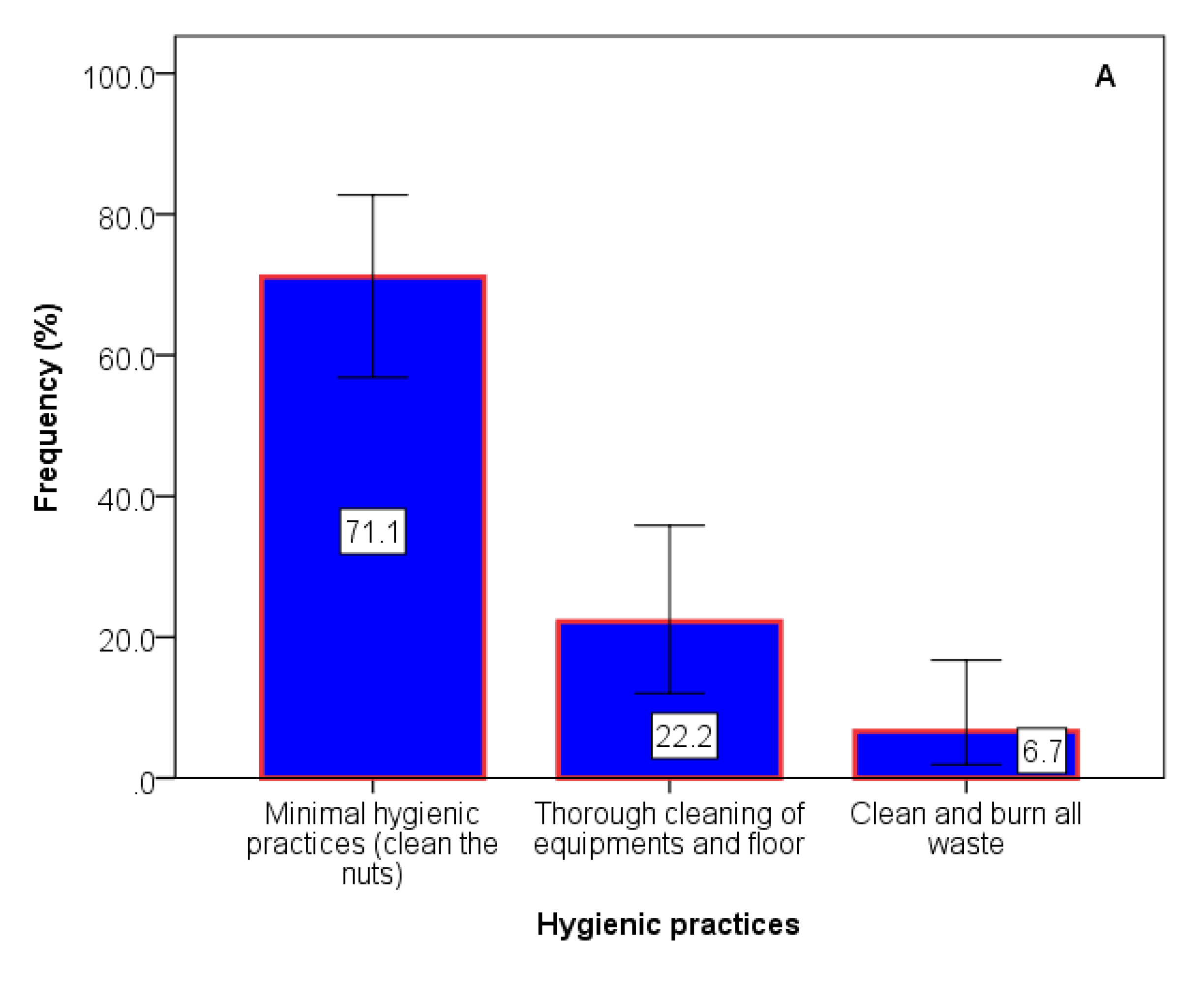

During processing, some hygiene and health considerations are necessary. The oil palm sector is fraught with health hazards that range from possible accidents and physiological diseases. This is due to exposure to agrochemicals especially herbicides, heat shock, and burns during milling processes as well as musculoskeletal injuries from lifting heavy weights in the course of palm oil packaging and storage. This is consistent with the findings of Mayzabella et al. [

20]. Our findings indicate that a majority of the respondents clean their nuts to a certain degree before processing, but this is challenging especially in larger–scale smallholdings. Another consideration is the treatment of the milling effluent, which can be the breeding ground of disease vectors such as the Anopheles mosquitoes that transmit the malaria parasite. Such a treatment would reduce malaria incidence among the workers and surrounding inhabitants. To prevent health–related complications from the palm plantation work, workers drink extracts of V. amygdalina and C. papaya leaves with milk, practice worker rotation, and wear protective clothing. Extracts of

V. amygdalina and

C. papaya are popular ethnomedicines in most parts of Africa, known for their efficacy against malaria, hypertension, diabetes, and other health conditions [

21,

22]. However, workers (75.6%) still become ill, and when this happens, a majority of them have to pay their own bills. There is little or no social security in the smallholder plantation sector in Cameroon. Nationwide, the use of health insurance is not mandated, and existing schemes are still in their infancy. There is little support for smallholders for promoting hygiene, and correlation analysis revealed that if this support were provided, health risks would be minimised.

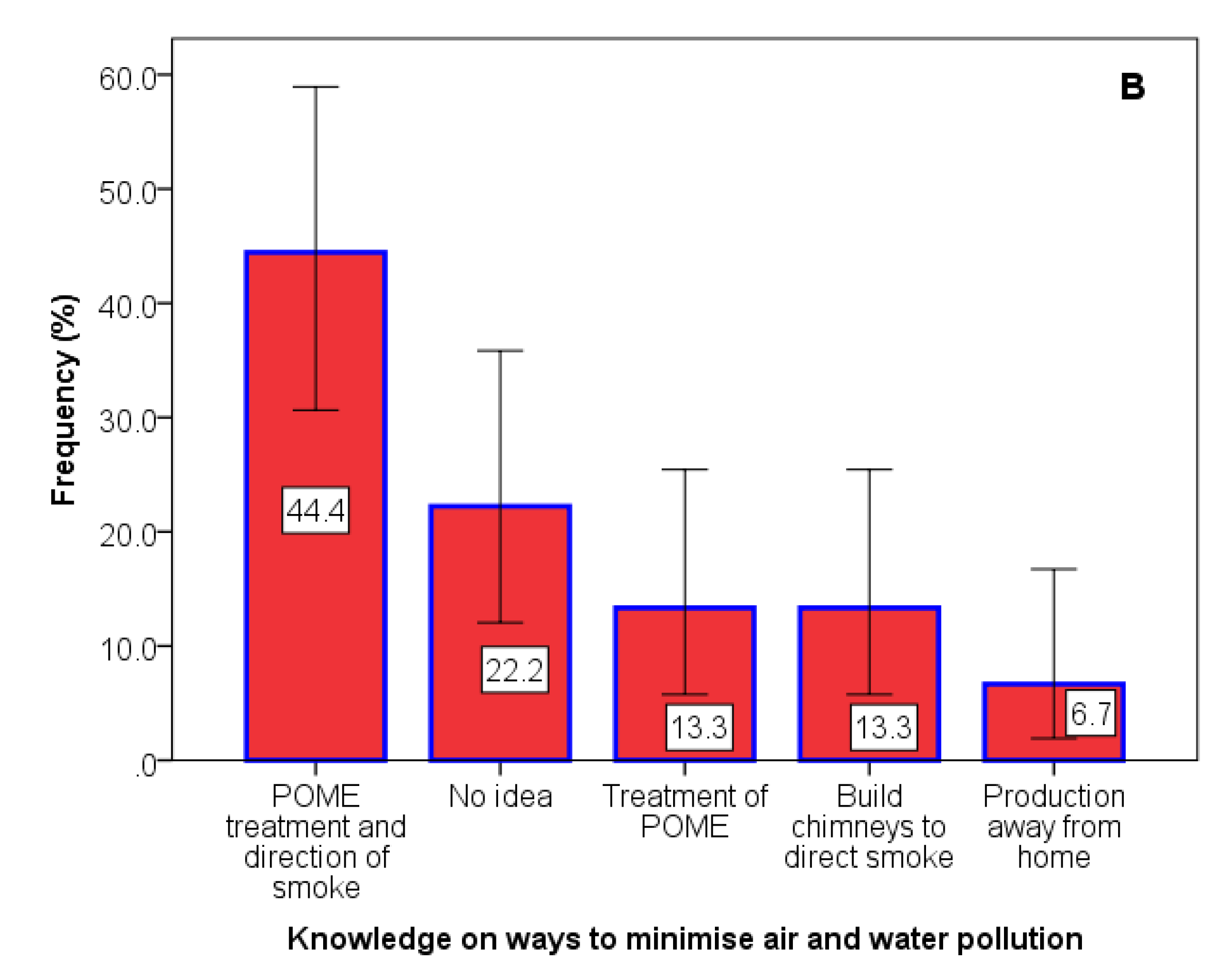

Plastic containers of various sizes are used to store crude palm oil and farmers mainly consider their ease of use and the lack of possible rust contamination as the criteria for selecting them. Other considerations include avoiding spoilage during storage through regular monitoring, and this depends directly on the age of the farmer and the level of education, consistent with the findings of Fosso and Nanfosso [

9] on the importance of these demographics in the farming sector.

Management of waste from palm oil production operations is essential for neighbours to accept these artisanal mills within their vicinities. This is an issue of concern in several other countries where palm oil is produced. Deforestation, solid waste disposal, palm oil mill effluent, the related odour pollution, and others are notes in the study sites, prompting most neighbours to complain at least sometimes. Qaim et al. [

23] reported similar findings in a review of works from several Asian countries. Similar findings have been reported across several plantations in East Kalimantan [

24], which these point to the fact that at the artisanal level, smallholders usually lack the financial and technological needs for effective palm oil waste management, waste valorization, or palm oil mill effluent disposal are beyond the financial means of the smallholders. Most smallholder oil palm farmers reported that they lack access to both formal and informal financing.

The main essence of oil palm plantations is the production of crude palm oil, either for direct domestic use or for further processing in industries. Therefore, minimis production and processing losses is essential. Our findings have revealed various factors that decrease oil yield, including the quantity of water used, mill capacity, the production season, fermentation duration, boiling duration, and temperature. Efficient management of these processes is directly related to the farmers experience and level of education. There were strong negative correlations between factors affecting palm oil yield and the adoption of innovations to increase yield, and between the adoption of methods to manage palm oil processing and most common production losses. This further highlights the importance of demographics in postharvest yield and losses [

25].

Author Contributions

L.M.N: conceptualization, questionnaire design, methodology, field sampling work, data sorting, formal analysis of data, presentation and interpretation of results, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing; G.A.A.: conceptualization, questionnaire design, methodology, field sampling work, investigation, interpretation of results and writing—review; R.N.N: conceptualization, questionnaire design, methodology, field sampling work, investigation and writing—review; K.M.: conceptualization, questionnaire design, field sampling work and writing—review; V.A.T.: conceptualization, questionnaire design and field sampling work; E.J.N.: questionnaire design and field sampling work, J.M.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation and writing-review; A.S.T and T.F.: supervision, project administration, conceptualization, questionnaire design, methodology, interpretation of results, investigation, writing—review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Map showing the distribution of study sites in the Centre (top) and Littoral (bottom) Regions.

Figure 1.

Map showing the distribution of study sites in the Centre (top) and Littoral (bottom) Regions.

Figure 2.

Sources of seeds (A) and mean production of palm oil per season (B) by smallholders in Cameroon. Bars represent mean frequencies ± 95% confidence level.

Figure 2.

Sources of seeds (A) and mean production of palm oil per season (B) by smallholders in Cameroon. Bars represent mean frequencies ± 95% confidence level.

Figure 3.

Production of palm oil and associated waste generation and disposal in smallholders’ farms in Cameroon.

Figure 3.

Production of palm oil and associated waste generation and disposal in smallholders’ farms in Cameroon.

Figure 4.

Respondents’ perspectives on measures to curb the problems of deforestation (A) and land uses prior to plantation establishment (B) in Cameroon. Bars represent mean frequencies ± 95% confidence level.

Figure 4.

Respondents’ perspectives on measures to curb the problems of deforestation (A) and land uses prior to plantation establishment (B) in Cameroon. Bars represent mean frequencies ± 95% confidence level.

Figure 5.

Factor analysis of respondents’ demographic characteristics with oil palm production characteristics. Blue rings indicate variables that are strongly associated; the lengths of the red lines indicate the strengths of the variables within the association; PA = plantation age, LE = level of experience, OFL = ownership of family land, M_FBB = market for FFBs, A_IF = access to informal finance, LH = labour for harvest, PPS = production per season, LS = labour safety, LED = level of education, M_FF = modes of farm financing, RA = replanting age, RAPP = rates of application, FT = fertilizer type, TL = types of labour, AC = access to credit, SP = source of processing, SA = soil amendment, IL = incentives to labour, SFL = source of farmland, FFB_Y = FFB, DC = duration in community, OL = origin of labour.

Figure 5.

Factor analysis of respondents’ demographic characteristics with oil palm production characteristics. Blue rings indicate variables that are strongly associated; the lengths of the red lines indicate the strengths of the variables within the association; PA = plantation age, LE = level of experience, OFL = ownership of family land, M_FBB = market for FFBs, A_IF = access to informal finance, LH = labour for harvest, PPS = production per season, LS = labour safety, LED = level of education, M_FF = modes of farm financing, RA = replanting age, RAPP = rates of application, FT = fertilizer type, TL = types of labour, AC = access to credit, SP = source of processing, SA = soil amendment, IL = incentives to labour, SFL = source of farmland, FFB_Y = FFB, DC = duration in community, OL = origin of labour.

Figure 6.

Hygienic practices (A) and knowledge on ways to minimise air and water pollution (B) during the milling of palm oil. Bars represent mean frequencies ±95% confidence level.

Figure 6.

Hygienic practices (A) and knowledge on ways to minimise air and water pollution (B) during the milling of palm oil. Bars represent mean frequencies ±95% confidence level.

Figure 7.

Factor analysis of respondents’ demographic characteristics with palm oil storage attributes. The blue ring indicates variables that are strongly associated; the lengths of the red lines indicate the strengths of the variables within the association; LED = level of education, MPS = measures to prevent spoilage, EPOS = experienced spoilage in storage, DC = duration in community, BSC = benefits of using specific containers, PSM = preventive steps against microbial contamination.

Figure 7.

Factor analysis of respondents’ demographic characteristics with palm oil storage attributes. The blue ring indicates variables that are strongly associated; the lengths of the red lines indicate the strengths of the variables within the association; LED = level of education, MPS = measures to prevent spoilage, EPOS = experienced spoilage in storage, DC = duration in community, BSC = benefits of using specific containers, PSM = preventive steps against microbial contamination.

Figure 8.

Factor analysis of associations of respondents’ demographic characteristics with labour, uses, and cultural and legal considerations. The lengths of the red lines indicate the strengths of the variables within the association; LED = level of education, LTOP = land tenure and the oil palm industry, IS = indicators of spoilage, BPQ = brand names and palm oil quality, CMLF = customary and modern legal frameworks, CPW = compensation modes for palm work, CCTW = challenges in collection and transportation of waste, EPO = how to ensure purchase of oil, CH = cost per hectare, TIS = technology, innovation, and safety, DC = duration in community, MSW = management of solid waste, IME = impact of palm mill effluent, RWP = health risks of working in processing, UP = main uses of palm oil, UEF = use of empty fruit bunches, APM = sustainable alternative production methods, SSILP = social sustainability and improved labour practices.

Figure 8.

Factor analysis of associations of respondents’ demographic characteristics with labour, uses, and cultural and legal considerations. The lengths of the red lines indicate the strengths of the variables within the association; LED = level of education, LTOP = land tenure and the oil palm industry, IS = indicators of spoilage, BPQ = brand names and palm oil quality, CMLF = customary and modern legal frameworks, CPW = compensation modes for palm work, CCTW = challenges in collection and transportation of waste, EPO = how to ensure purchase of oil, CH = cost per hectare, TIS = technology, innovation, and safety, DC = duration in community, MSW = management of solid waste, IME = impact of palm mill effluent, RWP = health risks of working in processing, UP = main uses of palm oil, UEF = use of empty fruit bunches, APM = sustainable alternative production methods, SSILP = social sustainability and improved labour practices.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents.

| Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Sex |

|

|

|

Status |

|

|

| Male |

29 |

64.4 |

|

Single |

10 |

22.2 |

| Female |

16 |

35.6 |

|

Married |

21 |

46.7 |

| Total |

45 |

100 |

|

Free Union |

1 |

2.2 |

| Age group |

|

|

|

Widow |

13 |

28.9 |

| 20–30 |

10 |

22.2 |

|

Total |

45 |

100 |

| 31–40 |

15 |

33.3 |

|

Religion |

|

|

| 41–50 |

7 |

15.6 |

|

Catholicism |

9 |

20 |

| 51–60 |

6 |

13.3 |

|

Protestantism |

30 |

66.7 |

| >60 |

7 |

15.6 |

|

Pentecostalism |

1 |

2.2 |

| Total |

45 |

100 |

|

Islam |

5 |

11.1 |

| Education |

|

|

|

Total |

45 |

100 |

| Primary |

23 |

51.1 |

|

Duration in |

Community |

|

| Secondary |

14 |

31.1 |

|

< 5 years |

4 |

8.9 |

| Higher |

5 |

11.1 |

|

5 – 9 years |

10 |

22.2 |

| Vocational |

3 |

6.7 |

|

>10 years |

28 |

62.2 |

| Total |

45 |

100 |

|

Since birth |

3 |

6.7 |

| IGAs |

|

|

|

Total |

45 |

100 |

| Yes |

34 |

75.6 |

|

Occupation |

|

|

| No |

11 |

24.4 |

|

Farming / fishing |

34 |

75.6 |

| Total |

45 |

100 |

|

Trading |

1 |

2.2 |

| |

|

|

|

Employe |

10 |

22.2 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

45 |

100 |

Table 2.

Technical characteristics of oil palm production and harvesting.

Table 2.

Technical characteristics of oil palm production and harvesting.

| Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Level of experience in palm farming |

|

|

| 21-30 years |

22 |

48.9 |

| Suitable planting season |

|

|

| Rainy season |

43 |

95.6 |

| Farm size |

|

|

| 0-5 ha |

28 |

62.2 |

| Variety grown |

|

|

| Both dura and Tenera |

21 |

46.7 |

|

Re ason for choice of variety

|

|

|

| Based on experience |

21 |

46.7 |

| Variety with respect to yield |

|

|

| Tenera provides higher oil yield than Dura |

36 |

80 |

| Knowledge on improved varieties |

|

|

| New breed of Tenera from SOCAPALM |

17 |

37.8 |

| No idea |

28 |

62.2 |

| Prunning frequency |

|

|

| Prune twice a year for old trees, thrice for young |

31 |

68.9 |

| Harvest volumes in relation to months |

|

|

| Low, June to Dec; medium, none; high, Jan to May |

29 |

64.4 |

| Harvesting equipment |

|

|

| Both chisel and Malayan knife |

26 |

57.8 |

| Harvesting methods |

|

|

| Manual |

45 |

100 |

| Harvesting risks |

|

|

| Accidents, health issues, cost |

45 |

100 |

Table 3.

Oil palm production and land tenure characteristics of smallholders’ farms surveyed in Cameroon.

Table 3.

Oil palm production and land tenure characteristics of smallholders’ farms surveyed in Cameroon.

| Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Factors affecting production |

|

|

| No fertilizer application and management |

29 |

64.4 |

| Pest and disease management |

|

|

| None |

43 |

95.6 |

| Use of sustainable practices |

|

|

| No |

23 |

51.1 |

| Total |

45 |

100 |

| Age of farm |

|

|

| 11–20 years |

27 |

60.0 |

| Economic age for replanting |

|

|

| 21–40 years |

35 |

77.8 |

| Trained on sustainable production |

|

|

| No |

42 |

93.3 |

| Source of farmland |

|

|

| Rented land |

14 |

31.1 |

| Bought land |

18 |

40.0 |

| Ownership of household land |

|

|

| Male adult |

28 |

62.2 |

| Relief of farm |

|

|

| Flat |

20 |

44.4 |

| Desire for more land for expansion |

|

|

| Yes |

43 |

95.6 |

Table 4.

Transportation and other postharvest considerations in oil palm production and management.

Table 4.

Transportation and other postharvest considerations in oil palm production and management.

| Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

| State of farm roads |

|

|

| Poor |

6 |

13.3 |

| Bad |

32 |

71.1 |

| Very bad |

7 |

15.6 |

| Total

|

45 |

100 |

| Source of processing of FFBs |

|

|

| Own artisanal mills |

25 |

55.6 |

| Other artisanal mills |

20 |

44.4 |

| Total

|

45 |

100 |

| Market for FFBs |

|

|

| In own mills |

30 |

66.7 |

| Sell to intermediaries |

15 |

33.3 |

| Total

|

45 |

100 |

Table 5.

Technical considerations in palm oil processing among smallholders in Cameroon.

Table 5.

Technical considerations in palm oil processing among smallholders in Cameroon.

| Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Storage method |

|

|

| Bare floor |

45 |

100 |

| Method of separating nuts |

|

|

| Whole bunches, fermentation, and shredding, 2nd-fermentation |

27 |

60.0 |

| Source of mills |

|

|

| Bought |

22 |

48.9 |

| Cost of mills |

|

|

| 3 Million |

19 |

42.2 |

| Duration (years) of use |

|

|

| 5-20 |

27 |

60.0 |

| Type of mill |

|

|

| Others |

36 |

80.8 |

| Capacity |

|

|

| 1 ton FFBs (160-200 L oil) |

21 |

46.7 |

| Efficiency factors |

|

|

| Machine extraction rate |

14 |

31.1 |

| Machine age |

17 |

37.8 |

| Oil characteristics |

|

|

| Dura produces good quality palm oil |

8 |

17.8 |

| Tenera yields more palm oil |

3 |

6.7 |

| All |

29 |

64.4 |

| Stages and inputs |

|

|

| Fermentation, boiling, digestion, pressing, clarification, boiling |

28 |

62.2 |

| Measurement of inputs |

|

|

| tonnage of FFBs (32 sacks=1 ton), unquantified water, no chemicals |

21 |

46.7 |

| tonnage of FFBs (200 L=1 ton), unquantified water, no chemicals |

15 |

33.3 |

| Challenges and risks |

|

|

| FFB weight is based on estimation, and fruit and oil burn when water is insufficient |

38 |

84.4 |

| Equipment maintenance |

|

|

| Use hot water for cleaning without detergent |

45 |

100 |

| Challenges in adopting modern methods |

|

|

| Lack of finances and maintenance |

23 |

51.1 |

Table 6.

Health hazards and related attributes in smallholders’ oil palm plantations.

Table 6.

Health hazards and related attributes in smallholders’ oil palm plantations.

| Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Prevention of health risks |

|

| Drink extracts from bitter leaf and pawpaw leaves with milk |

14 |

31.1 |

| History of health problems |

|

|

| Yes |

34 |

75.6 |

| Regulations and guidelines |

|

|

| None |

43 |

95.6 |

| Support in promoting hygiene |

|

|

| Souza council checks on sanitary conditions of workers |

27 |

60.0 |

| Protection from heat and smoke exposures |

|

|

| Protective clothes and face masks |

20 |

44.4 |

| Payment of workers bills |

|

|

| Workers pay themselves |

29 |

64.4 |

Table 7.

Spearman rank correlation analysis results showing relationships between health-related variables.

Table 7.

Spearman rank correlation analysis results showing relationships between health-related variables.

| |

Health risks |

Prevention of health risks |

History of health problems |

Support in promoting hygiene |

| Prevention of health risks |

-0.009 |

|

|

|

| |

0.952 |

|

|

|

| History of health problems |

0.201 |

-0.196 |

|

|

| |

0.186 |

0.198 |

|

|

| Support in promoting hygiene |

-0.432** |

0.486** |

-0.464** |

|

| |

0.003 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

|

| Protection from exposure |

0.262 |

-0.114 |

0.223 |

-0.190 |

| |

0.082 |

0.457 |

0.140 |

0.210 |

Table 8.

Technical considerations during storage of palm oil across the study sites.

Table 8.

Technical considerations during storage of palm oil across the study sites.

| Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Measures to prevent spoilage |

|

|

| Prevent impurity contamination of the oil |

20 |

44.4 |

| Corrosion of storage containers |

|

|

| None |

41 |

91.1 |

| Monitor quality during storage |

|

|

| Yes |

23 |

51.1 |

| Quality attributes considered in monitoring |

|

|

| Sensory qualities |

31 |

68.9 |

| Preventive steps against microbial contamination during storage |

|

|

| None |

20 |

44.4 |

Table 9.

Characteristics of production and yield losses in smallholders’ plantations.

Table 9.

Characteristics of production and yield losses in smallholders’ plantations.

| Parameter |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Most common production losses |

|

|

| Quality and quantity losses |

34 |

75.6 |

| Percentage loss due to poor harvest |

|

|

| 10-18% |

20 |

44.4 |

| Implication of yield losses |

|

|

| Low income |

16 |

35.6 |

| Support to improve yield |

|

|

| None |

45 |

100 |

| Balance yield and sustainability |

|

|

| Minimal sustainable practices (tree planting) |

28 |

62.2 |

| Weather patterns and yield |

|

|

| High rainfall reduces quality and causes erosion |

14 |

31.1 |

| Factors for sustainable production and yield |

|

|

| Access to finances, good quality nuts, and processing facilities |

10 |

22.2 |

Table 10.

Spearman rank correlation results showing relationships between yield and oil losses-related variables.

Table 10.

Spearman rank correlation results showing relationships between yield and oil losses-related variables.

| |

Factors affecting oil yield |

Method to manage processing |

Innovations to increase yield |

| Method to manage processing |

0.479** |

|

|

| |

0.001 |

|

|

| Innovations to increase yield |

-0.471** |

-0.410** |

|

| |

0.001 |

0.005 |

|

| Most common production losses |

-0.034 |

-0.515** |

0.264 |

| |

0.825 |

0.000 |

0.079 |

Table 11.

Oil palm waste and its management.

Table 11.

Oil palm waste and its management.

| Parameters |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Management of empty fruit bunches |

|

|

| Burning |

27 |

60 |

| Destination of liquid mill waste |

|

|

| Directed into a pit |

17 |

37.8 |

| Management of solid waste |

|

|

| Burning |

26 |

57.8 |

| Challenges in collection and transport of waste |

|

|

| Bad roads |

16 |

35.6 |

| Palm oil effluent |

|

|

| Liquid waste from FFBs |

24 |

53.3 |

| Variation in impacts of palm oil effluent |

|

|

| More FFBs processed, more POME |

24 |

53.3 |

| Impact of palm mill effluent |

|

|

| Nuisance and mosquito breeding grounds |

23 |

51.1 |

| Steps to mitigate environmental impacts of effluent |

|

|